Abstract

Treatment with the chemotherapeutic agent oxaliplatin produces a robust painful neuropathy similar to various other neuropathic conditions which result in loss of nerve fibers innervating the skin. This loss of intraepidermal nerve fibers (IENFs) appears to play an important role in neuropathy, but has yet to be investigated in oxaliplatin-induced neuropathic pain. For this study, mechanical hyperalgesia and IENF density were measured in rats receiving oxaliplatin, given at a dosage of 2 mg/kg every other day for four injections. The immuomodulatory agent minocycline (25 mg/kg) was also administered and was given 24 hours prior to the first dose of oxaliplatin and continued throughout oxaliplatin treatment. Immunohistochemistry using the pan-neuronal marker PGP9.5 was used to investigate IENF densities in hind paw skin on Day 15 and Day 30. The results show that a robust mechanical sensitivity developed in oxaliplatin treated animals, as did a pronounced decrease in epidermal nerve fibers, and these outcomes were effectively prevented by minocycline treatment. This is the first study to show changes in IENF density in oxaliplatin treated animals, and confirms not only a relationship between IENF loss and hypersensitivity but also prevention of both with minocycline treatment.

Keywords: neuropathy, oxaliplatin, intraepidermal nerve fiber, minocycline, chemotherapy

It is well known that chemotherapy produces pain and sensory disturbances broadly defined as chemoneuropathy; however, the reason neuropathy develops is poorly understood, and current medications do little to improve neuropathy symptoms. Neuropathy is observed following various chemotherapy agents, including paclitaxel (Taxol) (Dougherty et al,2004;Postma et al,1995), vincristine (Postma et al,1993), and cisplatin (Quasthoff and Hartung,2002) and presents as a mildly disrupting tingling sensation to an extremely painful paresthesia. Patients experiencing neuropathy often opt for potentially less effective treatment to avoid this side effect, and for many, the sensory disturbances and pain are persistent, lasting for months or years after treatment cessation (Cata et al,2006).

Approximately sixty five (Argyriou et al,2007) to eighty seven (Louvet et al,2002) percent of patients receiving the platinum compound oxaliplatin complain of chronic neuropathy symptoms following treatment. These symptoms force up to 13% of patients to discontinue curative treatment, with obvious negative implications for survival and disease outcomes. Further, once chronic neuropathy develops in this population, 40% of patients will continue to experience neuropathy for six months or longer (Argyriou et al,2008), making it clear that defining protective treatments is an imperative goal.

Oxaliplatin also produces a robust neuropathy in animals (Cavaletti et al,2001), and this model has been used in an attempt to better characterize oxaliplatin-related neurotoxicities. As with humans, animals given higher cumulative dosages and more aggressive (i.e. frequent) treatment exhibited more severe toxicity, including weight loss and more pronounced hyperalgesia. These rats also had decreased DRG cell size and nucleolar segregation, along with decreased nerve conduction velocities (Cavaletti et al,2001).

It might also be expected that oxaliplatin treatment would result in additional changes to peripheral nerves. Biopsies of patients with diabetes (Kennedy et al,1996;Shun et al,2004), complex regional pain syndrome (Oaklander et al,2006), and post-herpetic neuralgia (Petersen et al,2010) all show marked decreases in nerve fibers in the skin, specifically those that innervate the epidermis. These intraepidermal nerve fibers (IENFs) are bare nerve endings arising from unmyelinated and thinly myelinated nociceptors within the dermis and are important for the transmission of peripheral pain. The absence of epidermal fibers is so reliably present in diabetes-related neuropathy that researchers have proposed using fiber analysis as an indicator of the severity of small fiber neuropathy in these patients (Lauria et al,2009). Recently, researchers have shown that, in addition to a significant increase in sensitivity to mechanical stimuli, the number of nerve fibers present within the epidermis of rats following treatment with the chemotherapeutic agent paclitaxel (Taxol) decrease drastically (Boyette-Davis et al,2010;Siau et al,2006).

For this study, mechanical hyperalgesia and IENF density were investigated during and after treatment with the chemotherapeutic agent oxaliplatin. Minocycline, a broad spectrum antibiotic with known immunomodulatory effects, including inhibition of the NfKB pathway (Nikodemova et al,2006), was used in an attempt to prevent changes in mechanical sensitivity and IENF density. This drug has previously been shown to prevent mechanical hyperalgesia in various rodent models of neuropathic pain, including Taxol-induced (Cata et al,2008) and surgically induced (Bennett,1999) neuropathic pain and can prevent IENF loss following Taxol treatment (Boyette-Davis et al,2010).

Methods

Subjects

Thirty (30) male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan), age 60 days old at the beginning of the experiment, were used. Prior to the beginning of the study, animals were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: minocycline / oxaliplatin (n=8), minocycline / vehicle (n=6), vehicle / oxaliplatin (n=10), and vehicle / vehicle (n=6). Animals were housed 3 per cage on corncob bedding and maintained on a 12 hour light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. Animals were weighed daily during treatment, and were weighed just after behavioral testing thereafter. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee for the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and adhered to the guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals and by the Committee for Research and Ethical Issues of the International Association for the Study of Pain (Zimmermann,1983).

Drugs

Oxaliplatin (Tocris) was diluted to a concentration of 1mg/ml using saline and given at a dosage of 2mg/kg every other day for a total of four injections (Days 1, 3, 5, and 7). Control animals received an equivalent volume of saline. Minocycline hydrochloride (Sigma) was diluted in saline and buffered using NaOH (corrected pH range: 6.8 to 7.4). The final concentration of minocycline was 15mg/ml, given at 25mg/kg. Minocycline was given every day for ten consecutive doses, beginning 24 hours prior to the first dose of oxaliplatin (Days 0–9). Control animals received saline in similar volumes. On Days 1, 3, 5, and 7 when both drugs were to be administered, minocycline was given approximately 30 minutes prior to oxaliplatin.

Mechanical paw withdrawal threshold testing

To assess responses to mechanical stimulation of the hind paws, an ascending set of von Frey monofilaments was used (Boyette-Davis et al,2010). Animals were individually placed inside Plexiglas containers (10×10×4in) set upon an elevated wire mesh stand and were then allowed to habituate for 15 minutes. Environmental factors (i.e. noise level, lighting conditions, time of day testing occurred, and experimenter performing the testing) were held constant throughout the experiment. On injection days, testing was conducted prior to drug administration. The testing session began with administration of the lowest force monofilament (1 gram) applied for one second to the left, and then the right, mid-plantar region of the hind paw. Each monofilament was applied a total of 6 times to each paw before the next higher force monofilament (4, 10, 15, 26, and 60 grams) was used. The monofilament at which the animal made a response of paw withdrawal, flinching, or licking 3 out of the 6 applications was defined as the 50% withdrawal threshold. On Day 15 and 30, biopsies were taken after testing was concluded to avoid detection of possible sensitivity of the tissue surrounding the biopsy site. On Day 22 and Day 30 the biopsy site of the left hind paw was inspected visually prior to testing and no animals showed signs of ongoing inflammation. Testing did not reveal hyperalgesia in the biopsied hind paw of vehicle treated animals on either Day 22 or Day 30.

Immunohistochemistry

Two 3mm biopsies were taken from each animal, one from the left hind paw on Day 15 and another from the right hind paw on Day 30, under anesthesia. Biopsies were immediately placed in Zamboni’s fixative, left overnight, and transferred to 20% sucrose for at least 24 hours. Tissue was then frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (OCT) and sliced into 25um sections. Free floating sections were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in .1M PBS containing 5% NDS/.3% Triton X-100. Blocking solution was decanted and primary antibody was added. The pan neuronal marker PGP9.5 (AbD Serotec; rabbit) was diluted 1:1000 in wash buffer (1% NDS/.3% Triton X 100), along with collagen IV (Southern Biotech; goat), which was diluted 1:25 in wash buffer. PGP9.5 reliably immunostains intraepidermal nerve fibers, while collagen IV stains the basement membrane between the dermal/epidermal junction. Following an overnight incubation with the primary antibody, slices were washed 3 times, one hour each wash, and allowed to incubate overnight with the secondary antibodies: donkey anti-rabbit Cy3 (1:400) and donkey anti-goat Cy2 (1:200). Tissue was washed in wash buffer and mounted onto slides.

Quantification of intraepidermal nerve fibers

Quantification of IENFs was conducted as previously described (Boyette-Davis et al,2011). Briefly, five randomly chosen slices per animal were analyzed using a Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope. Quantification was done by an experimenter who was blind to all conditions. Nerve fibers that crossed the collagen stained dermal/epidermal junction into the epidermis were counted in three fields of view from each slice using a 40× objective. The length of the epidermis within each field of view was measured using Nikon NIS Elements software. IENF density was determined as the total number of fibers per unit length of epidermis (IENF/mm) (McArthur et al,1998). Fibers that branched after crossing the basement membrane were counted as a single fiber.

Data analysis

Data for mechanical paw withdrawal threshold values, weight, and the IENF quantification were analyzed using separate repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Significant effects were further examined using the Tukey HSD test for post hoc comparisons. The significance level was set at p<.05 for all tests.

Results

Mechanical Paw Withdrawal Threshold

As shown in Figure 1, compared to control animals, rats treated with oxaliplatin developed a persistent state of hypersensitivity to mechanical stimulation, starting on Day 6 and continuing through Day 30 (p<.001). No significant acute effect of oxaliplatin was detected 1 hour or 4 hours after injection. Conversely, animals receiving oxaliplatin in conjunction with minocycline did not develop hyperalgesia, indicating a protective effect of minocycline. Minocycline itself did not alter mechanical thresholds.

Figure 1.

Oxaliplatin produces a decrease in mechanical paw withdrawal threshold that is prevented by treatment with minocycline. Animals treated with oxaliplatin (vehicle/oxali; n=10) had a significant decrease in threshold that began on Day 6 when compared to vehicle treated animals (vehicle/vehicle; n=6). Rats receiving oxaliplatin with minocycline pretreatment (mino/oxali; n=8) were not significantly different from vehicle treated animals at any timepoint, indicating a protective effect of minocycline. Minocycline treatment did not alter mechanical responding (mino/vehicle; n=6). (***=p<.0001)

Weight

Both minocycline and oxaliplatin negatively impacted weight gain (Figure 2). Beginning on Day 4 and continuing throughout the remainder of the experiment, animals receiving minocycline with or without oxaliplatin treatment (mino/vehicle; mino/oxali) gained significantly less weight than vehicle treated animals (vehicle/vehicle) (p<.0001). Oxaliplatin alone (vehicle/oxali) had a less pronounced affect on weight and this group was only significantly different from vehicle animals (vehicle/vehicle) on Days 6, 8 and 12, with recovery by Day 15.

Figure 2.

Animals receiving minocycline (mino/vehicle; mino/oxali) gained significantly less weight than animals treated with vehicle (vehicle/vehicle) starting on Day 4 and continuing throughout the experiment. Oxaliplatin treatment alone (vehicle/oxali) also lead to less weight gain on Days 6, 8, and 12; however, these animals had recovered and were not different from vehicle treated rats on Day 30. (***=p<.0001)

IENF changes

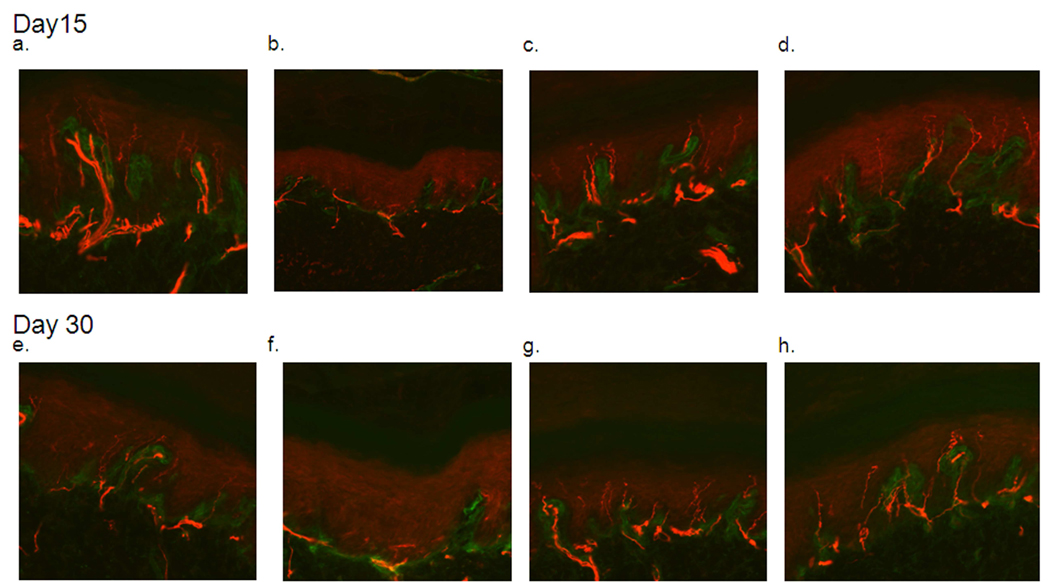

The average total length of epidermis that was measured for each slice of skin was 2.39mm, and this length did not vary significantly across groups or time points. At the time of the first biopsy (Day 15), animals receiving oxaliplatin had significantly less IENFs (p<.001) compared to vehicle treated animals, whereas animals receiving oxaliplatin with minocycline pretreatment were not significantly different from vehicle treated animals in regards to IENF counts. Minocycline treatment alone did not alter fiber density (Figure 4). Figure 3 shows representative samples from animals treated with the vehicles (a), vehicle/oxaliplatin (b), minocycline/oxaliplatin (c), and minocycline/vehicle (d). The vehicle treated animals showed even and abundant distribution of nerve fibers entering the epidermis which were almost absent in animals treated with oxaliplatin and were preserved in animals pretreated with minocycline.

Figure 4.

Oxaliplatin treatment (vehicle/oxaliplatin) results in decreased intraepidermal nerve fibers within the footpad of the hind paw at Day 15 and Day 30. Rats receiving oxaliplatin with minocycline pretreatment (mino/oxali) did not have altered IENF density compared to vehicle treated animals (vehicle/vehicle), indicating that minocycline protected against oxaliplatin-induced nerve fiber loss. Minocycline treatment alone (mino/vehicle) did not significantly change nerve fiber density. (**=p<.001; ***=p<.0001)

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemisty results showing staining of intraepidermal nerve fibers by PGP9.5. Fibers can clearly be seen crossing the basement membrane, in green, and extending as long lines into the epidermis. A through d show epidermal innervation on Day 15 from animals treated with the vehicle (a), vehicle/oxaliplatin (b), minocycline/oxaliplatin (c), and minocycline/vehicle (d). Similar results were found on Day 30 for vehicle (e), vehicle/oxaliplatin (f), minocycline/oxaliplatin (g), and minocycline/vehicle (h) treated animals.

The results from Day 30 were identical to those from Day 15, with animals treated with oxaliplatin having significantly less IENFs than animals treated with vehicle (p<.0001) (Figure 4). As in the previous day, pretreatment with minocycline protected fibers from oxaliplatin-induced depletion. Minocycline-only treated animals were again not significantly different from vehicle treated animals. Figure 3 shows representative samples from animals treated with the vehicles (e), vehicle/oxaliplatin (f), minocycline/oxaliplatin (g), and minocycline/vehicle (h) which were similar to those from Day 15.

Discussion

This study is the first to show that treating animals with minocycline can prevent oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy symptoms. Additionally, this is the first study to show IENF density changes as a result of oxaliplatin treatment, a discovery that was also prevented by treatment with minocycline.

The finding that oxaliplatin produced a robust hypersensitivity to mechanical stimulation is in agreement with previous reports. The incidence of neuropathy-like symptoms in humans receiving oxaliplatin varies widely based on risk factors such as cumulative dose and dosing schedule (Argyriou et al,2007), but once present this neuropathy is persistent, lasting at least 6 to 8 months for most patients and forcing patients to adopt a “stop-and-go” approach to therapy (de Gramont,2005). The present study found significant mechanical hyperalgesia in oxaliplatin treated animals by Day 6 of the experiment, which is earlier than others have reported. Sakurai (Sakurai et al,2009) found increased mechanical sensitivity on Day 24, and Ling (Ling et al,2007) reported that significant hyperalgesia was not present until Day 12. However, these researchers administered oxaliplatin twice a week instead of the four injections given in one week within this experiment. Importantly, treatment with minocycline protected against the development of oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia. Other interventions have been used with varying success to improve or prevent oxaliplatin neuropathy. For example, magnesium produced improved tail immersion thresholds in hypersensitive oxaliplatin treated rats. This effect was reported to be present for up to three hours following oxaliplatin treatment, but longer lasting effects were not reported (Ling et al,2007). Similar effects for acute neuropathy have also been reported in patients preventatively infused with magnesium (Gamelin et al,2004). Magnesium pretreatment may also be effective at decreasing the incidence of chronic neuropathy (Wolf et al,2008), although more data is needed. These findings encourage the discovery of a safe preventative measure for chemoneuropathy, an area where the findings of the present study could prove to be extremely useful.

The loss of IENFs in animals treated with oxaliplatin supports the finding of IENF loss following treatment with other chemotherapeutic agents, such as Taxol (Boyette-Davis et al,2010;Siau et al,2006) and vincristine (Siau et al,2006). Although it is currently unclear what drives epidermal denervation, one plausible explanation includes the role of cytokines. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are released from multiple sources following chemotherapy, including epithethial cells (Darst et al,2004). Levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukins 1 and 6 (IL-1 and IL-6) and interferons alpha and gamma (IFNα and IFNγ) are all increased following exposure to cisplatin (Basu and Sodhi,1992) (Gan et al,1992;Pai and Sodhi,1991) and Taxol (O'Brien, Jr. et al,1995) (Zaks-Zilberman et al,2001). These cytokines contribute greatly to both pain and damage to neurons and supporting cells. Exogenous administration of TNFα, IL-1, or IL-6 results in mechanical hyperalgesia, and it has also been shown that antagonists for these cytokines can decrease pain responding in an animal model of neuropathy (Milligan et al,2003). TNFα can contribute directly to pain by leading to increased activity in nociceptors (Sorkin et al,1997). Further, cytokines can lead to damage to both Schwann cells (Scarpini et al,2001) and oligodendrocytes.

In further support of a cytokine hypothesis, minocycline, a tetracycline derivative with known anti-cytokine capabilities, not only prevented hyperalgesia but also prevented the loss of IENFs following oxaliplatin treatment. Raghavendra (Raghavendra et al,2003) showed that minocycline can decrease the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and subsequent pain behaviors if given prior to L5 spinal nerve transection. Decreased pain behavior has also been shown in other models of neuropathy, including surgically induced (Bennett,1999) and Taxol-induced (Boyette-Davis et al,2010;Cata et al,2008) neuropathies, and in formalin-induced pain (Cho et al,2006). Additionally, minocycline protects against aforementioned cytokine-related damage to Schwann cells (Keilhoff et al,2008).

Although it cannot be determined from these results that IENF loss is the underlying cause of the mechanical hyperalgesia, these data indicate that this loss is at least involved in the persistence of neuropathy. Intraepidermal nerve fibers, reliably stained with the pan-neuronal marker PGP9.5, are bare nerve endings arising from unmyelinated and thinly myelinated nociceptors within the dermis. As these fibers reach the dermal/epidermal junction, they lose their myelin sheath and extend upward between the various layers of keratinocytes within the epidermis. Nolano et al (Nolano et al,1999) showed that IENFs transmit noxious sensations of thermal and mechanical origin from the skin, and capsaicin stimulated loss of IENFs corresponded to diminished loss of these sensations. It may seem contradictory then that diabetes and other disease related neuropathies where decreased IENFs are found result in increased, not decreased, pain sensations; however, explanations for this paradox can be found in the literature. During early stages of neuropathy, patients often report numbness and tingling, likely due to the initial loss of nerve fibers. As neuropathy persists and fiber loss becomes more prominent, the condition leads to perhaps a centrally mediated hypersensitivity. Within the skin, spared fibers are most likely exposed to a host of inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, which serve to lower the threshold and increase the excitability of these fibers. Dorsal root ganglion cells and dorsal horn neurons undergo increased excitability with decreased input from the periphery. Within the brain, loss of normal peripheral input produced changes similar to phantom-limb pain. Oaklander (Oaklander,2001) recently referred to these changes, which are present in postherpetic neuralgia, as a “phantom-skin pain.”

In conclusion, this study is the first to investigate IENFs in oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia. The observed loss of these fibers is hypothesized to play an important role in the persistence of chemotherapy-related peripheral neuropathy. Importantly, both mechanical hyperalgesia and IENF loss were prevented by treatment with minocycline.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grant NS46606 and National Cancer Institute grant CA124787 and by the Astra-Zeneca Corporation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Argyriou AA, Polychronopoulos P, Iconomou G, Chroni E, Kalofonos HP. A review on oxaliplatin-induced peripheral nerve damage. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2008;34:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argyriou AA, Polychronopoulos P, Iconomou G, Koutras A, Makatsoris T, Gerolymos MK, Gourzis P, Assimakopoulos K, Kalofonos HP, Chroni E. Incidence and characteristics of peripheral neuropathy during oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy for metastatic colon cancer. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:1131–1137. doi: 10.1080/02841860701355055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Sodhi A. Increased release of interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor by interleukin-2-induced lymphokine-activated killer cells in the presence of cisplatin and FK-565. Immunol. Cell Biol. 1992;70(Pt 1):15–24. doi: 10.1038/icb.1992.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ. Does a neuroimmune interaction contribute to the genesis of painful peripheral neuropathies? Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1999;96:7737–7738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyette-Davis J, Xin W, Zhang H, Dougherty PM. Intraepidermal nerve fiber loss corresponds to the development of Taxol-induced hyperalgesia and can be prevented by treatment with minocycline. Pain. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyette-Davis J, Xin W, Zhang H, Dougherty PM. Intraepidermal nerve fiber loss corresponds to the development of Taxol-induced hyperalgesia and can be prevented by treatment with minocycline. Pain. 2011;152:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cata JP, Weng HR, Dougherty PM. The effects of thalidomide and minocycline on taxol-induced hyperalgesia in rats. Brain Res. 2008;1229:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cata JP, Weng H-R, Dougherty PM. Clinical and experimental findings in humans and animals with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Minerva Anes. 2006;72:151–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaletti G, Tredici G, Petruccioli MG, Donde E, Tredici P, Marmiroli P, Minoia C, Ronchi A, Bayssas M, Etienne GG. Effects of different schedules of oxaliplatin treatment on the peripheral nervous system of the rat. European Journal of Cancer. 2001;37:2457–2463. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho IH, Chung YM, Park CK, Park SH, Li HY, Kim D, Piao ZG, Choi SY, Lee SJ, Park K, Kim JS, Jung SJ, Oh SB. Systemic administration of minocycline inhibits formalin-induced inflammatory pain in rat. Brain Research. 2006;1072:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darst M, Al Hassani M, Li T, Yi QF, Travers JM, Lewis DA, Travers JB. Augmentation of chemotherapy-induced cytokine production by expression of the platelet-activating factor receptor in a human epithelial carcinoma cell line. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172:6330–6335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gramont A. Rapid evolution in colorectal cancer: Therapy now and over the next five years. Oncologist. 2005;10:4–8. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty PM, Cata JP, Cordella JV, Burton A, Weng H-R. Taxol-induced sensory disturbance is characterized by preferential impairment of myelinated fiber function in cancer patients. Pain. 2004;109:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamelin L, Boisdron-Celle M, Delva R, Guerin-Meyer V, Ifrah N, Morel A, Gamelin E. Prevention of oxaliplatin-related neurotoxicity by calcium and magnesium infusions: a retrospective study of 161 patients receiving oxaliplatin combined with 5-Fluorouracil and leucovorin for advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4055–4061. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan XH, Jewett A, Bonavida B. Activation of human peripheral-blood-derived monocytes by cis- diamminedichloroplatinum: enhanced tumoricidal activity and secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Nat.Immun. 1992;11:144–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilhoff G, Schild L, Fansa H. Minocycline protects Schwann cells from ischemia-like injury and promotes axonal outgrowth in bioartificial nerve grafts lacking Wallerian degeneration. Experimental Neurology. 2008;212:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy WR, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Johnson T. Quantitation of epidermal nerves in diabetic neuropathy. Neurology. 1996;47:1042–1048. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.4.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauria G, Lombardi R, Camozzi F, Devigili G. Skin biopsy for the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy. Histopathology. 2009;54:273–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling B, Authier N, Balayssac D, Eschalier A, Coudore F. Behavioral and pharmacological description of oxaliplatin-induced painful neuropathy in rat. Pain. 2007;128:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvet C, Andre T, Tigaud JM, Gamelin E, Douillard JY, Brunet R, Francois E, Jacob JH, Levoir D, Taamma A, Rougier P, Cvitkovic E, de Gramont A. Phase II study of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and folinic acid in locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:4543–4548. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur JC, Stocks EA, Hauer P, Cornblath DR, Griffin JW. Epidermal nerve fiber density: normative reference range and diagnostic efficiency. Arch.Neurol. 1998;55:1513–1520. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.12.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan ED, Twining C, Chacur M, Biedenkapp J, O'Connor K, Poole S, Tracey K, Martin D, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Spinal glia and proinflammatory cytokines mediate mirror-image neuropathic pain in rats. J.Neurosci. 2003;23:1026–1040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-01026.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikodemova M, Duncan ID, Watters JJ. Minocycline exerts inhibitory effects on multiple mitogen-activated protein kinases and I kappa B alpha degradation in a stimulus-specific manner in microglia. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;96:314–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolano M, Simone DA, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Johnson T, Hazen E, Kennedy WR. Topical capsaicin in humans: parallel loss of epidermal nerve fibers and pain sensation. Pain. 1999;81:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien JM, Jr, Wewers MD, Moore SA, Allen JN. Taxol and colchicine increase LPS-induced pro-IL-1 beta production, but do not increase IL-1 beta secretion. A role for microtubules in the regulation of IL-1 beta production. J.Immunol. 1995;154:4113–4122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oaklander AL. The density of remaining nerve endings in human skin with and without postherpetic neuralgia after shingles. Pain. 2001;92:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oaklander AL, Rissmiller JG, Gelman LB, Zheng L, Chang YC, Gott R. Evidence of focal small-fiber axonal degeneration in complex regional pain syndrome-I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy) Pain. 2006;120:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai K, Sodhi A. Effect of cisplatin, rIFN-Y, LPS and MDP on release of H2O2, O2- and lysozyme from human monocytes in vitro. Indian J.Exp.Biol. 1991;29:910–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen KL, Rice FL, Farhadi M, Reda H, Rowbotham MC. Natural history of cutaneous innervation following herpes zoster. Pain. 2010;150:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma TJ, Benard BA, Huijgens PC, Ossenkoppele GJ, Heimans JJ. Long term effects of vincristine on the peripheral nervous system. J.Neuro-Onocol. 1993;15:23–27. doi: 10.1007/BF01050259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma TJ, Vermorken JB, Liefting AJM, Pinedo HM, Heimans JJ. Paclitaxel-induced neuropathy. Ann.Onocol. 1995;6:489–494. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quasthoff S, Hartung H-P. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J.Neurol. 2002;249:9–17. doi: 10.1007/pl00007853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra V, Tanga F, DeLeo JA. Inhibition of microglial activation attenuates the development but not existing hypersensitivity in a rat model of neuropathy. J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther. 2003;306:624–630. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai M, Egashira N, Kawashiri T, Yano T, Ikesue H, Oishi R. Oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy in the rat: Involvement of oxalate in cold hyperalgesia but not mechanical allodynia. Pain. 2009;147:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpini E, De Riz M, Conti G, Scarlato G. Painful symptoms of diabetic neuropathy. Giornale di Neuropsicofarmacologia. 2001;23:127–128. [Google Scholar]

- Shun CT, Chang YC, Wu HP, Hsieh SC, Lin WM, Lin YH, Tai TY, Hsieh ST. Skin denervation in type 2 diabetes: correlations with diabetic duration and functional impairments. Brain. 2004;127:1593–1605. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siau C, Xiao W, Bennett GJ. Paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked painful peripheral neuropathies: Loss of epidermal innervation and activation of Langerhans cells. Exp.Neurol. 2006;201:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin LS, Xaio W-H, Wagner R, Myers RR. Tumour necrosis factor-α induces ectopic activity in nociceptive primary afferent fibres. Neuroscience. 1997;81:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J, Richardson PG, Schuster M, LeBlanc A, Walters IB, Battleman DS. Utility of bortezomib retreatment in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma patients: a multicenter case series. Clin.Adv.Hematol.Oncol. 2008;6:755–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaks-Zilberman M, Zaks TZ, Vogel SN. Induction of proinflammatory and chemokine genes by lipopolysaccharide and paclitaxel (Taxol) in murine and human breast cancer cell lines. Cytokine. 2001;15:156–165. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann M. Ethical guidelines for investigators of experimental pain inconscious animals. Pain. 1983;16:109–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]