Abstract

When disasters strike resource-poor nations, women are often the most affected. They represent the majority of the poor, the most malnourished, and the least educated, and they account for more than 75% of displaced persons. The predisaster familial duties of women are magnified and expanded, and they have significantly less support and fewer resources than they had before the incident. Moreover, after the disaster, they bear the responsibility of caring for their children, the elderly, the injured, and the sick. Besides the effects of the disaster, women become more vulnerable to reproductive and sexual health problems and are at increased risk for physical and sexual violence. Women become both victims and the primary caretakers. Health practitioners are often not aware of these issues when providing emergency care. Developing a disaster relief team with experts in maternal health is necessary to improve women’s health outcome.

Key words: Maternal mortality, Infant mortality, Sexual violence, Disaster relief

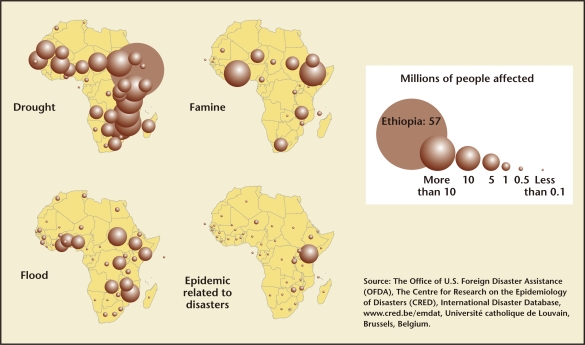

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a disaster as “any occurrence that causes damage, ecological disruption, loss of human life or deterioration of health and health services on a scale sufficient to warrant an extraordinary response from outside the affected community area.”1 Between 1990 and 1999, more than 2 billion people were affected by natural or technological disasters; these disasters led to 600,000 deaths.2 There are a variety of disasters that include drought, famine, floods, hurricanes, tsunamis, and epidemic-related disasters (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

People affected by natural disasters (1971–2001). Adapted from UNEP/GRID-Arendal. People Affected by Natural Disasters During the Period 1971 to 2001. UNEP/GRID-Arendal Maps and Graphics Library. 2002. http://maps.grida.no/go/graphic/people_affected_by_natural_disasters_during_the_period_1971_to_2001. Accessed February 25, 2011.

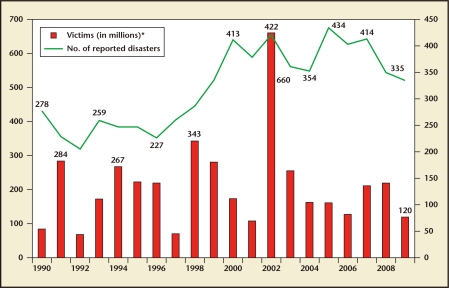

The average number of natural disasters between 2000 and 2008 was 392 (Figure 2). In 2009, there were 350 natural disasters and in 2010 there were 373. The location of a catastrophic event is directly related to the number of people affected. Disasters that have had the highest impact are the drought in India in 2002 (300 million victims), the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004 (226,408 deaths), cyclone Nargis in Myanmar in 2008 (138,366 deaths), and the Haitian earthquake in 2010 (296,800 deaths).3 Although Hurricane Katrina was the third deadliest hurricane in the United States, killing approximately 1500 people (and costing $81 billion), the availability of US resources minimized further human deaths.4

Figure 2.

Average number of disasters from 1990 to 2009. *Victims: Sum of killed and total affected. Source: EMDAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database; www.emdat.be; Université catholque de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium.

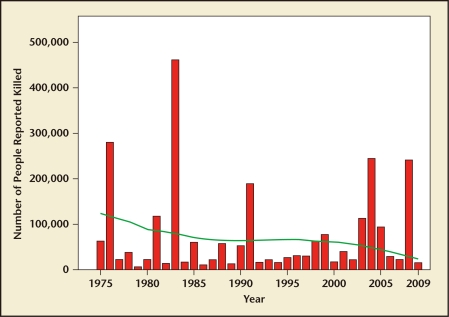

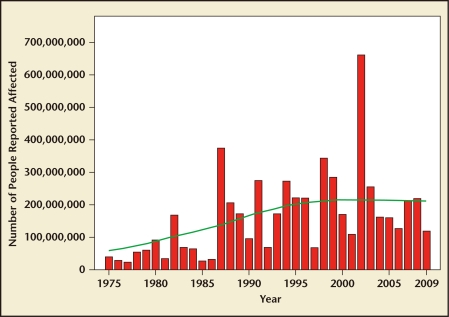

In natural disasters, the hardest-hit regions are clearly in resource-poor nations where health care, transportation, and infrastructure are already compromised. During the Haitian earthquake in 2010, the health care infrastructure was crippled. Physicians likened their experience to practicing medicine in the 1930s, when vodka was used to sterilize instruments and saws were used for limb amputations.5 Physicians struggled with the disparity between the supplies they needed to care for patients and the resources that were in fact available. Although the number of people killed by disasters is decreasing, the number of people affected is increasing (Figures 3 and 4). Although it is difficult to predict the trend of natural disasters, the fact remains that disasters will continue to occur.

Figure 3.

Number of people reported killed by natural disasters (1975–2009). Source: EMDAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database; www.emdat.be; Université catholque de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium.

Figure 4.

Number of people affected by natural disasters (1975–2009). Source: EMDAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database; www.emdat.be; Université catholque de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium.

Gender Differences in the Aftermath

Evidence shows that disasters do not affect men and women in the same way because of biologic, social, cultural, and reproductive health differences. In 1976, in the technological disaster of Seveso, Italy, the population was exposed to dioxin. Biologic differences between the sexes were seen: 15 years later, more men died of rectal and lung cancer, whereas more women died of diabetes. In the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, the ratio of deaths between women and men was 3:1 because men were stronger, women had not learned to swim, and women’s long hair got entangled in debris.6

Social determinants also affect men and women differently. For example, in the 1993 earthquake in Maharashtra, India, more women and children died than men because the women were in the homes, whereas the men were out in the fields. Conversely, social roles determined that men were more affected than women during the 1985 Chernobyl disaster. The soldiers and male civilians predominantly cleaned up the site and as a result were exposed to more radiation. Cultural norms have prevented women from seeking help after a disaster, especially in certain regions where interacting with men is strictly forbidden.2 Social norms have demonstrated that women bear more of the responsibility of caring for children, elderly, and the sick or injured.

However, reproductive factors clearly affect women. After disasters, studies have shown that women have more miscarriages, premature deliveries, cases of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), low birth weight infants, sexual violence, and undesired pregnancies.7

Effect of Disasters on Women

Violence Against Women

During displacement, women and girls are at an increased risk for domestic violence and sexual assault.8,9 They become more helpless and vulnerable, and as a result, the exploitation and abuse of women and girls- including domestic violence-increases. Women may be coerced or forced into sex for food, shelter, and even security. Girls are at an increased risk for trafficking and can be forced into early marriages.10 The sex industry thrives during these difficult times because of both supply and demand. The United Nations Refugee Agency has identified factors that contribute to sexual violence. Some of these factors include male dominance, psychologic stress in refugee camps, lack of protection and support for women, alcohol and drug abuse, and general lawlessness.7

The psychologic effect of sexual violence, manipulation, or both can further prevent women from reintegrating into the society long after the disaster is over. Health care providers during disasters are not always trained to address victims of sexual violence. When attention is primarily focused on life-saving or limb-saving techniques, sexual violence is rarely considered. Effective measures in caring for rape victims include eliciting a thorough sexual history, treating physical injuries, providing emergency contraception and prophylactic treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), reporting the perpetrator or perpetrators, and establishing safety and order in shelters and camps. Health workers who are experienced in helping victims of sexual violence can also help identify children who might be at risk (eg, orphans and children separated from their families). Women should also be referred to resources to ensure protection from further sexual assaults.11

Access to Contraceptive Care and Prevention of STIs

During emergencies, routine behaviors are altered drastically. Women who use contraception may not have access to contraceptive drugs or devices or may forget to take or use them. In addition, stress and despair create, at best, comfort-seeking behaviors when people crave closeness and intimacy and, at worst, violent sexual behaviors. Unprotected coitus thus places women at risk for pregnancy and STIs. Prevention of unplanned and undesired pregnancies must be at the forefront of emergency-response measures (Table 1). If available, injectable methods of contraception are optimal because they do not require women to remember to use contraception during times of crisis.

Table 1.

Access to Contraceptive Care

| Immediate Strategy |

| • Determine the availability of contraception |

| • Document the type and quantity of contraceptives and their expiration dates |

| • Distribute condoms to both men and women |

| • Offer emergency contraception |

| • Promote the use of injectable methods of contraception |

| Long-Term Strategy |

| • Establish ob-gyn health care services with trained staff in shelters or refugee camps |

| • Conduct information and education sessions on sexual health and reproductive rights in camps |

| • Ensure educational supplies on reproductive and sexual health |

Adapted from Recommendations for contraceptive care in emergencies. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization Web site. http://new.paho.org/disasters/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogcategory&id=817&Itemid=800&limit=9&limitstart=9. Accessed February 25, 2011.

During disasters, preventive measures against STIs and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and AIDS are forgotten or ignored. In addition, HIV-positive persons may not have access to their medication, and as a result they are at higher risk for transmitting the disease during this time period. Thus, preventing the transmission of STIs is a vital part of emergency response (Table 2).

Table 2.

STI Prevention Strategy

| • Confirm the availability and distribution of condoms |

| • Intensify the promotion of condom use |

| • Identify and distribute medications necessary to treat common STIs |

| • Identify medical units equipped to care for HIV-positive pregnant women |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Adapted from Recommendations for contraceptive care in emergencies. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization Web site. http://new.paho.org/disasters/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogcategory&id=817&Itemid=800&limit=9&limitstart=9. Accessed February 25, 2011.

Prenatal Care and Delivery in Emergencies

In resource-poor nations, prenatal care and delivery can be challenging given the poor facilities and the lack of necessary equipment for emergencies. Pregnancy complications such as placenta previa and placenta accreta, retained placenta, obstructed labor, and fetal distress are challenges in the best of times. During a natural disaster, health care facilities and providers are stretched even further (Table 3). Pregnancy complications and childbirth in unsafe conditions increase maternal and infant morbidity and mortality.

Table 3.

Prenatal Care and Delivery

| • Establish a census or registry for identifying pregnant and postpartum women |

| • Identify the patient’s last monthly period or estimated date of conception |

| • Identify high-risk pregnancies |

| • Identify or establish prenatal care centers |

| • Identify appropriate labor and delivery health care facilities that have the ability to perform cesarean deliveries and have available blood products and resources to perform neonatal resuscitation |

| • Inform pregnant women about the signs and symptoms of normal labor and instructions to follow during an emergency |

| • Administer tetanus toxoid to all pregnant patients |

| • Ensure the availability of clean water for pregnant and lactating women |

| • Encourage and support lactation |

Adapted from Recommendations for prenatal care and delivery care in emergencies. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization Web site. http://new.paho.org/disasters/index2.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=738&pop=1&page=0&Itemid=800. Accessed February 25, 2011.

The delivery of prenatal care decreases significantly after a disaster. Pregnant women initially are trying to survive the disaster by finding food, water, and shelter. Those women who are able to monitor their fetal movement may not think that they need to seek medical help until delivery. As a result, high-risk pregnancies involving preeclampsia, placenta previa, IUGR, or gestational diabetes may not be diagnosed, resulting in poor maternal and fetal outcomes. During one disaster, even in areas where prenatal care was available, the rate of inadequate prenatal care increased from 1.3% to 3.9%.7 Among women living within 2 miles of the World Trade Center, there was a higher rate of infants with IUGR, infants who were small for gestational age, and infants who had a small head circumference.12

Many disaster-relief physicians are experienced surgeons or emergency department doctors who have performed few or no cesarean deliveries. Their inexperience in reading fetal monitors can sometimes result in quick decisions to perform cesarean deliveries when they observe fetal heart-rate decelerations. Experienced midwives and obstetricians might be more likely to monitor the decelerations and increase the chances for a vaginal delivery. This approach would also avert a potential wound infection and sepsis in the mother.

During disasters, the importance of breastfeeding cannot be overemphasized. It is challenging to find access to clean water for sterilizing bottles or buying formula.13 Educating and supporting new mothers to establish and maintain breastfeeding is necessary. Data suggest that even nonlactating mothers who are less than 6 months pregnant can initiate or reinitiate lactation.7

Conclusions

During catastrophic disasters in resource-poor nations, the standard of care that practitioners are accustomed to is rarely available. Critical decisions are made swiftly, and patients are prioritized medically, with those who have the highest likelihood for survival being treated first. During these disasters, volunteers in emergency medicine, orthopedics, and pediatric and trauma surgery are the first to be called. Obstetricians and gynecologists are not usually considered. The response to disasters must take into account the needs of mothers and children during the acute or recovery phases of the crisis. Given their experience in obstetric emergencies, including postpartum hemorrhage, placenta accreta, and cesarean hysterectomies, and their ability to watch a nonreassuring fetal heart tracing and determine whether it indicates a danger to the fetus, perhaps more obstetricians and gynecologists should get involved in disaster-relief work. While surgeons are addressing crush injuries and infectious-disease control, obstetricians-gynecologists can address STIs and the care of victims of sexual assault. Overall, care for disaster victims must be comprehensive. Relief teams must have an expert in maternal and women’s health to improve women’s and families’ long-term health outcome.

Main Points.

When disasters strike resource-poor nations, women are often the most affected. They represent the majority of the poor, the most malnourished, and the least educated, and they account for more than 75% of displaced persons.

During displacement, women and girls are at an increased risk for domestic violence and sexual assault. The psychologic effect of sexual violence, manipulation, or both can further prevent women from reintegrating into the society long after the disaster is over.

Women who use contraception may not have access to contraceptive drugs or devices or may forget to take or use them. In addition, stress and despair create, at best, comfort-seeking behaviors when people crave closeness and intimacy, and, at worst, violent sexual behaviors.

In resource-poor nations, prenatal care and delivery can be challenging given the poor facilities and the lack of necessary equipment for emergencies. During a natural disaster, health care facilities and providers are stretched even further. Pregnancy complications and childbirth in unsafe conditions increase maternal and infant morbidity and mortality.

Given their experience in obstetric emergencies, including postpartum hemorrhage, placenta accreta, and cesarean hysterectomies, and their ability to watch a nonreassuring fetal heart tracing and determine whether it indicates a danger to the fetus, more obstetricians and gynecologists should get involved in disaster-relief work. While surgeons are addressing crush injuries and infectious-disease control, obstetricians and gynecologists can address sexually transmitted infections and the care of victims of sexual assault. Overall, care for disaster victims must be comprehensive.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO), authors Community Emergency Preparedness: A Manual for Managers and Policy Makers. Geneva: WHO; 1999. [Accessed February 25, 2011]. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/9241545194.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) Department of Gender and Women’s Health, authors. Gender and Health in Disasters. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [Accessed February 25, 2011]. http://www.who.int/gender/other_health/en/genderdisasters.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos F, Rodriguez J, Below R, Guha-Sapir D. Annual Disaster Statistical Review 2009: The Numbers and Trends. Brussels: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters; 2010. [Accessed February 25, 2011]. http://cred.be/sites/default/files/ADSR_2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The deadliest U.S. Hurricanes. Tropical Weather .net Web site, authors. [Accessed February 25, 2011]. http://www.tropicalweather.net/deadliest_U.S._hurricanes.htm.

- 5.Annas GJ. Standard of care-in sickness and in health and in emergencies. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2126–2131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhle1002260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carballo M, Hernandez M, Schneider K, Welle E. Impact of the tsunami on reproductive health. J R Soc Med. 2005;98:400–403. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.9.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, authors. Preparing for Disasters: Perspectives on Women. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2010. (Committee Opinion 457). [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), authors Prevention and Response to Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in Refugee Situations: Inter-Agency Lessons Learned Conference Proceedings (27–29 March 2001—Geneva) Geneva: UNHCR; 2001. [Accessed February 25, 2011]. http://action.web.ca/home/cpcc/attach/prevention%20and%20responses.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorton WE, Voigt L. Disaster rape: vulnerability of women to sexual assaults during Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Public Management & Social Policy. 2007;13:23–49. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sapir DG. Natural and man-made disasters: the vulnerability of women-headed households and children without families. World Health Stat Q. 1993;46:227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization (WHO) Department of Injuries and Violence Prevention, authors. Violence and Disasters. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [Accessed February 25, 2011]. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/violence_disasters.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lederman SA, Rauh V, Weiss L, et al. The effects of the World Trade Center event on birth outcomes among term deliveries at three lower Manhattan hospitals. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1772–1778. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Gasseer N, Dresden E, Keeney GB, Warren N. Status of women and infants in complex humanitarian emergencies. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49(4 suppl 1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]