Abstract

Background

The rpoB-psbZ (BZ) region of some fern plastid genomes (plastomes) has been noted to go through considerable genomic changes. Unraveling its evolutionary dynamics across all fern lineages will lead to clarify the fundamental process shaping fern plastome structure and organization.

Results

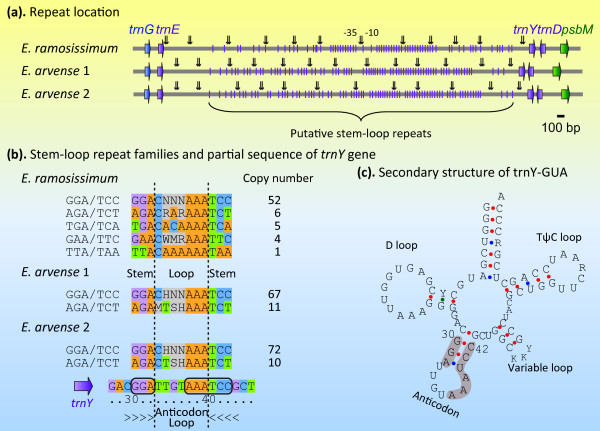

A total of 24 fern BZ sequences were investigated with taxon sampling covering all the extant fern orders. We found that: (i) a tree fern Plagiogyria japonica contained a novel gene order that can be generated from either the ancestral Angiopteris type or the derived Adiantum type via a single inversion; (ii) the trnY-trnE intergenic spacer (IGS) of the filmy fern Vandenboschia radicans was expanded 3-fold due to the tandem 27-bp repeats which showed strong sequence similarity with the anticodon domain of trnY; (iii) the trnY-trnE IGSs of two horsetail ferns Equisetum ramosissimum and E. arvense underwent an unprecedented 5-kb long expansion, more than a quarter of which was consisted of a single type of direct repeats also relevant to the trnY anticodon domain; and (iv) ycf66 has independently lost at least four times in ferns.

Conclusions

Our results provided fresh insights into the evolutionary process of fern BZ regions. The intermediate BZ gene order was not detected, supporting that the Adiantum type was generated by two inversions occurring in pairs. The occurrence of Vandenboschia 27-bp repeats represents the first evidence of partial tRNA gene duplication in fern plastomes. Repeats potentially forming a stem-loop structure play major roles in the expansion of the trnY-trnE IGS.

Background

In contrast to nuclear and mitochondrial genomes, plant plastid (chloroplast) genomes (plastomes) are generally conserved in genome size, gene content and gene order [1-3]. This high conservation makes the plastid genes and genomes quite amenable for sequencing and be widely used in evolutionary and phylogenetic studies. Nevertheless, comparative genomics studies demonstrate that the plastomes of several vascular plant lineages such as lycophytes (Selaginellaceae) [4,5], gymnosperms (e.g. Pinaceae [6-8], Cupressaceae [9], Welwitschiaceae [7,10], Gnetaceae and Ephedraceae [7]) and various eudicot angiosperm lineages (e.g. Geraniaceae [2,11], Campanulaceae [12,13] and Fabaceae [14,15]), have experienced remarkable genomic changes including significant size variations, complex rearrangements as well as substantial gene losses. Many reports have shown that highly rearranged plastomes usually contain a large number of repetitive elements [2,11,12,16]. Furthermore, the distribution of the repeats also exhibits a tendency to flank the rearrangement endpoints, implying an association between the repeat and the rearrangement [2,9,11,12,16-18]. Recently, Maréchal and Brisson [19] specified that the suppression of recombination between repeats is of importance in the maintenance of plastome stability. Nevertheless, besides rearrangement endpoints, abundant repeats are also found in other regions of plastomes. For instance, extensive dispersed repeats have been found throughout the algae plastome of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii [20], and many direct repeats derived from partial duplication of their nearby trnY-GUA gene have been observed in Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) [21]. These findings highlight the structural and functional significances of chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) repeats. In Chlamydomonas plastomes, it has been shown that small dispersed repeats can influence both transcript stability and translation efficiency [22] or even function in DNA repair [23]. Previous studies, particularly those on the complete plastome sequences, have well documented the characteristics and distribution of cpDNA repeats [2,9,11,12,16,20,24,25]. However, very few investigations deal with the implications of the secondary structure of cpDNA repetitive elements on their origin, proliferation and potential function [26]. Delineating the secondary structural features should greatly facilitate our understanding of plastome evolution.

A number of comparative chloroplast genomic studies have uncovered structural mutations in fern (monilophyte) cpDNAs, including as many as 6 inversions and a few gene losses [24,27-32]. Specifically, one ~3.3 kb inversion (involving trnG-GCC to trnT-GGU) [27] and an inverted trnD-GUC gene (D inversion) [24] have been detected across ferns relative to other land plants. According to gene orders, the fern plastomes can be classified into two main types. One comprises the plastomes of taxa diversifying before the separation of the Schizaeales, which share the ancestral gene order and has been assumed to undergo no major rearrangements [33]. By contrast, the other composes the plastomes of core leptosporangiates possessing the derived gene order [33]. This derived gene order is characteristic of highly rearranged inverted repeats (IRs) with the rRNA genes arranged in reverse order in comparison to all other plants [34]. The rearranged IRs and their adjacent section of large single copy (LSC) region are thought to be generated by two partially overlapping inversions spanning LSC and IR regions [35]. Wolf et al. [33] recently illustrated that the two putative inversions occurred in pairs on the branch leading to the common ancestor of schizaeoid and core leptosporangiate ferns.

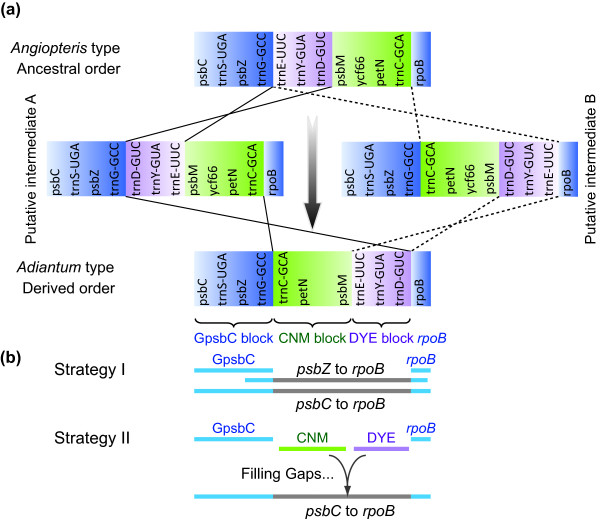

The next striking difference between the ancestral and derived gene order is occurred between the rpoB and psbZ (BZ) in LSC region (Figure 1a). BZ region is characterized with a high degree of variability. Each of the three key inversions shaping the ancestral gene order of ferns, i.e. the 30-kb inversion [36], the 3.3-kb inversion [27] and the D inversion [24] , have at least one of their endpoints located within BZ region. Notably, up to five tRNA genes are concentrated in this small region after the three inversions (Figure 1a). This uncommonly high frequency of tRNA genes may be relative with the instability of BZ region. Roper et al. [28] suggested that the gene order changes within BZ region (hereafter the BZ rearrangement) of ferns can also be derived from two partially overlapping inversions by either of the two potential pathways (Figure 1a). Nonetheless, since all the investigated core leptosporangiates possess the derived BZ order (the same as Adiantum type gene order) (Figure 1a) and no intermediate has been identified in any ferns, it has been argued that the two hypothetical inversions should take place in pairs in the common ancestor of core leptosporangiates [33]. Unfortunately, the previous studies have only examined four complete (3 polypods and 1 tree fern) [24,27,30,32] and six partial plastome sequences from the leptosporangiates [33]. If more samples are examined, the putative intermediates may be uncovered.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of the fern plastid gene orders from psbC to rpoB (a) and sequencing strategies (b). Each colored gene segment shows the same gene order region among the published fern plastomes. The gene orders of "Putative intermediate A" and "Putative intermediate B" are according to Roper et al. [28].

In this study, we mainly investigated the evolutionary process of BZ region and its sequence components in ferns. Twenty-four fern BZ sequences were studied guided by the recently published phylogenetic framework [37], with a focus on leptosporangiates. Firstly, a novel gene order was detected in the tree fern Plagiogyria japonica, which may represent the intermediate of BZ rearrangement or the reverse mutant of the Adiantum type. Secondly, a unique 459-bp region, consisting of 17 tandem 27-bp repeats derived from the partial duplication of the adjacent trnY gene, was found to cause the trnE-trnY intergenic spacer (IGS) of the filmy fern Vandenboschia radicans to expand approximately 3-fold in length. To our knowledge this is the first report of partially duplicated tRNA gene in fern plastomes. Thirdly, unexpected 5-kb long trnE-trnY IGSs were observed in two horsetail ferns Equisetum ramosissimum and E. arvense. More than a quarter of the IGSs was comprised of a single type of direct repeats possessing the potential to form a highly conserved stem-loop structure. The direct repeats may have a recent evolutionary origin, frequently conduct copy corrections, and are of significant functional relevance. And fourthly, the occurrence of ycf66 was confirmed highly unstable in ferns with at least 4 times of independent losses.

Methods

DNA amplification and sequencing

Up to date, seven complete plastome sequences of ferns have been deposited in GenBank, whose data can be directly extracted. Besides these, additional 17 sampling taxa were chosen based on the previously published phylogenetic framework of extant ferns [37] to represent all major lineages at the order level (Table 1). Young leaves of the 17 fern species were collected from Wuhan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), South China Botanical Garden, CAS, and Shenzhen Fairy Lake Botanical Garden. Voucher specimens were deposited at the herbarium of Wuhan Botanical Garden, CAS. Total DNA isolation, primer design, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing were as previously described [24].

Table 1.

List of taxa and sequences analyzed in this study

| Taxon | Familya | Ordera | Collection informationb | GenBank | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adiantum capillus-veneris | Pteridaceae | Polypodiales | - | NC_004766 | Wolf et al. 2003 [27] |

| Asplenium australasicum | Aspleniaceae | Polypodiales | WBG | HQ658095 | This study |

| Cheilanthes lindheimeri | Pteridaceae | Polypodiales | - | NC_014592 | Wolf et al. 2010 [30] |

| Platycerium bifurcatum | Polypodiaceae | Polypodiales | WBG | HQ658094 | This study |

| Pteridium aquilinum | Dennstaedtiaceae | Polypodiales | - | NC_014348 | Der 2010 [32] |

| Alsophila spinulosa | Cyatheaceae | Cyatheales | - | NC_012818 | Gao et al. 2009 [24] |

| Plagiogyria japonica | Plagiogyriaceae | Cyatheales | SZBG | HQ658099 | This study |

| Azolla caroliniana | Salviniaceae | Salviniales | WBG | HQ658096 | This study |

| Marsilea quadrifolia | Marsileaceae | Salviniales | WBG | HQ658098 | This study |

| Salvinia molesta | Salviniaceae | Salviniales | SCBG | HQ658097 | This study |

| Lygodium microphyllum | Lygodiaceae | Schizaeales | SZBG | HQ658100 | This study |

| Dicranopteris linearis | Gleicheniaceae | Gleicheniales | SZBG | HQ658102 | This study |

| Diplopterygium chinensis | Gleicheniaceae | Gleicheniales | SZBG | HQ658103 | This study |

| Dipteris chinensis | Dipteridaceae | Gleicheniales | WBG | HQ658101 | This study |

| Vandenboschia radicans | Hymenophyllaceae | Hymenophyllales | WBG | HQ658104 | This study |

| Osmunda vachellii | Osmundaceae | Osmundales | WBG | HQ658105 | This study |

| Angiopteris evecta | Marattiaceae | Marattiales | - | NC_008829 | Roper et al. 2007 [28] |

| Botrychium strictum | Ophioglossaceae | Ophioglossales | WBG | HQ658108 | This study |

| Helminthostachys zeylanica | Ophioglossaceae | Ophioglossales | SCBG | HQ658107 | This study |

| Ophioglossum vulgatum | Ophioglossaceae | Ophioglossales | SZBG | HQ658106 | This study |

| Psilotum nudum | Psilotaceae | Psilotales | - | NC_003386 | Wakasugi et al. 1998 [29] |

| Equisetum arvense 1 | Equisetaceae | Equisetales | SCBG | HQ658110 | This study |

| Equisetum arvense 2 | Equisetaceae | Equisetales | - | GU191334 | Karol et al. 2010 [31] |

| Equisetum ramosissimum | Equisetaceae | Equisetales | SCBG | HQ658109 | This study |

a - the nomenclature follow Smith et al. [37].

b -WBG, Wuhan Botanical Garden, CAS; SCBG, South China Botanical Garden, CAS; SZBG, Shenzhen Fairy Lake Botanical Garden. All voucher specimens were deposited at the herbarium of Wuhan Botanical Garden, CAS.

To obtain the sequences from rpoB to psbZ, the conserved flanking regions, partial sequence of rpoB gene and GpsbC (psbC to trnG) block (Figure 1a) were amplified, cloned into plasmid vectors (pCR2.1, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transformed into E. coli DH5α. At least three clones for each PCR product were randomly selected and commercially sequenced from both ends using ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Species-specific primers were then designed based on the flanking sequences and long-range PCR was performed to amplify rpoB-psbZ region (Figure 1b, Strategy I). The desired band was gel-purified, sequenced from both ends, and then determined the remains by primer walking. To avoid the potential error from PCR and sequencing, each PCR fragment was independently sequenced twice. If they had differences, additional sequencings were performed.

For some samples, whose BZ sequences were unable to be completely acquired by primer walking sequencing of PCR products because of repeats and/or complex secondary structures, a two-step approach was applied (Figure 1b, Strategy II): first, the regions of CNM (trnC-petN-psbM) and DYE (trnD-trnY-trnE) gene blocks were amplified, cloned and sequenced; second, species-specific primers were designed based on the CNM and DYE sequences coupled with the primers from the rpoB gene and GpsbC region to amplify the remained sections. At least three clones for each PCR product were sequenced. The overlapping regions of each pair of adjacent PCR fragments exceeded 150 bp.

The sequences generated in this paper have been deposited in GenBank (accession numbers: HQ658094-HQ658110) (Table 1).

Sequence assembly and annotation

The individual reads were cleaned by removing vector, primer and low-quality sequences, then assembled using CAP [38] through BioEdit [39]. The assembled sequences were annotated by DOGMA (Dual Organellar GenoMe Annotator) [40]. Start and stop codons were defined through comparison to published complete plastome sequences available in GenBank. To detect tRNA genes, two online programs were employed, ARAGORN v1.2 [41] and tRNAscan-SE v.1.21 [42]. The putative promoters were identified by running BPROM [43].

Repeat sequence analyses

The sequences were initially scanned with REPuter [44] at a repeat length ≥ 20 bp with a Hamming distance of 3. Forward (direct), reverse, complement and reverse complement repeats were all recognized under REPuter. Repeated sequences were unusually abundant in E. ramosissimum and E. arvense. For them, repeats were further identified and classified by the VMATCH software package [45]. For each sequence, an index was constructed using MKVTREE program with the -dna -pl -allout and -v options. Direct repeats ≥ 20 bp were identified using VMATCH and then divided into distinct families with MATCHCLUSTER by allowing 15% sequence dissimilarity (-erate option set to 15). The sequences of each family were extracted with VMATCHSELECT. Like REPuter, the VMATCH identifies all overlapping repeats and thus overestimates the number of repetitive elements in a given sequence. To avoid this issue, the redundant overlapping repeats were masked. The consensus for each family was then generated from a CLUSTAL X [46] alignment.

The secondary structures of repeated sequences were predicted by Mfold web server [47] with default parameters. Most of the repeats found in horsetails have a stem-loop structure with a 7-nt loop. Then, we designed a Perl script (available on request) to detect the sequence fragments which have the following stem-loop structure characteristics: loop length = 7 and stem length ≥3. The identified stem-loop sequences were assigned to distinct families according to their stem sequences afterwards.

Phylogenetic analyses

A total of 5 protein-coding (petN, psbC, psbM, psbZ, rpoB) and 6 tRNA gene (trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnG-GCC, trnS-UGA, trnY-GUA) sequences were extracted from 17 new generated fern plastid sequences from psbC to rpoB in this study (Figure 1). The coding sequences of these 11 genes were also acquired from the completed plastomes of 6 ferns, i.e. Adiantum capillus-veneris, Alsophila spinulosa, Angiopteris evecta, Cheilanthes lindheimeri, Psilotum nudum and Pteridium aquilinum, as well as 2 seed plant outgroups, i.e. Amborella trichopoda (NC_005086) and Cycas taitungensis (NC_009618), according to their annotations in GenBank. The nucleotide sequences of each tRNA gene were aligned in MUSCLE [48] with manual inspection. For protein-coding genes, nucleotide sequences for each gene were translated into amino acids, aligned in MUSCLE [48]. Nucleotide sequences were aligned by constraining them to the amino acid sequence alignment followed by manual adjustments. A Nexus file comprising 5,525 characters was generated after alignment was completed.

Phylogenetic analyses were performed using maximum likelihood (ML) (GARLI v1.0.699) [49] and Bayesian inference (BI) (MrBayes v3.1.2) [50]. The most appropriate model (GTR+I+G) of nucleotide evolution was determined by using the Akaike Information Criterion via Modeltest 3.7 [51]. For ML, three independent runs were conducted in GARLI, using default parameters except that automated stopping criterion set at 20,000 generations (genthreshfortopoterm = 20000). A total of 1,000 ML Bootstrap (BS) replicates was also performed using GARLI. Likelihood scores were calculated by using PAUP v4.10 [52]. For BI, each run started with a random tree, default priors and four Markov chains, and were sampled every 100 generations. Three independent analyses were run for 1 × 107, 1.5 × 107 and 2 × 107 generations. Convergence was confirmed by Tracer 1.5 [53]. Twenty-five percent of burn-in trees were discarded.

Results and Discussion

The process of rpoB-psbZ rearrangement

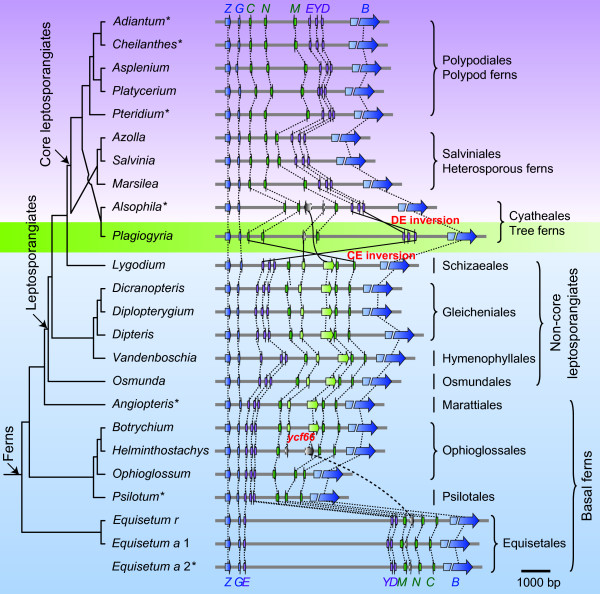

Two putative pathways have been proposed for describing the evolutionary process of the complex gene order change between rpoB and psbZ through fern evolution (Figure 1a) [28]. However, no direct evidence is provided for either of them. Figure 2 shows the BZ gene order in 24 samples representing all the 11 extant fern orders (Table 1) [following reference 37]. Two blocks of genes, CNM (trnC-petN-psbM) and DYE (trnD-trnY-trnE), are found to be conserved across ferns. Nearly all core leptosporangiates excluding Plagiogyria japonica have the same gene arrangement pattern as that observed in Adiantum capillus-veneris [27] (hereafter the Adiantum type). By contrast, all basal ferns and early branches of leptosporangiates share the gene order previously found in Angiopteris evecta [28] (hereafter the Angiopteris type). Unlike other core leptosporangiates, the tree fern P. japonica (Plagiogyriaceae) does not present the Adiantum type order. Instead its gene order (hereafter the Plagiogyria type) seems to derive from the Angiopteris type via a large inversion spanning from trnC-GCA to trnE-UUC ("CE inversion" in Figure 2) or from the Adiantum type through a small inversion only involving the DYE block ("DE inversion" in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The gene organization from rpoB to psbZ in analyzed ferns. The arrows correlate with the location, size and transcription direction of the corresponding genes. Dashed lines indicate direction of transcription does not change; solid lines mark putative local inversions. The complete version of the tree including statistical supports and branch lengths is shown in Additional file 1. *, the plastomes have been sequenced. The symbols of ycf66: green, complete gene; grey, pseudogene. Abbreviations: Z, psbZ; G: trnG-GCC; E: trnE-UUC; Y: trnY-GUA; D, trnD-GUC; M, psbM; N, petN; C, trnC-GCA; B: rpoB; Equisetum a, Equisetum arvense; Equisetum r, Equisetum ramosissimum.

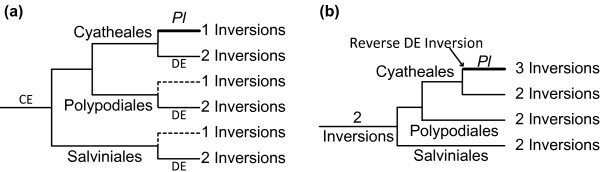

The Plagiogyria type order seemingly represents the intermediate of BZ rearrangement. If this hypothesis is true, we might speculate that the Adiantum type is formed through two serial inversions, first the large CE inversion and then the small DE inversion (as shown in Figure 2). For the CE inversion, the most parsimonious explanation is that it occurred only once and on the common ancestor of core leptosporangiates (Figure 3a), because the Adiantum type has been observed in all the three core leptosporangiate lineages. The next question is at which evolutionary stage the DE inversion event occurred? Recent studies have identified Plagiogyriaceae as a lineage of tree ferns [54-61]. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that the Adiantum type found in tree ferns directly arose from the Plagiogyria type. As for the Adiantum type in other core leptosporangiate ferns, intuitively it is also intended to infer that this order was derived from the Plagiogyria type. However, current knowledge of the phylogenetic positions of both Plagiogyriaceae and tree ferns make the speculation implausible. Molecular phylogenetic analyses have shown that tree ferns are the sister group of polypods, and then the two groups jointly compose the sister group to heterosporous ferns (Figure 2, Additional file 1) [56,58,59,61-65]. If it is presumed that the Adiantum type observed in heterosporous and polypod ferns originated directly from the Plagiogyria type, there should exist unknown polypod and heterosporous fern species that possess the same intermediate gene order as that of Plagiogyria. In other words, once the Plagiogyria type is hypothesized to be the intermediate form of the BZ rearrangement, the putative DE inversion would have had to independently occur at least three times (each in the three core leptosporangiate lineages, respectively) to transit the Plagiogyria type into the Adiantum type (Figure 3a). Therefore, taking the Plagiogyria type as the intermediate form actually becomes a very unlikely pathway for establishing the derived BZ gene type.

Figure 3.

Two potential explanations for the origin of the Plagiogyria gene order. Pl, Plagiogyria. The minimal numbers of inversion events compared to the Angiopteris type are provided for each branch. (a), "CE" and "DE" indicate the putative CE and DE inversions as figure 2, respectively. The dashed lines show the hypothetical branches with no experimental evidence. (b), "2 inversions" denotes the two hypothetical inversions that converted the Angiopteris type to the Adiantum type [28].

An alternative interpretation is that the Plagiogyria type merely represents a derivative of the Adiantum type via a reverse DE inversion (Figure 3b). As shown in figure 2, the DYE block is quite short, merely ~300-500 bp in most leptosporangiates. Since it is well recognized that the small-scale inversion is highly prone to reversal and parallelism [66], and the high degree of rearrangements is often associated with tRNA genes [12], here we would propose that the occurrence of the reverse DE inversion should be of great possibility. If this is indeed the case, then the exact process of the alteration of Angiopteris type to Adiantum type remains an open question.

trnD-GUC inversion

Three consecutive tRNA genes, trnD-GUC, trnY-GUA and trnE-UUC, are embedded in the BZ region. In seed plants, they have been shown to constitute an operon (trnE operon) whose transcript is processed to produce individual tRNA molecules [67]. Nevertheless, in our previous report, the trnD gene was found to have an opposite transcriptional direction relative to trnY and trnE in ferns based on the four completely sequenced fern plastome data available at that time [24]. With the newly determined sequences here, our previous speculation that the minor D inversion is shared by all fern lineages was further corroborated. Since the trnD is inverted, it is reasonable to assume that this gene is unable to be co-transcripted with trnY and trnE. In addition, the conserved "-35 box" and "-10 box" promoter sequences were also found upstream of the trnD gene in all the studied ferns (Additional file 2), further supporting that the transcription of the inverted trnD gene is independent of the trnE operon.

Intergenic spacers

Sizes of the sequences between rpoB and psbZ are highly variable in ferns, ranging from 2,744 bp in Psilotum nudum to 7,546 bp in E. ramosissimum. The size variability is directly linked to the size of IGS, since both gene content and length are highly conserved in the BZ region (Figure 2).

The IGS of trnY-trnE

The sizes of trnY-trnE IGS (YE-IGS) are largely conservative in ferns, most of them ranging from 95 to 179 bp (Figure 2). The smallest YE-IGS, merely 16 bp, is detected in Platycerium wallichii (a polypod fern). In stark contrast, one filmy fern and two horsetails have experienced dramatic expansion of this region, reaching as long as 619 bp, 4,872 bp and 5,000 bp in Vandenboschia radicans, E. arvense (our sequence, hereafter E. arvense 1) and E. ramosissimum, respectively. The unusual 5-kb long YE-IGS of E. arvense was also noted in the recently published report documenting its complete plastome sequence [[31], hereafter E. arvense 2]. The unexpected large IGS leads us directly to the question of how the region is organized and where its component module originates from.

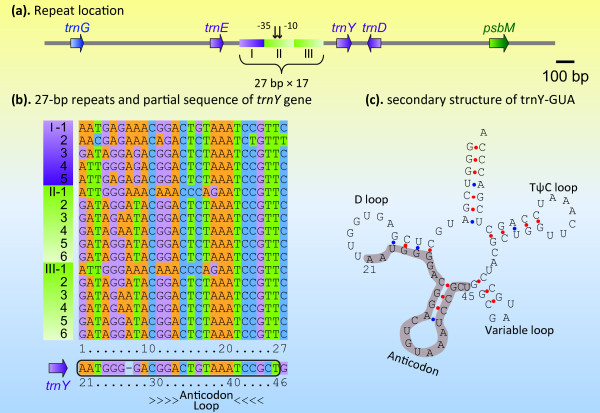

As for V. radicans YE-IGS, a total of 17 tandem 27-bp quasi-identical repeats were found, falling into three modules (Figure 4a). The first contains five 27-bp repeats, while the other two each include six 27-bp repeats (Figure 4b). Interestingly, the two 6 × 27 modules are identical: both are composed of one distantly homologous 27-bp head upstream of five nearly identical 27-bp segments (there is only a single base pair difference among the five repeats) (Figure 4b). We noticed that the sequences of the 27-bp repeats resemble a 25-bp section of the trnY gene (Figure 4b,c), corresponding to the entire anticodon arm and the stem of the D arm. Similarly, the duplications of this trnY region were also characterized in Douglas-fir [21]. To our knowledge, this partial tRNA gene duplication has not been reported in ferns before. Like the trnY anticodon arm, the 27-bp repetitive elements also possess the potential to fold a similar stem-loop structure. The independent occurrences of the partial trnY duplications in filmy fern as well as Douglas-fir imply that the anticodon domain sequence of trnY has a tendency to duplicate and proliferate, possibly relative to its stem-loop secondary structure.

Figure 4.

The 27-bp quasi-identical repeats found in Vandenboschia radicans. "-35" and "-10" denote conserved "-35 box" and "-10 box" promoter sequences predicted by BPROM [43].

The VMATCH software package was used to identify and classify the dispersed repeats in Equisetum. A total of 85 (82 direct and 3 palindromic) and 441 (440 direct and 1 palindromic) matches ≥ 20 bp were detected in the BZ sequences of E. ramosissimum and E. arvense 1, respectively. All the direct matches but one from E. ramosissimum resides in the YE-IGS. To affirm the existence of this large number of repeats in E. arvense, the E. arvense 2 plastome sequence was also analyzed by using VMATCH. 560 direct and 20 palindromic matches were recognized, of which 548 direct matches located in the YE-IGS. The YE-IGS thus far becomes the most repeat-rich region found in the E. arvense plastome.

After filtering the overlapping repeats, 54 and 84 non-redundant direct repeats were identified in the YE-IGS of E. ramosissimum and E. arvense 1, respectively. Based on sequence similarity, the repeats fell into 16-18 families (Table 2). Their secondary structures were then predicted by using Mfold web server [47] (Additional file 3-4). Remarkably, most of the repeats, 45 out of 54 in E. ramosissimum and 76 of 84 in E. arvense 1, were shown to have the potential to fold into similar stem-loop structures with a 7-nt A-rich loop and various length stem. These stem-loop repeats produce a consensus mark of three successive adenine nucleotides ("AAA") proximate to the stem (Additional file 3-4). Their total sizes are 1,154 and 2,014 bp in E. ramosissimum and E. arvense 1 sequence, respectively. The uncommon abundance of the repeats implies that they may correlate to the unexpected expansion of the huge YE-IGS in Equisetum.

Table 2.

Repeat families in the YE-IGS of Equisetum ramosissimum and E. arvense 1 sequence identified by VMATCH

| Repeat familya | Consensusb | Size | Copy Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equisetum ramosissimum | 54 | ||

| A | YTATGGACWWDAAATCCATAR | 21 | 13 |

| B | WCTGRACTCAAAATTCAGAATW | 22 | 4 |

| C | AAGACCTATGGACATGAAATCCATAGGTTGA | 31 | 4 |

| D | TAGCTRTGGACATAAAATCCATAGCT | 26 | 4 |

| E | TTAATTAGTTCTTGACACAAAATCAAGAACT | 31 | 3 |

| F | CTATGAACGTTGATAAGAACAC | 22 | 3 |

| G | ATTAGYTCTTGACACAAAATCRAGAA | 26 | 3 |

| H | ASCTMTGGACAATAAATCCATAGSTTG | 27 | 3 |

| I | GAATTATGGACAAGAAATCYATA | 23 | 3 |

| J | AGCTCTGGACATAAAATCCAGAGCTTTACGGTAG | 34 | 2 |

| K | ACGATCTCTGGACAAAAAATCCATAGAT | 28 | 2 |

| L | TTGGTGGTAAAAGCTATAGACAAGAAATCTATAGCTTG | 38 | 2 |

| M | TGGACTCAAAATCCATAGGTTG | 22 | 2 |

| N | TTTAGGTTCTTTACTTGCACTCTATA | 26 | 2 |

| O | TAATTAGTTCTGGACTTAAAAT | 22 | 2 |

| P | ATTGATTACTATATAATAAAT | 21 | 2 |

| E. arvense 1 | 84 | ||

| A | YTATGGACAAGAAATCCATARVT | 23 | 19 |

| B | YTMTGGACTTAAAATCCATAGDTTK | 25 | 17 |

| C | TAKAWCTCTGGACTTAAAATCCATAGDTT | 29 | 7 |

| D | GTTTTATTTATGGACAAGAAATCCATAA | 28 | 4 |

| E | TTATGGACTGTAAATCCATAR | 21 | 3 |

| F | TTATGGACAAGAAATCCGTAACTATAGAACTAT | 33 | 3 |

| G | GGGTTTTATTTATGGACAAGAAATCCATAGATTG | 34 | 3 |

| H | TATAGTTATAGGTCTGGTGGTARA | 24 | 3 |

| I | TTMTGGACAASAAATCYATAAGT | 23 | 3 |

| J | TTGACAACAAATCCAKAATATCT | 23 | 3 |

| K | TAAYTTCTAGACTCAAAATCTA | 22 | 3 |

| L | TTTCTGGACAAGAAATCCRGAA | 22 | 3 |

| M | GGTACGAYTTCTGGACAATAAATCCAGAATATATGT | 36 | 3 |

| N | AATATCTATAGACTCCAAATCTATAGATATAGTTATAGGTTAGGT | 45 | 2 |

| O | TTATGGACAAGAAATCCATAAATATAGGCT | 30 | 2 |

| P | TTGGTGATATAACTCTGGACTTAAAATCCATAG | 33 | 2 |

| Q | ATATCTATAGACTCCAAATCTATA | 24 | 2 |

| R | ATATATGTATGGACCTGTTGACAACAAATCCATA | 34 | 2 |

In order to test the correlation between the proliferation of the stem-loop sequences and the expansion of YE-IGS, we composed a Perl script to ascertain the exact amount and the distribution of the stem-loop repeats (parameters: loop size = 7, stem length ≥ 3). 90, 96 and 102 hits representing the putative stem-loop structure were identified in the YE-IGS of E. ramosissimum, E. arvense 1 and 2 sequences, respectively. The majority of them, namely 68 in E. ramosissimum, 78 in E. arvense 1 and 82 in E. arvense 2 sequence (Table 3), possess the sequential "AAA" immediate to the stem (Figure 5b). The stem lengths of these A-rich stem-loop elements range from 3 to 13 bp (Table 3). It is worthy to note that the total lengths of the repeats appropriate more than one quarter of the Equisetum YE-IGS, i.e. 25.72%, 28.57% and 28.65% in E. ramosissimum, E. arvense 1 and 2, respectively. In addition, the distribution of the stem-loop repeats is not restricted in a given small region but throughout the entire YE-IGS (Figure 5a). Our results suggest that the proliferation of the stem-loop repeats is directly correlated to the expansion of the YE-IGS in Equisetum.

Table 3.

The occurrence of putative stem-loop sequences with 7-nt loop and "AAA" signature in the YE-IGS of Equisetum ramosissimum and E. arvens e

| Stem length (base pair) | Equisetum ramosissimum | E. arvense 1 | E. arvense 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 21 | 24 | 28 |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | 8 | 12 | 12 |

| 6 | 8 | 22 | 24 |

| 7 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 8 | 16 | 6 | 6 |

| 9 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| 10 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 68 | 78 | 82 |

Figure 5.

The putative A-rich stem-loop repeats in the YE-IGS of Equisetum. The small black arrow pairs indicate the conserved pairs of "-35 box" (left) and "-10 box" (right) promoter sequences predicted by BPROM [43].

The stem-loop sequences fell into 2-4 families according to the first three stem base pairs proximate to the loop (Figure 5b). The most abundant is the GGA/TCC family, which may represent the prototype of the other families. The conserved GGA/TCC stem, 7-nt loop and "AAA" signature push us to postulate that the stem-loop elements may derive from tRNA anticodon arm, because the latter often possess the same stem-loop characteristics. The complete E. arvense plastome sequence data shows that at least 4 tRNAs, i.e. trnC-GCA, trnF-GAA, trnL-UAA and trnY-GUA (Figure 5c), exhibit the GGA/UCC stem core, the 7-nt loop and the "AAA" signature on their anticodon regions. Of them, the trnY locus is exactly neighbor to the repeat region (Figure 5a). Occurrences of trnY-anticodon-arm-related repeats that are close to trnY gene have also been documented in Douglas-fir [21] as well as the aforementioned Vandenboschia (Figure 4). Taken the information together, we suggest that the trnY-GUA gene is possibly the origin of the stem-loop repeats, although other alternatives cannot be definitively ruled out. In contrast to the sizes and the primary sequences, the stem-loop structures of the repeats appear to be highly conservative.

The "-35 box" and "-10 box" promoter sequences were predicted upstream of trnY in Vandenboschia and Equisetum (Figure 4a, 5a), implying that the long YE-IGS may function in regulating the trnY transcription. The highly conserved stem-loop structure detected among the Vandenboschia and Equisetum repeats suggests that the repeats should potentially have a recent evolutionary origin, frequent copy corrections, and certain functional roles. Stem-loop structures have commonly been observed in the plastome IGS regions [66,68-70]. Their loop regions are often associated with hot spots for mutations, while the stem-forming sequences frequently being conserved [66]. Most plastid transcripts potentially form stem-loops in their 5' untranslated regions (5'-UTRs) and 3'-UTRs [71-73], which are thought to function in mRNA maturation, accumulation, and translation [22,71-76]. The dramatic proliferation of stem-loop repeats in the Vandenboschia and Equisetum plastomes provides a trigger for their neofunctionalization. For instance, the repeats might involve in the transcriptional and/or post-transcriptional regulation of the neighbor trnY gene.

The IGS of psbM-petN and the occurrence of ycf66

The other highly variable IGS is located between psbM and petN genes (MN-IGS) (Figure 2). The longest MN-IGS (1,788 bp), found in Plagiogyria adnata, is about 8 times longer than the shortest in Psilotum nudum (204 bp). Previous researches documented an open reading frame (ORF) designated ycf66 in the MN-IGS of Angiopteris evecta [28] and a pseudogenized ycf66 copy in both of Alsophila spinulosa [24] and Equisetum arvense [31]. Here we further identified a complete ycf66 in Botrychium virginianum (Ophioglossaceae) and all sampled "non-core" leptosporangiates (Osmundales, Hymenophyllales, Gleicheniales and Schizaeales) (Figure 2). ycf66 appears to be pseudogenized in Helminthostachys zeylanica (Ophioglossaceae), Equisetum, and tree ferns (Figure 2). By contrast, it was undetectable in Ophioglossum vulgatum (Ophioglossaceae), Psilotum, and polypods. Hence ycf66 may have been independently lost at least four times in fern lineages Ophioglossales, Psilotales, Equisetales, and core leptosporangiates. Generally, the MN-IGS containing no ycf66 is shorter than that carrying ycf66 or its pseudogene (Figure 2). For instance, of the three Ophioglossaceous ferns, the MN-IGS sizes of Botrychium (1,393 bp, containing intact ycf66) and Helminthostachys (1,324 bp, containing ycf66 pseudogene) are one time longer that of Ophioglossum (628 bp, containing no ycf66) (Figure 2). The highly unstable occurrence of ycf66 suggests that it seems unessential for the fern plastid function, or it has been transferred to nuclear genome.

Conclusions

The tRNA-rich BZ region of fern plastomes exhibited considerable variation in size, gene order, and repeat content. Here a novel BZ gene order was identified in the tree fern Plagiogyria japonica. Our comparative analysis subsequently showed that the plastomes of extant fern lineages may not contain the putative intermediates of BZ rearrangement, pointing to the conclusion that the Adiantum gene order was generated by two inversions occurring in pairs [33]. The trnY-trnE IGS in the filmy fern Vandenboschia radicans was expanded substantially due to the tandem 27-bp repeats resembling the anticodon domain of trnY. This result provided the first evidence of partial tRNA gene duplication in fern plastomes. In general, the detection of slight length variation in chloroplast IGS region is not uncommon [e.g. [7,10,11,20]]. Nevertheless, it is unprecedented that the Equisetum trnY-trnE IGSs were found to undergo an expansion as large as 5-kb. These IGS sequences were consisted of a large amount of stem-loop repeats, which may also have an evolutionary link to the trnY anticodon domain. In addition, the parallel losses of ycf66 in ferns were corroborated.

Abbreviations

BI: Bayesian inference; BS: Bootstrap; BZ: rpoB to psbZ; cpDNA: chloroplast DNA; D inversion, trnD-GUC inversion; IGS: intergenic spacer; IR: inverted repeat; LSC: large single copy; ML: maximum likelihood; ORF: open reading frame; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; plastome: plastid genome; UTR: untranslated region.

Authors' contributions

LG conceived of the study, participated in its design, performed all sequence analyses and drafted the manuscript. YZ and ZWW participated in the sequencing and helped to draft the manuscript. YJS and TW participated in the design of the study and contributed to the interpretation of the data and prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Additional figure 1. Maximum likelihood (ML) tree of 25 taxa based on 11 plastid gene sequences

Additional figure 2. The predicted promoter sequences upstream of trnD-GUC gene

Additional figure 3. The putative secondary structures of the repeats found by VMATCH in Equisetum ramosissimum

Additional figure 4. The putative secondary structures of the repeats found by VMATCH in Equisetum arvense 1 sequence

Contributor Information

Lei Gao, Email: leigao@wbgcas.cn.

Yuan Zhou, Email: yuan.zhou@wbgcas.cn.

Zhi-Wei Wang, Email: wangzhiwei@wbgcas.cn.

Ying-Juan Su, Email: suyj@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Ting Wang, Email: tingwang@wbgcas.cn.

Acknowledgements and Funding

We thank Hai-Zhou Liu (Wuhan Institute of Virology, CAS) for writing Perl script; Chang-Han Li (South China Botanical Garden, CAS), Zhen-Chuan Chen (Shenzhen Fairy Lake Botanical Garden), and Shou-Jun Zhang and Jia-Rong Zhao (Wuhan Botanical Garden, CAS) for providing samples; Su-Min Guo for helpful communications; the CBSU Web Computing Resources (BioHPC) for running MrBayes. We are also deeply indebted to two anonymous referees for their valuable comments to improve the manuscript. This work was supported by the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Grant KSCX2-YW-Z-0940 to TW, the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 30970290 and 31070594 to TW and 31000171 to YZ.

References

- Raubeson LA, Jansen RK. In: Plant diversity and evolution: genotypic and phenotypic variation in higher plants. Henry RJ, editor. London: CABI Publishing; 2005. Chloroplast genomes of plants; pp. 45–68. full_text. [Google Scholar]

- Guisinger MM, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Extreme reconfiguration of plastid genomes in the angiosperm family Geraniaceae: rearrangements, repeats, and codon usage. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:583–600. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Su Y-J, Wang T. Plastid genome sequencing, comparative genomics, and phylogenomics: current status and prospects. J Syst Evol. 2010;48:77–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-6831.2010.00071.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji S, Ueda K, Nishiyama T, Hasebe M, Yoshikawa S, Konagaya A, Nishiuchi T, Yamaguchi K. The chloroplast genome from a lycophyte (microphyllophyte), Selaginella uncinata, has a unique inversion, transpositions and many gene losses. J Plant Res. 2007;120:281–290. doi: 10.1007/s10265-006-0055-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DR. Unparalleled GC content in the plastid DNA of Selaginella. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;71:627–639. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9545-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakasugi T, Tsudzuki J, Ito S, Nakashima K, Tsudzuki T, Sugiura M. Loss of all ndh genes as determined by sequencing the entire chloroplast genome of the black pine Pinus thunbergii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9794–9798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CS, Lai YT, Lin CP, Wang YN, Chaw SM. Evolution of reduced and compact chloroplast genomes (cpDNAs) in gnetophytes: selection toward a lower-cost strategy. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009;52:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CP, Huang JP, Wu CS, Hsu CY, Chaw SM. Comparative chloroplast genomics reveals the evolution of Pinaceae genera and subfamilies. Genome Biol Evol. 2010;2:504–517. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao T, Watanabe A, Kurita M, Kondo T, Takata K. Complete nucleotide sequence of the Cryptomeria japonica D. Don. chloroplast genome and comparative chloroplast genomics: diversified genomic structure of coniferous species. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy SR, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Raubeson LA. The complete plastid genome sequence of Welwitschia mirabilis: an unusually compact plastome with accelerated divergence rates. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumley TW, Palmer JD, Mower JP, Fourcade HM, Calie PJ, Boore JL, Jansen RK. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pelargonium × hortorum: organization and evolution of the largest and most highly rearranged chloroplast genome of land plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:2175–2190. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberle RC, Fourcade HM, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Extensive rearrangements in the chloroplast genome of Trachelium caeruleum are associated with repeats and tRNA genes. J Mol Evol. 2008;66:350–361. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosner ME, Raubeson LA, Jansen RK. Chloroplast DNA rearrangements in Campanulaceae: phylogenetic utility of highly rearranged genomes. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai ZQ, Guisinger M, Kim HG, Ruck E, Blazier JC, McMurtry V, Kuehl JV, Boore J, Jansen RK. Extensive reorganization of the plastid genome of Trifolium subterraneum (Fabaceae) is associated with numerous repeated sequences and novel DNA insertions. J Mol Evol. 2008;67:696–704. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen RK, Wojciechowski MF, Sanniyasi E, Lee SB, Daniell H. Complete plastid genome sequence of the chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and the phylogenetic distribution of rps12 and clpP intron losses among legumes (Leguminosae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;48:1204–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HL, Jansen RK, Chumley TW, Kim KJ. Gene relocations within chloroplast genomes of Jasminum and Menodora (Oleaceae) are due to multiple, overlapping inversions. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1161–1180. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawata M, Harada T, Shimamoto Y, Oono K, Takaiwa F. Short inverted repeats function as hotspots of intermolecular recombination giving rise to oligomers of deleted plastid DNAs (ptDNAs) Curr Genet. 1997;31:179–184. doi: 10.1007/s002940050193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe CJ. The endpoints of an inversion in wheat chloroplast DNA are associated with short repeated sequences containing homology to att-lambda. Curr Genet. 1985;10:139–145. doi: 10.1007/BF00636479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maréchal A, Brisson N. Recombination and the maintenance of plant organelle genome stability. New Phytol. 2010;186:299–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maul JE, Lilly JW, Cui L, dePamphilis CW, Miller W, Harris EH, Stern DB. The Chlamydomonas reinhardtii plastid chromosome: islands of genes in a sea of repeats. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2659–2679. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipkins VD, Marshall KA, Neale DB, Rottmann WH, Strauss SH. A mutation hotspot in the chloroplast genome of a conifer (Douglas-fir: Pseudotsuga) is caused by variability in the number of direct repeats derived from a partially duplicated tRNA gene. Curr Genet. 1995;27:572–579. doi: 10.1007/BF00314450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao HS, Hicks A, Simpson C, Stern DB. Short dispersed repeats in the Chlamydomonas chloroplast genome are collocated with sites for mRNA 3' end formation. Curr Genet. 2004;45:311–322. doi: 10.1007/s00294-004-0487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom OW, Baek KH, Dani RN, Herrin DL. Chlamydomonas chloroplasts can use short dispersed repeats and multiple pathways to repair a double-strand break in the genome. Plant J. 2008;53:842–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Yi X, Yang YX, Su YJ, Wang T. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a tree fern Alsophila spinulosa: insights into evolutionary changes in fern chloroplast genomes. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouard JS, Otis C, Lemieux C, Turmel M. The exceptionally large chloroplast genome of the green alga Floydiella terrestris illuminates the evolutionary history of the Chlorophyceae. Genome Biol Evol. 2010;2:240–256. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell SW, Schneider H, Pedersen N, Grundmann M, Russell SJ, Vogel JC. Recombination diversifies chloroplast trnF pseudogenes in Arabidopsis lyrata. J Evol Biol. 2007;20:2400–2411. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf PG, Rowe CA, Sinclair RB, Hasebe M. Complete nucleotide sequence of the chloroplast genome from a leptosporangiate fern, Adiantum capillus-veneris L. DNA Res. 2003;10:59–65. doi: 10.1093/dnares/10.2.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper JM, Kellon Hansen S, Wolf PG, Karol KG, Mandoli DF, Everett KDE, Kuehl J, Boore JL. The complete plastid genome sequence of Angiopteris evecta (G. Forst.) Hoffm. (Marattiaceae) Am Fern J. 2007;97:95–106. doi: 10.1640/0002-8444(2007)97[95:TCPGSO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wakasugi T, Nishikawa A, Yamada K, Sugiura M. Complete nucleotide sequence of the plastid genome from a fern, Psilotum nudum. Endocyt Cell Res. 1998;13(Suppl):147. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf PG, Der JP, Duffy AM, Davidson JB, Grusz AL, Pryer KM. The evolution of chloroplast genes and genomes in ferns. Plant Mol Biol. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Karol K, Arumuganathan K, Boore J, Duffy A, Everett K, Hall J, Hansen S, Kuehl J, Mandoli D, Mishler B. et al. Complete plastome sequences of Equisetum arvense and Isoetes flaccida: implications for phylogeny and plastid genome evolution of early land plant lineages. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:321. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der JP. PhD thesis. Utah State University, Department of Biology; 2010. Genomic perspectives on evolution in bracken fern. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf PG, Roper JM, Duffy AM. The evolution of chloroplast genome structure in ferns. Genome. 2010;53:731–738. doi: 10.1139/G10-061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe M, Iwatsuki K. Chloroplast DNA from Adiantum capillus-veneris L., a fern species (Adiantaceae); clone bank, physical map and unusual gene localization in comparison with angiosperm chloroplast DNA. Curr Genet. 1990;17:359–364. doi: 10.1007/BF00314885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe M, Iwatsuki K. Journal of Plant Research. 3. Vol. 105. Japan; 1992. Gene localization on the chloroplast DNA of the maiden hair fern; Adiantum capillus-veneris; pp. 413–419. [Google Scholar]

- Raubeson LA, Jansen RK. Chloroplast DNA evidence on the ancient evolutionary split in vascular land plants. Science. 1992;255:1697–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.255.5052.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AR, Pryer KM, Schuettpelz E, Korall P, Schneider H, Wolf PG. A classification for extant ferns. Taxon. 2006;55:705–731. doi: 10.2307/25065646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. A contig assembly program based on sensitive detection of fragment overlaps. Genomics. 1992;14:18–25. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laslett D, Canback B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:11–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BPROM. http://linux1.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=bprom&group=programs&subgroup=gfindb

- Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Vmatch large scale sequence analysis software. http://www.vmatch.de/

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwickl DJ. PhD thesis. The University of Texas at Austin; 2006. Genetic algorithm approaches for the phylogenetic analysis of large biological sequence datasets under the maximum likelihood criterion. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (and Other Methods) 4.0 Beta. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tracer. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/

- Korall P, Pryer KM, Metzgar JS, Schneider H, Conant DS. Tree ferns: monophyletic groups and their relationships as revealed by four protein-coding plastid loci. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;39:830–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y-L, Li L, Wang B, Chen Z, Dombrovska O, Lee J, Kent L, Li R, Jobson RW, Hendry TA. et al. A nonflowering land plant phylogeny inferred from nucleotide sequences of seven chloroplast, mitochondrial, and nuclear genes. Int J Plant Sci. 2007;168:691–708. doi: 10.1086/513474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y-L, Li L, Wang B, Chen Z, Knoop V, Groth-Malonek M, Dombrovska O, Lee J, Kent L, Rest J. et al. The deepest divergences in land plants inferred from phylogenomic evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15511–15516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603335103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H, Schuettpelz E, Pryer KM, Cranfill R, Magallon S, Lupia R. Ferns diversified in the shadow of angiosperms. Nature. 2004;428:553–557. doi: 10.1038/nature02361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryer KM, Schuettpelz E, Wolf PG, Schneider H, Smith AR, Cranfill R. Phylogeny and evolution of ferns (monilophytes) with a focus on the early leptosporangiate divergences. Am J Bot. 2004;91:1582–1598. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.10.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettpelz E, Pryer KM. Fern phylogeny inferred from 400 leptosporangiate species and three plastid genes. Taxon. 2007;56:1037–1050. doi: 10.2307/25065903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettpelz E, Pryer KM. Evidence for a Cenozoic radiation of ferns in an angiosperm-dominated canopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11200–11205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811136106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai HS, Graham SW. Utility of a large, multigene plastid data set in inferring higher-order relationships in ferns and relatives (monilophytes) Am J Bot. 2010;97:1444–1456. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryer KM, Schneider H, Smith AR, Cranfill R, Wolf PG, Hunt JS, Sipes SD. Horsetails and ferns are a monophyletic group and the closest living relatives to seed plants. Nature. 2001;409:618–622. doi: 10.1038/35054555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe M, Wolf PG, Pryer KM, Ueda K, Ito M, Sano R, Gastony GJ, Yokoyama J, Manhart JR, Murakami N. et al. Fern phylogeny based on rbcL nucleotide sequences. Am Fern J. 1995;85:134–181. doi: 10.2307/1547807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wikström N, Pryer KM. Incongruence between primary sequence data and the distribution of a mitochondrial atp1 group II intron among ferns and horsetails. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;36:484–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf PG, Sipes SD, White MR, Martines ML, Pryer KM, Smith AR, Ueda K. Phylogenetic relationships of the enigmatic fern families Hymenophyllopsidaceae and Lophosoriaceae: evidence from rbcL nucleotide sequences. Plant Syst Evol. 1999;219:263–270. doi: 10.1007/BF00985583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelchner SA. The evolution of non-coding chloroplast DNA and its application in plant systematics. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 2000;87:482–498. doi: 10.2307/2666142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohme M, Kamogashira T, Shinozaki K, Sugiura M. Structure and cotranscription of tobacco chloroplast genes for tRNAGlu(UUC), tRNATyr(GUA) and tRNAAsp(GUC) Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:1045–1056. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.4.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plader W, Yukawa Y, Sugiura M, Malepszy S. The complete structure of the cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) chloroplast genome: its composition and comparative analysis. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2007;12:584–594. doi: 10.2478/s11658-007-0029-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao DC, Huang BL, Chen SL, Mu J. Evolution of the chloroplast trnL-trnF region in the gymnosperm lineages Taxaceae and Cephalotaxaceae. Biochem Genet. 2009;47:351–369. doi: 10.1007/s10528-009-9233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Lee HL. Complete chloroplast genome sequences from Korean ginseng (Panax schinseng Nees) and comparative analysis of sequence evolution among 17 vascular plants. DNA Res. 2004;11:247–261. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Z, Eibl C, Koop HU. The stem-loop region of the tobacco psbA 5'UTR is an important determinant of mRNA stability and translation efficiency. Mol Genet Genomics. 2003;269:340–349. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0842-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suay L, Salvador ML, Abesha E, Klein U. Specific roles of 5' RNA secondary structures in stabilizing transcripts in chloroplasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4754–4761. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rott R, Liveanu V, Drager RG, Stern DB, Schuster G. The sequence and structure of the 3'-untranslated regions of chloroplast transcripts are important determinants of mRNA accumulation and stability. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;36:307–314. doi: 10.1023/A:1005943701253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori M, Sugita M. A moss pentatricopeptide repeat protein binds to the 3' end of plastid clpP pre-mRNA and assists with mRNA maturation. FEBS J. 2009;276:5860–5869. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern DB, Radwanski ER, Kindle KL. A 3' stem/loop structure of the Chlamydomonas chloroplast atpB gene regulates mRNA accumulation in vivo. Plant Cell. 1991;3:285–297. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.3.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern DB, Gruissem W. Control of plastid gene expression: 3' inverted repeats act as mRNA processing and stabilizing elements, but do not terminate transcription. Cell. 1987;51:1145–1157. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90600-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional figure 1. Maximum likelihood (ML) tree of 25 taxa based on 11 plastid gene sequences

Additional figure 2. The predicted promoter sequences upstream of trnD-GUC gene

Additional figure 3. The putative secondary structures of the repeats found by VMATCH in Equisetum ramosissimum

Additional figure 4. The putative secondary structures of the repeats found by VMATCH in Equisetum arvense 1 sequence