Abstract

Background:

Group patient visits are medical appointments shared among patients with a common medical condition. This care delivery method has demonstrated benefits for individuals with chronic conditions but has not been evaluated for Parkinson disease (PD).

Methods:

We conducted a 12-month, randomized trial of group patient visits vs usual (one-on-one) care for patients with PD. Visits were led by one of 3 study physicians, included patients and caregivers, and lasted approximately 90 minutes. Those receiving group visits had 4 sessions over 12 months. The primary outcome measure was feasibility as measured by the ability to recruit participants and by the proportion of participants who completed the study. The primary efficacy outcome was quality of life as measured by the PD Questionnaire-39.

Results:

Thirty patients and 27 caregivers enrolled in the study. Thirteen of the 15 patients randomized to group patient visits and 14 of the 15 randomized to usual care completed the study. Quality of life measured 12 months after baseline between the 2 groups was not different (25.9 points for group patient visits vs 26.0 points for usual care; p = 0.99).

Conclusions:

Group patient visits may be a feasible means of providing care to individuals with PD and may offer an alternative or complementary method of care delivery for some patients and physicians.

Classification of evidence:

This study provides Class II evidence that group patient visits did not improve quality of life for individuals with PD over a 1-year period.

Group patient visits are medical appointments with one physician and a group of individuals with a common, usually chronic, medical condition. This model has been used in diabetes1,2 and coronary artery disease3 and for elderly individuals with multiple illnesses,4–6 generally including 5–10 patients per group.2,6 Previous trials have demonstrated improvements in patient satisfaction and quality of life,1,4–6 and potential for decreasing health care utilization and spending.2,5,6

Consistent with the Chronic Care Model,7 group patient visits address limitations in current care for chronic conditions, including time constraints on practitioners and inadequate patient education to improve illness management. They also meet many aims for improving health care quality identified by the Institute of Medicine, including providing patient-centered, efficient care in a model where the patient is the source of control and information flows freely.8 By addressing elements of high-quality chronic disease care, such as delivering health information efficiently to patients with chronic conditions, providing socialization opportunities, and offering an alternative to the brief visits, group patient visits offer a viable alternative for the 130 million Americans with chronic conditions.9

While group patient visits are increasingly common and used by 8% of family practitioners,10 the model has had very limited application for neurologic conditions11 and has not yet been evaluated in PD. We therefore developed a randomized, controlled trial to determine the feasibility of using group patient visits to provide care to individuals with PD, and to compare the effectiveness of these visits with usual one-on-one medical appointments.

METHODS

Study population.

We recruited individuals with PD who regularly attended the movement disorders clinic at the University of Rochester to see one of 3 study physicians (E.R.D., F.J.M., K.M.B.). Patients were approached in the clinic at initial and follow-up visits to solicit interest in the study. If additional patients were needed to complete enrollment, they were contacted from a roster of clinic patients based on the investigator's perception of their likelihood of participating in a study of group visits. In order to participate, individuals were required to be at least 30 years of age, have a clinical diagnosis of idiopathic PD, and be willing and able to provide informed consent and participate actively in group patient visits. All individuals who provided consent were invited to have a caregiver (any unpaid spouse, significant other, family member, or friend) consent to participate in group patient visits and complete study activities as well.

Standard protocol approval, registrations, and patient consent.

This study was approved by the Research Subjects Review Board at the University of Rochester. All study participants, including caregivers, signed an informed consent document before any study activities were initiated. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov, identifier NCT00528086.

Study design.

This study was a randomized trial of group patient visits vs usual (one-on-one) care for individuals with PD. At baseline, we randomized individuals to receive either group patient visits or usual care in a 1:1 ratio according to a block-balanced computer-generated randomization plan. Randomization was stratified by physician.

Intervention.

In this study, group patient visits included both patients and their caregivers, led by a physician in the clinical setting. Our visits lasted approximately 90 minutes, and included 5 minutes of introductions, 10 minutes of patient updates (which could include personal accounts of disease status, general life changes, or family news that occurred since the previous visit), and a 40-minute educational session that had been chosen by the participants at the previous session. Examples of educational topics included drug and nondrug therapies for PD, disease progression and prognosis, and deep brain stimulation. After a brief 15-minute break, approximately 20 additional minutes were spent completing the educational session, addressing any patient or caregiver questions, discussing current research opportunities, and selecting educational topics that would be presented at the next group session.

Patients were scheduled to meet briefly (e.g., 10 minutes) with the study physician for one-on-one visits prior to or after the group session. This provided the opportunity to discuss personal matters or to address individual concerns (e.g., medication dosage) that were unique to the individual.

Over the course of the 12-month study, group patient visits took place approximately once every 3 months. If needed, individuals randomized to group patient visits could attend an unscheduled one-on-one visit with the study physician between sessions. Individuals in the usual care group saw the physician whom they had previously seen for their care, and could maintain a similar visit schedule as those attending group patient visits or schedule visits more or less frequently as appropriate for each individual. Generally patients in the usual care group saw their physician every 3–6 months for approximately 30-minute visits as is typical in our clinic. In addition, all study participants were encouraged to contact the physicians' office via telephone at any time for issues that occurred between visits (e.g., medication refills, acute changes in disease state).

In this research study, participants in both groups were not billed for services provided as part of their participation.

Outcome measures.

The primary outcome measure was feasibility, as measured by the ability to recruit participants for the study and by the proportion of participants and caregivers who completed the study.

In addition, we evaluated other outcomes, including quality of life as measured by the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire–39 (PDQ-39), a questionnaire specific to individuals with PD,12 and EuroQol-5D, a generic quality of life scale previously used in PD trials13; PD symptoms as measured by the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale total score, the standard questionnaire that rates disease symptoms in patients with PD14; depression as measured by the Geriatric Depression Scale–15, a scale of depressive symptoms that has been used in PD trials15; cognition as measured by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, a 30-point scale that can detect mild cognitive impairment and has been used extensively in patients with PD16; patient satisfaction as measured by the Group Health Association of America's Consumer Satisfaction Scale, a generalized satisfaction scale modified to account for essential aspects of a PD clinic visit17; and caregiver burden as measured by the Zarit Burden Interview, a general scale used to examine the effects of caregiving.18

Statistical analysis.

The baseline characteristics of the patients and caregivers randomized to group patient visits or usual care were compared using Fisher exact test for categorical outcomes and t tests for continuous outcomes. Measures of quality of life, PD symptoms, depression, cognition, patient satisfaction, and caregiver burden at 12 months after baseline were analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models. Each model included treatment group as the factor of interest, physician as a stratification factor, and corresponding baseline score as a covariate. The underlying assumptions of the ANCOVA models were thoroughly checked, and possible interactions between treatment and other factors were investigated. Analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle and included all randomized subjects. For missing responses, we carried the last observation forward. Separate supportive analyses were also performed excluding participants who had incomplete follow-up, with comparable results. All statistical tests were performed at the 2-sided significance level of 5%, and no correction was made for multiple testing.

Sample size calculations.

In this pilot study, the total sample size was determined based on feasibility. Because of the small sample size, we did not have adequate power to detect potentially meaningful differences in the various outcome measures (e.g., PDQ-39).

RESULTS

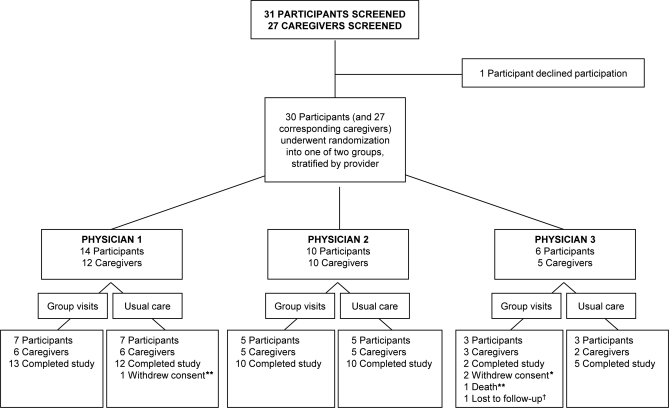

Between October 2007 and September 2008, 31 patients and 27 caregivers signed consent to participate in this study, though one patient declined participation after signing the consent (figure). Randomization was stratified so that all patients would attend clinic appointments (either group patient visits or one-on-one visits) with the same physician who had provided care for their PD prior to study enrollment. As a result, physician 1 enrolled 14 patients and 12 caregivers, physician 2 enrolled 10 patients and 10 caregivers, and physician 3 enrolled 6 patients and 5 caregivers. Randomization was stratified within these physician groups, leaving a total of 15 individuals and 14 caregivers assigned to group visits, and 15 individuals and 13 caregivers assigned to receive usual care. The study concluded per protocol after the completion of 12-month assessments by participants in the third group.

Figure. Screening and enrollment of study participants.

*Includes one participant and one caregiver. **Individual was a participant. †Individual was a caregiver.

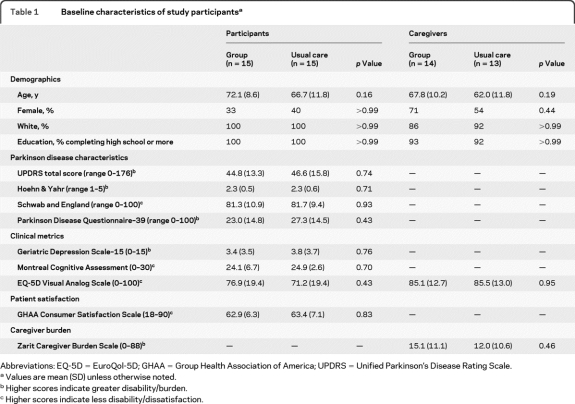

The baseline characteristics of the patients and caregivers randomized to group patient visits and usual care did not differ significantly (table 1). Twenty-seven (90%) of the 30 study participants completed the study. Two patients withdrew consent after participating in one group patient visit each and resumed one-on-one care with the same physician, each reporting a preference for usual care. A third patient was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and died prior to completing the final study visit. In addition, 25 (93%) of the 27 participating caregivers completed the study. One caregiver withdrew consent with his spouse and the second was lost to follow-up. Three patients in the usual care group attended 4 unscheduled visits outside of the scheduled study appointments. One patient who had previously undergone deep brain stimulation surgery required 2 additional visits for a stimulator adjustment, and the other patients elected to attend unscheduled visits with a nurse practitioner or providing physician. All group visits were completed as scheduled. No patients receiving group patient visits had an unscheduled visit.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participantsa

Abbreviations: EQ-5D = EuroQol-5D; GHAA = Group Health Association of America; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale.

Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise noted.

Higher scores indicate greater disability/burden.

Higher scores indicate less disability/dissatisfaction.

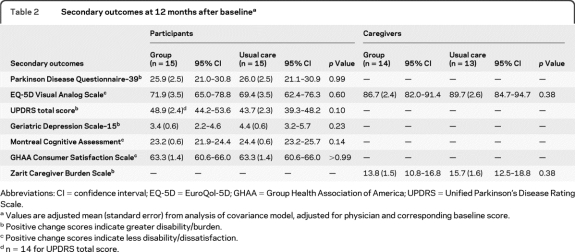

Regarding quality of life, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups at 12 months after baseline (25.9 points for those in group visits vs 26.0 points for usual care; p = 0.99), as measured by the PDQ-39. Similarly, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups on other measures of quality of life, PD symptoms, depression, cognition, patient satisfaction, or caregiver burden (table 2). No adverse events related to the intervention were reported in either group.

Table 2.

Secondary outcomes at 12 months after baselinea

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; EQ-5D = EuroQol-5D; GHAA = Group Health Association of America; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale.

Values are adjusted mean (standard error) from analysis of covariance model, adjusted for physician and corresponding baseline score.

Positive change scores indicate greater disability/burden.

Positive change scores indicate less disability/dissatisfaction.

n = 14 for UPDRS total score.

At the study's conclusion, participants were asked to give their preference for either group patient visits or their usual care with the same physician. Of the 14 responders receiving group visits, 8 preferred the group setting, 5 preferred usual care, and 1 was indifferent. Among the 14 responders receiving usual care, 5 indicated a preference for group visits, 6 for usual care, and 3 were undecided. Differences in preference were not significant between the 2 groups (p = 0.48). No patient in either group patient visits or usual care reported a breach of confidentiality when asked on a self-report questionnaire.

DISCUSSION

Based on this study, group patient visits are a feasible model for providing care for individuals with PD. While group visits have demonstrated clinical benefits in studies of other chronic conditions,1–6 in this small pilot study we were unable to detect significant differences in quality of life, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, or caregiver burden between those receiving group patient visits and usual care.

Group patient visits have the potential to address limitations of support groups and one-on-one visits in PD. While both support groups and traditional visits have clear benefits, a survey of individuals with PD indicates that patients desire a credible group leader for their support groups and more information for them and their caregivers about their disease.19 By incorporating a PD specialist as a group's leader and allocating more time, principally for education, group patient visits can address these limitations. In addition, the longer duration of group patient visits allowed physicians the unique opportunity to observe patients for longer periods and visualize disease characteristics such as wearing off and motor fluctuations, daytime sleepiness, eating, and interpersonal interactions that would not otherwise be observed in a brief one-on-one visit. In our study, for example, we noticed all above, which although often reported in a clinical visit, were more informative to see in person.

Our study design was limited by the use of only one study site, differences in the size of the groups and time spent with patients in each group, and the incorporation of 3 separate study physicians leading different groups for their patients. This created variable group sizes and differences in the way the groups were conducted and may have contributed to modest differences in outcomes by provider, although no significant differences between providers were observed. Our sample size was modest, and this may have contributed to a lack of power to detect significant differences in many important outcome measures. Furthermore, the study population was relatively homogenous (e.g., all white, high school graduates with mild to moderate disease), so these results may not generalize to other populations or individuals with more severe disease. Finally, we did not include a qualitative analysis into this study, which could have provided a better impression of the feelings of participants and caregivers about group visits, including specific factors that they did and did not like.

Certain logistical issues (e.g., need for a large room, scheduling visits in blocks that are atypical) may pose ongoing difficulties when conducting group patient visits. These visits may increase the burden on scheduling and room management, which are currently geared toward traditional one-on-one visits. Physicians must also spend additional time organizing group sessions in advance and be able to manage a group. While the visit duration may facilitate the opportunity to observe patients for extended time periods, there is also the risk that a lack of thorough, one-on-one examination may cause the physician to miss subtle diagnoses or disease characteristics. This issue could be resolved by considering a hybrid treatment model that alternates group and one-on-one patient visits over the course of a year.

Finally, reimbursement remains an issue which may make this model difficult for physicians to sustain. Current guidance from Medicare suggests that billing for services provided within a group can be done using standard evaluation and management codes, but no official payment or coding related to group visits have been published by Medicare.20 With modest group sizes, such as those in this study, physicians could see an equivalent number of patients per unit-time in a one-on-one setting as they could in a group. The recently enacted US health care reform creates a new Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation21 whose purpose is to “test innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce program expenditures.”22 Changes in reimbursement could foster alternative delivery models for PD and other chronic neurologic conditions whose burden will only grow in the future.23–25

More broadly, due to their burden and cost,26 studies comparing the effectiveness of alternative health care delivery models for patients with neurologic conditions are limited,27 and additional trials are needed. The Institute of Medicine lists health delivery as its top research priority in its recent report on comparative effectiveness research. Included among the specific priorities are comparing the effectiveness of coordinated, physician-led, interdisciplinary care in multiple settings for individuals with advanced chronic disease, comparing the effectiveness and costs of alternative detection and management strategies for dementia, and comparing the effectiveness of comprehensive care coordination for those with severe chronic disease.28 Future studies are needed that include a larger study population, multiple study sites, and qualitative and economic analyses of group patient visits. This research can guide future care delivery models, inform the design and conduct of future studies of care delivery, and demonstrate the importance of evaluating new models of health care delivery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr. Robert Holloway (Department of Neurology, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY) for his contributions to the study conception and conduct.

- ANCOVA

- analysis of covariance

- PD

- Parkinson disease

- PDQ-39

- Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire–39

Editorial, page 1538

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Statistical analysis was conducted by Dr. Christopher Beck.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Dorsey serves as a consultant to Lundbeck Inc. and Medtronic, Inc.; has served as a consultant for Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Inc.; holds stock options in Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Inc.; and has received research support from Amarin Corporation, Medivation, Inc., American Academy of Neurology Foundation, American Parkinson Disease Association, CHDI Foundation, Inc., Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, National Parkinson Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the NIH. L.M. Deuel reports no disclosures. Dr. Beck serves as a biostatistical reviewer for Neurology® and has received research support from Amarin Corporation, Guidant Corporation, Boston Scientific, CHDI Foundation, Inc., the National Parkinson Foundation, and the NIH. I.F. Gardiner has received research support from the NIH (NINDS, NICHD), the National Parkinson Foundation, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, and the Northwestern Dixon Fund. N.J. Scoglio reports no disclosures. Dr. Scott serves on the speakers' bureau for Merck Serono. Dr. Marshall serves on a scientific advisory board for and has received funding for travel from Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd.; serves on the editorial board of the European Journal of Neurology; and has received research support from Medivation, Inc., Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., St. Jude Medical, Inc., the NIH, and the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research. Dr. Biglan serves on a scientific advisory board for the Tourette's Syndrome Association; serves as a consultant for Theravance, Inc.; and receives research support from Marvell Technology Group Ltd., Presbyterian Home of Central New York, ROHM Services Corporation, Google, the NIH (NINDS, NHGRI), the National Parkinson Foundation, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research.

REFERENCES

- 1. Trento M, Passera P, Tomalino M, et al. Group visits improve metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. Diabetes Care 2001;24:995–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: a system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2001;24:695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Masley S, Phillips S, Copeland JR. Group office visits change dietary habits of patients with coronary artery disease: The Dietary Intervention and Evaluation Trial (DIET). J Fam Pract 2001;50:235–239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coleman EA, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, Wagner EH. Chronic care clinics: a randomized controlled trial of a new model of primary care for frail older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:775–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beck A, Scott J, Williams P, et al. A randomized trial of group outpatient visits for chronically ill older HMO members: the cooperative health care clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:543–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scott JC, Conner DA, Venohr I, et al. Effectiveness of a group outpatient visit model for chronically ill older health maintenance organization members: a 2-year randomized trial of the cooperative health care clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:1463–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff 2001;20:64–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Institute of Medicine Crossing the Quality Chasm. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Partnership for Solutions National Program Office Chronic conditions: making the case for ongoing care: September 2004 update. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/pr/product.jsp?id=14685. Accessed May 21, 2010

- 10. Tergesen A. Group healing. Wall Street Journal. December 19–20, 2009:R6 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lessig M, Farrell J, Madhavan E, et al. Cooperative dementia care clinics: a new model for managing cognitively impaired patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1937–1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peto V, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Greenhall R. The development and validation of a short measure of functioning and well-being for individuals with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res 1995;4:241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schrag A, Selai C, Jahanshahi M, Quinn NP. The EQ-5D: a generic quality of life measure is a useful instrument to measure quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:67–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fahn S, Shoulson I, Kieburtz K, et al. Levodopa and the progression of Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2498–2508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ertan FS, Ertan T, Kiziltan G, Uygucgil H. Reliability and validity of the Geriatric Depression Scale in depression in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:1445–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gill DJ, Freshman A, Blender JA, Ravina B. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment as a screening tool for cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2008;23:1043–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davies AR, Ware JE. GHAA's Consumer Satisfaction Survey and User's Manual, second ed Washington, DC: Group Health Association of America; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: a longitudinal study. Gerontologist 1986;26:260–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dorsey ER, Voss TS, Shprecher DR, et al. A U.S. survey of patients with Parkinson disease: satisfaction with medical care and support groups. Mov Disord Epub 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Academy of Family Physicians Coding for group visits. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/practicemgt/codingresources/groupvisitcoding.html. Accessed May 21, 2010

- 21. Mechanic R, Altman S. Medicare's opportunity to encourage innovation in health care delivery. N Engl J Med 2010;362:772–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. One Hundred Eleventh Congress of the United States of America H.R. 3590: Patient protection and affordable care act. Available at: http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=111_cong_bills&docid=f:h3590enr.txt.pdf#page=144 Accessed May 21, 2010

- 23. Dorsey ER, Constantinescu R, Thompson JP, et al. Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology 2007;68:384–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hirtz D, Thurman DJ, Gwinn-Hardy K, Mohamed M, Chaudhuri AR, Zalutsky R. How common are the “common” neurological disorders? Neurology 2007;68:326–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet 2005;366:2112–2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noyes K, Liu H, Li Y, Hollway R, Dick AW. Economic burden associated with Parkinson's disease on elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Mov Disord 2006;21:362–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lakshminarayan K, Borbas C, McLaughlin B, et al. A cluster-randomized trial to improve stroke care in hospitals. Neurology 2010;74:1634–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Institute of Medicine Initial national priorities for comparative effectiveness research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2009 [Google Scholar]