Abstract

Background

Making healthcare treatment decisions is a complex process involving a broad stakeholder base including patients, their families, health professionals, clinical practice guideline developers and funders of healthcare.

Methods

This paper presents a review of a methodology for the development of urological cancer care pathways (UCAN care pathways), which reflects an appreciation of this broad stakeholder base. The methods section includes an overview of the steps in the development of the UCAN care pathways and engagement with clinical content experts and patient groups.

Results

The development process is outlined, the uses of the urological cancer care pathways discussed and the implications for clinical practice highlighted. The full set of UCAN care pathways is published in this paper. These include care pathways on localised prostate cancer, locally advanced prostate cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, hormone-resistant prostate cancer, localised renal cell cancer, advanced renal cell cancer, testicular cancer, penile cancer, muscle invasive and metastatic bladder cancer and non-muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Conclusion

The process provides a useful framework for improving urological cancer care through evidence synthesis, research prioritisation, stakeholder involvement and international collaboration. Although the focus of this work is urological cancers, the methodology can be applied to all aspects of urology and is transferable to other clinical specialties.

Keywords: Urological cancer, Care pathways, Systematic review, Clinical practice guidelines

Introduction

Challenges in urological cancer treatment decision-making

In making healthcare decisions regarding treatment, decision makers are confronted with several fundamental issues. At the individual level, patients and clinicians are primarily concerned with the balance between the perceived benefits and harms of treatment discussed, whilst for healthcare systems, policy makers need to know which treatments should be provided. This societal aspect will be informed by information on costs, cost-effectiveness and arguably, some notion of fairness such as equal access for equal need. In conditions such as localised prostate cancer for which multiple management options exist, the situation becomes even more complex. One approach to facilitate individual decision-making and decisions regarding treatment provision is evidence-based medicine [1], in which choices are made on the basis of the best available evidence obtained from robust methodology; evidence that is valid, reliable and of high quality. To be useful, this evidence must be readily accessible. Systematic reviews are one method of identifying and synthesising research evidence on a particular subject [2]. The review process, review findings and subsequent guideline recommendations can also be used to identify gaps in knowledge about treatment effects (uncertainties) and inform future work to address important gaps.

The strengths and limitations of systematic review methodology

Reasons for undertaking a systematic review include resolution of conflicting evidence or clinical uncertainties, explanation of variations in practice, or to confirm the appropriateness of current practice. To achieve these outcomes, a systematic review requires a transparent and replicable synthesis process [3] with effect estimates obtained by meta-analysis using appropriate statistical techniques. Typically, a systematic review involves a well-formulated question or questions, comprehensive searches of the major electronic databases, pre-defined study eligibility criteria, an unbiased study selection process and data extraction against a set of pre-determined outcomes using standard forms. These data are critically appraised, including rating of the quality of the evidence and quantitative synthesis with meta-analysis where appropriate. This transparent and replicable process differentiates systematic from narrative reviews, which are more prone to bias.

A key limitation of any systematic review is that it cannot overcome problems inherent in the design, conduct and reporting of the included primary studies [3–5]. Their authority can also be undermined by errors in review methodology or reporting leading to variation in conclusions drawn by separate systematic reviews attempting to answer the same question. As a consequence, widely accepted guidelines for the conduct and reporting of primary studies and systematic reviews, such as CONSORT, Cochrane Handbook and PRISMA, [6–8] have been established.

Defining the question

Defining the review question for a systematic review is the first and most important stage of the process as this provides the direction for all subsequent stages [9]. Paradoxically, while methodology has advanced for the actual process of a systematic review, there has been little work done to establish the best way of identifying areas of clinical uncertainty and prioritising a list of questions that maintains relevance for all interested groups. One approach is to perform a scoping study [10]; this involves an initial literature search to assess whether a full systematic review is both feasible, that is there are sufficient primary studies available for synthesis, and relevant, that is there is no existing equivalent review document. Another approach is evidence mapping [11], which was used by the Global Evidence Mapping Initiative in Australia [12]. Here, the number and quality of relevant studies retrieved from literature searches and their summary outcomes are tabulated for each condition or treatment of interest. A potential drawback of this approach is that it does not map the entirety of the research that could be conducted within a given clinical subject area or indeed the importance of any gaps within the evidence.

The urological cancer care pathways (UCAN care pathways from here on) being developed by our group are an attempt to address these issues. In September 2004, we facilitated plenary discussions involving urological clinicians, patients and their partners including expertise and experience of the five main cancers: kidney, bladder, prostate, testis and penis. The purpose was to better understand the needs of individuals with urological cancer in the context of their cultural setting and health system. The principal messages from patients and their families were that the following improvements are needed: (1) Better and more accessible information backed up by evidence, which could help them make decisions about their care, (2) Better care of for those that suffer unwanted effects of cancer treatment, and (3) Better support throughout their journey of care both in the clinical setting and at home. In response, a Scottish Charity (UCAN) committed funding of £2.6 million to address these gaps in urological cancer care focussed on people living in north-east Scotland but also reflecting an international perspective. Discussion with the research group on how to address the first principal message, the requirement for better and more accessible evidenced-based information for patients led to the development methodology to formulate UCAN care pathways, which we discuss in the present paper.

Our main objective is to map all plausible treatment options for each of the five urological cancers to allow collection of an appropriate range of existing and new systematic evidence reviews of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alternative treatment options including the magnitude of risk of short- and long-term adverse effects. We will also engage key clinical experts and patients to prioritise unanswered questions and identify significant evidence gaps in the evidence to direct future research priorities. The ultimate aim of the UCAN care pathways is to build an evidence base for the major urological cancers and develop a framework to inform future systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines, care algorithms, integrated care pathways and research priorities [13]. We will also work to establish a framework for wider engagement of clinicians, patients, researchers, healthcare policy makers and healthcare funders in priority setting within this clinical specialty and inform the development of a set of core outcomes for both research and clinical practices. The strength of the UCAN care pathways will be to harness and rationalise all our efforts to answering the key questions for universal benefit.

Development of urological cancer care pathways

What are care pathways?

A care pathway is a tool constructed with multidisciplinary input and used by healthcare professionals and/or researchers to map a patient’s journey in terms of which treatments should be given, by whom, when, and to what outcome [13–16]. This broad characterisation includes many different terminologies including care profile, care protocol, critical care pathway, care map, integrated care pathway, and different uses dependent on the context, user and the stage in the research process at which it is considered. Systematic reviewers, for example, may use a care pathway to identify all plausible treatment options for a particular patient group with a view to identifying gaps in current knowledge, thereby informing possible review questions. Policy makers may use a care pathway to establish a standardised treatment algorithm for a specific clinical problem in clinical practice that can then be implemented in a particular healthcare organisation [13, 17].

These examples can be seen as occupying two ends of a process: driving the research agenda on the one hand and providing a clinical useable output on the other. We see the UCAN care pathways more as being drivers of the research agenda but also providing structure for guideline developers. They are designed to inform the scope, search strategy, development and prioritisation of focussed clinical questions for relevant systematic reviews. They lend themselves well to informing development (including scope) of clinical practice guidelines rather than informing actual practice as is the purpose of clinical practice guidelines. They provide a framework for systematic review teams and guidelines panel members to identify and prioritise topic areas, to highlight areas where guidance is currently lacking or the evidence is unclear and to reduce redundancy and resource wasting.

Methodology

Steps in the development of the UCAN care pathways

Definition of the aim of an individual UCAN care pathway. For example, what are the treatment options for localised prostate cancer? This will require a structured list of options and the eligibility characteristics to enter the pathway.

Establishment of an advisory group. This should include both clinical and methodological experts drawn from national and international professional bodies, together with representation from patient groups as lay experts and those who have experienced the disease. The purpose of the advisory group is to provide a range of user perspectives necessary to inform the development of the pathway.

Draughting of all plausible treatment options from the point of diagnosis moving forward to the end of treatment, follow-up and death in the form of a flow chart to producing a comprehensive but concise one-page summary.

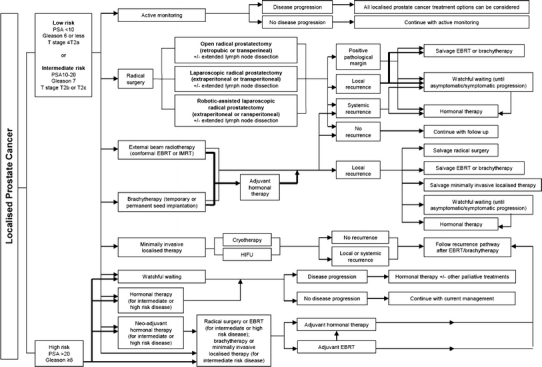

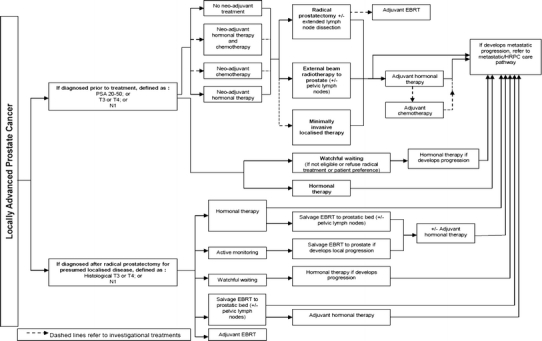

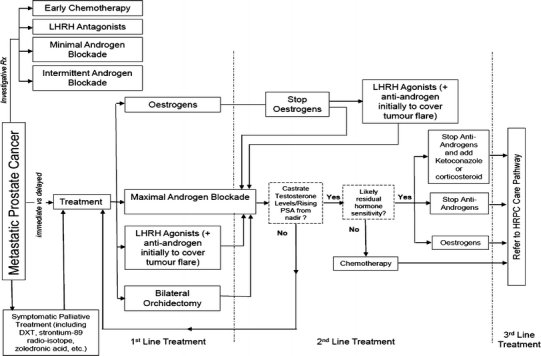

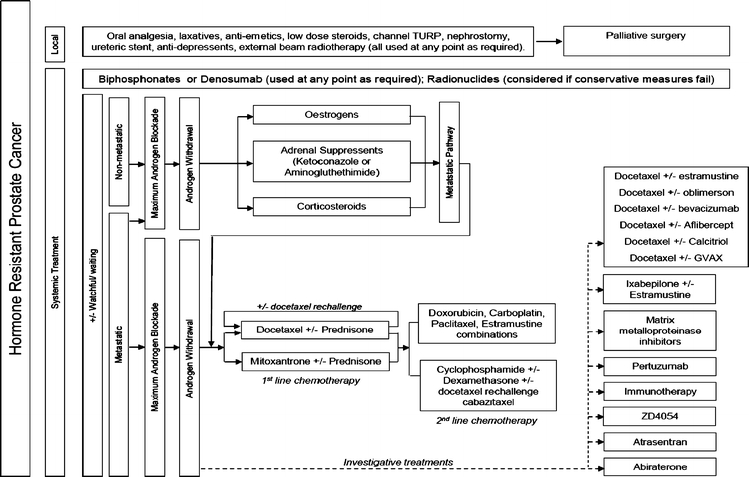

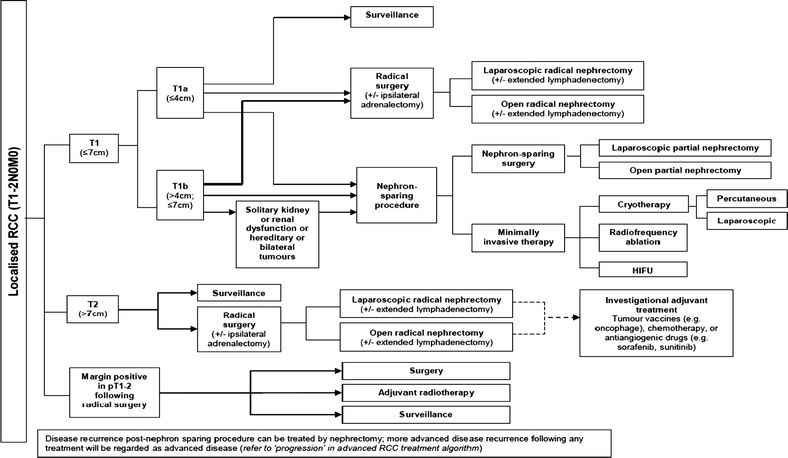

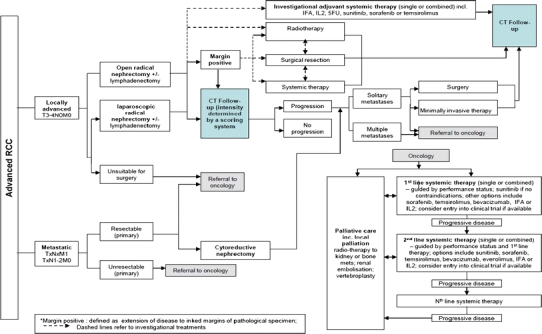

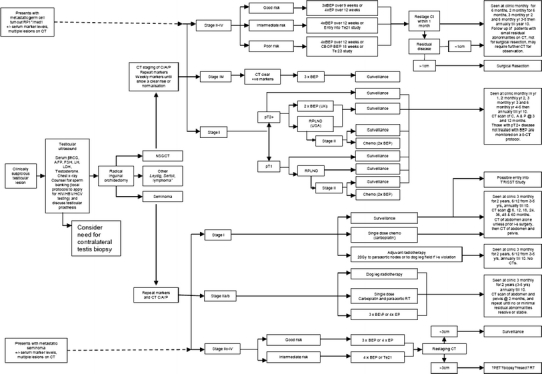

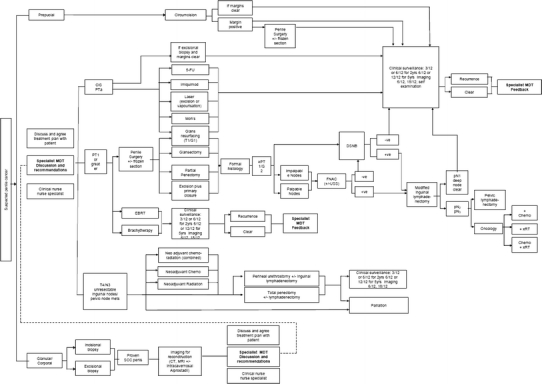

Iterative development of the pathway by consensus clearly describing key areas of uncertainty to create a final version for dissemination (Figs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10).

Fig. 1.

Localised prostate cancer care pathway. Abbreviations: PSA prostate-specific antigen, EBRT electron beam radiotherapy, IMRT intensity-modulated radiation therapy, HRPC hormone refractory prostate cancer, LHRH luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone, DXT deep X-ray therapy, TURP transurethral resection of the prostate, GVAX granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor [or GM-CSF] vaccine, ZD4054 Zibotentan

Fig. 2.

Locally advanced prostate cancer care pathway. For abbreviations, refer Fig. 1

Fig. 3.

Metastatic prostate cancer care pathway. For abbreviations, refer Fig. 1

Fig. 4.

Hormone-resistant prostate cancer care pathway. For abbreviations, refer Fig. 1

Fig. 5.

Localised renal cell cancer care pathway. Abbreviations: HIFU high-intensity focussed ultrasound, CT computed tomography, IFA interferon-alpha, IL2 interleukin 2, 5FU 5 Fluorouracil

Fig. 6.

Advanced renal cell cancer care pathway. For abbreviations, refer Fig. 5

Fig. 7.

Testicular cancer care pathway. Abbreviations: AFP alpha-fetoprotein, bhCG beta-human chorionic gonadotropin, BEP bleomycin/etoposide/cisplatin, C/A/P chest/abdomen/pelvis, CBOP carboplatin, bleomycin, vincristine, and cisplatin, CT computed tomography, EP etoposide/cisplatin, FSH Follicle-stimulating hormone, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, HBV hepatitis B virus, HCV hepatitis C virus, i-s inguinoscrotal, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, LH luteinizing hormone, med 1° medistinal primary, NSGCT non-seminoma germ cell tumour, PET positron emission tomography, RP 1° retroperitoneal primary, RPLND retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, RT radiotherapy, Te21 trial to compare Taxol-BEP vs BEP alone in intermediate prognosis disease, Te23 trial comparing CBOP BEP combinations in poor prognosis with BEP, TRISST TRial of imaging and schedule in seminoma testis, UK United Kingdom, USA United States of America, Yrs years

Fig. 8.

Penile cancer care pathway. Abbreviations: 5-FU 5 fluorouracil, CIS carcinoma in situ, DSNB dynamic sentinel node biopsy, FNAC Fine needle aspiration cytology, MDT multidisciplinary team, SCC squamous cell carcinoma, USS ultrasound scanning

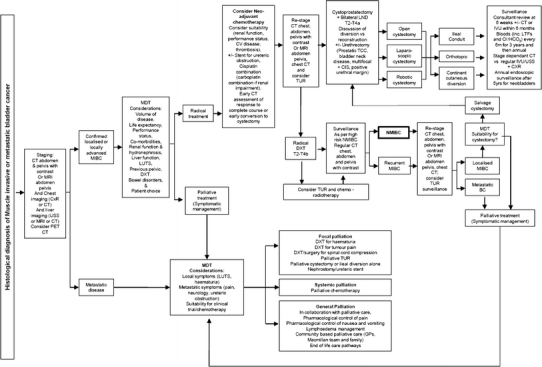

Fig. 9.

Muscle invasive metastatic bladder cancer care pathway. Abbreviations: BCG bacillus calmette-guérin, CIS carcinoma in situ, CXR chest X-ray, INFα interferon-alpha, IVU intravenous urogram, LUTS lower urinary tract symptoms, LND lymph node dissection, MIBC muscle invasive bladder cancer, NMIBC non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, Prostatic TCC transitional cell carcinoma of the prostate, TB tuberculosis

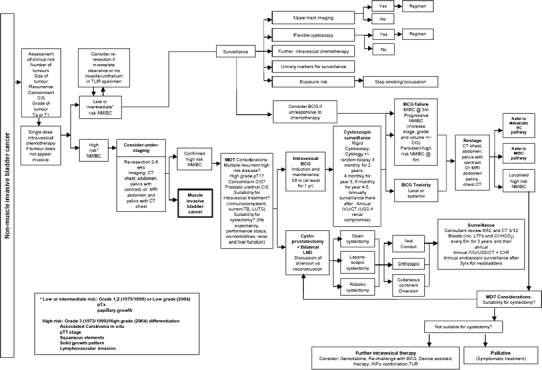

Fig. 10.

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer care pathway. For abbreviations, refer Fig. 9

Engagement with clinical content experts and patient groups

The reasons for engaging with content experts are threefold. First, to ensure that the UCAN care pathways are comprehensive and reflect contemporary clinical practice within the pre-defined societal location. Second, to achieve engagement with the process and to give ownership of the UCAN care pathways, the systematic reviews and any subsequent clinical practice guidelines driven by the systematic reviews to key figures (opinion formers) within the discipline. This is important to facilitate any required behaviour change and the adoption of evidence-based practice across the discipline. Third, to develop an international collaboration to advance the practice of evidence-based medicine within urology. Patient involvement is also a necessary step in identifying appropriate patient-reported outcomes, understanding which approaches to delivering care and which outcomes are most important to patients, facilitating shared decision-making and increasing patient satisfaction.

Use of urological cancer care pathways

Standardisation of terminology (treatment options and definitions)

Our methodology gives a clear opportunity to gain clear consensus regarding definitions of treatment options. This precision in terminology is vital to ensure that the conduct and reporting of research, the systematic review process and the clinical practice guidelines development process are relevant to all.

Informing search strategy

The aim of the search strategy for a systematic review is to maximise both the sensitivity and the specificity of the search results, that is, to retrieve all the relevant articles and exclude the irrelevant ones. In order to design the strategy, the question first needs to be translated into searchable terms using the PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework. The UCAN care pathways greatly facilitate this step, as all plausible interventions that can be compared are clearly shown for each patient group at every stage in the disease process. Also, the format of the pathway allows the reviewer to see where the search question is focussed in the context of the entire pathway and to see which interventions and stages of the disease are being excluded from the search. This is particularly useful when refining and reviewing the results of the search.

Therefore, as the UCAN care pathways succinctly represent the required detailed and complex information, the reviewer is readily able to understand the specific patient groups and interventions being reviewed and focus the search accordingly. Hence, the pathways are a key element in the design and execution of searches to inform systematic reviews for specific stages of the pathway. The same process can be employed in the definition of focused clinical questions by clinical practice guideline panels.

Prioritisation (review scope, guideline scope and development process)

Systematic reviews can be used to provide more reliable and precise estimates of relative effectiveness of competing treatments and highlight areas where further primary research is needed. Resources are however always limited, and therefore, the questions requiring performance of a systematic review need to be prioritised. There is also a linked need to prioritise topics for clinical practice guidelines based on evidence from systematic reviews. Prioritisation should be a process that is systematic and transparent and that includes consultation with key experts [18].

The UCAN care pathways inform the prioritisation process by providing a comprehensive framework for discussion that is applicable to multiple settings both nationally and internationally. They also inform the prioritisation process by highlighting where in the process of care the uncertainty is and the magnitude of the problem in terms of the number of people affected and its consequences. As such, they provide a concise summary of the various treatment options and inform the scope of systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines. The UCAN care pathway model also ensures that the systematic review activity is firmly embedded in the context of the overall management of patients.

Economic evaluation and care pathways

Economic evaluation involves the comparative analysis of alternative interventions in terms of benefits such as improvement in health, the value of those improvements to individual patients and costs [19]. An economic evaluation has to be based upon a care pathway, as an understanding is needed of what the sequence of events is from initiation of the treatment under study. The UCAN care pathways can be used to identify events that will influence a patient’s well-being and events that use or save resources. Once these events have been established, they can then be measured and valued [20].

Estimates of benefits and costs can be based on data from randomised controlled trials or from a mathematical model. The models can be constructed using decision analytic methods to provide a mathematical representation of a UCAN care pathway. A model is a further level of evidence synthesis as it may incorporate the results from a number of systematic reviews.

In addition to information on cost-effectiveness, an economic model can show who stands to benefit most from use of a particular healthcare intervention and who is most likely to bear the cost. These analyses can inform judgements about equity of provision. Economic models can also be used to highlight areas for further research either by showing precisely what evidence is missing or more formally by quantifying the value of further research in terms of balancing the cost of gaining the new evidence against the subsequent benefits that are likely to accrue by calculation of value of information [21].

Conclusions

We believe that the UCAN care pathways provide a crucial framework for improving urological cancer care through evidence synthesis, research prioritisation, stakeholder involvement and international collaboration. The process of developing these pathways is an important vehicle for influencing the discipline of urology by facilitating engagement with the principles of evidence-based medicine through international collaboration. They also hold the promise of advancing the goal of standardising terminology within urology and improving communication between healthcare professionals, researchers, patients, policy makers and funders, in different geographical locations. Finally, they inform the development and conduct of systematic reviews, the development of clinical practice guidelines and economic evaluation of interventions within urology.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed here are the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of any other person or organisation. The authors would like to thank all of those who contributed to the development of the care pathways and Karin Plass (EAU Guidelines Office) for her helpful comments on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix: Members of the UCAN Care Pathway Development Group

The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the UCAN Care Pathway Development Group. These are Michael Aitchison, Peter Albers, Marek Babjuk, John Calleary, James Catto, Nicholas Cohen, Phillip Conford, Norman Dublin, Steven Finney, David Gillatt, Leyshon Griffiths, Rakesh Heer, Axel Heidenreich, Simon Horenblas, Mari Imamura, Ann-Maree Kennedy, Roger Kockelbergh, Thomas Lam, Marie Carmela Lapitan, Börje Ljungberg, Graham Macdonald, Steven MacLennan, Samuel McClinton, Malcolm Mason, Said Mishriki, Leslie Moffat, James N’Dow, Muhammad Imran Omar, Linda Pennet, Robert Pickard, Giorgio Pizzocaro, Andrew Protheroe, Bhavan Rai, Justine Royle, Pamela Royle, Katie Schumm, Mike Shelley, Andreas Skolarikos, Duncan Summerton, Satchi Swami, Nick Watkin and Timothy J. Wilt.

Footnotes

The members of the UCAN Care Pathway Development Group are given in the “Appendix”.

References

- 1.Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268:2420–2425. doi: 10.1001/jama.268.17.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulrow CD. Systematic reviews: rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309:597. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6954.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg AX, Hackam D, Tonelli M. Systematic review and meta-analysis: when one study is just not enough. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:253–260. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01430307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tseng TY, Dahm P, Poolman RW, Preminger GM, Canales BJ, Montori VM. How to use a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2008;180:1249–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald SL, Canfield SE, Fesperman SF, Dahm P. Assessment of the methodological quality of systematic reviews published in the urological literature from 1998 to 2008. J Urol. 2010;184:648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, For the CONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group ThePRISMA. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scales CD, Jr, Norris RD, Keitz SA, Peterson BL, Preminger GM, Vieweg J, Dahm P. A critical assessment of the quality of reporting of randomized, controlled trials in the urology literature. J Urol. 2007;177:1090–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EPPI Centre (2010) Setting scope and methods for the review. http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=171

- 10.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz DL, Williams AL, Girard C, Goodman J, Comerford B, Behrman A, Bracken MB. The evidence base for complementary and alternative medicine: methods of evidence mapping with application to CAM. Altern-Ther-Health-Med. 2003;9:22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Global Evidence Mapping Initiative (2009) Traumatic brain and spinal cord injury. http://www.evidencemap.org

- 13.Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N, Porteous M. Integrated Care Pathways. BMJ. 1998;316:133–137. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7125.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammond R (2002) Integrated care pathways. Chartered Society of Physiotherapists. PA46: Feb 2002

- 15.Jones T, de Luc K, Coyne H. Managing care pathways: the quality and resources of hospital care. London: The Association of Certified Chartered Accountants; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Pathway Association (2010) Clinical/care pathways [Online] Available: http://www.e-p-a.org/000000979b08f9803/index.html. Accessed 13/09/10

- 17.Jones T. Implementation of hospital care pathways for patients with schizophrenia. J Nurs Manag. 2000;8:215–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2834.2000.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development 2: priority setting. Health Res Policy Syst. 2006;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox-Rusby J, Cairns J, editors. Economic evaluation. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tappenden P, Chilcott JB, Eggington S, Oakley J, McCabe C. Methods for expected value of information analysis in complex health economic models: developments on the health economics of interferon-β and glatiramer acetate for multiple sclerosis. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:1–92. doi: 10.3310/hta8270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]