Abstract

One pathological hallmark of HIV-1 infection is chronic activation of the immune system, driven, in part, by increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The host attempts to counterbalance this prolonged immune activation through compensatory mediators of immune suppression. We recently identified a gene encoding the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-32 in microarray studies of HIV-1 infection in lymphatic tissue (LT) and show here that increased expression of IL-32 in both gut and LT of HIV-1-infected individuals may have a heretofore unappreciated role as a mediator of immune suppression. We show that: (i) IL-32 expression is increased in T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and epithelial cells in vivo; (ii) IL-32 induces the expression of immunosuppressive molecules indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO) and immunoglobulin-like transcript 4 (ILT4) in immune cells in vitro; (iii) in vivo, IL-32-associated IDO/ILT4 expression in LT macrophages and gut epithelial cells decreases immune activation but also may impair host defenses, supporting productive viral replication, thereby accounting for the correlation between IL-32 levels and HIV-1 replication in LT. Thus, during HIV-1 infection, we propose that IL-32 moderates chronic immune activation to avert associated immunopathology but at the same time dampens the antiviral immune response and thus paradoxically supports HIV-1 replication and viral persistence.

Introduction

Chronic activation of the immune system is a pathological hallmark of HIV-1 infection (1) and now widely accepted as an important negative prognosticator of disease progression in infected individuals (2). This chronic immune activation is thought to be due to the persistent nature of HIV-1 replication and the host’s inability to clear the virus (3). As such, the immune response does not contract and fully return to a quiescent-like state, instead, remaining in a state of sustained interplay between mediators of immune activation and immune suppression, which ultimately determines the magnitude, pace, and duration of an immune response to the invading pathogen (4). In HIV-1 infection, this “indelicate” balance between mediators of immune activation and immune suppression is skewed in a way that supports viral persistence, CD4+ T cell depletion, and other pathologies that result in disease progression (5–7).

Immune activation during HIV-1 infection is the result of a robust host response in lymphatic tissue (LT)3 (6), the primary anatomical site of viral replication, CD4+ T cell depletion, and pathology. This response is characterized by the upregulation of a vast array of genes controlling immune activation and antiviral molecules. While ongoing immune activation is one important feature throughout HIV-1 infection in LT, there is a compensatory upregulation in expression of genes promoting immune suppression during early HIV-1 infection, likely serving as a counterbalance to moderate the immunopathological consequences of sustained immune activation (6). Maintaining this equilibrium between immune activation and immune suppression is essential as imbalances can benefit HIV-1 replication—“too much” immune activation provides permissive target cells for the virus while “too much” immune suppression can dampen innate and cell-mediated immune responses needed to contain the virus.

We have examined the complex relationship between immune activation and suppression during HIV-1 infection by transcriptionally profiling the global host response to HIV-1 infection in LT (6, 7). Using this experimental approach, we have identified global, stage-specific transcriptional signatures during HIV-1 infection (6), transcriptional correlates of viral load (7), and particular genes that potentially provide tantalizing clues to factors and mechanisms that may be critically affecting HIV-1 replication and the host response in LT.

One such gene, the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-32, was originally identified in 1992 as an unknown transcript whose expression increased in activated NK and T cells (8). IL-32 is a multi-isoform cytokine which has received growing attention recently as an important component in numerous autoimmune and inflammatory disorders (9). Thus, when we identified IL-32 in our microarray analysis as a gene increased in expression in LT during HIV-1 infection (6), we investigated its potential functional role in this anatomical niche. In this report, we show that there is a significant increase in IL-32 expression in both lymph node and gut during HIV-1 infection, that this cytokine is a potent inducer of immunosuppressive molecules indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO) and immunoglobulin-like transcript 4 (ILT4), that IL-32 expression is associated with a dampening of the antiviral immune response by reducing cell-mediated cytotoxicity, potentially accounting for the correlation between increased IL-32 levels and higher HIV-1 replication in vivo. We thus propose that the nominally pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-32 actually functions as a double-edged sword during HIV-1 infection, suppressing both immune activation and the antiviral immune response, thereby supporting HIV-1 replication and viral persistence.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota. All patients provided written informed consent for the collection of samples and subsequent analysis.

Gut and lymph node biopsy specimens

Ileal, rectal, and inguinal lymph node biopsies from 4 HIV negative individuals and 26 untreated HIV-1-infected individuals at different clinical stages were obtained for this University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board-approved study. Viral load measurements were obtained the same day as biopsies. Each lymph node biopsy was immediately placed in fixative (4% neutral buffered paraformaldehyde or Streck's tissue fixative) before embedding in paraffin.

Immunohistochemistry/Immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence were performed as previously described (10) using a biotin-free detection system on 5-µm tissue sections mounted on glass slides. Tissues were deparaffinized and rehydrated in deionized water. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed using either a water-bath (95–98°C for 10–20 min) or high-pressure cooker (120°C for 30 sec) in one of the following buffers: DiVA Decloaker (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA), 10mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0, or 1mM EDTA, pH 8.0, followed by cooling to room temperature. Tissues sections were blocked with SNIPER Blocking Reagent (Biocare Medical) for 15 min at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% (v/v) H2O2 in methanol. Primary antibodies were diluted in Tris-NaCl-blocking buffer (0.1M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 0.15M NaCl; 0.05% Tween 20 with Dupont blocking buffer) and incubated overnight at 4°C. After the primary antibody incubation, sections were washed with PBS. Sections for immunofluorescence were then incubated with rabbit or mouse fluorophore-cojugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in 5% non-fat milk for 2 hr at room temperature. These sections were washed, nuclei counterstained blue with TOTO-3, and mounted using Aqua Poly/Mount (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA). Sections for immunohistochemistry were incubated with mouse or rabbit polymer system reagents conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, developed with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories), counterstained with Harris hematoxylin (Surgipath Medical, Richmond, IL), and mounted using Permount (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Stained sections were examined either by light microscopy or immunofluorescent confocal microscopy at ambient temperatures. Light micrographs were taken using an Olympus BX60 upright microscope with the following objectives: x10 (0.3 NA), x20 (0.5 NA), and x40 (0.75 NA); images were acquired using a Spot color mosaic camera (model 11.2) and Spot acquisition software (version 4.5.9; Diagnostic Instruments). Immunofluorescent micrographs were taken using an Olympus BX61 Fluoview confocal microscope with the following objectives: x20 (0.75 NA), x40 (0.75 NA), and x60 (1.42 NA); images were acquired using Olympus Fluoview software (version 1.7a). Isotype-matched IgG or IgM negative control antibodies in all instances yielded negative staining results (Supplemental Table I, which lists the primary antibodies and antigen retrieval methodologies).

To quantify levels of IL-32, IDO, or ILT4 expression in the gut and lymph node, 15 randomly stained images from each specimen were captured and positive cells enumerated using Photoshop (CS2, version 9.0; Adobe Systems) with plug-ins from Reindeer Graphics. Specifically, this program utilizes a threshold tool to set a gray level that discriminates positively-stained cells from background and marks the positive signal with a red overlay. The program then measures the area of the signal above the threshold, expressed as a % of the total area. Data were expressed as % tissue area positive for IL-32, IDO, or ILT4.

In situ hybridization of HIV-1 RNA+ cells

HIV-1 RNA was detected in cells in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues as previously described (11). Briefly, 5-µm sections were cut, adhered to silanized glass slides, and deparaffinized. Sections were first permeabilized by treating with HCl, digitonin and proteinase K, then acetylated, and finally hybridized to 35S-labelled HIV-1-specific riboprobes. After hybridization, the slides were washed in 5× standard saline citrate (SSC) / 10 mM DTT at 42°C, 2× SSC / 10 mM DTT / 50% formamide at 60°C, and a 2× riboprobe wash buffer (RWB) [0.1 M Tris-HC1, pH 7.5; 0.4 M NaCl; 50 mM EDTA] before digestion at 37°C with ribonuclease A (25 µg/ml) in 1× RWB. After washing in RWB, 2× SSC, and 0.1× SSC, sections were dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions containing 0.3 M ammonium acetate, dried, and then coated with nuclear track emulsion, exposed at 4°C, developed, and counterstained with Harris hematoxylin (Surgipath Medical). Light micrographs were taken using an Olympus BX60 upright microscope.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells treated with IL-32

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were isolated by density centrifugation using Ficoll/Hypaque (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (heat-inactivated) and 50 µg/ml gentamicin (Invitrogen) at 37°C / 5% CO2 . After overnight culture, 50 ng of IL-32γ (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or 5 µg of phytohemagglutinin was added to the culture and incubated for 24–48 hr. After incubation, cells were washed in PBS, spotted onto silanized glass slides, fixed using SAFEFIX II (Fisher Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI), dried, and stained for cellular markers using specific antibodies according to the above protocol. To quantify the fold-change in IDO or ILT4 production, 10 randomly stained images from each donor’s PBMCs (3 donors in total) in each experimental condition were captured using an Olympus BX60 upright microscope and positive cells enumerated by manually counting positively-stained cells in each image. The number of positively-stained cells was determined as a percentage of total cells and then compared to the control % in untreated samples, yielding a fold-change in protein expression (fold-change is set at 1 for control samples).

Statistical analysis

To test for the effect of stage on IL-32 expression, a mixed model was fit with the logarithm of IL-32 expression as the response variable, stage as a 4 level factor explanatory variable, and anatomical location as a dichotomous variable to distinguish lymph node from gut tissue (we included additive random effects for subjects to model the within-subject correlation). This model found significant differences between all HIV+ stages and the uninfected subjects (all p < 0.0001) as well as a significant difference between lymph node and gut; however, no significant differences were detected between the HIV+ stages. To test for an effect of day and dose in the in vitro experiments, a 2-way ANOVA was conducted using the logarithm of the expression levels. To test for associations between IL-32 and IDO or ILT4, linear models were fit where the log of IL-32 was the outcome and infection status plus the log of IDO or ILT4 were covariates in addition to the interaction between the 2 variables. This model found significant positive associations between IL-32 and IDO (p = 0.003), IL-32 and ILT4 (p < 0.0001), and IDO and ILT4 (p < 0.0001) among HIV-1-infetced individuals. Associations between continuous variables (IL-32 and immune activation markers, cell proliferation markers, cytotoxic mediators, or CD4+ T cell counts) were estimated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient and tests conducted using the usual t-test for a correlation. All calculations were conducted using the statistical software R version 2.10.1.

Microarray data accession number

All microarray results have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; accession number GSE16363).

Results

IL-32 expression is increased in lymph node and gut during HIV-1 infection

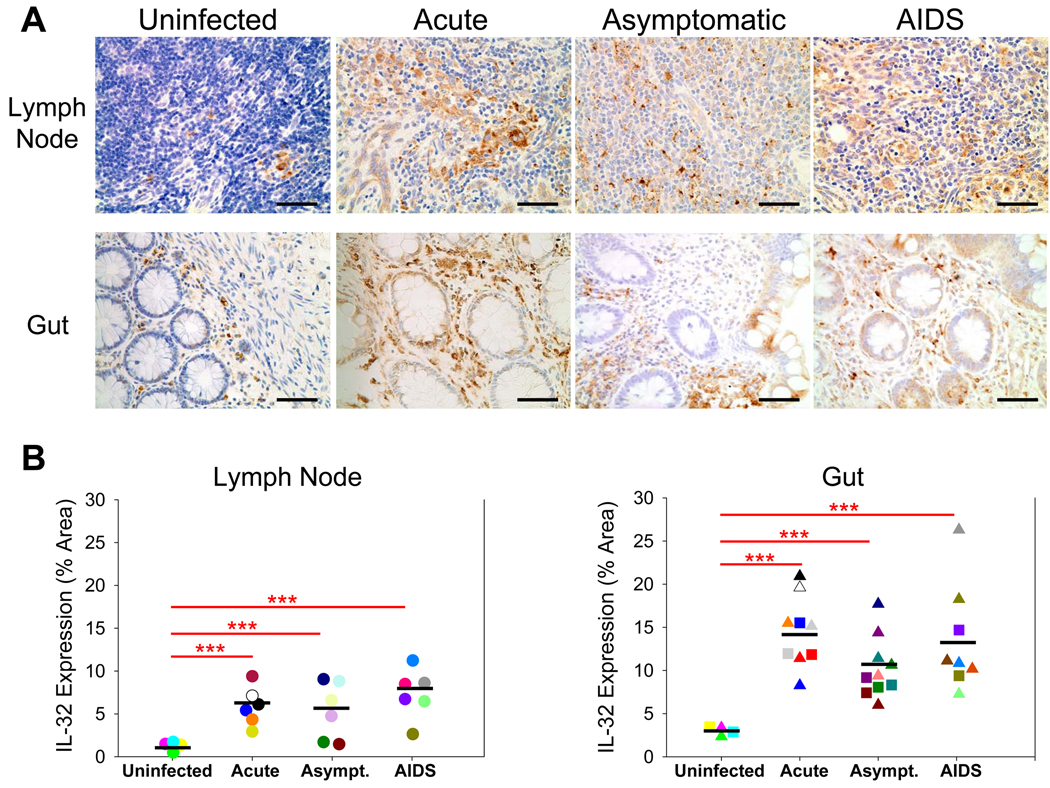

To examine changes in IL-32 expression during HIV-1 infection, we used antibodies recognizing IL-32 to stain gut (ileum and rectum) and lymph node (inguinal) biopsies from uninfected and HIV-1-infected individuals in each clinical stage of disease—acute (defined as individuals sampled within 4 months of documented seroconversion), asymptomatic (defined as individuals infected for at least 4 months with a CD4+ T cell count > 200 cells/µl), and AIDS (defined as infected individuals with a CD4+ T cell count < 200 cells/µl) (Table I). Compared to uninfected individuals, levels of IL-32 were significantly increased in both gut and LT during all stages of HIV-1 infection, with the highest IL-32 levels in the acute stage of disease for gut (4.8-fold increase) and AIDS stage of disease for lymph node (5.8-fold increase) (Figure 1).

Table I.

Clinical Characteristics of Study Subjects

| Patient | Disease Stage |

Gender | Age | Race | Peripheral Blood CD4+ T Cell Count (Cells/µl) |

Plasma HIV-1 RNA Levels (Copies/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP1476 | Uninfected | Female | 28 | Caucasian | 704 | Undetectable |

| DB1472 | Uninfected | Female | 52 | Caucasian | 837 | Undetectable |

| GG1425 | Uninfected | Male | 43 | Caucasian | 1351 | Undetectable |

| MS1452 | Uninfected | Male | 40 | Caucasian | 742 | Undetectable |

| MH1458 | Acute | Male | 51 | Caucasian | 400 | 439,000 |

| PH1329 | Acute | Male | 59 | Caucasian | 370 | 484,694 |

| PR1389 | Acute | Male | 32 | Caucasian | 824 | 32,173 |

| SQ1484 | Acute | Male | 49 | Caucasian | 301 | 23,721 |

| SR1469 | Acute | Male | 44 | Caucasian | 180 | > 100,000 |

| TH1449 | Acute | Male | 30 | Caucasian | 333 | > 100,000 |

| TS1435 | Acute | Male | 42 | Caucasian | 663 | > 100,000 |

| WB1391 | Acute | Male | 37 | African American |

234 | 24,718 |

| AE1419 | Asymptomatic | Male | 37 | Caucasian | 245 | 61,432 |

| CF1463 | Asymptomatic | Male | 23 | African American |

259 | 27,200 |

| DB1468 | Asymptomatic | Male | 30 | Caucasian | 875 | 2,150 |

| DS1335 | Asymptomatic | Male | 32 | Caucasian | 400 | 15,284 |

| EO1429 | Asymptomatic | Male | 27 | African American |

1,058 | 2,620 |

| JF1086 | Asymptomatic | Male | 30 | Caucasian | 512 | 20,562 |

| RC1293 | Asymptomatic | Male | 36 | Caucasian | 905 | 14,225 |

| TS1317 | Asymptomatic | Male | 31 | Caucasian | 399 | 120,469 |

| WU1459 | Asymptomatic | Male | 36 | Caucasian | 286 | > 100,000 |

| DD1446 | AIDS | Female | 45 | Caucasian | 200 | 150,500 |

| EL1474 | AIDS | Male | 40 | African American |

98 | 10,000 |

| GL1438 | AIDS | Male | 49 | Caucasian | 147 | 4,960 |

| MO1263 | AIDS | Male | 44 | Caucasian | 3 | > 100,000 |

| RB1413 | AIDS | Male | 50 | African American |

42 | 59,401 |

| TK1462 | AIDS | Male | 43 | Caucasian | 81 | 35,000 |

| VM1327 | AIDS | Female | 40 | African American |

112 | 12,046 |

| 95–6082 | AIDS | Female | 42 | Caucasian | 110 | > 100,000 |

| 93–1547 | AIDS | Male | 46 | Caucasian | 75 | > 100,000 |

Figure 1. IL-32 expression is significantly increased in both gut and lymph node during HIV-1 infection.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical images reveal increased IL-32 expression in the gut and inguinal lymph node during HIV-1 infection (IL-32-positive cells appear brown while cell nuclei appear blue). Original magnifications: X400; scale bars: 50 µm. (B) IL-32 expression was quantified in each biopsy and reported as % tissue area positive for IL-32. The results are shown with significance where applicable (***, p < 0.0001). Symbols: circles, triangles, and squares represent inguinal lymph node, ileal, and rectal biopsies, respectively, while the black bars denote the mean expression level of IL-32 in each stage of disease. Asymp. = Asymptomatic

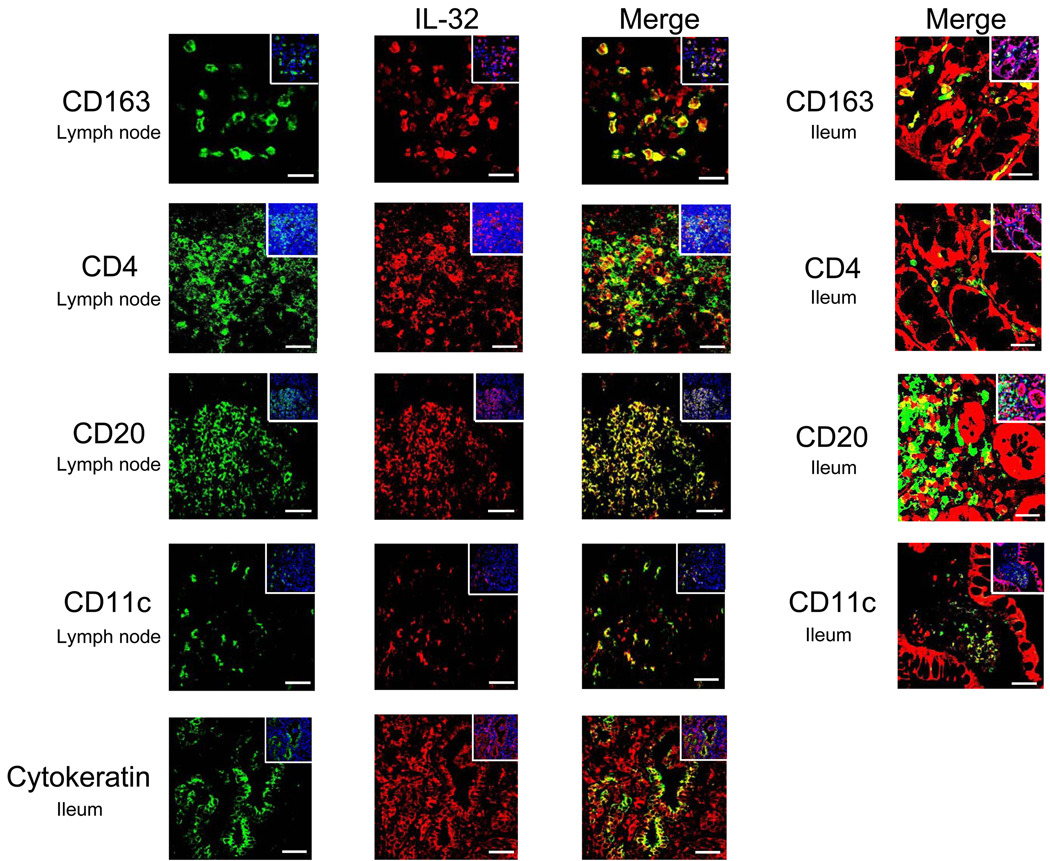

To determine the cellular source(s) of IL-32 within gut and LT, we utilized antibodies to CD4 or CD8 (T cells), CD163 (macrophages), CD20 (B cells), CD11c (dendritic cells), killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily C, member 1 (KLRC1, NK cells), and cytokeratin (epithelial cells) to co-localize IL-32 with the cell types producing this cytokine. As shown in representative images in Figure 2, IL-32 was expressed during HIV-1 infection in CD4+ T cells, B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells; minimal expression was detected in CD8+ T cells or NK cells (data not shown). Additionally, IL-32 was highly expressed in the mucosal epithelium of HIV-1-infected gut. Finally, the majority of IL-32+ cells were also expressing IL-18, a pro-inflammatory cytokine implicated in initiating IL-32 expression (12) (Supplemental Figure 1). Thus, IL-32 is significantly increased during HIV-1 infection and broadly expressed in many cell types in both gut and LT.

Figure 2. IL-32 is expressed in CD4+ T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and epithelial cells during HIV-1 infection.

Representative immunofluorescent images of IL-32 (red staining) and various cell surface markers (green staining) in the inguinal lymph node and gut from HIV-1-infected individuals, showing co-localization between IL-32 and CD163+ macrophages, CD4+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, CD11c+ dendritic cells, and cytokeratin+ epithelial cells. The insets show the total numbers of cells (cell nuclei appear blue) in each image. Original magnifications: X600; scale bars: 10 µm.

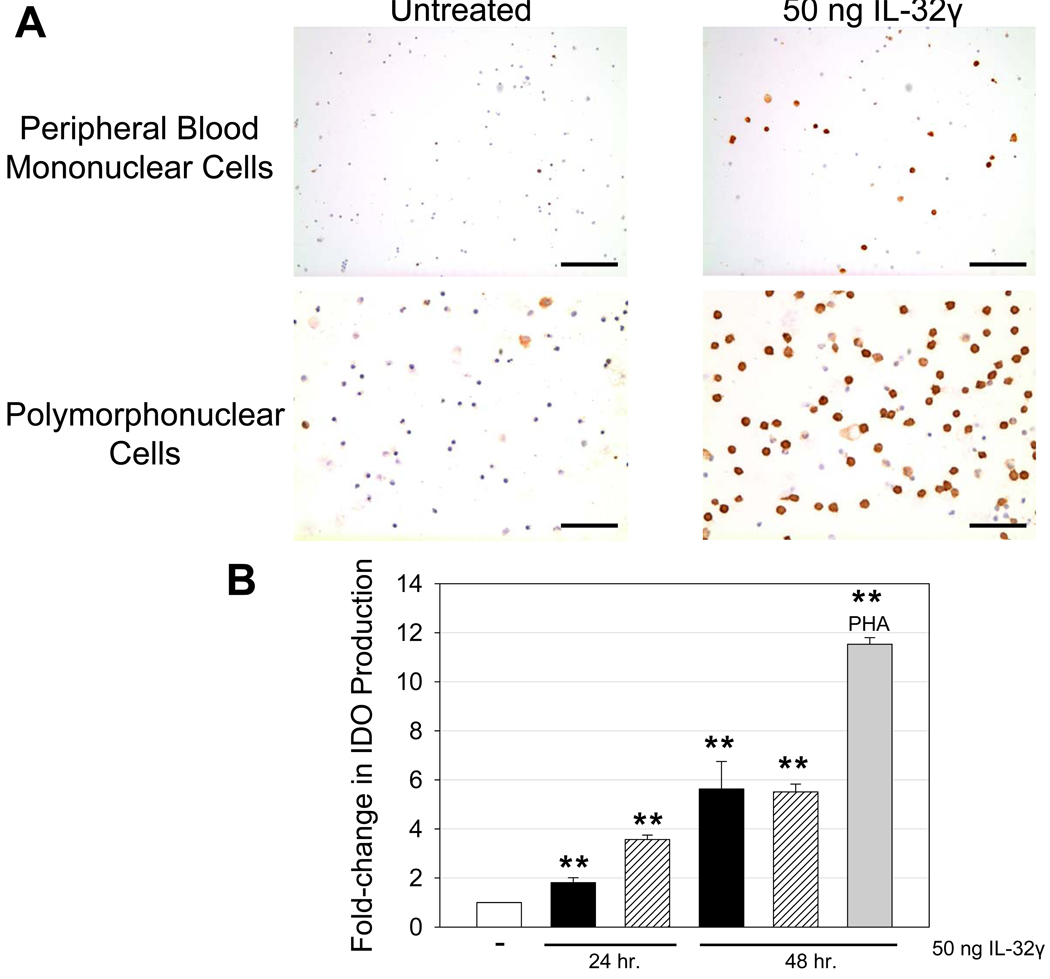

IL-32 induces indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase expression

IL-32 has been categorized as a pro-inflammatory cytokine due to its elevated levels in various inflammatory diseases (13–15) as well as its ability in vitro to induce other pro-inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 (12, 13, 16). In spite of IL-32’s association with inflammation and induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, recent work has also suggested a role for IL-32 in immune suppression through its ability to stimulate IL-10 production (17). To better understand the role of IL-32 during HIV-1 infection, we first examined its effects in vitro. We treated human leukocytes (both polymorphonuclear cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells [PBMCs]) with recombinant IL-32γ, the most biologically active isoform (18), and then examined expression of markers of immune activation or suppression. We found IL-32γ to be a potent inducer of IDO, a tryptophan-degrading enzyme with far-reaching immunosuppressive effects (19). IL-32γ increased IDO expression ~ 6-fold (p < 0.001) in both polymorphonuclear cells and PBMCs (Figure 3). IL-32γ induced IDO production in CD163+ macrophages, CD4+ T cells, Foxp3+ T regulatory (TReg) cells, and CD11c+ dendritic cells (Supplemental Figure 2). In contrast, IL-32γ had minimal effects on immune activation and proliferation, with no detectable increases in cell activation/proliferation markers such as Ki-67, CD38, or CD69 (data not shown), in agreement with a previous report (14).

Figure 3. IL-32γ stimulates the production of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase by both polymorphonuclear and peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical images reveal increased IDO expression in polymorphonuclear and PBMCs treated with 50 ng IL-32γ (IDO-positive cells appear brown while cell nuclei appear blue). A dose-response curve was initially used (5 ng, 50 ng, 500 ng IL-32γ) in designing these in vitro experiments. There was no appreciable change in cell markers at 5 ng compared to untreated controls. However, 50 ng and 500 ng yielded significant changes in IDO expression compared to untreated controls, with little difference between the two dosages. Thus, we report a time-dependent effect of 50 ng IL-32γ on IDO expression in PBMCs. Original magnifications: X400; scale bars: 50 µm. (B) IDO-positive cells were enumerated for each condition and reported as fold-change in IDO production. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM, where 3 independent experiments were performed in triplicate. Black bars represent PBMCs while hashed bars represent polymorphonuclear cells. PBMCs were treated with 5 µg PHA as a positive control. The results are shown with significance where applicable (**, p < 0.001).

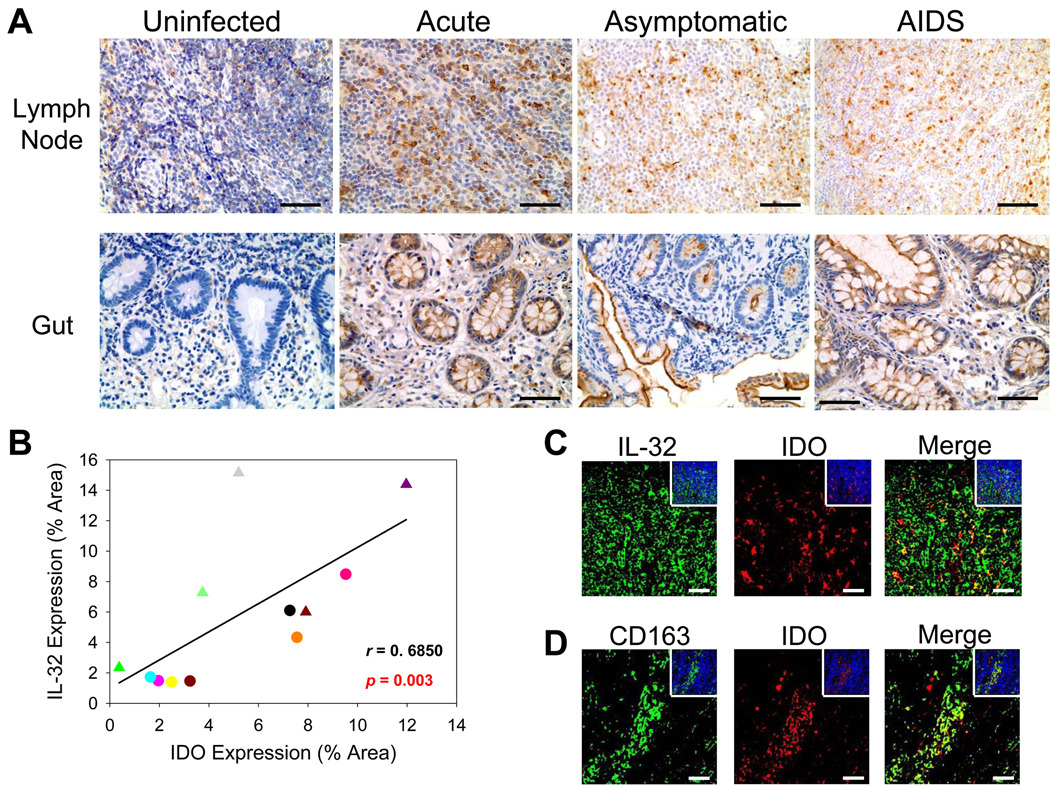

We then showed that IL-32 expression correlated with IDO production in vivo. We stained for IDO in a subset of study individuals and found a similar pattern of protein expression as for IL-32 (Figure 4A), resulting in a significant positive association between IL-32+ cells and IDO expression (r = 0.6850, p = 0.003) (Figure 4B). Moreover, IDO often was co-expressed with IL-32 (Figure 4C), predominantly in LT macrophages (Figure 4D) and gut epithelial cells (Figure 4A). Thus, increased expression of IL-32 during HIV-1 infection coincides with induction of the tryptophan-degrading enzyme IDO in diverse anatomical compartments such as the gut and lymph node, thereby lowering environmental tryptophan (20) which can inhibit immune cell proliferation/activation (21, 22), promote the generation of TReg cells (23, 24), and stimulate expression of other immunosuppressive molecules such as the immunoglobulin-like transcript (ILT) receptors (25).

Figure 4. Increased indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase expression is significantly associated with IL-32 production in both gut and lymph node during HIV-1 infection.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical images reveal increased IDO expression in the gut and inguinal lymph node during HIV-1 infection (IDO-positive cells appear brown while cell nuclei appear blue). Original magnifications: X400; scale bars: 50 µm. (B) IL-32 expression was significantly correlated with IDO expression in both gut and inguinal lymph node during HIV-1 infection. Symbols: circles and triangles represent inguinal lymph node and ileal biopsies, respectively. (C & D) Representative immunofluorescent images of IDO (red staining) and IL-32 or CD163 (green staining) in the inguinal lymph node from HIV-1-infected individuals, showing co-localization between IDO and IL-32 and between IDO and CD163+ macrophages. The insets show the total numbers of cells (cell nuclei appear blue) in each image. Original magnifications: X400; scale bars: 50 µm.

IL-32 induces immunoglobulin-like transcript 4 expression

ILT receptors are cell-surface inhibitory molecules that bind MHC class I and render target cells anergic (26). Since we had previously identified ILT4 from our microarray analysis as a gene increased in expression in LT during HIV-1 infection (6), we examined the possibility that IL-32-induced IDO might be creating a local environment in LT that favors ILT4 expression.

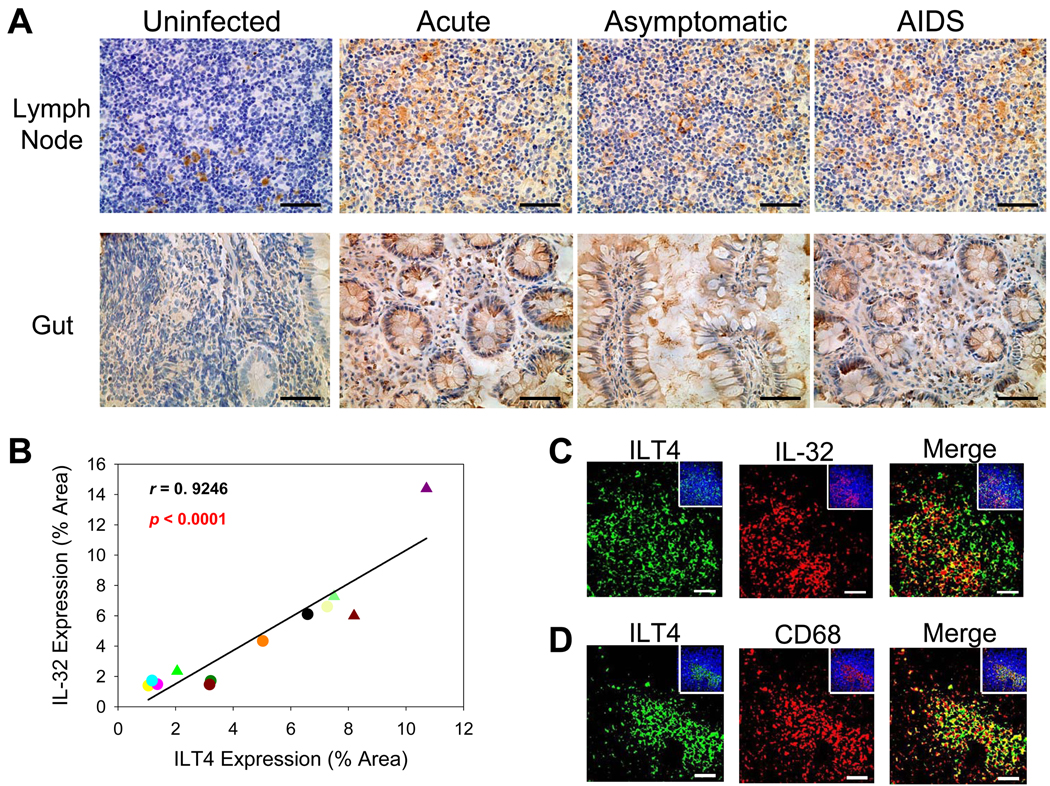

We first tested in vitro whether IL-32γ could induce ILT4 expression in PBMCs. As we had shown for IDO induction, IL-32γ also increased ILT4 expression in PBMCs (~ 2.6-fold, p < 0.001) (Figure 5). In vivo, we also found a similar pattern of protein expression for IL-32 and ILT4 (Figure 6A), resulting in a significant positive association between IL-32+ cells and ILT4 expression (r = 0.9246, p < 0.0001) (Figure 6B). Moreover, ILT4 often was co-expressed with IL-32 (Figure 6C), predominantly in LT macrophages (Figure 6D) and gut epithelial cells (Figure 6A). Not surprisingly, ILT4 and IDO were also significantly associated with one another (r = 0.8790, p < 0.0001) and expressed within the same cell (Supplemental Figure 3). Thus, increased expression of IL-32 during HIV-1 infection likely initiates a cascade of events to moderate immune activation by inducing two potent immunosuppressors, IDO and ILT4, in both gut and lymph node.

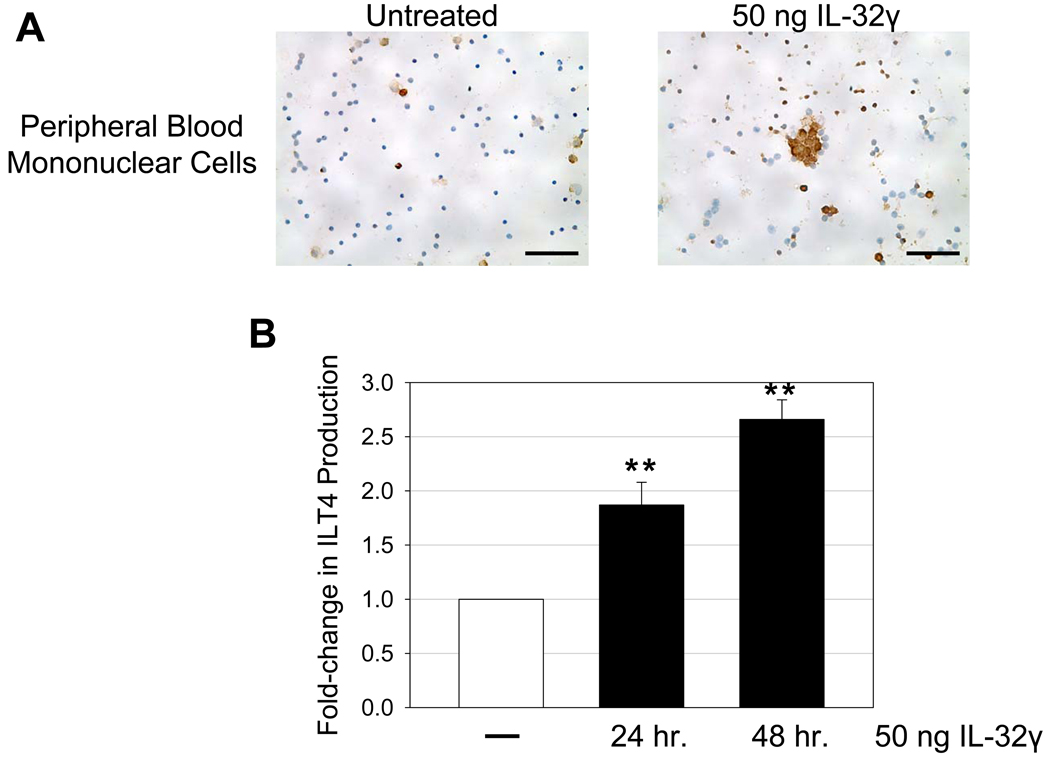

Figure 5. IL-32γ stimulates the production of immunoglobulin-like transcript 4 by peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical images reveal increased ILT4 expression in PBMCs treated with 50 ng IL-32γ (ILT4-positive cells appear brown while cell nuclei appear blue). A dose-response curve was initially used (5 ng, 50 ng, 500 ng IL-32γ) in designing these in vitro experiments. There was no appreciable change in ILT4 at 5 ng compared to untreated controls. However, 50 ng and 500 ng yielded significant changes in ILT4 expression compared to untreated controls, with little difference between the two dosages. Thus, we report a time-dependent effect of 50 ng IL-32γ on ILT4 expression in PBMCs. Original magnifications: X400; scale bars: 50 µm. (B) ILT4-positive cells were enumerated for each condition and reported as fold-change in ILT4 production. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM, where 3 independent experiments were performed in triplicate. The results are shown with significance where applicable (**, p < 0.001).

Figure 6. Increased immunoglobulin-like transcript 4 expression is significantly associated with IL-32 production in both gut and lymph node during HIV-1 infection.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical images reveal increased ILT4 expression in the gut and inguinal lymph node during HIV-1 infection (ILT4-positive cells appear brown while cell nuclei appear blue). Original magnifications: X400; scale bars: 50 µm. (B) IL-32 expression was significantly correlated with ILT4 expression in both gut and inguinal lymph node during HIV-1 infection. Symbols: circles and triangles represent inguinal lymph node and ileal biopsies, respectively. (C & D) Representative immunofluorescent images of ILT4 (green staining) and IL-32 or CD68 (red staining) in the inguinal lymph node from HIV-1-infected individuals, showing co-localization between ILT4 and IL-32 and between ILT4 and CD68+ macrophages. The insets show the total numbers of cells (cell nuclei appear blue) in each image. Original magnifications: X400; scale bars: 50 µm.

IL-32 expression is associated with reduced immune activation, cell proliferation, and cytotoxic factors in vivo

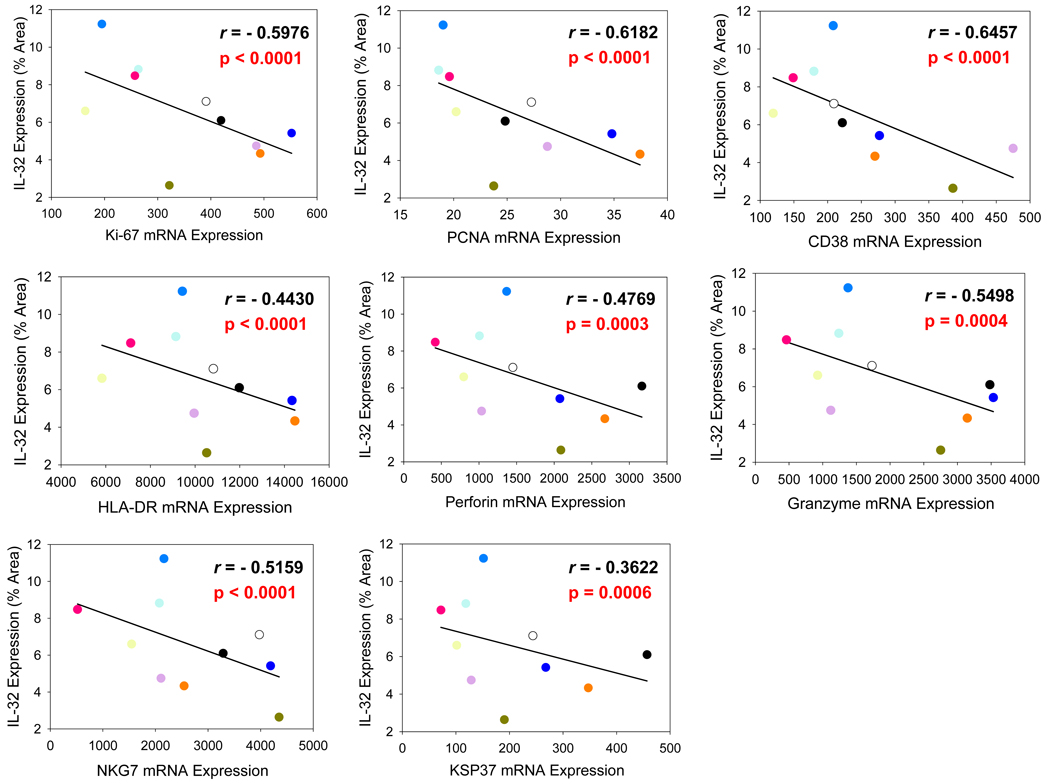

Immunosuppressive molecules such as IDO and ILT4 could play an important role in moderating the immunopathological consequences of chronic immune activation during HIV-1 infection, but these molecules also may be detrimental to the host by dampening the antiviral immune response through inhibition of innate and adaptive cytotoxic functions. Consistent with this concept of a balance between moderating effects on immune activation/proliferation and inhibition of host defenses, we found significant inverse correlations between IL-32 expression and mRNA levels of cell proliferation markers (Ki-67, PCNA), cell activation markers (CD38, HLA-DR), and cytotoxic mediators (perforin, granzyme, natural killer cell group 7 sequence [NKG7], killer-specific secretory protein of 37 kDa [KSP37]) in lymph node (Figure 7).

Figure 7. IL-32 expression in the lymph node of HIV-1-infected individuals is associated with reduced cell proliferation, cell activation, and cytotoxic mediators.

IL-32 expression within the inguinal lymph node was inversely correlated with mRNA levels of cell proliferation markers Ki-67 and PCNA; immune activation markers CD38 and HLA-DR; and cytotoxic mediators perforin, granzyme, NKG7, and KSP37. mRNA levels are taken from Li et al. (6).

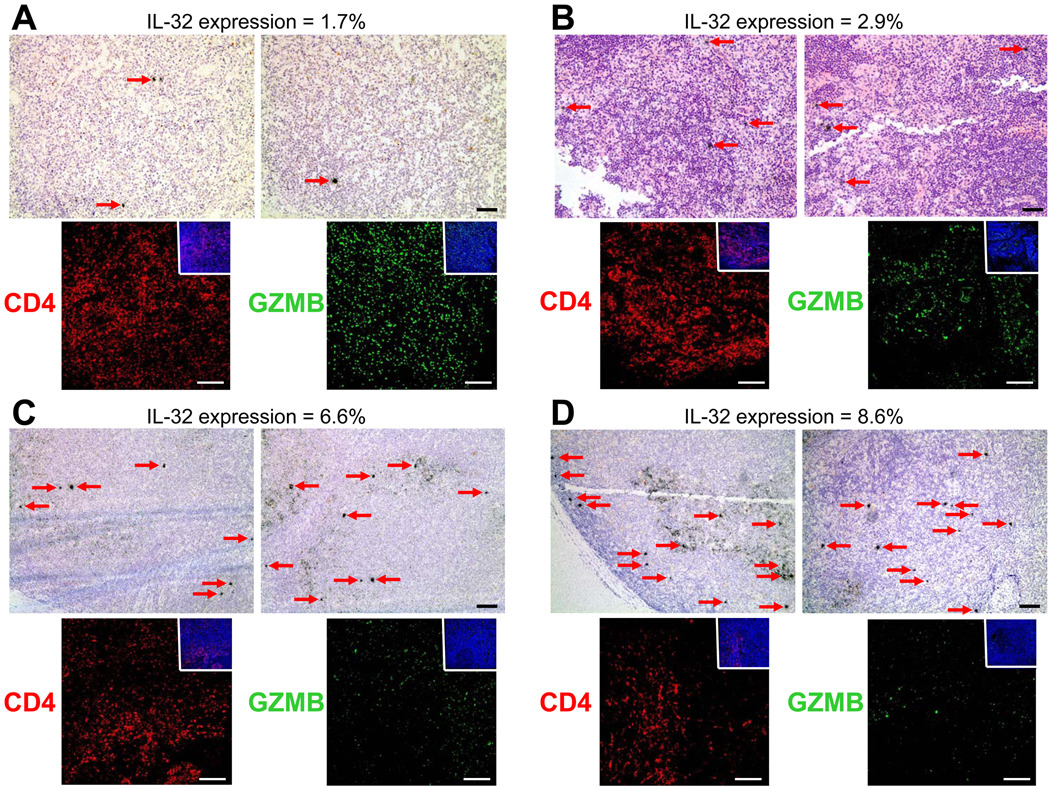

IL-32 expression is associated with HIV-1 replication in vivo and inversely correlates with CD4+ T-cell survival

The immunosuppressive effects of IDO, other immunoregulatory cytokines, and TReg cells have been implicated in facilitating SIV and HIV-1 replication (22, 27, 28). Since IL-32 can promote IDO and ILT4 expression, we looked at the relationship between HIV-1 replication and IL-32 expression in a small subset of lymph node biopsies and found a qualitative relationship between the number of HIV-1-infected cells and IL-32 expression (Figure 8). Consistent with a role in immune suppression, we also found an inverse relationship between IL-32 expression and granzyme-producing cells in the lymph node (Figure 8). Finally, IL-32 expression and augmented HIV-1 replication was inversely correlated with CD4+ T-cell numbers in both peripheral blood (r = −0.451, p = 0.035) (Supplemental Figure 4) and lymph node (Figure 8). These data suggest that IL-32-induced IDO and ILT4 expression may suppress cell proliferation/activation and down-modulate cytotoxic mediators required for effective viral clearance, creating an environment more conducive for productive HIV-1 replication which also contributes to CD4+ T cell depletion.

Figure 8. IL-32 expression in the lymph node of HIV-1-infected individuals is qualitatively associated with productive viral replication, lower granzyme expression, and decreased CD4+ T cell viability.

Representative images reveal a qualitative association between HIV-1 replication (HIV-1 RNA+ cells appear as black silver grains while cell nuclei appear blue) and IL-32 expression in the inguinal lymph node of HIV-1-infected individuals. Immunofluorescent images reveal decreased granzyme B expression (green) and lower CD4+ T cell numbers (red) with increasing IL-32 expression in the same lymph nodes Original magnifications: X100 (light micrographs), X200 (immunofluorescent micrographs); scale bars: 100 µm.

Discussion

IL-32 is thought to play an important role in various inflammatory disorders due to its purported role in fueling inflammation by inducing expression of other pro-inflammatory mediators (9). However, until recently (29), IL-32 has received little attention as a moderator of chronic immune activation. Here, we provide evidence that IL-32 may have such a role in countering immune activation and inflammation during HIV-1 infection by promoting immune suppression via the induction of immunosuppressive molecules IDO and ILT4. This observation complements a previous study in which IL-32 was shown to induce the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10 (17).

The balance between immune activation and immune suppression is critical throughout the immune system, whereby perturbation of this balance can have deleterious, immunopathological consequences for the host (30). Additionally, this balance is crucial in determining the effectiveness and ability of the immune system to initially clear acute infections or partially control persistent infections. Because HIV-1 is usually not cleared in the acute stage of infection (31), the immune system, without antiviral therapy, is confronted over a period of years with the sustained challenge of managing this balance between chronic immune activation, needed to maintain host defenses to partially control persistent viral replication, and moderating the immunopathological consequences of this chronic immune activation.

The transcriptional profiles of the acute, asymptomatic, and AIDS stages of HIV-1 infection (6) have revealed the complexity of managing chronic immune activation in persistent infection. Initially, the host’s immune system responds by up-regulating expression of large numbers of genes that mediate immune activation and innate and adaptive defenses. With the general failure of these defenses in clearing infection, there is an abrupt decrease in expression of most of these genes to levels indistinguishable from HIV-1 uninfected individuals in the asymptomatic stage of infection, which we have interpreted as immunoregulatory mechanisms mounted by the host to strike a balance between moderating chronic immune activation and maintaining host defenses to partially contain infection.

The mediators of this immunoregulatory transition, however, were not immediately obvious in the lists of genes with altered expression, with the exception of IL-32, IDO, and ILT4 (6), and hence the focus on these genes in the work we now report. From the evidence we present, IL-32 certainly could be one of these early immunoregulatory mediators, with increased expression at the right place and right time—in most immune cells during acute HIV-1 infection in both the gut and lymph node as well as in intestinal epithelial cells (Figure 1, Figure 2). The induction of IL-32 itself is likely due to other pro-inflammatory cytokines increased during HIV-1 infection (32), particularly IL-18 (Supplemental Figure 1), which has been shown to be a potent inducer of IL-32 in vitro (12). The antigenicity of HIV-1 itself is unlikely to stimulate IL-32 production as Nold et al. demonstrated infection of PBMCs with various strains of HIV-1 actually inhibited production of this cytokine rather than enhancing it (33).

We had also observed increased expression of ILT4 and IDO in early HIV-1 infection (6) and conjectured that these immunosuppressors were also partly responsible for the immunoregulatory transition. Here we show that IL-32, IDO, and ILT4 are co-regulated and associated with decreased immune activation, proliferation, and cytotoxic host factors. In vitro, IL-32 induced both IDO and ILT4 expression in PBMCs while in vivo, the levels of IL-32 in LT and gut correlated with both IDO and ILT4 expression levels and were, in turn, inversely correlated with markers of cell proliferation and cytotoxic NK and T cell markers.

The role of IDO in HIV-1 infection has been well documented (20, 34) in suppressing various arms of the immune system by depleting locally-available stocks of the essential amino acid tryptophan. A tryptophan-depleted environment has been repeatedly described in HIV-1 infection (35–38) and thought to be responsible for inhibiting essential cellular functions through its potent anti-proliferative and immunosuppressive effects (21, 22, 39). Additionally, high tryptophan catabolism within the environment can promote the local generation of TReg cells (23, 24) and other immunosuppressive molecules (e.g., ILT4) (25), a process which can lead to further IDO induction (34), resulting in a continuous cycle of immunosuppressive amplification.

Like IDO, ILT4 can also serve to further amplify an immunosuppressive environment—ILT4 expression on antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages can inhibit proliferation of immune cells (26, 40), render immune cells anergic and unresponsive to extracellular stimuli (26, 40, 41), and promote the local generation of TReg cells (25, 41, 42). The localization of ILT4 and IDO in vivo, mainly in macrophages, is consistent with these functions.

We think that IL-32, IDO, ILT4, and TReg cells comprise important components of an immunoregulatory axis designed to counter the pathological effects of chronic immune activation in persistent HIV-1 infections and the primate counterparts in pathogenic SIV infections. The price the host pays for these moderating effects are impaired host defenses, ranging from smaller numbers of virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (27, 43) to the decreased expression of cytotoxic effectors (44–46) associated with increased IL-32 expression. In support of this, a recent study showed that splenocytes isolated from mice injected with IL-32-expressing epithelial cells displayed dampened cell-mediated cytotoxicity compared to splenocytes isolated from control mice (47). While IL-32 has been shown in vitro to have interferon-mediated antiviral activity (33), we think in vivo that IL-32’s immunosuppressive effects contribute, at best, to partial control of untreated HIV-1 infection. In sum, although it remains difficult to quantify the suppressive contributions from IL-32 itself in terms of overall cell-mediated cytotoxicity compromised during HIV-1 infection (48), these data, nevertheless, suggest that IL-32 may be a contributing factor in an immunoregulatory axis that collectively acts as a double-edged sword in lentiviral immunodeficiency infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the donor participants in this study and also Colleen O’Neill for help with manuscript submission. We also acknowledge Qingsheng Li for his role in previous microarray experiments (RNA extraction, chip hybridization, and shared analysis).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

A.J.S. designed experiments; A.J.S., C.M.T., S.W.W., and L.D. performed experiments; T.W.S. recruited subjects and procured biopsy samples; C.S.R. performed statistical analyses; A.J.S. and A.T.H. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grant R01 AI056997 (A. T. H.).

Abbreviations used in this paper: LT, lymphatic tissue; IDO, indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase; ILT4, immunoglobulin-like transcript 4; SSC, standard saline citrate; RWB, riboprobe wash buffer; KLRC1, killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily C, member 1; TReg, T regulatory; NKG7, natural killer cell group 7 sequence; KSP37, killer-specific secretory protein of 37 kDa.

References

- 1.Douek DC, Roederer M, Koup RA. Emerging concepts in the immunopathogenesis of AIDS. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:471–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.041807.123549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appay V, Sauce D. Immune activation and inflammation in HIV-1 infection: causes and consequences. J Pathol. 2008;214:231–241. doi: 10.1002/path.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lori F. Treating HIV/AIDS by reducing immune system activation: the paradox of immune deficiency and immune hyperactivation. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2008;3:99–103. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3282f525cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins FM. Cellular antimicrobial immunity. CRC Crit Rev Microbiol. 1978;7:27–91. doi: 10.3109/10408417909101177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Q, Schacker T, Carlis J, Beilman G, Nguyen P, Haase AT. Functional genomic analysis of the response of HIV-1-infected lymphatic tissue to antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:572–582. doi: 10.1086/381396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Q, Smith AJ, Schacker TW, Carlis JV, Duan L, Reilly CS, Haase AT. Microarray Analysis of Lymphatic Tissue Reveals Stage-Specific, Gene-Expression Signatures in HIV-1 Infection. J Immunol. 2009;183:1975–1982. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith AJ, Li Q, Wietgrefe SW, Schacker TW, Reilly CS, Haase AT. Host Genes Associated with HIV-1 Replication in Lymphatic Tissue. J Immunol. 2010;185:5417–5424. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahl CA, Schall RP, He HL, Cairns JS. Identification of a novel gene expressed in activated natural killer cells and T cells. J Immunol. 1992;148:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinarello CA, Kim SH. IL-32, a novel cytokine with a possible role in disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65 Suppl 3:61–64. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.058511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith AJ, Schacker TW, Reilly CS, Haase AT. A Role for Syndecan-1 and Claudin-2 in Microbial Translocation During HIV-1 Infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:306–315. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ecfeca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Z, Schuler T, Zupancic M, Wietgrefe S, Staskus KA, Reimann KA, Reinhart TA, Rogan M, Cavert W, Miller CJ, Veazey RS, Notermans D, Little S, Danner SA, Richman DD, Havlir D, Wong J, Jordan HL, Schacker TW, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Letvin NL, Wolinsky S, Haase AT. Sexual transmission and propagation of SIV and HIV in resting and activated CD4+ T cells. Science. 1999;286:1353–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SH, Han SY, Azam T, Yoon DY, Dinarello CA. Interleukin-32: a cytokine and inducer of TNFα. Immunity. 2005;22:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joosten LA, Netea MG, Kim SH, Yoon DY, Oppers-Walgreen B, Radstake TR, Barrera P, van de Loo FA, Dinarello CA, van den Berg WB. IL-32, a proinflammatory cytokine in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3298–3303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511233103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoda H, Fujio K, Yamaguchi Y, Okamoto A, Sawada T, Kochi Y, Yamamoto K. Interactions between IL-32 and tumor necrosis factor alpha contribute to the exacerbation of immune-inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R166. doi: 10.1186/ar2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shioya M, Nishida A, Yagi Y, Ogawa A, Tsujikawa T, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Takayanagi A, Shimizu N, Fujiyama Y, Andoh A. Epithelial overexpression of interleukin-32α in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149:480–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felaco P, Castellani ML, De Lutiis MA, Felaco M, Pandolfi F, Salini V, De Amicis D, Vecchiet J, Tete S, Ciampoli C, Conti F, Cerulli G, Caraffa A, Antinolfi P, Cuccurullo C, Perrella A, Theoharides TC, Conti P, Toniato E, Kempuraj D, Shaik YB. IL-32: a newly-discovered proinflammatory cytokine. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2009;23:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang JW, Choi SC, Cho MC, Kim HJ, Kim JH, Lim JS, Kim SH, Han JY, Yoon DY. A proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-32β promotes the production of an anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10. Immunology. 2009;128:e532–e540. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi JD, Bae SY, Hong JW, Azam T, Dinarello CA, Her E, Choi WS, Kim BK, Lee CK, Yoon DY, Kim SJ, Kim SH. Identification of the most active interleukin-32 isoform. Immunology. 2009;126:535–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mellor AL, Munn DH. IDO expression by dendritic cells: tolerance and tryptophan catabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray MF. Tryptophan depletion and HIV infection: a metabolic link to pathogenesis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:644–652. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munn DH, Shafizadeh E, Attwood JT, Bondarev I, Pashine A, Mellor AL. Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1363–1372. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boasso A, Herbeuval JP, Hardy AW, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Fuchs D, Shearer GM. HIV inhibits CD4+ T-cell proliferation by inducing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood. 2007;109:3351–3359. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-034785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fallarino F, Grohmann U, You S, McGrath BC, Cavener DR, Vacca C, Orabona C, Bianchi R, Belladonna ML, Volpi C, Santamaria P, Fioretti MC, Puccetti P. The combined effects of tryptophan starvation and tryptophan catabolites down-regulate T cell receptor zeta-chain and induce a regulatory phenotype in naive T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:6752–6761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen W, Liang X, Peterson AJ, Munn DH, Blazar BR. The indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase pathway is essential for human plasmacytoid dendritic cell-induced adaptive T regulatory cell generation. J Immunol. 2008;181:5396–5404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenk M, Scheler M, Koch S, Neumann J, Takikawa O, Häcker G, Bieber T, von Bubnoff D. Tryptophan deprivation induces inhibitory receptors ILT3 and ILT4 on dendritic cells favoring the induction of human CD4+CD25+ Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:145–154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravetch JV, Lanier LL. Immune inhibitory receptors. Science. 2000;290:84–89. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potula R, Poluektova L, Knipe B, Chrastil J, Heilman D, Dou H, Takikawa O, Munn DH, Gendelman HE, Persidsky Y. Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) enhances elimination of virus-infected macrophages in an animal model of HIV-1 encephalitis. Blood. 2005;106:2382–2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boasso A, Vaccari M, Hryniewicz A, Fuchs D, Nacsa J, Cecchinato V, Andersson J, Franchini G, Shearer GM, Chougnet C. Regulatory T-cell markers, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and virus levels in spleen and gut during progressive simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2007;81:11593–11603. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00760-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi J, Bae S, Hong J, Ryoo S, Jhun H, Hong K, Yoon D, Lee S, Her E, Choi W, Kim J, Azam T, Dinarello CA, Kim S. Paradoxical effects of constitutive human IL-32γ in transgenic mice during experimental colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21082–21086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015418107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimitriou ID, Clemenza L, Scotter AJ, Chen G, Guerra FM, Rottapel R. Putting out the fire: coordinated suppression of the innate and adaptive immune systems by SOCS1 and SOCS3 proteins. Immunol Rev. 2008;224:265–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson WE, Desrosiers RC. Viral persistence: HIV's strategies of immune system evasion. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:499–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alfano M, Crotti A, Vicenzi E, Poli G. New players in cytokine control of HIV infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:27–32. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nold MF, Nold-Petry CA, Pott GB, Zepp JA, Saavedra MT, Kim SH, Dinarello CA. Endogenous IL-32 controls cytokine and HIV-1 production. J Immunol. 2008;181:557–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boasso A, Shearer GM. How does indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase contribute to HIV-mediated immune dysregulation. Curr Drug Metab. 2007;8:217–223. doi: 10.2174/138920007780362527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Werner ER, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Jaeger H, Reibnegger G, Werner-Felmayer G, Dierich MP, Wachter H. Tryptophan degradation in patients infected by human immunodeficiency virus. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1988;369:337–340. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1988.369.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuchs D, Forsman A, Hagberg L, Larsson M, Norkrans G, Reibnegger G, Werner ER, Wachter H. Immune activation and decreased tryptophan in patients with HIV-1 infection. J Interferon Res. 1990;10:599–603. doi: 10.1089/jir.1990.10.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gisslén M, Larsson M, Norkrans G, Fuchs D, Wachter H, Hagberg L. Tryptophan concentrations increase in cerebrospinal fluid and blood after zidovudine treatment in patients with HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:947–951. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huengsberg M, Winer JB, Gompels M, Round R, Ross J, Shahmanesh M. Serum kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratio increases with progressive disease in HIV-infected patients. Clin Chem. 1998;44:858–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boasso A, Hardy AW, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Shearer GM. HIV-induced type I interferon and tryptophan catabolism drive T cell dysfunction despite phenotypic activation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang CC, Ciubotariu R, Manavalan JS, Yuan J, Colovai AI, Piazza F, Lederman S, Colonna M, Cortesini R, Dalla-Favera R, Suciu-Foca N. Tolerization of dendritic cells by T(S) cells: the crucial role of inhibitory receptors ILT3 and ILT4. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:237–243. doi: 10.1038/ni760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manavalan JS, Rossi PC, Vlad G, Piazza F, Yarilina A, Cortesini R, Mancini D, Suciu-Foca N. High expression of ILT3 and ILT4 is a general feature of tolerogenic dendritic cells. Transpl Immunol. 2003;11:245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0966-3274(03)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gregori S, Tomasoni D, Pacciani V, Scirpoli M, Battaglia M, Magnani CF, Hauben E, Roncarolo MG. Differentiation of type 1 T regulatory cells (Tr1) by tolerogenic DC-10 requires the IL-10-dependent ILT4/HLA-G pathway. Blood. 2010;116:935–944. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hryniewicz A, Boasso A, Edghill-Smith Y, Vaccari M, Fuchs D, Venzon D, Nacsa J, Betts MR, Tsai WP, Heraud JM, Beer B, Blanset D, Chougnet C, Lowy I, Shearer GM, Franchini G. CTLA-4 blockade decreases TGF-β, IDO, and viral RNA expression in tissues of SIVmac251-infected macaques. Blood. 2006;108:3834–3842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-010637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersson J, Behbahani H, Lieberman J, Connick E, Landay A, Patterson B, Sönnerborg A, Loré K, Uccini S, Fehniger TE. Perforin is not co-expressed with granzyme A within cytotoxic granules in CD8 T lymphocytes present in lymphoid tissue during chronic HIV infection. AIDS. 1999;13:1295–1303. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199907300-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang D, Shankar P, Xu Z, Harnisch B, Chen G, Lange C, Lee SJ, Valdez H, Lederman MM, Lieberman J. Most antiviral CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection do not express high levels of perforin and are not directly cytotoxic. Blood. 2003;101:226–235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang Y, Karita E, Castor D, Jolly PE. Characterization of CD8+ T lymphocytes in chronic HIV-1 subtype A infection in Rwandan women. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2005;51 Suppl:OL737–OL743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chae JI, Shim JH, Lee KS, Cho YS, Lee KS, Yoon do Y, Kim SH, Chung HM, Koo DB, Park CS, Lee DS, Myung PK. Downregulation of immune response by the human cytokines Interleukin-32α and β in cell-mediated rejection. Cell Immunol. 2010;264:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lieberman J, Manjunath N, Shankar P. Avoiding the kiss of death: how HIV and other chronic viruses survive. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:478–486. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.