Abstract

The child-care and fertility hypothesis has been in the literature for a long time and is straightforward: As child care becomes more available, affordable, and acceptable, the antinatalist effects of increased female educational attainment and work opportunities decrease. As an increasing number of countries express concern about low fertility, the child-care and fertility hypothesis takes on increased importance. Yet data and statistical limitations have heretofore limited empirical tests of the hypothesis. Using rich longitudinal data and appropriate statistical methodology, We show that increased availability of child care increases completed fertility. Moreover, this positive effect of child-care availability is found at every parity transition. We discuss the generalizability of these results to other settings and their broader importance for understanding variation and trends in low fertility.

Over one-half of the global population lives in countries with a total fertility rate below the replacement level of 2.1 births. In other words the average woman has less than one daughter surviving to adulthood, and thus the population is not replacing itself. The decline in the number of countries with high fertility rates (and rapidly increasing populations) has been welcomed for a variety of reasons; yet the emergence of below-replacement fertility in more than 60 countries has raised its own set of concerns. First, in many countries fertility rates are so low that, absent massive immigration, they imply dramatic population aging and rapid population decline, which, in turn, are linked to numerous economic and social policy concerns. Additionally, low fertility can have its own inertia. No country has rebounded to replacement-level fertility after having a TFR below 1.5 for a decade or more. Some scholars claim the existence of a low-fertility trap (Lutz and Skirbekk 2005), whereby the society accepts and young adults expect very small families. (See related arguments in Fernández and Fogli 2005; Sacerdote and Feyrer 2008.) even the recent fertility upturn in some countries (Goldstein, Sobotka, and Jasilioniene 2009) leaves those countries well below the replacement level.

Concern over low fertility is not new. In 1937 (p. 290; 1997, p. 612), Kingsley Davis argued that effective birth control and the exigencies of industrial and postindustrial economies produced a “ripening incongruity between our reproductive system (the family) and the rest of modern social organization.” Davis argued that this incongruity was fundamental to modern societies. Of course, the increases in fertility in Europe and North America after World War II dampened concerns about low fertility and Davis’s incongruity concerns seemed baseless, especially in the United States where the baby boom was large and the TFR has been at or near replacement levels for the past 30 years. In contrast, many countries in Europe (e.g., Austria, Germany, Italy, and Spain) and in Asia (e.g., Japan, South Korea, Singapore) have been experiencing very low fertility (TFRs of 1.4 or below) for a decade or more, and some commentators (e.g., Demeny 2003; Caldwell and Schindlmayr 2003; Reher 2007) have echoed Davis’s incongruity, arguing that low fertility seems inevitable in economically advanced societies.

In this article we argue that institutional arrangements can reduce this incongruity. We focus on the role of child-care availability in reducing the conflict between work and family. In industrial and postindustrial societies most women intend to bear two children. However, it is difficult for mothers of young children to be in the paid labor force. It is usually impossible to bring a very young child to the workplace and the child cannot be left unattended. Many respond to the incongruity between work and family demands by postponing childbearing and subsequently forgoing additional births. At the individual (micro) level this has led to the well-known negative relationship between female labor force participation and fertility. At the macro level, the result has been very low fertility levels in numerous countries as women’s fertility has fallen well short of their intentions (see Morgan 2003). The availability of centers that care for children during the hours when their mothers are working and commuting should have pronatalist effects—it should allow women greater opportunity to combine paid work and childbearing. Many policy discussions treat this claim as received truth. But empirical support for this claim has been lacking and herein lies the import of our research.

Using high-quality data from Norway and appropriate statistical modeling techniques, Rindfuss and colleagues (2007) showed that increased availability of child-care centers leads to a younger age at first birth. Using these same data and approach, we show here that high-quality, affordable, worker-friendly child care leads to higher levels of childbearing. Moreover, this effect is evident at every parity transition and is substantial. Our estimates imply that moving from having no child-care slots available for pre-school-age children to having slots available for 60 percent of pre-school children leads the average woman to have between 0.5 and 0.7 more children. For countries struggling with the ramifications of very low fertility, increases of this magnitude would be sufficient to approximate replacement-level fertility.

Background: Changes in education and work and their relationship to childbearing

Childbearing and childrearing now occur in a social and economic landscape markedly changed from that of half a century ago. Consider education first. The proportion of the population completing secondary school and going to tertiary education has more than doubled in the past 50 years in most economically advanced countries, and this increase has been much steeper for women than for men. Women are now more likely than men to complete university education (Schofer and Meyer 2005; UNESCO 2009). This more rapid educational increase for women has been linked to a number of factors including changes in family structures and women’s increasing incentives to obtain market-linked skills (Buchmann and DiPrete 2006). Concomitant with and related to the rise in female educational attainment has been a substantial increase in women’s participation in the paid labor force (e.g., Adsera 2004; Pettit and Hook 2005; Raley et al. 2006; Van der Lippe and Van Dijk 2001). Higher educational attainment produces greater economic returns to employment and is associated with better jobs—those with better benefits, more pleasant working conditions, and higher status. A variety of other factors also contribute to increased female labor force participation, including greater demand for service workers and for workers in female-dominated occupations, increases in age at marriage, and the relative stagnation in male earning power (England and Farkas 1986; Oppenheimer 1994; Pettit and Hook 2005). Further, government attempts at family/work reconciliation may lead to additional increases in female labor force participation (Apps and Rees 2004; Lewis et al. 2008; Mandel and Semyonov 2005; Spiess and Wrohlich 2008; Wrohlich 2008).

Prior to the sharp increase in female labor force participation, developed countries that had the highest fertility level had the lowest proportion of women in the paid labor force, and vice versa. The relationship changed during the 1980s, and by the 1990s the country-level correlation was positive (Ahn and Mira 2002; Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Del Boca 2002; Rindfuss et al. 2003). This anomalous change initially produced disbelief (Kogel 2004), followed by considerable theoretical and empirical speculation about its causes (Bonoli 2008; Bratti and Tatsiramos 2008; Fernandez and Fogli 2007; Hirazawa and Yakita 2009; Matysiak and Vignoli 2008; Morgan and Taylor 2006; Rendall et al. 2009).

A persistent theme in the discussion of the change from a negative to a positive relationship has been differential country-level institutional responses to changes in employment and demographic behavior. The emphasis varies from female employment, the wage gap between employed men and women, and the timing/quantity of childbearing, but the underlying argument is the same: institutions in different countries reacted differently, with the result that these institutional differences have led to quite different outcomes across countries (e.g., Mandel and Semyonov 2005; Rindfuss et al. 2003; Morgan 2003; Stier and Lewin-Epstein 2001). With respect to employment and wages, a central institutional hypothesis involves the facilitating role of paid maternity leaves and the availability of high-quality child care.

The child-care and fertility hypothesis

With its roots in both sociology and economics, the child-care and fertility hypothesis is straightforward. As child care becomes more widely available, affordable, and acceptable, the antinatalist effects of increased female educational attainment and work opportunities decrease. Sociologists focus on the incongruity or incompatibility of the roles of mother and worker (e.g., Davis 1937; Presser and Baldwin 1980; Rindfuss 1991; Stycos and Weller 1967; Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; McDonald 2000; Morgan 2003). In today’s developed economies, with few exceptions, job responsibilities and workplace settings do not permit children to be present on a routine basis. Flextime, part-time, and shift work can ease the role incompatibility, but it remains. Even mothers with young children who work from home typically require help with child care (Gerson 1988). The use of a child-care center while the mother works substantially reduces worker/mother role incompatibilities.

The economic argument involves opportunity costs (Becker 1960; Becker and Lewis 1973; Hotz et al. 1997; Willis 1973). These costs include forgone wages while out of the labor force, along with the loss of skill development that can reduce wage rates upon reentry. Using available child care, whose costs presumably are well below the woman’s wage rate,1 allows mothers to return to work sooner, thus reducing the opportunity costs associated with having children.

The hypothesis that available, affordable, and acceptable child care should increase fertility has long been part of the research literature (c.f. Myrdal 1941), but available evidence has been inconsistent at best and often contrary to theoretical expectations. In the United States, two studies (Blau and Robins 1989; Presser and Baldwin 1980) found tentative support for the hypothesis, while two others did not (Lehrer and Kawasaki 1985; Mason and Kuhlthau 1992). European studies (Andersson, Duvander, and Hank 2004; Del Boca 2002; Hank and Kreyenfeld 2003; Kravdal 1996) also reported mixed results, with none finding strong positive effects of child-care availability. Recent evidence from Norway (Rindfuss et al. 2007) found the expected effect of child-care availability on the timing of the first birth.

In reviewing these inconsistent results, we stress that the child-care and fertility hypothesis is extremely difficult to test in a methodologically defensible manner. First and most crucially, local, generally unmeasured factors can affect the availability of child care. Some of these factors are idiosyncratic (e.g., a local leader who successfully advocates an increase in child-care availability, or a local church that provides free space for a parent-run child-care center, thereby subsidizing it), while others are systematic (the national government could support child care in regions with labor force shortages). In sum, one cannot assume that child-care centers are “randomly assigned” to neighborhoods as in a carefully designed experiment. Rather, the demand for child-care services, and their emergence, would likely be greatest where work/family conflict was most strongly felt. This same conflict would likely produce low levels of fertility. Thus, simple comparisons can show greater child-care availability associated with lower fertility. In fact, we show below that not controlling for unmeasured local characteristics produces this unexpected result. Such theoretically counterintuitive findings are not novel in the fertility literature. Early studies of the association between proximity to family planning clinics and fertility levels in developing countries often found a positive association—family planning clinics were found in areas with higher fertility. But this anomalous association was produced by endogenous placement of clinics—in centrally administered family planning programs, administrators placed clinics in high-fertility areas. When this endogeneity was controlled statistically, the expected negative association was found (Rosenzweig and Wolpin 1986). In a parallel way our research must take into account the placement of child-care centers. We do so by using a fixed-effects modeling strategy.

Second, the data demands for a defensible test, whether using a fixed-effects approach or not, are substantial. Measures of child-care availability throughout a woman’s reproductive period are needed, which means knowing all her places of residence and having a time series of child-care accessibility in those locations. Third, potential parents can move from areas with a paucity of child-care centers to areas where they are more readily available. Such selective migration should be taken into account,2 complicating statistical analyses. Fourth, there is unobserved heterogeneity at the individual level, with fecundity being perhaps the best example. Women and their partners vary with respect to their fecundity, and it is essentially impossible to adequately measure fecundity. Unmeasured fecundity and other unobserved variation must be modeled. All four factors must be addressed simultaneously to provide a rigorous test of the child-care availability and fertility hypothesis. In general, appropriate data and statistical techniques have not been available or have not been used in previous research. Thus, the empirical literature on this important question remains inconclusive, and policymakers have been forced to act on theory not yet substantiated by conclusive empirical evidence.

The Norwegian setting

The data for this article are from Norway, a country with slightly less than 5 million people. In 2009, its total fertility rate was approximately 2.0—among the highest in Europe.

Our data cover the period 1973–1998, during which time Norway experienced changes that likely affected fertility behavior and the development of government policies. As in other high-income countries, educational attainment increased rapidly, with the pace quicker for women than for men (Kravdal and Rindfuss 2008). Further, Norway was still in the process of urbanizing. In 1970, 34 percent of the population lived in places with 200 or fewer residents; the comparable figure in 2000 was 23 percent (Statistics Norway 2009, 2010).

During our study period Norway became one of the world’s top oil-producing countries, with 80 percent of the revenue going to the government (Fasano 2000; Gylfason 2001; Höök and Aleklett 2008; Jafarov and Leigh 2007). Oil production started in 1971 and peaked in 1998; gas production started a few years later and is still increasing. These oil and gas revenues allow Norway to run large budget surpluses, cushion government programs from periodic recessions, and provide resources that can be used well into the future. Most of the revenue has been deposited in the Government Pension Fund, which has more than $80,000 for every Norwegian (Höök and Aleklett 2008) and it is still growing.

Our statistical model controls for the effects of these broad trends at the country level by including age and cohort and then age at first birth and duration since last birth. We cannot separate the effects of one national period from the effects of other periods, but their presence does not affect our child-care results.

Scholars producing typologies of the social and social policy aspects of modern, postindustrial countries group Norway together with its Scandinavian neighbors: Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. For example, Esping-Andersen’s classic work (1990, 1999) puts all four countries in the social democratic category, with an individual’s welfare rendered as a matter of right with limited reliance on social policies promoting equality and in contrast to liberal (e.g., United States, Switzerland) or conservative (e.g., Italy, Germany) welfare regimes. Focusing specifically on family policies, Gauthier (2002) groups these four Scandinavian countries together, having universal welfare benefits, good maternal leave provisions, and widely available child-care centers. And focusing on fertility, Caldwell and Schindlmayr (2003) also place them in the same group.

In contrast, analysts focusing on just the four Scandinavian countries view Norway as an outlier on family policies, especially in the 1970s and earlier, but “catching up” in the 1980s and 1990s (Sörensen and Bergqvist 2002; Sainsbury 2001). From a fertility perspective, women in Norway have a lower age at first birth compared to the other three countries and larger educational differences in ages at first birth (Rønsen and Skrede 2008).

Norway has adopted a number of parental leave policies motivated by an interest in promoting gender equality, improving the well-being of women and families, involving fathers in childrearing, and stimulating the economy through increased female labor force participation (see Brandth and Kvande 2009; Datta Gupta et al. 2006; Duvander et al. 2010; Lappegård 2009; Rönsen and Sundström 1996; Rønsen 2004). Compared to its Scandinavian neighbors, Norway was early in introducing paid maternity leave in 1956. The duration was 12 weeks; the benefits were relatively low compared to prevailing wages but they were not taxed. The duration was extended to 18 weeks in 1977 and the right to unpaid leave for an additional year was added. Fathers could share the benefits except during the first six weeks after birth. In 1978 benefits were raised to 100 percent of pre-birth income for most mothers, and they became taxable and pensionable. The duration was extended to 20 weeks in 1987 and 22 weeks in 1988. In 1993 benefits were extended to 42 weeks at full pay or 52 weeks at 80 percent pay. There have been no changes in duration since.3 To obtain benefits the mother must have worked six of the previous ten months; otherwise she receives a lump sum payment. Also in 1993, four weeks of the parental leave time was reserved for fathers, and fathers’ use of paternal leave, while still modest, has been increasing (Haataja 2009).

Norway also has parent-friendly workplace policies. For example, a new mother is entitled to two hours of break time each day to permit breast-feeding. Parents have the right to stay home with sick children 20–30 days per year. Not surprisingly, in comparison to a variety of other countries, Norway ranks high on egalitarian gender attitudes (de Laat and Sevilla Sanz 2006), the share of child care provided by fathers (Hook 2010; Sacerdote and Feyrer 2008; Sullivan et al. 2009), and the preference for working fewer hours even if doing so means lower income (Stier 2003). Norway ranks low in the average number of hours worked per year per employed person, and this number declined considerably during the period examined here (OECD 2010).

Norway provides a substantively informative setting for a strong test of the child-care and fertility hypothesis. Not only does it have the appropriate data, but during the time period under examination Norway experienced a substantial expansion of child-care availability, with relatively large differences in availability across municipalities (Rindfuss et al. 2007; Rønsen 2004). In 1973, the percent of children aged 0 to 6 in child-care centers was close to zero. This increased to over 40 percent by the late 1990s and is still increasing. There are public day-care centers, established by municipalities, as well as private ones. Private day-care centers are nonprofit and are typically started in response to insufficient availability of public centers. Regulations regarding the training of child-care providers, ratio of adult providers to children, and the like are set by the national government. These regulations cover both public and private day-care centers, and the consensus is that the resulting quality of care is very high.

Both public and private day-care centers are heavily subsidized by the national government. At the end of the period studied here (1998), both types of centers received government subsidies of approximately $uS500 per month per enrolled child, slightly more than half the total cost (Håkonsen et al. 2003). Many public centers also receive a subsidy from the local municipality, and low-income parents are sometimes further subsidized. Because of government subsidies, parents’ share of the cost of child care is affordable given the level of Norwegian household income. For couples with a median after-tax income of approximately $65,000 and at least one child younger than age five, the price for a year of day care was less than $4,000 in 2007 (Statistics Norway 2008). Although the original motivation for providing child-care centers was to prepare children for school independent of parental resources (Bernhardt et al. 2008; Sörensen and Bergqvist 2002), and thus was closer to the German than the Scandinavian model, the motivation soon switched to accommodating working parents and promoting gender equality. Given this motivation, centers’ hours of operation are designed to accommodate the work and commuting schedules of parents. All child-care centers are open early enough in the morning to allow parents to commute to their place of work, and they remain open until most parents return from work in the evening.4 Hence Norwegian day-care centers have features that reduce the incompatibility between the roles of worker and mother.

Data

Our data come from two sources. At the municipality level, we use data on two variables (child-care availability and the level of female unemployment, with the latter measured as the number of women reported unemployed divided by the total number of women aged 16–66) from the Norwegian Social Science Data Services, available for each of Norway’s 435 municipalities. The child-care data are available beginning in 1973 when the expansion in child-care facilities began. Our measure is the percentage of pre-school-age children in child-care centers by municipality and year. As such, this is literally a measure of use rather than availability. However, throughout the period we examine, the demand for child care exceeded the supply (Asplan-Viak 2005; Rindfuss et al. 2007), hence our variable measures both availability and use. In addition to availability, theories about child care and fertility (e.g., Andersson et al. 2004; Rindfuss and Brewster 1996) include consideration of quality, cost, and acceptability. We do not have measures of these three dimensions, but we argue that their absence is unlikely to affect our results because there is little variation on these dimensions across the 435 municipalities. Quality standards are set by the national government rather than municipalities. Because these standards are very high, there is little incentive for municipalities to exceed them. Similarly there is little variation in cost across municipalities (Rauan 2006). The long-running support for subsidized child-care centers across Norway and the absence of any organized opposition to such subsidies indicate the social acceptability of using child-care centers.

The second source of data is individual-level records for women from various registers that cover the entire Norwegian population. These registers are linked by means of a personal identification number5 assigned to all individuals who have lived in Norway after 1960. The country’s population registration system is of very high quality and is constantly updated and cross-checked against other Norwegian data systems.

The 1973 starting date for data on child-care centers influenced the cohorts we analyze; given our statistical approach it is important to start the discrete-time hazard analyses at the beginning of the childbearing process to avoid problems caused by left-censoring.6 The 1957 birth cohort turned 15 in 1973. To include most of the childbearing of the cohorts examined, we wanted to follow cohorts through at least age 35. Given that our data end in 1998 and the 1962 cohort turned 35 in 1998, we examine the childbearing of cohorts 1957–1962. Below are the average number of children born to these cohorts and surrounding cohorts by ages 35 and 45:

| Birth cohort |

Age |

|

|---|---|---|

| 35 | 45 | |

| 1945 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| 1950 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| 1955 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| 1960 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| 1965 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

SOURCE: See endnote 7.

The expected pattern of postponement of childbearing by the more recent cohorts can be seen by looking at children ever born by age 35, but even with some recuperation of childbearing there is relatively little variation in children ever born by age 45 for these cohorts. Further, approximately only 0.1–0.2 births occurred after age 35 for these cohorts, so we are capturing almost all of their fertility experience. And we note that our sample of women is large (85,550), permitting complex analyses with stable results.

At the individual level, a number of background and time-varying variables are available. Background variables include the educational level of the woman’s mother and father, coded into six categories: no information available, compulsory or less, 10 years, high school or vocational school, some college, college or more. The other background variable is birth cohort (1957–1962). Cohort is included for the transition to parenthood (from parity 0 to parity 1) to control for possible cohort trends as well as for age by period factors. Cohort is excluded in subsequent parity transitions because age at first birth and duration since last birth are sufficient trend controls (cf. Ní Bhrolcháin 1992).

A number of time-varying controls are used in the analysis, including three that track aspects of time. In the transition to first birth, woman’s age is entered as a main effect and also interacted with all other variables in the model. The need to interact age with other variables when examining the transition to parenthood is well established in the fertility literature8 (e.g., Rindfuss et al. 2007). After the first birth, age is no longer controlled. Rather we control for age at first birth (an indicator of the life-course stage when the woman became a mother and various period factors) and duration since last birth (indexing a number of possibilities including experiences with the previous child, fecundity impairments, non-family aspects of their lives, and/or period changes).

Both enrollment in school and educational attainment are controlled. The categories for the woman’s education are the same as for her parents’ except that there is no category for missing data.

We include two additional time-varying variables. The first controls for whether the woman lived abroad during some years, perhaps to obtain more education. This variable signals that we do not have child-care availability for these years. The second time-varying variable is the mother’s location vis-à-vis her daughter’s. This variable is relevant because mothers (that is, a potential grandparent) may provide child care for their daughters, affecting the importance of child-care centers. There are four categories for mother’s location: same municipality as her daughter (potentially available to help with child care), different municipality, dead or abroad, and no information. This last category, “no information,” requires additional discussion. The links between the woman’s records and her parents’ records were established by Statistics Norway with the 1970 census. If, for whatever reason, the woman was not then residing with her parents, no link was established, hence the missing data on the mother’s location as well as her mother’s and father’s education. To avoid losing women without links to their parents’ records,9 our procedure makes missing parental information the omitted variable (reference category) for all three sets of variables.

Time-varying variables are lagged two years, allowing for five months average waiting time to conception, for a nine-month gestation, and for an average birth occurring during the middle of the calendar year. The only exception is age, for which there is no need to lag by a constant amount. Note that for women who moved from one municipality to another, this lag gives preference to the destination municipality’s characteristics, and it assumes that people are aware of a migration many months before it occurs and that they are aware of relevant characteristics at the destination before they migrate. We have tested whether our child-care results are sensitive to this assumption and found that they are not.

Methods

We use a discrete-time hazard model to estimate the determinants of the timing of births, starting with the first and continuing through later births. Subsequently, we use these statistical results in a simulation model to estimate the effect of different child-care availability scenarios on total number of children born to women by age 35. In the discrete-time hazard model we allow the effects of child-care availability and other variables to vary by birth interval, and we control for unobserved heterogeneity using a non-linear heterogeneity variation of the Heckman–Singer (1984) procedure, which allows very general patterns of correlation across birth intervals. Municipality-level fixed effects are included to control for endogenous or idiosyncratic placement of child-care facilities. Because the preferred model, including municipality effects and heterogeneity distribution parameters, has over 700 coefficients, we use a simulation model that allows us to present the main substantive results in an easily-understood metric: number of children.10

We jointly estimate the timing of the first through fifth birth for Norwegian cohorts 1957–1962 for ages 15 to 35. Thus sixth and higher-order births as well as births at ages 36 and above are not included. Such births are rare. Finally, as noted above, the effects of child-care availability and other variables on the first birth are expected to vary by age, thus we include age interactions with all predictor variables when modeling age at first birth.

Results

To interpret the simulated numbers of children ever born under varying scenarios of child-care availability, recall that the actual number of children born to the average woman at age 35 in these cohorts was 1.85. Table 1 shows the simulated average number of children ever born by age 35 for various levels of child-care availability. These simulations assume that the given level of all-day child care was achieved immediately in 1973, when members of the study cohorts were aged 13 or younger. (Later we relax this assumption.) The magnitude of these differences, a 0.67-child difference between 0 percent and 60 percent in child care, is large but not incredulously so. For each 10 percent increase in child-care availability there is slightly more than a tenth of a child increase in the average number of children born. Thus the counterfactual: if Norway’s level of child-care availability had remained at its 1973 level, which was just slightly above 0 percent, the simulated average number of children ever born would be 1.51, which is comparable to the low levels of fertility found today in many European countries.

TABLE 1.

Simulated average number of children ever born by age 35 to Norwegian women of birth cohorts 1957–1962 by level of child-care availability under the assumption that the indicated level was reached in 1973

| Percent child-care availability |

Number of children ever born |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1.51 |

| 10 | 1.62 |

| 20 | 1.74 |

| 30 | 1.85 |

| 40 | 1.97 |

| 50 | 2.08 |

| 60 | 2.18 |

One might argue that only after becoming a parent does one really know the time demands placed on parents, especially mothers. Hence, the effects of an expansion in child-care availability might be smaller for the transition to parenthood than for subsequent parity transitions. Further, in a setting where only approximately 8 percent of women have four or more children, those who have a fourth and a fifth child are by definition unusual and possibly less influenced by child-care availability. To examine these hypotheses, we calculated simulated parity progression ratios (i.e., the proportion at parity X who go on to have the X+1th child) for four levels of child-care availability: 0, 20, 40, and 60 percent. The first column in Table 2 shows the parity progression ratios actually experienced by women in the 1957–1962 cohorts. Most have had a first child (86 percent). For those with a first child, slightly more than three-quarters have a second. Past the second child, the parity progression ratios drop off rapidly. This pattern, in which the majority of women have a first and second child but relatively few have a third, fourth, or fifth, is typical for contemporary, economically developed countries.

TABLE 2.

Simulated parity progression ratios by age 35 for Norwegian women of birth cohorts 1957–1962 by level of child-care availability under the assumption that the indicated level was reached in 1973

| Parity progression |

Parity progression ratios |

Differences between 60 and 0 percent simulated child-care availability |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual | Simulated level of child care | Absolute | Relative | ||||

| 0 | 20 | 40 | 60 | (60 – 0) | (60/0) | ||

| 0 to 1 | .86 | .80 | .84 | .88 | .91 | 0.11 | 1.14 |

| 1 to 2 | .78 | .65 | .74 | .82 | .88 | 0.22 | 1.35 |

| 2 to 3 | .38 | .28 | .35 | .41 | .46 | 0.18 | 1.64 |

| 3 to 4 | .19 | .18 | .20 | .22 | .24 | 0.06 | 1.33 |

| 4 to 5 | .16 | .14 | .16 | .19 | .22 | 0.08 | 1.57 |

The remainder of Table 2 shows simulated parity progression ratios for levels of child-care availability at 0, 20, 40, and 60 percent, as well as the absolute and relative differences between the extremes (0 and 60 percent). The simulated parity progression ratios confirm our expectations. The largest absolute difference is found for the transition to the second child (0.22), and the largest relative difference is for the transition to the third child (1.64). But more importantly, a substantively significant positive effect of increased child-care availability is found for all the simulated parity transitions.

So far our simulations assume that the target level of child-care use is reached instantaneously in 1973, but such a large instantaneous jump in child-care availability (and use) is unrealistic. In Table 3 we show the simulated average number of children ever born by age 35 for child-care availability levels of 20, 40, and 60 percent, under the assumptions that it takes 0, 5, 10, and 15 years to reach the specified level. As one would expect, the sooner the designated level of child-care use is reached, the larger the simulated number of children born by age 35. Note that compared to the differences by level of availability shown in Table 1, the implementation timing differences are modest, as would be expected given the low levels of childbearing in Norway in the teens and early 20s. Yet, these timing differences are not trivial. If the ultimate goal is to have 60 percent child-care availability, then reaching that goal immediately results in 7 percent more births compared to taking 15 years to reach 60 percent availability (i.e., relative difference 0 versus 15 years equals 1.07—see final column).

TABLE 3.

Simulated average number of children ever born by age 35 to Norwegian women of birth cohorts 1957–1962 with child-care availability rising to 20, 40, or 60 percent, by number of years it takes to reach the indicated level

| Percent child- care availability |

Years to reach indicated level of child-care availability |

Differences between 0 and 15 years to reach indicated level of child- care availability |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | Relative | |||||

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | (0 – 15) | (0/15) | |

| 20 | 1.74 | 1.73 | 1.71 | 1.68 | 0.06 | 1.04 |

| 40 | 1.97 | 1.95 | 1.91 | 1.86 | 0.11 | 1.06 |

| 60 | 2.18 | 2.15 | 2.10 | 2.03 | 2.15 | 1.07 |

| Difference between 60 and 20 percent child-care availability | ||||||

| Absolute (60 – 20) | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.35 | ||

| Relative (60/20) | 1.25 | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.21 | ||

Table 3 also addresses a related question: does the impact of moving from 20 percent to 60 percent availability vary depending on the number of years it takes to reach 60 percent? The answer is yes, and again the differences are modest. If the change is instantaneous from 20 to 60 percent, then fertility is increased by a factor of 1.25 (25 percent increase). In contrast, if one assumes a steady increase across a 15-year period, then the increase is 21 percent.

Sensitivity issues

Our model includes two time-varying education variables for women: attainment and whether enrolled in school. Many would argue that a woman’s educational career is endogenous with the fertility process, especially in a country like Norway with its open educational system (where it is common to drop out of school and return later). To ensure that our results on child care in child-care centers were not sensitive to the possibility that the woman’s education is an endogenous process, we also ran the statistical model without educational enrollment and attainment. Doing so did not appreciably change the child-care results.

Our preferred model, the one used for the simulations in Tables 1-3, has municipality fixed effects and a heterogeneity correction. We also estimated a “naïve model”—that is, a model with neither municipality fixed effects nor controls for unobserved heterogeneity. Much of the literature on the effects of child-care availability (as well as broader studies looking at the effects of other institutional changes) uses variations of this naïve model. Table 4 has simulations from the naïve model that are analogous to the simulations in Table 1 based on our preferred model with municipality fixed effects and a heterogeneity correction. In interpreting Table 4 remember that the actual number of children ever born to these cohorts was 1.85 and that theory predicts a strong positive relationship between availability of day care and children ever born. The results in Table 4 are the opposite of theoretical expectations and the opposite of results from our preferred model. While the differences due to changes in child-care availability are not large, they show a negative relationship between child-care availability and fertility. We show these results to highlight the importance of controlling for unobserved characteristics of municipalities and unobserved individual-level heterogeneity. The former is likely to be the more important as it controls for the endogenous growth of child-care availability—child-care centers were likely started in places where the conflict between work and family was most intense and where fertility was correspondingly low.

TABLE 4.

Naïve model: Simulated average number of children ever born by age 35 to Norwegian women of birth cohorts 1957–1962 by level of child-care availability under the assumption that the indicated level was reached in 1973

| Percent child-care availability |

Number of children ever born |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1.93 |

| 10 | 1.91 |

| 20 | 1.88 |

| 30 | 1.86 |

| 40 | 1.83 |

| 50 | 1.80 |

| 60 | 1.77 |

Discussion

The Norwegian experience shows that institutional adjustments can reduce the conflict between work and family responsibilities, leading to a fertility level much closer to replacement level than one would observe without these changes. Depending on the speed with which the availability of child-care slots moved from 0 to 60 percent, children ever born by age 35 increased by 0.5 to 0.7 children. This is a substantial increase, but not so large as to lead one to doubt the validity of the results. Our results are consistent with both sociological and economic theories and provide firm empirical evidence to question the inevitable “incongruity” between family and work posited by Davis and others.

What are the implications of our results for countries that today have TFRs of 1.5 or lower? If the results reported here are applied to these other countries, moving from 0 to 60 percent child-care availability (reasonably priced, high quality, and open during normal working and commuting hours) would bring their TFRs close to replacement levels. This raises the important question, however, to what extent the Norwegian results are applicable to other countries.

On the one hand, these results are predicted by sociological and economic theory, thus we would expect similar effects in other countries. But several factors suggest caution because policies, like Norway’s extension of child-care availability, do not arise from a cultural, normative, and institutional vacuum. One must recognize that high-income, low-fertility countries differ markedly among themselves in their cultural, normative, and institutional structures, and these structures, in turn, influence their policy goals and the policies they adopt (see McDonald 2002/3). Consider a country with sharp gender differentiation and a male-breadwinner model. In reaction to prolonged below-replacement fertility, with its attendant effects on population age structure and growth rates, could such a country expect a substantial fertility increase by adopting Norwegian-style child-care policies?

Our answer to this question is a cautious “yes.” Our caution has several sources. First, the lack of data handicaps our ability to test the child-care hypothesis on a diverse group of countries. As we argued above, a methodologically defensible test of the child-care hypothesis has stringent macro/micro data requirements along with the need to use appropriate statistical methods. To the best of our knowledge the only other countries that have the requisite data are Norway’s neighbors (Denmark, Finland, and Sweden). These countries share so many institutional and policy similarities with Norway that including them would do little to make this a “legitimate test” of the wider applicability of our results—to, say, southern Europe or Asia. Thus we are in the position of speculating with little data.

What about Norway’s unique features? To begin, consider the type of explanations that rely on the role played by specific individuals in establishing and/or implementing policies. To illustrate, we use one of the arguments as to why Sweden moved to provide child-care centers earlier than Norway. The argument is of interest because it involves two Swedish social scientists: Alva and Gunnar Myrdal. In 1934 they published Kris I befolkningsfrågan (The Crisis of the Population Question) in which they argued for redistributing to the broader population some costs of raising children, including having low-cost child-care centers open during normal working hours, free health care, and the elimination of education costs to parents. Not only did the book receive wide attention, but its authors were appointed to influential policy-recommending committees: Alva Myrdal was secretary for the Committee on Women’s Employment, and Gunnar Myrdal was a member of the Population Committee. As such, they were in a position to influence the framing of policy discussion; and it is argued that this framing had long-lasting implications (Sainsbury 2001; Sörensen and Bergqvist 2002). We do not dispute such an idiosyncratic explanation for the timing of the growth of child-care centers. Indeed the need to control for such idiosyncratic “local” factors is the logic behind our use of municipality fixed-effects dummies in the analysis of Norwegian data. But arguments about the theoretical effect of child-care centers and our empirical estimates for Norway are anchored in broad theories in contexts where idiosyncratic factors are also operating.

Of course, there is truth in the claim that Norway is unique. One of our reviewers suggested that “Norway is in many ways a highly unrepresentative country in Europe.” In an earlier section we described key differentiating characteristics: Norway’s oil wealth alone makes it stand out. Its gender ideology is egalitarian; its political economy social democratic. This discussion of Norway could be greatly expanded; for example, its provision of ample reserved space for baby carriages on public buses, metros, and trains, if not unique, is a rarity that makes life more convenient for parents of infants.11 But the broader point is that child-care centers may have a greater impact within a context including other features that also reduce family/work conflict—in statistical terms, this is a suggestion that the effect of child-care availability “interacts” with other macro-level factors. To use McDonald’s (2002/3) metaphor, what needs to be pulled from the “tool kit” of possible policies to increase childbearing in a country with below-replacement fertility? Norway employs an impressive subset of the policy tools that McDonald lists. Policy analysts in low-fertility countries are advised to consider the country-specific “obstacles” women and couples face in achieving their preferred family size (usually a mean of two children). We are certain that such analysis would universally identify child-care centers as reducing the conflict between work and family. But other policies that promote marriage, allow maternity leaves, and encourage paternal participation in parenting might be needed as well.

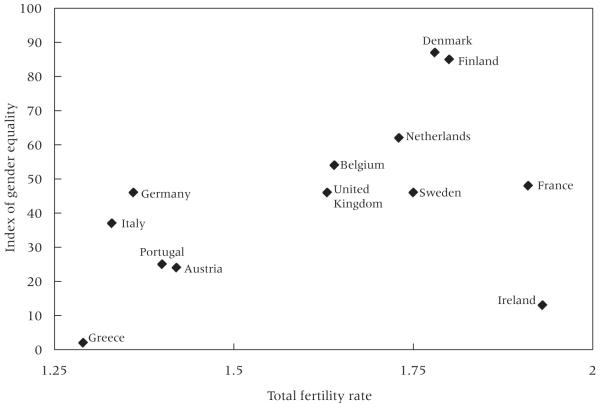

It is also possible that the prevailing values, norms, and behavior in a country interact with the likelihood that a Nordic-style expansion of child-care centers would have a strong positive impact on fertility. More specifically, we have noted that Norway is characterized by relatively egalitarian gender relations, with fathers providing considerable help to mothers beyond financial help in raising children and performing household chores. Several recent articles (de Laat and Sevilla Sanz 2006; Sacerdote and Feyrer 2008) show a positive correlation between the level of a country’s TFR and a measure of that country’s egalitarian gender attitudes or behavior. Figure 1 shows a simple scatterplot comparing a country’s index of gender equality circa 2000 with its TFR circa 2004 for 13 EU countries.12 The index of gender equality is based on four dimensions: sharing of paid work, sharing finances, sharing decision-making, and sharing time spent caring for others and leisure time. The country in the lower right corner of the scatterplot, Ireland, is an outlier. Excluding Ireland, we see a clear positive relationship between gender equality and TFR (r=+0.74).13 This positive association, consistent with the theoretical arguments of McDonald (2000), raises the possibility that several factors (such as greater gender equality in the family and in the labor market, paid paternal leave during the first year following childbirth) must be present before substantial increases in child-care availability can have a major influence on low TFRs.

FIGURE 1. Relationship between an index of gender equality and total fertility rates for 13 European Union countries.

SOURCES: Total fertility rate circa 2004 (VID 2006); index of gender equality circa 2000 (Plantenga et al. 2009, Table 4, Column 3).

To extend and illustrate the argument, consider Japan, which has had below-replacement fertility for over 25 years. Would greatly expanded child-care accessibility lead to a significant increase in Japan’s fertility level absent changes in various norms, behaviors, and institutional context? Among the factors argued to be influencing Japan’s low fertility (Bumpass et al. 2009) are: strong norms against nonmarital childbearing (currently about 2 percent of all births), women’s desire to have husbands who make marriage easier and more equitable for women (currently husbands do very little work around the house and provide little help with children’s homework; if the husband is a first-born son, the wife is expected to care for the husband’s parents), and difficulty returning to the labor force in a “regular” job (i.e., one with full benefits, on-the-job training, advancement possibilities, and the possibility of life-time employment) after a period out of the labor force to care for young children.14 Given this profile, Japan would score low on a gender equality index, such as the one used in Figure 1. So the question is, if Nordic-style child-care availability suddenly materialized in Japan, would fertility rise without concurrent changes in these other fertility-inhibiting factors? If increased high-quality, low-cost, convenient child-care availability is pronatalist only in settings with high gender equity, then the answer would be no. Our opinion is that the effect of increased child-care availability in Japan would lead to higher fertility even without change in gender equity, but the scale of the effect is likely to be lower than we saw in Norway.

In sum, there are several reasons to be cautious in generalizing from results in Norway to countries such as Austria, Germany, Italy, Spain, Japan, or South Korea—countries with low levels of fertility for more than a decade. But there is nothing in the economic and sociological theory behind the Norwegian results suggesting that they would not extend to other countries, although we sketch a scenario above where the effects could be smaller outside Scandinavia.

We close by noting that Germany is the first country that has expressly taken steps to expand child-care availability (along with other policy changes) in an attempt to increase fertility levels. Until quite recently, Germany would have been classified as a conservative welfare state: it had a strong male-breadwinner model and a tax code that benefited families conforming to that model, a high value on the mother’s care of young children, high wages and protection for the core male work force, and a generous maternal leave policy (Esping-Andersen 1990, 1999; Lewis et al. 2008; Spiess and Wrohlich 2008). Especially in West Germany there is low availability of child-care slots for children aged less than three years; child care for children aged 3–6 as well as primary school is half-day, thus doing little to ease the incompatibility between the mother and worker roles; there is limited development of a private child-care market; and there is heavy reliance on grandparents and other relatives for child care (Coneus et al. 2009; Hoem 2005; Kreyenfeld 2004; Wrohlich 2008). Germany’s TFR has been below replacement since the early 1970s (under 1.5 much of that time), and its population size has been declining since 2003 (Dorbritz 2008).

Because of concern about population aging and its attendant socioeconomic consequences, German policymakers on both the left and the right have initiated a policy paradigm shift, recently adopting Nordic-style policies (Coneus et al. 2009; Dorbritz 2008; Lewis et al. 2008; Ruling 2008). For example, a December 2008 law establishes the right to a child-care slot for all preschool children age one and above by 2013. Other changes and goals include cutting time for maternal leave to the Nordic level, increasing the proportion of fathers who assume substantial care responsibilities, and, in general, producing a better reconciliation of work and family life for women. Depending on how the child-care programs are implemented,15 German experience could begin to provide an answer to the wider applicability of the Norwegian findings presented here.

Acknowledgments

The analyses reported here were partially supported by a grant from NICHD (R01-HD038373). Rindfuss and Kravdal also received support from the Centre for Advanced Study of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. We thank Statistics Norway, especially Halvor Strømme and Kåre Vassenden, for making the data available to us. Erika Stone provided excellent programming assistance and Ann Takayesu provided excellent manuscript preparation assistance. Johannes Huinink provided helpful comments on the current German situation.

Footnotes

In many countries, the increased education of women, combined with the greater labor force experience they have as a result of delayed childbearing, means that the differential between the wages of well-educated mothers and those of relatively low-skilled child-care workers has increased (see Martinez and Iza 2004)—although the cost of child care for women with low educational attainment who work in low-paid occupations presents an obstacle.

To the extent that unobserved fixed aspects of a community with good availability of child-care centers influence individuals to remain in or migrate to that community, our estimation approach accounts for such migration. Details and an example can be found in Rosenzweig and Schultz (1982) and Strauss and Thomas (1995). But, if unobserved individual-level factors are linked to the chance of an individual living in a community with a desirable level of child-care availability, such unobserved individual factors are not controlled in our analysis.

Some of the countries that Esping-Andersen (1990, 1999) classifies as having conservative welfare regimes have considerably longer paid/unpaid maternity leaves. Norway did not go this route because longer absence makes it more difficult to re-enter the labor market and decreases one’s marketable human capital (Sainsbury 2001).

Generally parents have to take their children out of child care for three weeks during the summer. Some centers allow full flexibility in scheduling these three weeks; others are closed for three weeks, forcing parents to choose those weeks. But this is a manageable problem, given Norwegians’ proclivity for long summer vacations.

To maintain confidentiality, Statistics Norway removed all identifiers, including place identifiers, after construction of the work file used in this article.

The issue of left-censoring and the problems it can cause are discussed in an appendix available at «http://www.unc.edu/~rindfuss/Appendix-PDR-December2010.pdf».

Source: «http://www.ssb.no/english/subjects/02/02/10/fodte_en/tab-2010-04-08-09-en.html». The number for age 45 for the 1965 cohort is actually for the 1964 cohort. The comparable number for the 1965 cohort is not yet available.

To intuitively see the need for age interactions in the transition to parenthood, remember that most women want to have the first child, but not too early because of other life-course events that are occurring in the early childbearing years (education, job search, career establishment, finding a suitable partner, and so forth), and not too late because of concerns about diminished fecundity. As a result, many of the factors that tend to have a delaying effect in the teens and early 20s turn into positive effects in the 30s.

Slightly less than one-quarter of the women did not have links to their parents’ records.

These methods are not new to demographic research (see, e.g., Strauss and Thomas 1995), but they have been more commonly used in work in less developed countries rather than more developed countries. The technical details of our discrete-time hazard model and the simulation model are discussed in an appendix that also includes tables giving coefficients from our models; here we simply present a few details to aid in interpreting our results. The appendix is available at «http://www.unc.edu/~rindfuss/Appendix-PDR-December2010.pdf».

See Rindfuss and Brauner-Otto (2008) for a discussion of policies that inadvertently affect fertility.

The countries are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, and United Kingdom. Note that Norway is not a member of the EU, and a comparable gender equality index for Norway is not available.

If Ireland is included in the correlation calculation, the value falls to 0.47.

Japanese employers prefer to hire recent college or high school graduates for “regular” jobs. Knowledge of the particular school provides guidance on the appropriate person to hire. This strategy essentially discriminates against mothers.

Germany’s TFR dropped to 1.38 in 2009, providing further impetus to implement these policy changes; but the economic recession is threatening their full-scale implementation (Moore 2010).

References

- Adsera Alicia. Changing fertility rates in developed countries: The impact of labor market institutions. Journal of Population Economics. 2004;17:17–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn Namkee, Mira Pedro. A note on the changing relationship between fertility and female employment rates in developed countries. Journal of Population Economics. 2002;15:667–682. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson Gunnar, Duvander Ann-Zofie, Hank Karsten. Do child care characteristics influence continued childbearing in Sweden? An investigation of quantity, quality, and price dimension. Journal of European Social Policy. 2004;14(4):407–418. [Google Scholar]

- Apps P, Rees R. Fertility, taxation and family policy. Scandinavian Journal of Economics. 2004;1006:745–763. [Google Scholar]

- Asplan-Viak Analyse av barnehagetall pr 20.09.2005. Arbeidsrapporter Oktober 2005_v5. Oslo. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary S. Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries. Princeton university Press; Princeton, NJ: 1960. An economic analysis of fertility; pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary S., Gregg Lewis H. On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy. 1973;81(2, part 2):S279–S288. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt Eva, Noack Turid, Lyngstad Torkild Hovde. Shared housework in Norway and Sweden: Advancing the gender revolution. Journal of European Social Policy. 2008;18(3):275–288. [Google Scholar]

- Blau David M., Robins Philip K. Fertility, employment and child-care costs. Demography. 1989;26:287–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonoli Giuliano. The impact of social policy on fertility: evidence from Switzerland. Journal of European Social Policy. 2008;18:64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Brandth Berit, Kvande Elin. Gendered or gender-neutral care politics for fathers. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009 July;624:177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Bratti Massimiliano, Tatsiramos Konstantinos. Explaining how delayed motherhood affects fertility dynamics in Europe. 2008 IZA Discussion Paper No. 3907. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster Karin, Rindfuss Ronald R. Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized countries. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:271–296. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann Claudia, DiPrete Thomas A. The growing female advantage in college completion: The role of parental resources and academic achievement. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:515–541. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass Larry L., Rindfuss Ronald R., Kim Choe Minja, Tsuya Noriko O. The institutional context of low fertility: The case of Japan. Asian Population Studies. 2009;5(3):215–235. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John C., Schindlmayr Thomas. Explanations of the fertility crisis in modern societies: A search for commonalities. Population Studies. 2003;57(3):241–263. doi: 10.1080/0032472032000137790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coneus Katja, Goeggel Kathrin, Muehler Grit. Maternal employment and child care decision. Oxford Economic Papers. 2009;61(Supplement 1):i172–i188. [Google Scholar]

- Datta Gupta Nabanita, Smith Nina, Verner Mette. Child care and parental leave in the Nordic countries: A model to aspire to? Institute of Labor (IZA); Bonn: 2006. Discussion Paper No. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davis Kingsley. Reproductive institutions and the pressure for population. American Sociological Review. 1937;29:289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Davis Kingsley. Kingsley Davis on reproductive institutions and the pressure for population. Population and Development Review. 1997;23:611–624. [Google Scholar]

- de Laat Joost, Sevilla Sanz Almudena. Working women, men’s home time, and lowest-low fertility. University of Essex; Colchester: 2006. ISER Working Paper 2006-23. [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca Daniela. The effect of child care and part-time opportunities on participation and fertility decisions in Italy. Journal of Population Economics. 2002;15:549–573. [Google Scholar]

- Demeny Paul. Population policy dilemmas in Europe at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(1):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dorbritz Jurgen. Germany: Family diversity with low actual and desired fertility. Demographic Research. 2008;19:557–598. Available at « www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol19/17/». [Google Scholar]

- Duvander Ann-Zofie, Lappegård Trude, Andersson Gunnar. Family policy and fertility: Father’s and mother’s use of parental leave and continued childbearing in Norway and Sweden. Journal of European Social Policy. 2010;20(1):45–57. [Google Scholar]

- England Paula, Farkas George. Households, Employment and Gender: A Social, Economic and Demographic View. Aldine; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen Gøsta. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Polity Press; Cambridge: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen Gøsta. Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economics. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano Ugo. Review of the experience with oil stabilization and savings funds in selected countries. 2000 International Monetary Fund Working Paper WP/00/112. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Raquel, Fogli Alessandra. Culture: An empirical investigation of beliefs, work and fertility. 2007 National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 11268. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier Anne H. Family policies in industrialized countries: Is there convergence? Population. 2002;57(3):447–474. English version. [Google Scholar]

- Gerson Judith M. Clerical work at home or in the office: The difference it makes. In: Christensen Kathleen., editor. The New Era of Homework: Directions and Responsibilities. Westview Press; Boulder: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein Joshua R., Sobotka Tomáš, Jasilioniene Aiva. The end of ‘lowest-low’ fertility? Population and Development Review. 2009;35(4):663–699. [Google Scholar]

- Gylfason Thorvaldur. Natural resources, education, and economic development. European Economic Journal. 2001;45:847–859. [Google Scholar]

- Haataja Anita. Father’s use of paternity and parental leave in the Nordic countries. The Social Insurance Institution, Research Department; Finland: 2009. working paper 2/2009. [Google Scholar]

- Håkonsen L, Kornstad T, Løyland K, Thorsen T. Økonomiske analyser 5/2003. Statistics Norway, Oslo-Kongsvinger; 2003. Politikken overfor familier med førskolebarn—nen veivalg. [Google Scholar]

- Hank Karsten, Kreyenfeld Michaela. A multilevel analysis of child care and women’s fertility decisions in Western Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:584–596. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman James, Singer Burton. A method for minimizing the impact of distributional assumptions in econometric models for duration data. Econometrica. 1984;52:271–320. [Google Scholar]

- Hirazawa Makoto, Yakita Akira. Fertility, child care outside the home, and pay-as-you-go social security. Journal of Population Economics. 2009;22:565–583. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem Jan M. Why does Sweden have such high fertility? Demographic Research. 2005;13:559–572. Online at « www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol13/22/». [Google Scholar]

- Hook Jennifer L. Gender inequality in the welfare state: Sex segregation in housework, 1965–2003. American Journal of Sociology. 2010;115(5):1480–1523. doi: 10.1086/651384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotz V. Joseph, Klerman Jacob A., Willis Robert J. The economics of fertility in developed countries. In: Rosenzweig Mark R., Stark Oded., editors. Handbook of Population and Family Economics. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1997. pp. 275–347. [Google Scholar]

- Höök Mikael, Aleklett Kjell. A decline rate study of Norwegian oil production. Energy Policy. 2008;36:4262–4271. [Google Scholar]

- Jafarov Etibar, Leigh Daniel. Alternative fiscal rules for Norway. 2007 International Monetary Fund Working Paper WP/07/241. [Google Scholar]

- Kogel Tomas. Did the association between fertility and female employment within OECD countries really change its sign? Journal of Population Economics. 2004;17:45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Øystein. How the local supply of day-care centers influences fertility in Norway: A parity-specific approach. Population Research and Policy Review. 1996;15:201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Øystein, Rindfuss Ronald R. Changing relationships between education and fertility: A study of women and men born 1940-64. American Sociological Review. 2008;73(5):854–873. [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenfeld M. Fertility decisions in the FRG and GDR: An analysis with data from the German Fertility and Family Survey. Demographic Research. 2004;3:275–318. Special Collection. Available online at « http://www.demographic-research.org/special/3/11/». [Google Scholar]

- Lappegård Trude. Family policies and fertility in Norway. European Journal of Population. 2009;26:99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer Evelyn, Kawasaki S. Child care arrangements and fertility: An analysis of two-earner households. Demography. 1985;22:499–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Jane, Knijn Trudie, Martin Claude, Oster Ilona. Patterns of development in work/family reconciliation policies for parents in France, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK in the 2000s. Social Politics. 2008;15:261–286. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz Wolfgang, Skirbekk Vegard. Policies addressing the tempo effect in low-fertility countries. Population and Development Review. 2005;31(4):699–720. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel Hadas, Semyonov Moshe. Family policies, wage structures, and gender gaps: Sources of earnings inequality in 20 countries. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:949–967. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Dolores Ferrero, Iza Amaia. Skill premium effects on fertility and female labor force supply. Journal of Population Economics. 2004;17:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mason Karen Oppenheim, Kuhlthau Karen. The perceived impact of child care costs on women’s labor supply and fertility. Demography. 1992;29(4):523–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matysiak Anna, Vignoli Daniele. Fertility and women’s employment: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Population. 2008;24:363–384. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald Peter. Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review. 2000;26(3):427–439. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald Peter. Sustaining fertility through public policy: The range of options. Population. 2002/3;57:417–446. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Tristana. [accessed 5/27/2010];Baby gap: Germany’s birth rate hits historic low. Time. 2010 « http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,1991216,00.html#». [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S. Philip. Is low fertility a twenty-first-century demographic crisis? Demography. 2003;40(4):589–603. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S. Philip, Taylor Miles G. Low fertility at the turn of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Sociology. 2006;32:375–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrdal Alma. Nation and Family. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Ma: 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Bhrolcháin Máire. Period paramount? A critique of the cohort approach to fertility. Population and Development Review. 1992;18(4):599–629. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . OECD Factbook 2009. [accessed 5/23/10]. 2010. « http://www.oecd.org/document/62/0,3343,en_21571361_34374092_34420734_1_1_1_1,00.html». [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer Valerie Kincade. Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review. 1994;20(2):293–342. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit Becky, Hook Jennifer. The structure of women’s employment in comparative perspective. Social Forces. 2005;84(2):779–801. [Google Scholar]

- Plantenga Janneke, Remery Chantal, Figueiredo Hugo, Smith Mark. Towards a European Union gender equality index. Journal of European Social Policy. 2009;19:19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Presser Harriet B., Baldwin Wendy. Child care as a constraint on employment: Prevalence, correlates, and bearing on the work and fertility nexus. American Journal of Sociology. 1980;85:1202–1213. doi: 10.1086/227130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raley Sara B., Mattingly Marybeth J., Bianchi Suzanne M. How dual are dual-income couples? Documenting change from 1970–2001. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2006;68:11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rauan Estralitta C. Notater 2006/32. Statistics Norway. Oslo-Kongsvinger; 2006. Undersøking om foreldrebetaling i barnehager, januar 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reher David S. Towards long-term population decline: A discussion of relevant issues. European Journal of Population. 2007;23:189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Rendall Michael S., Ekert-Jaffé Olivia, Joshi Heather, Lynch Kevin, Mougin Rémi. Universal versus economically polarized change in age at first birth: A French–British comparison. Population and Development Review. 2009;35(1):89–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss Ronald R. The young adult years: Diversity, structural change, and fertility. Demography. 1991;28(4):493–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss Ronald R., Brewster Karin L. Childrearing and fertility. Population and Development Review. 1996;22(Supp.):258–289. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss Ronald R., David Guilkey S, Morgan Philip, Kravdal Øystein, Guzzo Karen B. Child care availability and first-birth timing in Norway. Demography. 2007;44:345–372. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss Ronald R., Guzzo Karen B., Morgan S. Philip. The changing institutional context of low fertility. Population Research and Policy Review. 2003;22:411–438. [Google Scholar]

- Rønsen Marit. Fertility and public policies—Evidence from Norway and Finland. Demographic Research. 2004;10 (Article 6). Available online at « http://demographic-research.org/volumes/vol10/6/10-6.pdf». [Google Scholar]

- Rønsen Marit, 2008 Kari Skrede. Fertility trends and differentials in the Nordic countries: Footprints of welfare policies and challenges on the road ahead. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research. 2008:103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rönsen Marit, Sundström Marianne. Maternal employment in Scandinavia: A comparison of the after-birth employment activity of Norwegian and Swedish women. Journal of Population Economics. 1996;9:267–285. doi: 10.1007/BF00176688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig Mark R., Paul Schultz T. Child mortality and fertility in Colombia. Health Policy and Education. 1982;2:305–348. doi: 10.1016/0165-2281(82)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig Mark R., Wolpin Kenneth I. Evaluating the effects of optimally distributed public programs: Child health and family planning interventions. The American Economic Review. 1986;76(3):470–482. [Google Scholar]

- Ruling Anneli. Re-framing of childcare in Germany and England: From a private responsibility to an economic necessity. Anglo-German Foundation; 2008. CSGE Research paper. [Google Scholar]

- Sacerdote Bruce, Feyrer James. Will the stork return to Europe and Japan? Understanding fertility within developed nations. 2008 doi: 10.1257/jep.22.3.3. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 14114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury Diane. Gender and the making of welfare states: Norway and Sweden. Social Politics. 2001;8(1):113–143. doi: 10.1093/sp/8.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofer Evan, Meyer John W. The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:898–920. [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen Kerstin, Beregqvist Christina. Gender and the social democratic welfare regime. National Institute for Working Life; Stockholm: 2002. Work Life in Transition Working Paper 2002: 5. [Google Scholar]

- Spiess C. Katharina, Wrohlich Katharina. The parental leave benefit reform in Germany: Costs and labour market outcomes of moving towards the Nordic model. Population Research and Policy Review. 2008;27:575–591. [Google Scholar]

- Stier Haya. Time to work: A comparative analysis of preferences for working hours. Work and Occupations. 2003;30(3):302–326. [Google Scholar]

- Stier Haya, Lewin-Epstein Noah. Welfare regimes, family-supportive policies, and women’s employment along the life-course. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106:1731–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Norway After-tax income for private households. 2008 « http://www.ssb.no/english/subjects/02/01/fobhusinnt_en/tab-2003-12-18-01-en.html».

- Strauss John, Thomas Duncan. Empirical modeling of household and family decisions. In: Behrman Jere, Srinivasan TN., editors. Handbook of Development Economics. III. Elsevier; 1995. pp. 1885–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stycos JM, Weller Robert H. Female working roles and fertility. Demography. 1967;4:210–217. doi: 10.2307/2060362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Norway Resident population at population censuses. 2009 « http://www.ssb.no/english/yearbook/tab/tab-046.html».

- Statistics Norway Minor growth in urban settlements. 2010 « http://www.ssb.no/english/subjects/02/01/10/beftett_en/».

- Sullivan Oriel, Coltrane Scott, McAnnally Linda, Altintas Evrim. Father-friendly policies and time-use data in a cross-national context: Potential and prospects for future research. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009;624:234–254. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO . Global Education Digest 2009. UNESCO Institute for Statistics; Montreal: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Lippe Tanja, Van Dijk Liset. Women’s Employment in Comparative Perspective. Aldine de Gruyter; Hawthorne, Ny: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- VID . European Demographic Data Sheet 2006. Vienna Institute of Demography; Vienna: 2006. « www.oeaw.ac.at/vid/popeurope/index.html». [Google Scholar]

- Willis Robert J. A new approach to the economic theory of fertility behavior. Journal of Political Economy. 1973;81(2, Part 2):S16–S64. [Google Scholar]

- Wrohlich Katharina. The excess demand for subsidized child care in Germany. Applied Economics. 2008;40:1217–1228. [Google Scholar]