Abstract

Communicating about sex is a vital component of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention and influences how HIV educators convey messages to communities and how couples negotiate safer sex practices. However, sexual communication inevitably confronts culturally based behavioral guidelines and linguistic taboos unique to diverse social contexts. The HIV interventionist needs to identify the appropriate language for sexual communication given the participants and the message. Ethnographic research can help facilitate the exploration of how sex terminology is chosen. A theoretical framework, developed to guide HIV interventionists, suggests that an individual's language choice for sexual communication is influenced by gender roles and power differentials. In-depth interviews, free listing and triadic comparisons were conducted with Xhosa men and women in Cape Town, South Africa, to determine the terms for male genitalia, female genitalia and sexual intercourse that are most appropriate for sexual communication. Results showed that sexual terms express cultural norms and role expectations where men should be powerful and resilient and women should be passive and virginal. For HIV prevention education, non-mother tongue (English and Zulu) terms were recommended as most appropriate because they are descriptive, but allow the speaker to communicate outside the restrictive limits of their mother tongue by reducing emotive cultural connotations.

Introduction

Without a known cure or an effective vaccine, prevention is currently the most effective approach for addressing the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic. Preventing HIV transmission requires knowledge, motivation and behavioral skills to reduce or eliminate risk [1]. Much of prevention depends on communication; both between health educators and the community and between individuals engaging in or seeking to prevent potentially risky behavior [2].

For most cultures, communication about sex and sexuality is complex and difficult. On the one hand, HIV prevention interventionists seek to be explicit and detailed in pointing out the risks associated with specific behaviors and the actions needed to reduce risk. On the other hand, the language that is permissible varies dramatically in public and private settings, among single and mixed gender groups, among older and younger people and for the objectives of titillation versus education. Each linguistic and cultural group has its own terms that range from anatomical and exact to polite and vague to ‘bad language’. The interaction of settings and terms create a major challenge for the interventionist; a challenge that frequently goes unrecognized when western-derived programs are implemented in non-western nations and cultures.

This paper contends that before an HIV interventionist can promote safe sex practices in a given culture, there needs to be empirically based research to understand the language and context necessary for culturally relevant and appropriate sexual communication. The fundamental issues that must be addressed center on how sexuality and sexual risk are expressed, with what linguistic terms, and in what social context. This paper explores concepts of sexual communication as a part of an HIV prevention project in South Africa. The objectives are to present the linguistic patterns of sexual communication and their variations among Xhosa people in Cape Town, describe a methodology for exploring sexual communication that can be applied in a wide range of cultural contexts and illustrate the importance of understanding culturally specific communication patterns for the HIV prevention interventionist.

Sexuality and communication

All societies restrict sexual behavior and sexual communication through explicit and implicit social rules. These dynamics exist within a structured set of behavioral guidelines that create cultural norms for how sex and sexuality can be expressed [3]. The expression of sexual stimulation and needs are controlled by cultural rules and guidelines; the breaking of these rules can have a deleterious effect on the individual's social standing within the group.

Sex is private and sexual organs are covered to a greater or lesser degree and labeled as ‘private parts’, protecting both the individual and maintaining group behavioral norms. For many cultures, the transition from adolescence to adulthood by ritual provides an opportunity to enculturate young people into appropriate behavior with regard to propriety and sexual behavior.

Although sex is a behavior innate to all humans, it is cultural factors that have created variations in the psychological, social and physical responses to human sexuality [4] resulting in different meanings of sex and normative sexual behavior at the local level. Combating the HIV epidemic is difficult because prevention methods must be relevant to each group's distinctive view of sex. To devise effective teaching strategies for safer sex education, it is necessary to understand local sex cultures and forms of popular cultural representation so that the interventionist can determine how safer sex practices can be accommodated within the constraints of local cultural norms [5, 6].

Sexual communication

Sexual communication is one aspect of human sexuality that is deeply embedded in the local cultural context. Culturally based communication strategies are a critical component of HIV/AIDS prevention [7]. Exploring how people communicate about sex and sexuality at a local level is imperative to inform further research on communication strategies around culturally sensitive topics. The challenge is to take that talk into the public domain [8]. Language choice is influenced by conversation appropriateness in the social context (public, private and mixed gender). As a result, sexual communication is modified to fit the norms within specific social contexts presented by a cultural group. Individuals, especially men, often manipulate sexual language to preserve male hegemony [9]. Preventing HIV infection requires both individuals and interventionists to challenge the social order (e.g. a woman requesting a man to use a condom) and to communicate these new behaviors in a way that promotes adoption while not violating social taboos.

Theoretical framework

A framework incorporating components and theories of communication was developed as a tool for understanding sexual communication among Xhosa speakers in South Africa. The framework brings awareness of elements that influence communication, including maintaining ‘face’, minimizing threat, projecting identity, acknowledging power differentials, upholding gender roles and understanding denotative and connotative meanings. These elements influence speakers to utilize strategies in conversations, including using culturally approved politeness criteria to choose contextually appropriate language.

According to Le Page and Tabouret-Keller [10], language allows ‘individuals to project their identity and shape it according to the behavioral patterns of the groups with which they wish to identify’ (p. 2). Examining language use within social interactions shows that language processes are affected by a broad range of interpersonal and social factors. An individual's choice of language is influenced by who is being spoken to and the themes of the conversation. Using language to maximize the benefit to self, minimize the threat to others and display adequate proficiency in the accepted standards of social etiquette is the goal of conversation politeness [11]. The need to maintain politeness in conversation is directly linked to maintaining one's positive image, or ‘face work’, and in the presence of others, mediates social interactions [12]. Certain speech acts, such as criticism, disagreement and mention of taboo topics [13] are fundamentally face threatening and individuals choose linguistic strategies, such as more polite terms, to minimize the threat of a particular speech act [14]. In addition, a person's perception of whether certain conversations, especially sexual communication, are face threatening depends on differing levels of relative power between speaker and addressee, the social distance between speaker and addressee and the conversation's degree of imposition [14].

Within the theoretical framework of sexual scripts, interpersonal scripts developed between individuals are often influenced by power differentials between men and women. All human societies make social distinctions based on gender, and most societies are patriarchal and allocate more power and higher status to men [15]. Power plays a role in sexual relationships when one partner acts independently, dominates relationship decision making, engages in behavior against the other partner's wishes or controls a partner's actions [16]. Evidence from research on sexual scripting suggests that power helps individuals construct sexuality and will affect the value one places on their sexual health. Women in power-imbalanced relationships experience multiple barriers for HIV risk reduction, including risks for destabilizing the relationship and sexual violence when requesting to use condoms raises her partner's suspicions about sexual histories or monogamy [17–20]. Couples may engage in less sexual communication in power-imbalanced relationships. These concerns limit safe sex negotiations and may have direct consequences for whether a couple will engage in unprotected sex, sex during a sexually transmitted infection (STI) or sex during menstruation. Language choice is often influenced by gender-based power differentials, which result in men and women developing different languages for communication. In instances where women are in a lower power status than their conversation partner, they will use a speech style that reflects that power imbalance, termed by Lakoff [21] as ‘women's language’.

The meaning of terms can affect language choice in conversations. When language is examined for meaning, terms have both denotative and connotative meanings. Denotative meanings are literal and explicit and connotative meanings are emotive and implicit [22].

Sexual terminology is classified in this paper as anatomical, euphemistic, slang and non-mother tongue. Anatomical words describe in technical terms a particular part of the body or bodily fluids. Euphemisms are terms that denote one concept, but connotatively mean another. Speakers that use this linguistic substitution strategy [23] seek to create a balance between approaching and avoiding taboo conversation topics [24–27]. Slang terms are expressions not used in formal speech, but are more often used to express shared meanings within a specific sub-group and have no literal meaning other than the definition a sub-group gives it. However over time, slang can move beyond the sub-group to general society. Slang is frequently used by men to communicate about sex to establish sexual reputations [5].

‘Code switching’ [28] from ‘mother tongue’ to another vernacular during a conversation is another language strategy. Choosing a non-mother tongue (e.g. the colonial language in a non-western setting) during sexual communication is a tactic to reduce threat to ‘face’ by displacing the topic from the speaker's own language and culture. Non-mother tongue terms are often used because they frequently do not hold the same level of connotative and emotional impact that a term with the same meaning would have in mother tongue. Switching to non-mother tongue has been observed among bilingual Mexican American women during sexually related conversations as a way to minimize potential threat and embarrassment [29].

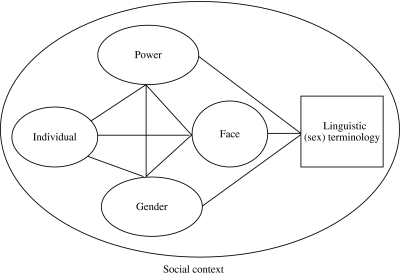

The theoretical framework proposed in this paper posits the individual and the individual's communication within a social context where gender and relative power significantly influences language choice from the perspective of denotative and connotative terminology and ultimately the social identity for that individual in a particular context. Thus, appropriate terminology for the interventionist is based on a multifactoral model as depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A theoretical framework for exploring linguistic terminology choice in sexual communication.

Methods

The data for this paper were part of a larger HIV prevention intervention study [30] to develop and test a theory-based behavioral risk reduction intervention for men who are at risk for HIV and committing gender-based violence. The design called for men to become advocates for risk reduction behavior in their communities by learning communication skills for initiating conversations about HIV prevention [31]. When project interventionists taught communication skills for risk reduction, they learned that participants had a limited range of acceptable terms to use for sex and genitalia since many Xhosa words for sex were offensive in many social contexts. Formative research was needed to explore concepts of sexual communication among Xhosa speakers. Using the theoretical framework, research was conducted on language and sexual communication to develop culturally appropriate messages for HIV prevention programs. This study received institutional review board approval from the University of Connecticut and the Human Sciences Research Council.

Research setting

South Africa contains many cultures and 11 official languages. The Xhosa language belongs to the Nguni cluster family of Bantu languages [32] and is the mother tongue for 23% of the population [33]. Often, individuals are fluent in their native mother tongue of Xhosa and in English. English is used as a common medium in South Africa among people with diverse language backgrounds [34].

For Xhosa men and women, language choice is affected by gender roles and power differentials established through social expectations and cultural rites. For men, ideal gender roles are learned through circumcision as a rite de passage into manhood. Historically, Xhosa used circumcision and initiation rites to strengthen boys to become warriors [35, 36]. Presently, they are associated with the establishment of community ideals [35], the enhancement of masculine virility, complementary opposition between men and women and preparation for marriage and adult sexuality [37, 38]. Male initiation involves the physical act of circumcision followed by a period of isolation for healing, cultural teachings and elder influence. Through tolerance of pain and isolation, men become powerful by proving themselves to be worthy of manhood [39]. Initiation rituals establish ethnic identity and gender distinctiveness [40] by demonstrating ideals of honor and masculinity [39]. By signifying masculine identity, initiation empowers men over boys and women [41] and these rituals affect how men express their sexuality. Initiates are taught to keep the rituals of initiation a secret and language choice frequently aids in maintaining the secrecy associated with circumcision.

Women's sexual identity in Xhosa culture is influenced by the traditional context of Xhosa marriage, where the bride becomes a member of the groom's family. A payment of ‘bride wealth’ (lobola), often with cows, is given by the groom's to the bride's family [2]. Along with this exchange is the transfer of the wife's decision-making authority to her husband and his family [42]. Being betrothed in this context facilitates the formation of power within the marriage. The women's duty is to bear children and care for the family while husbands are the decision makers. It is considered inappropriate for a woman to acknowledge or display sexual feelings of any kind, even in a conjugal relationship.

Methods

Ethnographic research with Xhosa speakers about language and sexual communication was conducted in an urban informal (township) settlement and at a sexually transmitted infection clinic in Cape Town, South Africa. Conceptual meanings [43] for sexual communication were explored by investigating cultural knowledge and knowledge embedded in words, stories and in artifacts [44].

In Phase I, interviews that defined the area of inquiry and sexual term free listing were conducted. Free listing is a method where the interviewer elicits all the items contained in a domain by asking the respondent to list items they feel are contained in that domain. Participants were asked to name all terms for male and female genitalia, and the terms for sexual intercourse. The free-list terms were entered into ANTHROPAC 4 [45] and a free-list salience index was generated [46, 47]. The most salient terms were selected for further analysis in Phase II.

Phase II interviews involved triadic comparisons to determine the relative politeness of the items identified in the free listing. Triadic comparisons explore how a particular term is viewed in relationship to other terms by systematically comparing it with all others in groups of three [47]. Respondents were presented multiple sets of three terms and asked to rank the most polite term as a 1, the next most polite term a 2 and the remaining term with a 3. Politeness scales were developed for male and female genitalia and sex by adding up the number rankings that correspond to each term. This scale illustrated how individuals view one word compared with another by ordering the terms from most polite to least polite.

A consensus analysis [48] was conducted with the scores of the triadic comparisons to determine whether the total group of respondents share similar views on the politeness scales for male genitalia, female genitalia and sexual intercourse terms. In this analysis, respondent's scores were correlated with other individuals within the total sample and between gender groups, resulting in a correlation matrix. Consensus analysis was conducted by performing a varimax (rotated) factor analysis of this matrix to look for agreement patterns. The level of agreement of the whole sample and within gender groups was determined by examining the resulting eigenvalues, where a ratio of at least 3:1 indicates strong agreement or consensus of the model. The higher the eigenvalue ratio for the whole group and each gender group, the stronger the consensus for the politeness scale.

Although not a native Xhosa speaker, the researcher met numerous times with native Xhosa speakers to gain a better understanding of the denotative and connotative meanings behind each of the terms. The third author of this paper is a native Xhosa speaker and was involved in all aspects of the data collection and theoretical development.

Respondents

Respondents came from townships that are characterized by extreme poverty with a median monthly household income of 833ZAR (US$111) [49], a HIV prevalence rate of 27% [50] and 35% having had a history of an STI [51]. In Phase I, interviews were conducted with six men and six women. Mean age of participants was 36 years old, all first-language Xhosa speakers and five self-reported very good or excellent knowledge of English. In Phase II, interviews were conducted with 11 men and 8 women. Mean age of participants was 34 years of age, only 5% were married, but 32% were living with a partner, 58% had less than a Grade 12 education level and 53% self-reported very good knowledge of English. Participants in both phases were interviewed by a native bilingual female or male Xhosa interviewer. All interviews were conducted in Xhosa with some participants occasionally code-switching into English.

Results

The results of this research will focus on interpreting the politeness of words for male genitalia, female genitalia and sexual intercourse since these are among the terms most used in HIV prevention education.

Male genitalia terms

Free-listing among men and women yielded 11 male genitalia terms (see Table I). These terms supported Xhosa-defined gender roles by suggesting that the penis, like the men, should be powerful, resilient and masculine. Included in the list were the terms instimbi (an iron), Four Five (slang), ubhuti (brother) and umthondo (circumcised penis). The term instimbi means an iron, suggesting hardness and power. The term Four Five is a reference to the Colt .45 gun and is used by men to refer to their penis in the company of other men. ‘When guys like us are together and you go pee, you go off to Four Five’ (male, 26 years old). Ubhuti is a Xhosa term for brother. The connotative meaning for this term means to show ‘Respect for the penis’, and ‘Respect for the man’. Ubhuti is often used to describe the male genitalia with children. Since many learn this respectable term as children, they will continue using ubhuti in adulthood. Umthondo (circumcised penis) is a direct Xhosa word for male penis and is reserved only for men that have experienced initiation and circumcision:

This word of umthondo must not be used just anywhere. It must be said when you are with men only. The other word is ‘manhood’. With a younger boy I will tell him all the words that are being used but also informing him which words to use when sitting with men only and which words to use when you are in the company of women.(male, 28 years old)

These male genitalia terms encompass themes of male power and reflective of respect, hardness and force. They are indicative of what masculine ideals are in Xhosa society.

Table I.

Free-listing terms for male genitalia among Xhosa men and women

| Term | Translation | Language | Language type | Frequency | Average ranking |

| Umthondo | Circumcised penis | Xhosa | Anatomical | 9 | 4.667 |

| Incanca | Baby bottle | Xhosa | Euphemism | 9 | 5.11 |

| Ipipi | Penis | Xhosa | Anatomical | 5 | 6.4 |

| Umsama | Not applicable | Xhosa | Slang | 2 | 7 |

| Amasende | Genitals | Xhosa | Anatomical | 2 | 7.5 |

| Four Five | Gun | Xhosa | Slang | 1 | 4 |

| Iketile | Kettle | Xhosa | Euphemism | 1 | 6 |

| Penis | Penis | English | Anatomical English | 1 | 1 |

| Ijwabi | Foreskin | Xhosa | Anatomical | 1 | 2 |

| Ubhuti | Brother | Xhosa | Euphemism | 1 | 8 |

| Istimbi | Iron | Xhosa | Euphemism | 1 | 3 |

However, not all terms for male genitalia were reflective of male power and men were less comfortable using terms that they perceived to diminish male power. Males were less likely to use the terms ijwabi (foreskin) and incanca (baby bottle) compared with women. The term ijwabi (foreskin) describes the anatomical features of the male genitalia. Men did not feel comfortable using this term because it is associated with the secretive circumcision ritual. As one informant discusses here:

There is this thing circumcision where people took the foreskin. And men become very sensitive when you talk about the foreskin. Because the others still have the foreskin and the others don’t have the foreskin and the way you take it out is different between the clans. So there are a lot of politics with the foreskin. (female, 43 years old)

The other euphemistic term, incanca, translates into something you suck on or a baby's bottle. The term diminishes manhood, making it difficult for some men to use the term. Many informants also expressed that language changes after you are circumcised, ‘When you graduate (after circumcision), you don’t use incanca anymore’ (male, 26 years old). Also, since that word refers to a baby's bottle or breastfeeding, men may not use that term because ‘There is no power in sucking a bottle or breastfeeding’. These terms have a connotation suggesting lower power and weakness, particularly in relation to women. As all the male respondents reported, discussions about circumcision and initiation rites of passage were deemed appropriate for men only and inappropriate for women. Here male respondents explain their reasons for why they avoid this conversation topic with women:

There are things that must be talked in the ‘kraal’ (an enclosure for cattle) only with men. Even this issue of condoms, you will provide an answer but this answer it is addressed to men not women. Issues of men are meant for men only. (male, 28 years old)

We as Xhosa people are hiding initiation from women. They know that we are being cut but we don’t give them the whole story as to how it's been done. You will even hear my sister asking ‘what do you do on the mountain’. I will say we just sit there and talk and have fun that is it. I don’t even want to go into details about it because we are hiding this from the women. (male, 29 years old)

Female genitalia terms

Free-listing among men and women yielded 11 female genitalia terms (see Table II). These terms supported cultural concepts of female gender identity by presenting the vagina as gentle, precious and virginal. Included in the list were igusha (sheep), unocwaka (quiet girl) and ikomo zikatata (my father's cows). The term igusha is Xhosa for sheep and is used with young girls. Informants compared the vagina with a sheep because both are ‘humble’, ‘hairy’, ‘innocent like a lamb’ and ‘quiet’. These views were expressed by both men and women during the interviews, ‘Usually when someone is innocent and quiet, they will say that so and so is a sheep’ (female, 37 years old). Mothers express to their daughters to ‘stay innocent, quiet and humble’ or to be ‘like a lamb’. This is also personified with the term unocwaka (quiet girl) where ideal women are thought to be humble, innocent and virginal. Ikomo zikatata translates into my father's cows in which the vagina is compared with the exchange of cattle before marriage connoting value and wealth, particularly if it is virginal. Here one informant explains how a woman's chastity and purity has a value:

Maybe the vagina will depend on how many cows you will get. So don’t sleep around. (female, 37 years old)

Table II.

Free-listing terms for female genitalia among Xhosa men and women

| Term | Translation | Language | Language type | Frequency | Average rank |

| Ikuku | Fat cake | Xhosa | Euphemism | 10 | 4.2 |

| Inyo | Vagina | Xhosa | Direct | 8 | 7.88 |

| Ibhentse | Hole | Xhosa | Slang or direct | 6 | 3.83 |

| Nosisi | Sister | Xhosa | Euphemism | 6 | 6 |

| Vagina | Vagina | English | Anatomical English | 5 | 1.2 |

| Igusha | Lamb or sheep | Xhosa | Euphemism | 2 | 5 |

| Inqgungqu | Baby | Xhosa | Slang | 2 | 8 |

| Itswele | Onion | Xhosa | Euphemism | 2 | 4.5 |

| Isibumbhu | Hole | Xhosa | Slang or direct | 1 | 8 |

| Ikomo zikatata | My father’s cows | Xhosa | Euphemism | 1 | 12 |

| Unocwaka | Quiet girl | Xhosa | Euphemism | 1 | 9 |

However, not all terms for female genitalia were reflective of female innocence. Both males and females were less likely to use the terms that diminish female status, such as ibhentse (hole), isibumbhu (hole) and inyo (hole). These direct terms describe the anatomical features of the female organ and are seen as degrading to women. Informants who mentioned these terms referred to them as swear words, or profanity, ‘I become afraid to say ibhentse. It seems as if you are swearing at someone’, (female, 47 years old) and ‘For women, I cannot say inyo because it sounds rude and vulgar in Xhosa. As a person you must be respectful. It would be as if I am swearing at them if I am to call them that’ (female, 32 years old).

Sexual intercourse terms

Free-listing among men and women yielded 13 sexual intercourse terms (see Table III). These terms supported cultural concepts of sexual intercourse by presenting the coital act as intimate and consensual. Ukulalana means to have sex between a man and a woman. This term is most popular with sex education programs. Ukuphana means ‘to give’. Although it describes sex in Xhosa, the term has a positive connotation because it means you are giving yourself to your sexual partner. Informants described ukuphana with intimate expressions, ‘I give, you give’ and ‘We give to each other’. Ukumetshana (match parts) describes sex as two people coming together to share an intimacy.

Table III.

Free-listing terms for sexual intercourse among Xhosa men and women

| Term | Translations | Language | Language type | Frequency | Average rank |

| Ukulalana | To sleep with | Xhosa | Direct | 10 | 3.7 |

| Ukutyana | Eat each other | Xhosa | Euphemism | 8 | 3.625 |

| Ukukhwelana | Animals mating | Xhosa | Euphemism | 5 | 8 |

| Have sex | English | English | Direct | 5 | 2.8 |

| Ukuphana | To give | Xhosa | Euphemism | 4 | 5.250 |

| Isex | English | English | Direct | 4 | 2.8 |

| Ukuzuma | Sudden | Xhosa | Euphemism | 3 | 8.33 |

| Ukushinana | Not applicable | Xhosa | Slang | 2 | 2.5 |

| Ukuhaver | To have | Xhosa | Direct | 2 | 4.5 |

| Ukuphiwa | Not applicable | Xhosa | Slang | 2 | 6 |

| Ukumetshana | Match | Xhosa | Euphemism | 2 | 8 |

| Let's go to PE | English | English | Euphemism | 1 | 1 |

| Ukwabelana ngesondo | To share a cloth | Zulu | Euphemism | 1 | 11 |

However, not all terms for sexual intercourse were reflective of intimacy and consensuality. Both males and females were less likely to use terms in which the words describe sex as something a man will take from a woman, as without consent, or directly describing sex. Ukukhwelana is term used to describe animals mating and many informants referred to learning about sex from seeing animals mate. Ukutyana (eat each other) relates sex to eating, devouring or taking, relating sex to something that a man will take or something he will do to her. These terms describe sex as an action, instead of an intimate act. Visualizing the action of sexual intercourse may make people consider terms to be very rude. As one informant explains, terms for sexual intercourse that do not have a loving connotation are difficult to say:

When you speak of love everything you say should be a reflection of it. Now these words are rude. This person, if he should use them, it shows that he is not in love with you. (female, 37 years old)

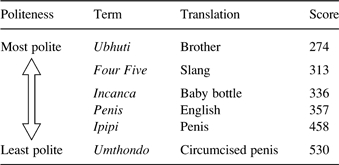

Triadic comparisons for male genitalia

Results from triadic comparisons for the male genitalia formed a politeness scale in order from most polite to least polite: ubhuti (brother), Four Five (slang), incanca (baby's bottle), penis (English), ipipi (penis) and umthondo (grown man's penis). The scores correspond to how polite the terms were compared with the other terms and more polite terms received a lower overall score (see Table IV). Ubhuti and Four Five were the most polite. The triadic comparison results indicate that penis was more polite than the euphemistic word, incanca. This rating could be due to males being uncomfortable to mention incanca. Ipipi and umthondo are considered the least polite of all the terms. Both men and women were in agreement that these terms are too close to circumcision.

Table IV.

Politeness scale for male genitalia terms among Xhosa men and women

|

The consensus analysis of the relative politeness of male genitalia terms resulted in an eigenvalue ratio for the total sample of 3.61, a 2.79 ratio for men only and a 5.91 ratio for women only. These results indicate significant agreement among all the respondents on the consensus of this politeness scale. There was slightly less significance in agreement between men respondents only, but a much larger amount agreement of these terms among the women.

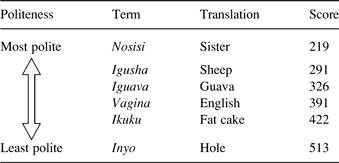

Triadic comparison for female genitalia

Results from the female genitalia triadic comparisons are in order from most polite to most impolite: nosisi (sister), igusha (sheep), iguava (guava), vagina (English), ikuku (fat cake) and inyo (hole) (see Table V). Nosisi is the most polite because this euphemistic term is often mentioned to women as a sign of respect. Igusha and iguava are also polite because they are euphemisms used to describe female genitalia. Vagina was more polite than ikuku and inyo because it utilizes an English term. Ikuku and inyo are the least polite of all the terms because they diminish female identity and are often associated with swearing. The consensus analysis of the triadic comparisons for politeness of the female genitalia terms resulted in an eigenvalue ratio for the total sample of 4.44, a 4.11 ratio for men only and a 5.4 ratio for women only. These results indicate that the total sample of respondents achieved consensus with the women demonstrating more agreement than the men.

Table V.

Politeness scale for female genitalia terms among Xhosa men and women

|

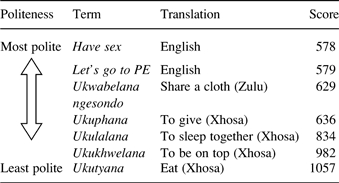

Triadic comparisons for sex

Results from the triadic comparisons of sex terms are in order from most polite to most impolite: have sex (English), Let's go to PE (English euphemism), ukwabelana ngesondo (Zulu), ukuphana (give), ukulalana (sex), ukukhwelana (to be on top) and ukutyana (eat) (see Table VI). The English terms, have sex and let's go to PE (Port Elizabeth—a city located in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, suggests taking a holiday), are the most polite because they have an intimate connotation and are in English. Ukwabelana ngesondo comes from Zulu, meaning to share a cloth. The remaining four terms are Xhosa. Ukuphana is an intimate term referring to sex as something that is shared between partners. Ukulalana is less polite than ukuphana because it directly describes what happens during sex. Finally, ukukhwelana and ukutyana are the least polite of all the terms because they describe sex as rough and animalistic. The consensus analysis for the triadic comparisons of sex terms on the politeness scale showed an eigenvalue ratio for the total sample of 7.01, a 4.95 ratio for men only and a 12.74 ratio for women only, indicating a high degree of consensus among the total sample with again women being in more agreement than men.

Table VI.

Politeness scale for sexual intercourse terms among Xhosa men and women

|

Discussion

Terms used among Xhosa to communicate about sexuality are reflective of the individual speaker, their gender identity, their relative power and status and the social context in which the communication takes place. Similar to Marston [52], the results presented in this paper indicate that sexual terminology is gendered and reflective of social expectations. Terms for male genitalia suggest that men should be powerful and resilient. Terms for female genitalia suggest women should be gentle, passive and virginal. Terms that challenge gender ideals are often avoided, and when used, can be derogatory and diminish the opposite sex. For men, terms and topics related to male genitalia are often associated with the masculine ideals developed during initiation rituals and these ideals are shared among circumcised men because of behavioral and language guidelines. Using terms that diminish the opposite sex in same gender groups may affect the way men and women choose terms and communicate about sex in mixed gender groups, making safer sex negotiations more challenging. Similar to the stance of Groce et al. [53], initiation rituals that acculturate men and women into appropriate sexual behavior could be opportunities to change sexual communication guidelines for mixed gender groups, fostering better communication skills between men and women.

The significant levels of agreement identified through consensus analysis for the politeness levels of male, female and sex terminology indicate that respondents shared common cultural knowledge about which terms are more appropriate than others. It is interesting to note that women generally had a greater degree of agreement than men. This result may be indicative of the fact that men use a broader range of terminology in both mixed groups and with male peers while women are more restricted in both terminology and opportunities to discuss sex.

Finding terms for HIV education messages are not easy and attention to gender, politeness and specificity should be taken into account as HIV education messages are formulated. Direct or anatomical terms may offend individuals, but euphemism and slang terms could be not direct enough to educate effectively. This paper builds upon research conducted by Sanders and Robinson [54] and shows that Xhosa respondents preferred euphemisms, slang, English and Zulu (non-mother tongue) terms over anatomical or direct Xhosa sexual descriptions. Using English or Zulu terms in this multilingual context could provide the means of satisfying both criteria. For a HIV prevention intervention with Xhosa in Cape Town, it is the authors' recommendation to use penis for male genitalia, vagina for female genitalia and sex for sexual intercourse. When the direct or anatomical terms become too emotionally charge or deemed vulgar, terms derived from other languages enable the HIV interventionist to move outside the culturally restrictive limits of one's own language by reducing the speaker's emotive cultural connotations. In a context where first-language Xhosa speakers do not have any knowledge of English, the recommendation is to use ipipi for male genitalia, ikuku for female genitalia and ukulalana for sexual intercourse. These terms are direct enough to describe the concepts, and only slightly lower on the politeness scale than the English and Zulu terms.

From the gender perspective, the dilemma becomes that the terms that are most acceptable for the Xhosa public or mixed gender groups may be reinforcing patriarchal gender norms. The cultural norms that characterize women's genitalia as diminutive and passive make the process of increasing women's ability to resist unwanted sex and/or require condom use more difficult for the HIV prevention interventionist. The HIV interventionist must be aware of this dilemma, make the contradiction explicit to audiences, while also finding terms that are more gender neutral.

The framework proposed in this paper calls for ethnographic analysis of power, gender and identity in social context to establish culturally appropriate terminology for sexuality. The methods of free listing and triad sort, along with in-depth interviews, provide a methodology for exploring these issues in association with HIV prevention efforts.

This paper has argued that HIV prevention requires an allocation of time and resources to develop a body of knowledge concerning the linguistic terminology of local cultural groups with regards to sexuality. Acceptable terms must take into consideration the context of communication between individuals of senior versus junior status, males versus females, the empowered versus the disempowered, mixed versus the single gender groups and the public arena versus the private conversations of individuals and small groups. While aiming for the most acceptable terms, the risk is run that there will be less communication of sexual knowledge and prevention behavior. At the same time, by communicating more directly, the risk of offending or alienating is greater. Nonetheless, the HIV pandemic in South Africa calls for extreme measures and projects may need to risk offending to effectively reach men and women. Rather than finding the ideal set of terminology, the HIV interventionist must be knowledgeable about the local meaning of sexually related terminology as derived from the framework and methodology used in this paper. We suggest sharing that understanding and working together with local people to increase the efficacy of the education process and reduce the risks of inappropriate language.

Funding

National Institute for Mental Health at the National Institutes of Health (R01 MH071160).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions and support of Xolani Nibe, Seth Kalichman, Leickness Simbayi, Kristin Kostick and Yolande Shean.

References

- 1.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:455–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maharaj P. Male attitudes to family planning in the era of HIV/AIDS: evidence from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J South Afr Stud. 2001;27:245–57. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagnon W, Simon J. Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell R, Gordon M. The Social Dimension of Human Sexuality. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castro-Vazquez G, Kishi I. ‘If you say to them that they have to use condoms, some of them might use them. It is like drinking alcohol or smoking’: an educational intervention with Japanese senior high school students. Sex Educ. 2002;2:105–17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holland J, Ramazanoglu C, Sharpe S, et al. Sex, Risk, and Danger: AIDS Education Policy and Young Women's Sexuality. London: Tuffnell Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Airhihenbuwa CO, Obergon R. A critical assessment of theories/ models used in health communication for HIV/AIDS. J Health Commun. 2000;5(Suppl):5–15. doi: 10.1080/10810730050019528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawhall N. Consenting adults, talk about sex and AIDS. Bua. 1993;8:23–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders J, Robinson W. Talk and not talking about sex: male and female vocabularies. J Commun. 1979;29:222–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.LePage RB, Tabouret-Keller A. Acts of Identity: Creole-Based Approaches to Ethnicity and Language. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watts RJ, Ide S, Ehlich K. Politeness in Language: Studies in Its History, Theory and Practice. Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goffman E. Interaction Ritual: Essays in Face-to Face Behavior. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makin VS. Face management and the role of interpersonal politeness variables in euphemism production and comprehension. Diss Abstr Int B Sci Eng. 2004;64:4077. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown P, Levinson S. Politeness: Some Universals in Language Use. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strebel A, Crawford M, Shefer T, et al. Social constructions of gender roles, gender-based violence and HIV/AIDS in two communities of the Western Cape, South Africa. SAHARA J. 2006;3:516–28. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2006.9724879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42:637–60. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell CA. Male gender roles and sexuality: implications for women's AIDS risk and prevention. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:197–210. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00322-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jewkes R, Penn-Kekana L, Levin J, et al. Prevalence of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse of women in three South African provinces. S Afr Med J. 2001;91:421–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalichman SC, Williams EA, Cherry C, et al. Sexual coercion, domestic violence and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women. J Womens Health. 1998;7:371–8. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wingwood GM, DiClemente RJ. The Effects of an abusive primary partner on the condom use and sexual negotiation practices of African-American women. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1016–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lakoff R. Language and Women's Place. New York: Harper Row; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Poecke L. Denotation/connotation and verbal/nonverbal communication. Semiotica. 1988;71:125–51. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crystal D. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. 2nd edn. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slovenko R. Commentary: euphemisms. J Psychiatry Law. 2005;33:533–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfaff K, Raymond G, Johnson M. Metaphor in using and understanding euphemism and dysphemism. Appl Psycholinguist. 1997;18:59–83. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barringer C. Speaking of incest: it's not enough to say the word. Fem Psychol. 1992;2:183–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGlone M, Batchelor J. Looking out for number one: euphemism and face. J Commun. 2003;53:251–64. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slabbert S, Finlayson R. Code-switching. in a South African township. In: Mesthrie R, editor. Language in South Africa. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 235–49. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valdes-Fallis G. Code-switching among bilingual Mexican American women: towards and understanding of sex-related language alternation. Int J Soc Lang. 1978;17:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A. Integrating gender based violence and HIV risk reduction intervention for South African men: results of a quasi-experimental field trial. Prev Sci. 2009;10:260–9. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0129-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman SR, Bolyard M, Mateau-Gelabert P, et al. Some data-driven reflections on priorities in AIDS network research. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:641–51. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mesthrie R. Language in South Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Statistics South Africa. Population Census 2001. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-02-13/Report-03-02-132001.pdf. Accessed: January 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hibbert L. Globalization, the African renaissance, and the role of English. Int J Soc Lang. 2004;170:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverman E. Anthropology and circumcision. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2004;33:419–45. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marck J. Aspects of male circumcision in subequatorial African culture history. Health Transit Rev. 1997;7:337–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crosse-Upcott ARW. Male circumcision among the Ngindo. J R Anthropol Inst. 1959;89:169–89. [Google Scholar]

- 38.La Fontaine JS. Initiation. Manchester: Manchester University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heald S. The ritual use of violence: circumcision among the Gisu of Uganda. In: Riches D, editor. The Anthropology of Violence. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1986. pp. 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- 40.La Fontaine JS. Tribalism among the Gisu. In: Gulliver PH, editor. Tradition and Transition in East Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California; 1969. pp. 177–92. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mager AK. Gender and the Making of a South African Bantustan. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cadwell JC, Cadwell P. High fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Sci Am. 1990;262:225–62. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0590-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schensul S, Schensul J, LeCompte M. Essential Ethnographic Methods: Observations, Interviews, and Questionnaires. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.D'Andrade R. The Development of Cognitive Anthropology. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borgatti S. Anthropac 4.0. Natick, MA: Analytic Technologies; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith J. Using ANTHROPAC 3.5 and a spreadsheet to compute a free-list salience index. Cult Anthropol Methods J. 1993;5:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weller SC, Romney AK. Systematic Data Collection. Qualitative Research Methods Series 10. New York: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romney A, Weller S, Batchelder W. Culture as consensus: a theory of culture and informant accuracy. Am Anthropol. 1986;88:313–38. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skordis J, Welch M. Comparing alternative measures of household income: evidence from the Khayelitsha/Mitchell's plain survey. Dev South Afr. 2004;21:461–81. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Busgeeth K, Rivett U. The use of spatial information system in the management of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Int J Health Geogr. 2004;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalichman S, Simbayi L, Kagee A, et al. Associations of poverty, substance use, and HIV transmission risk behaviors in three South African communities. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1641–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marston C. Gendered communication among young people in Mexico: implications for sexual health interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:445–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Groce N, Mawar N, Macnamara M. Inclusion of AIDS educational messages in rites of passage ceremonies: reaching young people in tribal communities. Cult Health Sex. 2006;8:303–15. doi: 10.1080/13691050600772810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanders J, Robinson W. Talking and not talking about sex: male and female vocabularies. J Commun. 1979;29:22–30. [Google Scholar]