Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To develop and validate a single numeric comorbidity score for predicting short-and long-term mortality, by combining conditions in the Charlson and Elixhauser measures.

STUDY DESIGN AND SETTING

In a cohort of 120,679 Pennsylvania Medicare enrollees with drug coverage through a pharmacy assistance program, we developed a single numeric comorbidity score for predicting 1-year mortality, by combining the conditions in the Charlson and Elixhauser measures. We externally validated the combined score in a cohort of New Jersey Medicare enrollees, by comparing its performance to that of both component scores in predicting 1-year mortality, as well as 180-, 90-, and 30-day mortality.

RESULTS

C-statistics from logistic regression models including the combined score were higher than corresponding c-statistics from models including either the Romano implementation of the Charlson Index or the single numeric version of the Elixhauser system; c-statistics were 0.860 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.854, 0.866), 0.839 (95% CI: 0.836, 0.849), and 0.836 (95% CI: 0.834, 0.847), respectively, for the 30-day mortality outcome. The combined comorbidity score also yielded positive values for two recently proposed measures of reclassification.

CONCLUSION

In similar populations and data settings, the combined score may offer improvements in comorbidity summarization over existing scores.

Keywords: comorbidity, bias, claims data, Medicare, health services research, mortality

INTRODUCTION

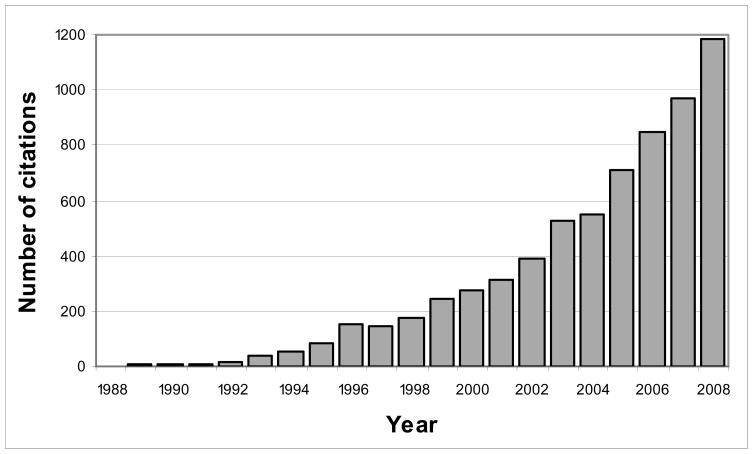

By summarizing various medical conditions into single numeric indices, comorbidity scores can provide a standardized summary of the burden of comorbidity in a study group, increase analytic efficiency [1,2], and allow for adjustment of more potentially confounding baseline conditions than otherwise possible [3]. Although more complete confounding adjustment may be achieved with other variable reduction methods, such as exposure propensity score and disease risk score methods [4–7], predefined comorbidity scores may be particularly useful in settings which preclude use of the high-dimensional approaches, such as when the number of potential confounders is large relative to both the number of exposures and outcomes [8]. Indeed, use of comorbidity scores appears to be increasing, as suggested by the exponential increase in the number of articles that have cited the seminal comorbidity score papers since their publication (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of Citations for Six Seminal Comorbidity Score Papers, 1988 to 2008.

This plot displays the number of article citations, for each year between 1988 and 2008, for the papers describing the original Charlson Index [9], its variants [10–13], and the original Elixhauser comorbidity classification system [14]. Numbers of citations were obtained from the citing articles feature (restricted to “ARTICLE”) from Web of Science®, ISI Web of Knowledge, Thomson Reuters.

The Charlson Index [9], and its implementations for claims databases [10–13], and the Elixhauser comorbidity classification system [14], are the most commonly used comorbidity measures [1,2]. The Charlson Index was developed as a prognostic index to predict 1-year mortality among patients admitted to the medical service of an acute care hospital and assigns empirically derived weights to 19 investigator-defined clinically important conditions [9]. Among the various implementations of the Charlson Index for administrative data, the Romano approach, which defines each of the comorbidities by International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 diagnosis codes with slight modifications to some conditions (e.g. leukemia and lymphoma get grouped with any tumor), consistently performs best in predicting mortality in older populations [2,15,16].

The Elixhauser system was intended to predict hospital charges, length of stay, and in-hospital mortality and was developed by identifying comorbidities relevant to hospitalization other than the primary reason for hospitalization and the severity of that condition [14]. As such, the Elixhauser system explicitly excludes important causes of substantial comorbidity; chiefly some of the most common causes of hospitalization and burden of comorbidity in elderly patients, including myocardial infarction and stroke. Nevertheless, using a new implementation of a single weighted numeric summary of the Elixhauser system, van Walraven et al [17] showed that it out-performed the Romano/Charlson measure with Medicare weights derived by Schneeweiss et al [18] in discriminating in-hospital death.

A natural next step in the improvement of comorbidity scores is to combine the conditions included in the Charlson Index and the Elixhauser classification system, thereby taking advantage of the degree of comorbidity quantified by each measure in a single comprehensive measure. The objectives of this study were to combine the Romano implementation of the Charlson Index (“Romano/Charlson”) with van Walraven’s adaptation of the Elixhauser system (“van Walraven/Elixhauser”) into a single numeric score and to empirically compare its performance in predicting short- (i.e. 30-, 90, and 180-day) and long-term (i.e. 1-year) mortality to each of the separate component measures. SAS code for the combined score can be downloaded at www.drugepi.org/downloads.

METHODS

Study populations

Similar to the approach described by Schneeweiss et al [18], this study used two cohorts – a development cohort from Pennsylvania and a validation cohort from New Jersey. We defined the development cohort from Pennsylvania as Medicare enrollees aged 65 years or older who had complete drug coverage through the Pharmacy Assistance Contract for the Elderly (PACE). Similarly, we defined the validation cohort from New Jersey as Medicare enrollees aged 65 years or older who had complete drug coverage through the Pharmacy Assistance for the Aged and Disabled (PAAD) program. Both PACE and PAAD provide medications at minimal expense to elderly individuals with low income but who do not meet the Medicaid annual income threshold.

We established the baseline year as starting on January 1, 2004 and ending on December 31, 2004 and the follow-up year as starting on January 1, 2005 and ending on December 31, 2005. For both cohorts, we included all individuals who had at least one pharmacy claim during the four months prior to the baseline year and who survived the baseline year. A total of NPA=120,679 individuals were eligible for the development cohort and a total of NNJ=123,855 individuals were eligible for the validation cohort.

For descriptive purposes, we computed several other simple measures of comorbidity using data from the baseline year. These included binary indicators for hospitalization in the baseline year, use of any prescription drug, receipt of any diagnosis, any physician visit, and whether or not patients spent time in a nursing home in the baseline year. We also measured the number of hospital days, the number of distinct prescription drugs used, the number of diagnoses, and the number of physician visits in the baseline year for each cohort.

Development of the combined comorbidity score

For each patient in the development cohort, we determined the presence or absence in the baseline year of each of the 17 conditions included in Romano’s adaptation of the Charlson Index for use with claims data and each of the 30 conditions included in the Elixhauser system. Data from both hospital discharges and ambulatory physician services were used to identify the conditions according to ICD-9 codes. Some conditions (e.g. metastatic cancer) were included and defined the same way in both comorbidity measures. When similar, but not identical, conditions were included in both scores, we chose the more inclusive definition for consideration in the combined score.

We constructed a multivariable logistic regression model by including each of the 37 unique conditions plus age and sex as independent variables. The dependent outcome variable was death during the follow-up year. The weighting rule developed by Schneeweiss et al [18] was applied to the coefficients of the logistic regression model to obtain weights for each dichotomous condition. Specifically, we divided the estimated logistic regression coefficient by 0.30 and rounded the result to the nearest integer. Thus, a weight of 1 refers to an exp(0.30) = 35% increase in odds of dying during the follow-up year, with weights increased (or decreased) by 1 point for each 0.3 increase (decrease) in the ln(odds ratio). By using this approach, variable selection is independent of the size of the development cohort and the weights assigned to conditions do not depend on the magnitude of association between other conditions and the outcome.

For each of the possible 37 comorbid conditions that a given patient had during the baseline year, s/he was assigned a weight according to the procedure described above. An individual’s combined comorbidity score was then calculated by summing his or her weights.

External validation and comparative assessment

We implemented Romano’s adaptation of the Charlson Index for use with claims data, van Walraven’s single numeric modification of the Elixhauser system, and the combined score in the validation cohort. To determine the ability of each measure to discriminate between those that died and did not die during each follow-up period, we constructed separate logistic regression models for each measure and for each outcome (i.e. 30-day, 90-day, 180-day, and 1-year mortality). Each model included as independent variables the score to be evaluated plus age and sex and included death during the follow-up period of interest as the dependent variable. From each model, we computed the c-statistic and its 95% confidence interval as a measure of discrimination [19] and compared these values across the 3 comorbidity scores.

We followed the methods described by van Walraven et al to assess the calibration of the scores in the validation cohort by comparing the observed and expected proportions of deaths for each value of each of the 3 scores that contained at least 1% of study patients [17]. Levels of scores containing less than 1% were aggregated with adjacent scores. We used exact methods to compute the 95% confidence interval around the observed proportion of death for each score value. Observed and expected proportions were deemed similar if the expected proportion was contained within this 95% confidence interval.

We also used recently proposed reclassification measures [20–22] to compare the predictive performance of the combined comorbidity score to each of its constituent scores in the validation cohort. We created a reclassification table as described by Cook and colleagues [20,23] by stratifying individuals according to their risk of 1-year mortality as predicted by the model including the Romano/Charlson score and also by the model including the combined comorbidity score. Models were also adjusted for age and sex. We defined low-, intermediate-, and high-risk strata based on predicted probabilities of each mortality outcome among those who died and did not die during the follow-up interval. We did the same to create a table to compare the van Walraven/Elixhauser score and the combined comorbidity score and then again for both the Romano/Charlson score and the van Walraven/Elixhauser score for the 30-, 90-, and 180-day mortality outcomes.

From the tables, we computed 3 reclassification measures. First, we computed the overall percentage of individuals reclassified into new risk strata by the model including the combined comorbidity score versus the model including the Romano/Charlson score [23]. We then computed the percent reclassified by the combined comorbidity score from the van Walraven/Elixhauser score. We then calculated the net reclassification improvement (NRI) [21] as NRI = [Pr(up|D = 1) − Pr(down|D = 1)] + [Pr(down|D = 0) − Pr(up|D = 0)], where D = 1 if a patient died during the follow-up period and D = 0 otherwise and “up” and “down” indicate whether an individual was reclassified into a higher or lower risk stratum, respectively, by the combined comorbidity score. The NRI can be interpreted as the sum of improvements in classification for those who experienced the outcome and those that did not, with positive numbers suggesting that the combined score classifies patients into correct risk strata more often than does the constituent score. Next, we calculated the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI), which is the mean difference in predicted probabilities between those who died and those who did not die during the follow-up year [21]. Positive numbers indicate that the combined score performs better in discriminating mortality during follow-up than does the score to which it is compared. We used the asymptotic tests derived by Pencina et al to test the null hypotheses that NRI = 0 and IDI = 0 [21].

RESULTS

The composition of the two cohorts was similar in terms of demographic characteristics and most baseline measures of healthcare utilization (Table 1). Members of the development cohort had more diagnoses, on average, as compared to members of the validation cohort (mean [SD]: 20.6 [13.1] versus 15.2 [10.7] average diagnoses in baseline year) and slightly fewer physician visits (median [IQR]: 7.0 [7.0] versus 9.0 [9.0] physician visits in baseline year). A total of 10,769 deaths occurred during the follow-up year in Pennsylvania (8.9%) and 9,230 deaths occurred in New Jersey (7.5%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Two Medicare Populations in the Development Cohort (PA/PACE) and the Validation Cohort (NJ/PAAD) During Baseline Year (2004)

| Development cohort (PA/PACE) | Validation cohort (NJ/PAAD) | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 120,679 | 123,855 |

| Age, years (SD) | 79.7 (7.3) | 78.7 (7.3) |

| Female, % | 83.4 | 76.6 |

| Any hospitalization, % | 29.3 | 27.4 |

| Median number of distinct prescription drugs (IQR) | 8.0 (5.0, 12.0) | 9.0 (5.0, 13.0) |

| Any prescription drug, % | 97.3 | 97.9 |

| Median number of distinct ICD diagnoses (IQR) | 18.0 (11.0, 27.0) | 12.0 (7.0, 20.0) |

| Any ICD diagnosis, % | 99.7 | 99.2 |

| Median number of physician visits (IQR) | 7.0 (4.0, 11.0) | 9.0 (5.0, 14.0) |

| Any physician visit, % | 95.8 | 97.5 |

| Nursing home residents, % | 9.1 | 8.9 |

| Dying in follow-up year, % | 8.9 | 7.5 |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation

The prevalence in the development cohort of each condition considered in the combined score is displayed in Table 2, along with the results of the logistic regression analysis and the corresponding new weights. In general, the relative importance of conditions based on their weights in the constituent scores was preserved in the combined score. For example, a diagnosis of metastatic cancer holds the highest weight in all 3 scores. The odds of 1-year mortality was more than 5-times greater among those with a diagnosis of metastatic cancer as compared to those without it (odds ratio [OR]: 5.17; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.66, 5.73) in our development cohort after accounting for age, sex, and all of the other comorbidities in the model.

Table 2.

Conditions Included in the Romano Implementation of the Charlson Index and the Elixhauser Comorbidity Classification System and Corresponding Weights Derived by Schneeweiss et al and van Walraven et al and New Weights Derived for Combined Score in the Development Cohort (PA/PACE) in the Baseline Year

| Condition | Prevalence in development cohort (PA/PACE, 2004), % | Medicare weights for Charlson/Romano score (based on data from 1995) | van Walraven weights for Elixhauser score (based on data from 1996–2008) | Association with 1-year mortality, odds ratio* (based on data from 2005) | 95% Confidence interval | New weights for combined score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial infarcta | 7.9 | 1 | 1.12 | 1.05, 1.19 | 0 | |

| Congestive heart failureb | 23.3 | 2 | 7 | 1.75 | 1.67, 1.84 | 2 |

| Peripheral vascular disorderc | 32.7 | 1 | 2 | 1.29 | 1.24, 1.35 | 1 |

| Cerebrovascular diseasea | 21.3 | 1 | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.09 | 0 | |

| Dementiaa | 9.0 | 3 | 1.80 | 1.69, 1.91 | 2 | |

| Chronic pulmonary diseaseb | 25.7 | 2 | 3 | 1.48 | 1.42, 1.55 | 1 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular diseasesc | 11.4 | 0 | 0 | 0.91 | 0.85, 0.97 | 0 |

| Ulcer diseasea | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | 0.90 | 0.80, 1.00 | 0 |

| Mild liver diseased | 2 | |||||

| Uncomplicated diabetesc | 23.5 | 1 | 0 | 1.16 | 1.10, 1.22 | 0 |

| Hemiplegiaa | 1.5 | 1 | 1.27 | 0.71, 2.28 | 1 | |

| Renal failurec | 6.9 | 3 | 5 | 1.61 | 1.51, 1.72 | 2 |

| Complicated diabetesc | 10.6 | 2 | 0 | 1.23 | 1.15, 1.32 | 1 |

| Any tumora | 11.6 | 2 | 4 | 1.26 | 1.19, 1.34 | 1 |

| Leukemiae | ||||||

| Lymphomae | 9 | |||||

| Moderate or severe liver diseased | 4 | |||||

| Metastatic cancerb | 1.8 | 6 | 12 | 5.17 | 4.66, 5.73 | 5 |

| HIV/AIDSb | 0.0 | 4 | 0 | 0.84 | 0.17, 4.08 | −1 |

| Cardiac arrhythmiasc | 25.2 | 5 | 1.25 | 1.19, 1.31 | 1 | |

| Valvular diseasec | 18.9 | −1 | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.09 | 0 | |

| Pulmonary circulation disordersc | 3.2 | 4 | 1.40 | 1.28, 1.53 | 1 | |

| Hypertensionc | 82.3 | 0 | 0.72 | 0.68, 0.76 | −1 | |

| Paralysisc | 1.5 | 7 | 1.03 | 0.57, 1.86 | 0 | |

| Hypothyroidismc | 25.3 | 0 | 0.96 | 0.91, 1.01 | 0 | |

| Coagulopathyc | 5.2 | 3 | 1.24 | 1.15, 1.34 | 1 | |

| Obesityc | 0.1 | −4 | 0.94 | 0.35, 2.48 | 0 | |

| Weight lossc | 1.5 | 6 | 1.81 | 1.62, 2.03 | 2 | |

| Fluid and electrolyte disordersc | 16.2 | 5 | 1.35 | 1.28, 1.42 | 1 | |

| Blood loss anemiac | 2.6 | −2 | 1.10 | 0.99, 1.22 | 0 | |

| Deficiency anemiasc | 27.4 | −2 | 1.25 | 1.19, 1.31 | 1 | |

| Alcohol abusec | 0.4 | 0 | 1.48 | 1.10, 1.98 | 1 | |

| Drug abusec | 0.2 | −7 | 0.86 | 0.58, 1.29 | 0 | |

| Psychosisc | 7.3 | 0 | 1.24 | 1.16, 1.33 | 1 | |

| Depressionc | 11.9 | −3 | 1.08 | 1.02, 1.15 | 0 | |

| Neurodegenerative disordersc | 5.2 | 6 | 1.15 | 1.06, 1.25 | 0 | |

| Liver diseasec | 1.2 | 11 | 1.32 | 1.11, 1.57 | 1 |

In addition to each of the conditions, the model was adjusted for age and sex

Romano definition used rather than Elixhauser definition

Elixhauser and Romano definitions are the same

Elixhauser definition used rather than Romano definition

Included in definition of ‘Liver disease’

Included in definition of ‘Any tumor’

Several conditions that are included in one but not the other constituent comorbidity measure were found to be relatively important and received relatively high weights in the combined score. For example, odds of 1-year mortality for those with a diagnosis of dementia were 80% higher than those for patients without a diagnosis of dementia (OR: 1.80; 95% CI: 1.69, 1.91). Thus, dementia received a weight of 2 in the combined score whereas it is not included among the Elixhauser conditions. On the other hand, the Elixhauser system assigns a high value to weight loss whereas the Romano/Charlson score does not include it. In our development cohort, a diagnosis of weight loss was found to be strongly predictive of 1-year mortality (OR: 1.81; 95% CI: 1.62, 2.03) and received a weight of 2 in the combined score. The final combined comorbidity score, including only conditions with non-zero weights, is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Combined comorbidity score conditions and weights for a Medicare population

| Condition | Weight |

|---|---|

| Metastatic cancer | 5 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 |

| Dementia | 2 |

| Renal failure | 2 |

| Weight loss | 2 |

| Hemiplegia | 1 |

| Alcohol abuse | 1 |

| Any tumor | 1 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 1 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1 |

| Coagulopathy | 1 |

| Complicated diabetes | 1 |

| Deficiency anemias | 1 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 1 |

| Liver disease | 1 |

| Peripheral vascular disorder | 1 |

| Psychosis | 1 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 1 |

| HIV/AIDS | −1 |

| Hypertension | −1 |

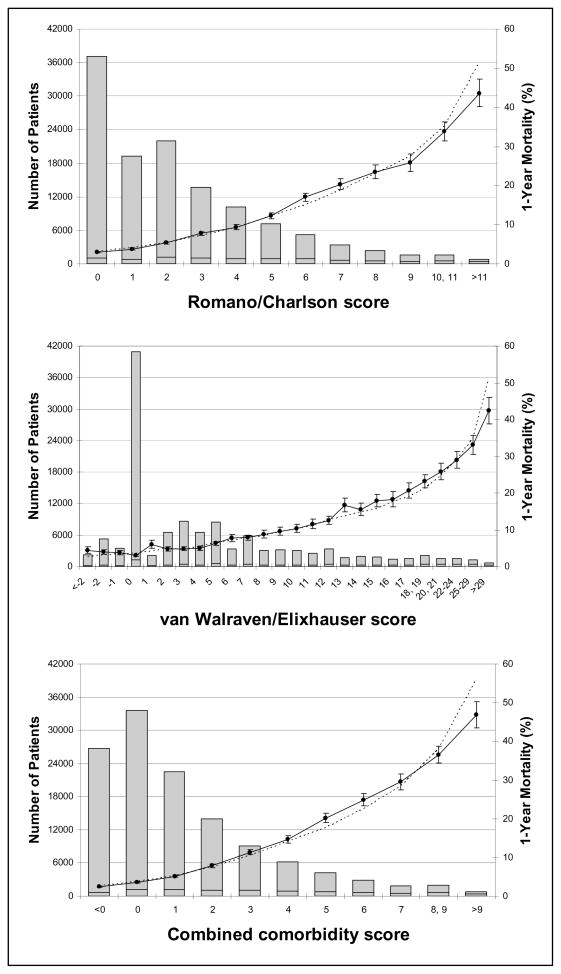

The distributions of the 3 scores in the validation cohort are depicted in Figure 2. Table 4 summarizes results for both the development and validation cohorts. The c-statistic for the combined score was 0.860 (95% CI: 0.854, 0.866) for predicting 30-day mortality in the validation cohort compared to 0.839 (95% CI: 0.836, 0.849) for the Romano/Charlson measure and 0.836 (95% CI: 0.834, 0.847) for the van Walraven/Elixhauser score (Table 5). For each measure, the c-statistic decreased monotonically with increasing follow-up for mortality. The absolute differences in c-statistics between the combined score and each of the two component scores also decreased with increasing mortality follow-up.

Figure 2. Calibration Curves for the Romano/Charlson Score, the van Walraven/Elixhauser Score, and the Combined Score for Predicting 1-Year Mortality in the Validation Cohort (NJ/PAAD).

Each plot displays the number of patients in the validation cohort having each value of the respective score (columns, left y-axis), the observed proportion (and 95% confidence interval) of deaths in 1-year among patients at a given value (solid line, right y-axis), and the corresponding predicted proportion of death in 1-year (dotted line, right y-axis). Each analysis is age and sex adjusted.

Table 4.

Distributions of Three Comorbidity Scores During the Baseline Year in Seniors in the Development Cohort (PA/PACE) and the Validation Cohort (NJ/PAAD)

| Mean | SD | Percentage with Score = 0 | Median | IQR | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development cohort (PA/PACE) | ||||||

| Romano/Charlson score | 3.00 | 2.81 | 21.0 | 2 | 4 | 0, 22 |

| van Walraven/Elixhauser score | 5.96 | 7.36 | 23.8 | 4 | 10 | −13, 58 |

| Combined comorbidity score | 1.76 | 2.59 | 22.7 | 1 | 3 | −2, 20 |

| Validation cohort (NJ/PAAD) | ||||||

| Romano/Charlson score | 2.37 | 2.54 | 29.9 | 2 | 4 | 0, 21 |

| van Walraven/Elixhauser score | 4.76 | 6.63 | 33.1 | 3 | 7 | −12, 52 |

| Combined comorbidity score | 1.23 | 2.30 | 27.1 | 1 | 2 | −2, 18 |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation

Table 5.

Comorbidity Scores and Their Discrimination for Short- and Long-Term Mortality in the Validation Cohort (NJ/PAAD)

| Measure of mortality | c-statistic (95% confidence interval) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Romano/Charlson Score | van Walraven/Elixhauser Score | Combined Score | |

| 30-day mortality | 0.839 (0.836–0.849) | 0.836 (0.834–0.847) | 0.860 (0.854–0.866) |

| 90-day mortality | 0.808 (0.805–0.813) | 0.808 (0.804–0.812) | 0.824 (0.820–0.828) |

| 180-day mortality | 0.794 (0.791–0.797) | 0.790 (0.787–0.794) | 0.806 (0.803–0.810) |

| 1-year mortality | 0.778 (0.776–0.780) | 0.772 (0.770–0.775) | 0.788 (0.786–0.791) |

Note: Models including Romano/Charlson, van Walraven/Elixhauser, and the combined score are all age- and sex-adjusted.

The observed and predicted proportions of death for each value of each measure are plotted in Figure 2 for the 1-year mortality outcome. These proportions were similar at most levels for each score, as determined by the 95% CI for the observed proportion containing the predicted proportion. The reclassification tables (Table 6 and Appendix Tables 1–3) show the number of individuals that were reclassified into new risk strata when comparing the combined comorbidity score to either of its component scores. Overall, 15.2% of individuals were reclassified from the Romano/Charlson score and also from the van Walraven/Elixhauser score, for the 1-year mortality outcome. Fewer individuals were reclassified from the two component measures for the mortality outcomes with shorter follow-up (Table 7). Both the NRI and the IDI yielded positive values for all outcomes when comparing the combined score to either the Romano/Charlson score or the van Walraven/Elixhauser score (Table 7). The NRI indicates the proportion of patients correctly reclassified by the combined comorbidity score from each of the constituent scores. Among patients who died during the follow-up year, approximately 2% were correctly reclassified by the combined score as compared to the Romano/Charlson score and the combined score correctly reclassified about 3% of those who did not die in the follow-up year. Approximately 4% and 2.5% of those who did and did not die, respectively, were correctly reclassified by the combined score as compared to the van Walraven/Elixhauser score. The IDI indicates the change in difference in average predicted probabilities between those that died and those that did not die during follow-up. The average predicted probability of 1-year mortality among those who died during the follow-up year was higher for the combined score (17.9%) than for the Romano/Charlson score (16.6%) and the van Walraven/Elixhauser score (16.3%), but the average probabilities were similar across the three measures among those that did not die during the follow-up year (6.6 for the combined score, 6.7 for the Romano/Charlson score, and 6.8 for the van Walraven/Elixhauser score).

Table 6.

Reclassification Table Comparing 1-Year Mortality Risk Strata for the Combined Comorbidity Score Versus the Romano/Charlson Score and the Combined Comorbidity Score Versus the van Walraven/Elixhauser Score in the Validation Cohort (NJ/PAAD)

| Combined score | Romano/Charlson Score |

van Walraven/Elixhauser Score |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low* | Intermediate* | High* | Total | Low* | Intermediate* | High* | Total | |

| Low* | ||||||||

| No. included | 77,908 | 8,057 | 100 | 86,065 | 77,853 | 8,158 | 54 | 86,065 |

| Deaths | 2,157 | 521 | 6 | 2,684 | 2,149 | 528 | 7 | 2,684 |

| Non-deaths | 75,751 | 7,536 | 94 | 83,381 | 75,704 | 4,630 | 47 | 83,381 |

| Observed risk, % | 2.8 | 6.5 | 6.0 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 10.2 | 13.0 | 3.1 |

| Intermediate* | ||||||||

| No. included | 4,664 | 18,326 | 2,758 | 25,748 | 5,188 | 17,736 | 2,824 | 25,748 |

| Deaths | 430 | 2,160 | 442 | 3,032 | 540 | 2,062 | 430 | 3,032 |

| Non-deaths | 4,234 | 16,166 | 2,316 | 22,716 | 4,648 | 15,674 | 2,394 | 22,716 |

| Observed risk, % | 9.2 | 11.8 | 16.0 | 11.8 | 10.4 | 11.6 | 15.2 | 11.8 |

| High* | ||||||||

| No. included | 86 | 3,126 | 8,830 | 12,042 | 166 | 3,179 | 8,697 | 12,042 |

| Deaths | 19 | 727 | 2,768 | 3,514 | 37 | 742 | 2,735 | 3,514 |

| Non-deaths | 67 | 2,399 | 6,062 | 8,528 | 129 | 2,437 | 5,962 | 8,528 |

| Observed risk, % | 22.1 | 23.3 | 31.3 | 29.2 | 22.3 | 23.3 | 31.4 | 29.2 |

| Total | ||||||||

| No. included | 82,658 | 29,509 | 11,688 | 123,855 | 83,207 | 2,6073 | 11,575 | 123,855 |

| Deaths | 2,606 | 3,408 | 3,216 | 9,230 | 2,726 | 3,332 | 3,172 | 9,230 |

| Non-deaths | 80,052 | 26,101 | 8,472 | 114,625 | 80,481 | 25,741 | 8,403 | 114,625 |

| Observed risk, % | 3.2 | 11.5 | 27.5 | 3.3 | 11.5 | 27.4 | ||

Note: light shading indicates an increase in risk category from the component score (i.e. Romano/Charlson or van Walraven) to the combined score and dark shading indicates a decrease in risk category.

Low- (<7%), intermediate- (7% to <17%), and high-risk (≥17%) strata are defined based on predicted probabilities of 1-year mortality among those who died (average predicted probability ~17%) and did not die (~7%) in the follow-up year.

Appendix Table 1.

Reclassification Table Comparing 180-Day Mortality Risk Strata for the Combined Comorbidity Score Versus the Romano/Charlson Score and the Combined Comorbidity Score Versus the van Walraven/Elixhauser Score in the Validation Cohort (NJ/PAAD)

| Combined score | Romano/Charlson Score |

van Walraven/Elixhauser Score |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low* | Intermediate* | High* | Total | Low* | Intermediate* | High* | Total | |

| Low* | ||||||||

| No. included | 85,130 | 7,129 | 41 | 92,300 | 85,096 | 7,161 | 43 | 92,300 |

| Deaths | 1,182 | 275 | 1 | 1,458 | 1,180 | 275 | 3 | 1,458 |

| Non-deaths | 83,948 | 6,854 | 40 | 90,842 | 83,916 | 6,886 | 40 | 90,842 |

| Observed risk, % | 1.4 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 3.8 | 7.0 | 1.6 |

| Intermediate* | ||||||||

| No. included | 4,958 | 16,824 | 1,927 | 23,709 | 5,242 | 16,382 | 2,085 | 23,709 |

| Deaths | 266 | 1,287 | 228 | 1,781 | 304 | 1,234 | 243 | 1,781 |

| Non-deaths | 4,692 | 15,537 | 1,699 | 1,781 | 4,938 | 15,148 | 1,842 | 1,781 |

| Observed risk, % | 5.4 | 7.6 | 11.8 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 7.5 | 11.7 | 7.5 |

| High* | ||||||||

| No. included | 54 | 2,439 | 5,353 | 7,846 | 71 | 2,464 | 5,311 | 7,846 |

| Deaths | 10 | 406 | 1,249 | 1,665 | 13 | 431 | 1,221 | 1,665 |

| Non-deaths | 44 | 2,033 | 4,104 | 6,181 | 58 | 2,033 | 4,090 | 6,181 |

| Observed risk, % | 18.5 | 16.6 | 23.3 | 21.2 | 18.3 | 17.5 | 23.0 | 21.2 |

| Total | ||||||||

| No. included | 9,0142 | 26,392 | 7,321 | 123,855 | 90,409 | 26,007 | 7,439 | 123,855 |

| Deaths | 1,458 | 1,968 | 1,478 | 4,904 | 1,497 | 1,940 | 1,467 | 4,904 |

| Non-deaths | 88,684 | 24,424 | 5,843 | 18,8951 | 88,912 | 24,067 | 5,972 | 18,8951 |

| Observed risk, % | 1.9 | 7.9 | 18.0 | 1.9 | 7.9 | 17.9 | ||

Note: light shading indicates an increase in risk category from the component score (i.e. Romano/Charlson or van Walraven) to the combined score and dark shading indicates a decrease in risk category.

Low- (<4%), intermediate- (4% to <12%), and high-risk (≥12%) strata are defined based on predicted probabilities of 1-year mortality among those who died (average predicted probability ~12%) and did not die (~4%) in the first 180 days of the follow-up year.

Appendix Table 3.

Reclassification Table Comparing 30-Day Mortality Risk Strata for the Combined Comorbidity Score Versus the Romano/Charlson Score and the Combined Comorbidity Score Versus the van Walraven/Elixhauser Score in the Validation Cohort (NJ/PAAD)

| Combined score | Romano/Charlson Score |

van Walraven/Elixhauser Score |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low* | Intermediate* | High* | Total | Low* | Intermediate* | High* | Total | |

| Low* | ||||||||

| No. included | 99,985 | 5,320 | 25 | 105,330 | 100,318 | 4,976 | 36 | 105,330 |

| Deaths | 219 | 44 | 0 | 263 | 219 | 44 | 0 | 263 |

| Non-deaths | 99,766 | 5,276 | 25 | 105,067 | 100,099 | 4,932 | 36 | 105,067 |

| Observed risk, % | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 0.2 |

| Intermediate* | ||||||||

| No. included | 3,721 | 10,246 | 946 | 14,913 | 4,188 | 9,499 | 1,226 | 14,913 |

| Deaths | 72 | 267 | 24 | 363 | 77 | 239 | 47 | 363 |

| Non-deaths | 3,649 | 9,979 | 922 | 14,550 | 4,111 | 9,260 | 1,179 | 14,550 |

| Observed risk, % | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 2.4 |

| High* | ||||||||

| No. included | 47 | 1,371 | 2,194 | 3,612 | 52 | 1,367 | 2,193 | 3,612 |

| Deaths | 2 | 92 | 185 | 279 | 2 | 72 | 205 | 279 |

| Non-deaths | 45 | 1,279 | 2,009 | 3,333 | 50 | 1,295 | 1,988 | 3,333 |

| Observed risk, % | 4.3 | 6.7 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 3.8 | 5.3 | 9.3 | 7.7 |

| Total | ||||||||

| No. included | 103,753 | 16,937 | 3,165 | 123,855 | 104,558 | 15,842 | 3,455 | 123,855 |

| Deaths | 293 | 403 | 209 | 905 | 298 | 355 | 252 | 905 |

| Non-deaths | 103,460 | 16,534 | 2,956 | 122,950 | 104,260 | 15,487 | 3,203 | 122,950 |

| Observed risk, % | 0.3 | 2.4 | 6.6 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 7.3 | ||

Note: light shading indicates an increase in risk category from the component score (i.e. Romano/Charlson or van Walraven) to the combined score and dark shading indicates a decrease in risk category.

Low- (<1%), intermediate- (1% to <4%), and high-risk (≥4%) strata are defined based on predicted probabilities of 1-year mortality among those who died (average predicted probability ~1%) and did not die (~4%) in the first 30 days of the follow-up year.

Table 7.

Measures of Reclassification from the Romano/Charlson Score and the van Walraven/Elixhauser Score to the Combined Score

| From Romano/Charlson Score | From van Walraven/Elixhauser Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Reclassified | NRI, % (p value) | IDI, % (p value) | % Reclassified | NRI, % (p value) | IDI, % (p value) | |

| 30-day mortality | 9.2 | 11.8 (<0.001) | 0.9 (0.16) | 9.6 | 7.2 (<0.001) | 0.6 (0.16) |

| 90-day mortality | 13.5 | 7.3 (<0.001) | 1.3 (0.15) | 13.9 | 6.3 (<0.001) | 1.0 (0.15) |

| 180-day mortality | 13.4 | 5.2 (<0.001) | 1.4 (0.15) | 13.8 | 6.1 (<0.001) | 1.4 (0.15) |

| 1-year mortality | 15.2 | 5.1 (<0.001) | 1.5 (0.43) | 15.2 | 6.3 (<0.001) | 1.8 (0.42) |

NRI, net reclassification index; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement

DISCUSSION

In an independent external validation study, a single numeric comorbidity score that considers conditions in both the Romano implementation of the Charlson Index and the Elixhauser comorbidity classification system performed numerically better in predicting both short- and long-term mortality than either the Romano/Charlson score with Medicare weights or the van Walraven single numeric modification of the Elixhauser measure. Although differences in c-statistics among the 3 comorbidity measures appear small, it has been demonstrated that even slight improvements in the c-statistic for such indices can translate into measurable reductions in confounding bias [2]. Furthermore, this potential benefit comes at no added expense since the combined score is as easy to apply as either of its constituent scores.

Results of the validation study suggest that the difference in discriminative ability between the combined score and its two component scores are larger for mortality with shorter follow-up. Factors measured more recently are likely better predictors of an outcome than factors measured in the distant past, as reflected by the decrease in c-statistic for each score with increasing follow-up time. Thus, as the ability of covariates to predict an outcome decrease, the overall discriminative abilities of different scores based on them become more similar.

Several factors contribute to the difference in performance between the combined comorbidity score and its component scores. While the populations, data, and endpoint of interest are similar to those used to derive the original Medicare weights for the Romano/Charlson score, the combined score incorporates weights derived from more recent data. Improvements in treatment and clinical practice over time modify disease prognosis. For example, the weight for HIV/AIDS from the original Medicare weights was 4 based on data from 1995 and was −1 in the new weighting scheme based on data from 2004. While the prevalence of HIV/AIDS was low in our cohorts, the change in weights may highlight the importance of periodically updating weights to reflect changes in prognosis and also of using comorbidity scores based on weights derived from data that accurately reflect practice and prognosis of a particular population in which a study is to be conducted.

The populations, data source, and endpoint that we used differ markedly from those used to derive the van Walraven/Elixhauser score. For example, van Walraven et al predicted inpatient mortality, whereas we developed the combined score using 1-year mortality. Scores that predict certain endpoints relatively well may poorly predict other outcomes [2]. Additionally, van Walraven et al used hospital data that spanned many years (1996–2008). Accuracy in ascertaining specific comorbidities may differ when using data based on hospital records versus Medicare claims data [24]; additionally, the impact of changes in prognosis over time is discussed above. Finally, van Walraven et al used a different scoring algorithm and did not include age and sex in their models, which may explain the greater variability in weights in their score. Adjusting for age and sex partially adjusts for those conditions that are increasingly common in older age; thus the independent effect of these conditions on mortality is smaller. Whether the combined score can better discriminate inpatient mortality compared to the van Walraven/Elixhauser score remains to be determined. However, an interesting endeavor would be to apply the same approach used here to derive weights for a combined score based on predicting inpatient death using hospital data.

An important point emphasized by several authors [14,17] is that interpretation of weights for individual comorbidities should be done cautiously. In the combined score, hypertension and HIV/AIDS received weights of −1 because the coefficients for these conditions in the multivariable model were slightly less than zero. Obviously, this finding should not lead one to conclude that these conditions prevent 1-year mortality. Rather, presence of diagnosis codes indicating existence of certain conditions may themselves be indicators for other factors that are inversely associated with 1-year mortality or may reflect idiosyncrasies of administrative data. For example, recording of conditions that are themselves not immediately life-threatening (e.g. hypertension) may reflect the general absence of more severe conditions and thus indicate a relatively healthy individual [25]. Such idiosyncrasies of healthcare claims data limit the direct clinical applicability of comorbidity scores derived from them.

Although the combined comorbidity score may be advantageous over existing measures, reliance on comorbidity scores alone may not be a prudent approach to control for confounding in epidemiologic studies when additional methods can be applied [1,2,26]. The extent to which conventional multivariable methods or study-specific disease risk scores or exposure propensity scores improve confounding adjustment beyond comorbidity scores warrants further study. However, it is often the case that conventional methods and study-specific variable reduction methods are impractical. Bias due to over-fitting can result from conventional multivariable methods when relatively few outcomes are available per number of covariates included in the model [27]. Furthermore, studies that involve both few exposures and few outcomes can preclude fitting of models for both propensity scores and disease risk scores [8]. In addition, a single numeric summary of comorbidity facilitates the modeling of interactions of comorbidity with other covariates rather than modeling interactions between covariates and all components of the comorbidity score. Thus, while study-specific considerations of confounding are important, researchers may continue to find value in predefined comorbidity scores.

Nevertheless, several limitations of the combined comorbidity score should be noted. First, we developed and validated the score in an elderly population, using Medicare claims data, and did so to predict 1-year mortality. The sensitivity of the score and its performance relative to other measures when applied to different study populations, data settings, durations of follow-up, and endpoints should be investigated. Additionally, our comparative assessment of the 3 measures is limited in several ways. Some authors have cautioned against over-reliance on the c-statistic to compare the predictive ability of different models, largely because it is insensitive to the addition of important factors in a prediction model [28]. Thus, we also calculated several recently proposed measures of reclassification [23]. Positive values for both the NRI and the IDI indicate that the combined comorbidity score performed better than either the Romano/Charlson score or the van Walraven/Elixhauser score. However, the NRI depends on the cutpoints used to define risk strata; thus, they should be defined a priori and should reflect clinically meaningful thresholds. Furthermore, the properties of these statistics are still being evaluated and the IDI may be less useful than other reclassification measures since small absolute changes in predicted probabilities lead to small values for the IDI [29] even if the changes are large on a relative scale, as can occur when outcomes are rare. In the validation cohort, 7.4% of patients died during the follow-up year and this decreased to 0.7% for 30-day follow-up.

In conclusion, we created a comorbidity score by combining conditions included in both the Charlson Index and the Elixhauser system and derived weights to predict 1-year mortality in a Medicare population aged 65 years and older using data from 2004. Based on external validation, this combined score performed numerically better in discriminating both short- and long-term mortality as compared to either the Romano/Charlson score or the van Walraven/Elixhauser score, based on the c-statistic, but results based on measures of reclassification were mixed. In similar populations and data settings, this score may facilitate better confounding control than existing measures, without any added investigator burden.

WHAT IS NEW.

A comorbidity score combining conditions from the Charlson and Elixhauser measures predicts mortality better than either of the constituent scores

Greater comorbidity summarization with the combined score can lead to better confounding control with no added investigator burden

Comorbidity scores predict outcomes occurring in the near-term better than outcomes occurring over the long-term

Appendix Table 2.

Reclassification Table Comparing 90-Day Mortality Risk Strata for the Combined Comorbidity Score Versus the Romano/Charlson Score and the Combined Comorbidity Score Versus the van Walraven/Elixhauser Score in the Validation Cohort (NJ/PAAD)

| Combined score | Romano/Charlson Score |

van Walraven/Elixhauser Score |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low* | Intermediate* | High* | Total | Low* | Intermediate* | High* | Total | |

| Low* | ||||||||

| No. included | 82,465 | 8,347 | 14 | 90,826 | 83,150 | 7,659 | 17 | 90,826 |

| Deaths | 535 | 142 | 0 | 677 | 543 | 132 | 2 | 677 |

| Non-deaths | 81,930 | 8,205 | 14 | 90,149 | 82,607 | 7,527 | 15 | 90,149 |

| Observed risk, % | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 11.8 | 0.7 |

| Intermediate* | ||||||||

| No. included | 4,692 | 20,512 | 1,645 | 26,849 | 5,528 | 19,439 | 1,882 | 26,849 |

| Deaths | 129 | 928 | 119 | 1,176 | 173 | 852 | 151 | 1,176 |

| Non-deaths | 4,563 | 19,584 | 1,526 | 25,673 | 5,355 | 18,587 | 1,731 | 25,673 |

| Observed risk, % | 2.7 | 4.5 | 7.2 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 4.4 | 8.0 | 4.4 |

| High* | ||||||||

| No. included | 19 | 2,026 | 4,135 | 6,180 | 30 | 2,048 | 4,102 | 6,180 |

| Deaths | 2 | 254 | 672 | 928 | 3 | 236 | 689 | 928 |

| Non-deaths | 17 | 1,772 | 3,463 | 5,252 | 27 | 1,812 | 3,413 | 5,252 |

| Observed risk, % | 10.5 | 12.5 | 16.3 | 15.0 | 10.0 | 11.5 | 16.8 | 15.0 |

| Total | ||||||||

| No. included | 87,176 | 30,885 | 5,794 | 123,855 | 88,708 | 29,146 | 6,001 | 123,855 |

| Deaths | 666 | 1,324 | 791 | 2,781 | 719 | 1,220 | 842 | 2,781 |

| Non-deaths | 86,510 | 29,561 | 5,003 | 121,074 | 87,989 | 27,926 | 5,159 | 121,074 |

| Observed risk, % | 0.8 | 4.3 | 13.7 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 14.0 | ||

Note: light shading indicates an increase in risk category from the component score (i.e. Romano/Charlson or van Walraven) to the combined score and dark shading indicates a decrease in risk category.

Low- (<2%), intermediate- (2% to <8%), and high-risk (≥8%) strata are defined based on predicted probabilities of 1-year mortality among those who died (average predicted probability ~8%) and did not die (~2%) in the first 90 days of the follow-up year.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by research grants from the National Institute on Aging (RO1-AG018833) to Dr. Glynn, and the National Library of Medicine (RO1-LM10213) to Dr. Schneeweiss. Dr. Gagne is supported by a National Institute on Aging training grant (T32-AG000158).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Joshua J. Gagne, Email: jgagne1@partners.org, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 1620 Tremont Street, Suite 3030, Boston, MA 02120, T: 617-278-0930, F: 617-232-8602.

Robert J. Glynn, Email: rglynn@partners.org, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 1620 Tremont Street, Suite 3030, Boston, MA 02120, T: 617-278-0930, F: 617-232-8602.

Jerry Avorn, Email: javorn@partners.org, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 1620 Tremont Street, Suite 3030, Boston, MA 02120, T: 617-278-0930, F: 617-232-8602.

Raisa Levin, Email: levin@boss.bwh.harvard.edu, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 1620 Tremont Street, Suite 3030, Boston, MA 02120, T: 617-278-0930, F: 617-232-8602.

Sebastian Schneeweiss, Email: sschneeweiss@partners.org, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 1620 Tremont Street, Suite 3030, Boston, MA 02120, T: 617-278-0930, F: 617-232-8602.

References

- 1.Schneeweiss S, Maclure M. Use of comorbidity scores for control of confounding in studies using administrative databases. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:891–898. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneeweiss S, Seeger JD, Maclure M, et al. Performance of comorbidity scores to control for confounding in epidemiologic studies using claims data. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:854–864. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.9.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneeweiss S, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, et al. High-dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology. 2009;20:512–522. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a663cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadarette SM, Gagne JJ, Solomon DH, et al. Confounder summary scores when comparing the effects of multiple drug exposures. Pharmacopidemiol and Drug Saf. 2010;19:2–9. doi: 10.1002/pds.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen BB. The prognostic analogue of the propensity score. Biometrika. 2008;95:481–488. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arbogast PG, Ray WA. Use of disease risk scores in pharmacoepidemiologic studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 2009;18:67–80. doi: 10.1177/0962280208092347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. discussion 1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Hoore W, Sicotte C, Tilquin C. Risk adjustment in outcome assessment: The Charlson comorbidity index. Methods Inf Med. 1993;32:382–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghali WA, Hall RE, Rosen AK, et al. Searching for an improved clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00564-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Avorn J, et al. Consistency of performance ranking of comorbidity adjustment scores in Canadian and U.S. utilization data. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:444–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan Y, Birman-Deych E, Radford MJ, et al. Comorbidity indices to predict mortality from Medicare data. Med Care. 2005;43:1073–1077. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182477.29129.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, et al. A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47:626–633. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Avorn J, et al. Improved comorbidity adjustment for predicting mortality in Medicare populations. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1103–1120. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shwartz M, Ash AS. Evaluating risk-adjustment models empirically. In: Iezzoni LI, editor. Risk Adjustment for Measuring Health Care Outcomes. 3. Chicago: Health Administrative Press; 2003. pp. 231–273. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook NR, Buring JE, Ridker PM. The effect of including C-reactive protein in cardiovascular risk prediction models for women. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:21–29. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, D’Agostino RB, Jr, et al. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21:128–138. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook NR, Ridker PM. Advances in measuring the effect of individual predictors of cardiovascular risk: the role of reclassification measures. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:795–802. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klabunde CN, Harlan LC, Warren JL. Data sources for measuring comorbidity: A comparison of hospital records and Medicare claims for cancer patients. Med Care. 2006;44:921–928. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223480.52713.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iezzoni LI, Foley SM, Daley J, et al. Comorbidities, complications, and coding bias. Does the number of diagnosis codes matter in predicting in-hospital mortality? JAMA. 1992;267:2197–2203. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.16.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avorn J, Schneeweiss S. Immunosuppressants, mortality, and risk of cancer (editorial) BMJ. 2009;339:b1645. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:340–349. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007;115:928–935. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.672402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cook NR. Comments on ‘Evaluation the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond’ by M.J. Pencina et al., Statistics in Medicine (DOI: 10.1002/sim.2929) Stat Med. 2008;27:191–195. doi: 10.1002/sim.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]