Abstract

Uterine leiomyomata are common, affecting 70–80% of women between 30 and 50 years of age. Leiomyomata have been reported for a variety of primate species, although prevalence rates and treatments have not been widely reported. The prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment of uterine leiomyomata in the Alamogordo Primate Facility and the Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine and Research were examined. Uterine leiomyomata were diagnosed in 28.4% of chimpanzees with an average age at diagnosis of 30.4±8.0 years. Advanced age (>30 years) was related to an increase in leiomyomata and use of hormonal contraception was related to a decrease in leiomyomata. As the captive chimpanzee population ages, the incidence of leiomyomata among female chimpanzees will likely increase. The introduction of progesterone-based contraception for non-breeding research and zoological chimpanzees may reduce the development of leiomyomata. Finally, all chimpanzee facilities should institute aggressive screening programs and carefully consider treatment plans.

Keywords: fibroid, leiomyoma, tumor, chimpanzee, contraception

Introduction

Uterine leiomyomata are benign fibroid tumors that arise from the smooth-muscle cells of the uterus [Ryan et al., 2005]. Among women, uterine leiomyomata are largely asymptomatic and may occur in as many as 70–80% of women between 30 and 50 years of age [Ryan et al., 2005; Wise et al., 2004]. When symptomatic, the most common complaint is abnormally heavy or extended menstrual bleeding (i.e., menorrhagia) [Ryan et al., 2005]. Rarely, the tumors can also cause severe pelvic pain, uterine prolapse, and may complicate fertility in women [Ryan et al., 2005]. The incidence of leiomyomata increases with age and likelihood is also associated with a younger age at menarche and younger age of first birth [Faerstein et al., 2001a; Ross et al., 1986; Ryan et al., 2005; Wise et al., 2004]. Other risk factors include obesity, nulliparity, and greater than five years since last birth [Faerstein et al., 2001a; Luoto et al., 2000; Ross et al., 1986; Wise et al., 2004]. Traditional management of problematic uterine leiomyomata has been either myomectomy or hysterectomy [Jourdain et al., 1996]. Medical treatments for menorrhagia associated with leiomyomata include either progesterone based contraceptives (i.e., medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo Provera©, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, NY)) or gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists (Lupron Depot©, Abbot Laboratories, IL) [Jourdain et al., 1996]. Progesterones are highly cost-effective and can be used long-term to treat small- or moderate-sized myomas, however gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists are most successful for large myomas and should be used in combination with subsequent myomectomy and/or hysterectomy due to their high cost and the significant risk of side effects [Jourdain et al., 1996].

Uterine leiomyomata have previously been reported in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) [Brown et al., 2009; Seibold & Wolf, 1973; Silva et al., 2006; Toft & MacKenzie, 1975; Young et al., 1996] and other non-human primates [Cianciolo et al., 2007; Cook et al., 2004; Kaspareit et al., 2007; Long et al., 2010; Remick et al., 2009; Rodríguez et al., 2009; Seibold & Wolf, 1973; Stringer et al., 2010; Wilkinson et al., 2008]; however prevalence rates and treatment regimens have not been widely reported. There are no published reports of uterine leiomyomata in wild chimpanzees. Here we report on the prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment of uterine leiomyomata in two chimpanzee populations, the Alamogordo Primate Facility and the Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine and Research (MD Anderson Cancer Center).

Methods

Subjects

Subjects included 97 reproductively-mature female chimpanzees housed at the Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine and Research (KCCMR) in Texas and 98 reproductively-mature female chimpanzees housed at the Alamogordo Primate Facility (APF) in New Mexico, a government-owned, contract-operated facility. No research is conducted at APF. Both facilities are accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC) and this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. At the time of study, females in the population ranged in age from 15.0 to 52.5 years of age (mean=28.4 ± SD 8.7 yrs). All females were maintained in social groups and housed in indoor-outdoor enclosures in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Animals [ILAR, 2010] and all procedures were approved by the facilities' institutional animal care and use committees. This research also adhered to the American Society of Primatologists principles for the ethical treatment of primates. Due to the enactment of the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) breeding moratorium, no purposeful breeding has taken place at either facility since 1998. Of the 195 females, 140 have received non-hormonal contraception (e.g., been primarily housed with a vasectomized male or in all-female groups) for the past 14 years. Fifty-five females have been primarily housed with non-vasectomized males and have received both hormonal contraception (Norplant© (levonorgestrel) implants, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, NJ) and non-hormonal contraception (ParaGard© T380A copper interuterine device, Duramed Pharmaceuticals, OH) for the past 14 years. The average length of prior hormonal contraception for the contracepted population was 4.6 ± SD 1.3 years. The average age of the contracepted population was 30.3 ± SD 10.6 years and the average age of the non-contracepted population was 27.7 ± SD 7.8 years. It should be noted that the use of Norplant at KCCMR was discontinued in 2001 following the FDA recall of Norplant lots sold in 2000. Following the recall, non-hormonal contraception (ParaGard© T380A copper interuterine device, Duramed Pharmaceuticals, OH) was used at KCCMR.

Diagnostic Procedures

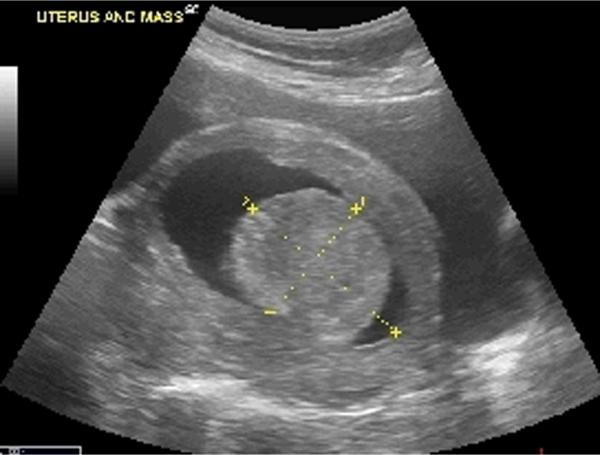

All females with leiomyomata were considered “affected” females. In all cases, original diagnosis of uterine leiomyoma was through physical examination (i.e., palpation) and ultrasound (i.e., abdominal and transvaginal or transrectal) examination confirmation during annual health examinations, while under sedation. This diagnostic method is consistent with leiomyoma diagnostic criteria used in human studies [Faerstein et al., 2001a, 2001b; Hurley, 1998; Ross et al., 1986; Wise et al., 2004]. Uterine leiomyomata appear under ultrasound examination as spherical in shape with well defined borders and a solid hyperchoic texture (Figure 1) [Hurley, 1998]. Adenomyomata can be distinguished from leiomyomata during ultrasound examiniation, as adenomyomata have poorly defined margins and an irregular mottled texture [Hurley, 1998]. Endometrial polyps also have poorly defined margins, compared to leiomyomata, and typically display as thickened heterogeneous areas of endometrium [Bree et al., 2000]. In addition, histopathology was performed by a board-certified veterinary pathologist on the masses of 20% of affected females. Histopathology in all cases indicated a leiomyoma, confirming that the ultrasound diagnostic criteria used to indicate the presence of leiomyomata was accurate. For examination, chimpanzees were sedated with an intra-muscular injection of either ketamine HCl (Ketaset, Fort Dodge Animal Health, IA) at a dosage of approximately 5.0 to 7.5 mg/kg body weight or tiletamine HCI/Zolazepam (Telazol, Fort Dodge Animal Health, IA) at a dosage of 3.0 to 4.0 mg/kg body weight.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound Image of Uterus and Leiomyoma in a Female Chimpanzee. Dimensions of Leiomyoma are Indicated with Dashed Lines.

Statistical Analysis

Age at diagnosis, size of leiomyoma, and any clinical symptoms observed (i.e., abnormal mensing, uterine prolapse, anemia) were recorded. In addition, reproductive history (parity = number of full-term pregnancies) and status of prior hormonal contraception use was determined for each subject. Average age at diagnosis for the affected females was compared to the average age of the female population using a two-tailed, two-sample t-test. The age distribution of affected females was compared to the expected age distribution (based on the female population) using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov one-sample test. This test was chosen due to its high level of power with small sample sizes. To determine any effects of reproductive history or parity, age of females was analyzed using a Generalized Linear Model. Presence of leiomyoma, parity (nulliparous vs. parous), and contraception (hormonal vs. non-hormonal) and their interactions were included as variables in the model. In addition, the age distribution of nulliparous affected females was compared to the expected age distribution of the nulliparous females (based on the female population) using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov one-sample test. To determine any potential effects of hormonal contraception on the incidence of leiomyomata, the prevalence rates of leiomyomata among various groups of females (i.e., hormonal contraception and parity) were compared using a z-ratio test. Significance for all tests was set at 0.05 and all tests were performed using SPSS software.

Results

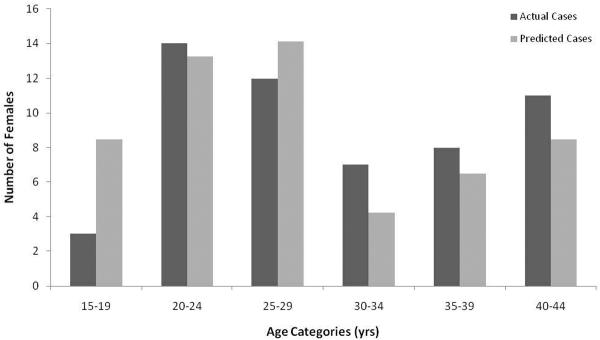

Uterine leiomyomata were confirmed in 55 females (28.2%) ranging in age from 19.3 to 47.3 years (mean=30.4 ± SD 8.0 yrs) at time of diagnosis. The histological picture of these benign leiomyomas was interlacing bundles of smooth muscle and occasionally involved areas of necrosis with vascular embolization and inflammatory cell infiltration. The average age at diagnosis was not significantly different than the average age of the population (28.4 ± SD 8.7 yrs) (Table 1, t=1.52, df=262, p=0.13). The age distribution of affected females was significantly different than the expected age distribution, based on the population (Figure 2, Dmax=0.38, p<0.01), with females over 30 years of age appearing to be at an increased likelihood and females less than 19 years of age appearing to be at a decreased likelihood for the development of leiomyomata.

Table 1.

Summary of mean age at diagnosis (standard deviation) and sample size (N) for affected female chimpanzees compared with entire population of female chimpanzees, and effects of reproductive history and history of hormonal contraception on age at diagnosis in female chimpanzees. Comparisons were tested using Generalized Linear Models with a Tukey post-hoc comparison and significance set at the 0.05 level.

| Age | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | N | Mean (SD) | Minimum | Maximum |

| Affected Females | ||||

| Nulliparous | 32 | 25.4 (6.6)a | 23.1 | 27.7 |

| Parous | 23 | 36.3 (6.6) | 33.4 | 39.1 |

| Population of Females | ||||

| Nulliparous | 131 | 23.6 (6.8)b | 22.4 | 24.7 |

| Parous | 64 | 36.2 (8.2) | 34.2 | 38.2 |

|

| ||||

| Affected Females | ||||

| Contracepted | 9 | 38.0 (7.4)c | 32.3 | 43.7 |

| Non-contracepted | 46 | 28.9 (7.2) | 26.8 | 31.1 |

| Population of Females | ||||

| Contracepted | 55 | 27.7 (7.8) | 26.4 | 29.0 |

| Non-contracepted | 140 | 30.3 (10.6) | 27.4 | 33.2 |

Nulliparous affected females < parous affected females (p<0.05)

Nulliparous population < parous population (p<0.05)

Contracepted affected females > non-contracepted affected females (p<0.05), contracepted affected females > contracepted population (p<0.05)

Figure 2.

Distribution of Age at Leiomyoma Diagnosis for Female Chimpanzees (Actual Cases) Compared to the Expected Age Distribution, Based Upon the Female Chimpanzee Population (Predicted Cases) Using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov One-Sample Test.

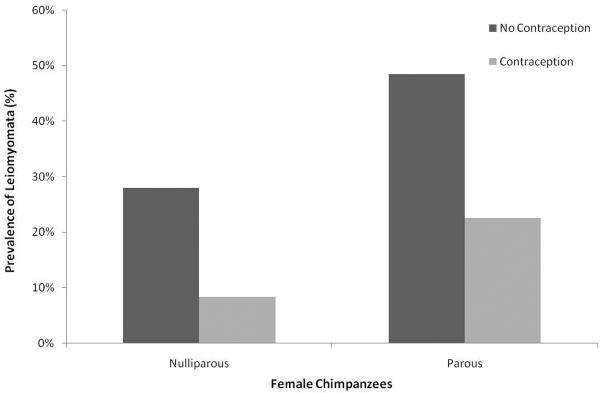

The average age of nulliparous affected females (26.2 ± SD 5.9 yrs) was significantly lower than that of affected parous females (36.3 ± SD 6.6 yrs) (F=61.9, df=2, p<0.001), but not significantly different from nulliparous females in the general population (24.6 ± SD 6.1) (Table 1). The prevalence rate among females with a history of hormonal contraception prior to diagnosis (16.4%, 9/55) was significantly lower, than that of females with no history of hormonal contraception (32.8%, 46/140) (z=−2.3, p=0.02). The average age at diagnosis for affected females with a history of hormonal contraception (38.0 ± SD 7.4) was significantly higher than that of affected females with no history of hormonal contraception (28.9 ± SD 7.2) (Table 1, F=5.2, df=2, p=0.006). The average age at diagnosis for affected females with a history of hormonal contraception (38.0 ± SD 7.4) was also significantly higher than that of females in the general population (Table 1). There was also a significant interaction between parity and hormonal contraception (F=3.9, df=2, p=0.02). The prevalence rate among nulliparous females with a history of hormonal contraception (8.3%, 2/24) was significantly lower than that of nulliparous females without a history of hormonal contraception (28.0%, 30/107) (Figure 3, z=1.8, p=0.04). Similarly, the prevalence rate among parous females with a history of hormonal contraception (22.6%, 7/31) was significantly lower than that of parous females without a history of hormonal contraception (48.5%, 16/33) (Figure 3, z=1.9, p=0.03).

Figure 3.

Prevalence (%) of Leiomyoma in Nulliparous versus Parous Female Chimpanzees, With and Without a History of Hormonal Contraception. Comparison was tested using a Z-Ratio test. Significant results (p<0.05) are indicated with an asterisk (*).

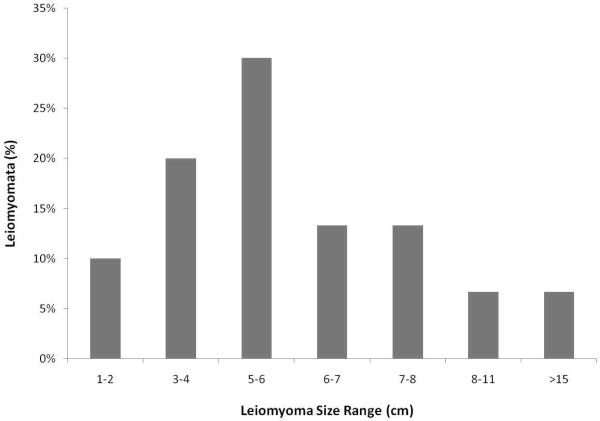

The leiomyomata ranged in size from approximately 1cm in diameter to as large as 25 cm in diameter, with an average size of 5.6 cm in diameter (Figure 4). The vast majority of females (48/55 or 87.2%) were asymptomatic. Typical symptoms included primarily abnormal and/or heavy mensing (6/9), but also included abdominal distension (3/9), edema (1/9), pathology of other pelvic structures (2/9), and uterine prolapse (1/9). Treatments for the symptomatic females included either progesterone-based contraception (i.e., melengesterol acetate implants (MGA, ZooPharm Wildlife Pharmaceuticals, CO), medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo Provera©) or myomectomy in combination with ovariohysterectomy or hysterectomy. In one advanced case gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists (Lupron Depot©) were used prior to myomectomy / ovariohysterectomy.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Size of Leiomyoma (cm) at Diagnosis in Female Chimpanzees (n=55).

Discussion

Uterine leiomyomata have been documented in several primate species and include Old World monkeys, New World monkeys, apes, and Prosimians [Cianciolo et al., 2007; Cook et al., 2004; Kaspareit et al., 2007; Long et al., 2010; Remick et al., 2009; Rodríguez et al., 2009; Seibold & Wolf, 1973; Stringer et al., 2010; Wilkinson et al., 2008]. Leiomyomata have also been sporadically reported as occurring in chimpanzees [Brown et al., 2009; Seibold & Wolf, 1973; Silva et al., 2006; Toft & MacKenzie, 1975; Young et al., 1996]. In a post-mortem study of 52 chimpanzees, uterine leiomyomata were reported in 5.8% of the subjects [Seibold & Wolf, 1973]. A recent examination of neoplasia in chimpanzees, found 42% of neoplasia in females consist of leiomyomata [Brown et al., 2009]. However, neither of these studies was able to determine prevalence rates for leiomyomata among chimpanzee females. Leiomyomata are reported as “common” among nonhuman primates; however, post-mortem examinations reveal incidence rates of less than 1% on average [Cianciolo et al., 2007; Kaspareit et al., 2007; Rodríguez et al., 2009]. The prevalence rate among female chimpanzees in this study was 28.2%, considerably higher than the 5.8% reported previously [Seibold & Wolf, 1973]. The Seibold and Wolf [1973] study was, however a random selection of necropsy results from 52 chimpanzees. The study did not report age or sex ratios of the subjects examined, therefore it is likely the 5.8% rate is a considerable underestimation for this species. The prevalence rate presented in the current study is similar to that reported in the human literature, with estimates of 20–40% of all women presenting with leiomyomata [Ryan et al., 2005]. This rate increases to above 70% when women over the age of 35 are examined [Ryan et al., 2005]. Similarly, the prevalence rate among chimpanzees in this study increased to nearly 40% when only animals 30 years of age and older in the two populations are considered. We hypothesize that leiomyoma development may follow similar patterns in both humans and chimpanzees.

In humans, nulliparity and increased time since last birth increase the risk of leiomyoma development [Faerstein et al., 2001a; Luoto et al., 2000; Ross et al., 1986; Wise et al., 2004]. The average at a leiomyoma diagnosis for nulliparous female chimpanzees was not different from that of nulliparous female chimpanzees within the general population. However, the effects of nulliparity may have been confounded by the long period of time since last birth for the parous females within the population. Due to the NCRR breeding moratorium, the parous females have gone 10–15 years since their last birth. Among women, a period of 10 or more years since last birth is associated with three times the risk of leiomyoma development compared to women who have given birth in the last 1–5 years [Wise et al., 2004]. It is possible that with increasing time since last birth, due to the NCRR breeding moratorium, prevalence rates for uterine leiomyomata in chimpanzees may increase. In humans, there is also an increased risk of leiomyoma associated with obesity [Faerstein et al., 2001a; Ross et al., 1986]. Obesity is an acknowledged problem across captive chimpanzee populations [Lee & Guhad, 2001; Videan et al., 2007] and may play a role in the development of leiomyomata in chimpanzees. However, due to differences in determining obesity across the two facilities this study was unable to properly explore this issue. Additional research is needed on the potential role of body fat and obesity on leiomyoma development in female chimpanzees.

One potential protective practice, which could be employed, is the use of hormonal contraception. Among women, the use of progesterone-based contraception (i.e., medroxyprogesterone acetate [Depo Provera©], levonorgestrel implant [Norplant©]) has been associated with a 40% reduction in risk of leiomyoma development, with decreases in risk associated with increased duration of use [Wise et al., 2004]. A similar pattern of reduction of risk has also been observed for oral contraceptives containing high doses of progesterone [Chiaffarino et al., 1999; Faerstein et al., 2001a; Ross et al., 1986]. In this study, results suggest that the use of progesterone-based contraceptives can reduce and delay development of leiomyomata in female chimpanzees. The use of progesterone-based contraception was associated with both a 50% overall reduction in prevalence rates and delayed development of leiomyoma (Table 1). Nulliparous females may receive more benefit from hormonal contraception than parous females, as the data showed a 70% reduction in prevalence rate for nulliparous females (Figure 3). Among women, non-hormonal intrauterine devices are not associated with either leiomyoma development or prevention [Faerstein et al., 2001b; Luoto et al., 2000; Ross et al., 1986]; however, the newer levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices (i.e., Mirena©, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, NJ) may offer protective effects. Both melengesterol acetate implants (ZooPharm Wildlife Pharmaceuticals, CO) and etonogestrel subdermal implants (Implanon©, Schering Plough Pharmaceuticals, NJ) are long-lasting (up to three years) contraceptive options for female chimpanzees that would likely offer protection from leiomyomata development. Additional research is needed regarding the effects of parity and various types of hormonal contraception on leiomyoma development in female chimpanzees.

Most leiomyomata in women are asymptomatic [Ryan et al., 2005; Wise et al., 2004] and this also appears to be the case for chimpanzees. Progesterone-based contraception (i.e., Depo Provera ©) as treatment for leiomyomata in women is most effective for reducing symptoms (i.e., menorrhagia), but may not be effective for reducing leiomyoma size [Jourdain et al., 1996]. Gonadotropin-releasing agonists are highly effective and can reduce the size of leiomyomata by as much as 70%, however extended use has been linked to loss of bone density [Jourdain et al., 1996]. These medications should only be used for large, symptomatic leiomyomata to reduce tumor size prior to myomectomy and/or hysterectomy. Mifepristone, a synthetic steroid with anti-progesteronic effects, has been shown to significantly reduce the size of leiomyomata in women and may be a better long term therapy compared to gonadotropin-releasing agonists [Jourdain et al., 1996]. Myomectomy has been highly effective in women; however hysterectomy remains the treatment of choice for large or complicated leiomyomata [Jourdain et al., 1996].

As the captive chimpanzee population ages, with little-to-no breeding opportunities it is likely that the incidence of leiomyomata will increase. The results of this study suggest that progesterone-based contraception can have a protective effect and may reduce and delay the development of leiomyomata in chimpanzees. The majority of leiomyomata in chimpanzees may be asymptomatic; however, over time without treatment leiomyomata may increase in size and additional clinical symptoms (i.e., menorrhagia, urinary incontinence/blockage, constipation/bowel obstruction) may develop. It is recommended that aggressive screening programs, including transabdominal ultrasound examination, be instituted for all facilities and zoos housing chimpanzees and careful treatment plans developed for affected individuals.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH contract #NO2-RR-1-2079 and the by University of Texas, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (No. 3 U42 RRO15090 05 S1) within the National Institutes of Health Biomedical Research Program. We thank Dr. Lynn Anderson, Dr. Roger Black, and Dr. Christian Abee for editorial assistance. We are grateful to the African Predator Conservation Research Organization (APCRO) for the donation of Lupron Depot©.

References

- Bree RL, Bowerman RA, Bohm-Velez M, Benson CB, Doubilet PM, DeDreu S, Punch MR. US evalution of the uterus in patients with postmenopausal bleeding: a positive effect of diagnostic decision making. Radiology. 2000;216:260–264. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.1.r00jl37260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Anderson DC, Dick EJ, Jr, Guardado-Mendoza R, Garcia AP, Hubbard GB. Neoplasia in the chimpanzee (Pan spp.) Journal of Medical Primatology. 2009;38:137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2008.00321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, La Vecchia C, Marsico S, Surace M, Ricci E. Use of oral contraceptives and uterine fibroids: results from a case-control study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106:857–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianciolo RE, Butler SD, Eggers JS, Dick EJ, Jr, Leland M, de la Garza M, Brasky KM, Cummins LB, Hubbard GB. Spontaneous neoplasia in the baboon (Papio spp.) Journal of Medical Primatology. 2007;36:61–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2006.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook AL, Rogers TD, Sowers M. Spontaneous uterine leiomyosarcoma in a rhesus macaque. Contemporary Topics in Laboratory Animal Science. 2004;43:47–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faerstein E, Szklo M, Rosenshein NB. Risk factors for uterine leiomyoma: a practice-based case-control study. I. African American heritage, reproductive history, body size, and smoking. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001a;153:1–10. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faerstein E, Szklo M, Rosenshein NB. Risk factors for uterine leiomyoma: a practice-based case-control study. II. Atherogenic risk factors and potential sources of uterine irritation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001b;153:11–19. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley V. Imaging techniques for fibroid detection. Ballière's Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;12:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(98)80062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources . The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academy Press; Washington (DC): 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain O, Descamps P, Abusada N, Ventrillon E, Dallay D, Lansac J, Body G. Treatment of fibromas. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;66:99–107. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(96)02416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspareit J, Friderichs-Gromoll S, Buse E, Habermann G. Spontaneous neoplasms observed in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) during a 15-year period. Experiments in Toxicology and Pathology. 2007;59:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DR, Guhad PA. Chimpanzee health care and medicine program. In: Brent L, editor. Special Topics in Primatology: The Care and Management of Captive ChimpanzeesSan. American Society of Primatologists; Antonio: 2001. pp. 63–117. [Google Scholar]

- Long CT, Luong RH, McKeon GP, Albertelli MA. Uterine leiomyoma in a Guyanese squirrel monkey (Saimiri scuireus scuireus) Journal of the American Association of Laboratory Animal Science. 2010;49:226–230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoto R, Kaprio J, Rutanen E-M, Taipale P, Perola M, Koskenvuo M. Heritability and risk factors of uterine fibroids – the Finnish Twin Cohort Study. Maturitas. 2000;37:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remick AK, Van Wettere AJ, Williams CV. Neoplasia in prosimians: case series from a captive prosimian population and literature review. Veterinary Pathology. 2009;46:746–772. doi: 10.1354/vp.08-VP-0154-R-FL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez P, Flores L, Fariñas F, Bakker J. First report of a uterine leiomyoma in a common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus): statistical study confirms rarity of spontaneous neoplasms. Laboratory Primate Newsletter. 2009;48(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ross RK, Pike MC, Vessey MP, Bull D, Yeates D, Casagrande JT. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research and Education) 1986;293:359–362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6543.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;48:312–324. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000159538.27221.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibold HR, Wolf RH. Neoplasms and proliferative lesions in 1065 nonhuman primate necropsies. Laboratory Animal Science. 1973;23:533–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AE, Cassali GD, Nascimento EF, Coradini MA, Serakides R. Uterine leiomyoma in chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia. 2006;58:129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer EM, DeVoe RS, Valea F, Toma S, Mulvaney G, Pruitt A, Troan B, Loomis MR. Medical and surgical management of reproductive neoplasia in two western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) Journal of Medical Primatology. 2010;39:328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2010.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toft JD, MacKenzie WF. Endometrial stromal tumor in a chimpanzee. Veterinary Pathology. 1975;12:32–36. doi: 10.1177/030098587501200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videan EN, Fritz J, Murphy J. Development of guidelines for assessing obesity in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Zoo Biology. 2007;26:93–104. doi: 10.1002/zoo.20122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson M, Walters S, Smith T, Wilkinson A. Reproductive abnormalities in aged female Macaca fascicularis. Journal of Medical Primatology. 2008;37:88–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2007.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise LA, Palmer JR, Harlow BL, Spiegelman D, Stewart EA, Adams-Campbell LL, Rosenberg L. Reproductive factors, hormonal contraception, and risk of uterine leiomyomata in African-American women: a prospective study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159:113–23. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LA, Lung NP, Isaza R, Heard DJ. Anemia associated with lead intoxication and uterine leiomyoma in a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 1996;27:96–100. [Google Scholar]