Abstract

Aim:

to evaluate and compares the healing clinically and radiographically following periapical surgery with and without using hydroxyapatite graules.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty patients were selected for the study & the nature of healing is compared with that of conventional periapical surgery. In the present clinical study chitra hydroxyapatite granules, a freeze-dried hydroxyapatite, is used to fill the osseous defects following periapical surgery. Following surgery all patients were assessed both clinically & radiographically for a period of nine months.

Results:

On clinical evaluation the test group did not show any significant immediate or delayed local tissue reactions. Radiographically in the follow up period of 6 – 9 months the bone graft became indistinguishable from the surrounding bone which indicates complete bone regeneration. Where as in the control group ever after 9 months the radiographs showed inadequate bone fills.

Conclusion:

The bone regeneration following periapical surgery can be facilitated by using bone graft. Hydroxyapatite is found to be very effective alloplastic material. Based on this study it might be concluded that in large bone destruction caused by periradicular lesion bone regeneration can be facilitated by effective bone replacing materials like hydroxyapatite.

Keywords: Bone regeneration, hydroxyapatite, periapical surgery

INTRODUCTION

The regeneration of bone following destruction by pathological processes has an important bearing on success following treatment. Inadequate or inconsistent bone healing is caused by ingrowth of connective tissue into the bone space, preventing osteogenesis. Periradicular surgery is not the first choice of treatment in nonhealing periradicular pathosis. Surgery may be undertaken after unsuccessful retreatment, or when retreatment is impossible or has an unfavorable prognosis

The bone regeneration following periapical surgery can be facilitated by placing bone graft into the periapical defect. Different types of bone grafts are available for dental surgical procedure. These include autografts, allografts, xenografts, and alloplasts. The ideal bone replacement material should be clinically and biologically inert, noncarcinogenic, easily maneuverable to suit the osseous defect, and should be dimensionally stable. It should serve as a scaffold for bone formation and slowly resorb to permit replacement by new bone

Calcium-based ceramic materials like calcium hydroxyapatite (HA) and tricalcium phosphate (TCP) had been used popularly for alveolar ridge reconstruction and in periodontal bony defects. In this present study, Chitra hydroxyapatite ceramic granules were used as a bone graft in periapical lesion.[1–4]

Objectives

This study attempts to evaluate and compares the healing clinically and radiographically following periapical surgery with and without using hydroxyapatite graules.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chitra hydroxyapatite granules (Chitra Granules) – freeze dried hydroxyapatite granules, synthesized at the Sree Chitra Thirunal Institute for Medical Sciences & Technology, Thiruvananthpuram. It is a tribasic calcium phosphate having the chemical formula Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2.

I.R.M – used as the Retrofilling Material

Gutta-percha – for Root Canal obturation by lateral condensation method

Twenty healthy patients between the age group of 15 to 35 years were selected and were randomly divided into two groups A and B. Only lesions with 0.5-2cm in dimension in the radiograph were included in the study. The whole surgical procedure was explained to the patient. After getting informed consent from the patient, the treatment was done. Radiographic angulations were standardized for subsequent followup during the period of the study. The root canal treatment was done prior to surgery. All patients were advised to take an NSAID prior to surgical procedure in order to reduce postoperative pain and swelling.

Following the reflection of a full mucoperiosteal flap, inflammatory connective tissue were curetted, root ends were resected, root end cavities were prepared with low speed bur, and filled with IRM.[5,6] In Group A after the surgery bony defect was filled with Chitra hydroxyapatite and was taken as test groups. In Group B, after surgery no bone graft was placed and kept as a control group.

RESULTS

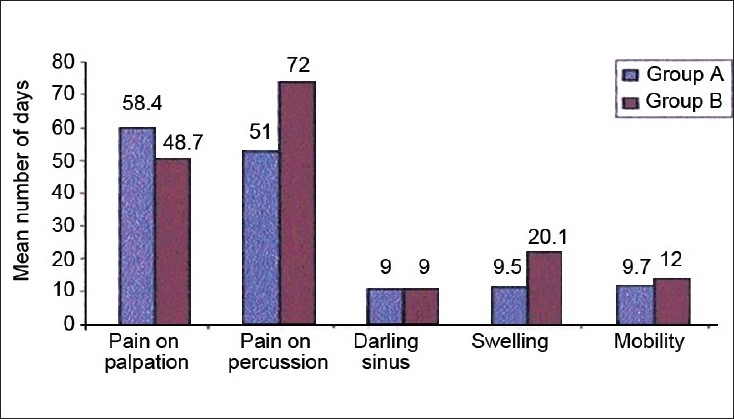

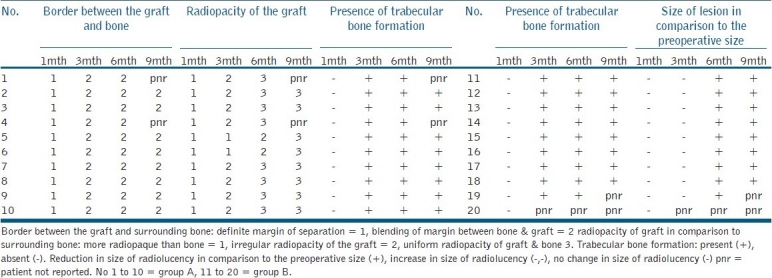

Healing was evaluated clinically and radiographically for a period of 9 months after surgery. Clinical parameters like pain on palpation, pain on percussion, mobility, swelling, and vitality of adjacent teeth were evaluated. [Figure 1] Radiographically the margin between the bone and the graft, radiocapacity of the graft in comparison with the surrounding bone, the presence of trabecular bone formation, and size of the lesion were evaluated [Table 1]. The statistical hypothesis formulated was tested statistically with the help of student t test in the case of quantitative data, and chi-square test (χ2) in the case of qualitative data.

Figure 1.

Clinical evaluation

Table 1.

Radiographic Evaluation of periapical wound healing

On clinical evaluation [Figure 1], the test group did not show any significant immediate or delayed local tissue reactions. Radiographic evaluation [Table 1] at various intervals following the surgery showed a change in the intensity in the radiographs and intermingling of the grafts and surrounding bone which itself indicates bone ingrowth. In the followup period of 6-9 months, radiographically the bone graft became indistinguishable from the surrounding bone, which indicates complete bone regeneration [Figures 2–6]. Whereas in the control group ever after 9 months, the radiographs showed inadequate bone fills [Figures 7–11].

Figure 2.

Group A: Pre Operative Radiograph showing Periapical Radiolucency inrelation to upper incisors

Figure 6.

Group A: Post Operative Radiograph at 9 Months follow up showing uniform radiopacity of the graft and surrounding bone

Figure 7.

Group B: Pre Operative Radiograph showing Periapical Radiolucency inrelation to upper incisors

Figure 11.

Group B: Post Operative Radiograph at 9 Months follow up showing reduction in size of radiolucency but not complete obliteration of the radiolucency

Figure 5.

Group A: Post Operative Radiograph at 6 Months follow up showing uniform radiopacity of the graft

Figure 8.

Group B: Post Operative Radiograph at 1 Month follow up

Figure 9.

Group B: Post Operative Radiograph at 3 Months follow up showing trabecular bone formation from the periphery of the lesion

Figure 10.

Group B: Post Operative Radiograph at 6 Months follow up showing reduction in size of radiolucency but not complete obliteration of the radiolucency

DISCUSSION

The ultimate goal of periapical surgery is the predictable regeneration of periapical tissues, including the complete repair of the osseous defects. Inadequate bone healing is caused by ingrowth of connective tissue into the bone space, preventing osteogenesis. In order to prevent this soft-tissue ingrowth, bone grafts can be used to fill the bony space in case of large bony defects. Because with the evidence of early osseous healing subsequent orthodontic and prosthodontics treatment can be readily performed.

In this present study, 20 patients in the age group of 15-35 years were selected and randomly divided into two groups - A and B. After periapical curettage, the root apex were resected and a retrograde filling with IRM was given. According to studies by Trope.m.et al. Harrison Tw.et al. Yi Tai Jon.et al. reinforced ZOE (Super EBA and IRM) were found and be an ideal retrofilling material.[7] In group A after surgery Chitra hydroxyapatite granules were packed into the bony defect. Group B was kept as a control group in which after surgery no bone graft were used. These granules have a size of 500–1000 μ and pore size of 100–200 μ.

Kenney et al. in their study using porous hydroxyapatite on periodontal defect found connective tissue infiltration through the pores and bone formation form the 3rd month examination onwards.[8] Kwalitter et al. stated that a minimum pore size of 5-15 μ is necessary to encourage fibrous tissue ingrowth. HA used in the study have a pore size of 100–200 μ.[9]

Periapical lesions healing with scar tissue was described by Hames as early in 1933. It is formed by the soft tissue outpacing the slower bone regeneration from the osseous part of the cavity. The hydroxyapatite will act as a filling materials as well as a scaffold, which gradually gets resorbed while preosteoblasts and osteoblasts migrate from the adjacent bone (Osteoconduction).

In this study at 1st month evaluation all radiographs of group A showed a well-defined border between the graft and the bone [Figure 3]. From 3rdmonth onward there was evidence of blending of the graft with the surrounding bone in the radiograph, which indicates osseous ingrowth into the porous HA material [Figures 4–6]. This is in accordance with the study observation found in the study conducted by Kenney EB et al. Oreamuno and Yukna RA.[2,3,9,10] From 3rd month onward the radiocapacity of the hydroxyapatite was found to be decreasing and a more homogenization of radiological picture could be appreciated with a uniform radiocapacity at subsequent followup [Figures 4–6].

Figure 3.

Group A: Post Operative Radiograph at 1 Month follow up showing definite margin of separation of between the bone and graft

Figure 4.

Group A: Post Operative Radiograph at 3 Months follow up showing blending of margin between the bone and graft

CONCLUSION

The bone regeneration following periapical surgery can be facilitated by using bone graft. Hydroxyapatite is found to be very effective alloplastic material. In this present clinical study, hydroxyapatite was used as a bone graft to fill the osseous effects following periapical surgery and was evaluated both clinically and radiographically. On the basis of review of literature and the clinical and radiographic outcomes hereby presented, it might be concluded that in large bone destruction caused by periradicular lesion bone regeneration can be facilitated by effective bone replacing materials like hydroxyapatite. The early bone regeneration also gives functional support to the tooth especially with large periapical bone defects.

Acknowledgments

I express my sincere gratitude & indebtedness to my postgraduate teacher and guide Dr. N.O Varghese, Principal, Govt. Dental College Thiruvananthapuram, Dr. Jolly Mary Varugheese M.D.S– Prof. and Head of the Department, Department of Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics, Thiruvananthpuram, all the patients who had involved in this study

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett JD, Mellonig JT, Gray JL, Towle HJ. Comparison of freeze dried bone allograft and porous HA in human periodontal defects. J Periodontol. 1989;60:231–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.5.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenney EB, Lekovic V, Sa Ferreira JC, Han T, Dimitrijevic B, Carranza FA., Jr Bone formations with porous hydroxyapatite implants in human periodontal defects. J Periodontol. 1986;57:76–83. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.2.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molvan O, Halse A, Grung B. Incomplete healing (scar tissue) after periapical surgery: Radiographic findings in 8-12 years after treatment. J Endod. 1996;22:264–8. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(06)80146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jou YT, Pertl C. Is there a best retrograde filling material? Dent Clin North Am. 1997;41:555–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison JW, Johnson SA. Exicisional wound healing following the use of IRM as a root-end filling material. J Endod. 1997;23:19–27. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trope M, Lost C, Schmitz HJ, Freidman S. Healing of apical periodontitis in dogs after apicoectomy and retrofilling with various filling materials. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:221–8. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oreamuno S, Lekovic V, Kenney EB, Carranza FA, Jr, Takei HH, Prokic B. Comparitive clinical study of porous HA and decalcified freeze dried bone in human perioodntal defects. J Periodontol. 1990;61:399–404. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.7.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenney EB, Lakovic V, Carrenza FA, Jr, Dimitrijenci B. The use of porous hydroxyapatite implants in periodontal defects-clinical results after 6 months. J Periodontol. 1985;56:42–88. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.2.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalwitter JJ, Halbert SF. Applications of porous ceramics for the attachment of load bearing internal orthopedic applications. J Biomed Mater Res 1972;5:161 also cited in: Shetty V, Han TJ. Alloplastic materials in reconstructive periodontal surgery. Dent Clin North Am. 1991;35:521–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yukna RA, Mayer ET, Amos SM. 5 years evaluation of durapatite ceramic alloplastic implants in periodontal osseous defect. J Periodontol. 1989;60:544–56. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.10.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]