Abstract

A naturally occurring mutation in follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) gene has been reported: an amino acid change to glycine occurs at a conserved aspartic acid 550 (D550, D567, D6.30567). This residue is contained in a protein kinase-CK2 consensus site present in human FSHR (hFSHR) intracellular loop 3 (iL3). Because CK2 has been reported to play a role in trafficking of some receptors, the potential roles for CK2 and D550 in FSHR function were evaluated by generating a D550A mutation in the hFSHR. The hFSHR-D550A binds hormone similarly to WT-hFSHR when expressed in HEK293T cells. Western blot analyses showed lower levels of mature hFSHR-D550A. Maximal cAMP production of both hFSHR-D550A as well as the naturally occurring mutation hFSHR-D550G was diminished, but constitutive activity was not observed. Unexpectedly, when 125I-hFSH bound to hFSHR-D550A or hFSHR-D550G, intracellular accumulation of radiolabeled FSH was observed. Both sucrose and dominant-negative dynamin blocked internalization of radiolabeled FSH and its commensurate intracellular accumulation. Accumulation of radiolabeled FSH in cells transfected with hFSHR-D550A is due to a defect in degradation of hFSH as measured in pulse chase studies, and confocal microscopy imaging revealed that FSH accumulated in large intracellular structures. CK2 kinase activity is not required for proper degradation of internalized FSH because inhibition of CK2 kinase activity in cells expressing hFSHR did not uncouple degradation of internalized radiolabeled FSH. Additionally, the CK2 consensus site in FSHR iL3 is not required for binding because CK2alpha coimmunoprecipitated with hFSHR-D550A. Thus, mutation of D550 uncouples the link between internalization and degradation of hFSH.

Keywords: CK2, endosome, follicle-stimulating hormone, FSH, FSH receptor, lysosome, mechanisms of hormone action

Aspartic acid 550 in FSH receptor plays a role in FSH degradation following internalization.

INTRODUCTION

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates follicle growth and development in ovaries and is critical for maximal mature spermatozoa production [1, 2]. The FSH receptor (FSHR) is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) expressed in ovarian granulosa cells and testicular Sertoli cells [3, 4]. Upon FSH binding, FSHR signaling is mediated by the downstream effector Gαs, which activates adenylyl cyclase, resulting in increased cAMP levels [5–8]. Comparison of the crystal structures of resting and activated GPCRs demonstrated that agonist binding activates the receptor through conformational changes in the transmembrane regions 5 and 6, causing a shift in intracellular loops 2 and 3 (iL2 and iL3) and subsequent activation and dissociation of Gαs [9]. We have demonstrated that iL2 is a critical component of FSH-induced cAMP production [10]. It was therefore of great interest to determine what role iL3 played in this process.

Classically, two mechanisms underlie signaling control: desensitization, whereby signal is dampened, potentially through phosphorylation of receptor intracellular domains by GPCR kinases (GRKs), and internalization-mediated downregulation, whereby the net number of receptors in the plasma membrane is reduced, resulting in a balance between recycling and degradation [11–14]. Phosphorylation of the FSHR iL1 and iL3 has been shown to enhance internalization [15]. Phosphorylation by GRKs and subsequent arrestin binding are involved in receptor recycling or degradation [16]. Termination of FSHR signaling is mediated in part by the nonvisual arrestins, arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 [17]. Arrestin association has been mapped to iL1 and iL3 on FSHR [18], and deglycosylated gonadotropin exhibits biased signaling at the FSHR due to arrestin-mediated differential activation of ERK [19]. In addition, processes such as ubiquitination play a role in receptor trafficking, and it is noteworthy that FSHR iL3 interacts with ubiquitin isoforms [20]. The GPCRs follow divergent postendocytic pathways such that nuanced trafficking and signaling are anticipated. For example, recycling observed for the β-adrenergic receptor [21, 22] is rapid, resuming position on the cell membrane in minutes. In contrast, the delta opioid receptor [23] and the V2 vasopressin receptor [24] are slowly recycled following distinct clathrin-coated-pit-mediated internalization pathways. The postendocytic degradation and recycling pathways of FSH are lysosomal because lysosomotropic reagents have been found to inhibit FSH degradation in primary cultures of rat Sertoli cells [25, 26]. Yet other studies have demonstrated that in HEK293 cells expressing human FSHR (hFSHR), the majority of the internalized hFSH-hFSHR complex is trafficked to endosomes and subsequently recycled back to the surface, where bound hormone is then dissociated [27].

The hFSHR harbors a predicted protein kinase CK2 consensus site on iL3 at 547S-S-S-D550 (564S-S-S-D567 when the 17-nucleotide leader sequence is included). The negatively charged aspartic acid in this site (D6.30567) has previously been identified as a naturally occurring mutation (D567G) in a male who presented with normal spermatogenesis despite his lack of pituitary gland, and therefore no gonadotropin [28]. Additional studies have demonstrated spermatogenesis in hypogonadal mice harboring a transgene of FSHR with this mutation [29]. Apart from the physiological significance of this residue, further interest was stimulated not only because CK2 phosphorylates proteins involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis, such as arrestin-3 [30], AP-2, and clathrin [31], but also because CK2 interaction with FSHR has been demonstrated [32], and CK2 interacts with a consensus site on the third loop of another GPCR, the muscarinic receptor [33]. In addition, CK2 was shown to negatively regulate Gαs signaling, and inhibition of CK2 resulted in decreased surface receptor internalization in D1 and adenosine A2A receptors, suggesting a linking of the CK2 consensus site with trafficking [34]. Thus, given that CK2 is enriched in clathrin-coated vesicles [35], and that it plays a role in endosome-lysosome shuttling, and given also that FSHR iL3 is implicated in internalization [36], ubiquitination, phosphorylation, and human disease, the present studies sought to determine whether the CK2 consensus site in FSHR iL3 has a role in FSH action. To test the hypothesis that the CK2 consensus site is required for FSHR function, the aspartic acid residue found at position D550 in hFSHR iL3 was changed to alanine (Supplemental Fig. S1, all Supplemental Data are available online at www.biolreprod.org). This substitution was chosen for two reasons. First, the acidic residue in the CK2 consensus sequence is important for electrostatic interactions with basic residues located on the CK2α catalytic subunit [37]. Second, an alanine mutation removes the negative charge but retains the aliphatic side chain, preventing rotation around the alpha carbon backbone, which could otherwise destabilize the receptor, as may take place in the naturally occurring mutation, D550G.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of hFSHR-D550A and hFSHR-D550G

A cDNA clone of hFSHR, generously provided by Ares Advanced Technologies (Randolph, MA) [38], was recloned into pShuttle-CMV (Agilent Technologies). This plasmid was used as a template for mutagenesis (QuikChange II XL Site Directed Mutagenesis kit; Agilent Technologies).

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell line HEK-293T was maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal bovine serum and was cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2. Subconfluent cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corp.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were incubated for an additional 48 h before experiments were performed.

Radioreceptor Assay

HEK-293T cells (ATTC) transiently transfected with 0.8 μg of plasmid encoding mutant and wild-type (WT) hFSHR in 24-well plates were assayed for 125I-hFSHR-specific binding at 37°C as described previously [39], with the following modification. For the displacement-binding assay, cells were transfected as documented in that reference except that cells were incubated in the presence of increasing concentrations of unlabeled pituitary hFSH (0–1000 ng) and an excess of 125I-hFSH for 1 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator.

Cyclic AMP Measurement

The 293T cells were transiently transfected with 0.8 μg of plasmid encoding mutant or WT-FSHR in 24-well plates. Forty-eight hours later, cells were preincubated with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor isobutyl-methyl-xanthine (IBMX; 1 mM) in DMEM for 15 min and were then stimulated with increments of hFSH (0–1000 ng) for 1 h in the presence of IBMX. Total cAMP (lysed cells plus medium) was collected from cells by alternating freeze-thaw cycles (three times) followed by addition of an equal volume of 100% ethanol, and insoluble material was removed by pelleting in a Eppendorf microcentrifuge at 13 000 rpm for 10 min. Using either a commercially available cAMP antibody (Amersham Corp.) or JAD131, which was developed in-house, cAMP was measured by 125I-cAMP displacement radioimmunoassay as previously described [40].

Cell Lysate Preparation and Immunoprecipitation of hFSHR

Cell lysate preparation and immunoprecipitation of hFSHR were performed as previously described [39]. Briefly, 293T cells transiently transfected with either hFSHR-D550A or WT-hFSHR expression plasmids were harvested in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) with protease inhibitor cocktail (10 μg/ml) pepstatin A, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 16 μg/ml benzamide, 10 μg/ml 1,10 phenanthrolene, and 1 mM PMSF, homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer, and centrifuged at 13 000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Pellets were removed, and protein concentrations in the supernatant were determined in a BCA assay (Pierce). The epitope of the anti-hFSHR monoclonal antibody 106.105 used for immunoprecipitation was hFSHR residues 300–315 (317–332 when the 17-nucleotide leader sequence is included) [41]. The specificity control that was used is the same isotype (IgG2b) as the anti-hFSHR antibody and was kindly provided by Dr. Gary Winslow (Wadsworth Center).

Protein Expression Determination by Western Blotting

Detection of hFSHR was carried out with monoclonal antibody 106.105. Rabbit anti-hemagglutinin (HA) tag (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions) was used to detect CK2α-HA [42]. Five micrograms of protein obtained from supernatants of cellular lysates was heated to 60°C for 10 min and loaded on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and electrophoresed, first at 85 V for 30 min, and then at 120 V for 1 h. Proteins in minigels were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore) using a semidry transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad). Following transfer, membranes were rinsed in TBST (100 mM Tris-HCl, 0.9% NaCl, 0.5% Tween 20) and blocked in 5% milk-TBST for 1 h (room temp) or overnight (4°C). After washing in TBST, membranes were incubated in primary antibody diluted in 5% milk-TBST, either overnight at 4°C or for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed again in TBST, then incubated for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen Corp.) diluted in 5% milk-TBST. After a final wash, membranes were visualized with Supersignal West Pico ECL according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce), then exposed on x-ray film (Eastman Kodak) to detect fluorescence of the product, or were imaged and quantitated using Image Reader LAS and Image Gauge 4.0 software (Fujifilm). Arbitrary units (AUs) for individual bands and background (BG) were determined, and relative intensities (RIs) of hFSHR-D550A and WT-hFSHR were determined using Prism (GraphPad Software) and the following equation: RI = [FSHR (AU − BG)/mm2]/[Actin (AU – BG)/mm2].

Determination of Internalization, Recycling, and Degradation

Forty-eight hours following transfection (see above), cells were incubated in the presence of excess (300 000 cpm) 125I-hFSH. After 1 h, 125I-hFSH was removed, monolayers were washed twice with cold PBS, and surface-bound hormone was eluted in cold isotonic pH 3.0 buffer on ice. In pulse chase experiments, cells were washed twice again with cold PBS to remove unbound radiolabeled hFSH, and medium containing 1 μg of unlabeled hFSH was added to each well. At each time point, medium was removed for trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation. Then cell surface-bound 125I-hFSH was eluted as above, followed by lysis with 2 N NaOH to determine internalized radiolabeled hFSH. At t = 0, cold hormone was immediately removed, surface-bound 125I-hFSH was eluted, and cell-associated 125I-hFSH was released by 2 N NaOH lysis. Cell-associated radioactivity at this time point represents “initial 125I-hFSH internalized” that is used for relative comparisons at later time points. The TCA-soluble radioactivity represents degraded 125I-hFSH, and TCA insoluble radioactivity represents internalized and recycled 125I-hFSH. These two values were determined by addition of an equal volume of 20% TCA to medium collected during the second incubation, in which an excess of unlabeled hFSH was present. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 30 min. To the pellets was added 10% TCA, and then tubes were spun again, supernatant was removed, and the radioactivity in pellets, supernatants, and washes was determined in a Wallac Gamma counter. The radioactivity determined in the wash supernatant was added to radioactivity determined in the supernatant (TCA-soluble) fractions. The total recycled 125I-hFSH represents the summation of surface-eluted 125I-hFSH and TCA-insoluble material at each time point.

In some experiments it was desired to inhibit internalization of radiolabeled FSH. Two approaches were used. In one approach, cells were incubated with 0.45 M sucrose in DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum for 1 h prior to and during 125I-hFSH incubation in serum-free DMEM. An additional approach used dominant-negative dynamin expression to inhibit internalization [43].

Confocal Microscopy

Single-chain FSH (scFSH) [44] and monoclonal antibody 106.105 were labeled with Alexa 488 and Alexa 555, respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen Corp.). HEK-293T cells were transfected with either hFSHR-D550A or WT-hFSHR as described above and were used 48 h later. The cells were incubated with 1 μg of scFSH-Alexa 488 for 1 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 in serum-free medium. Cells were subsequently washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were washed again with PBS and permeabilized with 0.01% saponin-5% bovine serum albumin for 30 min at room temperature. Human FSHR was detected by incubation with anti-hFSHR monoclonal antibody 106.105-Alexa 555 for either 2 h at room temperature or 4°C overnight. Images were collected using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope using an HCX PL APO oil immersion 63× objective with numerical aperture 1.4. The fluorescence intensity of each fluorophore was collected sequentially in separate channels (493–538 nm for Alexa 488 and 560–630 nm for Alexa 555) and merged for analysis using ImageJ software. At least 10 transfected cells each were analyzed for WT and hFSHR-D550A.

RESULTS

Characterization of hFSHR-D550A

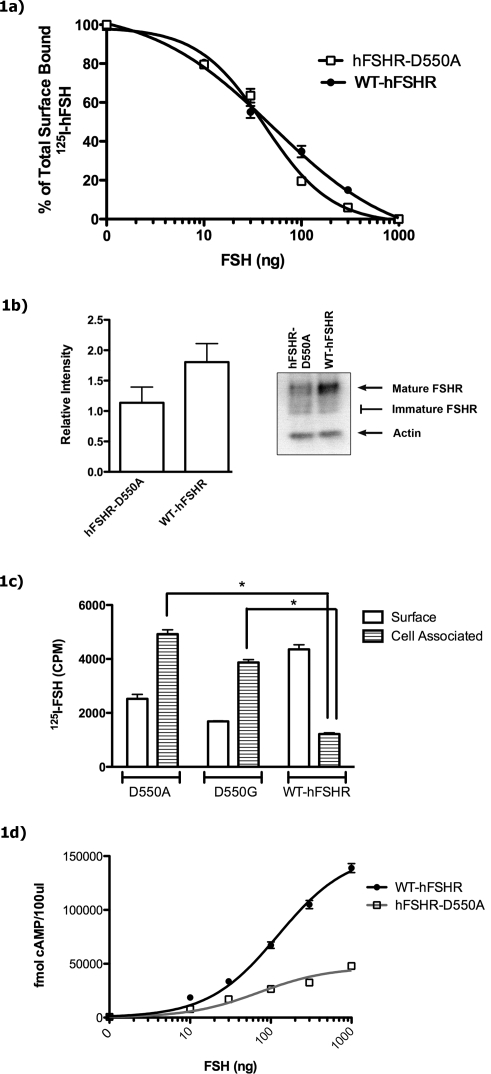

Following transfection of HEK-293T cells with either hFSHR-D550A or WT-hFSHR, an equilibrium-binding radioreceptor assay was carried out at 37°C with a constant amount of 125I-hFSH (generally about 300 000 cpm) and increasing doses of unlabeled hFSH (Fig. 1a). No remarkable differences were noted between the mutant and WT receptor half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values that were observed: hFSHR-D550A IC50 = 50.9 ng of hFSH, and WT-hFSHR IC50 = 42 ng of hFSH. (Repeat experiments confirmed initial findings, for example: hFSHR-D550A IC50 = 84.7 ng of hFSH, and WT-hFSHR IC50 = 75.1 ng of hFSH; data not shown). However, at higher doses of unlabeled hFSH, a greater degree of displacement was observed with the mutant than the WT receptor, suggesting a lower level of mutant expression. In order to assess this point, a Western blot analysis was performed.

FIG. 1.

a) Displacement of surface-bound radiolabeled ligand in hFSHR-D550A transfected and WT-hFSHR transfected cells. Surface binding was analyzed in transfected 293T cells in the presence of increasing amounts of unlabeled hFSH after 1 h of incubation with 125I-hFSH. Free hormone was removed, and surface-bound 125I-hFSH was eluted and quantitated. Human FSHR-D550A half maximal effective concentration (EC50) = 50.9 ng of hFSH, and WT-hFSHR EC50 = 42 ng of hFSH. Data are representative of two experiments performed in triplicate. b) hFSHR-D550A and WT-hFSHR are expressed in transfected 293T cells. Cells were transiently transfected with equal amounts of either mutant or WT-hFSHR DNA. Whole-cell lysate was collected 48 h later, and 5 μg of total protein was applied per lane on an SDS-PAGE gel. Separated proteins were dry blot transferred to Immobilon-P membranes and probed with monoclonal antibody anti-FSHR (106.105). The relative intensity of individual bands was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The Western blot is representative of a typical transfection, with arrows indicating mature hFSHR and actin. Immature hFSHR comprised smaller molecular weight bands and is indicated as a range in the figure. The histogram depicts the mean and SEM of three replicates per construct, which were quantitated from the same transfection as the Western blot shown on the right. c) Cell surface and cell-associated specifically bound 125I-hFSH in 293T cells transfected with either hFSHR-D550A, hFSHR-D550G, or WT-hFSHR. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were incubated with 125I-hFSH for 1 h at 37°C. Nonspecific binding was determined by including 1 μg of unlabeled hFSH in parallel wells. Specific hFSH binding was assessed by removing free hormone, and surface-bound radiolabeled hFSH was eluted and quantitated after adjusting for nonspecific binding. Cells were then lysed, and cell-associated radiolabeled hormone was determined. A significant difference between mutant and WT cell-associated CPM is indicated (*unpaired t-test, P < 0.0001). Experiments were performed five times in triplicate. d) Effect of D550A mutation on FSH induced cAMP production in transfected 293T cells. 293T cells were transfected with equal amounts of hFSHR-D550A or WT-hFSHR. Forty-eight hours later, cells were treated with IBMX for 15 min and were stimulated with hFSH for 1 h. Total cAMP (secreted as well as intracellular) was measured by radioimmunoassay. Bmax for hFSHR-D550A was 46 946 ± 4590 fmol per 100 μl of medium, and Bmax for WT-hFSHR was 153 065 ± 9194 fmol per 100 μl.

Western blot analysis of 5 μg of cell lysate protein indicates that the amount of the 85-kDa species of hFSHR-D550A protein (mature) is lower than that of WT-hFSHR protein (relative intensities are 1.136 ± 0.260 and 1.806 ± 0.304, respectively; Fig. 1b). The 85-kDa form of FSHR is the fraction of cellular FSHR that is expressed at the cell surface [45]. Because 125I-hFSH is internalized when live cells are used in radioreceptor assays conducted at 37°C, it was important to analyze not only 125I-hFSH cell surface binding but also cell-associated (internalized) 125I-hFSH. Thus, HEK-293T cells were transfected with equal amounts of either hFSHR-D550A-encoding or WT-hFSHR-encoding plasmids, and cell surface and cell-associated 125I-hFSH was determined. Although WT-hFSHR bound higher levels of surface 125I-hFSH than did hFSHR-D550A, the level of internalized, cell-associated 125I-hFSH was significantly higher in hFSHR-D550A transfected HEK-293T cells (*unpaired t-test, P < 0.0001) than that detected in WT-hFSHR transfected cells (Fig. 1c).

In addition, an hFSHR-D550G mutation was created to compare the naturally occurring mutation with the hFSHR-D550A mutation. Interestingly, hFSHR-D550G transfected cells display the same pattern of increased cellular accumulation of 125I-hFSH as cells transiently transfected with hFSHR-D550A (Fig. 1c). When stimulated with FSH, hFSHR-D550A transfected cells produced maximal levels of cAMP that were approximately 70% lower than those produced by WT-hFSHR transfected cells (Fig. 1d), in spite of the more modest reduction in surface expression (approximately 37%; Fig. 1b). Similar results were observed with hFSHR-D550G transfected cells (Fig. 2a). The naturally occurring mutation (hFSHR-D550G) that has been described in a hypophysectomized male with normal gonadal function was reported to result in constitutive activation of the FSHR [46]. In that study, basal but not FSH-stimulated cAMP levels were elevated in hFSHR-D550G compared with WT-FSHR. In the present study, total cAMP levels in hFSHR-D550A transfected, hFSHR-D550G transfected, and WT-hFSHR transfected cells exhibited no significant differences prior to hFSH stimulation; neither the hFSHR-D550A nor hFSHR-D550G forms of receptor resulted in detectable constitutive activation (Fig. 2b).

FIG. 2.

Effects of D550A and D550G mutations on baseline and FSH-induced cAMP production in transfected 293T cells. 293T cells were transfected with equal amounts of hFSHR-D550A, hFSHR-D550G-hFSHR, or WT-hFSHR. Forty-eight hours later, cells were treated with IBMX for 15 min and were stimulated with various amounts of hFSH for 1 h. Total cAMP (secreted as well as intracellular) was measured by 125I-cAMP displacement radioimmunoassay. a) The cAMP production over the full range of hFSH stimulation. b) Baseline cAMP production without hFSH stimulation, enlarged from a.

Evaluation of CK2α Interaction with hFSHR-D550A

Because basic residues on CK2α undergo electrostatic interactions with the target protein, it was anticipated that modification of that site would abrogate CK2-FSHR interactions. To test the hypothesis that aspartic acid 550 is essential for the interaction of CK2 with hFSHR a coimmunoprecipitation experiment was carried out. Thus, 293T cells were cotransfected with CK2α-HA and either hFSHR-D550A or WT-hFSHR. After 48 h, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml hFSH or an equivalent amount of medium and allowed to incubate at 37°C for 1 h. Cell monolayers were washed, and cell lysates were prepared.

Both forms of receptor were efficiently precipitated (IP: anti-FSHR) and detected (IB: anti-FSHR) with monoclonal antibody anti-hFSHR 106.105 (Supplemental Fig. S2, a and b).

These results indicate that the aspartic acid at position 550 in the hFSHR CK2 consensus sequence on iL3 either is not required for hFSHR association with CK2α, or that the site is not a CK2α interaction site or is sterically hindered.

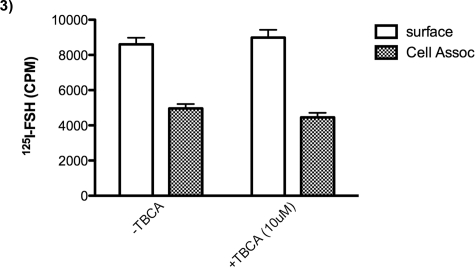

It was desirable to verify this finding mindful of the fact that CK2 has two modes of action: binding as well as catalytic activity. A very specific inhibitor of CK2, TBCA [47], was used to determine whether treatment would result in accumulation of 125I-hFSH in cells expressing WT-hFSHR. The results demonstrate that there is no effect of the CK2 inhibitor on accumulation of 125I-hFSH (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Effects of CK2 inhibition on cell surface binding and internalization of 125I-hFSH. HEK-293T cells were transfected with WT-hFSHR. Forty-eight hours later, cells were incubated with TBCA (10 μM) for 1 h, and after subsequent incubation with125I-hFSH (with or without TBCA), surface binding to 125I-hFSH was analyzed. Free hormone was removed, and cell-associated 125I-hFSH was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The presence of TBCA had no effect on surface binding or internalization of 125I-hFSH.

Determination Whether Increased Cell-Associated 125I-hFSH Requires Internalization

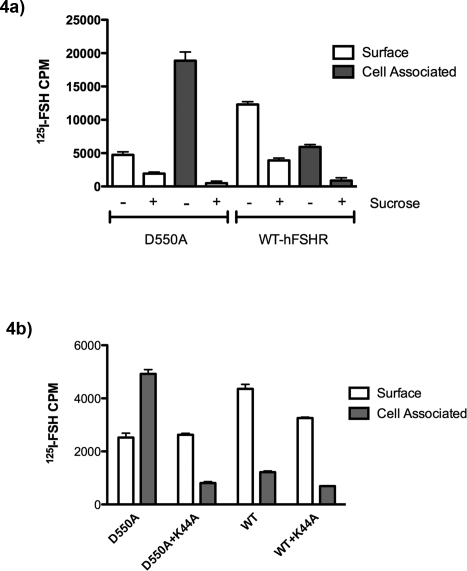

It was possible that the binding of 125I-hFSH to hFSHR-D550A and hFSHR-D550G was irreversible and acid elution did not remove the cell surface radiolabeled hormone, giving an appearance of increased intracellular accumulation. If so, then it would dismiss the possibility that the rate of internalization of the mutant hFSHR was greater than WT FSHR. This possibility was tested in two ways: one using sucrose inhibition of internalization, and the other using a dominant-negative form of dynamin. Hypertonic sucrose is commonly used to destabilize clathrin-coated pits and inhibit clathrin-mediated endocytosis [48]. Thus, transfected cells were preincubated with 0.45 M sucrose for 30 min, and then 125I-hFSH was added to the medium for 1 h; surface-bound labeled hormone was then eluted and quantitated. Cells were subsequently lysed in 2 N NaOH, and cell-associated radiolabeled FSH was determined (Fig. 4a).

FIG. 4.

a) Sucrose inhibits internalization of both hFSHR-D550A and WT-hFSHR. To determine whether 125I-hFSH is internalized via clathrin-mediated vesicles, we incubated transfected 293T cells with 0.45 M sucrose for 30 min before incubation with radiolabeled hormone. After incubation with hormone with or without sucrose for 1 h, surface 125I-hFSH and cell-associated 125I-hFSH were determined as described in Materials and Methods. b) Dominant-negative dynamin inhibits internalization of hFSHR-D550A and WT-hFSHR. To further determine whether cell-associated 125I-hFSH is due to vesicle-mediated internalization, 293T cells were cotransfected with dominant-negative dynamin (K44A) and either WT-hFSHR or hFSHR-D550A. After incubation with hormone for 1 h, surface 125I-hFSH and cell-associated 125I-hFSH were determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Despite reduced surface binding (2.4× for hFSHR-D550A and 3.2× less for WT-hFSHR) in the presence of sucrose, a substantial inhibition of internalization was demonstrated in both hFSHR-D550A (97%) and WT-hFSHR (85%), indicating that internalization is predominantly due to clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Moreover, it was clear that internalization (cell-associated radioactivity) was required for the increased cellular accumulation of 125I-hFSH to be manifested.

Dynamin is required for endocytosis and is primarily involved in scission of newly formed vesicles (e.g., clathrin-coated vesicles). A dominant-negative dynamin [43], K44A, has previously been used to inhibit receptor internalization. When K44A is cotransfected with D550A or WT hFSHR, a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in cell-associated CPM is observed (Fig. 4b). That result further corroborates the findings with sucrose inhibition of 125I-hFSH internalization. Taken together, the data firmly demonstrate that increased cellular accumulation of 125I-hFSH is dependent on active internalization, which is associated with vesicle formation.

Comparison of Internalization of hFSHR-D550A and WT-hFSHR under Nonequilibrium and Equilibrium Conditions

Increased cellular accumulation of 125I-hFSH could be due to an increase in the rate of internalization of hFSHR-D550A compared with WT-hFSHR. When 125I-hFSH surface binding and internalization at 37°C were measured in hFSHR-D550A transfected or WT-hFSHR transfected cells under nonequilibrium conditions, hFSHR-D550A surface binding reached a relative maximum within 5 min and increased only slightly, whereas the WT-hFSHR-bound 125I-hFSH level continued to increase over the course of the 50 min (Fig. 5a). This finding is consistent with a higher level of expression of the mature form of WT-hFSHR compared with hFSHR-D550A. Higher levels of 125I-hFSH accumulated in mutant transfected cells over time than in WT transfected cells, suggesting that the internalization rate was greater for hFSHR-D550A than for WT-hFSHR (Fig. 5b). However, this observation could also be caused by a failure to degrade and excrete internalized 125I-hFSH. Therefore, the disappearance of 125I-hFSH from the cell membrane was determined following equilibrium binding.

FIG. 5.

125I-hFSH binding to hFSHR-D550A and WT-hFSHR under nonequilibrium conditions. a) 293T cells were transfected with either mutant or WT-hFSHR, and surface binding to 125I-hFSH was analyzed under nonequilibrium conditions at time points of 0, 5, 10, 20, and 50 min. b) Free hormone was removed, and cell-associated 125I-hFSH was measured as described in Materials and Methods.

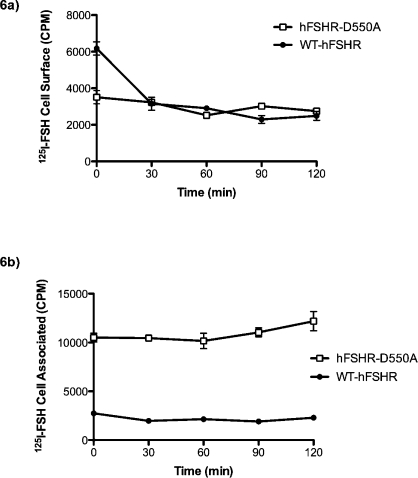

In order to determine whether accumulation of 125I-hFSH in cells expressing hFSHR-D550A was due to an increase in internalization rate, the rate of disappearance of receptor from the cell surface was analyzed following equilibrium binding at 37°C. Cells transfected with either WT or mutant FSHR were allowed to bind radiolabeled hormone for 1 h. After 1 h, medium containing unbound radiolabeled hormone was removed and replaced with fresh medium. Levels of surface and cell-associated radiolabeled hormone were determined at the indicated times (Fig. 6). Surface and cell-associated levels of hFSHR-D550A-bound 125I-hFSH remained essentially unchanged over the 120-min period, whereas surface levels of WT-hFSHR-bound 125I-hFSH decreased approximately 50% within 30 min of 125I-hFSH removal and remained relatively unchanged thereafter (Fig. 6a). As expected, total cell-associated levels of 125I-hFSH were significantly higher in hFSHR-D550A transfected than in WT-hFSHR transfected cells (Fig. 6b). However, the levels of cell-associated 125I-hFSH remained unchanged in transfected cells expressing either form of the receptor, preventing assessment of clearance rates following equilibrium binding.

FIG. 6.

Under equilibrium conditions, cells were incubated with 125I-hFSH for 1 h at 37°C. After 1 h, free hormone was removed and was replaced with medium without hormone. Surface-bound radiolabeled hFSH (a) and cell-associated radiolabeled hFSH (b) were determined as described in Materials and Methods at the time points indicated.

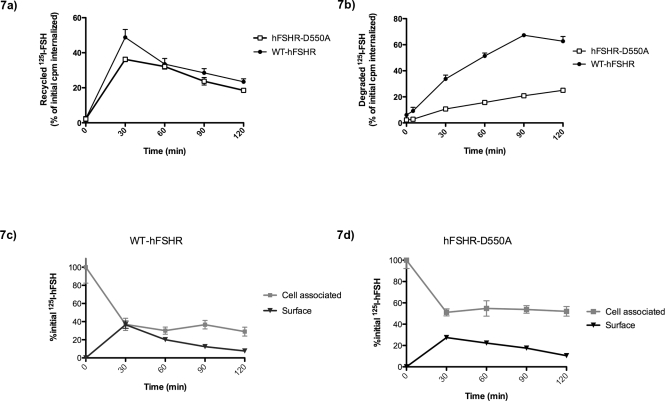

Increased cellular accumulation of FSH in hFSHR-D550A transfected cells may be due to a defect in endosome-lysosome shuttling. In order to test the hypothesis that internalized 125I-hFSH-hFSHR-D550A complexes are not being transported to lysosomes and degraded, a pulse- chase experiment was performed. It is important to consider both the surface-bound receptor complex as well as complexes released into the media for recycling and degradation analysis; therefore, TCA was used to precipitate nondegraded 125I-hFSH from the medium. 125I-hFSH binding was allowed to proceed for 1 h; medium was then removed, cell layers were washed to remove residual labeled hormone, and surface and cell-associated 125I-hFSH levels were measured as before. Cell-associated levels after 60 min (t = 0) are used as baseline values against which subsequent measurements are normalized (initial CPM internalized in Fig. 7). At t = 0, cells were incubated with an excess (1 μg) of unlabeled hFSH for 2 h more. At various time points during the 2-h incubation, medium was removed and saved for TCA analysis, and surface and cell-associated levels of 125I-hFSH were determined. In this manner, it was possible to determine the relative levels of total recycled 125I-hFSH (the sum of TCA-insoluble radioactivity in the medium and surface-bound radioactivity; Fig. 7a) and degraded (TCA-soluble radioactivity in the medium; Fig. 7b). Human FSHR-D550A transfected cells appear to recycle internalized 125I-hFSH as efficiently as WT-hFSHR transfected cells after 120 min (19% and 23%, respectively; Fig. 7a). Human FSHR-D550A transfected 293T cells do not degrade and export internalized hormone as efficiently as WT-hFSHR transfected cells. At the end of the 120-min incubation, only 25% of internalized 125I-hFSH was degraded and released in hFSHR-D550A transfected cells, compared with 62% of internalized 125I-hFSH in the WT-hFSHR transfected cells (Fig. 7b). Thus, the mutation hFSHR-D550A results in deficient degradation of 125I-hFSH. Not surprisingly, ∼52% of 125I-hFSH remained in hFSHR-D550A transfected cells, compared with ∼29% of initially internalized 125I-hFSH in WT-hFSHR transfected cells (Fig. 7, c and d, cell associated). In contrast, disappearance of 125I-hFSH from the cell surface was similar for both receptor types (Fig. 7, c and d, surface-eluted radioactivity).

FIG. 7.

Degradation and recycling of internalized 125I-hFSH in hFSHR-D550A transfected and WT-hFSHR transfected cells. Transfected cells were incubated with 125I-hFSH for 1 h. After 1 h, 125I-hFSH was removed, surface-bound 125I-hFSH was eluted, and cell-associated (internalized) 125I-hFSH was determined. A second incubation was performed in fresh medium containing an excess of unlabeled hFSH, to prevent any rebinding or internalization of 125I-hFSH. In this manner, the fate of the internalized 125I-hFSH over a time course of 120 min was determined. At each time point, medium was removed, and the levels of TCA-soluble (degraded), TCA-insoluble (recycled), surface-bound (recycled), and cell-associated levels of 125I-hFSH were determined. All data were normalized to the value of CPM internalized after the first 1-h incubation with 125I-hFSH. At t = 0, almost all of the 125I-hFSH was cell associated; this situation corresponds to almost no recycling or degradation at this time. At later time points, internalized 125I-hFSH is shown to be recycled to the cell surface, released from the cell as degraded FSH, or released as intact FSH back into the medium for both hFSHR-D550A transfected and WT-hFSHR transfected 293T cells.

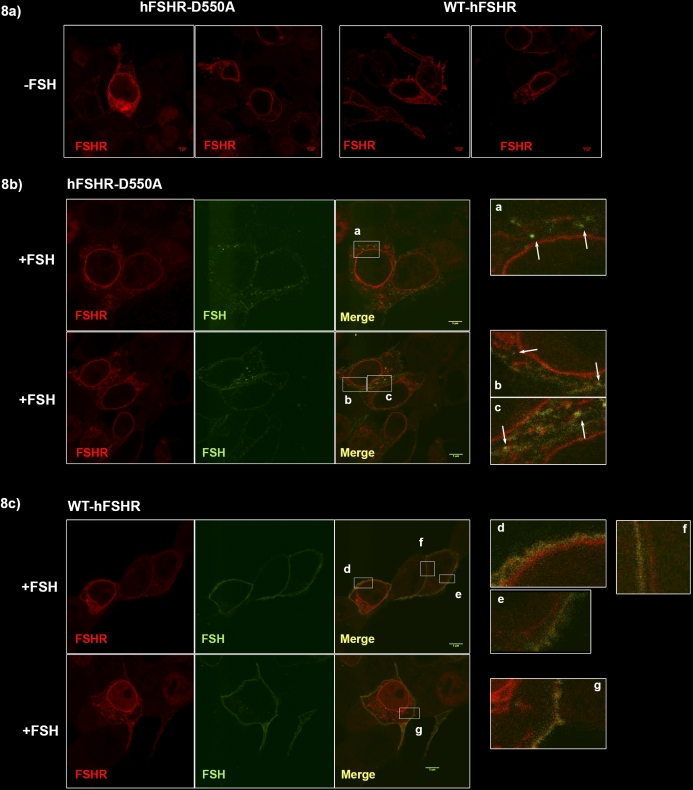

To confirm this biochemical finding, confocal microscopy was used to visualize hFSHR and FSH in cells following equilibrium binding. HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with either hFSHR-D550A or WT-hFSHR, then incubated with 1 μg of scFSH-Alexa 488 for 1 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and probed for total FSHR using monoclonal anti-FSHR-Alexa 555. Prior to addition of scFSH, hFSHR-D550A and WT-hFSHR are apparent both at the surface membrane and internally, presumably on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) surrounding the nucleus and also on the ER distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 8a). After 1 h, hFSHR-D550A transfected cells demonstrate discrete accumulations of scFSH-Alexa 488 within the cytoplasm that are near but distinct from the plasma membrane (Fig. 8b). In contrast, WT-hFSHR transfected cells appear to lack these discrete accumulations, and most scFSH-488 appears to be localized to the plasma membrane (Fig. 8c). Not surprisingly, surface binding of scFSH-Alexa 488 after 1 h is visibly reduced in hFSHR-D550A compared with WT-hFSHR transfected cells. Indeed, it is difficult to distinguish distinct surface scFSH and hFSHR-D550A costaining at the cell membrane (Fig. 8b, merge), whereas clear overlap is apparent between scFSH and WT-hFSHR at the surface membrane (Fig. 8c, merge).

FIG. 8.

Accumulation of scFSH in hFSHR-D550A transfected 293T cells. Transiently transfected 293T cells were stimulated with 1 μg of scFSH-Alexa 488 for 1 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and probed for hFSHR using monoclonal anti-hFSHR-Alexa 555. Imaging was performed on a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope. Each fluorophore was collected sequentially in separate channels and merged for analysis. Images are representative of at least 10 cells per construct. a) WT-hFSHR and hFSHR-D550A localization prior to addition of scFSH. Both panels for each construct depict representative cells under the same conditions. Fluorescently labeled scFSH can be seen in both hFSHR-D550A transfected (b) and WT-hFSHR transfected (c) cells indicated in FSH, merged, and the enlarged panels. Most of the bound scFSH appears as surface-bound hormone in WT-hFSHR cells (c), whereas discrete accumulations, indicated by white arrows, are evident in hFSHR-D550A cells (b). Bars = 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

Interest in the CK2 consensus site (residues 547SSSD550) in iL3 of the human FSHR was engendered because the kinase activity of CK2 has been implicated in GPCR receptor phosphorylation [33], clathrin-mediated endocytosis [31], phosphorylation of β-arrestin [30], endocytic trafficking [49], and regulation of exocytosis [50]. Kinase activity is not the sine qua non of CK2 interaction with target proteins because inactive CK2 has been shown to be associated with intact clathrin-coated vesicles. When clathrin dissociates, CK2 again becomes active. CK2-mediated phosphorylation of arrestin-3 is in part responsible for internalization of the β2-adrenergic receptor [30]. However, specific inhibition of CK2 kinase activity in our hands did not recapitulate the accumulated internalized hormone phenotype of hFSHR-D550A, nor did it inhibit internalization. These results clearly demonstrate that CK2 kinase activity has no role in these functions of FSHR.

The naturally occurring mutation (D550G), also referred to as D567G, has been reported in a hypophysectomized male with normal spermatogenesis, despite undetectable levels of serum gonadotropin [28]. Transgenic mice generated harboring the D567G mutation (TgFSHR-D567G) or hFSHR (TgFSHR-WT) on a gonadotropin-deficient background have been evaluated [46]. In that study, cultured TgFSHR-D567G Sertoli cells showed higher levels of FSH-independent cAMP levels, but not FSH-dependent cAMP levels, compared with Sertoli cells from animals harboring the TgFSHR-WT transgene, reaffirming the constitutive active receptor phenotype.

In the present study, neither hFSHR-D550G nor hFSHR-D550A evidenced detectable constitutive second messenger cAMP activation (independent of FSH stimulation). This was not unexpected, because the original report of this mutation showed only a 1.5-fold increase in basal activity [28]. Maximum FSH-induced cAMP production was 69% lower in hFSHR-D550A than in WT-hFSHR transfected cells. This effect is likely in part due to decreased cell surface hFSHR-D550A compared with WT-hFSHR; however, hFSHR-D550A surface expression was only 37% lower than WT-hFSHR in the same experiment (Fig. 1b). As such, the data suggest that receptor recycling/localization is a novel regulatory mechanism for cAMP production/attenuation.

Mutation of aspartic acid to alanine (D550A) in hFSHR iL3 results in an increase in accumulation of internalized hormone that is caused by a decrease in hormone degradation but normal total recycling of the hormone or receptor/hormone complex (Fig. 7). Less 125I-hFSH is degraded and released from hFSHR-D550A transfected cells than from WT-hFSHR transfected cells, indicating that one or more degradation pathways are defective. Imaging studies (Fig. 8) support the biochemical findings demonstrating an accumulation of FSH in mutant cells (Fig. 7b); however, any bound hormone recycled and released into the medium will be lost and unaccounted for in imaging experiments. The only accurate assessment of recycling and degradation must include these data as in Figure 7. The defect and deficiency could be due to flaws in sequence-directed trafficking of the internalized receptor to the lysosome for degradation, as has been demonstrated in a truncated LHR mutant (t682) that lacked recycling motifs normally found in the C-terminus [51]. The phenotype of D550A more closely resembles the phenotype of the constitutively active LHR mutant L457R [51], where little degradation of internalized hormone is observed and where an increase in intracellular hormone is seen. In terms of recycling, the D550A mutant again resembles constitutively active L457R LHR. For both mutants, total hormone recycled (includes surface receptor-bound hormone as well as hormone bound to receptor and released from the receptor into the medium, undegraded) is similar to the total recycling seen for the WT receptor. The LHR-L457R mutant is not trafficked to lysosomes for degradation, but rather remains in the endosome. Indeed, hFSHR-D550A transfected cells demonstrate accumulated scFSH in discrete areas within the cytoplasm that resemble vesicular structures and are lacking in WT-hFSHR transfected cells (Fig. 8).

Although it is well documented that the fate of internalized GPCRs is determined to a large extent by sequences in the receptor C-terminal tail [52, 53], the current findings are the first evidence that sequences located on iL3 of the hFSHR influence degradation and recycling of the internalized hormone-receptor complex. Previous C-tail truncation studies have identified the last eight residues of the rat FSHR and hFSHR in routing of the internalized hormone-receptor complex. In those studies, truncated FSHR evidenced a decrease in recycling with a concomitant increase in degradation [27]. Present results add to the above findings and indicate that total recycling of 125I-hFSH (either complexed with receptor or alone) in hFSHR-D550A transfected cells is not altered from the WT-hFSHR process (Fig. 7a), yet 125I-hFSH accumulates and degradation is significantly reduced (Figs. 7b and 8). This pattern implies that internalized FSH-hFSHR dissociates in endosomal compartments, and that FSH is routed to lysosomes for degradation, whereas the receptor is recycled to the cell surface. Such an inference contrasts with data indicating that the FSH-FSHR complex is predominantly recycled to the cell surface, at which dissociation of hormone and receptor occurs, with only small amounts of hormone and receptor being transported to the lysosome for degradation [27].

Species-specific differences in LHR recycling have been reported. Complexes formed by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and murine LHR are internalized and routed to lysosomes for degradation [54], whereas hCG-hLHR is recycled back to the cell surface [51]. However, the differences in FSH-hFSHR trafficking between what we report here (FSH is predominantly degraded) and what was reported in the previous study (FSH is recycled bound to FSHR) do not arise from species-specific FSHR properties, given that both studies used hFSHR. Other parameters may affect recycling and degradation (such as the use of an myc-hFSHR in one system and not in another) or variation in cell surface receptor density; the latter parameter has been shown to affect aromatase expression [55], and therefore could also influence trafficking mechanisms. In either case, both recycling and degradation are evident, but with varying degrees of efficiency.

Nonlysosomal degradation occurs in opioid receptors [56]. Although ubiquitination-proteasomal degradation is primarily considered to be a cytoplasmic protein degradation pathway, aberrant degradation could arise from defects in the ubiquitin-mediated degradation pathway. FSHR iL3 is known to interact with ubiquitin [20]. Although iL3 itself is not ubiquitinated, FSHR is ubiquitinated, and proteasomal inhibitors increase cell surface residency of hFSHR [20]. Thus, one potential mechanism for the effects observed by substitution of D550 may in some way involve this pathway. Ubiquitination-defective mutants of beta-adrenergic receptors internalize normally but are instead retained in early endosomes, escaping lysosomal trafficking and degradation [57]. Ubiquitination, in addition to targeting proteins to the proteasome, has additional roles, including sorting of internalized receptors, and deubiquitinating proteases control endosomal trafficking, and perhaps signaling [58]. Mutation of D550 may cause a conformational change in hFSHR iL3, altering recognition of the receptor cytoplasmic domains during sorting and thereby compromising degradation of internalized FSH. It is not known whether internalized FSH continues to signal, as has been reported in other systems as persistent signaling [59]. Persistent intracellular cAMP, potentially resulting from this defect, could explain elevated basal (constitutive) signaling and would not be easily detectable with standard methods. This question will be the subject of future studies employing intracellular sensors of cAMP signaling.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant HD18407.

REFERENCES

- Tapanainen JS, Vaskivuo T, Aittomäki K, Huhtaniemi IT. Inactivating FSH receptor mutations and gonadal dysfunction. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1998; 145: 129 135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias JA, Cohen BD, Lindau-Shepard B, Nechamen CA, Peterson AJ, Schmidt A. Molecular, structural, and cellular biology of follitropin and follitropin receptor. Vitam Horm 2002; 64: 249 322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griswold MD, Heckert L, Linder C. The molecular biology of the FSH receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1995; 53: 215 218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa-Aguirre A, Zarinan T, Pasapera AM, Casas-Gonzalez P, Dias JA. Multiple facets of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor function. Endocrine 2007; 32: 251 263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromoll J, Simoni M. Nordhoff, Behre HM, Geyter D, Nieschlag E. Functional and clinical consequences of mutations in the FSH receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1996; 125: 177 182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne C, Fan H, Cheng X, Richards J. Follicle-stimulating hormone induces multiple signaling cascades: evidence that activation of rous sarcoma oncogene, RAS, and the epidermal growth factor receptor are critical for Granulosa cell differentiation. Mol Endocrinol 2007; 21: 1940 1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunzicker-Dunn M, Maizels ET. FSH signaling pathways in immature granulosa cells that regulate target gene expression: branching out from protein kinase A. Cell Signal 2006; 18: 1351 1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeleznik AJ, Saxena D, Little-Ihrig L. Protein kinase B is obligatory for follicle-stimulating hormone-induced granulosa cell differentiation. Endocrinology 2003; 144: 3985 3994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheerer P, Park JH, Hildebrand PW, Kim YJ, Krauss N, Choe HW, Hofmann KP, OP Ernst. Crystal structure of opsin in its G-protein-interacting conformation. Nature 2008; 455: 497 502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias JA, Mahale SD, Nechamen CA, Davydenko O, Thomas RM, Ulloa-Aguirre A. Emerging roles for the FSH receptor adapter protein APPL1 and overlap of a putative 14-3-3tau interaction domain with a canonical G-protein interaction site. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2010; 329: 17 25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troispoux C, Guillou F, Elalouf JM, Firsov D, Iacovelli L, De Blasi A, Combarnous Y, Reiter E. Involvement of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins in desensitization to follicle-stimulating hormone action. Mol Endocrinol 1999; 13: 1599 1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter E, Marion S, Robert F, Troispoux C, Boulay F, Guillou F, Crepieux P. Kinase-inactive G-protein-coupled receptor kinases are able to attenuate follicle-stimulating hormone-induced signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001; 282: 71 78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara E, Crepieux P, Gauthier C, Martinat N, Piketty V, Guillou F, Reiter E. A phosphorylation cluster of five serine and threonine residues in the C-terminus of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor is important for desensitization but not for beta-arrestin-mediated ERK activation. Mol Endocrinol 2006; 20: 3014 3026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli M. Functional consequences of the phosphorylation of the gonadotropin receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 1996; 52: 1647 1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Hipkin RW, Ascoli M. The agonist-induced phosphorylation of the rat follitropin receptor maps to the first and third intracellular loops. Mol Endocrinol 1998; 12: 580 591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SS, Barak LS, Zhang J, MG Caron. G-protein-coupled receptor regulation: role of G-protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1996; 74: 1095 1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Krupnick JG, Benovic JL, Ascoli M. Signaling and phosphorylation-impaired mutants of the rat follitropin receptor reveal an activation- and phosphorylation-independent but arrestin-dependent pathway for internalization. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 24346 24354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy H, Galet C, Ascoli M. The association of arrestin-3 with the follitropin receptor depends on receptor activation and phosphorylation. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2003; 204: 127 140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehbi V, Tranchant T, Durand G, Musnier A, Decourtye J, Piketty V, Butnev VY, Bousfield GR, Crepieux P, Maurel MC, Reiter E. Partially deglycosylated equine LH preferentially activates beta-arrestin-dependent signaling at the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 2010; 24: 561 573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen BD, Bariteau JT, Magenis LM, Dias JA. Regulation of follitropin receptor cell surface residency by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Endocrinology 2003; 144: 4393 4402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pippig S, Andexinger S, Lohse MJ. Sequestration and recycling of beta 2-adrenergic receptors permit receptor resensitization. Mol Pharmacol 1995; 47: 666 676 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Barak LS, Winkler KE, Caron MG, SS Ferguson. A central role for beta-arrestins and clathrin-coated vesicle-mediated endocytosis in beta2-adrenergic receptor resensitization. Differential regulation of receptor resensitization in two distinct cell types. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 27005 27014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanowitz M, Hislop JN, von Zastrow M. Alternative splicing determines the post-endocytic sorting fate of G-protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 35614 35621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innamorati G, Sadeghi HM, Tran NT, Birnbaumer M. A serine cluster prevents recycling of the V2 vasopressin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95: 2222 2226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu A, Kawashima S. Kinetic study of internalization and degradation of 131I-labeled follicle-stimulating hormone in mouse Sertoli cells and its relevance to other systems. J Biol Chem 1989; 264: 13632 13638 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias JA. Effect of transglutaminase substrates and polyamines on the cellular sequestration and processing of follicle-stimulating hormone by rat Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod 1986; 35: 49 58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy H, Kishi H, Shi M, Galet C, Bhaskaran RS, Kirakawa T, Ascoli M. Postendocytotic trafficking of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)-FSH receptor complex. Mol Endocrinol 2003; 17: 2162 2176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromoll J, Simoni M, Nieschlag E. An activating mutation of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor autonomously sustains spermatogenesis in a hypophysectomized man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81: 1367 1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan CM, Garcia A, Spaliviero J, Jimenez M, Handelsman DJ. Maintenance of spermatogenesis by the activated human (Asp567Gly) FSH receptor during testicular regression due to hormonal withdrawal. Biol Reprod 2006; 74: 938 944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin FT, Chen W, Shenoy S, Cong M, Exum ST, Lefkowitz RJ. Phosphorylation of beta-arrestin2 regulates its function in internalization of beta(2)-adrenergic receptors. Biochemistry 2002; 41: 10692 10699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolchuk V, Banting G. Kinases in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Biochem Soc Trans 2003; 31: 857 860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias JA, Nechamen CA, Atari R. Identifying protein interactors in gonadotropin action. Endocrine 2005; 26: 241 247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrecilla I, Spragg EJ, Poulin B, McWilliams PJ, Mistry SC, Blaukat A, Tobin AB. Phosphorylation and regulation of a G protein-coupled receptor by protein kinase CK2. J Cell Biol 2007; 177: 127 137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebholz H, Nishi A, Liebscher S, Nairn AC, Flajolet M, Greengard P. CK2 negatively regulates G{alpha}s signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 14096 14101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Zvi D, Branton D. Clathrin-coated vesicles contain two protein kinase activities. Phosphorylation of clathrin beta-light chain by casein kinase II. J Biol Chem 1986; 261: 9614 9621 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotlin LF, Siddiqui MA, Simpson F, Collawn JF. Casein kinase II activity is required for transferrin receptor endocytosis. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 30550 30556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletto G, Vilardell J, Marin O, Pagano MA, Cozza G, Sarno S, Falques A, Itarte E, Pinna LA, Meggio F. The regulatory beta subunit of protein kinase CK2 contributes to the recognition of the substrate consensus sequence. A study with an eIF2 beta-derived peptide. Biochemistry 2008; 47: 8317 8325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelton CA, Cheng SV, Nugent NP, Schweickhardt RL, Rosenthal JL, Overton SA, Wands GD, Kuzeja JB, Luchette CA, Chappel SC. The cloning of the human follicle stimulating hormone receptor and its expression in COS-7, CHO, and Y-1 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1992; 89: 141 151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechamen CA, Dias JA. Point mutations in follitropin receptor result in ER retention. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2003; 201: 123 131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechamen CA, Dias JA. Human follicle stimulating hormone receptor trafficking and hormone binding sites in the amino terminus. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2000; 166: 101 110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau-Shepard B, Brumberg HA, Peterson AJ, Dias JA. Reversible immunoneutralization of human follitropin receptor. J Reprod Immunol 2001; 49: 1 19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner CG, Wang Z, Litchfield DW. Expression and localization of epitope-tagged protein kinase CK2. J Cell Biochem 1997; 64: 525 537 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damke H, Baba T, Warnock DE, Schmid SL. Induction of mutant dynamin specifically blocks endocytic coated vesicle formation. J Cell Biol 1994; 127: 915 934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, MacColl R, Lindau-Shepard B, Buckler DR, Dias JA. Hormone-induced conformational change of the purified soluble hormone binding domain of follitropin receptor complexed with single chain follitropin. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 23373 23381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas RM, Nechamen CA, Mazurkiewicz JE, Muda M, Palmer S, Dias JA. Follice-stimulating hormone receptor forms oligomers and shows evidence of carboxyl-terminal proteolytic processing. Endocrinology 2007; 148: 1987 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan CM, Lim P, Robson M, Spaliviero J, Handelsman DJ. Transgenic mutant D567G but not wild-type human FSH receptor overexpression provides FSH-independent and promiscuous glycoprotein hormone Sertoli cell signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2009; 296: E1022 E1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano MA, Poletto G, Di Maira G, Cozza G, Ruzzene M, Sarno S, Bain J, Elliott M, Moro S, Zagotto G, Meggio F, Pinna LA. Tetrabromocinnamic acid (TBCA) and related compounds represent a new class of specific protein kinase CK2 inhibitors. Chembiochem 2007; 8: 129 139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka JA, Weigel PH. Effects of hyperosmolarity on ligand processing and receptor recycling in the hepatic galactosyl receptor system. J Cell Biochem 1988; 36: 169 183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata A, Kamiguchi H. Serine phosphorylation by casein kinase II controls endocytic L1 trafficking and axon growth. J Neurosci Res 2007; 85: 723 734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nojiri M, Loyet KM, Klenchin VA, Kabachinski G, TF Martin. Caps activity in priming vesicle exocytosis requires CK2 phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 18707 18714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galet C, Ascoli M. A constitutively active mutant of the human lutropin receptor (hLHR-L457R) escapes lysosomal targeting and degradation. Mol Endocrinol 2006; 20: 2931 2945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage RM, Kim KA, Cao TT, von Zastrow M. A transplantable sorting signal that is sufficient to mediate rapid recycling of G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 44712 44720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whistler JL, Enquist J, Marley A, Fong J, Gladher F, Tsuruda P, Murray SR, Von Zastrow M. Modulation of postendocytic sorting of G protein-coupled receptors. Science 2002; 297: 615 620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli M. Lysosomal accumulation of the hormone-receptor complex during receptor-mediated endocytosis of human choriogonadotropin. J Cell Biol 1984; 99: 1242 1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadeu F, Ascoli M. The differential effects of the gonadotropin receptors on aromatase expression in primary cultures of immature rat granulosa cells are highly dependent on the density of receptors expressed and the activation of the inositol phosphate cascade. Endocrinology 2005; 146: 3907 3916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi K, Bandari P, Chinen N, Howells RD. Proteasome involvement in agonist-induced down-regulation of mu and delta opioid receptors. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 12345 12355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JE, Padilla BE, Hasdemir B, Cottrell GS, Bunnett NW. Endosomes: a legitimate platform for the signaling train. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 17615 17622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy SK, McDonald PH, Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of receptor fate by ubiquitination of activated beta 2-adrenergic receptor and beta-arrestin. Science 2001; 294: 1307 1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calebiro D, Nikolaev VO, Gagliani MC, de Filippis T, Dees C, Tacchetti C, Persani L, Lohse MJ. Persistent cAMP-signals triggered by internalized G-protein-coupled receptors. PLoS Biol 2009; 7: e1000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.