Abstract

Study Objectives:

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of electroacupuncture as an additional treatment for residual insomnia associated with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Design:

Randomized, placebo-controlled.

Setting:

A psychiatric outpatient clinic.

Participants:

78 Chinese patients with DSM-IV-diagnosed MDD, insomnia complaint, a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS17) score ≤ 18, and fixed antidepressant dosage.

Intervention:

Electroacupuncture, minimal acupuncture (superficial needling at non-acupuncture points), or noninvasive placebo acupuncture 3 sessions weekly for 3 weeks.

Measurements and Results:

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), HDRS17, 1 week sleep diaries, and 3 day actigraphy were administered at baseline, 1 week post-treatment, and 4 week post-treatment. There was significant group by time interaction in ISI, PSQI, and sleep diary-derived sleep efficiency (mixed-effects models, P = 0.04, P = 0.03, and P = 0.01, respectively). Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that electroacupuncture and minimal acupuncture were more efficacious than placebo acupuncture in ISI and PSQI at 1 week and 4 week post-treatment. Minimal acupuncture resulted in greater improvement in sleep diary-derived sleep efficiency than placebo acupuncture at 1 week post-treatment. There was no significant between-group difference in actigraphy measures, depressive symptoms, daily functioning, and hypnotic consumption, and no difference in any measures between electroacupuncture and minimal acupuncture.

Conclusion:

Compared with placebo acupuncture, electroacupuncture and minimal acupuncture resulted in greater improvement in subjective sleep measures at 1 week and 4 week post-treatment. No significant difference was found between electroacupuncture and minimal acupuncture, suggesting that the observed differences could be due to nonspecific effects of needling, regardless of whether it is done according to traditional Chinese medicine theory.

Clinical Trial Information:

Acupuncture for Residual Insomnia Associated with Major Depressive Disorder; Registration #NCT00838994; URL - http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00838994?term = NCT00838994&rank = 1

Citation:

Yeung WF; Chung KF; Tso KC; Zhang SP; Zhang ZJ; Ho LM. Electroacupuncture for residual insomnia associated with major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. SLEEP 2011;34(6):807-815.

Keywords: Acupuncture, electroacupuncture, insomnia, residual insomnia, major depressive disorder, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common and disabling mental health problems.1 Although effective pharmacological and psychological treatments for MDD are available, a sizable proportion are partially responded to treatment and left with residual depressive symptoms.2 Insomnia is one of the most common and clinically important residual symptoms. Nierenberg et al.3 found a high residual insomnia rate (44%) among patients who showed remission of other MDD symptoms after fluoxetine 20 mg for 8 weeks. In a STAR*D report of 943 depression remitters after treatment with citalopram, the most common residual symptom domain was sleep disturbance (72%), followed by appetite and weight disturbance (36%).4 Carney et al.5 found that the rate of residual insomnia after pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy was 53% and 50%, respectively, suggesting that drug side effects could not account for all the residual insomnia symptoms. There are a number of longitudinal studies showing that residual insomnia hinders response to treatment and confers an increased risk for depression relapse.6,7

Several reports have shown that augmenting antidepressants with short-acting benzodiazepines, non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, or cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia can alleviate both depression and insomnia in patients with comorbid MDD and insomnia.8–10 There have been limited studies on the treatment of residual insomnia after remission or partial response of depression. Asnis et al.11 showed that compared with placebo group, depressed patients with persistent insomnia who received zolpidem had significantly better sleep and daytime functioning. In a randomized controlled trial of MDD patients treated with fluoxetine or bupropion, then either trazodone or placebo, trazodone augmentation was associated with significant improvement in a number of sleep parameters compared with placebo.12

Although pharmacologic treatment or cognitive-behavioral therapy will alleviate residual insomnia associated with MDD, pharmacotherapies are associated with dependence, potential abuse, and adverse effects,13 and cognitive-behavioral therapy has remained underutilized because of the time-intensive nature, requirement of significant training, and ethnocultural issues.14,15 Faced with the limitations of the currently available treatments, we have conducted the first randomized controlled trial of electroacupuncture as an additional treatment for residual insomnia associated with MDD. There have been controversies about the physiological mechanisms of acupuncture, and hence the method of needling practices, optimal mode of stimulation and selection of acupuncture points.16 In the present study, we compared the efficacy of electroacupuncture, minimal acupuncture and placebo acupuncture for residual insomnia in MDD patients after remission or partial response with a stable dosage of antidepressants.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a randomized, single-blinded, parallel-group study designed to examine the short-term effects of acupuncture. Major assessments were at baseline, 1 week post-treatment, and 4 week post-treatment. We followed the CONSORT and STRICTA recommendations in designing and reporting of controlled trials.17,18

Subjects

The study was conducted at the outpatient clinic of the Department of Psychiatry at Queen Mary Hospital, a regional teaching hospital in Hong Kong. Subjects were recruited from December 2007 to April 2009 through referrals from psychiatrists and advertisement at the clinic. The inclusion criteria were: (1) ethnic Chinese; (2) age 18 to 65 years; (3) chief complaint of insomnia; (4) previous diagnosis of MDD based on the DSM-IV criteria, as assessed by a clinician; (5) 17 item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS17) score ≤ 18 at screening and baseline; and (6) taking the same antidepressants at a fixed dose for 12 weeks prior to baseline. Previous studies of residual insomnia associated with MDD have examined patients with various levels of depression severity.3–7,11,12 We aimed to obtain a broader group of depressed patients with insomnia complaint, hence had used a wider range of HDRS17 score.

Subjects were excluded if they: (1) had any symptoms suggestive of specific sleep disorders, as assessed by Insomnia Interview Schedule, a semi-structured face-to-face interview19; (2) had a significant risk of suicide; (3) had previous diagnosis of schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, or alcohol or substance use disorder; (4) were pregnant, breast-feeding, or a woman of childbearing potential not using adequate contraception; (5) had valvular heart defects or bleeding disorders or were taking anticoagulant drugs; (6) had infection or abscess close to the site of selected acupoints; (7) had any serious physical illness; or (8) were taking Chinese herbal medicine or over-the-counter drugs intended for insomnia. Additional exclusion criterion was an apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 10 or a periodic limb movement disorder index with arousal ≥ 15, as assessed by overnight polysomnography in a subgroup of participants who consented to the investigation. No subjects were paid for participation. However, the acupuncture treatment, which costs US$20-30 per session in Hong Kong, was provided free of charge.

Study Procedure

All procedures used in the present study were reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board. Subjects showing an interest in participating in the study were initially assessed via telephone. After given written informed consent, potential subjects participated in a comprehensive face-to-face interview to provide a more detailed history. Laboratory-based overnight polysomnography (Alice 4 Diagnostics System, Respironics, Atlanta, GA) was arranged to rule out specific sleep disorders in 45 participants who consented to the investigation. Electroencephalography (C3/A2 and C4/A1), electrooculography, and submental and bilateral anterior tibialis electromyography were recorded using surface electrodes. Airflow was measured by thermistors, respiratory movements by impedance plethysmography, and arterial oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry. The electrocardiogram was also assessed. Sleep variables were analyzed according to the standard Rechtschaffen and Kales criteria20 by a registered polysomnographic technologist.

The subjects completed a 1 week sleep diary and a 3 day actigraphy recording in the week prior to a scheduled baseline visit. At the baseline visit, the subjects returned the completed sleep records, filled out a set of self-reported questionnaires, and were assessed using the HDRS17. Eligible subjects were then randomly assigned to electroacupuncture, minimal acupuncture, or placebo acupuncture in a ratio of 1:1:1 by an independent administrator using a computer-generated list of numbers21 with a block size of 6 and received their first treatment on the same day. At 1 week and 4 week post-treatment visits, the subjects returned the 1 week sleep diary and 3 day actigraph recording for the previous week and completed the same assessments.

The subjects were explained that in this study, different types of acupuncture would be compared. They were told that “traditional acupuncture” had been used in conventional Chinese medicine practice; “non-traditional acupuncture” did not follow the principles of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), but had also been associated with positive outcomes in clinical studies; and placebo acupuncture was a procedure which mimicked the real acupuncture procedure. Due to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind the only acupuncturist in this study. The assessment of depressive symptoms, past psychiatric history, and antidepressant treatment history was conducted by a clinician. The analysis of questionnaires, sleep diaries, and actigraphy results were conducted by independent investigators who were blinded to the subjects' group allocation.

Intervention

Subjects were treated 3 times per week for 3 consecutive weeks. All acupuncture treatments were performed in a quiet treatment room by the same acupuncturist, who had 3 years of clinical experience of providing acupuncture treatment. The thrice-weekly treatment schedule, same as in our previous study,22 was selected to enhance treatment adherence, and the 3 week treatment duration was chosen to examine the short-term effect of acupuncture. The subjects were advised to continue the same type and dosage of antidepressants throughout the study period. Sedatives, anxiolytics, and hypnotics could be continued during the study period, but dose escalation was disallowed.

Electroacupuncture

Subjects assigned to electroacupuncture were needled at Yintang (EX-HN3) and Baihui (GV20), and bilateral Ear Shenmen, Sishencong (EX-HN1), and Anmian (EX) using disposable acupuncture needles. The acupoints were located on the head and ears and the selection was based on our previous study on primary insomnia,22 a systematic review,16 and expert opinion. Deqi—a radiating feeling considered to be indicative of effective needling—was achieved if possible. Other details of needling procedure and electrostimulation can be found in Yeung et al.22

Minimal acupuncture

Subjects assigned to minimal acupuncture were needled superficially at bilateral “Deltoideus” (in the middle of the line insertion of Binao LI14 and acromion), “Forearm” (1 inch lateral to the middle point between Shaohai HE3 and Shenmen HE7), “Upper arm” (1 inch lateral to Tianfu LU3), and “Lower leg” (0.5 inch dorsal to Xuanzhong GB39). The points did not have any therapeutic effect for insomnia according to TCM theory, and point selection was based on a previous study that employed minimal acupuncture design.23 Deqi was avoided during needling. The acupuncturist, setting, number of points needled, electrostimulation, treatment frequency, and duration of the treatment course were the same as in the electroacupuncture group.

Placebo acupuncture

Subjects assigned to the placebo group were treated at the same acupoints as in the electroacupuncture group using placebo needles.24 The placebo needles were placed 1 inch beside the acupoints to avoid acupressure effect. The needles were then connected to the electric stimulator, but with zero frequency and amplitude. Additional details regarding the placebo acupuncture design can be found in Yeung et al.22

Measures

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)25 was used to assess the perceived severity of insomnia symptoms and the associated functional impairment. Global sleep disturbance was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).26 Both questionnaires are self-rating scales, with higher scores suggestive of greater severity of sleep disturbance. In this study, the first question of the ISI was phrased to assess insomnia severity in the past week, while the PSQI was used to evaluate sleep disturbances in the past month. The 1 week daily sleep diary inquired about bedtime and rising time, from which total time in bed (TIB) was calculated.27 Subjects were advised to estimate sleep onset latency (SOL), wake time after sleep onset (WASO), and total sleep time (TST). They also rated their sleep quality using a 4 point scale. Sleep efficiency (SE) was calculated as (TST/TIB × 100%). The frequency, dosage, and type of hypnotics were also recorded in the sleep diary. The weekly consumption of benzodiazepines or non-benzodiazepine hypnotics was calculated in mg of diazepam equivalent.28

In this study, actigraphs (Octagonal Basic Motionlogger, Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc., Ardsley, NY) were worn 24 h/d on the non-dominant wrist for 3 days prior to baseline and other study visits. A consensus report on research assessment of insomnia recommended a minimum of 3 days of actigraphy.29 Subjects were asked to press the actigraphy event marker to indicate “lights out” and rising time. We used Zero-Crossing Mode for quantification of wrist movement and ACTION-W 2.0 software to estimate SOL, WASO, TST, and SE using 1 min epochs.

Pharmacologic treatment history was obtained for the 12 months preceding baseline visit using the Antidepressant Treatment History Form (ATHF).30 Pharmacotherapy failure was defined as a score ≥ 3 on the ATHF scale of 0 to 5, which scores the adequacy of antidepressant treatment trials for major antidepressant categories and electroconvulsive therapy. The ATHF has been shown to have good reliability and validity.30,31

The HDRS17 was administered by an experienced psychiatrist (KCT) who was blind to treatment allocation.32 The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) was used to assess occupational, family, and social functioning during the past month33; a higher score is indicative of more severe impairment. The Credibility of Treatment Rating Scale (CTRS) was used to assess the subjects' “perceived logic of the treatment,” “confidence in the treatment to alleviate your complaint,” “confidence in recommending the treatment to your friends who have similar complaints,” and “likelihood that the treatment would alleviate your other complaints.”34 The CTRS was completed after the 2nd and 9th treatment sessions; a lower score is suggestive of greater confidence toward the received treatment.

All self-report questionnaires were presented in the Chinese language. The Chinese version of PSQI has been shown to be reliable and valid.35 The ISI, SDS, and CTRS were translated into Chinese using a 2 phase technique.36,37 Details of the validity of the Chinese version of ISI can be found in our previous study.22

Statistical Analysis

We used SPSS version 16.0 for basic statistical analysis and STATA 10 for linear mixed-effects regression modeling. Subjects who received at least one session of acupuncture were included in the statistical analysis. Baseline differences between treatment groups were examined using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or χ2 test. The effects of the intervention over time were assessed using the mixed-effects modeling group (electroacupuncture, minimal acupuncture, and placebo acupuncture) by time (baseline, 1 week and 4 week post-treatment) interaction. Because insomnia subtype and severity of depressive symptoms may affect treatment response, additional subgroup analyses were performed. Treatment impact was estimated by standardized within-group and between-group effect size.38 The within-group effect size was the difference between pre-treatment and post-treatment means divided by the pooled standard deviation, whereas the between-group effect size was computed as the between-group difference in post-treatment means divided by the pooled standard deviation.

Our sample size estimation was based on changes in ISI score, the primary outcome measure. A clinically significant treatment effect was defined as ≥ 4 point difference in ISI total score between treatment groups. Based on our previous study,22 a sample of 19 in each group would have a power of 80% to detect a 4 point difference between groups at an α level of 0.05.39 Allowing a 20% attrition rate, we estimated that this study would require a sample size of 26 in each group.

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

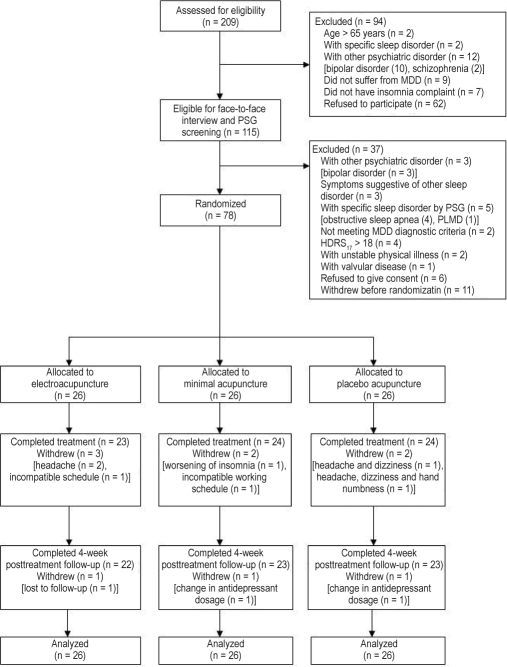

Two hundred nine potential subjects were assessed for eligibility; of whom 115 were screened in person and 78 subjects were randomized (Figure 1). Participants had a mean age of 48.1 years, and 79.5% were female (Table 1). Table 2 presents the history of depressive disorder of the subjects. Participants were diagnosed to have MDD for an average of 6.9 years, and the mean age of onset was 42.8 years. The majority (97.4%) were taking antidepressants, about half with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and 17.1% were using a combination of antidepressants. The mean ATHF score was 3.2; 80.8% of the sample scored ≥ 3, suggesting a history of pharmacotherapy failure. Thirty-two participants (41.0%) reported mixed sleep-onset and maintenance insomnia according to the ISI insomnia items' response of at least severe symptoms; 28 subjects (25.9%) reported only difficulties maintaining sleep; and 6 (7.7%) had only sleep-onset insomnia. Thirty-six subjects (46.2%) were taking hypnotics for sleep disturbances. There was no significant between-group difference in sociodemographic, clinical features, and pharmacotherapy. Seven subjects (9.0%) dropped out during treatment period, and 3 participants (3.8%) withdrew from study at 4 week follow-up (Figure 1). There was no difference in attrition rate among the groups at 1 week and 4 week follow-up (P > 0.05, Fisher exact test).

Figure 1.

Participant flowchart

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

| Variablesa | Electro- acupuncture (n = 26) | Minimal acupuncture (n = 26) | Placebo acupuncture (n = 26) | Total (n = 78) | χ2/ F valueb | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 47.5 ± 8.5 | 46.7 ± 9.7 | 50.1 ± 9.1 | 48.1 ± 9.1 | 0.95 | 0.39 |

| Sex, male/female | 6/20 | 7/19 | 3/23 | 16/62 | 2.04 | 0.36 |

| Education attainment, y | 13.7 ± 3.2 | 13.7 ± 2.8 | 12.0 ± 3.1 | 13.2 ± 3.1 | 2.64 | 0.08 |

| Marital status | 2.35 | 0.67 | ||||

| Never married | 3 (11.5) | 4 (15.4) | 6 (23.1) | 13 (16.7) | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 13 (50.0) | 15 (57.7) | 14 (53.8) | 42 (53.8) | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 10 (38.5) | 7 (26.9) | 6 (23.1) | 23 (29.5) | ||

| Occupation | 12.77 | 0.12 | ||||

| Professional and associate professional | 5 (19.2) | 7 (26.9) | 1 (3.8) | 13 (16.7) | ||

| Skilled and semi-skilled worker | 5 (19.2) | 3 (11.5) | 3 (11.5) | 11 (14.1) | ||

| Unskilled worker | 1 (3.8) | 5 (19.2) | 2 (7.7) | 8 (10.3) | ||

| Retired | 1 (3.8) | 3 (11.5) | 4 (15.4) | 8 (10.3) | ||

| Unemployed/housework | 14 (53.8) | 8 (30.8) | 16 (61.5) | 38 (48.7) | ||

| Insomnia duration, y | 8.9 ± 10.1 | 11.5 ± 9.4 | 12.6 ± 8.6 | 11.0 ± 9.4 | 1.06 | 0.35 |

| Previous treatment for insomnia | ||||||

| Western medication | 21 (80.8) | 25 (96.2) | 25 (96.2) | 71 (91.0) | 5.02 | 0.08 |

| Psychological treatment | 3 (11.5) | 7 (26.9) | 4 (15.4) | 14 (17.9) | 2.26 | 0.32 |

| OTC drug | 4 (15.4) | 5 (19.2) | 4 (15.4) | 13 (16.7) | 0.19 | 0.92 |

| Chinese herbal medicine | 9 (34.6) | 9 (34.6) | 12 (46.2) | 30 (38.5) | 0.98 | 0.61 |

| Othersc | 2 (7.7) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.1) | 2.11 | 0.35 |

| Coffee use ≥ 1 cup/d | 5 (19.2) | 4 (15.4) | 2 (7.7) | 11 (14.1) | 1.48 | 0.48 |

| Alcohol use ≥ 3 times/wk | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (2.6) | 1.03 | 0.60 |

| Chronic medical illnesses | 2 (7.7) | 6 (23.1) | 7 (26.9) | 15 (19.2) | 3.46 | 0.18 |

| ISI total score | 19.4 ± 3.3 | 18.6 ± 2.6 | 19.6 ± 3.4 | 19.2 ± 3.1 | 0.81 | 0.45 |

| PSQI total score | 13.7 ± 3.2 | 13.7 ± 2.5 | 14.1 ± 3.7 | 13.8 ± 3.1 | 0.16 | 0.86 |

| Polysomnography result | (n = 13) | (n = 12) | (n = 15) | (n = 40) | ||

| SOL, min | 43.9 ± 28.9 | 43.0 ± 33.9 | 65.5 ± 79.9 | 51.7 ± 54.7 | 0.76 | 0.48 |

| TST, min | 377.2 ± 44.7 | 395.2 ± 77.3 | 363.2 ± 79.4 | 377.3 ± 68.8 | 0.71 | 0.50 |

| WASO, min | 67.3 ± 43.4 | 57.4 ± 44.6 | 81.1 ± 47.5 | 69.5 ± 45.3 | 0.94 | 0.40 |

| SE, % | 77.2 ± 10.6 | 80.3 ± 15.9 | 73.3 ± 14.5 | 76.7 ± 13.8 | 0.88 | 0.42 |

ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; OTC, over-the-counter; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SE, sleep efficiency; SOL, sleep onset latency; TST, total sleep time; WASO, wake time after sleep onset.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

Comparison between electroacupuncture, minimal acupuncture, and placebo acupuncture by χ2 or ANOVA test.

Others including health and dietary products, massage, and hypnosis.

Table 2.

Psychiatric history of the sample

| Variablesa | Electro- acupuncture (n = 26) | Minimal acupuncture (n = 26) | Placebo acupuncture (n = 26) | Total (n = 78) | χ2/ F valueb | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset of depressionc, y | 43.2 ± 9.3 | 42.2 ± 10.3 | 43.1 ± 11.3 | 42.8 ± 10.2 | 0.73 | 0.93 |

| Depression duration, y | 5.6 ± 5.1 | 6.6 ± 6.6 | 8.6 ± 11.0 | 6.9 ± 8.0 | 0.96 | 0.39 |

| HDRS17 total score | 10.4 ± 3.9 | 11.2 ± 3.9 | 11.8 ± 3.9 | 11.1 ± 3.9 | 0.93 | 0.40 |

| Previous depressive episodec | 3.87 | 0.43 | ||||

| 1 | 18 (69.2) | 15 (57.7) | 13 (52.0) | 46 (59.7) | ||

| 2 | 8 (30.8) | 8 (30.8) | 9 (36.0) | 25 (32.5) | ||

| 3 or more | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.5) | 3 (12.0) | 6 (7.8) | ||

| Antidepressant treatment History form | ||||||

| Mean score | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 0.76 | 0.47 |

| Total score ≥ 3 | 22 (84.6) | 20 (76.9) | 21 (80.8) | 63 (80.8) | 0.50 | 0.78 |

| Current antidepressants | 24 (92.4) | 26 (100.0) | 26 (100.0) | 76 (97.4) | 4.11 | 0.13 |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 12 (46.2) | 9 (34.6) | 15 (57.7) | 36 (47.4) | 7.41 | 0.28 |

| Serotonin and noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors | 4 (15.4) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (11.5) | 8 (10.5) | ||

| Tricyclic antidepressants and others | 4 (15.4) | 10 (38.5) | 5 (19.2) | 19 (25.0) | ||

| Combination | 4 (15.4) | 6 (23.1) | 3 (11.5) | 13 (17.1) | ||

| Current hypnotics | 12 (46.2) | 13 (50.0) | 11 (42.3) | 36 (46.2) | 0.31 | 0.86 |

| Benzodiazepines | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (2.6) | 8.73 | 0.19 |

| Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics | 9 (34.6) | 11 (42.3) | 4 (15.4) | 24 (30.8) | ||

| Combination of benzodiazepines and non- benzodiazepine hypnotics | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (15.4) | 6 (7.7) | ||

| Antihistamine | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (5.1) | ||

| Equivalent dose of hypnotics in mg diazepam/d | 7.9 ± 9.6 | 5.2 ± 3.6 | 9.6 ± 6.9 | 7.5 ± 7.1 | 1.17 | 0.33 |

| Anxiolytics | 1 (3.8) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (15.4) | 7 (9.0) | 2.20 | 0.33 |

| Antipsychotics, lithium, and anticonvulsants | 0 (0.0) | 5 (19.2) | 2 (7.7) | 7 (9.0) | 5.96 | 0.05 |

HDRS17, 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

Comparison between electroacupuncture, minimal acupuncture, and placebo acupuncture by χ2 or ANOVA test.

One missing data in placebo acupuncture group.

Efficacy

Subjective measure

Table 3 presents ISI and PSQI data for electroacupuncture, minimal acupuncture, and placebo acupuncture groups. Mixed-effects model analysis showed that subjects in electroacupuncture and minimal acupuncture groups had significantly greater reduction in ISI and PSQI scores than those in placebo acupuncture group at 1 week and 4 week post-treatment; however, there was no significant difference between electroacupuncture and minimal acupuncture at both time points.

Table 3.

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores across study time points

| Electroacupuncture |

Minimal acupuncture |

Placebo acupuncture |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Within-group effect size | Mean ± SD | Within-group effect size | Mean ± SD | Within-group effect size | P-valuea | |

| ISI | 0.04 | ||||||

| Baseline | 19.4 ± 3.3 | 18.6 ± 2.6 | 19.6 ± 3.4 | ||||

| 1 week post-treatment | 13.6 ± 4.2 | 1.54 | 14.3 ± 5.4 | 1.01 | 17.5 ± 5.6 | 0.45 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 14.2 ± 6.0 | 1.07 | 14.0 ± 4.2 | 1.32 | 17.1 ± 5.3 | 0.56 | |

| PSQI | 0.03 | ||||||

| Baseline | 13.7 ± 3.2 | 13.7 ± 2.5 | 14.1 ± 3.7 | ||||

| 1 week post-treatment | 12.0 ± 3.0 | 0.55 | 11.2 ± 3.4 | 0.84 | 14.2 ± 3.5 | 0.03 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 12.0 ± 3.8 | 0.48 | 11.9 ± 3.4 | 0.60 | 14.0 ± 4.1 | 0.03 | |

| Electroacupuncture vs. Placebo acupuncture |

Electroacupuncture vs. Minimal acupuncture |

Minimal acupuncture vs. Placebo acupuncture |

|||||

| P-valueb | Between-group effect size | P-valueb | Between-group effect size | P-valueb | Between-group effect size | ||

| ISI | |||||||

| Baseline | |||||||

| 1 week post-treatment | 0.003 | 0.79 | 0.56 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.58 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.92 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.65 | |

| PSQI | |||||||

| Baseline | |||||||

| 1 week post-treatment | 0.02 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.002 | 0.87 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.99 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.56 | |

P-value for group by time interaction using linear mixed-effects models.

Post hoc pairwise comparison for significant mixed-effects models.

Subjects in minimal acupuncture group had significantly higher sleep diary-derived SE at 1 week post-treatment than those receiving placebo acupuncture, but there was no significant difference between electroacupuncture and placebo acupuncture, and electroacupuncture and minimal acupuncture (Table 4). The between-group difference in sleep diary-derived SE was nonsignificant at 4 week post-treatment (post hoc pairwise comparisons, all P > 0.05). There was no significant between-group difference in sleep diary-derived SOL, TST, WASO, and sleep quality, and daily dosage of hypnotics at 1 week and 4 week post-treatment.

Table 4.

Sleep diary measures across study time points

| Sleep diary | Electroacupuncture |

Minimal acupuncture |

Placebo acupuncture |

P-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Within-group effect size | Mean ± SD | Within-group effect size | Mean ± SD | Within-group effect size | ||

| SOL, min | 0.61 | ||||||

| Baseline | 56.6 ± 57.6 | 45.7 ± 40.3 | 70.9 ± 58.3 | ||||

| 1 week post-treatment | 54.0 ± 63.8 | 0.04 | 35.2 ± 26.9 | 0.31 | 74.2 ± 55.4 | -0.06 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 53.4 ± 68.0 | 0.05 | 34.8 ± 19.0 | 0.35 | 64.9 ± 53.1 | 0.11 | |

| TST, min | 0.81 | ||||||

| Baseline | 326.0 ± 102.6 | 323.2 ± 108.1 | 329.1 ± 91.0 | ||||

| 1 week post-treatment | 344.1 ± 82.4 | 0.19 | 338.3 ± 99.8 | 0.15 | 311.0 ± 68.8 | -0.22 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 335.3 ± 77.0 | 0.10 | 330.5 ± 90.9 | 0.07 | 316.2 ± 95.1 | -0.14 | |

| WASO, min | 0.13 | ||||||

| Baseline | 75.4 ± 73.1 | 84.4 ± 80.4 | 102.7 ± 85.0 | ||||

| 1 week post-treatment | 67.0 ± 77.9 | 0.11 | 68.7 ± 94.2 | 0.18 | 111.4 ± 85.0 | -0.10 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 53.9 ± 60.4 | 0.32 | 69.9 ± 82.9 | 0.18 | 92.7 ± 66.7 | 0.13 | |

| SE, % | 0.01b | ||||||

| Baseline | 69.1 ± 16.7 | 68.3 ± 20.3 | 68.9 ± 19.8 | ||||

| 1 week post-treatment | 72.3 ± 17.4 | 0.19 | 75.6 ± 20.8 | 0.36 | 64.4 ± 17.1 | -0.24 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 72.9 ± 16.2 | 0.23 | 74.4 ± 18.2 | 0.32 | 68.4 ± 18.5 | -0.03 | |

| Sleep qualityc | 0.10 | ||||||

| Baseline | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | ||||

| 1 week post-treatment | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 0.18 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 0.00 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | -0.17 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 0.18 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 0.40 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | -0.31 | |

| Equivalent dose of hypnotics in mg diazepam/d mg/d | 0.99 | ||||||

| Baseline | 7.9 ± 9.6 | 5.2 ± 3.6 | 9.6 ± 6.9 | ||||

| 1 week post-treatment | 7.9 ± 9.7 | 0.00 | 4.8 ± 4.0 | 0.11 | 9.5 ± 7.7 | 0.01 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 8.1 ± 10.3 | -0.02 | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 0.56 | 9.7 ± 7.0 | -0.01 | |

SE, sleep efficiency; SOL, sleep onset latency; TST, total sleep time; WASO, wake time after sleep onset.

P-value for group by time interaction using linear mixed-effects models.

Post hoc pairwise comparison: 1 week post-treatment, electroacupuncture vs. placebo acupuncture, P = 0.13; minimal acupuncture vs. placebo acupuncture, P = 0.03; electroacupuncture vs. minimal acupuncture, P = 0.53; and 4 week post-treatment, all P > 0.05.

A lower score represents better sleep quality.

The linear mixed-effects analyses including insomnia subtype (mixed vs. others) and baseline depression severity (HRSD17 total score > 10 vs. ≤ 10) did not show significant group, time, and insomnia subtype or group, time, and depression severity interactions for ISI, PSQI, and all sleep-diary measures.

Objective measures and other clinical variables

Table 5 presents the actigraphy data. Mixed-effects model analysis showed that there was no significant between-group difference in actigraphy-derived SOL, TST, WASO, and SE at 1 week and 4 week post-treatment, as well as no difference in HRSD17 total score, HRSD17 insomnia items score, and SDS scores (Table 6). In addition, there was no significant group difference in CTRS scores after the 2nd and 9th acupuncture treatment (Mixed-effects models, all P > 0.05, data not presented).

Table 5.

Actigraphy measures across study time points

| Actigraphy | Electroacupuncture |

Minimal acupuncture |

Placebo acupuncture |

P-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Within-group effect size | Mean ± SD | Within-group effect size | Mean ± SD | Within-group effect size | ||

| SOL, min | |||||||

| Baseline | 27.6 ± 19.3 | 38.6 ± 34.1 | 41.6 ± 45.2 | 0.12 | |||

| 1 week post-treatment | 32.3 ± 39.0 | -0.15 | 28.3 ± 31.9 | 0.31 | 31.7 ± 31.7 | 0.25 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 23.1 ± 18.3 | 0.21 | 23.4 ± 17.8 | 0.56 | 42.4 ± 44.3 | 0.02 | |

| TST, min | |||||||

| Baseline | 409.2 ± 79.5 | 403.1 ± 91.6 | 426.3 ± 106.7 | 0.11 | |||

| 1 week post-treatment | 386.3 ± 79.2 | -0.29 | 407.0 ± 94.5 | 0.04 | 425.8 ± 94.3 | 0.00 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 417.3 ± 94.7 | 0.09 | 412.9 ± 74.2 | 0.12 | 399.0 ± 89.6 | -0.28 | |

| WASO, min | |||||||

| Baseline | 31.1 ± 19.3 | 19.5 ± 11.8 | 44.6 ± 51.6 | 0.05 | |||

| 1 week post-treatment | 26.4 ± 20.6 | 0.24 | 19.2 ± 14.0 | 0.02 | 41.6 ± 63.2 | 0.05 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 22.9 ± 13.6 | 0.49 | 21.5 ± 15.6 | -0.14 | 26.4 ± 29.1 | 0.43 | |

| SE, % | |||||||

| Baseline | 87.1 ± 6.2 | 87.5 ± 8.0 | 82.5 ± 13.8 | 0.38 | |||

| 1 week post-treatment | 86.8 ± 9.5 | -0.04 | 89.9 ± 7.6 | 0.31 | 85.4 ± 13.5 | 0.21 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 89.8 ± 6.2 | 0.44 | 90.6 ± 5.0 | 0.46 | 85.1 ± 12.7 | 0.20 | |

SE, sleep efficiency; SOL, sleep onset latency; TST, total sleep time; WASO, wake time after sleep onset.

P-value for group by time interaction using linear mixed-effects models.

Table 6.

17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS17) and Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) scores across study time points

| Electro-acupuncture Mean ± SD | Minimal acupuncture Mean ± SD | Placebo acupuncture Mean ± SD | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDRS17-total | 0.25 | |||

| Baseline | 10.4 ± 3.9 | 11.2 ± 3.9 | 11.8 ± 3.9 | |

| 1 week post-treatment | 9.9 ± 4.5 | 9.7 ± 2.6 | 11.9 ± 5.3 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 9.6 ± 5.1 | 9.0 ± 3.8 | 11.1 ± 5.3 | |

| HDRS17-insomnia | 0.59 | |||

| Baseline | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | |

| 1 week post-treatment | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 2.9 ± 1.4 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | |

| SDS | ||||

| Work | 0.42 | |||

| Baseline | 4.6 ± 3.6 | 5.1 ± 2.3 | 5.7 ± 3.4 | |

| 1 week post-treatment | 3.5 ± 3.0 | 4.4 ± 2.7 | 4.4 ± 3.8 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 3.8 ± 2.8 | 4.0 ± 2.7 | 5.3 ± 3.5 | |

| Social | 0.53 | |||

| Baseline | 5.6 ± 2.8 | 4.5 ± 2.3 | 5.9 ± 2.6 | |

| 1 week post-treatment | 4.1 ± 2.9 | 4.2 ± 2.4 | 5.7 ± 3.1 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 4.2 ± 2.9 | 3.4 ± 2.8 | 5.4 ± 3.3 | |

| Family | 0.18 | |||

| Baseline | 5.6 ± 2.9 | 4.8 ± 2.6 | 6.0 ± 2.1 | |

| 1 week post-treatment | 3.4 ± 2.7 | 4.3 ± 2.7 | 5.7 ± 3.3 | |

| 4 week post-treatment | 3.9 ± 2.9 | 3.7 ± 2.7 | 5.8 ± 3.3 |

P-value for group by time interaction using linear mixed-effects models.

Adverse Events

Two subjects in electroacupuncture group reported headache as an adverse event and one complained of dizziness. In minimal acupuncture group, worsening of insomnia (n = 1), hand numbness (n = 2), hematoma (n = 1), palpitation (n = 1), and pain at acupoints (n = 1) were reported; for placebo acupuncture group, adverse events included headache (n = 2), dizziness (n = 2), and hand numbness (n = 1). Most adverse events were mild in severity.

DISCUSSION

Compared with noninvasive placebo acupuncture, electroacupuncture, and minimal acupuncture showed statistically significant improvement in self-report measures of insomnia; however, there was no significant difference in depressive symptoms, daily functioning, hypnotic use, or objective sleep based on actigraphy among the 3 groups. In terms of safety and treatment compliance, the 3 week thrice-weekly course of acupuncture was well tolerated and accepted by most participants.

The hypnotic efficacy of electroacupuncture was observed at both 1 week and 4 week post-treatment, based on the reduction in ISI and PSQI scores. At 4 week post-treatment, the mean PSQI score in electroacupuncture group was 12.0, which remained considerably higher than the cut-off of 5 used for normal sleep. The mean ISI score and sleep diary-derived SE at 4 weeks after treatment were 14.2% and 72.9%, respectively, indicating that the subjects were still suffering from moderate insomnia. We are uncertain whether increasing session frequency and treatment duration can enhance efficacy and sustain improvement. The acupuncture treatment in this study had no significant impact on depressive symptoms and psychosocial functioning, perhaps due to the slight improvement in sleep and that the acupuncture regimen was targeted mainly at insomnia. It would be worthwhile to explore whether improved regimens targeted at both insomnia and depression could enhance the efficacy of acupuncture on residual insomnia associated with MDD.40

Compared with our findings in primary insomnia,22 the hypnotic efficacy of placebo acupuncture in MDD patients with residual insomnia was much smaller; while the effects of electroacupuncture were similar. The within-group effect sizes for subjective sleep measures, (ISI and PSQI) from baseline to 1 week post-treatment with placebo acupuncture were 0.45 and 0.03, respectively, in MDD patients; for electroacupuncture: 1.54 and 0.55, respectively. In primary insomniac subjects, the respective effect sizes for placebo acupuncture were 1.18 and 0.93; for electroacupuncture, they were 1.33 and 0.70, respectively.22 It was possible that MDD patients with residual insomnia had poor response to previous trials of pharmacotherapy; hence their insomnia was less likely to respond to placebo treatment; whereas in community sample of primary insomnia, some participants had not received any treatment before and responded to nonspecific therapeutic effects of placebo acupuncture.

In this study of residual insomnia associated with MDD, we showed that minimal acupuncture and electroacupuncture had similar hypnotic efficacy. The result is contrary to the TCM theory, which emphasizes the importance of specific acupoints, deep needling and deqi sensation. Previous studies in other conditions, such as migraine, osteoarthritis, and low back pain have found that superficial needling at non-acupoints and acupuncture according to the TCM theory possess similar efficacy.41,42 Our findings suggest that the importance of precise acupoint needling, depth of needling, and deqi sensation needs to be reconsidered.

The major limitation of our study is the clinical heterogeneity of our sample. We investigated the effect of acupuncture on relatively unselected “real-world” MDD patients with residual insomnia. Although 81% of the subjects met research criteria for pharmacological treatment resistance, some patients had not given multiple steps of antidepressant treatment, sedative antidepressants, psychological treatment, and adjunctive medications for sleep, perhaps due to personal preference or intolerable side effects. The participants might have high expectations in the effectiveness of acupuncture, which may lead to an overinflated response. However, the limited hypnotic efficacy in placebo acupuncture group suggests that the nonspecific treatment factors of acupuncture are not high. Although we have not examined the success of blinding, it is reassuring that there was no significant difference in the patients' confidence toward treatment as assessed by the CTRS. In line with usual clinical practice, the subjects were allowed to reduce the use of hypnotics, and the dosage of hypnotics was used as an outcome variable. Although there was no significant difference in the dosage of benzodiazepine among treatment groups, benzodiazepine reduction and the associated withdrawal symptoms could be a confounding factor. Another limitation is that only half of the randomized subjects agreed to receive laboratory-based sleep study. The subjects were examined using a semi-structured interview for insomnia; however, we could not be certain that all subjects were free from specific sleep disorders. Lastly, our sample size was calculated to test the statistical difference between electroacupuncture and placebo acupuncture, therefore, it was underpowered to examine the differences between electroacupuncture and minimal acupuncture and the effect of subgroups on treatment response.

Despite these limitations, the present study provides important data on the management of residual insomnia in MDD. We found a slight advantage of electroacupuncture and minimal acupuncture over noninvasive placebo acupuncture as an additional treatment for residual insomnia associated with MDD. No significant difference was observed between electroacupuncture and minimal acupuncture, suggesting that the differences may be due to general physiological effects of needling and electrostimulation and that the emphasis placed on acupuncture points according to TCM principles may be overstated. Because of the limited hypnotic efficacy and absence of beneficial effects on depressive symptoms and daily functioning, the utility of acupuncture is still uncertain. Further studies with improved acupuncture regimens are warranted to accurately determine the use of acupuncture for the treatment of residual insomnia in MDD.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paykel ES. Partial remission, residual symptoms, and relapse in depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10:431–7. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/espaykel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:221–5. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nierenberg AA, Husain MM, Trivedi MH, et al. Residual symptoms after remission of major depressive disorder with citalopram and risk of relapse: a STAR*D report. Psychol Med. 2010;40:41–50. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709006011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carney CE, Segal ZV, Edinger JD, et al. A comparison of rates of residual insomnia symptoms following pharmacotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:254–60. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pigeon WR, Hegel M, Unutzer J, et al. Is insomnia a perpetuating factor for late-life depression in the IMPACT cohort? Sleep. 2008;31:481–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dombrovski AY, Cyranowski JM, Mulsant BH, et al. Which symptoms predict recurrence of depression in women treated with maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy? Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:1060–6. doi: 10.1002/da.20467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fava M, McCall WV, Krystal A, et al. Eszopiclone co-administered with fluoxetine in patients with insomnia coexisting with major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1052–60. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, San Pedro-Salcedo MG, Kuo TF, Kalista T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31:489–95. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolen WA, Haffmans PM, Bouvy PF, Duivenvoorden HJ. Hypnotics as concurrent medication in depression. A placebo-controlled, double-blind comparison of flunitrazepam and lormetazepam in patients with major depression, treated with a (tri)cyclic antidepressant. J Affect Disord. 1993;28:179–88. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90103-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asnis GM, Chakraburtty A, DuBoff EA, et al. Zolpidem for persistent insomnia in SSRI-treated depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:668–76. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nierenberg AA, Adler LA, Peselow E, Zornberg G, Rosenthal M. Trazodone for antidepressant-associated insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1069–72. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference Statement on manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adults, June 13-15, 2005. Sleep. 2005;28:1049–57. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krystal AD. The changing perspective on chronic insomnia management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 8):20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang WC. The psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework: application to Asian Americans. Am Psychol. 2006;61:702–15. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeung WF, Chung KF, Leung YK, Zhang SP, Law AC. Traditional needle acupuncture treatment for insomnia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med. 2009;10:694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacPherson H, White A, Cummings M, Jobst K, Rose K, Niemtzow R. Standards for reporting interventions in controlled trials of acupuncture: The STRICTA recommendations. Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trails of Acupuncture. Acupunct Med. 2002;20:22–5. doi: 10.1136/aim.20.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morin CM, Espie CA. Insomnia: a clinical guide to assessment and treatment. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system of sleep stages in human subjects. Los Angeles: UCLA Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute, ; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon S. A simple approach for randomisation. 1999. Retrieved 10 Jul 2010. from http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/eletters/319/7211/703.

- 22.Yeung WF, Chung KF, Zhang SP, Law AC, Yap TG. Electroacupuncture for primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial Sleep. 2009;32:1039–47. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.8.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melchart D, Streng A, Hoppe A, et al. Acupuncture in patients with tension-type headache: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;331:376–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38512.405440.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Streitberger K, Kleinhenz J. Introducing a placebo needle into acupuncture research. Lancet. 1998;352:364–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spielman A, Glovinsky P. Understanding sleep: The evaluation and treatment of sleep disorders. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association Press; 1997. The diagnostic interview and differential diagnosis for complaints of insomnia. In: Pressman M, Orr W, eds; pp. 125–160. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashton CH. Benzodiazepine equivalence table. 2007. Retrieved 10 Jul 2010. from http://benzo.org.uk/bzequiv.htm.

- 29.Littner M, Kushida CA, Anderson WM, et al. Practice parameters for the role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms: an update for 2002. Sleep. 2003;26:337–41. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Decina P, Kerr B, Malitz S. The impact of medication resistance and continuation pharmacotherapy on relapse following response to electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10:96–104. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prudic J, Haskett RF, Mulsant B, et al. Resistance to antidepressant medications and short-term clinical response to ECT. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:985–92. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27:93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vincent C. Credibility assessment in trials of acupuncture. Complement Med Res. 1990;4:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung KF, Tang MK. Subjective sleep disturbance and its correlates in middle-aged Hong Kong Chinese women. Maturitas. 2006;53:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sperber A. Translation and validation of study instruments for cross-cultural research. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(1) Suppl 1:S124–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sperber A, DeVellis R, Boehlecke B. Cross-cultural translation: methodology and validation. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 1994;25:501–24. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–9. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borm GF, Fransen J, Lemmens WA. A simple sample size formula for analysis of covariance in randomized clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:1234–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang ZJ, Chen HY, Yip KC, Ng R, Wong VT. The effectiveness and safety of acupuncture therapy in depressive disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2010;124:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundeberg T, Lund I, Sing A, Naslund J. Is placebo acupuncture what it is intended to be? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep049. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moffet HH. Sham acupuncture may be as efficacious as true acupuncture: a systematic review of clinical trials. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:213–6. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]