Abstract

Macrocyclic chelators have been extensively used for complexation of metal ions. A widely used chelator, DOTA, has been explored as a molecular platform to assemble multiple bioactive peptides in this paper. The multivalent DOTA-peptide bioconjugates demonstrate promising tumor targeting ability.

Keywords: Molecular Imaging, PET, Integrin, Multivalency, RGD peptide

Multivalent biomolecules such as peptides have been explored as a useful strategy to construct molecular imaging probes and drug delivery carriers. It is generally accepted that multivalency has advantages over monovalency for improving binding affinities and even activity.1 Compared to the monomeric peptides, many multivalent peptides could show improved binding affinities in vitro and tumor targeting and imaging ability in vivo.2 Multivalent biomolecules thus have been constructed by using a variety of molecular platforms including small molecules such as amino acids (glutamine) and a fluorescent dye,2,3 multiple antigen peptides (MAP),4 proteins,5 dendrimers and polymers,6 and nanoparticles.7

Macrocyclic chelators are generally used for complexation of metal ions, and they have been widely used in molecular imaging applications when they complex with radioactive, paramagnetic or fluorescent metal ions.8 Various macrocyclic chelators such as polyamino polycarboxylate-type macrocycles have been successfully and extensively used as bifunctional chelators (BFCA) for labeling biomolecules.9 Recently, a polyamino polycarboxylate-type chelator, CB-TE2A, was explored as a scaffold to build a dimeric peptide while simultaneously forming a stable complex with the positron emission tomography (PET) radiometal, 64Cu (t1/2 = 12.7 h, Eβ+ max = 656 keV, 19%). The resulting divalent positron emission tomography (PET) probe exhibits excellent tumor imaging quality which highlights the advantages of this novel approach for designing multivalent probes using BFCA as a molecular scaffold.10 But CB-TE2A can only be used to construct divalent probes, and the availability of the chelator is limited and synthesis of the compound requires significant effort.

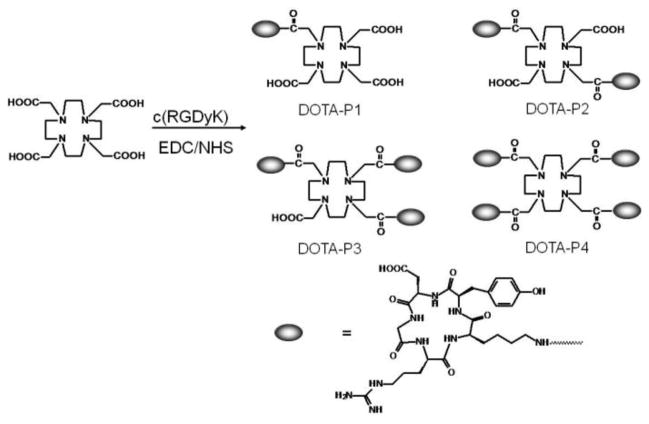

Herein, we present the use of a widely available macrocyclic chelator, 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA), for the assembly of multiple peptides in tumor targeting. DOTA is an excellent choice for attaching metal ions to peptides, antibodies, and many other biologically active molecules, because it forms stable complexes with a variety of metal ions [64Cu, 67/68Ga, 111In, 86/90Y, 177Lu, 166Ho, Gd(III), Eu(III), Tb(III), Yb(III), etc.] with high thermodynamic stability and kinetic inertness.8 Traditionally only one arm of DOTA is used for conjugation with one biomolecule. Considering that DOTA has four acetic acid side-arms, they could all be easily activated, functionalized and used for preparation of mono, di, tri, tetra-valent biomolecules. For the proof of concept, a small cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) peptide [c(RGDyK)] which is a well known ligand for tumor integrin receptors was selected for construction of multivalent molecules (Figure 1).6,11 The resulting bioconjugates were radiolabeled with 64Cu and their in vivo performance was then studied using microPET.

Figure 1.

The structure of multivalent DOTA-RGD peptides (monomer: DOTA-P1; dimer: DOTA-P2; trimer: DOTA-P3; Tetramer: DOTA-P4).

The synthesis of mono or multi-meric DOTA-RGD peptides (DOTA-P1, DOTA-P2, DOTA-P3, and DOTA-P4, Figure 1) was achieved through a simple one pot synthesis reaction which involves coupling of in situ prepared DOTA-OSSu esters with the ε-amino group of the lysine residue in the large excess of c(RGDyK) (Supporting Information). The desired multi-meric DOTA-RGD peptides could be easily separated and purified by an analytic HPLC, and the purity of target compounds was generally obtained with over 95% purity. But the yields for each peptide are quite different, which DOTA-P2 shows highest, DOTA-P1 and DOTA-P3 shows moderate and DOTA-P4 has very low yield. The retention time on the analytical HPLC for these bioconjugates was found to be 16.8, 21.2, 24.1 and 26.6 minutes (Table 1 and Supporting Information). The purified DOTA-RGD peptides were characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS). The measured molecular weights (MW) of the compounds were consistent with the expected MWs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Retention time, molecular weight and IC50 of multivalent DOTA-RGD peptides. (n/a, not applicable)

| Retention time (min) | MW Expected | MW Measured | IC50 (nM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOTA-P1 | 16.8 | 1006.49 | 1006.46 | 380 ± 190 |

| DOTA-P2 | 21.2 | 1607.69 | 1607.70 | 37.1 ± 7.8 |

| DOTA-P3 | 24.1 | 2209.08 | 2209.46 | 13.6 ± 1.4 |

| DOTA-P4 | 26.6 | 2810.38 | 2810.47 | n/a |

The relative binding affinities of DOTA-RGD peptides to cell surface integrin receptors were determined through a competitive binding assay with 125I-echistatin.11 All the DOTA-RGD peptides inhibited the binding of 125I-echistatin to integrin expressing U87MG cells in a concentration-dependent manner. The mean ± standard deviation IC50 values of DOTA-P1, DOTA-P2, and DOTA-P3 were 380 ± 190 nM, 37.1 ± 7.8 nM, and 13.6 ± 1.4 nM, respectively (n = 3). The biological evaluation of DOTA-P4 was not performed because of its low yield and potential low in vivo stability when it is complexed with 64Cu.12 The receptor binding study clearly indicates that conjugation of multiple RGD peptides to the DOTA molecular platform can improve the binding affinity and achieve multivalency effects.

DOTA-P1, DOTA-P2 and DOTA-P3 conjugates were then successfully radiolabeled with 64Cu by a 1 hour incubation at 50 °C. The purification of radiolabeling solution using RP-HPLC afforded 64Cu-DOTA-peptides with >95% radiochemical purity, and modest specific activities of 0.28–0.33 Ci/μmol (10.3–12.3 MBq/nmol) 64Cu-DOTA-peptides were obtained as estimated by analytical HPLC (decay corrected). In vitro serum stability of the radiolabeled peptides was also tested by incubation of the 64Cu-DOTA-peptide with mouse serum for 1 h at 37 °C. All the radiolabeled peptides were stable and over 90% of peptides were still intact after 1 h incubation.

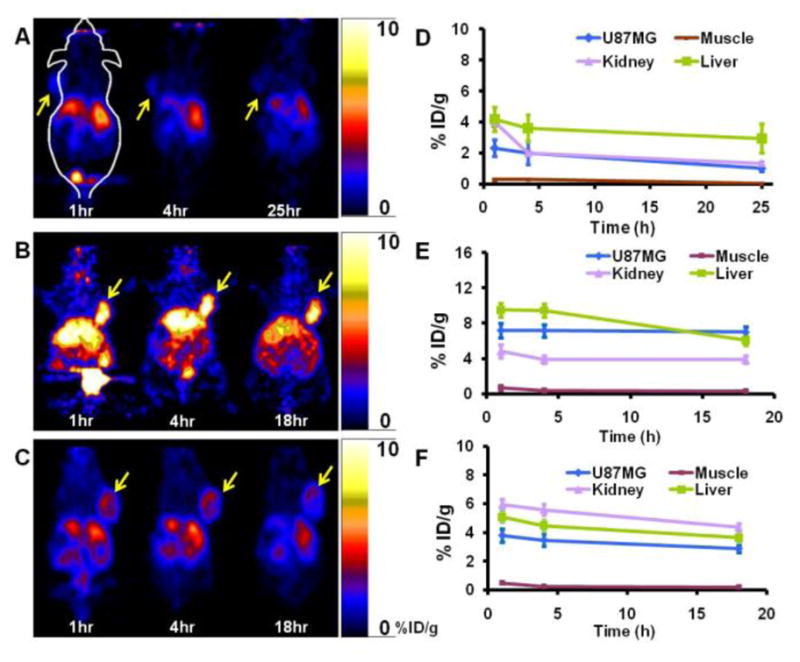

Static microPET scans were performed on integrin receptors positive U87MG tumor-bearing mice and the representative decay-corrected coronal images at different time points after tail vein injection of 64Cu-DOTA-P1, 64Cu-DOTA-P2, or 64Cu-DOTA-P3 are shown in Figure 2 (A, B and C; n =3 for each group), from which the U87MG tumors were clearly visualized with good tumor-to-background contrasts for all the probes. Interestingly, under the same scale it can be easily seen that the tumor uptake of these three radiocomplexes ranks as 64Cu-DOTA-P2 > 64Cu-DOTA-P3 > 64Cu-DOTA-P1. This result proves the advantage of multimerization of RGD peptide for in vivo tumor targeting. It is also consistence with previous reports.2,10 The microPET quantification analysis of tumors and other organs was obtained from the region of interest (ROI) analysis and the results at these time points are shown in Figure 2D, E and F. 64Cu-labeled dimeric RGD peptide (64Cu-DOTA-P2) indeed displayed significant higher tumor uptake than that of monomer and trimer, while trimer showed significant higher tumor uptake than that of monomer (P < 0.05). At 1 h post-injection (p.i.), the tumor uptake was 2.32 ± 0.55, 7.20 ± 0.82, and 3.80 ± 0.46 %ID/g for 64Cu-DOTA-P1, 64Cu-DOTA-P2, 64Cu-DOTA-P3, respectively. Furthermore, it was found multimerization caused elevated kidney accumulation, both dimer and trimer showed relatively higher kidney uptakes than that of monomer (at 1 h p.i., 4.84 ± 0.72 and 5.96 ± 0.36 vs. 4.00 ± 0.32 %ID/g), which is also in consistence with the study of the other multimeric RGD peptides.2 Of note, the liver uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-P2 was also significantly higher than of 64Cu-DOTA-P1 and 64Cu-DOTA-P3.

Figure 2.

A, B and C: Representative coronal microPET images of the U87MG tumor-bearing mice at different time points (1, 4, 18 or 25 h) post-injection of 64Cu-DOTA-P1, 64Cu-DOTA-P2, and 64Cu-DOTA-P3, respectively (arrows indicate tumors). D, E, and F: MicroPET quantification results, expressed as percentage of injected dose per gram (%ID/g), in different organs and tumor of subcutaneous U87MG glioblastoma xenograft model after intravenous injection of 64Cu-DOTA-P1, 64Cu-DOTA-P2, and 64Cu-DOTA-P3, respectively.

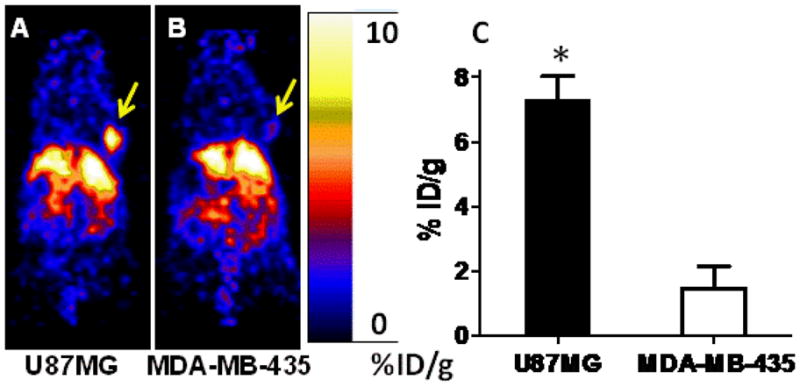

In order to further demonstrate the in vivo integrin targeting specificity of the multivalent probe, microPET imaging of 64Cu-DOTA-P2 was performed in MDA-MB-435 subcutaneous tumor model, which expresses much lower integrin receptors than that of U87MG.11 64Cu-DOTA-P2 displayed significant lower uptake in MDA-MB-435 tumor than in U87MG at 2 h p.i. (7.27 ± 0.76 vs. 1.47 ± 0.67, P < 0.05), suggesting the specificity of the probe (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Coronal microPET images of mice bearing U87MG (A) and MDA-MB-435 (B) tumors at 2 h after injection of 64Cu-DOTA-P2 (arrows indicate tumors). Quantification of microPET images was performed and shown in (C). (*p<0.05)

Here we demonstrate a simple strategy for developing multimeric biomolecules. Compared to many other molecular platforms, the metal chelator, DOTA, is cheap and can be easily modified with up to four biomolecules. Meanwhile, the in vivo performance of the resulting bioconjugates could be easily studied when DOTA is labeled with a radiocopper such as 64Cu. The 64Cu or other copper radioisotope labeled multimeric DOTA-bioconjugates could potentially find broad applications in tumor imaging and therapy.8 It also should be noted that for RGD dimer system, it is possible to form isomeric constructs (cis or trans). Further research on separation and characterization of these two isomers and studying their tumor imaging properties is important for understanding their structure-activity relationship. Moreover, DOTA-RGD bioconjuagtes could have very different copper coordination chemistry depending on the number of RGD ligands. More studies such as crystallography could be helpful to reveal the coordination number and fashion of multimeric probes. Finally, it is interesting that RGD dimer shows better in vivo properties than that of trimer. The in vivo performance of a probe depends on many factors including charge, size, hydrophilicity, stability of the label and more. The overall effects of these parameters may contribute to the excellent in vivo imaging properties of the dimeric RGD probe.

In conclusion, multivalent RGD peptides could be assembled using a macrocyclic chelator, DOTA, as a molecular scaffold. The four arms of DOTA provide an opportunity to prepare monomeric, dimeric, trimeric and tetrameric peptides by a one pot chemical synthesis. The resulting multimeric peptides show good tumor imaging quality. Especially, it was found that the radiolabeled multimeric DOTA-RGD peptides (64Cu-DOTA-P2 and 64Cu-DOTA-P3) displayed higher tumor uptakes than that of monomeric peptide. Taken together, the macrocyclic chelator DOTA is a promising molecular scaffold for construction of muletimeric biomolecules, and the the RGD multimeric peptides reported here are promising tumor targeting agents for clinical translation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant R01 CA119053 (to Z.C.) and a China Scholarship Council fellowship (to X.Z.).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.(a) Liu S. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:2199. doi: 10.1021/bc900167c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu S. Mol Pharm. 2006;3:472. doi: 10.1021/mp060049x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tweedle MF. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2006;1:2. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Vadas O, Rose K. J Pept Sci. 2007;13:581. doi: 10.1002/psc.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Handl HL, Vagner J, Han H, Mash E, Hruby VJ, Gillies RJ. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2004;8:565. doi: 10.1517/14728222.8.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Cheng Z, Wu Y, Xiong Z, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:1433. doi: 10.1021/bc0501698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li ZB, Cai W, Cao Q, Chen K, Wu Z, He L, Chen X. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1162. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.039859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wu Y, Zhang X, Xiong Z, Cheng Z, Fisher DR, Liu S, Gambhir SS, Chen X. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Garanger E, Boturyn D, Coll JL, Favrot MC, Dumy P. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;21:1958. doi: 10.1039/b517706e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Ye Y, Bloch S, Xu B, Achilefu S. J Med Chem. 2006;49:2268. doi: 10.1021/jm050947h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bapst JP, Froidevaux S, Calame M, Tanner H, Eberle AN. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2007;27:383. doi: 10.1080/10799890701723528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ye Y, Bloch S, Achilefu S. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7740. doi: 10.1021/ja049441z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wrighton NC, Balasubramanian P, Barbone FP, Kashyap AK, Farrell FX, Jolliffe LK, Barrett RW, Dower WJ. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:1261. doi: 10.1038/nbt1197-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Lusvarghi S, Kim JM, Creeger Y, Armitage BA. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:1815. doi: 10.1039/b820013k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Falciani C, Fabbrini M, Pini A, Lozzi L, Lelli B, Pileri S, Brunetti J, Bindi S, Scali S, Bracci L. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2441. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Kimura RH, Jones DS, Jiang L, Miao Z, Cheng Z, Cochran JR. Plos One. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016112. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoppmann S, Miao Z, Liu S, Liu H, Bao A, Cheng Z. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1021/bc100432h. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Dijkgraaf I, Rijnders AY, Soede A, Dechesne AC, van Esse GW, Brouwer AJ, Corstens FH, Boerman OC, Rijkers DT, Liskamp RM. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:935. doi: 10.1039/b615940k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boswell CA, Eck PK, Regino CA, Bernardo M, Wong KJ, Milenic DE, Choyke PL, Brechbiel MW. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:527. doi: 10.1021/mp800022a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu Z, Deshazer H, Rice AJ, Chen K, Zhou C, Kallenbach NR. J Med Chem. 2006;49:3436. doi: 10.1021/jm0601452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Gao J, Chen K, Miao Z, Ren G, He X, Chen X, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. Biomaterials. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.053. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Montet X, Funovics M, Montet-Abou K, Weissleder R, Josephson L. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6087. doi: 10.1021/jm060515m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hong S, Leroueil PR, Majoros IJ, Orr BG, Baker JR, Jr, Banaszak MM. Chem Biol. 2007;14:107. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Wadas TJ, Wong EH, Weisman GR, Anderson CJ. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2858. doi: 10.1021/cr900325h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu S. Chem Soc Rev. 2004;33:445. doi: 10.1039/b309961j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Caravan P, Ellison JJ, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2293. doi: 10.1021/cr980440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bornhop DJ, Contag CH, Caravan P, Ellison JJ, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2293. doi: 10.1021/cr980440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu S. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1347. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu W, Hao G, Long MA, Anthony T, Hsieh JT, Sun X. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;121:7482. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Miao Z, Ren G, Liu H, Jiang L, Kimura RH, Cochran JR, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:2342. doi: 10.1021/bc900361g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiang L, Kimura RH, Miao Z, Silverman AP, Ren G, Liu HG, Li P, Gambhir SS, Cochran JR, Cheng Z. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:251. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.069831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kimura RH, Cheng Z, Gambhir SS, Cochran JR. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2435. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xiong ZM, Cheng Z, Zhang XZ, Patel M, Wu JC, Gambhir SS, Chen X. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Sun X, Wuest M, Weisman GR, Wong EH, Reed DP, Bosewell CA, Motekaitis R, Martell AE, Welch MJ, Anderson CJ. J Med Chem. 2002;45:469. doi: 10.1021/jm0103817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bosewell CA, Sun X, Niu W, Weiseman GR, Wong EH, Rheingold AL, Anderson CJ. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1465. doi: 10.1021/jm030383m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.