Abstract

Cyanobacterial mass occurrences in freshwater lakes are generally formed by Anabaena, Microcystis, and Planktothrix, which may produce cyclic heptapeptide hepatotoxins, microcystins. Thus far, identification of the most potent microcystin producer in a lake has not been possible due to a lack of quantitative methods. The aim of this study was to identify the microcystin-producing genera and to determine the copy numbers of microcystin synthetase gene E (mcyE) in Lake Tuusulanjärvi and Lake Hiidenvesi in Finland by quantitative real-time PCR. The microcystin concentrations and cyanobacterial cell densities of these lakes were also determined. The microcystin concentrations correlated positively with the sum of Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers from both Lake Tuusulanjärvi and Lake Hiidenvesi, indicating that mcyE gene copy numbers can be used as surrogates for hepatotoxic Microcystis and Anabaena. The main microcystin producer in Lake Tuusulanjärvi was Microcystis spp., since average Microcystis mcyE copy numbers were >30 times more abundant than those of Anabaena. Lake Hiidenvesi seemed to contain both nontoxic and toxic Anabaena as well as toxic Microcystis strains. Identifying the most potent microcystin producer in a lake could be valuable for designing lake restoration strategies, among other uses.

In many eutrophic freshwater lakes, cyanobacteria frequently form toxic mass occurrences. Hepatotoxic mass occurrences are more common than neurotoxic ones, and they are generally formed by Anabaena, Microcystis, and Planktothrix genera, which have strains that are able to produce cyclic heptapeptides, microcystins (45). In Finnish freshwater lakes, Anabaena and Microcystis often coexist and form hepatotoxic mass occurrences (11, 47). Thus far, more than 60 structural variants of microcystins exhibiting different hepatotoxicities have been described (45). Microcystins inhibit eukaryotic serine/threonine protein phosphatase 1 and 2A and act as tumor promoters (24). Due to human and animal poisonings and the results of toxicological studies, which have shown the adverse effects of microcystins to some mammals, many countries have started to monitor cyanobacterial cell densities and microcystin concentrations in raw water sources and recreational waters. The most common methods for monitoring microcystin concentrations have been high-performance liquid chromatography combined with a UV-visible light diode array detector, protein phosphatase inhibition, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (19). However, such analysis does not indicate which cyanobacteria produce the toxins, since several genera of cyanobacteria may produce similar microcystin variants (45). Microcystin concentration in a body of water seems to be mostly dependent on the density of the hepatotoxic cells (45). It has also been demonstrated that some strains may produce higher concentrations of microcystins than other strains under the same laboratory conditions. In addition, environmental factors, such as nutrient concentrations, light, and temperature, may also affect the intracellular microcystin concentration (45).

In evolutionary trees of 16S rRNA genes of planktic cyanobacteria, one branch can contain both toxic and nontoxic strains within one cyanobacterial genus (17, 29, 31, 50). Both toxic and nontoxic strains have been isolated (37, 55) and observed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (13, 25) in the same mass occurrences. Since it is not possible to distinguish toxic and nontoxic cells with a microscope, microscopic analysis cannot be used to estimate the numbers of toxic cyanobacteria. Microcystins are synthesized nonribosomally by a peptide synthetase polyketide synthase enzyme complex encoded by the microcystin synthetase (mcy) gene cluster (9, 10, 33, 34, 51). PCR amplification of mcyA, -B, and -C genes from environmental samples has been applied for early detection of potentially toxic Microcystis mass occurrences (2, 3, 35, 38). However, these PCR and MALDI-TOF MS identification methods are not quantitative.

Quantitative methods are needed in order to study the succession of the microcystin-producing genera in lakes. These methods would enable us to monitor the formation of toxic mass occurrences and reveal the factors promoting the growth of toxic strains in situ. Characterization of the most potent microcystin producer could be valuable in designing genus-targeted lake restoration strategies, since hepatotoxic bloom-forming Microcystis and nitrogen-fixing Anabaena have different growth responses to various nutrient concentrations (28, 39, 40, 54). All known microcystin variants have d-glutamate (45), and the carboxyl group of the glutamate side chain has been shown to be essential for the toxicity, since the microcystin variants with an esterified carboxyl group do not cause toxic effects in mice (15, 30). Therefore, the mcyE gene which encodes the glutamate-activating adenylation domain can be used as a surrogate for microcystin-producing cyanobacteria.

The aim of this study was to develop a method to identify and quantify the main microcystin-producing genera in lakes. Genus-specific mcyE primers were designed and used to quantify Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers occurring in Lake Tuusulanjärvi and Lake Hiidenvesi, Finland, by quantitative real-time PCR (QRT-PCR).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultures.

A total of 13 Microcystis and 8 Planktothrix strains were grown in Z8 medium (23), whereas 14 Anabaena strains and one Nostoc strain were grown in a modified Z8 medium without nitrogen (see Table 2 for the strains used). The strains were grown under continuous light (20 μmol m−2 s−1) at 20 ± 2°C. Cells were harvested, and DNA was isolated as detailed below.

TABLE 2.

Microcystis, Anabaena, Planktothrix, and Nostoc strains used in this study

| Straina | MCb | Specificityc of:

|

GenBank accession no. | Reference(s)d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anabaena mcyE primers | Microcystis mcyE primers | ||||

| Microcystis sp. strains | |||||

| 98 | + | − | + | AY382537 | 47, B |

| 205 | + | − | + | AY382538 | 47, B |

| GL 260735 | + | − | + | AY382531 | 55, B |

| GL 280646 | + | − | + | AY382532 | 55, B |

| IZANCYA 5 | + | − | + | AY382533 | 53, B |

| IZANCYA 25 | + | − | + | AY382534 | 53, B |

| NIES102 | + | − | + | AY382535 | 29, B |

| NIES A 89 | + | − | + | AY382530 | 29, B |

| PCC 7941 | + | − | + | AY382536 | 43, B |

| PCC 7806 | + | − | + | AF183408 | 43, 51 |

| 130 | − | − | − | 44 | |

| 269 | − | − | − | 44 | |

| GL 060916 | − | − | − | 55 | |

| Anabaena sp. strains | |||||

| 66A | + | + | − | AY382543 | 47, B |

| 90 | + | + | − | AJ536156 | 47, A |

| 202A1 | + | + | − | AY382545 | 47, B |

| 202A2/41 | + | + | − | AY382546 | 47, B |

| NIVA-CYA83/1 | + | + | − | AY382544 | 47, B |

| 315 | + | + | − | AY382548 | B |

| 318 | + | + | − | AY382549 | B |

| 86 | − | − | − | 46 | |

| 123 | − | − | − | 46 | |

| 14 | − | − | − | 46 | |

| PCC 6309 | − | − | − | 43 | |

| PCC7 108 | − | − | − | 43 | |

| PCC 73105 | − | − | − | 43 | |

| PCC 9208 | − | − | − | 43 | |

| Planktothrix sp. strains | |||||

| 49 | + | − | − | AY382551 | 47, B |

| 97 | + | − | − | AY382552 | 47, B |

| 213 | + | − | − | AY382555 | 47 |

| NIVA-CYA 126 | + | − | − | AJ441056 | 9, 47 |

| NIVA-CYA 127 | + | − | − | AY382553 | 47, B |

| NIVA-CYA 128/R | + | − | − | AY382554 | 47, B |

| 45 | − | − | − | 44 | |

| PCC 6304 | − | − | − | 43 | |

| Nostoc sp. strain 152 | + | − | − | AY382539 | 48, B |

Some strain designations include culture collection abbreviations. Culture collections: PCC, Pasteur Culture Collection, Paris, France; NIVA-CYA, Norwegian Institute for Water Research, Oslo, Norway; NIES, National Institute for Environmental Studies, Tsukuba, Japan.

Microcystin (MC) production (+) or lack of production (−) was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography.

Specificity of Microcystis (mcyE-F2 and MicmcyE-R8) and Anabaena (mcyE-F2 and AnamcyE-12R) microcystin synthetase gene E (mcyE) primers. The presence (+) or absence (−) of the mcyE product was studied with PCR.

Articles submitted for publication are indicated as follows: A, Rouhiainen et al.; B, Rantala et al.

Lake water samples.

Water samples were collected from Lake Tuusulanjärvi from a depth of 0 to 2 m every 2 or 3 weeks in the summer of 1999. For DNA extraction, particles from 1 liter of lake water were concentrated to less than 2 ml by centrifugation and stored at −70°C. Lake Hiidenvesi consists of several natural basins representing a transition from hypertrophy to mesotrophy. Water samples were collected from three to five different depths from the basins of Lakes Kirkkojärvi (maximum depth at the sampling site was 3.5 m), Mustionselkä (4 m), Nummelanselkä (6 m), and Kiihkelyksenselkä (30 m) on 15 August 2001. For DNA extraction, 100 ml of Lake Hiidenvesi water was filtered through 3-μm-pore-size Poretics polycarbonate disk filter (diameter, 47 mm) (Osmonics, Inc.), and the cells were stored with lysis buffer at −20°C (14). For microcystin concentration analysis, 5-ml samples of lake water were stored in glass vials at −20°C.

Microscopic analysis.

Cyanobacterial cell densities were determined by the inverted microscope technique (52) from the samples which were preserved with acid Lugol's solution (57) and stored in darkness at 4°C.

Microcystin analysis of the cultures and lake water samples.

The dry weights of the Microcystis, Anabaena, Planktothrix, and Nostoc strains were measured, and microcystin was extracted by sonication as detailed previously (41). The presence of microcystins was analyzed with an Agilent 1100 series high-performance liquid chromatograph with a diode array detector and Luna C18 column (150 by 2 mm; Phenomenex) (particle size, 5 μm). The mobile phase was 10 mM ammonium acetate and acetonitrile. From 6 to 40 min, the concentration of acetonitrile increased from 24 to 60%. The flow rate was 0.2 ml min−1 at 40°C, the injection volume was 20 μl, and microcystins were detected at 238 nm. Purified microcystin-LR was used as a reference compound, and microcystins were identified by their UV spectra and retention times.

Total microcystins of the lake water samples were extracted from 5 ml of lake water by using a tip sonicator for 5 min (Braun Labsonic-U). Prior to measuring the microcystin concentration with an EnviroGard microcystin plate kit (Strategic Diagnostics, Inc.) and plate spectrophotometer (Labsystems iEMS reader MF), the samples were filtered through 0.2-μm-pore-size Puradisc filters (Whatman) to remove the particles.

Extraction and purification of DNAs.

Genomic DNAs of the Microcystis, Anabaena, Planktothrix, and Nostoc strains and the lake water samples were extracted with a hot phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol method (14). Extracted DNAs were purified either once (strains) or twice (lake water samples) with a Prep-A-Gene DNA Purification Kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions and eluted in 60 μl.

Primer design and specificity testing.

General microcystin synthetase gene E forward primer (mcyE-F2) and genus-specific reverse primers for Microcystis (MicmcyE-R8) and Anabaena (AnamcyE-12R) (Table 1) were designed with mcy gene sequences of Anabaena sp. strain 90 (L. Rouhiainen, T. Vakkilainen, B. L. Siemer, W. Buikema, R. Haselkorn, and K. Sivonen, submitted for publication), by using BLAST (1) and BioEdit (18).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| mcyE-F2a | GAA ATT TGT GTA GAA GGT GC |

| MicmcyE-R8 | CAA TGG GAG CAT AAC GAG |

| AnamcyE-12R | CAA TCT CGG TAT AGC GGC |

The forward primer, mcyE-F2, used in this study will be described elsewhere (Rantala et al., submitted).

The PCR was performed with 1 μl of extracted DNA, 1× DynaZyme II PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.8 at 25°C], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100 [Finnzymes]), 250 μM concentration of all four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Finnzymes), 0.5 μM concentrations of primers (Sigma-Genosys Ltd.), and 0.5 U of DyNAzyme II DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) in a volume of 20 μl. PCR amplification was performed as follows. The first step was an initial denaturation step of 3 min at 95°C. For Microcystis mcyE gene-specific primers, the initial denaturation step was followed by 25 cycles of PCR, with 1 cycle consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 60 s at 72°C. For Anabaena mcyE gene-specific primers, the initial denaturation step was followed by 30 cycles of PCR, with 1 cycle consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 58°C, and 60 s at 72°C. The PCR cycles were followed by a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. All strains listed in Table 2 were tested with these two primer pairs. The presence or absence of the mcyE product was determined using 20 μl of amplification product and 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. The bands were stained with ethidium bromide and documented with a Kodak CD 290 camera. To exclude the possibility of PCR-inhibiting contaminants, PCRs with cyanobacterium-specific 16S rRNA gene primers (36) was used to test the quality of the DNAs, which did not amplify products with mcyE primers.

QRT-PCR.

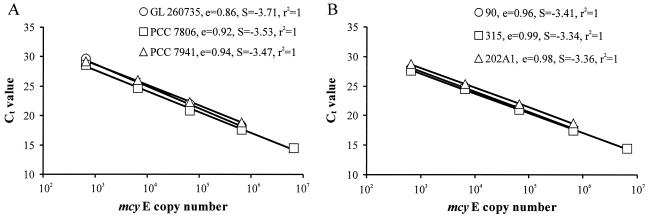

External standards used to determine mcyE copy numbers were prepared using genomic DNAs of Microcystis sp. strains GL 260735, PCC 7806, and PCC 7941 as well as those of Anabaena sp. strains 90, 315, and 202A1. The genomic DNA concentration of these DNAs was measured with a spectrophotometer set at 260 nm (Beckman DU-7400). Purity was determined by calculating the ratio of the absorbance measured at 260 nm (A260) to the absorbance measured at 280 nm (A280). Approximate genome sizes (4.70 Mb for Microcystis and 5.15 Mb for Anabaena) were used in the mcyE copy number calculation. These genome sizes were estimated on the basis of the genome sizes of Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7941, Anabaena sp. strain PCC 6309, and Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7122 (7). The mcyE copy numbers of the DNAs of the standard strains were calculated using the following equation assuming that each genome had only one mcyE gene and that the molecular weight of 1 bp was 660 g mol−1: number of copies per microliter = (6 × 1023)(DNA concentration)/molecular weight of one genome, where 6 × 1023 is the number of copies per mole, the DNA concentration is given in grams per microliter, and the molecular weight of one genome is given in grams per mole. Series of 10-fold dilutions of genomic DNAs of the standard strains were prepared, and these dilutions were amplified with Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE QRT-PCR. Linear regression equations for obtained cycle threshold values (Ct values, i.e., the first turning points of the fluorescence curves as a function of cycle numbers) were calculated as a function of known mcyE copy numbers.

The QRT-PCR was performed with 1 μl of DNA from a standard strain or lake water sample, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM concentrations of both primers (Sigma-Genosys, Ltd.), and 1 μl of hot start reaction mix to a final volume of 10 μl (LightCycler fastStart DNA master SYBR green I kit; Roche Diagnostics). Amplification was performed as follows: an initial preheating step of 10 min at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 2 s at 95°C, 5 s at 58°C, and 10 s at 72°C. Generation of the products was monitored after each extension step at 78°C in Microcystis and 77°C in Anabaena mcyE QRT-PCR by measuring the fluorescence of double-stranded DNA binding SYBR green 1 dye using LightCycler QRT-PCR (Roche Diagnostics). All lake water samples were amplified in triplicate. The Ct values were determined by the second derivative maximum method of LightCycler software (version 3.5). Copy numbers of mcyE gene of the lake water samples were determined by converting the obtained Ct values into the mcyE copy numbers according to the regression equations of the external standards that gave the highest (Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7941 and Anabaena sp. strain 202A1) and lowest (Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7806 and Anabaena sp. strain 315) mcyE copy numbers (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Ct values obtained by microcystin synthetase gene E (mcyE) QRT-PCR with Microcystis and Anabaena strains as a function of mcyE copy number. (A) Microcystis sp. strains GL 260735, PCC 7806, and PCC 7941. (B) Anabaena sp. strains 90, 315, and 202A1. Amplification efficiencies, e (e = 10−1/S − 1, where S is the slope of the linear regression), of the Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE QRT-PCR were also calculated as a function of mcyE copy numbers. Error bars, which are hidden by the symbols in almost all cases, give the standard deviations for three independent amplifications.

Amplification efficiencies, e (e = 10−1/S − 1, where S is the slope of the linear regression), of the Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE QRT-PCR with standard strains were calculated as a function of known mcyE copy numbers and with those of Lake Tuusulanjärvi DNA samples as a function of different dilutions of the samples.

In order to determine melting temperatures for the amplification products of the standard strains and of the lake water samples, the temperature was raised after QRT-PCR from 65 to 95°C, and fluorescence was detected continuously. The characteristic melting temperatures of the mcyE QRT-PCR products were determined with LightCycler software (version 3.5).

Statistical analysis.

Spearman correlation coefficients between the microcystin concentration (in micrograms per liter), mcyE copy number (number of copies per milliliter), and Microcystis as well as Anabaena cell numbers (number of cells per milliliter) of lake water samples were calculated with SAS statistical software for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc.).

RESULTS

Specificity of the primers.

The mcyE gene primers (Table 1) were both genus and mcyE gene specific, since a single amplification product was observed when genomic DNA from a microcystin-producing Microcystis or Anabaena strain was used as a template in PCR with Microcystis or Anabaena genus-specific primers (Table 2). The DNAs of the strains (i.e., Planktothrix, Nostoc, nontoxic Anabaena and Microcystis, and neurotoxic Anabaena) used as negative controls to test the specificity of Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE gene primers did not contain PCR-inhibiting substances, since they all gave amplification products with cyanobacterium-specific 16S rRNA gene primers but gave no products when those DNAs were amplified with Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE gene primers (Table 2).

Detection range of mcyE copy numbers.

The QRT-PCR was log linear from 6.6 × 102 to 6.6 × 105 mcyE copies in a reaction mixture when the genomic DNA from standard strain Microcystis sp. strain GL 260735, Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7941, Anabaena sp. strain 90, or Anabaena sp. strain 202A1 was used as a template and from 6.6 × 102 to 6.6 × 106 when the genomic DNA of standard strain Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7806 or Anabaena sp. strain 315 was used (Fig. 1). The lowest reliable numbers of mcyE copies detected were 40 copies ml−1 for Lake Tuusulanjärvi and 400 copies ml−1 for Lake Hiidenvesi. The difference between the detection limits of the two lakes was due to the different sample volumes collected. One nanogram of genomic DNA from the standard strains of Microcystis and Anabaena contained 1.94 × 105 and 1.76 × 105 mcyE copies, respectively. The purity (A260/A280) of these DNAs varied from 1.8 to 1.9.

mcyE copy numbers in lake water samples.

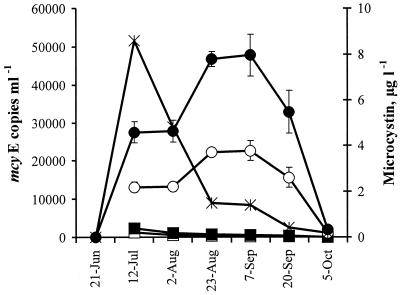

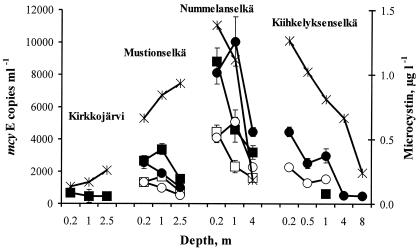

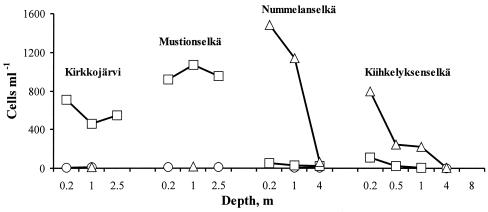

Microcystis mcyE copy numbers in Lake Tuusulanjärvi during the sampling period were 12 to 91 times more abundant than those of Anabaena mcyE copy numbers calculated as a ratio of the average mcyE copy numbers obtained with Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7941 and Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7806 or Anabaena sp. strain 315 and Anabaena sp. strain 202A1 standards, respectively (Fig. 2). Microcystis mcyE copy numbers were also more abundant than those of Anabaena in the Kiihkelyksenselkä Basin of Lake Hiidenvesi (Fig. 3). In the Nummelanselkä and Mustionselkä Basins, Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers were quite similar. In the Kirkkojärvi Basin, Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers were below or near the detection limit. In Lake Hiidenvesi (Fig. 3), the average mcyE copy numbers of Microcystis and Anabaena and microcystin concentrations were lower than in Lake Tuusulanjärvi (Fig. 2). There was a statistically significant positive correlation between the microcystin concentration and the Microcystis mcyE copy number and the sum of Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers, when all the samples above the detection limits, were combined to form a single data set (Table 3). In Lake Hiidenvesi, the Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers obtained with the standards, which gave the highest copy numbers, showed a positive correlation with the microcystin concentrations (Table 3). Interestingly, in Lake Tuusulanjärvi, positive correlation was found only between Anabaena mcyE copy numbers and microcystin concentrations.

FIG. 2.

Microcystin concentration and Anabaena and Microcystis microcystin synthetase gene E (mcyE) copy numbers using Lake Tuusulanjärvi water samples collected during the summer of 1999. Microcystin concentration (×) (in micrograms per liter) was determined by an ELISA. Microcystis mcyE copy numbers (number of copies per milliliter) were obtained by QRT-PCR and were calculated with the external standards of Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7941 (•), Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7806 (○), Anabaena sp. strain 202A1 (▪), and Anabaena sp. strain 315 (□).

FIG. 3.

Microcystin concentration and Anabaena and Microcystis microcystin synthetase E (mcyE) copy numbers in samples of lake water collected from different depths of four Lake Hiidenvesi basins on 15 August 2001. Microcystin concentration (×) (in micrograms per liter) was determined by an ELISA. Microcystis mcyE copy numbers (number of copies per milliliter) were obtained by QRT PCR and were calculated with the external standards of Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7941 (•), Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7806 (○), Anabaena sp. strain 202A1 (▪), and Anabaena sp. strain 315 (□).

TABLE 3.

Spearman correlation coefficients between microcystin concentration, mcyE copy number and cell number

| Lake water samples | Value and/or Spearman correlation coefficienta

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Microcystis mcyE

|

Anabaena mcyE

|

Microcystis + Anabaena mcyE | Microcystis cells | Anabaena cells | Microcystis + Anabaena cells | |||

| PCC 7941 | PCC 7806 | 202A1 | 315 | |||||

| Combined lake samples | 0.67 B (18) | 0.57 A (15) | NS | NS | 0.55 A (15) | NS | NS | NS |

| Lake Tuusulanjärvi | NS | NS | 1 C (6) | 1 C (5) | NS | 0.68 M (7) | NS | 0.86 A (7) |

| Lake Hiidenvesi | 0.56 M (11) | NS | 0.67 A (10) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Spearman correlation coefficients between microcystin concentration (in micrograms per liter) and microcystin synthetase gene E (mcyE) copy numbers (copies per milliliter) above the detection limits calculated using different standards (Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7941, Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7806, Anabaena sp. strain 202A1, and Anabaena sp. strain 315) and cell numbers (cells per milliliter) of combined results of Lakes Tuusulanjärvi and Hiidenvesi and the results of Lakes Tuusulanjärvi and Hiidenvesi separately. The sum of Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers was obtained by adding the average copy numbers calculated using the two Microcystis and Anabaena standards. The Spearman coefficients are indicated as follows: NS, not significant; M, P < 0.1; A, P < 0.05; B, P < 0.01; C, P < 0.001. The number of samples used to calculate the Spearman correlation coefficient is shown in parentheses.

Microcystin concentration and cyanobacterial cell density of lake water.

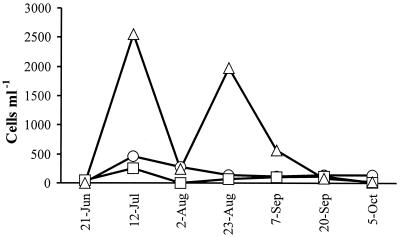

Microcystin concentrations as well as Microcystis and Anabaena cell densities were highest in Lake Tuusulanjärvi in July and started to decrease thereafter (Fig. 2 and 4). In Lake Hiidenvesi, microcystin concentrations and cell densities were lower than those in Lake Tuusulanjärvi (Fig. 3 and 5). According to the microscopic analysis, Microcystis cells were more abundant than Anabaena cells in Lake Tuusulanjärvi, whereas Microcystis cells were observed only occasionally in Lake Hiidenvesi. Anabaena was the most dominant genus in the Basins of Kirkkojärvi and Mustionselkä of Lake Hiidenvesi, whereas Aphanizomenon was the most dominant genus in the Basins of Nummelanselkä and Kiihkelyksenselkä of Lake Hiidenvesi as well as in Lake Tuusulanjärvi. Microcystin concentration did not correlate with the number of Microcystis or Anabaena cells or the sum of Microcystis and Anabaena cell numbers, when all lake water samples were combined to form a single data set (Table 3).

FIG. 4.

Cell numbers of the most dominant cyanobacterial genera in Lake Tuusulanjärvi in 1999 by light microscopy. The most dominant cyanobacterial genera were Microcystis (○), Anabaena (□), and Aphanizomenon (▵).

FIG. 5.

Cell numbers of the most dominant cyanobacterial genera in Lake Hiidenvesi on 15 August 2001 by light microscopy. The most dominant cyanobacterial genera were Microcystis (○), Anabaena (□), and Aphanizomenon (▵). The samples of water were taken from different depths in the four basins of Lake Hiidenvesi.

Amplification efficiency.

With Lake Tuusulanjärvi water samples, the Microcystis mcyE QRT-PCR amplification efficiencies (0.78 to 0.99 [Table 4]) were similar to the amplification efficiencies of the Microcystis standards (0.86 to 0.94 [Fig. 1A]). Anabaena mcyE QRT-PCR amplification efficiencies with Lake Tuusulanjärvi water samples (1.14 to 2.36 [Table 4]) were unrealistically high compared to the amplification efficiencies of the Anabaena standard strains (0.96 to 0.99 [Fig. 1B]).

TABLE 4.

Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE ORT-PCR amplification efficiencies of Lake Tuusulanjärvi water samples calculated as a function of different dilutions of the samplesa

| Genus and sampling date | e | S | r2 | Dilution factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcystis | ||||

| 12 July | 0.95 | −3.46 | 1 | 1, 0.1, 0.05, 0.01, 0.005 |

| 2 August | 0.97 | −3.39 | 1 | 1, 0.1 |

| 23 August | 0.99 | −3.34 | 1 | 1, 0.1 |

| 7 September | 0.80 | −3.92 | 1 | 1, 0.1 |

| 20 September | 0.78 | −3.99 | 1 | 1, 0.1 |

| 6 October | 0.88 | −3.66 | 1 | 1, 0.1 |

| Anabaena | ||||

| 12 July | 1.32 | −2.74 | 1 | 1, 0.1, 0.05 |

| 2 August | 1.14 | −3.02 | 1 | 1, 0.1, 0.05 |

| 23 August | 1.32 | −2.74 | 1 | 1, 0.1 |

| 7 September | 2.36 | −1.90 | 0.98 | 1, 0.1, 0.05 |

Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE QRT-PCR amplification efficiencies were calculated as follows: e = 10−1/S −1, where S is the slope of the linear regression equation.

Melting curve analysis.

Characteristic melting temperatures of the mcyE QRT-PCR products (247 bp) of the three Microcystis standard strains (average, 81.5°C; coefficient of variation [CV], 0.2%; n = 38 [Table 5]) and three Anabaena standard strains (average, 79.6°C; CV, 0.4%; n = 38 [Table 5]) corresponded to the melting temperatures of Microcystis (average, 81.7°C; CV, 0.2%; n = 63) and Anabaena (average, 79.3°C; CV, 0.3%; n = 58) mcyE QRT-PCR products amplified with lake water samples (data not shown). The 1.9°C difference in the average characteristic melting temperatures was due to a >40-nucleotide difference between Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE sequences (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Characteristic melting temperatures of the microcystin synthetase gene E QRT-PCR amplification products (247 bp) obtained using LightCycler melting curve analysis

| Strain | Tma | n | Nucleotide differencesb

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Microcystis sp. strain

|

Anabaena sp. strain

|

|||||||

| GL 260735 | PCC 7806 | PCC 7941 | 90 | 315 | 202A1 | |||

| Microcystis sp. strains | ||||||||

| GL 260735 | 81.3 (0.2) | 12 | ||||||

| PCC 7806 | 81.5 (0.2) | 15 | 2 | |||||

| PCC 7941 | 81.5 (0.1) | 11 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Anabaena sp. strains | ||||||||

| 90 | 79.7 (0.2) | 12 | 45 | 47 | 47 | |||

| 315 | 79.3 (0.4) | 14 | 45 | 47 | 47 | 0 | ||

| 202A1 | 79.7 (0.2) | 12 | 46 | 48 | 48 | 1 | 1 | |

Melting temperature (Tm) is given in degrees and in Celsius. The values in parentheses are CVs and are percentages.

Nucleotide differences were calculated for the 209-bp sequence between the primer annealing sites.

Primer dimers were detected in Microcystis and in Anabaena mcyE QRT-PCR with negative controls and in Anabaena mcyE QRT-PCR with lake water samples that had low template DNA concentration, although hot start Taq DNA polymerase provided by the manufacturer of the kit was used. The error caused by the primer dimers was avoided by measuring the fluorescence of Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE QRT-PCR amplification at a higher temperature (78 and 77°C, respectively) than the melting temperature of the primer dimers.

DISCUSSION

In Lake Tuusulanjärvi, Microcystis was the main putative microcystin producer, since average Microcystis mcyE copy numbers were clearly higher than those of Anabaena (Fig. 2). In the same samples, the numbers of Microcystis cells were also higher than those of Anabaena (Fig. 4). Previously, in Lake Tuusulanjärvi, hepatotoxicities and microcystin concentrations had been found to be positively correlated with Microcystis biomass (11, 27), and the presence of toxic Microcystis and Anabaena had been indicated (11). Microcystis spp. were also the main putative microcystin producers in the Kiihkelyksenselkä Basin of Lake Hiidenvesi (Fig. 3), although Anabaena cell numbers were higher than those of Microcystis (Fig. 5). This indicates that the majority of the Anabaena cells did not contain the mcyE genes and were thus nontoxic. In the Mustionselkä, Nummelanselkä, and Kirkkojärvi Basins of Lake Hiidenvesi, the main microcystin producer could not be assessed, since in the Mustionselkä and Nummelanselkä Basins, the Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers were quite similar, and in the Kirkkojärvi Basin, the Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers were below or near the lowest reliable detection limit (Fig. 3). The low mcyE copy numbers detected in Kirkkojärvi Basin were in agreement with the low microcystin concentrations measured in the basin. Gene mcyE copy numbers, microcystin concentrations, and cyanobacterial cell densities were lower in Lake Hiidenvesi than in Lake Tuusulanjärvi. In Lake Tuusulanjärvi and in surface water of the Nummelanselkä and Kiihkelyksenselkä Basins of Lake Hiidenvesi, the World Health Organization microcystin concentration guideline value for drinking water quality (1 μg liter−1) (12) was exceeded.

Microcystin concentration had a statistically significant positive correlation with the Microcystis mcyE copy number and the sum of Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers, when all samples above the detection limits from two lakes were combined to form a single data set (Table 3). Therefore, genus-specific mcyE gene copy numbers can be used as rough values for hepatotoxic Microcystis and Anabaena. However, no significant correlation was observed between microcystin concentration and Microcystis mcyE copy number in Lake Tuusulanjärvi, since the highest microcystin concentration occurred almost 2 months prior to the highest mcyE copy number concentration (Fig. 2 and 4). Possible explanations are that the Microcystis cells had more genome copies in late summer, the high microcystin concentration measured on July was due to the strains which had very high intracellular microcystin concentrations, or that the DNA of lysed cells was present in the lake water after August and might have increased the DNA concentration in the final samples. More research is needed to elucidate the relative importance of these factors. Microcystin concentration did not correlate significantly with Microcystis and Anabaena cell numbers, when all lake water samples were combined (Table 3). The lack of correlation confirmed that due to the presence of nontoxic cells, it is not possible to reliably determine the most potent microcystin producer of a lake by microscopic analysis.

Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers were 2 to >200 times higher than the cell numbers observed with microscopy in Lakes Tuusulanjärvi and Hiidenvesi. Possible explanations for the high mcyE copy number and cell density ratio are that the cell numbers detected with a microscope were too low or the genome sizes of the external standard strains were underestimated. Even though it is known that cyanobacteria may have several genome copies in a cell (4, 21, 26), it seems that the obtained mcyE copy numbers were too high. The genome sizes estimated for the Anabaena standard strains were 5.15 Mb according to the published data of Anabaena sp. strains PCC 6309 and PCC 7122 (7). These Anabaena strains are nontoxic (29) and lack the microcystin synthetase genes, the sizes of which are not more than 53 or 55 kb (9, 33, 34, 51; Rouhiainen et al., submitted). For Microcystis, the genome size of 4.70 Mb was used according to the genome size of one of the standard strains, Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7941 (7).

In general, nontoxic strains do not contain mcy genes (32, 50). However, some strains may have fragments of microcystin synthetase genes or mutations within these genes (22, 32, 50). These strains can be amplified with mcy primers, although they are not able to produce toxins. However, the significant positive correlation between the sum of Microcystis and Anabaena mcyE copy numbers and microcystin concentration indicated that such nontoxic strains were probably not numerous in Lakes Tuusulanjärvi and Hiidenvesi.

Microcystis mcyE QRT-PCR amplification efficiencies with Lake Tuusulanjärvi water samples (0.78 to 0.99) were similar to those of Microcystis standards (0.86 to 0.94) and Anabaena standards (0.96 to 0.99), which is a prerequisite for correct determination of the mcyE copy number in the lake water samples. These similar QRT-PCR amplification efficiencies also ensured that no PCR-inhibiting contaminants were present in the Lake Tuusulanjärvi DNA samples. However, Anabaena mcyE QRT-PCR amplification efficiencies with Lake Tuusulanjärvi water samples were higher than one. This result can be explained by competition for primer annealing sites between primers and closely related sequences (5, 49, 56), and this competition may lead to suppression of the target sequences, when they are not the most dominant in the community (49). This phenomenon has been shown to occur not only in conventional PCR (49) but also in QRT-PCR (5, 56), although quantification is achieved during the early logarithmic phase of the amplification (20). It is possible that the Anabaena mcyE copy numbers were underestimated in samples from Lake Tuusulanjärvi, since the number of competing Microcystis mcyE genes was higher than that of Anabaena mcyE genes and since Anabaena and Microcystis mcy genes have been demonstrated to be homologous (A. Rantala, D. P. Fewer, M. Hisbergues, L. Rouhiainen, J. Vaitomaa, T. Börner, and K. Sivonen, submitted for publication). In addition, the mcyE-F2 forward primer amplified Anabaena and Microcystis sequences and increased the amount of competing homologous sequences.

The mcyE QRT-PCR amplification was log linear in a range of 3 to 4 orders of magnitude. With a high DNA template concentration (6.6 × 106 mcyE copies in a reaction mixture), amplification was inhibited for DNA from Microcystis sp. strain GL 260735, Microcystis sp. strain PCC 7941, Anabaena sp. strain 90, and Anabaena sp. strain 202A1, since the obtained Ct values were lower than they should have been according to the regression equation or the Ct values could not be detected at all. The inhibition was probably caused by contaminants that coextracted with the DNA during the DNA extraction and purification as shown previously (58). The detection limit of Anabaena and Microcystis mcyE QRT-PCR amplification was 660 mcyE copies in a reaction mixture. The error of the Ct values in QRT-PCR has been shown to be higher with low DNA template concentrations than with high template concentrations (16). However, in this study, the lowest mcyE copy number concentrations of the standards (CV = 0.4 to 1.2%) were within the variations of the more dense DNA template concentrations (CV = 0.1 to 3.6%).

In this study, putative microcystin-producing Microcystis and Anabaena were detected in both of the lakes studied. In Lake Tuusulanjärvi, Microcystis was the dominant putative microcystin producer in the summer of 1999 based on mcyE quantification; the same result was found for the surface water of the Kiihkelyksenselkä Basin of Lake Hiidenvesi on 15 August 2001. Reduction of nutrient loading and resuspension (6, 8, 42) could be successful strategies to decrease the density of Microcystis, since these lake restoration strategies may decrease the nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations of the water. In addition, lower nutrient concentrations could favor the growth of nontoxic Microcystis strains instead of toxic ones, since at the end of a laboratory experiment with low nutrient concentrations, the biomass of nontoxic Microcystis strains has been demonstrated to be higher than that of toxic strains (54). Lake Hiidenvesi seemed to contain nontoxic and toxic Anabaena strains and toxic Microcystis strains. However, mcyE copy numbers should be monitored for a longer period of time in order to better understand the population dynamics in this lake. A reduction in the external phosphorus load could affect the mass occurrences of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria negatively. However, it is not known how the reduction of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria would affect the growth of toxic Microcystis strains. The presence of toxic Microcystis strains should at least be taken into account in the land use management of the catchment area of Lake Hiidenvesi.

In this study, a method based on the QRT-PCR technique and novel, genus-specific mcyE primers were used to ascertain the main putative microcystin producers in lakes. The dominant putative microcystin producer was Microcystis in Lake Tuusulanjärvi and in the Kiihkelyksenselkä Basin of Lake Hiidenvesi. In these lakes, lake restoration strategies, which would decrease the concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus in water, could be successful in decreasing the density of Microcystis. In the future, it would be interesting to observe the possible changes in cyanobacterial assemblages during and after lake restoration in order to determine whether the genus-targeted lake restoration succeeded. The method described in this study will also make possible studies of the environmental factors promoting the growth of toxic Microcystis and Anabaena in situ and studies monitoring the formation of the toxic mass occurrences.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported financially by the Academy of Finland (grants 46812 and 53305), the ABS Graduate School, and EU projects CYANOTOX (ENV4-CT98-0802) and MIDI-CHIP (EVK2-CT-1999-00026).

We are grateful to Anneliese Ernst for her inspiring ideas and suggestions on QRT-PCR. Chantal Vézie and Vitor Vasconcelos are acknowledged for allowing us to use a few of their strains in primer specificity testing. We thank the Uusimaa Regional Environment Centre for collecting water samples from Lake Tuusulanjärvi and providing phytoplankton analysis results. Christina Lyra, Jaana Lehtimäki, and David Fewer are warmly acknowledged for critically reading the manuscript and Lyudmila Saari for technical help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker, J. A., B. A. Neilan, B. Entsch, and D. B. McKay. 2001. Identification of cyanobacteria and their toxigenicity in environmental samples by rapid molecular analysis. Environ. Toxicol. 16:472-482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker, J. A., B. Entsch, B. A. Neilan, and D. B. McKay. 2002. Monitoring changing toxigenicity of a cyanobacterial bloom by molecular methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6070-6076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker, S., M. Fahrbach, P. Böger, and A. Ernst. 2002. Quantitative tracing, by Taq nuclease assays, of a Synechococcus ecotype in a highly diversified natural population. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4486-4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker, S., P. Böger, R. Oehlmann, and A. Ernst. 2000. PCR bias in ecological analysis: a case study for quantitative Taq nuclease assays in analyses of microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4945-4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boers, P., L. van Ballegooijen, and J. Uunk. 1991. Changes in phosphorus cycling in a shallow lake due to food web manipulations. Freshwater Biol. 25:9-20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castenholz, R. W. 2001. Phylum BX. Cyanobacteria. Oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria, p. 473-599. In D. R. Boone, R. W. Castenholz, and G. M. Garrity (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd edition, vol. 1. The Archaea and the deeply branching and phototrophic Bacteria. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 8.Chorus, I., and L. Mur. 1999. Preventative measures, p. 235-273. In I. Chorus and J. Bartram (ed.), Toxic cyanobacteria in water: a guide to their public health consequences, monitoring, and management. E & FN Spon, London, United Kingdom.

- 9.Christiansen, G., J. Fastner, M. Erhard, T. Börner, and E. Dittmann. 2003. Microcystin biosynthesis in Planktothrix: genes, evolution, and manipulation. J. Bacteriol. 185:564-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dittmann, E., B. A. Neilan, M. Erhard, H. von Döhren, and T. Börner. 1997. Insertional mutagenesis of a peptide synthetase gene that is responsible for hepatotoxin production in the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806. Mol. Microbiol. 26:779-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekman-Ekebom, M., M. Kauppi, K. Sivonen, M. Niemi, and L. Lepistö. 1992. Toxic cyanobacteria in some Finnish lakes. Environ. Toxicol. Water Qual. 7:201-213. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falconer, I., J. Bartram, I. Chorus, T. Kuiper-Goodman, H. Utkilen, M. Burch, and G. A. Codd. 1999. Safe levels and safe practices, p. 155-178. In I. Chorus and J. Bartram (ed.), Toxic cyanobacteria in water: a guide to their public health consequences, monitoring, and management. E & FN Spon, London, United Kingdom.

- 13.Fastner, J., M. Erhard, and H. von Döhren. 2001. Determination of oligopeptide diversity within a natural population of Microcystis spp. (cyanobacteria) by typing single colonies by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5069-5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giovannoni, S. J., E. F. DeLong, T. M. Schmidt, and N. R. Pace. 1990. Tangential flow filtration and preliminary phylogenetic analysis of marine picoplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:2572-2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg, J., H. Huang, Y. Kwon, P. Greengard, A. C. Nairn, and J. Kuriyan. 1995. Three-dimensional structure of the catalytic subunit of protein serine/threonine phophatase-1. Nature 376:745-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grüntzig, V., S. C. Nold, J. Zhou, and J. M. Tiedje. 2001. Pseudomonas stutzeri nitrite reductase gene abundance in environmental samples measured by real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:760-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gugger, M., C. Lyra, P. Henriksen, A. Couté, J.-F. Humbert, and K. Sivonen. 2002. Phylogenetic comparison of the cyanobacterial genera Anabaena and Aphanizomenon. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:1867-1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall, T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harada, K.-I., F. Kondo, and L. Lawton. 1999. Laboratory analysis of cyanotoxins, p. 369-405. In I. Chorus and J. Bartram (ed.), Toxic cyanobacteria in water: a guide to their public health consequences, monitoring, and management. E & FN Spon, London, United Kingdom.

- 20.Heid, C. A., J. Stevens, K. J. Livak, and P. M. Williams. 1996. Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res. 6:986-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herdman, M., M. Janvier, R. Rippka, and R. Y. Stanier. 1979. Genome size of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 111:73-85. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaebernick, M., T. Rohrlack, K. Christoffersen, and B. A. Neilan. 2001. A spontaneous mutant of microcystin biosynthesis: genetic characterization and effect on Daphnia. Environ. Microbiol. 3:669-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotai, J. 1972. Instructions for preparation of modified nutrient solution Z8 for algae, p. 5. Norwegian Institute for Water Research publication B-11/69. Norwegian Institute for Water Research, Oslo, Norway.

- 24.Kuiper-Goodman, T., I. Falconer, and J. Fitzgerald. 1999. Human health aspects, p. 113-153. In I. Chorus and J. Bartram (ed.), Toxic cyanobacteria in water: a guide to their public health consequences, monitoring, and management. E & FN Spon, London, United Kingdom.

- 25.Kurmayer, R., E. Dittmann, J. Fastner, and I. Chorus. 2002. Diversity of microcystin genes within a population of the toxic cyanobacterium Microcystis spp. in Lake Wannsee (Berlin, Germany). Microb. Ecol. 43:107-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labarre, J., F. Chauvat, and P. Thuriaux. 1989. Insertional mutagenesis by random cloning of antibiotic resistance genes into the genome of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 171:3449-3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lahti, K., J. Rapala, M. Färdig, M. Niemelä, and K. Sivonen. 1997. Persistence of cyanobacterial hepatotoxin, microcystin-LR in particulate material and dissolved in lake water. Water Res. 31:1005-1012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, S. J., M.-H. Jang, H.-S. Kim, B.-D. Yoon, and H.-M. Oh. 2000. Variation of microcystin content of Microcystis aeruginosa relative to medium N:P ratio and growth stage. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89:323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyra, C., S. Suomalainen, M. Gugger, C. Vezie, P. Sundman, L. Paulin, and K. Sivonen. 2001. Molecular characterization of planktic cyanobacteria of Anabaena, Aphanizomenon, Microcystis and Plantothrix genera. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:513-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Namikoshi, M., K. L. Rinehart, R. Sakai, R. R. Stotts, A. M. Dahlem, V. R. Beasley, W. W. Carmichael, and W. R. Evans. 1992. Identification of 12 hepatotoxins from a Homer Lake bloom of the cyanobacteria Microcystis aeruginosa, Microcystis viridis, and Microcystis wesenbergii: nine new microcystins. J. Org. Chem. 57:866-872. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neilan, B. A., D. Jacobs, T. del Dot, L. L. Blackall, P. R. Hawkins, P. T. Cox, and A. E. Goodman. 1997. rRNA sequences and evolutionary relationships among toxic and nontoxic cyanobacteria of the genus Microcystis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:693-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neilan, B. A., E. Dittmann, L. Rouhiainen, R. A. Bass, V. Schaub, K. Sivonen, and T. Börner. 1999. Nonribosomal peptide synthesis and toxigenicity of cyanobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 181:4089-4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishizawa, T., A. Ueda, M. Asayama, K. Fujii, K. Harada, K. Ochi, and M. Shirai. 2000. Polyketide synthase gene coupled to the peptide synthetase module involved in the biosynthesis of the cyclic heptapeptide microcystin. J. Biochem. 127:779-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishizawa, T., M. Asayama, K. Fujii, K.-I. Harada, and M. Shirai. 1999. Genetic analysis of the peptide synthetase genes for a cyclic heptapeptide microcystin in Microcystis spp. J. Biochem. 126:520-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nonneman, D., and P. V. Zimba. 2002. A PCR-based test to assess the potential for microcystin occurrence in channel catfish production ponds. J. Phycol. 38:230-233. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nübel, U., F. Garcia-Pichel, and G. Muyzer. 1997. PCR primers to amplify 16S rRNA genes from cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3327-3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohtake, A., M. Shirai, T. Aida, N. Mori, K.-I. Harada, K. Matsuura, M. Suzuki, and M. Nakano. 1989. Toxicity of Microcystis species isolated from natural blooms and purification of the toxin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:3202-3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan, H., L. Song, Y. Liu, and T. Börner. 2002. Detection of hepatotoxic Microcystis strains by PCR with intact cells from both culture and environmental samples. Arch. Microbiol. 178:421-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rapala, J., and K. Sivonen. 1998. Assessment of environmental conditions that favor hepatotoxic and neurotoxic Anabaena spp. strains cultured under light limitation at different temperatures. Microb. Ecol. 36:181-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapala, J., K. Sivonen, C. Lyra, and S. I. Niemelä. 1997. Variation of microcystins, cyanobacterial hepatotoxins in Anabaena spp. as a function of growth stimuli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2206-2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Repka, S., J. Mehtonen, J. Vaitomaa, L. Saari, and K. Sivonen. 2001. Effects of nutrients on growth and nodularin production of Nodularia strain GR8b. Microb. Ecol. 42:606-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds, C. S. 1997. Vegetation processes in the pelagic: a model for ecosystem theory. Book 9. Excellence in Ecology series. International Ecology Institute, Oldendorf, Germany.

- 43.Rippka, R., and M. Herdman. 1992. Pasteur culture collection of cyanobacterial strains in axenic culture, p. 103. Catalogue and taxonomic handbook, vol. I. Catalogue of strains 1992/1993. Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

- 44.Rouhiainen, L., K. Sivonen, W. J. Buikema, and R. Haselkorn. 1995. Characterization of toxin-producing cyanobacteria by using an oligonucleotide probe containing a tandemly repeated heptamer. J. Bacteriol. 177:6021-6026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sivonen, K., and G. Jones. 1999. Cyanobacterial toxins, p. 41-111. In I. Chorus and J. Bartram (ed.), Toxic cyanobacteria in water: a guide to their public health consequences, monitoring, and management. E & FN Spon, London, United Kingdom.

- 46.Sivonen, K., K. Himberg, R. Luukkainen, S. I. Niemelä, G. K. Poon, and G. A. Codd. 1989. Preliminary characterization of neurotoxic cyanobacteria blooms and strains from Finland. Toxic. Assess. 4:339-352. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sivonen, K., M. Namikoshi, R. Luukkainen, M. Färdig, L. Rouhiainen, W. R. Evans, W. W. Carmichael, K. L. Rinehart, and S. I. Niemelä. 1995. Variation of cyanobacterial hepatotoxins in Finland, p. 163-169. In M. Munavar and M. Luotola (ed.), The contaminants in the nordic ecosystem: dynamics, processes and fate. Ecovision World Monograph Series. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management Society, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 48.Sivonen, K., W. W. Carmichael, M. Namikoshi, K. L. Rinehart, A. M. Dahlem, and S. I. Niemelä. 1990. Isolation and characterization of hepatotoxic microcystin homologs from the filamentous freshwater cyanobacterium Nostoc sp. strain 152. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:2650-2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki, M. T., and S. J. Giovannoni. 1996. Bias caused by template annealing in the amplification of mixtures of 16S rRNA genes by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:625-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tillett, D., D. L. Parker, and B. A. Neilan. 2001. Detection of toxigenicity by a probe for the microcystin synthetase A gene (mcyA) of the cyanobacterial genus Microcystis: comparison of toxicities with 16 rRNA and phycocyanin operon (phycocyanin intergenic spacer) phylogenies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2810-2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tillett, D., E. Dittmann, M. Erhard, H. von Döhren, T. Börner, and B. A. Neilan. 2000. Structural organization of microcystin biosynthesis in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806: an integrated peptide-polyketide synthetase system. Chem. Biol. 7:753-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Utermöhl, H. 1958. Zur Vervollkommnung der quantitativen Phytoplankton-Methodik. Mitt. Int. Ver. Limnol. 9:1-38. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vasconcelos, V. M., K. Sivonen, W. R. Evans, W. W. Carmichael, and M. Namikoshi. 1995. Isolation and characterization of microcystins (heptapeptide hepatotoxins) from Portuguese strains of Microcystis aeruginosa KUTZ. emend ELEKIN. Arch. Hydrobiol. 134:295-305. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vézie, C., J. Rapala, J. Vaitomaa, J. Seitsonen, and K. Sivonen. 2002. Effect of nitrogen and phosphorus on growth of toxic and nontoxic Microcystis strains and on intracellular microcystin concentrations. Microb. Ecol. 43:443-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vezie, C., L. Brient, K. Sivonen, G. Bertru, J.-C. Lefeuvre, and M. Salkinoja-Salonen. 1998. Variation of microcystin content of cyanobacterial blooms and isolated strains in Lake Grand-Lieu (France). Microb. Ecol. 35:126-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wawrik, B., J. H. Paul, and F. R. Tabita. 2002. Real-time PCR quantification of rbcL (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) mRNA in diatoms and pelagophytes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3771-3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Willén, T. 1962. Studies on the phytoplankton of some lakes connected with or recently isolated from the Baltic. Oikos 13:169-199. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wintzingerode, F., U. B. Göbel, and E. Stackebrandt. 1997. Determination of microbial diversity in environmental samples: pitfalls of PCR-based rRNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 21:213-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]