Abstract

Aim:

This study evaluated the effect of thermal and mechanical loading on marginal adaptation and microtensile bond strength in total-etch versus self-etch adhesive systems in caries-affected dentin.

Materials and Methods:

Forty class II cavities were prepared on extracted proximally carious human mandibular first molars and were divided into two groups: Group I — self-etch adhesive system restorations and Group II — total-etch adhesive system restorations. Group I and II were further divided into sub-groups A (Without thermal and mechanical loading) and B (With thermal and mechanical loading of 5000 cycles, 5 ± 2°C to 55 ± 2°C, dwell time 30 seconds, and 150,000 cycles at 60N). The gingival margin of the proximal box was evaluated at 200X magnification for marginal adaptation in a low vacuum scanning electron microscope. The restorations were sectioned, perpendicular to the bonded surface, into 0.8 mm thick slabs. All the specimens were subjected to microtensile bond strength testing. The marginal adaptation was analyzed using descriptive studies, and the bond strength data was analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test.

Results and Conclusions:

The total-etch system performed better under thermomechanical loading.

Keywords: Marginal adaptation, mechanical loading, microtensile bond strength, self-etch adhesive, thermocycling

INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, self-etch adhesive systems have become increasingly popular. They combine the etchant and primer in one system, which reduces the application time and technique-related sensitivity.[1–3] Resin infiltration of the self-etch adhesives occurs concomitantly with demineralization of the dentin.[3] Theoretically, the depth of demineralization and the depth of resin infiltration will be of the same dimension, as both processes occur simultaneously, but a recent study showed a partially demineralized and uninfiltrated dentin zone beneath the hybrid layer.[4] Despite the simplicity and improved user-friendliness of one-step, self-etch adhesives, they have been shown to exhibit guarded laboratory and clinical performance as compared to that of multi-step adhesives.[2,4]

The primary aim of minimally invasive dentistry is to conserve as much tooth structure as possible. During the excavation of carious dentin, the emphasis is to remove only the outer layer of the highly infected, denatured caries-infected dentin, which preserves the inner layer of intact, bacteria-free remineralizable caries-affected dentin, and prevents disease progression.[5,6] With the advent of newer hydrophilic self-etch and total-etch adhesives, it may be possible to bond to and seal vital caries-affected dentin and isolate residual bacteria from any substrate that may be present in the oral fluids. This makes the bacteria to become dormant and allows dentinogenesis, thus, protecting the pulp.[7]

The intrinsic weakness of caries-affected and caries-infected dentin may not be a clinical problem if there is normal dentin and / or enamel surrounding the excavated lesion that can provide high bond strengths with resin adhesives.[8] Bonding of hydrophilic self-etch and total-etch adhesives with caries-affected dentin poses several potential problems.[7,9,10] Caries-affected dentin is softer than normal dentin because it is partially demineralized.[10] Carious intertubular dentin exhibits a higher degree of porosity than sound intertubular dentin and contains mineral crystals in the tubules.[7,9] This may permit the deeper etching of intertubular dentin, but it prevents resin tag formation during bonding.

The restoration and the teeth are unavoidably subjected to thermal and mechanical stresses because of the consumption of different food materials at varied temperatures and masticatory stresses. These stresses may negatively affect the resin dentin bond.[11–14] The present study was undertaken to evaluate the effect of the thermal and mechanical stresses on the marginal adaptation and microtensile bond strength of the total-etch and self-etch adhesives on carious dentin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forty proximally carious human mandibular first molars, extracted due to periodontal reasons, were used in this study. The inclusion criteria were radiographic verification that the dentinal caries extended no further than the middle one-third of the dentin thickness, and some parts of the root remained in all the teeth. They were stored in 0.9% NaCl containing 0.05% sodium azide at 4°C, and used within one month following extraction. The roots of the samples were covered with an additional silicon, rubber-based impression material (to simulate a periodontal ligament) and were placed in an acrylic mold for better handling. Tooth preparation was done by a single operator to reduce inter-operator error.

Only in the Class II box, the cavities were prepared using round diamond points (FG-1/2, 1 Dentsply Co.), flat fissure diamond points (SF-41, ISO 190/010; Mani, Inc.), and tapered fissure burs (FG-271 Dentsply Co.) in an air-rotor hand piece (Super Torque, NSK), to expose a flat gingival surface of middle-to-deep dentin where the caries lesion was surrounded by normal dentin. The buccal-lingual width of the cavities was at least one-third of the intercuspal dimension, both occlusally and interproximally, and the gingival floor of the box only extended onto the dentin.

The entire flat surface was flooded with a Caries Detector solution to stain the lesion (Kuraray Medical Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Further reduction was performed with a #245 carbide plain fissure bur (Midwest, Des Plaines, IL, USA) according to the combined criteria of: hardness to a sharp excavator, visual examination, and staining with the Caries Detector solution. The discolored, harder dentin that stained pink was classified as the caries-affected dentin. The surrounding, yellow, hard dentin was classified as normal dentin.

Twenty samples (Group I) were treated with a self-etching adhesive Adper Easy One (3M ESPE), according to the manufacturer's instructions, with a saturated microbrush, and rubbed for 15 seconds. After the adhesive had been applied, the surfaces were dried with oil-free, compressed air, which was delivered at 0.2 MPa from 5 cm above the dentin surface using a three-way syringe. A clear plastic matrix strip was placed. A nanohybrid restorative resin (Z 350 3M ESPE) was placed in the cavity in 2 mm increments. Each increment was cured for 20 seconds by a QTH (Vivadent) light cure unit. Curing was done initially from the occlusal direction and then from the buccal and lingual directions. After curing, the matrix strip was removed and the gingival margins contoured with a composite polishing kit (Shofu Co., Japan).

Another twenty samples (Group II) were etched with 35% phosphoric acid gel for 15 seconds and rinsed for 15 seconds, leaving a visibly moist surface. Two consecutive coats of Single Bond (3M ESPE) adhesive were applied and light-cured for 10 seconds. The composite build-up was done as described earlier.

Groups I and II were further divided into subgroups A and B as follows:

Subgroup A — Without cyclic loading.

Subgroup B — Ten samples from each group were subjected to thermocycling (5000 cycles, 5 ± 2°C to 55 ± 2°C, dwell time 30 seconds) and cyclic loading of 150,000 cycles at 60N (simulating six months of oral masticatory stresses).

Preparation of specimens for evaluation of marginal adaptation in a scanning electron microscope

The gingival margins were cleaned with the help of 10% Orthophosphoric acid for 5 seconds to remove the debris over the margin. The samples were placed on standard half inch, pin-type aluminum stubs with the help of a carbon conductive double-sided adhesive tape (SPI Supplies®). The stubs were placed on the specimen chamber mounting table of the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) [LEO VP 435 (Carl-Zeiss NTS Gmbh, Oberochen, Germany)]. The gingival margin of the proximal box was evaluated at 200X magnification for marginal adaptation. The overall margin was investigated and the maximum marginal gap was measured. The margins were given scores on the basis of previously discussed criteria. The findings were recorded on a Microsoft Excel sheet [Microsoft Office Excel 2003].

Preparation of specimens and evaluation of microtensile bond strength (μTBS) measurement on a Universal Instron machine

Each tooth was vertically sectioned into two or three 0.8-mm-thick serial slabs by means of an Isomet saw, under water lubrication. The slabs were examined under a dissecting microscope to separate the slabs containing resin-bonded normal dentin from those that contained caries-affected dentin. This yielded about one slab each of bonded normal dentin (ND) and bonded caries-affected dentin (CAD) per tooth. The slabs were hand-trimmed into dumbbell-shaped specimens according to the technique for the microtensile bond test reported by Sano et al,. (1994), with the smallest dimension at the bonded interface representing the bonded tissue of interest. The trimmed specimens were mounted on a testing apparatus, the Universal Instron testing machine [Zwick testing instrument (Zwick GmbH and Co., postf. 4350, D-7900u/m, Germany)] with the help of a cyanoacrylate adhesive. The samples were stressed to failure at a crosshead speed of 0.5mm / minute. The tensile bond strength was calculated as the load at failure divided by the bonded area (1 mm2). The findings were recorded onto a Microsoft Excel sheet [Microsoft Office Excel 2003] for statistical evaluation, using the program SPSS 11.5 for Windows [SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA].

RESULTS

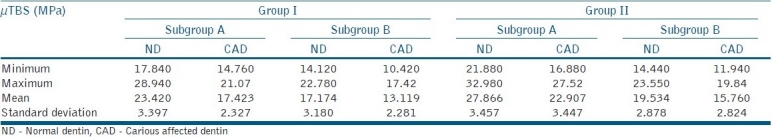

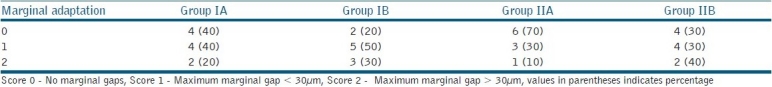

A descriptive analysis of microtensile bond strength was carried out for each of the variables of the four groups including the values for normal dentin and caries-affected dentin [Table 1]. The results were presented as Minimum, Maximum, and Mean ± Standard deviation. As the variables in this study followed the normal criteria, one way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used for comparing these variables among the four groups. The significance between the individual groups was calculated, using a Post Hoc ANOVA test. A descriptive analysis of the marginal adaptation values was done for each of the variables of the four groups [Table 2]. As the values for marginal adaptation were described as categorical variables, categorical two-way tables, using proportions, were used to compare the variables among the four groups.

Table 1.

Microtensile bond strength (μTBS) values

Table 2.

Proportion of samples showing marginal gaps / voids

DISCUSSION

In the past decade, various bonding systems have been introduced. These can be classified under two simplified approaches: ‘total-etch’ (also known as ‘etch and rinse’) and ‘self-etch’ systems.[2,9,14] The self-etch system was introduced to reduce technique sensitivity and it combined etching and priming in a single step.[14] Etching and bonding is a complex procedure and involves the infiltration of resin monomers into demineralized dentinal tubules and collagen fibers.[15–17] If there is a mismatch in the extent of demineralization and resin infiltration, the demineralized and uninfiltrated dentin zone becomes the weak point of the bond, owing to hydrolytic degradation of the collagen, over time.[17] Self-etch adhesives combine both hydrophilic and hydrophobic components, which present antagonistic properties. Therefore, single-step self-etching adhesives may form a hybrid layer with incomplete adhesive infiltration into the dentin substrate. The formed hybrid layer exhibits microscopic water-filled channels that allow water movement from the underlying dentin to the adhesive-composite areas, which may jeopardize the durability of the resin-dentin bonds.[18] This is clinically significant, because the thermal and mechanical stresses will degrade the resin-dentin bonds and enable access for microleakage.[4,11–14] If exposed collagen, which is not impregnated with resin infiltration, is thermally and mechanically stressed, hydrolysis may occur, leading to bond failure.

The resin-dentin interface is affected by various factors including, the cavity configuration (C-factor), dimensional changes of the restorative material (for example, polymerization shrinkage or thermal / hygroscopic expansion), thermal and mechanical stresses, and the type of adhesive system used.[11] In the present study, an attempt was made to produce an identical cavity size to avoid the effect of cavity configuration. However, the extent of caries determined the final shape of the cavity, which may have caused small variations. Different adhesive systems were bonded to one resin-based composite material so as to minimize any differences from the use of specific or nonspecific restorative systems.

The clinical objective of restorative dentistry is to preserve as much of the sound tooth structure as possible.[5,6,19] It is advisable to seal the caries-affected dentin, to allow new dentin formation and to cut off any nutrient supply to bacteria, to make them dormant.[7,20] However, it is a subject of debate of whether or not to leave residual bacteria underneath bonded restorations.[21] Also, caries-affected dentin poses certain problems with bonded restorations.[7,9,10] Dentinal tubules of caries-affected dentin have acid-resistant mineral casts, which hamper resin infiltration into the dentinal tubules.[22] This can lower resin retention, particularly when relatively mild-acting, self-etching primers are used. Also the long-term effects of incorporating dissolved hydroxyapatite crystals and residual smear layer remnants within the bond are still unknown.

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the effect of simulated clinical conditions on the microtensile bond strength and the marginal adaptation of bonding of a self-etch adhesive and a total-etch adhesive to carious-affected dentin and compare it with the effect on normal dentin. The μTBS of total-etch adhesives on normal dentin was higher than the self-etching adhesives (P = 0.00148). This was in accordance with some of the previous studies.[1,2,13,15,23–25] The value of μTBS decreased significantly in the carious dentin groups, both in the total-etch (17.423 MPa) and self-etch (22.907 MPa) techniques, although the total-etch technique showed a significantly higher bond strength (P = 0.000116). Thermal and mechanical loading had a detrimental effect on the resin-dentin interface and the value of μTBS significantly decreased in all the groups after simulation of the oral, thermal, and mechanical stresses. Overall, the samples restored with total-etch adhesives gave better μTBS values than those restored with the self-etch adhesives. In the present study, the resin-dentin margin was directly visualized under a low vaccum scanning electron microscope. The margin was evaluated for marginal gap formation. The maximum amount of marginal opening was measured and scores were given as described under ‘Materials and Methods’. Values of marginal adhesives had categorical variables; the groups were compared using proportions of samples, with a particular score in each group. The thermal and mechanical loading deteriorated the marginal adaptation of both the total-etch and self-etch groups. In the self-etch adhesive group, 40% of the samples had no marginal gap, but the number decreased to 20% after loading. Moreover, there was an increase of 10% in the samples with a marginal gap of < 30 μm and a marginal gap of = 30 μm. Similarly, in the total-etch adhesive group, there was a decrease of 40% in the samples with no marginal gap. Also there was a 30% increase in samples with a marginal gap of = 30 μm. Thus, it was observed that thermal and mechanical stresses created marginal gaps in additional samples, where none existed, and increased the number of gaps as well as widened the existing gaps after loading. There was no correlation between the microtensile bond strength and marginal adaptation. The values obtained in this study were lower when compared to the values obtained using flat dentinal surfaces. The possible explanation could be the effect of the cavity configuration factor. Bouillaguet, in 2001, had reported a 20% reduction in the bond strength of class II cavity walls compared to flat dentinal surfaces.[26] Also it was reported that tensile bond strength was lower at the apical wall when compared to the occlusal wall, because of the direction of the tubules.[27]

This study has shown that total-etch systems perform better on caries-affected dentin under thermal and mechanical loading. The conditions in the oral cavity were different from the laboratory conditions, although methods were used to simulate the oral environment. Therefore, the results of this study have to be verified with a long-term clinical study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Perdigao J, Lopes MM, Gomes G. In vitro bonding performance of self-etch adhesives: II-ultramorphological evaluation. Oper Dent. 2008;33:534–49. doi: 10.2341/07-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burrow MF, Kitasako Y, Thomas CD, Tagami J. Comparison of enamel and dentin microshear bond strengths of a two-step self-etching priming system with five all-in-one systems. Oper Dent. 2008;33:456–60. doi: 10.2341/07-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eliguzeloglu E, Omurlu H, Eskitascioglu G, Belli S. Effect of surface treatments and different adhesives on the hybrid layer thickness of non-carious cervical lesions. Oper Dent. 2008;33:338–45. doi: 10.2341/07-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvalho RM, Chersoni S, Frankenberger R, Pashley DH, Prati C, Tay FR. A challenge to the conventional wisdom that the simultaneous etching and resin infiltration always occurs in self-etch adhesives. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1035–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massler M. Changing concepts in the treatment of carious lesions. Br Dent J. 1967;123:547–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei SH, Kaqueller JC, Massler M. Remineralization of carious dentin. J Dent Res. 1968;47:381–91. doi: 10.1177/00220345680470030701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoue G, Tsuchiya S, Nikaido T, Foxton RM, Tagami J. Morphological and mechanical characterization of the acid-base resistant zone at the adhesive-dentin interface of intact and caries-affected dentin. Oper Dent. 2006;31:466–72. doi: 10.2341/05-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertz-Fairhurst EJ, Curtis JW, Jr, Ergle JW, Rueggeberg FA, Adair SM. Ultraconservative and cariostatic sealed restorations: Results at 10 year. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:55–66. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira PN, Nunes MF, Miguez PA, Swift EJ., Jr Bond strengths of a 1-step self-etching system to caries-affected and normal dentin. Oper Dent. 2006;31:677–81. doi: 10.2341/05-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fusayama T, Okuse K, Hosoda H. Relationship between hardness, discoloration and microbial invasion in carious dentin. J Dent Res. 1966;45:1033–46. doi: 10.1177/00220345660450040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aggarwal V, Logani A, Jain V, Shah N. Effect of cyclic loading on marginal adaptation and bond strength in direct vs. indirect class II MO composite restorations. Oper Dent. 2008;33:587–92. doi: 10.2341/07-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavalcanti AN, Mitsui FH, Silva F, Peris AR, Bedran-Russo A, Marchi GM. Effect of cyclic loading on the bond strength of class II restorations with different composite materials. Oper Dent. 2008;33:163–8. doi: 10.2341/07-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omar H, El-Badrawy W, El-Mowafy O, Atta O, Saleem B. Microtensile bond strength of resin composite bonded to caries-affected dentin with three adhesives. Oper Dent. 2007;32:24–30. doi: 10.2341/06-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deliperi S, Bardwell DN, Wegley C. Restoration interface microleakage using one total-etch and three self-etch adhesives. Oper Dent. 2007;32:179–84. doi: 10.2341/06-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong SR, Boyer DB, Keller JC. Microtensile bond strength testing and failure analysis of two dentin adhesives. Dent Mater. 1998;14:44–50. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(98)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouillaguet S, Gysi P, Watana JC, Ciucchi B, Cattani M, Godin CH, et al. Bond strength of composite to dentin using conventional, one-step and self-etching adhesive systems.J. Dent. 2001;29:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(00)00049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue S, Vargas MA, Abe Y, Yoshida Y, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G, et al. Microtensile bond strength of eleven contemporary adhesives to dentin. J Adhes Dent. 2001;3:237–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tay FR, Pashley DH, Suh BI, Carvalhi RM, Itthagarun A. Single-step adhesives are permeable membranes. J Dent. 2002;30:371–82. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(02)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banerjee A, Kidd EA, Watson TF. In vitro evaluation of five alternative methods of carious dentine excavation. Caries Res. 2000;34:144–50. doi: 10.1159/000016582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjørndal L, Darvann T. A light microscopic study of odontoblastic and non-odontoblastic cells involved in tertiary dentinogenesis in well-defined cavitated carious lesions. Caries Res. 2001;33:50–60. doi: 10.1159/000016495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allaker RP, Seddon SV, Tredwin C, Lynch E. Detection of Streptococcus mutans by PCR amplification of the spaP gene in teeth rendered caries free. J Dent. 1998;26:443–5. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall GW, Jr, Chang YJ, Gansky SA, Marshall SJ. Demineralization of caries-affected transparent dentin by citric acid: An atomic force microscopy study. Dent Mater. 2001;17:45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(00)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegde MN, Bhandary S. An evaluation and comparison of shear bond strength of composite resin to dentin, using newer dentin bonding agents. J Conserv Dent. 2008;11:71–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.44054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandava D, P A, Narayanan LL. Comparative evaluation of tensile bond strengths of total-etch adhesives and self-etch adhesives with single and multiple consecutive applications: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2009;12:55–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.55618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hegde MN, Vyapaka P, Shetty S. A comparative evaluation of microleakage of three different newer direct composite resins using a self etching primer in class V cavities: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2009;12:160–3. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.58340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouillaguet S, Ciucchi B, Jacoby T, Wataha JC, Pashley D. Bonding characteristics to dentin walls of class II cavities in vitro. Dent Mater. 2001;17:316–21. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(00)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogata M, Nakajima M, Sano H, Tagami J. Effect of dentin primer application on regional bond strength to cervical wedge-shaped cavity walls. Oper Dent. 1999;24:81–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]