Abstract

Community structures of submerged microbial slime streamers (SMSS) in sulfide-containing hot springs at 72 to 80°C at Nakabusa and Yumata, Japan, were investigated by molecular analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene. The SMSS were classified into two consortia; consortium I occurred at lower levels of sulfide in the hot springs (less than 0.1 mM), and consortium II dominated when the sulfide levels were higher (more than 0.1 mM). The dominant cell morphotypes in consortium I were filamentous and small rod-shaped cells. The filamentous cells hybridized with fluorescent oligonucleotide probes for the domain Bacteria, the domain Archaea, and the family Aquificaceae. Our analysis of the denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) bands by using reverse transcription (RT)-PCR amplification with two primer sets (Eub341-F with the GC clamp and Univ907R for the Bacteria and Eub341-F with the GC clamp and Arch915R) indicated that dominant bands were phylogenetically related to microbes in the genus Aquifex. On the other hand, consortium II was dominated by long, small, rod-shaped cells, which hybridized with the oligonucleotide probe S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 developed in this study for the majority of as-yet-uncultivated microbes in the class Thermodesulfobacteria. The dominant DGGE band obtained by PCR and RT-PCR was affiliated with the genus Sulfurihydrogenibium. Moreover, our analysis of dissimilatory sulfite reductase (DSR) gene sequences retrieved from both consortia revealed a high frequency of DSR genes corresponding to the DSR of Thermodesulfobacteria-like microorganisms. Using both sulfide monitoring and 35SO42− tracer experiments, we observed microbial sulfide production and consumption by SMSS, suggesting that there is in situ sulfide production by as-yet-uncultivated Thermodesulfobacteria-like microbes and there is in situ sulfide consumption by Sulfurihydrogenibium-like microbes within the SMSS in the Nakabusa and Yumata hot springs.

Over the past decade, studies of the microbiology of high-temperature terrestrial hot springs by both molecular-ecological and culture-based approaches have revealed phylogenetic and physiological diversity (20-23, 32, 37, 38, 40, 55). While culture-dependent approaches are effective for physiological characterization of isolated thermophiles, they are not useful for providing comprehensive ecophysiological information about the microbial populations in thermophilic environments. One reason for this is that cultivated microbes from high-temperature habitats may frequently represent minor members of a microbial community whose representation is similar to the representation found in the native setting (52).

Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), which obtain energy from dissimilatory sulfate reduction, are widespread in anoxic environments and play an important role in the sulfur cycle (53). Several strains belonging to the genus Thermodesulfobacterium, which includes thermophilic and gram-negative SRB, have been isolated from sediments and filamentous microbial communities in terrestrial hot springs (41, 56). As previously reported, as-yet-uncultivated microbes in the class Thermodesulfobacteria which are less closely related to the cultivated Thermodesulfobacterium species were found in the submerged microbial slime streamers (SMSS) in an alkaline sulfide-containing hot spring in Nakabusa, Japan (32). However, relatively little has been reported about the (eco)physiology of as-yet-uncultivated Thermodesulfobacteria-like microbes found in SMSS in terrestrial hot springs due to the difficulty of successfully isolating them. Dissimilatory sulfite reductase (DSR) is a key enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of sulfite to sulfide during anaerobic sulfate respiration. The use of DSR gene-based molecular ecological techniques can help us detect sulfate-reducing prokaryotes (SRP) in a complex microbial community and to assess the potential for in situ biological sulfide production through anaerobic sulfate respiration by SRP. Indeed, sequence analysis of DSR genes has been successfully used to detect SRP in complex habitats (5, 9, 11-14, 24, 30, 33, 49).

The occurrence of sulfur mats (“sulfur turf”) consisting mainly of microorganisms and sulfur compounds auto-oxidized by molecular oxygen in sulfide-rich hot springs has been described previously (28, 40, 55). Several sequence types (phylotypes) in the class Aquificae retrieved from white and yellow sulfur turf in Icelandic and Japanese hot springs (40, 55) form a branch separate from the family Aquificaceae lineage; this branch includes Hydrogenobacter hydrogenophilum (26), Hydrogenobacter thermophilus (25), and Thermocrinis ruber (22) isolated from sulfide-poor terrestrial hot springs. There have been several reports concerning the presence of phylotypes related to the sulfur turf clones retrieved from terrestrial hot springs (20, 32, 37, 40) and geothermal water (29, 33, 45). Recently, a strain of Sulfurihydrogenibium subterraneum, a facultatively anaerobic, hydrogen- or sulfur-thiosulfate-oxidizing, thermophilic chemolithoautotroph, was isolated from subsurface hot aquifer water in a Japanese gold mine (46).

Long filamentous and rod-shaped thermophilic microbes have often been observed in microbial streamers occurring in various terrestrial hot springs (22, 32, 38, 44). However, it is difficult by using only PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) analysis based on 16S rRNA genes to clarify the community structure of these organisms from the filamentous materials that coexist with long filaments and rods whose cell sizes vary greatly. The results of PCR amplification reflect the abundance of 16S rRNA genes in microbial communities (including active and inactive microbes) in such an environment. In contrast, the results of reverse transcription (RT)-PCR amplification reflect the composition of the 16S rRNAs and metabolically active microbes in microbial communities better than the results of analyses of genomic DNAs because of the higher number of ribosomes in metabolically active microbes than in latent microbes (16).

The aims of the present study were to clarify such microbial community structures and the dynamics of the composition of the SMSS in the terrestrial sulfide-containing hot springs in Nakabusa and Yumata, Japan, by using PCR and RT-PCR-DGGE analysis combined with a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay and to determine the contribution to biological sulfide production and consumption by the SMSS dominated by the microbes affiliated with the Thermodesulfobacteria and Sulfurihydrogenibium. Below we discuss whether the dominant microbes (filaments and rods) in microbial streamers could be detected as an abundant band on a DGGE gel by using the RT-PCR-DGGE approach combined with FISH analysis. Fluorescent oligonucleotide probes specific for the 16S ribosomal DNAs (rDNAs) obtained by using the RT-PCR-DGGE approach were employed to determine the sequences corresponding to the filaments and rods. We developed a probe for several as-yet-uncultivated thermophilic microbes in the class Thermodesulfobacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study areas and sample collection.

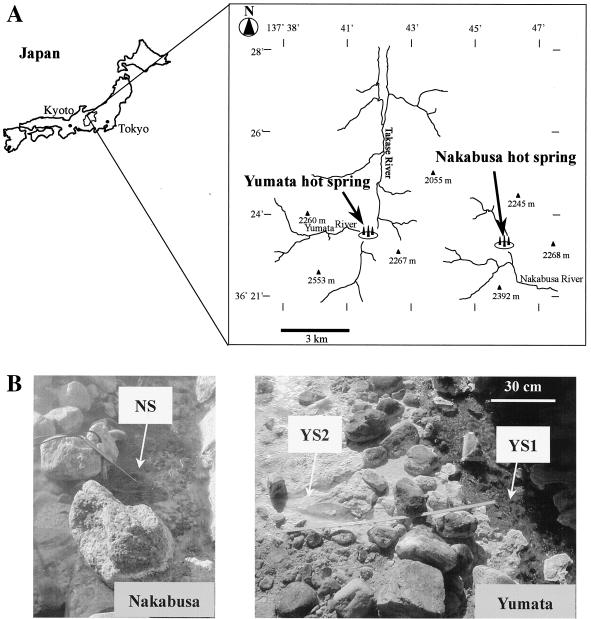

The study areas were Nakabusa (altitude, 1,400 m; 36°23′10"N, 137°45′00"E), an alkaline sulfide-containing hot spring, and Yumata (altitude, 1,440 m; 36°23′35"N, 137°40′40"E), a neutral-pH sulfide-rich hot spring, which are located in the Japanese North Alps in Nagano Prefecture (Fig. 1A). The occurrence of green, white, orange, and gray dense mats and streamers in Nakabusa was reported previously (32). The dense SMSS developed under the sulfide-containing spring water (Fig. 1B). SMSS were collected from the spring pool in July and November 2000, in May, September, and November 2001, and in June 2002. The growth of whitish, yellowish, blackish, and grayish dense mats in the Yumata spring was reported previously (19). Dense SMSS developed at site YS1 under running sulfide-rich spring water (Fig. 1B). White sulfur mats (WSM) developed at site YS2. White and/or yellow sulfur compounds were scarcer in the SMSS than in the WSM. The microbial mats and streamers were collected from sites YS1 and YS2 in August 2001 and August 2002. Each microbial streamer sample was kept in a sterile plastic tube (50 ml) with spring water to prevent the oxidation. Spring water used for inorganic analyses was immediately filtered with a Millex-GP filter (pore size, 0.2 μm; Millipore) and collected in a plastic tube without a headspace. Spring water (7 ml) was immediately fixed with 3 ml of a 20% (wt/vol) zinc acetate solution for sulfate analysis and was fixed with the same volume of a 90 mM zinc acetate solution for determination of the sulfide concentration. In situ spring water used in the test for sulfide production and consumption by the SMSS was kept in a sterile plastic bottle (1,000 ml). All capped tubes were stored at 4°C and transferred to our laboratory within 1 day after sampling. The microbial streamers used for molecular analysis were kept in 1.5-ml centrifuge tubes and then frozen at −20°C until DNA was extracted or at −80°C until RNA was extracted.

FIG. 1.

(A) Map showing the locations of the Nakabusa and Yumata hot springs in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. (B) Photographs showing the sampling sites at the two hot spring. SMSS occurred at sites NS and YS1, while WSM occurred at site YS2.

FISH.

After SMSS were homogenized briefly with homogenization pestles, dehydration and in situ hybridization were performed by using the procedure described by Amann et al. (3, 4). Fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotide probes S-D-Bact-0338-a-A-18 for the domain Bacteria (42) and S-D-Arch-0915-a-A-20 for the domain Archaea (42) were used. Rhodamine-labeled oligonucleotide probe S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 for most of the uncultured microbes in the class Thermodesulfobacteria was developed in the present study to examine the microbes corresponding to DGGE bands NAB12, NAB13, and YSd (Table 1). Cells of the reference strains Catellatospora ferruginea DSM44099 and Thermodesulfobacterium commune DSM2178 were employed as negative controls in the hybridization analysis. The optimal formamide concentration was determined by varying the formamide concentration from 0 to 60% and by comparing the fluorescent signals for the microbes from the SMSS and the fluorescent signals for nonspecific hybridizations with negative controls. Fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotide probe S-O-Hydr-0540-a-A-19 (18) was used to examine the microbes corresponding to DGGE bands NAB-RT-1 and NAB-RT-2. Cells of Escherichia coli were employed as negative controls for hybridization. The hybridization buffer (0.9 M NaCl, 0.1 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], formamide at different concentrations [Table 1], 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) contained 2.5 ng of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probe per μl. After hybridization for 2 h at 46°C, the slides were washed with washing buffer (NaCl at different concentrations [Table 1], 0.1 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) for 20 min at 48°C. The samples were examined by phase-contrast microscopy and epifluorescence microscopy (Axioplan 2; Zeiss).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for FISH in this study and the 16S rRNA sequences of target and nontarget species

| Probe, target and nontarget organism(s), or environmental clone(s) (accession no.)a | Target sequenceb | Formamide concn (%)c | NaCl concn (mM)d | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 | 3′ GAGAGACCCGGCTTCGATTG 5′ | 20 | 215 | This study |

| NAB12, NAB13, NAB19, NAB20, NAB28 | 5′ CUCUCUGGGCCGAAGCUAAC 3′ | |||

| YSd | 5′ -------------------- 3′ | |||

| OPB45 (AF027096) | 5′ -------------------- 3′ | |||

| OPS7 (AF027095) | 5′ -------------------- 3′ | |||

| OPT4, OPT53 (AF027093, AF027094) | 5′ -------------------- 3′ | |||

| DGG19 (AY082369) | 5′ -------------------- 3′ | |||

| SRI-27, SRI-93 (AF255595, AF255596) | 5′ -------------------- 3′ | |||

| Catellatospora ferruginea DSM44099 | 5′ -------U----C------- 3′ | |||

| Thermodesulfobacterium commune DSM2178 | 5′ GC-----U----U------- 3′ | |||

| S-O-Hydr-0540-a-A-19 | 3′ CCAGGGCTCGCAACGCGCT 5′ | 60 | 4 | 18 |

| NAB-RT-1, NAB-RT-2 | 5′ GGUCCCGAGCGUUGCGCGA 3′ | |||

| Hydrogenobacter thermophilus DSM6534 | 5′ ------------------- 3′ | |||

| Aquifex pyrophilus DSM6858 | 5′ ------------------- 3′ | |||

| Bacteria | 3′ TGAGGATGCCCTCCGTCG 5′ | 20 | 215 | 42 |

| Archaea | 3′ TCCTTAACCGCCCCCTCGTG 5′ | 35 | 70 | 42 |

The S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 sequence is the target sequence for the first group, and the S-O-Hydr-0540-a-A-19 sequence is the target sequence for the second group. The probes for Bacteria and Archaea were S-D-Bact-0338-a-A-18 and S-D-Arch-0915-a-A-20, respectively. Probe nomenclature is based on the oligonucleotide probe database (1).

Sequence data are from the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database. Dashes indicate identical nucleotides, and letters indicate nucleotide differences from the target sequence.

Formamide concentration in the hybridization buffer.

Sodium chloride concentration in the washing buffer.

Extraction of nucleic acids.

After microbial streamers and mats were homogenized with homogenization pestles on ice and cells were harvested by centrifugation, the nucleic acids were extracted as described by Wilson (54). The extracted nucleic acids were stored at −20°C until the PCR was performed. Total RNAs were extracted from samples by a bead-beating, low-pH, phenol-chloroform extraction procedure (43). After DNAs in the samples were digested with DNase I (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan) for 1 h at 37°C, the total RNAs were extracted by a low-pH, phenol-chloroform extraction procedure.

PCR and RT-PCR amplification.

DNA fragments encoding 16S rRNAs of members of the domain Bacteria and the domain Archaea were amplified by using two sets of primers, as follows: Eub341F with the GC clamp and Univ907R for the domain Bacteria (31) and Arch344F with the GC clamp and Arch915R for the domain Archaea (8, 35, 42). The PCR conditions used for the bacterial and archaeal primers were those described by Muyzer et al. (31) and Casamayor et al. (8), respectively. PCR amplification was performed with 100-μl mixtures containing 1 to 10 ng of template DNA, 1× EX Taq buffer (Takara), each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 250 μM, 25 pmol of each primer, 2.5 U of EX Taq DNA polymerase (Takara), and 2 drops of mineral oil (Sigma). PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 2% (wt/vol) Nusieve 3:1 agarose (FMC, Rockland, Maine) gels containing ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml).

The DSR gene was amplified with primers DSR1F and DSR4R as described previously (51). The PCR conditions used for DSR gene amplification were 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 54°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 3 min. The reaction was completed by a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. For DSR PCR amplification, 1× EX Taq buffer (Takara), 1 to 10 ng of template DNA, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 250 μM, 25 pmol each of the primer, and 2.5 U of EX Taq DNA polymerase (Takara) were combined in 50-μl (final volume) mixtures. The DSR gene fragments were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.1% (wt/vol) agarose S (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) gels containing ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml).

RT-PCR was performed with RNAs isolated from the SMSS and WSM by using the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The 16S rDNA fragments were amplified as follows: 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 54°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 3 min. The reaction was completed by a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR primers used were Eub341F-GC and Univ907R for the domain Bacteria and Arch344F with the GC clamp and Arch915R for the domain Archaea. The PCR primers Eub341F-GC and Arch915R were used to detect the filamentous bacteria that hybridized with both fluorescently labeled probe S-D-Bact-0338-a-A-18 for the domain Bacteria and fluorescently labeled probe S-D-Arch-0915-a-A-20 for the domain Archaea. The RNA samples from the SMSS were PCR amplified without the cDNA synthesis step to check for DNA contamination. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 2% (wt/vol) Nusieve 3:1 agarose (FMC) gels containing ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml).

DGGE analysis of 16S rDNA fragments.

DGGE was performed as described by Muyzer et al. (31) by using D-code systems (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) with a 1.5-mm gel. Approximately 100- to 500-ng portions of PCR products were applied directly onto 6% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels with denaturing gradients from 20 to 60% (100% denaturant was 7 M urea and 40% [vol/vol] deionized formamide). Electrophoresis was performed with 0.5× TAE buffer (20 mM Tris, 10 mM acetic acid, 0.5 mM EDTA; pH 8.3) at 200 V and 60°C for 4 h. After electrophoresis, the gels were incubated for 10 min in ethidium bromide (1.0 mg/liter), rinsed for 10 min in distilled water, and then photographed with UV transillumination (wavelength, 312 nm) by using a charge-coupled device camera (Image Server; ATTO, Tokyo, Japan).

DGGE bands were excised from the gels and reamplified by using primers Eub341F with the GC clamp and Univ907R, primers Arch344F with the GC clamp and Arch915R, and primers Eub341F with the GC clamp and Arch915R. After the PCR products of the second amplification were electrophoresed again in a DGGE gel to check the purity of the bands, the PCR amplification mixtures were purified with a CONCERT rapid PCR purification kit (Invitrogen).

Cloning and restriction digestion.

PCR products (∼1.9 kb) encoding the DSR gene were purified with a CONCERT rapid PCR purification kit (Invitrogen). The DSR gene products were cloned as described previously (33), and insert-containing clones reamplified with the vector primers M13 reverse and M13(-20) forward were screened by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis by using restriction endonucleases AluI and MspI as described previously (33).

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

Nucleotide sequencing was performed with an ABI PRISM BigDye terminator cycle sequencing Ready Reaction kit and an ABI model 377 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems) used according to the manufacturer's instructions. 16S rDNA fragments from DGGE bands were sequenced by using primers Eub341F, Univ907R, Arch344F, and Arch915R. Partial sequences of DSR amplification products were sequenced by using the vector primers M13 reverse, M13(-20) forward, DSR1F, and DSR4R and the internal primers TNdsr1150r1 (33) and TNdsr1150r2 (5′-ATTAATACAGTGCATACA-3′). Approximately 700 nucleotides was sequenced for each strand. The sequences obtained from DGGE bands and the deduced amino acid sequences encoded by α-subunits of DSR genes were entered into the BLAST programs (2) and the FASTA programs (27) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information and the DNA Data Bank of Japan in order to identify phylogenetic relatives. Sequence alignments with parts of 16S rRNA and deduced DSR amino acid sequences of reference prokaryotes from the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases and matrices of evolutionary distance were constructed by using a CLUSTAL W program (48). Evolutionary distances were determined by the neighbor-joining method (39). Phylogenetic trees were constructed from the evolutionary distances by using Tree View software (34). Bootstrap resampling analysis for 1,000 replicates was performed to estimate the confidence of tree topologies.

Analytical methods.

The in situ temperature and pH of hot spring water were measured by the electrode method by using a pH meter (WM-22EP; TOA Electronics, Tokyo, Japan). Sulfate and nitrate ion concentrations were determined by ion chromatography (Dionex, Sunnyvale, Calif.). Dissolved sulfide concentrations were measured colorimetrically by using the methylene blue formation reaction method (10) after in situ fixation with a zinc acetate solution.

Sulfide monitoring of SMSS.

After the headspace of a sterile serum bottle (50 ml) was replaced with N2 gas, approximately 30 ml of in situ spring water from Nakabusa was added to the bottle, which was sealed with a butyl rubber stopper, under a headspace of N2 gas. Approximately 1 g of an SMSS was placed in the bottle, which was subsequently sealed with a butyl rubber stopper, under a headspace of N2 gas. A sterile control bottle was autoclaved at 121°C for 30 min. An anaerobic sulfate solution was added to the sulfate-amended bottles at a final concentration of approximately 5 mM. Sterile serum bottles (150 ml) containing N2 gas, approximately 120 ml of in situ spring water, and approximately 5 g of the SMSS were incubated in situ in spring water in June 2002. The control bottle was incubated at room temperature for approximately 2 h. Subsamples (0.1 ml of medium water) were withdrawn with sterile nitrogen-flushed syringes during the incubation in a water bath at the in situ temperatures. The subsamples used for in situ sulfide monitoring were immediately fixed with 0.1 ml of a 90 mM zinc acetate solution for sulfide analysis. Sulfide concentrations in the water were measured colorimetrically by the methylene blue formation reaction method (10). The tests for sulfide production by the SMSS were conducted within 2 days after sampling. We checked to make sure that the pH of the spring water after the test was approximately 8.0.

SRR.

To measure the sulfate reduction rate (SRR) in the SMSS, approximately 40 μCi of carrier-free 35SO42− was added to three series of 50-ml sterile serum bottles sealed with butyl rubber stoppers under a headspace of N2 gas; these bottles contained approximately 30 ml of in situ spring water and approximately 1 g of the SMSS. The sterile control bottles were autoclaved at 121°C for 30 min. An anaerobic Na2MoO4 solution was added to the molybdate-amended bottles at a final concentration of approximately 0.5 mM. After 284 min of incubation, the reactions were terminated by injecting 3 ml of 20% (wt/vol) anoxic zinc acetate into the bottles to fix the ∑H2S produced as ZnS (∑H2S = H2S + HS− + S2−) and to inhibit further microbial activity, and then the preparations were kept at −20°C until analysis of 35Sred (35Sred = ∑H2S + FeS + S0 + FeS2) by a chromium reduction procedure under cold acid with Cr2+ (15). After the substance in a bottle was melted and the contents of the bottle were vigorously mixed, 4 ml of the suspension was placed into an Erlenmeyer flask (50 ml) charged with N2 gas. The 35Sred was liberated as H2S and absorbed by filter paper soaked with 0.7 ml of 1 M zinc acetate after incubation for 24 h. To determine the radioactivity of sulfate, 0.1-ml portions of the suspension were placed into 1.6-ml plastic tubes. After addition of 0.05 ml of 10 N NaOH to each of the tubes and centrifugation, 10 μl of the supernatant was transferred to a vial containing 3 ml of a scintillation cocktail for analysis of 35SO42−. The filter paper with 35Sred was placed into the vial with 3 ml of scintillation cocktail for analysis of 35Sred. The SRR (in nanomoles per gram [wet weight] of streamers per hour) was calculated as described by Fossing and Jøorgensen (15).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The rRNA and DSR gene sequences have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under the following accession numbers: AB081520, AB081521, AB081524 to AB081530, AB089185, AB090354, and AB090355 for 16S rRNA genes and AB081522, AB081523, AB081531 to AB081533, and AB089186 for dsrA genes.

RESULTS

Changes in environmental characteristics of spring water and cell morphotypes in the SMSS.

The temperature and pH of the spring water at Nakabusa showed little fluctuation during the present study (Table 2). However, the concentrations of sulfide in the spring water in November 2000, November 2001, and June 2002 were higher than those at other times. In contrast, the concentrations of sulfate in the spring water tended to increase when the sulfide concentrations were lower. Nitrate was not detected during the investigation. The major morphotypes were filamentous and rod-shaped cells of various sizes in July 2000 and May and September 2001, when the sulfide concentration was less than 0.1 mM (consortium I) (Fig. 2A). Numerous longer rod-shaped cells (length, 4.7 ± 1.0 μm; width, 2.3 ± 0.6 μm) were found in November 2000, November 2001, and June 2002, when the sulfide concentration was more than 0.1 mM (consortium II) (Fig. 2B). The shorter rod-shaped cells (length, 2.7 ± 0.5 μm; width, 1.5 ± 0.3 μm) occurred consistently in all samples during the investigation.

TABLE 2.

Physicochemical characteristics of spring water at the Nakabusa and Yumata sampling sites in Japan during this study

| Sampling site | Date | Temp (°C) | Dissolved sulfide concn (mM) | Sulfate concn (mM) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | July 2000 | 76 | 0.077 ± 0.020 (3) | NDa | 8.5 |

| November 2000 | 72 | 0.123 (2)b | ND | 8.8 | |

| May 2001 | 76 | 0.046 (1) | 0.204 (1) | 8.7 | |

| September 2001 | 76 | 0.087 ± 0.002 (3) | 0.104 ± 0.038 (3) | 8.8 | |

| November 2001 | 77 | 0.278 ± 0.068 (3) | 0.019 ± 0.007 (3) | 8.6 | |

| June 2002 | 77 | 0.112 ± 0.013 (3) | 0.179 ± 0.009 (3) | 8.4 | |

| YS1 | August 2001 | 78 | 0.278 ± 0.068 (3) | 0.081 ± 0.048 (3) | 6.6 |

| August 2002 | 80 | 0.684 ± 0.050 (3) | 0.076 (1) | 6.3 | |

| YS2 | August 2001 | 70 | 0.130 ± 0.013 (3) | 0.130 ± 0.050 (3) | 6.6 |

| August 2002 | 71 | ND | ND | 7.7 |

ND, not determined.

The numbers in parentheses are numbers of samples.

FIG. 2.

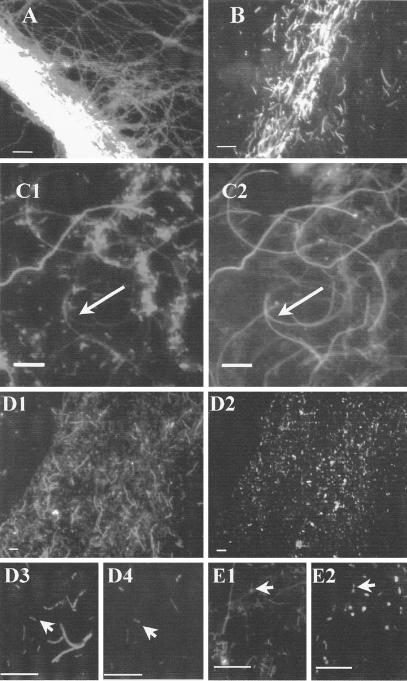

Epifluorescence microscopic images of SMSS in the Nakabusa hot spring. (A and B) Images of SMSS (consortium I) in May 2001 (A) and of SMSS (consortium II) in June 2002 (B) obtained with DAPI. (C1 and C2) Images of homogenized SMSS in May 2001 obtained with DAPI (C1) and with fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotide probe S-O-Hydr-0540-a-A-19 (C2). The filamentous cell that hybridized with probe S-O-Hydr-0540-a-A-19 indicated by the arrow in panel C2 corresponds to the cell indicated by the arrow in panel C1. (D1 to D4) Images of the homogenized SMSS in June 2002 obtained with DAPI (D1 and D3) and with rhodamine-labeled oligonucleotide probe S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 (D2 and D4). The small rod that hybridized with probe S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A indicated by the arrow in panel D4 corresponds to the cell indicated by the arrow in panel D3. (E1 and E2) Images of homogenized SMSS in May 2001 obtained with DAPI (E1) and with rhodamine-labeled oligonucleotide probe S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 (E2). The small rods that hybridized with probe S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A indicated by the arrow in panel E2 correspond to the cells indicated by the arrow in panel E1. Bars, 10 μm.

The in situ water temperature at site YS1 at Yumata (78 and 80°C) was slightly higher than that at site YS2. The sulfide concentrations in the spring water at site YS1 were more than 0.1 mM. Phase-contrast microscopy revealed high numbers of longer rod-shaped cells that varied from 5 to 12 μm long and shorter rod-shaped cells (ca. 0.2 by 2 μm) in the SMSS at site YS1, as observed for consortium II at Nakabusa. Similarly, high numbers of longer rod-shaped cells were observed in the WSM at site YS2.

FISH.

The filamentous cells from Nakabusa hybridized with both fluorescently labeled probes, S-D-Bact-0338-a-A-18 for the domain Bacteria and S-D-Arch-0915-a-A-20 for the domain Archaea. However, these cells produced weak fluorescent signals when they were hybridized with the S-D-Bact-0338-a-A-18 probe. Moreover, they hybridized with fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotide probe S-O-Hydr-0540-a-A-19 (Fig. 2C1 and C2). The cells that were longer rods and shorter rods at Nakabusa and Yumata hybridized with the fluorescently labeled probe S-D-Bact-0338-a-A-18. The longer rod-shaped cells produced weak fluorescent signals when they were hybridized with the S-D-Bact-0338-a-A-18 probe. Probe S-D-Arch-0915-a-A-20 for the domain Archaea resulted in no positive signals from cells of the SMSS at site YS1 at Yumata. The formamide concentration for the rhodamine-labeled oligonucleotide probe S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 was optimized by comparing the fluorescent signals of the microbes from the SMSS with the fluorescent signals from nonspecific hybridizations with negative controls. At a formamide concentration of 20%, the longer rod-shaped cells (Fig. 2D1, D2, D3, and D4) and filamentous cells (Fig. 2E1 and E2) did not hybridize with this probe. C. ferruginea and T. commune, which had only two and four mismatches, respectively, with the S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 probe, did not cross-react under the conditions used (20% formamide). C. ferruginea and T. commune hybridized with S-D-Bact-0338-a-A-18. Of the cells retrieved from the SMSS from the Nakabusa spring in June 2002, 82% ± 13% (n = 3) produced positive signals with the S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 probe (a positive signal indicated a total positive signal count for small rods with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenyindole [DAPI]; of 1,689 small rods positive with DAPI, 1,452 were positive with the S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 probe).

PCR-DGGE and RT-PCR-DGGE analyses.

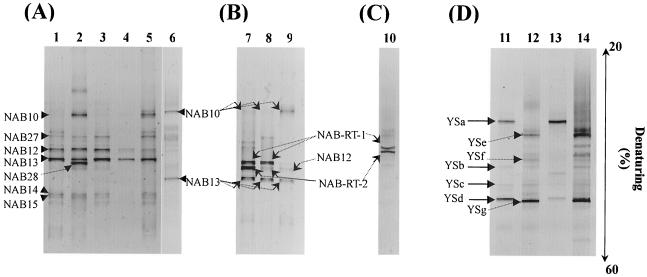

The DGGE profiles of 16S rDNA fragments amplified by PCR with a primer set for the domain Bacteria obtained from samples from the SMSS at Nakabusa had seven distinct bands, NAB10, NAB27, NAB12, NAB13, NAB28, NAB14, and NAB15 (Fig. 3A). Large differences were found among the profiles of the DGGE bands when the profiles obtained at low sulfide concentrations (less 0.1 mM) and the profiles obtained at higher sulfide concentrations (more than 0.1 mM) were compared. DGGE band NAB10 was observed when the concentration of sulfide in the hot spring water exceeded 0.1 mM. DGGE band NAB13 always occurred in profiles as the predominant band during the investigation. The RT-PCR-DGGE analysis of 16S rRNAs performed with the bacterial primer set revealed the presence of DGGE bands NAB-RT-1 and NAB-RT-2, which were not detected in the DNA-based PCR-DGGE profiles when the sulfide concentration was less than 0.1 mM (Fig. 3B). Previously identified archaeal DGGE bands NAB24 (Staphylothermus), NAB25 (an unidentified crenarchaeote), and NAB26 (Sulfophobococcus) (32) were detected in November 2000, September and November 2001, and June 2002. However, no archaeal PCR product was detected by RT-PCR amplification of any sample.

FIG. 3.

Comparison, by using PCR amplification and RT-PCR amplification, of DGGE profiles obtained from SMSS from the Nakabusa (A to C) and Yumata (D) hot springs during the present investigation. (A) Changes in 16S rDNA-based DGGE profiles obtained by PCR amplification; the primer set for the domain Bacteria was used. Lane 1, July 2000; lane 2, November 2000; lane 3, May 2001; lane 4, September 2001; lane 5, November 2001; lane 6, June 2002. (B) Changes in 16S rDNA-based DGGE profiles obtained by RT-PCR amplification; the primer set for the domain Bacteria was used. Lane 7, May 2001; lane 8, September, 2001; lane 9, June 2002. (C) DGGE profile obtained with primers Eub341F-GC and Arch915R by RT-PCR amplification. Lane 10, May 2001. (D) DGGE profiles obtained in August 2001 with a primer set for the domain Bacteria by PCR and RT-PCR amplification. Lanes 11 and 12, PCR; lanes 13 and 14, RT-PCR.

In order to specifically distinguish the 16S rDNA fragments from the filamentous cells hybridized with probes S-D-Bact-0338-a-A-18 and S-D-Arch-0915-a-A-20,RT-PCR-DGGE analysis with primers Eub341F-GC and Arch915R was carried out. Two dominant DGGE bands were obtained from the SMSS sample collected at the Nakabusa hot spring in May 2000 (Fig. 3C).

For the Yumata hot spring in August 2001 and August 2002, there were drastic differences in the profiles of the DGGE bands between site YS1 and site YS2, as determined by both PCR amplification and RT-PCR amplification (Fig. 3D). DGGE bands YSa and YSd obtained by PCR amplification were the dominant bands in the SMSS from site YS1, whereas bands YSe and YSg were subdominant DGGE bands only at site YS2. Similarly, bands YSe and YSg obtained by RT-PCR amplification were obtained only for site YS2. The fluorescence intensity of band YSd obtained by RT-PCR amplification was less than the fluorescence intensity of YSa. Archaeal band YSh was obtained for site YS1. However, no archaeal PCR product was detected by RT-PCR amplification of any sample.

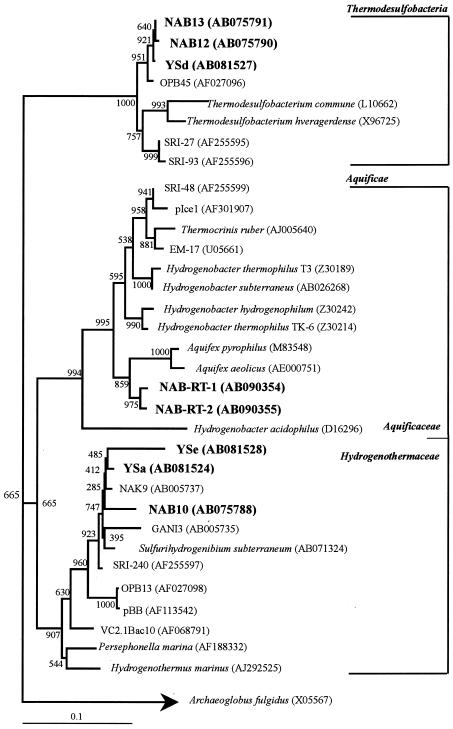

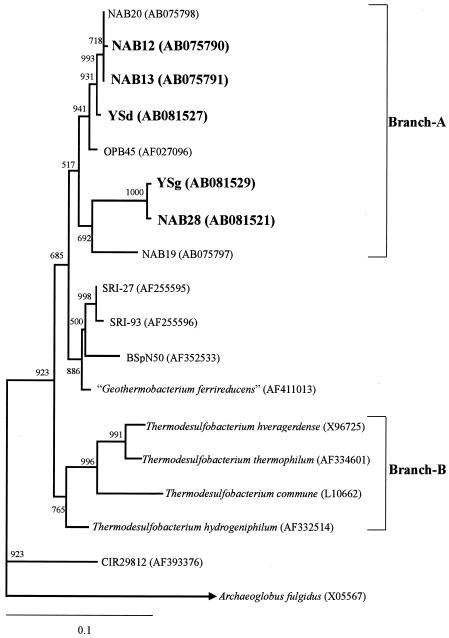

Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rDNAs.

The results of a phylogenetic analysis of DGGE bands NAB10 (Sulfurihydrogenibium-like), NAB12 (Thermodesulfobacteria-like), NAB14 (Thermus-like), and NAB15 (Thermus-like) from Nakabusa have been described previously (32). DGGE bands NAB10, YSa, and YSe amplified by RT-PCR (Fig. 3B and C) exhibited the highest sequence similarity to a strain of Sulfurihydrogenibium subterraneum (46) and clones GANI3, NAK9, and SRI-240 retrieved from sulfide-rich Japanese (55) and Icelandic (40) geothermal springs (Fig. 4). DGGE bands NAB-RT-1 and NAB-RT-2, which were phylogenetically related to microbes in the genus Aquifex, defined an independent cluster within the family Aquificaceae. DGGE band YSd was closely related to Thermodesulfobacteria-like clone NAB13 and clone OPB45 obtained from sediments in the Obsidian Pool (75 to 95°C) in Yellowstone National Park (23) (Fig. 5). Thermodesulfobacteria-like band YSg was closely related to clone NAB28 belonging to the Thermodesulfobacteria retrieved from the Nakabusa hot spring. DGGE bands NAB27 and YSb were closely related to a strain of Dictyoglomus thermophilum (98% similarity) (17). DGGE bands YSc and YSf were closely related to a strain of Fervidobacterium icelandicum (97% similarity) and to Fervidobacterium nodosum (96% similarity), a thermophilic bacterium in the Thermotogales (21), respectively. Archaeal band YSh obtained from the SMSS at site YS1 at Yumata was closely related to uncultured archaeon clone NAB24 (Staphylothermus) retrieved from the Nakabusa hot spring (32).

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic tree for DGGE bands NAB10, NAB12, NAB13, NAB-RT-1, NAB-RT-2, YSa, YSd, and YSe and for members of the Aquificae and Thermodesulfobacteria, based on partial 16S rRNA gene sequences (approximately 470 bp). The scale bar represents an estimated sequence divergence of 10%. The numbers at the nodes are bootstrap values determined from 1,000 iterations. The numbers in parentheses are accession numbers.

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic tree for DGGE bands (approximately 470 bp) belonging to members of the Thermodesulfobacteria from the Nakabusa and Yumata hot springs and for various Thermodesulfobacteria species, based on partial 16S rRNA gene sequences. The scale bar represents an estimated sequence divergence of 10%. The numbers at the nodes are bootstrap values determined from 1,000 iterations. The numbers in parentheses are accession numbers.

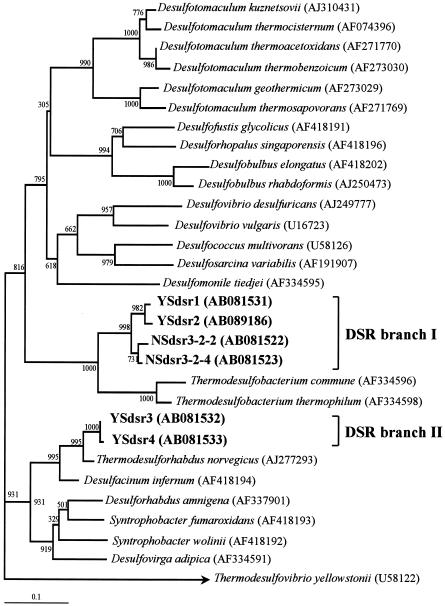

Clone library characterization and phylogenetic analysis of DSR genes.

DSR-encoding gene fragments (ca. 1.9 kb) were detected in the microbial streamers and mats of the Nakabusa and Yumata hot springs during this investigation. Two DSR clone families, NSdsr3-2-2 and NSdsr3-2-4, based on MspI restriction fragment band patterns, were obtained from the SMSS from the Nakabusa hot spring in July 2000 and September and November 2001 (Table 3). The frequencies of NSdsr3-2-2 were higher than those of NSdsr3-2-4 during the investigation. Clone families YSdsr1, YSdsr2, YSdsr3, and YSdsr4, based on AluI and MspI restriction fragment band patterns, were obtained from the SMSS from the Yumata hot spring in August 2001. The frequencies of YSdsr1 and YSdsr2 were higher than those of YSdsr3 and YSdsr4.

TABLE 3.

Clone families in the library of DSR gene fragments retrieved from the gray SMSS and the WSM in the Nakabusa and Yumata hot springs

| Clone familya | DSR branchb | No. of clones (% of clones)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site NS

|

SMSS at site YS1

|

WSM at site YS2

|

||||

| July 2000 | September 2001 | November 2001 | (August 2001) | (August 2001) | ||

| MspI | ||||||

| NSdsr3-2-2 | I | 19 (90) | 22 (88) | 12 (75) | NDc | ND |

| NSdsr3-2-4 | I | 3 (10) | 3 (12) | 4 (15) | ND | ND |

| AluI | ||||||

| YSdsr1 | I | ND | ND | ND | 28 (90) | 21 (60) |

| YSdsr2 | I | ND | ND | ND | 3 (10) | 1 (3) |

| YSdsr3 | II | ND | ND | ND | 0 (0) | 13 (37) |

| MspI | ||||||

| YSdsr1 | I | ND | ND | ND | 35 (100) | 24 (71) |

| YSdsr3 | II | ND | ND | ND | 0 (0) | 9 (26) |

| YSdsr4 | II | ND | ND | ND | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

Clone families based on AluI and MspI restriction fragment banding patterns.

DSR branches I and II are shown in Fig. 6.

ND, not determined.

Clone families NSdsr3-2-2, NSdsr3-2-4, YSdsr1, and YSdsr2 formed a branch (DSR branch I) that was distinct from the T. commune-Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum branch (Fig. 6). On the other hand, DSR clones YSdsr3 and YSdsr4, which made up independent DSR branch II, were closely related to Thermodesulforhabdus norvegicus, a thermophilic, gram-negative, sulfate-reducing bacterium belonging to the δ subclass of the Proteobacteria isolated from a North Sea oil field (6), with levels of similarity of 94 and 93%, respectively. The clone library for the SMSS at site YS1 was totally dominated by DSR branch I, which accounted for 100% of the clones. On the other hand, the proportion of DSR branch II was higher at site YS2.

FIG. 6.

Phylogenetic relationships of DSR α-subunit fragments (approximately 230 deduced amino acid sequences) as determined by neighbor-joining analysis. The scale bar represents an estimated sequence divergence of 10%. The numbers at the nodes are bootstrap values determined from 1,000 iterations. The numbers in parentheses are accession numbers.

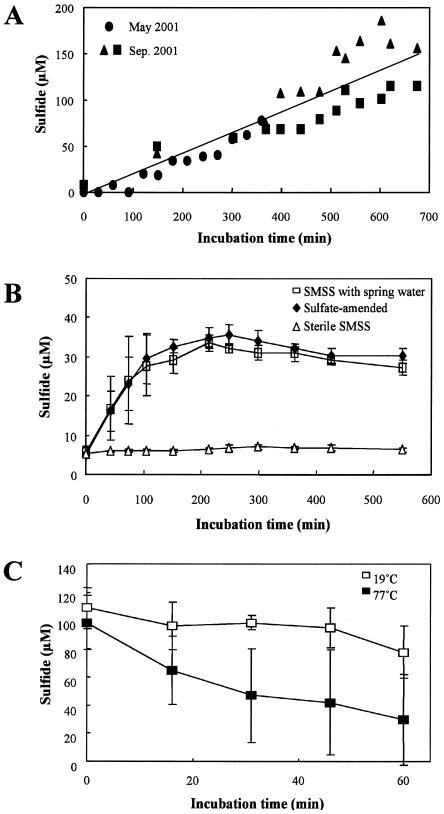

Sulfide production and consumption by the SMSS at Nakabusa.

The biological sulfide production by the SMSS at Nakabusa was examined in the laboratory (Fig. 7A and B). The concentrations of ambient sulfide in the SMSS samples collected in May and September 2001, when the in situ sulfide concentration of the spring water was lower, increased linearly (R2 = 0.830; P < 0.001) during incubation (Fig. 7A). The concentrations of ambient sulfide in both sulfate-amended and nonamended SMSS samples collected in November 2001, when the in situ sulfide concentration of spring water was higher, increased linearly (for sulfate-amended samples, R2 = 0.812 and P < 0.005; for nonamended samples, R2 = 0.607 and P < 0.005) during approximately the first 100 min of incubation, after which the production rates decreased (Fig. 7B). No sulfide was produced in the autoclaved control. There was no change in the frequency of predominant DGGE bands obtained by PCR amplification before or after the sulfide production experiments.

FIG. 7.

Sulfide production tests for SMSS in the Nakabusa hot spring. (A) Sulfide production by the SMSS collected in July and September 2001, when the in situ dissolved sulfide concentration in the spring water was low. Fifty-milliliter sterile serum bottles sealed with butyl rubber stoppers and containing 1 g of the SMSS and 30 ml of sulfate-amended spring water (5 mM) under a headspace of N2 gas were incubated at the in situ temperatures under anoxic conditions. (B) Sulfide production by 1 g of the SMSS collected in November 2001, when the in situ dissolved sulfide concentration in the spring water was high (n = 3). (C) In situ sulfide consumption by the SMSS in June 2002. Sterile serum bottles (150 ml) that were sealed with butyl rubber stoppers and contained 5 g of SMSS and 120 ml of spring water under a headspace of N2 gas were incubated in situ under anoxic conditions (n = 3).

In situ sulfide monitoring at the site revealed the consumption of sulfide by the SMSS from the Nakabusa hot spring collected in June 2002, when the in situ sulfide concentration of the spring water was higher (Fig. 7C). The sulfide concentration at 77°C was significantly (n = 3; R2 = 0.444; P < 0.01) lower than that at 19°C. However, the sulfide consumption at 77°C was inconsistent for replicates; in of bottles one-half of the sulfide was consumed in 16 min, while in the other bottle 39% of the sulfide was consumed after 60 min.

SRR of the SMSS.

The SRR for the SMSS samples collected from the Nakabusa hot spring in June 2002 was 40.31 ± 36.38 nmol g (wet weight) of SMSS−1 h−1 (n = 3), while that for the molybdate-amended control was 0.03 ± 0.00 nmol g (wet weight) of SMSS−1 h−1 (n = 3). No 35S2− was formed in the autoclaved controls. The SRR for the SMSS samples collected from the Yumata hot spring in August 2002 was 0.38 ± 0.04 nmol g (wet weight) of SMSS−1 h−1 (n = 3), while that for the molybdate-amended control was 0.02 ± 0.01 nmol g (wet weight) of SMSS−1 h−1 (n = 3). No 35S2− was formed in the autoclaved controls. These results demonstrate that there was in situ biological sulfide production by dissimilatory sulfate reduction by the SMSS at the in situ temperatures.

DISCUSSION

RT-PCR-DGGE and FISH.

The RT-PCR-DGGE analysis detected DGGE bands NAB-RT-1 and NAB-RT-2 from the SMSS (consortium I), which consisted of filamentous cells that hybridized with the fluorescently labeled probe S-O-Hydr-0540-a-A-19 (Fig. 2C2). Bands NAB-RT-1 and NAB-RT-2 had sequence regions corresponding to the sequence of probe S-O-Hydr-0540-a-A-19 (Table 1). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 3C, two DGGE bands corresponding to NAB-RT-1 and NAB-RT-2 were also amplified with primers Eub341F-GC and Arch915R by RT-PCR amplification. It has been shown previously that probe S-D-Arch-0915-a-A-18 yields a positive signal with some strains of Aquifex pyrophilus, with some strains of H. hydrogenophilum, and with some strains of H. hydrogenophilum affiliated with the earliest known branch on the bacterial phylogenetic tree (7, 18). Therefore, the parallel analysis with RT-PCR-DGGE and FISH demonstrated that clones NAB-RT-1 and NAB-RT-2 have phylotypes identical to those of filamentous cells that were dominant in the SMSS (consortium I) in sulfide-poor spring water. Similarly, RT-PCR-DGGE and FISH analysis with the rhodamine-labeled oligonucleotide probe S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 indicated that the shorter rod-shaped cells that were dominant in the SMSS in the Nakabusa and Yumata hot springs were microbes corresponding to DGGE bands NAB13 and YSd of the Thermodesulfobacteria. Although we were not able to develop any probe specific for 16S rRNAs of Sulfurihydrogenibium-like band NAB10, the longer rod-shaped cells that occurred in the SMSS (consortium II) (Fig. 2B, panel D1) were found to correspond to band NAB10 in the DGGE profiles in Fig. 3A and B. In fact, the numerous sausage-shaped bacterial cells inhabiting the sulfur turf hot springs in Japan and the United States were identified as Sulfurihydrogenibium-like phylotypes by a FISH assay in which the 16S rRNA-targeted specific oligodeoxynucleotide probe was used (37, 55).

Sulfide concentration and temperature are key factors in determining bacterial community composition.

Changes in the bacterial community structure in the SMSS in the Nakabusa hot spring, especially changes in the frequency of DGGE bands (NAB10, NAB-RT-1, and NAB-RT-2) affiliated with the Aquificae, were clearly related to changes in the concentration of dissolved sulfide in the hot spring water (Fig. 2A and B). Two Aquifex-like phylotypes, NAB-RT-1 and NAB-RT-2, were dominant when the sulfide concentration was less than 0.1 mM. In contrast, the Sulfurihydrogenibium-like phylotype NAB10 was dominant when the sulfide concentration was more than 0.1 mM. Indeed, a high frequency of the sulfur turf clones GANI3 and NAK9 has been observed at other sulfide-rich hot springs (40). Moreover, the sulfide production experiments revealed that the sulfide consumption by the SMSS (consortium II) was due predominantly to Sulfurihydrogenibium-like microbes (Fig. 7B and C). It is therefore likely that Sulfurihydrogenibium-like phylotype NAB10 in the SMSS (consortium II) utilizes in situ dissolved sulfide in hot spring water.

High levels of the filamentous bacteria EM17 (38) and pICE (44), which are closely related to a strain of Thermocrinis ruber, a pink-filament-forming hyperthermophilic hydrogen-utilizing bacterium (22), were found in sulfide-poor, hyperthermophilic geothermal springs in Iceland and Yellowstone National Park (sulfide concentrations, ca. 0.003 to 0.026 mM; temperatures, 79 to 88°C). Similarly, the filamentous bacteria NAB-RT-1 and NAB-RT-2, related to strains of Aquifex and Thermocrinis, were observed to be dominant in the SMSS (consortium I). However, it is difficult to speculate about the function (hydrogen utilization) of the filamentous NAB-RT-1 and NAB-RT-2 bacteria without more detailed physiological data. Indeed, a strain of Hydrogenobacter subterraneus is unable to grow on hydrogen gas (47).

PCR-DGGE and RT-PCR-DGGE analyses of 16S rDNA fragments revealed that as-yet-uncultivated Thermodesulfobacteria-like microbes were consistently dominant organisms during our 2-year investigation. The in situ temperature of the spring water at the sampling sites was constant (72 to 80°C) (Table 2). The optimum temperatures for the two strains of T. commune and T. hveragerdense isolated from terrestrial hot springs are 70°C (56) and 70 to 74°C (41), respectively. In addition, no clone belonging to the Thermodesulfobacteria was detected in the pink filaments occurring in an Icelandic hot spring at 88°C in spite of a neutral sulfide concentration (0.053 mM) (20) which was similar to that in the hot spring at Nakabusa. It is therefore likely that stability of the in situ temperature (72 to 80°C) of the spring water at sampling sites is a critical environmental factor in determining the stable dominance of Thermodesulfobacteria in hydrothermal habitats.

Comparisons between 16S rRNA and dsrA genes based on phylogenetic relationships.

The phylogenetic comparison of retrieved 16S rRNA and dsrA sequences indicated the congruent phylogeny of 16S rDNA branch A shown in Fig. 5, which included the Thermodesulfobacteria-like sequences YSd, NAB12, and NAB13, and DSR branch I shown in Fig. 6, which included dsrA sequences NSdsr3-2-2, NSdsr3-2-4, YSdsr1, and YSdsr2. However, a phylogenetic analysis of dsrA sequences YSdsr3 and YSdsr4 revealed a phylogenetic inconsistency between these dsrA sequences and the YSg 16S rDNA sequences. It seems that a phenotype corresponding to DSR clones in DSR branch II was not detected as DGGE bands based on 16S rDNA due to the small numbers in all microbial populations.

Sulfide production by the Thermodesulfobacteria.

The present study showed that there was a linear increase in the sulfide concentration of spring water in a bottle with the uncultivated Thermodesulfobacteria-dominated SMSS (consortium I) which occurred in spring water containing low levels of sulfide in May and September 2001 (Fig. 7A). The 35SO42− tracer experiment provided evidence that there was reduction of sulfate to sulfide through anaerobic sulfate respiration by microbes dominant in the SMSS at Nakabusa and Yumata. The SRR was much higher than that of the molybdate-amended control, since the molybdate greatly inhibited the SRR. In addition, RT-PCR-DGGE analysis combined with the FISH assay with probe S-*-Tdes-0830-a-A-20 indicated that as-yet-uncultivated microbes in the Thermodesulfobacteria were dominant in the SMSS (Fig. 2D and E). Moreover, phylogenetic analysis revealed the dominance of DSR sequences NSdsr3-2-2, NSdsr3-2-4, YSdsr1, and YSdsr2, which form a branch separate from the known Thermodesulfobacterium lineage (Fig. 6). Therefore, these results demonstrated that as-yet-uncultivated microbes belonging to the Thermodesulfobacteria, which were dominant in the SMSS, constituted a numerically important population and played a critical role in the biological sulfide production in the SMSS in the hot springs at Nakabusa and Yumata. Thermophilic SRB, whose 16S rDNA genes are closely related to 16S rDNA genes of strains of T. commune and T. hveragerdense, formed an individual branch (branch B), as shown in Fig. 5, and were enriched from the SMSS from the Nakabusa hot spring. The DSR gene fragments of the thermophilic SRB, which are closely related to those of a strain of T. commune, were detected in the enrichment cultures (data not shown). However, the contribution of this organism to in situ sulfide production in the SMSS was probably less than that of the as-yet-uncultivated Thermodesulfobacteria that were dominant there, since no 16S rRNA or DSR gene closely related to the 16S rRNA or DSR gene of the T. commune strain was found in the in situ samples.

Although the function of microbes corresponding to the archaeal DGGE bands in geothermal hot springs is unknown, the archaeal community seems to play a minor role in sulfide production in the SMSS based on the lack of detection of archaeal RT-PCR amplification with a primer set for the domain Archaea. Similarly, it has been reported that based on a FISH assay performed with the 16S rRNA-targeted specific oligodeoxynucleotide probe, archaeal members are in the minority in black filamentous communities dominated by phylotype pBB in the Aquificae associated with hot springs at Calcite Springs in Yellowstone National Park (38).

Sulfur cycling.

The biological sulfide oxidization and sulfide production through sulfate reduction by the SMSS (consortium II) suggest that there is a sulfur cycle between the dominant Sulfurihydrogenibium- and Thermodesulfobacteria-like bacteria in the Nakabusa and Yumata hot springs. Sulfurihydrogenibium strain HGM-K1 utilizes thiosulfate as an electron donor and is able to oxidize it to sulfate under microaerophilic conditions (45). Several strains belonging to the Aquificae isolated from deep-sea hydrothermal vents and subsurface waters have the ability to utilize of nitrate as an electron acceptor (36, 45, 50). Since nitrate was not detected in the spring water at Nakabusa during the present investigation, it is likely that the Sulfurihydrogenibium-like microbes in the SMSS (consortium II) utilize oxygen under microaerophilic conditions.

Conclusion.

Molecular analyses based on 16S rRNA and DSR genes coupled with the physiological data (sulfide monitoring and SRR) provided a more comprehensive understanding of the microbial sulfur metabolism of as-yet-uncultivated Thermodesulfobacteria- and Sulfurihydrogenibium-like microbes in the SMSS at the Nakabusa and Yumata hot springs.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Kenji Kato and Hiroyuki Yamamoto for their advice and to Yoshikazu Koizumi and Hisaya Kojima for their support in our field survey and their comments on this study.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to M.F. (grant 12440219) and T.N. (grant 09359) and in part by MEXT through the Special Coordination Fund of the Archaean Park International Research Project on Interaction between Sub-Vent Biosphere and Geo-Environments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alm, E. W., D. B. Oerther, N. Larsen, D. A. Stahl, and L. Raskin. 1996. The oligonucleotide probe database. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3557-3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäfer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann, R. I. 1995. In situ identification of micro-organisms by whole cell hybridization with rRNA-targeted nucleic acid probes, p. 1-15. In A. D. L. Akkerman, J. D. van Elsas, and F. J. de Bruijn (ed.), Molecular microbial ecology manual. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 4.Amann, R. I., I. Krumholz, and D. A. Stahl. 1990. Fluorescent-oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic, and environmental studies in microbiology. J. Bacteriol. 172:762-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker, B. J., D. P. Moser, B. J. MacGregor, S. Fishbain, M. Wagner, N. K. Fry, B. Jackson, N. Speolstra, S. Loos, K. Takai, B. S. Lollar, J. Fredrickson, D. Balkwill, T. C. Onstott, C. F. Wimpee, and D. A. Stahl. 2003. Related assemblages of sulphate-reducing bacteria associated with ultradeep gold mines of South Africa and deep basalt aquifers of Washington State. Environ. Microbiol. 5:267-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beeder, J., T. Torsvik, and T. Lien. 1995. Thermodesulforhabdus norvegicus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel thermophilic sulfate-reducing bacterium from oil field water. Arch. Microbiol. 164:331-336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burggraf, S., T. Mayer, R. Amann, S. Schadhauser, C. R. Woese, and K. O. Stetter. 1994. Identifying members of the domain Archaea with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3112-3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casamayor, E. O., H. Schäfer, L. Bañeras, C. Pedrós-Alió, and G. Muyzer. 2000. Identification of and spatio-temporal difference between microbial assemblages from two neighboring sulfur lakes: comparison by microscopy and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:499-508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang, Y.-J., A. D. Peacock, P. E. Long, J. R. Stephen, J. P. McKinley, S. J. Macnaughton, A. K. M. Anwar Hussain, A. M. Saxton, and D. C. White. 2001. Diversity and characterization of sulfate-reducing bacteria in groundwater at a uranium mill tailings site. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3149-3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cline, J. D. 1969. Spectrophotometric determination of hydrogen sulfide in natural waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 14:454-458. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cottrell, M. T., and S. C. Cary. 1999. Diversity of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes of bacteria associated with the deep-sea hydrothermal vent polychaete annelid Alvinella pompejana. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1127-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhillon, A., A. Teske, J. Dillon, D. A. Stahl, and M. L. Sogin. 2003. Molecular characterization of sulfate-reducing bacteria in the Guaymas Basin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2765-2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubilier, N., C. Mülders, T. Ferdelman, D. de Beer, A. Pernthaler, M. Klein, M. Wagner, C. Erseus, F. Thiermann, J. Krieger, O. Giere, and R. Amann. 2001. Endosymbiotic sulphate-reducing and sulphide-oxidizing bacteria in an oligochaete worm. Nature 411:298-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishbain, S., J. G. Dillon, H. L. Gough, and D. A. Stahl. 2003. Linkage of high rates of sulfate reduction in Yellowstone hot springs to unique sequence types in the dissimilatory sulfate respiration pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3663-3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fossing, H., and B. B. Jøorgensen. 1989. Measurement of bacterial sulfate reduction in sediments: evaluation of a single-step chromium reduction method. Biogeochemistry 8:205-222. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukui, M., Y. Suwa, and Y. Urushigawa. 1996. High survival efficiency and ribosomal RNA decaying pattern of Desulfobacter latus, a highly specific acetate-utilizing organism, during starvation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 19:17-25. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbs, M. D., R. A. Reeves, and P. L. Bergquist. 1995. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of a xylanase gene from the extreme thermophile Dictyoglomus thermophilum Rt46B.1 and activity of the enzyme on fiber-bound substrate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:4403-4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harmsen, H. J. M., D. Prieur, and C. Jeanthon. 1997. Group-specific 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes to identify thermophilic bacteria in marine hydrothermal vents. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4061-4068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiraishi, A., T. Umezawa, H. Yamamoto, K. Kato, and Y. Maki. 1999. Changes in quinone profiles of hot spring microbial mats with a thermal gradient. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:198-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hjorleifsdottir, S., S. Skirnisdottir, G. O. Hreggvidsson, and J. K. Kristjansson. 2001. Species composition of cultivated and noncultivated bacteria from short filaments in an Icelandic hot spring at 88°C. Microb. Ecol. 42:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huber, R., C. R. Woese, T. A. Langworthy, J. K. Kristjansson, and K. O. Stetter. 1990. Fervidobacterium islandicum sp. nov., a new extremely thermophilic eubacterium belonging to the Thermotogales. Arch. Microbiol. 154:105-111. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber, R., W. Eder, S. Heldwein, G. Wanner, H. Huber, R. Rachel, and K. O. Stetter. 1998. Thermocrinis ruber gen. nov., sp. nov., a pink-filament-forming hyperthermophilic bacterium isolated from Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3576-3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hugenholtz, P., C. Pitulle, K. L. Hershberger, and N. R. Pace. 1998. Novel division level bacterial diversity in a Yellowstone hot spring. J. Bacteriol. 180:366-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joulian, C., N. B. Ramsing, and K. Ingvorsen. 2001. Congruent phylogenies of most common small-subunit rRNA and dissimilatory sulfite reductase gene sequences retrieved from estuarine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3314-3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawasumi, T., Y. Igarashi, T. Kodama, and Y. Minoda. 1984. Hydrogenobacter thermophilus gen. nov., sp. nov., an extreme thermophilic, aerobic, hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 34:5-10. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kryukov, V. R., N. D. Savelyeva, and M. A. Pusheva. 1983. Calderobacterium hydrogenophilum gen. nov., sp. nov., an extreme thermophilic bacterium, and its hydrogenase activity. Mikrobiologiya 52:781-788. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipman, D. J., and W. R. Pearson. 1985. Rapid and sensitive protein similarity searches. Science 227:1435-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maki, Y. 1991. Study of the “sulfur-turf”: a community of colorless sulfur bacteria growing in hot spring effluent. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Microb. Ecol. 8:175-179. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marteinsson, V. T., S. Hauksdóttir, C. F. V. Hobel, H. Kristmannsdóttir, G. O. Hreggvidsson, and J. K. Kristjánsson. 2001. Phylogenetic diversity analysis of subterranean hot springs in Iceland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4242-4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minz, D., J. L. Flax, S. J. Green, G. Muyzer, Y. Cohen, M. Wagner, B. E. Rittmann, and D. A. Stahl. 1999. Diversity of sulfate-reducing bacteria in oxic and anoxic regions of a microbial mat characterized by comparative analysis of dissimilatory sulfite reductase genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4666-4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muyzer, G., A. Teske, C. O. Wirsen, and H. W. Jannasch. 1995. Phylogenetic relationships of Thiomicrospira species and their identification in deep-sea hydrothermal vent samples by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of 16S rDNA fragments. Arch. Microbiol. 164:165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagawa, T., and M. Fukui. 2002. Phylogenetic microbial compositions of mats and streamers from a Japanese alkaline hot spring with a thermal gradient. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 48:211-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakagawa, T., S. Hanada, A. Maruyama, K. Marumo, T. Urabe, and M. Fukui. 2002. Distribution and diversity of thermophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria within a Cu-Pb-Zn mine (Toyoha, Japan). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 41:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page, R. D. M. 1996. TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Applic. Biosci. 12:357-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raskin, L., J. M. Stromley, B. E. Rittmann, and D. A. Stahl. 1994. Group-specific 16S rRNA hybridization probes to describe natural communities of methanogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1232-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reysenbach, A.-L., A. B. Banta, D. R. Boone, S. C. Cary, and G. W. Luther. 2000. Microbial essentials at hydrothermal vents. Nature 404:835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reysenbach, A.-L., M. Ehringer, and K. Hershberger. 2000. Microbial diversity at 83°C in Calcite Springs, Yellowstone National Park: an environment where the Aquificales and “Korarchaeota” coexist. Extremophiles 4:61-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reysenbach A.-L., G. S. Wickham, and N. R. Pace. 1994. Phylogenetic analysis of the hyperthermophilic pink filament community in Octopus Spring, Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2113-2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saito, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for constructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skirnisdottir, S., G. O. Hreggvidsson, S. Hjörleifsdottir, V. T. Marteinsson, S. K. Retursdottir, O. Holst, and J. K. Kristjansson. 2000. Influence of sulfide and temperature on species composition and community structure of hot spring microbial mats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2835-2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sonne-Hansen, J., and B. K. Ahring. 1999. Thermodesulfobacterium hveragerdense sp. nov. and Thermodesulfovibrio islandicus sp. nov., two thermophilic sulfate reducing bacteria isolated from a Icelandic hot spring. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22:559-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stahl, D. A., and R. I. Amann. 1991. Development and application of nucleic acids probes, p. 205-248. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Wiley, New York, N.Y.

- 43.Stahl, D. A., B. Flesher, H. Mansfield, and L. Montgomery. 1988. Use of phylogenetically based hybridization probes for studies of ruminal microbial ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1079-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takacsa, C. D., M. Ehringerb, R. Favrec, M. Cermolac, G. Eggertssond, A. Palsdottire, and A. L. Reysenbach. 2001. Phylogenetic characterization of the blue filamentous bacterial community from an Icelandic geothermal spring. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 35:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takai, K., H. Hirayama, Y. Sakihama, F. Inagaki, Y. Yamato, and K. Horikoshi. 2002. Isolation and metabolic characteristics of previously uncultured member of the order Aquificales in a subsurface gold mine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3046-3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takai, K., H. Kobayashi, K. H. Nealson, and K. Horikoshi. 2003. Sulfurihydrogenibium subterraneum gen. nov., sp. nov., from a subsurface hot aquifer. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:823-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takai, K., T. Komatsu, and K. Horikoshi. 2001. Hydrogenobacter subterraneus sp. nov., an extremely thermophilic, heterotrophic bacterium unable to grow on hydrogen gas, from deep subsurface geothermal water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1425-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomsen, T. R., K. Finster, and N. B. Ramsing. 2001. Biogeochemical and molecular signatures of anaerobic methane oxidation in a marine sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1646-1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Dover, C. L., S. E. Humphris, D. Fornari, C. M. Cavanaugh, R. Collier, S. K. Goffredi, J. Hashimoto, M. D. Lilley, A. L. Reysenbach, T. M. Shank, K. L. Von Damm, A. Banta, R. M. Gallant, D. Götz, D. Green, J. Hall, T. L. Harmer, L. A. Hurtado, P. Johnson, Z. P. McKiness, C. Meredith, E., Olson, I. L. Pan, M. Turnipseed, Y. Won, C. R. Young III, and R. C. Vrijenhoek. 2001. Biogeography and ecological setting of Indian Ocean hydrothermal vents. Science 294:818-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wagner, M., A. Roger, J. Flax, G. Brusseau, and D. A. Stahl. 1998. Phylogeny of dissimilatory sulfite reductases supports an early origin of sulfate respiration. J. Bacteriol. 180:2975-2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ward, D. M., R. Weller, and M. M. Bateson. 1990. 16S rRNA sequences reveal numerous uncultured microorganisms in a natural community. Nature 345:63-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Widdel, F. 1988. Microbiology and ecology of sulfate- and sulfur-reducing bacteria, p. 469-585. In A. J. B. Zehnder (ed.), Biology of anaerobic microorganisms. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 54.Wilson, K. 1990. Miniprep of bacterial genomic DNA, p. 2.4.1-2.4.2. In F. M. Ausubel et al. (ed.), Short protocols in molecular biology, 2nd ed. Wiley, New York, N.Y.

- 55.Yamamoto, H., A. Hiraishi, K. Kato, H. X. Chiura, Y. Maki, and A. Shimizu. 1998. Phylogenetic evidence for the existence of novel thermophilic bacteria in hot spring sulfur-turf microbial mats in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1680-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeikus, J. G., M. A. Dawson, T. E. Thompson, K. Ingvorsen, and E. C. Hatchikian. 1983. Microbial ecology of volcanic sulphidogenesis: isolation and characterization of Thermodesulfobacteruim commune gen. nov. and sp. nov. J. Gen. Microbiol. 129:1159-1169. [Google Scholar]