Abstract

Microvascular mural or perivascular cells are required for the stabilization and maturation of the remodeling vasculature. However, much less is known about their biology and function compared to large vessel smooth muscle cells. We have developed lines of multipotent mesenchymal cells from human embryonic stem cells (hES-MC); we hypothesize that these can function as perivascular mural cells. Here we show that the derived cells do not form teratomas in SCID mice and independently derived lines show similar patterns of gene expression by microarray analysis. When exposed to platelet-derived growth factor-BB, the platelet-derived growth factor receptor β is activated and hES-MC migrate in response to a gradient. We also show that in a serum-free medium, transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) induces robust expression of multiple contractile proteins (α smooth muscle actin, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, smooth muscle 22α, and calponin). TGFβ1 signaling is mediated through the TGFβR1/Alk5 pathway as demonstrated by inhibition of α smooth muscle actin expression by treatment of the Alk5-specific inhibitor SB525334 and stable retroviral expression of the Alk5 dominant negative (K232R). Coculture of human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) with hES-MC maintains network integrity compared to HUVEC alone in three-dimensional collagen I-fibronectin by paracrine signaling. Using high-resolution laser confocal microscopy, we show that hES-MC also make direct contact with HUVEC. This demonstrates that hESC-derived mesenchymal cells possess the molecular machinery expected in a perivascular progenitor cells and can play a functional role in stabilizing EC networks in in vitro three-dimensional culture.

Introduction

Pathological ischemia from a lack of blood supply results in multiple chronic diseases such as myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetic wound healing, and retinopathy. One of the principal technical barriers for tissue engineering of organ replacements is provision of sufficient microcirculatory system to support the metabolic needs of the therapeutic cells.1 Therefore, to advance in therapeutic vascularization it is critical to understand microvascular biology, vessel assembly, and component cell functionality.

Much work has been done to elaborate the processes and mechanisms controlling vascular development from its initial stages of blood island formation, vascular plexus, and remodeling to the mature circulatory system.2 Much of this work has focused on the endothelium and smooth muscle cell (SMC) of large arteries,3 whereas less is known of the perivascular cell (PC) supporting the microvasculature.4 Two sources of PC are believed to be (i) migrating SMC as the vasculature expands and (ii) mesenchymal cells from the surrounding tissues.5 Although some markers are commonly used for PC identification, such as α smooth muscle actin (αSMA), NG2, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ), RGS5, aminopeptidase A and N5–7 they are not universally expressed, but rather specific to developmental stage, tissue bed, and even species.8,9

Cells typically used for modeling PC are isolated from retina,10 brain,11 and 10T1/2.12 Embryonic stem cells have been shown capable of modeling early vascular development in embryoid bodies13 and a potential source for component cells.14 Another potential source of myogenic cells are adult mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSC).15,16 Many reports have indicated the multipotent capacity of PC.17,18 Recently, it has been suggested that MSC are a subpopulation of PC.19

We have derived multipotent mesenchymal progenitor cells from human embryonic stem cells (hES-MC)20 displaying characteristics attributed to PC, such as being osteogenic, chondrogenic, and myogenic.18,19,21 Because these cells show similarities in functional capacity to PC, we hypothesized that hES-MC are a mesenchymal progenitor that can function as PC. Here we show that hES-MC do not form teratomas in vivo, are responsive to PDGF-BB, use the transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1)/Alk5 signaling axis for inducing multiple contractile proteins, and stabilize human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) networks in three-dimensional (3D) culture by paracrine and direct cell–cell contact.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

hES-MC were derived from H9 (WiCell) hESC and subsequently cultured as described previously.20 HUVEC and microvascular EC were purchased commercially and cultured in EGM2-MV (Lonza, Walkersville, MD).

Teratoma formation

hES-MC were concentrated to 2×106 cells in 100 μL Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 and then injected intramuscularly in SCID mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). After 28 days the injected tissue was excised and observed for teratoma formation. Excised tissue was embedded in paraffin and serial sections hematoxylin and eosin stained. A minimum 10 sections were taken from each sample. All animal studies were performed in accordance with the University of Louisville IACUC approval.

Microarray and analysis

Three hES-MC (B4, E22h, and E28h) derived independently from hESC were grown as described. Confluent cultures were prepared for total RNA isolation using Qiagen Qiashredder and RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total sample RNA was labeled with Cy3 and Universal Human Reference RNA control (#740000; Strategene, Santa Clara, CA) was labeled with Cy5. The samples and control were added to Agilent Human Whole Genome microarray (G4112A) and the array data extracted using Agilent G2567AA Feature Extraction Software v9.5 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The two-color microarray data were normalized with Lowess normalization. Each signal intensity was flagged with P (present), M (marginal), and A (absent) with the importance of the signal being P>M>A. Probes were filtered by the rule that at least one out of three was flagged with P or M. Based on the filtered data, we generated lists for each derived cell (B4, E22h, and E28h) versus the control for gene expression. The filtered gene expression for each cell line was compared and the Pearson Correlation Coefficient calculated.

PDGF-BB/PDGFRβ dose response

hES-MC were grown to confluence as described above and serum starved overnight. Samples were treated with varying concentrations of PDGF-BB (R&D Systems, Meneapolis, MN) for 5 minutes. Samples were processed for Western blot as described below.

Migration assay

hES-MC were serum starved over night, and then plated in an inner transwell (8 μm pore size, BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA). Cells were then exposed to the serum-free medium (SFM), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), human microvascular ECs (Lonza), or PDGF-BB (10 ng/mL). After 4h the transwell membrane was fixed in 2% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), the inner remaining cells removed with Q-tip, and then stained with DAPI (1:10,000; Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). A minimum of 10 fields per condition were used to count cell nuclei with an Olympus IX71 (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Cell counts were averaged, and statistical significance at the p<0.05 level was determined by student's t-test.

Contractile protein induction

hES-MC were grown to confluence in EGM2-MV and then the medium was changed to SFM consisting of DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1 μM insulin, 5 μg/mL transferrin, 0.2 mM ascorbate (Sigma-Aldrich), and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen)22 for 2 days. After 2 days, the medium was changed to SFM with supplements TGFβ1 (1 ng/mL), PDGF-BB (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems), or 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT) for an additional 2 days. For inhibition of the Alk5/TGFβR1, a dose curve of SB525334 (Tocris, Ellisville, MO) was performed for inhibition of αSMA at 1 ng/mL of TGFβ1. Ten micromolars of SB525334 was used in the subsequent experiments.

Western blot

For Western blotting, cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl [Sigma-Aldrich], 1 mM PMSF [Fisher], 1% Triton X-100 [MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH], 0.5% SDS [Fisher], and 1×protease inhibitor cocktail [Pierce, Rockford, IL]). Protein concentration was determined using micro-BCA assay (Pierce). SDS-PAGE was performed and proteins transferred to Immobilon-FL PDVF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in TBS-T (Fisher) and incubated for 1h at room temperature or 4°C over night with primary antibody (Phosphorylated PDGFRβ [PK1008; Calbiochem, Temecula, CA], αSMA [SC32251], SM22α [SC18513], β-actin [SC69879; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA], smooth muscle myosin heavy chain [M7786], and Calponin [C2687, Sigma]). The primary antibody was detected with DyLight-488 and β-actin with DyLight-649 (Pierce) and image acquired on a Typhoon 9400 scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). Densiometry was performed using NIH ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/).

Immunocytochemistry

hES-MC were grown on glass chamber slides (LabTec, Nunc, Denmark) to confluence and serum starved for 2 days with SFM. Then, cultured for another 2 days in supplemented SFM. The cells were fixed with 2% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min, blocked in 5% goat serum (MP Biomedicals), incubated with αSMA primary antibody (SC32251) and DyLight-488, and then finally stained with DAPI (1:10,000; Fisher). Images were acquired on an Olympus IX71 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

Alk5 retrovirus vectors

Alk5 wild-type (WT) and dominant negative (K232R) retroviral vectors were kind gifts from Drs. Andrei Bakin and Carlos Arteaga of Roswell Park Cancer Institute and Vanderbilt University, respectively.23 The empty retrovirus (pBMN-I-GFP, Addgene plasmid 1736, Garry Nolan Lab) was purchased from Addgene (www.addgene.org). The plasmids were prepared as follows. Phoenix-Ampho packaging cells (Orbigen, San Diego, CA) were plated 2×106/60 mm plate (BD Biosciences) and grown overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 in the growth medium consisting of DMEM high glucose, 10% FBS (Hyclone), and L-glutamine (Invitrogen). At 60%–70% confluence the growth medium was changed to OptiMem (Invitrogen) without pen/strep. The Phoenix-Ampho cells were transfected with Alk5 vectors with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's instructions. The transfected cells were incubated at 32°C and the packaged virus harvested after 48h. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm SFCA filter (Corning, Lowell, MA). The virus was concentrated by filtering through a Centricon Plus-70 (Millipore). hES-MC were seeded at 0.5×106/35 mm (BD Bioscience) plate and cultured overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. The following day a 1:2 dilution of concentrated virus supernatant with EGM2-MV medium and 15 μg/mL of polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the culture and incubated overnight at 32°C in 5% CO2. After 24 h the medium was changed to EGM2-MV and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 3 or 4 days, transduced cells were sorted at the University of Louisville Brown Cancer Center flow cytometry core facility for green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression and subcultured in EGM2-MV. The same procedure was followed for generation of HUVEC stably expressing DsRed-Express by pMXs retroviral transduction (Addgene plasmid 22724; Toshio Kitamura Lab).24 All recombinant DNA work was approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Preparation of HUVEC and hES-MC coculture networks

HUVEC and hES-MC (with and without GFP retrovirus transduction) were grown to confluence and resuspended in 1.5 mg/mL rat tail collagen I (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), 90 μg/mL fibronectin (Fn; Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 106/mL, and 0.2×106/mL, respectively. Five hundred microliters of HUVEC alone or HUVEC+hES-MC in the collagen I-Fn solution was transferred to a four-well IVF Nunclon dish (TC Area=2 cm2; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and allowed to polymerize for 30 min at 37°C. Each well was cultured for 6 days in coculture medium (DMEM/F12 [Invitrogen], 40 ng/mL VEGF and bFGF [R & D Systems], and 1× pen/strep [Invitrogen]). The medium was changed every 2–3 days.

Transwell and conditioned medium

HUVEC alone or cocultured with hES-MC (positive control) were seeded into collagen-Fn gels and placed into the inner well of 4-μm-pore-size transwell (BD Biosciences). For HUVEC alone, hES-MC were seeded into the outer well or exposed to the coculture medium in the absence of hES-MC (negative control). Cells were cultured for 6 days and then imaged on an Olympus fluorescence microscope. To test hES-MC conditioned medium, hES-MC were seeded into a six-well plate (BD Biosciences) and cultured in MV medium. Each day a new well was washed and the coculture medium added for 24 h to produce the conditioned medium. The nonconditioned medium was also placed into a six-well plate in the absence of hES-MC for the same length of time. The conditioned or nonconditioned medium was transferred to HUVEC only cultures in collagen-Fn gels for 6 days. Cell constructs were imaged as already described.

Mono- and coculture network analysis

Collagen I-Fn constructs were fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature, blocked with 5% goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline for 2 h at room temperature, and then labeled with UEA1-rhodamine (1:100) or transduced with pMXs-DsRed when hES-MC-GFP cells were used or UEA1-fluorescein (1:200; Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) when hES-MC were used. The constructs were incubated for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. For network analysis, constructs were imaged at 10× using an Olympus BX61SWI laser scanning confocal microscope. For each sample, five views (each corner and middle) were taken on an established grid. The stage was preset for X–Y and Z coordinates using FluoView software (Olympus). Confocal image stacks were first imported into NIH ImageJ, converted to 8-bit grayscale, stack attributes noted, and saved for further processing in a commercial image processing software–Amira (Visage Imaging, San Diego, CA) as originally described by Krishnan et al.25 Briefly, images were corrected for imaging depth, deconvolved, median filtered, and binarized using an automatically generated threshold value for each image stack in Matlab (MathWorks Inc, Natick, MA). These binarized images were then segmented and size filtered to remove very small debris and skeletonized. These skeletonized data were then parsed by a custom C++ program–WinFiber3D (Musculoskeletal Research Labs, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT; http://mrl.sci.utah.edu/software/winfiber3d) as described earlier.25 The 3D co-ordinates from the skeletonized data were evaluated to obtain the total number of vessels, the number of branch points, the total number of end points, segment (section between two nodes–branch or end), and vessel lengths and diameters. HUVEC and hES-MC interaction images were acquired at 60×using sequential scanning and co-contact points determined from skeletonized images as described. Coculture structures were separated into nodes, branches, and segments and the percentage of surface contact for each cell type calculated.

Statistical analysis

Western blot densiometry was analyzed using the Student t-test, with p<0.05 considered significant. For quantitative image analysis the use of different imaging depths necessitated a comparison of image stack volumes to rule out and accommodate for imaging volume bias. The total stack volume was first internally normalized by setting the lowest volume to 1, and this number was used to normalize data from the corresponding image stack as appropriate. The normalized data from the hES-MC containing (Plus) and control groups (Minus) were then compared in SigmaStat (Systat, San Jose, CA), using student t-tests and two-way analysis of variances or its nonparametric equivalent, the Mann-Whitney U-test, where the assumptions of normality and equal variance were violated. However, the independent sample t-tests are considered sufficiently robust to these violations where the sample sizes are sufficiently high, equal, and the ratio of the sample variances are relatively small.26 This was verified where independent sample t-tests were used for statistical significance. Given the large variation typically seen in morphological data of such skeletonized networks, the more appropriate metric, the geometric mean was used in lieu of the arithmetic mean when possible. A total of 61 different stacks from random areas of 13 different constructs in each treatment group were examined and the mean and standard error reported.

Results

hES-MC do not form teratomas

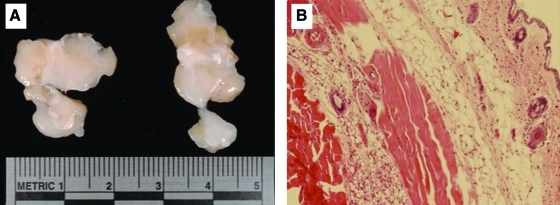

Because hES-MC are derived from hESC we examined their potential for teratoma formation when implanted in SCID mice. Two million hES-MC were injected intramuscularly in a 100 μL bolus then harvested after 28 days. In Figure 1A the muscle was resected and showed no signs of teratoma formation (n=3). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of muscle tissue was normal with no indication of tumor formation (Fig. 1B). This indicates that hES-MC, though multipotent,20 do not retain the hESC capacity to form teratomas.

FIG. 1.

hES-MC do not form teratomas. (A) hES-MC were injected intramuscularly at a concentration of 2×106/100 μL of SCID mice. After 28 days the muscle was excised and examined for teratoma formation. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of serial muscle sections showed no abnormal tissue formation from implanted hES-MC. (n=3). hES-MC, mesenchymal cells from human embryonic stem cell. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

Microarray analysis of different hES-MC lines

To determine if the hES-MC differentiation protocol consistently yielded the same cell type we performed a microarray analysis on three lines (B4, E22h, and E28h) derived at separate times from the H9 cell line.20,27 Using the Agilent whole human genome array (G4112A), the filtered data set (see Materials and Methods) of 18,628 genes showed common levels of expression between the three derived cell lines under normal proliferation culture conditions. When examined by regression analysis, the Pearson coefficient was 0.91, 0.93, and 0.89 for B4 versus E22h, B4 versus E28h, and E22h versus E28h, respectively (Fig. 2). This suggests that the hES-MC differentiation protocol derives a reproducible cell phenotype.

FIG. 2.

Microarray analysis of three independently derived hES-MC. hESC line H9 was differentiated three times to form hES-MC (lines B4, E22h, and E28h). Each line was tested for gene expression using Agilent Whole Human Genome microarray with the Universal Human Reference control RNA. Linear regression plots comparing each hES-MC line and calculated Pearson's correlation coefficient indicating similarity of gene expression profiles.

hES-MC are PDGF-BB responsive

A key event in assembly of the microvasculature is EC recruitment of mural cells from surrounding mesenchyme, and PDGF-BB/PDGFR-β plays a major role in this process.28,29 Therefore, if hES-MC can function as a perivascular mural cell, they should be responsive to PDGF-BB/PDGFR-β signaling. We utilized an 8 μm pore transwell with hES-MC seeded in the inner well and exposed them to SFM without supplements, 10% FBS, or microvascular EC cultured in the outer well. In Figure 3A we see that hES-MC migrate toward microvascular EC in statistically significant numbers compared to control (#p<0.05). Because it was unknown what attracted hES-MC to the EC, we next tested if hES-MC would migrate toward PDGF-BB in a transwell assay (Fig. 3B). Again, hES-MC migrated toward the PDGF-BB gradient in statistically significant numbers compared with control (#p<0.05). We then examined if hES-MC expressed the PDGFR-β and if it was activated by PDGF-BB (Fig. 3C). hES-MC were serum starved and then exposed to different concentrations of PDGF-BB. By Western blot PDGFR-β was phosphorylated in a dose-dependent fashion reaching a maximum at 40 ng/mL and plateauing at 80 ng/mL. This indicates that hES-MC possess the functional signaling machinery that may allow for recruitment to an immature EC vascular plexus.

FIG. 3.

hES-MC are responsive to PDGF-B signaling. (A) hES-MC migrate to microvascular EC in a transwell assay. (p<0.05) (B) When exposed to recombinant PDGF-B, hES-MC move toward the signal source in a transwell. (p<0.05) (C) hES-MC express the PDGFR-β and it is phosphorylated in a dose-dependent manner (n=3). PDGF-B, platelet-derived growth factor B; PDGFR-β, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β; FBS, fetal bovine serum. NC, negative control; μVEC, microvascular endothelial cell.

hES-MC expression of αSMA is serum independent

We have shown previously that hES-MC can be induced to express αSMA, though at low levels, when exposed to TGFβ1 in the presence of serum.20 Therefore, we examined the effect of serum on hES-MC expression of αSMA (Fig. 4). hES-MC were grown to confluence in four-well chamber slides and exposed to±TGFβ1 (1 ng/mL) with or without 10% serum for 2 days and then immunostained for αSMA (Fig. 4A). As expected, when hES-MC were cultured with or without serum and not exposed to TGFβ1, no induction of αSMA occurred (left panels). When hES-MC were cultured without serum but with TGFβ1, virtually the entire culture stained positive for αSMA (top right panel). In contrast, when serum was included in the culture, only very low levels of αSMA were detected (bottom right panel). We next quantified αSMA expression by Western blot for the two cell lines, B4 and E28h (Fig. 4B), when exposed to SFM alone22 or supplemented with TGFβ1 (1 ng/mL), PDGF-BB (10 ng/mL), or 10% FBS (all in the basal SFM). When hES-MC were cultured in SFM we saw variation in the expression of αSMA. However, in each experiment when hES-MC were exposed to TGFβ1 the level of αSMA was always significantly greater than SFM alone. When exposed to PDGF-BB or FBS the level of αSMA was always repressed. This suggests that the derived hES-MC are responsive to signals known to differentially regulate the expression of αSMA in muscle cells.

FIG. 4.

TGFβ1 induces αSMA expression under serum-free conditions. (A) hES-MC were grown to confluence in chamber slides and cultured for 2 days in SFM, after which cells were maintained in SFM alone (top left), addition of 10% FBS (bottom left), 1 ng/mL TGFβ1 (top right), or both (bottom right). Cells were immunostained for αSMA and imaged at the same light exposure conditions. (B) hES-MC were grown to confluence and then cultured in SFM alone or supplemented with TGFβ1 (1 ng/mL), PDGF-B (10 ng/mL), or 10% FBS. αSMA expression was detected by Western blot and quantified by densiometry. Exposure to TGFβ1 produced a significant (p<0.05) increase in αSMA compared to control. αSMA expression was not different from control in the presence of PDGF-B or FBS (n=3). (Left column (blue)=B4, right column (red)=E28h). TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1; SFM, serum-free medium; αSMA, α smooth muscle actin. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

Alk5 regulates hES-MC expression of contractile proteins

TGFβ1 has been shown to induce expression of αSMA in SMC and PC; therefore, we hypothesized that contractile protein expression was mediated through TGFβR1/Alk5. We treated hES-MC with the Alk5-specific inhibitor SB525334.30 As seen in Figure 5A, exposure of hES-MC to TGFβ1 (1 ng/mL) induces αSMA expression as detected by immunocytochemistry. At 0.1 μM, SB525334 begins to inhibit the expression of αSMA, which is completely blocked by exposure to 10 μM of inhibitor. Since αSMA can be expressed by multiple cell types depending on developmental stage (e.g., cardiomyocytes and skeletal muscle) or activation (e.g., fibroblasts), we wanted to know if hES-MC could express other contractile proteins (Fig. 5B). When exposed to TGFβ1 the two cell lines, B4 and E28h, were induced to express calponin, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SM-MHC), and smooth muscle 22α (SM22α). Expression of these proteins was significantly reduced by exposure to the Alk5 inhibitor SB525334 (Fig. 5C). Alk5 can be transformed into a kinase-dead receptor by point mutation of the lysine (K) 232 to arginine (R).31 We stably transduced hES-MC with a retrovirus expressing WT and dominant negative (K232R) forms of Alk5 as well as the empty vector. Transduced cells were exposed to±TGFβ1 (1 ng/mL) and quantified by Western blot. As can be seen in Figure 6, when exposed to TGFβ1, both the empty and WT-expressing cells demonstrated robust induction of αSMA. However, expression of αSMA was significantly reduced by expression of dominant negative Alk5-K232R. This suggests that hES-MC are functionally capable of expressing multiple contractile proteins and that expression is mediated through the TGFβ1/Alk5 signaling axis.

FIG. 5.

TGFβ1 regulates contractile protein expression through Alk5 receptor. (A) hES-MC were grown to confluence and treated with 1 ng/mL TGFβ1 and increasing dose of the TGFβR1/Alk5 inhibitor SB525334. By immunostaining, SB525334 inhibited αSMA protein expression in a dose-dependent manner. (n=3) (B) hES-MC (B4 and E28h) were grown to confluence and exposed to TGFβ1 (1 ng/mL)±10 μM SB525334. Western blot for the contractile proteins calponin, SM-MHC, SM22α, and αSMA all showed downregulation of expression when treated with SB522334. (C) Densiometric quantification of Western blots from (B) indicate significant downregulation of contractile protein expression when exposed to SB525334 (n=3, *p<0.05). SM-MHC, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain; SM22α, smooth muscle 22α; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

FIG. 6.

Dominant negative Alk5-K232R inhibits αSMA expression. hES-MC were transduced with retrovirus for empty vector, Alk5-WT or Alk5-K232R (kinase dead, dominant negative). Stable GFP expressing cells were sorted and subcultured. Stably transduced cells were grown to confluence and then exposed to±TGFβ1 in SFM conditions. Both empty and WT-transduced cells showed significant upregulation of αSMA expression (*p<0.05). In contrast, cells expressing the dominant negative vector K232R did not have significantly different expression to control (n=4). WT, wild type.

hES-MC stabilize HUVEC networks in 3D collagen-Fn

We hypothesized that hES-MC are perivascular precursors and, therefore, tested to see if they can function to stabilize HUVEC networks in 3D collagen-Fn gels. We plated HUVEC alone or in the presence of hES-MC for 6 days when the constructs were imaged with a laser scanning confocal and networks quantified (Fig. 7). HUVEC alone retained formation of multiple short network-like structures (Fig. 7A, left panel). On the other hand, when HUVEC were cultured in the presence of hES-MC extensive HUVEC networks were found throughout the collagen I-Fn construct (Fig. 7A, right panel).

FIG. 7.

hES-MC quantification of HUVEC network stability. (A) Representative image of HUVEC±hES-MC in 3D collagen I-Fn gel after 6 days (left: −hES-MC; right: +hES-MC; 10×). (B) Total vessels (networks) and branch points per volume-normalized samples. (C) Total network length (sum of all vessels or networks) and the average network length per volume-normalized sample. (D) Volume-normalized average branch points per continuous vessel (network) structure. (E) Non-volume-normalized average segment lengths and diameters (UEA1-Rhodamine; mean±SE; *significant difference). HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

Because the imaged stack volume of the hES-MC (Plus) group was significantly higher than the hES-MC (Minus) group (Mann-Whitney rank sum test, p<0.001), we normalized subsequent measurements to the imaged volume for every stack. The total number of contiguous networks of multiple segments was significantly higher in the absence of hES-MC (Mann-Whitney rank sum test, p<0.001), whereas there were no effects on the number of total branch points per volume normalized samples (Fig. 7B). The sum of all the cord segments normalized to its volume did not differ significantly between the treatment groups (Mann-Whitney rank sum test) (Fig. 7C). However, the average total length of segments per network was significantly higher in the presence of hES-MC (Mann-Whitney rank sum test, p=0.010). Furthermore, the addition of hES-MC clearly induced a higher degree of branching (Fig. 7D) (Mann-Whitney rank sum test, p=0.023). It is thus clear that the addition of hES-MC results in the formation of fewer but more extensive network structures with a higher degree of branching (Fig. 7D). Finally, both the mean segment length (Mann-Whitney rank sum test, p=0.031) and segment diameter (Mann-Whitney rank sum test, p=0.021) show a significant increase in the presence of hES-MC (Fig. 7E). This result must, however, be interpreted with caution as the magnitude of this difference ranges only from 1 to 2.5 μm and could be within the noise range of the image binarization process (the voxels are typically 2.5 μm×2.5 μm×3 μm).

We then asked if the stability of the coculture was mediated by paracrine factors and if serum could be omitted from the medium. HUVEC were plated in a collagen-Fn gel with (Positive Control) or without hES-MC (Fig. 8A) in a 4 μm pore size transwell. As a negative control, no hES-MC were plated in the outer well, whereas hES-MC were plated at 106/well of a six-well plate and the transwells inserted for 6 days with two medium changes. As expected, the cocultured cells maintained HUVEC network, whereas the HUVEC alone, without hES-MC in the outer well, did not maintain network structures (Data not shown). However, HUVEC alone cultured with hES-MC in the outer well formed networks that persisted for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 8A, middle). We plated HUVEC±hES-MC in collagen gels and tested if the hES-MC conditioned medium (CM) would stabilize HUVEC networks (Fig. 8A, right). Again, coculture (positive control) maintained networks, whereas HUVEC alone cultured in the nonconditioned medium did not (Data not shown). When HUVEC were exposed to hES-MC-CM, networks were formed and persisted similarly to the transwell experiments, suggesting that hES-MC stabilize HUVEC by unknown paracrine factors.

FIG. 8.

hES-MC stabilize HUVEC networks in 3 days collagen-Fn by paracrine signaling and direct contact. (A) Stable HUVEC networks seen in coculture with hES-MC (left) are recapitulated by HUVEC alone in a transwell assay preventing direct culture (middle) and when exposed to the hES-MC-conditioned medium (right). (B) Confocal laser microscopy of HUVEC-expressing DsRed and hES-MC-expressing GFP (60×) was volume rendered for image analysis. (C) Image stacks were skeletonized and direct contact locations determined and highlighted. The example image displays hES-MC (white) and where HUVEC contact (purple). (D) Network architectures were separated into nodes, branches, and segments and the percentage of HUVEC contact on hES-MC (hES-MC) and hES-MC contact on HUVEC (HUVEC) was calculated. GFP, green fluorescent protein. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

To determine if HUVEC and hES-MC make direct contact, image stacks were acquired by confocal microscopy of 6 days' cocultures (Fig. 8B). The image stacks were volume rendered and skeletonized (Fig. 8C), and the direct contact between the two different channels (Green vs. Red) is indicated by purple, demonstrating that HUVEC and hES-MC make direct heterotypic contact. The skeletonized images can be quantified for the area percentage where the two heterotypic cells make contact. We separated the network structures into nodes (locations of multiple branches), branches (“Y” separations, Fig. 8B), and segments (links between branches and nodes) (Fig. 8D). The nodes showed the lowest interaction most likely because they are primarily composed of EC. Branches showed the next highest interaction ranging from almost 4% to 6%, whereas segments showed the highest interaction with just over 6% of HUVEC surface in contact and though there was high variation, almost 12% of hES-MC surface was in contact with HUVEC. Although hES-MC are in direct contact with HUVEC it is unclear how this contact is mediated or how much contact is necessary for network stabilization. Taken together, this indicates that hES-MC have the ability to play a functional role in stabilizing endothelial network structures in 3D culture.

Discussion

The major findings of this study are (i) hES-MC are reproducible multipotent cells that are not tumorigenic, (ii) hES-MC are responsive to signaling mechanisms associated with perivascular progenitor cells such as PDGF-BB and TGFβ1, and (iii) hES-MC play a functional role to stabilize HUVEC networks in 3D collagen I-Fn constructs by paracrine and direct contact mechanisms.

One of the key characteristics of hESC is the capability to produce all of the cells of the body, and it is hoped that this ability can be harnessed to generate cells of therapeutic value. However, several hurdles exist that prevent achieving this goal. Because hESC can produce all cells of the body, they can also form teratomas; therefore, it is imperative that any potential therapeutic-derived cell not be tumorigenic. The multipotent mesenchymal progenitor cells we derived20 have not formed teratomas in any of the in vivo experiments performed thus far. This indicates that they have differentiated beyond the point of being tumorigenic but are still plastic enough to become multiple types of cells similar to an adult MSC. For cells to be of use clinically they will have to be reproducible on a large scale. Although we recognize the limitations of our microarray analysis for definitive exclamations regarding the uniformity of the derived cells, the generated data suggest that the differentiation protocol can reproducibly generate cell populations with relatively similar gene expression profiles and differentiation capabilities.

One of the initial events in microvascular assembly is the recruitment of mesenchymal cells to the nascent vessel wall, which has been shown to be dependent upon the PDGF-BB/PDGFR-β signaling axis.5 Therefore, one would expect a mural progenitor cell to be responsive to PDGF-BB signaling. hES-MC express PDGFR-β, which is phosphorylated in a dose-dependent fashion. They are also able to move toward paracrine signals produced by ECs and PDGF-BB specifically. Interestingly, when hES-MC are exposed to PDGF-BB or FBS, contractile protein expression is repressed, a functional response demonstrated by SMC.32

In our original report of hES-MC derivation,20 we demonstrated their capacity to express αSMA in the presence of TGFβ1, though at relatively low levels throughout the population. Bone marrow-derived MSC treated with TGFβ1 have been shown to express αSMA and other contractile proteins in the presence of serum.33 However, serum was shown to have an inhibitory effect on αSMA induction in SMC,34,35 whereas nonmuscle fibroblasts will express αSMA in the presence of serum.36–38 When hES-MC were cultured in SFM and then exposed to TGFβ1, they were robustly induced to express αSMA and other contractile proteins (SM22α, SM-MHC, and calponin). Although the mechanisms regulating serum inhibition in hES-MC are unclear, their response to these culture conditions suggests a hypothesis that they have differentiated along a muscle versus a nonmuscle phenotype.

TGFβ and its receptors have long been associated with vascular development39,40 and regulation of the contractile phenotype in PCs.12 Sinha et al. demonstrated the need for TGFβRII for derivation of SMC-like cells from mESC in an embryoid body model.41 Here we have shown that multipotent mesenchymal cells derived from hESC can be induced to express multiple contractile proteins. It is important to know if in vitro-derived cells function using the same signaling mechanisms as terminally differentiated cells. Our data demonstrate clearly by both pharmacological and molecular techniques that hES-MC are induced to express multiple contractile proteins through the TGFβ1/Alk5 signaling axis. αSMA is a commonly used marker for SMC identification, but it is not specific, being identified in cardiomyocytes,42 skeletal muscle,43 and myofibroblasts.44 The contractile proteins SM22α, SM-MHC, and calponin are thought to be more specifically associated with SMC.3 Here we show that hES-MC express not only αSMA, but also SM22α, SM-MHC, and calponin in the presence of TGFβ1 mediated through Alk5. This suggests that hES-MC posses the necessary signaling machinery to control gene regulation potentially enabling hES-MC to act as a functional perivascular mural cell.

Here we show that HUVEC networks grown without supporting mesenchymal cells do not persist even in the presence of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), but the addition of hES-MC had a stabilizing effect. When quantifying the networks, the regression of HUVEC alone resulted in a greater number of total vessel-like structures compared to coculture. Only after comparing the average network length did a quantitative difference emerge, indicating that although the total calculated network length for both conditions was the same, the average lengths and the number of branch points per network were two fold higher with the addition of hES-MC. This clearly shows that hES-MC have a stabilizing effect on HUVEC networks, a characteristic not shared by all mesenchymal cells.45 Two possible mechanisms may be controlling this process: (i) direct cell–cell contact or (ii) paracrine regulation. Direct contact between endothelial cells and various mesenchymal cells has been shown to stabilize networks.12 hES-MC make direct contact with HUVEC and though the precise mechanisms of communication are unknown, it is likely this plays a role in HUVEC stabilization. PDGF-BB is known to play a role in mesenchymal cell recruitment,5 whereas TGFβ1 functions to stabilize newly formed endothelial tubes.12 In our system it is currently unknown precisely what paracrine events may be regulating network stabilization. Although we detect direct contact of hES-MC with HUVEC networks, in general we have not seen typical perivascular integration as seen in ultrastructural studies.46 Medium supplementation with VEGF and bFGF, both endothelial mitogens, is insufficient to maintain network formation of HUVEC in the absence of hES-MC. However, the proliferative effects of VEGF and bFGF may be stimulating signaling events that would cause hES-MC to remain in a nonintegrated position. Another factor may be the lack of perfusion. Reports of EC and SMC/PC/MSC in vitro coculture describe an interaction between the two cell types but have not demonstrated classical integration.12 The angiogenic sprout is filled with fluid, thus keeping the lumen patent.47 It is unclear how fluid pressure or flow regulates angiogenic microvessel maturation, but the lack thereof in our in vitro system may inhibit hES-MC integration into the HUVEC network.48

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that multipotent hES-MC are not tumorigenic and possess the capacity to become myogenic in response to TGFβ1. They also function to stabilize endothelial networks in 3D collagen matrix. This suggests that the derived cells may be mesenchymal precursors that can model PC recruitment and microvascular stabilization.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Leonard Anderson of the Morehouse School of Medicine Microarray Core, Chris Worth of the Louisville Brown Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core Facility, and Dr. Nigel Cooper of the University of Louisville Microarray Facility. Funding support was provided by University of Louisville School of Medicine (N.L.B.), NCRR IDeA Awards INBRE-P20 RR016481 and COBRE-P20RR018733, the James Graham Brown Foundation (Y.C.), and NIH EB007556 (J.B.H.).

Disclosure Statement

Authors Boyd and Stice have patent application on hESC-derived mesenchymal cells.

References

- 1.Langer R. Tissue engineering: perspectives, challenges, and future directions. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drake C.J. Embryonic and adult vasculogenesis. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2003;69:73. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hungerford J.E. Little C.D. Developmental biology of the vascular smooth muscle cell: building a multilayered vessel wall. J Vasc Res. 1999;36:2. doi: 10.1159/000025622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz-Flores L. Gutierrez R. Madrid J.F. Varela H. Valladares F. Acosta E., et al. Pericytes. Morphofunction, interactions and pathology in a quiescent and activated mesenchymal cell niche. Histol Histopathol. 2009;24:909. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellstrom M. Kalen M. Lindahl P. Abramsson A. Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:3047. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes S. Chan-Ling T. Characterization of smooth muscle cell and pericyte differentiation in the rat retina in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2795. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan-Ling T. Page M.P. Gardiner T. Baxter L. Rosinova E. Hughes S. Desmin ensheathment ratio as an indicator of vessel stability: evidence in normal development and in retinopathy of prematurity. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1301. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63389-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armulik A. Abramsson A. Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res. 2005;97:512. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dore-Duffy P. Pericytes: pluripotent cells of the blood brain barrier. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1581. doi: 10.2174/138161208784705469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orlidge A. D'Amore P.A. Inhibition of capillary endothelial cell growth by pericytes and smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:1455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.3.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dore-Duffy P. Balabanov R. Beaumont T. Katar M. The CNS pericyte response to low oxygen: early synthesis of cyclopentenone prostaglandins of the J-series. Microvasc Res. 2005;69:79. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirschi K.K. Rohovsky S.A. D'Amore P.A. PDGF, TGF-beta, and heterotypic cell-cell interactions mediate endothelial cell-induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Risau W. Sariola H. Zerwes H.G. Sasse J. Ekblom P. Kemler R., et al. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis in embryonic-stem-cell-derived embryoid bodies. Development. 1988;102:471. doi: 10.1242/dev.102.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamashita J. Itoh H. Hirashima M. Ogawa M. Nishikawa S. Yurugi T., et al. Flk1-positive cells derived from embryonic stem cells serve as vascular progenitors. Nature. 2000;408:92. doi: 10.1038/35040568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galmiche M.C. Koteliansky V.E. Briere J. Herve P. Charbord P. Stromal cells from human long-term marrow cultures are mesenchymal cells that differentiate following a vascular smooth muscle differentiation pathway. Blood. 1993;82:66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arakawa E. Hasegawa K. Yanai N. Obinata M. Matsuda Y. A mouse bone marrow stromal cell line, TBR-B, shows inducible expression of smooth muscle-specific genes. FEBS Lett. 2000;481:193. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01995-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balabanov R. Beaumont T. Dore-Duffy P. Role of central nervous system microvascular pericytes in activation of antigen-primed splenic T-lymphocytes. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:578. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990301)55:5<578::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrington-Rock C. Crofts N.J. Doherty M.J. Ashton B.A. Griffin-Jones C. Canfield A.E. Chondrogenic and adipogenic potential of microvascular pericytes. Circulation. 2004;110:2226. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144457.55518.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crisan M. Yap S. Casteilla L. Chen C.W. Corselli M. Park T.S., et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyd N.L. Robbins K.R. Dhara S.K. West F.D. Stice S.L. Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesoderm-like epithelium transitions to mesenchymal progenitor cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1897. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz-Flores L. Gutierrez R. Lopez-Alonso A. Gonzalez R. Varela H. Pericytes as a supplementary source of osteoblasts in periosteal osteogenesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Libby P. O'Brien K.V. Culture of quiescent arterial smooth muscle cells in a defined serum-free medium. J Cell Physiol. 1983;115:217. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041150217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakin A.V. Rinehart C. Tomlinson A.K. Arteaga C.L. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for TGFbeta-mediated fibroblastic transdifferentiation and cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3193. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.15.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitamura T. Koshino Y. Shibata F. Oki T. Nakajima H. Nosaka T., et al. Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer and expression cloning: powerful tools in functional genomics. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnan L. Underwood C.J. Maas S. Ellis B.J. Kode T.C. Hoying J.B., et al. Effect of mechanical boundary conditions on orientation of angiogenic microvessels. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:324. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warner R.M. Applied Statistics: From Bivariate Through Multivariate Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication; 2007. Comparing group means using the independetn samples t test; pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomson J.A. Itskovitz-Eldor J. Shapiro S.S. Waknitz M.A. Swiergiel J.J. Marshall V.S., et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soriano P. Abnormal kidney development and hematological disorders in PDGF beta-receptor mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1888. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leveen P. Pekny M. Gebre-Medhin S. Swolin B. Larsson E. Betsholtz C. Mice deficient for PDGF B show renal, cardiovascular, and hematological abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1875. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grygielko E.T. Martin W.M. Tweed C. Thornton P. Harling J. Brooks D.P., et al. Inhibition of gene markers of fibrosis with a novel inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor kinase in puromycin-induced nephritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:943. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.082099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawabata M. Imamura T. Miyazono K. Engel M.E. Moses H.L. Interaction of the transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor with farnesyl-protein transferase-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blank R.S. Thompson M.M. Owens G.K. Cell cycle versus density dependence of smooth muscle alpha actin expression in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:299. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong Z. Niklason L.E. Small-diameter human vessel wall engineered from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) FASEB J. 2008;22:1635. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-087924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corjay M.H. Thompson M.M. Lynch K.R. Owens G.K. Differential effect of platelet-derived growth factor- versus serum-induced growth on smooth muscle alpha-actin and nonmuscle beta-actin mRNA expression in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimizu R.T. Blank R.S. Jervis R. Lawrenz-Smith S.C. Owens G.K. The smooth muscle alpha-actin gene promoter is differentially regulated in smooth muscle versus non-smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foster D.N. Min B. Foster L.K. Stoflet E.S. Sun S. Getz M.J., et al. Positive and negative cis-acting regulatory elements mediate expression of the mouse vascular smooth muscle alpha-actin gene. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoflet E.S. Schmidt L.J. Elder P.K. Korf G.M. Foster D.N. Strauch A.R., et al. Activation of a muscle-specific actin gene promoter in serum-stimulated fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1073. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.10.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim J.H. Bushel P.R. Kumar C.C. Smooth muscle alpha-actin promoter activity is induced by serum stimulation of fibroblast cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;190:1115. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dickson M.C. Martin J.S. Cousins F.M. Kulkarni A.B. Karlsson S. Akhurst R.J. Defective haematopoiesis and vasculogenesis in transforming growth factor-beta 1 knock out mice. Development. 1995;121:1845. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larsson J. Goumans M.J. Sjostrand L.J. van Rooijen M.A. Ward D. Leveen P., et al. Abnormal angiogenesis but intact hematopoietic potential in TGF-beta type I receptor-deficient mice. EMBO J. 2001;20:1663. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sinha S. Hoofnagle M.H. Kingston P.A. McCanna M.E. Owens G.K. Transforming growth factor-beta1 signaling contributes to development of smooth muscle cells from embryonic stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1560. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00221.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruzicka D.L. Schwartz R.J. Sequential activation of alpha-actin genes during avian cardiogenesis: vascular smooth muscle alpha-actin gene transcripts mark the onset of cardiomyocyte differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2575. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodcock-Mitchell J. Mitchell J.J. Low R.B. Kieny M. Sengel P. Rubbia L., et al. Alpha-smooth muscle actin is transiently expressed in embryonic rat cardiac and skeletal muscles. Differentiation. 1988;39:161. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1988.tb00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serini G. Gabbiani G. Modulation of alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in fibroblasts by transforming growth factor-beta isoforms: an in vivo and in vitro study. Wound Repair Regen. 1996;4:278. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1996.40217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montesano R. Pepper M.S. Orci L. Paracrine induction of angiogenesis in vitro by Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 1993;105(Pt 4):1013. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.4.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sims D.E. The pericyte—a review. Tissue Cell. 1986;18:153. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(86)90026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerhardt H. Golding M. Fruttiger M. Ruhrberg C. Lundkvist A. Abramsson A., et al. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:1163. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nunes S.S. Greer K.A. Stiening C.M. Chen H.Y. Kidd K.R. Schwartz M.A., et al. Implanted microvessels progress through distinct neovascularization phenotypes. Microvasc Res. 2009;79:10. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]