Abstract

Objective

To determine the effect of criminalizing some traffic behaviours, after the reform of the Spanish penal code in 2007, on the number of drivers involved in injury collisions and of people injured in traffic collisions in Spain.

Methods

This study followed an interrupted times–series design in which the number of drivers involved in injury collisions and of people injured in traffic collisions in Spain before and after the criminalization of offences were compared. The data on road traffic injuries in 2000–2009 were obtained from the road traffic collision database of the General Traffic Directorate. The dependent variables were stratified by sex, age, injury severity, type of road user, road type and time of collision. Quasi-Poisson regression models were fitted with adjustments for time trend, seasonality, previous interventions and national fuel consumption.

Findings

The overall number of male drivers involved in injury collisions dropped (relative risk, RR: 0.93; 95% confidence interval, CI: 0.89–0.97) after the reform of the penal code, but among women no change was observed (RR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.95–1.03). In addition, 13 891 men (P < 0.01) were prevented from being injured. Larger reductions were observed among young male drivers and among male motorcycle or moped riders than among the drivers of other vehicles.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that criminalizing certain traffic behaviours can improve road safety by reducing both the number of drivers involved in injury collisions and the number of people injured in such collisions.

ملخص

الغرض

تحديد تأثير تجريم بعض السلوكيات المرورية، بعد تعديل مدوّنة العقوبات الأسبانية في عام 2007، على عدد السائقين المتورطين في إصابات حوادث الاصطدامات المرورية والمصابين فيها في أسبانيا.

الطريقة

اتبعت هذه الدراسة تصميماً منقطعاً للتسلسل الزمني حيث قورن بين عدد السائقين في إصابات حوادث الاصطدامات المرورية والمصابين فيها في أسبانيا قبل وبعد تجريم المخالفات. وجمعت المعطيات حول الإصابات المرورية على الطرق خلال الأعوام 2000-2009 من قاعدة معطيات حوادث الاصطدامات المرورية في إدارة المرور العامة. وجرى تقسيم المتغيرات المستقلة حسب الجنس، والعمر، وشدة الإصابة، ونوع مستخدمي الطرق، ونوع الطريق، ووقت حدوث التصادم. وجرى مواءمة نماذج التحوّف لكوازي وبواسون Quasi-Poisson بتعديل نزعة الوقت، والمواسم، والتدخلات السابقة.

النتائج

انخفض عدد السائقين الرجال المتورطين في إصابات حوادث الاصطدام بعد إصلاح مدوّنة العقوبات (الاختطار النسبي: 0.93؛ فاصلة الثقة 95%: 0.89-0.97)، ولكن لم يلاحظ تغيّر بين السائقات (الاختطار النوعي: 0.99؛ فاصلة الثقة 95%: 0.95-1.03). بالإضافة إلى وقاية 13891 رجلاً من التعرض للإصابة (قوة الاحتمال P أقل من 0.01). وقد لوحظ انخفاض أكبر بين شباب السائقين الذكور وبين قائدي الدراجات النارية مقارنة بقائدي المركبات الأخرى.

الاستنتاج

تدل النتائج على أن تجريم بعض السلوكيات المرورية يمكنه أن يحسن مستوى السلامة على الطرق وذلك بخفض عدد السائقين المتورطين في الإصابات الناجمة عن حوادث الاصطدام وعدد المصابين في هذه الحوادث.

摘要

目的

旨在确定2007年西班牙刑法改革之后,对一些交通行为进行刑事定罪对西班牙涉及交通碰撞损伤的司机以及交通碰撞中受伤的人数的影响。

方法

本研究遵循断续时间序列设计,研究中我们对西班牙交通违规刑事定罪前后涉及交通碰撞损伤以及在交通碰撞中受伤的人数进行对比。2000至2009年的交通损伤数据从交通总局的道路交通碰撞数据库中获得。因变量按性别、年龄、损伤程度、道路使用者类型、道路类型以及碰撞时间进行分层。准泊松回归模型与时间趋势、季节性以及之前干预措施方面的调整相适应。

结果

西班牙刑法改革之后,涉及交通碰撞损伤的男性司机的总人数下降(相对危险度RR:0.93;95%可信区间CI:0.89-0.97),然而女性司机中没有明显变化(相对危险度=0.99;95%可信区间0.95-1.03)。此外,13 891名男性(P < 0.01)因此而免于受伤。与其他车辆司机相比,年轻男性司机中以及男性摩托车或电动车司机中受伤者人数出现较大幅度下降。

结论

研究结果表明,对某些交通行为进行刑事定罪能够通过减少涉及交通碰撞损伤司机的数量以及碰撞中的受伤人数来改善行车安全。

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer l'effet de la criminalisation de certains comportements routiers, après la réforme du Code pénal espagnol en 2007, sur le nombre de conducteurs impliqués dans des collisions avec blessures et le nombre de personnes blessées dans des collisions en Espagne.

Méthodes

Cette étude a suivi un plan chronologique interrompu dans lequel le nombre de conducteurs impliqués dans des collisions avec blessures et le nombre de personnes blessées dans des collisions de la route en Espagne ont été comparés avant et après la criminalisation des délits. Les données sur les blessures dues à des accidents de la route sur la période 2000-2009 proviennent de la base de données des accidents de la route de la Direction générale de la Circulation. Les variables dépendantes ont été stratifiées par sexe, âge, gravité de la blessure, type d'usager, type de route et heure de la collision. Des modèles de régression quasi-Poisson ont été adaptés à la tendance temporelle, à la saisonnalité, aux interventions précédentes et à la consommation de carburant.

Résultats

Le nombre total de conducteurs de sexe masculin impliqués dans des collisions avec blessures a diminué (risque relatif, RR: 0,93; 95% d'intervalle de confiance, IC: 0,89–0,97) après la réforme du Code pénal, mais chez les femmes, aucun changement n'a été observé (RR: 0,99; 95% de CI: 0,95–1,03). L’initiative a en outre permis à 13 891 hommes (P <0,01) de ne pas se blesser. Des diminutions plus importantes ont été observées chez les jeunes conducteurs de sexe masculin et chez les conducteurs de moto ou de vélomoteur de sexe masculin que chez les conducteurs d'autres véhicules.

Conclusion

Les résultats indiquent que la criminalisation de certains comportements routiers peut améliorer la sécurité routière en réduisant à la fois le nombre de conducteurs impliqués dans des collisions avec blessures et le nombre de personnes blessées dans de telles collisions.

Resumen

Objetivo

Determinar el efecto de criminalizar ciertos comportamientos de tráfico, tras la reforma del Código Penal español el 2007, sobre el número de conductores implicados en colisiones con lesionados y en el número de personas lesionadas de tráfico en España.

Métodos

Este estudio siguió un diseño de series temporales interrumpidas, en el que se comparó el número de conductores implicados en colisiones con lesionados y el número de personas lesionadas de tráfico antes y después de la criminalización de dichos comportamientos. Los datos de las lesiones de tráfico entre los años 2000 y 2009 se obtuvieron de la base de datos de accidentes de tráfico de la Dirección General de Tráfico. Las variables dependientes se estratificaron por sexo, edad, gravedad de la lesión, tipo de usuario de la vía, tipo de vía y momento de la colisión. Se ajustaron modelos de regresión Quassi-Poisson, ajustados por tendencia lineal, estacionalidad e intervenciones previas.

Resultados

El número total de hombres conductores implicados en colisiones con lesionados descendió (riesgo relativo, RR:0,93; intervalo de confianza al 95%: 0,89-0,97) tras la reforma del Código Penal, si bien no se observaron cambios significativos en el caso de las mujeres (RR:0,99; IC 95%: 0,95-1,03). Además, 13 891 hombres (P<0,01) fueron prevenidos de ser lesionados. Se observó una mayor reducción en los hombres conductores jóvenes y en los hombres conductores de motocicleta o ciclomotor que en los conductores de otros vehículos.

Conclusión

Los resultados sugieren que la criminalización de determinados comportamientos de tráfico puede mejorar la seguridad vial reduciendo tanto el número de conductores implicados en colisiones con lesionados como el número de personas lesionadas en colisiones de tráfico.

Резюме

Цель

Определить воздействие уголовной ответственности, введенной за некоторые виды поведения водителей транспортных средств после реформы уголовного кодекса в Испании в 2007 году, на количество водителей – участников ДТП с травматическими последствиями и численность лиц, травмированных в ДТП.

Методы

Данное исспедование основано на анализе прерванных временных рядов, в котором сравнивались число водителей – участников ДТП с травматическими последствиями и численность лиц, травмированных в ДТП, в Испании до и после введения уголовной ответственности за правонарушения. Статистика дорожно-транспортного травматизма за 2000–2009 годы была взята из базы данных о ДТП Главного управления безопасности дорожного движения. Зависимые переменные были стратифицированы по полу, возрасту, тяжести травмы, типу участника дорожного движения, виду дороги и времени наступления ДТП. Модели регрессии с квазипуассоновским распределением были скорректированы с учетом временнόго тренда, сезонности и принятых ранее мер вмешательства.

Результаты

После реформы уголовного кодекса общая численность водителей-мужчин – участников ДТП резко снизилась (относительный риск, ОР: 0,93; 95% доверительный интервал, ДИ: 0,89–0,97), однако среди женщин не наблюдалось каких-либо изменений (ОР = 0,99; 95% ДИ: 0,95–1,03). Кроме того, удалось предотвратить травмы у 13 891 мужчин (P < 0,01). Среди молодых водителей-мужчин, особенно среди мотоциклистов и водителей мопедов, наблюдалось более значительное снижение, чем среди водителей других транспортных средств.

Вывод

Полученные результаты свидетельствуют, что введение уголовной ответственности за некоторые виды поведения водителей транспортных средств могут привести к повышению безопасности дорожного движения благодаря уменьшению числа водителей, участвовавших в ДТП с травматическими последствиями, и численности людей, травмированных в этих ДТП.

Introduction

Although road traffic injuries in Spain are decreasing, they still constitute a major public health problem. During 2008, 134 047 people suffered road traffic injuries and 3100 lost their lives in collisions.1 In recent years, the Spanish government has implemented several measures to reduce the burden of traffic injuries. In 2004 it established road safety as a political priority and created the Special Road Safety Measures 2004–20052 and the Strategic Road Safety Programme 2005–20083, which comprise several interventions focused primarily on the enforcement of traffic regulations. These regulations and their enforcement have reduced traffic injuries in Spain by 9% among men and 11% among women.4 In addition, the introduction of a penalty points system in July 2006 was followed by reductions of 11% and 12% in the number of men and women, respectively, who were seriously injured in traffic collisions across Spain.5

Legislation alone is unlikely to deter road users from engaging in risky behaviours. To be effective, it must be rigorously enforced and must strongly deter unlawful behaviour by generating awareness and fear of the consequences of breaking the law. This, in turn, depends on the degree of traffic surveillance, the severity of the penalty issued and the swiftness with which it is imposed. Public awareness campaigns can make legislation more effective.6–8

Despite existing laws, in Spain the number of injuries and deaths attributable to speeding and drunk driving is still extremely high. One year after the penalty points system was introduced, the main traffic offences punishable by penalty points were occurring at the following rates: speeding, 39.3%; non-compliance with wearing passive restraint devices, 15.5%; drunk driving, 11.6%.9 To further reduce road injuries linked to these behaviours, the penal code was modified on 1 December 2007. Several traffic offences were criminalized, with a change in the legal process for trying offenders from a civil to a criminal procedure. The main criminalized offences were driving over the speed limit, drunk driving, reckless driving and driving without a licence. The penalties for these violations depend on the severity of the offence but include imprisonment, a fine, compulsory community service or licence suspension (Table 1). Prior to this reform, speeding and drunk driving were also considered crimes but the penalties were much more lenient and there was no officially established speed or blood alcohol level marking the threshold for criminality, which left it up to the judge to decide. The penal code reform eliminates subjectivity and incorporates stricter penalties, including compulsory imprisonment in certain cases and a possible criminal record. An important publicity campaign was launched in all news media and intense public debate ensued.

Table 1. Traffic offences criminalized under the reformed Spanish penal code (2007) and their associated penalties.

| Offence | Prison term | Finea | Community service | Licence suspension |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exceeding speed limitb | 3–6 mob | 6–12 mob | 31–90 d | 1–4 y |

| Driving under the influence of alcohol (BAC > 1.2 g/l) or other drugs | 3–6 mob | 6–12 mob | 31–90 d | 1–4 y |

| Reckless drivingc and risking the lives or safety of others | 6–24 mo | 1–6 y | ||

| Reckless driving,c showing contempt for the lives of others and risking their lives or safety | 2–5 y | 12–24 mo | 6–10 y and vehicle requisition | |

| Reckless driving,c showing contempt for the lives of others without risking their lives or safety | 1–2 y | 6–12 mo | 6–10 y and vehicle requisition | |

| Criminalized offences and injury to others | 2.5–4 y | Definitive suspension | ||

| Refusing to undergo alcohol or other drugs tests | 6–12 mo | 1–4 y | ||

| Driving without a licence | 3–6 mob | 12–24 mob | 10–40 d | |

| Generating road traffic riskd | 6–24 mob | 12–24 mob | 10–40 d |

BAC, blood alcohol concentration; d, days; mo, months; y, years.

a Between 60 and 1200 euros a month depending on economic and personal circumstances. Offenders can choose between a prison term and a fine.

b Driving at > 60 km/h on urban roads and at > 80 km/h on non-urban roads.

c Punishable speeding or driving under the influence of alcohol or other drugs.

d Includes leaving obstacles on the road, spilling slippery or flammable substances, modifying or destroying road signs or not restoring road safety when responsible for altering it.

So far, studies have only assessed the effectiveness of criminalizing driving under the influence of alcohol10–15 but not other behaviours. The present study fills that gap by examining the effect of criminalizing several road behaviours on the numbers of drivers involved in injury collisions and of people injured in traffic collisions in Spain, broken down by gender, age, injury severity, type of road user, road type and time of collision. The working hypothesis is that criminalizing risky behaviours has reduced traffic injuries in Spain in the context of a previous downward trend resulting from road safety interventions implemented during previous years.

Methods

Study design and population

We used an interrupted time-series design to conduct an evaluation study in two study populations: (i) the number of drivers (injured or unharmed) involved in traffic collisions resulting in injury to self or to others (i.e. injury collisions) and (ii) the number of people injured in traffic collisions in Spain in 2000–2009.

Sources of information

We obtained traffic injury data from the Road Traffic Crashes Database of Spain’s General Traffic Directorate (Dirección General de Tráfico, DGT), which records injury collisions, the characteristics of the collision, and the vehicle and people involved. In Spain this information is collected and submitted to the DGT by the national and local police forces, who attend to non-urban and urban roads, respectively. Data on national fuel consumption, used as a proxy for exposure to traffic, was obtained from the Spanish Ministry of Public Works.

Variables

The dependent variables were the number of drivers involved in injury collisions and the number of people injured in traffic collisions. Analyses were stratified by the following: gender;16 age; injury severity as classified by the police (no harm [drivers only], slight, serious non-fatal [hospitalized > 24 hours], fatal); type of road user (car, motorcycle or moped, or pedestrian [only for the injured]); road type (urban, non-urban), and time of collision (weekday daytime, weekday night-time, weekend daytime, weekend night-time).

The main explanatory variable was the reform of the penal code. A dummy variable was created to compare rates before (1 January 2000 to 30 November 2007) and after (1 December 2007 to 31December 2009) the intervention. To adjust for the effect of road safety prioritization in 2004 and the introduction of the penalty points system in July 2006, we included two additional dummy variables in the models for the periods before and after these interventions were introduced. To adjust for changes in traffic exposure over the study period, we also included in the analyses a variable representing national fuel consumption as a proxy for motorised mobility across the population.

Statistical analysis

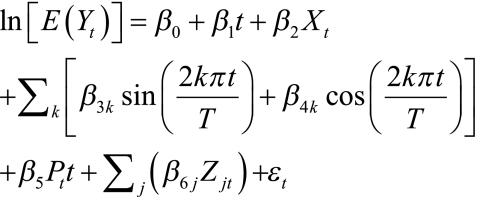

We performed time-series analyses using Poisson regression models adjusted for over-dispersion (quasi-Poisson).17 The number of drivers (and of people injured) per month was compared throughout the time series with adjustments for time trend and seasonal patterns using linear trend and sine and cosine functions.18 The model for each outcome can be summarized as follows:

|

where t is the time period (t = 1 for the first month of the series, t = 2 for the second, etc.); Xt identifies the pre- and post-intervention periods (Xt = 1 for the post-intervention period); k takes values between 1 and 6 (k = 1 for annual seasonality; k = 2 for six-monthly seasonality, etc.); T is the number of periods described by each sinusoidal function (e.g. t = 12 months); Pt is the dummy variable for road safety prioritization, multiplied by the time trend (t) (i.e. an interaction term) to take into account the differences in the time trend before and after the year 2004;19 Zjt represents other co-variables introduced (penalty points system and national fuel consumption); j is the number of co-variables introduced, and ε is the error term. We derived relative risks (RRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from the adjusted models. They indicate the difference between the number of drivers involved (or people injured) in injury collisions before and after the intervention, after adjustments for time trend and seasonality. From the RRs we computed the percentage change in the number of drivers (or people injured) between the two periods.

The number of people prevented from being injured attributable to the reform of the penal code was calculated as the difference between the number of people injured in the post-intervention period and the number predicted by the statistical models.

We conducted the statistical analyses using Stata statistical software, release 10 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, United States of America).

Ethical approval

The present study was approved by the ethics committee (Comitè Ètic d’Investigació Clínica) of the Institut Municipal d’Assistència Sanitària.

Results

In 2000–2009, 1 668 889 drivers were involved in injury collisions in Spain (annual median: 170 879). Most of them (78.7%) were male drivers, 70.7% of whom were between 18 and 44 years of age. An additional 1 454 971 people were injured in traffic collisions (annual median: 146 949). Again, most (63.4%) of them were male, and 65.1% of these males were between the ages of 18 and 44 years. Table 2 shows the distribution of these subjects by sex, age, injury severity, type of road user, road type and time of collision.

Table 2. Distribution of drivers involved in injury collisions and of people injured in traffic collisions by sex, age, injury severity, type of road user, road type, and time of collision, Spain, 2000–2009.

| Characteristic | Driversa (%) |

People injuredb (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 1 299 564) | Women (n = 309 043) | Men (n = 922 883) | Women (n = 492 059) | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 0–13 | – | – | 3.3 | 5.0 | |

| 14–15 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 | |

| 16–17 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 4.9 | 3.7 | |

| 18–29 | 35.0 | 39.5 | 38.3 | 35.2 | |

| 30–44 | 34.0 | 38.2 | 28.7 | 26.1 | |

| 45–64 | 21.9 | 17.8 | 16.5 | 18.5 | |

| 65–74 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 4.1 | 5.6 | |

| 75+ | 1.6 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 4.1 | |

| Injury severity | |||||

| Unharmed | 45.1 | 36.3 | – | – | |

| Slight | 43.5 | 56.3 | 79.3 | 85.7 | |

| Serious | 9.6 | 6.6 | 17.4 | 12.6 | |

| Fatal (24 hours) | 1.8 | 0.8 | 3.3 | 1.7 | |

| Type of road user | |||||

| Car driver/user | 63.5 | 80.9 | 53.3 | 67.2 | |

| Motorcycle rider/user | 9.7 | 3.8 | 13.2 | 4.5 | |

| Moped rider/user | 12.1 | 12.3 | 17.3 | 10.8 | |

| Other | 14.7 | 3.0 | 9.7 | 5.9 | |

| Pedestrian | – | – | 6.5 | 11.6 | |

| Road type | |||||

| Urban | 52.2 | 55.9 | 45.5 | 48.1 | |

| Non-urban | 47.8 | 44.1 | 54.5 | 51.9 | |

| Time of collision | |||||

| Weekday daytime | 53.6 | 61.6 | 48.9 | 52.3 | |

| Weekday night-time | 14.0 | 12.3 | 14.8 | 12.5 | |

| Weekend daytime | 16.9 | 14.5 | 18.1 | 19.6 | |

| Weekend night-time | 15.5 | 11.6 | 18.2 | 15.6 | |

a Among drivers, gender was unknown for 60 282 (3.6%), injury severity for 103 998 (6.2%) and type of road user for 47 551 (2.9%).

b Among people injured, gender was unknown for 40 029 (2.8%) and type of road user for 39 478 (2.7%).

Drivers involved in injury collisions

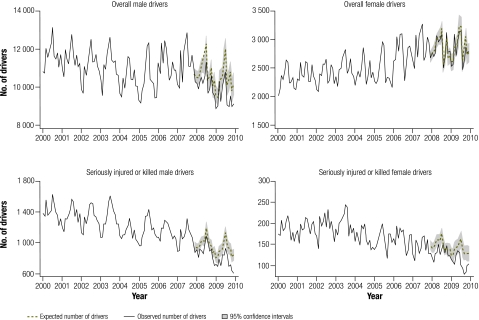

Fig. 1 depicts the observed and expected numbers of male and female drivers (overall and seriously or fatally injured) involved in injury collisions throughout the study period. The graphs show a clear reduction in the number of male drivers involved in injury collisions compared with the expected numbers; notably, no such reduction was observed among female drivers.

Fig. 1.

Observed and expected numbers of drivers involved in injury collisions, by sex and injury severity, Spain, 2000–2009

Male drivers

For male drivers the overall risk of being involved in an injury collision in the post-intervention period was reduced by 7% (RR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.89–0.97). The largest reductions in risk were observed for seriously injured and fatally injured drivers (14% and 11% reductions, respectively). No reduction in the risk of being an unharmed driver was observed (Table 3). The risk of being involved in an injury collision was reduced among all drivers under 65 years of age, but especially among those under 30.

Table 3. Adjusted relative risks (RRs)a of drivers having collisions involving injury to self or others before and after penal code reform,b by sex, driver injury severity, type of road user, road type and time of collision, Spain, 2000–2009.

| Men |

Women |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All drivers |

Seriously or fatally injured drivers |

All drivers |

Seriously or fatally injured drivers |

||||||||||||

| Monthly median | RR | 95% CI | Monthly median | RR | 95% CI | Monthly median | RR | 95% CI | Monthly median | RR | 95% CI | ||||

| Overall | 10 876 | 0.93*** | 0.89–0.97 | NA | NA | NA | 2560 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Driver injury severity | |||||||||||||||

| Unharmed | 4527 | 0.97 | 0.92–1.02 | NA | NA | NA | 900 | 0.99 | 0.93–1.06 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Slight | 4431 | 0.92*** | 0.88–0.96 | NA | NA | NA | 1352 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.04 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Serious | 986 | 0.86*** | 0.81–0.93 | NA | NA | NA | 167 | 0.93 | 0.83–1.04 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Fatal | 181 | 0.89*** | 0.81–0.97 | NA | NA | NA | 18 | 0.82 | 0.64–1.05 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||||

| 14–15 | 76 | 0.80*** | 0.70–0.91 | 17 | 0.82 | 0.63–1.08 | 15 | 0.77 | 0.58–1.01 | 2 | 0.69 | 0.30–1.60 | |||

| 16–17 | 281 | 0.81*** | 0.74–0.88 | 54 | 0.91 | 0.78–1.06 | 43 | 0.87 | 0.73–1.04 | 5 | 0.71 | 0.44–1.17 | |||

| 18–29 | 3705 | 0.87*** | 0.83–0.91 | 408 | 0.80*** | 0.74–0.86 | 986 | 0.96 | 0.91–1.04 | 73 | 0.91 | 0.80–1.03 | |||

| 30–44 | 3547 | 0.91*** | 0.87–0.94 | 363 | 0.83*** | 0.77–0.89 | 937 | 0.96 | 0.91–1.01 | 60 | 0.92 | 0.80–1.01 | |||

| 45–64 | 2288 | 0.92*** | 0.88–0.95 | 224 | 0.88** | 0.81–0.97 | 427 | 0.94* | 0.89–1.00 | 32 | 0.90 | 0.76–1.07 | |||

| 65–74 | 423 | 0.98 | 0.92–1.04 | 56 | 0.95 | 0.81–1.11 | 42 | 1.12 | 0.97–1.31 | 4 | 1.65* | 1.01–2.72 | |||

| 75+ | 163 | 0.99 | 0.91–1.08 | 27 | 1.01 | 0.84–1.21 | 12 | 1.19 | 0.94–1.51 | 1 | 0.82 | 0.36–1.86 | |||

| Type of driver by road type | |||||||||||||||

| Urban road | |||||||||||||||

| All drivers | 5665 | 0.94* | 0.90–1.00 | 296 | 0.88** | 0.81–0.96 | 1416 | 0.99 | 0.93–1.05 | 48 | 0.94 | 0.79–1.11 | |||

| Car drivers | 3254 | 0.99 | 0.94–1.04 | 66 | 0.97 | 0.82–1.14 | 1010 | 1.02 | 0.96–1.09 | 17 | 1.02 | 0.76–1.36 | |||

| Motorcycle riders | 637 | 0.83*** | 0.77–0.90 | 81 | 0.82** | 0.72–0.93 | 69 | 0.85** | 0.76–0.95 | 4 | 0.92 | 0.64–1.34 | |||

| Moped riders | 968 | 0.86*** | 0.80–0.92 | 127 | 0.85* | 0.75–0.97 | 266 | 0.91* | 0.84–0.99 | 22 | 0.81 | 0.63–1.03 | |||

| Non-urban road | |||||||||||||||

| All drivers | 5170 | 0.83*** | 0.79–0.88 | 866 | 0.82*** | 0.77–0.88 | 1139 | 0.88*** | 0.83–0.94 | 138 | 0.89* | 0.80–0.98 | |||

| Car drivers | 3404 | 0.87*** | 0.82–0.93 | 479 | 0.89** | 0.82–0.97 | 1033 | 0.88*** | 0.83–0.94 | 115 | 0.87 | 0.80–1.00 | |||

| Motorcycle riders | 314 | 0.71*** | 0.64–0.78 | 131 | 0.70*** | 0.62–0.79 | 11 | 0.80 | 0.60–1.06 | 3 | 0.88 | 0.54–1.43 | |||

| Moped riders | 270 | 0.79*** | 0.73–0.86 | 99 | 0.78*** | 0.68–0.89 | 39 | 0.86 | 0.73–1.02 | 11 | 0.87 | 0.62–1.23 | |||

| Time of collision | |||||||||||||||

| Daytime weekday | 5756 | 0.88*** | 0.83–0.92 | 519 | 0.84*** | 0.78–0.90 | 1543 | 0.92** | 0.87–0.97 | 101 | 0.89 | 0.79–1.01 | |||

| Night-time weekday | 1492 | 0.87** | 0.80–0.94 | 175 | 0.82*** | 0.73–0.91 | 312 | 0.92 | 0.84–1.01 | 23 | 0.92 | 0.75–1.13 | |||

| Daytime weekend | 1819 | 0.92 | 0.82–1.02 | 243 | 0.80** | 0.70–0.92 | 364 | 1.02 | 0.91–1.15 | 32 | 0.88 | 0.72–1.09 | |||

| Night-time weekend | 1657 | 0.90* | 0.82–0.99 | 219 | 0.88* | 0.78–0.99 | 294 | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 | 24 | 0.96 | 0.76–1.21 | |||

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; *P < 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

a Adjusted by time trend, seasonality, the effect of road safety prioritization in 2004, the introduction of the penalty points system in July 2006, and national fuel consumption.

b Pre-intervention period: 1 January 2000 to 30 November 2007; post-intervention period: 1 December 2007 to 31 December 2009.

A greater reduction in the risk of being involved in an injury collision was observed on non-urban roads than on urban roads (17% and 6% reduction, respectively). In addition, the effect varied by type of driver and road. Among motorcycle and moped riders, a reduction in the risk of having an injury collision was observed on both urban and non-urban roads, although the effect was larger on non-urban roads. However, for car drivers this risk was reduced only on non-urban roads. Finally, the risk was reduced during both daytime and night-time among all drivers.

Female drivers

Among female drivers, the overall risk of having an injury collision showed no significant change (RR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.95–1.03) in the post-intervention period. Although a protective effect was observed in most subgroups analysed, especially against the risk of serious or fatal collisions, significant risk reductions were only observed among drivers aged 45 to 64 years old, car drivers on non-urban roads and motorcycle and moped riders on urban roads, and during daytime on weekdays (Table 3).

Injuries prevented

After the reform of the penal code, the number of people prevented from being injured in traffic collisions was consistent with the reduced risk of being involved in injury collisions observed among drivers. However, no protective effect was observed among pedestrians – except for a reduction in the women seriously injured or killed – or among children under 14 years of age.

Over the 25 months that followed the intervention, the number of men injured was 7.2% lower than the number expected to be injured had the penal code not been reformed (P < 0.01). Among women, the number injured was 3.0% lower (P = 0.241) (Table 4).

Table 4. Number of people prevented from being injured after the post-intervention period and per cent change with respect to the expected number, by injury severity, type of road user, road type, and time of collision, Spain, 2000–2009.

| Men |

Women |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All injured people |

Seriously or fatally injured people |

All injured people |

Seriously or fatally injured people |

||||||||

| No. Preventeda | % changeb | No. Preventeda | % changeb | No. Preventeda | % changeb | No. Preventeda | % changeb | ||||

| Overall | 13 891** | 7.2 | NA | NA | 3 230 | 3.0 | NA | NA | |||

| Injury severity | |||||||||||

| Slight | 10 032** | 6.3 | NA | NA | 2 424 | 2.5 | NA | NA | |||

| Serious | 3 361*** | 12.0 | NA | NA | 856* | 8.4 | NA | NA | |||

| Fatal | 680** | 13.7 | NA | NA | 100 | 8.0 | NA | NA | |||

| Age (years) | |||||||||||

| 0–13 | −284c | −5.6 | −27 | −4.4 | 428 | 9.0 | 46 | 9.8 | |||

| 14–15 | 385** | 16.0 | 75 | 16.8 | 196* | 13.1 | 7 | 4.0 | |||

| 16–17 | 1 238*** | 17.3 | 182* | 14.8 | 170 | 5.6 | 48 | 13.4 | |||

| 18–29 | 7 732*** | 12.0 | 1 979*** | 19.2 | 1 624 | 4.9 | 506** | 16.0 | |||

| 30–44 | 6 560*** | 10.6 | 1 961*** | 17.8 | 1 029 | 3.5 | 333* | 12.2 | |||

| 45–64 | 2 563*** | 7.9 | 651** | 10.5 | 1 163* | 6.1 | 229 | 9.7 | |||

| 65–74 | −53 | −0.8 | 56 | 3.7 | −215 | −4.8 | −73 | −9.2 | |||

| 75+ | −18 | −0.3 | −71 | −5.5 | −79 | −2.0 | −17 | −1.6 | |||

| Type of road user | |||||||||||

| Car user | 7 668** | 8.4 | 1 352** | 11.1 | 3 685 | 5.3 | 413 | 7.0 | |||

| Motorcycle user | 8 787*** | 21.4 | 2 233*** | 25.4 | 1 612*** | 19.8 | 160 | 18.6 | |||

| Moped user | 4 014*** | 16.3 | 735*** | 18.3 | 1 230*** | 12.8 | 174* | 19.8 | |||

| Pedestrians | 208 | 1.8 | 253 | 8.3 | 390 | 3.3 | 286* | 10.7 | |||

| Road type | |||||||||||

| Urban | 5 964* | 6.9 | 1 069** | 11.3 | 637 | 1.3 | 253 | 6.3 | |||

| Non-urban | 17 555*** | 16.3 | 4 098*** | 17.5 | 6 845** | 11.9 | 902** | 12.5 | |||

| Time of collision | |||||||||||

| Daytime weekday | 13 769*** | 13.3 | 2 350*** | 15.4 | 5 480** | 8.9 | 351 | 6.2 | |||

| Night-time weekday | 3 703** | 13.6 | 806** | 17.0 | 1 248* | 9.7 | 153 | 11.3 | |||

| Daytime weekend | 3 823* | 11.2 | 1 384** | 19.2 | 585 | 3.1 | 416* | 16.3 | |||

| Night-time weekend | 2 760* | 9.4 | 709* | 12.4 | 506 | 3.6 | 240 | 14.2 | |||

NA, not applicable; *P < 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

a Pre-intervention period: 1 January 2000 to 30 November 2007; post-intervention period: 1 December 2007 to 31 December 2009.

b Calculated by comparing the number of people injured with the number expected to be injured after the intervention.

c Negative numbers indicate that the people injured after the intervention exceeded the expected number.

The greatest number of people prevented from being injured was observed among men, individuals aged 14 to 30 years and motorcycle or moped users.

Discussion

Regulation of traffic behaviour is an essential component of road safety policy and imposing strict penalties for traffic offences can increase the deterrent effect of the law. The present study shows a reduction in both the number of drivers involved in injury collisions and the number of people injured in traffic collisions following the reform of the penal code in Spain. Greater reductions were observed among young male drivers, especially those riding motorcycles and mopeds. This may be, at least to some extent, because men and young drivers tend to engage in the riskier behaviours that were criminalized by the reformed penal code.20,21 Since females and older drivers are generally more compliant road users, the stricter penalties imposed for violating traffic laws are less likely to reduce their risk of being involved in traffic collisions than the risk among less compliant drivers.

The greater risk reductions observed among motorcycle and moped riders could be due in part to the generally younger age of these road users and to the fact that riders of powered two-wheel vehicles, especially mopeds, tend to be less compliant with road safety legislation.22 In addition, greater risk reductions were observed on non-urban roads perhaps because compliance with the speed limit and with laws against driving while intoxicated, both included among the criminalized behaviours, is lower on these roads than on urban roads.

Comparison with previous studies

No previous studies have assessed the effect of criminalizing multiple traffic behaviours on the rates of traffic injuries. However, several authors have evaluated the effect of criminalizing drunk driving, one of the behaviours included in the reform of the penal code in Spain. The findings vary greatly; they range from no effect to a 73% reduction in the number of alcohol-related collisions attributable to this measure. In Canada, where the legal blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limit is 0.05 g/l, an 18% decrease was observed in the number of fatally injured drunk drivers after the criminal law was passed.14 In Taiwan (China) where the BAC limit is 0.05 g/l, a 72.6% reduction in the number of collisions in which drivers had a positive alcohol breath test was observed.10 Studies in the United States of America (BAC limit 0.08 g/l) have shown lower reductions – 6%,13 5%11 and none12 – in the number of alcohol-related fatalities after the criminalization of drunk driving, perhaps because the use of several variables for criminal law in the study models could have confounded the real effect of the measure due to correlation. Finally, in Norway, where the BAC limit is 0.02 g/l, and in Sweden, where the BAC limit is 0.02 g/l, the number of traffic fatalities did not increase after criminal laws were attenuated.15 However, the authors did not analyse alcohol-related injuries or adjust for the effect of coexisting laws aimed to reduce drunk driving.

The results of these studies suggest that criminalizing drunk driving, as was done in Spain (BAC limit 0.05 g/l), can reduce alcohol-related crashes. This is consistent with the results of the present study. The smaller effect observed in Spain compared with other countries may be explained by the fact that much of the reduction in traffic injuries observed in recent years as a result of the prioritization of road safety and the penalty points system was already adjusted for in the models. Thus, the burden of traffic injuries, especially serious ones, has followed a downward trend in Spain since 2004, and the criminalization of certain traffic behaviours has prompted a further reduction. The effect is particularly evident among motorcycle riders, whose risk was the least affected by previous road safety interventions.4,5

Limitations and strengths

Since the intervention was nationwide, we had no comparison group. However, such a group is not essential in time–series analyses, although it can strengthen the evidence, because per cent changes are compared between time points in the same series.19 We controlled for time trend, seasonality, fuel consumption and previous road safety interventions. We included time trends in the analyses to account for changes in potential confounders, such as improvements in vehicle safety or in road behaviour, throughout the study period. To control for changes in exposure, we adjusted for national fuel consumption in the models, but we assumed that mobility changed uniformly during the study across age, sex, and user-type subgroups. We did not use the number of kilometres travelled by all vehicles because it was only available for non-urban roads. The number of vehicles registered would not have accurately captured changes in mobility; whereas this number increased steadily, fuel consumption suddenly dropped during 2008–2009. This is not likely to have resulted from greater vehicle efficiency, which would have involved a gradual change, but the economic crisis could explain it. Moreover, the number of kilometres travelled on non-urban roads showed a similar reduction.

Although Spain is currently experiencing a serious economic crisis, we believe that its influence on the results of the present study is small, as an analysis of the data up to 2008 (data not shown), when the crisis had barely begun to exert its negative effects, yielded similar findings.

The methods we used did not allow us to determine what fraction of the observed effectiveness was attributable to the reformed penal code or to the stricter enforcement of traffic laws that accompanied the reform. Both probably had an impact, since a law is only effective to the degree to which it is enforced.23 In Spain, the enforcement of traffic laws has been prioritized since 2004. After the reform of the penal code, the number of prosecutions, most of them for driving without a licence and or driving while intoxicated, increased from 43 296 in 2007 to 87 755 in 2008.

Although we were unable to separately analyse the effect of each of the road behaviours penalized, we assessed the overall effect of the reform of the penal code both on drivers, who represent the law’s target population, and on those injured in traffic collisions, who represent the Spanish population at large.

We used Poisson regression models, which yield estimates similar to those obtained with autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models and with similar goodness of fit. This allowed us to calculate RRs, which permit a straightforward interpretation of the intervention’s effectiveness.24,25

Moreover, the large sample size allowed us to stratify the analysis by relevant variables such as age, sex, type of road user, road type and time of collision. Finally, the long pre-intervention period provided analytical stability.

Conclusion

The results of the present study suggest that criminalizing certain road traffic behaviours can effectively improve road safety by reducing both the number of drivers involved in injury collisions and the number of people injured in traffic collisions. These findings can probably be generalized to other countries that have efficient road traffic administration and that prioritize traffic law enforcement.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Pilar Zori, Fernando Ruiz Cuevas and Marc Marí for their valuable contributions. This paper is part of Ana M Novoa’s doctoral dissertation at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain.

All authors are affiliated with the Institute of Biomedical Research (IIB Sant Pau); Ana M Novoa also works with the PhD Programme in Biomedicine in the Universitat Pompeu Fabra; Carme Borrell, Catherine Pérez and Elena Santamariña also work with the CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP) and Carme Borrell also works with the Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Funding:

This work was partially supported by the Agencia Española de Tecnologías Sanitarias (Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica, Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III-Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fomento de la Investigación) [PI07/90157] and by the Intensificación de la Actividad Investigadora (Carme Borrell) programme, funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya. The views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Agencia Española de Tecnologías Sanitarias, the Instituto Carlos III or the Departament de Salut.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Dirección General de Tráfico. Ministerio de Interior. Anuario estadístico de accidentes 2008 Madrid: Dirección General de Tráfico; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dirección General de Tráfico. Ministerio de Interior. Plan estratégico de seguridad vial 2005-2008: medidas especiales de seguridad vial 2004-2005. Madrid: Dirección General de Tráfico; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dirección General de Tráfico. Ministerio de Interior. Plan estratégico de seguridad vial 2005-2008: plan de acciones estratégicas claves 2005-2008. Madrid: Dirección General de Tráfico; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novoa AM, Pérez K, Santamariña-Rubio E, Marí-Dell’Olmo M, Cozar R, Ferrando J, et al. Road safety in the political agenda: the impact on road traffic injuries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:218–25. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.094029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novoa AM, Pérez K, Santamariña-Rubio E, Marí-Dell’Olmo M, Ferrando J, Peiró R, et al. Impact of the penalty points system on road traffic injuries in Spain: a time-series study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2220–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.192104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaal D. Traffic law enforcement: a review of the literature (Report No. 53). Monash University Accident Research Centre; 1994.

- 7.Peden M, Scurfield R, Sleet D, Mohan D, Hyder AA, Jarawan E, et al., editors. World report on road traffic injury prevention Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Global status report on road safety: time for action Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodríguez JI. Balance de 3 años del permiso por puntos. Tráfico y Seguridad Vial. 2009;196:12–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang HL, Yeh CC. The life cycle of the policy for preventing road accidents: an empirical example of the policy for reducing drunk driving crashes in Taipei. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36:809–18. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villaveces A, Cummings P, Koepsell TD, Rivara FP, Lumley T, Moffat J. Association of alcohol-related laws with deaths due to motor vehicle and motorcycle crashes in the United States, 1980–1997. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:131–40. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan FA, Stout E, Liang L. Civil liability, criminal law, and other policies and alcohol-related motor vehicle fatalities in the United States: 1984–1995. Accid Anal Prev. 2000;32:723–33. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(99)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagenaar AC, Maldonado-Molina MM, Erickson DJ, Ma L, Tobler AL, Komro KA. General deterrence effects of U.S. statutory DUI fine and jail penalties: long-term follow-up in 32 states. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39:982–94. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asbridge M, Mann RE, Flam-Zalcman R, Stoduto G. The criminalization of impaired driving in Canada: assessing the deterrent impact of Canada’s first per se law. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:450–9. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross HL, Klette H. Abandonment of mandatory jail for impaired drivers in Norway and Sweden. Accid Anal Prev. 1995;27:151–7. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(94)00047-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunkel SR, Atchley RC. Why gender matters: being female is not the same as not being male. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12:294–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yannis G, Antoniou C, Papadimitriou E. Road casualties and enforcement: distributional assumptions of serially correlated count data. Traffic Inj Prev. 2007;8:300–8. doi: 10.1080/15389580701369241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stolwijk AM, Straatman H, Zielhuis GA. Studying seasonality by using sine and cosine functions in regression analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:235–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.4.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langbein LI, Felbinger CL. The quasi experiment. In: Langbein LI. Public program evaluation: a statistical guide New York: ME Sharpe; 2006. pp.106-33. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fergusson D, Swain-Campbell N, Horwood J. Risky driving behaviour in young people: prevalence, personal characteristics and traffic accidents. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003;27:337–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2003.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner C, McClure R. Age and gender differences in risk-taking behaviour as an explanation for high incidence of motor vehicle crashes as a driver in young males. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2003;10:123–30. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.3.123.14560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Tráfico G. Observatorio General de Seguridad Vial. Uso del casco en conductores y acompañantes de vehículos a motor de dos ruedas Madrid: Investigación, Marketing e Informática; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beltramino JC, Carrera E. El respeto a las normas de tránsito en la cuidad de Santa Fe, Argentina. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007;22:141–5. doi: 10.1590/S1020-49892007000700009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tobías A, Díaz J, Saez M, Alberdi JC. Use of poisson regression and box-jenkins models to evaluate the short-term effects of environmental noise levels on daily emergency admissions in Madrid, Spain. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:765–71. doi: 10.1023/A:1015663013620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhn L, Davidson LL, Durkin MS. Use of Poisson regression and time series analysis for detecting changes over time in rates of child injury following a prevention program. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:943–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]