Abstract

Even though oncolytic adenovirus (Ad) has been highlighted in the field of cancer gene therapy, transductional targeting and immune privilege still remain difficult challenges. The recent reports have noted the increasing tendency of adenoviral surface shielding with polymer to overcome the limits of its practical application. We previously reported the potential of the biodegradable polymer, poly(CBA-DAH) (CD) as a promising candidate for efficient gene delivery. To endow the selective-targeting moiety of tumor vasculature to CD, cRGDfC well-known as a ligand for cell-surface integrins on tumor endothelium was conjugated to CD using hetero-bifunctional cross-linker SM(PEG)n. The cytopathic effects of oncolytic Ad coated with the polymers were much more enhanced dose-dependently when compared with that of naked Ad in cancer cells selectively. Above all, the most potent oncolytic effect was assessed with the treatment of Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD in all cancer cells. The enhanced cytopathic effect of Ad/RGD-conjugated polymer was specifically inhibited by blocking antibodies to integrins, but not by blocking antibody to CAR. HT1080 cells treated with Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD showed strong induction of apoptosis and suppression of IL-8 and VEGF expression as well. These results suggest that RGD-conjugated bioreducible polymer might be used to deliver oncolytic Ad safely and efficiently for tumor therapy.

Introduction

The selective and potent cancer-cell killing property of oncolytic adenoviruses (Ads) has attracted considerable attention in the field of cancer gene therapy due to their conditional replication and progeny viral production to facilitate the lysis of cancer cells while sparing normal cells [1,2]. Moreover, reproduced virions are released and spread to neighbored tumor cells. Since adenoviral E1A and E1B proteins modulate host cell signaling pathways through directly binding with tumor suppressor proteins, the replication of Ad can be selectively allowed by the mutations or paucity of the adenoviral E1A or E1B gene in cancer cells compared with normal cells [3,4]. On the basis of this concept, many promising oncolytic Ad vectors have been developed with the capability of conditional replication in cancer cells harboring the mutations of tumor suppressor genes [3–6]. Although the p53 protein is functional in some cancer cells, the loss of p14ARF can also reduce the ability of p53 to block the adenoviral replication in some p53 wild-type cancer cells [7]. Thus, oncolytic Ad has preferred characteristics for cancer therapy: effective and selective antitumoral activity, amplified transgene expression by Ad replication and additionally therapeutic efficacy by diffusion of progeny viruses.

While Ad as a gene delivery vector has many attractive advantages: concentration with high titers; broad range of both dividing and non-dividing cells; large capacity for insertional foreign DNA; no integration into the host cell chromosomes and limited mutagenesis rate with low genotoxicity, its clinical applications have been strictly limited to local injection against primary tumors [1,2,8], because Ad can cause the acute accumulation in the liver followed by liver-toxicity and be cleared quickly in vivo by neutralizing antibodies (Abs) to Ad commonly found within the human body [9]. As an alternative way to overcome the limits of Ad vectors for clinical application, combinatorial technologies using both viral and non-viral gene delivery systems have been introduced with rapidly increasing popularity. Non-viral vector, polymer has been known to reduce immunogenicity and increase stability of viral vector [10,11].

Cationic materials (cationic liposomes, peptides, polymers etc. as non-viral carriers) can form stable polyelectrolyte complexes with Ad particle via electrostatic interactions between the positively charged polycations and the negatively charged surface of Ad particle that could readily bind to and enter into the cell [12,13]. In general, Ad infection is initiated by binding of the fiber knob to the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) followed by a lower affinity interaction between the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide domain in the penton base and cellular integrins such as αvβ3, αvβ5 [14,15]. Finally the receptor mediated endocytosis occurs within a clathrin-coated endosome via integrins [16]. The binding between fiber of Ad and CAR has been found as an important rate and limiting step for entering the cell [14,17]. Several interesting studies have demonstrated that cationic materials significantly enhance Ad-mediated gene transfer to cancer cells lacking CAR which is correlated with the development of tumor malignancy [12,13,18].

However, significant toxicity of the representative cationic polymers, such as poly(ethylenimine) (PEI), poly(L-lysine) (PLL) and poly(aminoamine) dendrimers, has been found due to the poor biocompatibility and non-degradability [19]. Even newly generated hydrolyzable polymers like poly(β-amino ester)s [20], poly(amino ester)s [21] having less cytotoxicity, showed only modestly increased transfection efficiency. To fulfill with low cytotoxicity and high efficiency of gene transfection, the new biodegradable poly(cystaminebisacrylamide-diaminohexane) [poly(CBA-DAH)] (CD) was introduced as polymer carrier for gene delivery [22]. The transfection efficiency and rate of cellular uptake of the CD/DNA complex were much more induced than that of branched poly(ethylenimine) (bPEI, 25 kDa) in primary myoblasts. Furthermore, the CD polymer would alleviate cytotoxicity because they are biodegraded to non-toxic small molecules upon exposure to the reductive environment of the cytoplasm through the cleavage of disulfide bonds by glutathione and are no longer harmful [22,23].

A number of target epitopes overexpressed on activated endothelial cells have been identified, including integrins, E-selectin and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors [24]. Among them, a cyclic RGD peptide has been widely investigated as an active targeting moiety in anti-angiogenic gene therapy for cancer [25–28]. This ligand can specifically recognize and bind with αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin receptors, which is an important biomarker overexpressed in sprouting tumor vessels and most tumor cells.

In an attempt to take advantage of each system’s strengths, actively targeting RGD peptide were conjugated to the bioreducible CD polymer connected with polyethylene glycol (PEG) (CD-PEG-RGD). And cancer cell-specifically replicating oncolytic Ad (Ad-ΔB7-U6shIL8) expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against interleukin-8 (IL-8) mRNA, a potent pro-angiogenic factor, was physically complexed with the CD-PEG-RGD polymers [29]. This oncolytic Ad, which has E1A mutations and E1B deletion for cancer-selective replication, was previously shown to have the effects on anti-angiogenesis and tumor growth inhibition by blocking tumor cell migration, invasion, expressions of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and VEGF and by suppressing the progression of human cancer xenografts (A549 and Hep3B) in mice [29]. In this study, the cancer cell-specific killing effects, induction of apoptosis and suppression of IL-8 and VEGF expression were investigated using the oncolytic Ad coated with the RGD-conjugated bioreducible CD with the different size of PEG linker in human cancer cells. To verify that the RGD-conjugated polymer could endow the oncolytic Ad with the characteristics of not binding to CAR, but of binding to integrins exclusively, competition assay using CAR or integrins Abs was accomplished to prove the selective cancer cell-killing effect of oncolytic Ad coated with the RGD-targeted bioreducible polymer.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines

Human cancer (A549 (lung carcinoma), HT1080 (fibrosarcoma) and MCF7 (breast adenocarcinoma)), human normal fibroblast (BJ) and human embryonic kidney 293 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and maintained in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s Media (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. The other human normal fibroblast cell line (HDF) was purchased from the Gelantins (Telesis Court. San Diego, CA) and maintained with the same condition as mentioned above.

2.2. Oncolytic Ad

The generation of the replication-competent Ad (Ad-ΔB7-U6shIL8) mutated in E1A and deleted in E1B regions was characterized as previously described [27]. Ad-ΔB7-U6shIL8 was amplified in 293 cells and purified by CsCl density purification. The purified virus was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) plus 4% sucrose and finally stored at −80°C. The number of viral particles was calculated from the measurements of optical density at 260 nm, where 1 absorbency unit is equivalent to 1.1 × 1012 viral particles per milliliter [30].

2.3. Synthesis of the polymers

The procedure for synthesizing CD polymer was introduced in our previous work [22]. The conjugation of cyclic Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Phe-Cys (cRGDfC) peptides (Peptides international Inc., Louisville, Kentucky) to CD was performed using hetero-bifunctional cross linker SM(PEG500) or SM(PEG2000) (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The CD was activated with 5 molar equivalents of SM(PEG500) or SM(PEG2000) per 10 DAH groups in anhydrous dimethyl formamide (DMF) for 4 h at room temperature and purified with a desalting column. Cysteine-terminated cRGDfC (2 eq.) was added to the activated polymer and the reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h under the dark condition at room temperature. The crude mixture was precipitated with cold ether and purified by extensive dialysis against ultra pure water. The conjugation of cRGDfC linked with PEG500 or PEG2000 was confirmed by 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O).

2.4. Expression levels of CAR and integrins in human cancer cells

The expression levels of CAR and integrins (αvβ3 and αvβ5) on the surface of human cancer cells (A549, HT1080 or MCF7) were determined by flow cytometry. Each type of cell was released by trypsin-EDTA and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (PBS/BSA). Three × 105 cells for were incubated with respective primary Ab (1:100) (ab9891 for CAR: Abcam; MAB1976 for αvβ3 and MAB1961 for αvβ5: Chemicon) at 4°C for 1 h and washed two times with PBS/BSA, followed by incubation with the secondary Ab (1:1,000) (Alexa647-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG: Molecular probe) at 4°C for 40 min. After washing two times with PBS/BSA, the stained cells were resuspended in 0.5 mL of PBS for analysis. Each type of cell stained with only secondary Ab was utilized as a negative control. Flow cytometry was performed by using BD FACscan analyzer (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA) with Cell Quest software (Becton-Dickinson). Approximately ten thousand cell events were counted for each sample.

2.5. Average particle size of naked Ad or Ad/polymer complex

The average size of naked Ad or Ad coated with each polymer (Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD, Ad/CDPEG2000-RGD) was determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using Zetasizer 3000HS (Malvern Instrument Inc., Worcestershire, UK) with a He-Ne Laser beam (633 nm, fixed scattering angle of 90°) at room temperature. Ad particles (1 × 109) diluted in PBS were gently added to each polymer solution (2.5 × 105 polymer molecules/Ad particle) diluted in PBS for 20 min incubation. After that, PBS was added to final volume of 2 mL right before the measurement. The obtained sizes were presented as the average values of 5 runs.

2.6. Preparation and treatment of CD derivates and Ad complex

Respective complex of polymers (CD, CD-PEG500-RGD, CD-PEG2000-RGD or CD-PEG500) and Ad particles was prepared by pre-diluting the polymer components and Ad components using serum-free DMEM. The desired Ad particles were added gently to the solution of the desired polymers and mixed by tapping slightly. The complex samples were allowed to stand at room temperature for 20 min before treating to cells in culture medium without FBS. After 4 h for incubation, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS.

2.7. Cytopathic effect assay

To evaluate the cancer-specific killing effects of naked Ad or Ad coated with polymers (Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD), human cancer (A549, HT1080 or MCF7) or normal (HDF or BJ) cells were plated onto 24-well plates at about 50 to 60% confluence. After 24 h, cells were treated with naked Ad or Ad/polymer complex at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20 (A549), 50 (HDF or BJ), 100 (HT1080) or 200 (MCF7) with corresponding polymer molecules (3.1, 6.3, 12.5, 25, 50 or 100 × 104 polymer molecules per Ad particle) for 4 h, then each medium was replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS. After incubation for 2 days (A549, HT1080 and MCF7) or 4 days (HDF and BJ) allowing viral replication and cell-lysis, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 400 µg/mL of MTT. Subsequently, the cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 4 h under dark condition. The MTT solution was removed and replaced with 500 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to solubilize the produced formazan crystals. The absorbency was determined using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad 680, Hercules, CA) at 540 nm. The cell viability was expressed as the percentage of untreated cells as a negative control. Each experiment was repeated three times.

2.8. Competition assay

HT1080 cells were plated onto 24-well plate at a number of 2 × 104 per well. After 24 h, cells were incubated in FBS-free DMEM with CAR Ab (ab9891) (50 µg/mL) or integrin Abs (αvβ3 (MAB1976) and αvβ5 (MAB1961)) (30 µg/mL of each Ab) at 4°C for 1 h. Naked Ad or Ad/polymer complex (Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD) at an MOI of 100 (2.5 × 105 polymer molecules per Ad particle) was added to the medium and incubated at 37°C for 1 h, followed by the medium was washed 3 times with PBS and replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS. After incubation for 2 days, each cell-viability was measured by MTT assay.

2.9. Selective targeting via RGD peptide

We synthesized CD polymer with PEG500 cross linker, without RGD targeting peptides (CD-PEG500). To prove whether the infection pathway of Ad coated with CD-PEG500-RGD is selectively mediated by the interaction between the RGD peptide and integrins on the surface of target cells, HT1080 cells were treated with Abs (MAB1976 and MAB1961) against integrins (αvβ3 and αvβ5) (30 µg/mL of each Ab) at 4°C for 1 h. Naked Ad or Ad/polymer complex (Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500 or Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD) at an MOI of 100 (2.5 × 105 polymer molecules per Ad particle) was added to the medium and incubated at 37°C for 1 h, followed by the medium was washed 3 times with PBS and replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS. Cell killing effects were determined by MTT assay after incubation for 2 days.

2.10. Induction of Apoptosis

HT1080 cells were treated with naked Ad or Ad coated with respective polymer (Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD, Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD) at an MOI of 50 (2.5 × 105 polymer molecules per Ad particle) for 4 h, and incubated for 2 days. The treated cells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA. The collected cells were resuspended with 500 µL of the binding buffer including 5 µL of Annexin V-FITC and 5 µL of propidium iodide (PI) provided with the Annexin V FITC kit (MBL, Woburn, MA). Samples were then analyzed by a BD FACscan analyzer (Becton Dickinson). The cells treated with 1 mM of CoCl2 for 18 h were served as an experimental positive control.

2.11. IL-8 or VEGF expression by ELISA

Human cancer (HT1080 and MCF7) or normal (HDF) cells were seeded on 24-well plate with a number of 2 × 104 cells (HT1080 or MCF7) or of 3 × 104 cells (HDF) per well. After 24 h, the plated cells were treated with naked Ad, Ad coated with each polymer (Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD, Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD) (2.5 × 105 polymer molecules/Ad particle) at an MOI of 100, 200 or 50 (HT1080, MCF7 or HDF, respectively) in serum-free DMEM. Four h post-treatment, the medium was replaced with 500 µL of DMEM containing 5% FBS, followed by incubation for 2 days (HT1080 and MCF7) or 4 days (HDF). Each conditioned medium was harvested and the expression level of IL-8 or VEGF was measured by human IL-8 (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN 55413) or VEGF (R&D Systems, Inc.) ELISA assay kit. ELISA results were normalized relative to the total protein concentration in each sample and calculated as pictograms per milliliter of total protein.

2.12. Statistical analysis

The data were express as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical comparison was made using Stat View software (Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA) and Mann-Whitney test (nonparametric method). The criterion for statistical significance was considered statistically significant when p values were less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Expression levels of CAR and integrins on human cancer cells

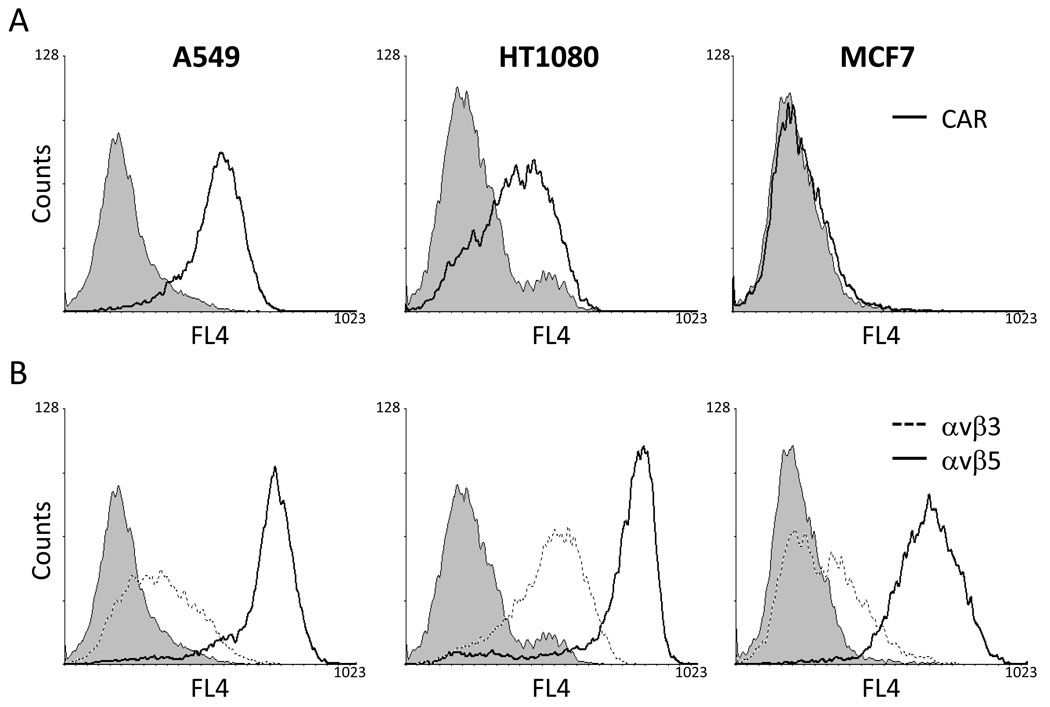

To investigate the variability in expression level of CAR or integrin (αvβ3 or αvβ5) subunit on the surface of the cell types used, we measured each expression level of CAR or integrins on the outer-membrane of human cancer cells (A549, HT1080 and MCF7) by flow cytometry (Fig. 1). While the CAR expression was highly detected on A549 cells, weak- or lack-expression of CAR proteins was observed on HT1080 or MCF7 cells, respectively. All three cell types expressed αvβ5 integrin prominently; the expression level of αvβ3 were measured with much more increased levels on HT1080 cells as compared with that of A549 or MCF7 cells. The susceptibility of cell types to Ad infection varies considerably that is highly correlated the expression of CAR and integrin receptors such as αvβ3 and αvβ5 [15,31]. As representatives, A549 expressing high levels of CAR and integrins on the cell-surface can be noticeably transduced even with small amount of Ad expressing green fluorescent proteins. In contrast with in A549 cell type, in MCF7 cells lacking of CAR, Ad can also infect to the cells through the interactions between the Ad pentons and cell-surface integrins, although much higher amount of Ad is required for appropriate infectivity (data not shown). This result demonstrated that we selected the pertinent cancer cells showing variable expression-levels of CAR or high expression-levels of integrins (αvβ3 or αvβ5) for further experiments to compare cytopathic effect in each cell type.

Fig. 1.

The expression of CAR or integrins (αvβ3 and αvβ5) on the surface of human cancer cells (A549, HT1080 or MCF7). The status of CAR or integrins on each cell type was determined using flow cytometry. Cells were stained with ab9891 (CAR), MAB1976 (αvβ3) or MAB1961 (αvβ5) Ab followed by treatment of secondary Ab, goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa 647. (A) Flow cytometry of CAR expression level on the cell types. The solid line histograms represent anti CAR labeling. (B) Flow cytometry of integrins (αvβ3 and αvβ5) expression levels on the cells. The broken line histograms represent anti-αvβ3 integrin labeling and the solid line histograms represent anti-αvβ5 integrin labeling. Each filled histogram represents only secondary Ab labeling as a negative control.

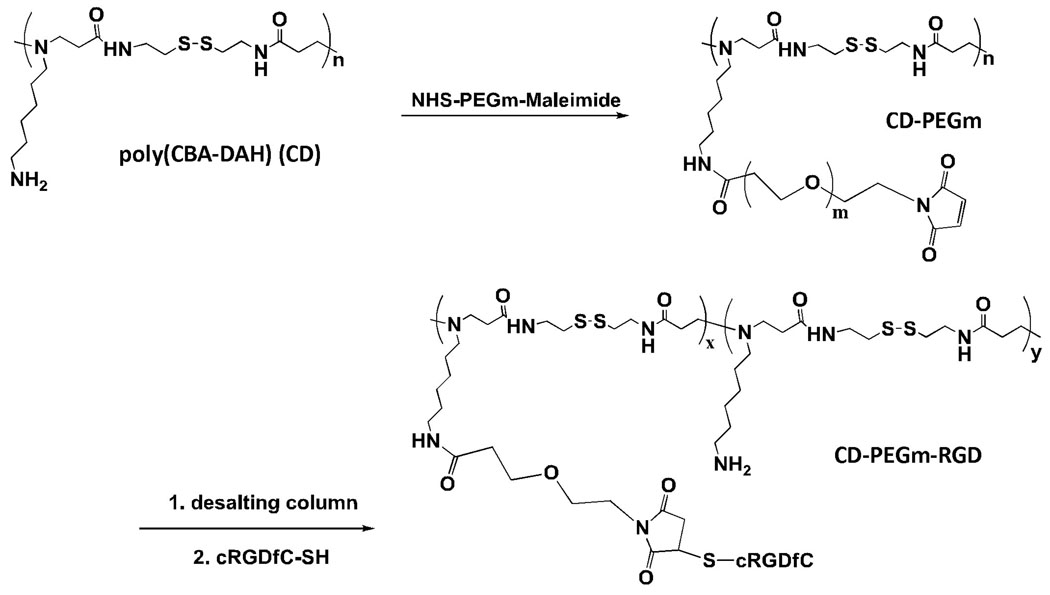

3.2. Synthesis and characterization of RGD-conjugated bioreducible polymers

The bioreducible polymer, CD, showed the enhanced intracellular delivery with significantly less cytotoxicity compared to the PEI and effective localization to the cytoplasm [22,23,32,33] due to its biodegradability. To further improve the enhanced and targeted transduction efficacy of the bioreducible polymer (CD), cyclic RGD targeting peptide ligand (cRGDfC), which can selectively recognize both αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin receptors known to be over-expressed in endothelial cells of tumor capillaries and neointimal tissues, was installed on the CD polymer using hetero-bifunctional cross linker SM(PEG500) or SM(PEG2000) (Fig. 2). For controlling the further in vivo pharmacokinetics of Ad coated with the bioreducible polymer, different size of PEG (PEG500 or PEG2000) was introduced between CD and cRGDfC. The average size of naked Ad or Ad coated with the polymer (Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD) was assessed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Zetasizer 3000HS. As shown in Table. 1, while the average size of naked Ad was about 109.0 nm, size distribution peaks for Ad after coating with each polymer (CD, CD-PEG500-RGD or CD-PEG2000-RGD) were shown at approximately 246.6, 267.6 or 312.2 nm, respectively. This result describes that the positively charged RGD-conjugated polymers can physically form complex with the negatively charged surface of Ad.

Fig. 2.

Synthetic scheme of RGD-conjugated bioreducible polymer. Cyclic RGDfC (cRGDfC) was conjugated to poly(CBA-DAH) (CD) using hetero-bifunctional cross linker, NHS-PEGm-Maleimide. The PEGm represents PEG500 or PEG2000 with different size.

Table 1.

The average size distributions of polymer-coated Ad complexes by DLS

| Average diameter (nm) | |

|---|---|

| Naked Ad | 109.0 ± 16.4 |

| Ad/CD | 246.6 ± 44.1 |

| Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD | 267.6 ± 54.8 |

| Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD | 312.2 ± 56.5 |

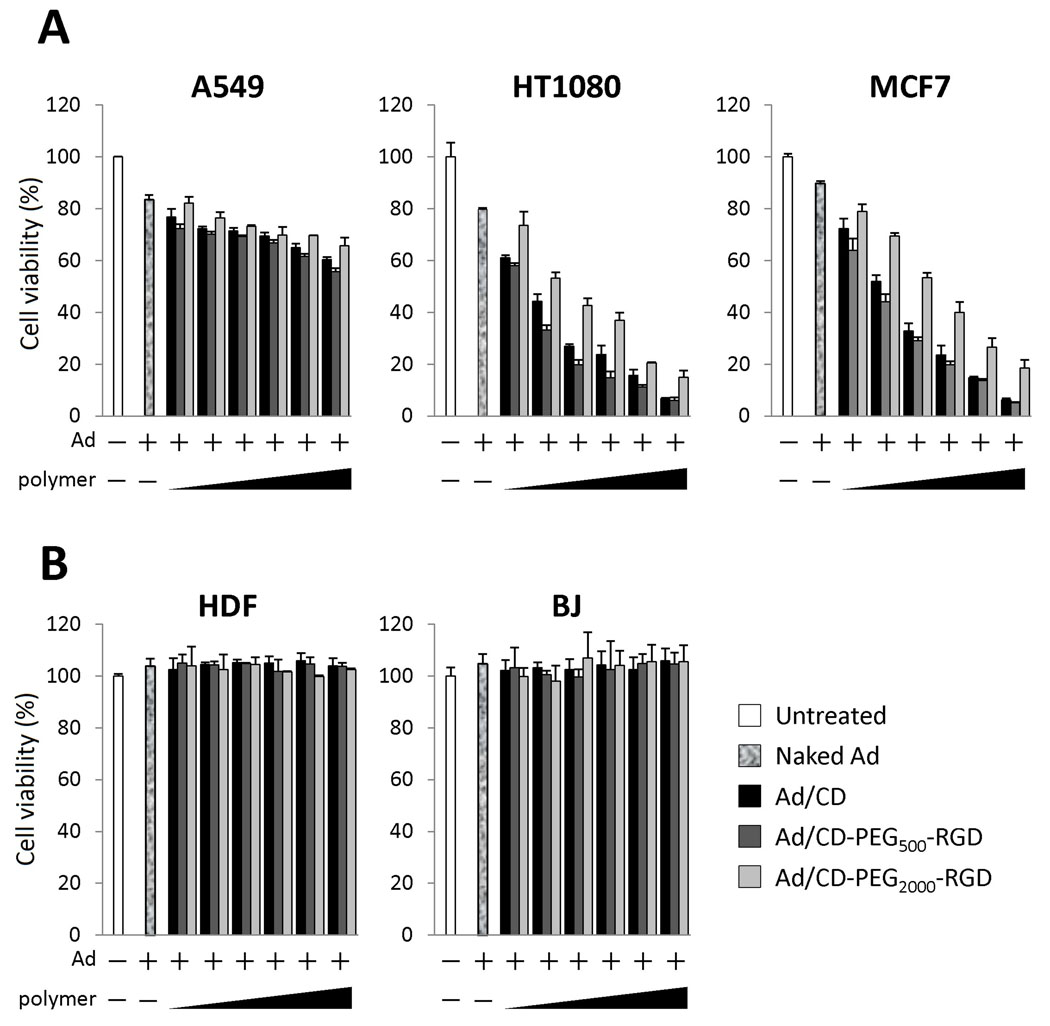

3.3. Enhanced oncolytic effects of Ad coated with polymers

While p14ARF plays an important role as a negative regulator of MDM2 by interfering with MDM2-mediated shuttling and degradation of p53 [34], mutation or null of p14ARF gene locus have been frequently found in many cancer cells. By taking advantage of an unguarded system, replication of E1-Bdeleted oncolytic Ad can be facilitated in many cancer cells, even though p53 gene is wild-type status [7,35]. Ad-ΔB7-U6shIL8 was technically designed to replicate in and kill the cancer cells harboring the p53-defective pathway. We selected all cancer cell types (A549, HT1080 and MCF7) having mutations or null of p14ARF gene locus that these cells could allow a proper replication of the oncolytic Ad. Thus, we demonstrated that the oncolytic Ad, Ad-ΔB7-U6shIL8, can selectively replicate in and ultimately kill human cancer cells [29]. In order to investigate whether the cytopathic effect of the oncolytic Ad (Ad-ΔB7-U6shIL8) by coating with the polymer (CD, CD-PEG500-RGD or CD-PEG2000-RGD) could be enhanced, Ad was physically complexed with the bioreducible polymers with different molar ratio (3.1, 6.3, 12.5, 25, 50 or 100 × 104 polymer molecules per Ad particle) and treated to human cancer (A549, HT1080 or MCF7) (Fig. 3A) or normal (HDF or BJ) (Fig. 3B) cells to compare the oncolytic effects. The cancer cells treated with naked Ad were killed with the percentages of 16.5% (20 MOI for A549), 20.2% (100 MOI for HT1080) and 10.4% (200 MOI for MCF7), respectively. However, the killing effects of Ad/polymer in HT1080 and MCF7 were dramatically enhanced dose-dependently, while A549 cells treated with each Ad/polymer complex were shown the mild cytopathic effect. Since A549 is well-known cell type for Ad infection due to abundant CAR and integrins (Fig. 1), naked Ad can show sufficient infection ratio by itself in A549. Above all, the Ad coated with CD-PEG500-RGD induced the strongest killing effects on all cancer cell types. In contrast with cancer cells, human normal cells treated with naked Ad or even with Ad/polymer were not killed although incubation time was extended 2 more days. As near as we could guess, the replication of introduced oncolytic Ad genome might be restricted by the functional defense mechanism in normal cells, even though infection yield could be much enhanced by coating of Ad with the polymers to normal cells. This result is demonstrating that infection efficiency of oncolytic Ad can be noticeably enhanced by cloaking with polymers. Especially, in HT1080 or MCF7 cells showing weak- or lack-expression of CAR, infection efficiency of oncolytic Ad by coating with the polymers was significantly increased when compared with that of naked Ad, while the slightly increased infection efficiency of Ad/polymer was shown in A549 cells expressing high level of CAR and integrins.

Fig. 3.

The cytopathic effect of naked Ad, Ad coated with CD (Ad/CD), CD-PEG500-RGD (Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD) or CD-PEG2000-RGD (Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD) in human cancer (A549, HT1080 or MCF7) (A) or normal (HDF or BJ) (B) cells. Each cell type was treated with naked Ad, Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD at an MOI of 20 (A549), 50 (HDF or BJ), 100 (HT1080) or 200 (MCF7) with corresponding polymer molecules (3.1, 6.3, 12.5, 25, 50 or 100 × 104 polymer molecules per Ad particle). Cell viability was measured by MTT assay.

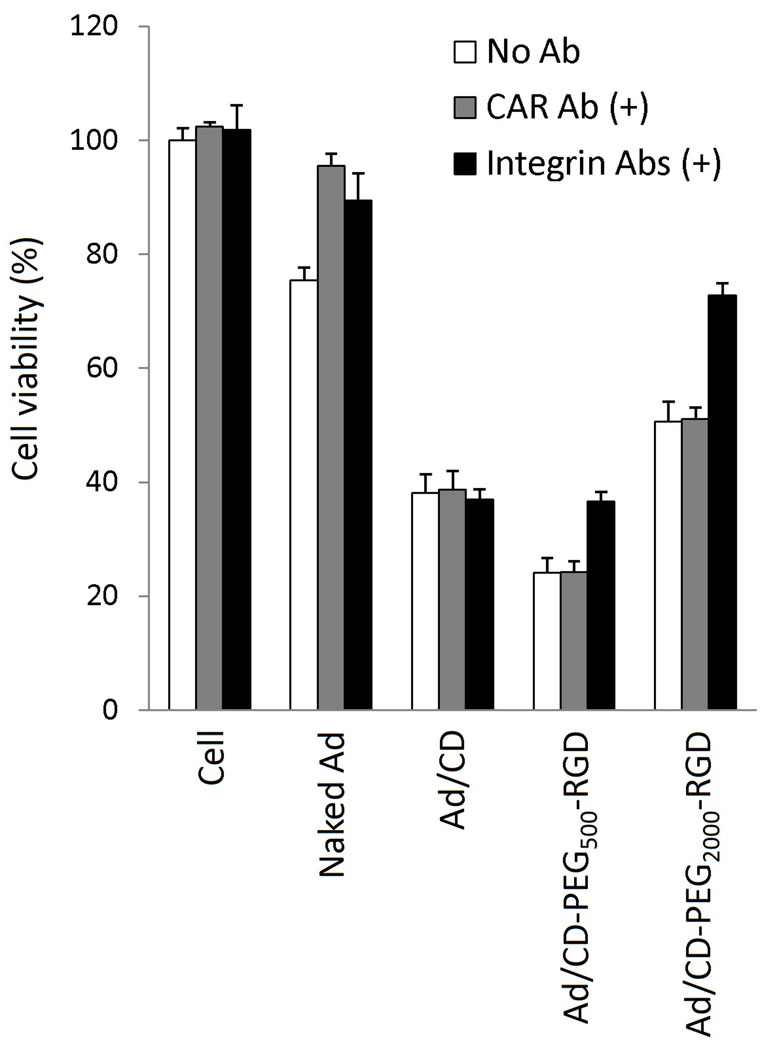

3.4. Alternative infection pathway of Ad/RGD-conjugated polymers

We demonstrated whether the RGD-conjugated polymers coated on the surface of Ad could block the general infection pathway of naked Ad and create alternative infection pathway through by binding of RGD targeting peptide with integrins on target cells. To prove alternative infection pathway of Ad/RGD-conjugated polymers through binding with integrins, and not with CAR, competition assay using CAR Ab or integrin (αvβ3 and αvβ5) Abs was investigated in HT1080 cells expressing both CAR and integrins (Fig. 4). While the population of killed cells treated with naked oncolytic Ad was decreased from 24.6% to 4.5% by blocking with CAR Ab, the cells treated with respective Ad/polymer complex were not shown any inhibitory effects by blocking with CAR Ab when compared with the Ab-untreated cells. By blocking with integrin Abs, the population of killed cells by naked Ad was also decreased to 10.6%. However, the killing effect of Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD was reduced from 75.9% to 63.4% or 49.4% to 27.2% by blocking with integrin Abs. There was no significant change of killing effect in the cells treated with Ad/CD by blocking with CAR Ab or integrin Abs. In summary, both of CAR and integrins are clearly required for sufficient infection of Ad to target cells [15,29], while only integrins are needed for Ad/RGD-conjugated polymer complex to show enough infection-efficiency. This result suggests that the RGD-conjugated polymers could deliver Ad to the cells expressing integrins specifically, which is not correlated with whether the expression of CAR status.

Fig. 4.

Competition assay using CAR Ab or integrin (αvβ3 and αvβ5) Abs. After HT1080 cells were incubated with CAR Ab or integrin Abs at 4°C for 1 h, Naked Ad, Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD was added to the medium and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Each cytopathic effect was measured by MTT assay.

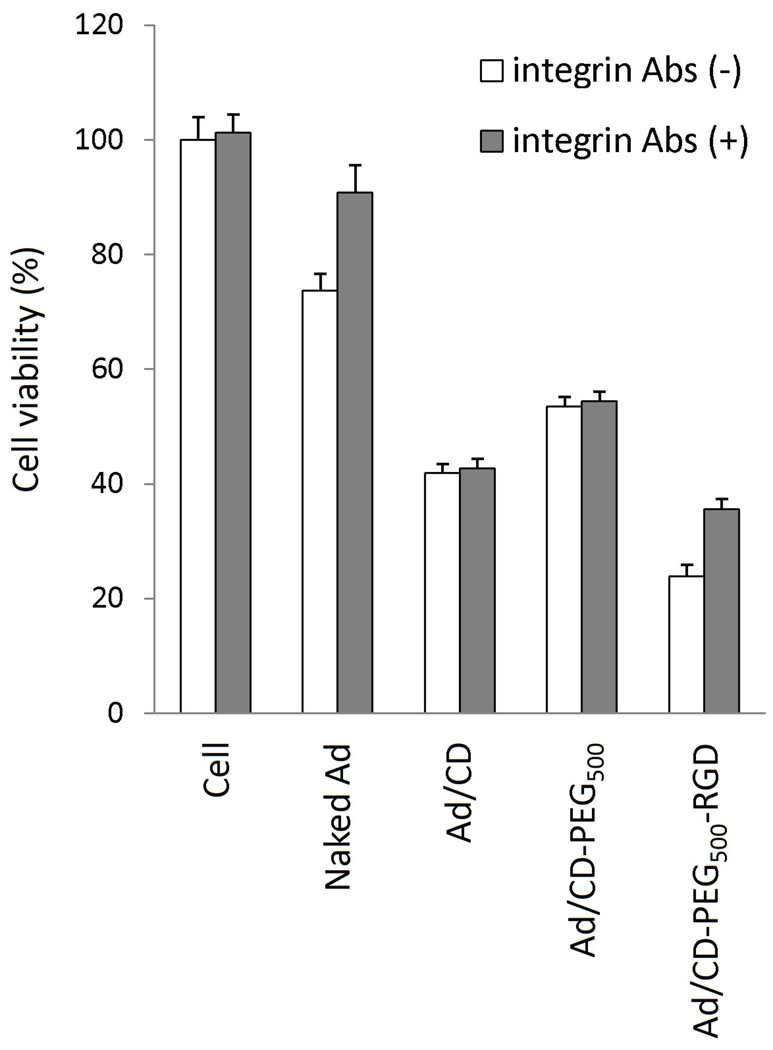

3.5. Active targeting of CD-PEG500-RGD via RGD tumor homing peptide

To determine the selective transduction pathway of RGD-conjugated polymers depending on the presence of RGD-targeting peptide, we synthesized the CD-PEG500 without RGD peptide and compared cytopathic effect of each Ad/polymer complex in HT1080 cells expressing high levels of integrins (Fig. 5). As we expected, the percentage of killed cell-population treated with naked Ad or Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD was significantly reduced from 26.3% to 9.2% or 76.2% to 64.4% by blocking with integrin Abs. However, the cell killing effect of Ad coated with CD or CD-PEG500 was not influenced by blocking with integrin Abs at all. It is demonstrating that an alternative infection pathway of oncolytic Ad by coating with RGD-conjugated polymer could be achieved by the presence of the RGD-targeting peptides. Through all these data, we might expect that the RGD-conjugated polymer (Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD) can deliver oncolytic Ad depending on the presence of RGD tumor homing peptides to cancer cells selectively.

Fig. 5.

Exclusive killing effect of oncolytic Ad coated with CD-PEG500-RGD depending on RGD peptides by competition assay. HT1080 cells expressing high levels of integrins were treated with Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500 or Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD at an MOI of 100 (2.5 × 105 polymer molecules per Ad particle). After incubation for 2 days, cell viability was measured by MTT assay.

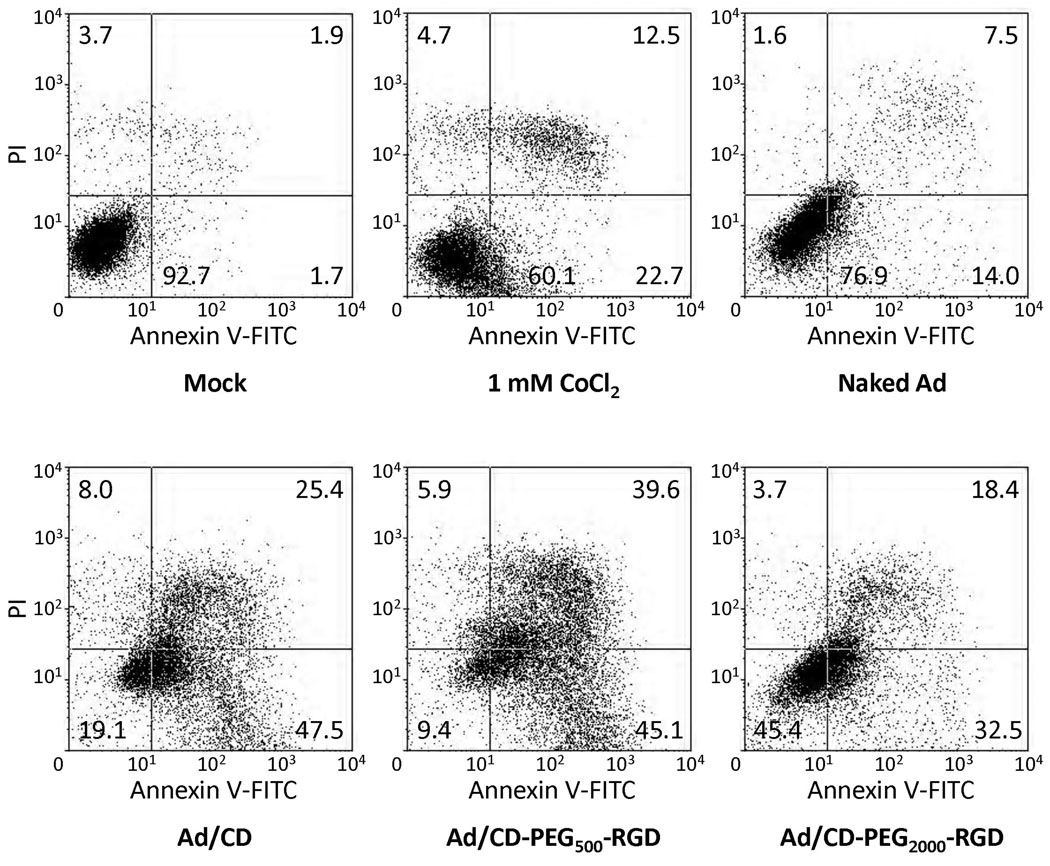

3.6. Induction of apoptosis

To confirm whether the increased cancer cell-killing effect of oncolytic Ad covered with polymers was also mediated by the induction of apoptosis, flow cytometry analysis using Annexin V-FITC and PI double staining was accomplished. HT1080 cells were treated at an MOI of 50 with naked Ad or Ad coated with each polymer (Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD). The cells treated with 1 mM of CoCl2 were utilized as a positive experimental group. At 2 days post-treatment, the harvested cells were reacted with FITC-conjugated Annexin V and with PI to differentiate apoptotic and necrotic cells. In Fig. 6, the right quadrants (Annexin V positive) indicate apoptotic cell populations and upper quadrants (PI positive) indicate necrotic cell populations. Of the CoCl2-treated cells, 35.2% of the cells were apoptotic while only 21.5% of the apoptotic cells when treated with naked Ad. However, the apoptotic and necrotic populations of the cells treated with only each polymer were quite similar with that of untreated cells (data not shown). Apoptotic cell populations treated with Ad/polymer were significantly increased, especially the cells treated with Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD showed that 84.7% were apoptotic and 45.5% were necrotic, while the cells treated with Ad/CD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD exhibited that 72.9% or 50.9% were apoptotic and 33.4% or 22.1% were necrotic, respectively. In comparison with the cells treated with naked Ad, much increased percentages of cells when treated with Ad/polymers were undergoing apoptosis followed by enhanced cancer cell killing effect.

Fig. 6.

Induction of apoptosis by Ad/polymers in HT1080 cells. The cells treated with naked Ad, Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD at an MOI of 50 (2.5 × 105 polymer molecules per Ad particle) were analyzed by flow cytometric analysis of Annexin V-FITC binding and PI uptake. The cells treated with 1 mM of CoCl2 for 18 hrs were served as an experimental positive control.

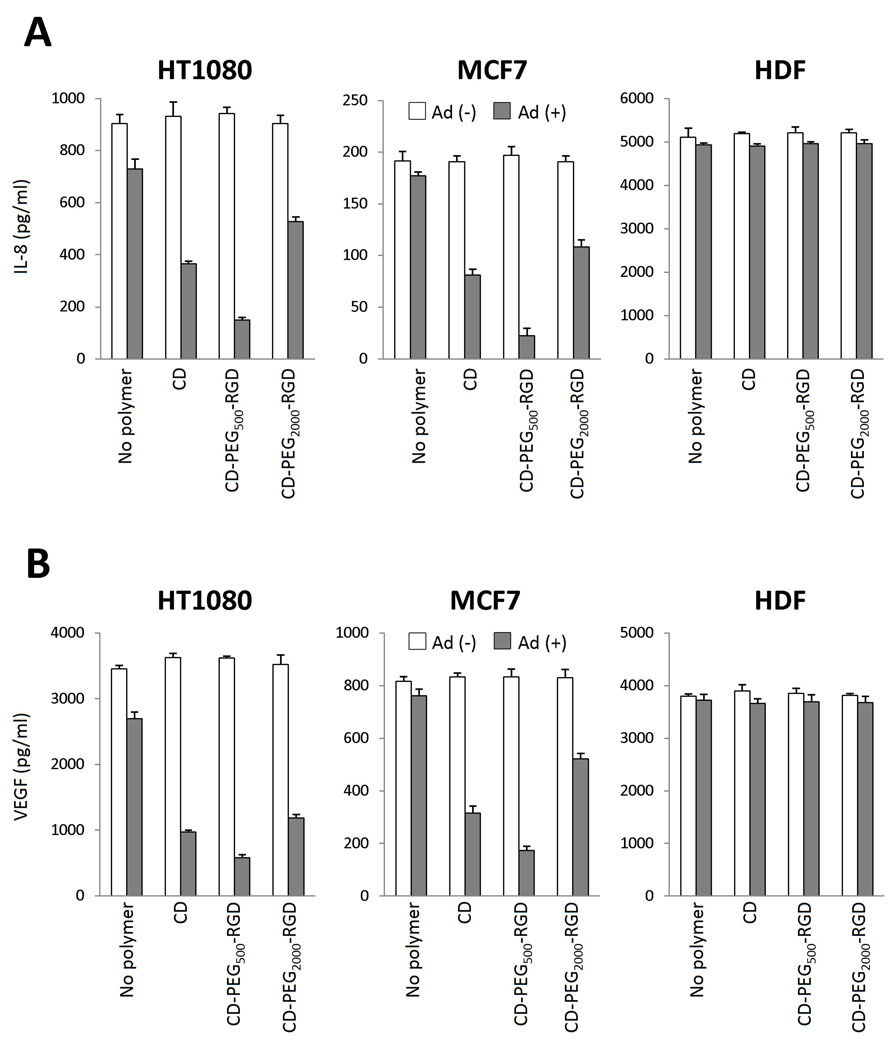

3.7. Suppression of IL-8 and VEGF expression

We previously reported the therapeutic potential of the Ad-ΔB7-U6shIL8 expressing shRNA against IL-8 mRNA in suppressing migration and invasion of cancer cells as well as inhibiting both tumor growth and angiogenesis [29,36]. To investigate the effects of IL-8-specific shRNA, the expression level of IL-8 and VEGF were determined in the supernatants from cancer (HT1080 or MCF7) or normal (HDF) cells treated with naked Ad, Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD using the respective ELISA assay kits. As shown in Fig. 7, the significant suppression of IL-8 (Fig. 7A) or VEGF (Fig. 7B) expression by Ad/polymers was observed in both cancer cells (HT1080 and MCF7) when compared with the results by naked Ad. Among all experimental groups, the most prominent suppression of IL-8 or VEGF expression by Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD complex was investigated with 79.6% (p<0.05 versus naked Ad) or 78.5% (p<0.05 versus naked Ad) decrease in HT1080 cells or with 87.4% (p<0.05 versus naked Ad) or 77.2% (p<0.05 versus naked Ad) in MCF7 cells, respectively. No significant suppression of IL-8 or VEGF expression was observed in HDF cells. Since the replication of oncolytic Ad is selectively not allowed in human normal cells, we guess that the transgene expression from oncolytic Ad genome is also strictly restricted in normal cells having regular defense mechanisms. This result is exactly correlated with selective oncolytic effect of Ad coated with each polymer in human cancer or normal cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 7.

Down-regulation of IL-8 or VEGF expression by oncolytic Ad coated with each polymer in human cancer or normal cells. Human cancer (HT1080 or MCF7) or normal (HDF) cell type was treated with naked Ad, Ad/CD, Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD or Ad/CD-PEG2000-RGD at an MOI of 100, 200 or 50 (2.5 × 105 polymer molecules per Ad particle), respectively. After incubation for 2 (HT1080 and MCF7) or 4 (HDF) days, each conditioned medium was measured the expression of IL-8 (A) or VEGF (B) by human IL-8 or VEGF ELISA assay kit, respectively. Only polymer-treated cells were utilized as negative experimental groups to check the effect of each polymer itself on the expression levels of IL-8 or VEGF.

4. Conclusions

We synthesized the RGD-conjugated bioreducible polymer for delivering potent oncolytic Ad expressing shRNA against IL-8 mRNA. The selective and effective cancer cell-killing effect of Ad/CD-PEG500-RGD was evaluated with respect to the accompanying induction of apoptosis and suppression of IL-8 and VEGF. Moreover, we demonstrated that the exclusive infection pathway of oncolytic Ad covered with CD-PEG-RGD could be mediated by the interaction between targeted RGD peptide and integrins highly expressed on the most of cancer cells. Since the bioreducible polymer (CD) has been investigated with the characteristics of low cytotoxicity and high transduction efficiency, tumor-homing peptide-conjugated CD with PEG500 might be used to deliver the oncolytic Ad for in vivo tumor therapy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH CA107070 and by grants from the Ministry of Knowledge Economy (10030051, C-O. Yun) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (R15-2004-024-02001-0, 2010-0029220, 2009K001644, C-O. Yun).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alemany R. Cancer selective adenoviruses. Mol Aspects Med. 2007;28:42–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan JM. Adenovirus-based cancer gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:595–605. doi: 10.2174/156652305774964677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobbelstein M. Replicating adenovirus in cancer therapy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2004;273:291–334. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05599-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirn D. Replication-selective oncolytic adenoviruses: virotherapy aimed at genetic target in cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19:6660–6669. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J, Cho JY, Kim JH, Jung KC, Yun CO. Evaluation of E1B gene-attenuated replicating adenoviruses for cancer gene therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:725–736. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J, Kim JH, Choi KJ, Kim PH, Yun CO. E1A-E1B-double mutant replicating adenovirus elicits enhanced oncolytic and antitumor effects. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:773. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ries SJ, Brandts CH, Chung AS, Biedere CH, Hann BC, Lipner EM, et al. Loss of p14ARF in tumor cells facilitates replication of the adenovirus mutant dl1520 (ONYX-015) Nat Med. 2000;6:1128–1133. doi: 10.1038/80466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauerschmitz GJ, Barker SD, Hemminki A. Adenoviral gene therapy for cancer: from vectors to targeted and replication competent agents. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:1161–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Everett RS, Hedges BL, Ding EY, Xu F, Serra D, Amalfitano A. Liver toxicities typically induced by first-generation adenoviral vectors can be reduced by use of E1, E1b-deleted adenoviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1715–1726. doi: 10.1089/104303403322611737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher KD, Seymour LW. HPMA copolymers for masking and retargeting of therapeutic viruses. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang E, Yun CO. Current advances in adenovirus nanocomplexes: more specificity and less immunogenicity. BMB Rep. 2010;43:781–788. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2010.43.12.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toyoda K, Ooboshi H, Chu Y, Fasbender A, Davidson BL, Welsh MJ, et al. Cationic polymer and lipids enhance adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to rabbit carotid artery. Stroke. 1998;29:2181–2188. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.10.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim PH, Kim TI, Yockman JW, Kim SW, Yun CO. The effect of surface modification of adenovirus with an arginine-grafted bioreducible polymer on transduction efficiency and immunogenicity in cancer gene therapy. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1865–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roelvink PW, Lizonova A, Lee JG, Li Y, Bergelson JM, Finberg RW, et al. The coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor protein can function as a cellular attachment protein for adenovirus serotypes from subgroups A, C, D, E, and F. J Virol. 1998;72:7909–7915. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7909-7915.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wickham TJ, Mathias P, Cheresh DA, Nemerow GR. Integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell. 1993;73:309–319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90231-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leopold PL, Crystal RG. Intracellular trafficking of adenovirus: many means to many ends. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanerva A, Hemminki A. Modified adenoviruses for cancer gene therapy. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:475–480. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han J, Zhao D, Zhong Z, Zhang Z, Gong T, Sun X. Combination of adenovirus and cross-linked low molecular weight PEI improves efficiency of gene transduction. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:105106. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/10/105106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mintzer MA, Simanek EE. Nonviral vectors for gene delivery. Chem Rev. 2009;109:259–302. doi: 10.1021/cr800409e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynn DM, Anderson DG, Putnam D, Langer R. Accelerated discovery of synthetic transfection vectors: parallel synthesis and screening of degradable polymer library. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8155–8156. doi: 10.1021/ja016288p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim YB, Kim SM, Suh H, Park JS. Biodegradable, endosome disruptive, and cationic network-type polymer as a highly efficient and nontoxic gene delivery carrier. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:952–957. doi: 10.1021/bc025541n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ou M, Wang XL, Xu R, Chang CW, Bull DA, Kim SW. Novel biodegradable poly(disulfide amine)s for gene delivery with high efficiency and low cytotoxicity. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:626–633. doi: 10.1021/bc700397x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ou M, Kim TI, Yockman JW, Borden BA, Bull DA, Kim SW. Polymer transfected primary myoblasts mediated efficient gene expression and angiogenic proliferation. J Control Release. 2010;142:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai W, Rao J, Gambhir SS, Chen X. How molecular imaging is speeding up antiangiogenic drug development. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2624–2633. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suh W, Han SO, Yu L, Kim SW. An angiogenic, endothelial-cell-targeted polymeric gene carrier. Mol Ther. 2002;6:664–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim WJ, Yockman JW, Lee M, Jeong JH, Kim YH, Kim SW. Soluble Flt-1 gene delivery using PEI-g-PEG-RGD conjugate for anti-angiogenesis. J Control Release. 2005;106:224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oba M, Aoyagi K, Miyata K, Matsumoto Y, Itaka K, Nishiyama N, et al. Polyplex micelles with cyclic RGD peptide ligands and disulfide cross-links directing to the enhanced transfection via controlled intracellular trafficking. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:1080–1092. doi: 10.1021/mp800070s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pike DB, Ghandehari H. HPMA copolymer-cyclic RGD conjugates for tumor targeting. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:167–183. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoo JY, Kim JH, Kim J, Huang JH, Zhang SN, Kang YA, et al. Short hairpin RNA-expressing oncolytic adenovirus-mediated inhibition of IL-8: effects on antiangiogenesis and tumor growth inhibition. Gene Ther. 2008;15:635–651. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maizel JV, Jr, White DO, Scharff MD. The polypeptides of adenovirus. I. Evidence for multiple protein components in the virion and a comparison of types 2, 7A, and 12. Virology. 1968;36:115–125. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(68)90121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathias P, Wickham TJ, Moore M, Nemerow GR. Multiple adenovirus serotypes use alpha v integrins for infection. J Virol. 1994;68:6811–6814. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6811-6814.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim TI, Ou M, Lee M, Kim SW. Arginine-grafted bioreducible poly(disulfide amine) for gene delivery systems. Biomaterials. 2009;30:658–664. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nam HY, McGinn A, Kim PH, Kim SW, Bull DA. Primary cardiomyocyte-targeted bioreducible polymer for efficient gene delivery to the myocardium. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8081–8087. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu W, Lin J, Chen J. Expression of p14ARF overcomes tumor resistance to p53. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1305–1310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCormick F. ONYX-015 selectivity and the p14ARF pathway. Oncogene. 2000;19:6670–6672. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoo JY, Kim JH, Kwon YG, Kim EC, Kim NK, Choi HJ, et al. VEGF-specific short hairpin RNA-expressing oncolytic adenovirus elicits potent inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Mol Ther. 2007;15:295–302. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]