Abstract

The present study was performed to determine the optimal entry points and trajectories for cervical pedicle screw insertion into C3–7. The study involved 40 patients (M:F = 20:20) with various cervical diseases. A surgical simulation program was used to construct three-dimensional spine models from cervical spine axial CT images. Axial, sagittal, and coronal plane data were simultaneously processed to determine the ideal pedicle trajectory (a line passing through the center of the pedicle on coronal, sagittal, and transverse CT images). The optimal entry points on the lateral masses were then identified. Horizontal offsets and vertical offsets of the optimal entry points were measured from three different anatomical landmarks: the lateral notch, the center of the superior edge and the center of lateral mass. The transverse angle and sagittal angles of the ideal pedicle trajectory were measured. Using those entry points and trajectory results, virtual screws were placed into the pedicles using the simulation program, and the outcomes were evaluated. We found that at C3–6, the optimal entry point was located 2.0–2.4 mm medial and 0–0.8 mm inferior to the lateral notch. Since the difference of 1 mm is difficult to discern intra-operatively, for ease of remembrance, we recommend rounding off our findings to arrive at a starting point for the C3–6 pedicle screws to be 2 mm directly medial to the lateral notch. At C7, by contrast, the optimal entry point was 1.6 mm lateral and 2.5 mm superior to the center of lateral mass. Again, for ease of remembrance, we recommend rounding off these numbers to use a starting point for the C7 pedicle screws to be 2 mm lateral and 2 mm superior to the center of lateral mass. The average transverse angles were 45° at C3–5, 38° at C6, and 28° at C7. The entry points for each vertebra should be adjusted according to the transverse angles of pedicles. The mean sagittal angles were 7° upward at C3, and parallel to the upper end plate at C4–7. The simulation study showed that the entry point and ideal pedicle trajectory led to screw placements that were safer than those used in other studies.

Keywords: Cervical pedicle screw, Operative simulation system, Entry point, Trajectory

Introduction

The major concern when inserting a cervical pedicle screw is the risk of catastrophic damage to the surrounding neuro-vascular structures such as spinal cord, roots, and vertebral arteries [1–4]. Despite numerous clinical, radiological and cadaveric specimen studies regarding cervical pedicle screw placement, the ideal trajectories and entry points have not been established.

Although several studies have proposed their entry points and trajectories [5–10], each study has its limitations. The studies using cadavers involved a relatively small number of specimens less than 20, while the studies based solely on clinical experience lacked objective validity. Moreover, a major shortcoming of those studies was that the entry points and trajectories were not based on the ideal pedicle trajectory (i.e., a line passing through the very center of the pedicle in all three planes). Topographic landmarks and parameters cannot be determined using simple measurements on axial CT images or gross observation of cadaver specimens. Identification of the true axis should be based on at least two planes of view and ideally, three-dimensional (3D) image reconstructions.

The present study sought to identify the ideal entry point and trajectory for cervical pedicle screw insertion into the C3–7 vertebrae of patients with cervical disease. 3D spine models were constructed using cervical spine axial CT images. These models, in addition to axial, sagittal and coronal images were used in order to determine the true axis passing through the center of pedicles. Topographic landmarks indicating the optimal entry points were then identified. The optimal entry points and trajectories were then used to insert the virtual screws in a specialized surgery simulation program, and the results of those insertions were analyzed.

Materials and methods

Patient demographics

The study involved 40 Asian patients (20 of each sex) aged 18–73 years (mean 52 years) who were hospitalized for various cervical diseases. The cervical vertebrae were examined using multidetector computed tomography (MD-CT) imaging, and 1 mm thickness axial images were taken. The inclusion criteria were no prior cervical spine surgery, fine quality images for the third through seventh cervical vertebrae, and aged 18 years or over at the time of imaging. Subjects with evidence of infectious, neoplastic, traumatic, congenital spine anomalies or severe degenerative changes were excluded from the study.

Determination of optimal trajectory lines and entry points

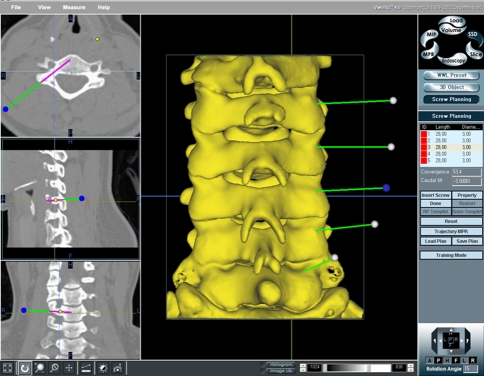

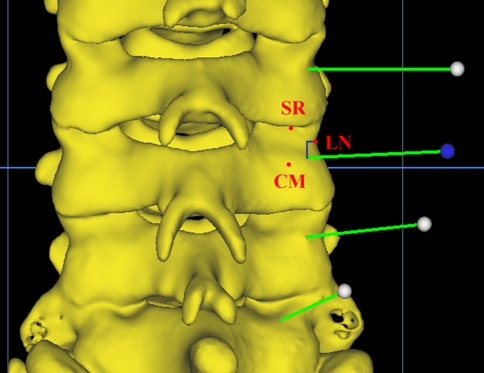

Axial CT images at 1 mm intervals from the third to seventh cervical vertebrae were reconstructed as 3D models using a screw fixation simulation program (V-works Spine Simulator 4.0; Cybermed Inc., Korea). This software can simulate any type of screw placement in the entire spinal column. One surgeon (DHL) drew coaxial trajectory lines passing through the center of each pedicle on axial, sagittal, and coronal planes in a total of 400 pedicles in 40 patients (C3–C7, 80 pedicles per level). This line designates the ideal pedicle trajectory. On the 3D reconstructed image, those lines would penetrate the posterior surface of lateral mass, and this point was established as the optimal cervical pedicle screw entry point passing through the pedicle coaxially (Fig. 1). Three topographic bony landmarks were then chosen: the lateral vertebral notch (LN), the center of the superior ridge of lateral mass (SR), and the center of lateral mass (CM). The entry point location was designated by the horizontal and vertical offsets from those landmarks (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Determination of ideal trajectory of pedicle (ITP) and corresponding entry point (EP). Using a screw fixation simulation program (V-works Spine Simulator 4.0; Cybermed Inc., Korea), ideal trajectory s passing through the center of each pedicle on axial, sagittal, and coronal planes were drawn. Entry points were designated as the point that these lines penetrated the lateral masses

Fig. 2.

Three topographic bony landmarks. The entry point location was designated by the horizontal and vertical offsets from three different landmarks; the lateral vertebral notch (LN), the center of the superior ridge of lateral mass (SR), and the center of lateral mass (CM)

Transverse and sagittal ideal trajectory angles were measured. The transverse angle was the angle between a line perpendicular to the posterior cortex of the vertebral body and the ideal trajectory in the transverse plane. The sagittal angle was the angle between a line parallel to the superior endplate of the corresponding vertebral body and the ideal trajectory on the sagittal image in which each pedicle appeared largest. All measurements were performed independently by two observers, and averages and standard deviations were calculated.

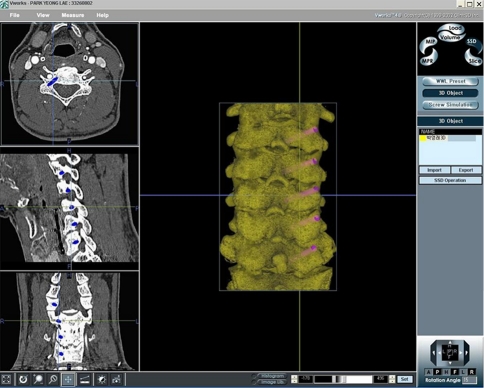

Surgery simulation using the calculated trajectories and entry points

Once trajectories and optimal entry points were determined using the above measurement protocols, screw placement simulation was performed using a 3D cervical spine model created by the V-works Spine Simulator (Cybermed Inc., Korea) for each patient. In this program, only the posterior view of cervical spine was displayed, as is the case in actual surgery. The virtual pedicle screw (3.5 mm diameter, 24 mm length) was inserted from the indicated entry point on the lateral mass into 400 pedicles of 40 patients (bilateral C3–C7) by a spine surgery fellow with no experience in cervical pedicle screw placement, and who had not been involved in the measurement process. Prior to the simulation, he was provided only with the axial CT images of each level to obtain the transverse angle of each pedicle. This pre-measured transverse angle was maintained as identical as possible to the transverse insertion angle displayed on the screen all through the virtual screw placement. The sagittal angle was adjusted using virtual lateral fluoroscopy in another window. After completing the screw placement, its dimensions could be displayed as rods on axial, sagittal, and coronal CT images (Fig. 3). The screw positions and the cortical integrity of the pedicles in all planes were evaluated by two independent surgeons. Cortical breaches were classified as either “minor” (the cortex was disrupted but the center of the screw remained inside the pedicle) or “major” (the center of the screw was located out of the pedicle). The direction of misplacement and direct contact with the vertebral artery were also investigated.

Fig. 3.

Virtual cervical pedicle screw placement simulation. Only using the posterior view of cervical spine, virtual pedicle screws were placed at C3–C7 according to predetermined entry points and trajectories (right column). After completing the procedures, the presence and degree of cortical breaches could be evaluated on axial, sagittal and coronal planes (left column)

Statistical analysis

Averages and standard deviations (SDs) of vertical and horizontal distances were compared using ANOVA and post hoc tests at a 95% confidence level. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 11.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Entry points and trajectories at C3–C6

The entry point for C3–C6 was found to be 2.0–2.4 ± 0.8–1.2 mm (mean ± SD) medial and 0–0.9 ± 1.1–1.5 mm (mean ± SD) distal to the lateral notch. Ignoring the position (i.e., medial or lateral), these distances were shorter than the distances from the midpoint of the superior ridge or the center of lateral mass (P < 0.05) (Table 1). The average transverse angles were 46° ± 4.8° at C3, 45° ± 8.0° at C4, 44° ± 4.0° at C5, and 38° ± 5.0° at C6. The C6 transverse angle was smaller than those of the upper levels. The mean sagittal angle at C3 was 7° ± 4.3° upward, which was larger than the others (Sagittal angle ranged from 3.4° ± 3.9° upwards, to 0.8° ± 3.8° downwards). Sagittal angles of C4–C6 were nearly parallel to their superior end plates (Table 2).

Table 1.

Horizontal and vertical offsets from each reference point to the entry point for each cervical level

| Level | Offset (mean ± SD, mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN | SR | CM | ||||

| Horizontal* | Vertical† | Horizontal** | Vertical†† | Horizontal*** | Vertical††† | |

| C3 | Med 2.0 ± 0.8 | Inf 0.9 ± 1.3 | Lat 2.8 ± 1.2 | Inf 2.9 ± 1.8 | Lat 3.1 ± 1.0 | Sup 3.1 ± 1.4 |

| C4 | Med 2.2 ± 0.9 | Inf 0.0 ± 1.1 | Lat 2.6 ± 1.4 | Inf 2.7 ± 1.7 | Lat 3.2 ± 1.4 | Sup 2.9 ± 1.3 |

| C5 | Med 2.2 ± 0.8 | Inf 0.5 ± 1.5 | Lat 3.3 ± 1.6 | Inf 2.9 ± 2.1 | Lat 3.8 ± 1.0 | Sup 2.5 ± 1.5 |

| C6 | Med 2.4 ± 1.2 | Inf 0.1 ± 1.2 | Lat 2.6 ± 1.5 | Inf 3.6 ± 2.4 | Lat 3.3 ± 1.3 | Sup 2.4 ± 1.3 |

| C7 | Med 4.5 ± 1.9 | Inf 2.3 ± 1.7 | Lat 0.7 ± 1.8 | Inf 2.8 ± 2.1 | Lat 1.6 ± 1.0 | Sup 2.4 ± 1.0 |

LN lateral notch, SR center of the superior ridge, CM center of lateral mass, Med medial, Lat lateral, Sup superior, Inf inferior

*, **, *** P < 0.05; †, ††, ††† P < 0.05

Table 2.

Transverse and sagittal angles for the optimal trajectory at each cervical level

| Level | Transverse angle (mean ± SD, °) | Sagittal angle (°) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Max. | Min. | ||

| C3 | 46 ± 4.8* | 59 | 36 | Up 7 ± 4.3† |

| C4 | 46 ± 4.5* | 56 | 40 | Up 3 ± 3.9†† |

| C5 | 44 ± 4.0* | 54 | 36 | Up 0 ± 3.9†† |

| C6 | 38 ± 5.0** | 47 | 25 | Down 1 ± 3.8†† |

| C7 | 28 ± 4.6*** | 35 | 21 | Down 2 ± 5.4††† |

Max maximum value, Min minimum value, Up upward, Down downward

*, **, *** P < 0.05, †, ††, ††† P < 0.05

Changes in entry point according to the transverse angle for C3 to C6

Transverse angles were found to vary widely, from 25° to 59° (Table 2). We assumed that the medial offset of the entry point would be affected by the transverse angle. The 320 pedicles that we examined from C3 to C6 were divided into four groups according to the transverse angle: <35°, 35°–44°, 45°–54°, and ≥55° (Table 3). The horizontal distances from the lateral notch were then measured and the average in each group was compared with other groups. We found that when the transverse angle was less than 35°, the entry point was located 2.9 ± 1.3 mm medial to the notch. As the transverse angle increased, the entry point moved laterally, such that the group with a transverse angle ≥55° had an entry point 1.2 ± 0.7 mm medial to the notch. The differences between groups were significant (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Transverse angles according to the cervical level

| Transverse angle (°) | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | HO (mean + SD, mm) | N | HO (mean + SD, mm) | N | HO (mean + SD, mm) | N | HO (mean + SD, mm) | |

| <34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 2.9 ± 1.3 | |||

| 44 | 28 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 30 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 42 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 62 | 2.3 ± 1.2 |

| 45–54 | 44 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 42 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 38 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 4 | 2.2 ± 0 |

| 55≤ | 8 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 8 | 1.2 ± 1.0 | 0 | 0 | ||

N number of pedicles, HO horizontal offset

Table 4.

Change in entry point horizontal offset according to transverse angle for C3–C6

| Transverse angle (°) | C3–C6 (N = 320) | |

|---|---|---|

| N | Horizontal offset from lateral notch (mean ± SD, mm) | |

| <35 | 14 | 2.9 ± 1.3* |

| 35–44 | 162 | 2.4 ± 1.0** |

| 45–54 | 128 | 2.0 ± 0.8*** |

| 55≤ | 16 | 1.2 ± 0.7**** |

N number of cases

*, **, ***, **** P < 0.05

Entry point and trajectory at C7

The average entry point for C7 was 4.5 ± 1.9 mm medial and 2.3 ± 1.7 mm inferior to the lateral notch, and was 0.7 ± 1.8 mm lateral and 2.8 ± 2.1 mm inferior to the superior ridge of lateral mass. In addition, the entry point was found to be 1.6 ± 1.0 mm lateral and 2.4 ± 1.0 mm superior to the center of lateral mass. The average transverse angle was 28° ± 4.6°, and the average sagittal angle was 2.0° ± 5.4° downward compared with the upper endplate of C7.

Evaluation of screw placement in surgery simulation

Simulation screws were inserted based on the transverse angle measurements in the corresponding pedicles on axial CT images. We used the lateral notch as a topographic landmark for C3–6 as it was the landmark associated with the smallest horizontal and vertical offsets. The medial offset was modified based on the transverse angle for each pedicle (Table 4). At C7, the entry point was located 1.5 mm lateral and 2.5 mm superior to the center of lateral mass. Four hundred virtual screws were inserted and evaluated. We found that 379 (94.8%) screws were successfully inserted (i.e., the screw was completely contained within the cortical margins of the pedicle). Total breaches occurred in the placement of 21 (5.2%) screws, and these comprised one major and 20 minor breaches. In terms of the cortical perforation direction, the sole major breach occurred in the inferior direction, while the minor breaches comprised 8 medial, 8 lateral and 4 inferomedial perforations. No screw made direct contact with the vertebral artery (Table 5).

Table 5.

Incidence and location of cortical breaches following simulated pedicle screw insertion

| Breach | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | Lateral | Inferomedial | Inferior | ||

| C3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1a | 6 (1.5%) |

| C4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 7 (1.75%) |

| C5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 (1%) |

| C6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.5%) |

| C7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.5%) |

| Total | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1a | 21 (5.25%) |

aMajor breach

Discussion

Biomechanical studies have reported that cervical pedicle screws provide greater stability than other posterior cervical fixation procedures [11–14]. Use of cervical pedicle screws is very effective not only for traumatic and non-traumatic conditions but also for correction of kyphosis and destructive spondyloarthropathy [6, 15–19]. However, the placement of pedicle screws in cervical spine is more technically demanding than in thoracic or lumbar vertebrae because of the smaller pedicle dimension [20, 21], the individual variations in pedicle anatomy [22], and the catastrophic consequences of complications in this area [1–4]. Many studies have reported on the methods used to increase the accuracy of cervical pedicle screw placement, including the use of topographic landmarks [7], measurements of various dimensions and parameters [23–25], and specific surgical techniques or devices [10, 19, 26–28]. However, the methods for precisely and reproducibly determining the ideal entry points and trajectories are yet to be defined.

The cervical pedicle screw insertion technique described by Abumi et al. [6] indicated that the entry point should be “slightly lateral” to the center of the articular mass and “close” to the inferior articular process of the superior vertebra. However, this description was too vague for others to reproduce. Furthermore, it was not appropriate to use the inferior border of the cephalad facet as a topographic landmark because it moves according to neck position, which then places it at different distances from the entry point.

We examined three landmarks as reference points: the lateral notch, the superior ridge, and the center of lateral mass. The lateral notch was first introduced as a distinctive anatomic feature by Karaikovic et al. [7]. Since the lateral notch is located a few millimeters posterolaterally from the vertebral artery when viewed from the back, it can be used as a reference point for the pedicle location. Although Karaikovic et al. clarified the proximity of pedicle entrances to the notch at C2–C7, they did not provide the exact coordinates of entry point from this landmark. Another major limitation of their study was that the true pedicle axis was not used, despite assertions to the contrary. We believe that the ideal pedicle axis in all planes cannot be determined using either cadaver measurements or 3D CT image reconstruction. For image reconstruction, trajectories cannot be traced on the 3D spine model even if multiplanar CT images are used; hence, the entry point cannot be identified on the surface of lateral mass. The ideal trajectory and its associated entry point can only be achieved when utilizing software that simultaneously uses data from both 3D image reconstruction and virtual line drawings inside and outside the bone, as was used in the present study.

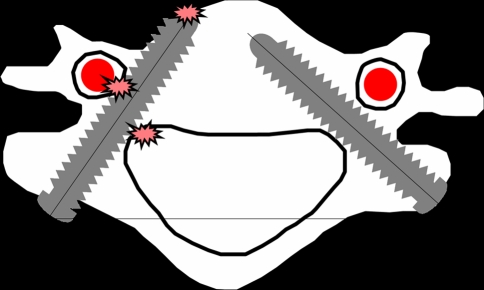

We found that both vertical and horizontal offsets from the lateral notch to the entry point were smaller than those from the center of the superior ridge of lateral mass or the center of lateral mass at C3–C6. The average horizontal and sagittal offsets were not significantly different from C3 to C6; the horizontal offsets were 2.0–2.4 mm medial, and the vertical offsets were 0.0–0.9 mm inferior to the lateral notch. However, transverse angles varied greatly among individuals, meaning that the difference between the minimum and maximum values at each level was so considerable that nominating a fixed transverse angle based on the average transverse angle value would likely lead to dangerous screw misplacement. We found that a transverse angle <35° resulted in an entry point approximately 3 mm medial to the lateral notch, while the entry point was 1 mm medial for an angle ≥55°. Hence, the entry point must be adjusted according to the transverse angle of each individual pedicle due to the wide variations in transverse angle between individuals. The entry point should be more medial for pedicles with a small transverse angle, and more lateral for a pedicle with a large transverse angle. The screw insertion angle on the coronal plane should be consistent with the original transverse angle of each pedicle. While pedicle screws can be placed at an angle of 40°–45° for pedicles with a transverse angle ≥55°, the risk of cortical breakage would increase. The acceptable transverse angle error range is widest when the screw is placed along the true pedicle axis. Reducing these margins for error leads to greater risk of neural tissue injury (medial cortex), vertebral artery injury (lateral cortex), and esophageal injury (anterior cortex) (Fig. 4). While Sakamoto and colleagues reported that the screw insertion angle should be as close as possible to 50° in the transverse plane, and that the entry point should be located as laterally as possible on the posterior surface of lateral mass [25], those suggestions are only appropriate in the cases with large transverse angles.

Fig. 4.

Pedicle screw placement for the pedicle with transverse angle of 55°. Transverse insertion angle of 40°–45° (A) could be possible, however, compared to the insertion technique with an identical angle to coaxial pedicle axis (B), there is less room for error range and more risk of medial, lateral and anterior cortical breaches

The entry point and transverse angle at C7 differed from those at other levels. The entry point was located more centrally close to the center of lateral mass, and the transverse angle was smaller. That was attributed to its transitional characters between cervical and thoracic vertebrae.

We found that mean sagittal angles were similar at C4–C7, which were nearly parallel to the corresponding upper endplate. On the contrary, the axis in the C3 pedicle was directed 7° upward. All sagittal angle values in the present study were similar to those reported by others [20–25, 29].

As a result of the present findings, we propose that entry points should be located 2 mm directly medial to the lateral notch for C3–6 pedicle screws, and then should be adjusted according to the transverse angle of each pedicle, which is usually measured on preoperative axial CT images. As the transverse angle increases, the entry point should move laterally, and vice versa. Sometimes, a larger transverse insertion angle needs a wider midline dissection to avoid screw malposition by the muscular pushing effect, thus resulting in more serious soft tissue injury or bleeding. These complications could be minimized by making separated entry portals through skin and muscles.

In the screw insertion simulation, cortical breaches occurred in very few cases (5.2% of insertions), and all but one were minor. The vertebral artery was never directly contacted by a screw. These findings suggest that the entry points and trajectories identified in the present study are feasible for the safe placement of cervical pedicle screws. The present simulation system does not involve any tactile senses, and there may be even fewer cortical breaches if this system is used in combination with touch, surgical instruments such as probes, imaging devices or navigation systems during the real surgical procedures [10, 27, 28, 30].

The main limitation of this study is that it was performed in Asians. The recommendations therefore may not apply to other races. We plan to repeat this study using CT scans of Caucasians to determine if there is a racial difference. Another limitation is that we included only a limited range of patients by excluding the subjects with infectious, neoplastic, traumatic, congenital anomalies, and even severe degenerative changes. Although these are the very common conditions most spine surgeons have to manage, we were afraid that the anatomical distortion of pedicles by those pathologies might cause any measuring errors. In fact, those pathologies are the variations of normal anatomy in different degrees; therefore, some modifications of the basic entry point and trajectory in each condition could sufficiently provide a safer screw placement.

Conclusion

Based on the 3D reconstruction of MD-CT images and surgery simulation program, the optimal entry points of cervical pedicle screws were located 2 mm directly medial to the lateral notch at C3–6, and 1.6 mm lateral and 2.5 mm superior to the center of lateral mass at C7. However, these entry points should be modified according to the authentic transverse angle of each pedicle. The sagittal angle should be parallel to upper endplate in all levels except C7, in which upward 7°. A thorough understanding of the entry points and trajectories could improve the safety of cervical pedicle screw placement even in the cases that supportive imaging devices or navigation systems could be simultaneously utilized.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Reinhold M, Bach C, Audige L, Bale R, Attal R, Blauth M, Magerl F (2008) Comparison of two novel fluoroscopy-based stereotactic methods for cervical pedicle screw placement and review of the literature. Eur Spine J 17:564–575. doi:10.1007/s00586-008-0584-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Neo M, Sakamoto T, Fujibayashi S, Nakamura T. The clinical risk of vertebral artery injury from cervical pedicle screws inserted in degenerative vertebrae. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:2800–2805. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000192297.07709.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abumi K, Shono Y, Ito M, Taneichi H, Kotani Y, Kaneda K. Complications of pedicle screw fixation in reconstructive surgery of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:962–969. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200004150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ugur HC, Attar A, Uz A, Tekdemir I, Egemen N, Caglar S, Genc Y (2000) Surgical anatomic evaluation of the cervical pedicle and adjacent neural structures. Neurosurgery 47:1162–1168 (discussion 1168–1169) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Abumi K, Itoh H, Taneichi H, Kaneda K. Transpedicular screw fixation for traumatic lesions of the middle and lower cervical spine: description of the techniques and preliminary report. J Spinal Disord. 1994;7:19–28. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199407010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abumi K, Kaneda K. Pedicle screw fixation for nontraumatic lesions of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:1853–1863. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199708150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karaikovic EE, Kunakornsawat S, Daubs MD, Madsen TW, Gaines RW. Surgical anatomy of the cervical pedicles: landmarks for posterior cervical pedicle entrance localization. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:63–72. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200002000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludwig SC, Kramer DL, Balderston RA, Vaccaro AR, Foley KF, Albert TJ. Placement of pedicle screws in the human cadaveric cervical spine: comparative accuracy of three techniques. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:1655–1667. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludwig SC, Kramer DL, Vaccaro AR, Albert TJ. Transpedicle screw fixation of the cervical spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;359:77–88. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199902000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng X, Chaudhari R, Wu C, Mehbod AA, Transfeldt EE (2010) Subaxial cervical pedicle screw insertion with newly defined entry point and trajectory: accuracy evaluation in cadavers. Eur Spine J 19:105–112. doi:10.1007/s00586-009-1213-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Johnston TL, Karaikovic EE, Lautenschlager EP, Marcu D. Cervical pedicle screws vs. lateral mass screws: uniplanar fatigue analysis and residual pullout strengths. Spine J. 2006;6:667–672. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones EL, Heller JG, Silcox DH, Hutton WC. Cervical pedicle screws versus lateral mass screws. Anatomic feasibility and biomechanical comparison. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:977–982. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee JM, Kraiwattanapong C, Hutton WC. A comparison of pedicle and lateral mass screw construct stiffnesses at the cervicothoracic junction: a biomechanical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:E636–E640. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000184750.80067.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunlap BJ, Karaikovic EE, Park HS, Sokolowski MJ, Zhang LQ (2010) Load sharing properties of cervical pedicle screw-rod constructs versus lateral mass screw-rod constructs. Eur Spine J. doi:10.1007/s00586-010-1278-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Abumi K, Ito M, Kaneda K. Surgical treatment of cervical destructive spondyloarthropathy (DSA) Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2899–2905. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abumi K, Kaneda K, Shono Y, Fujiya M. One-stage posterior decompression and reconstruction of the cervical spine by using pedicle screw fixation systems. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:19–26. doi: 10.3171/spi.1999.90.1.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abumi K, Shono Y, Taneichi H, Ito M, Kaneda K. Correction of cervical kyphosis using pedicle screw fixation systems. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:2389–2396. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oda I, Abumi K, Ito M, Kotani Y, Oya T, Hasegawa K, Minami A (2006) Palliative spinal reconstruction using cervical pedicle screws for metastatic lesions of the spine: a retrospective analysis of 32 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31:1439–1444. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000219952.40906.1f [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Yukawa Y, Kato F, Ito K, Horie Y, Hida T, Nakashima H, Machino M (2009) Placement and complications of cervical pedicle screws in 144 cervical trauma patients using pedicle axis view techniques by fluoroscope. Eur Spine J 18:1293–1299. doi:10.1007/s00586-009-1032-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Karaikovic EE, Daubs MD, Madsen RW, Gaines RW. Morphologic characteristics of human cervical pedicles. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:493–500. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199703010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panjabi MM, Duranceau J, Goel V, Oxland T, Takata K. Cervical human vertebrae. Quantitative three-dimensional anatomy of the middle and lower regions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991;16:861–869. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin EK, Panjabi MM, Chen NC, Wang JL. The anatomic variability of human cervical pedicles: considerations for transpedicular screw fixation in the middle and lower cervical spine. Eur Spine J. 2000;9:61–66. doi: 10.1007/s005860050011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onibokun A, Khoo LT, Bistazzoni S, Chen NF, Sassi M. Anatomical considerations for cervical pedicle screw insertion: the use of multiplanar computerized tomography measurements in 122 consecutive clinical cases. Spine J. 2009;9:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruofu Z, Huilin Y, Xiaoyun H, Xishun H, Tiansi T, Liang C, Xigong L (2008) CT evaluation of cervical pedicle in a Chinese population for surgical application of transpedicular screw placement. Surg Radiol Anat 30:389–396. doi:10.1007/s00276-008-0339-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sakamoto T, Neo M, Nakamura T (2004) Transpedicular screw placement evaluated by axial computed tomography of the cervical pedicle. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 29:2510–2514 (discussion 2515) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Karaikovic EE, Yingsakmongkol W, Gaines RW. Accuracy of cervical pedicle screw placement using the funnel technique. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:2456–2462. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotani Y, Abumi K, Ito M, Minami A. Improved accuracy of computer-assisted cervical pedicle screw insertion. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:257–263. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.99.3.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu S, Xu YQ, Lu WW, Ni GX, Li YB, Shi JH, Li DP, Chen GP, Chen YB, Zhang YZ (2009) A novel patient-specific navigational template for cervical pedicle screw placement. Spine 34:E959–E966. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c09985 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Chazono M, Soshi S, Inoue T, Kida Y, Ushiku C. Anatomical considerations for cervical pedicle screw insertion: the use of multiplanar computerized tomography reconstruction measurements. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4:472–477. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.4.6.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yukawa Y, Kato F, Yoshihara H, Yanase M, Ito K. Cervical pedicle screw fixation in 100 cases of unstable cervical injuries: pedicle axis views obtained using fluoroscopy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5:488–493. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.5.6.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]