Abstract

Background:

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A (CMT2A), the most common form of CMT2, is caused by mutations in the mitofusin 2 gene (MFN2), a nuclear encoded gene essential for mitochondrial fusion and tethering the endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Published CMT2A phenotypes have differed widely in severity.

Methods:

To determine the prevalence and phenotypes of CMT2A within our clinics we performed genetic testing on 99 patients with CMT2 evaluated at Wayne State University in Detroit and on 27 patients with CMT2 evaluated in the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. We then preformed a cross-sectional analysis on our patients with CMT2A.

Results:

Twenty-one percent of patients had MFN2 mutations. Most of 27 patients evaluated with CMT2A had an earlier onset and more severe impairment than patients without CMT2A. CMT2A accounted for 91% of all our severely impaired patients with CMT2 but only 11% of mildly or moderately impaired patients. Twenty-three of 27 patients with CMT2A were nonambulatory prior to age 20 whereas just one of 78 non-CMT2A patients was nonambulatory after this age. Eleven patients with CMT2A had a pure motor neuropathy while another 5 also had profound proprioception loss. MFN2 mutations were in the GTPase domain, the coiled-coil domains, or the highly conserved R3 domain of the protein.

Conclusions:

We find MFN2 mutations particularly likely to cause severe neuropathy that may be primarily motor or motor accompanied by prominent proprioception loss. Disruption of functional domains of the protein was particularly likely to cause neuropathy.

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease 2A (CMT2A) is the most frequent form of CMT2, comprising ∼20% of patients and families,1 and is caused by mutations in the nuclear encoded mitochondrial gene mitofusin 2 (MFN2).2 MFN2 is a highly conserved, nuclear encoded mitochondrial GTPase that is a component of the outer mitochondrial membrane and an essential regulator of fusion of mitochondria to each other3,4 or to membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).5

The phenotypic characteristics of CMT2A remain poorly understood. Some studies suggest that CMT2A, like all forms of CMT2, presents with slowly progressive length-dependent weakness and sensory loss.6 However, CMT2A cases have been described that severely affect infants and children as well as those with milder phenotypes that affect mainly adults.2,7,8 Several MFN2 mutations cause optic atrophy and neuropathy (CMT6)1 or have brain MRI abnormalities or clinical pyramidal tract findings suggestive of CNS as well as PNS abnormalities (CMT5).

We find that, unlike previous reports, almost all patients with CMT2A that we have evaluated have had severe early-onset neuropathies with most nonambulatory by age 20. Interestingly, some patients presented with pure motor abnormalities whereas other patients had profound proprioception loss in addition to weakness. As has been found in other series,2,9 most of the mutations affecting our patients were in either the GTPase or coiled-coil domains of MFN2, although we also identified a group of severely affected patients within the conserved R3 domain of the protein.

METHODS

Patient ascertainment and evaluation.

We defined CMT2 as inherited axonal neuropathies in which nerve conduction velocities in the upper extremities were >38 m/s.10,11 This value was used as a cutoff for both the Detroit and London patients. Compound muscle action potential (CMAP) or sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) amplitudes were reduced or absent, though in milder cases these reductions may only have been evident in the lower extremities. CMT2 can be difficult to distinguish from an idiopathic axonal neuropathy when there is no family history, which was the case in some patients with and without MNF2 mutations. Features that suggested CMT2 in such patients were the absence of known causes of axonal neuropathy, foot abnormalities such as pes cavus, and a history of progression similar to other forms of CMT such as gradual onset and presentation within the first 2 decades of life, or symmetric involvement.

At Wayne State University (WSU), the authors evaluated 99 patients diagnosed with CMT2. Evaluations consisted of a neurologic history and examination, completion of a family history, calculation of a CMT Neuropathy Score (CMTNS), and performance of nerve conduction studies (NCS). After determining which patients met CMT2 criteria, those patients were tested for MFN2 mutations.

At the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, the authors evaluated 27 patients diagnosed with CMT2. Evaluations were similar to those at WSU although only those patients with MFN2 mutations received the same detailed evaluation with a prospective CMTNS and examination that was identical to that performed in Detroit.

CMTNS.

The severity of the peripheral neuropathy was determined for all evaluated patients by the CMTNS, a validated measurement of disability for patients with CMT.12 The CMTNS is a composite score based on the history of symptoms (total possible points = 12), the neurologic examination (total possible points = 16), and clinical neurophysiology (total possible points = 8); the maximum score is 36 points. Patients with mild, intermediate, and severe disability typically have a CMTNS between 1 and 10, 11 and 20, and 21 or greater.13

Clinical electrophysiology, MRI, and neuro-ophthalmologic evaluations.

NCS were performed by standard techniques utilizing either Nicolet Viking or Synergy (Oxford Medical Systems) EMG systems. Temperature was maintained at 34°C. Surface electrodes were used in all studies. Sensory conduction studies were performed using antidromic techniques (except the median and ulnar nerve studies in London, which were done orthodromically). Nerve conduction velocities were calculated by standard techniques. Standard techniques for MRI and neuro-ophthalmology were utilized.

Genetic testing.

Genetic testing was performed for both sites using polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing of all exons. Genetic testing through the neurogenetic diagnostic laboratory in the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, UK, was performed for MFN2 mutations on samples referred from patients with CMT2. In addition, patients at WSU who were personally evaluated by the authors and diagnosed with CMT2 underwent genetic testing performed by Athena Diagnostic Laboratories (Worcester, MA).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The Institutional Review Board at Wayne State University and the ethical standards committee at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London approved the studies performed in this project. All patients signed consent forms.

RESULTS

Characterization of patient cohort.

Ninety-nine patients were identified at WSU as having CMT2. The authors evaluated all of these. Forty-four of the patients had mild clinical impairment (CMTNS <10), 42 had moderate clinical impairment (CMTNS 11–20), and 19 had severe clinical impairment (CMTNS >21). Patient ages ranged from <1 year to 90 years and were equally divided into males and females (42 female, 57 male). MFN2 sequencing was performed in all 99 WSU patients (from 93 families). Twenty-one of the 99 patients (21%) had disease-causing mutations (11 female, 10 male).

Separately, MFN2 sequencing was performed on samples from 27 patients in the United Kingdom with a diagnosis of CMT2. Six of these 27 samples (22%) were found to have MFN2 mutations. Combining these results, approximately 21% (21/126) of our patients with CMT2 have CMT2A. Therefore patients evaluated in our clinics have a similar prevalence of MFN2 mutations to what has been published by other centers.2,7,9

The authors evaluated the 21 of the patients identified at WSU with MFN2 mutations and the 6 patients with MFN2 mutations identified in the United Kingdom. Combining these numbers, we personally evaluated 27 patients with CMT2A. The authors evaluated all 78 patients without MFN2 mutations seen in Detroit and all 21 patients without MFN2 mutations seen in London. However, the 21 London patients without MFN2 mutations were not evaluated in the same detail as the 6 with MFN2 mutations. Thus we did not use these 21 London patients without MFN2 in our subsequent clinical evaluations. Only the 78 Detroit patients without MFN2 mutations were used in comparison studies of patients with and without CMT2A.

Characterization of MFN2 mutations.

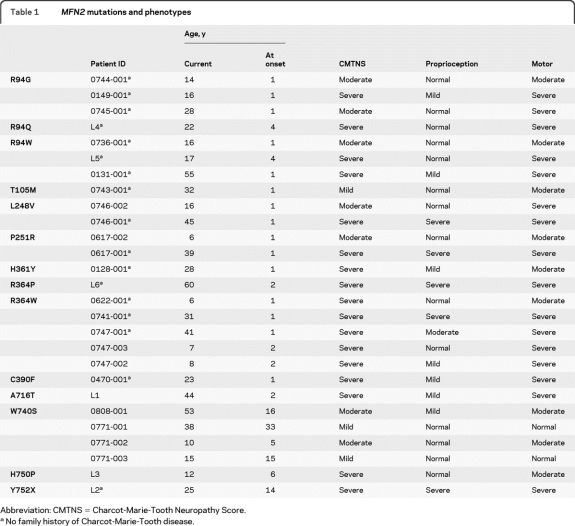

All disease-causing mutations were missense mutations, resulting in amino acid substitutions. The individual mutations in the 27 (from 21 different families) patients we evaluated are listed in table 1. Three separate families each had the Arg94Gln, Arg94Trp, and Arg364Trp mutations. Arg364 also had multiple mutations, with an Arg364Pro substitution affecting one family in addition to the Arg364Trp substitutions described above. Six mutations were in the large GTPase domain near the N-terminus (R94G, R94Q, R94W, T105M, L248V, P251R); 3 mutations were located in the 2 coiled-coil domains near the C terminus (W740S, H750P, Y752X), 3 mutations were in the highly conserved R3 region (H361Y, R364P, R364W), a single mutation was in a nonconserved cysteine residue at 390 (C390F), and a single mutation was adjacent to the C-terminus coiled-coil domain (A716T). No mutation was identified in the p21Ras domain. The locations of the mutations observed in our families are shown in the figure. Three of the mutations within the GTPase domain (R94G, R94W, T105M), 2 mutations in the R3 region (H361Y, R364W), and one of the mutations in the C-terminus coiled-coil domain (W740S) have previously been reported to cause CMT2A.2,8,9,14–16 The remaining mutations have not been previously identified.

Table 1.

MFN2 mutations and phenotypes

Abbreviation: CMTNS = Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy Score.

No family history of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

Figure. Illustration of MFN2 molecule is shown in which mutations are identified in relation to the functional domains of the molecule.

*Mutation that resulted in vision impairment reported by patients.

Genotype–phenotype correlations.

Seventeen out of the 27 patients with MFN2 mutations had severe neuropathies with a CMTNS >21, 7 had moderate neuropathies with a CMTNS between 11 and 20, and 3 had mild neuropathies with a CMTNS below 10. Five of the 7 “moderate” patients were <16 years old. Based on their scores, these 5 will likely progress into the severe range by adulthood. The mean CMTNS for patients with MFN2 mutations was 21, in the severe range.11 Seventeen of our 19 patients with severe CMT2 (15 out of 17 families) had MFN2 mutations (90%). Seventeen patients with CMT2A presented sporadically, with no family history. Inheritance was dominant in the remaining 10. In comparison, 55 of the 78 patients (67%) evaluated at Wayne State who tested negative for MFN2 mutations had a dominant family history. Since there was not always male to male transmission we were not able to formally exclude an X-linked dominant inheritance pattern in many of these families. The 78 patients without MFN2 mutations included 41 with a mild neuropathy, 35 with a moderate neuropathy, and only 2 with a severe neuropathy. Only 10 out of 88 total patients (11%) with mild or moderate CMT2 had MFN2 mutations. The average CMTNS for those who tested negative for MFN2 was 11, the lowest level of the moderate range13 (tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Clinical features of CMT2A and non-CMT2A patients

Abbreviations: CMT2A = Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A; CMTNS = Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy Score.

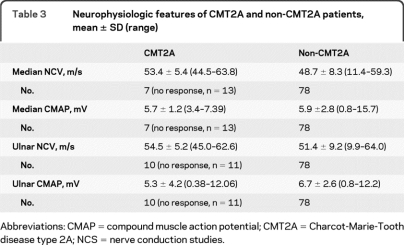

Table 3.

Neurophysiologic features of CMT2A and non-CMT2A patients, mean ± SD (range)

Abbreviations: CMAP = compound muscle action potential; CMT2A = Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A; NCS = nerve conduction studies.

We next compared other features between our patients evaluated with CMT2A and those evaluated at WSU without CMT2A (tables 2 and 3). The average age at onset for patients with MFN2 mutations was 4.4 years, ranging from 7 months of 33 years. Twenty-three of the 27 patients had an onset prior to age 10. For the 15 patients with MFN2 mutations who were over 20 years of age at the time of evaluation, only 4 were ambulatory. Two unrelated ambulatory patients had the same Trp740Ser mutation.

The average age at onset for the 78 patients without MFN2 mutations was 41.4 years (range 1–82) with only 2 patients presenting with symptoms prior to age 10. All but one of these patients were ambulatory at age 20 years. Of the 27 severely affected patients, only 2 did not have MFN2 mutations. These 2 patients first noted symptoms at 15 and 30 years of age. One of the 2 was ambulatory after age 20 years.

Heterogeneous distribution of abnormalities in patients with CMT2A.

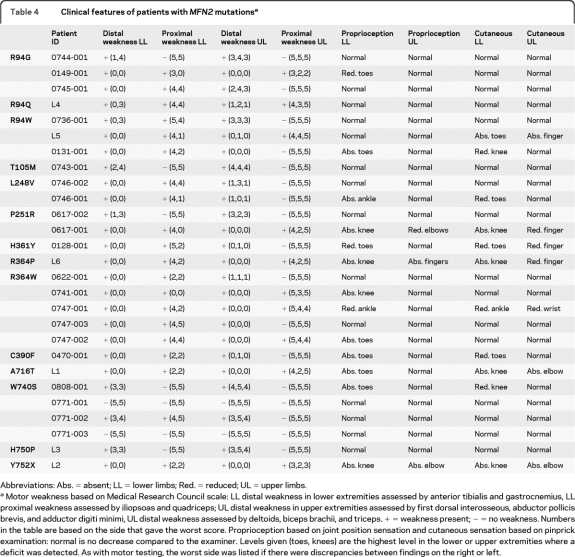

Although most of our patients with CMT2A were severely affected, the distribution of weakness and sensory loss was variable. Eleven patients presented with a pure motor neuropathy, with symptoms and signs of weakness but no sensory loss. Another 5 patients had pronounced weakness but also severe proprioception loss with abnormal position sense at their knees as well as their toes and ankles. A summary of the motor and sensory abnormalities of our patients with CMT2A is provided in table 4.

Table 4.

Clinical features of patients with MFN2 mutationsa

Abbreviations: Abs. = absent; LL = lower limbs; Red. = reduced; UL = upper limbs.

Motor weakness based on Medical Research Council scale: LL distal weakness in lower extremities assessed by anterior tibialis and gastrocnemius, LL proximal weakness assessed by iliopsoas and quadriceps; UL distal weakness in upper extremities assessed by first dorsal interosseous, abductor pollicis brevis, and adductor digiti minimi, UL distal weakness assessed by deltoids, biceps brachii, and triceps. + = weakness present; − = no weakness. Numbers in the table are based on the side that gave the worst score. Proprioception based on joint position sensation and cutaneous sensation based on pinprick examination: normal is no decrease compared to the examiner. Levels given (toes, knees) are the highest level in the lower or upper extremities where a deficit was detected. As with motor testing, the worst side was listed if there were discrepancies between findings on the right or left.

Patients with neuropathy and optic atrophy (CMT6)15 and with pyramidal tract17 and other CNS abnormalities (reviewed in 1) have been described with MFN2 mutations. Neuro-ophthalmologic examinations were performed on all patients with symptoms of visual impairment. Five patients were identified with optic atrophy (figure, asterisk). MRI studies, performed on 10 patients, were normal on 7, though changes in white matter were identified in 3. No brisk deep tendon reflexes or Babinski signs were observed.

DISCUSSION

We have determined that 21% of our patients with CMT2 have mutations in the MFN2 gene, a prevalence that is similar to what has been reported.2,7,9,18 However, the clinical heterogeneity of the patients with CMT2A we evaluated was quite different from what has been previously reported.18–20 We did not observe an equal distribution of mild and severely affected patients with CMT2A. Neither did most of our patients with CMT2A present with a “classic phenotype” of mild weakness and sensory loss in the first 2 decades of life with slow progression thereafter. Most of our patients with CMT2A developed very severe axonal neuropathies in childhood. Only 4 of 15 adult patients could ambulate independently by age 20 years. Additionally some of our patients had pure motor neuropathies whereas many others had severe proprioception loss in addition to weakness, suggesting that in some cases clinical involvement of large diameter sensory axons or their perikaryons were spared. Motor-sensory distinctions were not mutation specific as the same mutation caused both motor and sensorimotor phenotypes (table 1). Proximal limb impairment seemed to occur much earlier in our patients than with other forms of CMT such as CMT1A. While this may have been simply a function of the severity of the disease, we were struck by how early and often hip flexor and quadriceps weakness occurred. We identified 4/5 strength or less in 19 of our 27 patients. Similarly, proprioception, when altered in our patients, usually affected the ankle and sometimes the knee as well as toes. Taken together, these results suggest that impairment in CMT2A is less length dependent than in many forms of CMT, suggesting that there may be a neuronopathy component rather than simply an axonal degeneration involved in the pathogenesis.

Research into the cell biology of MFN2 suggests that particular domains are essential for the protein to induce mitochondrial fusion or tethering to the ER. Mutated MFN2 constructs bearing 4 of the mutations we evaluated have been shown to be completely unable to induce mitochondrial fusion when introduced by retroviral vectors into mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cell lines lacking Mfn1 and Mfn2 (double Mfn-null cells). Similarly none of these mutations were able to restore mitochondrial tubules, which require fusion, in cell lines.21 The R94Q mutation disrupted ER function and morphology. Other mutations affecting our patients have not been tested with respect to their abilities to disrupt mitochondria–ER tethering. However, since this tethering also requires interactions between coiled coil domains in trans between MFN2 from the ER membrane and MFN2 or MFN1 from the mitochondrial outer membrane, as well as GTPase activity,5 it is likely that many of our other mutations disrupt mitochondrial–ER interactions as well. Taken together, these data suggest that most disease-causing mutations in our patients are in regions of the MFN2 molecule necessary to induce fusion to other mitochondria, similar to what has been suggested in other series,9 as well as in domains necessary to form bridges between mitochondria and the ER. These data therefore suggest that mutations that completely prevent the MFN2-mediated fusion will cause severe neuropathy in patients.

We postulate that mutant MFN2 in our patients caused neuropathy by a “dominant-negative” mechanism in which the mutant protein prevents the MFN2 expressed by the normal allele from fusion to other mitochondria or ER. Soluble Mfn2 constructs lacking the GTPase, coiled-coil, or R3 domains prevented mitochondrial fusion mediated by wild-type Mfn2 by similar dominant negative mechanisms in in vitro systems.22 We think it likely that the mutations afflicting our patients that occur in these same domains are also acting as dominant-negatives by binding through their coiled-coil domains with wild-type Mfn2 and preventing both the wild-type and mutant Mfn2 from fusing mitochondria. Consistent with this hypothesis, we are unaware of any amino acid changing mutations acting as benign polymorphisms in these regions. We also hypothesize that mutations in other domains may not act as dominant negatives and would therefore not affect MFN2 expressed from the wild type allele. In these cases mutations would act either as benign polymorphisms or at most cause mild neuropathies. This would explain the relatively large number of missense mutations reported as polymorphisms in MFN2 compared to the low levels of polymorphisms in other autosomal dominant forms of CMT such as CMT1B, CMT1X, or CMT1E, where virtually all amino acid substitutions cause neuropathy (www.molgen.ua.ac.be/CMTMutations/default.cfm).

Why we have seen only isolated cases of milder CMT2A is not clear. We have considered whether this could simply have been an artifact of ascertainment. However we believe that this is an unlikely explanation since both the Detroit and London CMT clinics are large and follow hundreds of patients whose phenotypes for other forms of CMT are representative of those reported in the literature. The most probable explanation, in our opinion, is that mildly affected patients with CMT2A are unusual, at least in the United States and United Kingdom. Mildly affected patients presumably result from mutations that cause partial loss of MFN2 function or partial dominant negative effects on wild-type MFN2 function, but do not completely block the ability of at least wild-type MFN2 to fuse. Consistent with this hypothesis, the large pedigree with a mild form of CMT2A published by the Utah group had a Val273Gly mutation. Codon 273 is located between the GTPase and R3 domains (7) and thus may not disrupt fusion. It is also possible that the mutations in some milder cases might not be causative but may in fact be benign polymorphisms. As there are many polymorphisms within MFN2 and many patients that present without a prior family history, it can often be very difficult to be certain that particular mutations are disease causing, particularly if other family members are not analyzed.

Several of our patients have had pure motor phenotypes whereas others have also had profound loss of large fiber sensory modalities. In general, patients with normal or mild proprioception loss were younger than those with more severe sensory loss. For 3 of the mutations we have identified, L248V, P251R, and R364W, younger patients had normal or only mildly abnormal proprioception loss, whereas older patients had much more pronounced proprioception deficiencies. Taken together, these data suggest that clinical sensory abnormalities may appear later than motor abnormalities. While that seems to be the case for those 3 mutations, all 7 mutations affecting amino acid 94 had pronounced motor but minimal sensory abnormalities. Thus, certain mutation sites may preferentially affect motor neurons.

Some, but not all, of our patients had optic atrophy or CNS abnormalities, which is similar to findings from other studies that found abnormalities outside the PNS in some cases.15,19 Why a subset of patients has CNS phenotypes is not understood, since MFN2 is ubiquitously expressed. One possibility that has been proposed is that MFN1 may compensate for abnormal MFN2. Mammalian cells contain both MFN1 and MFN2, either of which can induce mitochondrial fusion; in fact, Mfn1 tethers mitochondria more efficiently than Mfn223 and OPA1 requires Mfn1 for mitochondrial fusion but will not fuse with Mfn2.24 Some cell types contain more MFN1 than others and in those cell types, such as CNS neurons, the MFN1 might compensate for the abnormal MFN2.24 Alternatively, interactions between mitochondria and the ER may differ between the PNS and CNS. Whether these hypotheses are correct and whether either can also explain why some patients have pure motor and others sensorimotor neuropathies will need to be investigated experimentally.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the patients and families for their participation in this study.

Editorial, page 1686

- CMAP

- compound muscle action potential

- CMT2A

- Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A

- CMTNS

- Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy Score

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- NCS

- nerve conduction studies

- SNAP

- sensory nerve action potential

- WSU

- Wayne State University

DISCLOSURE

S.M.E. Feely, Dr. Laura, C.E. Siskind, S. Sottile, Dr. Davis, and Dr. Gibbons report no disclosures. Dr. Reilly serves on the editorial boards of Brain, Neuromuscular Disorders, and the Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System. Dr. Shy serves on the speakers' bureau for and has received funding for travel and speaker honoraria from Athena Diagnostics, Inc.; serves on the editorial board of the Journal of Peripheral Nervous System; and receives research support from the NIH/NINDS, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and the Charcot-Marie-Tooth Association.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zuchner S, Vance JM. Molecular genetics of autosomal-dominant axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromolecul Med 2006;8:63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zuchner S, Mersiyanova IV, Muglia M, et al. Mutations in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Nat Genet 2004;36:449–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rojo M, Legros F, Chateau D, Lombes A. Membrane topology and mitochondrial targeting of mitofusins, ubiquitous mammalian homologs of the transmembrane GTPase Fzo. J Cell Sci 2002;115:1663–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Griffin EE, Detmer SA, Chan DC. Molecular mechanism of mitochondrial membrane fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006;1763:482–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Brito OM, Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature 2008;456:605–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bienfait HM, Baas F, Koelman JH, et al. Phenotype of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2. Neurology 2007;68:1658–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawson VH, Graham BV, Flanigan KM. Clinical and electrophysiologic features of CMT2A with mutations in the mitofusin 2 gene. Neurology 2005;65:197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cho HJ, Sung DH, Kim BJ, Ki CS. Mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 mutations in Korean patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2. Clin Genet 2007;71:267–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kijima K, Numakura C, Izumino H, et al. Mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 mutation in Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Hum Genet 2005;116:23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harding AE, Thomas PK. The clinical features of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy types I and II. Brain 1980;103:259–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harding AE, Thomas PK. Genetic aspects of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (types I and II). J Med Genet 1980;17:329–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grandis M, Shy ME. Current therapy for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2005;7:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shy ME, Blake J, Krajewski K, et al. Reliability and validity of the CMT neuropathy score as a measure of disability. Neurology 2005;64:1209–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Verhoeven K, Claeys KG, Zuchner S, et al. MFN2 mutation distribution and genotype/phenotype correlation in Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2. Brain 2006;129:2093–2102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zuchner S, De Jonghe P, Jordanova A, et al. Axonal neuropathy with optic atrophy is caused by mutations in mitofusin 2. Ann Neurol 2006;59:276–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neusch C, Senderek J, Eggermann T, Elolff E, Bahr M, Schneider-Gold C. Mitofusin 2 gene mutation (R94Q) causing severe early-onset axonal polyneuropathy (CMT2A). Eur J Neurol 2007;14:575–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu D, Kennerson ML, Walizada G, Zuchner S, Vance JM, Nicholson GA. Charcot-Marie-Tooth with pyramidal signs is genetically heterogeneous: families with and without MFN2 mutations. Neurology 2005;65:496–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amiott EA, Lott P, Soto J, et al. Mitochondrial fusion and function in Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2A patient fibroblasts with mitofusin 2 mutations. Exp Neurol 2008;211:115–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chung KW, Kim SB, Park KD, et al. Early onset severe and late-onset mild Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease with mitofusin 2 (MFN2) mutations. Brain 2006;129:2103–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Calvo J, Funalot B, Ouvrier RA, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2 caused by mitofusin 2 mutations. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1511–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Detmer SA, Chan DC. Complementation between mouse Mfn1 and Mfn2 protects mitochondrial fusion defects caused by CMT2A disease mutations. J Cell Biol 2007;176:405–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Honda S, Aihara T, Hontani M, Okubo K, Hirose S. Mutational analysis of action of mitochondrial fusion factor mitofusin-2. J Cell Sci 2005;118:3153–3161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ishihara N, Eura Y, Mihara K. Mitofusin 1 and 2 play distinct roles in mitochondrial fusion reactions via GTPase activity. J Cell Sci 2004;117:6535–6546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Dal Zilio B, Scorrano L. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:15927–15932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]