Abstract

Atrogin1/MAFbx is an ubiquitin ligase that mediates muscle atrophy in a variety of catabolic states. We recently found that H2O2 stimulates atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression. Since the cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) stimulates both reactive oxygen production and general activity of the ubiquitin conjugating pathway, we hypothesized that TNF-α would also increase atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression. As with H2O2, we found that TNF-α exposure up-regulates atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA within 2 h in C2C12 myotubes. Intraperitoneal injection of TNF-α increased atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA in skeletal muscle of adult mice within 4 h. Exposing myotubes to either TNF-α or H2O2 also produced general activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs): p38, ERK1/2, and JNK The increase in atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression induced by TNF-α was not altered significantly by ERK inhibitor PD98059 or the JNK inhibitor SP600125. In contrast, atrogin1/MAFbx up-regulation and the associated increase in ubiquitin conjugating activity were both blunted by p38 inhibitors, either SB203580 or curcumin. These data suggest that TNF-α acts via p38 to increase atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression in skeletal muscle.

Keywords: tumor necrosis factor, muscle wasting, ubituitin conjugating activity

Muscle wasting is a debilitating complication of cancer, AIDS, and other chronic inflammatory diseases. Loss of muscle mass results primarily from accelerated protein degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (1). Proteins degraded by this mechanism are first covalently linked to a chain of ubiquitin molecules, which marks them for rapid breakdown by the 26S proteasome (2). The selectivity of ubiquitin targeting to protein substrates is primarily a function of ubiquitin ligases (E3 proteins), a family of enzymes that catalyze the transfer of activated ubiquitin from a specific ubiquitin carrier (E2) protein to a lysine residue on the substrate.

In skeletal muscle, three E3 proteins are known to regulate ubiquitin conjugation in catabolic states: E3α, atrogin1/MAFbx, and MuRF1. E3α interacts with E214k to attach ubiquitin to protein substrates according to the “N-end rule” (3). Atrogin1/MAFbx and MuRF1 are up-regulated and appear to be essential for accelerated muscle protein loss in a variety of experimental models of catabolism. These include fasting, diabetes, cancer, renal failure, hindlimb suspension, immobilization, denervation, sepsis, and lipopolysaccharide administration (4–8). Because the atrogin1/MAFbx and MuRF1 genes respond to such diverse catabolic conditions, it is important to determine the cellular mechanisms that regulate expression of these genes.

In studies of atrogin1/MAFbx regulation, we recently found that mRNA levels are increased by exposing muscle cells to exogenous H2O2 (9). Skeletal muscle myocytes continuously generate H2O2 and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) that function as intracellular signaling molecules (10). ROS production (11, 12) and ROS-mediated signaling (13, 14) are stimulated by tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a catabolic cytokine (15) that increases general activity of the ubiquitin conjugating pathway (16–18). Therefore, as observed for H2O2, we hypothesized that TNF-α would up-regulate atrogin1/MAFbx expression in skeletal muscle. The present study tested this hypothesis, measuring changes in mRNA levels and ubiquitin conjugating activity in muscle cells stimulated by TNF-α. Our approach incorporated several experimental preparations including differentiated myotubes, excised muscles, and TNF-α-treated mice. Responses to TNF-α were compared with those elicited by H2O2, a positive control.

We evaluated mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) as potential second messengers for TNF-α. Data from nonmuscle cell types indicate that TNF-α and H2O2 activate MAPKs, including p38, ERK1/2, and JNK (13). p38 MAPK has been identified as a potential regulator of muscle catabolism (19). Recent studies show that p38 activity in skeletal muscle is elevated by procatabolic states, which include limb immobilization (20), acute quadriplegic myopathy (21), Type 2 diabetes (22), neurogenic atrophy (21), and aging (23). To test p38 MAPK involvement in atrogin1/MAFbx regulation, we measured TNF-α effects on total and phosphorylated enzyme levels in muscle and tested the effects of p38 MAPK inhibitors on TNF-α-stimulated atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression. Control studies screened ERK1/2 and JNK for similar involvement.

Our results suggest the atrogin1/MAFbx gene product is up-regulated in response to TNF-α, an event that precedes the rise in general ubiquitin conjugating activity. Atrogin1/MAFbx up-regulation in response to either TNF-α or H2O2 is associated with activation of p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, and JNK. The former appears to be essential for atrogin1/MAFbx up-regulation since p38 inhibitors block increases in gene expression and ubiquitin conjugating activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Myocyte responses to TNF-α were tested using several complementary preparations. Primary studies of postreceptor signaling events and atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression were conducted using differentiated C2C12 mytubes. Physiological relevance was assessed using excised mouse diaphragm preparations challenged with recombinant TNF-α in vitro or limb muscles of mice that were preinjected with TNF-α. Details of these preparations are outlined below.

Myogenic cell cultures

Myotubes were cultured from the murine skeletal muscle-derived C2C12 myoblast line (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) as described previously (24). Briefly, C2C12 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and gentamicin at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. Myoblast differentiation was initiated by replacing the growth medium with differentiation medium: DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum. Differentiation was allowed to continue for 96 h before experimentation (changing to fresh medium at 48 h). Recombinant murine TNF-α (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was added to differentiation medium for incubation with myotubes as indicated. H2O2 (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA) was incubated with myotubes in DMEM supplemented with 0.5% horse serum.

Animal use

Experimental protocols were approved in advance by the Animal Protocol Review Committee of the Baylor Animal Program. Adult C57 mice (8-wk-old) were injected intraperitoneally (IP) with 100 ng/g body weight of recombinant murine TNF-α (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) or with an equal volume of diluent. At indicated times, animals were deeply anesthetized by IP injection of pentobarbital sodium 85 mg/kg and gastrocnemius muscles were surgically removed for Northern blot analysis. In separate studies, the diaphragm muscle was excised from anesthetized mice that had not been conditioned. Muscles then were directly exposed to TNF-α by incubation in vitro.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was isolated from rat or C2C12 myotubes by using the RNAzol reagent (TEL TEST, Friendswood, TX, USA). Twelve µg of each sample was isolated by agarose gel electrophoresis as modified from the procedure described by Liu and Chou (25). Briefly, RNA samples were denatured by heating to 65°C for 3 min in a sample loading buffer containing 1× TBE, 6.5% ficoll, 0.005% bromphenol blue, 0.025% xylkene cyanol ff, and 3.5 M urea (final concentrations). Samples were immediately chilled on ice and separated with 1% native agarose gel at 8 V/cm. RNA was blotted and UV cross-linked to GeneScreen membrane (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA, USA). Prehybridization (4 h) and hybridization (16 h) were carried out in ULTRAhyb buffer (Austin, TX, USA) at 42°C. The hybridization probe for the atrogin1/MAFbx gene was the full-length human coding sequence prepared from isolated total RNA using a one-step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol, Amersham Pharmacia, Arlington Heights, IL, USA) using the random primer method. After hybridization, the membranes were washed and exposed to X-ray films. Levels of mRNA were quantified by analyzing autoradiographs using densitometry software (ImageQuant 5.2, Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA); the optical density of each band was normalized using the corresponding 18S signal.

Western blot analysis

Protein content of each sample was determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Lysates of C2C12 myotubes (80 µg protein/lane) or protein extracts made from the heart (40 µg), diaphragm (40 µg), and gastrocnemius (80 µg) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After incubation with a blocking buffer, the membranes were incubated with anti-phospho-ERK1/2, anti-phospho-p38, anti-phospho-JNK, anti-ERK1/2, anti-p38, or anti-JNK (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used to locate the primary antibodies by the enhanced chemiluminescence method. Bands detected on the X-ray films were quantified using densitometry software (ImageQuant). Differences between experimental conditions were limited to comparisons within a given muscle type: myotubes, diaphragm, or gastrocnemius.

Ubiquitin conjugation assay

Whole cell extracts of C2C12 myotubes were made by three freeze-thaw cycles followed by 30 min incubation at 4°C in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 25% glycerol, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF, 1 µg/mL leupeptin, and 2 µg/mL aprotinin. Extracts were dialyzed against a buffer containing Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 1 mM DTT, and 10% glycerol. Protein was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. 125I-Ubiquitin was prepared by iodination of ubiquitin (Sigma) with carrier free sodium 125I (Amersham Pharmacia). Dialyzed extracts (~100 µg protein) were incubated with 125I-Ub (~100,000 cpm) in a buffer containing 20 mM Tri-HCl, pH 7.6, 20 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 30 µM MG-132 (to inhibit proteasome activity), 1 µM ubiquitin aldehyde (to inhibit the hydrolysis of ubiquitin conjugates by deubiquitinating isopeptidases), and 2 mM AMPPNP. AMPPNP is an ATP analog that provides energy for activation of ubiquitin by E1 but not for degradation of ubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome (26). The reaction mixtures (20 µL total volume) were incubated at 37°C for 60 min, after which the reaction was terminated by addition of 20 µL of 2× Laemmli sample buffer (27). The mixture was heated to 90°C for 3 min and separated on SDS-PAGE (15% gel). To quantify ubiquitin conjugating activity, autoradiographs of the gel were analyzed using densitometry software (ImageQuant).

Statistics

Commercial software (SigmaStat, SPSS Science, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyze data. Student’s t test was used for individual comparisons. Multiple comparisons were assessed by 1-way ANOVA or regression analysis. Differences between groups were considered significant at the P < 0.05 level. Values are reported as means ± se.

RESULTS

TNF-α up-regulates atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression in muscle

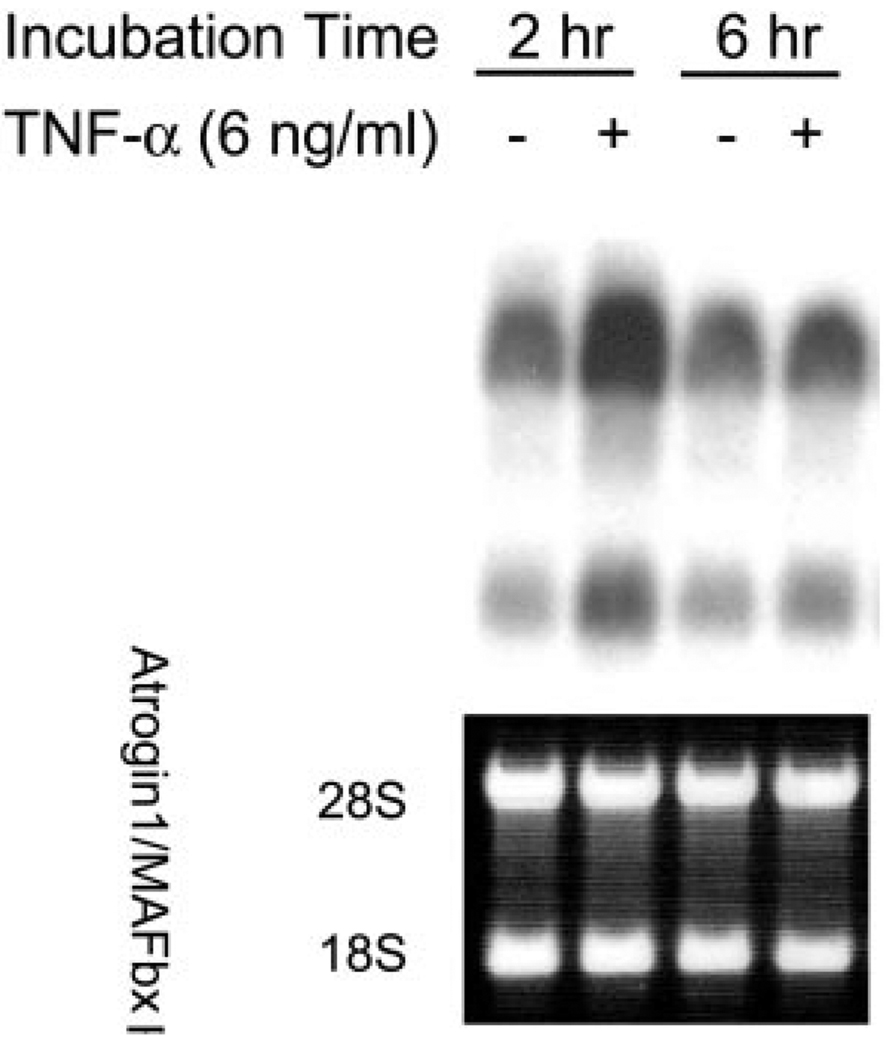

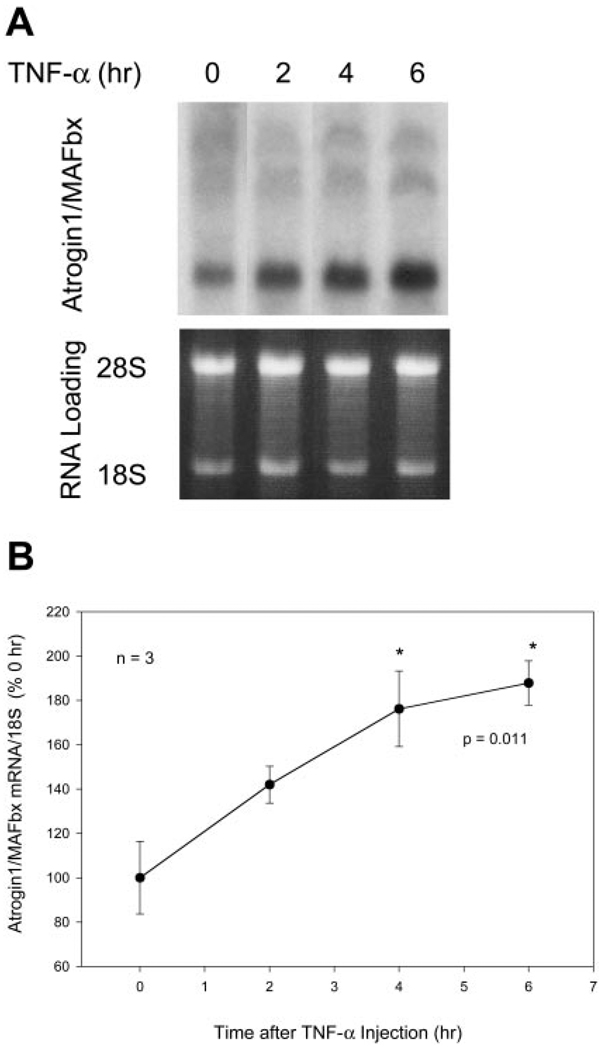

TNF-α effects on atrogin1/MAFbx expression were tested by Northern blot analyses. Using a full-length cDNA probe, we observed that differentiated C2C12 myotubes constitutively express atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA (Fig. 1). We detected multiple transcripts as reported by Gomes et al. (5); these ranged from ~6.5 to ~2.4 kb. Myotubes were analyzed after incubation with recombinant murine TNF-α 6 ng/mL, a concentration shown to induce myotube protein loss (24). Atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA levels increased 96.3 ± 21.1% (P<0.01, n=11) after 2 h, then returned to control level at 6 h (Fig. 1), remaining unchanged at 12 and 24 h (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 2, constitutive expression of atrogin1/ MAFbx mRNA was also detected in gastrocnemius muscles of adult mice. The sizes of transcripts detected in mouse muscle are similar to those seen in C2C12 myotubes, although the relative abundance of individual transcripts differs. Intraperitoneal injection of TNF-α 100 ng/g increased atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA content by 76.2 ± 17.1% after 4 h (P<0.05, n=3) and 87.7 ± 10.1% after 6 h (P<0.05, n=3), a prolonged response relative to the transient up-regulation seen in myotubes (Fig. 1). This sustained elevation may reflect time-dependent absorption and delivery of the cytokine, in vivo amplification of the original TNF-α stimulus, or both.

Figure 1.

TNF-α up-regulates atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression in C2C12 myotubes. C2C12 myotubes were incubated with TNF-α or vehicle. Total RNA was extracted and analyzed by Northern blot using a full-length human atrogin1/MAFbx cDNA probe. Representative blot depicts multiple atrogin/ MADbx transcripts (upper band ~6.5 kb, lower band ~2.4 kb). Both increased 2 h after TNF-α exposure and returned to basal levels by 6 h. Ethidium bromide-stained 28S and 18S rRNA are shown as loading controls.

Figure 2.

TNF-α up-regulates atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression in mouse gastrocnemius. Mice were IP injected with TNF-α 100 ng/g and gastrocnemius was surgically removed for analysis of the atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA A) A representative Northern blot with multiple transcripts (~6.5, 5, and 2.4 kb) and the loading control are shown. B) Bands representing the atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA were quantified by densitometry and normalized to 18S. Data from 3 mice in each time group were analyzed by ANOVA combined with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. *A difference (P<0.05) from control (0 h).

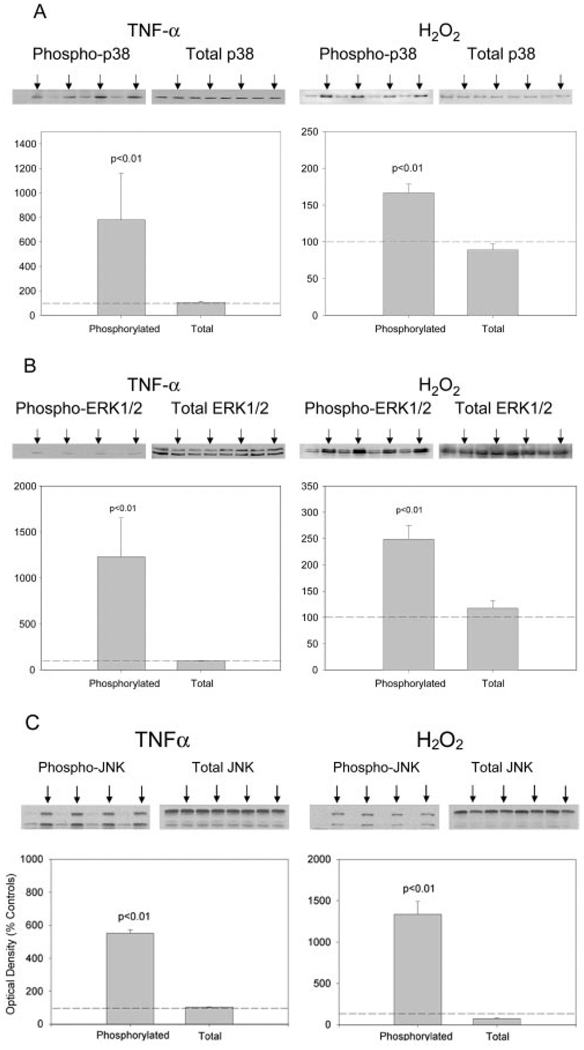

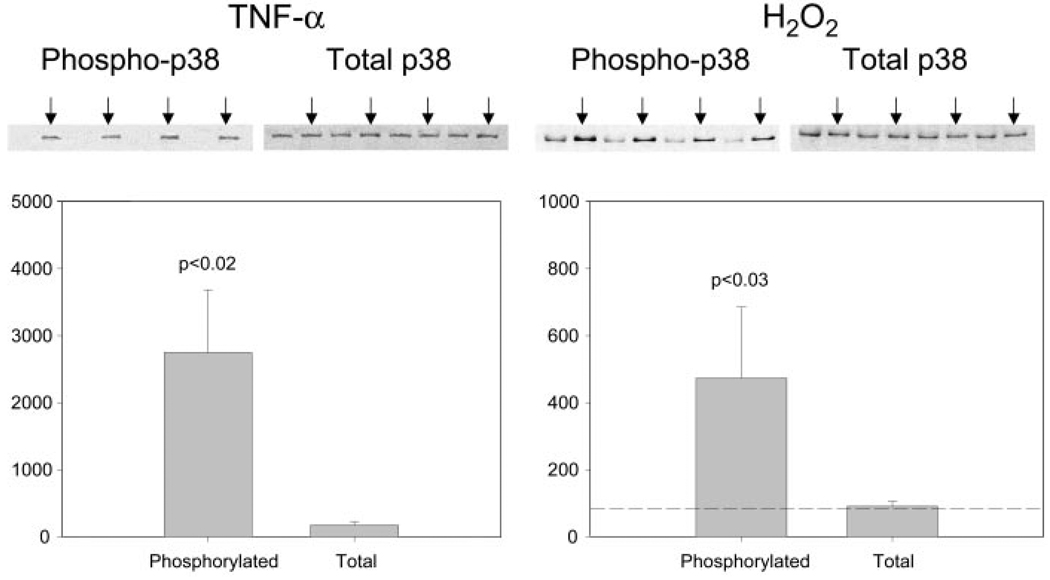

TNF-α stimulates MAPK phosphorylation

To elucidate signaling events by which TNF-α might regulate atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression, we systematically examined TNF-α effects on MAPK activity in differentiated C2C12 myotubes. Western blot analysis using phosphospecific antibodies was used to assess enzyme activation. As shown in Fig. 3A, phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was increased within 30 min of exposing myotubes to TNF-α 6 ng/mL but total p38 content was unaltered. H2O2 300 µM, another stimulus known to up-regulate atrogin1/MAFbx (9), had similar effects on p38 activity. Exposing myotubes to TNF-α or H2O2 increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 3B) and JNK (Fig. 3C) without altering total enzyme levels. The p38 MAPK responses measured in cultured myotubes were replicated using skeletal muscle preparations isolated from adult mice. As shown in Fig. 4, in vitro exposure of isolated hemidiaphragms to TNF-α 500 ng/mL stimulated an increase in p38 phosphorylation relative to data obtained from contralateral hemidiaphragms incubated in buffer alone. Direct exposure of isolated hemidiaphragms to H2O2 300 µM had similar effects, stimulating p38 phosphorylation without altering total enzyme content. Control experiments confirmed that ERK1/2 phosphorylation was increased by exposing isolated hemidiaphragms to either TNF-α or H2O2 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

TNF-α and H2O2 increase MAPK activity in C2C12 myotubes. C2C12 myotubes were incubated 30 min with TNF-α 6 ng/mL, H2O2 300 µM, or vehicle (control). Cell lysates were analyzed with Western blot using an antibody against the phosphorylated form of p38, ERK1/2, or JNK, and an antibody against total p38, ERK1/2, or JNK. Arrows indicate samples that were exposed to TNF-α or H2O2. Optical density data from 4 independent experiments were analyzed by Student’s t test.

Figure 4.

TNF-α and H2O2 activate p38 MAPK in mouse diaphragm. Mouse diaphragm was excised and incubated in Krebs-Ringer’s solution bubbled with 95%-5% O2-CO2 at room temperature. One hemidiaphragm from each animal was exposed to TNF-α 500 ng/mL or H2O2 300 µM for 30 min (arrows). The contralateral hemidiaphragm was exposed to the buffer only. Protein extracts prepared from the hemidiaphragms were analyzed by Western blot for p38 activation by use of a phosphospecific antibody. Optical density data from 4 hemidiaphragm pairs were analyzed by Student’s t test.

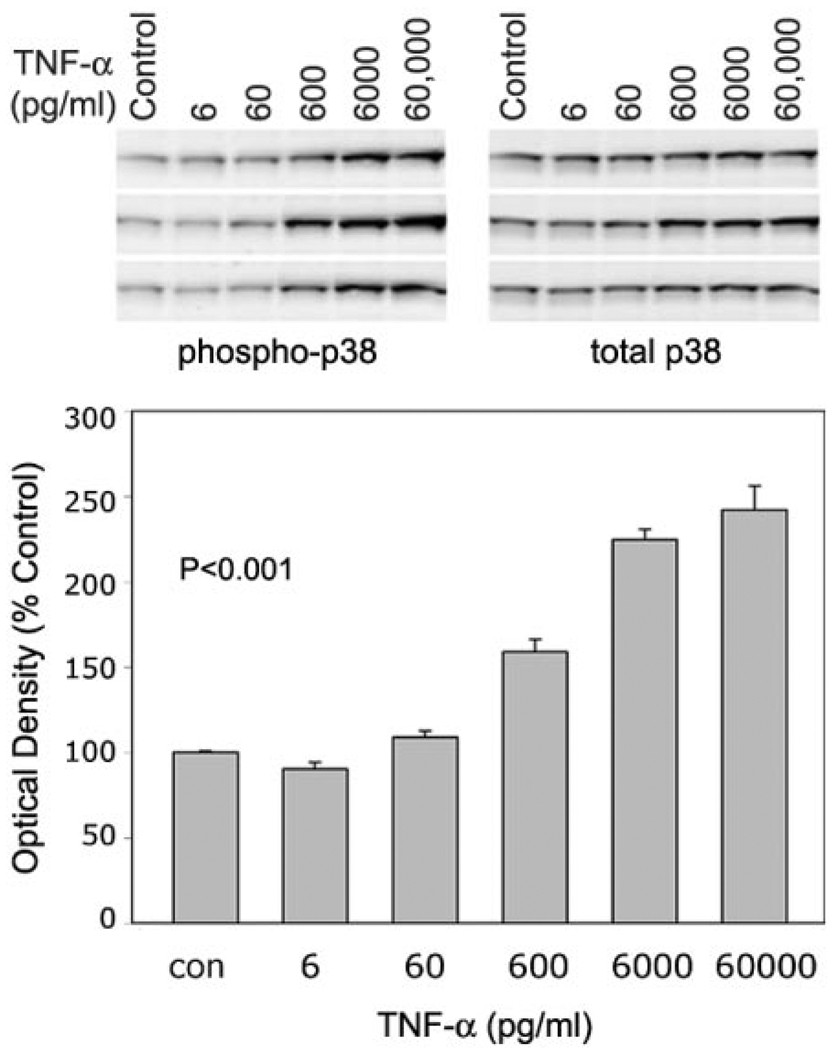

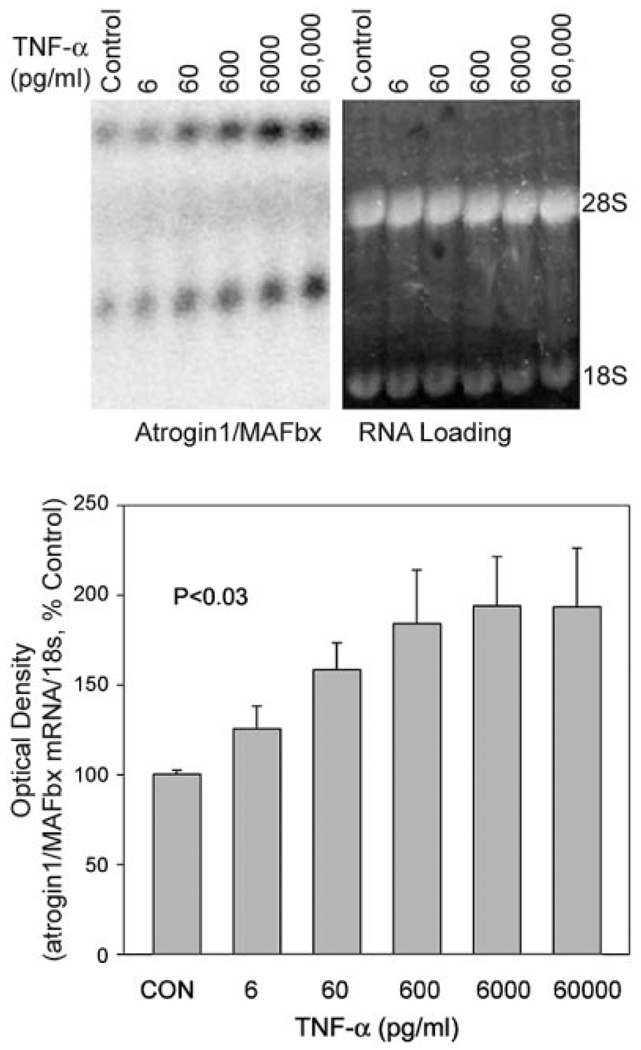

TNF-α effects on p38 MAPK and atrogin1/MAFbx are dose dependent

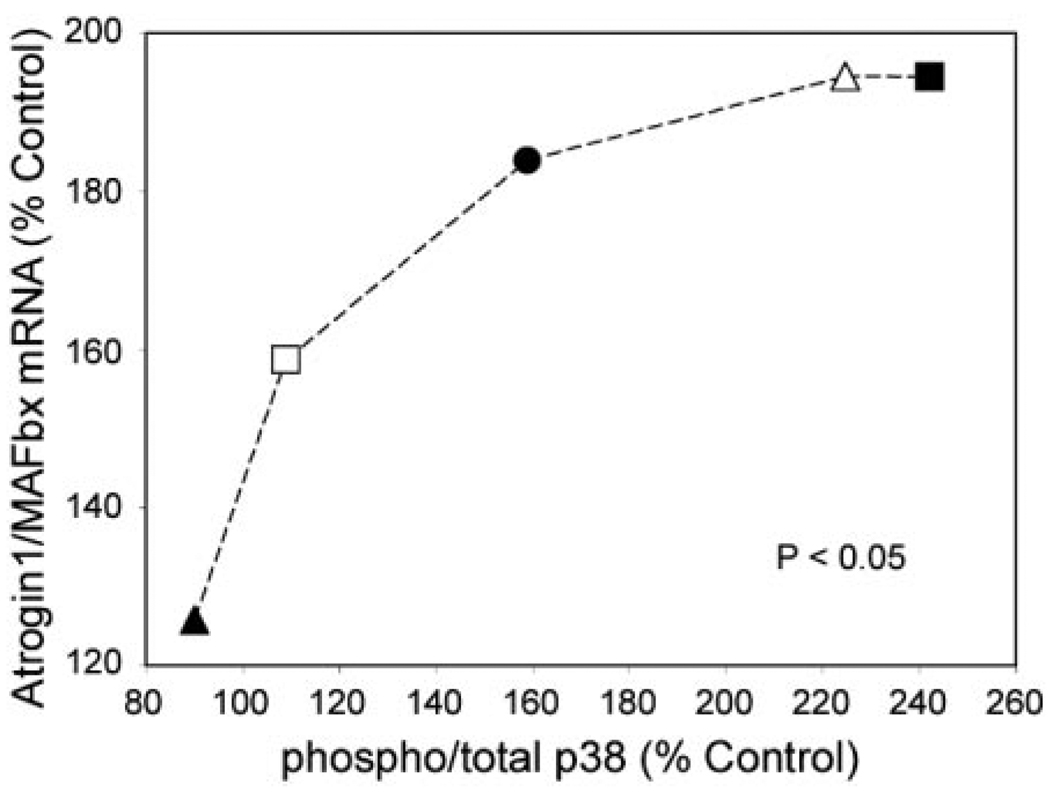

To evaluate the relationship between p38 phosphorylation and atrogin1/MAFbx expression, we measured changes in each parameter after exposing myotubes to TNF-α concentrations ranging from 6 to 60,000 pg/ mL. The p38 MAPK data are shown in Fig. 5. Densitometry indicates a dose-dependent increase in the phospho-to-total p38 ratio, evidence of progressive p38 activation by TNF-α. Figure 6 shows a similar response by atrogin1 mRNA. Myotube content of both transcripts appeared to increase with TNF-α concentration. Normalized for 18 s mRNA levels, averaged values for total atrogin1 mRNA showed a clear dose-dependent increase. Figure 7 shows that atrogin1/MAFbx up-regulation was positively related to p38 MAPK activation. Small increases in enzyme phosphorylation were associated with marked elevation of atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA levels, suggesting p38 MAPK might influence atrogin1/MAFbx expression.

Figure 5.

TNF-α effects on p38 MAPK phosphorylation are dose dependent. C2C12 myotubes were exposed to TNF-α at the indicated concentrations for 2 h and protein was extracted for Western blot analysis. Upper panel shows original blots from 3 experiments. Extracts were analyzed for phosphorylated p38 (left) and total p38 (right). Lower panel depicts the averaged ratios of phospho-to-total p38 (±se) at each TNF-α concentration as calculated from densitometry data. TNF-α increased this ratio in a dose-dependent manner; P < 0.001 by ANOVA.

Figure 6.

TNF-α effects on atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA levels are dose dependent. C2C12 myotubes were exposed to TNF-α at the indicated concentrations for 2 h and total RNA was extracted for Northern blot analysis. Upper panel is a representative blot showing multiple atrogin1/MAFbx transcripts (left) and ethidium bromide-stained loading controls (right). Lower panel depicts averaged densitometry data from 3 separate experiments showing the dose dependence of atrogin1/MAFbx up-regulation; P < 0.03 by ANOVA.

Figure 7.

Relationship between p38 MAPK activation and atrogin1/MAFbx expression. Figure depicts changes in atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA as a function of phospho-p38 levels; each data point represents averaged measurements from 3 experiments in which C2C12 myotubes were exposed to a common TNF-α concentration; filled triangle, 6 pg/mL; open square, 60 pg/mL; filled circle, 600 pg/mL; open triangle, 6,000 pg/mL; filled square, 60,000 pg/mL; regression analysis indicated best fit by a second order polynomial: y = −0.0048x2 + 2.0104x − 10.841, R2 = 0.9699, P < 0.05 (curve not shown).

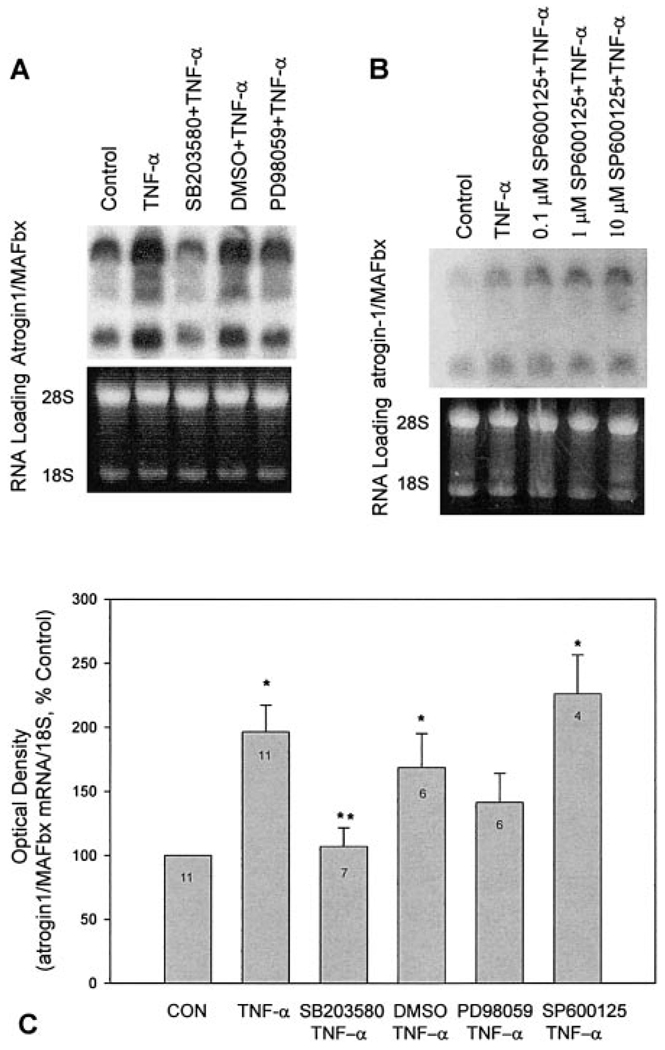

p38 MAPK inhibition blocks atrogin1/MAFbx up-regulation by TNF-α

Causality was assessed by use of pharmacological probes. Data in Fig. 8 show that SB203580, a selective p38 inhibitor (28), blunted up-regulation of the atrogin1/MAFbx gene in TNF-α-treated myotubes. The ERK inhibitor PD98059 (29) had less effect; SP600125, a JNK inhibitor (30), and DMSO had none. p38 MAPK involvement was reinforced by follow-up studies in which H2O2 up-regulation of atrogin1/MAFbx was inhibited by SB203580 but not PD98059 (data not shown).

Figure 8.

p38 MAPK mediates TNF-α up-regulation of atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression. C2C12 myotubes were preincubated with SB203580 5 µM, PD98059 35 µM, SP600125 0.1–10 µM, or DMSO 0.1% (vehicle) for 30 min before 2 h incubation with TNF-α 6 ng/mL. Total RNA was extracted and analyzed by Northern blot for atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA. A, B) Representative blots showing multiple transcripts (bands at ~6.5, 5, 4, and 2.4 kb) and RNA loading. Optical density data are shown in panel C. SP600125 data reflect responses to 10 µM. Data were analyzed using ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Sample sizes are indicated by numbers shown in each bar; *different from control; **different from TNF-α-treated samples (P<0.05).

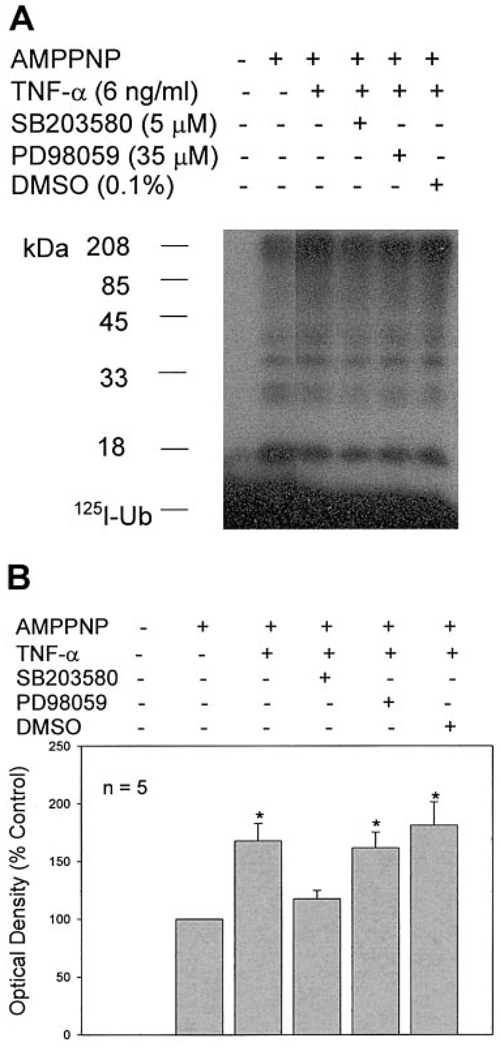

Functional importance of these effects was tested by measuring general activity of the ubiquitin conjugating pathway. We previously showed that TNF-α stimulates activity of this pathway (18). This response is illustrated in Fig. 9, where ubiquitin conjugating activity is increased in C2C12 myotubes 6 h after TNF-α exposure. Pretreatment with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 inhibited this response. On average, the ERK inhibitor PD98059 did not. Subsequent studies showed that curcumin 25 µM, a second inhibitor of p38 activation (31), also prevented increases in atrogin1/MAFbx gene expression and ubiquitin conjugating activity stimulated by either TNF-α or H2O2 (data not shown).

Figure 9.

p38 MAPK mediates TNF-α stimulation of ubiquitin conjugating activity. C2C12 myotubes were preincubated with SB203580, PD98059, or DMSO for 30 min before 6 h incubation with TNF-α. Cell extracts were prepared and analyzed for ubiquitin conjugating activity. Muscle proteins that incorporated 125I-Ubiquitin were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. Ubiquitin conjugating activity was quantified by densitometry. Data from 5 experiments were analyzed by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. *Different from control (P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates that differentiated skeletal muscle cells up-regulate the atrogin1/MAFbx gene when stimulated by TNF-α. This response is associated with increased activity of the ubiquitin conjugating pathway and appears to be mediated by p38 MAPK signaling. These findings advance our understanding of the transcriptional mechanisms that regulate muscle catabolism and suggest potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

TNF-α and the atrogin1/MAFbx gene

Circulating TNF-α levels are elevated in a wide variety of conditions including cancer, AIDS, congestive heart failure, and COPD: chronic inflammatory diseases where muscle wasting presents a lethal threat to patients (15). Evidence that circulating TNF-α promotes muscle catabolism was first obtained in studies of animals treated with exogenous TNF-α (32, 33), transgenic animals that overexpressed TNF-α (34), and animals with experimental diseases that elevate endogenous TNF-α, i.e., sepsis (35) or tumor implantation (36). Subsequently it was demonstrated that TNF-α acts directly on cultured myotubes to stimulate loss of muscle protein (24).

The downstream target of catabolic signaling in TNF-α-stimulated muscle appears to be the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Intravenous administration of TNF-α to rodents increases ubiquitin content and ubiquitin-conjugated protein levels in muscle (16) and in vitro incubation with TNF-α increases ubiquitin mRNA in rat limb muscle (17). We recently demonstrated that TNF-α stimulates activity of the ubiquitin conjugating pathway in differentiated myotubes by up-regulating expression of UbcH2, an E2 protein highly expressed in striated muscle (18).

The present study demonstrates that TNF-α also stimulates expression of the gene for a key E3 protein, atrogin1/MAFbx. This gene is constitutively expressed in both differentiated myotubes and adult mouse skeletal muscle, suggesting atrogin1/MAFbx plays a physiological role in regulating protein turnover. Atrogin1/ MAFbx involvement in muscle atrophy was established by Gomes et al. (5) and Bodine et al. (4), who demonstrated that the gene is up-regulated in experimental models of catabolism that included fasting, diabetes, cancer, renal failure, hindlimb suspension, immobilization, and denervation. Atrogin1/MAFbx is also up-regulated in animal models of experimental sepsis (7, 8) and in differentiated myotubes exposed to H2O2 (9) or glucocorticoids (37). The functional importance of atrogin1/MAFbx is evident in atrogin1/MAFbx-deficient mice, which are resistant to experimentally induced muscle atrophy (4), suggesting up-regulation of this gene is critical for muscle catabolism. The current study is the first to demonstrate atrogin1/MAFbx up-regulation in response to cytokine stimulation. The data identify an additional transcriptional mechanism by which TNF-α may induce muscle wasting and reinforce the potential importance of TNF-α as a catabolic stimulus in inflammatory disease.

Regulation of the atrogin1/MAFbx gene by p38 MAPK

TNF-α clearly activates all three major MAPK signaling pathways in skeletal muscle. However, inhibitor studies suggest that atrogin1/MAFbx expression preferentially responds to p38 MAPK. p38 is a stress-activated protein kinase that responds to a variety of stimuli, including oxidative stress and TNF-α (38), and has been identified as a likely mediator of catabolic signaling in skeletal muscle (19). This is consistent with a recent report by Di Giovanni et al. (21) that constitutive p38 phosphorylation is elevated in atrophic muscles of patients with acute quadriplegic myopathy. Microarray data from these muscles showed a concurrent elevation of gene products related to the ubiqutin-proteasome pathway, including atrogin1/MAFbx. The same study also demonstrated increased p38 phosphorylation in muscles of individuals with neurogenic muscle atrophy. Childs and associates (20) found that experimental immobilization of the rat hindlimb for 10 days caused a 128% increase in p38 phosphorylation. This was associated with a 38% decrease in soleus muscle mass over the same period. Other procatabolic conditions in which constitutive phosphorylation of skeletal muscle p38 has been shown to be elevated include Type 2 diabetes (22) and aging (23).

Our current data suggest the atrogin1/MAFbx gene is a downstream target of p38 MAPK signaling. This is consistent with the concept that pathologic elevation of p38 activity favors protein degradation and muscle atrophy. The present study does not identify the immediate target of p38 kinase activity or the mechanism by which p38 increases atrogin1/MAFbx mRNA levels. An attractive possibility is that p38 MAPK contributes to the activation of Foxo (forkhead-type) transcription factors (39). Sandri and associates (40) and Stitt et al. (41) recently identified Foxo as an essential regulator of atrogin1/MAFbx expression in skeletal muscle. Both groups showed that Foxo is tonically inhibited by phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and Akt and that decrements in PI3K/Akt signaling allow Foxo activity to increase, stimulating atrogin1/MAFbx expression and muscle atrophy (40, 41). The possibility that p38 MAPK modulates the PI3K/Akt/Foxo pathway, either directly or indirectly, is a clear hypothesis for future testing.

ROS regulation of ubiquitin conjugating activity

Increased ROS activity and oxidative stress are closely associated with loss of muscle mass in catabolic states that include cancer (42), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (43), congestive heart failure (44), aging-induced sarcopenia (45), and immobilization (46). TNF-α binding to surface receptors increases ROS activity within skeletal muscle fibers (12) and activates redox-sensitive transcription factors and protein kinases, including NF-κB, AP-1, p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, and JNK (13). Among these, NF-κB has been shown to mediate TNF-α-induced up-regulation of the UbcH2 gene (18) but not the atrogin1/MAFbx gene (9). In the current study, we found that p38 activity and atrogin1/ MAFbx expression are both stimulated by H2O2 and that the latter response is inhibited by p38 blockade. These data support a second messenger role for H2O2 in TNF-α signaling and are consistent with observations that H2O2 stimulates expression of E2 and E3 proteins in differentiated myotubes and increases general activity of the ubiquitin conjugating pathway in the absence of TNF-α (9).

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AR049022, Y.-P.L.; HL59878, M.B.R.; HL58081, HL61543, HL42250-10/10, GM59203, D.L.M.), National Space Biomedical Research Institute (M.B.R.), Muscular Dystrophy Association (M.B.R.), and Veterans Administration P50 HL-O6H (D.L.M.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Jagoe RT, Goldberg AL. What do we really know about the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in muscle atrophy? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2001;4:183–190. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lecker SH, Solomon V, Price SR, Kwon YT, Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Ubiquitin conjugation by the N-end rule pathway and mRNAs for its components increase in muscles of diabetic rats. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:1411–1420. doi: 10.1172/JCI7300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VKM, Nunez L, Clarke BA, Poueymirou WT, Panaro FJ, Na E, Dharmarajan K, et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science. 2001;294:1704–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1065874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes MD, Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Navon A, Goldberg AL. Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14440–14445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251541198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Gilbert A, Gomes M, Baracos V, Bailey J, Price SR, Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy involve a common program of changes in gene expression. FASEB J. 2004;18:39–51. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0610com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wray CJ, Mammen JM, Hershko DD, Hasselgren PO. Sepsis upregulates the gene expression of multiple ubiquitin ligases in skeletal muscle. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2003;35:698–705. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dehoux MJ, van Beneden RP, Fernandez-Celemin L, Lause PL, Thissen JP. Induction of MAFbx and MuRF ubiquitin ligase mRNAs in skeletal muscle after LPS injection. FEBS Lett. 2003;544:214–217. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y-P, Chen Y, Li AS, Reid MB. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates ubiquitin-conjugating activity and expression of genes for specific E2 and E3 proteins in skeletal muscle myotubes. Am. J. Physiol. 2003;285:C806–C812. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00129.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finkel T. Reactive oxygen species and signal transduction. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:3–6. doi: 10.1080/15216540252774694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goossens V, Grooten J, De Vos K, Fiers W. Direct evidence for tumor necrosis factor-induced mitochondrial reactive oxygen intermediates and their involvement in cytotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:8115–8119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Moody MR, Engel D, Walker S, Clubb FJ, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL, Reid MB. Cardiac-specific overexpression of TNF-α causes oxidative stress and contractile dysfunction in mouse diaphragm. Circulation. 2000;102:1690–1696. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.14.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg AK, Aggarwal BB. Reactive oxygen intermediates in TNF signaling. Mol. Immunol. 2002;39:509–517. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid MB, Li Y-P. Cytokines and oxidative signalling in skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2001;171:225–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2001.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y-P, Reid MB. Effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on skeletal muscle metabolism. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2001;13:483–487. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Martinez C, Agell N, Llovera M, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha increases the ubiquitinization of rat skeletal muscle proteins. FEBS Lett. 1993;323:211–214. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81341-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llovera M, Garcia-Martinez C, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. TNF can directly induce the expression of ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system in rat soleus muscles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;230:238–241. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.5827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y-P, Lecker SH, Chen Y, Waddell ID, Goldberg AL, Reid MB. TNF-α increases ubiquitin-conjugating activity in skeletal muscle by up-regulating UbcH2/E2-20k. FASEB J. 2003;17:1048–1057. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0759com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tracey KJ. Lethal weight loss: the focus shifts to signal transduction. Sci. STKE. 2002;130:PE21. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.130.pe21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Childs TE, Spangenburg EE, Vyas DR, Booth FW. Temporal alterations in protein signaling cascades during recovery from muscle atrophy. Am. J. Physiol. 2003;285:C391–C398. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00478.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Giovanni S, Molon A, Broccolini A, Melcon G, Mirabella M, Hoffman EP, Servidei S. Constitutive activation of MAPK cascade in acute quadriplegic myopathy. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:195–206. doi: 10.1002/ana.10811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koistinen HA, Chibalin AV, Zierath JR. Aberrant p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in skeletal muscle from Type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1324–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williamson D, Gallagher P, Harber M, Hollon C, Trappe S. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway activation: effects of age and acute exercise on human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2003;547:977–987. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y-P, Schwartz RJ, Waddell ID, Holloway BR, Reid MB. Skeletal muscle myocytes undergo protein loss and reactive oxygen-mediated NF-κB activation in response to tumor necrosis factor α. FASEB J. 1998;12:871–880. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.10.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu YC, Chou YC. Formaldehyde in formaldehyde/agarose gel may be eliminated without affecting the electrophoretic separation of RNA molecules. Biotechniques. 1990;9:558–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnston NL, Cohen RE. Uncoupling ubiquitin-protein conjugation from ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis by use of beta, gamma-nonhydrolyzable ATP analogues. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7514–7522. doi: 10.1021/bi00244a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuenda A, Rouse J, Doza YN, Meier R, Cohen P, Gallagher TF, Young PR, Lee JC. SB203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:229–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00357-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, Dudley DT, Saltiel AR. PD098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O'Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, et al. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carter Y, Liu G, Yang J, Fier A, Mendez C. Sublethal hemorrhage induces tolerance in animals exposed to cecal ligation and puncture by altering p38, p44/42, and SAPK/JNK MAP kinase activation. Surg. Infect. 2003;4:17–27. doi: 10.1089/109629603764655245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Martinez C, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. Acute treatment with tumour necrosis factor-alpha induces changes in protein metabolism in rat skeletal muscle. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1993;125:11–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00926829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buck M, Chojkier M. Muscle wasting and dedifferentiation induced by oxidative stress in a murine model of cachexia is prevented by inhibitors of nitric oxide synthesis and antioxidants. EMBO J. 1996;15:1753–1765. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng J, Turksen K, Yu Q, Schreiber H, Teng M, Fuchs E. Cachexia and graft-vs-host-disease-type skin changes in keratin promoter-driven TNF-α transgenic mice. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1444–1456. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmad S, Karlstad MD, Choudhry MA, Sayeed MM. Sepsis-induced myofibrillar protein catabolism in rat skeletal muscle. Life Sci. 1994;55:1383–1391. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00752-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tessitore L, Costelli P, Baccino FM. Humoral mediation for cachexia in tumour-bearing rats. Br. J. Cancer. 1993;67:15–23. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sacheck JM, Ohtsuka A, McLary SC, Goldberg AL. IGF-1 stimulates muscle growth by suppressing protein breakdown and expression of atrophy-related ubiquitin-ligases, atrogin-1 and MuRF1. Am. J. Physiol. 2004;287:E591–E601. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00073.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obata T, Brown GE, Yaffe MB. MAP kinase pathways activated by stress: the p38 MAPK pathway. Crit. Care Med. 2000;28:N67–N77. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200004001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carlsson P, Mahlapuu M. Forkhead transcription factors: key players in development and metabolism. Dev. Biol. 2002;250:1–23. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandri M, Sandri C, Cilbert A, Skurk C, Calabria E, Picard A, Walsh K, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell. 2004;117:399–412. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00400-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stitt TN, Drujan D, Clarke BA, Panaro F, Timofeyva Y, Kline WO, Gonzalez M, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:395–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tisdale MJ. Protein loss in cancer cachexia. Science. 2000;289:2293–2294. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clanton TL, Zuo L, Klawitter P. Oxidants and skeletal muscle function: physiologic and pathophysiologic implications. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1999;222:253–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.1999.d01-142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anker SD, Rauchaus M. Insights into the pathogenesis of chronic heart failure: immune activation and cachexia. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 1999;14:211–216. doi: 10.1097/00001573-199905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spiers S, McArdle F, Jackson MJ. Aging-related muscle dysfunction: failure of adaptation to oxidative stress? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000;908:341–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kondo H. Oxidative stress in muscular atrophy. In: Sen CK, Packer L, Hanninen O, editors. Handbook of Oxidants and Antioxidants in Exercise. New York: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 631–653. [Google Scholar]