Abstract

Recently, there has been significant progress in the development of genetically-engineered mouse (GEM) models. By introducing genetic alterations and/or signaling alterations of human pancreatic cancer into the mouse pancreas, animal models can recapitulate human disease. Pancreas epithelium-specific endogenous Kras activation develops murine pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (mPanIN). Additional inactivation of p16, p53, or transforming growth factor-β signaling, in the context of Kras activation, dramatically accelerates mPanIN progression to invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) with abundant stromal expansion and marked fibrosis (desmoplasia). The autochthonous cancer models retain tumor progression processes from pre-cancer to cancer as well as the intact tumor microenvironment, which is superior to xenograft models, although there are some limitations and differences from human PDAC. By fully studying GEM models, we can understand the mechanisms of PDAC formation and progression more precisely, which will lead us to a breakthrough in novel diagnostic and therapeutic methods as well as identification of the origin of PDAC.

Keywords: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Genetically-engineered mouse, Pancreas epithelium-specific, Kras, Tumor-stromal interaction, Tumor microenvironment, Origin of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Murine pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, Acinar-ductal metaplasia, Inducible genetically-engineered mouse

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer and biliary cancer are the most lethal cancers and the incidence rate is increasing. Currently, pancreatic cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death in Japan and the fourth in the USA[1,2]. Biliary cancer is found most frequently in Japan where it is the sixth leading cause of cancer death[3]. The annual incidence and number of deaths is very close, which indicates the high lethality of both cancers. To overcome these lethal cancers, disease models that can recapitulate human conditions would be of great help in understanding the details of the disease and developing novel therapeutic approaches.

Previously, xenograft models (i.e. subcutaneous tumor and orthotopic tumor) have been used as in vivo tumor models by inoculating human cancer cell lines or tissues into immunocompromised mice. Scientists creating genetically-engineered mouse (GEM) models have strived to mimic human pancreatic cancer for years, and recently models close to the human disease have been established. As described below, there are clear differences between xenograft tumors and GEM model tumors and the latter model is considered a closer approximation of human disease conditions; therefore, using GEM models in preclinical studies will provide various benefits.

Recent progress in GEM models of pancreatic cancer can be called a breakthrough in pancreatic cancer research. In this review, I discuss the advances and current limitations of GEM models of pancreatic cancer. On the other hand, in the biliary cancer field, there is no GEM model yet and we are waiting for the establishment one of such a model. I apologize in advance to colleagues whose work could not, unfortunately, be sited in this review.

MULTI-STEP CARCINOGENESIS HYPOTHESIS OF PANCREATIC DUCTAL ADENOCARCINOMA ALONG WITH GENETIC ALTERATIONS

Since most pancreatic cancers found in the clinic are “conventional” pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), we should target and model PDAC. Hereafter, I focus on PDAC in this review.

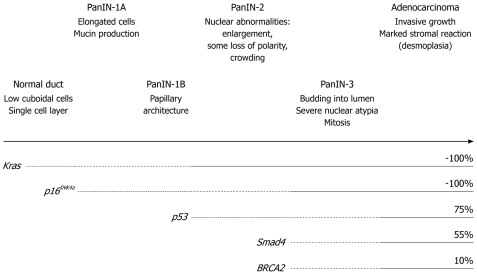

Like the famous adenoma-carcinoma sequence in colorectal cancer, a multi-step carcinogenesis hypothesis of PDAC, which is linked to an accumulation of genetic alterations, has currently been consensually accepted clinically: As genetic alterations accumulate in normal pancreatic epithelial cells, precancer lesions, pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) emerge, they progress in stage and eventually progress into invasive cancer, when tumor cells invade beyond the basal membrane[4] (Figure 1). A constitutive active point mutation of the Kras gene codon 12 has already been found at the stage of early, low grade PanIN and found nearly 100% at the invasive cancer stage. There is no such highly frequent spot mutation as this in sporadic solid cancers, which suggests that the Kras activation might truly initiate the PDAC carcinogenesis process. Inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs); i.e. p16INK4a, p53, Smad4, are found along with the PanIN stage progression, which suggests that these are also involved in the process of PDAC formation.

Figure 1.

Multi-step carcinogenesis hypothesis of pancreatic cancer. As genetic alterations of Kras, p16INK4a, p53, Smad4 and BRCA2 accumulate, the pre-cancer lesion pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) occurs and progresses from low-grade (1A, 1B) to high-grade (2, 3) and to invasive cancer. The frequency of each genetic alteration at the invasive cancer stage is also shown.

However, PanIN cannot be detected by current diagnostic imaging modalities, and, therefore, we usually have no chance to observe the transition from PanIN to invasive PDAC.

Recently, by introducing PDAC-related genetic alterations into mouse pancreas, several GEM models recapitulating human PDAC have been established.

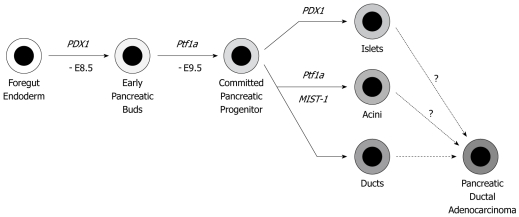

To achieve pancreas-specific genetic engineering, a Cre-loxP system driven by the PDX1 or Ptf1a (p48) gene promoter is mainly employed. PDX1 and Ptf1a are expressed from embryonic days 8.5 and 9.5, respectively. Both are required for pancreas development and differentiation. The pancreatic epithelium at the adult stage contains three lineage cells: acinar cells, duct cells (both are exocrine cells) and islet cells (endocrine cells) (Figure 2). Since PDX1 and Ptf1a are expressed before divergence into these three lineages, Cre-loxP recombination is executed in all the three lineages. If PDAC really originates from normal pancreatic duct cells, pancreatic duct cell-specific genetic alteration might be the best approximation. However, to date, there is no available pancreatic duct-specific promoter. Therefore, the PDX1 or Ptf1a-driven models cannot provide definite answers as to whether the duct cells are the real origin of PDAC. However, these models show murine PanINs (mPanINs) and develop PDAC. Considering that previous GEM models resulted in only acinar cell carcinoma or islet cell tumors, current models are very close to human PDAC.

Figure 2.

Cell differentiation program in the pancreas. PDX1 and Ptf1a genes are expressed on E8.5-9.5 d, which determines the cell fate in the pancreas epithelium. By using the PDX1 or Ptf1a gene promoter-induced Cre-loxP system, all three lineages (islet, acini and duct) have the designed genetic alterations. The cell of origin of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is still under discussion. Experimentally, PDAC can be derived from all three lineages.

ENDOGENOUS KRASG12D EXPRESSION MODEL

Current GEM models of PDAC have been improved greatly by the establishment of the “endogenous” KrasG12D expression model[5]. When a constitutively active mutant KrasG12D protein is expressed in a pancreas epithelium-specific manner, the mice demonstrate a gradual mPanIN progression, which is very close to human PanIN. This history-making model elucidates that the Kras mutation, almost always found in human PDAC, is necessary and sufficient for an initiation of PDAC carcinogenesis. Subsequently, this endogenous KrasG12D expression model became a platform for the following GEM models of PDAC.

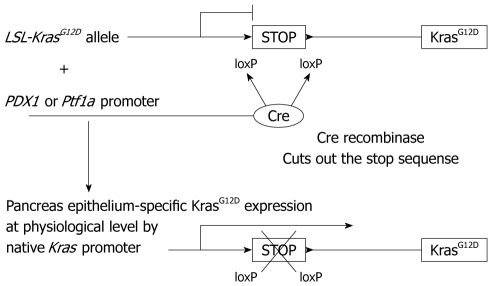

In this endogenous KrasG12D expression model, one Kras gene locus is substituted by a sequence of LSL-KrasG12D (Figure 3). The LSL-KrasG12D contains a loxP-stop-loxP (LSL) sequence inserted in the promoter region upstream of the KrasG12D protein coding sequence. Therefore, only in the pancreas epithelium, where Cre recombinase is expressed, the stop sequence is cut out and downstream KrasG12D protein expression is switched on. Here it is referred to as “endogenous”, because the KrasG12D protein is expressed at a physiological level under the control of the native Kras promoter. The “expression at a physiological level” seems very important in this context. Previous Kras transgenic models might have had an excess level of transcript, which then failed to recapitulate PDAC formation in human disease.

Figure 3.

Pancreas epithelium-specific KrasG12D expression. Cre recombinase is expressed under the promoter of PDX1 or Ptf1a gene, which is pancreas epithelium-specific. Without cre recombinase expression, a stop sequence between the loxP sites prevents mutant KrasG12D expression. In cells where only cre recombinase is expressed, the stop sequence is cut out, which turns on the pancreas epithelium-specific KrasG12D expression at a physiological level under the native Kras promoter.

In this pancreas epithelium-specific endogenous KrasG12D expression model, mPanIN emerges at a couple of weeks of age and progresses in stages over time. mPanIN shows close similarity with human PanIN including strong COX-2 (cyclooxygenase-2) and Hes1 expression. However, they do not progress into invasive PDAC within a year. This suggests that Kras activation might be sufficient to initiate PDAC carcinogenesis, but a second event might be required to accelerate the process into invasive PDAC formation.

MODELS OF ENDOGENOUS KRASG12D EXPRESSION PLUS INACTIVATION OF TUMOR SUPPRESSOR

In combination of endogenous KrasG12D expression and inactivation of TSGs, as shown Figure 1, invasive PDAC models have been established. They have been established with endogenous KrasG12D expression plus p16INK4a/Arf knockout[6], or mutant p53 expression[7], or p53 knockout[8], or transforming growth factor-β receptor 2 (Tgfbr2) knockout[9]. In December 2004, an epoch-making meeting “Pancreatic cancer in mice and man: the Penn Workshop 2004” was held at the University of Pennsylvania. A number of well-known pathologists of human pancreatic cancer joined and reviewed existing GEM models of pancreatic cancer, and completed a consensus report on GEM models of PDAC[10]. In the report, models including the endogenous KrasG12D expression were recognized as the closest approximation of human PDAC carcinogenesis through PanIN, although acinar-ductal metaplasia was commonly observed and might have progressed into PDAC in the GEM models.

Among these endogenous KrasG12D plus TSG inactivation models, KrasG12D plus p16INK4a/Arf knockout was the first published model of invasive PDAC[6]. In this model, PDAC grows very rapidly and aggressively invades other organs directly. The median survival time is nearly 8 wk and all animals die by 11 wk of age. It seems that they die too quickly to form distant metastasis. The second one was the KrasG12D plus mutant p53 expression model[7]. In this model, mutant p53 protein is expressed at a physiological level by the endogenous p53 promoter. This model develops PDAC and frequent metastasis to the liver and/or lung, the most frequent sites of metastasis in human PDAC. The median survival is nearly 5 mo. Inactivation of p53 also causes chromosomal instability. These endogenous KrasG12D plus TSG inactivation models, including KrasG12D plus p16 knockout and KrasG12D plus p53 knockout[8], basically demonstrate differentiated PDAC with expanded stromal components, which is very close to human PDAC compared to previous models. However, these models also frequently contained undifferentiated tumors, sarcomatoid tumor or anaplastic carcinoma, which are infrequent in human PDAC.

ENDOGENOUS KRASG12D EXPRESSION PLUS TGFBR2 KNOCKOUT MODEL

We established the endogenous KrasG12D expression plus Tgfbr2 knockout model[9]. The mice demonstrate only differentiated ductal adenocarcinoma without any undifferentiated or sarcomatoid tumor histology, which suggests that this model might have the closest histology with human PDAC.

TGF-β, a well-known cytokine with multiple functions in various conditions, has a growth inhibitory effect on epithelial cells and is recognized as a tumor suppressor in the early stages of carcinogenesis[11]. The TGF-β ligand binds to two membranous receptors of serine/threonine kinase and the downstream signals are mainly transduced through the Smad2/3/4 pathway. In human PDAC, Smad4 gene deletion or mutation is found in more than 50% of patients, which is characteristically frequent compared with other cancers[12]. Tgfbr2 gene mutations are less than 5%[13], however, it is also reported that down regulation of Tgfbr2 gene expression is observed in nearly 50% of PDAC[14].

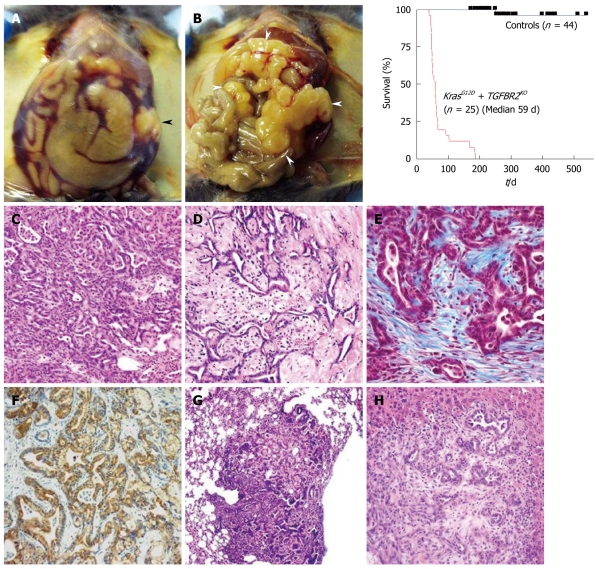

We mimicked a blockade of TGF-β signaling by Tgfbr2 knockout, a little upstream of Smad4. The endogenous KrasG12D expression plus Tgfbr2 knockout model shows mPanIN-like lesions at 3 wk of age and a rapid progression to PDAC in a few weeks. Almost all normal pancreas structure is lost by 6-7 wk of age, followed by death, with a median survival of 59 d (8 wk). In this clinical course, the mice demonstrate abdominal distension (92%), body weight loss (80%), ascites (60%) and jaundice (12%), which were frequently found in human PDAC patients. The histology is differentiated ductal adenocarcinoma with abundant stromal components and marked fibrosis (desmoplasia), which is very close to human PDAC (Figure 4). Furthermore, this model does not contain sarcomatoid tumor histology as described above, which is considered an advantage of this model. Most of the mice die too quickly to form distant metastasis, however, some mice infrequently lived over 20 wk and all of them showed metastasis to lung and liver as well as peritoneal dissemination, which suggests a highly invasive potential.

Figure 4.

Endogenous KrasG12D plus transforming growth factor-β receptor 2 knockout pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. A, B: Macroscopic appearances and a survival curve of the endogenous KrasG12D plus transforming growth factor-β receptor 2 (Tgfbr2) knockout pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) mice; A: Abdominal distension and bloody ascites are observed. Black arrowhead indicates the tumor; B: The whole pancreas is occupied by tumor and enlarged (white arrowheads). Jaundice is also observed here; C-H: Microscopic appearance of the endogenous KrasG12D plus Tgfbr2 knockout PDAC; C, D: Differentiated ductal adenocarcinoma with abundant stroma is observed in HE sections; E: Marked fibrosis and desmoplasia is observed. The blue color indicates fibrosis in trichrome blue staining; F: Positive immunostaining of cytokeratin 19 indicates a ductal phenotype tumor; G, H: The tumor has a metastatic potential to the lung (G) and liver (H).

The endogenous KrasG12D expression plus Smad4 knockout model was also published by three groups. Surprisingly, all of them showed cystic tumors in the pancreas, which is considered as an approximation of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) or mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), different precancer lesions of PDAC[15-17]. Therefore, although the Smad4 gene is frequently altered in human PDAC, Tgfbr2 knockout in the context of the KrasG12D expression can model human PDAC better than Smad4 knockout in mice. The KrasG12D plus Smad4 knockout model is rather useful for understanding IPMN. IPMN is considered a pre-cancer lesion with a long latent period and much better prognosis than conventional PanIN to PDAC. Recently, however, cases of concomitant PDAC distant from benign IPMN lesions have gained attention. The IPMN models might help in dissecting the relation of PDAC and IPMN.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS OF TRANSLATIONAL RESEARCH USING GEM MODELS OF PDAC

Advantages of GEM models and evaluation of novel therapeutic methods

To date, xenografts, subcutaneous or orthotopic tumors injected with human PDAC cell lines into immunocompromised mice, have been mainly used as in vivo models of PDAC. Evaluation of new therapeutic drugs has also been performed by using the xenografts. In the future, GEM models are to be mainly used in various investigations instead of xenograft models.

The GEM models have the following two major advantages compared to the xenografts: intact tumor progression processes after the engineered genetic alterations and intact tumor microenvironment including tumor-stromal interactions. In xenografts, invasive tumor is suddenly implanted without any pre-cancer processes. In addition, the significance of the tumor microenvironment has been recently drawing attention. PDAC tissues characteristically contain a relatively small number of cancer cells and abundant stromal components, which is difficult to mimic by xenograft models. Cancer-associated fibroblasts, tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils might play important tumor-promoting roles, which might be also incomplete in immunocompromised mice.

Olive et al[18] recently directly compared tumors of xenografts and GEM models of PDAC (endogenous KrasG12D expression plus mutant p53 expression) and reported that in xenograft models, blood vessels are very close to tumor cells and chemo reagents are effectively delivered into the tumors, whereas, in GEM tumors there is dense stroma between the tumor cells and blood vessels, which results in impaired delivery and anti-tumor effects. To date, a number of clinical trials for PDAC have been executed. Although every therapeutic regimen has had a significant anti-tumor effect in preclinical studies, almost all have failed to show superiority to gemcitabine, a current standard chemo reagent. This might also be explained by the difference in the tumor microenvironment between the xenografts and real human tumors, which might be a parallel between xenografts and GEM tumors as described above. Therefore, GEM models might be better for evaluating novel drugs in preclinical studies. Singh et al[19] also compared responses of chemotherapeutic regimens between a GEM model (endogenous KrasG12D expression plus p16INK4a/Arf knockout) and human PDAC patients and stated that the GEM model faithfully reproduces similar survival results of previous human clinical trials. Most xenograft studies have evaluated anti-tumor effects by tumor volume or size and number of metastases, but not by survival. In the preclinical studies using GEM models, novel therapeutics can be evaluated by overall survival rate as a primary endpoint (and also by progression-free survival as a secondary endpoint by using imaging modalities), which is also advantageous and closer to the human situation.

Discovery of early diagnostic methods for PDAC

In trying to establish an early diagnostic method, proteomic analysis of peripheral blood samples from the endogenous KrasG12D or endogenous KrasG12D plus p16INK4a/Arf knockout models has been performed[5,20]. These studies revealed several molecules whose plasma levels change between PDAC- and mPanIN-bearing mice, or mPanIN and normal mice. The molecules are considered as potential candidates for novel tumor markers that dramatically renovate an early diagnostic strategy of PDAC. Imaging modalities are also important, especially for evaluating tumors in live animals. Progress in ultrasound, CT and MRI for small animals as well as contrast or sensitizing agents will also open the pathways for the development of novel diagnostic strategies in PDAC.

Elucidating underlying mechanisms of PDAC carcinogenesis

Since the constitutively active Kras mutation is observed in almost all PDAC patients, the downstream MAPK and PI3K signals are also activated in these patients. On the other hand, amplification of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene, upstream of Kras, is also frequently found in PDAC[4]. Hedgehog, Notch signal activation and COX-2 overexpression are also clinically observed. This activated signaling is reproduced in the GEM models described above, therefore, inhibition of this signaling may lead to potential therapeutic targets. Inhibition of Hedgehog or Notch signaling has already been reported with significant anti-tumor effects using some GEM models[18,21,22]. The impact of anti-tumor effects (the extent of survival elongation) might be associated with the fundamental mechanisms of PDAC carcinogenesis and progression. Understanding the entire image of intracellular signaling in the GEM PDAC cells and dissecting underlying mechanisms of PDAC formation and progression will allow us to select the most effective combination of targeted molecules or signaling to treat or prevent PDAC carcinogenesis and progression.

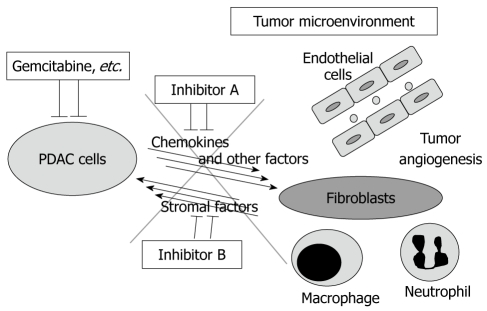

Understanding a tumor microenvironment and its contribution to PDAC progression

Stromal expansion and marked fibrosis is the primary feature of PDAC tissue, which suggests that tumor-stromal interactions might be associated with the extent of biological malignancy of PDAC. Thus, we screened for secreted factors from PDAC cells into the tumor microenvironment using the endogenous KrasG12D expression plus Tgfbr2 knockout model and found that several CXC chemokines are much more highly produced and secreted by the PDAC cells compared with the mPanIN cells. The CXC chemokines mainly affect the receptor CXCR2 in the stromal fibroblasts, rather than the PDAC cells autonomously, to induce connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) expression. CTGF strongly promotes fibrosis and tumor angiogenesis, resulting in tumor progression. Moreover, treating the mice with a CXCR2 inhibitor demonstrates anti-tumor effects and prolongs survival significantly (manuscript in submission). Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling described above also reduces the stromal volume significantly and modulates tumor vasculature[18]. Previously, chemotherapies have been developed to target only cancer cells, however, blocking tumor-stromal interactions and modulating the tumor microenvironment, including angiogenic components and/or inflammatory/immune cell regulation, can have a synergistic therapeutic effect in combination with conventional chemotherapies (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Tumor-stromal interaction as a therapeutic target of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) tissue, PDAC cells and stromal cells are interacting with each other by certain factors including chemokines, which might have tumor-promoting effects. The tumor microenvironment contains, for example, fibroblasts, macrophages, neutrophils and vascular endothelial cells. The combination of conventional chemo reagents (e.g. gemcitabine) and the inhibition of the tumor-stromal interaction might be a more effective therapeutic strategy for PDAC.

Approaching the cell of origin for PDAC

In the multi-step carcinogenesis hypothesis, as shown Figure 1, the cell of origin for PDAC has been considered as a normal pancreatic duct cell. This seems to be a clinical consensus, since mutations of Kras, p16INK4a and p53, for example, have not been detected in the acinar cells closely located to cancer cells in the clinical samples.

The GEM models described above generally use the PDX1 or Ptf1a promoter, which results in genetic alterations occurring in all pancreatic epithelial cells. Therefore, these models cannot answer whether the duct cells are really the only cells of origin for PDAC or not (Figure 2). More recently, GEM models that have genetic alterations in more localized cell lineages and/or inducible alterations at the adult stages have been reported, which allowed us to approach the cell of origin for PDAC. “Inducible” GEM models contain the tamoxifen-inducible CreER system or tetracycline-inducible Tet-ON/OFF system.

Recent reports revealed that endogenous KrasG12D expression in acinar cell lineages at the adult stages, using the acinar cell marker Elastase I or Mist1 gene promoter, demonstrate mPanIN formation, which indicates that PDAC could be derived from acinar cells in mouse models[23,24]. Another report describes Kras activation in acinar cells or insulin-producing endocrine cells at the adult stage, followed by pancreatitis using the chemical reagent caerulein, frequently demonstrated mPanIN, which indicates that inflammation could promote transdifferentiation from acinar or islet cells to duct-like cells and also promote carcinogenesis in mouse models[25,26]. These results suggest that PDAC could be derived from acinar and islet cells in mouse models. However, mature acinar and islet cells seemed refractory to mPanIN formation and required inflammation[25,26]. To date, pancreatic duct cell-specific GEM models have not been established. The duct-specific “inducible” GEM model is the closest approximation of the human PDAC carcinogenesis hypothesis and will give us a chance to understand PDAC completely. On the other hand, the Nestin-cre; LSL-KrasG12D model also shows mPanIN formation, which indicates that nestin-positive cells could be the cells of origin for PDAC[27]. Nestin is an intermediate filament protein predominantly expressed in stem cells of the central nervous system and is also known to be expressed in progenitor cells of the exocrine pancreas epithelium. Taken together, PDAC might be derived from certain immature cell populations that can differentiate into the three mature lineages.

GEM model-specific differences compared to human PDAC

As described above, use of GEM models has made significant advances, yet there still is room for refinement and discrepancies with human conditions need to be elucidated.

There are GEM model-specific differences compared to human PDAC, which were also documented in the consensus report of GEM models of PDAC. The most prominent difference might be multi-focal tumorigenesis in GEM models. In humans, tumors usually emerge as a single neoplastic focus, whereas GEM models show multi-focal tumor progression, which results in lobular tumor formation occupying the entire pancreas. Therefore, tumor margins are difficult to delineate and tumor volume might be analyzed as the size of entire (tumor-occupied) pancreas.

In GEM models, acinar-ductal metaplasia and the ductular-insular complex (duct formation inside or in the periphery of the islet) are frequently observed, especially in the models using the PDX1 or Ptf1a promoter[10]. In humans, these are occasionally observed and are frequently non-neoplastic; however, in GEM models, most of them should be considered as neoplastic lesions on the way to cancer progression. In the GEM models using the PDX1 or Ptf1a promoter-cre, any epithelial cells can have Kras activation, every acinar cell demonstrates acinar-ductal metaplasia and every islet shows the ductular-insular complex, all of which might progress into PanIN-like ductal neoplasia and eventually into invasive PDAC. Since acinar cells occupy nearly 80% of the normal pancreas, acinar-ductal metaplasia is observed abundantly in GEM models (especially in the endogenous KrasG12D plus TSG inactivation models), which might also be one of the greated differences in GEM models compared to human PDAC. The consensus report noted that the acinar-ductal metaplasia should be distinguished from duct-derived mPanIN lesions, however, in a few weeks, acinar-ductal metaplasia rapidly progresses into PanIN-like lesions, which are already difficult to distinguish from duct-derived mPanIN lesions. The final appearance of invasive PDAC recapitulates human disease, suggesting that acinar-ductal metaplasia, which definitely progresses into PDAC in the GEM models, might also contribute to PDAC formation in humans.

CONCLUSION

Recent progress in the use of GEM models can be called a breakthrough, although there are still limitations and differences compared to human PDAC. Analyzing the GEM models, with knowledge of the advances and limitations, will allow us to understand the entire image of PDAC and to develop effective therapies, diagnosis and prevention based on the underlying mechanisms of PDAC carcinogenesis and progression. Using GEM models and combining bench and bedside closely together might provide a breakthrough in the PDAC field and ultimately overcome the most lethal cancer.

Acknowledgments

I thank Anna Chytil, Mary E Aakre and Harold L Moses for lots of comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Paul J Higgins, PhD, Professor and Director, Center for Cell Biology and Cancer Research, Head, Molecular Oncology Program, Albany Medical College, Mail Code 165, Room MS-341, Albany Medical Collge, 47 New Scotland Avenue, Albany, NY 12208, United States; Wei-Hong Wang, MD, PhD, Professor, Departmant of Gastroenterology, First Hospital, Peking University, No.8, Xishiku street, West District, Beijing 100034, China

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Lutze M E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Matsuno S, Egawa S, Fukuyama S, Motoi F, Sunamura M, Isaji S, Imaizumi T, Okada S, Kato H, Suda K, et al. Pancreatic Cancer Registry in Japan: 20 years of experience. Pancreas. 2004;28:219–230. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200404000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuba T, Qiu D, Kurosawa M, Lin Y, Inaba Y, Kikuchi S, Yagyu K, Motohashi Y, Tamakoshi A. Overview of epidemiology of bile duct and gallbladder cancer focusing on the JACC Study. J Epidemiol. 2005;15 Suppl 2:S150–S156. doi: 10.2188/jea.15.S150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:897–909. doi: 10.1038/nrc949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, Ross S, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Hitt BA, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguirre AJ, Bardeesy N, Sinha M, Lopez L, Tuveson DA, Horner J, Redston MS, DePinho RA. Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3112–3126. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, Combs C, Deramaudt TB, Hruban RH, Rustgi AK, Chang S, Tuveson DA. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardeesy N, Aguirre AJ, Chu GC, Cheng KH, Lopez LV, Hezel AF, Feng B, Brennan C, Weissleder R, Mahmood U, et al. Both p16(Ink4a) and the p19(Arf)-p53 pathway constrain progression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5947–5952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601273103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ijichi H, Chytil A, Gorska AE, Aakre ME, Fujitani Y, Fujitani S, Wright CV, Moses HL. Aggressive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice caused by pancreas-specific blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cooperation with active Kras expression. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3147–3160. doi: 10.1101/gad.1475506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hruban RH, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, Anver MR, Biankin AV, Boivin GP, Furth EE, Furukawa T, Klein A, Klimstra DS, et al. Pathology of genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic exocrine cancer: consensus report and recommendations. Cancer Res. 2006;66:95–106. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derynck R, Miyazono K. The TGF-beta family. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn SA, Schutte M, Hoque AT, Moskaluk CA, da Costa LT, Rozenblum E, Weinstein CL, Fischer A, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, et al. DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science. 1996;271:350–353. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goggins M, Shekher M, Turnacioglu K, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, Kern SE. Genetic alterations of the transforming growth factor beta receptor genes in pancreatic and biliary adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5329–5332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venkatasubbarao K, Ahmed MM, Mohiuddin M, Swiderski C, Lee E, Gower WR, Salhab KF, McGrath P, Strodel W, Freeman JW. Differential expression of transforming growth factor beta receptors in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bardeesy N, Cheng KH, Berger JH, Chu GC, Pahler J, Olson P, Hezel AF, Horner J, Lauwers GY, Hanahan D, et al. Smad4 is dispensable for normal pancreas development yet critical in progression and tumor biology of pancreas cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3130–3146. doi: 10.1101/gad.1478706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izeradjene K, Combs C, Best M, Gopinathan A, Wagner A, Grady WM, Deng CX, Hruban RH, Adsay NV, Tuveson DA, et al. Kras(G12D) and Smad4/Dpc4 haploinsufficiency cooperate to induce mucinous cystic neoplasms and invasive adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:229–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kojima K, Vickers SM, Adsay NV, Jhala NC, Kim HG, Schoeb TR, Grizzle WE, Klug CA. Inactivation of Smad4 accelerates Kras(G12D)-mediated pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8121–8130. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, Gopinathan A, McIntyre D, Honess D, Madhu B, Goldgraben MA, Caldwell ME, Allard D, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh M, Lima A, Molina R, Hamilton P, Clermont AC, Devasthali V, Thompson JD, Cheng JH, Bou Reslan H, Ho CC, et al. Assessing therapeutic responses in Kras mutant cancers using genetically engineered mouse models. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:585–593. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faca VM, Song KS, Wang H, Zhang Q, Krasnoselsky AL, Newcomb LF, Plentz RR, Gurumurthy S, Redston MS, Pitteri SJ, et al. A mouse to human search for plasma proteome changes associated with pancreatic tumor development. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldmann G, Habbe N, Dhara S, Bisht S, Alvarez H, Fendrich V, Beaty R, Mullendore M, Karikari C, Bardeesy N, et al. Hedgehog inhibition prolongs survival in a genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2008;57:1420–1430. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.148189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plentz R, Park JS, Rhim AD, Abravanel D, Hezel AF, Sharma SV, Gurumurthy S, Deshpande V, Kenific C, Settleman J, et al. Inhibition of gamma-secretase activity inhibits tumor progression in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1741–9.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habbe N, Shi G, Meguid RA, Fendrich V, Esni F, Chen H, Feldmann G, Stoffers DA, Konieczny SF, Leach SD, et al. Spontaneous induction of murine pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (mPanIN) by acinar cell targeting of oncogenic Kras in adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18913–18918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810097105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De La O JP, Emerson LL, Goodman JL, Froebe SC, Illum BE, Curtis AB, Murtaugh LC. Notch and Kras reprogram pancreatic acinar cells to ductal intraepithelial neoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18907–18912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810111105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerra C, Schuhmacher AJ, Cañamero M, Grippo PJ, Verdaguer L, Pérez-Gallego L, Dubus P, Sandgren EP, Barbacid M. Chronic pancreatitis is essential for induction of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by K-Ras oncogenes in adult mice. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gidekel Friedlander SY, Chu GC, Snyder EL, Girnius N, Dibelius G, Crowley D, Vasile E, DePinho RA, Jacks T. Context-dependent transformation of adult pancreatic cells by oncogenic K-Ras. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:379–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrière C, Seeley ES, Goetze T, Longnecker DS, Korc M. The Nestin progenitor lineage is the compartment of origin for pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4437–4442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]