G&H Could you describe the manifestation of portal hypertensive gastropathy, particularly as it differs from varices and other conditions related to portal hypertension?

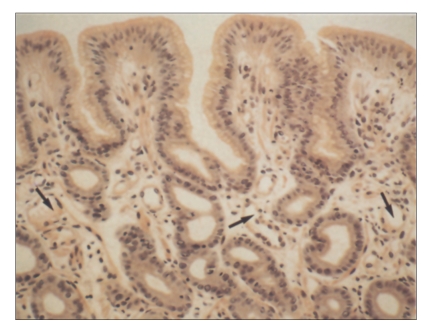

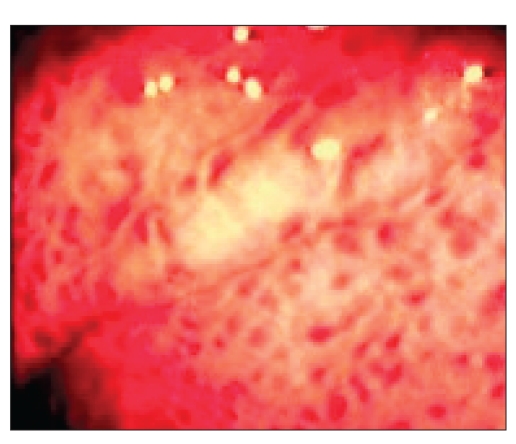

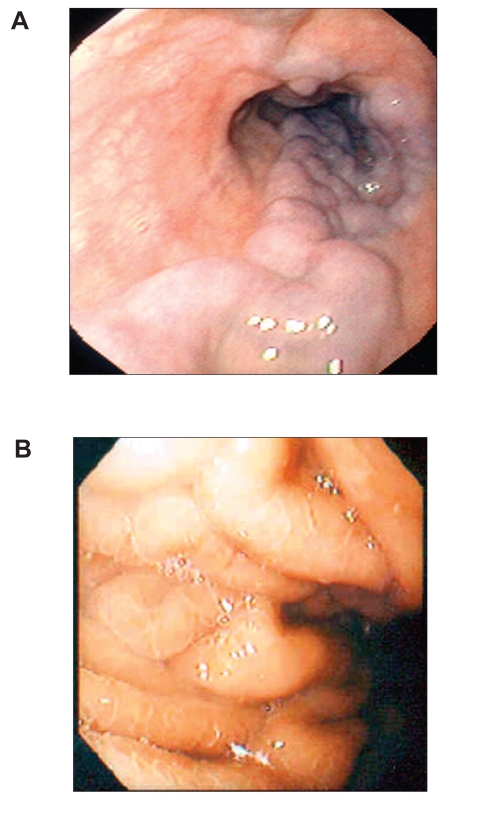

FW Both varices and portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) are manifestations of complications of portal hypertension. Quite often, the two conditions can occur together in the same patient. Varices are distended veins located either along the esophagus (Figure 1A) or in the fundus of the stomach, whereas PHG involves the lining of the stomach (Figure 1B). Varices are collateral vessels, which develop as a result of obstruction to portal flow. They are alternative blood vessels that return the portal blood to the systemic circulation. PHG also develops as a result of increased resistance to portal flow. The gastric mucosa becomes congested with dilated and distended capillaries (Figure 2). Endoscopically, the gastric mucosa looks reddened and edematous with a superimposed mosaic pattern. As the PHG becomes more severe, the mucosa becomes friable and bleeds easily on contact. Frequently, there are hemorrhagic spots on the gastric mucosa (Figure 3). Typically, PHG is most obvious in the proximal stomach. However, mucosal changes similar to those of PHG have also been observed in other parts of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Clinically, varices present with acute onset of upper GI bleed which can be torrential and life-threatening because the veins are distended under high pressure. Patients with PHG also present with upper GI bleeding. When the distended capillaries bleed, they tend to ooze in small amounts. Patients with PHG generally present with chronic anemia. When it is mild, such patients may not seek medical attention. However, when it is severe, patients can potentially be dependent on blood transfusions due to the slow, but constant, blood loss.

G&H Could you describe the pathophysiology of PHG?

FW PHG occurs as a result of portal hypertension, and this can be related to cirrhosis or noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Elevated portal pressure induces changes of local hemodynamics. The gastric mucosa becomes congested as a result of obstruction to portal flow. There is a debate as to whether the total blood flow to the stomach is increased or not, as measurements using Doppler imaging have shown variable results. Irrespective of whether there is an actual increase in gastric blood flow or not, the altered gastric hemodynamics can induce the activation of various cytokines and growth factors, which in turn can mediate some of the changes that are observed in PHG.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is one such cytokine that has been implicated in the pathogenesis of PHG by regulating the production of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator, via induction of the constitutive NO synthase. Overexpression of NO synthase produces an excess of NO, which induces capillary dilatation and peroxynitrite overproduction. Anti-TNF-α neutralizing antibody has been shown to reduce gastric NO synthase activity and normalize gastric blood flow. Increased angiogenesis has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of PHG, and high levels of vascular endothelial growth factor have also been observed in patients with PHG.

There is general agreement that the gastric mucosa in PHG is more susceptible to damage by noxious substances such as bile acids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like aspirin. This may be related to a decrease in the gastric mucosal defense mechanisms, possibly the result of a relative decrease in prostaglandin levels. Other factors that are involved in the increased susceptibility of these patients to gastric damage include the increased peroxynitrite levels from overstimulation of NO synthase. This, in the presence of endothelin overproduction that is commonly observed in cirrhosis, has been associated with increased gastric damage in these patients. Overexpression of transforming growth factor-α has been reported in areas of gastric injury in an animal model of PHG. Reduction in epidermal growth factor (EGF) in the duodenum in patients with cirrhosis has been associated with an increased incidence of duodenal ulcers in these patients. It has been postulated that the same reduction in EGF may also contribute to the development of PHG.

G&H Does the frequency or severity of PHG correspond to the severity of portal hypertension? Why do some patients with portal hypertension develop PHG and others do not?

FW Although the development of PHG is related to the presence of portal hypertension, there is generally no direct correlation between the development of PHG and the level of the portal pressure. In patients who have cirrhosis and PHG, the severity of PHG may increase with more severe liver disease, but there has not been consistent correlation between the severity of the PHG with the severity of the liver disease. It has been suggested that the use of sclerotherapy or banding of varices is associated with an increased incidence of PHG, but this does not appear to be related to changes in the hepatic venous pressure gradient following eradication of varices. We have yet to trace prevalence of any of these conditions to a specific genetic or anatomic abnormality.

G&H What are the treatment options for patients with PHG?

FW Current treatment options are not satisfactory. Two small studies have shown a reduction in gastric blood flow with the use of β-blockers, and propranolol has been shown to reduce the recurrent bleeding rate in another small, uncontrolled trial. A more recent and larger randomized, controlled trial has confirmed the reduction in bleeding rate in patients with PHG taking β-blockers. Somatostatin or its analogue, octreotide, can reduce gastric perfusion in patients with PHG. Likewise, vasopressin and its derivatives such as terlipressin can reduce gastric blood flow, but at the expense of reducing mucosal oxygenation. However, these agents must be administered intravenously, so they are not of practical use in these patients, except for acute bleeding.

Endoscopic treatment of PHG has not been proven to be effective, as the lesions are widespread. Local therapy with endoscopically administered lasers, although effective for gastric antral vascular ectasia, has not been shown to reduce the frequency of bleeding. The safety of this mode of treatment for PHG has also not been confirmed.

In patients who either cannot tolerate or are unresponsive to β-blockers, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPS) can be considered. In a small series of 16 patients, TIPS improved PHG in all patients with severe PHG, but was only partially effective in those with mild PHG. This was achieved by reducing total gastric blood flow, in both the mucosa and the submucosa. Others have also reported similar improvement in endoscopic appearance as well as a reduction in transfusions following TIPS. Because of its complications, TIPS should be reserved as a rescue treatment for patients who are transfusion dependent.

Surgical shunting cannot be recommended, as cirrhotic patients tolerate abdominal operations poorly. Administration of anticoagulants to dissolve a clot in portal vein thrombosis causing portal hypertension is generally not recommended, as this may increase bleeding severity. Further, resection of the affected gastric wall is not recommended, again, because patients with portal hypertension are generally not good candidates for abdominal surgery.

Liver transplantation is the definitive treatment for PHG, as it not only removes the diseased liver but it also eliminates portal hypertension. However, in the era of scarce resources, PHG as the sole indication for liver transplantation is not an option.

In the first instance, I recommend that patients with PHG be given a trial of β-blockers to determine whether this reduces the frequency of blood transfusions. If it does not, then it is worth referring these patients to specialized centers for TIPS placement.

G&H Are any novel treatments currently under investigation for PHG?

FW Recently, rebamipide, a novel anti-ulcer agent, has been shown to be effective in protecting gastric mucosa against NSAID-induced ulceration. In gastric mucosa injury, the upregulation of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 on endothelial cells is followed by neutrophil activation, which is responsible for the injury. Rebamipide, through its antioxidant properties, inhibits the latter step. The fact that rebamipide can prevent the NSAID-induced gastric mucosal injury and reduction of gastric mucosal blood flow in healthy volunteers suggests that it may have a similar effect on patients with PHG.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic views of esophageal varices (A) and portal hypertensive gastropathy (B).

Suggested Reading

- Wong F. The use of TIPS in chronic liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5:5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therapondos G, Wong F. Miscellaneous indications for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1161–1166. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000236876.60354.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman A. Portal hypertension-related bleeding: management of difficult cases. Clin Liver Dis. 2006;10:353–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachogiannakos J, Montalto P, Burroughs AK. Prevention of first upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2000;46:87–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuluvath PJ, Yoo HY. Portal hypertensive gastropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2973–2978. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]