Abstract

Nearly 100 proteins are proposed to be substrates for GSK3, suggesting that this enzyme is a fundamental regulator of almost every process in the cell, in every tissue in the body. However, it is not certain how many of these proposed substrates are regulated by GSK3 in vivo. Clearly, the identification of the physiological functions of GSK3 will be greatly aided by the identification of its bona fide substrates, and the development of GSK3 as a therapeutic target will be highly influenced by this range of actions, hence the need to accurately establish true GSK3 substrates in cells. In this paper the evidence that proposed GSK3 substrates are likely to be physiological targets is assessed, highlighting the key cellular processes that could be modulated by GSK3 activity and inhibition.

1. Introduction

1.1. Why Identify Substrates?

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) was first reported as a glycogen synthase phosphorylating activity in rabbit skeletal muscle (the third to be found, hence GSK3) [1]. GSK3 was later identified as a major tau protein kinase [2]. These substrates immediately focused attention on the importance of GSK3 in glucose metabolism and neurodegeneration, and these remain major areas of GSK3 research. Indeed GSK3 inhibitors, which were initially developed for the treatment of diabetes, are now being investigated for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, as well as many other conditions [3–5]. These therapeutic programmes have arisen directly from substrate identification; however, more recently the multitude of GSK3 substrates proposed in the literature has lessened therapeutic interest in this enzyme. It is therefore of great importance to establish beyond doubt what the physiological targets of this enzyme are, not only to focus therapeutic potential but also establish actual side effects of manipulating GSK3 activity.

1.2. Problems with False Positives

It is reasonably straightforward to implicate a protein as a substrate for a kinase, with evidence ranging from the existence of a consensus phosphorylation sequence in the primary structure of a protein through to regulation of phosphorylation by manipulation of the protein kinase in vivo. Unfortunately, the existence of a consensus sequence is rarely a good predictor of whether a protein will be a substrate of that kinase. Indeed GSK3 target consensus sequences occur in more than half of all known human proteins, most of which are clearly not regulated by GSK3. In addition, phosphorylation in vitro does not always correlate with phosphorylation in vivo, and great care has to be taken to characterise specificity of reagents, initial rate kinetics, and stiochiometry of phosphorylation in vitro and in vivo (see below).

1.3. Criteria for Confidence

Establishing whether a proposed substrate is a true physiological substrate of GSK3 is not straightforward; however, three major criteria, if met, can improve confidence. Firstly, highly purified GSK3 (keeping in mind that many commercial preparations are contaminated with copurifying kinases) should phosphorylate the proposed substrate at a significant rate in vitro (ideally in comparison to other well-characterized substrates), and at residues on the substrate that are phosphorylated in vivo. Secondly, manipulation of GSK3 activity in cells and in vivo (by genetic, pharmacological, and physiological means) should change the phosphorylation of the specific residue targeted by GSK3 in vitro (i.e., GSK3 inhibition should specifically reduce phosphorylation of this site in cells). Finally, a function of the substrate should change in parallel to alteration of phosphorylation and cellular GSK3 activity, while mutation of the GSK3 target residue to alanine should render this function insensitive to GSK3 manipulation.

1.4. Specific Issues Relating to Addressing These Criteria for GSK3 Substrates

Substrate phosphorylation by GSK3 in vitro is complicated by the requirement for prephosphorylation (priming) of most characterised substrates [3, 6]. Purified, bacterially expressed recombinant proteins will contain little phosphate, and thus, if a substrate requires priming, the bacterially expressed protein will not be phosphorylated at an appreciable rate by GSK3 in vitro. Therefore, pre-phosphorylation with an appropriate priming kinase is often required in order to permit subsequent phosphorylation by GSK3. In contrast the existence of this priming mechanism provides the opportunity for additional validation of the protein as a GSK3 substrate. Mutation of the priming residue to alanine, or inhibition of the priming kinase in cells, should prevent subsequent phosphorylation by GSK3.

2. GSK3 Biology

2.1. Gene Structure and Splicing

There are two GSK3 genes (GSK3α and GSK3β) that account for all GSK3 activity in mammals [7]. In addition, the GSK3β mRNA undergoes alternative splicing that produces at least two different protein products GSK3β1 and GSK3β2. The catalytic domain is highly conserved between all GSK3 isoforms, although GSK3β2 has a 13 amino acid insert in this domain [8–11]. GSK3α has an N-terminal glycine rich extension that results in a larger relative molecular weight (51 kDa for GSK3α, and 47 kDa for GSK3β1, GSK3β2 exhibits intermediate mobility upon SDS-PAGE of around 49kDa). GSK3α and GSK3β1 are ubiquitously expressed [7], although relative expression does vary from tissue to tissue (e.g., GSK3β is the predominant isoform in brain [11]). In particular, the GSK3β2 isoform is enriched in neurons although the role of this variant remains unclear [8, 10].

2.2. Unusual Aspects of GSK3 Regulation and Substrate Identification

GSK3 is one of the few protein kinases to be inhibited (as opposed to activated) following stimulation of growth factor receptors. The basal activity of GSK3 in resting cells is relatively high while exposure of cells to growth factors, serum, or insulin reduces the specific activity of GSK3 by between 30 and 70% (dependent on cell type and stimuli) within 10 mins. This appears the case for all GSK3 isoforms. Inhibition is predominantly achieved through phosphorylation at a conserved N-terminal serine (Ser-21 in GSK3α and Ser-9 in GSK3β) [12, 13], and growth factors, promote GSK3 phosphorylation by activation of PKB or p90RSK [14, 15] while insulin inhibits GSK3 mainly through PKB [14]. This indicates that phosphorylation of many bona fide GSK3 substrates should be reduced upon stimulation of cells with serum, growth factors or insulin (Figure 1).

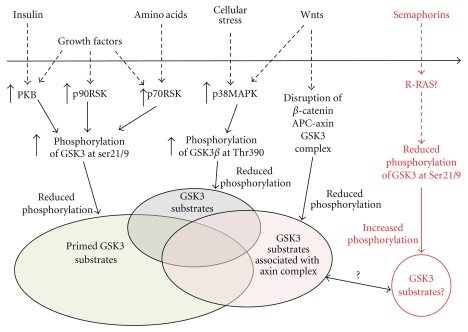

Figure 1.

Different signaling pathways regulate GSK3 activity by different mechanisms, and this could permit differential regulation of GSK3 substrate phosphorylation.

GSK3 is one of only a handful of the 500 mammalian protein kinases that have a strong preference for substrates that are already phosphorylated. Most of the best described GSK3 substrates require pre-phosphorylation at a residue 4 or 5 amino acids C-terminal to the GSK3 target residue (Table 1(a)), a phenomenon referred to as PRIMING. Hence the general GSK3 substrate consensus sequence is Ser/ThrXXX(PhosphoSer/Thr), where X is any residue. However, proposed substrates of GSK3 exist that do not conform to this sequence, having either a priming site much further from the target site, or no apparent requirement for priming at all (Table 1(a)). It is not yet clear how GSK3 recognises unprimed substrates; however, in almost every example of primed substrate the lack of priming reduces phosphorylation by GSK3 by >90%, demonstrating the importance of the phosphorylated residue C-terminal to the target site. Priming also allows the regulation of the GSK3-substrate reaction by N-terminal phosphorylation of GSK3. GSK3 has a phosphate binding pocket which interacts with the substrate at the primed Ser/Thr and positions it for phosphorylation by GSK3. Phosphorylation of Ser-21/9 of GSK3α/β results in the N-terminal domain of GSK3 interacting with its phosphate binding pocket, preventing recognition of primed substrates [6]. This inhibition can be overcome by increasing substrate concentration (at least in vitro), and it suggests that modulation of this aspect of regulation (e.g., by growth factors) would not inhibit phosphorylation of unprimed substrates (Figure 1) [6].

Table 1.

(a) A list of proteins reported to be substrates for GSK3. Where the phosphorylation site, priming mechanism and functional outcome of phosphorylation have been reported, this information is included. ND : not determined. (b) A list of those substrates from (a) that meet at least two out of the three criteria for confidence detailed in Section 1.3 of text, including cellular process likely to be regulated. These are the substrates discussed in more detail in the review.

(a)

| Proposed substrate | Target residue(s) | Priming residue (kinase) | Effect of phosphate | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amyloid precursor protein | Thr743 (APP770) | ND | Regulates trafficking | [27–29] |

| Thr668 (APP695) | ||||

| APC | 1501 | 1505 (CK1) | Regulates degradation | [30, 31] |

| 1503 | 1507 (CK1) | |||

| ATP-citrate lyase | Thr446, Ser450 | Ser454 (unknown) | May regulate activity | [32, 33] |

| Axin | Ser322/Ser326 (putative) | Ser330 | Regulates stability | [34, 35] |

| Axil | Not Determined | Not reported | [36] | |

| BCL-3 | Ser394, | Ser398 (ERK putative) | Regulates degradation | [37] |

| Ser398 (putative) | ||||

| β-catenin | Ser33, 37, Thr41 | Ser45 (CK1) | Regulates degradation | [34] |

| δ-catenin | Thr1078 (putative) | ND | Regulates degradation | [38] |

| C/EBPalpha | Thr222, Thr226 (Questioned) | NONE | NONE | [39, 40] |

| C/EBPbeta | Ser184, Thr179 | Thr188 (MAPK) | Induces DNA binding Reduces DNA binding |

[41] |

| Thr189, Ser185, Ser181, Ser177 | NONE | [42] | ||

| Ci-155 | Ser852, | Ser856 (PKA) | Regulates Degradation | [43, 44] |

| Ser884, 888 | Ser892 (PKA) | |||

| CLASP | Residues between 594 and 614 | Alters affinity for microtubules | [45, 46] | |

| CLASP2 | Ser533 and Ser537 (others) | Ser541 (CDK5) | Affects protein-protein interaction | [47] |

| CRMP2 | Thr509, Thr514, Ser518 | Ser522 (CDK5) | Regulates axon growth, growth cone collapse, and neuronal polarity | [48, 49] |

| CRMP4 | Thr509, Thr514, Ser518 | Ser522 | Regulates axon outgrowth and chromosomal alignment | [48, 50] |

| CREB | Ser129 | Ser133 (PKA) | Kinase activation | [51, 52] |

| CRY2 | Ser553 | Ser557 | Promotes nuclear localisation and degradation | [53] |

| CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase | Multiple, within C-term 52 residues | ? | No effect on activity | [54] |

| Cytidine triphosphate synthetase (CTPS) | Ser571 | Ser575 | Phosphorylation may reduce activity | [55] |

| Cyclin D1 | Thr286 | NONE | Nuclear export and degradation | [56] |

| Questioned | [57] | |||

| Dynamin I | Thr774 | Thr778 (CDK5) | Required for activity dependent bulk endocytosis | [58] |

| Dystrophin | ND | CKII ? | Not reported | [59] |

| eIF2B | Ser535 | Ser539 (DYRK) | Inhibits activity | [60–62] |

| FAK | Ser722 | Ser726 | Inhibits activity | [63] |

| Gephyrin | Ser270 | ND | Modulates GABAergic transmission | [64] |

| Glycogen Synthase | Ser640, 644, 648, 652 | Ser656 (CKII) | Reduces activity | [65, 66] |

| Glucocorticoid receptor | Thr171 (Not conserved in human protein) | NONE | Inhibits GR activity towards some genes | [67] |

| Heat shock factor 1 | Ser303 | Ser307 (MAPK) | Reduces DNA binding | [68] |

| HIF1alpha | Ser551, Thr555, Ser589 | ND | Induces proteosomal degradation | [69] |

| Histone H1.5 | Thr10 | NONE | Coincides with chromosome condensation | [70] |

| hnRNP D | Ser83 | Ser87 | Inhibits transactivation | [71] |

| IRS1 | Ser332 | Ser336 | Promotes degradation | [72] |

| c-jun, Jun B, Jun D | Thr239 | Thr243 | Reduces DNA binding | [73–75] |

| K-casein | ND | ND | Not reported | [76] |

| KRP (telokin) | Ser15 | Unknown site but ERK2 proposed | Not reported | [77] |

| LRP6 | C-terminal PPPT/SP motifs (Ser1490, Thr1572, Ser1590) | NONE | Not clear | [78, 79] |

| MafA | Multiple sites, not identified | ND | Phosphorylation induces MafA degradation and prevents insulin gene expression | [80] |

| MAP1B | Ser1260, Thr1265 | NONE | Regulates stability (lithium promotes degradation) | [81–83] |

| Ser1388 | Ser1392 (DYRK) | |||

| MAP2C | Thr1620, Thr1623 | ND | Reduces microtubule binding | [84] |

| MARK2/PAR1 | Ser212 | NONE | Regulates activity | [85, 86] |

| Mcl1 | Ser140 | Thr144 (JNK) | Permits degradation of Mcl1 in response to UV stress | [87–89] |

| Mdm2 | Ser240, Ser254 | Ser244, Ser258 (CK1) | Promotes activity towards p53, reducing p53 levels | [90] |

| MITF | Ser298 | NONE | Increases transactivation | [91] |

| MLK3 | Ser789, Ser793 | ND | Activates MLK3 Induces apoptosis in PC2 cells | [92] |

| MUC1/DF3 | Ser40 (possible) | Ser44 (possible) | Inhibits formation of b-catenin-E-cadherin complex | [93] |

| c-myb | Thr572 | ND | Not clear | [94, 95] |

| c-myc, L-myc | Thr58, Thr62 (c-myc) | Ser62 (ERK1/2) | Promotes degradation | [96–98] |

| Myocardin | 8 serines in two blocks, Ser455—467 and Ser624—636 | Yes but kinase not reported | Phosphorylation inhibits myocardin induced transcription | [99] |

| αNAC (nascent polypeptide associated complex) | Thr159 | NONE | Induces transactivation, maybe stability | [100] |

| NDRG1 | Thr342, Ser352, Thr362 | Thr346, Thr356, Thr366 (SGK) | Not reported | [101] |

| neurofilament L | Ser502, 506, 603, 666 (M) | ND | Not reported | [102] |

| neurofilament M | Ser493 (H) | [103] (M) | ||

| neurofilament H | [104] (H) | |||

| NFAT | SRR domain | ND | Induces nuclear exclusion, inhibits DNA binding | [105–107] |

| SP-2 domain | PKA or DYRK | |||

| SP-3 domain | PKA | |||

| Ngn2 | 231 and 234 | ND | Facilitates interaction with LIM TFs, involved in motor neuron determination | [108] |

| Notch 1C | ND | Stabilises protein | [109] | |

| Nrf2 | ND | Inhibits activity by nuclear exclusion | [110, 111] | |

| OMA1 | Thr339 | Thr239 (MBK-2) | Induces degradation | [112] |

| p130Rb | Ser948 | Ser952 | Regulates stability | |

| Ser962 | Ser966 | [113] | ||

| Ser982 | Thr986 all CDK putative | |||

| p21 CIP1 | Thr57 | ND | Induces degradation | [114] |

| p27Kip1 | Not fully established | ND | Regulates stability | [115] |

| p53 | Ser33 (GSK3beta only) | Ser37 (DNA-PK) | Increases transcriptional activity | [116] |

| Ser315, Ser376 | ND | Increases cytoplasmic localisation, degradation, inhibits apoptosis | [117] | |

| p65 RelA | Multiple, including Ser468 | ND | Negatively regulates basal activity | [118, 119] |

| PITK | Ser1013 | Ser1017 (CAMKII) | Induces nuclear localization and possibly interaction with PP1C | [120] |

| Polycystin-2 | Ser76 | Ser80 | Regulates localisation, enhanced in polycystic kidney disease | [121] |

| PSF- Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein-associated-splicing factor | Thr687 | NONE | Regulates interaction with TRAP-150, and CD45 alternative splicing in T cells | [122] |

| Presenilin-1 | Ser397, Ser401 | NONE | Reduces interaction with β-catenin | [123] |

| Ser353, Ser357 | [124] | |||

| Protein phosphatase1 G-subunit | Ser38, 42 (human) | Ser46 (PKA or p90RSK) | Not clear | [125] |

| Protein phosphatase inhibitor 2 | Thr72 | Ser86 (CKII) | Inhibits inhibitor, thereby activating PP1 | [11, 126, 127] |

| PTEN | Ser362, Thr366 | Ser370 (CK2) | Possibly inhibits activity | [128] |

| Pyruvate Dehydrogenase | ND | Inhibits activity | [129] | |

| RCN1 (yeast calcineurn regulatory protein-calcipressin) | Ser113 | Ser117 | Regulates cacineurin signaling | [130] |

| SC35 | ND | Probably | Redistributes this splicing factor | [131] |

| SKN-1 | Ser393, (maybe Ser389 and Thr385) | Ser397 | Inhibits activity | [132] |

| SMAD3 | Thr66 | ND | Regulates stability | [133] |

| Snail | Ser97, 101, 108, 112, 116, 120 | ND | Regulates degradation and nuclear exclusion (antitumourogenic) | [134] |

| SREBP1c (processed fragment) | Thr426, Ser430 | ND | Promotes degradation | [135] |

| Stathmin | Ser31 | ND | Slight induction of depolymerisation of microtubules | [136] |

| Tau | Multiple including Ser208, Thr231, 235 | Thr212 (DYRK) | Some phosphorylation sites regulate microtubule binding | [62, 137, 138] |

| Ser396 | ||||

| Ser404, others? | [139] | |||

| TSC2 | Ser1341, Ser1337 | Ser1345 (AMPK) | Activates TSC2 to inhibit mTOR | [140] |

| VDAC | Thr51 | Thr55 | Modulates interaction with HKII in mitochondrial membrane | [141] |

| von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) | Ser68 | Ser72 (CKI) | Regulation of MT stabilization | [142] |

| Zcchc8 | Thr492 | ND | ND | [143] |

(b)

| Proposed substrate | Effect of phosphate | Cellular process |

|---|---|---|

| Amyloid precursor protein | Regulates Trafficking | Neurobiology |

| BCL-3 | Degradation | Growth and Survival |

| β-catenin | Degradation | Development |

| C/EBPbeta | Regulates DNA binding | Endocrine control |

| Growth and survival | ||

| Ci-155 | Regulates degradation | Development |

| CLASP2 | Affects protein-protein interaction | Neurobiology/cell migration |

| CRMP2 | Regulates axon growth, growth cone collapse and neuronal polarity. | Neurobiology |

| CRMP4 | Regulates axon outgrowth | Neurobiology |

| CREB | Activation | Neurobiology |

| Endocrine control | ||

| Cytidine triphosphate synthetase (CTPS) | Reduces activity | Cell growth |

| Dynamin I | Required for activity dependent bulk endocytosis | Neurobiology |

| eIF2B | Inhibits activity | Cell Growth |

| FAK | Inhibits activity | Growth and Survival |

| Glycogen Synthase | Reduces activity | Endocrine control |

| heat shock factor 1 | Reduces DNA binding | Growth and Survival |

| HIF1alpha | Induces proteosomal degradation | Growth and Survival |

| Histone H1.5 | Coincides with chromosome condensation | Cell division |

| IRS1 | Promotes degradation | Endocrine control |

| c-jun, Jun B, Jun D | Reduces DNA binding | Growth and survival |

| MAP1B | Regulates stability | Neurobiology |

| MAP 2C | Reduces microtubule binding | Neurobiology |

| MARK2/PAR1 | Regulates activity | Neurobiology |

| Mcl1 | Permits degradation of Mcl1 in response to UV stress | Growth and survival |

| Mdm2 | Promotes activity towards p53, reduces p53 levels | Growth and survival |

| c-myc, L-myc | Promotes degradation | Growth and survival |

| Myocardin | Inhibits myocardin induced transcription | Development |

| NDRG1 | Not reported | Ion control |

| NFAT | Regulates nuclear exclusion, Inhibits DNA binding | Immunology |

| Ngn2 | Facilitates interaction with LIM TFs, for motor neuron determination | Development |

| p130Rb | Promotes stability. | Growth and survival |

| protein phosphatase 1 G-subunit | Not clear | Endocrine control |

| protein phosphatase inhibitor 2 | Inhibits inhibitor, thereby activating PP1 | Endocrine control |

| Polycystin-2 | Regulates localisation, induced in polycystic kidney disease | Growth and survival |

| PTEN | Inhibits activity | Growth and survival |

| RCN1 (yeast calcineurn regulatory protein) | Stimulates cacineurin signaling | Growth and survival |

| Neurobiology | ||

| Snail | Induces degradation and nuclear exclusion (antitumourogenic) | Growth and survival |

| Tau | Modulates interaction with tubulin Increased in AD | Neurobiology |

| VDAC | Modulates interaction with HKII in mitochondrial membrane | Growth and survival |

| von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) | Regulation of MT stabilization | Neurobiology |

The semaphorin family of axonal guidance molecules induces GSK3 activity at the leading edge of migrating cells through the dephosphorylation of this N-terminal serine [16, 17]. The mechanism is not fully elucidated but involves activation of R-RAS(GAP) and the subsequent suppression of R-Ras [17]. Again this mechanism of regulation suggests that semaphorins regulate only primed substrates of GSK3.

There are reports that GSK3 activity can be induced by specific extracellular stimuli, and this regulation appears to be particularly apparent in the brain [18]. In theory, induction of phosphorylation at Tyr216 (GSK3β1 numbering) is a mechanism for regulating GSK3 activity [18]. Phosphorylation of this tyrosine is crucial for proper folding of the catalytic domain, and it occurs through autophosphorylation during synthesis of the GSK3 polypeptide [19]. As such Tyr216 is likely to be constitutively phosphorylated to high stoichiometry [20], yet an increase in Tyr216 phosphorylation was observed in PC12 cells following removal of NGF (and other apoptotic stimuli), correlating with increased GSK3 activity [18]. However, this observation has subsequently been challenged [20].

Interestingly, regulation of GSK3 by the canonical Wnt signaling pathway does not involve N-terminal or tyrosine phosphorylation [21]. Wnt regulation of GSK3 is most likely achieved through disruption of a specific complex including Axin/APC/β-catenin and GSK3 (Figure 1). This mechanism has been well characterized for the phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin, and could in theory be as effective at inhibiting phosphorylation of unprimed substrates. In addition, this pathway demonstrates the existence of separate intracellular pools of GSK3, since insulin will not regulate β-catenin activity and Wnts will not regulate glycogen synthesis [22–24]. Hence compartmentalization of GSK3 allows differential upstream regulation but also enables differential downstream substrate phosphorylation (Figure 1).

Finally, the stress-induced p38MAPK family can phosphorylate Thr390 of GSK3β reducing its activity, and this also contributes to canonical Wnt signaling and regulation of substrates such as β-catenin [25, 26]. This is of particular interest as the residue is not conserved in GSK3α and thus provides a potential GSK3 isoform specific regulation.

3. GSK3 Substrates: Physiological Function and Therapeutic Potential

3.1. Genetic Studies to Elucidate GSK3 Function

Deletion of the GSK3β gene in mice is lethal [144, 145], while GSK3β heterozygous (+/−) mice exhibit reduced aggression, increased anxiety, reduced exploratory activity, poor memory consolidation, and reduced responsiveness to amphetamine [146–148]. Conversely, overexpression of GSK3β in brain results in hyperactivity and mania [149].

Mice lacking GSK3α are viable and relatively normal [150], exhibiting a small improvement in insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance. Mice lacking GSK3α specifically in neurons display reduced aggression and exploratory activity, decreased locomotion, impaired co-ordination, and a deficit in fear conditioning [151]. The differential phenotypes between isoform deletions suggest nonredundant functions of the GSK3 genes in the brain, while the overlapping behavioural problems between GSK3α neuronal knockout (KO) and GSK3β (+/−) mice suggest some common substrates.

Deleting both GSK3 isoforms in the brain induces self-renewal of neuronal progenitor cells, but reduced neurogenesis [152]. Mutation of the N-terminal regulatory serine to alanine renders GSK3 insensitive to growth factor regulation. GSK3α/β double knockin mice (where both isoforms are replaced by mutant proteins with Ser to Ala alterations at Ser21 and Ser9, resp., [22]) show impairment of neuronal precursor cell proliferation [153]. Taken together, these data indicate that proper regulation of expression and activity of GSK3 is required for maturation of these cells during mammalian brain development. However, the substrates that mediate this function are unknown. Conversely, overexpression of GSK3β in the brain (using the Thy1 promoter) induces microcephaly [154, 155].

Alternative splicing of GSK3β between exon 8 and 9 gives rise to two main variants of this isoform [8]. GSK3β1 is the most widely expressed; however GSK3β2 (including a 13 amino acid insert due to use of exon 8A) is highly enriched within the brain [8]. The inserted sequence lies within the kinase domain, and there is preliminary evidence that these variants exhibit differential substrate specificity [8, 9, 11]. However, how this impinges on GSK3 function remains unclear.

Therefore, although genetic ablation of one or both genes for GSK3 has provided clues as to the cellular processes that require GSK3 activity, it has not yet established the molecular connections responsible for these phenotypes. Table 1(a) lists more than 100 sequences within 77 proteins that are proposed as substrates of GSK3, virtually none of these have been examined in tissue from GSK3 null animals. Table 1(b) lists the substrates from Table 1(a) where at least 2 of the 3 criteria for confidence (as detailed in Section 1.3) have been met. This represents around half of the sites and proteins listed in Table 1a (all three criteria have been met for very few substrates) and covers a variety of cellular processes, as detailed below.

Interestingly, only four of the proteins listed in Table 1(b) appear to have no requirement for priming (C/EBPbeta, histone H1.5, MARK2, and tau (at some sites)). Thus, by far the majority of the well-characterized substrates require priming.

3.2. GSK3 in Energy Homeostasis

Glucose is a vital nutrient for most mammalian cells. It is obtained by ingestion of food but can be generated endogenously in the liver by glycogenolysis or gluconeogenesis (from amino acids or glycerol) during periods of fasting. These processes ensure there is a constant supply of glucose in the blood (around 5 mM), available to all cells in the body. However, high glucose is relatively toxic to tissues and blood proteins, hence there are complex endocrine mechanisms to prevent hyperglycemia (diabetes). Insulin is released from pancreatic β-cells in response to postprandial rising blood glucose, and this hormone combats hyperglycemia by acting on liver, muscle, and fat tissue, promoting glucose storage in the form of glycogen, turning off hepatic gluconeogenesis and promoting adipogenesis (for review see [156, 157]).

Loss of pancreatic β-cells is the main cause of Type 1 diabetes, as these cells are the only endogenous source of insulin. Treatment with exogenous insulin at appropriate times is relatively effective in restoring glucose control in this condition. In contrast, Type 2 diabetes (accounting for about 90% of diabetes) is less well defined, and includes defects in glucose sensing, insulin secretion, and loss of insulin action (insulin resistance). Hence treatment with exogenous insulin is less effective, and alternative approaches, such as insulin sensitizing agents (e.g., metformin) are used to combat this condition. GSK3, as its name indicates, has long been associated with insulin regulation of glucose homeostasis and as such has been investigated as a therapeutic target in diabetes.

3.2.1. Glycogen Synthase

Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase by GSK3 reduces glycogen synthesis (glucose storage) in muscle. Glycogen synthase is constitutively phosphorylated by CKII at Ser656, providing initial priming for a series of phosphorylation events by GSK3 (652, 648, 644, 640), each additional phosphorylation in turn adding to the inhibition of glycogen synthase activity [1, 66]. This places GSK3 in the pathway from insulin, to glucose disposal. More recently, inhibition of GSK3 in cells [158] and in vivo [159] was found to reduce hepatic gluconeogenesis, although the GSK3 substrate responsible for this action remains elusive. Clearly, as GSK3 is inhibited in cells treated with insulin pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 should mirror many of the natural actions of insulin including reducing glucose production and enhancing glucose storage to combat hyperglycemia. Therefore many major pharmaceutical companies have generated potent and selective GSK3 inhibitors as potential antidiabetes therapeutics and initial data in animal models suggests efficacy in glucose lowering [159, 160].

3.2.2. CREB and C/EBP

GSK3 also regulates a number of transcription factors with links to endocrine action, in particular the transcription factors C/EBPβ and CREB, which are responsive to hormones that stimulate the generation of the second messenger cAMP [161, 162] or to the fasting signal glucocorticoids [163]. The regulation of C/EBPβ by GSK3 appears complex, with priming of Thr188 by ERK allowing GSK3 to phosphorylate C/EBPβ and induce its DNA binding [41]. Conversely, unprimed phosphorylation of distinct residues (albeit in the same domain of the protein) is reported to reduce DNA binding [42], so it remains unclear which mechanism is invoked upon regulation of GSK3 in vivo.

Meanwhile, phosphorylation of CREB at Ser129 by GSK3, following priming by PKA at Ser133, is reported to induce CREB transcriptional activity [51, 52] however the regulation of key CREB-dependent genes by GSK3 in cells or animals remains poorly studied.

In summary, there is little direct evidence that GSK3 regulates these transcription factors as part of physiological responses to the hormones of glucose homeostasis.

3.2.3. Insulin Signaling

GSK3 can regulate cellular phosphorylation indirectly by targeting protein phosphatase-1 (PP1), a key regulator of insulin signaling. GSK3 phosphorylation of Inhibitor-2, a regulator of PP1, antagonizes Inhibitor-2 function thereby inducing PP1 activity [11, 126, 127]. In this way, inhibition of GSK3 would be predicted to reduce PP1 activity and indirectly induce phosphorylation of cellular proteins (and conversely overexpression of GSK3 may reduce phosphorylation of some proteins). In addition GSK3 phosphorylates the glycogen binding subunit of protein phosphatase-1 (PP1G) following priming by PKA at Ser46, although the effect of phosphorylation on PP1G function is unclear [125]. These were two of the first substrates identified for GSK3 following closely behind glycogen synthase, and hence added to the evidence that GSK3 played a key role in regulation of glycogen metabolism in muscle. More recently GSK3 has been implicated in a negative feedback regulation of insulin signaling, and hence potentially contributing to the insulin resistance found in diabetes as well as other diseases such as polycystic ovarian syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. GSK3 phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1 at Ser332, following priming at Ser336, thereby promoting its degradation [72]. IRS-1 is a key target for the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase [164], hence loss of IRS1 due to aberrant activation of GSK3 would reduce the insulin signaling capacity of the cell.

In summary, GSK3 inhibition has the potential to enhance cellular insulin sensitivity (stabilize IRS1), reduce hepatic glucose production (target unknown) and promote glucose disposal (glycogen synthase), all beneficial to the diabetic patient. Consistent with the molecular predictions, inhibition of GSK3 in an animal model of diabetes reduces the associated hyperglycemia and insulin resistance [159]. However, the ever-growing list of potential GSK3 substrates involved in cell growth (see next section) has dampened the enthusiasm for using GSK3 inhibition as a treatment for a chronic condition such as diabetes (where patients may require treatment for 10–50 years).

3.3. GSK3 in Growth and Survival

The numerous proposed substrates of GSK3 with a role in the control of cell growth and survival suggests that pharmacological manipulation of GSK3 activity may increase the risk of abnormal cell growth or differentiation; however many of these proposed substrates remain poorly characterised.

3.3.1. Bcl3

Bcl3 is a member of the IϰB family of NFϰB inhibitors that induces transcription of many genes including cyclin D1 [165]. Constitutive Bcl3 phosphorylation at Ser394 by GSK3 (possibly following priming at Ser398) promotes its degradation [37]. Bcl3 expression is upregulated in many tumours, thus GSK3 is proposed to keep the oncogenic potential of Bcl3 in check.

3.3.2. c-Jun

The proto-oncogene c-Jun is one of the components of AP-1, a transcription factor complex believed to play key roles in cell proliferation, survival and death (reviewed in [166, 167]). It is regulated by multisite phosphorylation including N-terminal phosphorylation which induces its transcriptional activity, and C-terminal phosphorylation which inhibits its binding to DNA. JNK and ERK phosphorylate the N-terminal sites on c-jun to activate it, while GSK3 phosphorylates Thr-239 to inhibit c-jun activity (following priming of Ser243 by an unknown kinase) [73–75]. Hence GSK3 inhibition would potentially enhance the action of this oncogene.

3.3.3. Mcl-1

Mcl-1 is an antiapoptotic member of the Bcl2 family that is essential for embryonic development and for the survival of hematopoietic cells. Mcl-1 plays an important role in the sensitization of cells to apoptotic signals Exposure to UV radiation causes the rapid degradation of Mcl-1 and the release of proapoptotic partner proteins (e.g., Bim). In response to UV (and other cell stress) JNK phosphorylates Mcl-1 at Thr144 priming it for subsequent phosphorylation by GSK3 at Ser140. JNK and GSK3 activities are required for degradation of Mcl-1 in response to stress [87–89], so GSK3 inhibition would antagonize this apoptotic mechanism.

3.3.4. Mdm2

The Mdm2 oncoprotein regulates abundance and activity of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Phosphorylation of Mdm2 at several contiguous residues within the central conserved domain is key to this function. GSK3 phosphorylates Mdm2 in the central domain both in vitro and in vivo [90]. Inhibition of GSK3 prevents p53 degradation in an Mdm2-dependent manner, and expression of a S9A GSK3 mutant reduces the accumulation of p53 and induction of its target p21(WAF-1). Therefore inhibition of GSK3 could promote hypophosphorylation of Mdm2 resulting in stabilization of the tumour suppressor p53 [90].

3.3.5. c-Myc

c-Myc is an immediate early gene controlling cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. It can be primed at Ser62 by ERK2 (extracellular signal-related protein kinase 2), allowing phosphorylation at Thr58 by GSK3, which targets c-Myc for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis [96]. Thus mitogen-induced dephosphorylation of c-Myc at Thr58 may increase its half-life, similar to the situation proposed for (but less well characterized for) cyclin D1 [168]. Thr58 is mutated in all v-Myc proteins, and restoration of the wild-type threonine severely inhibits transforming potential [169]. Moreover, the T62A mutant c-Myc (GSK3 resistant) potentiates focus formation [170]. There is good evidence that GSK3 is responsible for Thr58 phosphorylation in vivo. Firstly, CT99021, a selective GSK3 inhibitor, reduces c-Myc phosphorylation at Thr58 in cells, secondly, c-Myc protein is elevated in GSK3β KO brain, and finally, overexpression of GSK3β in HEK293 cells increases Thr58 phosphorylation [11]. This suggests that GSK3 inhibition in vivo would enhance the stability of this oncogenic factor.

Paradoxically, mutation of Ser62 to Ala is reported to destabilize c-Myc, suggesting that the phosphorylation of this residue may stabilize c-Myc and as such play an opposing role to the phosphorylation of Thr58. Thus the regulation of c-Myc by serum appears to run a fine line between stabilization and degradation. Activation of PI 3-kinase and ERK by serum will induce Ser62 phosphorylation but inhibit GSK3 and decrease phosphorylation of Thr58. This is consistent with the observation that the half-life of c-Myc increases in response to serum [171]. One presumes that upon serum withdrawal, GSK3 activity increases and phosphorylation of the already primed c-Myc enhances the rate of its degradation [96–98].

3.3.6. p130 Retinoblastoma Protein (Rb)

The interaction of p130Rb with E2F transcription factors results in active repression of E2F-dependent genes (key for DNA synthesis and cell cycle progression as well as differentiation and DNA damage checkpoints) [172, 173]. The p130Rb protein level is elevated in quiescent cells and decreased in proliferating cells. GSK3 phosphorylates p130Rb during G0, enhancing stability of p130Rb, but does not affect its ability to interact with E2F4 or cyclins [113]. It is conceivable that GSK3 inhibition would thus swing the balance towards p130Rb degradation and cell proliferation.

3.3.7. PTEN

The PTEN tumor suppressor is a phosphatidylinositol D3-phosphatase that antagonizes the action of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3K) and negatively regulates cell growth and survival. CK2 phosphorylates PTEN at Ser370 and Ser385 enabling GSK3 to phosphorylate Ser362 and Thr366 [128]. Expression of T366A mutant PTEN reduces downstream PI 3K signaling to a higher extent than wild-type PTEN suggesting that GSK3 inhibits PTEN activity. In neuronal cell lines-leptin regulates PTEN phosphorylation at Ser362 and Thr366 rather than inducing PI 3K activity in order to control downstream PI 3K signaling [174]. Pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 would therefore be predicted to antagonise the PI 3K signaling pathway and reduce cell growth potential, although this remains to be conclusively proven [128]. How this action of GSK3 interacts with that proposed for regulation of IRS1 described above (where PI 3K signaling would be enhanced by GSK3 inhibition) is also unclear.

3.3.8. Heat Shock Factor (HSF)-1

Mammalian heat shock genes are regulated at the transcriptional level by heat shock factor-1 (HSF-1), a sequence-specific transcription factor. HSF-1 exists as a latent cytoplasmic phosphoprotein but is transformed by dephosphorylation to a nuclear protein that controls the transcription of heat shock genes [175]. HSF-1 is phosphorylated by GSK3 at Ser303, following priming of Ser307 by ERK [68]. GSK3 thus represses the activity of HSF-1, and in a manner reminiscent of c-Myc regulation (Section 3.3.5above) serum induction of ERK will prime HSF-1 at a time where GSK3 activity is low, presumably to permit a rapid relocalisation of HSF-1 following reduction in ERK signaling. Inhibition of GSK3 would thus be expected to enhance the production of heat shock proteins.

3.3.9. Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription Factor (HIF) 1α

HIF-1α is a transcription factor that is vital for the cellular response to hypoxia; however it also responds to growth factors and hormones following activation of PI 3K signaling [176]. The inhibition or depletion of GSK3 induces HIF-1α expression whereas the overexpression of GSK3 results in the opposite. These effects are mediated through phosphorylation of three serines in the oxygen-dependent degradation domain of HIF-1α, and degradation occurs in a VHL-independent manner [69]. Thus, phosphorylation of HIF-1α by GSK3 is proposed to reduce HIF-1α stability, and GSK3 inhibition (physiologically or pharmacologically) would then promote the action of this transcription factor and alter oxygen sensing and cell growth.

3.3.10. Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2B (eIF2B)

eIF2B is a small G-protein that catalyses the exchange of guanine nucleotides on eIF2, an important regulatory step in the initiation of mRNA translation. GSK3 phosphorylates Ser535 of eIF2B after a priming phosphorylation by DYRK at Ser539 [60–62]. Phosphorylation of these residues inhibits eIF2B thereby reducing translation, and as such GSK3 inhibition could enhance protein synthesis and cell growth.

3.3.11. Polycistin 2 (PC2)

Polycystin-2 (PC2) is mutated in 15% of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). It is a nonselective Ca2+-permeable cation channel thought to function at both the cell surface and ER. GSK3 phosphorylates Ser76 of PC2 in vitro and the consensus recognition sequence for GSK3 (Ser76/Ser80) is evolutionarily conserved down to lower vertebrates [121]. Inhibition of GSK3 redistributes PC2 from the lateral plasma membrane pool into an intracellular compartment in MDCK cells without a change in primary cilia localization [121]. Hence, it appears that the surface localization of PC2 is regulated by phosphorylation by GSK3, and this contributes to the maintenance of normal glomerular and tubular morphology.

3.3.12. Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel (VDAC)

Transformed cells are highly glycolytic and overexpress hexokinase II (HXK II). HXK II binds to the mitochondria through an interaction with VDAC, an abundant outer mitochondrial membrane protein. The binding of HXK II to mitochondria contributes to maintenance of cell viability. Phosphorylation of VDAC by GSK3 prevents binding of HXK II promoting dissociation of HXK II from the mitochondria [141]. Inhibition of PKB potentiates chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity, an effect that is dependent on GSK3 activation (downstream of PKB) as well as the reduced binding of HXK II to the mitochondria [141]. Hence, enhancing GSK3 activity toward VDAC may potentiate the efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutic agents.

3.3.13. Cytidine Triphosphate Synthetase (CTPS)

CTPS catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the de novo synthesis of CTP. Phosphorylation of CTPS1 at Ser571 reduces its activity in vitro, while phosphorylation of Ser571 in cells is antagonised by the presence of serum [55]. Phosphorylation of Ser571 is reduced (with subsequent induction of CTPS1 activity) in cells following incubation with either the GSK3 inhibitor indirubin-3′-monoxime or GSK3β short interfering RNAs [55]. Hence GSK3 directly regulates CTP production through the phosphorylation and inhibition of CTPS.

3.3.14. Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK)

GSK3 can phosphorylate FAK at Ser722 [63]. Meanwhile, S722A mutation or dephosphorylation of Ser722 by PP1 increases FAK kinase activity, and cells expressing the S722A mutant FAK display improved cell spreading and faster migration in wound-healing and trans-well assays. The data proposes that GSK3 is a key regulator of FAK activity during cell spreading and migration (and potentially metastasis).

3.4. GSK3 in Neurobiology

3.4.1. Microtubule Function

Neuronal connections are formed during development by a precise and complex pattern of axonal growth, guidance, and synaptogenesis. To achieve this the cells must continually remodel the cytoskeleton in response to external guidance cues that include the Semaphorins, Wnts, and growth factors (for review see [177–179]). Cytoskeletal reorganisation can be accomplished by control of microtubule dynamics and/or the actin cytoskeleton. Microtubule assembly and stability are regulated in large part by the presence and the phosphorylation status of the microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) [180, 181]. Many of the MAPs are substrates for GSK3.

(1) Tau —

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein encoded by a single gene on chromosome 17 (MAPT). It is found predominantly in cells of neuronal origin and regulates microtubule assembly, a function that is influenced by gene splicing (there are six possible isoforms of tau), as well as by phosphorylation (phospho-tau has lower affinity for microtubules). Hyperphosphorylated tau is the major protein constituent of neurofibrillary tangles, one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease. Around 50 phosphorylation sites have been identified on tau protein, many specifically associated with neurodegenerative disease, and many of these are known to influence its regulation of microtubule assembly. Regulation of Tau phosphorylation in health and disease has been covered extensively in recent reviews [182–185] and is discussed in detail in a separate review within this issue.

(2) Collapsin Response Mediator Proteins (CRMP) —

CRMPs are a family of five structurally homologous tubulin-binding proteins implicated in multiple aspects of neuron development and polarisation [49, 50, 186–192]. CRMP1, 2 and 4 are all substrates for GSK3 in vitro and in vivo [48, 49, 193], being phosphorylated at 3 residues (Ser518, Thr514, and Thr509) by GSK3 subsequent to priming by phosphorylation at Ser522. Priming of CRMP1 and CRMP2 is performed by CDK5 as neither of these phosphorylation events occurs in tissue lacking CDK5, while priming of CRMP4 does not require CDK5 [193]. Phosphorylation of CRMP2 by GSK3 regulates axon growth as well as the number of axons [48, 49, 193], while phosphorylated CRMP2 binds less efficiently to tubulin heterodimers. CRMP2 and CRMP4 are not phosphorylated at 518/514/509 in neurons lacking GSK3β (either genetic or pharmacological ablation) [11, 48], while GSK3β phosphorylates these substrates more avidly than GSK3αin vitro [11]. CRMP2 is more heavily phosphorylated in human cortex from Alzheimer's brain compared to age-matched controls [194], and phosphorylated CRMP2 is found in tangles [195]. Phosphorylation of CRMP4 by GSK3 mediates dendrite development in response to inhibitory ligands such as myelin [50]. The CRMPs are excellent substrates for GSK3 in vitro being phosphorylated at a relatively high rate and stoichiometry compared to other GSK3 substrates, and are completely dependent on priming.

(3) Microtubule-Associated Protein (MAP) 1B —

MAP-1B, a major component of the neuronal cytoskeleton, regulates axonal growth potentially through its ability to bind to and increase the stability of microtubules [196–198]. In contrast to tau, phosphorylated MAP-1B binds to microtubules more avidly than unphosphorylated MAP-1B. Phosphorylated MAP-1B is present mainly in axons while unphosphorylated MAP-1B is present in the cell body and dendrites suggesting localization is regulated by this modification (for review see [199]). Moreover, the level of phosphorylated MAP-1B increases during axonal extension declining to low levels at the end of axonogenesis and a phosphorylated form of MAP-1B is distributed across the axon in a gradient fashion with the highest level at the growth cone [200–202]. GSK3 phosphorylates MAP-1B at Ser1260, Thr1265, and Ser1388, the latter requiring priming at Ser1392 by DYRK. Phosphorylation of these residues stabilizes the MAP-1B as well as contributing to its higher affinity for microtubules [81–83]. GSK3 regulation of MAP1B is a vital link between Wnt-7a signaling and axonal remodeling [81–83].

(4) MAP2C —

The microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) proteins, like MAP-1B and tau, are abundant cytoskeletal components predominantly expressed in neurons. MAP2 is phosphorylated in vitro and in situ by GSK3 at Thr1620 and Thr1623, located in the proline-rich region of MAP2 [84]. Cotransfection of GSK3 and MAP2C in cells promotes phosphorylation of MAP2C, a modification that is sensitive to the presence of lithium chloride (a nonselective inhibitor of GSK3). Additionally, the formation of microtubule bundles, which is observed after transfection with MAP2C, is decreased when GSK3 is co-transfected [84]. Highly phosphorylated MAP2C species are found predominantly unbound to microtubules. These data suggests that GSK3-mediated phosphorylation of MAP2C reduces its binding to microtubules and co-ordinated phosphorylation of MAP2C, tau, and MAP-1B by GSK3 is a major mechanism for regulation of microtubule stability in neurons.

(5) Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) Tumor Suppressor Gene —

Inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene is linked to the development of tumors of the eyes, kidneys, and central nervous system. VHL encodes two gene products, pVHL30 and pVHL19, of which one, pVHL30, associates with microtubules (MTs) to regulate their stability. Phosphorylation of pVHL on Ser68 by GSK3 subsequent to a priming phosphorylation event at Ser72 (mediated in vitro by CKI) regulates the ability of pVHL's to stabilize (but not bind) microtubules [142]. Hence pVHL can be added to the list of GSK3 substrates involved in control of microtubule dynamics.

(6) CLIP-Associating Protein (CLASP) 2 —

Actin and microtubules are coupled structurally and distributed asymmetrically along the front-rear axis of migrating cells. CLIP-associating proteins (CLASPs) accumulate near the ends of microtubules, particularly at the front of migrating cells, to control microtubule dynamics and cytoskeletal coupling. Regional regulation of GSK3 is proposed to regulate the distribution of CLASPs [45–47]. IQGAP1 is an actin-binding protein, as well as a CLASP-binding protein. GSK3β directly phosphorylates CLASP2 at Ser533 and Ser537 within the IQGAP1 binding domain. Phosphorylation of these residues dissociates CLASP2 from IQGAP1 and microtubules [47]. Overexpression of active GSK3β alters the distribution of wild-type CLASP2 on microtubules, but not that of a nonphosphorylatable CLASP2 mutant. CLASP2 phosphorylated by GSK3 does not accumulate near the ends of microtubules. Thus, phosphorylation of CLASP2 by GSK3 controls the regional linkage of microtubules to actin filaments and hence influences cell movement and axonal guidance [47].

3.4.2. Presynaptic Function of GSK3—Dynamin I

GSK3 will phosphorylate the large GTPase dynamin I at Thr774 following priming at Thr778 by CDK5 [58]. The activity of GSK3 is specifically required for activity-dependent bulk endocytosis (ADBE), but not clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Moreover the specific phosphorylation of Ser774 on dynamin I by GSK3 is both necessary and sufficient for ADBE. This demonstrates a role for GSK3 preparing synaptic vesicles for retrieval during elevated neuronal activity [58].

3.4.3. Neurogenesis—Ngn2

The differentiation of neural progenitors (neurogenesis) involves two coordinated steps: the commitment to neuronal fate and the establishment of cell-type identity [203]. As mentioned earlier, loss of both GSK3 genes in the brain induces self-renewal of neuronal progenitor cells, but reduces neurogenesis [152]. Two conserved serine residues on the bHLH factor neurogenin-2 (Ngn2), namely Ser231 and Ser234, are phosphorylated during motor neuron differentiation [108]. This phosphorylation can be carried out by GSK3 in vitro, although it is not clear whether priming is required (either at Ser234 or elsewhere), and phosphorylation facilitates the interaction of Ngn2 with LIM homeodomain transcription factors [108]. In Ngn2 knock-in mice in which these two residues are mutated to alanines (insensitive to GSK3 regulation), motor neuron specification is impaired. Hence, this phosphorylation-dependent cooperativity between Ngn2 and homeodomain transcription factors downstream of GSK3 may contribute to neurogenesis and cell fate decisions in the CNS [108], and could explain at least in part the phenotype of the brain-specific GSK3 KO mouse [152].

3.4.4. GSK3 in Alzheimer's Disease (Tau, APP, CRMP, MARK, and DSCR1)

Phosphorylation of the MAPs, tau and CRMP2, at residues targeted by GSK3, is higher in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease than age-matched controls. Indeed the phosphorylated forms of these proteins are the main protein constituents of neurofibrillary tangles, implicating excessive GSK3-mediated phosphorylation of MAPs in tangle pathology. Interestingly abnormal GSK3 activity has also been linked to amyloid pathology.

The major component of senile plaques (an early and important hallmark of AD) is the beta amyloid peptide, Ab, a 39–43 amino acid fragment derived from proteolysis of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretases [204, 205]. Inhibition of cellular GSK3 by lithium or GSK3β antisense oligonucleotides reduces Ab production in cells without significantly affecting cellular APP levels or APP maturation [28]. In addition, Ab production in the brain of a mouse model of AD is reduced by dosing the animal with lithium [28]. More specifically, GSK3 phosphorylates recombinant APP at Thr743 (numbering for APP 770), although whether this alters processing is not clear [27]. In neurons APP is highly phosphorylated at this site, but Thr743 can be phosphorylated by a number of kinases, including JNK, GSK3, and CDK5. In addition, JNK activity, modulated by GSK3, enhances the traffic of phosphorylated APP to nerve terminals and inhibition of GSK3 and JNK restores calcium oscillations in a hAPP expressing neuronal network [29]. In contrast to the wild-type hAPP, expression of the hAPPT743A mutant in cells does not inhibit calcium oscillations, and the proportion of this mutant APP at the plasma membrane is significantly less than wild-type hAPP. Thus GSK3/JNK phosphorylation controls APP trafficking at the plasma membrane and inhibits neuronal calcium oscillations.

Among the many phosphorylation sites identified in tau, Ser262 is a major site of abnormal phosphorylation in AD brain. One kinase known to phosphorylate this site is MARK2. GSK3 phosphorylates MARK2 in vitro at Ser212, one of two reported phosphorylation sites (Thr208 and Ser212) found in the activation loop of MARK2. Downregulation of either GSK3 or MARK2 by siRNAs suppresses the level of phosphorylation of tau on Ser262 suggesting that GSK3 regulates Ser262 of tau indirectly through phosphorylation and activation of MARK2 [85]; however, this has recently been disputed [86].

Calcineurin is a calcium/calmodulin-activated serine/threonine phosphatase (also known as PP2B). Down syndrome candidate region 1 (DSCR1) is the mammalian homologue of the yeast RCN family (more recently referred to as calsipressins) that directly regulates calcineurin [206]. Calcineurin function is well characterized in yeast, where its expression promotes growth in high calcium environments by dephosphorylation of the Tcn1p transcription factor. It also regulates many facets of apoptosis, memory processes, and skeletal and cardiac muscle growth and differentiation. Hence, by regulating calcineurin, DSCR1 has the potential to influence all of these processes. The DSCR1 gene was isolated from the “Down syndrome candidate region”, and in the brain, DSCR1 is predominantly expressed in neurons within the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, substantia nigra, thalamus, and medulla oblongata. DSCR1 mRNA levels are three times higher in patients with extensive neurofibrillary tangles (hallmark of AD) compared to controls [207]. Similarly, postmortem brain samples from Down syndrome patients (who develop AD pathology) also have DSCR1 mRNA levels higher than controls. In addition, exposure of cultured cells to the Ab(1–42) peptide increases expression of DSCR1 [207]. Paradoxically, while increasing Rcn1 expression can inhibit calcineurin signaling in fungal and animal cells, endogenous levels can actually stimulate calcineurin signaling in yeast [130]. The stimulatory effect of yeast Rcn1 requires phosphorylation of a serine residue (conserved in mammals) by a yeast homologue of GSK3 (Mck1). Mutation of this serine in yeast Rcn1, and the human homologue DSCR1, abolishes the stimulatory effects of Rcn1/DSCR1 on calcineurin signaling. Therefore, in healthy cells, GSK3 may switch Rcn1/DSCR1 between stimulatory and inhibitory forms [130]. Whether abnormal GSK3 regulation of DSCR1 contributes to the pathophysiology of AD or Downs syndrome remains unknown.

3.5. GSK3 in Development

3.5.1. Wnt Signaling-Beta Catenin

One of the best-described cellular functions of GSK3 is the regulation of canonical Wnt signaling. This topic is reviewed in excellent detail elsewhere [21, 208–210] and so will not be covered in depth in this review. In short, GSK3β associates with a large protein complex that includes adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), axin, and β-catenin. All three of these proteins are proposed as GSK3 substrates and phosphorylation of each is proposed to regulate the stability of the complex [21, 211, 212]. The phosphorylation of β-catenin by GSK3 is greatly enhanced by the presence of Axin, which acts as a scaffold for the other components [34]. Axin and APC are also substrates of GSK3. Axin phosphorylation by GSK3 stabilizes the protein [35], while APC phosphorylation by GSK3 enhances the interaction of β-catenin and APC [31]. GSK3 phosphorylates Ser33, Ser37, and Thr41 of β-catenin following priming at Ser45 by CKI [213, 214]. These residues lie in a trCP motif and phosphorylation recruits SKP1-cullin1-F-box (SCFβ-TrCP) E3 ligase complex followed by degradation of β-catenin via the 26S proteasome [210]. Exposure of cells to Wnts reduces GSK3 activity in the Axin complex (by disruption of protein:protein interactions or phosphorylation of Thr380) resulting in dephosphorylation and stabilization of β-catenin, which translocates to the nucleus to induce transcription in cooperation with TCF transcription factors. Interestingly the pool of GSK3 associated with Wnt signaling appears distinct to that associated with growth factor signaling [23], probably since the mechanism of inhibition is distinct in each case and the Wnt sensitive GSK3 is sequestered within microvesicles [24]. This targeting of SCFβ-TrCP to substrates of GSK3 may be more widespread than currently appreciated and may allow Wnts to alter the stability of a wide range of cellular proteins [24].

3.5.2. Hedgehog (Hh) Signaling-Ci155

The Hh family of secreted proteins controls cell growth and patterning in development, while mutations in components of the Hh signaling pathway are associated with increased human disease [215]. Cubitus interruptus (Ci155) is a transcriptional inducer first identified as a mediator of Hh signaling in Drosophila. Exposure of Drosophila cells to Hh blocks production of a transcriptional repressor normally generated by proteolytic cleavage of Ci155 [216]. Deletion of GSK3 (sgg in drosophila) results in accumulation of the full length Ci155 and the ectopic expression of Hh responsive genes including decapentaplegic (dpp) and wingless (wg), suggesting GSK3 inhibition is part of Hh regulation of Ci155 processing. Ci155 is phosphorylated by GSK3 at three sites (852 and 884/888) after priming (at 856 and 892, resp.) by protein kinase A (PKA) [43, 44]. Mutation of these GSK3 target sites in Ci155 blocks processing and prevents the production of the repressor [43, 44]. Hence GSK3 acts in conjunction with PKA to promote proteolytic processing of Ci155, switching it from a transcriptional inducer to repressor. Hh may reduce Ci155 proteolysis by inhibiting GSK3 and promoting Ci155 dephosphorylation.

3.5.3. Cardiomyocyte Development-Myocardin

Myocardin is a muscle-specific transcription factor whose overexpression induces hypertrophy in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes [99], with increased cell size, total protein amount, and induction of generation of atrial natriuretic factor (ANF). Myocardin is phosphorylated by GSK3 at multiple sites in two regions of the protein between Ser455 to Ser467 and Ser624 to Ser636 [99]. Myocardin-induced ANF transcription and increase in total protein amount are enhanced by LiCl treatment of cells, consistent with GSK3 inhibiting myocardin activity. A phosphorylation-resistant myocardin mutant (8xAla) activated ANF transcription twice as potently as wild-type myocardin [99]. Conversely, a phosphomimetic myocardin mutant (8xAsp) was relatively transcriptionally inactive compared to wild type, in the presence of GSK3 inhibitors. Therefore, the GSK3-myocardin interaction regulates cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.

3.5.4. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition-Snail

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) occurs during embryonic development and is triggered by Snail, a zinc-finger transcription factor, which acts by repressing E-cadherin transcription. Snail is highly unstable with a half-life of about 25 min. GSK3β binds to and phosphorylates Snail at two consensus motifs including residues 97/101 and 108/112/116/120 [134]. Phosphorylation of the first motif regulates β-Trcp-mediated ubiquitination, whereas phosphorylation of the second motif controls subcellular localization [134]. A variant of Snail (Snail-6SerAla), which cannot be phosphorylated at these motifs, is much more stable and resides exclusively in the nucleus to induce EMT. Importantly, inhibition of GSK3 results in the upregulation of Snail and downregulation of E-cadherin in vivo. Thus, Snail and GSK3 function as a molecular switch leading to EMT.

3.6. GSK3 in Immunology

There are many studies suggesting that GSK3 plays a key role in both the innate and adaptive immune systems (for recent paper see [217, 218]). There are two main strands of evidence supporting this function for GSK3: firstly that many cytokines and immune stimuli regulate GSK3 activity, and secondly that inhibition of GSK3 alters many aspects of the immune response. Specifically, Toll-like receptors [219, 220], T cell receptor [221], CD28 [221], and interleukin receptors [222] have all been shown to induce inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK3 in cells. In contrast, IFN-γ reduces phosphorylation and activates GSK3 in TLR2-stimulated macrophages [223] or RAW264.7 cells [224]. These studies place GSK3 upstream of STAT3 and STAT1 in the IFN-γ signaling pathway, but have not demonstrated that the STATs are direct targets for GSK3. Inhibition of GSK3, using selective inhibitors or shRNAi, decrease IFN-γ-induced inflammation and this action requires the Src homology-2 domain containing phosphatase 2 (SHP2) [224]. Inhibition of GSK3 activates SHP2, preventing STAT1 activation in late stage IFN-γ stimulation; however, like STATs, SHP2 is not a direct target for GSK3 [224].

Interestingly, pharmacological reduction of GSK3 (admittedly in some cases not with very selective inhibitors) suppresses the production of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF, and IL-12, whilst enhancing production of IL-10 by TLRs [219]. Despite these major effects of GSK3 on cytokine production the specific substrates of GSK3 responsible remain elusive. NFAT, C/EBPβ, and CREB are transcription factors known to regulate many of these genes and both are proposed substrates of GSK3 (Table 1(a)); however these proteins have not been studied in the context of immunological regulation by GSK3. GSK3 inhibition increases the nuclear translocation of several mediators of the immune response, including these transcription factors [217]. GSK-3 phosphorylates a series of conserved serines on NFAT, at least in vitro, and phosphorylation of these sites inhibits DNA binding and promotes nuclear exit of NFAT (thereby opposing calcineurin signaling) [105–107]. It remains to be seen how many of the immune effects of GSK3 inhibition are mediated through direct regulation of these transcription factors.

4. Physiological Outcome of GSK3 Inhibition

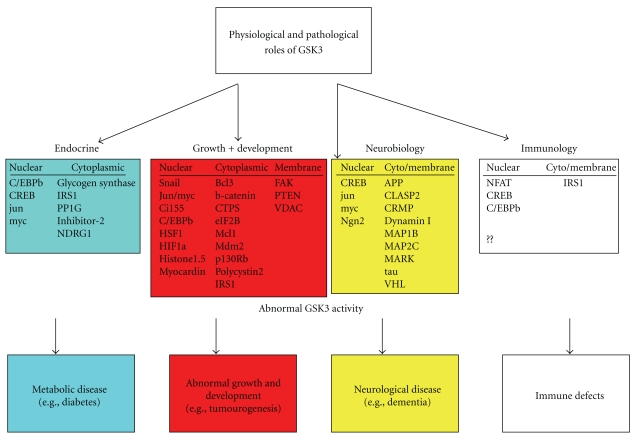

The literature indicates that inhibition of GSK3 in vivo would reduce the phosphorylation of dozens of proteins (Table 1) and influence a wide range of cellular processes (Figure 2), including cell growth, differentiation, survival, and communication. GSK3 inhibition would then be predicted to have numerous unwanted side-effects (Table 2). In particular, the potential oncogenicity of GSK3 inhibition is a major worry, and detrimental effects on the immune system, heart, and development are all possible (Table 2). Taken together with the lethality of genetic ablation of just one isoform of GSK3 (GSK3β), and the important role of GSK3 in Wnt and growth factor signaling, it is perhaps not surprising that despite the huge effort to develop potent inhibitors of GSK3, none have actually made it into Phase 2 clinical trials.

Figure 2.

Potential physiological and pathological effects of phosphorylation of proposed GSK3 substrates.

Table 2.

-GSK3 inhibition in vivo. Potential functional outcomes of pharmacological inhibition of GSK3.

| Substrate group 1—Metabolic: Overall Effect is anti-diabetic | |

|---|---|

| GS | Increase glycogen synthesis and glucose disposal (anti-diabetic) |

| Unknown | Turn off hepatic glucose output (anti-diabetic) |

| CREB | Reduce glucagon action (anti-diabetic) |

| IRS1 | Stabilise IRS1 protein and enhance insulin action (anti-diabetic) |

| Inhibitor2 | Inhibit PP1 (not clear if beneficial) |

| Substrate group 2—Growth: Predicted effect would be oncogenic, except for effect on mdm2/p53 and PTEN | |

| BCL3 | Stabilise BCL3 (increased oncogenic potential) |

| c-jun | Induce c-jun activity (increased oncogenic potential) |

| c-myc | Stabilize c-myc protein (increased oncogenic potential) |

| Mcl-1 | Stabilise Mcl-1 (antiapoptotic) |

| p130Rb | Increase p130Rb degradation (cell cycle progression) |

| PTEN | Decrease PI3K signaling (decrease growth factor signaling) |

| IRS1 | Stabilise IRS1 and enhance PI3K signaling (increase growth) |

| HIF1a | Stabilize HIF1a (could induce cell growth) |

| eIF2B | Enhance protein translation (aid cell growth) |

| VDAC | Enhance VDAC interaction with mitochondria (antiapoptotic) |

| CTPS | Enhance CTP production (aid cell growth) |

| FAK | Increase FAK activity (enhance cell spreading and migration) |

| Mdm2 | Stabilise p53 (tumour suppression) |

| Substrate group 3—Alzheimer's disease: Conducive to reducing AD pathology | |

| Tau | Reduce tangle formation (anti-AD?) |

| APP | Reduce abeta production (anti-AD?) |

| CRMP2 | Regulate axon outgrowth, reduce CRMP2 found in AD (anti-AD?) |

| MARK2 | Reduce tau phosphorylation (anti-AD?) |

| Calcipressin | Regulate calcineurin action (anti-AD?) |

| Substrate group 4—Wnt and Hh signaling: Enhanced effect on Wnt and Hh signaling | |

| b-catenin | Induce b-catenin levels (induce wnt signaling) |

| Axin | Reduce axin levels (induce wnt signaling) |

| APC | Reduce APC b-catenin interaction (induce wnt signaling) |

| Ci155 | Reduce proteolysis of Ci155 (enhanced Hh signaling) |

| Substrate group 5—Other possible detrimental effects: | |

| MAP1B | Reduce MAP1B interaction with microtubules (Wnt7a resistance) |

| MAP2C | Increase MAP2C interaction with microtubules (effect not clear) |

| CLASP2 | Alteration of actin-microtubule interaction (effect not clear) |

| Dynamin I | Reduced presynaptic ADBE (effect not clear) |

| Ngn2 | Impaired motor neuron designation (developmental?) |

| PC2 | Relocalise PC2 (enhance polycystic kidney disease) |

| Myocardin | Enhance mycardin action (cardiac hypertrophy?) |

| NFAT | Nuclear localization (compromise immune system?) |

| Unknown | Suppress IL-1β, IL-6, TNF, IL-12 (compromise immune system?) |

| Unknown | Induction of IL-10 (compromise immune system?) |

However, it seems rather premature at this time to discount inhibition of GSK3 as a beneficial therapeutic avenue. There is currently a lack of published evidence that truly specific GSK3 inhibitors, at concentrations that produce GSK3 inhibition, are harmful to healthy organisms, yet there is a study demonstrating efficacy at glucose lowering in a model of T2DM with no reported toxic side effects [159].

There are perhaps three major issues that should be addressed to establish whether GSK3 inhibitors should be pursued further for therapeutic potential.

Firstly, how harmful is conditional ablation of GSK3 in adult animals? GSK3 inhibitors would not be used from birth, and very few pharmaceuticals achieve 100% inhibition of their targets, hence it seems unlikely that the pathways responsible for the lethality of the GSK3β knockout or those involved in embryonic development would be of relevance in the treatment of adults for diabetes or Alzheimer's disease.

Secondly, how many of these reported substrates are actually affected by specific GSK3 inhibitors in vivo? As discussed in this paper very few of the substrates in Table 1(a) have convincing evidence establishing them as bona fide GSK3 substrates, while it has not yet been proven that the phosphorylation (never mind proposed function) of most of the substrates listed in Table 1(b) is significantly affected by specific GSK3 inhibition in vivo. A comprehensive analysis of animals receiving efficacious doses of specific GSK3 inhibitors may show that very few of these proteins are functionally affected by such pharmaceuticals.

Finally, most studies that aimed at identifying GSK3 substrates have chronically deleted GSK3 (genetically, siRNAi or high-dose inhibitor). Animals lacking one allele of each GSK3 isoform have a much less severe phenotype, suggesting partial loss of GSK3 even chronically from birth is not oncogenic. In addition, physiological regulation of GSK3 is normally both partial and transient. For example insulin treatment of cells rarely inhibits GSK3 more than 50% and activity returns to normal in a few hours, while Wnt signaling only regulates a very specific pool of GSK3. In addition many of the key processes regulated by GSK3 have feedback mechanisms to overcome abnormal regulation so proposed side effects may not materialize as predicted. It is quite likely that only transient inhibition of GSK3 (back to normal levels of GSK3 activity rather than complete ablation) would be required for many of the beneficial effects of GSK3 inhibition. Therefore there is scope for more elegant intervention of GSK3 function to achieve beneficial responses, without producing complete and chronic inhibition.

One would hope that improved knowledge of GSK3 biology would aid in the development of beneficial interventions. Others have suggested that drugs aimed at the phosphate binding pocket of GSK3 would preferentially inhibit phosphorylation of primed substrates, and therefore reduce potential side effects. However, Table 1(b) would suggest that most substrates of GSK3 do require a priming event. Other possibilities include isoform specific intervention, but to date there is only tantalizing evidence for substrate preference and little evidence for substrates that are completely specific to one GSK3 isoform. However changing the ratio of GSK3 isoform expression in specific tissues may still alter substrate phosphorylation patterns. Possibly the most promising area is the concept of substrate selective inhibition, where a specific pool of GSK3 could be targeted (or avoided). It has been known for some time that GSK3 exists in the Axin-APC complex, and this “GSK3 pool” is distinct from that targeted by growth factors [23, 24]. If other GSK3 complexes exist then the substrates listed in Table 1(b) could be subdivided by the GSK3 complex that regulates them. Inhibition of a GSK3 containing complex would then have a more specific outcome than global GSK3 inhibition.

Acknowledgment

The research ongoing in Dr.Sutherlands lab is supported by the Alzheimer's Research Trust, Diabetes UK, Tenovus Scotland, and the MRC.

References

- 1.Embi N, Rylatt DB, Cohen P. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle. Separation from cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphorylase kinase. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1980;107(2):519–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishiguro K, Shiratsuchi A, Sato S, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β is identical to tau protein kinase I generating several epitopes of paired helical filaments. FEBS Letters. 1993;325(3):167–172. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frame S, Cohen P. GSK3 takes centre stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochemical Journal. 2001;359(1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jope RS, Johnson GVW. The glamour and gloom of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2004;29(2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhat RV, Budd Haeberlein SL, Avila J. Glycogen synthase kinase 3: a drug target for CNS therapies. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;89(6):1313–1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frame S, Cohen P, Biondi RM. A common phosphate binding site explains the unique substrate specificity of GSK3 and its inactivation by phosphorylation. Molecular Cell. 2001;7(6):1321–1327. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodgett JR. cDNA cloning and properties of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Methods in Enzymology. 1991;200:564–577. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00172-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukai F, Ishiguro K, Sano Y, Fujita SC. Aternative splicing isoform of tau protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;81(5):1073–1083. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood-Kaczmar A, Kraus M, Ishiguro K, Philpott KL, Gordon-Weeks PR. An alternatively spliced form of glycogen synthase kinase-3β is targeted to growing neurites and growth cones. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2009;42(3):184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castaño Z, Gordon-Weeks PR, Kypta RM. The neuron-specific isoform of glycogen synthase kinase-3β is required for axon growth. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;113(1):117–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soutar MPM, Kim W-Y, Williamson R, et al. Evidence that glycogen synthase kinase-3 isoforms have distinct substrate preference in the brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;115(4):974–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutherland C, Leighton IA, Cohen P. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β by phosphorylation: new kinase connections in insulin and growth-factor signalling. Biochemical Journal. 1993;296(1):15–19. doi: 10.1042/bj2960015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutherland C. The α-isoform of glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle is inactivated by p70 S6 kinase or MAP kinase-activated protein kinase-1 in vitro. FEBS Letters. 1994;338(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cross DAE, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378(6559):785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eldar-Finkelman H, Seger R, Vandenheede JR, Krebs EG. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by epidermal growth factor is mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase/p90 ribosomal protein S6 kinase signaling pathway in NIH/3T3 cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(3):987–990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eickholt BJ, Walsh FS, Doherty P. An inactive pool of GSK-3 at the leading edge of growth cones is implicated in Semaphorin 3A signaling. Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;157(2):211–217. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito Y, Oinuma I, Katoh H, Kaibuchi K, Negishi M. Sema4D/plexin-B1 activates GSK-3β through R-Ras GAP activity, inducing growth cone collapse. EMBO Reports. 2006;7(7):704–709. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhat RV, Shanley J, Correll MP, et al. Regulation and localization of tyrosine phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β in cellular and animal models of neuronal degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(20):11074–11079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190297597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lochhead PA, Kinstrie R, Sibbet G, Rawjee T, Morrice N, Cleghone V. A chaperone-dependent GSK3β transitional intermediate mediates activation-loop autophosphorylation. Molecular Cell. 2006;24(4):627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole A, Frame S, Cohen P. Further evidence that the tyrosine phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) in mammalian cells is an autophosphorylation event. Biochemical Journal. 2004;377(1):249–255. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu D, Pan W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2010;35(3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McManus EJ, Sakamoto K, Armit LJ, et al. Role that phosphorylation of GSK3 plays in insulin and Wnt signalling defined by knockin analysis. EMBO Journal. 2005;24(8):1571–1583. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole AR, Sutherland C. Measuring GSK3 expression and activity in cells. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2008;468:45–65. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-249-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taelman VF, Dobrowolski R, Plouhinec J-L, et al. Wnt signaling requires sequestration of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 inside multivesicular endosomes. Cell. 2010;143(7):1136–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thornton TM, Pedraza-Alva G, Deng B, et al. Phosphorylation by p38 MAPK as an alternative pathway for GSK3β inactivation. Science. 2008;320(5876):667–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1156037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bikkavilli RK, Feigin ME, Malbon CC. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates canonical Wnt-β-catenin signaling by inactivation of GSK3β. Journal of Cell Science. 2008;121(21):3598–3607. doi: 10.1242/jcs.032854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aplin AE, Gibb GM, Jacobsen JS, Gallo JM, Anderton BH. In vitro phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain of the amyloid precursor protein by glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1996;67(2):699–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67020699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryder J, Su Y, Liu F, Li B, Zhou Y, Ni B. Divergent roles of GSK3 and CDK5 in APP processing. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;312(4):922–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santos SF, Tasiaux B, Sindic C, Octave JN. Inhibition of neuronal calcium oscillations by cell surface APP phosphorylated on T668. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.01.006. Neurobiology of Aging. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrarese A, Marin O, Bustos VH, et al. Chemical dissection of the APC repeat 3 multistep phosphorylation by the concerted action of protein kinases CK1 and GSK3. Biochemistry. 2007;46(42):11902–11910. doi: 10.1021/bi701674z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikeda S, Kishida M, Matsuura Y, Usui H, Kikuchi A. GSK-3β-dependent phosphorylation of adenomatous polyposis cop gene product can be modulated by β-catenin and protein phosphatase 2A complexed with Axin. Oncogene. 2000;19(4):537–545. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]