Abstract

Classical Menkes disease is an X-linked recessive neurodegenerative disorder caused by mutations in ATP7A, which is located at Xq13.1-q21. ATP7A encodes a copper-transporting P-type ATPase and plays a critical role in development of the central nervous system. With rare exceptions involving sex chromosome aneuploidy or X-autosome translocations, female carriers of ATP7A mutations are asymptomatic except for subtle hair and skin abnormalities, although the mechanism for this neurological sparing has not been reported. We studied a three-generation family in which a severe ATP7A mutation, a 5.5-kb genomic deletion spanning exons 13 and 14, segregated. The deletion junction fragment was amplified from the proband by long-range polymerase chain reaction and sequenced to characterize the breakpoints. We screened at-risk females in the family for this junction fragment and analyzed their X-inactivation patterns using the human androgen-receptor (HUMARA) gene methylation assay. We detected the junction fragment in the proband, two obligate heterozygotes, and four of six at-risk females. Skewed inactivation of the X chromosome harboring the deletion was noted in all female carriers of the deletion (n = 6), whereas random X-inactivation was observed in all non-carriers (n = 2). Our results formally document one mechanism for neurological sparing in female carriers of ATP7A mutations. Based on review of X-inactivation patterns in female carriers of other X-linked recessive diseases, our findings imply that substantial expression of a mutant ATP7A at the expense of the normal allele could be associated with neurologic symptoms in female carriers of Menkes disease and its allelic variants, occipital horn syndrome, and ATP7A-related distal motor neuropathy.

Keywords: ATP7A, junction fragment, Menkes disease, skewing, X-inactivation

In order to maintain equivalent expression levels of X-linked genes between genders, mammals achieve dosage compensation by silencing one of the two X chromosomes in females, a mechanism termed X-chromosome inactivation (1). During the blastocyst stage in female embryos, expression of Xist RNA and transient pairing of the X-inactivation centers (Xic) of the two X chromosomes leads to heterochromatization of one X chromosome and resultant silencing of most of its genes (2). The pattern of X chromosome inactivation is generally random; however, when one X chromosome harbors a deleterious allele, X-inactivation can be non-random: cells that have the mutation-bearing chromosome active may be selected against over time, resulting in a predominance of cells with an active X chromosome containing the normal allele (3, 4). This favorably skewed X-inactivation may protect female carriers of X-linked recessive mutations from the phenotypic consequences of the mutation. In contrast, when an X chromosome carrying a disease allele is not preferentially inactivated, female heterozygotes may manifest conditions usually restricted to males (4, 5). The complex relationship between X-inactivation status and clinical phenotype in carriers of certain X-linked disorders, including α-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome, Barth syndrome, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, incontinentia pigmenti, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, otopalatodigital syndrome, Rett syndrome, severe combined immunodeficiency disease, and Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, is summarized in an excellent recent review (6).

Menkes disease and its allelic variants, occipital horn syndrome and ATP7A-related distal motor neuropathy, are X-linked recessive disorders caused by mutations in the copper-transporting P-type ATPase gene, ATP7A (7–11). Absence or severe reduction in ATP7A activity inhibits intestinal uptake of copper and transport of copper into the developing brain (12, 13). In addition, transport of copper into the trans-Golgi compartment for incorporation by certain copper-requiring enzymes is dependent on ATP7A (14). Thus, the activities of enzymes requiring copper as a cofactor, including dopamine-β-hydroxylase (15, 16) and peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase (17), may be reduced. Males affected with classical Menkes disease have mutations associated with an estimated 0–15% of normal ATP7A activity and exhibit delayed neurodevelopment, dysmyelination, seizures, connective tissue abnormalities (18, 19), and premature death. However, early diagnosis and treatment with copper injections may markedly improve patients’ clinical outcomes, especially if some residual ATP7A activity is present (20). Patients with occipital horn syndrome typically have between 20% and 35% residual copper transport function and far less severe neurodevelopmental abnormalities, even in the absence of early diagnosis and treatment (10, 21). Males with ATP7A-related distal motor neuropathy have ATP7A mutations with an even greater quantity of residual copper transport activity and manifest a late-onset syndrome restricted to progressive distal motor neuropathy, without overt signs of systemic copper deficiency (11).

A total of 10 females affected with Menkes disease have been reported (22, 23), among whom one was mosaic for Turner (XO) syndrome and five had X-autosome translocations interrupting the ATP7A gene. As predicted for the latter circumstance (24), the normal X chromosomes in these five patients were preferentially inactivated, avoiding haploinsufficiency of the autosomal genes involved but resulting in the expression of Menkes disease.

Female carriers of Menkes disease may exhibit subtle clinical manifestations, including patchy skin hypopigmentation (25) and pili torti of scalp hair (26). Biochemically, uncloned fibroblast cultures from Menkes disease obligate heterozygotes showed reduced copper transport compared with normal female controls (27). These findings indicate that mosaicism for the ATP7A mutations, mediated by X-chromosomal inactivation patterns, may be clinically relevant in this condition.

To our knowledge, X-inactivation patterns in cytogenetically normal females heterozygous for ATP7A mutations have not been reported (6). To begin to evaluate this issue, we studied a large family that included numerous at-risk females of child-bearing age.

Methods

Subjects

Ten members of a family with a history of Menkes disease were evaluated. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Utah, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Case history

The proband was born at 36-week gestation by cesarean section for breech presentation to a 22-year-old gravida 3 para 2 aborta 1 mother, after an uneventful pregnancy. The Apgar scores were 5, 8, and 9 at 1, 5, and 10 min, respectively. Jaundice and temperature instability were noted during the first week of life. Due to a family history of Menkes disease in a maternal uncle, plasma neurochemical levels (15, 16, 20) were obtained shortly at birth and were diagnostic for this condition. The infant began copper injection treatment under an NIH protocol (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00001262) at 8 days of age. At 6 weeks of age, failure to thrive and suspicion of clinical seizure activity were noted. Pulmonary insufficiency consistent with emphysema developed subsequently, requiring chronic oxygen administration. The infant died at 5 3/4 months of age from respiratory distress while receiving hospice care at home. The parents declined a postmortem pathological examination.

The mother’s medical history was notable for brief episodes of abnormal movement considered to be minor motor seizures at 11 months of age. She also had scattered regions of hypopigmentation on her trunk, as did one younger sister.

DNA extraction and analysis

Genomic DNA obtained from each family member was isolated from peripheral blood samples using the Gentra Autopure system and Puregene DNA Purification kit. ATP7A mutation analysis in the proband was performed by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (28) of the infant’s genomic DNA and revealed deletion of ATP7A exons 13 and 14. The effects of this deletion on translation of the gene product were analyzed using MACVECTOR software. Long PCR was performed on proband and wild-type genomic DNA with primers spanning the 3′ end of exon 12 and the 5′ end of exon 15 of ATP7A: 12–15 long F: 5′-GGACATTCTATGGTAGATGAGTCCC-3′ and 12–15 long R: 5′-CTGTGATAGAGGCTTGGA-AAGCAAATCG-3′. PCR was carried out for 30 cycles at 98° for 30 s, 94° for 15 s, 60° for 20 s, and 68° for 20 min. The PCR product obtained from the proband was analyzed by automated DNA sequencing (ABI 377 Prism; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) from both ends until the breakpoint was identified.

Junction fragment assay

To provide a method for screening prospective carriers for the family mutation, we designed PCR primers to flank the putative breakpoints, which reproducibly generated a 664-bp PCR product in the proband and in two obligate heterozygotes. The primers and sequences were: 50071F: 5′-GTTGAGACAAGGTCTTACCC-3′ (forward) and 56291R: 5′-CCTGATGGGTTTTGCTCTGT-3′ (reverse). PCR was carried out for 30 cycles at 94° for 1 min, 60° for 30 s, and 72° for 90 s. As a control for PCR fidelity, exon 13 of ATP7A with its associated splice donor and splice acceptor junctions (291-bp fragment) was amplified as previously described (28).

X-inactivation studies

X-inactivation patterns in this kinship were assessed for skewing with the human androgen-receptor locus (HUMARA) methylation assay (29). The assay was performed under standards and conditions certified according to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments which include quality assurance and use of normal control specimens. Digestion of genomic DNA with the methylation-sensitive restriction endonuclease, HpaII, and subsequent PCR amplification of the HUMARA polymorphic CAG repeat was used to determine X-inactivation status in female family members of child-bearing age. Inactivation ratios less than 80:20 were considered random. Ratios greater than or equal to 80:20 and less than or equal to 90:10 were considered moderately skewed. Ratios greater than 90:10 were considered highly skewed.

Results and discussion

Deletion breakpoint characterization and junction fragment screening

Using a multiplex PCR assay that amplifies each of the 23 exons of ATP7A (28), we detected deletion of exons 13 and 14 in the proband (data not shown). Deletion of these coding regions, which include 155 and 135 bp, respectively, predicts a translational reading frame shift: translation analysis (MACVECTOR) of the mutant sequence revealed substitution of two amino acids (LQ) after residue 876 (G), followed by a premature stop codon (UAG) at position 879 of the 1500-amino acid gene product. The actuator domain of ATP7A includes residues 806–924 and is required for the phosphatase step of the molecule’s catalytic cycle. The recently solved solution structure of this region (30) indicates protrusion of a catalytically important TGE loop (residues 875–877) from this region for interaction with the phosphorylated site in the ATP-binding domain. Deletion of exons 13 and 14 disrupts the TGE loop, converting this highly conserved motif to TGL and introducing the premature stop codon at position 879. Even if alternative splicing occurred through microRNAs or small nucleolar RNAs, the absence of a large portion of the actuator domain, disruption of the TGE phosphatase loop, and removal of an entire trans-membrane segment (31), components which are all encoded by exons 13 and/or 14, would prohibit bioactivity of the mutant copper ATPase. Characterization of a similar mutation, deletion of ATP7A exons 20–23, which eliminates an ATP-binding domain and two transmembrane segments, showed no residual copper transport capacity in a yeast complementation assay (20). Based on these combined analyses and comparisons, we therefore propose that the mutant ATP7A with deletion of exons 13 and 14 is completely non-functional. This is consistent with the suboptimal clinical outcome in the proband despite early identification and treatment, as noted in other patients with Menkes disease having severe ATP7A mutations (13, 20, 32).

Given that exons 12 and 15 were each detected in the proband via exon-specific PCR, the gene deletion appeared to involve the approximately 15-kb segment of ATP7A between these two coding regions (31). We utilized long PCR of genomic DNA from a normal control and the proband, using a primer pair that spanned the 3′ end of exon 12 to the 5′ end of exon 15. The PCR product obtained in normal control DNA was larger than a 12.2-kb DNA marker and in the proband was approximately 11 kb (data not shown). The proband’s PCR product was sequenced from both ends in stepwise fashion until the breakpoint was encountered. The deletion comprised 5557 bp in total (Fig. 1a), beginning at base 50,387 and ending at base 55,943 as referenced in a X-chromosome clone (RP3-465G10, GenBank accession number AL645821.1).

Fig. 1.

ATP7A deletion breakpoint. A map of the genomic DNA containing ATP7A exons 12 through 15 is shown. (a) Sequencing of the mutant allele from the proband led to identification of the breakpoints shown. (b) Primers (arrows) were designed to flank the region of the deletion to amplify a 664-bp junction fragment associated with the mutant allele. See Methods section for details.

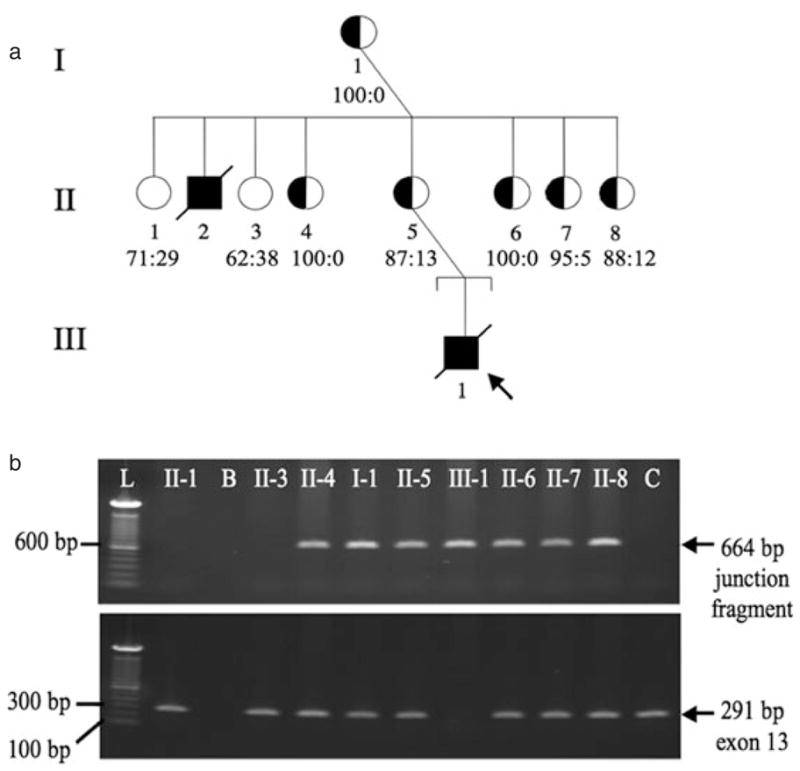

PCR using primers flanking the breakpoint (Fig. 1b) produced a 664-bp junction fragment in the proband (III-1, Fig. 2a) and two obligate heterozygotes (I-1 and II-5, Fig. 2a). Testing for the junction fragment (Fig. 2b) indicated that four of six at-risk females (II-4, II-6, II-7, and II-8) carried the deletion and two (II-1 and II-3) did not. As expected, exon 13 was amplified in all individuals tested except the proband (III-1). We subsequently used this junction fragment assay to exclude the diagnosis of Menkes disease in an at-risk male newborn (offspring of II-6, data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Molecular characterization of family with history of Menkes disease. (a) Three-generation family pedigree. Fully shaded squares indicate affected males; half-shaded circles indicate females heterozygous for ATP7A exon 13/14 deletion. Ratios underneath female symbols indicate the respective X-inactivation patterns (for female heterozygotes, ratios denote the percentage of cells with the mutant allele inactivated: percentage of cells with the normal allele inactivated). (b) Junction fragment assay. A 664-bp junction fragment is detected in four of six at-risk females: II-4, II-6, II-7, and II-8 (top panel). The fragment is not amplified in an unrelated normal female control (C). Lowermost panel: all family members, except the male proband (III-1), show amplification of ATP7A exon 13 (291 bp). L, ladder of molecular weight markers; B, blank.

X-inactivation results

The proband’s maternal grandmother (I-1) showed HUMARA allele sizes of 269 and 287 bp (Fig. 3a, top left panel). Analyses from the deletion-carrying maternal aunts (II-4, II-6, II-7, and II-8) showed that they all inherited a 281-bp HUMARA allele from their father and the 269-bp allele from their mother (I-1). In contrast, the proband’s maternal aunts who do not carry the ATP7A deletion (II-1 and II-3) each inherited the 281-bp paternal allele and the other (287 bp) maternal allele (data not shown), documenting that the 269-bp HUMARA allele originates from the same X chromosome as the ATP7A exon 13/14 deletion.

Fig. 3.

X-inactivation analyses. (a) The proband’s grandmother (I-1) has HUMARA allele sizes of 269 and 287 bp (top left panel). Individual II-4, and all other of the proband’s maternal aunts who are heterozygous for the exon 13/14 deletion, inherited allele 281 from their father and allele 269 from their mother (top right panel). In contrast, the non-carrier females in this family (II-1 and II-3) inherited the 287-bp HUMARA allele from their mother (data not shown). These results indicated that the 269-bp HUMARA allele originates from the X chromosome harboring the ATP7A exon 13/14 deletion. (b) Digestion of genomic DNA from each subject with the methylation-sensitive restriction endonuclease, HpaII, prior to polymerase chain reaction amplification yields only allele 269, representing the methylated, inactive X chromosome (bottom panels) and indicating completely skewed (100:0) inactivation of the X chromosome bearing the ATP7A deletion.

Digestion of genomic DNA from the deletion carriers with the methylation-sensitive restriction endonuclease, HpaII, and subsequent PCR amplification of the HUMARA CAG repeat showed marked predominance of the 269 bp allele, representing the methylated, inactive X, which was protected from HpaII digestion. Four of the female mutation carriers (I-1, II-4, II-6, and II-7) showed highly (≥95:5) skewed X-inactivation (Figs. 2a and 3), and the other two carriers (II-5 and II-8) showed moderate (≥87:13) skewing (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the X-inactivation patterns in the non-carrier females (II-1 and II-3) were random (inactivation ratios = 71:29 and 62:38, respectively; Fig. 2a).

This represents the first report of X-inactivation patterns in cytogenetically normal females heterozygous for mutation at the ATP7A locus. Our analysis revealed that all six female heterozygotes showed skewed X-inactivation, with preferential silencing of the mutant X chromosome in each instance. The phenomenon of favorable skewing in female carriers of deleterious traits has been observed for other X-linked diseases, including α-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome, Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, dyskeratosis congenita, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, severe combined immunodeficiency disease, and the MECP2 duplication syndrome, although exceptions have also been noted (6). Because there may be tissue-specific differences in X-chromosome inactivation (33, 34), we acknowledge that our results, obtained from peripheral blood, may not reflect the X-inactivation status of other organs and tissues in these subjects.

Several mechanisms can lead to skewed X-chromosome inactivation. The first is selection, whereby cells with a specific active X chromosome develop a selective growth advantage (4, 6, 27). This phenomenon has been documented in cultured cells from obligate carriers of Menkes disease (27, 35). Alternatively, one of the two X chromosomes per female cell may be silenced coordinately during early embryogenesis, with cis-acting alleles mediating gene repression (36, 37). Because the murine homolog of ATP7A, atp7a, appears to partially escape transcriptional silencing, with loss of epigenetic gene repression increasing over time (37, 38), it is possible that female carriers of Menkes disease could express mutant ATP7A from an inactivated X chromosome in some cells. This phenomenon could potentially modify clinical phenotypes in female carriers. Because ATP7A plays multiple roles in human physiology, including central nervous system development, neuronal activation, synaptogenesis, axon targeting, myelination, and motor neuron function, as well as contributing to hair, bone, and connective tissue integrity (11–13, 26, 39, 40), the scope of phenotypic manifestations could be quite broad.

Additional studies of X-inactivation patterns in obligate female carriers of ATP7A mutations, with careful clinical correlations, will be useful to determine whether the extreme skewing documented in this family is standard for this gene, and, in cases where it is not, whether deviation from this pattern has phenotypic consequences in females with a family history of Menkes disease, or its allelic variants, occipital horn syndrome (10), and ATP7A-related distal motor neuropathy (11).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the family for their participation and to Sarah Godwin for mutation identification in the proband. This work was supported by the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Footnotes

Favorably skewed X-inactivation accounts for neurological sparing in female carriers of Menkes disease.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest related to this work are noted by any of the six authors.

References

- 1.Heard E, Clerc P, Avner P. X-chromosome inactivation in mammals. Ann Rev Genet. 1997;31:571–610. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clerc P, Avner P. Random X-chromosome inactivation: skewing lessons for mice and men. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Migeon BR. Non-random X chromosome inactivation in mammalian cells. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1998;80:142–148. doi: 10.1159/000014971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van den Veyver IB. Skewed X inactivation in X-linked disorders. Semin Repro Med. 2001;19:183–191. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lexner MO, Bardow A, Juncker I, et al. X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Genetic and dental findings in 67 Danish patients from 19 families. Clin Genet. 2008;74:252–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ørstavik KH. X chromosome inactivation in clinical practice. Hum Genet. 2009;126:363–373. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0670-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vulpe C, Levinson B, Whitney S, Packman S, Gitschier J. Isolation of a candidate gene for Menkes disease and evidence that it encodes a copper-transporting ATPase. Nat Genet. 1993;3:7–13. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chelly J, Tümer Z, Tønnesen T, et al. Isolation of a candidate gene for Menkes disease that encodes a potential heavy metal binding protein. Nat Genet. 1993;3:14–19. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercer JF, Livingston J, Hall B, et al. Isolation of a partial candidate gene for Menkes disease by positional cloning. Nat Genet. 1993;3:20–25. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaler SG, Gallo LK, Proud VK, et al. Occipital horn syndrome and a mild Menkes phenotype associated with splice site mutations at the MNK locus. Nat Genet. 1994;8:195–202. doi: 10.1038/ng1094-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennerson ML, Nicholson GA, Kaler SG, et al. Missense mutations in the copper transporter gene ATP7A cause X-linked distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaler SG. Diagnosis and therapy of Menkes disease, a genetic form of copper deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:S1029–S1034. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.5.1029S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu PC, Chen YW, Centano J, Quesado M, Lem KE, Kaler SG. Downregulation of myelination, energy, and translational genes in Menkes disease brain. Molec Genet Metab. 2005;85:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petris MJ, Mercer JF, Culvenor JG, Lockhart P, Gleeson PA, Camakaris J. Ligand-regulated transport of the Menkes copper P-type ATPase efflux pump from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane: a novel mechanism of regulated trafficking. EMBO J. 1996;15:6084–6095. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaler SG, Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Salerno JA, Gahl WA. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid neurochemical pattern in Menkes disease. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:171–175. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein DS, Holmes CS, Kaler SG. Relative efficiencies of plasma catechol levels and ratios for neonatal diagnosis of Menkes disease. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:1464–1468. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9933-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steveson TC, Ciccotosto GD, Ma XM, Mueller GP, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Menkes protein contributes to the function of peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase. Endocrinology. 2003;144:188–200. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godwin SC, Shawker T, Chang M, Kaler SG. Brachial artery aneurysms in Menkes disease. J Pediatr. 2006;149:412–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price D, Ravindranath T, Kaler SG. Internal jugular phlebectasia in Menkes disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolarygol. 2007;71:1145–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaler SG, Holmes CS, Goldstein DS, et al. Neonatal diagnosis and treatment of Menkes disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:605–614. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang J, Robertson S, Lem KE, Godwin SC, Kaler SG. Functional copper transport explains neurologic sparing in occipital horn syndrome. Genet Med. 2006;8:711–718. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000245578.94312.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tümer Z, Horn N. Menkes disease: underlying genetic defect and new diagnostic possibilities. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21:604–612. doi: 10.1023/a:1005479307906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sirleto P, Surace C, Santos H, et al. Lyonization effects of the t(X;16) translocation on the phenotypic expression in a rare female with Menkes disease. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:347–351. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181973b4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leisti JT, Kaback MM, Rimoin DL. Human X-autosome translocations: differential inactivation of the X chromosome in a kindred with an X-9 translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1975;27:441–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volpintesta EJ. Menkes kinky hair syndrome in a black infant. Am J Dis Child. 1974;128:244–246. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1974.02110270118024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore CM, Howell RR. Ectodermal manifestations in Menkes disease. Clin Genet. 1985;28:532–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horn N. Menkes X-linked disease: heterozygous phenotype in uncloned fibroblast cultures. J Med Genet. 1980;17:257–261. doi: 10.1136/jmg.17.4.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu PC, McAndrew PE, Kaler SG. Rapid and robust screening of the Menkes disease/occipital horn syndrome gene. Genet Test. 2002;6:255–260. doi: 10.1089/10906570260471778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen RC, Zoghbi HY, Moseley AB, Rosenblatt HM, Belmont JW. Methylation of HpaII and HhaI sites near the polymorphic CAG repeat in the human androgen receptor gene correlates with X chromosome inactivation. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:1229–1239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banci L, Bertini I, Cantini F, et al. Solution structures of the actuator domain of ATP7A and ATP7B, the Menkes and Wilson disease proteins. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7849–7855. doi: 10.1021/bi901003k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tümer Z, Vural B, Tønnesen T, Chelly J, Monaco AP, Horn N. Characterization of the exon structure of the Menkes disease gene using vectorette PCR. Genomics. 1995;26:437–442. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80160-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaler SG, Buist NR, Holmes CS, Goldstein DS, Miller RC, Gahl WA. Early copper therapy in classic Menkes disease patients with a novel splicing mutation. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:921–928. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharp A, Robinson D, Jacobs P. Age- and tissue-specific variation of X chromosome inactivation ratios in normal women. Hum Genet. 2000;107:343–349. doi: 10.1007/s004390000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bittel DC, Theodoro MF, Kibiryeva N, Fischer W, Talebizadeh Z, Butler MG. Comparison of X-chromosome inactivation patterns in multiple tissues from human females. J Med Genet. 2008;45:309–313. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.055244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horn N. Menkes’ X-linked disease: prenatal diagnosis and carrier detection. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1983;6 (Suppl 1):59–62. doi: 10.1007/BF01811325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chadwick LH, Pertz LM, Broman KW, Barolomei MS, Willard HF. Genetic control of X chromosome inactivation in mice: definition of the Xce candidate interval. Genetics. 2006;173:2103–2110. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.054882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenwood AD, Southard-Smith EM, Galecki AT, Burke DT. Coordinate control and variation in X-linked gene expression among female mice. Mamm Genome. 1997;8:818–822. doi: 10.1007/s003359900585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bennett-Baker PE, Wilkowski J, Burke DT. Age-associated activation of epigenetically repressed genes in the mouse. Genetics. 2003;165:2055–2062. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlief ML, Craig AM, Gitlin JD. NMDA receptor activation mediates copper homeostasis in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:239–246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3699-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El Meskini R, Crabtree KL, Cline LB, Mains RE, Eipper BA, Ronnett GV. ATP7A (Menkes protein) functions in axonal targeting and synaptogenesis. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]