Abstract

Background:

Veneer restorations provide a valid conservative alternative to complete coverage as they avoid aggressive dental preparation; thus, maintaining tooth structure. Initially, laminates were placed on the unprepared tooth surface. Although there is as yet no consensus as to whether or not teeth should be prepared for laminate veneers, currently, more conservative preparations have been advocated. Because of their esthetic appeal, biocompatibility and adherence to the physiology of minimal-invasive dentistry, porcelain laminate veneers have now become a restoration of choice. Currently, there is a lack of clinical consensus regarding the type of design preferred for laminates. Widely varying survival rates and methods for its estimation have been reported for porcelain veneers over approximately 2–10 years. Relatively few studies have been reported in the literature that use survival estimates, which allow for valid study comparisons between the types of preparation designs used. No survival analysis has been undertaken for the designs used. The purpose of this article is to attempt to review the survival rates of veneers based on different incisal preparation designs from both clinical and non-clinical studies.

Aims and Objectives:

The purpose of this study is to review both clinical and non-clinical studies to determine the survival rates of veneers based on different incisal preparation designs. A further objective of the study is to understand which is the most successful design in terms of preparation.

Materials and Methods

This study evaluated the existing literature – survival rates of veneers based on incisal preparation designs. The search strategy involved MEDLINE, BITTORRENT and other databases.

Statistical Analysis

Data were tabulated. Because of variability in the follow-up period in different studies, the follow-up period was extrapolated to 10 years in common for all of them. Accordingly, the failure rate was then estimated and The weighted mean was computed.

Conclusions

The study found that the window preparation was of the most conservative type. Incisal coverage was better than no incisal coverage and, in incisal coverage, two predictable designs – incisal overlap and butt were reported. In butt preparation, no long-term follow-up studies have been performed as yet. In general, incisal overlap was preferred for healthy normal tooth with sufficient thickness and incisal butt preparation was preferred for worn tooth and fractured teeth.

Keywords: Feather edge, preparation, survival rates, veneers, window Articles selected were both clinical and non-clinical studies

INTRODUCTION

Advancements in the field of adhesive dentistry and porcelain technology have broadened the use of porcelain veneer restorations significantly. These original fragile restorations, introduced by Dr. Charles Pincuss in 1938, have undergone considerable improvement and refinement over the past few decades, and have now matured into a predictable restorative concept in terms of longevity, periodontal response and patient satisfaction.[1]

These veneer restorations provide a valid conservative alternative to complete coverage as they avoid aggressive dental preparation; thus, maintaining tooth structure.[2] Initially, laminates where placed on the unprepared tooth surface. Although there is as yet no consensus as to whether or not teeth should be prepared for laminate veneers, currently, more conservative preparations have been advocated.[3] Because of their esthetic appeal, biocompatibility and adherence to the physiology of minimal-invasive dentistry, porcelain laminate veneers have now become a restoration of choice to correct tooth forms, tooth position, close diastemas, restore tooth fracture, erosions or mask tooth discolorations.[4]

Traditionally, a chamfer finish line is generally placed at or close to the gingival margin and the enamel is reduced by 0.3–0.5 mm, which enables the maintenance in enamel strong bonding and, at the same time, sufficient thickness of porcelain is maintained.[5,6] However, controversy exists as whether to cover the incisal edge or not in these preparations.

As a result, basically four types of incisal tooth preparations have been advocated for veneers[7] :

Window (intraenamel), leaving an intact incisal enamel edge.

Feather edge, leaving an incisal edge in enamel and porcelain. Here, the veneer is taken up to the height of the incisal edge but the edge is not reduced.

Beveled with incisal edge, entirely in porcelain. The bucco-palatal bevel is prepared across the full width of the preparation and there is some reduction of the incisal length of the tooth and overlapped with the porcelain extended into the palatal aspect of the preparation as a chamfer. Proximally, contact areas should also be maintained in case of minimum preparations.

Incisal butt preparation is advocated for better esthetics, stress distribution and positive seating.

The dynamics of an existing clinical situation broadly influence the type of veneer design, the determining factors usually being requisite for enhanced esthetics (highly translucent incisal edge), the existing condition of the incisal edge, the type of extension of the restoration to be made and the stress distribution expected at the veneer tooth interface.[8]

Further, more severe defects in the anterior dentition require more extended preparation. In cases of severe discolorations, fractured incisal angles, facial or proximal caries or pre-existing restorations that need to be replaced, an alternative preparation design must be attempted.[9] In such cases, a deeper preparation with a proximal and palatal extension is necessary to improve function and esthetics.

Currently, there is a lack of clinical consensus regarding the type of design preferred for laminates. Widely varying survival rates (48–100%) and methods for estimating it have been reported for porcelain veneers over approximately 2-10 years.[8]

Relatively few studies have been reported in the literature that use survival estimates, which allow for valid study comparisons between the types of preparation designs used. No survival analysis has been undertaken for the designs used.[8]

The purpose of this article is an attempt to review the survival rates of veneers based on different preparation designs from both clinical and non-clinical studies.

Aims and objectives

The purpose of this study is to review both clinical and non-clinical studies to determine the survival rates of veneers based on different preparation designs. A further objective of the study is to understand which is the most successful design in terms of preparation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study evaluated the existing literature – survival rates of veneers based on preparation designs. The search strategy involved MEDLINE, BITTORRENT and other databases. Keywords used were veneers and survival rates. Articles selected were both clinical and non-clinical studies. Aspects of the prep were quantified and analyzed from the matter distilled from a review of these articles.

Statistical analysis

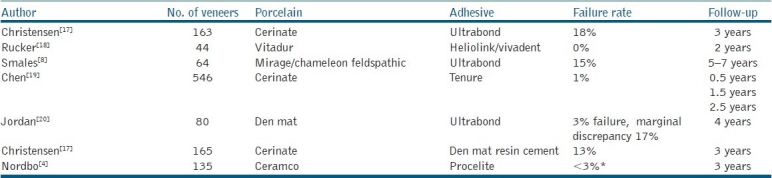

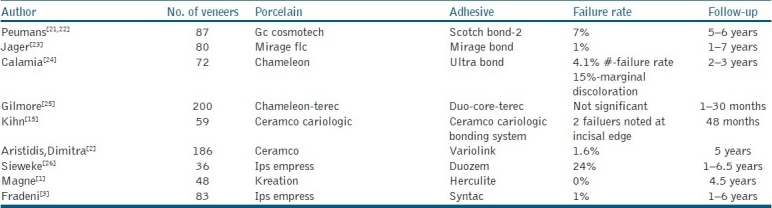

Data were tabulated. Because of variability in the follow-up period in different studies, the follow-up period was extrapolated to 10 years in common foe all the studies. Accordingly, the failure rate was then estimated and the weighted mean was computed [Tables1–6, Figure 1].

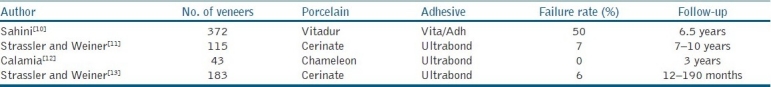

Table 1.

Percentage of failure rates of laminates with no preparation

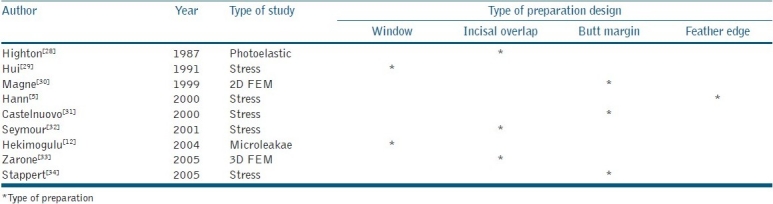

Table 6.

Percentage of failure rates of laminates with analysis of data from non-clinical studies

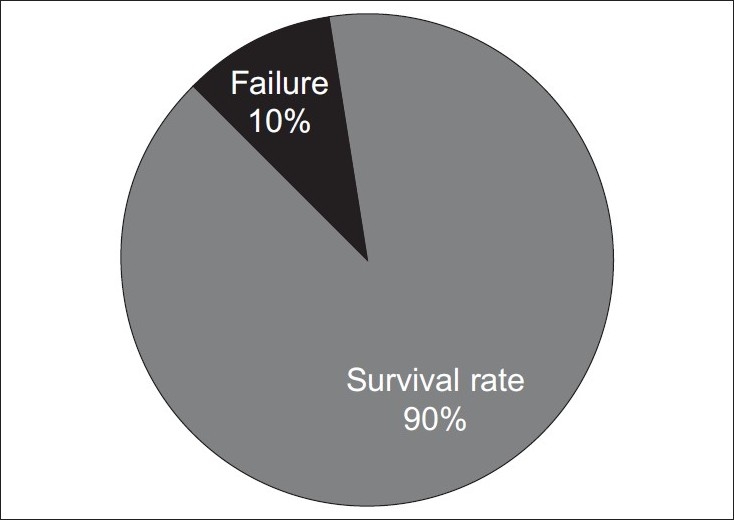

Figure 1.

Survival rate and failure rate for incisal bevel preparation veneers. Common follow-up period of 10 years. The total number of veneers was 114

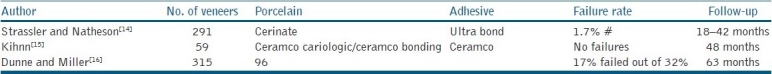

Table 2.

Percentage of failure rates of laminates with window preparation

Table 3.

Percentage of failure rates of laminates with feather edge

Table 4.

Percentage of failure rates of laminates with incisal overlap chamfer

Table 5.

Percentage of failure rates of laminates with incisal bevel

DISCUSSION

The demand for treatment of unesthetic teeth is steadily growing. Accordingly, several treatment options have been proposed to restore the esthetic appearance of teeth, like full-coverage crowns and bonding with composites. While full-coverage crowns is highly invasive and may have an adverse effect on the pulp or periodontal tissue, bonding with composites on the other hand, even though less invasive, continues to remain susceptible to discoloration, wear and marginal fractures.[6] The search for a better alternative led to the development of porcelain laminate veneers. These ultrathin ceramic restorations were reported to provide a superior alternative to direct composite resin bonding for esthetic modification of teeth.[27] Porcelain laminate veneers are now an accepted treatment modality. These restorations offer a successful treatment that preserves tooth structure while providing excellent esthetic results and patient acceptance.[3,6,18,21,27,35] The advantages of these restorations are numerous and result from the combined advantages of resins and porcelain.

Although the success of these restorations is now well established, the survival of these restorations is influenced by different variables.

Various studies on the survival rate of these restorations exists. However, very few studies have actually focused on the influence of preparation designs on the success rates of these restorations. The current study makes an attempt to review and establish a relationship between the survival rate of these veneer restorations and preparation deigns from the existing literature.

Traditionally, these veneer restorations were prepared on unprepared tooth surface. However, currently, conservative intraenamel preparations of 0.3–0.5 mm with a chamfer gingivally are recommended. The difference in preparation design comes with respect to the incisal edge, with some clinicians advocating the preservation of incisal edge while others prefer to overlap the incisal edge.[4]

Thus, basically, regarding the laminate preparation, four basic types of preparation have been described, namely the window or intraenamel preparation, the feathered edge preparation, incisal overlap and incisal bevel.

The veneer preparation design with no incisal coverage is basically of three types:

Window preparation

Feather edge

No preparation

Analysis of the data obtained from clinical and non-clinical studies revealed the following.

Window preparation

This preparation was suggested by Grabber and others, which basically comprises of a design where the veneer is taken close to but not to the incisal edge.

It is claimed that the window type of preparation may withstand the highest load until failure.

In this study, the window-style preparation showed a survival rate of almost 89%. Khin[15] reported no failures with this type of preparation. Hui[29] showed that, using a two-dimensional photoelastic stress analysis, this design when prepared entirely in enamel withstood axial stress most favourably. Further, it has been concluded that where strength is an important requisite, the most conservative type of veneer, namely the window preparation, was the design of choice. An 11% failure rate was observed with this design in this study. The common modes of failure seen were interfacial staining (2%), debonding and minor failures.[15] This preparation modality may produce a weak enamel margin of poorly supported enamel prisms that may undergo chipping on mandibular protrusion. A majority of the failures occurred when the veneers where placed on existing restorations. However, microleakage of the window design at the incisal margin was less than that in the overlap design.

Feather edge design/minimal preparation design/facial preparation design

Here, the veneer is taken up to the height of the incisal edge but the edge is not reduced, leaving an incisal edge in enamel and porcelain.

Statistical analysis of the data obtained from clinical and non-clinical studies showed a survival rate of 75% for this type of design.

Christensen,[17] in his study, evaluated this design over a period of 3 years and found an excellent marginal fit. He noticed some discoloration at the end of 3 years and attributed it to the low degradation of cement. Thirteen percent of the cases had breakage over 3 years. It was observed that the incisal area was the major location for porcelain fracture. In lieu of this, Christensen recommends the modification of the incisal area to reduce the fracture at the incisal area, covering incisal with a butt joint, but cautions that there are higher chances of wear opposing the tooth.

Smales,[8] on the other hand, in his observation showed a survival rate of 85.5% but, in his study, this rate was less compared with those that had incisal coverage (almost 96%). Bulk porcelain fractures were observed in this study, where the incisal coverage was not performed. It was concluded that a trend for better long-term survival was noticed for teeth with incisal coverage Nordbo,[4] on the other hand, analyzed that minimal porcelain restoration with no incisal overlapping was conservative, predictable and successful. Wrap-over method should be avoided in young teeth as it was less conservative. Further, he cited that the bond strength of etched porcelain is 14–28 mpa, which surpasses the cohesive strength of porcelain. Further, porcelain should be prevented from direct stress. In clinical situations with normal overbite, this design is to be preferred.

Jordon,[20] in his study, showed a high survival or retention rate of 97% when veneers were seated with the feather edge design. He attributes this excellent survival rate to a double micromechanical lock that is between the etched tooth surface and the etched porcelain surface. Compared with window preparation, the feather edge preparation will not produce a weak margin of unsupported enamel prisms that may undergo chipping on mandibular protrusion. In the window prep, the adhesive cement will be bonded to the longitudinal aspects of the incisal enamel prisms, leading to a weaker bond. However, he cautions that there may be wear of the luting agent at the incisal margin, to the order of 100 mm with the feather edge design.

Meijering,[36] In his study of the feather edge design, showed a survival rate of 75%. The common modes of failure noticed were chipping of incisal porcelain, chipping of incisal enamel and incisal wear.

No preparation

Here, the veneer is directly bonded on to the unprepared tooth surface.

Statistical analysis of the data available revealed a high failure rate of 56% with this design. The common modes of failure seen were debonding and fracture. Lack of tooth preparation was one of the major factors for high failure rates of 56%.[10]

The reason attributed for this was that stress concentration is less intense within restoration fitted to the prepared teeth.[28,37] Further, surface preparation increases the bond strength as it increases the surface area and removes the aprismatic layer that is resistant to acid etching. Also, preparing the tooth helps for a positive seat. Bonding allows restoration to act as an integral part of the tooth structure.

The intimate contact allows better stress distribution and prevents local overloading of brittle material. Factors that influence the bond may effect the long-term and short-term survival rates.[16]

Veneer preparation designs with incisal coverage

Although Meijering[36] found no difference between coverage and no incisal coverage, greater survival rate for incisal coverage (almost 96%) was noticed by Smales[8] compared with no incisal coverage (85%).

Rucker[18] found that better long-term survival rates was noticed for teeth with incisal coverage.

Incisal coverage designs are of two types:

Incisal overlap.

Incisal bevel or butt joint.

Incisal overlap:Statistical analysis of the data revealed a high survival rate of 93% with this design. The good survival rate was attributed to better stress distribution.

Common modes of failure seen were failure of adhesive bond, increased marginal defects noticed in the palato-incisal area and higher % of microleakage noticed at the palato–incisal area.

Highton et al. found that with the incisal overlap design, during protrusive movement, a wider area of tooth structure is involved in stress distribution.[28]

Further, this design increases the mechanical resistance to fracture. In addition, it provides superior intrinsic resistance to porcelain.[28,30,33]

When compared with the window preparation, in terms of microleakage, the incisal overlap design showed more microleakage. This can be attributed to the shrinkage of porcelain by the firing process – veneers may contract from the margins leading to marginal gap formation at the linguoincisal edge.[3]

Incisal butt: No long-term studies are present with respect to this design. Statistical analysis of the data available showed a survival rate of 90%.

This design is advocated for better esthetics, stress distribution and positive seating. Stress analysis of load distribution studies showed that the butt design showed the strongest fracture resistance.[1,30,31]

When compared with the incisal overlap design, it was seen that light chamfer exhibits higher tensile stress because it extends closer to the palatal concavity. This is more problematic in a deeper concavity extending to the incisal edge as it is seen in severely worn teeth. Therefore, in such cases, a butt margin is preferred.

In the presence of maximum tooth structure, the stress pattern on the palatal surface is barely influenced by the type of finish line. Here, butt or mini chamfer may be preferred. Chamfer extending into the concavity is not recommended.

Elevated stress is generated in the palatal concavity during functional loading and, therefore, mini chamfer should be replaced by a simpler design such as butt.

This provides the margin with a strong bulk of porcelain.

Crack propensity of porcelain veneers can be minimized by sufficient thickness of the ceramic material combined with a minimal thickness of composite.[30]

The advantages of incisal butt preparation are that a flat incisal wall and incisal reduction give desirable character of the veneer at the incisal third.

Further, there is preservation of the peripheral enamel layer. The butt joint design provides a favourable ceramic/luting ratio and reduces the risk of post-insertion cracks due to shrinkage.[19,38,39]

The clinical advantages of such a design are:

With incisal butt, joint results in stronger restoration.

Simplified tooth preparation tech.

Eliminates the risk of thin, unsupported palatal ceramic ledges.

Impressions produce cast with clear finish lines.

CONCLUSIONS

The authors made the following conclusions based on the results of the following study:

Window preparation the most conservative type.

Incisal coverage better than no incisal coverage.

In incisal coverage, two predictable designs exist, incisal overlap and butt

In butt preparation, no long-term follow-up studies have been performed as yet.

Incisal overlap preferred for healthy normal tooth with sufficient thickness.

Incisal butt preparation preferred for worn tooth and fractured teeth.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Magne P, Perroud R, Hodges JS, Belser UC. Clinical performance of novel design porcelain veneers for the recovery for the recovery of coronal volume and length. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2000;20:440–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aristidis G, Dimitra B. Five year clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers. Quintessence Int. 2002;33:185–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fradeani M. Six year follow-up with empress veneers. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1998;18:217–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordbo H. Clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers without incisal overlapping: 3-year results. J Dent. 1994;22:342–5. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(94)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahn P, Gustav M, Hellwig E. An in vitro assessment of the strength of porcelain veneers dependent on tooth preparation. J Oral Rehabil. 2000;27:1024–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2000.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G. Porcelain veneers: A review of literature. J Dent. 2000;28:163–77. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(99)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walls AW. The use of adhesively retained all porcelain veneers during the management of fractured and worn anterior teeth Part 2: Clinical results after ayear follow-up. Br Dent J. 1995;178:337–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smales RJ, Etemadi S. Long term survival of porcelain laminate veneers using two preparation designs: A retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2004;17:323–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Sherif M, Jacobi R. The ceramic reverse three quarter crown for anterior teeth preparation design. J Prosthet Dent. 1998;61:4–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(89)90097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaini FJ, Shortall AC, Marquis PM. Clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers. A retrospective evaluation over a period of 6.5 years. J Oral Rehabil. 1997;24:553–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.1997.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strassler HE, Weiner S. Seven to ten year evaluation of etched porcelain veneers (abstract 1316) J Dent Res. 1995;74:176. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hekimoglu C, Anil N, Yalçin E. A microleakage study of ceramic laminate veneers by autoradiography. J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31:265–9. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-182X.2003.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strassler HE, Weiner S. Long term clinical evaluation of etched porcelain veneers (abstract 194) J Dent Res. 2001;80:60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strassler HE, Nathanson D. Clinical evaluation of etched porcelain veneers over a period of 18 to 42 months. J Esthet Dent. 1989;1:21–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1989.tb01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khin P, Barnes D. The clinical longevity of porcelain veneers: A 48-month clinical evaluation. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:747–52. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunne SM, Millar BJ. A longitudinal study of the clinical performance of porcelain veneers. Br Dent J. 1993;175:317–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen GJ, Christensen RP. Clinical observations of porcelain veneers: A three-year report. J Esthet Dent. 1991;3:174–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1991.tb00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rucker LM, Richter W, MacEntee M, Richardson A. Porcelain and resin veneers clinically evaluated 2- year results. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;121:594–6. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1990.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen JH, Shi CX, Wang M, Zhao SJ, Wang H. Clinical evaluation of 546 tetracycline-stained teeth treated with porcelain laminate veneers. J Dent. 2005;33:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordan RE, Suzuki M, Senda A. Clinical evaluation of porcelain laminate veneers: A four year recall report. J Esthet Dent. 1989;1:126–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1989.tb00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B, Lambrechts P, Vuylsteke-Wauters M, Vanherle G. Five year clinical performance of porcelain veneers. Quintessence Int. 1998;29:211–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peumans M, De Munck J, Fieuws S, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G, Van Meerbeek B. A prospective ten year clinical trial of porcelain veneers. J Adhes Dent. 2004;6:65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jager K, Stern M, Wirz J. Laminates - Ready for the practice? Quintessenz Q146. 1995:1221–1230. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calamia JR. Clinical evaluation of etched porcelain veneers. Am J Dent. 1989;121:594–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilmour AS, Stone DC. Porcelain laminate veneers: A clinical success? Dent Update. 1993;20:171–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sieweke M, Salomon-Sieweke U, Zöfel P, Stachniss V. Longevity of oroincisal ceramic veneers on canines: A retrospective study. J Adhes Dent. 2000;2:229–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman MJ. A 15-year review of porcelain veneer failure- a clinicians observations. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1998;19:625–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Highton R, Caputo AA, Mátyás J. A photo-elastic study of stresses on porcelain laminate preparations. J Prosthet Dent. 1987;58:157–61. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(87)90168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hui KK, Williams B, Davis EH, Holt RD. A comparative assessment of the strengths of porcelain veneers for incisor teeth dependent on their design characteristics. Br Dent J. 1991;171:51–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magne P, Douglas WH. Design optimization and evolution of bonded ceramics for anterior dentition: Finite Element Analysis. Quintessence Int. 1999;30:661–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castelnuovo J, Tjan AH, Phillips K, Nicholls JI, Kois JC. Fracture load and mode of failure of ceramic veneers with different preparations. ;83:171-80. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;83:171–80. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(00)80009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seymour KG, Cherukara GP, Samarawickrama DY. Stresses within porcelain veneers and the composite lute using different preparation designs. J Prosthodont. 2001;10:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849x.2001.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zarone F, Apicella D, Sorrentino R, Ferro V, Aversa R, Apicella A. Influence of tooth preparation design on the stress distribution in maxillary central incisors restored by means of alumina porcelain veneers: A 3d-finite element analysis. Dent Mater. 2005;21:1178–88. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stappert CF, Stathopoulou N, Gerds T, Strub JR. Survival rate and fracture strength of maxillary incisors, restored with different kinds of full veneers. J Oral Rehabil. 2005;32:266–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dumfahart H, Schaffer H. Porcelain laminate veneers. A retrospective evaluation after 1-10 years of service: Part 2-clinical results- Int J Prosthodont. 2000;13:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meijering AC, Creugers NH, Roeters FJ, Mulder J. Survival of three types of veneer restorations in a clinical trial: A 2.5 year interim evaluation. J Dent. 1998;26:563–8. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horn HR. Porcelain laminate veneers bonded to etched enamel. Dent Clin North Am. 1983;27:671–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magne P, Belser U. Bonded porcelain Restorations in the Anterior Dentition: A Biomimetic Approach. Chicago, IL: Quintessence Publishing Co Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stappert CF, Ozden U, Gerds T, Strub JR. Longevity and failure load of ceramic veneers with different preparation designs after exposure to masticatory simulation. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;94:132–9. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]