Abstract

A new verotoxin (VT) variant, designated vt2g, was identified from a bovine strain of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli (VTEC) serotype O2:H25. When vt2g was aligned with published sequences of vt2 and vt variants, it exhibited the highest DNA sequence homology with vt2 and vt2c. However, vt2g was not detected by vt2-specific primers and probes, although it was partially neutralized by an antiserum to the VT2A subunit. VT2g was cytotoxic for Vero and HeLa cells and was not activated by mouse intestinal mucus. The vt2g gene was detected in 3 of 409 (0.7%) bovine VTEC strains, including serotypes O2:H25, O2:H45 and Ont:H−.

Verotoxin (VT), also known as Shiga toxin (Stx), is a cytotoxin produced by strains of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli (VTEC), an enteric pathogen associated with bloody diarrhea and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome (3, 17). VTs are divided into two groups. VT1 is highly homologous to Stx of Shigella dysenteriae type I. VT2 shares approximately 55% amino acid homology with VT1 but is relatively more heterogeneous. Apart from sequence variation, variants of VT2 differ from each other in terms of their affinity for glycolipid receptors, Vero cell cytotoxicity, animal pathogenicity, and response to activation by intestinal mucus (9, 11).

The techniques used to detect and quantify VTs include assays for cytotoxicity, enzyme immunoassays, and PCR assays, with the PCR assay the most popular because of its speed and relative simplicity. The increasing number of reported vt variants, however, has led to a need for more PCR primers for their specific detection. Nevertheless, not all vt variants are detectable with the existing primers. We previously reported a VTEC strain, named 7v, of serotype O2:H25 that was isolated from the feces of healthy cattle and was vt positive when examined with the degenerative PCR primers MK1 and MK2 (5). However, the PCR product obtained from this strain did not hybridize with probes specific for vt1, vt2, or vt2e. Moreover, the variant was not detected with primers specific for vt2c (7), although the cytotoxic activity of strain 7v was partially neutralized by an antiserum specific for subunit A of VT2 (6). In this study, we show that the vt gene of strain 7v is a novel variant, which we have designated vt2g.

The VTEC serotype O2:H25 used for sequencing the vt2g gene and the other 423 VTEC strains isolated in Hong Kong (409 bovine, 10 porcine, and 4 human strains) have been described previously (7). A total of 51 human clinical VTEC isolates from Australia were also examined (Table 1). Standard VTEC strains ATCC 43889 (vt2+), ATCC 43890 (vt1+), and S1191 (vt2e+) were used as controls.

TABLE 1.

Serotypes of the VTEC strains used in this study

| Serotypea | No. of strains | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Human clinical VTEC | ||

| O15 | 3 | Australia |

| O26 | 7 | Australia |

| O111 | 14 | Australia |

| O113 | 7 | Australia |

| O157 | 20 | Australia |

| O157 | 3 | Hong Kong |

| OR | 1 | Hong Kong |

| Porcine VTEC | ||

| Ont | 6 | Hong Kong |

| O108 | 1 | Hong Kong |

| O20 | 1 | Hong Kong |

| O91 | 1 | Hong Kong |

| O121 | 1 | Hong Kong |

| Bovine VTEC | ||

| O157 | 8 | Hong Kong |

| Non-O157 | 401 | Hong Kong |

OR, rough; Ont, O nontypable.

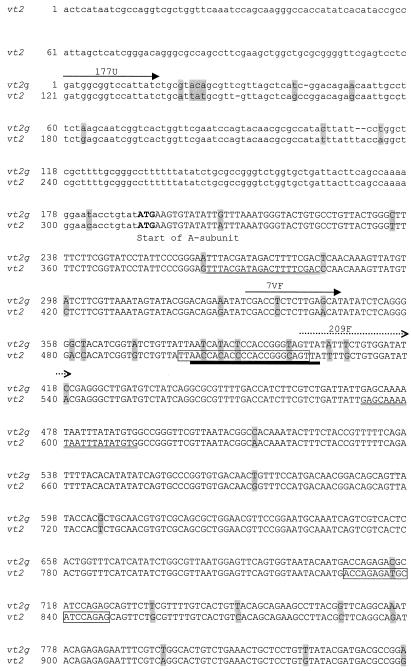

The vt2g gene of strain 7v was amplified by using the primers and protocol described by Paton et al. (12). The sequences of the forward (177U) and reverse (45D) primers were 5′-GAT GGC GGT CCA TTA TC-3′ and 5′-AAC TGA CTG AAT TGT GA-3′, respectively. The 1,493-bp PCR product (Fig. 1) was purified on a QIAquick Mini Column (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, Calif.) and sequenced with the 177U and 45D primers and with the internal oligonucleotide primers 7VF (5′-CGA CCT CTC TTG AGC AT-3′) and 7VR (5′-TCT TCT TCA TGC TTA ACT CC-3′) with an ABI Prism BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit and an ABI 310 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Norwalk, Conn.). Analysis of this sequence (Fig. 1) revealed two open reading frames, the first from nucleotide position 191 to position 1150 (320 amino acids), encoding the putative subunit A, and the second from nucleotide position 1163 to position 1432 (90 amino acids), encoding the putative subunit B.

FIG. 1.

Shaded letters represent nucleotide differences between the sequences of vt2g and vt2. Open reading frames are shown in uppercase letters. Nucleotides in boldface type indicate start or stop codons. Solid arrows indicate the forward, reverse, and internal primers used to sequence vt2g. Dotted arrows indicate the primers for PCR screening of vt2g. The MK1 and MK2 primers are indicated by double underlining. Boxed sequences indicate the PCR primers described by Pollard et al. (13). The solid bar indicates the region recognized by the 428-II oligonucleotide probe.

As the most recently published VT variant was named stx2f (14), we designated the variant reported in this study vt2g. Alignment of the vt2g sequence and comparison of the sequence with those of vt2, vt2c, vt2d, stx2d, vt2e, slt2va, and vt2f (GenBank accession nos. AF461165, M59432, AF043627, AF479829, M21534, M29153, and AJ010730, respectively) were performed with Megalign and EditSeq software (DNAStar, Madison, Wis.). This analysis revealed that the nucleic acid sequence of subunit A of vt2g showed a similarity ranging from 63.0 to 94.9% to the previously reported sequences of vt genes. The vt2g sequence was most closely related to vt2, vt2c, and stx2d, all of which are associated with human disease. Comparison of the sequences of vt2g and vt2 revealed that the most conserved regions occurred from nucleotide position 399 to position 712 (Fig. 1), which encodes the central region of the catalytic subunit. Phylogenetic analysis of the sequences revealed two distinctive clusters: one comprising vt2, vt2c, vt2d, stx2d, vt2e, and vt2g, and the other comprising stx2f and slt2va (2).

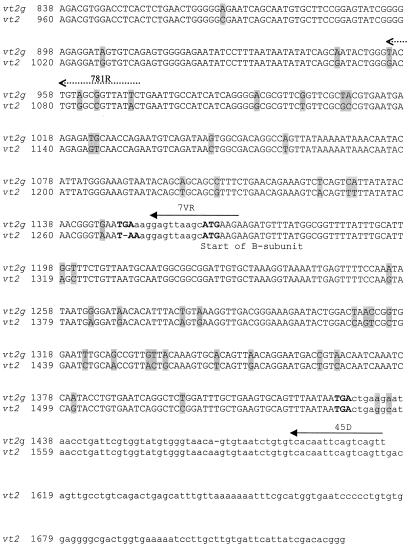

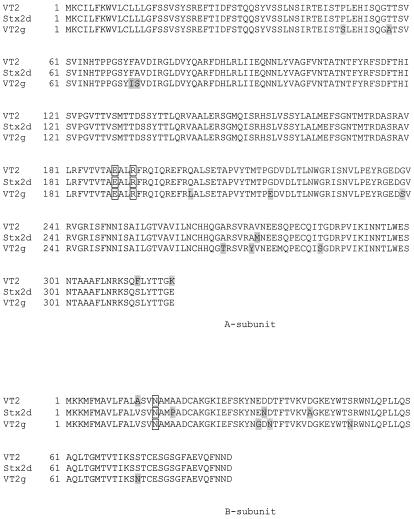

Although there was no sequence variation within the annealing regions for primers MK1 and MK2 (5), there was a 4-bp difference within the region for the vt2-specific oligonucleotide probe, 428-II (4) (Fig. 1). This difference is sufficient to account for the negative hybridization reaction observed previously in the PCR product of strain 7v with the 428-II probe (7). In addition, the vt2g sequence showed a 4-bp difference in the forward priming region and a 1-bp difference in the reverse priming region of the PCR primers published by Pollard et al. (13), which is sufficient to account for the failure of these primers to amplify vt2g. Comparison of the translated sequence of the A subunits of VT2g and VT2 showed 12 (out of 320) amino acid differences between them (Fig. 2), although, importantly, the two amino acid residues E189 and R192 (corresponding to E167 and R170 that are associated with toxin activity in vt1 [1]) were conserved. Protein modeling with a SWISS-MODEL automated protein modeling server and the Swiss-PdbViewer (15) predicted that the three-dimensional structures of the A subunits of VT2g and VT2 would be similar. This similarity is sufficient to explain the cross-neutralization of these toxins by an antiserum prepared against subunit A1 of VT2 (6).

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequence alignments of subunits A and B of VT2, Stx2d, and VT2g. Shaded letters indicate the differences between the two sequences. The boxed letters in subunit A indicate the amino acid residues E189 and R192 associated with toxin activity. The boxed letters in subunit B indicate the asparagine at position 16.

The C terminus of subunit A2 of VT2g included a region (amino acid positions 310 to 319) that is identical to that of Stx2d (GenBank accession number AF479829) (16). Because activation of Stx2d by intestinal mucus is reported to be mediated by elastase cleavage of the last two amino acid residues in the C terminus of subunit A2 (10), we investigated the effect of intestinal mucus on the activity of vt2g. For these studies, intestinal mucus was isolated from BALB/c mice as described by Melton-Celsa et al. (10). The isolated mucus was weighed and added to Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at a final concentration of 2 mg/ml. A diluted overnight culture of VTEC strain 7v was then inoculated into mucus-supplemented LB or plain LB broth at a final concentration of 102 CFU/ml. The broth was incubated at 37°C for 20 h with shaking. After incubation, a 1-ml aliquot was removed and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was then examined for cytotoxicity for Vero cells as described below (7). Our results showed that the cytotoxicity of strain 7v was not influenced by growing strain 7v in the presence of mouse intestinal mucus. This finding can be explained by the fact that subunit B is also involved in mucus-induced toxin activation of Stx2d (10) and that there were seven amino acid differences between the B subunits of VT2g and Stx2d (Fig. 2).

Comparison of the nucleotide sequence of subunit B of VT2g with that of other vt genes revealed homologies ranging from 76.7 to 90.7% and indicated that subunit B of VT2g is most similar to that of VT2. The amino acid similarity between the two B subunits ranged from 80 to 93%. Importantly, the asparagine at amino acid position 16 that is responsible for the high levels of in vitro cytotoxicity of VT2 is conserved in VT2g (8) (Fig. 2). As was the case with subunit A, we observed two phylogenetic clusters of subunit B, with vt2g clustering with vt2, vt2c, and vt2d. The homology between vt2g and vt2 is such that their amplification with primers GK3 and GK4, described by Schmidt et al. (14), yields amplicons of a similar size. These PCR products could be discerned, however, by digestion with FokI, which generates 131- and 155-bp fragments from vt2 but not from vt2g.

Assays for the cytotoxic activity of VT and VT2g were performed as described previously (7). Briefly, for each test or standard VTEC strain, five colonies were picked from LB agar and cultured in LB broth for 18 h. One milliliter of broth culture was then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. A twofold-dilution series of the supernatant was prepared, after which 50 μl of each dilution was mixed with 100 μl of Eagle's minimal essential medium and added to monolayers of Vero and HeLa cells in 96-well microtiter plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C overnight, after which cells were examined for cytopathic effect. The highest dilution producing a cytopathic effect that was ≥50% of the monolayer was considered to be the median cytotoxic dose. The findings indicated that the median cytotoxic doses of culture supernatants from VTEC strains 7v (vt2g+) and ATCC 43889 (vt2+) for both Vero and HeLa cells were the same, namely, 1024 and 512, respectively.

In order to investigate the prevalence of vt2g in VTEC isolates from animals and humans, the forward primer 209F, 5′-GTT ATA TTT CTG TGG ATA TC-3′ (nucleotide positions 399 to 418), and the reverse primer 781R, 5′-GAA TAA CCG CTA CAG TA-3′ (nucleotide positions 955 to 971) (Fig. 1), that are specific for two variable regions of vt2g were designed to amplify a 573-bp product from strain 7v but not from any of the other VTEC or control strains. A total of 474 VTEC isolates that were PCR positive with primers MK1 and MK2 were screened for the presence of vt2g. To detect the vt2g gene in VTEC isolates, bacterial DNA was extracted and prepared as described previously (7). The 25-μl PCR mixture consisted of 3 μl of DNA extract, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 160 μM dNTP, 400 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml, 20 pmol of primers 209F and 781R, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems Inc., Norwalk, Conn.). The reaction mixture was heated at 94°C for 5 min and then subjected to 30 cycles of amplification, each consisting of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 46°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by a final extension period of 7 min at 72°C. Amplified products were visualized by ethidium bromide staining after electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels.

Besides strain 7v, only 2 of the 409 bovine VTEC strains tested were found to harbor vt2g. None of the human or porcine VTEC strains examined was positive in the PCR assay for vt2g. Of the two vt2g-positive strains, one was serotype O2:H45 with a vt1,2 genotype; the other was Ont:H− with a vt2 genotype. Both strains were eae negative, as was strain 7v. The vt2g sequence of the other two bovine VTEC isolates was determined (results not shown) and was found to be identical to that of strain 7v. Although two of the vt2g+ strains belonged to the O2 serogroup, they were clonally diverse as shown by their different H antigens. In addition, all three vt2g+ strains were isolated from cattle feces during separate abattoir visits, and the cattle were imported from different provinces in mainland China.

In summary, we have identified a new vt variant which we have named vt2g. This variant occurred at a rate of 0.7% (3 of 409) in bovine VTEC strains but was not detected in any of 10 porcine or 51 human VTEC strains studied. The low prevalence of vt2g suggests that it may be a newly emerged variant that has not yet extensively spread among cattle. Findings of the present study add further information to the global epidemiological picture of VTEC strains. Our findings showed that vt2g has high nucleic acid homology with vt sequences associated with human diseases. Moreover, VT2g shows conservation of the active sites for verocytotoxicity and cytotoxicity for HeLa and Vero cells that is comparable to that of VT2. For these reasons, the pathogenic potential of VT2g cannot be neglected. Importantly, this vt variant is not detected by vt2-specific primers, which are the major primers used for routine VTEC screening. Our finding that vt2g was detected by broad-spectrum PCR primers and cross-neutralizing antibody to VT2A but not by specific vt primers indicates the need to use a range of different diagnostic tools to screen bacteria for the presence of VT.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The vt2g sequence of VTEC strain 7v has been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession number AY286000.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (HKU 7314/97 M) and a School of Professional and Continuing Education research grant award (21386308.03982.70300.420.01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Cao, C., H. Kurazono, S. Yamasaki, K. Kashiwagi, K. Igarashi, and Y. Takeda. 1994. Construction of mutant genes for a non-toxic verotoxin 2 variant (VT2vp1) of Escherichia coli and characterization of purified mutant toxins. Microbiol. Immunol. 38:441-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gannon, V. P., C. Teerling, S. A. Masri, and C. L. Gyles. 1990. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of another variant of the Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin II family. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:1125-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karch, H., and M. Bielaszewska. 2001. Sorbitol-fermenting Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H− strains: epidemiology, phenotypic and molecular characteristics, and microbiological diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2043-2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karch, H., and T. Meyer. 1989. Evaluation of oligonucleotide probes for identification of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:1180-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karch, H., and T. Meyer. 1989. Single primer pair for amplifying segments of distinct Shiga-like toxin genes by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2751-2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung, P. H., J. S. Peiris, W. W. Ng, and W. C. Yam. 2002. Polyclonal antibodies to glutathione S-transferase—verotoxin subunit A fusion proteins neutralize verotoxins. Clin. Diag. Lab. Immunol. 9:687-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung, P. H., W. C. Yam, W. W. Ng, and J. S. Peiris. 2001. The prevalence and characterization of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle and pigs in an abattoir in Hong Kong. Epidemiol. Infect. 126:173-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindgren, S. W., J. E. Samuel, C. K. Schmitt, and A. D. O'Brien. 1994. The specific activities of Shiga-like toxin type II (SLT-II) and SLT-II-related toxins of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli differ when measured by Vero cell cytotoxicity but not by mouse lethality. Infect. Immun. 62:623-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mainil, J. 1999. Shiga/verocytotoxins and Shiga/verotoxigenic Escherichia coli in animals. Vet. Res. 30:235-257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melton-Celsa, A. R., J. F. Kokai-Kun, and A. D. O'Brien. 2002. Activation of Shiga toxin type 2d (Stx2d) by elastase involves cleavage of the C-terminal two amino acids of the A2 peptide in the context of the appropriate B pentamer. Mol. Microbiol. 43:207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melton-Celsa, A. R., and A. D. O'Brien. 1998. Structure, biology, and relative toxicity of Shiga toxin family members for cells and animals, p. 121-128. In J. B. Kaper and A. D. O'Brien (ed.), Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. American Society for Microbiology, Washington D.C.

- 12.Paton, A. W., J. C. Paton, and P. A. Manning. 1993. Polymerase chain reaction amplification, cloning and sequencing of variant Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin type II operons. Microb. Pathog. 15:77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollard, D. R., W. M. Johnson, H. Lior, S. D. Tyler, and K. R. Rozee. 1990. Rapid and specific detection of verotoxin genes in Escherichia coli by the polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:540-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt, H., J. Scheef, S. Morabito, A. Caprioli, L. H. Wieler, and H. Karch. 2000. A new Shiga toxin 2 variant (Stx2f) from Escherichia coli isolated from pigeons. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1205-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwede, T., A. Diemand, N. Guex, and M. C. Peitsch. 2000. Protein structure computing in the genomic era. Res. Microbiol. 151:107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teel, L. D., A. R. Melton-Celsa, C. K. Schmitt, and A. D. O'Brien. 2002. One of two copies of the gene for the activatable Shiga toxin type 2d in Escherichia coli O91:H21 strain B2F1 is associated with an inducible bacteriophage. Infect. Immun. 70:4282-4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong, S. S. Y., W. C. Yam, P. H. M. Leung, P. C. Y. Woo, and K. Y. Yuen. 1998. Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infection: the Hong Kong experience. J. Gastroen. Hepatol. 13(Suppl.):S289-S293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]