Abstract

Aim of study

Coptis chinensis rhizomes (Coptidis Rhizoma, CR), also known as “Huang Lian”, is a common component of traditional Chinese herbal formulae used for the relief of abdominal pain and diarrhea. Yet, the action mechanism of CR extract in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome is unknown. Thus, the aim of our present study is to investigate the effect of CR extract on neonatal maternal separation (NMS)-induced visceral hyperalgesia in rats and its underlying action mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were subjected to 3-hr daily maternal separation from postnatal day 2 to day 21 to form the NMS group. The control group consists of unseparated normal (N) rats. From day 60, rats were administrated CR (0.3, 0.8 and 1.3 g/Kg) or Vehicle (Veh; 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose solution) orally for 7 days for the test and control groups, respectively.

Results

Electromyogram (EMG) signals in response to colonic distension were measured with the NMS rats showing lower pain threshold and increased EMG activity than those of the unseparated (N) rats. CR dose-dependently increased pain threshold response and attenuated EMG activity in the NMS rats. An enzymatic immunoassay study showed that CR treatment significantly reduced the serotonin (5HT) concentration from the distal colon of NMS rats compared to the Veh (control) group. Real-time quantitative PCR and Western-blotting studies showed that CR treatment substantially reduced NMS induced cholecystokinin (CCK) expression compared with the Veh group.

Conclusions

These results suggest that CR extract robustly reduces visceral pain that may be mediated via the mechanism of decreasing 5HT release and CCK expression in the distal colon of rats.

Keywords: cholecystokinin, Coptis chinensis rhizomes, irritable bowel syndrome, neonatal maternal separation, Ranunculaceae, serotonin

1. Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a prevalent chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder affecting approximately 10%-15% of the world’s population (Clarke et al., 2009; Cremonini and Talley, 2005). According to The Rome Committee for the classification of functional gastrointestinal disorders, IBS is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort, change in the frequency of stool form, bloating, abnormal bowel habits (diarrhea, constipation or a combination of both) and related symptoms (Crowell et al., 2005; Sohrabi et al., 2010; Spiegel et al., 2010). These symptoms are thought to be associated with a disturbance of the brain-gut axis which contributes to visceral hypersentivity and dysmotility (Akbar et al., 2009; Manabe et al., 2009). The exact etiology of IBS is multi-factoral, including psychological stress (Barreau et al., 2007; Miranda, 2009), environmental factors, genetic predisposition, and diet (Morcos et al., 2009; Saito et al., 2009; Talley, 2006).

Serotonin (5HT) is a neuropeptide that modulates GI tract smooth muscle contractions and the perception of pain (Akbar et al., 2009; Crowell and Wessinger, 2007; Sikander et al., 2009). Ca. 95% of 5HT are found in the GI tract, 90% of which is secreted from enterchromaffin (EC) cells and the remaining 10% are found in the serotonergic neurons of the myenteric plexus (Bertrand and Bertrand, 2010; Sikander et al., 2009). It has been reported that excess amount of 5HT level was found in IBS patients as well as in rodent models (Bertrand and Bertrand, 2010; Kerckhoffs et al., 2008; Ren et al., 2007). In addition, 5HT recptor 3 (5HTR 3) antagonist or 5HTR 4 agonist can reduce IBS symptoms (Gershon and Liu, 2007; Harris and Chang, 2007). Thus, the 5HT signaling pathway is implicated in the development of IBS.

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is a brain-gut hormone that regulates various GI tract functions including satiety, digestion, motility and pain (Varga et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2010).The action of CCK is mediated through the CCK receptors (CCKR), CCKR1 and -2. CCKR1 is primarily distributed in the GI tract (Cawston and Miller, 2010), while CCKR 2 is mainly found in the central nervous system (Fornai et al., 2007). Elevated CCK levels have been reported in patients with IBS in a clinical study (Zhang et al., 2008), suggesting that the CCK pathway is a protential target for IBS treatment.

The rhizomes of Coptis chinensis Franch. (Ranunculaceae) rihizome, officially recognized in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia as Coptidis Rhizoma, (CR), also known as Huang Lian (Anon, 2010), and frequently found in traditional Chinese herbal formulae have been reported to exert a number of pharmacological actions including antihypertensive (Tsai et al., 2008), antibacterial (Kong et al., 2009), and antioxidative (Jung et al., 2009) and anti-inflammatory effects (Kim et al., 2010), among others. Literature reports indicate that CR iself exerts its antiinflammatory effects by downregulation of inflammatory cytoskines expression (Kim et al., 2010) and inhibition of the activator protein-1 and the nuclear factor-kappa B pathways. (Remppis et al., 2010). CR is a key component of many traditinal Chinese medicine (TCM) prescriptions used to treat syndromes including abdominal pain and diarrhea (Chen and Chen, 2004), including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). However, its mechanisms of action have not been elucidated. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to examine the effect of CR on neonatal maternal separation (NMS)-induced visceral hyperalgesia rat model, a well established early-life stress model that mimic human IBS symptoms, and to elucidate possible mechanisms of action in the event of a positive pharmacological action. We hypothesized that CR might reduced the visceral hypersentivity by modulating the 5HT and CCK pathways.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Animal and neonatal maternal separation

The animal experimental procedures detailed below were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland-Baltimore. All male Sprague-Dawley pups grouped to 6 pups per dam on postnatal day 2 (P2 ; date of birth is designated as P0). Pups were randomly assigned to neonatal maternal separation (NMS) or unseparated control (N) groups according to well established protocol (Ren et al., 2007; Tjong et al., 2010). In brief, pups in the NMS group were separated from their mothers and placed into individual cages in an adjacent room, maintained at 22°C, daily for 3 hours (09 :00-12 :00) on P2-P21. The pups were then returned to the maternal cages after the separation period each day. While the N group of rats were allowed to remain in standard cages with their dams. All pups were weaned on day 22 and housed (5 animals per cage) on a 12 :12-hr light-dark cycle (Lights on at 06:00) with free access to food and water ad libitum.

2.2 Plant material

Coptis chinensis rhizomes (Coptidis Rhizoma, CR) were puchased from the Zhixin Chinese Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. (Guangzhou, China) and authenticated macroscopically and mictroscopically according to the descriptions found in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (Anon, 2010) and in the Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards (Anon, 2008). A voucher sample, IBS-09, was deposited at the Herbarium of the School of Chinese Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. The rhizomes were stored in air-tight containers kept in air-conditioned environment until use.

2.3 Preparation of Coptidis Rhizoma (CR) extract

Sliced CR (600 g) was extracted with 600 mL of 70% ethanol for 1 hr by reflux. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was filtered and the filtrate collected. The extraction was then repeated two more times. The filtrates were combined, the ethanol removed by in vacuo evaporation to almost dryness, and the resulting aqueous concentrate was lyophilized to a powder.

2.4 Chemical profile and high-performance liquid chromatography analysis

Pytochemically, Coptis chinensis has been well investigated, and its characterized by the presence of the major alkaloids berberine (5-7%), palmatine (1-4%), coptisine (0.8-2%), berberastine (1%), and jatrorrhizine, among others (Anon, 1999). The qualitative chemical profile (fingerprint) of the CR extract was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described in the Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards (Anon, 2008). In brief, the CR extract was analyzed empolying a chromatographic system consisting of an Agilent 1100 HPLC equipped with an autosampler, an Alltech Prevail C18 HPLC column (4.6 × 250 nm, 5 μm), and a diode-array detector. Separation was achieved by a moible phase containin 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (%, v/v) (A) and acetonitrile (%, v/v) (B) with a linear gradient elution, 0% B-50% B at 0-48 min, 50% B-100% B at 48-55 min, 100% B and was held for 5 min. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. The eluates were monitored by a diode array detector at a wavelength of 346 nm.

2.5 Administration of Coptidis Rhizoma (CR) extract

At 2-month of age, the NMS rats, weighing ca. 250 g, were randomly divided into 4 groups (7 rats per group), with three groups being dosed orally with CR in escalating doses of 0.3 g/Kg, 0.8 g/Kg or 1.3 g/kg in 10 ml/Kg in 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose solution) in volume of 10 ml/Kg per day for seven days. The 4th group, receiving the vehicle (0.5% carboxymethylcellulose solution at 10 ml/Kg body weight) was designated as “Veh”. The N rats were orally dosed only with carboxymethylcellulose solution (10 ml/Kg) for 7 days.

2.6 Implantation of electromyogram electrode and colonic distension-induced visceral hyperalgesia

The visceral motor response to colonic distension was measured by recording the electromyogram (EMG). Rats were anesthetized by inhalation of 2% isoflurane ( in oxygen, 0.5 L/min). A pair of EMG electrodes were surgically implanted at the lower left abdominal area to expose the external oblique abdominal masculature and the electrodes were tunneled subcutaneously, exteriorized and secured at the back of the neck for sebsequent EMG recording. The colonic distension (CRD) study commenced 7 days after EMG electrodes implantation. The response to visceral stimulus was quantitatively assessed by measuring the EMG signals, as described previously (Christianson and Gebhart, 2007; Tjong et al., 2010). The rats were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane (in oxygen, 0.5 L/min) to facilitate placement of the inflatable balloon, constructed from a latex glove finger attached to a Rigiflex balloon dilator via a Y connector to a syringe pump and a sphygomanometer into the descending colon. The balloon catheter was inserted into the rectum. The rats were allowed to recover for 30 min prior to the CRD study. EMG signals in response to CRD were recorded with a PowerLab 16/30 instrument, and analysed using Chart software (AD instruments, Bella Vista, Australia). The pain threshold pressure was defined as the minimum pressure that evokes an observable signal. EMG signal responses to CRD were measured at 10, 20, 40, 60 and 80 mm Hg. (Tjong et al., 2010). The change of the EMG signal responses to CRD were determined by calculating the change of area-under-curve (AUC) of raw EMG amplitude responses to CRD, based on the formula ΔAUC % baseline ( AUC during CRD/ AUC before CRD).

2.7 Tissure preparation

Rats were anesthetized immediately after the completion of the CRD study, the distal colon dissected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C.

2.8 Measurement of serotonin content

Frozen samples of the distal colon tissues were homogenized in 0.2N HClO4 and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.2μm filter. One volume of the supernatant was neutralized to pH 7-8 with one volume of 1M borate buffer (pH 9.25), followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 1 min at 4 °C. The serotonin (5HT) content of an aliquot (100μl) of the sample was analysed by ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). The sample was measured spectrophotometrically by a microplate reader ( BMG Labtech, Offenburg, USA) at 405 nm. The absorbance of the sample was converted into concentration by standard calibration, and the 5HT content of the tissue was expressed as a function of wet weight (ng/g tissue).

2.9 Total RNA isolation

Frozen distal colon tissues were homogenized with 1ml of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and the total RNA extracted following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, homogenates were mixed in choroform and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The RNA was precipitated with isopropanol and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and the precipitated RNA was treated with 75% ethanol, followed by centrifugation at 7,500g for 5 min at 4°C. The total RNA pellet was air dried, resuspended in Rnase-free water and its concentration measured by use of a Fluostar Optima spectrometer ( BMG Labtech, Offenbury, Germany). For cDNA synthesis, 1.5μg of total RNA was mixed with a reverse-transcription master mix using high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The reverse transcription reaction was performed in a thermal cycler (9800 Fast Thermal Cycler, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

2.10 Real-time quantitative PCR

A cDNA sample (2μl) and the primer was added along with the primer to GeneAmp Fast PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and brought to a final volume of 20μl. The primers and taqman fluorogenic probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems, and their sequences are shown in table 1. Real-time quantitative PCR amplification reactions were carried out in a Step One Plus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). cDNA was empolyed to quantify mRNA encoding β-actin, which is used as a non-regulated reference gene. The thermocycling reaction was carried out at 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 sec and 60 °C for 1 min. The data were analysed with the Step One software and relative gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔ cycle threshold (CT) method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). In brief, the CT values were normalized by substracting from the β-actin control (ΔCT = CT target gene mRNA- CT β-actin control). The expression of mRNA of target gene in the NMS or CR groups was calculated by substracting the normalized CT values in the N group from those in the NMS or CR groups (ΔΔ CT=ΔCT NMS or CR-ΔCT N), and the relative expression (2−ΔΔCT) was thus determined.

Table 1.

Primer sequences of CCK, CCK R1, CCK R2, SERT, 5HTR 3a, 3b and 4.

| Primer | Primer sequence 5’-3’ | |

|---|---|---|

| CCK | (forward) | 5’- ACT GCT AGC CCG ATA CAT CC -3’ |

| CCK | (reverse) | 5’- ATC CAT CCA GCC CAT GTA GT -3’ |

| (sense) | 5’- CAG GGC CTG GAC CCT AGC CA -3’ | |

|

| ||

| CCKR 1 | (forward) | 5’- ATG CTC ATT GTC ATC GTG GT -3’ |

| CCKR 1 | (reverse) | 5’- GAG TCC CTG AGA GGT GCT TC -3’ |

| (sense) | 5’- CCG TGT CAT ATG CCC GCC AG -3’ | |

|

| ||

| CCKR 2 | (forward) | 5’- TCC ATT GGA GAC TGT GGA AA -3’ |

| CCKR 2 | (reverse) | 5’- GCT TCC CAT AAA CCA CAC CT -3’ |

| (sense) | 5’- CCT GCC TCT CCT CCC TCA CCA -3’ | |

|

| ||

| SERT | (forward) | 5’- AGG AGT TCT ACT TGC GCC AT -3’ |

| SERT | (reverse) | 5’- AAG ATG AGC ACG ATG CAG AG -3’ |

| (sense) | 5’- CCA GGA CCT GGG CAC CAT CA -3’ | |

|

| ||

| 5HTR 3a | (forward) | 5’- CCT CAA CGT GGA TGA GAA GA -3’ |

| 5HTR 3a | (reverse) | 5’- GGA TGG ACA ATT TGG TGA CA -3’ |

| (sense) | 5’- TCG TCG GTC CAG AAC TGC CG -3’ | |

|

| ||

| 5HTR 3b | (forward) | 5’- TTC CGG AAC GAT TAG AAA CC -3’ |

| 5HTR 3b | (reverse) | 5’- CAG GAA GCC CAG GTC TAT GT -3’ |

| (sense) | 5’- CCA TCC AGG TGG TCT CCG CA -3’ | |

2.11 Western-blotting study

Frozen distal colons were homogenized in the lysis buffer containing 10μl of protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, USA), and centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The proteins were mixed with the Laemmi buffer, incubated at 70 °C for 3min. Protein samples were separated by using 10% SDS-polyacrylamide mini-gel. The membranes were transferred to polyvinylidene-difluoride membranes using a transblotting apparatus (Bio-Rad laboratories, USA) and blocked with 5% skimmed milk in TBS buffer at room temperature for 2 hours. The membranes were then incubated with the primary antibodies aganist CCK, CCKR 1, CCKR 2, SERT, 5HTR 3a, 5HTR 3b, 5HTR 4 or β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, USA) overnight at 4°C. Immunoreactivity was detected with the secondary antibody, anti-mouse, anti-rabbit or anti-goat IgG conjuated to HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, USA). The blots were developed using a chemiluminescence’s reagent, with the films being exposed and analyzed by using Image J (National Institutes of Health, USA).

2.12 Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean±SE. Statistical analyses were performed using a Prims 4.0 software (GraphPad sofware Inc, la Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significances were determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc multiple comparison using Dunnett’s test and differences were considered significant at *P<0.05.

3. Results

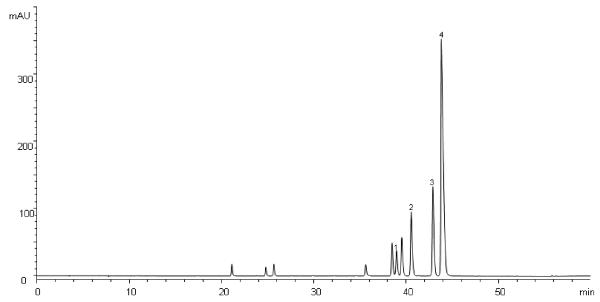

3.1 Chemical quality assurance by HPLC analysis of CR

HPLC analysis of the CR analyte gave a fingerprint chromatogram consistent with that established for CR by the HKCMMS (Anon, 2008), with four major alkaloids (jatrorrhizine, coptisine, palmatine and berberine) being identified in the extract by comparison of peak retention and relative retention times with those of reference compounds (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HPLC chromatogram of CR extract (1 mg/ml) detected at 346 nm. Signals 1-4 were identified to be jatrorrhizine, coptisine, palmatine and berberine.

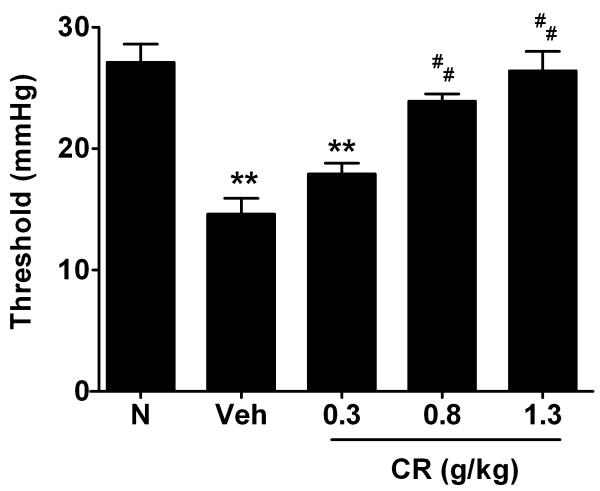

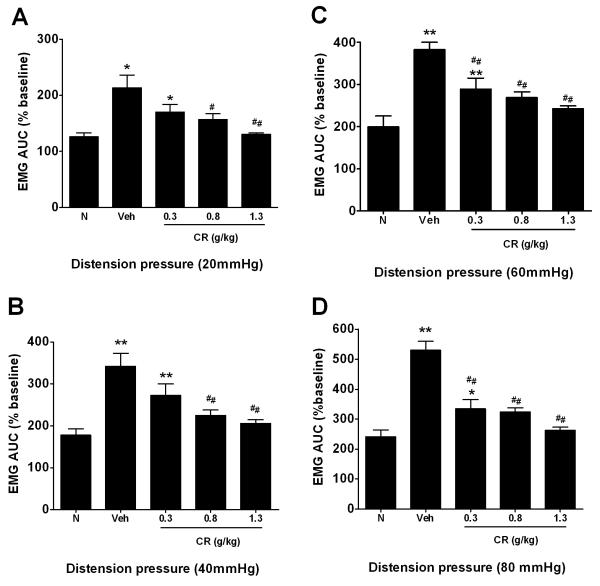

3.2 CR attenuates visceral hyperalgesia in NMS rats in response to CRD

NMS Veh rats were more sensitive to colonic distension than the N rats, as demonstrated by a reduction in threshold to pain (N=7 per group; p<0.01) (Figure 2). On average, the pain threshold pressures were 27.1±1.5 mmHg and 14.6±1.3 mmHg in N and NMS Veh rats, respectively. Pre-treatment of CR at doses of 0.8 (middle dosage) and 1.3 g/Kg (high dose) substantially elevated threshold to pain by 65% (N=7; p<0.01) and 80% (N=7; p<0.01), respectively, compared with Veh animals in the NMS rats (Figure 2). In particular, there were no significant changes among N and CR at middle and high dose groups. In the EMG recording, the Veh group showed a significant response to CRD at 20 mm Hg (Figure 3A), and the EMG magnitude increased by 164.1±35.3%, 183.8±35.4% and 289.7±37.8% to CRD at 40, 60 and 80 mm Hg, respectively, as compared to the N group (Figure 3B-D). On the other hand, the CR dosed (0.8 and 1.3 g/Kg) NMS groups significantly depressed the elevated EMG signals of the Veh group at all pressure response to CRD (Figure 3A-D). No significant differences among CR at middle and high dose as compared with N rats.

Figure 2.

Effect of CR on pain threshold pressure among groups. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is indicated by **P<0.01 compared with N group (Dunnett’s test); ##P<0.01 compared with NMS Veh group (Dunnett’s test).

Figure 3.

Effect of CR on electromyographic activity response to CRD at pressure of 20, 40, 60 and 80mmHg (A-D). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is indicated by *P<0.05 or **P<0.01 unpaired t-test compared with N group (Dunnett’s test; #P<0.05 or ##P<0.01 versus NMS Veh group (Dunnett’s test).

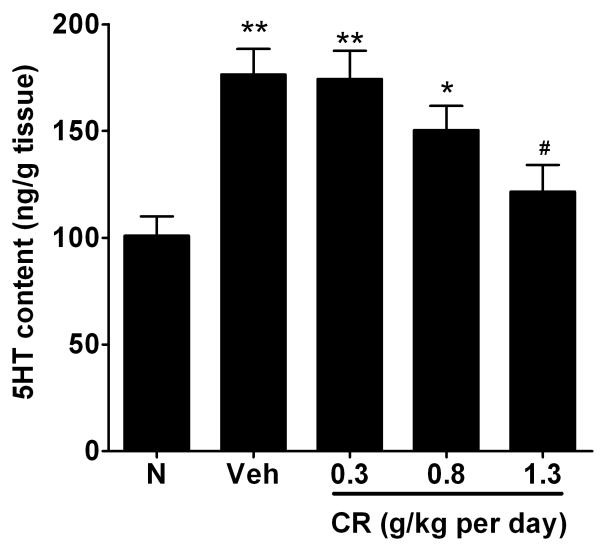

3.3 CR decreases 5HT content in the distal colon of NMS rats

The 5HT level from the distal colon was significantly increased in the Veh rats in comparison to the N rats (100.9±9.1 ng/g of tissue versus 176.4±12.0 ng/g of tissue, n=6, p<0.01) (Figure 4). The elevated 5HT content exhibited by the NMS Veh group was substantially lowered in the NMS rats pretreated with CR at 1.3 g/Kg (by 54.8±17.4%; p<0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of CR on the 5HT content in distal colon of rats. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM (ng/g tissue). **P<0.01 or *P<0.05 compared with N group (Dunnett’s test); #P<0.05 versus NMS Veh group (Dunnett’s test).

3.4 CR does not change the expressions of SERT, 5HTR subtypes in NMS rats

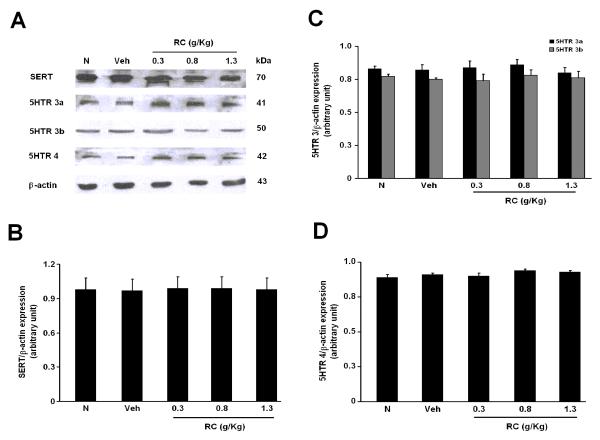

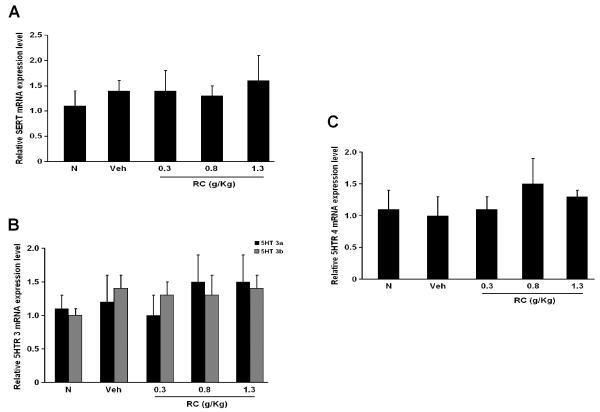

The mRNA and protein levels of SERT, 5HTR 3a, 3b and 4 were determined by RT-PCR and Western-blotting studies respectively. SERT, 5HTR 3a, 3b and 4 were all present in both the N and NMS groups (Figure 5 and 6). Yet, there were no apparent changes in the level of their expressions among the groups (Figure 5 and 6).

Figure 5.

(A) Protein levels of SERT, 5HTR 3a, 3b and 4 expressions in the distal colon of rats. Effects of CR on the protein levels of (B) SERT, (C) 5HTR 3a, 3b and (D) 5HTR 4 in N, NMS Veh and CR groups.

Figure 6.

mRNA expressions of (A) SERT, (B) 5HTR3a, 5HTR 3b and (4) 5HTR 4 in the distal colon of rats.

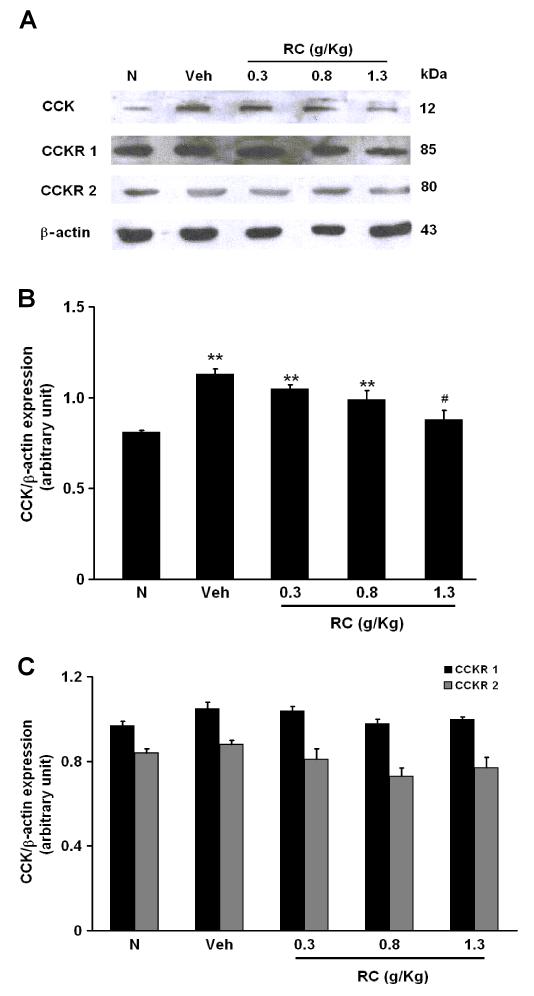

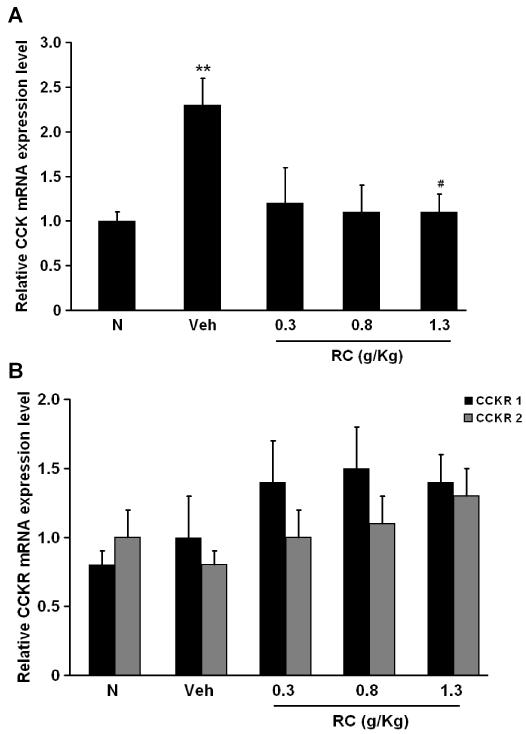

3.5 CR significantly elevates CCK expressions in NMS rats

Protein expressions of CCK and CCKR subtypes from the distal colon were determined by Western-blotting study. Increased protein level of CCK was observed in NMS rats (Figure 7A). On average, the level of CCK expression from the distal colon of Veh rats was increased by 32.0±3.2% compared to the N group (Figure 6A). The protein level of CCK in the NMS rats treated with CR at 1.3 g/Kg was significantly less (by 25.0±5.8%) than that in the Veh group (Figure 7B). CCKR1 and 2 were present in the distal colon of both of the N and NMS rats (Figure 7A). There were no apparent differences in CCKR 1 and 2 expressions among the groups (Figure 7C). The mRNA expression of CCK and CCKR subtypes were examined by RT-PCR. As shown as in figure 8A, CCK expression in the NMS Veh rats was higher than that in the N rats (1.0±0.1 versus 2.3±0.3, n=6, p<0.01). Treatment with CR at 1.3 g/Kg significantly decreased CCK expression by 39.7±2.0% from the distal colon of NMS rats as compared to the N rats (Figure 8A), while there were no significant changes in CCKR 1 and 2 expressions among the groups (Figure 8B).

Figure 7.

(A) Protein levels of CCK, CCKR 1 and 2 expressions in the distal colon of rats. (B) Effect of CR on the levels of CCK protein expression among groups. **P<0.01 compared with N group (Dunnett’s test); #P<0.05 compared with NMS Veh group (Dunnett’s test). (C) Effect of CR on the levels of CCKR1 and 2 protein expressions among groups.

Figure 8.

(A) Summary of relative mRNA expression of CCK in distal colon among groups. **P<0.01 compared with N group (Dunnett’s test); #P<0.05 compared with NMS Veh group (Dunnett’s test). (B) Effect of CR on relative mRNA CCKR1 and 2 expressions among groups.

4. Discussion

The present study is the first to show that the Chinese herb CR markedly reduced visceral pain in NMS rats in a dose-dependent manner. Recurrent visceral pain is one of the main clinical observation of IBS that affects the quality of the patient’s daily life (Wong and Drossman, 2010). Although the etiology of this symptom is not clearly understood, an increasing number of studies have reported that both pyschological and physical early-life stress contributes to the risk for developing IBS (Chitkara et al., 2008; Gareau et al., 2008; Miranda, 2009). In the present study, we observed decreased pain threshold and elevated EMG activity in NMS rats, which are consistent with the observations recorded in our previous studies, as well as those reported by others (Chung et al., 2007; Ren et al., 2007; Tjong et al., 2010) , and that NMS is a prominent stressor causing visceral hyperalgesia (Coutinho et al., 2002). Our study provides evidence that CR treatment dose-dependently increased the pain threshold pressure and depressed EMG activity evoked by CRD. Thus, CR extract may be an effective herbal treatment for mitigating the visceral pain of IBS.

It is widely accepted that 5-HT is a key messenger in modulating visceral perception in the enteric nervous system via the paracrine, endocrine and neurocrine pathways (McLean et al., 2007). Our study found that the 5HT content from the distal colon was elevated in NMS rats, which confirms with published clinical findings of the presence of increased 5HT level in the distal colon of IBS patients (Bertrand and Bertrand, 2010; Kerckhoffs et al., 2008), suggesting that 5-HT plays an important role in the pathophysiology of IBS. It has been reported that 5HT exerts its action via 5HTR, in which 5HT3a, 3b and 4 play prominent role in the regulation of gut functions (Sikander et al., 2009). It is reported that 5HTR 3 mediates IBS by activation of extrinsic primary neurons (Gershon, 2005), while 5HTR 4 promotes cyclic AMP and increases the release of acetylcholine from the neurons to the gut (Tonini, 2005). The action of 5HT in the gut was terminated and reuptake took place through the action of serotonin transporter (SERT) (Martel, 2006). Excess 5HT or SERT could alter the signaling pathway for gut motility and pain transmission (Spiller, 2008), and hence 5HT can act as a biomarker for IBS. Our results also showed that treatment of NMS rats with CR substantially attenuated the colonic 5HT concentration. However we did not observe any significant effect of CR on SERT and 5HTR expressions in the NMS rats, which suggest that the attenuated 5-HT release by CR may be mediated through the modulation of tryptophan hydroxylase activity in EC cells (Liu et al., 2008) rather than SERT and 5HTR.

CCK belongs to the gastrin family, which is synthesized and released from the endocrine cells in the GI tract. It has recently been found to be involved in the modulation of GI tract motility (Varga et al., 2004). Administration of CCK promotes colonic motor response in healthy guinea pig, and in the ascending colon in human (Morton et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2010). Our results show that CCK expression from the distal colon was elevated in NMS rats. Greisen at al also found serum CCK level was elevated in NMS rats (Greisen et al., 2005), suggesting that early-life stress causes excess CCK secretion that disrupt the brain-gut axis. Clinical studies also reported increased plasma CCK level in IBS patient (Van Der Veek et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008), and CCKR antagonists reduced visceral perception in IBS patients (Scarpignato and Pelosini, 1999). These findings indicate that CCK is also a critical factor involved in the pathophysiology of IBS. Our results showed a downregulation of CCK expression in NMS rats treated with CR. Yet, CR did not have any effect on either CCKR 1 or CCKR 2 from the distal colon of NMS rats, suggesting that CR not only reduced 5HT release but also CCK expression, in lowering the visceral sensitivity.

In conclusion, our present study provides evidence that CR substantially attenuates visceral hyperalgesia by lowering 5-HT release and CCK expression in the colon of NMS rats. These findings also suggest that CR may be an effective herbal preparation for the treatment of IBS. The present study on individual herb may also provide useful information for better formulating a Chinese formula for IBS and better design of future clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), NIH, No. 1-U19-AT003266. The contexts are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reprsent the official views of NCCAM. The authors thank all members of this program for their partnership and support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akbar A, Walters JR, Ghosh S. Review article: visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic agents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:423–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anon . WHO monograph on selected Medicinal Plants. Vol. 1. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Anon . The Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards. Hong Kong Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government; Hong Kong: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anon . Pharmacopoeia of The People′s Republic of China. 2010 Chinese Edition Chemical Industry Press; Beijing: 2010. pp. 285–286. [Google Scholar]

- Barreau F, Ferrier L, Fioramonti J, Bueno L. New insights in the etiology and pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome: contribution of neonatal stress models. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:240–245. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3180db2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand PP, Bertrand RL. Serotonin release and uptake in the gastrointestinal tract. Auton Neurosci. 2010;153:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawston EE, Miller LJ. Therapeutic potential for novel drugs targeting the type 1 cholecystokinin receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:1009–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Chen T. Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology. 1st Edition ed AOM Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MA, Blois-Martin N, Whitehead WE. Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:765–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01722.x. quiz 775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson JA, Gebhart GF. Assessment of colon sensitivity by luminal distension in mice. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2624–2631. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, Zhang X, Li Z, Zhang H, Xu H, Bian Z. Neonatal maternal separation enhances central sensitivity to noxious colorectal distention in rat. Brain Res. 2007;1153:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G, Quigley EM, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Irritable bowel syndrome: towards biomarker identification. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:478–489. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho SV, Plotsky PM, Sablad M, Miller JC, Zhou H, Bayati AI, McRoberts JA, Mayer EA. Neonatal maternal separation alters stress-induced responses to viscerosomatic nociceptive stimuli in rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G307–316. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00240.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremonini F, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome: epidemiology, natural history, health care seeking and emerging risk factors. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:189–204. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell MD, Harris L, Jones MP, Chang L. New insights into the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome: implications for future treatments. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7:272–279. doi: 10.1007/s11894-005-0019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell MD, Wessinger SB. 5-HT and the brain-gut axis: opportunities for pharmacologic intervention. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:761–765. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornai M, Colucci R, Antonioli L, Baschiera F, Ghisu N, Tuccori M, Gori G, Blandizzi C, Del Tacca M. CCK2 receptors mediate inhibitory effects of cholecystokinin on the motor activity of guinea-pig distal colon. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareau MG, Silva MA, Perdue MH. Pathophysiological mechanisms of stress-induced intestinal damage. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:274–281. doi: 10.2174/156652408784533760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon MD. Nerves, reflexes, and the enteric nervous system: pathogenesis of the irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:S184–193. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000156403.37240.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon MD, Liu MT. Serotonin and neuroprotection in functional bowel disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(Suppl 2):19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greisen MH, Bolwig TG, Wortwein G. Cholecystokinin tetrapeptide effects on HPA axis function and elevated plus maze behaviour in maternally separated and handled rats. Behav Brain Res. 2005;161:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LA, Chang L. Alosetron: an effective treatment for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2007;3:15–27. doi: 10.2217/17455057.3.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HA, Min BS, Yokozawa T, Lee JH, Kim YS, Choi JS. Anti-Alzheimer and antioxidant activities of Coptidis Rhizoma alkaloids. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:1433–1438. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerckhoffs AP, Ter Linde JJ, Akkermans LM, Samsom M. Trypsinogen IV, serotonin transporter transcript levels and serotonin content are increased in small intestine of irritable bowel syndrome patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:900–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Jung HA, Choi JS, Lee NG. Identification of anti-inflammatory target genes of Rhizoma coptidis extract in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264.7 murine macrophage-like cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong WJ, Zhao YL, Xiao XH, Wang JB, Li HB, Li ZL, Jin C, Liu Y. Spectrum-effect relationships between ultra performance liquid chromatography fingerprints and anti-bacterial activities of Rhizoma coptidis. Anal Chim Acta. 2009;634:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Yang Q, Sun W, Vogel P, Heydorn W, Yu XQ, Hu Z, Yu W, Jonas B, Pineda R, Calderon-Gay V, Germann M, O′Neill E, Brommage R, Cullinan E, Platt K, Wilson A, Powell D, Sands A, Zambrowicz B, Shi ZC. Discovery and characterization of novel tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitors that selectively inhibit serotonin synthesis in the gastrointestinal tract. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:47–55. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe N, Tanaka T, Hata J, Kusunoki H, Haruma K. Pathophysiology underlying irritable bowel syndrome--from the viewpoint of dysfunction of autonomic nervous system activity. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2009;45:15–23. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.45.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel F. Recent advances on the importance of the serotonin transporter SERT in the rat intestine. Pharmacol Res. 2006;54:73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean PG, Borman RA, Lee K. 5-HT in the enteric nervous system: gut function and neuropharmacology. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda A. Early life stress and pain: an important link to functional bowel disorders. Pediatr Ann. 2009;38:279–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcos A, Dinan T, Quigley EM. Irritable bowel syndrome: role of food in pathogenesis and management. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton MF, Welsh NJ, Tavares IA, Shankley NP. Pharmacological characterization of cholecystokinin receptors mediating contraction of human gallbladder and ascending colon. Regul Pept. 2002;105:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remppis A, Bea F, Greten HJ, Buttler A, Wang H, Zhou Q, Preusch MR, Enk R, Ehehalt R, Katus H, Blessing E. Rhizoma Coptidis inhibits LPS-induced MCP-1/CCL2 production in murine macrophages via an AP-1 and NFkappaB-dependent pathway. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:194896. doi: 10.1155/2010/194896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren TH, Wu J, Yew D, Ziea E, Lao L, Leung WK, Berman B, Hu PJ, Sung JJ. Effects of neonatal maternal separation on neurochemical and sensory response to colonic distension in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G849–856. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00400.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito YA, Mitra N, Mayer EA. Genetic approaches to functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2009;138:1276–1285. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpignato C, Pelosini I. Management of irritable bowel syndrome: novel approaches to the pharmacology of gut motility. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13(Suppl A):50A–65A. doi: 10.1155/1999/183697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikander A, Rana SV, Prasad KK. Role of serotonin in gastrointestinal motility and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;403:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi S, Nouraie M, Khademi H, Baghizadeh S, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Malekzadeh R. Epidemiology of uninvestigated gastrointestinal symptoms in adolescents: a population-based study applying the Rome II questionnaire. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:41–45. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d1b23e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel BM, Bolus R, Harris LA, Lucak S, Chey WD, Sayuk G, Esrailian E, Lembo A, Karsan H, Tillisch K, Talley J, Chang L. Characterizing abdominal pain in IBS: guidance for study inclusion criteria, outcome measurement and clinical practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller R. Serotonin and GI clinical disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1072–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley NJ. Genes and environment in irritable bowel syndrome: one step forward. Gut. 2006;55:1694–1696. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.108837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjong YW, Ip SP, Lao L, Wu J, Fong HH, Sung JJ, Berman B, Che CT. Neonatal maternal separation elevates thalamic corticotrophin releasing factor type 1 receptor expression response to colonic distension in rat. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2010;31:215–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonini M. 5-Hydroxytryptamine effects in the gut: the 3, 4, and 7 receptors. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:637–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HH, Chen IJ, Lo YC. Effects of San-Huang-Xie-Xin-Tang on U46619-induced increase in pulmonary arterial blood pressure. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;117:457–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Veek PP, Biemond I, Masclee AA. Proximal and distal gut hormone secretion in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:170–177. doi: 10.1080/00365520500206210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga G, Balint A, Burghardt B, D′Amato M. Involvement of endogenous CCK and CCK1 receptors in colonic motor function. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:1275–1284. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong RK, Drossman DA. Quality of life measures in irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;4:277–284. doi: 10.1586/egh.10.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Yan Y, Shi R, Lin Z, Wang M, Lin L. Correlation of gut hormones with irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2008;78:72–76. doi: 10.1159/000165352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Chen L, Xia H, Luo HS. Mechanisms mediating CCK-8S-induced contraction of proximal colon in guinea pigs. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1076–1085. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i9.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]