Abstract

Study Objectives:

Predictability and controllability are important factors in the persisting effects of stress. We trained mice with signaled, escapable shock (SES) and with signaled, inescapable shock (SIS) to determine whether shock predictability can be a significant factor in the effects of stress on sleep.

Design:

Male BALB/cJ mice were implanted with transmitters for recording EEG, activity, and temperature via telemetry. After recovery from surgery, baseline sleep recordings were obtained for 2 days. The mice were then randomly assigned to SES (n = 9) and yoked SIS (n = 9) conditions. The mice were presented cues (90 dB, 2 kHz tones) that started 5.0 sec prior to and co-terminated with footshocks (0.5 mA; 5.0 sec maximum duration). SES mice always received shock but could terminate it by moving to the non-occupied chamber in a shuttlebox. SIS mice received identical tones and shocks, but could not alter shock duration. Twenty cue-shock pairings (1.0-min interstimulus intervals) were presented on 2 days (ST1 and ST2). Seven days after ST2, SES and SIS mice, in their home cages, were presented with cues identical to those presented during ST1 and ST2.

Setting:

NA.

Patients or Participants:

NA.

Interventions:

NA.

Measurements and Results:

On each training and test day, EEG, activity and temperature were recorded for 20 hours. Freezing was scored in response to the cue alone. Compared to SIS mice, SES mice showed significantly increased REM after ST1 and ST2. Compared to SES mice, SIS mice showed significantly increased NREM after ST1 and ST2. Both groups showed reduced REM in response to cue presentation alone. Both groups showed similar stress-induced increases in temperature and freezing in response to the cue alone.

Conclusions:

These findings indicate that predictability (modeled by signaled shock) can play a significant role in the effects of stress on sleep.

Citation:

Yang L; Wellman LL; Ambrozewicz MA; Sanford LD. Effects of stressor predictability and controllability on sleep, temperature, and fear behavior in mice. SLEEP 2011;34(6):759-771.

Keywords: Stress, stressor predictability, stressor controllability, tone-shock, rapid eye movement sleep (REM), sleep, mice

INTRODUCTION

There are significant interactions between stressor characteristics, stress-related learning and post-stress sleep in determining the capacity for stressful and traumatic events to produce persisting changes in behavior and health. Stressor controllability,1,2 predictability,2–4 and intensity5,6 play important roles in the effects of stress,2,6 and stress-related conditioning processes, as exemplified by classical fear conditioning, are thought to play significant roles in the development of anxiety disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).7,8 Stress also impacts sleep, and traumatic life events virtually always produce at least temporary sleep disturbances that may include insomnia or subjective sleep problems.9 The persistence of sleep disturbances after a traumatic event may be predictive of the future development of emotional and physical disorders.9,10 Sleep disturbances are also core features of a number of emotional disorders, including anxiety and PTSD.11

Conditioned fear training typically is conducted with a fear-inducing stressor (usually inescapable footshock) being presented in an experimental paradigm in which the animal has no control over the stressor.12,13 Through training, initially neutral environmental cues and contexts become associated with the footshock and acquire the capacity to elicit behavioral and physiological responses indicative of fear and anxiety including behavioral freezing,14,15 autonomic responses,16,17 and fear-potentiated startle.12,13 We and others have demonstrated that training with inescapable footshock18–24 and the presentation of fearful cues19,20,22 and contexts21,25 associated with inescapable footshock also produce significant alterations in post-stress sleep including prominent reductions in rapid eye movement sleep (REM).

We recently extended our studies of the effects of fear conditioning on sleep in mice to include comparisons of the effects of inescapable and escapable footshock in a shuttlebox, as a model of uncontrollable and controllable stress.26 We found increased REM after controllable stress and decreased REM after uncontrollable stress. We also found that re-exposure to the training context without presentation of shock produced increases and decreases in REM similar to those seen during shock training. By comparison, freezing, a common behavioral index of fear14,15 was similar in mice trained with escapable and inescapable shock, even though there were directionally different changes in REM.

Predictability is also an important factor in the effects of stress. For example, animals given the opportunity to determine whether shocks delivered to them will be signaled or unsignaled, typically choose to spend their time in the signaled conditions regardless of whether the shock is escapable or inescapable.27 This suggests that predictability can modulate responses to both controllable and uncontrollable stress. In the present study, we modified our shuttlebox paradigm to examine the effects of predictable controllable and uncontrollable stress on sleep and behavior. We trained yoked pairs of BALB/cJ (C) mice with signaled, escapable shock (SES) and signaled, inescapable shock (SIS) to determine whether shock predictability can be a significant factor in the effects of stress on sleep. We also examined the effects of the signals alone on sleep and we compared mice in the SES and SIS conditions on gross motor activity, freezing, and for potential differences in stress-induced hyperthermia.28,29

METHODS

Subjects

The subjects were 18 male C mice weighing 20 to 25 g, at ages 9 to 10 weeks at the time of surgery. All animals were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine. The animals were individually housed after arrival and food and water were available ad libitum. The recording room was kept on a 12:12 light-dark cycle with lights on from 07:00 to 19:00. Ambient temperature was maintained at 24.5°C ± 0.5°.

Surgery

All mice were implanted intraperitoneally with telemetry transmitters (DataSciences ETA10-F20) for recording EEG, body temperature and activity as previously described.30 EEG leads from the transmitter body were led subcutaneously to the head, and the free ends were placed into holes drilled in the dorsal skull to allow recording cortical EEG. All surgery was conducted with the mice under isoflurane (as inhalant: 5% induction; 1%-2% maintenance) anesthesia. Ibuprofen (30 mg/kg, oral) was continuously available in each animal's drinking water for 24 to 48 h preoperatively, and for a minimum of 72 h postoperatively, to alleviate potential postoperative pain. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals and were approved by Eastern Virginia Medical School's Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol # 08 - 007).

Training Procedures

The mice were housed and studied in the same room. Cages and bedding were changed 2 days prior to recording onset for each phase of the experiment and then not disturbed until that phase was complete.

After a post-surgery recovery period of 21 days, uninterrupted baseline sleep recordings were obtained for 2 days. The mice were then randomly assigned to the SES or SIS groups. Shock training was conducted in a shuttlebox (Coulbourn Instruments, Model E10-15SC) located outside the recording room. The mice were presented auditory tone signals (Cues: 90 dB, 2 kHz) that started 5.0 sec prior to and co-terminated with footshock (0.5 mA; 5.0 sec maximum). Movement prior to footshock onset did not prevent shock presentation. After footshock onset, mice in the SES group were able to learn to escape by moving to the unoccupied chamber in a shuttlebox. Automated detection (via interruption of photobeams) that the SES mouse had entered the previously unoccupied chamber terminated shock for the SES mice and also terminated shock delivery to the yoked-control SIS mice that were in a separate shuttlebox. Thus, both groups received identical amounts of footshock, but the SIS mice could not alter shock duration. If the SES mice failed to escape, the computer program terminated the shock automatically after 5.0 sec.

Coulbourn Graphic State software (version 2.1) running on a personal computer was used to control the administration and timing of the cues and footshock and to ensure that mice in the SES and SIS conditions received the same duration of footshock. Footshock was produced via Coulbourn Precision Regulated Animal Shockers (Model E13-14) and administered via grid floors in the shuttleboxes. The auditory tones were produced with a frequency generator (Coulbourn model S81-06), amplified with a Harmon-Kardon amplifier (model PM655 Vx1) and routed to a speaker (Coulbourn model E12-01 M). For shock training, the speaker was placed near the shuttleboxes; for Cue testing, it was placed near the home cages.

Training took place at the same time on 2 consecutive shock training days (ST1, ST2). The mice were allowed to freely explore the shuttlebox for 5 min, after which they were presented with 20 tone-shock pairings at 1.0-min intervals. Five min after the last tone-shock pairing, the mice were returned to their home cages. The entire procedure was of approximately 30-min duration (there was some variation depending on how fast the SES mice escaped the shock) and occurred during the fourth hour of the lights-on period. Between each training session, the floor trays in the shock chambers were removed and cleaned with 70% alcohol. The shock grid, walls, and doors of the shock chambers were also cleaned with 70% alcohol and then dried with a paper tower if necessary.

After ST1, the animals were left undisturbed in their home cages until the session on the following day. After ST2, the animals were left undisturbed other than a weekly cage change until the Cue test day. For testing the effects of the Cue alone, the mice were transported in their home cages to the test area. Still in their home cages, they were presented with tones identical to those presented during ST1 and ST2. This tone-cue test session occurred 7 days after ST2 at the same time and duration (30 min) as the shock training sessions.

Determination of Escape Latency and Freezing

The Coulbourn Graphic State software used to control cue and shock presentation recorded the time at shock onset as well as the time of shock termination. Subtracting these 2 values provided the escape latency and an approximation of the duration of shock the mice experienced on each shock trial as these varied with the response and reaction time of the mice in the SES condition. These values were summed for all 20 shock trials on ST1 and ST2 to obtain an estimate of the amount of shock the animals received.

The shock training and the Cue presentation sessions were videotaped for subsequent scoring of freezing, defined as a rigid posture with the complete absence of visible movement except for respiration. Freezing was scored by a trained observer in 5-sec intervals over the course of the first 5 min the mice were in the shock chambers on ST1 and for the entire 30 min of the Cue presentation day. The percentage time spent in freezing was calculated (FT%: freezing time/observed time × 100) for each animal for each observation period. The analysis of FT% contains data from 7 pairs of mice. One session of recordings respectively from 2 pairs of mice was not taped properly.

Data Recording and Determination of Behavioral State

EEG, body temperature, and activity data were collected for 20 h on ST1, ST2 and the Cue test day. For recording, individual cages were placed on a DataSciences telemetry receiver (RPC −1), and the transmitters for the mice were activated with a magnetic switch. When the animals were not on study, the transmitters were inactivated. Signals (EEG, body temperature, and activity) from the transmitter were detected by a receiver located directly underneath the cage. These signals were processed by DataSciences software and saved to the hard disk for subsequent offline data analyses and for visual scoring of sleep and wakefulness in 10-s epochs using the SleepSign scoring program.

Epochs were scored by a trained observer as either active wakefulness (AW, activity recorded in epoch), quiet wakefulness (QW, no activity in epoch), NREM, or REM based on EEG and gross whole body activity as previously described.30 Transistor-transistor logic (TTL) pulses generated by the telemetry system when the mice moved around in their cages were counted as a measure of activity. This method provides only a measure of general activity and typically requires gross body movement in order to generate a count. The core body temperature was automatically recorded by the intraperitoneally implanted transmitter.

Data Analyses

The following sleep parameters were evaluated: total REM sleep, number of REM episodes, REM sleep episode duration, REM sleep percentage ([total REM / total sleep] * 100), total NREM sleep, and total sleep time (TST). We also examined latency to NREM and latency to REM from the onset of recording. Parameters examined for wakefulness were amounts of active wakefulness (AW) and total activity. The data for sleep and wakefulness were analyzed for the total 20-h recording period and in 4-h blocks across the recording period. The analyses of 4-h blocks were conducted on 2 blocks in the light period and 3 blocks in the dark period. The data were analyzed with Group (SES and SIS) × Treatment (Baseline, ST1, ST2, and Cue) or Group (SES and SIS) × Block (Block 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) mixed-factor analyses of variance (ANOVAs) procedures with repeated measures on Treatment and Block.

The data for the body temperature were analyzed hourly for the initial 4 h and in 10-min blocks for the first 2 h of the total 20-h recording period using mixed-factors ANOVAs with repeated measures on treatment and time. The escape latency and freezing data were analyzed using t-tests or repeated-measures ANOVAs.

Data were analyzed using SigmaStat V2.03 (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL). When indicated by significant ANOVAs, post hoc comparisons among means were conducted with Tukey tests.

RESULTS

Escape Latencies and Shock Duration

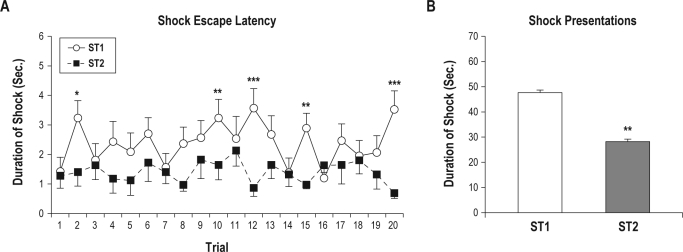

The average escape latency across trials during ST1 (2.38 ± 0.85 s) was significantly longer than during ST2 (1.41 ± 0.62 s), t8 = 3.74, P < 0.006. The average escape latency across trials during ST1 showed greater fluctuation (1.2-3.57 s) than during ST2 (0.69-2.13 s). Escape latencies on trials 2, 10, 12, 15, and 20 were significantly longer on ST1 than on ST2 (Figure 1A), but no other comparisons with trials were significant. Two mice showed poorer escape learning, as indicated by longer escape latencies on 6 and 9 of the 20 trials on ST2 compared to ST1. However, the average escape latencies showed that total shock received was greater on ST1 than on ST2 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Average shock escape latency and total shock duration received by pairs of mice in the signaled escapable shock (SES) and yoked signaled, inescapable shock (SIS) conditions on shock training days 1 and 2 (ST1, ST2). (A) Average shock escape latency across 20 individual shock trials. Differences between ST1 and ST2: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (Tukey tests). (B) Total shock duration. Differences between ST1 and ST2: **P < 0.006 (t-test). Error bars are ± SEM.

Freezing in Response to Fear-conditioned Auditory Cue

The SES mice and SIS mice showed minimal freezing in the 5-min pre-shock period of ST1. Two-way mixed-factor ANOVA (Group × Period) revealed a significant main effect for Period (F1,12 = 17.62, P < 0.002) in comparisons of FT% in the 5-min pre-shock period to that in the entire 30-min period on the Cue test day. There was no significant difference between the SES and SIS mice (not shown).

Comparisons of freezing also were made between the 5-min pre-shock period and the 30-min tone cue period divided into six 5-min blocks (Figure 2). There was a significant main effect for blocks (F6,72 = 9.76, P < 0.001). Compared to pre-shock period, the SES mice showed a significantly increased freezing in blocks 3-5 of the Cue presentation period, while the SIS mice showed significantly increased freezing in blocks 2-5 of the Cue presentation period. The SES and SIS mice did not show significantly increased freezing in blocks 1 and 6, during which no tones were presented. There also was no significant difference in FT% between the SES and SIS mice during any 5-min block on the Cue test day.

Figure 2.

Percent time freezing (%Freezing) plotted for the 5-min pre-shock period (PS) when the mice were naïve and for the 30 min cue test period divided into six 5-min blocks (B1-B6). No cues were presented in B1 and B6. Cues identical to those experienced by the pairs of mice in the signaled escapable shock (SES) and yoked control signaled inescapable shock (SIS) conditions were presented in B2-B5. Significant differences are indicated for comparisons between the 5-min pre-shock period (PS) of ST1 and B1-B6: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Tukey test). Error bars are ± SEM.

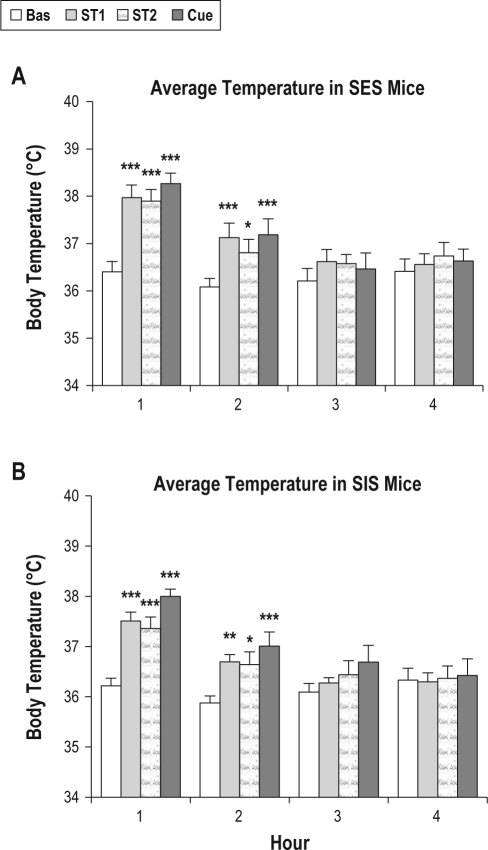

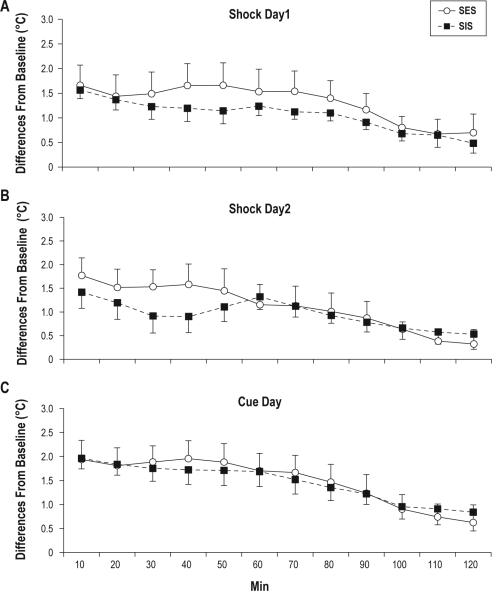

Core Body Temperature

Figure 3 presents core body temperature plotted hourly for the first 4 h after training on ST1, ST2 and on the Cue test day. The main effect for treatment was significant for hour 1 (F3,48 = 43.74, P < 0.001) and hour 2 (F3,48 = 16.48, P < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons revealed that core body temperature was increased in both SES and SIS mice in the initial 2 h after ST1, ST2 and Cue alone compared to time matched baseline. Core body temperature did not significantly differ in comparisons of ST1, ST2, or the Cue test day.

Figure 3.

Average body temperature plotted hourly for 4 h during baseline (Bas), shock training days 1 and 2 (ST1, ST2), and cue alone (Cue) in mice receiving signaled, escapable (A) and yoked signaled, inescapable shock (B). Significant differences for SES and SIS mice are shown for comparisons to time-matched baseline recordings: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (Tukey tests). Error bars are ± SEM.

The analysis of temperature in hourly blocks did not reveal significant differences for the SES and SIS mice during any period. Therefore, we also conducted a comparison of SES and SIS mice in 10-min intervals over the first 2 h of recording. This comparison is plotted in Figure 4 as differences from baseline temperature for ST1, ST2, and the Cue test day. This analysis found no significant differences between groups in the time course of temperature changes on either day.

Figure 4.

Time course of changes in core temperature plotted as differences from baseline for mice in the signaled escapable shock (SES) and yoked control signaled inescapable shock (SIS) conditions. Plots show temperature in 10-min intervals across the first 2 h of recording. (A) Shock training day 1. (B) Shock training day 2. (C) Cue test day. There were no differences between groups on either day. Error bars are ± SEM.

Effects of SES and SIS on REM

The 20 h baseline recordings of the SES and SIS mice did not differ for any sleep parameter we examined. In general, compared to baseline recordings, SES resulted in significant post-stress increases, and SIS resulted in post-stress decreases in most of the REM parameters that we examined (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

REM parameters plotted as 20-h totals for baseline (Bas), shock training days 1 and 2 (ST1, ST2), and cue test day alone (Cue). (A) Total REM. (B) REM percentage ([total REM time/total sleep time]*100). (C) Number of REM episodes. (D) REM episode duration. Significant differences between SES and SIS mice: **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Significant differences in SES mice compared to Bas: +P < 0.05; ++P < 0.01; +++P < 0.001. Significant differences in SIS mice compared to Bas: ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001 (Tukey tests). Error bars are ± SEM.

The analysis of total REM over the 20-h recording period (Figure 5 A) revealed a significant main effect for group (F1,16 = 8.35, P < 0.02) and a significant group × treatment interaction (F3,48 = 16.52, P < 0.001). Compared to SIS mice, SES mice exhibited more REM on ST1 and ST2. Compared to baseline, SES mice exhibited greater REM on ST1 and ST2, whereas SIS mice exhibited less REM on ST1.

The analyses for REM percentage (Figure 5 B) was similar with a significant main effect for group (F1,16 = 16.01, P < 0.001) and a significant group × treatment interaction (F3,48 = 20.77, P < 0.001). The results for the post hoc comparisons were also similar except that REM percentage was elevated on the Cue day compared to baseline.

The analysis for the number of REM episodes (Figure 5 C) found a significant group × treatment interaction (F3,48 = 10.18, P < 0.001). Compared to SIS mice, SES mice exhibited more REM episodes on ST1. Compared to baseline, SES mice exhibited more REM episodes on ST1 and ST2 whereas SIS mice exhibited fewer REM episodes on ST1. There were no differences in REM episode duration (Figure 5 D).

We also compared REM parameters in 4-h blocks to determine if there were differences in the time course of changes across groups (Table 1). In general, SES mice showed more REM than did SIS mice. Significant differences between SES and SIS mice were found in Blocks 2, 4, and 5 for total REM; in Blocks 2, 3, 4, and 5 for REM percentage; and in Block 2 for the number of REM episodes. A significant treatment effect was also found in Block 1 in the analysis of the number of REM episodes.

Table 1.

REM parameters (mean and SEM) in 4-h blocks across the 20-h recording period for baseline (Bas), shock training day 1 (ST1), shock training day 2 (ST2), and the tone-cue day (Cue) in mice trained with signaled escapable shock (SES) and yoked control mice trained with signaled inescapable shock (SIS).

| Total REM | Group | Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | Block 4 | Block 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | SES | 8.22 (1.02) | 5.18 (1.65) | 4.98 (1.89) | 9.15 (2.07) | 13.72 (1.87) |

| SIS | 8.78 (1.51) | 7.59 (1.37) | 4.00 (1.41) | 9.89 (1.79) | 14.72 (1.52) | |

| ST1 | SES | 8.06 (2.46) | 11.96 (1.23)+ | 8.67 (2.24) | 13.13 (1.2) | 17.72 (1.81) |

| SIS | 4.02 (0.97) | 5.22 (2.09)* | 4.54 (1.37) | 7.24 (1.45) | 8.74 (0.69)*+ | |

| ST2 | SES | 8.56 (2.27) | 9.80 (1.93) | 11.19 (2.76)+ | 16.85 (1.76) | 17.19 (1.93) |

| SIS | 5.15 (0.59) | 7.04 (1.55) | 7.44 (1.35) | 8.81 (1.52) | 12.48 (0.61)* | |

| Cue | SES | 6.48 (1.72) | 9.30 (2.16) | 8.46 (1.83) | 11.98 (2.39) | 11.89 (1.75) |

| SIS | 6.06 (1.33) | 9.22 (1.7) | 7.02 (1.8) | 9.72 (1.54) | 13.65 (1.28) | |

| F3,48 = 3.16, P < 0.04 (I) | F1,16 = 4.59, P < 0.05 (Gp; SES > SIS) | F3,48 = 6.84, P < 0.001 (I) | ||||

| REM Percentage | ||||||

| Baseline | SES | 6.30 (0.66) | 5.68 (1.11) | 6.06 (1.51) | 7.30 (1.49) | 9.58 (0.93) |

| SIS | 6.35 (1.12) | 6.85 (0.87) | 5.83 (1.7) | 9.40 (1.13) | 10.48 (0.79) | |

| ST1 | SES | 6.08 (1.46) | 12.35 (1.38)+ | 12.17 (1.3) | 11.98 (0.77)+ | 12.56 (0.92)+ |

| SIS | 3.10 (0.75) | 3.74 (1.17)* | 5.47 (0.99) | 7.11 (1.04)* | 6.65 (0.53)*+ | |

| ST2 | SES | 6.57 (1.26) | 9.27 (1.71) | 12.32 (2.02) | 12.82 (0.59)+ | 12.28 (0.67)+ |

| SIS | 3.93 (0.51) | 5.85 (1.38) | 8.77 (1.11) | 6.88 (0.96)* | 9.36 (0.9)* | |

| Cue | SES | 6.18 (1.51) | 7.59 (1.4) | 10.34 (1.17) | 9.71 (1.66) | 9.43 (0.94) |

| SIS | 5.69 (0.8) | 6.92 (1.12) | 9.17 (1.63) | 9.01 (0.83) | 10.15 (0.86) | |

| F3,48 = 7.85, P < 0.001 (I) | F1,16 = 5.64, P < 0.03 (Gp; SES > SIS) | F3,48 = 8.11, P < 0.001 (I) | F3,48 = 10.55, P < 0.001 (I) | |||

| REM Count | ||||||

| Baseline | SES | 13.67 (2.34) | 7.44 (2.48) | 6.33 (2.75) | 10.00 (2.01) | 13.67 (1.76) |

| SIS | 13.44 (2.38) | 11.56 (2.19) | 5.11 (1.5) | 11.33 (2.19) | 16.89 (1.82) | |

| ST1 | SES | 11.33 (2.91) | 15.22 (1.51)+ | 10.22 (2.42) | 13.11 (1.49) | 16.44 (1.52) |

| SIS | 5.78 (1.19) | 7.11 (2.34)* | 6.67 (1.9) | 9.11 (1.23) | 10.33 (1.31)*+ | |

| ST2 | SES | 12.56 (3.19) | 11.11 (2.45) | 11.33 (2.86) | 14.11 (1.45) | 18.78 (2.26) |

| SIS | 8.89 (1.54) | 9.22 (1.64) | 9.89 (1.7) | 10.56 (1.51) | 14.44 (1.6) | |

| Cue | SES | 8.67 (2.0) | 11.00 (2.33) | 8.56 (1.68) | 11.78 (2.64) | 14.22 (2.49) |

| SIS | 7.22 (1.66) | 14.22 (2.6) | 9.00 (1.62) | 12.56 (2.32) | 16.22 (1.28) | |

| F3,48 = 6.08, P < 0.002 (T; ST1 > Bas; Cue > Bas) | F3,48 = 4.92, P < 0.005 (I) | F3,48 = 4.48, P < 0.001 (I) | ||||

| REM Duration | ||||||

| Baseline | SES | 0.67 (0.05) | 0.74 (0.09) | 0.74 (0.11) | 0.84 (0.14) | 1.03 (0.08) |

| SIS | 0.65 (0.07) | 0.69 (0.06) | 0.61 (0.11) | 0.94 (0.15) | 0.91 (0.08) | |

| ST1 | SES | 0.63 (0.1) | 0.80 (0.07) | 0.82 (0.09) | 1.01 (0.11) | 1.07 (0.07) |

| SIS | 0.55 (0.1) | 0.63 (0.1) | 0.73 (0.14) | 0.77 (0.09) | 0.93 (0.11) | |

| ST2 | SES | 0.65 (0.12) | 0.84 (0.13) | 1.00 (0.17) | 1.24 (0.12) | 0.99 (0.11) |

| SIS | 0.63 (0.07) | 0.82 (0.13) | 0.79 (0.08) | 0.81 (0.08) | 0.93 (0.1) | |

| Cue | SES | 0.69 (0.17) | 0.83 (0.12) | 0.95 (0.09) | 0.92 (0.15) | 0.88 (0.06) |

| SIS | 0.87 (0.06) | 0.66 (0.06) | 0.74 (0.09) | 0.82 (0.09) | 0.86 (0.06) |

Indicated F values for ANOVAs conducted on each block are Group main effects (indicated by Gp), Treatment main effects (T) or Group × Treatment interactions (I).

Significant differences between SES and SIS mice

Significant differences compared to baseline within blocks (P < 0.05, Tukey test). Significant differences for Group or Treatment main effects are indicated in parenthesis (P < 0.05, Tukey test).

Effects of SES and SIS on NREM and Total Sleep Time

The analyses for total NREM over the 20-h recording period (Figure 6 A) showed a significant main effect for treatment (F1,16 = 5.061, P <; 0.004) and a significant group × treatment interaction (F3,48 = 3.05, P <; 0.04). Compared to SES mice, SIS mice showed greater total 20-h NREM on ST1 and ST2. Compared to baseline, SIS showed more NREM on ST2. There were no significant group or treatment effects on NREM episode number or duration.

Figure 6.

Selected sleep and waking parameters plotted as 20-h totals for baseline (Bas), shock training days 1 and 2 (ST1, ST2), and cue test day alone (Cue). (A) Total NREM. (B) Total sleep time (TST). (C) Active wakefulness (AW). (D) Total Activity. Significant differences between SES and SIS: *P <; 0.05. Significant differences in SIS mice compared to Bas: ##P < 0.01 (Tukey tests). There was no significant difference between SES and SIS mice in either active wakefulness or total activity. However, active wakefulness was reduced on ST2 compared to baseline, ST1 and the Cue test day and total activity was increased on the Cue test day compared to baseline and ST2. Common letters indicate similar treatment effects and different letters indicate significantly different treatment effects (P < 0.05, Tukey tests). Error bars are ± SEM.

In the analysis of NREM in 4-h blocks (Table 2), there was a significant main effect for treatment (F3,48 = 6.66, P < 0.001) in Block 1. NREM amounts were greater in baseline (P < 0.001), ST1 (P < 0.01) and ST2 (P < 0.02) compared to the Cue test day. In Block 2, there was a significant difference between SES and SIS trained mice (F1,16 = 9.03, P < 0.009), with SIS trained mice showing greater NREM (P < 0.009).

Table 2.

Time (Min) or activity counts for selected parameters (mean and SEM) in 4-h blocks across the 20-h recording period for baseline (Bas), shock training day 1 (ST1), shock training day 2 (ST2), and the tone-cue day (Cue) in mice trained with signaled escapable shock (SES) and yoked control mice trained with signaled inescapable shock (SIS).

| NREM | Group | Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | Block 4 | Block 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | SES | 120.26 (7.53) | 77.70 (11.32) | 70.00 (13.48) | 99.83 (10.71) | 126.15 (6.98) |

| SIS | 132.33 (8.18) | 102.06 (11.62) | 54.15 (8.72) | 92.76 (11.9) | 124.26 (4.81) | |

| ST1 | SES | 107.46 (17.27) | 90.76 (10.06) | 59.70 (12) | 93.70 (11.05) | 120.65 (7.52) |

| SIS | 131.72 (8.97) | 118.44 (9.56) | 66.78 (12.78) | 99.31 (13.83) | 123.33 (5.21) | |

| ST2 | SES | 105.46 (15.42) | 85.17 (9.8) | 69.56 (16.23) | 114.33 (10.42) | 118.50 (9.79) |

| SIS | 130.09 (10.94) | 113.67 (7.88) | 81.17 (11.7) | 116.00 (9.87) | 128.93 (11.11) | |

| Cue | SES | 88.93 (14.1) | 100.35 (13.31) | 72.19 (16.04) | 93.22 (13.19) | 108.65 (7.87) |

| SIS | 100.91 (15.56) | 119.22 (6.64) | 75.57 (12.81) | 94.56 (12.81) | 121.00 (5.94) | |

| F3,48 = 6.66, P < 0.001 (T; Cue < Bas = ST1 = ST2) | F1,16 = 9.03, P < 0.009 (Gp; SIS > SES) | |||||

| Total Sleep Time | ||||||

| Baseline | SES | 128.48 (8.23) | 82.89 (12.53) | 74.98 (14.66) | 108.98 (12.52) | 139.87 (8.41) |

| SIS | 141.11 (8.4) | 109.65 (12.69) | 58.15 (9.76) | 102.65 (13.46) | 138.98 (5.78) | |

| ST1 | SES | 115.52 (18.85) | 102.72 (10.35) | 68.37 (13.96) | 106.83 (12.93) | 138.37 (9.03) |

| SIS | 135.74 (8.95) | 123.67 (10.9) | 71.32 (13.87) | 106.56 (14.96) | 132.07 (5.44) | |

| ST2 | SES | 114.02 (17.19) | 94.96 (11.14) | 80.74 (18.91) | 131.19 (11.95) | 135.69 (11.64) |

| SIS | 135.24 (11.14) | 120.70 (8.36) | 88.61 (12.71) | 124.81 (10.76) | 141.41 (11.46) | |

| Cue | SES | 95.41 (14.9) | 109.65 (15.07) | 80.65 (17.66) | 105.2 (15.38) | 120.54 (9.42) |

| SIS | 106.96 (16.63) | 128.44 (7.71) | 82.59 (14.17) | 104.23 (14.15) | 134.65 (6.5) | |

| F3,48 = 2.82, P < 0.05 (I) | F1,16 = 5.34, P < 0.04 (Gp; SIS > SES); F3,48 = 2.90, P < 0.05 (T; Cue > Bas) | |||||

| Active Wakefulness | ||||||

| Baseline | SES | 52.26 (7.68) | 80.56 (12.83) | 88.94 (11.47) | 66.76 (5.92) | 42.11 (4.65) |

| SIS | 36.43 (5.47) | 52.67 (6.94) | 99.57 (15.45) | 71.44 (12.88) | 41.26 (6.28) | |

| ST1 | SES | 71.70 (20.24) | 66.18 (10.35) | 99.61 (15.07) | 72.13 (12.1) | 43.46 (4.86) |

| SIS | 42.81 (6.56) | 47.52 (6) | 82.76 (14.96) | 68.98 (14.81) | 47.06 (5.62) | |

| ST2 | SES | 65.20 (15.4) | 62.96 (8) | 94.26 (19.34) | 56.39 (9.02) | 51.06 (12.22) |

| SIS | 41.56 (8.07) | 51.74 (4.9) | 71.24 (10.22) | 49.09 (8.51) | 37.83 (8.9) | |

| Cue | SES | 97.76 (17.73) | 71.04 (15.58) | 92.00 (13.12) | 76.59 (15.66) | 62.3 (11.07) |

| SIS | 77.82 (15.93) | 48.76 (5.19) | 78.33 (15.03) | 67.13 (12.26) | 42.32 (5.52) | |

| F3,48 = 7.41, P < 0.001 (T; Cue > Bas = ST1 = ST2) | ||||||

| Total Activity | ||||||

| Baseline | SES | 8038 (1895) | 11921 (2557) | 14263 (2364) | 9924 (579) | 5654 (863) |

| SIS | 4980 (912) | 6687 (996) | 17999 (5202) | 12630 (4197) | 5631 (1165) | |

| ST1 | SES | 13923 (5207) | 13153 (2193) | 18758 (3637) | 13609 (3381) | 6477 (962) |

| SIS | 5659 (1124) | 6845 (988) | 15267 (4928) | 15772 (6849) | 7665 (1766) | |

| ST2 | SES | 12031 (4173) | 9615 (1758) | 17682 (3958) | 10640 (2388) | 8747 (3026) |

| SIS | 5535 (1034) | 6925 (739) | 12658 (3311) | 9269 (3663) | 5343 (1629) | |

| Cue | SES | 21868 (6557) | 13823 (4836) | 17357 (2745) | 14237 (3774) | 11694 (3028) |

| SIS | 12921 (3119) | 7471 (1052) | 16221 (6628) | 11666 (3019) | 6517 (1099) | |

| F3,48 = 8.13, P < 0.001 (T; Cue > Bas = ST1 = ST2) | F1,16 = 4.95, P < 0.05 (Gp; SES > SIS) |

Indicated F values for ANOVAs conducted on each block are Group main effects (indicated by Gp), main effect for treatment (indicated by T), or Group × Treatment interactions (I). Significant differences for Group and Treatment main effects are indicated in parenthesis (P < 0.05, Tukey test).

The analyses for TST over the 20-h recording period (Figure 6 B) showed a significant main effect for treatment (F3,48 = 6.03, P < 0.001). TST was increased on ST2 compared to baseline, ST1, and the Cue test day.

The analyses for TST in 4-h blocks (Table 2) showed a significant group × treatment interaction (F3,48 = 2.82, P < 0.05) for Block 1, but the post hoc analyses did not reveal any significant differences. In Block 2, significant main effects for both group (F1,16 = 5.34, P < 0.04) and treatment (F3,48 = 2.90, P < 0.05) were found. SIS showed greater TST (P < 0.04) and there was greater TST during the Cue test day than during baseline (P < 0.03).

Effects of SES and SIS on Latency to Sleep

Within-groups and across-groups comparisons of latencies to NREM (SES: ST1: 40.81 ± 13.55; ST2: 42.43 ± 11.21; Cue: 118.52 ± 41.54; SIS: ST1: 30.96 ± 8.68; ST2: 21.59 ± 6.27; Cue: 70.17 ± 18.29) and REM (SES: ST1: 116.13 ± 25.06; ST2: 102.12 ± 25.28; Cue: 148.28 ± 42.22; SIS: ST1: 155.87 ± 56.68; ST2: 96.74 ± 9.07; Cue: 105.99 ± 17.88) did not reach significance. This was likely due to the high degree of variability within animals in each condition.

Effects of SES and SIS on Active Wakefulness and Activity

The analyses for active wakefulness over the 20-h recording period (Figure 6 C) showed a significant main effect for treatment (F3,48 = 8.49, P < 0.001). Active wakefulness was reduced on ST2 compared to baseline, ST1, and the Cue test day.

In the analysis of 4-h blocks (Table 2), there was a significant main effect for treatment (F3,48 = 7.41, P < 0.001) in Block 1. There was greater active wakefulness on the Cue test day than during baseline (P < 0.001), ST1 (P < 0.002), or ST2 (P < 0.001).

The analyses for activity over the 20 h recording period (Figure 6 D) showed a significant main effect for treatment (F3,48 = 4.73, P < 0.006). Activity was greater on the Cue test day compared to Baseline and ST2. The apparent differences between the SES and SIS mice were not statistically significant.

The analyses for activity in 4-h blocks (Table 2) revealed a significant main effect for treatment (F3,48 = 8.13, P < 0.001) in Block 1. There was greater activity on the Cue test day than during baseline (P < 0.001), ST1 (P < 0.002), or ST2 (P < 0.004). In Block 2, there was a significant main effect for group (F1,16 = 4.95, P < 0.05). The SES mice showed greater activity (P < 0.05) than did the SIS mice.

Effects of Cue on Sleep

Because we did not see large differences in the SES and SIS mice in responses to the Cue when the data were considered in 4-h blocks, we looked at the hourly response during the first 4 h of recording for amounts of REM (Figure 7 A [SES]; C [SIS]) and NREM (Figure 7 B [SES]; D [SIS]). The ANOVA revealed no significant differences between SES and SIS mice during this early recording period after Cue alone presentation. However, there were significant treatment effects for REM and NREM. Total REM was significantly reduced during hour 1 (F1,16 = 27.01, P < 0.001) and hour 2 (F1,16 = 8.07, P < 0.02), and total NREM was significantly reduced during hour 1 (F1,16 = 77.23, P < 0.001).

Figure 7.

Total REM and NREM plotted for the first 4 hours of baseline (Bas) and the cue test day (Cue) to demonstrate similarities between SES and SIS mice. (A) REM plotted for SES mice. (B) NREM plotted for SES mice. (C) REM plotted for SIS mice. (D) NREM plotted for SIS mice. The overall ANOVA did not reveal significant differences between SES and SIS mice and significance levels for the 2 groups are not indicated separately. However, REM was significantly reduced in hour 1 (P < 0.001) and hour 2 (P < 0.02) and total NREM was significantly reduced during hour 1 (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates that predictable, controllable stress (modeled by SES) and predictable, uncontrollable stress (modeled by SIS) produce different patterns and amounts of post-stress sleep. In general, mice trained with SES showed greater amounts of REM whereas mice trained with SIS showed greater amounts of NREM. By comparison, the presentation of predictive, auditory cues alone produced similar post-stress changes in sleep (initial reductions in both NREM and REM) in mice trained with either SES or SIS. The presentation of the auditory cues alone also produced similar amounts of behavioral freezing and both training with SES and SIS, and the presentation of predictive auditory cues alone produced similar increases in core body temperature.

The present results suggest that predictable auditory cues can modify post-stress sleep relative to that after escapable and inescapable shock where predictive auditory cues are not presented.26 In general, the differences in post-stress REM after escapable and inescapable shock were more pronounced without predictive cues. Contexts associated with non-signaled escapable and inescapable shock also produced directionally different changes in REM similar to those seen when shock was presented,26 whereas predictive cues associated with SES and SIS produced directionally similar changes in REM. Taken together, these finding suggest that contexts and auditory cues associated with different shock training conditions may carry different and potentially competing types of information regarding the stressful situations. This may primarily apply to training with SES as contextual and cued fear associated with uncontrollable stress have similar effects on sleep in mice and both reduce REM.20,21 However, competing cued and contextual information for SES may have interacted during training, resulting in competing influences on REM. Future studies could examine the context and cue separately in mice trained with SES and SIS. This approach is often used in behavioral studies of conditioned fear using brief shock training paradigms31–34 and potentially could be useful for determining whether context and cue produce different effects on post-stress sleep after SES and SIS.

Experimental paradigms using uncontrollable stressors similar to the SIS component of the present study have often been viewed principally as involving classical conditioning. By comparison, the controllable stress (SES) component of the paradigm involves instrumental (operant) learning of the escape response. However, the yoked SIS mice also likely learn that their escape behaviors fail. Thus, neither group of animals should be viewed as learning simple classically conditioned associations. There have been suggestions that shuttlebox avoidance learning involves classical conditioning (when the association is made between the cue and footshock) and instrumental learning (when the animal learns to use the predictive value of the cue to enable an avoidance response).35 Similar learning likely exists for SES and SIS where the animals first make an association between the predictive cue and footshock. The deviation would occur when the SES mice learn the escape response and the SIS mice learn that escape is not possible.

A few studies have examined the relationship between conditioned fear and sleep with the goal of understanding the potential role of sleep in fear memory consolidation. These have typically used training procedures with single, or at most a few, tone-shock or context-shock pairings. This type of paradigm is likely more conducive to studies of memory consolidation,36 whereas the intensive multi-trial training paradigms we use are designed to enable examination of the effects of stress-related memories on sleep. Using a single shock presentation procedure, Graves et al.36 found that total sleep deprivation performed by a gentle handling procedure impaired memory consolidation for contextual fear when sleep was deprived from 0 to 5 h after training, but had no effect when sleep was deprived from 5 to 10 h after training. Cued fear was not altered by sleep deprivation in either time window. Similar results were found in a study that trained mice prior to the natural sleep/rest or wake/active phase of the circadian cycle and tested 12 or 24 h later, either with or without an intervening sleep/rest phase.34 Contextual, but not cued, fear was enhanced if a sleep/rest phase occurred between the training and testing segments of the experiment. While these studies do not link contextual fear learning to specific sleep states (NREM or REM), they do suggest that memory consolidation for cued fear may not require sleep or may require less sleep.

Similar reductions in REM after the presentation or cues associated with escapable and inescapable shock may seem inconsistent with findings that animals appear to prefer signaled over unsignaled shock.27 Indeed, the preference for predictability has been repeatedly demonstrated37–39 and seems to suggest that a signal that precedes shock enables an animal to prepare for the shock delivery in such a way that the impact of the shock is somehow reduced. However, the preference for predictability is affected by several factors including shock intensity, signal duration, inter-shock intervals, amount of training, and the dependability of shock-free periods.27 For example, some studies show that unpredictable conditions are more stressful than predictable conditions when subjects are exposed to them for one or a few sessions and parameters of stress are relatively severe.3 However, predictable conditions may be more stressful than unpredictable conditions when sessions are long and extend over days and parameters are less severe.3 Resilience is also a factor in how an animal responds to stress,40 and C mice are more reactive to stress than other commonly studied inbred strains, such as C57BL/6J mice. For instance, C mice exhibit greater anxiety-like behavior on a variety of behavioral tests41 and have been suggested to exhibit trait or pathological anxiety.42 Thus, their responses reflect an interaction between innate propensity toward greater reactions and the specific stress paradigm. Strain comparisons with more resilient animals and variations of stressor parameters will be required to determine the relative roles of each.

Stress produces elevations in body temperature along with other autonomic changes.28,29 These increases are produced by both physiological and psychological stress, are stable across repeated presentations of a stressor29 and can occur rapidly. For example, with restraint stress, changes in core temperature can begin within 10 s of the onset of restraint and temperature can rise as much as 2°C during the restraint period.43,44 Stress-induced hyperthermia is also sensitive to anxiolytic drugs, but not anxiogenic drugs, possibly due to ceiling effects of the stress-induced increase in temperature, i.e., there is a maximum limit to the temperature increase.29 In the current study, both SES and SIS mice showed significantly increased average body temperature in the first 2 hours after ST1, ST2, and cue. SES and SIS mice also showed similar time courses for the stress induced hyperthermia response across experimental days. These data indicate that both groups exhibited similar stress induced hyperthermia to the shock training and cue test portions of the experiments. As the time course of stress-induced hyperthermia parallels that of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation,45,46 these data also suggest that aspects of the initial stress response were similar, even though post-stress sleep could differ.

Behavioral freezing is a commonly used measure of fear and fear memory in rodents, with greater FT% being interpreted as indicating stronger fear reactions.47,48 The extensive training we provide virtually ensures well-learned responses, and any differences in freezing across groups should reflect differences in fear. In the present study, freezing in response to cues associated with SES and SIS was statistically equivalent in both groups of mice. This is consistent with results in a previous study, where we found statistically equivalent freezing to contexts associated with escapable or inescapable shock.26 However, presentation of cues associated with SES and SIS resulted in significant reductions in REM, whereas exposure to contexts associated with escapable and inescapable shock resulted in directionally different alterations in REM. Together, these data demonstrate that behavioral indices of fear alone may not predict directional changes subsequent sleep.

The neural substrate(s) underlying the effects of SES and SIS must account for differences in learning and memory, the production of similar stress responses, and the provision of pathways that enable directionally different post-stress alterations in sleep and arousal. Three regions strongly involved in these processes are the amygdala, hippocampus, and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).

The amygdala has a role in regulating physiological responses to stressors, adaptive behaviors and the regulation of stress-induced alterations in homeostasis (as recently reviewed49). It has a well-known role in mediating behaviors associated with conditioned fear,13,50 and it influences the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), the final common pathway for information influencing the HPA axis51,52 through the central nucleus of the amygdala (CNA) and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis.52 In addition, our own work and that of others has demonstrated that the amygdala is a strong modulator of arousal and sleep. It can influence the generation of REM53–55 and it projects prominently to a number of brainstem regions, including the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), the locus coeruleus (LC), and brainstem cholinergic cell groups56–58 that are linked to arousal and to the generation and control of REM.

Cued and contextual fear have been demonstrated to have different but overlapping neural substrates. Both require the amygdala, yet only contextual fear is thought to require the hippocampus15,59 (note though that the hippocampus appears to be required for contextual information that may modulate the expression of cued fear60). Incoming sensory information appears to be processed in a serial fashion.61 Fearful cues first activate the lateral amygdala followed by intra-amygdaloid processing, including the basal amygdala (BA), with behavioral responses initiated by the CNA. Fearful contexts are first processed in the hippocampus followed by lateral BA, with output again via CNA. The hippocampus also is involved in episodic, spatial, temporal memories as well as contextual memories62 and is likely involved in other aspects of learning and remembering the escape response.

The mPFC is a critical region in the perception of control and in mediating the consequences of stress.63,64 Part of the influence of mPFC appears to be enacted through its effects on the brainstem including the DRN, and possibly the LC,64 thereby providing pathways that could influence REM. For example, activation of mPFC inhibits DRN,63,64 which could promote REM. The mPFC may also influence the HPA axis through actions on the PVN.63 It appears to be important for the functional interface between learning and memory and their role in adaptive responses to stressors,64 and mPFC-amygdala circuitry is key for mediating the effects of stress, in particular, those related to learning and memory and the extinction of fearful responses.63

The amygdala, hippocampus and mPFC are interconnected and they interact with and influence each other.65,66 These regions are also strongly implicated in PTSD, which is characterized by emotional and arousal disturbances arising from a traumatic event. For example, in PTSD, activity in the amygdala positively correlates with severity of symptoms whereas the mPFC is volumetrically smaller and is inversely active with severity of symptoms.66,67 The hippocampus also appears to have reduced volume and reduced neuronal and functional integrity in PTSD.66,67 Thus, understanding the roles the amygdala, hippocampus and mPFC in modulating alterations in sleep induced by stress and stress-related memories should provide insight into stress-related disorders and their relationship to sleep.

Traumatic events can subject humans to complex processes by which interactions between stressor parameters, stress-related learning, emotion, and sleep can produce persisting pathology such as PTSD. Appropriate animal models are needed to accomplish these goals including understanding these interactions at a phenomenological level, determination of the neurobiological changes involved, and providing the basic information needed to devise improved treatments. Understanding the impact of mild stress will be important for understanding normal stress responses; however, it is likely that only strong, aversive stressors (such as footshock) have the potential to adequately model stressful situations that can produce pathological conditions. Our results as well as a number of previous studies demonstrate that stressor controllability and predictability1–4 also need to be considered in developing animal models with relevance for human stress-related disorders.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that predictable escapable and predictable inescapable footshock stress can be followed by different post-stress changes in sleep even though an important index of the initial stress response (stress-induced hyperthermia) is similar in both conditions. By comparison, auditory cues predictive of escapable and inescapable shock produce similar effects on post-stress sleep suggesting that these cues may be processed differently from the contextual information associated with the SES and SIS. Stressful experiences can vary on a number of parameters (e.g., predictability, controllability, intensity, and duration) that can impact whether the experience produces persisting effects or not. We suggest that experimental models varying stressor predictability and controllability (and other parameters) and including sleep as an outcome measure of stress may provide essential insight into the complex effects that stress can have on behavior and sleep.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH research grants MH61716 and MH64827.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bolstad BR, Zinbarg RE. Sexual victimization, generalized perception of control, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity. J Anxiety Disord. 1997;11:523–40. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foa EB, Zinbarg R, Rothbaum BO. Uncontrollability and unpredictability in post-traumatic stress disorder: an animal model. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:218–38. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbott BB, Schoen LS, Badia P. Predictable and unpredictable shock: behavioral measures of aversion and physiological measures of stress. Psychol Bull. 1984;96:45–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adell A, Trullas R, Gelpi E. Time course of changes in serotonin and noradrenaline in rat brain after predictable or unpredictable shock. Brain Res. 1988;459:54–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buydens-Branchey L, Noumair D, Branchey M. Duration and intensity of combat exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;178:582–7. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199009000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Natelson BH, Stress hormones and disease. Physiol Behav. 2004;82:139–43. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charney D, Deutch A. A functional neuroanatomy of anxiety and fear: implications for the pathophysiology and treatment of anxiety disorders. Critical Rev Neurobiol. 1996;10:419–46. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i3-4.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitman RK, Shin LM, Rauch SL. Investigating the pathogenesis of posttraumatic stress disorder with neuroimaging. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 17):47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavie P. Sleep disturbances in the wake of traumatic events. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1825–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koren D, Arnon I, Lavie P, Klein E. Sleep complaints as early predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder: a 1-year prospective study of injured survivors of motor vehicle accidents. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:855–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey AG, Jones C, Schmidt DA. Sleep and posttraumatic stress disorder: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:377–407. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis M. Animal models of anxiety based on classical conditioning: the conditioned emotional response (CER) and the fear-potentiated startle effect. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;47:147–65. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90084-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis M. The role of the amygdala in conditioned fear. In: Aggleton J, editor. The amygdala: neurobiological aspects of emotion, memory, and mental dysfunction. NY: Wiley-Liss; 1992. pp. 255–305. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paylor R, Tracy R, Wehner J, Rudy J. DBA/2 and C57BL/6 mice differ in contextual fear but not auditory fear conditioning Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:810–7. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:274–85. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nijsen M, Croiset G, Diamant M, et al. Conditioned fear-induced tachycardia in the rat: vagal involvement. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;350:211–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stiedl O, Tovote P, Ogren SO, Meyer M. Behavioral and autonomic dynamics during contextual fear conditioning in mice. Auton Neurosci. 2004;115:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papale LA, Andersen ML, Antunes IB, Alvarenga TA, Tufik S. Sleep pattern in rats under different stress modalities. Brain Res. 2005;1060:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanford L D, Fang J, Tang X. Sleep after differing amounts of conditioned fear training in BALB/cJ mice. Behav Brain Res. 2003;147:193–202. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanford LD, Tang X, Ross RJ, Morrison AR. Influence of shock training and explicit fear-conditioned cues on sleep architecture in mice: strain comparison. Behav Genet. 2003;33:43–58. doi: 10.1023/a:1021051516829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanford LD, Yang L, Tang X. Influence of contextual fear on sleep in mice: a strain comparison. Sleep. 2003;26:527–40. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.5.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madan V, Brennan FX, Mann GL, Horbal AA, Dunn GA, Ross RJ, Morrison AR. Long-term effect of cued fear conditioning on REM sleep microarchitecture in rats. Sleep. 2008;31:497–503. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pawlyk AC, Morrison AR, Ross RJ, Brennan FX. Stress-induced changes in sleep in rodents: models and mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:99–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adrien J, Dugovic C, Martin P. Sleep-wakefulness patterns in the helpless rat. Physiol Behav. 1991;49:257–62. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90041-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wellman LL, Yang L, Tang X, Sanford LD. Contextual fear extinction ameliorates sleep disturbances found following fear conditioning in rats. Sleep. 2008;31:1035–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanford LD, Yang L, Wellman LL, Liu X, Tang X. Differential effects of controllable and uncontrollable footshock stress on sleep in mice. Sleep. 2010;33:621–30. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badia P, Harsh J, Abbott B. Choosing between predictable and unpredictable shock conditions: data and theory. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:1107–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Bogaert MJ, Groenink L, Oosting RS, Westphal KG, van der Gugten J, Olivier B. Mouse strain differences in autonomic responses to stress. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5:139–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinckers CH, van Oorschot R, Olivier B, Groenink L. Stress-induced hyperthermia in the mouse. In: Gould TD, editor. Mood and anxiety-related phenotypes in mice: characterization using behavioral tests. NY: Humana Press; 2009. pp. 139–52. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang X, Sanford LD. Telemetric recording of sleep and home cage activity in mice. Sleep. 2002;25:691–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelley JB, Balda MA, Anderson KL, Itzhak Y. Impairments in fear conditioning in mice lacking the nNOS gene. Learn Mem. 2009;16:371–8. doi: 10.1101/lm.1329209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood SC, Anagnostaras SG. Memory and psychostimulants: modulation of Pavlovian fear conditioning by amphetamine in C57BL/6 mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;202:197–206. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunsaker MR, Kesner RP. Dissociations across the dorsal-ventral axis of CA3 and CA1 for encoding and retrieval of contextual and auditory-cued fear. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai DJ, Shuman T, Gorman MR, Sage JR, Anagnostaras SG. Sleep selectively enhances hippocampus-dependent memory in mice. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:713–9. doi: 10.1037/a0016415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hulse S, Egeth H, Deese J. The psychology of learning. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graves LA, Heller EA, Pack AI, Abel T. Sleep deprivation selectively impairs memory consolidation for contextual fear conditioning. Learn Mem. 2003;10:168–76. doi: 10.1101/lm.48803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.French D, Palestine D, Leeb C. Preference for a warning in an unavoidable shock situation: Replication and extension. Psychol Rep. 1972;30:72–4. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gliner JA. Predictable vs. unpredictable shock: preference behavior and stomach ulceration. Physiol Behav. 1972;9:693–8. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(72)90036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller RR, Daniel D, Berk AM. Successive reversals of a discriminated preference for signaled tailshock. Anim Learn Behav. 1974;2:271–4. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yehuda R, Flory JD, Southwick S, Charney DS. Developing an agenda for translational studies of resilience and vulnerability following trauma exposure. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:379–96. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang X, Orchard SM, Sanford LD. Home cage activity and behavioral performance in inbred and hybrid mice. Behav Brain Res. 2002;136:555–69. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belzung C, Griebel G. Measuring normal and pathological anxiety-like behaviour in mice: a review. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:141–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clement J G, Mills P, Brockway B. Use of telemetry to record body temperature and activity in mice. J Pharmacol Methods. 1989;21:129–40. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(89)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krarup A, Chattopadhyay P, Bhattacharjee AK, Burge JR, Ruble GR. Evaluation of surrogate markers of impending death in the galactosamine-sensitized murine model of bacterial endotoxemia. Lab Anim Sci. 1999;49:545–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Groenink L, van der Gugten J, Zethof T, van der Heyden J, Olivier B. Stress-induced hyperthermia in mice: hormonal correlates. Physiol Behav. 1994;56:747–9. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veening JG, Bouwknecht JA, Joosten HJ, et al. Stress-induced hyperthermia in the mouse: c-fos expression, corticosterone and temperature changes. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28:699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC. Crouching as an index of fear. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1969;67:370–5. doi: 10.1037/h0026779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doyere V, Gisquet-Verrier P, de Marsanich B, Ammassari-Teule M. Age-related modifications of contextual information processing in rats: role of emotional reactivity, arousal and testing procedure. Behav Brain Res. 2000;114:153–65. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berretta S. Cortico-amygdala circuits: role in the conditioned stress response. Stress. 2005;8:221–32. doi: 10.1080/10253890500489395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis M, Whalen PJ. The amygdala: vigilance and emotion. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6:13–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herman P, Mueller NK, Figueiredo H. Role of GABA and glutamate circuitry in hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical stress integration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1018:35–45. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pacak K, Palkovits M. Stressor specificity of central neuroendocrine responses: implications for stress-related disorders. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:502–48. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.4.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calvo J, Simón-Arceo K, Fernández-Mas R. Prolonged enhancement of REM sleep produced by carbachol microinjection into the amygdala. NeuroRep. 1996;7:577–80. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199601310-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanford LD, Tejani-Butt SM, Ross RJ, Morrison AR. Amygdaloid control of alerting and behavioral arousal in rats: involvement of serotonergic mechanisms. Arch Ital Biol. 1995;134:81–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanford LD, Yang L, Liu X, Tang X. Effects of tetrodotoxin (TTX) inactivation of the central nucleus of the amygdala (CNA) on dark period sleep and activity. Brain Res. 2006;1084:80–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peyron C, Petit JM, Rampon C, Jouvet M, Luppi PH. Forebrain afferents to the rat dorsal raphe nucleus demonstrated by retrograde and anterograde tracing methods. Neuroscience. 1998;82:443–68. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Price J, Russchen F, Amaral D. The limbic region. II: The amygdaloid complex, in Handbook of chemical neuroanatomy. In: Swanson L, editor. Integrated systems of the CNA, Part I. NY: Elsevier; 1987. pp. 279–375. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Semba K, Fibiger HC. Afferent connections of the laterodorsal and the pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei in the rat: a retro- and antero-grade transport and immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol. 1992;323:387–410. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Desmedt A, Garcia R, Jaffard R. Differential modulation of changes in hippocampal-septal synaptic excitability by the amygdala as a function of either elemental or contextual fear conditioning in mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18:480–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00480.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ji J, Maren S. Electrolytic lesions of the dorsal hippocampus disrupt renewal of conditional fear after extinction. Learn Mem. 2005;12:270–6. doi: 10.1101/lm.91705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kenney JW, Gould TJ. Modulation of hippocampus-dependent learning and synaptic plasticity by nicotine. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;38:101–21. doi: 10.1007/s12035-008-8037-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akirav I, Maroun M. The role of the medial prefrontal cortex-amygdala circuit in stress effects on the extinction of fear. Neural Plast. 2007;2007:30873. doi: 10.1155/2007/30873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maier SF, Amat J, Baratta MV, Paul E, Watkins LR. Behavioral control, the medial prefrontal cortex, and resilience. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:397–406. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.4/smaier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rao PP, Suvrathan A, Miller MA, McEwen BS, Chattarji S. PTSD: From neurons to networks. In: Shiromani PJ, Keane TM, Ledoux JE, editors. Post-traumatic stress disorder: basic science and clinical practice. NY: Humana Press; 2009. pp. 151–84. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shin LM, Rauch SL, Pitman RK. Amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal function in PTSD. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:67–79. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]