Abstract

Recent studies have shown that leptin (an adipocytokine) played an important role in nociceptive behavior induced by nerve injury, but the cellular mechanism of this action remains unclear. Using the whole cell patch-clamp recording from rat’s spinal cord slices, we showed that superfusion of leptin onto spinal cord slices dose-dependently enhanced NMDA receptor-mediated currents in spinal cord lamina II neurons. At the cellular level, the effect of leptin on spinal NMDA-induced currents was mediated through the leptin receptor and the JAK2/STAT3 (but not PI3K or MAPK) pathway, as the leptin effect was abolished in leptin receptor deficient (db/db) mice and inhibited by a JAK/STAT inhibitor. Moreover, we demonstrated in naïve rats that a single intrathecal administration of leptin enhanced spontaneous biting, scratching and licking behavior induced by intrathecal NMDA and that repeated intrathecal administration of leptin elicited thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia, which was attenuated by the non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801. Intrathecal leptin also upregulated the expression of NMDA receptors and pSTAT3 within the rat’s spinal cord dorsal horn and intrathecal MK-801 attenuated this leptin effect as well. Our data demonstrate a relationship between leptin and NMDA receptor-mediated spinal neuronal excitation and its functional role in nociceptive behavior. Since leptin contributes to nociceptive behavior induced by nerve injury, the present findings suggest an important cellular link between the leptin’s spinal effect and the NMDA receptor-mediated cellular mechanism of neuropathic pain.

Keywords: Leptin, NMDA receptor, Neuropathic pain, JAK2/STAT3, Patch-clamp recording, Hyperalgesia, Allodynia

1. Introduction

Pain resulting from injury or disease of the nervous system (neuropathic pain) is a debilitating chronic pain condition involving both peripheral and central mechanisms [10,36,64,66]. Recent studies have shown that leptin, an adipocytokine, played a significant role in nociceptive behavior induced by nerve injury in rats [31,35]. While the peripheral effect of leptin on neuropathic pain is mediated via macrophage stimulation [35], its central effect is likely related to the upregulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR) following nerve injury [31]. To date, the exact cellular mechanism of the leptin action in neuropathic pain remains unclear.

Leptin is a 16-kDa adipocytokine produced mainly by white adipose tissue and is well known for its role in metabolic regulation and obesity [1,11,12,50,68]. Several studies indicate that leptin has a broad role in the regulation of neuronal functions [2,22], which is believed to be mediated by a long form leptin receptor (Ob-Rb) resulting in Janus tyrosine kinase 2 (JAK2)-mediated phosphorylation of tyrosine residues within the cytoplasmic tail of the Ob-Rb receptor [40]. This cellular effect, in turn, recruits and activates downstream signaling pathways including the STAT3 (signal transducers and activators of transcription factors 3) pathway, insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins and its downstream phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), and/or the Ras-Raf-MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) signaling cascade [3,21].

Recent studies have also suggested a possible functional link between leptin and NMDAR. For example, exposure to leptin enhanced NMDAR activity and modulated NMDAR-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP) in an in vitro hippocampal preparation [51], whereas administration of leptin into the hippocampal dentate gyrus enhanced LTP in vivo [61]. Genetically obese rodents with dysfunctional leptin receptors displayed impairments in both NMDAR-dependent hippocampal long-term depression (LTD) and LTP [29,16]. Moreover, repeated leptin administration during the early stage of life altered both the short-term and long-term expression of NMDAR, synaptic proteins and LTP in the rat’s hippocampus [57].

Since activation of NMDAR plays a crucial role in the mechanisms of peripheral and central sensitization [7,8,36,45] and NMDAR antagonist alleviated nociceptive behavior in preclinical studies and neuropathic pain in clinical studies [14,23,36,64], we hypothesized that the role of leptin in neuropathic pain would be mediated, at least partially, through its regulatory effect on NMDAR at the spinal level. Accordingly, in this study we examined 1) whether leptin would regulate NMDAR-mediated spinal neuronal excitation and 2) the interaction between leptin and NMDAR would play a functional role in nociceptive behavior in rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Experimental animals

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats of 4~6 weeks (for electrophysiological experiments) or weighing 280~300 gm (for behavioral experiments) were purchased from the Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). db/db (B6.BKS(D)−Leprdb/J; deficient in leptin receptors) and wild-type (C57BL/6J) male mice at 4–6 weeks of age were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The animal room was artificially lit from 7 A.M. to 7 P.M. and water and food pellets were available ad libitum. The experimental protocol was approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All behavioral experiments were carried out with the investigators being blinded to treatment conditions.

2.2 Drugs

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), glycine, tetrodotoxin (TTX), strychnine, bicuculline methchloride, a-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), (+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo(a, b)cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate (MK-801), D-(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP5), 2,3-dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo [f] quinoxaline -7-sulfonamide (NBQX), LY-294,002 hydrochloride (PI3K inhibitor), PD 98,059 (MAPK inhibitor), and AG 490 (JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Leptin and NR1 or pSTAT3 antibodies were purchased from Abcam (San Francisco, CA). NBQX, LY-294,002, PD 98,059 and AG 490 were first dissolved in 5% DMSO or ethanol diluted with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) to final concentrations. The final concentration of DMSO or ethanol in a solution was less than 0.1%. MK-801 was diluted with saline. Accordingly, saline or corresponding concentration of DMSO or ethanol was used as vehicle.

2.3 Preparation of spinal cord slices

Spinal cord slices were prepared from postnatal day 4~6 weeks old SD rats or 4~6 weeks old db/db or wide-type mice. After anesthesia with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg, i.p.), laminectomy was performed and a portion of lumbar spinal cord (L4~L5) was rapidly removed and placed in a chilled, oxygenated ACSF containing the following compositions (mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, and 25 d-glucose. Transverse slices (400 µm) were cut on a vibratome (Vibratome, IL). Spinal cord slices were then incubated in the oxygenated ACSF at 35°C for half an hour and then at room temperature for at least 1 h before recording.

2.4 Electrophysiological recording

The whole-cell patch clamp recordings were made from lamina II (substantia gelatinosa) neurons. Slices were placed in a recording chamber mounted onto the stage of an upright microscope (Olympus, Japan) and perfused with ACSF (2~3 ml/min). The substantia gelatinosa was clearly visible as a relatively translucent band across the spinal cord dorsal horn under a low magnification microscopic view. Patch pipettes, with resistance of 3~5MΩ, were made from thick-walled, borosilicate, glass-capillary tubing (1.5 mm outer diameter). The internal solution contained the following (mM): 140 K-gluconate, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 11 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 5 Mg-ATP, and 0.5 Na-GTP, pH 7.3. Only neurons that had an apparent resting membrane potential more negative than −50 mV and produced normal action potentials after injection of depolarizing currents (25~200 pA in 25 pA steps for 1 s) were further investigated [18,47].

NMDA currents were evoked by ejecting 50 µM NMDA plus 10 µM glycine in Mg2+-free ACSF for 30 seconds at a holding potential of −70 mV (Stoelting, WI). One µM strychnine, 10 µM bicuculline, 10 µM NBQX, and 1 µM TTX were added to bathing solution to block glycine receptors, GABAA receptors, AMPA receptors and voltage-gated sodium channels. Once the baseline NMDA current was acquired, leptin was bath-applied for 5 minutes. Recordings were made using an Axopatch 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, CA). Signals were filtered at 2 kHz, digitized at 10 kHz, acquired using a personal computer and pClamp software (version 9.2; Molecular Devices, CA), and stored for later analysis. Input resistance was monitored throughout the experiments. The mean series resistance for all cells was 25~35 MΩ and the currents noise was less than 10pA. All experiments were performed at room temperature (22~25°C).

2.5 Intrathecal catheterization and drug delivery

Rats weighing 280~300 gm were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.) and implanted with an intrathecal catheter (PE-10 tube, about 8.5 cm from the incision site for this rat age group) for drug delivery according to the method described previously [37]. Intrathecal injection (i.t.) was performed using a microsyringe (50 µl) in a 10-µl volume followed by 10 µl of saline to flush the catheter dead space. To examine the effect of leptin on NMDA-induced biting, scratching and licking behaviors (BSL) [4,46], a single dose of NMDA (1 µg, i.t.) was injected 30 min after a single treatment of saline or leptin (50 µg, i.t.). To examine whether leptin-induced nociceptive behavior in naïve rats [31] could be reversed by the non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801, leptin (50 µg), MK-801 (10 nmol), leptin plus MK-801, or saline was injected intrathecally once daily for 14 days. The dose for each drug was selected according to the literature [31,36,46,59] and our own pilot experiment.

2.6 Behavioral tests

Animals were habituated to the test environment for two consecutive days (60 min per session per day) before the baseline testing. (1) Mechanical allodynia was examined by using von Frey filaments applied to the plantar surface of each hindpaw [52]. A positive response was defined as hindpaw withdrawal from at least one out of three applications with a von Frey filament and the threshold force was determined by an up-and-down method [37]. (2) Thermal hyperalgesia to radiant heat was assessed using the foot-withdrawal test [19]. Each animal underwent 3 trials and the results from these trials were averaged to yield mean withdrawal latencies. The cutoff was set at 20 seconds to avoid tissue damage. (3) NMDA-induced biting, scratching and licking behaviors were observed immediately after a rat received the intrathecal NMDA injection and then placed in a plastic cage. The latency, number and duration of biting, scratching, and licking behaviors directed toward the hindlimb, gluteal region and the tail were recorded for a 10-minute period after the NMDA injection [4,46]. All behavioral tests were conducted between 9 AM and noon.

2.7 Immunohistochemistry

Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with 200 ml of normal saline followed by 200~300 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). Lumbar spinal cords were dissected, post-fixed for 1.5 hours, and kept overnight in 30% sucrose in 0.1 M PB. Tissues from both experimental and control groups were then mounted together in OCT compound and frozen on dry ice. Spinal cords (25 µm sections) were cut on a cryostat. Sections were blocked with 4% goat serum in 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4°C with one of the following primary antibodies: NR1: 1:100, rabbit polyclonal; pSTAT3: 1:200, rabbit polyclonal. Sections were then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with cyanine 3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:300). For controls, primary antibodies were omitted in the process. Four to six nonadjacent spinal cord sections were randomly selected and examined with an Olympus fluorescence microscope, and images were captured with a digital camera (Olympus) and analyzed with Adobe PhotoShop.

2.8 Western blot analysis

Animals were sacrificed by decapitation under pentobarbital anesthesia. The lumbar spinal cord dorsal horn was harvested and homogenized in an SDS buffer containing a mixture of proteinase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were separated on an SDS-PAGE gel (4%–15% gradient gel; Bio-Rad) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk and incubated overnight (4°C) with one of the following primary antibodies: NR1: 1:500, rabbit polyclonal; pSTAT3: 1:10000, rabbit polyclonal. Membranes were then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:8,000; Amersham). Blots were visualized in ECL solution (PerkinElmer) for 5 minutes and exposed to hyperfilms (Amersham) for 1–10 minutes. Blots were again incubated in a stripping buffer (67.5 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, and 0.7% β-mercaptoethanol) for 30 minutes at 50 °C and reprobed with an anti-β-actin antibody (1:15,000, mouse monoclonal; Abcam) as loading control. Western blots were made in triplicates. Band density was measured and normalized against each loading control band.

2.9 Statistics

Data from both thermal hyperalgesia (withdrawal latency in seconds) and mechanical allodynia (threshold bending force in grams) tests were analyzed by using repeated measure two-way ANOVA across testing time points to detect overall differences among treatment groups. Whenever applicable, the data were also examined by using repeated measure two-way ANOVA across treatment groups to examine overall differences among testing time points. In both cases, when significant main effects were observed, the post hoc Newman–Keuls tests were performed to determine the source(s) of differences. The experimenters were blinded to treatment conditions. All results were expressed as mean ± S.E. and differences were considered to be statistically significant at the level of α=0.05. For all other experiments, differences were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Newman–Keuls tests in SPSS 17.0 for Windows.

3. Results

3.1 Acute enhancement by leptin of NMDA-induced currents in lamina II neurons

The substantia gelatinosa (SG, lamina II) of the spinal cord dorsal horn has been implicated in nociceptive transmission because both finely myelinated (Aδ) and unmyelinated (C) primary nociceptive afferent fibres are heavily projected to this spinal region [26,30,63,67]. Therefore, in this study we focused on examining whether leptin would regulate NMDAR-mediated currents in SG neurons. SG neurons were identified in response to 1 s depolarizing current injections of different intensities according to Ruscheweyh and Sandkühler [47]. A total of 105 SG neurons were identified, among which 47% were tonic-firing, 5% delayed-firing, 14% phasic-bursting, 12% initial bursting, and 22% single-spiking [17,18,47,48,63,67].

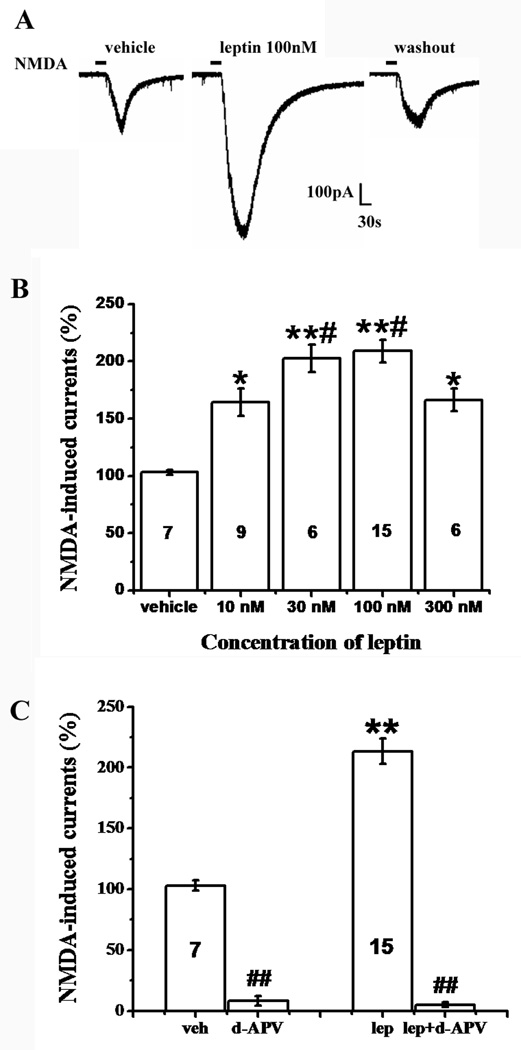

Among all SG neurons identified by the current injections, we completed the entire set of recording in 43 SG neurons to examine whether leptin would enhance NMDA-induced currents. NMDA-induced currents were evoked by ejecting 50 µM NMDA plus 10 µM glycine in Mg2+-free ACSF for 30 seconds at a holding potential of −70 mV. The amplitude of NMDA-induced currents ranged from 50 pA to 500 pA with a mean of 186.32 ± 20.16 pA (Fig. 1A). Exposure to leptin for 5 min markedly enhanced NMDA-induced currents in 36 out of 43 (84%) SG neurons (Fig. 1A, 1B). This enhancement of NMDA currents returned to the baseline after leptin was washed out for 30 min (Fig. 1A). Exposure to vehicle (ACSF) for 5 min had no effect on subsequent NMDA-induced currents (n=7, P>0.05, Fig. 1B). The leptin effect on NMDA-induced currents was dependent on leptin concentrations (10nM – 300 nM) and the maximal enhancement occurred at 100 nM of leptin (Fig. 1B). This concentration (100 nM) of leptin was used in subsequent electrophysiological experiments.

Fig. 1. Enhancement by leptin of NMDA-induced currents.

A, NMDA-induced current was enhanced in the presence of leptin (100 nM, 5min) and recovered at 30 minutes after leptin washout. B, The facilitatory effect of leptin on NMDA-induced currents was concentration-dependent. Leptin at 100 nM had the maximal enhancement effect. C, The enhancement by leptin of NMDA-currents was mediated through the NMDAR. The NMDAR antagonist d-APV (100µM) blocked NMDA-induced currents with or without leptin perfusion (n=6). Data are shown as mean±S.E. The number of cells in each group was shown inside each column. veh, vehicle; lep, leptin. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus vehicle; #P < 0.05 versus 10 nM and 300 nM leptin; $$P<0.01 versus before d-APV perfusion.

Of interest, leptin enhanced SG neurons of all firing patterns except for those neurons with a delayed firing pattern (Table 1), suggesting a facilitatory effect of leptin on primarily excitatory SG neurons [48]. Moreover, at the concentration of 100 µM, the competitive NMDAR antagonist d-APV blocked NMDA-induced currents with or without the presence of leptin (n=6, P<0.01; Fig. 1C), indicating that leptin-enhanced NMDA currents were mediated by the NMDAR.

Table 1.

Response to leptin in SG neurons with characteristic firing patterns

| Response to Leptin |

Tonic Firing |

Delayed Firing |

Phasic Firing |

Initial Firing |

Single Firing |

Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced | 12 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 36 | 84 |

| No Response | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 16 |

| Total | 14 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 43 | 100 |

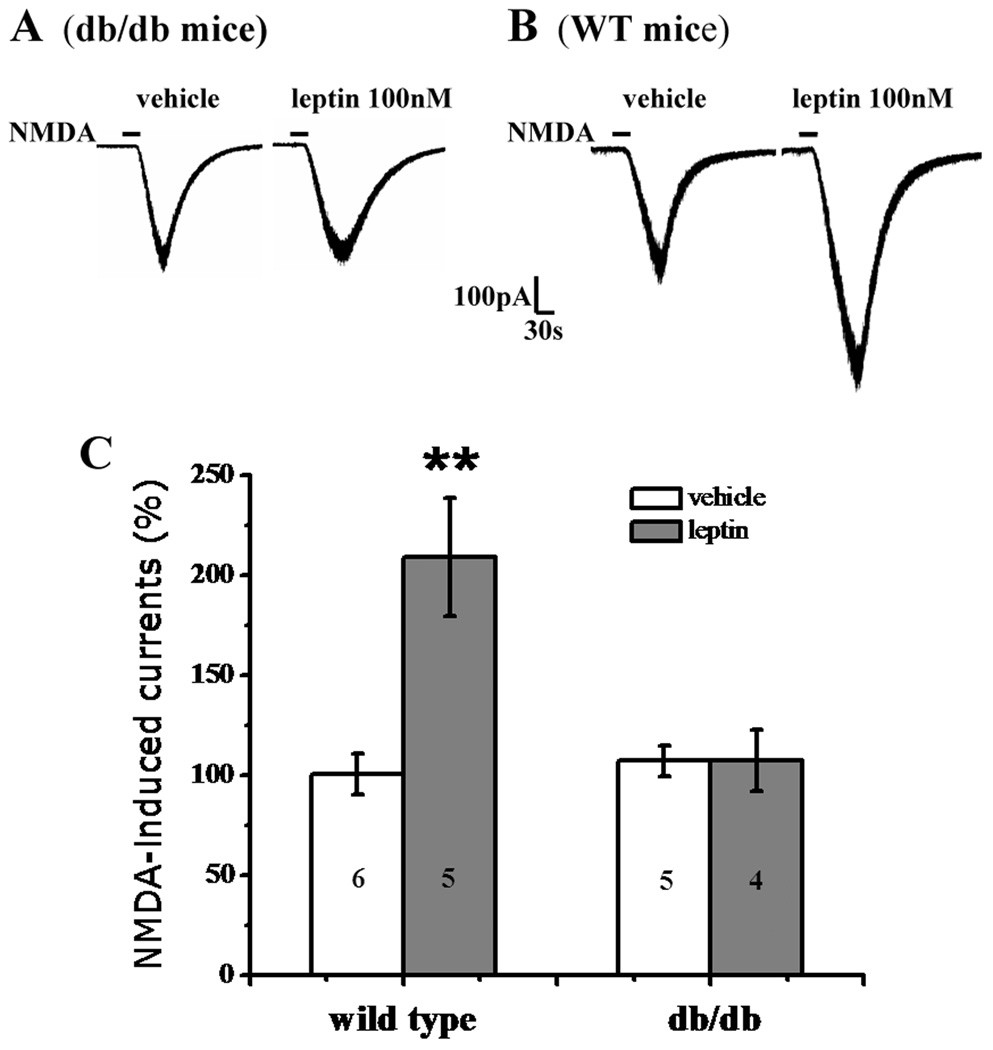

3.2 Lack of spinal leptin effect in (db/db) mice deficient in leptin receptors

To examine whether leptin enhanced NMDA-induced currents via its receptors [40], we repeated the above whole-cell patch clamp recording protocol in leptin receptor deficient db/db mice [5,28]. Application of leptin (100 nM) for 5min failed to increase NMDA-induced currents in SG neurons of db/db mice (n=4, P>0.05; Fig. 2A, 2C), although leptin effectively enhanced NMDA-induced currents in SG neurons of matched wide-type mice (n=5, P<0.01; Fig. 2B, 2C). The data indicates that the effect of leptin on spinal NMDA currents was mediated through leptin receptors.

Fig. 2. Lack of leptin effect in db/db mice.

A, B, Representative traces showing the enhancement by leptin (100 nM, 5 min) of NMDA-induced currents in wild-type mice (B) but not in db/db mice (A). C, Histograms showing changes in NMDA currents in db/db mice and wild-type mice. Data are shown as mean±S.E. The number of cells in each group was shown inside each column. **P < 0.01 versus vehicle.

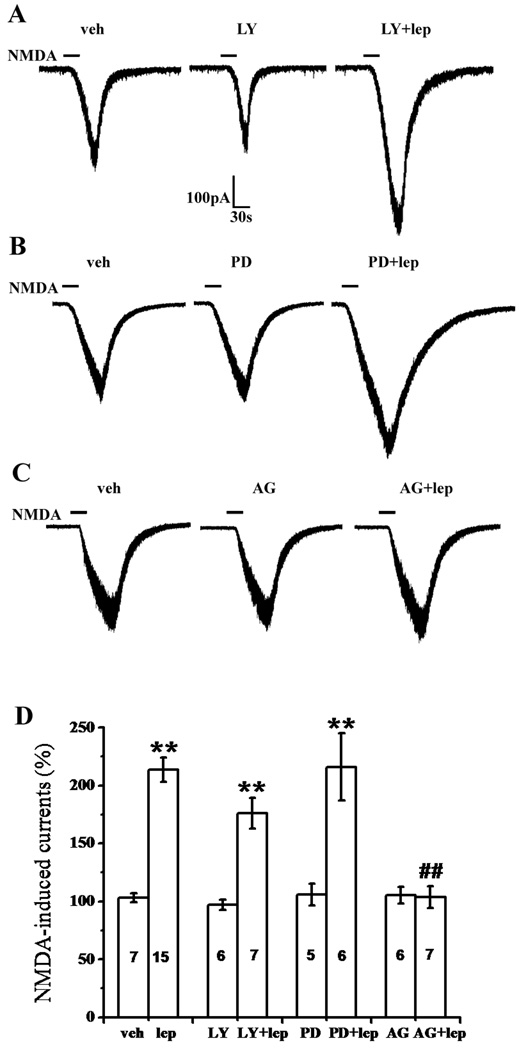

3.3 Role of the JAK2/STAT3, PI3K, and MAPK pathways in acute spinal leptin effect

At least three signaling pathways have been implicated in the broad leptin effect, including JAK2/STAT3, PI3K, and MAPK pathways [41]. We therefore examined whether the JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor AG 490, PI3K inhibitor LY-294,002, or MAPK inhibitor PD 98,059 [51] could attenuate the leptin effect on spinal NMDA-induced currents. Co-application of 10 µM LY-294,002 (n=7) or 10 µM PD 98,059 (n=6) with 100 nM leptin for 5 min did not change the leptin effect on NMDA-induced currents in SG neurons (P>0.05, Fig. 3A, 3B, 3D).

Fig. 3. Role of the JAK2/STAT3 signal pathway in leptin-enhanced NMDA current.

A, B, C, Representative traces showing the effect of the PI3K inhibitor LY-294,002 (A), MAPK inhibitor PD 98,059 (B), and JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor AG 490 (C) on the facilitation by leptin (100 nM, 5 min) of NMDA-induced currents. D, Histograms showing the effect of LY-294,002, PD 98,059, and AG 490 on the leptin effect on NMDA-induced currents. Data are shown as mean±S.E. The number of cells in each group was shown inside each column. veh, vehicle; lep, leptin; LY, LY-294,002; PD, PD 98,059; AG, AG 490. **P < 0.01 versus vehicle, ##P < 0.01 versus leptin.

In contrast, co-application of leptin (100 nM) with AG 490 (10 µM) for 5 min significantly attenuated the enhancement by leptin of NMDA-induced currents in SG neurons (n=7, P<0.01), whereas application of AG 490 (10µM) alone for 5 min had no effect on the basal level of NMDA-induced currents (n=6, P>0.05, Fig. 3C, 3D). These results indicate that the leptin effect on spinal NMDA-induced currents is primarily mediated through the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, but not the PI3K or MAPK pathway.

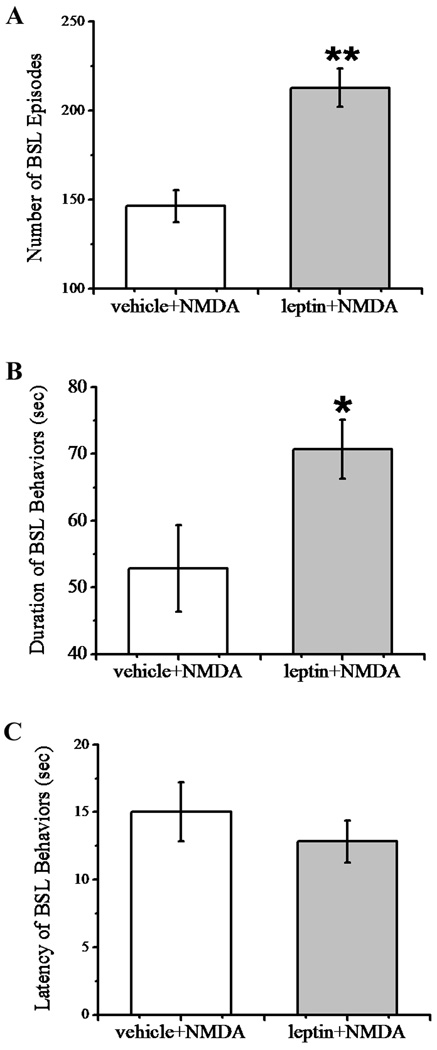

3.4 Enhancement by leptin of NMDA-induced biting, scratching and licking behavior

To determine the functional role of the acute leptin effect on NMDA-induced currents, we examined whether leptin would modulate intrathecal NMDA-induced biting, scratching and licking (BSL) behaviors [4,46]. In this experiment, rats received a single intrathecal pretreatment with either vehicle or leptin (50 µg) at 30 min before the intrathecal injection of NMDA (1 µg). Vehicle or leptin injection alone did not induce BSL behaviors in these rats. While intrathecal administration of NMDA elicited BSL behaviors directed toward the hindlimb, gluteal region, and base of the tail, which lasted for less than one minute in the absence of leptin (Fig. 4A, 4B), intrathecal pretreatment with leptin significantly increased both the number and duration of BSL episodes as compared with the vehicle pretreatment group (Fig. 4A, 4B; n=6, P<0.05–0.01). In addition, the onset of BSL behaviors was also slightly shortened in the leptin pretreatment group although it did not reach the statistical significance as compared with the vehicle pretreatment group (Fig. 4C; n=6, P>0.05). These results demonstrate an acute spinal effect of leptin on NMDA-induced behavioral responses.

Fig. 4. Enhancement by leptin of NMDA-induced BSL behaviors.

Intrathecal administration of NMDA (1 µg) elicited biting, scratching and licking (BSL) behaviors. The number of BSL episodes (A) and duration of BSL (B) induced by NMDA were increased by the pretreatment of 50 µg leptin (n=6, *P<0.05, ** P<0.01). (C) Pretreatment of leptin did not significantly change the latency of NMDA-induced BSL behaviors (n=6, P>0.05).

3.5 Blockade by MK-801 of leptin-induced thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia

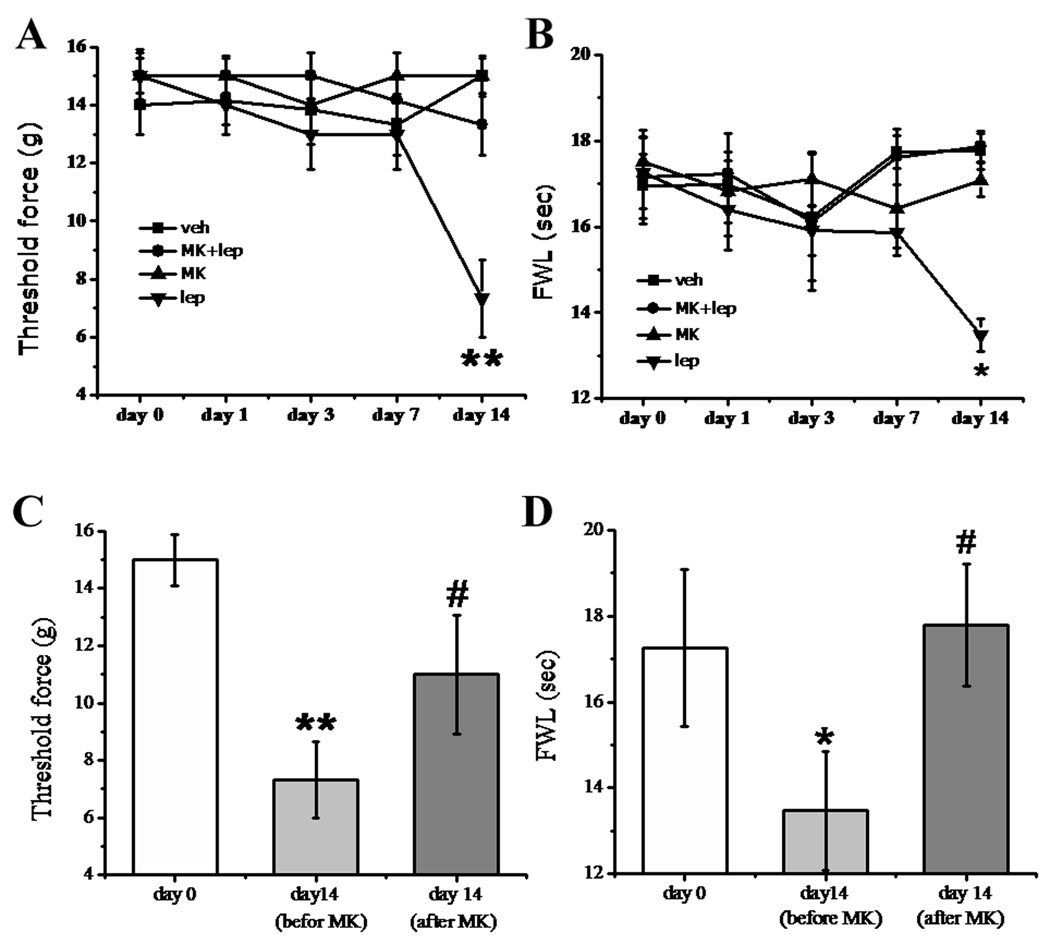

Our previous studies have shown that levels of both leptin and the long form of the leptin receptor (Ob-Rb) were substantially increased within the ipsilateral spinal cord dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury, and spinal administration of exogenous leptin in naive rats induced thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia, similar to the behavior induced by nerve injury [31]. Here, we examined whether leptin-induced nociceptive behaviors were mediated through NMDAR. In the first experiment, we examined whether MK-801 could prevent the development of hyperalgesia and allodynia induced by intrathecal leptin administration. Four groups of naïve rats received (a) vehicle, (b) 50 µg leptin alone, (c) 50 µg leptin plus 10 nmol MK-801, or (d) 10 nmol MK-801 alone. All treatments were given intrathecally once daily for 14 days and behavioral tests were made on day 0, 1, 3, 7, and 14. Rats receiving leptin demonstrated mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia when examined on day 14, as compared with the vehicle group (Fig. 5A, 5B, n = 5, P < 0.05 – 0.01). MK-801 alone did not change the baseline nociceptive threshold, but attenuated leptin induced nociceptive behaviors when co-administered with leptin for 14 days (Fig. 5A, 5B, n = 5, P > 0.05).

Fig. 5. Effect of MK-801 on the role of leptin in hyperalgesia and allodynia.

A, B: Intrathecal leptin (50 µg) in naïve rats, given once daily for 14 days, induced mechanical allodynia (A) and thermal hyperalgesia (B) when examined on day 14. The behavioral change was attenuated by coadministration of leptin with the NMDAR antagonist MK-801 (10 nmol) for 14 days. MK-801 (10 nmol) alone did not change the baseline nociceptive response. C, D: A single injection with MK-801 (10 nmol) on day 14 reversed both mechanical allodynia (C) and thermal hyperalgesia (D) induced by intrathecal leptin (50 µg, once daily) for 14 days. The data was obtained at 30 minutes after the MK-801 treatment. Data are shown as mean±S.E. veh, vehicle; lep, leptin; MK, MK-801. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus day 0; #P < 0.05 versus before the MK-801 injection on day 14. FWL: foot-withdrawal latency.

In the second experiment, we examined whether MK-801 could reverse hyperalgesia and allodynia induced by repeated exposure to leptin. A single intrathecal injection with MK-801 (10 nmol) on day 14 reversed both mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia that developed following a 14-day intrathecal leptin (50 µg) treatment regimen (Fig 5C, 5D, n = 5, P < 0.05). The data indicate that NMDAR played a significant role in thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia induced by repeated treatment of spinal leptin in naïve rats.

3.6 Prevention by MK-801 of leptin-induced spinal NMDAR and pSTAT3 upregulation

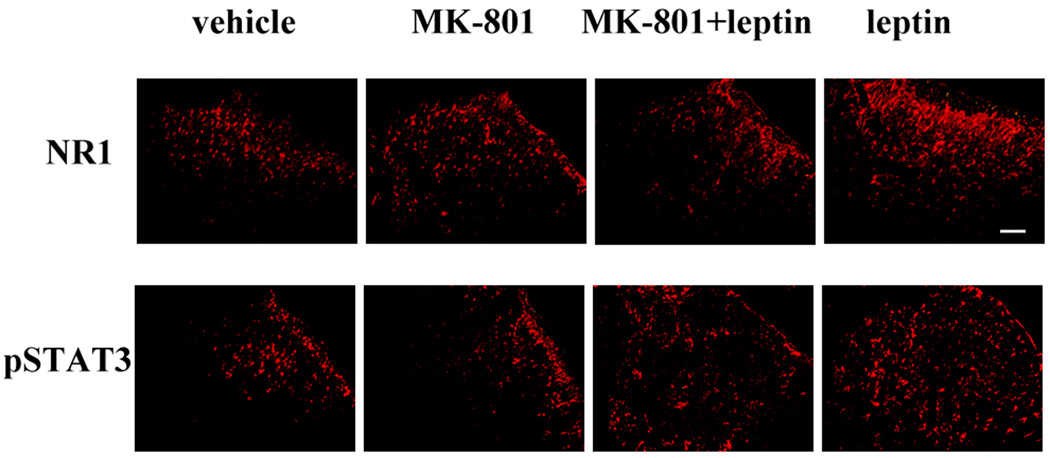

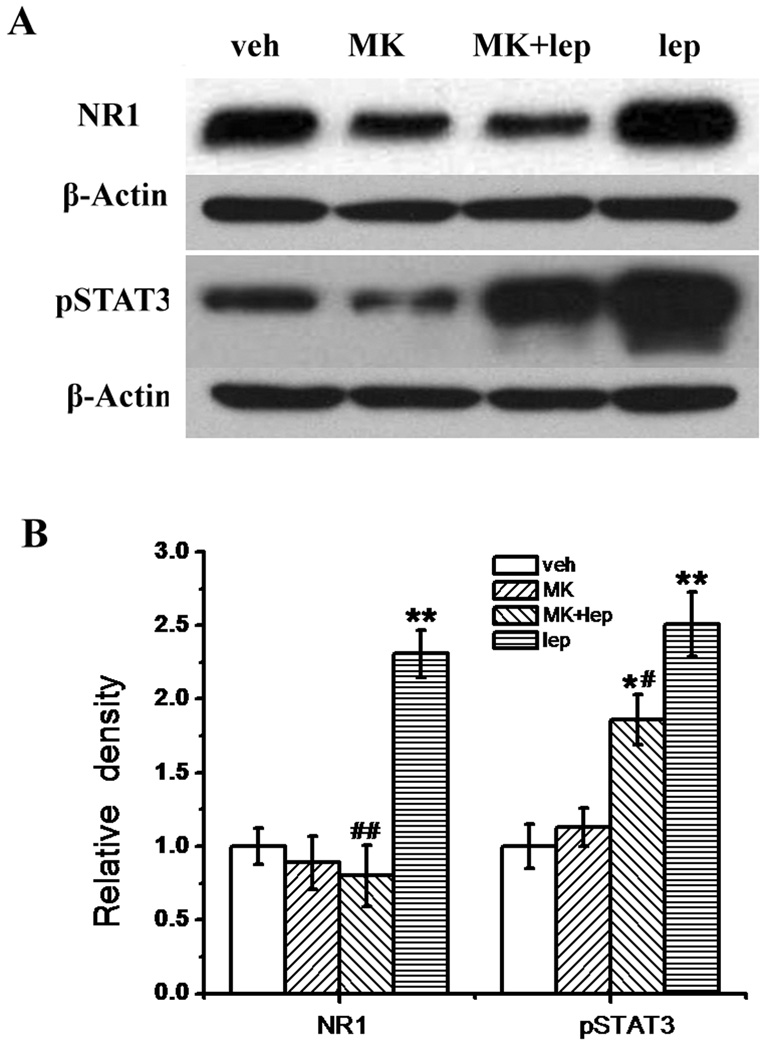

To further confirm the relationship between spinal leptin signaling and NMDAR, spinal cord samples taken on day 14 from four groups of rats (vehicle; 50 µg leptin; 50 µg leptin plus 10 nmol MK-801; 10 nmol MK-801) in the above behavioral experiment were used to examine the expression of the NMDAR subunit NR1 and pSTAT3. Compared with the vehicle group, the leptin treatment upregulated the expression of NR1 and pSTAT3 within the spinal cord dorsal horn, as revealed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 6) and Western blot (Fig. 7A, 7B; n = 5; P < 0.01). Co-administration of MK-801 with leptin effectively prevented the leptin-induced upregulation of both NR1 and pSTAT3 (Fig. 6; Fig. 7A, 7B, n = 5, P < 0.05 – 0.01). MK-801 alone did not change the baseline expression of NR1 and pSTAT3 (Fig. 6; Fig. 7A, 7B, n = 5, P < 0.05 – 0.01). Of note, no additional groups of rats were used to obtain tissue samples before day 14 because no differences in the behavioral testing were observed between the treatment and control group on day 9 and day 11 (data not shown).

Fig. 6. Leptin-induced spinal NR1 and pSTAT3 upregulation.

Intrathecal leptin (50 µg) in naïve rats, given once daily for 14 days, upregulated the expression of the NR1 subunit and pSTAT3 within the spinal cord dorsal horn. The cellular changes were attenuated by coadministration of leptin with MK-801 (10 nmol) for 14 days. MK-801 alone did not change the baseline expression of NR1 and pSTAT3. For each panel, the upper right corner represents the dorsal part of the spinal cord. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Fig. 7. Prevention by MK-801 of leptin-induced spinal NR1 and pSTAT3 upregulation.

A, Western blot data showing the upregulation of NR1 and pSTAT3 in the spinal cord dorsal horn of rats receiving a 14-day intrathecal leptin (50 µg) treatment. B, Statistical data showing that MK-801 (10 nmol) prevented the upregulation of NR1 and pSTAT3 when coadministered with leptin for 14 days and MK-801 alone did not change the baseline expression of NR1 and pSTAT3. Data are shown as mean±S.E. *P < 0.05, P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 as compared with vehicle; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 as compared with leptin. Veh, vehicle; lep, leptin; MK, MK-801; β-actin, loading control.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that 1) leptin enhanced spinal NMDA-induced currents in SG neurons, 2) this leptin effect was mediated through leptin receptors and the related intracellular JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, 3) a single dose of leptin enhanced NMDA-elicited spontaneous biting, scratching and licking behaviors indicative of spinal neuronal excitation, 4) repeated exposure to leptin induced NMDAR-mediated thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia similar to that seen following peripheral nerve injury, and 5) leptin upregulated the expression of NR1 and pSTAT3 within the spinal cord dorsal horn, which was also mediated through NMDAR. These data reveal a relationship between the spinal leptin effect and NMDAR-mediated neuronal excitation and nociceptive behavior, supporting an important mechanism of adipocytokine in nociception [31,35].

4.1 Methodological consideration

It has long been recognized that the spinal substantia gelatinosa (SG, Lamina II) is a key element in the nociceptive processing as this spinal region receives the input from both Aδ and C primary afferent fibres [26,30,63,67]. Previous in vitro and in vivo studies have suggested that characteristic discharge patterns, including the tonic-firing, delayed-firing, phasic-bursting, initial-bursting and single-spiking patterns, of SG neurons might be linked to the functional properties of SG neurons [17,18,47,48,63,67]. While the exact correlations are yet to be determined between neuronal firing patterns and neuronal functions (e.g., excitatory versus inhibitory neurons; Aδ versus C afferent input; wide-dynamic-range versus nociceptive-specific neurons) [17, 18, 34, 49], it has been shown that most SG neurons (85%) were excitatory and glutamatergic neurons and that a vast majority of SG neurons with a tonic-firing, initial or phasic-firing pattern were excitatory interneurons [48]. In contrast, SG neurons with a delayed-firing pattern could be both excitatory and inhibitory interneurons [48]. While our data showed that most recorded SG neurons exhibiting the leptin-enhancement of NMDA-induced current had a tonic-firing pattern and neurons with a delayed-firing pattern were least responsive to the leptin effect (Table 1), future studies should determine whether leptin enhances NMDA-induced currents mainly in excitatory SG neurons.

We would like to point out that neuronal activity recorded in our experimental preparation was evoked by exogenous NMDA. It is unclear whether leptin has a similar effect on synaptic activity involving NMDA receptors, although the behavioral data regarding the facilitation by leptin of NMDA receptor-mediated spinal excitation supports a functional role of the spinal leptin effect on neuronal activity. Our next step is to investigate whether leptin would affect synaptic activity involving NMDA receptors by stimulating dorsal roots in spinal cord slices.

4.2 Relationship between leptin and NMDAR at the spinal level

Leptin is a 16-kDa amino acid polypeptide hormone encoded by the obese gene [68], which is well known for its role in regulating food intake and body weight [1,11,12,50,68]. Leptin is produced mainly, but not exclusively, by white adipose tissue [22,41] and transported across the blood brain barrier to the central nervous system via receptor-mediated transcytosis [2,44]. However, the leptin mRNA expression and protein immunoreactivity have also been detected across various brain regions, including the hypothalamus, hippocampus, cortex, cerebellum, and spinal cord [31,39,56], suggesting that leptin could be produced within the central nervous system as well [2,22,31,43].

In this study, we demonstrated a relationship between the spinal leptin effect and NMDAR-mediated function both at the cellular and system level. First, leptin enhanced NMDA-induced current in a dose-dependent manner in SG neurons, which appears to be peaked at the concentration of 100 nM leptin under our experimental condition. Second, this spinal leptin effect was mediated by leptin receptors because leptin failed to enhance NMDA-induced current in mice deficient in leptin receptors. Third, leptin enhanced spinal NMDA-induced spontaneous biting, scratching and licking behaviors, a behavioral indication of spinal excitation. Fourth, spinal administration of leptin elicited nociceptive behavior (thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia) similar to that seen in rats with peripheral nerve injury [31], which was blocked by the NMDAR antagonist MK-801. Of note, in the present study we showed that repeated leptin exposure induced nociceptive behavior in naïve rats when examined on day 14, whereas in our previous study leptin induced similar nociceptive behavior on day 7 [31]. This different time course of nociceptive behavior might be experimental variations due to using different batches of rats. Fifth, the NMDAR antagonist MK-801 prevented the upregulation by leptin of spinal NMDAR (NR1 subunit) expression.

Our findings are consistent with an increasing number of reports showing a functional relationship between leptin and NMDAR [16,21,29,51,57,61]. It should be noted that in this study our investigation was focused on the effect of leptin on the NMDAR at the spinal level. Future studies may expand these findings to examine the relationship between leptin and other NMDAR subunits (e.g., NR2A-2D) as well as AMPA receptors because NR2 subunits and AMPA receptors are also expressed in SG neurons and play an important role in the mechanisms of neuropathic pain [15,32,36,38,42,45,55].

4.3 Relationship between leptin receptor signaling and the leptin-NMDAR interaction

To date, at least six leptin receptor isoforms have been described [28,58]. Leptin receptors are expressed across widespread brain regions including the hypothalamus, thalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala as well as in the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglion [6,12,31,33,62]. This distribution pattern of leptin receptors is consistent with the leptin’s extensive neuronal functions [1,13,20,31,41,54]. At the cellular level, leptin binds to its receptors such as Ob-Rb, a member of the class I cytokine receptor superfamily, which results in JAK2-mediated phosphorylation in the cytoplasmic tail of the receptor [40]. Activation of leptin receptors initiates various downstream signaling pathways including PI3K, MAPK and JAK2/STAT3 [3,41]. In this study, we showed that a) leptin failed to enhance NMDAR-mediated currents in SG neurons in db/db mice, b) the JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor AG 490 attenuated leptin-induced enhancement of NMDA currents in SG neurons, c) the PI3K inhibitor LY-294,002 and the MAPK inhibitor PD 98,059 had no effect on the spinal leptin action, although the same concentration of LY-294,002 and PD 98,059 prevented leptin-mediated facilitation of NMDA-induced Ca2+ rises in hippocampal slices [51], and d) intrathecal administration of leptin upregulated the expression of both NMDAR and pSTAT3, which was also attenuated by coadministration of leptin with the NMDAR antagonist MK-801. Together, the present data reveal a mechanistic link between the spinal leptin receptor signaling and NMDAR function via activation of the JAK/STAT pathway.

4.4 A functional role for the spinal leptin-NMDAR interaction in neuropathic pain

Several recent clinical observations indicate that the systemic leptin level is closely linked to spinal cord injury and pain. For example, patients with spinal cord injury, endometriosis, pelvic pain, chronic angina pectoris, or acute myocardial conditions have a higher plasma leptin level [9,24,25,53]. In preclinical studies using naïve animals without tissue injury, intraperitoneal leptin injection significantly lowered the hotplate withdrawal latency in mice [27]. Moreover, mice with the leptin receptor null mutation (db/db) displayed a decreased sensitivity to mechanical stimulation and decreased hindpaw activity during the second phase of a formalin test [65] and leptin replacement restored supraspinal cholinergic antinociception in leptin deficient (ob/ob) mice [60]. Two recent articles, including ours, report that leptin plays a significant role in the development of nociceptive behaviors in animals with peripheral nerve injury [31,35].

On the other hand, there is considerable evidence that activation of NMDAR contributes to the mechanism of pathological pain [7,8,45]. A large number of studies have shown that antagonizing the NMDAR reduces nociceptive behaviors induced by peripheral nerve injury [10,14,23,36,64]. The interaction between the spinal leptin effect and NMDAR function supports a critical role for leptin in the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain [31] and suggests a possible strategy of pharmacological interventions of neuropathic pain by blocking the effect of leptin and its intracellular signaling pathways.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by NIH grants P20DA26002, RO1DE18214, and RO1DE18538.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Reference

- 1.Ahima RS, Qi Y, Singhal NS, Jackson MB, Scherer PE. Brain adipocytokine action and metabolic regulation. Diabetes. 2006;55:S145–S154. doi: 10.2337/db06-s018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks WA. The many lives of leptin. Peptides. 2004;25:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjørbaek C, Kahn BB. Leptin signaling in the central nervous system and the periphery. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2004;59:305–331. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjorkman R, Hallman KM, Hedner J, Hedner T, Henning M. Acetaminophen blocks spinal hyperalgesia induced by NMDA and substance P. Pain. 1994;57:259–264. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H, Charlat O, Tartaglia LA, Woolf EA, Weng X, Ellis SJ, Lakey ND, Culpepper J, Moore KJ, Breitbart RE, Duyk GM, Tepper RI, Morgenstern JP. Evidence that the diabetes gene encodes the leptin receptor: identification of a mutation in the leptin receptor gene in db/db mice. Cell. 1996;84:491–495. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen HP, Fan J, Cui S. Detection and estrogen regulation of leptin receptor expression in rat dorsal root ganglion. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;126:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Mello R, Dickenson AH. Spinal cord mechanisms of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:8–16. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doubell TP, Mannion RJ, Woolf CJ. The dorsal horn: statedependent sensory processing, plasticity and the generation of pain. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of pain. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. pp. 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubey L, Zeng HS, Wang HJ, Liu RY. Potential role of adipocytokine leptin in acute coronary syndrome. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2008;16:124–128. doi: 10.1177/021849230801600209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubner R. Neuronal plasticity and pain following peripheral tissue inflammation or nerve injury. In: Bond M, Charlton E, Woolf CJ, editors. Proceedings of the 5th World Congress on pain. Pain research and clinical management; Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1991. pp. 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elmquist JK, Maratos-Flier E, Saper CB, Flier JS. Unraveling the central nervous system pathways underlying responses to leptin. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:445–450. doi: 10.1038/2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elmquist JK, Bjørbaek C, Ahima RS, Flier JS, Saper CB. Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395:535–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farr SA, Banks WA, Morley JE. Effects of leptin on memory processing. Peptides. 2006;27:1420–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher K, Coderre TJ, Hagen NA. Targeting N-methyl-daspartate receptor for chronic pain management: preclinical animal studies, recent clinical experience and future research directions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:358–373. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garry EM, Moss A, Rosie R. Specific involvement in neuropathic pain of AMPA receptors and adapter proteins for the GluR2 subunit. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:10–22. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerges NZ, Aleisa AM, Alkadhi KA. Impaired long-term potentiation in obese zucker rats: possible involvement of presynaptic mechanism. Neuroscience. 2003;120:535–539. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham BA, Brichta AM, Callister RJ. In vivo responses of mouse superficial dorsal horn neurones to both current injection and peripheral cutaneous stimulation. J Physiol. 2004;561:749–763. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grudt TJ, Perl ER. Correlations between neuronal morphology and electrophysiological features in the rodent superficial dorsal horn. J Physiol. 2002;540:189–207. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Härle P, Straub RH. Leptin is a link between adipose tissue and inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1069:454–462. doi: 10.1196/annals.1351.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvey J, Solovyova N, Irving A. Leptin and its role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Prog Lipid Res. 2006;45:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey J. Leptin: a diverse regulator of neuronal function. J Neurochem. 2007;100:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hewitt DJ. The use of NMDA-receptor antagonists in the treatment of chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2000;16:S73–S79. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200006001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang TS, Wang YH, Chen SY. The relation of serum leptin to body mass index and to serum cortisol in men with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:1582–1586. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.9173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jose VJ, Mariappan P, George PV, Selvakumar, Selvakumar D. Serum leptin levels in acute myocardial infarction. Indian Heart J. 2005;57:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumazawa T, Perl ER. Excitation of marginal and substantia gelatinosa neurons in the primate spinal cord: indications of their place in dorsal horn functional organization. J Comp Neurol. 1978;177:417–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.901770305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kutlu S, Canpolat S, Sandal S, Ozcan M, Sarsilmaz M, Kelestimur H. Effects of central and peripheral administration of leptin on pain threshold in rats and mice. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2003;24:193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee GH, Proenca R, Montez JM. Abnormal splicing of the leptin receptor in diabetic mice. Nature. 1996;379:632–635. doi: 10.1038/379632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li XL, Aou S, Oomura Y, Hori N, Fukunaga K, Hori T. Impairment of long-term potentiation and spatial memory in leptin receptor-deficient rodents. Neuroscience. 2002;113:607–615. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Light AR, Perl ER. Spinal termination of functionally identified primary afferent neurons with slowly conducting myelinated fibers. J Comp Neurol. 1979;186:133–150. doi: 10.1002/cne.901860203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim G, Wang S, Zhang Y, Tian Y, Mao J. Spinal leptin contributes to the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain in rodents. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:295–304. doi: 10.1172/JCI36785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim J, Lim G, Sung B, Wang S, Mao J. Intrathecal midazolam regulates spinal AMPA receptor expression and function after nerve injury in rats. Brain Res. 2006;1123:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin J, Barb CR, Matteri RL, Kraeling RR, Chen X, Meinersmann RJ, Rampacek GB. Long form leptin receptor mRNA expression in the brain, pituitary, and other tissues in the pigq. Domest Anim. Endocrinol. 2000;19:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0739-7240(00)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez-Garcia JA, King AE. Membrane properties of physiologically classified rat dorsal horn neurons in vitro: correlation with cutaneous sensory afferent input. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:998–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maeda T, Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Ikuta T, Ozaki M, Kishioka S. Leptin derived from adipocytes in injured peripheral nerves facilitates development of neuropathic pain via macrophage stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13076–13081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903524106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao J, Price DD, Hayes RL, Lu J, Mayer DJ. Differential roles of NMDA and non-NMDA receptor activation in induction and maintenance of thermal hyperalgesia in rats with painful peripheral neuropathy. Brain Res. 1992;598:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90193-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mao J, Sung B, Ji RR, Lim G. Chronic morphine induces downregulation of spinal glutamate transporters: implications in morphine tolerance and abnormal pain sensitivity. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8312–8323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08312.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Momiyama A. Distinct synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors identified in dorsal horn neurones of the adult rat spinal cord. J Physiol. 2000;523:621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morash B, Li A, Murphy P, Wilkinson M, Ur E. Leptin gene expression in the brain and pituitary gland. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5995–5998. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Munzberg H, Myers MG., Jr Molecular and anatomical determinants of central leptin resistance. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:566–570. doi: 10.1038/nn1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myers MG., Jr Leptin receptor signaling and the regulation of mammalian physiology. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2004;59:287–304. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narita M, Miyoshi K, Narita M, Suzuki T. Changes in function of NMDA receptor NR2B subunit in spinal cord of rats with neuropathy following chronic ethanol consumption. Life Sci. 2007;80:852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmiter RD. Is dopamine a physiologically relevant mediator of feeding behavior? Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan W, Kastin A. Adipokines and the blood-brain barrier. Peptides. 2007;28:1317–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petrenko AB, Yamakura T, Baba H, Shimoji K. The Role of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) Receptors in Pain: A Review. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1108–1116. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000081061.12235.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roh D, Seo H, Yoon S, Song S, Han H, Beitz AJ, Lee J. Activation of spinal α-2 adrenoceptors, but not μ-opioid receptors, reduces the intrathecal N-Methyl-d-Aspartate-induced increase in spinal NR1 subunit phosphorylation and nociceptive behaviors in the rat. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:622–629. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c8afc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruscheweyh R, Sandkühler J. Lamina-specific membrane and discharge properties of rat spinal dorsal horn neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 2002;541:231–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santos SFA, Rebelo S, Derkach VA, Safronov BV. Excitatory interneurons dominate sensory processing in the spinal substantia gelatinosa of rat. J Physiol. 2007;581:241–254. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoffnegger D, Heinke B, Sommer C, Sandkühler J. Physiological properties of spinal lamina II GABAergic neurons in mice following peripheral nerve injury. J Physiol. 2006;577:869–878. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Jr, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000;404:661–671. doi: 10.1038/35007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shanley LJ, Irving AJ, Harvey J. Leptin enhances NMDA receptor function and modulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-j0001.2001. RC186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tal M, Bennett GJ. Extra-territorial pain in rats with a peripheral mononeuropathy: mechano-hyperalgesia and mechano-allodynia in the territory of an uninjured nerve. Pain. 1994;57:275–282. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taneli F, Yegane S, Ulman C, Tikiz H, Bilge AR, Ari Z, Uyanik BS. Increased serum leptin concentrations in patients with chronic stable angina pectoris and ST-elevated myocardial infarction. Angiology. 2006;57:267–272. doi: 10.1177/000331970605700302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang BL. Leptin as a neuroprotective agent. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tolle TR, Berthele A, Zieglgansberger W, Seeburg PH, Wisden W. The differential expression of 16 NMDA and non-NMDA receptor subunits in the rat spinal cord and in periaqueductal gray. J Neurosci. 1993;13:5009–5028. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05009.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ur E, Wilkinson DA, Moras BA, Wilkinson M. Leptin immunoreactivity is localized to neurons in rat brain. Neuroendocrinology. 2002;75:264–272. doi: 10.1159/000054718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker D, Long H, Williams S, Richard D. Long-lasting effects of elevated neonatal leptin on rat hippocampal function, synaptic proteins and NMDA receptor subunits. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:816–828. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang J, Liu R, Hawkins M, Barzilai N. A nutrient-sensing pathway regulates leptin gene expression in muscle and fat. Nature. 1998;393:684–688. doi: 10.1038/31474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang S, Lim G, Zeng Q, Sung B, Yang L, Mao J. Central glucocorticoid receptors modulate the expression and function of spinal NMDA receptors after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2005;25:488–495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4127-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang W, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Leptin Replacement Restores Supraspinal Cholinergic Antinociception in Leptin-Deficient Obese Mice. J Pain. 2009;10:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wayner MJ, Armstrong DL, Phelix CF, Oomura Y. Orexin-A (Hypocretin-1) and leptin enhance LTP in the dentate gyrus of rats in vivo. Peptides. 2004;25:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilkinson M, Brown R, Imran SA, Ur E. Adipokine gene expression in brain and pituitary gland. Neuroendocrinology. 2007;86:191–209. doi: 10.1159/000108635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Willis WD, Coggeshall RE. Sensory Mechanisms of the Spinal Cord. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Woolf CJ, Mannion RJ. Neuropathic pain: aetiology, symptoms, mechanisms, and management. Lancet. 1999;353:1959–1964. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wright DE, Johnson MS, Arnett MG, Smittkamp SE, Ryals JM. Selective changes in nocifensive behavior despite normal cutaneous axon innervation in leptin receptor-null mutant (db/db) mice. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2007;12:250–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2007.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamamoto T, Yaksh TL., q Spinal pharmacology of thermal hyperalgesia induced by constriction injury of sciatic nerve. Excitatory amino acid antagonists. Pain. 1992;49:121–128. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90198-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoshimura M, Jessell TM. Primary afferent-evoked synaptic responses and slow potential generation in rat substantia gelatinosa neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1989;62:96–108. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372:425–432. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]