Abstract

Promoting marriage, especially among low-income single mothers with children, is increasingly viewed as a promising public policy strategy for improving developmental outcomes for disadvantaged children. Previous research suggests, however, that children’s academic achievement either does not improve or declines when single mothers marry. In this paper, we argue that previous research may understate the benefits of mothers’ marriages to children from single-parent families because (1) the short-term and long-term developmental consequences of marriage are not adequately distinguished and (2) child and family contexts in which marriage is likely to confer developmental advantages are not differentiated from those that do not. Using multiple waves of data from the ECLS-K, we find that single mothers’ marriages are associated with modest but statistically significant improvements in their children’s academic achievement trajectories. However, only children from more advantaged single-parent families benefit from their mothers’ marriage.

INTRODUCTION

Does children’s academic achievement improve when single mothers marry? Promoting marriage is increasingly viewed as an important public policy strategy for improving academic achievement for children in female-headed households (Horn 2002; Horn, Blankenhorn, and Pearlstein 1999). An emerging body of research suggests, however, that children’s academic achievement either does not improve or declines when single mothers marry. Children with single mothers who marry often score no better on academic achievement and cognitive assessments than do children from stable single-parent families (Jeynes 1998 and 2000). Moreover, the transition from living in a single-parent family to living in a married two-parent family is frequently associated with declines in child well-being and academic achievement (Brown 2006; Coleman, Ganong, and Fine 2000; Fomby and Cherlin 2007).

Current research may, however, underestimate the developmental benefits of parental marriage to children from single-parent families for two main reasons. First, most studies neglect the potential for parental marriage to have varying effects on child development over time.1 Marital transitions are likely to have deleterious short-term effects on child development and behavior because parental marriage tends to disrupt family roles and routines. Over time, however, marriage may have increasing, positive effects on children as parents and children adapt to new roles and routines in the family and increased family economic resources enable parents to invest more in their children. Failure to consider how the effects of parental marriage change over time is likely to understate the long-term benefits of marriage, especially if the effects of marriage on children are examined only over a short time interval immediately after a parent’s transition to marriage (e.g., Heard 2007; Brown 2006).

Second, most studies do not differentiate between those child and family contexts in which marriage is likely to confer developmental advantages and those which do not. Past research focuses largely on estimating the average “net” or “conditional” effect of parents’ marriage on their children’s development (e.g., Acs 2007; Brown 2006; Foster and Kalil 2007; Heard 2007). Foster and Kalil (2007) and Acs (2007), for example, estimate the effects of family structure transitions on children’s development, both with and without statistical controls for child, parent, and family characteristics that may confound estimated effects of parental marriage on children’s development. Less effort has been given to understanding how these characteristics may moderate the effects of marriage or examining the processes by which marriage may influence children’s academic achievement (e.g., through increasing family income, increasing human capital in the family, or increasing investment in the child). The impact of parents’ marriage on their children’s academic achievement is, however, likely to depend on a child’s characteristics and behavior, a family’s resources and characteristics prior to marriage, and a family’s characteristics and dynamics after the marital union. Parental marital transitions are likely to be beneficial to children’s development in some child and family contexts, to have no effect in others, and to be detrimental to children’s development in yet others.

An accurate accounting of the developmental consequences of parental marriage for children originating in families headed by single mothers can only occur if: (1) the short-term effects of marital transitions are distinguished from the long-term consequences of marriage and (2) the effects of parental marriage on child development are allowed to vary by child, parent, and family characteristics. We use multiple waves of data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K) and hierarchical linear growth modeling to test hypotheses about temporal change in the association between single mothers’ marriage and children’s academic achievement trajectories and about child, parent, and family characteristics that are likely to influence the magnitude and direction of the association between parental marriage and children’s academic achievement.

LINKAGES BETWEEN PARENTAL MARRIAGE AND CHILDREN’S ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT TRAJECTORIES

Temporal Influences on the Association between Parental Marriage and Children’s Academic Achievement

Parental marriage potentially confers several long-term advantages on children from formerly single-parent families. Marriage increases financial resources (Page and Stevens 2004) and substantially reduces poverty, welfare receipt, and economic hardship (Lichter, Roempke Graefe, and Brown 2003). The improved financial circumstances of many families after marriage (Lichter, Roempke Graefe, and Brown 2003; Page and Stevens 2004) and the active interest many non-biological fathers show in their spouses’ children (Marsiglio 2004; Sandberg and Hofferth 2001) may lead to greater investments of time and resources in children (Hofferth and Anderson 2003), although mother-child interaction tends to decline after marriage (Juby, Marcil-Gratton, and Le Bourdais 2001). Because two parents typically have more available time to spend with and resources to dedicate to children, two-parent families may be better in the long run at fostering child development and monitoring child behavior than single parent families (Hetherington 1972 and 1979).

Yet marital transitions, even when presumptively positive in the long run, can also create short-term stress and conflict in a child’s family life. New marriages increase family conflict (Juby, Marcil-Gratton, and Le Bourdais 2001). Marital transitions are emotionally stressful events for children because parental marriage changes children’s routines, disrupts children’s expectations about family life, and alters children’s relationships to key parental figures (Hetherington, Cox, and Cox 1978; Wallerstein and Kelly 1980). Overall, marital transitions tend to undermine child well-being in the short-term (Cherlin et al. 1991; DeLeire and Kalil 2002; Wu and Thomson 2001) because the stress of family change can hinder normal developmental transitions among children (Hao and Xie 2001; Hill, Yeung, and Duncan. 2001; Wu and Martinson 1993).

The developmental benefits of parental marriage for children are likely to increase over time because the advantages of parental marriage tend to cumulate (Bachman, Coley, and Chase-Lansdale 2009). The benefits of parental marriage to children may not be immediately evident, both because it often takes time for parents to translate their newfound economic advantages into more resources and a better environment for their children and because it takes time for additional resources and an improved environment to impact children’s academic achievement. The potential developmental advantages conferred by reduced economic hardship, more effective socialization and social control, and increased parental investment in children are likely to cumulate as the length of time from a marital union increases. Initially, the developmental benefits accruing to children from their mothers’ marriage may be negligible. However, as the duration of a marriage increases, cumulative processes may lead to escalating, positive developmental changes for children.

The adverse effects of parental marriage on children’s development, by contrast, are likely to decline as the length of time from a marital transition increases. Roles in a family establish normative expectations and informal sanctions that guide individual and family life (Elder 1999). Marital transitions, like severe income losses or other stressful events, often entail a severe disruption of habit, which can undermine and disrupt family roles and routines and create stress and conflict in a family (Hetherington, Cox, and Cox 1978; Wallerstein and Kelly 1980). However, the conflict and stress created by changing roles and routines in a new family are likely to recede over time as family members adapt to new roles and establish new routines.

The effect of marriage on children’s academic achievement is, therefore, likely to change as the duration of a marriage increases. In the short term, marriage is likely to be negatively associated with children’s achievement as the disruptive effects of a marital transition on family roles and routines outweigh the social and economic benefits of marriage. In the long term, however, the social and economic advantages of marriage are likely to outweigh the negative effects of marriage on family stress and conflict.

Hypothesis 1: Marriage will have negative effects on children’s academic achievement in the short-term and increasingly positive effects in the long-term.

Child and Family Influences on the Association between Parental Marriage and Children’s Academic Achievement

The effect of parental marriage on children’s academic achievement is likely to depend not only on the duration of a marriage, but also on the characteristics of the child and the child’s family prior to and after the marital transition. Child and family characteristics may moderate the effect of parental marriage on children’s development both because children’s behavior can affect family dynamics and because the potential benefits of a two-parent family structure relative to a single-parent family structure depend on the characteristics of a child’s parents and family before and after the marital union.

Transactional perspectives on child development emphasize that not only do parent and family influences affect children’s behavior and development, but children’s behavior actively influences family dynamics (Sameroff 1975; Sameroff and Chandler 1975). Family systems theory, for example, posits reciprocal relations within families in which interactions between parents and children are characterized by an ongoing cycle of action and reaction feeding back to produce further reactions (Cox and Paley 1997; Minuchin 1985). Recent research finds that child behavior problems have an important influence on family and marital dynamics. Children’s externalizing behavior problems are associated with lower parent-child relationship quality, especially in stepparent families (O’Connor et al. 2006), and with increases in marital discord and mothers’ hostility toward children in the family (Richmond and Stocker 2008). Adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behavior problems are associated with increases in marital discord, parent conflict about child rearing practices, and marital dissatisfaction, which in turn tend to intensify adolescent maladjustment (Cui, Donnellan, and Conger 2007; Jenkins et al. 2005). Consequently, we hypothesize that children with more behavior problems will benefit less from their mothers’ marriage than will children with fewer behavior problems, both because their behavioral problems are likely to increase conflict and stress in the new family and because such children are likely to have greater difficulty adapting to these changes in the family.

Hypothesis 2: Parental marriage will have a weaker effect on children’s academic achievement in families in which the child exhibits internalizing or externalizing behavior problems.

Economic deprivation and parental investment perspectives on child development emphasize the negative effects that economic hardship and low parental investments of time and resources in children have on development. From the economic deprivation perspective, parental marriage is likely to improve cognitive outcomes for children because two-parent families tend to be better equipped financially to provide children with the resources and environment they need to develop properly. Marriage increases financial resources (Page and Stevens 2004) and substantially reduces poverty and welfare receipt (Lichter, Roempke Graefe, and Brown 2003). On average, children raised in stepfamilies have similar family socioeconomic resources to children raised in married two-biological parent families (Biblarz and Raftery 1999; Mulkey, Crain, and Harrington 1992).

From the economic deprivation perspective, the benefits of parental marriage for children’s academic achievement are likely to depend on both the level of deprivation in the family prior to the marital union and how family economic well-being changes after the union. Specifically, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3: Children from more economically deprived single-parent families will benefit more academically from their mother’s marriage than will children from more economically advantaged single-parent families.

Hypothesis 4: The extent to which children from single-parent families will benefit academically from their mother’s marriage will depend on the degree to which family economic resources increase after the marital union.

The investment-in-children perspective emphasizes the positive influence that parental investments in children have on children’s cognitive development. Parent investments can take the form of monetary investments used to purchase items or activities for children, such as books or trips to a museum, or the form of time investments that involve parents spending time with children in joint activities, such as reading books or playing games. The parent investment model suggests that it is by restricting parents’ abilities to invest money and/or time in their children — and thereby exposing them to fewer enriching materials and experiences—that single-parent status will affect children’s academic achievement. Indeed, two-parent families have been found to invest more time and resources in their children (Thomson, Hanson, and McLanahan 1994), and greater levels of parental investments in their children have been associated with higher levels of children’s academic achievement (Gershoff, Aber, Raver, and Lennon 2007; Guo and Harris 2000; Linver, Brooks-Gunn, and Kohen 2002; Yeung, Linver, and Brooks-Gunn 2002).

From the investment-in-children perspective, the effect of single mother’s marriage on child development is unclear. On one hand, the financial circumstances of families improve after marriage (Lichter, Roempke Graefe, and Brown 2003; Page and Stevens 2004) and in recent cohorts of men many non-biological fathers show an active interest in their spouse’s children and spend time with them (Marsiglio 2004; Sandberg and Hofferth 2001), potentially increasing investments in children. On the other hand, stepparents tend to be disadvantaged in myriad ways (e.g., they are younger, poorer, work less, and have completed fewer years of schooling) (Bernhardt and Goldscheider 2001; Hofferth and Anderson 2003; Manning and Lichter 1996; Sassler and Goldscheider 2004), and patterns of parental investment differ for biological and nonbiological children (Case, Lin, and McLanahan 2000; Dunn and Phillips 1997; Pezzin and Schone 1997), with stepfathers investing less time with their young stepchildren (Hofferth and Anderson 2003) and spending less than biological fathers on the educational expenses of their children (Anderson 2000). Moreover, mothers in new marriages tend to spend less time with their children, potentially reducing the time invested in children (Thomson, Hanson, and McLanahan 1994).

The effects of marriage on children, from an investment-in-children perspective, therefore, are likely to be contingent on the levels of parental investment in the child prior to marriage and how family investment patterns change after the marital union. Consequently, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5: Children from single-parent families with lower investment in children will benefit more academically from their mother’s marriage than will children from higher investment-in-children single-parent families.

Hypothesis 6: The extent to which children from single-parent families will benefit academically from their mother’s marriage will depend on the degree to which family investments in children rise after the marital union.

We include children’s demographic characteristics, specifically their race/ethnicity and their gender, as control variables because of the importance of these characteristics in academic achievement processes. Both reading and math achievement gaps among whites, blacks, and Hispanics and between boys and girls are well established (e.g., Lee, Grigg, and Dion 2007; Lee, Grigg, and Donahue 2007; Liu and Wilson 2009). Studies that have examined differences in children’s experiences of major transitions—such as parents becoming married or divorced—have limited their focus to describing between-group differences in the rate at which children experience these changes, and not on whether the strength of the association between stressors experienced and adjustment varies for boys and girls or for children from different race/ethnic backgrounds (Dubois et al. 1992; DuBoiset al. 1994). As such, little is known about whether there are sex or race/ethnic group differences in how children’s adjustment is influenced by parental marriage. We also include as statistical controls variables indicating whether the mother’s new spouse is the biological father of the child and whether the mother’s marriage was her first. The biological relationship between the mother’s new spouse and child may moderate the effect of marriage on children’s achievement because stepparents have less positive involvement, discipline more harshly, and are more likely to abuse children in the family than residential biological parents (Daly and Wilson 1998), are less involved with their children (Hofferth and Anderson 2003), and have lower quality parent-child relationships (O’Connor, Jenkins, and Rasbash 2006), all of which may negatively impact children’s academic achievement. Similarly, the mother’s previous marital status may moderate the effect of marriage on children’s achievement because marital and partnership instability is associated with poorer child outcomes (e.g., Fomby and Cherlin 2007; Osborne and McLanahan 2007). Given the strong link between disability status and achievement, we have included an indicator of children’s disability status as a control variable in some model specifications

DATA

The ECLS-K is a nationally representative sample of 21,260 children enrolled in 944 Kindergarten programs during the 1998–1999 school year designed to study the development of educational stratification among American school children (West, Denton, and Reaney 2000). The study was developed by the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Sample selection for the ECLS-K involved a dual-frame, multistage sampling design. At the first stage, a national sample of counties and county groups was selected. At the second stage, public schools were selected within the selected counties and county groups from the Common Core of Data (a public school frame) and private schools were selected from the Private School Survey. Finally, an average of 23 kindergartners was selected for participation from each of the sampled schools (West, Denton, and Reaney 2000). Schools participated with a weighted response rate of 74%; among the participating schools, the completion rates were 92% for the children and 89% for the parents.

Because our focus is the effect of single parents’ transitions to marriage on change in their children’s academic performance, we include in our sample only children living with their biological mother in single-parent, female-headed households at the first wave of data collection and who remain living with their biological mothers throughout the study period. For the purposes of this analysis, cohabiting single mothers are classified as single-parent, female-headed households. We exclude from our sample children living in single-parent, male-headed households with their biological father at the first wave both because few children live in these families and because past research finds that male-headed and female-headed single parent families are quite different (Meyer and Garasky 1993). For the small number of families with two children (i.e. twins) in the sample we randomly selected one child from each family. Because of the adverse consequences of multiple marital transitions for children’s well-being (Fomby and Cherlin 2007), we treated the four children with mothers who experienced multiple marital transitions during the study period as non-responding cases in the wave in which the mother experienced her second marriage and in any subsequent waves. The total sample size for our analysis is 2,580 children.

This study uses data from the kindergarten through 5th grade waves of the ECLS-K.2 The ECLS-K collected data at 6 time points in middle childhood: Kindergarten Fall, Kindergarten Spring, 1st Grade Fall, 1st Grade Spring, 3rd Grade Spring, and 5th Grade Spring. In the 1st Grade Fall wave, the ECLS-K only interviewed one-third of the original sample. We deal with missing data from this wave and the other waves in several ways. First, we include information for children for all waves in which they participated. Second, for children who participated in a wave but did not provide information for a specific variable, we use a multiple imputation procedure to impute missing values (Rubin 1987). The estimates we present are based on 10 complete simulated datasets.3

Outcome Measures

We examine two measures of children’s academic achievement: children’s reading and math scores. The ECLS-K reading assessment measures basic skills such as print familiarity, letter recognition, beginning and ending sounds, recognition of common words, decoding multisyllabic words, vocabulary knowledge, and reading comprehension. More emphasis is placed on basic reading skills during the kindergarten and first grade assessments and greater emphasis is placed on comprehension in the third and fifth grade assessments. The mathematics assessment measures conceptual knowledge, procedural knowledge, and problem solving within specific content areas. Areas covered by the math assessment include number sense, properties, and operations; measurement; geometry and spatial sense; data analysis, statistics, and probability; and patterns, algebra, and functions (see Princiotta, Flanagan, and Hausken 2006, for a complete description of the achievement measures in the ECLS-K).

Independent Measures

We include both time-varying and time invariant covariates in our models. Time-varying variables represent a child’s age and change in the mother’s marital status. Age is a continuous variable indicating a child’s age (in years) at the time math and reading assessments were administered. Age for all waves is centered around the age of 5 years, which is the earliest age at which children typically begin kindergarten. Variables representing change in a mother’s marital status are also included in most model specifications. Married is a dichotomous indicator of whether a child’s mother is married at a wave. Years Married is a continuous variable representing the length of the mother’s marriage (in years), with the duration of the marriage computed on the basis of the mother’s marital status at each wave because the ECLS-K does not report the actual date of the mother’s marital union. Table 1 presents means and standard deviations by wave for all time-varying independent variables. At the Kindergarten Fall assessments (wave 1), the average child was 5.62 years old. At the 5th Grade Spring assessments (wave 6), the average child was 11.05 years old. The proportion of children with married mothers increases steadily over the study period, rising from 0 percent (n=0) in the first wave to 22 percent (n=295) in the final wave, as does the duration of these marriages. Overall, the mothers of 636 children married between the first and final waves of data collection.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Time-Varying Covariates, by Wave

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | Wave 5 | Wave 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean | 0.62 | 1.13 | 1.57 | 2.14 | 4.12 | 6.05 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.34 | |

| Married | Mean | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.22 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.000 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.41 | |

| Years Married1 | Mean | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.78 | 1.71 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 1.04 | 1.70 | |

| N | 2,571 | 2,536 | 802 | 2,449 | 2,012 | 1,479 | |

For those children with a married mother at the wave.

The time invariant covariates included in our models represent child, parent, and family characteristics before and after the marital transition. Child measures include variables representing a child’s sex, racial and ethnic background, disability status, and internalizing and externalizing behavior problems prior to marriage. Female is a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not the child is female. White, African American, Hispanic, and Other Race are indicator variables representing a child’s race and ethnicity, with white non-Hispanic the omitted reference category in the models. Children with internalizing and externalizing behavior problems are identified on the basis of teacher-reported scales adapted from the Social Skills Rating System instrument developed by Gresham and Elliot (1990). The internalizing behavior problem scale consists of four items (ranging from 1=never to 4=most of the time) that ask about the presence of anxiety, loneliness, low self-esteem, and sadness in the child. The externalizing scale includes information on acting out behaviors of children and is based on five items that rate the frequency with which a child argues, fights, gets angry, acts impulsively, and disturbs ongoing activities. The scores on both scales are the mean rating on the items included in the scale. Both scales have high reliability, with reliabilities for these scales of 0.90 for externalizing problems and 0.80 for internalizing problems. Because our principal interest is how children with high levels of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems respond to their mother’s marriage, we created three indicator variables from each of these scales: Low Internalizing and Low Externalizing (< 25th percentile each); Moderate Internalizing and Moderate Externalizing (25th-74th percentile each); and High Internalizing and High Externalizing (≥75th percentile each). The low categories from both sets of variables are omitted from the analytic models.4 A dichotomous indicator of children’s Disability Status is included as a control variable in some model specifications.

Family characteristics prior to the mother’s marriage include mother’s marital history, education, family income, and investment in the child. Information on all family characteristics prior to the marital transition is from the Fall kindergarten wave. Mother Previously Married is a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not the child’s mother was previously married (1=divorced, widowed, or legally separated; 0=never married). High School Graduate, Some College, and College Graduate are indicator variables representing the mother’s level of educational attainment at kindergarten, with High School Dropouts the omitted reference category. Family Income is a continuous measure indicating the family’s income (in thousands of dollars) at kindergarten. We include two measures of parental investment in the child, one representing parents’ investment of time in Learning Support activities, and a second representing parents’ investment of both time and money in Enriching Activities with the Child. Learning support is a scale created from parents’ “yes” (1) or “no” (0) responses to 5 variables from the HOME Scale (Caldwell and Bradley 1984) that reflect activities parents might engage in the home to encourage their children’s learning, namely: reading books, talking about science or nature, telling stories, playing puzzles or games, and visiting the library. The scale has modest internal reliability across the waves (KR20 = .51–.57). The Enriching Activities with the Child scale is created by summing parents’ “yes” (1) or “no” (0) responses to 5 additional variables from the HOME Scale (Caldwell and Bradley 1984). The items in this scale involve parents’ investment of time by engaging in educational or entertainment activities with their child outside the home (e.g., visiting a library, visiting a zoo, aquarium, or petting farm). The summed composite ranges from 0 to 5. Reliability of this composite is low across waves (KR20 = .43–.45). Although the reliabilities of both investment scales are low, we retained them because the HOME scale is the standard in the field for measuring parent investment and resources and because there are no alternative measures of investment in the ECLS-K dataset.

Family characteristics after the marital transition include the new spouse’s biological relationship to the child, educational attainment and measures representing how family income and parental investment in the child change after the marital union. Biological Father is a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not the mother’s new spouse is the biological father of the child. The highest level of the New Father’s Education is coded into a set of dummy variables similar to those described above for mother’s education. Change in Family Income represents the difference (in thousands of dollars) between mean family income after the marital union and family income in kindergarten. Family income after kindergarten is only available as a grouped frequency. Mean family income was computed by assigning children’s families the midpoint value of their income category and computing the average inflation-adjusted income of the family for all waves in which the child’s mother was married. Because the width of higher income categories is greater than the width of lower income categories, this measure is less sensitive to change in family income at upper income levels.5 Change in Parental Learning Support indicates the difference between the mean score on the learning support scale after the marital union and the score reported in kindergarten. Change in Parental Enriching Activities with the Child indicates the difference between the score on the parent enriching activities with the child scale after the marital union and the score reported in kindergarten. In some preliminary model specifications (not presented), we included variables measuring the number of children in the family, whether the mother was ever married to the biological father, and the length of time since the mothers’ last marriage to capture resource dilution, family instability, and father involvement in the family. We did not include these variables in our final model specifications because these measures were not associated with the developmental benefits of marriage.

Table 2 presents weighted means and standard errors for these time-invariant independent variables for the group of children with mothers who married during the study period and the group of children with mothers who did not marry. Because the effects of marriage on children’s academic achievement in our models are estimated based on information about change in the developmental trajectories of those children who experienced a parental marital transition, we focus on the characteristics of this group and how they differ from those of children with a single-mother who did not marry. Approximately one-half of the children whose mothers married are female and 44% are white non-Hispanic. One-third of children with mothers who married have high levels of internalizing behavior problems prior to the marriage, 35% have high levels of externalizing behavior problems, and 16% report a disability. Three-fifths of the mothers were divorced, widowed, or legally separated. Regarding education, 12% of mothers and 18% of new fathers were college graduates. Nearly one-quarter of the mothers married (or remarried) the biological father of the child. Mean family income prior to the mother’s marriage was $39,000 and increased by nearly $10,000 after the marital transition. On average, parental investments learning support and enriching activities did not change much after mothers married. At the beginning of the study (i.e., prior to marriage), children with mothers who married experienced levels of parent investments in children and had levels of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems that were similar to those for children with mothers who did not marry. Mothers who married were, however, significantly more likely to be divorced, widowed, or legally separated, to have graduated college, and to have had higher average incomes prior to marriage than mothers who did not marry. White and Hispanic children’s mothers were more likely to marry and black children’s mothers were less likely to marry. Although restricting our sample to children whose mothers have already been “selected” into single parenthood diminishes the observed (and, presumably, the unobserved) differences between married and unmarried families, it does not eliminate these differences. Consequently, we include covariates for race, mother’s marital history, and family socioeconomic status in our models.

Table 2.

Weighted Means and Standard Errors for Time Invariant Covariates, by Child’s Mother’s Marital Status During the Study Period

| Mother Became Married During Study | Mother Did Not Marry During Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Error | Mean | Std. Error | |

| Child Variables | ||||

| Female | 0.51 | 0.022 | 0.49 | 0.012 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 0.44*** | 0.037 | 0.35 | 0.012 |

| African-American | 0.25*** | 0.033 | 0.40 | 0.012 |

| Hispanic | 0.20* | 0.046 | 0.18 | 0.010 |

| Other race | 0.10 | 0.070 | 0.06 | 0.005 |

| Behavior Problems | ||||

| Internalizing Behavior Problems | ||||

| Low (1st-25th percentile) | 0.38 | 0.042 | 0.42 | 0.012 |

| Moderate (26th-75th percentile) | 0.29 | 0.054 | 0.30 | 0.012 |

| High (76th-100th percentile) | 0.33 | 0.022 | 0.29 | 0.011 |

| Externalizing Behavior Problems | ||||

| Low (1st-25th percentile) | 0.21 | 0.032 | 0.22 | 0.010 |

| Moderate (26th-75th percentile) | 0.41 | 0.116 | 0.41 | 0.012 |

| High (76th-100th percentile) | 0.35 | 0.021 | 0.36 | 0.012 |

| Disabled | 0.16 | 0.016 | 0.15 | 0.009 |

| Family Variables (prior to marriage) | ||||

| Mother previously married | 0.59*** | 0.021 | 0.37 | 0.012 |

| Mother’s Education | ||||

| High school graduate or less | 0.58** | 0.021 | 0.64 | 0.012 |

| Some college | 0.30 | 0.020 | 0.27 | 0.011 |

| College graduate | 0.12* | 0.014 | 0.09 | 0.007 |

| Income in ($1,000) | 39.03** | 3.005 | 31.01 | 1.588 |

| Parental investment in the child | ||||

| Learning support | 2.54 | 0.024 | 2.51 | 0.014 |

| Enriching activities with the child | 2.00 | 0.063 | 1.94 | 0.037 |

| Family Variables (after marriage) | ||||

| Biological father | 0.23 | 0.018 | -- | -- |

| New father’s education | ||||

| High school graduate or less | 0.54 | 0.023 | -- | -- |

| Some college | 0.18 | 0.016 | -- | -- |

| College graduate | 0.18 | 0.016 | -- | -- |

| Change in income after marriage (in $1,000) | 9.44 | 2.871 | -- | -- |

| Change in parental investment in child after marriage | ||||

| Change in learning support after marriage | −0.16 | 0.034 | -- | -- |

| Change in enriching activities with the child after marriage | −0.01 | 0.066 | -- | -- |

| N | 636 | 1,944 | ||

Note: Significant tests indicate differences between children with mother’s who and did not marry during the study period.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

MODELS AND ESTIMATES

We estimate the effect of marriage on reading and math achievement trajectories during early and middle childhood using multilevel growth models (Bryk and Raudenbush 1992). Models were estimated using sampling weights that adjust for the unequal probabilities of selection for children in the ECLS-K. In these models, time points are nested within children. Multilevel growth models can be used to estimate the effect of within-individual (i.e., within-child) change in parental marital status on change in children’s academic achievement trajectories. By estimating the effect over time, multilevel growth models make it possible to assess whether changes in children’s developmental trajectories coincided with parent marital transitions and whether the effect of marriage on achievement changes over time.

The estimated coefficients for parental marriage in these models indicate how the academic achievement trajectories of children who actually experience a parental marital transition change after marriage. Consequently, the growth modeling approach estimates the effect of the treatment – in this case, marriage – on the treated (i.e, children with mothers who marry), or the so-called average treatment effect on the treated (ATET). The ATET represents how the developmental trajectories for children whose mothers marry between kindergarten and 5th grade would be expected to differ on average if their mothers had not married. If children with mothers who marry between kindergarten and 5th grade are affected differently by marriage than children from other types of single-mother families (e.g., those who marry before kindergarten or do not marry between kindergarten and 5th grade), the ATET will be an imperfect indicator of the average treatment effect in the population (ATE).

Presumably, single mothers’ decisions to marry or remarry are based, at least in part, on their perceptions of the benefits of marriage to them and their children. The developmental benefits of parental marriage to the average child in a single-parent family (ATE) may, therefore, be lower than the estimated effects of marriage derived from these models (ATET). Ideally, an instrumental variables (IV) approach would be implemented to account for the endogeneity of the parental marriage variable. Unfortunately, this is not feasible because the ECLS-K collects limited information about parental background characteristics, and the information that is collected about parents (e.g., education, employment, income, welfare use, school involvement, and parenting practices) is likely to be associated with both the chances of mothers getting married and their children’s academic achievement. Because all children in our sample begin the study living in single-parent families (i.e., their mothers have already “chosen” a single-parent family structure), this form of endogeneity bias is most likely much smaller than in studies that compare children’s academic achievement in single-parent and married-parent family structures (e.g., Amato 2005; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994).

Although not reported here, we also estimated three-level growth models in which time points are nested within children and children are nested within schools in order to account for the clustering of children within schools in the ECLS-K sampling design. The findings for these analyses are generally quite similar to those presented here. For example, the estimated coefficients for the time-independent effect of mothers’ marriage on children’s reading and math trajectories6 are remarkably similar in the two- and three-level models. However, the reliabilities of the random level-2 coefficients for the marriage variables in the three-level models are very low, with reliabilities for the time-independent marriage effect of 0.021 for reading and 0.044 for mathematics. This is most likely due to the small number of children per school (2,580 children in 763 schools). Moreover, the level-3 variance components indicate that the estimated effect of marriage on children’s academic achievement does not vary significantly across schools, either for reading (μ=4.30, p>0.500) or for math (μ=4.15, p>0.175).7 For these reasons, we present the more robust results from the two-level models.

BASELINE GROWTH IN ACHIEVEMENT

Specification

We estimate baseline learning rates using unconditional growth models that describe children’s reading and mathematics achievement trajectories between kindergarten and 5th grade. Because we have information on children’s achievement and family structure at six time points, it is possible to estimate both linear and quadratic growth functions. Our exploratory analyses indicate that children’s academic achievement over this period is best captured by a quadratic growth function. Consequently, we only present estimates from quadratic growth models.

Using the notation developed by Bryk and Raudenbush (1992), our baseline model is:

Level 1 Model:

| (1) |

Level 2 Model:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

In this model, Yti represents the IRT reading or mathematics achievement score of child i at wave t and Age represents child i’s age at wave t. Therefore, πoi represents the estimated reading or math level for a child who is 5 years old, π1i represents the linear component of growth for reading or mathematics achievement between the kindergarten and 5th grade assessments, π2i represents the quadratic component of growth over this period, and eti is a within-child (i.e., over time) error term. The Level 2 (i.e., between-subject) model includes subject-level random error terms r0i for the achievement intercept, r1i for the linear component of the achievement slope, and r2i for the quadratic component of the achievement slope. This baseline model provides an estimate of the unconditional mean level of reading and math achievement at the beginning of kindergarten and average rates of change in learning between kindergarten and 5th grade for children in single-parent families at the beginning of kindergarten.

Estimates and Interpretation

Table 3 presents estimates of the fixed and random effects from Model 1. The estimated coefficients for the fixed effects in the upper-half of Table 3 indicate that children’s learning rates increase during early middle childhood and level off during late middle childhood. At age 5, the estimated mean math score for children is 5.99 and the estimated mean reading score is 7.49. The large positive values for the linear component of the age slope for math (π1ij=23.55) and reading (π1ij=29.96) and the negative values for the quadratic component of the age slope for math (π2ij=−1.16) and reading (π2ij=−1.55) reveal that between the ages of 5 and 9 the average child’s reading and math score rapidly increases. However, by age 9 the rate of increase begins to slow, and by age 11 improvements in reading and mathematics achievement are much more modest than in early middle childhood. Overall, the growth curve for reading is slightly steeper and tapers off somewhat later and more slowly than the growth curve for mathematics. The random effects presented in the lower-half of Table 3 indicate that patterns of growth vary significantly among children. Both initial levels of achievement (Math: χ2=3,773, p<0.001; Reading: χ2=3,876, p<0.001) and the linear (Math: χ2=4,601, p<0.001; Reading: χ2=4,764, p<0.001) and quadratic components (Math: χ2=3,715, p<0.001; Reading: χ2=3,863, p<0.001) of growth vary among children. Estimated reliabilities for the reading and math intercepts and linear and quadratic age slope components are, however, relatively low, ranging from 0.26 for the quadratic components of these learning curves to 0.40 for the linear components of these curves.8

Table 3.

Estimated Coefficients for Quadratic Growth Model of Math and Reading Achievement Scores

| Fixed Effects | Math | Reading | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. error | t ratio | p | Coef. | Std. error | t ratio | p | |

| Intercept, πoij | 5.99 | 0.21 | 27.90 | <0.001 | 7.49 | 0.31 | 24.14 | <0.001 |

| Age, π1ij | 23.55 | 0.22 | 107.22 | <0.001 | 29.96 | 0.31 | 96.59 | <0.001 |

| Age2, π2ij | −1.16 | 0.03 | −38.76 | <0.001 | −1.55 | 0.04 | −37.43 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Random Effects | Variance Comp. | df | χ2 | p | Variance Comp. | df | χ2 | p |

|

| ||||||||

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| eti | 38.21 | 69.39 | ||||||

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Intercept, πoij | 34.68 | 2,524 | 3,773.39 | <0.001 | 75.10 | 2,463 | 3,875.85 | <0.001 |

| Age, π1ij | 53.25 | 2,524 | 4,601.01 | <0.001 | 111.68 | 2,463 | 4,764.18 | <0.001 |

| Age2, π2ij | 0.65 | 2,524 | 3,714.85 | <0.001 | 1.37 | 2,463 | 3,863.45 | <0.001 |

TIME-INDEPENDENT MARRIAGE EFFECTS

Our baseline model captured mean unconditional reading and math achievement trajectories for children living in families headed by single mothers at the beginning of the study period. In this next set of models, we examine whether changes in single mothers’ marital status tend to coincide with changes in children’s learning rates. Children’s developmental paths can be influenced by parental marriage in a number of different ways. For example, parental marriage can have an unchanging effect on children’s development, shifting the height of a child’s learning curve by a similar amount regardless of the length of time since the marital transition. Alternatively, parental marriage can have time dependent effects on development, shifting the height and slope of a child’s learning curve by different amounts depending on the duration of the marriage. In our second model, we evaluate whether parental marital transitions coincide with unchanging positive or negative changes in children’s developmental trajectories. Earlier research, which has typically examined the effects of mothers’ transitions to marriage over significantly shorter time periods, found that parental marriage had no effect or a modest negative effect on children’s development (e.g. Heard 2007; Jeynes 1998 and 2000). Recently, Acs (2007), using a 12-year observation period to study the effects of parental marriage on children’s cognitive development, found small, positive effects of parental marriage on children.

Specification

We estimate the unchanging effects of parental marriage on children’s developmental trajectories by incorporating a single time-varying covariate representing change in a child’s mother’s marital status into the Level 1 equation.

Level 1 Model:

| (5) |

Level 2 Model:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

At Level 1, πoi still represents the estimated reading or math score for a 5 year old child living in a family headed by a single mother. The interpretation of π1i and π2i change slightly in this model, π1i and π2i now represent, respectively, the linear and quadratic components of growth for children in female-headed families. π3ij represents the mean change in children’s reading and math trajectories after their mother’s marital transition. If π3ij is negative, parental marriage tends to coincide with declines in children’s learning rates. If π3ij is positive, single mothers’ marriage tends to coincide with improvements in children’s learning rates.

Estimates and Interpretation

Table 4 presents the estimated coefficients from this model. Consistent with earlier research, we find that the time-independent effects of marriage on children’s academic achievement are relatively modest, yet in contrast to studies examining shorter observation periods, our estimates show that when the effects of parental marriage are examined over a longer time period, the overall effect of parental marriage on children’s development is positive. Children’s math achievement trajectories are, on average, 1.24 points higher and children’s reading achievement trajectories are 2.00 points higher after their mothers’ marriage. Because math and reading achievement overall are increasing by 10–20 points annually over most of this period, a 1.24 point increase in math is comparable to 0.75 to 1.5 months of math learning and a 2.0 point increase in reading is comparable to 1.2 to 2.4 months of reading learning.

Table 4.

Estimated Coefficients for Quadratic Growth Model of Math and Reading Achievement Scores with Time-Varying Indicator of Mother’s Marital Status

| Fixed Effects | Math | Reading | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. error | t ratio | p | Coef. | Std. error | t ratio | p | |

| Intercept, πoij | 6.35 | 0.21 | 29.65 | <0.001 | 8.51 | 0.31 | 27.73 | <0.001 |

| Age, π1ij | 23.16 | 0.23 | 98.79 | <0.001 | 29.01 | 0.33 | 88.64 | <0.001 |

| Age2, π2ij | −1.10 | 0.03 | −34.23 | <0.001 | −1.43 | 0.04 | −32.52 | <0.001 |

| Married, π3ij | 1.24 | 0.42 | 2.94 | 0.004 | 2.00 | 0.62 | 3.21 | 0.002 |

|

| ||||||||

| Random Effects | Variance Comp. | df | χ2 | p | Variance Comp. | df | χ2 | p |

|

| ||||||||

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| eti | 35.41 | 63.94 | ||||||

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Intercept, πoij | 32.57 | 492 | 643.68 | <0.001 | 66.98 | 463 | 614.65 | <0.001 |

| Age, π1ij | 56.32 | 492 | 678.56 | <0.001 | 112.56 | 463 | 779.15 | <0.001 |

| Age2, π2ij | 0.71 | 492 | 576.08 | 0.005 | 1.39 | 463 | 749.37 | <0.001 |

| Married, π3ij | 17.82 | 492 | 532.99 | 0.098 | 66.39 | 463 | 554.06 | 0.003 |

Children with lower initial levels of math (but not reading) achievement and lower math and reading learning rates benefit somewhat more from parental marriage. To see this, consider the correlations between the random effects presented in Table 5. At the child level, we see a negative correlation between initial status in math and the effect of marriage (−0.139), suggesting that children with lower initial levels of math achievement benefit somewhat more from their mothers’ marriage. By contrast, we see a positive correlation between initial status in reading (0.088) and the effect of marriage, suggesting that children with lower initial reading levels benefit somewhat less from their mothers’ marriage than children with higher initial levels of reading achievement. The results also indicate that children with lower baseline learning rates benefit more from parental marriage. For both math and reading, there is a negative association between the linear (i.e., positive) component of learning rates and the marriage effect and a positive correlation between the quadratic (i.e., decelerating) component of learning rates and the marriage effect.

Table 5.

Estimated Correlations between Random Effects in Model 2

| Math | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept, πoij | Age, π1ij | Age2, π2ij | Married, π3ij | |

| Intercept, πoij | -- | 0.060 | −0.148 | −0.139 |

| Age, π1ij | 0.060 | -- | −0.905 | −0.216 |

| Age2, π2ij | −0.148 | −0.905 | -- | 0.221 |

| Married, π3ij | −0.139 | −0.216 | 0.221 | -- |

| Reading | ||||

| Intercept, πoij | Age, π1ij | Age2, π2ij | Married, π3ij | |

| Intercept, πoij | -- | −0.144 | −0.121 | 0.088 |

| Age, π1ij | −0.144 | -- | −0.942 | −0.182 |

| Age2, π2ij | −0.121 | −0.942 | -- | 0.122 |

| Married, π3ij | 0.088 | −0.182 | 0.122 | -- |

The random effects estimates in the lower half of Table 4 indicate that the effect of marriage on children’s reading trajectories varies significantly among children (var. = 66.39, χ2=554.1, p = 0.003). However, the variance component for the effect of marriage on children’s mathematics achievement trajectory is only marginally significant (var. = 17.82, χ2=532.99, p = 0.098), possibly because of the low reliability of the random marriage coefficient in the mathematics equation (0.098). The low reliabilities for these coefficients mean that much of the observed variability among children in the effects of mother’s marriage on academic achievement is due to sampling variability that cannot be explained by child- and family-level factors.

TIME-DEPENDENT MARRIAGE EFFECTS

An unchanging effect may not adequately capture the effects of parental marriage on children’s academic achievement trajectories because the effects of parental marriage may change as the duration of a marriage increases. In the short-term, as Hypothesis 1 suggests, parental marriage may have negative consequences for child development because marital transitions can create strain in the family and disrupt family routines and roles. In the long-term, parental marriage may have increasingly positive consequences for children’s development as conflict and stress in the family decline, new routines and roles are defined, and the advantages of increased economic resources and parental investment in children cumulate.

Specification

We estimate the time-dependent effects of parental marriage on children’s developmental trajectories by incorporating into the Level 1 equation two time-varying covariates representing the length of a child’s mother’s marriage. To capture a potentially nonlinear relationship between marital duration and children’s achievement we include both linear and quadratic terms representing the length of the mother’s marriage.9

Level 1 Model:

| (10) |

Level 2 Model:

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

We do not allow the marriage effects in this model to randomly vary because 6 waves of data do not provide us with adequate statistical power to reliably estimate the time-varying random effects of parental marriage.10 At Level 1, πoi still represents the estimated reading or math achievement score for a 5 year old child living in a family headed by a single mother. In this model, π1i and π2i represent respectively, the linear and quadratic components of growth for children in single-parent families and π3ij and π4ij describe how the developmental trajectories of children change after their mothers’ marital transition.

Estimates and Interpretation

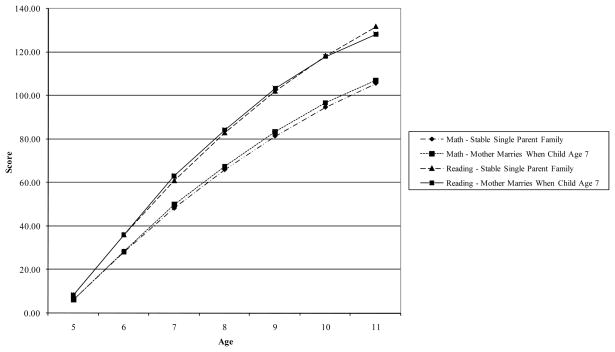

Table 6 presents estimates of the fixed and random effects from this model. Figure 1 displays estimated reading and math achievement trajectories over this period for a hypothetical child living in a stable single-parent family and a hypothetical child living in a family in which the child’s mother marries when the child is age 7 and remains married for the duration of the study period. The estimates in Table 6 show that the effects of marriage on children’s academic achievement change over time. However, contrary to our expectations (Hypothesis 1), parental marriage does not have negative short-term consequences for children’s academic achievement. Rather, for the first several years after a marital transition, parental marriage has gradually increasing, positive effects on children’s reading and math achievement (i.e., the cognitive benefits of parental marriage gradually cumulate during the first several years of marriage). After the first few years of marriage, however, the effects of parental marriage on child development begin to level off. Eventually, the estimated effects of parental marriage on children’s development become negative. Because the children in our sample are entering early adolescence at the point when the estimated effects of mother’s marriage on children’s achievement become negligible or negative, one possible explanation for this finding is that the benefits of mother’s marriage decline during adolescence, a time when parental monitoring of activities is more crucial. Some research finds that stepfathers’ parenting is characterized by low levels of involvement and warmth and little monitoring of activities (Cherlin and Furstenberg 1994; Hetherington and Jodl 1994), which is likely to be more detrimental to child well-being during adolescence (Yuan, Vogt, and Hamilton 2006). Although the absence of short-term negative effects of parental marriage on children’s development are counter to our theoretical expectations, it is consistent with recent research findings that single mothers’ transitions to marriage are not associated with short-term declines in academic, behavioral, and psychological wellbeing (Bachman, Coley, and Chase-Lansdale 2009).

Table 6.

Estimated Coefficients for Quadratic Growth Model of Math and Reading Achievement Scores with Time-Varying Indicator of Mother’s Marital Duration

| Fixed Effects | Math | Reading | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. error | t ratio | p | Coef. | Std. error | t ratio | p | |

| Intercept, πoij | 6.28 | 0.22 | 29.21 | <0.001 | 8.39 | 0.31 | 27.24 | <0.001 |

| Age, π1ij | 23.28 | 0.23 | 100.02 | <0.001 | 29.15 | 0.32 | 89.92 | <0.001 |

| Age2, π2ij | −1.12 | 0.03 | −34.07 | <0.001 | −1.43 | 0.04 | −32.33 | <0.001 |

| Years Married, π3ij | 1.67 | 0.74 | 2.25 | 0.024 | 2.17 | 0.97 | 2.24 | 0.025 |

| Years Married2, π4ij | −0.33 | 0.16 | −2.01 | 0.044 | −0.76 | 0.22 | −3.40 | 0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Random Effects | Variance Comp. | df | χ2 | p | Variance Comp. | df | χ2 | p |

|

| ||||||||

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| eti | 35.96 | 66.02 | ||||||

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Intercept, πoij | 33.34 | 2,310 | 3,463.51 | <0.001 | 67.76 | 2,244 | 3,340.32 | <0.001 |

| Age, π1ij | 56.04 | 2,310 | 4,155.08 | <0.001 | 112.53 | 2,244 | 4,267.91 | <0.001 |

| Age2, π2ij | 0.71 | 2,310 | 3,387.63 | <0.001 | 1.38 | 2,244 | 3,502.56 | <0.001 |

Figure 1.

Mean Predicted Math and Reading Achievement Score Trajectories for Children in Stable Single-Parent Families and in Families in which the Mother Marries When the Child is Age 7: ECLS, Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–1999

Even when we account for the time-varying and nonlinear nature of the relationship between parental marriage and child development, however, the estimated effects of marriage are not large. At the most beneficial points in middle childhood (i.e., the points where the growth curves for children whose mothers married diverge most from their previous trajectory), parental marriage is associated with increases of only a few points in math and reading scores. Given annual learning rates ranging from 10 to 20 points for mathematics and reading over most of this period, this is comparable to one or two months of learning.

UNEQUAL MARRIAGE EFFECTS

The mean effect of parental marriage on children’s reading and mathematics achievement may mask wide variation in children’s returns from marriage. In our final series of models, we test Hypotheses 2–6, which state that children’s characteristics and behavior can affect family dynamics and, ultimately, the benefits of marriage, and that the developmental advantages of a two-parent family structure relative to a single-parent family structure will depend on family economic resources and patterns of investment-in-children before and after marriage. We evaluate these hypotheses by incorporating time-invariant covariates representing child, parent, and family characteristics before and after the marital union into the Level 2 equations for the parental marriage coefficient. In these models, we examine the association between these characteristics and the time-independent effects of parental marriage on children’s reading and math scores. We examine the time-independent effects of parental marriage because with only 6 waves of data from the ECLS-K we do not have adequate statistical power to estimate the influence of these characteristics on the time-dependent effects of parental marriage. For the average child, the time-independent effects of parental marriage are quite similar over much of the learning curve to the time-dependent effects of marriage on children’s academic achievement. Thus, the use of time-independent characteristics is reasonable. Table 7 presents the estimated coefficients from these models.

Table 7.

Estimated Effect of Marriage on Math and Reading Achievement Scores by Selected Child and Family Characteristics

| Child Characteristics Models | Characteristics Before Marriage Models | Characteristics After Marriage Models | Full Models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Math | Reading | Math | Reading | Math | Reading | Math | Reading | |

| Intercept, β30 | 4.44*** | 6.67*** | 0.25 | −2.73 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 3.46* | 0.08 |

| (1.18) | (1.83) | (1.07) | (1.54) | (0.83) | (1.30) | (1.76) | (2.98) | |

| Child Variables | ||||||||

| Female, β31 | −0.97 | 1.84 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −1.27 | 1.61 |

| (0.80) | (1.19) | (0.79) | (1.17) | |||||

| Race | ||||||||

| African-American, β32 | −2.82** | −4.84*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | −2.19* | −3.51* |

| (1.07) | (1.46) | (1.06) | (1.51) | |||||

| Hispanic, β33 | −4.00*** | −4.94** | -- | -- | -- | -- | −2.73* | −2.10 |

| (0.97) | (1.58) | (1.10) | (1.72) | |||||

| Other race, β34 | −3.32* | −5.86** | -- | -- | -- | -- | −2.60* | −4.40* |

| (1.29) | (2.18) | (1.29) | (2.14) | |||||

| Child Behavior | ||||||||

| Internalizing | ||||||||

| Medium, β35 | −0.77 | −2.17 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.53 | −1.50 |

| (1.06) | (1.50) | (1.05) | (1.50) | |||||

| High, β36 | −1.79 | −3.92** | -- | -- | -- | -- | −1.73 | −3.48* |

| (0.99) | (1.45) | (0.99) | (1.41) | |||||

| Externalizing | ||||||||

| Medium, β37 | 0.73 | −0.96 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.52 | −1.48 |

| (1.05) | (1.63) | (1.03) | (1.59) | |||||

| High, β38 | −0.81 | −0.42 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −1.12 | −0.84 |

| (1.13) | (1.68) | (1.13) | (1.66) | |||||

| Disability, β39 | 0.05 | −1.87 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.08 | −1.82 |

| (1.27) | (1.47) | (1.22) | (1.43) | |||||

| Family Variables (prior to marriage) | ||||||||

| Mother previously married, β31 | -- | -- | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.53 | −0.52 | ||

| (0.82) | (1.24) | (0.88) | (1.32) | |||||

| Mother’s education | ||||||||

| High school graduate, β32 | -- | -- | −0.48 | 3.92* | −1.17 | 3.17 | ||

| (1.13) | (1.65) | (1.15) | (1.72) | |||||

| Some college, β33 | -- | -- | 2.27 | 5.71** | -- | -- | 1.42 | 4.58* |

| (1.28) | (1.83) | (1.35) | (2.03) | |||||

| College graduate, β34 | -- | -- | 3.77* | 9.79*** | -- | -- | 2.34 | 7.27** |

| (1.74) | (2.50) | (1.74) | (2.64) | |||||

| Income, β35 | -- | -- | 0.01 | 0.03* | -- | -- | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |||||

| Parental investment in the child | ||||||||

| Learning support, β36 | -- | -- | 0.55 | −0.21 | -- | -- | 0.88 | −0.24 |

| (0.73) | (1.07) | (1.12) | (1.68) | |||||

| Enriching activities with the child, β37 | -- | -- | −0.26 | 0.42 | -- | -- | 0.13 | 1.52* |

| (0.33) | (0.49) | (0.53) | (0.79) | |||||

| Family Variables (after marriage) | ||||||||

| Biological father, β31 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −2.43** | −2.94* | −1.67 | −1.70 |

| (0.90) | (1.25) | (0.98) | (1.26) | |||||

| New father’s education | ||||||||

| High school graduate, β32 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.59 | 1.97 | 1.40 | 1.18 |

| (1.00) | (1.50) | (1.02) | (1.54) | |||||

| Some college, β33 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.61 | 4.15* | 0.37 | 1.56 |

| (1.27) | (1.76) | (1.27) | (1.81) | |||||

| College graduate, β34 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 4.23** | 7.50*** | 2.02 | 2.35 |

| (1.32) | (2.06) | (1.53) | (2.14) | |||||

| Change in income after marriage, β35 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |||||

| Change in parental investment in the child | ||||||||

| Change in learning support after marriage, β36 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.18 | 0.84 | 0.58 | 0.48 |

| (0.65) | (1.01) | (0.95) | (1.45) | |||||

| Change in enriching activities with the child after marriage, β37 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 1.18 |

| (0.27) | (0.42) | (0.43) | (0.65) | |||||

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Child Characteristics

Specification

In the child characteristics model, we examine how children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems influence the estimated effect of marriage on children’s achievement (Hypothesis 2). We also include indicators of children’s sex, race, and disability status as statistical controls because of the well documented associations between these characteristics and children’s achievement.

Level 1 Model:

| (16) |

Level 2 Model:

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

In this model, if β35, β36, β37, and β38 are negative and statistically significant, children with higher levels of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems benefit less from their mothers’ marriage, as Hypothesis 2 suggests. β32, β33, and β34 indicate how the effects of parental marriage for children from racial and ethnic minority groups differ from those for white children. β31 and β39, respectively, reveal how the effects of parental marriage differ for boys and girls and for children with and without disabilities.

Estimates and Interpretation

The estimates in Table 7 for the child characteristics model show that the effects of parental marriage vary significantly among children. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, children with high levels of internalizing behavior problems benefit less from their mothers’ marriage. On average, the reading trajectories of children with high levels internalizing behavior increase 4 points less after the mother’s marriage than do the scores for children with low levels of these behaviors. Children’s externalizing behavior problems, by contrast, are not significantly associated with the expected benefits of parental marriage for children’s math and reading achievement. Racial and ethnic minority children also benefit less from their mothers’ marriage. The estimated effects of mother’s marriage on children’s math and reading scores are 2.82 and 4.84 points lower, respectively, for African-American children than they are for white children. Similarly, the estimated effect of parental marriage on Hispanic children’s math and reading scores are 4.00 and 4.94 points lower, respectively, than for white children. The estimated effect of mother’s marriage on children’s achievement is not associated with either children’s disability status or their sex.

Family Characteristics Prior to the Marital Transition

Specification

In the family characteristics before marriage model, we evaluate whether children from less economically advantaged and lower investment-in-children families benefit more from their mother’s marriage (Hypotheses 3 and 5). Specifically, we examine whether the benefits of parental marriage depend on a mother’s educational attainment, income, and investments in her child prior to the marriage. We also include an indicator of whether the child’s mother was previously married in order to control for the negative effects of marital instability on children’s achievement.

| (21) |

In this model, the Family Income and the Parental Investment variables (Learning Support, and Enriching Activities) are grand mean-centered. Therefore, β30 represents the estimated effect of mother’s marriage for the typical child living in a family headed by a never married single mother who dropped out of high school and had average levels of family income and investment in her child. If children from more educationally- and economically-disadvantaged single parent families benefit more from their mothers’ marriage, as economic deprivation theories predict (Hypothesis 3), we would expect β32, β33, β34, and β35 to be negative. Similarly, if children from low investment-in-children families benefit more from parental marriage, as parental investment theories suggest (Hypothesis 5), we would expect β36 and β37 to be negative.

Estimates and Interpretation

The estimates from this model reaffirm that the developmental benefits of parental marriage do not accrue equally to all children. Contrary to our theoretical expectations, however, the benefits of parental marriage accrue primarily to children from single-parent families that are more advantaged in the first place, especially children with highly-educated single mothers. At average levels of family income and parental investment in the child, children with never married mothers who did not complete high school, benefit very little academically from their mothers’ marriage. For these children, their mothers’ marriage has a negligible effect on their math achievement trajectory (β30=0.25, t=0.24, p=0.814) and a negative effect on their reading achievement trajectory (β30=−2.73, t =−1.77, p=0.076). Compared to children whose mothers did not complete high school, the reading gains associated with mother’s marriage are 3.92 points higher for children with mothers who completed high school, 5.71 points higher for children with mothers who attended college, and 9.79 points higher for children whose mothers graduated college. Math learning improvements associated with mother’s marriage are 2.27 and 3.77 points greater for children whose mothers attended college and graduated college, respectively, than they are for children whose mothers did not complete high school. Since math and reading achievement increased by 10–20 points annually over most of this period, the 3.8 point increase in math achievement children with college graduate mothers experience after their mothers’ marriage is comparable to 2.3 to 4.6 months of math learning and the 9.8-point increase in reading they experience after their mothers’ marriage is comparable to 5.9 to 11.8 months of reading learning. Developmental returns from mothers’ marriage are also somewhat greater for children from higher income single-parent families. A thousand dollar higher before-marriage family income is associated with a 0.03 point greater return from mothers’ marriage for children’s reading achievement (t = 2.52, p = 0.012) and 0.01 point greater return for math achievement (t = 1.83, p = 0.067). Conditional on the mother’s education and family income prior to the marital union, developmental returns from marriage are not associated with the level of parental time or material investment in the child prior to marriage or with the mother’s marital history. Given the strong association between education and income, the positive returns from both mothers’ education and income mean that children in more advantaged single-parent families prior to marriage benefit much more from their mothers’ marriage than do children in less advantaged families. We examine how family characteristics after a mother’s marriage influence children’s returns from parental marriage in the next model.

Family Characteristics After the Marital Transition

Specification

In the family characteristics after marriage model, we evaluate whether mother’s marriage has more beneficial effects on children’s academic achievement trajectories when family income and investments in children increase more after the marital transition (Hypotheses 4 and 6). We examine whether the developmental benefits of parental marriage are associated with the new husband’s educational attainment and changes in family income and investments in the child after the marital transition. We include an indicator of whether or not the mother’s new husband is the biological father of the child as a statistical control because of the different roles that biological fathers and stepfathers typically play in families (Cherlin 1978).

| (22) |

In this model, the ΔFamily Income and ΔParental Investment variables (ΔParental Learning Support and ΔParental Enriching Activities with the Child) are grand mean-centered. Therefore, β30 represents the estimated effect of parental marriage for a child with a new stepfather who did not complete high school and that experiences “average” change in family income and investment in the child after the marriage. If the developmental benefits of parental marriage are a function of the socioeconomic advantages of two-parent family structures, we would expect β35, β36, and β37 to be positive. If children with more educated fathers benefit more from their mother’s marriage, we would expect β32, β33, and β34 to be positive.

Estimates and Interpretation

Contrary to our expectation, marriage does not appear to benefit children primarily because of greater family economic resources and increased investments in the child after marriage. Neither change in family income nor change in patterns of time and material investment in the child after marriage are associated with the estimated effect of mothers’ marriage on children’s academic achievement trajectories. However, it is possible that the weak associations between changes in family income and investments in the child and changes in children’s academic achievement trajectories following their mothers’ marriage reflect the imprecision of measures of family income and parental investments in the ECLS-K, which generally measures these factors using categorical rather continuous indicators. Children with more educated new fathers benefit more from their mothers’ marriage and children whose mother’s marry (or remarry) their biological father’s benefit less.

Full Model

In our final model, we include all child, parent, and family characteristics. Results from this model generally parallel those from earlier models, thus we do not discuss them in depth here (see Table 7). Several findings from this model are, however, worth noting. First, even after controlling for differences in family socioeconomic status before and after marriage, racial and ethnic minority children and children with high levels of internalizing behavior problems benefit less from their mothers’ marriage. Second, children from more socioeconomically advantaged single-parent families benefit more from their mothers’ marriage than do children from less advantaged families. Third, the developmental benefits of marriage are not associated with greater family economic resources and increased investments in children after marriage.

Discussion

Promoting marriage, especially among low-income single mothers with children, is increasingly viewed as a promising public policy strategy for improving developmental outcomes for disadvantaged children. Proponents of marriage promotion policies argue that married, two-parent families are better equipped to provide family environments favorable to child development. Children raised in two-parent families, proponents note, are less likely than children raised by single mothers to experience economic hardship (Acs and Nelson 2002; Manning and Lichter 1996) and family instability (Graefe and Lichter 1999; Manning, Smock, and Majumdar 2004; Raley and Wildsmith 2004) and are more likely to benefit from greater family investments in children (Thomson, Hanson, and McLanahan 1994). They score higher in math and reading and have fewer behavior problems (Aughinbaugh, Pierret, and Rothstein 2005; Baydar and Brooks-Gunn 1994; McLanahan 1997; Morrison and Cherlin 1995). In adolescence, they report greater school engagement (Brown 2006) and they are less likely to drop out of high school (Astone and McLanahan 1991; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994).

Critics of marriage promotion policies have argued that parental marriage is unlikely to confer the same advantages to children living with low-income single mothers as it does to children growing up in married, two-biological parent families. These critics note that low-income single mothers are likely to marry men who are themselves disadvantaged on multiple dimensions (Bernhardt and Goldscheider 2001; Hofferth and Anderson 2003; Manning and Lichter 1996; Sassler and Goldscheider 2004) and that these families tend to invest less in their children (Case, Lin, and McLanahan 2000; Dunn and Phillips 1997; Pezzin and Schone 1997) and are more likely to divorce (Juby, Marcil-Gratton, and Le Bourdais 2001). Recent research suggests that single mothers with children who marry do not benefit to the same extent from marriage as do childless women (Williams, Sassler, and Nicholson 2008).

Our findings suggest that parental marriage is unlikely to be a panacea for most children living in families headed by single mothers. Even when we differentiate between the short-term and long-term effects of marriage and examine the impact of marriage over a longer observation period, the estimated effects of parental marriage on the cognitive outcomes of children living in single-parent families are quite modest. On average, mothers’ transitions to marriage coincide with an improvement of only a few points in children’s achievement test scores, the equivalent of one to two months of learning. More importantly, in light of recent policy debates, we find that the developmental benefits of parental marriage accrue almost entirely to children living in more advantaged single-parent families prior to marriage. Racial and ethnic minority children and children with less-educated single mothers benefit very little academically from their mothers’ marriage. For children with single mothers who graduated from college, however, parental marital transitions are associated with notable gains in math and reading skills.