Abstract

Background

Little is known about intimate partner violence (IPV) and depression among low income, urban African American and Hispanic adolescent females.

Method

Interviews with 102 urban African American and Hispanic adolescent females examined physical abuse, emotional/verbal abuse, and threats, and their unique and combined associations with depression.

Results

One-quarter of the sample experienced all three types of abuse. Non-physical forms of IPV were significantly associated with depression.

Conclusions

Some urban adolescent females from lower income households experience high rates of IPV. Physical and non-physical forms of IPV are important in understanding and responding to depression in this population.

Keywords: Violence, depression, adolescence

Key Practitioner Message.

Among urban adolescent females, it is important to assess for non-physical as well as physical forms of IPV, and if detected, to also screen for depression

Adolescent females reporting higher levels of IPV may have higher levels of depression, and thus may need more extensive treatment, support, and require greater follow-up

Adolescent females who present with depression should be screened for IPV

It is important to assess for protective factors, such as social support, and make referrals accordingly. Early detection and intervention for both IPV and depression can reduce future vulnerabilities

Introduction

Close to 90% of high school-aged adolescents report that they are currently dating or have dated in the past (Wolfe & Feiring, 2000), and between 6% and 46% have experienced physical intimate partner violence (IPV) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2008; Coker et al., 2000; Foshee, 1996; Roberts, Auinger, & Klein, 2005; Silverman et al., 2001; Watson et al., 2001). Such abuse is estimated to typically emerge when adolescents are about 15 years old (Wekerle & Wolfe, 1999) but has also been identified in younger adolescents (Rennison & Welchans, 2002). One national study reported that among all females, those under age 24 had the highest per capita rates of average annual nonfatal incidents of IPV (Catalano, 2007).

IPV involves one person intentionally causing or threatening either physical or mental harm to someone with whom they are romantically or intimately involved, and can include: physical abuse, emotional/verbal abuse, threatening behaviour, sexual assault, isolation, economic abuse, or controlling behaviours (National Women’s Health Information Center, 2006). Adolescent IPV is sometimes referred to as dating violence or violence between romantic partners. Many adolescents who report experiences of IPV are both victims and perpetrators (Watson et al., 2001). Compared to males, however, adolescent females experience more severe physical violence (Molidor & Tolman, 1998), more coercion (Stark, 2007), and are more likely to experience fear or negative psychological reactions as a consequence of IPV (O’ Keefe, 2005). Threats and emotional/verbal abuse are sometimes used to intimidate or control partners with only the occasional need to use physical force to maintain control (Stark, 2007). Threats and emotional/verbal abuse are more subtle forms of IPV and often not recognised by adolescents, their parents, guardians, or service providers (e.g. primary care providers, social workers, or psychologists). Assessing only physical forms of IPV may only be capturing a smaller segment of the problem. Therefore, it is especially important to examine non-physical forms of IPV as well as physical abuse among adolescent females.

According to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), rates of physical IPV are higher among Black (13.2 %) and Hispanic (10.1%) adolescent females compared to their white counterparts (7.4 %) (CDC, 2008). Additionally, adolescent females in urban areas may be especially at risk for being abused in a dating relationship (Silverman, Raj & Clements, 2004). Living in a neighbourhood characterised by high levels of violence, poverty and social disorganisation has been correlated with a higher likelihood of experiencing IPV (Glass et al., 2003; Malik, Sorenson, & Aneshensel, 1997). A report published by the National Institute of Justice found that women living in economically distressed households and those living in disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods are most affected by IPV. The report also notes that a higher percentage of African-American women live in economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods and households and therefore experience higher levels of IPV compared to white women (Benson & Fox, 2004). According to Smith (2007), it is important to examine the epidemic of IPV as it affects abused females who are among the most marginalised in our society, in order to find solutions that will be most widely effective. Therefore, in this study we focused on low income urban African American and Hispanic adolescent females, a group who are among the most vulnerable to IPV.

Depression in adolescent females

According to the National Survey on Drug Abuse and Health conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAMHSA) (2007), an estimated 8.2% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (approximately 20 million adolescents) experienced at least one major depressive episode during the previous year. For both males and females, the transition from childhood to adolescence is marked by a dramatic increase in depression prevalence, although depression among adolescent females has been documented to increase more rapidly (Fitzpatrick et al., 2005; Lyons et al., 2006; Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study Team, 2005). Among adolescents aged 12 to 17 in 2007, the prevalence rates of major depressive episode among females (11.9 percent) were more than twice those among males (4.6 percent) (SAMHSA, 2007). Depression frequently occurs among adolescent females alongside other types of mental health symptoms and disorders such as anxiety and substance abuse (Maag & Irvin, 2005; Saluja et al., 2004). Depression and its associated syndromes can have undue and multiple effects on the developmental and psychological trajectories of adolescents, particularly among adolescent girls living in poverty and environments of violence (Diamond, Siqueland, & Diamond, 2003; Tandon & Solomon, 2009). Within the literature, there is a considerable amount of variability in prevalence rates with depressive illness from different ethnic backgrounds (Kennard et al., 2006). Some older studies have reported no or minimal differences between ethnic groups (Costello et al., 1996) while other, more recent research indicates a greater number of depressive symptoms among ethnic minority groups compared to Caucasian groups (Kubik et al., 2003; Wickrama, Noh, & Bryant, 2005; Wight et al., 2005).

Adolescent depression represents a serious public health concern as it relates to recurrent depression into adulthood, suicide, and other medical and psychological co-morbidities (Hammack et al., 2004; Repetto, Caldwell, & Zimmerman, 2004). Some consequences of adolescent depression include decreased school performance (Wong, Eccles, & Sameroff, 2003), increased STI/HIV risk related behaviours (Brown et al., 2006), and increased risk of suicide (Bhatia & Bhatia, 2007).

Relationship between IPV and depression among adolescent girls

Recent reviews of IPV among adolescent females indicate that experiencing higher rates of physical or sexual IPV are significantly associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms (Glass et al., 2003; Vezina & Herbert, 2007). These studies, however, have tended to rely on narrowly-defined measures of abuse (often excluding emotional/verbal abuse and threats), and have often used single-item measures to assess the relationship between physical IPV and depression (Howard & Wang 2003, 2005; Roberts & Klein, 2003). In order to more fully explore these associations, the current study examined IPV and depression among a sample of 15-19 year old urban African American and Hispanic adolescent girls using a multidimensional assessment of IPV. This assessment went beyond measuring only physical abuse to also include two measures of non-physical abuse - threatening behaviour and emotional/verbal abuse. The focus of this cross-sectional study was to examine: 1) the prevalence of physical and non-physical forms of IPV; and 2) the extent to which threatening behaviours, physical abuse, and verbal-emotional abuse each uniquely related to depression in low-income urban minority adolescent females.

Theoretical perspective

This analysis is situated in the theoretical perspective of cumulative adversity and protective factors as they pertain to health inequities (Hatch, 2005). According to this theoretical approach, adversity and/or advantage accumulate over the life course, leading to increasing inequities in health over time. Social status positions (e.g. SES, race, ethnicity, gender, age) shape opportunities, experiences, access to resources, and exposure to subsequent advantage and adversity. ‘For minorities or marginalised individuals, adverse experiences are fundamentally exacerbated by stigma, prejudice, and discrimination at individual and institutional levels and have strong effects on health outcomes’ (Hatch, 2005, p. 132). The timing of exposure to adversity may be more crucial at certain points of transition in the life course, and one such time is during the development of interpersonal relationships in adolescence. Furthermore, according to a stress-diatheses model, depression can be seen as a result of stressful or adverse events in the presence of predisposing factors (such as genetic, cognitive or social vulnerabilities) (Monroe & Simons, 1991). Stress that is frequent or prolonged, without the buffering effect of supportive relationships, has the most deleterious effects (Shownkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, 2009). Framed in the stress-diatheses model and theoretical perspective of cumulative adversity, IPV at critical developmental transitions may increase risk for depression, especially among those from disadvantaged groups.

Method

Sample and procedures

African American and Hispanic females aged 15-19 were recruited into the study from after-school programs and health clinics serving lower income African American and Hispanic adolescents. Additionally, participants had to be sufficiently fluent in English to understand the consent process and interview questions. Pregnant and parenting adolescents were excluded as it was thought their relationships with partners would be qualitatively different than those who had never been pregnant. Recruitment was conducted using flyers, participant referral, and through small group presentations. Adolescent females interested in participating would contact the staff and be screened for eligibility either on the telephone or in person. Written informed consent from a parent or guardian and assent was obtained for all females aged 15-17. Adolescents 18-19 years old provided their own written informed consent. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Michigan Department of Community Health and Michigan State University. Interviews, which were conducted by trained research assistants, lasted approximately one hour and were conducted in a private location. The primary investigator on the study trained all research assistants in conducting interviews and held weekly group debriefing sessions with the interviewers to review any questions or concerns. To increase participant comfort, colour-coded response cards were used so participants could point to their answers or indicate a colour as a response. All participants were given $20 to compensate them for their time and effort.

Measures

The interviews included demographic and health information, experience of IPV, and experience of depressive symptoms. Demographic information included age, race/ethnicity, and whether the adolescent or her family was receiving Medicaid or any other governmental financial assistance. Health information included drug and alcohol use, and sexual activity.

Intimate partner violence

We used the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI) to assess IPV that females experienced in the past year by a current or former boyfriend or male dating partner (Wolfe et al., 2001). The CADRI assesses multiple forms of abusive behaviour that may occur between adolescent dating partners. We used three subscales of the CADRI: (1) threatening behaviour; (2) physical abuse; and (3) emotional/verbal abuse, as recommended by Wolfe and colleagues (2001) because it is the most reliable form of the instrument. The subscales assessing partner abuse victimisation included 4 items for threatening behaviour, e.g. ‘He threatened to end the relationship’, 4 items for physical abuse, e.g. ‘He kicked, hit or punched me’ and 10 items for emotional/verbal abuse, e.g. ‘He kept track of whom I was with and where I was’. All items used a 4-point Likert scale: 1= never, 2= seldom (1-2 times in relationship), 3=sometimes (3-5 times), and 4= often (≥ 6 times). The mean of all 18 items was used for the total abuse score, with a higher score signifying more abuse (range=1-4). The CADRI was administered in an interview format. We used response cue cards that highlighted each response with separate colours. Participants could respond to a question by pointing to the cue card or by saying the colour corresponding to a response category (e.g. blue for ‘sometimes’). In our sample the Cronbach alpha reliabilities for the CADRI total score and threatening behaviour, physical abuse, and emotional/verbal abuse subscales were 0.87, 0.78, 0.67, and 0.84, respectively. Bivariate and multivariate analyses involved use of the continuous subscale scores on the CADRI. For two graphical summaries, the subscale scores were categorised as 1=never, >1 to 2.5 = seldom and >2.5 to 4 = sometimes/often. We also present a third visual summary (Venn diagram) for the abuse subscales as yes /no.

Depressive symptomatology

Depression risk was assessed using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC) developed by Weissman, Orvaschel and Padian (1980) to screen for depressive symptoms in the past week in children and adolescents. The 4-point Likert scale of the CES-DC ranged from 0 to 3, where 0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = some, and 3 = a lot. CES-DC scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating increasing levels of depression. A cut-off score of 15 or higher is suggestive of higher risk of depression. The reliability in this sample was 0.85.

Analyses

The relationship between IPV and depression was initially assessed using graphical and correlational methods to check for linearity and strength of any relationship. Linear regression models were then used to determine the relative importance of relationships after adjusting for differences in age, race (coded as African American or other), and SES (as measured by receiving any type of assistance). There were significant bivariate relationships between these demographic variables and depression and/or IPV (p<.10). Other potential covariates, such as sexual activity, number of partners, age of first intercourse, alcohol consumption and smoking, were also explored but ultimately were not significantly associated with depression in the final adjusted models.

Results

Of the 118 adolescents enrolled in the study, 102 who were currently dating responded to the abuse questions and were included in the analytic dataset. Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the sample. The median age was 16 years (range 15-19) and most girls self-identified as African American (65%). Approximately half (58%) of the teens, or their household, received some type of public assistance. About half (54%) of the sample reported engaging in sexual intercourse in the prior 3 months.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the adolescents (n=102)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 15 – 17 | 70 | 68.6 |

| 18 – 19 | 32 | 31.4 |

| Primary ethnicity/race | ||

| African American | 66 | 64.7 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 17 | 16.7 |

| Multiracial | 18 | 17.6 |

| Other | 1 | 1.0 |

| One parental figure only | 8 | 7.8 |

| Parental figure or adolescent receiving assistance | 59 | 57.8 |

| Currently dating | 102 | 100.0 |

| Sexually active in prior 3 months | 55 | 53.9 |

| Number of partners in prior 3 months | ||

| 0 | 48 | 47.1 |

| 1 | 34 | 33.3 |

| 2+ | 20 | 19.6 |

| Current smoker | 14 | 13.7 |

| Alcohol use | ||

| None | 51 | 50.0 |

| ≤ Once a month | 37 | 36.3 |

| > Once a month | 13 | 12.8 |

| Used drugs in prior 12 months | 2 | 2.0 |

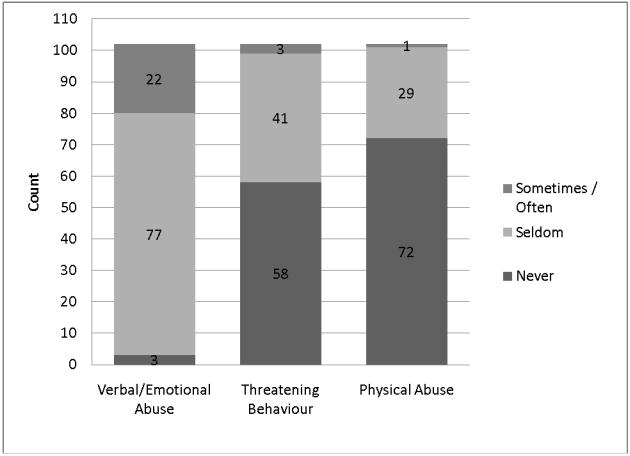

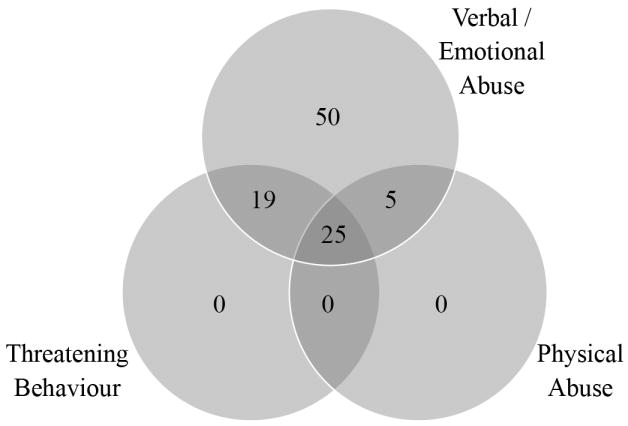

Virtually all participants (97%) reported experiencing some form of IPV in the prior year with a current or former boyfriend or dating partner. The three (3%) who reported no abuse of any kind all reported being not sexually active in the prior 3 months. Emotional/verbal abuse tended to be the abuse most commonly experienced by the participants, with most adolescents (75%) being subjected to this type of abuse ‘seldom’ (1< subscale score ≤2.5) with an additional 22% experiencing this ‘sometimes/often’ (score >2.5) (Figure 1). Forty-three percent (n=44) of the participants reported some amount of threatening behaviour, with 3% (n=3) experiencing this three or more times (sometimes/often). Physical abuse was reported by 29% (n=30) of the participants, with one female experiencing physical abuse on a regular basis. Of note, participants did not encounter either threatening behaviours or physical abuse alone (Figure 2). Both of these forms of abuse were only experienced in relationships that also exhibited other forms of abuse. One quarter (25%) of the participants reported having experienced all three types of abuse.

Figure 1.

Frequency of each type of abuse within the sample. Percentage of sample is indicated on the bars

Figure 2.

Venn diagram showing the number of adolescents experiencing any level of each type of abuse

The average CES-DC score for the sample was 19.1. Moreover, 54% (n=55) had CES-DC scores ≥15, indicating that over half of the participants were at increased risk of depression (see Table 2). The CADRI total mean score was 1.53. The total mean score of the CADRI was significantly associated with depression in bivariate (r=0.473, p<.001) and adjusted models (p<.001). Girls who experienced more abuse tended to be more depressed. In models adjusted for age, race, and SES, there was still an 11.6 point increase in the average CES-DC score for every one point increase in the CADRI total mean score (b=11.60, 95% CI=6.30-16.92, p<.001).

Table 2.

Summary of depression and abuse variables for adolescents

| Variable | N | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CES-DC | 102 | 19.09 | 12.85 |

| CADRI (abuse experienced by girl) | |||

| Total mean score | 102 | 1.53 | 0.44 |

| Threatening behaviour subscale | 102 | 1.34 | 0.59 |

| Physical abuse subscale | 102 | 1.20 | 0.38 |

| Verbal emotional abuse subscale | 102 | 2.06 | 0.63 |

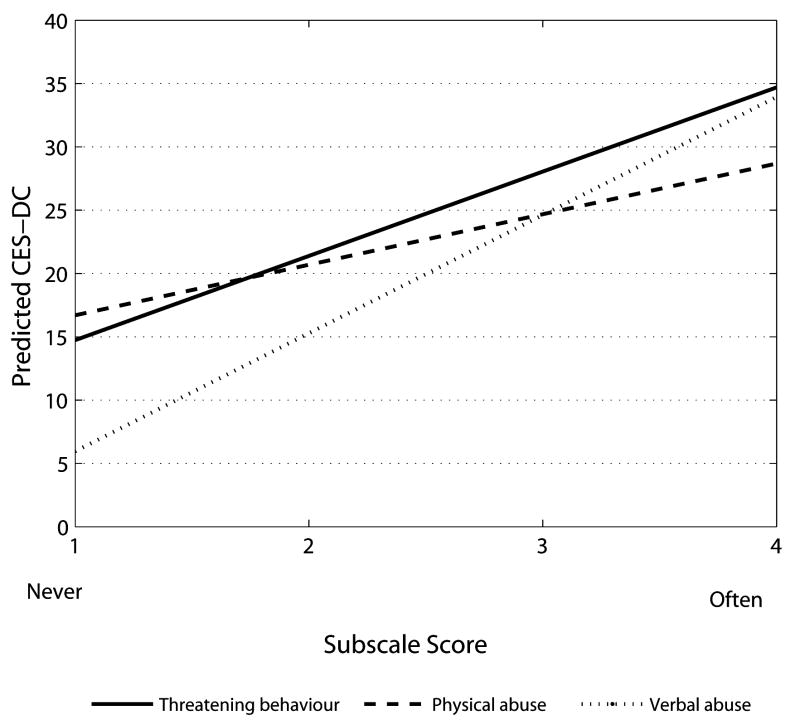

When analysing the IPV subscales separately, we found that all three subscales were associated with depression in bivariate analyses (p<.05 for all subscales). Once age, race and SES were adjusted for, however, only the threatening behaviours and emotional/verbal abuse subscales were significantly and positively associated with depression (see Table 3). Figure 3 shows the association between the three subscale scores and predicted CES-DC score for a typical 16-year-old African American adolescent not receiving any public assistance. This was the typical participant in the sample given the distribution of each variable. While emotional/verbal abuse produced the largest change in predicted CES-DC scores, experiencing a large amount of any type of abuse tended to have a similarly high predicted CES-DC score. The relative strengths of the associations with depression were compared by including three subscales in a single joint model (see Table 3). In this joint model, emotional/verbal abuse had the strongest association with depression; the only one that was still statistically significant. Thus, for every point increase in the emotional/verbal abuse subscale of the CADRI, the CES-DC increased by 9 points, on average (b=9.33, 95% CI=5.80-12.86, p<.001). The maximum correlation between any of the subscales was 0.50, thus multicollinearity was not an issue with the continuous subscale scores in this joint model. We also examined interactions between subscales to assess whether the associations with verbal/emotional abuse behaved differently in the presence of the other types of abuse. None of these interactions approached significance (p>.7) or clinically showed an impact on the predicted depression scores.

Table 3.

Regression models for the relationship between depression and CADRI sub-scales (n=102)

| Sub-scale | Independent models1 | Joint model2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B ± std.err | p-value | B ± std.err | p-value | |

| Threatening behaviour | 6.66 ± 2.08 | .002 | 3.08± 2.83 | .279 |

| Physical abuse | 3.99 ± 3.24 | .221 | -2.74 ± 3.75 | .467 |

| Verbal emotional abuse | 9.33± 1.80 | <.001 | 8.32 ± 2.11 | <.001 |

Separate model ran for each sub-scale, adjusted for age, race, and SES

Single adjusted model including all 3 sub-scales for determining relative importance of sub-scales.

Figure 3.

Predicted CES-DC scores by each type of abuse for a typical 16-year-old, African American adolescent not receiving any assistance

Discussion

IPV victimisation and depression are each significant risk factors for adolescent females, with serious consequences that last into adulthood. While some recent literature has examined the prevalence of physical and sexual violence against adolescent females, this study focused on urban minority adolescents and also included an examination of emotional/verbal abuse and threats in these young women’s lives. The adolescent females in our study reported rates of physical IPV (29%) within the range of previous studies (6-46%) (CDC, 2008; Coker et al., 2000; Foshee, 1996; Roberts et al., 2005; Silverman et al., 2001; Watson et al., 2001). Compared to findings from previous research, rates of emotional/verbal IPV in our sample were higher when examining our overall rate that included seldom occurrences (75%), but similar when comparing emotional/verbal abuse that occurred sometimes/often (22%) (Roberts et al., 2005).

The multi-item measure used in the CADRI was sensitive to capturing a range of emotional/verbal IPV, and may have contributed to the higher rates of abuse reported here. It could also be that cultural factors affected the measurement or prevalence of IPV in this sample of African American and Hispanic adolescent females, but an assessment of cultural variables was beyond the scope of this study. These findings might also indicate that some urban, adolescent females are at especially high risk for being exposed to emotional/verbal partner abuse. Threatening behaviours are usually not assessed when examining IPV among adolescents, but our findings indicate this was a common burden for young females to experience in their relationships (43%), with 3% of our sample experiencing recurrent partner threats. While 30% of adolescents in this sample experienced physical abuse, only one participant had a pattern of exposure. Within each abuse subtype, the majority of this sample had limited exposure, which might indicate they had the ability and/or supportive resources to resist on-going partner abuse. Notably, 25% of the sample encountered all three types of abuse, suggesting a substantial portion of urban adolescent females are at a high level of risk for experiencing multiple forms of IPV.

As expected, each distinct form of abuse related to the participants’ risk of depression in bivariate relationships. The association of emotional/verbal abuse with depression, in bivariate, adjusted and joint models, calls attention to a strong relationship between this type of IPV and depression. Experiencing threatening behaviour was also associated with depression in bivariate and adjusted models. We also found a statistically significant bivariate relationship between physical IPV and depression, but not in the adjusted model. This may be due to the finding that only one participant experienced physical IPV on an on-going basis. Experiencing ongoing physical abuse has been associated with greater partner psychological control in comparison to one-time exposures (Follingstad et al., 1988).While the relationship between physical abuse and depression was not statistically significant in the adjusted model, the overall measure of IPV (which included physical and non-physical abuse) was also significantly associated with depression.

The findings presented here regarding non-physical forms of abuse for adolescent females are similar to previous research with adult female samples. For example, Houry and colleagues (2006) found that emotional and physical abuse were each significantly associated with depressive symptoms in African American adult females. Yoshihama, Horrocks and Kamano (2009) found that emotional abuse, in conjunction with or separately from sexual or physical abuse, was significantly associated with negative mental health outcomes among Japanese adult women. Kramer, Lorenzon and Mueller (2004) also found that emotional abuse was as strongly associated with health problems (e.g. depression) as physical abuse in a sample of predominately Caucasian woman.

Over half (54%) of the girls in this study reported depressive symptomatology above the cut-off of 15. This is higher than the nationally representative data from the YRBS 2007, in which 36% of adolescent girls were in the clinical range of depression, even in sub-samples of girls from similar urban areas (CDC, 2008). It could be that the scale we used was more sensitive to detecting depression symptoms than the single item used in the YRBS. Cultural issues may have also influenced the measurement and prevalence of depression symptoms as well. It may also be that some African American and Hispanic female adolescents living in impoverished urban areas have relatively high levels of accumulated adversity without adequate protective factors. Therefore, these young women may have a higher than average risk for these symptoms.

The findings from this study should be considered in light of its methodological limitations. This study employed a cross-sectional design; thus, the temporality of the relationship between IPV and depression cannot be determined. Several studies have suggested that depressive symptoms may precede experience of physical or sexual intimate partner abuse for adolescents (Cleveland, Herrera, & Stuewig, 2003; Foshee et al., 2004; Lehrer et al., 2006). Therefore, adolescent females with a history of depression may be more vulnerable to subsequent abuse than those without this history. In addition, those who experience physical and/or sexual violence in their adolescent relationships are more likely to report subsequent depression as adults (Ackard, Eisenberg, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2007). Our results suggest this may include non-physical forms of abuse as well. In this cross-sectional study we were unable to examine causal relationships; therefore longitudinal studies are needed to explicate this important relationship over time.

In line with our theoretical perspective of cumulative adversity and the diatheses–stress model, different forms of IPV in this sample of African American and Hispanic adolescent females can be seen as a stress that can transform a potential for depression into actual symptoms. It has also been recognised, however, that diatheses may influence exposure to a stressor (Monroe & Simons, 1991). More specifically, one may be more vulnerable to depression due to a variety of life circumstances and exposures, which also can influence the likelihood of experiencing adverse life events such as IPV. For example, a diathesis for depression may have been activated by prior stressful exposure. Subsequently, a depressed adolescent female may be more likely to encounter IPV, possibly due to maladaptive interpersonal skills or poor partner selection decisions. In turn, the additional stress of IPV may exacerbate pre-existing depressive symptomatology. From this perspective, adolescent females exposed to recurrent IPV would be more likely to incur deleterious effects such as depression.

The time-frame specified in the questions for the CES-DC was the past week, yet some participants may have experienced depressive symptoms outside of this timeframe. Depressive symptoms not captured by this instrument could be linked to their history of dating violence. Thus, our findings could potentially underestimate the relationship between IPV and depression. Further, even though the CADRI is a multidimensional instrument, it does not measure coercive control. Additionally, the restricted version we used did not measure sexual abuse. Both of these aspects of IPV are deserving of more study. IPV may have also been underestimated since participants were asked only about one partner within the past year. Also, our measure of IPV was limited to behaviours and we do not know the intent or meaning behind any of these acts. Given that the CADRI gathers information of a sensitive nature and we used an interview format, it is possible that respondents were hesitant to divulge information related to their abuse history through this method. Thus, the occurrence and/or frequency of abuse may be underestimated.

Implications for clinical practice

The results from this study can aid practitioners in assessment and intervention. Providers who identify depressive symptoms in urban minority adolescent females should assess for both physical and non-physical forms of IPV. Given the broad range of activities that constitute IPV, assessing physical and sexual abuse alone is not sufficient. Detailed assessments of relationship dynamics, including emotional/verbal abuse and threatening behaviours can also help to identify urban minority adolescent females who may be at risk for depression. Previous research also indicates that adolescent females exposed to IPV have a greater likelihood of experiencing more severe depressive symptoms if they do not have adequate support from family and friends (Holt & Espelage, 2005; Roche, Runtz, & Hunter, 1999). With social support, these adolescents are more likely to leave an abusive relationship (Champion, Shain, & Piper, 2004). For practitioners, encouraging family support as well as greater access to community resources for adolescents in abusive relationships may be an important step in reducing the possibility of depressive symptomatology.

Depression is frequently under-recognised and under-treated among adolescents, and can be a target area for practitioners in assessment and intervention. Depressive symptoms among adolescents are often misdiagnosed as primarily conduct, attentional, or substance abuse disorders, or attributed to normal adolescent development (Saluja et al., 2004; Smith & Blackwood, 2004). Youth who experience depressive symptoms are also at risk for decreased school performance (Wong et al., 2003), increased STI/HIV risk related behaviours (Brown et al., 2006), and increased risk of suicide (Bhatia & Bhatia, 2007). Early onset of depression is predictive of more severe depression and other adverse outcomes, including poorer health, higher healthcare service utilization, and increased work impairment during adulthood (Bhatia & Bhatia, 2007; Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2007; Keenan-Miller, Hammen, & Brennan, 2007). Likewise, IPV in adolescents is often missed by primary care and social service providers. Females who experience IPV in adolescence are more likely to face IPV in their adult relationships (Teitelman et al., 2008).

As practitioners, the early detection to both multi-dimensional IPV and depression can help to identify at-risk youth in need of care and services. Provision of adequate protective factors can reduce the accumulation of further adversity and of long-term negative physical and mental health consequences (Hatch, 2005). In particular, youth with a history of prior adversity and stressors may be at greater risk for both depression and exposure to IPV, requiring more extensive treatment and follow-up.

Conclusion

IPV is a pervasive problem in adolescent relationships, with females experiencing the most severe violence. Among the urban low-income adolescent females in our sample, the prevalence of IPV appears to be especially high. While other studies have confirmed a relationship between physical abuse and depression for adolescent females, this study further differentiated how non-physical types of abuse also relate to depression. Consistent with recent research with adult victims of IPV, emotional/verbal abuse and threatening behaviours were uniquely and significantly associated with adolescent girls’ depression levels. These aspects of IPV are under-researched and too often are either unrecognised or minimised in practice, yet appear to be extremely important to identify and address. Sensitive measures are needed to examine this complex type of abuse, and practitioners need to understand not only the prevalence, but also the potentially devastating consequences if supportive intervention is not provided.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds from Michigan Department of Community Health and Michigan State University. This research was also supported by Award Number F31NR011107 (PI: Catherine C. McDonald) from the National Institute of Nursing Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health. Drs Teitelman and Ratcliffe had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- Ackard DM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Long-term impact of adolescent dating violence on the behavioral and psychological health of male and female youth. Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;151:476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson ML, Fox GL. When violence hits home: How economics and neighborhood play a role. Washington DC: National Institute of Justice; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S, Bhatia SC. Childhood and adolescent depression. American Family Physician. 2007;75(1):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Tolou-Shams M, Lescano C, Houck C, Zeidman J, Pugatch D, Lourie JK. Depressive symptoms as a predictor of sexual risk among African American adolescents and young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S. Intimate partner violence in the United States. 2007 Retrieved January 22, 2010, from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/intimate/ipv.cfm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States 2007. Morbitity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57:1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion JD, Shain RN, Piper J. Minority adolescent women with sexually transmitted diseases and a history of sexual or physical abuse. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2004;25:293–316. doi: 10.1080/01612840490274796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Herrera VM, Stuewig J. Abusive males and abused females in adolescent relationships: Risk factors for similarities and dissimilarity in the role of relationship seriousness. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18:325–339. [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King ML. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: Physical, sexual, and psychological battering. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:553–559. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Erkanli A, Stangl DK, Tweed DL. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of youth: Goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1129–1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond G, Siqueland L, Diamond GM. Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents: Programmatic treatment development. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003 Jun;6(2):107–127. doi: 10.1023/a:1023782510786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Recurrence of major depression in adolescence and early adulthood, and later mental health, educational and economic outcomes. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;191:335–342. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick KM, Piko BF, Wright DR, LaGory M. Depressive symptomatology, exposure to violence, and the role of social capital among African American adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:262–274. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR, Rutledge LL, Polek DS, McNeill-Hawkins K. Factors associated with patterns of violence toward college women. Journal of Family Violence. 1988;3:169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA. Gender differences in adolescent dating abuse prevalence, types and injuries. Health Education Research. 1996;11:275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Benefield TS, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Suchindran C. Longitudinal predictors of serious physical and sexual dating violence victimization during adolescence. Prev Med. 2004 Nov;39:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass N, Fredland N, Campbell J, Young J, Sharps P, Kub J. Adolescent dating violence: Prevalence, risk factors, health outcomes, and implications for clinical practice. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2003;32:227–238. doi: 10.1177/0884217503252033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL, Robinson WL, Crawford I, Li S. Poverty and depressed mood among urban African-American adolescents: A family stress perspective. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2004;13:309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch SL. Conceptualizing and identifying cumulative adversity and protective resources: Implications for understanding health inequalities. Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2005;60B(Special Issue):130–134. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt MK, Espelage DL. Social support as a moderator between dating violence victimization and depression/anxiety among African American and Caucasian adolescents. School Psychology Review. 2005;34:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Houry D, Kemball R, Rhodes KV, Kaslow NJ. Intimate partner violence and mental health symptoms in African American female ED patients. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2006;24:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Wang MW. Risk profiles of adolescent girls who were victims of dating violence. Adolescence. 2003;38:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Wang MW. Psychosocial correlates of US adolescents who report a history of forced sexual intercourse. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan-Miller D, Hammen CL, Brennan PA. Health outcomes related to early adolescent depression. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennard BD, Stewart SM, Hughes JL, Patel PG, Emslie GJ. Cognitions and depressive symptoms among ethnic minority adolescents. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2006 Jul;12(3):578–591. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A, Lorenzon D, Mueller G. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and health implications for women using emergency departments and primary care clinics. Women’s Health Issues. 2004;14:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubik MY, Lytle LA, Birnbaum AS, Murray DM, Perry CL. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in young adolescents. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27:546–553. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.5.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer JA, Shrier LA, Gortmaker S, Buka S. Depressive symptoms as a longitudinal predictor of sexual risk behaviors among US middle and high school students. Pediatrics. 2006;118:189–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons AL, Carlson GA, Thurm AE, Grant KE, Gipson PY. Gender differences in early risk factors for adolescent depression among low-income urban children. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2006 Oct;12(4):644–657. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maag JW, Irvin DM. Alcohol use and depression among African American and Caucasian adolescents. Adolescence. 2005;40:87–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A, Sorenson SB, Aneshensel CS. Community and dating violence among adolescents: Perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;21:291–302. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molidor C, Tolman RM. Gender and contextual factors in adolescent dating violence. Violence Against Women. 1998;4:180–194. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Simons AD. Diatheses-Stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:406–425. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Women’s Health Information Center. Violence against women: Domestic and intimate partner violence. 2006 Retrieved January 22, 2010 from http://www.womenshealth.gov/violence/types/domestic.cfm.

- O’ Keefe M. Teen dating violence: A review of risk factors and prevention efforts. 2005 Retrieved January 22, 2010, from http://new.vawnet.org/Assoc_Files_VAWnet/AR_TeenDatingViolence.pdf.

- Rennison CM, Welchans S. Intimate partner violence. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. NCJ 178247 Department of Justice; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Repetto PB, Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA. Trajectories of depressive symptoms among high risk African-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:468–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TA, Auinger P, Klein JD. Intimate partner abuse and the reproductive health of sexually active female adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TA, Klein J. Intimate partner abuse and high-risk behavior in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003 Apr;157(4):375–380. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche DN, Runtz MG, Hunter MA. Adult attachment: A mediator between child sexual abuse and later psychological adjustment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:184–207. [Google Scholar]

- Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt PC, Overpeck MD, Sun W, Giedd JN. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004 Aug;158(8):760–765. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA. 2009 Jun 3;301(21):2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Raj A, Clements K. Dating violence and associated sexual risk and pregnancy among adolescent girls in the United States. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e220–e225. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.e220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, Hathaway JE. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. JAMA. 2001 Aug 1;286(5):572–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Looking to the future: Domestic violence, women of color, the state, and social change. In: Sokoloff SJ, Pratt C, editors. Domestic violence at the margins: Reading on race, class, gender and culture. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Blackwood DHR. Depression in young adults. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2004;10:4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Stark E. Coercive control. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from The National Drug Use and Heatlh Survey: National findings. 2007 Retrieved January 22, 2010, from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k7nsduh/2k7Results.pdf.

- Tandon D, Solomon B. Risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms in urban African American adolescents. Youth and Society. 2009;41:80–99. [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Ratcliffe S, Dichter M, Sullivan C. Recent and past intimate partner abuse and HIV risk among young women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2008;37:219–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study Team. The Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): Demographic and clinical characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:28–40. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145807.09027.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezina J, Herbert M. Risk factors for victimization in romantic relationships of young women. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2007;8:33–66. doi: 10.1177/1524838006297029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JM, Cascardi M, Avery-Leaf S, O’Leary KD. High school students’ responses to dating aggression. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:339–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Orvaschel H, Padian N. Children’s symptoms and social functioning self-report scales: Comparison of mothers’ and children’s reports. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980 Dec;168(12):736–740. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekerle C, Wolfe DA. Dating violence in mid-adolescence: Theory, significance, and emerging prevention initiatives. Clinical Psychology Review. 1999;19:435–456. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Noh S, Bryant CM. Racial differences in adolescent distress: Differential effects of the family and community for Blacks and Whites. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33:261–282. [Google Scholar]

- Wight RG, Aneshensel CS, Botticello AL, Sepulveda JE. A multilevel analysis of ethnic variation in depressive symptoms among adolescents in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2005 May;60(9):2073–2084. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Feiring C. Dating violence through the lens of adolescent romantic relationships. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:360–363. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005004007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman A. Development and validation of the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1197–1232. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihama M, Horrocks J, Kamano S. The role of emotional abuse in intimate partner violence and health among young women in Yokohama, Japan. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:647–653. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.118976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]