Abstract

Background

Acupuncture is often used for tension-type headache prophylaxis but its effectiveness is still controversial. This review (along with a companion review on ‘Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis’) represents an updated version of a Cochrane review originally published in Issue 1, 2001, of The Cochrane Library.

Objectives

To investigate whether acupuncture is a) more effective than no prophylactic treatment/routine care only; b) more effective than ‘sham’ (placebo) acupuncture; and c) as effective as other interventions in reducing headache frequency in patients with episodic or chronic tension-type headache.

Search strategy

The Cochrane Pain, Palliative & Supportive Care Trials Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field Trials Register were searched to January 2008.

Selection criteria

We included randomized trials with a post-randomization observation period of at least 8 weeks that compared the clinical effects of an acupuncture intervention with a control (treatment of acute headaches only or routine care), a sham acupuncture intervention or another intervention in patients with episodic or chronic tension-type headache.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers checked eligibility; extracted information on patients, interventions, methods and results; and assessed risk of bias and quality of the acupuncture intervention. Outcomes extracted included response (at least 50% reduction of headache frequency; outcome of primary interest), headache days, pain intensity and analgesic use.

Main results

Eleven trials with 2317 participants (median 62, range 10 to 1265) met the inclusion criteria. Two large trials compared acupuncture to treatment of acute headaches or routine care only. Both found statistically significant and clinically relevant short-term (up to 3 months) benefits of acupuncture over control for response, number of headache days and pain intensity. Long-term effects (beyond 3 months) were not investigated. Six trials compared acupuncture with a sham acupuncture intervention, and five of the six provided data for meta-analyses. Small but statistically significant benefits of acupuncture over sham were found for response as well as for several other outcomes. Three of the four trials comparing acupuncture with physiotherapy, massage or relaxation had important methodological or reporting shortcomings. Their findings are difficult to interpret, but collectively suggest slightly better results for some outcomes in the control groups.

Authors’ conclusions

In the previous version of this review, evidence in support of acupuncture for tension-type headache was considered insufficient. Now, with six additional trials, the authors conclude that acupuncture could be a valuable non-pharmacological tool in patients with frequent episodic or chronic tension-type headaches.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Acupuncture Therapy [*methods], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Tension-Type Headache [*prevention & control]

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Acupuncture for tension-type headache

Patients with tension-type headache suffer from episodes of pain which is typically bilateral (affects both sides of the head), pressing or tightening in quality, mild to moderate in intensity, and which does not worsen with routine physical activity. In most patients tension-type headache occurs infrequently and there is no need for further treatment beyond over-the-counter pain killers. In some patients, however, tension-type headache occurs on several days per month or even daily. Acupuncture is a therapy in which thin needles are inserted into the skin at defined points; it originates from China. Acupuncture is used in many countries for tension-type headache prophylaxis - that is, to reduce the frequency and intensity of tension-type headaches.

We reviewed 11 trials which investigated whether acupuncture is effective in the prophylaxis of tension-type headache. Two large trials investigating whether adding acupuncture to basic care (which usually involves only treating unbearable pain with pain killers) found that those patients who received acupuncture had fewer headaches. Forty-seven percent of patients receiving acupuncture reported a decrease in the number of headache days by at least 50%, compared to 16% of patients in the control groups. Six trials compared true acupuncture with inadequate or ‘fake’ acupuncture interventions in which needles were either inserted at incorrect points or did not penetrate the skin. Overall, these trials found slightly better effects in the patients receiving the true acupuncture intervention. Fifty percent of patients receiving true acupuncture reported a decrease of the number of headache days by at least 50%, compared to 41% of patients in the groups receiving inadequate or ‘fake’ acupuncture. Three of the four trials in which acupuncture was compared to physiotherapy, massage or relaxation had important methodological shortcomings. Their findings are difficult to interpret, but collectively suggest slightly better results for some outcomes with the latter therapies. In conclusion, the available evidence suggests that acupuncture could be a valuable option for patients suffering from frequent tension-type headache.

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Patients with tension-type headache suffer from episodes of pain which is typically bilateral, pressing or tightening in quality and of mild to moderate intensity, and which does not worsen with routine physical activity (IHS 2004). There is no nausea, but photophobia or phonophobia may be present. Infrequent episodic tension-type headache (episodes of headache lasting minutes to days which occur less than once per month) has no important impact on individuals. If headaches occur on at least one day, but less than 15 days per month, this is classified as frequent episodic tension-type headache. In some patients this can evolve to chronic tension-type headache (on 15 or more days per month). Tension-type headache should not be confused with migraine, which is characterized by recurrent attacks of mostly one-sided, severe headache, although some patients suffer from both types of headaches. Tension-type headache is the most common type of primary headache, and the disability attributable to it is larger worldwide than that due to migraine (Stovner 2007). Epidemiological studies report highly variable prevalences depending on case definition and country ( Stovner 2007). According to the International Headache Society (IHS), lifetime prevalence in the general population varies between 30% and 78% (IHS 2004). If headache episodes are not too frequent (up to a maximum of 10 days per month), unbearable pain can be treated with analgesic drugs or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Pfaffenrath 1998). In patients with chronic tension-type headache, guidelines recommend antidepressants such as amitriptyline (Pfaffenrath 1998). In addition to, or instead of drug therapy, behavioral interventions such as relaxation or biofeedback have been shown to be beneficial (McCrory 2000). However, additional effective intervention tools with good tolerability are desirable.

Description of the intervention

Acupuncture in the context of this review is defined as the needling of specific points of the body. It is one of the most widely used complementary therapies in many countries (Bodeker 2005). For example, according to a population-based survey in the year 2002 in the United States, 4.1% of the respondents reported lifetime use of acupuncture, and 1.1% recent use (Burke 2006). A similar survey in Germany performed in the same year found that 8.7% of adults between 18 and 69 years of age had received acupuncture treatment in the previous 12 months (Härtel 2004). Acupuncture was originally developed as part of Chinese medicine wherein the purpose of treatment is to bring the patient back to the state of equilibrium postulated to exist prior to illness (Endres 2007). Some acupuncture practitioners have dispensed with these concepts and understand acupuncture in terms of conventional neurophysiology. Acupuncture is often used as a intervention to reduce the frequency and intensity of headaches. For example, 9.9% of the acupuncture users in the U.S. survey mentioned above stated that they had used acupuncture for treating migraine or other headaches (Burke 2006). Practitioners typically claim that a short course of treatment, such as 12 sessions over a 3-month period, can have a long-term impact on the frequency and intensity of headache episodes.

How the intervention might work

Multiple studies have shown that acupuncture has short-term effects on a variety of physiological variables relevant to analgesia ( Bäcker 2004; Endres 2007). However, it is unclear to what extent these observations from experimental settings are relevant to the long-term effects reported by practitioners. It is assumed that a variable combination of peripheral effects; spinal and supraspinal mechanisms; and cortical, psychological or ‘placebo’ mechanisms contribute to the clinical effects in routine care (Carlsson 2002). While there is little doubt that acupuncture interventions cause neurophysiological changes in the organism, the traditional concepts of acupuncture involving specifically located points on a system of ‘channels’ called meridians are controversial (Kaptchuk 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

As in many other clinical areas, the findings of controlled trials of acupuncture for tension-type and other headaches have not been conclusive in the past. In 1999 we published a first version of our review on acupuncture for idiopathic headache (Melchart 1999), and in 2001 we published an updated version in The Cochrane Library (Melchart 2001). In our 2001 update, we concluded that “overall, the existing evidence supports the value of acupuncture for the treatment of idiopathic headaches. However, the quality and the amount of evidence are not fully convincing.” In recent years several rigorous, large trials have been undertaken. Due to the increasing number of studies, and for clinical reasons, we decided to split our previous review on idiopathic headache into two separate reviews on migraine (Linde 2009) and tension-type headache for the present update.

OBJECTIVES

We aimed to investigate whether acupuncture is a) more effective than no prophylactic treatment/routine care only; b) more effective than ‘sham’ (placebo) acupuncture; and c) as effective as other interventions in reducing the frequency of headaches in patients with tension-type headache.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included controlled trials in which allocation to treatment was explicitly randomized, and in which patients were followed up for at least 8 weeks after randomization. Trials in which a clearly inappropriate method of randomization (for example, open alternation) was used were excluded.

Types of participants

Trials conducted among adult patients with episodic and/or chronic tension-type headache were included. Studies including patients with headaches of various types (e.g., 50% patients with migraine and 50% patients with tension-type headache) were excluded unless separate results were presented for patients with tension-type headache.

Types of interventions

The treatments considered had to involve needle insertion at acupuncture points, pain points or trigger points, and had to be described as acupuncture. Studies investigating other methods of stimulating acupuncture points without needle insertion (for example, laser stimulation or transcutaneous electrical stimulation) were excluded.

Control interventions considered were:

no treatment other than treatment of acute headaches or routine care (which typically includes acute treatment, but might also include other treatments; however, trials normally require that no new experimental or standardized treatment be initiated during the trial period);

sham interventions (interventions mimicking ‘true’ acupuncture/true treatment, but deviating in at least one aspect considered important by acupuncture theory, such as skin penetration or correct point location);

other treatment (drugs, relaxation, physical therapies, etc.).

Trials that only compared different forms of acupuncture were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Studies were included if they reported at least one clinical outcome related to headache (for example, response, frequency, pain intensity, headache scores, analgesic use). Trials reporting only physiological or laboratory parameters were excluded, as were trials with outcome measurement periods of less than 8 weeks (from randomization to final observation).

Search methods for identification of studies

(See also: Pain, Palliative & Supportive Care Group methods used in reviews.)

For our previous versions of the review on idiopathic headache ( Melchart 1999; Melchart 2001), we used a very broad search strategy to identify as many references on acupuncture for headaches as possible, as we also aimed to identify non-randomized studies for an additional methodological investigation (Linde 2002). The sources searched for the 2001 version of the review were:

MEDLINE 1966 to April 2000;

EMBASE 1989 to April 2000;

Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field Trials Register;

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 1, 2000);

individual trial collections and private databases;

bibliographies of review articles and included studies.

The search terms used for the electronic databases were ‘(acupuncture or acupressure)’ and ‘(headache or migraine)’. In the years following publication of the 2001 review, the first authors regularly checked PubMed and CENTRAL using the same search terms. For the present update, detailed search strategies were developed for each database searched (see Appendix 1). These were based on the search strategy developed for MEDLINE, revised appropriately for each database. The MEDLINE search strategy combined a subject search strategy with phases 1 and 2 of the Cochrane Sensitive Search Strategy for RCTs (as published in Appendix 5b2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 4.2 6 (updated Sept 2006)). Detailed strategies for each database searched are provided in Appendix 1.

The following databases were searched for this update:

Cochrane Pain, Palliative & Supportive Care Trials Register to January 2008;

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 4, 2007);

MEDLINE updated to January 2008;

EMBASE updated to January 2008;

Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field Trials Register updated to January 2008.

In addition to the formal searches, one of the reviewers (KL) regularly checked (last search 15 April 2008) all new entries in PubMed identified by a simple search combining acupuncture AND headache, checked available conference abstracts and asked researchers in the field about new studies. Ongoing or unpublished studies were identified by searching three clinical trial registries (http://clinicaltrials.gov/, http://www.anzctr.org.au, and http://www.controlled-trials.com/mrct/; last update 15 April 2008).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All abstracts identified by the updated search were screened by one reviewer (KL), who excluded those that were clearly irrelevant (for example, studies focusing on other conditions, reviews, etc.). Full texts of all remaining references were obtained and were again screened to exclude clearly irrelevant papers. All other articles and all trials included in our previous review of acupuncture for idiopathic headache were then formally checked by at least two reviewers for eligibility according to the above-mentioned selection criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

Information on patients, methods, interventions, outcomes and results was extracted independently by at least two reviewers using a specially designed form. In particular, we extracted exact diagnoses; headache classifications used; number and type of centres; age; sex; duration of disease; number of patients randomized, treated and analyzed; number of, and reasons for dropouts; duration of baseline, treatment and follow-up periods; details of acupuncture treatments (such as selection of points; number, frequency and duration of sessions; achievement of de-chi (an irradiating feeling considered to indicate effective needling); number, training and experience of acupuncturists); and details of control interventions (sham technique, type and dosage of drugs). For details regarding methodological issues and study results, see below.

Where necessary, we sought additional information from the first or corresponding authors of the included studies.

Assessment of risk of bias

For the assessment of study quality, the new risk of bias approach for Cochrane reviews was used (Higgins 2008). We used the following six separate criteria:

Adequate sequence generation;

Allocation concealment;

Blinding;

Incomplete outcome data addressed (up to 3 months after randomization);

Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed (4 to 12 months after randomization);

Free of selective reporting.

We did not include the item ‘other potential threats to validity’ in a formal manner, but noted if relevant flaws were detected. In a first step, information relevant for making a judgment on a criterion was copied from the original publication into an assessment table. If additional information from study authors was available, this was also entered in the table, along with an indication that this was unpublished information. At least two reviewers independently made a judgment whether the risk of bias for each criterion was considered low, high or unclear. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

For the operationalization of the first five criteria, we followed the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). For the ‘selective reporting’ item, we decided to use a more liberal definition following discussion with two persons (Julian Higgins and Peter Jüni) involved in the development of the Handbook guidelines. Headache trials typically measure a multiplicity of headache outcomes at several time points using diaries, and there is a plethora of slightly different outcome measurement methods. While a single primary endpoint is sometimes predefined, the overall pattern of a variety of outcomes is necessary to get a clinically interpretable picture. If the strict Handbook guidelines had been applied, almost all trials would have been rated ‘unclear’ for the ‘selective reporting’ item. We considered trials as having a low risk of bias for this item if they reported the results of the most relevant headache outcomes assessed (typically a frequency measure, intensity, analgesic use and response) for the most relevant time points (end of treatment and, if done, follow-up), and if the outcomes and time points reported made it unlikely that authors had picked them out because they were particularly favorable or unfavorable.

Trials that met all criteria, or all but one criterion, were considered to be of higher quality. Some trials had both blinded sham control groups and unblinded comparison groups receiving no prophylactic treatment or drug treatment. In the risk of bias tables, the ‘Judgement’ column always relates to the comparison with sham interventions. In the ‘Description’ column, we also include the assessment for the other comparison group(s). As the risk of bias table does not include a ‘not applicable’ option, the item ‘incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed (4 to 12 months after randomization)?’ was rated as ‘unclear’ for trials that did not follow patients longer than 3 months.

Assessment of the adequacy of the acupuncture intervention

We also attempted to provide a crude estimate of the quality of acupuncture. Two reviewers (mostly GA and BB, or, for trials in which one of these reviewers was involved, AW) who are trained in acupuncture and have several years of practical experience answered two questions. First, they were asked how they would treat the patients included in the study. Answer options were ‘exactly or almost exactly the same way’, ‘similarly’, ‘differently’, ‘completely differently’ or ‘could not assess’ due to insufficient information (on acupuncture or on the patients). Second, they were asked to rate their degree of confidence that acupuncture was applied in an appropriate manner on a 100-mm visual scale (with 0% = complete absence of evidence that the acupuncture was appropriate, and 100% = total certainty that the acupuncture was appropriate). The latter method was proposed by a member of the review team (AW) and has been used in a systematic review of clinical trials of acupuncture for back pain (Ernst 1998). In the Characteristics of included studies table, the acupuncturists’ assessments are summarized under ‘Methods’ (for example, ‘similarly/70%’ indicates a trial where the acupuncturist-reviewer would treat ‘similarly’ and is 70% confident that acupuncture was applied appropriately).

Comparisons for analysis

For the purposes of summarizing results, the included trials were categorized according to control groups: 1) comparisons with no acupuncture (treatment of acute headaches only or routine care); 2) comparisons with sham acupuncture interventions; and 3) comparisons with other treatments.

Outcomes for effect size estimation

We defined four time windows for which we tried to extract and analyze study findings:

Up to 8 weeks/2 months after randomization;

3 to 4 months after randomization;

5 to 6 months after randomization; and

More than 6 months after randomization.

In all included studies acupuncture treatment started immediately or very soon after randomization.

If more than one data point were available for a given time window, we used: for the first time window, preferably data closest to 8 weeks; for the second window, data closest to the 4 weeks after completion of treatment (for example, if treatment lasted 8 weeks, data for weeks 9 to 12); for the third window, data closest to 6 months; and for the fourth window, data closest to 12 months. We extracted data for the following outcomes:

Proportion of ‘responders’. For trials investigating the superiority of acupuncture compared to no acupuncture or sham intervention, we used, if available, the number of patients with a reduction of at least 50% in the number of headache days per 4 weeks and divided it by the number of patients randomized to the respective group. In studies comparing acupuncture with other therapies, we used for the denominator the number of patients analyzed. If the number of responders regarding headache days was not available, we used global assessment measures by patients or physicians. We calculated responder rate ratios (relative risk of having a response) and 95% confidence intervals as effect size measures.

Number of headache days (means and standard deviations) per 4-week period (calculation of weighted mean differences).

Headache intensity (any measures available, extraction of means and standard deviations, calculation of standardized mean differences).

Frequency of analgesic use (any continuous or rank measures available, extraction of means and standard deviations, calculation of standardized mean differences).

Headache score (any measures available, extraction of means and standard deviations, calculation of standardized mean differences).

For continuous measures, we used, if available, the data from intention-to-treat analyses with missing values replaced; otherwise we used the presented data on available cases.

All these outcomes rely on patient reports, mainly collected in headache diaries.

Main outcome measure

The main outcome measure was the proportion of responders for the 3- to 4-month window (close to the end of the treatment cycle and a time point for which outcome data are often available).

Meta-analysis

Pooled random-effects estimates, their 95% confidence intervals, the Chi2-test for heterogeneity and the I2-statistic were calculated for each time window for each of the outcomes listed above for the comparison with sham interventions. Due to the variable study methods, pooled effect size estimates have to be interpreted with great caution. We did not pool findings from the studies for the other comparisons (see Results for an explanation).

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Selection process

In our previous review on idiopathic headache (Melchart 2001), we evaluated 26 trials that included 1151 participants with various types of headaches. The search update identified a total of 251 new references. Full reports for one tension-type headache trial (Jena 2008) that was reported only as a published conference abstract at the time of completion of the literature search (January 2008) were later identified through personal contacts with authors. Most of the references identified by the search update were excluded at the first screening step by one reviewer, as they were clearly irrelevant. The most frequent reasons for exclusion at this level were: article was a review or a commentary; studies of non-headache conditions; studies in patients suffering from migraine; clearly non-randomized design; and investigation of an intervention which was not true acupuncture involving skin penetration. A total of 55 full-text papers were then formally assessed by at least two reviewers for eligibility. Thirty-one studies reported in 34 publications did not meet the selection criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies). The most frequent reason for exclusion was that patients did not suffer from tension-type headache, or that patients with mixed pain or mixed headaches had been included without presentation of a subgroup analysis for tension-type headache patients (13 trials). Other common reasons for exclusion were: post-randomization observation periods of less than 8 weeks (4 trials including 2 cross-over trials with less than 8 weeks per period); doubts about whether allocation was randomized (3 trials); and use of laser acupuncture (no skin penetration; 3 trials).

Eleven trials described in 21 publications (including published protocols and papers reporting additional aspects such as treatment details or cost-effectiveness analyses) met all selection criteria and were included in the review. The total number of study participants was 2317. Five of the 11 included trials (Ahonen 1984; Carlsson 1990; Tavola 1992; White 1996; Wylie 1997) had been included in our previous review; the remaining six (Endres 2007; Jena 2008; Karst 2001; Melchart 2005; Söderberg 2006; White 2000) are new.

Availability of additional information from authors

We received additional data relevant for effect size calculation from the authors of four studies (Endres 2007; Jena 2008; Karst 2001; Melchart 2005). Some additional information were received for a further three trials (Carlsson 1990; Söderberg 2006; Wylie 1997). In two trials, additional information were not needed ( White 1996; White 2000), and for two older trials, we were unable to contact study authors (Ahonen 1984; Tavola 1992).

Study characteristics

A total of 2317 patients with tension-type headache were included in the studies (median 62, range 10 to 1265). Five were multi-center trials (Endres 2007; Jena 2008; Melchart 2005; Söderberg 2006; White 2000); the remaining six were performed in a single centre. Four trials originated from Germany (Endres 2007; Jena 2008; Karst 2001; Melchart 2005), three from the UK (White 1996; White 2000; Wylie 1997), two from Sweden (Carlsson 1990; Söderberg 2006) and one each from Finland (Ahonen 1984) and Italy (Tavola 1992).

Two trials (White 1996; White 2000) included only patients with episodic tension-type headache, and two (Carlsson 1990; Söderberg 2006) only patients with chronic tension-type headache. The remaining trials either explicitly stated that they included both forms (Endres 2007; Jena 2008; Karst 2001; Melchart 2005) or made no clear statement (Ahonen 1984; Tavola 1992; Wylie 1997).

All trials used a parallel-group design (no cross-over trials). Nine trials had two groups (one acupuncture group and one control group), and two trials had two control groups (Melchart 2005; Söderberg 2006). In two trials acupuncture was compared to routine care (Jena 2008) or treatment of acute headaches only ( Melchart 2005). Six trials used a sham control but the actual techniques varied. In three trials, non-acupuncture points were needled (Endres 2007; Melchart 2005; Tavola 1992), while in the remaining three (Karst 2001; White 1996; White 2000) non-skin-penetrating techniques were used (see Characteristics of included studies for details). Three trials (Ahonen 1984; Carlsson 1990; Söderberg 2006) compared acupuncture with physiotherapy; one of these (Söderberg 2006) had an additional relaxation control group. Wylie 1997 compared acupuncture with a combination of massage and relaxation. There was no trial comparing acupuncture with prophylactic drug treatment.

The largest study by far (Jena 2008) used a quite unusual approach and has to be described in greater detail. In this very large, highly pragmatic study, 15,056 headache patients recruited by more than 4000 physicians in Germany were included. A total of 11,874 patients not giving consent to randomization received up to 15 acupuncture treatments within 3 months and were followed for an additional 3 months. This was also the case for 1613 patients randomized to immediate acupuncture, while the remaining 1569 patients remained on routine care (not further defined) for 3 months and then received acupuncture. The published analysis of this trial is on all randomized patients, but the authors provided us with unpublished results of subgroup analyses on the 1265 patients with tension-type headache. The large number of practitioners involved and the pragmatic approach make it likely that there is some diagnostic uncertainty whether all patients truly had tension-type headache.

The number of acupuncture sessions varied between 6 and 15. Three trials (Jena 2008; Tavola 1992; Wylie 1997) selected acupuncture points in an individualized manner, and seven (Ahonen 1984; Endres 2007; Karst 2001; Melchart 2005; Söderberg 2006; White 1996; White 2000) in a semi-standardized manner (either by having some mandatory points in all patients plus individualized points, or by using predefined point selections depending on syndrome diagnoses according to Chinese medicine); one trial (Carlsson 1990) used a standardized point selection. In two trials (White 1996; White 2000), brief needling was used (needles inserted for a few seconds only). For one trial (Carlsson 1990), both acupuncturist-reviewers considered the treatment ‘inadequate’. Both acupuncturist-reviewers would have used different treatment approaches for the patients in a further four trials (Ahonen 1984; Karst 2001; Söderberg 2006; White 2000). In trials using individualized strategies, assessments were difficult because of a lack of detail about the actual interventions used.

Post-randomization observation periods varied between 8 and 64 weeks. Apart from three trials (Ahonen 1984; Carlsson 1990; Jena 2008), all trials used diaries for the measurement of the most important headache outcomes. All but two trials (Ahonen 1984; Jena 2008) included a baseline observation period before randomization. The trials comparing acupuncture to other therapies rarely presented their findings in a manner allowing effect size calculation, while for trials comparing acupuncture with no acupuncture or sham acupuncture, effect size estimates could be calculated for the most relevant outcomes.

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of trials varied significantly. Newer trials tended to be of higher quality than older trials. An adequate method of sequence generation was reported for six trials (Endres 2007; Jena 2008; Karst 2001; Melchart 2005; White 1996; White 2000), and an adequate method for allocation concealment for five (Endres 2007; Jena 2008; Melchart 2005; White 1996; White 2000). Patients were blinded only in the six sham-controlled trials. Attrition was low or adequately accounted for in analyses up to 3 months after randomization in seven trials (Endres 2007; Jena 2008; Karst 2001; Melchart 2005; Söderberg 2006; Tavola 1992; White 2000), and in three (Endres 2007; Melchart 2005; Tavola 1992) of seven trials that had a follow-up longer than 3 months. One study (White 1996) met all formal quality criteria, but was a very small pilot trial (n = 10) with relevant baseline differences and so could not be interpreted reliably.

Effects of interventions

Comparisons with routine care/treatment of acute headaches only

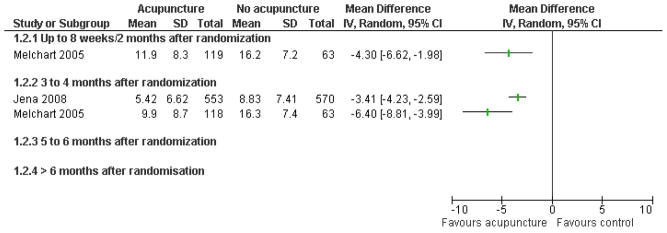

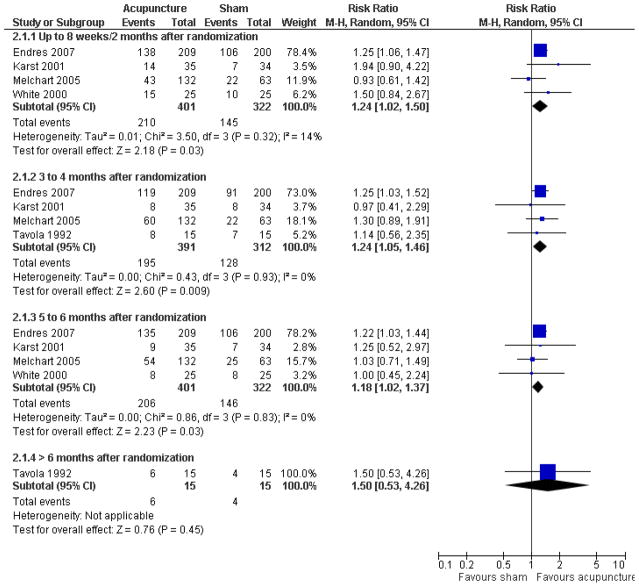

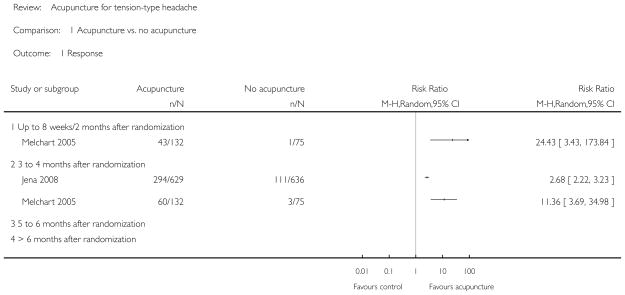

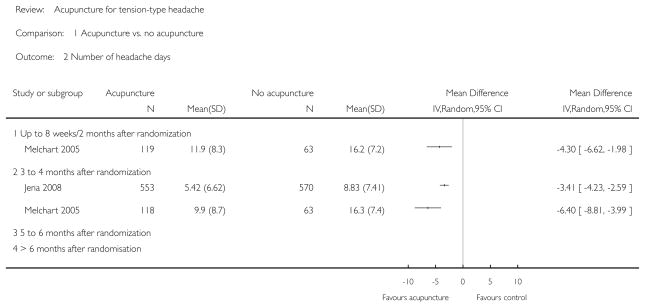

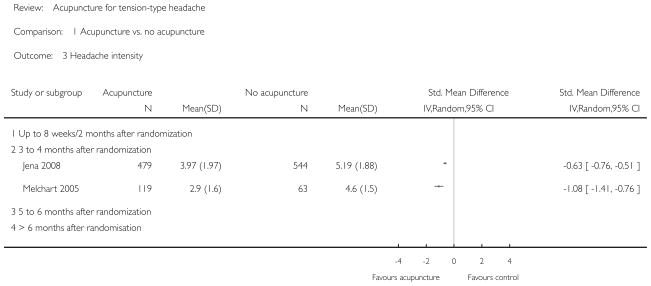

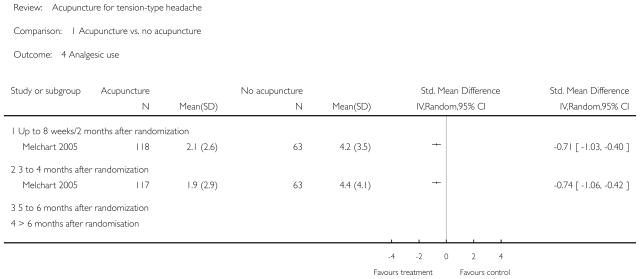

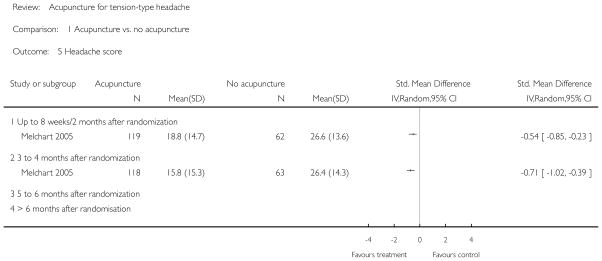

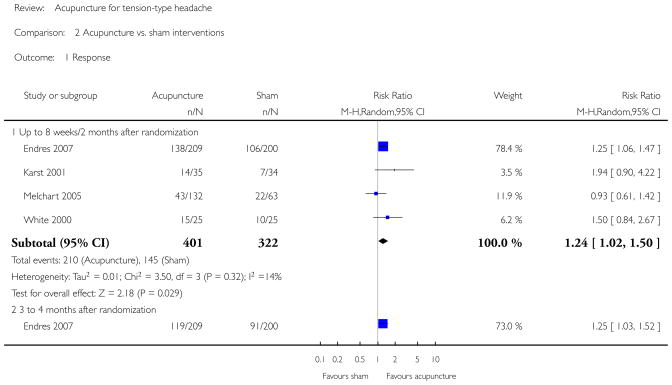

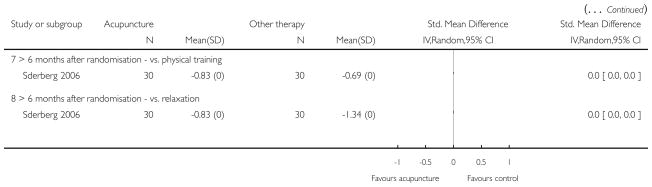

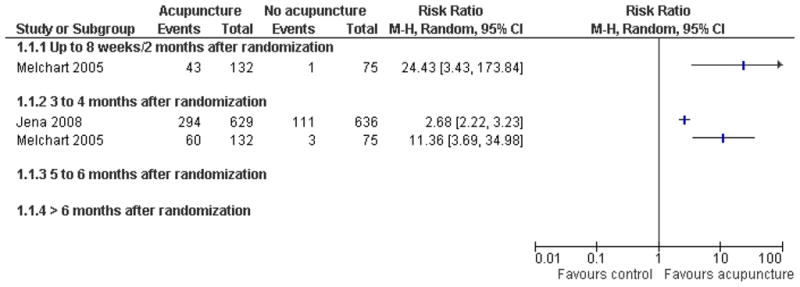

The two trials comparing acupuncture to routine care only (Jena 2008) or treatment of acute headaches only (Melchart 2005) were unblinded but otherwise had a low risk of bias. In both trials, patients received acupuncture 3 months after randomization (waiting list condition), so it is only possible to assess short-term effects up to 3 months after start of the treatment. We did not calculate pooled effect size estimates, as the two control groups and patient samples differed. The patients included in Melchart 2005 had much more frequent headaches at baseline (mean 17.6 days) than those in Jena 2008 (7.0 days). Both studies found significant benefits of acupuncture over control for the outcomes responder rate (Figure 1), headache frequency (Figure 2) and intensity (Analysis 1.3). Effects were larger in the trial comparing acupuncture to acute treatment only (Melchart 2005) than in the trial in which acupuncture was compared to routine care (Jena 2008). Responder rate ratios were 11.36 (95% confidence interval 3.69 to 34.98; 45% responders in the acupuncture group vs. 4% in the control group) and 2.68 (2.22 to 3.23; 47% vs. 17%), respectively. The differences between acupuncture and waiting list groups for number of headache days at 3 months were 6.4 days (3.99 to 8.81) and 3.41 days (2.59 to 4.23), respectively. Only one trial measured analgesic use and a headache score (Melchart 2005); there were significantly better results in the acupuncture groups (Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.5).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, outcome: 1.1 Response.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, outcome: 1.2 Number of headache days.

Comparisons with sham treatment

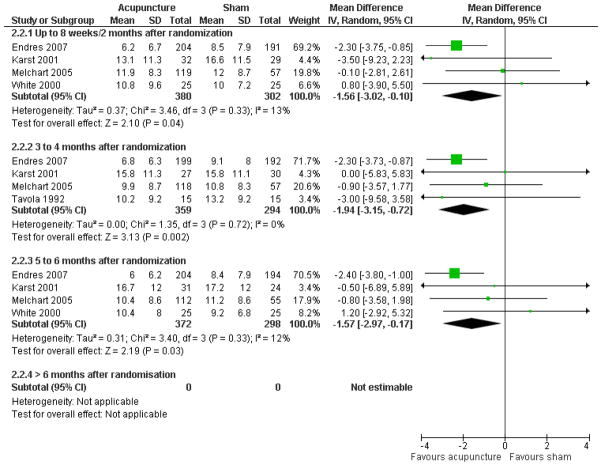

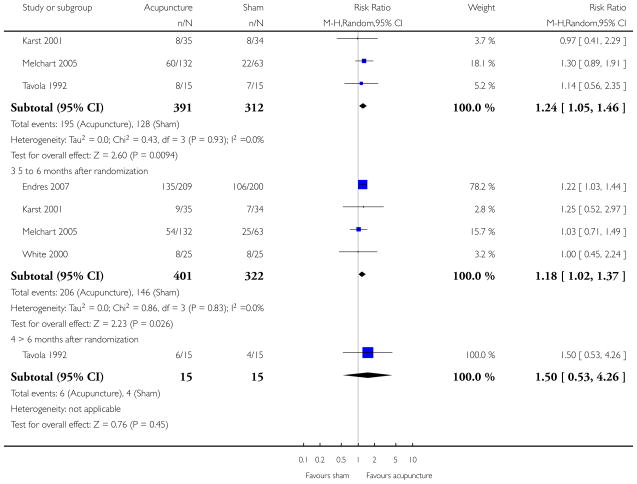

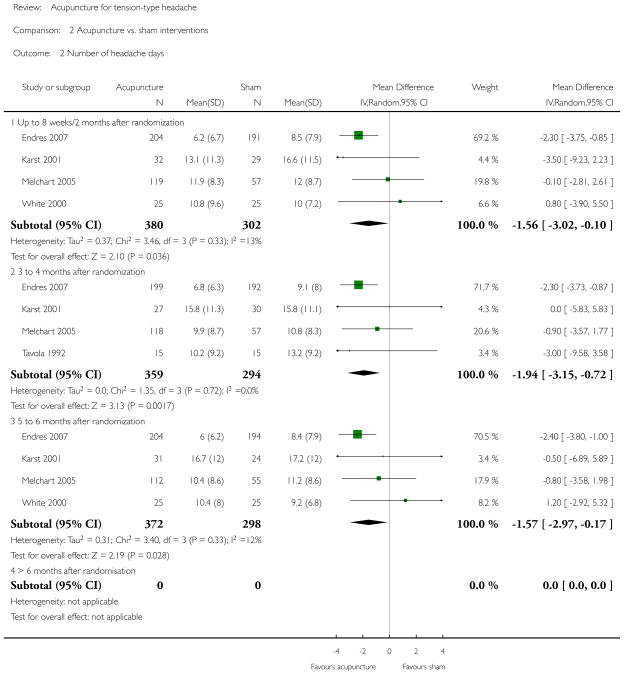

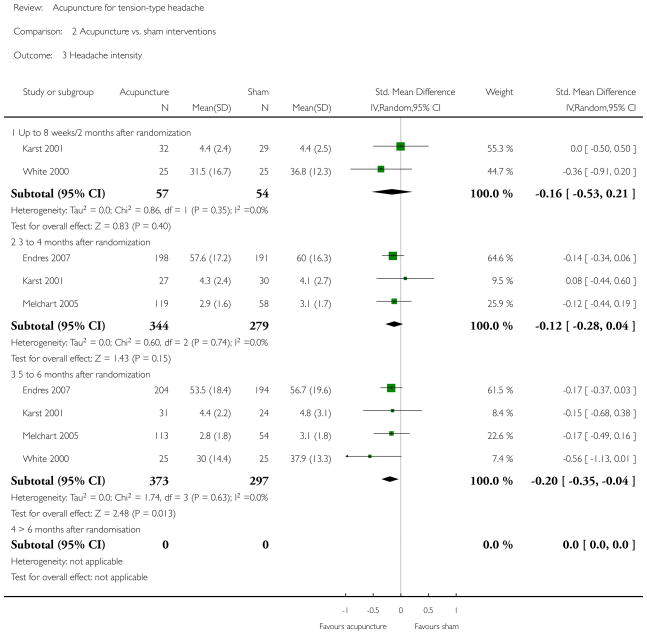

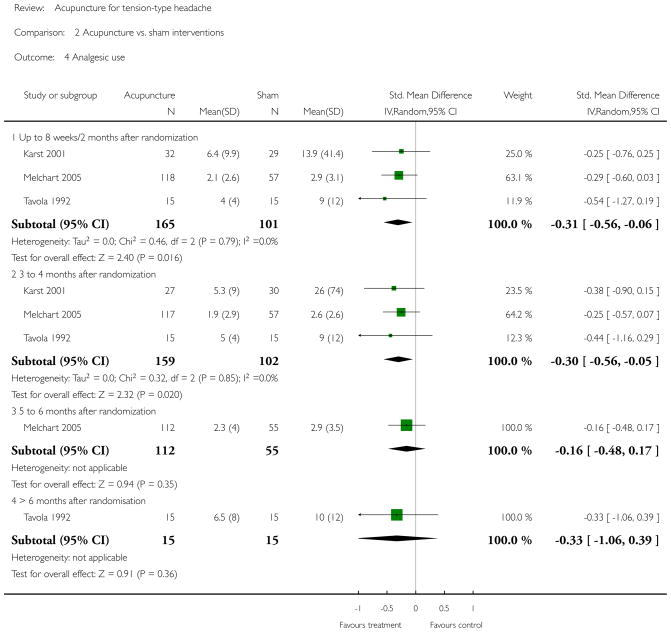

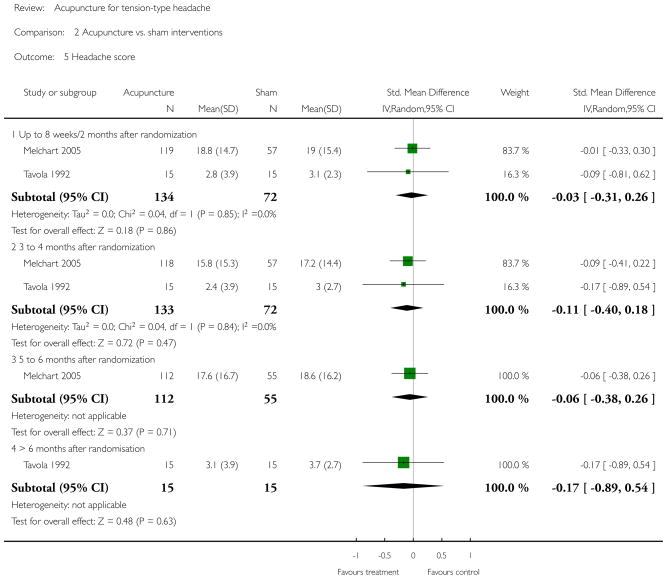

The five interpretable trials (Endres 2007; Karst 2001; Melchart 2005; Tavola 1992; White 2000) with sham comparisons all had comparably good quality despite some problems with attrition during long-term follow-up (Karst 2001; White 2000) and some uncertainties regarding the details of randomization (Karst 2001; Tavola 1992). Four trials had follow-up periods of about 6 months after randomization, and one more than 12 months (Tavola 1992). Only one trial (Endres 2007) found significant differences in regard to response (Figure 3) and number of headache days per 4 weeks (Figure 4) for the first three time windows. As this trial is by far the largest, it dominated the meta-analyses (around 70% weight). There was little statistical heterogeneity; however, these analyses have limited power. In the time window 3 to 4 months after randomization, the pooled responder rate ratio (main outcome measure) was 1.24 (95% confidence interval 1.05 to 1.46; I2 = 0%; 50% responders in acupuncture groups compared to 41% in the sham groups), and the weighted mean difference in headache days per 4 weeks was 1.92 days (0.72 to 3.15; I2 = 0%). Regarding headache intensity, a significant difference was found only at 5 to 6 months after randomization (Analysis 2.3). Three trials (Karst 2001; Melchart 2005; Tavola 1992) reported data on frequency of analgesic use for the first two time windows (Analysis 2.4). When these trials were pooled, there was a small, significant effect of acupuncture over sham controls (standardized mean differences 0.31 and 0.30, respectively). Headache score data was measured in only two trials (Analysis 2.5).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, outcome: 2.1 Response.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, outcome: 2.2 Number of headache days.

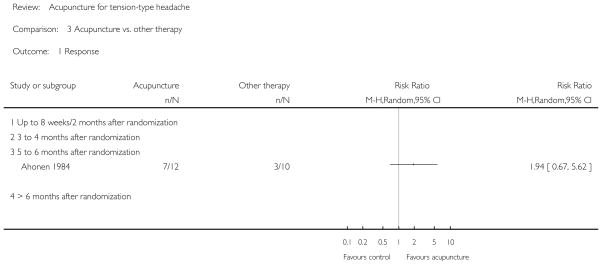

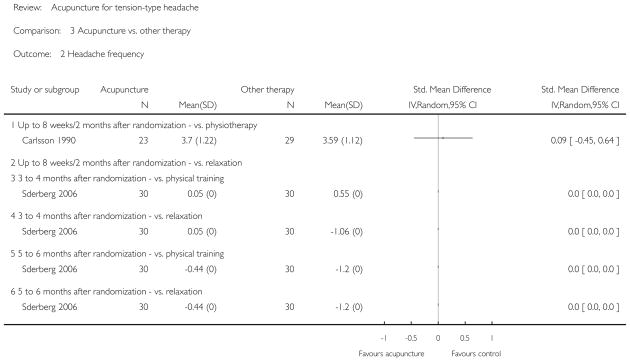

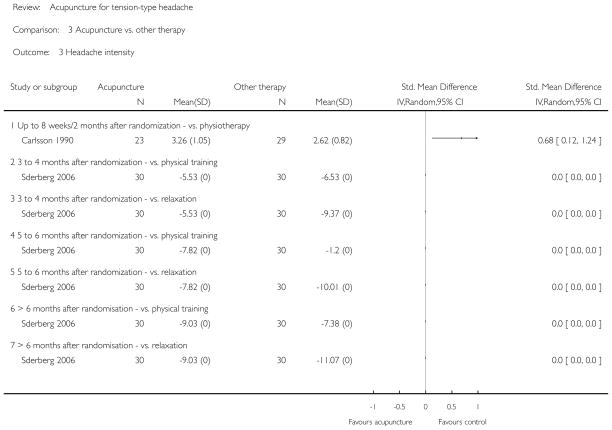

Comparisons with other treatments

The four trials comparing acupuncture with physiotherapy ( Ahonen 1984; Carlsson 1990; Söderberg 2006), relaxation ( Söderberg 2006) or a combination of massage and relaxation ( Wylie 1997) provide only very limited data for effect size estimation (see Analysis 3.1 to Analysis 3.5) and must be interpreted with caution. For the three older trials (Ahonen 1984; Carlsson 1990; Wylie 1997), there are several methodological uncertainties (see the relevant risk of bias assessments), and reporting of results is insufficient. The most recent trial (Söderberg 2006) seems to have better quality, and means (but no standard deviations) were reported for a large number of outcomes measured. Ahonen 1984 reported slightly higher response rates in the acupuncture group, Carlsson 1990 better results in the physiotherapy group, Söderberg 2006 found significantly fewer headache days per 4 weeks in the relaxation group immediately after treatment but no other significant difference, and Wylie 1997 found no significant differences.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

This review identified two unblinded, but otherwise adequately performed, large studies (Jena 2008; Melchart 2005) showing that adding acupuncture to routine care or treatment of acute headaches reduces the frequency of headaches in the short-term (3 months). Long-term effects were not investigated. There are six trials comparing various acupuncture strategies with various sham interventions. Pooled analyses of the trials found a small but significant reduction of headache frequency over sham over a period of 6 months. None of the four trials comparing acupuncture with physiotherapy, massage or exercise found a superiority of acupuncture, and for some outcomes better results were observed with a comparison therapy, but these mostly small and older trials of limited quality are difficult to interpret.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Acupuncture is a therapy which is applied in a variable manner in different countries and settings. For example, in Germany, where the three largest trials included in this review were performed, acupuncture is mainly provided by general practitioners and other physicians. Their approach to acupuncture is based on the theories of traditional Chinese medicine, although the amount of training they receive in traditional Chinese medicine is limited ( Weidenhammer 2007). In the UK, the providers are likely to be non-medical acupuncturists with a comparatively intense traditional training, physiotherapists or medical doctors with a more ‘Western’ approach (Dale 1997). The trials included in this review come from a variety of countries and used a variety of study approaches. However, as with other therapies for tension-type headache (McCrory 2000), the evidence base available is far from complete. Despite its frequency, tension-type headache is much less often investigated than migraine. For the German setting, the two available large studies (Jena 2008; Melchart 2005) clearly show clinically relevant short-term benefits of adding acupuncture to routine care. But it is unclear whether these findings can be extrapolated to other settings. It is also unclear whether patients with episodic and chronic tension-type headache respond in a different manner to acupuncture.

Contrary to our parallel review on migraine (Linde 2009), our meta-analyses in this review yield a small, but statistically significant effect of ‘true’ acupuncture interventions over sham interventions for most outcomes for which at least three trials contributed data. This finding is somewhat surprising to those who are familiar with the literature, as none of the individual trials included reported a ‘positive’ conclusion. The meta-analyses on response, headache days per 4 weeks and intensity are heavily influenced by the large, rigorous trial by Endres 2007. For headache frequency (response and headache days per 4 weeks), this trial found statistically significant benefits over sham acupuncture. Interestingly, for the predefined outcome measure of this trial, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.18). The predefined outcome measure was the proportion of patients with at least 50% reduction at 6 months, but patients with protocol violations were counted as non-responders. For example, patients who changed from one analgesic to another were reclassified as non-responders. Thus, only 33% in the true acupuncture and 27% in the sham group were counted as responders, while the commonly used response criterion without reclassification yielded responder proportions of 66% and 55%, respectively. While such massive reclassification might be worthwhile for certain reasons, it is very uncommon in trials on tension-type headache. Our predefined outcome measure was the ‘usual’ criterion of at least 50% reduction of headache days (IHS 1995). If we had used the ‘reclassified’ responder data from the Endres 2007 study for our meta-analysis, the pooled responder rate ratio for the time window at 6 months would no longer have been significantly different from placebo. As our findings are based on a small number of (albeit comparably well-done) trials, they are not robust and have to be interpreted with caution. In our parallel review on migraine (Linde 2009), we found no clear effects of acupuncture interventions over sham treatment, but relevant effects over routine care and some significant effects over evidence-based prophylactic drug treatment. This finding led us to speculate that, independently from the question whether acupuncture has ‘specific’ effects due to specific points or needling techniques, it may be a particularly potent placebo (Kaptchuk 2000; Kaptchuk 2002; Kaptchuk 2006), and/or sham acupuncture might be associated with direct physiological effects relevant to pain processing (Lund 2006). The differences in the only trial included in this review which had both a sham group and a group receiving only acute treatment (Melchart 2005) are clinically relevant and clearly larger than those in average in comparisons of placebo interventions and no treatment (Hróbjartsson 2004). We did not find any comparisons of acupuncture with prophylactic drug treatment. The trial by Endres 2007 was originally designed to include a third arm of patients randomized to amitriptyline, the currently most widely accepted therapy (Diener 2004). However, as patients were unwilling to participate in a trial with the possibility of being randomized to amitriptyline, this arm was dropped after 1 year of very poor accrual. This suggests that patients ready to accept treatment with acupuncture and amitriptyline differ. Apart from the trial by Söderberg 2006, the trials comparing acupuncture with physiotherapy, relaxation and massage are reported insufficiently or have relevant methodological shortcomings. The question how acupuncture compares to other non-pharmacological treatments cannot be answered at present.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of clinical trials of acupuncture for headache has clearly improved since the previous version of our review. Methods for sequence generation, allocation concealment, handling of dropouts and withdrawals and reporting of findings were adequate in the majority of the recent trials. Still, designing and performing clinical trials of acupuncture is a challenge, particularly with respect to blinding and selection of control interventions. As all relevant headache outcomes have to be assessed by the patients themselves, reporting bias is possible in all trials comparing acupuncture to no treatment, routine, care, drug treatment or other therapies.

Potential biases in the review process

We are confident that we have identified the existing large clinical trials relevant to our question, but we cannot rule out the possibility that there are additional small trials which are unpublished or published in sources not accessible by our search. We have not systematically searched Chinese databases for this version of the review, but Chinese trials meeting our selection criteria might exist. The few Chinese trials identified through our literature search did not meet the inclusion criteria. There is considerable skepticism toward clinical trials from China because results reported in the past were almost exclusively positive (Vickers 1998). However, the quality and number of randomized trials published in Chinese have improved over the last years (Wang 2007), and it seems inadequate to neglect this evidence without examining it critically. For the next update of this review we plan to include researchers and evidence from China to overcome this shortcoming. Three members of the review team were involved in at least one of the included trials. These trials were assessed by other members of the review team. All reviewers are or were affiliated to a CAM (complementary and alternative medicine) research centre.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Just before the submission of this review, another meta-analysis on acupuncture for tension-type headache was published (Davis 2008). This review was restricted to sham-controlled trials, but included cross-over trials with observation periods shorter than 8 weeks per phase, which were excluded by us. The main outcome measure was the number of headache days per month during treatment (broadly comparable to our first time window) and at long-term follow-up (20 to 25 weeks). Eight trials met the inclusion criteria for the review and five provided sufficient data for meta-analysis. Interestingly, although the authors’ meta-analytic calculations for the effect during treatment yielded a larger group difference than ours for the first time window (2.93 days compared to 1.56 days), their findings were statistically not significant, while ours are statistically significant. This is due to the fact that Davis 2008 includes the extremely positive cross-over trial by Xue 2004, excluded by us, which leads to heterogeneity, and uses earlier, slightly more negative data for the White 2000 trial. These factors result in much wider confidence intervals (−7.49 to 1.64 in Davis 2008 compared to −3.02 to −0.10 in our review). Findings for the long-term outcomes are very similar to ours (a small but significant benefit of acupuncture over sham). Davis 2008 concludes that acupuncture has limited efficacy for the reduction of headache frequency compared to sham treatment.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

The available evidence suggests that acupuncture could be considered as a non-pharmacological tool in patients with frequent episodic or chronic tension-type headache.

Implications for research

Further trials are clearly desirable. In principle, randomized trials comparing acupuncture with routine care, sham interventions and other treatments are all needed, but all of them are associated with problems. Trials versus routine care and other treatments cannot be blinded easily and are prone to assessment bias. The cumulative evidence suggests that acupuncture is effective in various chronic pain conditions, but that point selection plays a less important role than acupuncturists have thought, and that a relevant part of the clinical benefit might be due to powerful placebo effects or needling effects not dependent on the selection of traditional points. Therefore, if researchers decide to perform a sham-controlled trial, they should seriously consider including a third group receiving another treatment or no treatment beyond treatment of acute headaches. Furthermore, they should be aware that the way the treatment is delivered might have an important impact on outcomes (Kaptchuk 2008), and that large sample sizes might be needed to identify any small point-specific effects. Trials comparing acupuncture with other non-pharmacological treatments should preferably be large multicenter trials to represent in a valid way the variability of these interventions in routine care.

Acknowledgments

Dieter Melchart, Patricia Fischer and Brian Berman were involved in previous versions of the review. Eva Israel helped assessing eligibility. Lucia Angermayer helped with data checks and quality assessments. Sylvia Bickley performed search updates and Becky Gray helped in various ways. We would like to thank the authors of included studies who provided additional information.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

NIAMS Grant No 5 U24-AR-43346-02, USA.

-

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, USA.

Eric Manheimer’s work was funded by Grant Number R24 AT001293 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM)

-

International Headache Society, Not specified.

For administrative costs associated with editorial review and peer review of the original version of this review.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Blinding: none Dropouts/withdrawals: unclear Observation period: baseline 2 months; treatment unclear, no follow-up Acupuncturists’ assessments: GA differently/60% - BB differently/30% |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 22?/22 Condition: myogenic headache Demographics: mean age 46 years (acupuncture) and 37 (control); 82% female Setting: neurological outpatient department of university hospital in Finland Time since onset of headaches: 5.7 years |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: GB8, GB20, BL10, BL12, BL15, Chuanxi and pressure points on the neck No information on acupuncturist(s) DeChi achieved?: no information Number of treatment sessions: unclear (10 minutes each) Frequency of treatment sessions: no information Control intervention: physiotherapy (parafango, massage, ultrasound) |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: point measurement (no diaries); pain intensity (visual analogue scale) and muscle tension (EMG) were measured; only data for follow-up and only number of patients with global response, response regarding frequency and medication presented | |

| Notes | Insufficient reporting; unclear whether there were dropouts/withdrawals, poor outcome measurement; sample size too small to assess equivalence of the two therapies | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No description |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No description |

| Blinding? All outcomes | No | No |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear | No mentioning of attrition |

| Free of selective reporting? | No | Visual analogue scales have been used but only global responder measures are re-ported |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data ad-dressed? | Unclear | No mentioning of attrition |

| Methods | Blinding: not blinded Dropout/withdrawals: bias possible (8/31 dropouts in acupuncture, 2/31 in physiotherapy group) Observation period: baseline 3–8 weeks; treatment 2–8 weeks; follow-up 7–12 months Acupuncturists’ assessments: GA completely differently/10% - BB completely different/20% |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 62/52 Condition: chronic tension headache (Ad Hoc) Demographics: mean age 34 years; all female Setting: hospital/outpatient department, Sweden Time since onset of headaches: mean 9 years |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: local points: GB 20, GB 21; distal points: LI 4 Information on acupuncturists: n = 2; no further information DeChi achieved?: yes Number of treatment sessions: 4 to 10 sessions of 20 minutes each Frequency of treatment sessions: 1–2/week Control intervention: individualized physiotherapy (10–12 sessions of 30 to 45 minutes each, including relaxation, automassage, TENS, cryotherapy, coping techniques) |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: point measurement (no diary) Outcomes: visual analogue scales, Likert scales for intensity and frequency, Sickness Impact Profile, Mood Adjective Check List |

|

| Notes | Multiple publication; dropouts different between groups; control group got more therapy than acupuncture group Data for effect size estimation re-calculated from data presented in the publication Pain Clinic 1990 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No description |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Information from author: “The randomization was done in blocks of 4. In an envelope there were 4 pieces of paper which were folded two times and signed with A for acupuncture and R for relaxation (two of each). For each patient one piece of paper was drawn ‘blinded’ until all were taken.” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | No blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | Two patients randomized to acupuncture did not enter treatment phase. A further 6 acupuncture and 2 physiotherapy patients dropped out (reasons not related to efficacy). 23 of 31 randomized to acupuncture and 29 of 31 randomized to physiotherapy patients in analysis. Dropouts seem to have been excluded from all analyses. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | No predefined outcome measure, a number of relevant measures presented in figures, others summarized in text; no indication that there was a major selection |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed? | Unclear | See above |

| Methods | Blinding: patients, telephone interviewers; blinding tested and successful Dropouts/withdrawals: only very minor number of patients, bias unlikely Observation period: 4 weeks baseline; 6 weeks treatment; 20 weeks follow-up Acupuncturists’ assessments: GA similarly/40% - BB similarly/75% |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 409/409 Condition: episodic or chronic tension-type headache (IHS) Demographics: median age 38 years (range 29–48 ys); 78% female Setting: 122 primary care practices in Germany Time since onset of headaches: median 7.3 (acupuncture) and 8.7 (sham) years (range 3.1 to 18.3 years) |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: semistandardized - depending on Chinese syndrome diagnosis, predefined collections of obligatory and flexible points Information on acupuncturists: 122 primary care physicians; at least 140 hs of acupuncture training, average experience 8.5 ys (range 2–36 ys) DeChi achieved?: yes Number of treatment sessions: 10 (if moderate response further 5 sessions possible) Frequency of treatment sessions: 2/week Control intervention: sham acupuncture (superficial needling at distant non-acupuncture points) |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: diary and interviews Main outcome measure: at least 50% frequency reduction and no protocol violations Other outcomes: number of headache days per four weeks, at least 50% frequency reduction (regardless of protocol violations), quality of life (SF-12), von Korff chronic pain grading scale, global patient rating |

|

| Notes | Large, rigorous trial with unusual main outcome measure (responders were re-classified to non-responders for various reasons, for example if there were minor changes in acute medication (patients were allowed to use only one of their pre-baseline oral headache analgesics)). The trial initially included a third arm with amitriptyline which had to be close as no one was willing to be randomized to this arm, therefore, this arm was closed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Computer program |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Central telephone randomization procedure |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Patients and telephone interviewers were blinded. Test of blinding suggests successful blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | Low attrition rate and intention-to-treat analyses |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | Primary outcome predefined, good presentation of relevant secondary outcomes |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed? | Yes | Low attrition rate and intention-to-treat analyses |

| Methods | Sequence generation: computer program (information from author) Concealment: central telephone randomization (information from author) Blinding: none Dropouts/withdrawals: 1479 of 1613 included in the acupuncture group with 3 month data vs. 1456 of 1569 in the control group; sensitivity analyses with missing values replaced confirm main analysis based on available data Observation period: no baseline period; treatment 3 months; no follow-up (for randomized comparison) Acupuncturists’ assessments: GA insufficient information for an assessment - BB ? |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 3182/2935 with migraine or TTH (of those included 1265 with TTH, no information on numbers of TTH patients analyzed) Condition: migraine and/or tension-type headache (IHS) Demographics: mean age 44 years, 77% female (for total group) Setting: several thousand practices in Germany Time since onset of headaches: 10.8 years (for total group) |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: individualized selection Information on acupuncturists: multiple physicians with at least 140 hours acupuncture training DeChi achieved?: no information Number of treatment sessions: up to a maximum of 15 Frequency of treatment sessions: individualized Control intervention: waiting list receiving “usual care” |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: questionnaires, no diary Primary outcome: headache days in the third month Other outcomes: intensity, quality of life |

|

| Notes | Large, very pragmatic study including both patients with migraine and tension-type headache reporting some outcomes for headache subgroups; treating physicians were completely free to choose points, number of sessions (upper limit allowed 15) etc. Unclear what usual care consisted of. Some diagnostic misclassification likely. Authors provided raw means, standard deviations and number of observations for headache days and headache intensity. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Computer program |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Central telephone randomization |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | No blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | Low attrition rate and sensitivity analyses with replacing missing values confirming main analyses |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | Limited outcome measurement. Data on relevant outcomes for the subgroup of patients suffering from tension-type headache provided by authors |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed? | Unclear | No randomized comparison after 3 months |

| Methods | Blinding: patients (blinding tested), examiner, statistician Dropouts/withdrawals: 61 (32 vs. 29) of 69 (34 vs. 35) completed treatment, 55 (27 vs. 24) included in the long term follow-up (information from author) Observation period: 4 weeks baseline; 10 weeks treatment; 5 months follow-up Acupuncturists’ assessments: GA differently/25% - BB differently/40% |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 69/61 Condition: episodic (22) or chronic (39) tension-type headache (IHS) Demographics: mean age 48 years, 55% female Setting: academic physical medicine outpatient department, Hannover, Germany Time since onset of headaches: not reported |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: GB20, LI4, LR3 in all patients + selection of points to be chosen individually acc. to symptoms Information on acupuncturists: n = 5 (3 highly experienced, two with limited experience) (information from author) DeChi achieved?: achieved in majority of patients (information from author) Number of treatment sessions: 10 Frequency of treatment sessions: 2/week Control intervention: non-penetrating placebo needle treatment at true acupuncture points |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: diary and questionnaires Outcomes: number of headache days per month, analgesic use, pain intensity, site and duration of headache attacks, overall rating on a visual analogue scale and Clinical Global Impression Index, Nottingham Health Profile, Everyday Life Questionnaire, Freiburg Questionnaire of Coping with Illness, and von Zerssen Depression Scale |

|

| Notes | Sham needles fixed at true acupuncture points; additional information from authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Computer program (information from author) |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Allocation after inclusion of a patient checked in a random number list by independent secretary (information from author) |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Non-penetrating (Streitberger) needle at true points used as sham treatment. Test of blinding suggests successful blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | Incomplete description in the publication but the author provided copies of an unpublished report with relevant information. Analyses were performed based on the available data. Completion of treatment 32/34 (acupuncture) vs. 29/35 (sham), 6 week-follow-up available for 27/34 vs. 30/35. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | No primary outcome reported, but table provides a good summary of the most relevant outcome measures |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed? | Unclear | 5 month follow-up data available for 31/34 vs. 24/35 patients |

| Methods | Blinding: patients, diary evaluators Dropouts/withdrawals: major bias unlikely Observation period: baseline 4 weeks; treatment 8 weeks; follow-up 12 weeks Acupuncturists’ assessments: AW similarly/60% - GA exactly as in the study/95% |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 270/234 Condition: episodic and chronic tension-type headache (IHS) Demographics: mean age 43 years, 74% female Setting: 28 primary care practices in Germany Time since onset of headaches: mean 14.5 years |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: in all patients GB20, GB21 and LIV3, additional optional points recommended according to symptoms Information on acupuncturists: n = 42, at least 160 hs of training DeChi achieved?: yes Number of treatment sessions: 12 Frequency of treatment sessions: 2/week for four weeks, then 1/week for 4 weeks Control intervention 1: minimal acupuncture (superficial needling at non-acupuncture points) Control 2: no acupuncture waiting list group (patients only treated acute headaches with analgesics and received acupuncture 12 weeks after randomization) |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: diary and pain questionnaires Main outcome measure: difference in the number of headache days between baseline and weeks 9 to 12 Other outcomes: headache days, intensity, analgesic use, duration, headache score, global intensity rating, quality of life (SF-36), depressive symptoms (CES-D), emotional aspects of pain (SES), disability (PDI) |

|

| Notes | Additional information for effect size calculation taken from unpublished study report (response, number of headache days, analgesic use and headache score in weeks 5 to 8) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Computer program |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Central telephone randomization |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Patients and diary evaluators were blinded for comparison with sham. Patients were informed that two different types of acupuncture were compared. Early tests of blinding indicate successful blinding, but at follow-up guesses of allocation status were different between groups (P = 0.08). Comparison with no treatment not blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | Low attrition rate and intention-to-treat analyses |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Detailed presentation of main results |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed? | Yes | Low attrition rate and intention-to-treat analyses |

| Methods | Blinding: no blinding Dropouts/withdrawals: no dropouts until treatment completion, 11 patients with missing data at 3 months follow-up and 34 at 6 months could not be analyzed (main reasons lacking headache diaries) Observation period: 4 weeks baseline; 2.5 to 3 months treatment; 7 months follow-up Acupuncturists’ assessments: GA differently/65% - BB differently/50% |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 90/90 Condition: chronic tension-type headache (IHS) Demographics: mean age 37.5 years, 81% female Setting: 3 physiotherapy clinics in Sweden Time since onset of headaches: median duration 7.5 years |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: mandatory GB20, GB14, LI4, ST44, optional PC6, PC7, SP6, BG34, ST8, EX1 and EX2 Information on acupuncturists: 5 experienced physiotherapists DeChi achieved?: yes Number of treatment sessions: 12 Frequency of treatment sessions: 1/week Control intervention 1: physical training (10 sessions at the clinic + 15 home training sessions; exercises focusing on neck and shoulder muscles) Control intervention 2: relaxation (progressive muscle relaxation and autogenic relaxation techniques, breathing, stress coping) |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: diary, pain rating Outcomes: headache intensity, headache-free days, headache-free periods |

|

| Notes | Some additional information received from first author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Sealed opaque envelopes were prepared and mixed in a box. After inclusion of a patient, an envelope was taken from the box. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | See above |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | No blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | Low attrition arte and intention-to-treat analysis |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | Relevant outcomes reported |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed? | Unclear | More than a third of patients were lost to follow-up (dropout rates similar in all three groups and intention-to-treat analysis) |

| Methods | Blinding: patients and data-collecting physician Dropouts/withdrawals: none (all patients completed the follow-up) Observation period: baseline 4 weeks; treatment 8 weeks; follow-up 12 months Acupuncturists’ assessments: GA (probably) exactly the same way/80% - BB exactly the same way/90% |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 30/30 Condition: tension-type headache (Ad Hoc criteria) Demographics: mean age 33 years; 87% female Setting: headache outpatient department of a university hospital in Italy Time since onset of headaches: mean 8 years |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: individualized according to traditional Chinese medicine, possibility of changing points Information on acupuncturist: n = 1 DeChi achieved?: yes Number of treatment sessions: 8 (20 minutes each) Frequency of treatment sessions: 1/week Control intervention: sham (non-acupuncture points in the same regions) |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: diary Outcomes: headache score, duration, frequency, intensity, analgesic use, response |

|

| Notes | Rigorous trial; acupuncture seems to be clearly better in all outcomes, but most differences are not statistically significant; surprisingly negative conclusions Number of headache days at 3 months recalculated from baseline values and percentage reduction. As no standard deviation was available, the pooled baseline standard deviation was used. Data for headache index and analgesic use extrapolated from figures. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No description |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No description |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Patients and physician collecting the diaries were blinded. Description of the procedure suggests adequate blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | Explicit statement that there were no losses to follow-up |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | Relevant outcomes reported in figures or text |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed? | Yes | Explicit statement that there were no losses to follow-up |

| Methods | Blinding: patients and evaluator Dropouts/withdrawals: bias unlikely Observation period: 3 weeks baseline; 6 weeks treatment; 3 weeks follow-up Acupuncturists’ assessments: GA similarly/25% - BB similarly/65% |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 10/9 Condition: tension-type headache (IHS) Demographics: mean age 57 years; 8 women Setting: unclear, UK Time since onset of headaches: 32 and 36 years on average |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: 2 to 6 local points, LI4 Information on acupuncturist: n = 1, GP ‘who recently attended a basic acupuncture course’ DeChi achieved?: probably in most cases Number of treatment sessions: 6 (brief needling) Frequency of treatment sessions: 1/week Control intervention: sham procedure (plastic guide tube and cocktail stick on 4 body regions without known acupuncture points) |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: diary with intensity, duration and medication. Questions on blinding. | |

| Notes | This methodologically rigorous pilot study is uninterpretable due to relevant baseline differences; more pain-free weeks in true acupuncture group; only brief needling | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Computer program |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Central telephone randomization |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Patients blinded (procedure mimicking needle insertion). Credibility testing suggests successful blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | 1 of 5 patients (20%) in the acupuncture group dropped out |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | Relevant outcome reported |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed? | Unclear | No follow-up performed |

| Methods | Blinding: patients (blinding tested), study nurse Dropouts/withdrawals: bias unlikely for early follow up (8 weeks after randomization), but possible for follow-up 3 months after treatment Observation period: 3 weeks baseline; 5 weeks treatment; 3 months follow-up Acupuncturists’ assessments: GA differently/25% - BB differently/45% |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 50/50 Condition: episodic tension-type headache (although during baseline several patients had headaches on more than half of all days) Demographics: mean age 49 years, 76% female Setting: 4 primary care practices and 1 university institute in the UK Time since onset of headaches: mean 20 years |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: obligatory GB20 and LI4 + 4 optional, individualized points Information on acupuncturists: members of the British Medical Acupuncture Society DeChi achieved?: yes Number of treatment sessions: 8 Frequency of treatment sessions: first 6 treatments weekly, then one/month for 2 months Control intervention: sham treatment (tapping a blunted cocktail stick in a guide tube against bony prominences) |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: diary and questionnaires Main outcome measure: number of headache days Other outcomes: intensity, duration, analgesic use, General Health Questionnaire, global assessments |

|

| Notes | Non-traditional acupuncture technique (brief needling without needle retention) For analyses of headache frequency the data reported for headache days per week were multiplied by 4 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Computer program |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Central telephone randomization |

| Blinding? | Yes | Patients and assisting nurses were blinded. |

| All outcomes | Test of blinding suggests successful blinding. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | Low attrition rate and intention-to-treat analysis |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | Relevant outcomes presented |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed? | Unclear | 10 of 25 (acupuncture group) and 6 of 25 (sham group) patients lost to follow-up |

| Methods | Blinding: post-treatment care Dropouts/withdrawals: unclear Observation period: baseline 4 weeks; treatment/follow-up unclear Acupuncturists’ assessments: GA insufficient information for an assessment - BB similarly/70% |

|

| Participants | Number of patients included/analyzed: 67/? Condition: 27 migraine or migraine + tension-type headache, 40 tension-type headache (IHS) Demographics: mean age 38 years; 67% female Setting: headache outpatient department, UK Time since onset of headaches: mean 10 years |

|

| Interventions | Acupuncture points: chosen individually according to traditional Chinese medicine No information on acupuncturist(s) DeChi achieved?: no information Number of treatment sessions: 6 Frequency of treatment sessions: unclear Control intervention: massage and relaxation |

|

| Outcomes | Method for outcome measurement: diary Outcomes: pain index, headache index (psychological variables only at baseline) |

|

| Notes | Insufficiently reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No description |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No description |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | Patients unblinded. Follow-up assessments carried out by blinded clinician. Most outcome measures patient-rated. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | 82 patients agreed to enter study, 67 started treatment and seemed to have completed the study |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Insufficient presentation of results |

| Incomplete follow-up outcome data addressed? | Unclear | No follow-up performed |

DeChi = irradiating sensation said to indicate effective needling

IHS = International Headache Society

TTH = tension-type headache

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Airaksinen 1992 | Intervention: electrical stimulation not necessarily at acupuncture points (myofascial trigger points) |

| Allais 2003 | RCT comparing needling, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and laser therapy at acupuncture points in patients with transformed migraine |

| Annal 1992 | Intervention: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation not at acupuncture points |

| Borglum-Jensen 1979 | Methods: random allocation unlikely |

| Coeytaux 2005 | RCT in patients with chronic daily headache |

| Domzal 1980 | Not controlled trial |

| Dowson 1985 | Patients: migrainous headaches |

| Ebneshahidi 2005 | RCT on laser acupuncture (no needling) in patients with chronic tension-type headache |

| Formisano 1992 | Neurophysiological study |

| Gottschling 2008 | Intervention: Laser acupuncture without skin penetration Patients: both children with migraine and tension-type headache included - no results for tension-type headache patients alone presented |

| Hamp 1999 | Randomized trial of relaxation and acupuncture in children with tension-type headache |

| Hansen 1985 | Cross-over study with less than 8 weeks observation (3 weeks treatment + 3 weeks follow-up) per period in patients with chronic tension-type headache |

| Henry 1986 | Patients: migraine |

| Johansson 1976 | Randomized trial in patients with tension-type headache. No data presented (only stated that acupuncture was significantly superior to sham acupuncture). |

| Johansson 1991 | Patients: condition facial pain |

| Junnilla 1983 | Patients: study included patients with various chronic pain syndromes, including headache; however, headache patients were not presented as a separate subgroup, but only together with all other patients. |

| Karakurum 2001 | RCT comparing dry needling with subcutaneous needle insertion in 30 patients with tension-type headache. Reason for exclusion: only 4 weeks post-randomization observation period. |

| Lavies 1998 | Small randomized trial of laser acupuncture (no skin penetration) vs. sham laser in patients with migraine or tension-type headache |

| Loh 1984 | Patients: both patients with migraine and tension-type headache included. No separate results for patients with tension-type headache presented. |

| Lundeberg 1988 | Report of a series of studies with RCTs on other pain syndromes; only uncontrolled trial in headache patients |

| Melchart 2004 | Intervention: Acupuncture together with other methods of traditional Chinese medicine (herbs, tuina massage, qi gong) |

| Pikoff 1989 | Patients/outcome measures: study on acute headaches |

| Shi 2000 | RCT of acupuncture vs. inactivated laser in patients with “therapy-resistant headache” (exact headache diagnoses not reported). Insufficiently reported. |

| Sold-Darseff 1986 | Methods: probably not randomized, only a subgroup had headache |

| Stone 1997 | Patients: injured patients (secondary headaches) |