A novel physiological role for the bile acid responsive GPCR, TGR5, is described that involves relaxation of the gallbladder in response to bile acids.

Abstract

TGR5 is a G protein-coupled bile acid receptor present in brown adipose tissue and intestine, where its agonism increases energy expenditure and lowers blood glucose. Thus, it is an attractive drug target for treating human metabolic disease. However, TGR5 is also highly expressed in gallbladder, where its functions are less well characterized. Here, we demonstrate that TGR5 stimulates the filling of the gallbladder with bile. Gallbladder volume was increased in wild-type but not Tgr5−/− mice by administration of either the naturally occurring TGR5 agonist, lithocholic acid, or the synthetic TGR5 agonist, INT-777. These effects were independent of fibroblast growth factor 15, an enteric hormone previously shown to stimulate gallbladder filling. Ex vivo analyses using gallbladder tissue showed that TGR5 activation increased cAMP concentrations and caused smooth muscle relaxation in a TGR5-dependent manner. These data reveal a novel, gallbladder-intrinsic mechanism for regulating gallbladder contractility. They further suggest that TGR5 agonists should be assessed for effects on human gallbladder as they are developed for treating metabolic disease.

Bile, which is composed primarily of bile acids, cholesterol, and phospholipids, is produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder. In response to the ingestion of food, the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK) is secreted from enteroendocrine cells in the duodenum to promote gallbladder contraction and the release of bile into the small intestine, where it facilitates the absorption of lipophilic nutrients. The effect of CCK on gallbladder motility is opposed by fibroblast growth factor (FGF)15/19, a hormone that is released from the ileum 1–2 h after a meal to cause gallbladder relaxation (1, 2). FGF15 is the mouse ortholog of human FGF19. Mice lacking either FGF15 or its coreceptors, FGF receptor 4 and β-Klotho, have gallbladders containing less bile than those of wild-type mice (3, 4). Thus, the alternate release of CCK and FGF15/19 controls the cycle of gallbladder emptying and filling. Notably, impairments in gallbladder motility are associated with the development of gallstone disease (5).

TGR5 (also known as G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 and membrane-type bile acid receptor) is a G protein-coupled cell-surface receptor that is activated by both primary and secondary bile acids with a rank order efficacy of lithocholic acid (LCA) ∼ deoxycholic acid > chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) > cholic acid (CA) (6, 7). TGR5 is expressed in macrophages, where its agonism suppresses phagocytosis and lipopolysaccharide-stimulated cytokine production (6). TGR5 is also expressed in brown adipose tissue and in enteroendocrine cells in the intestine, where its pharmacologic activation induces energy expenditure and improves insulin sensitivity in rodent models of obesity (8, 9). Interestingly, TGR5 is expressed in gallbladder at much higher levels than in other tissues (10). Within the gallbladder, TGR5 localizes to the apical membrane of the epithelium (10, 11). In studies performed with human gallbladder tissue, TGR5 activation by bile acids rapidly increased cAMP levels and decreased intracellular chloride concentrations, suggesting a role for TGR5 in promoting chloride and fluid secretion in gallbladder epithelial cells (11). Mice lacking TGR5 (Tgr5−/−) are viable and develop normally but have a decreased bile acid pool size (10, 12). The Tgr5−/− mice are also refractory to the formation of cholesterol gallstones caused by a high-fat “lithogenic” diet containing CA (10). This may be due in part to an increase in hepatic expression of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1), which catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the conversion of cholesterol to bile acids. Based on these findings, it was proposed that TGR5 antagonism might prove useful for treating or preventing gallstone formation (10).

Although the pharmacologic effects of activating TGR5 in macrophage, brown adipose tissue, and intestine have been studied (8, 9), little is known about the physiologic actions of TGR5. Given the abundant expression of TGR5 in gallbladder, we have analyzed its function in this tissue. We demonstrate that TGR5 agonism in gallbladder causes smooth muscle relaxation and promotes gallbladder filling.

Results and Discussion

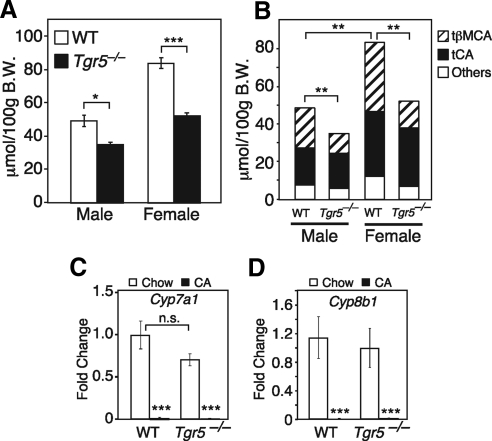

Because TGR5 is abundantly expressed in the gallbladder (10, 11), we analyzed bile acid parameters in wild-type and Tgr5−/− mice fed a regular chow diet. Consistent with a previous report (12), bile acid pool size was significantly smaller in both male and female Tgr5−/− mice (Fig. 1A). This decrease in bile acid pool size was accompanied by a decrease in the fraction of tauro-β-muricholic acid (tβMCA) in the pool (Fig. 1B). Although Cyp7a1 mRNA levels trended lower in Tgr5−/− mice (Fig. 1C), which may have contributed to the decrease in bile acid pool size, this decreased expression did not reach statistical significance. Cyp8b1 expression (Fig. 1D) and, consequently, tauro-CA levels (Fig. 1B) were unchanged in the Tgr5−/− mice. Furthermore, negative feedback regulation of Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 transcription was intact in Tgr5−/− mice, because CA administration repressed mRNA levels of these genes (Fig. 1, C and D). Cyp27a1 expression levels were also unchanged in the Tgr5−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). Thus, the basis for the change in the tβMCA composition of the bile acid pool remains unresolved.

Fig. 1.

Bile parameters in Tgr5−/− mice. A, Bile acid pool size was measured in male and female wild-type (WT) and Tgr5−/− mice (n = 6/group). B, Bile acid composition, including tβMCA and tauro-CA (tCA), was measured by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry in WT and Tgr5−/− male and female mice (n = 6/group). Note statistical significance refers to changes in tβMCA levels. C and D, Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 mRNA levels were measured by qPCR in liver from WT and Tgr5−/− mice fed with chow or 0.2% CA diet for 2 wk (n = 4–5/group). All data are the mean ± sem. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001. B.W., Body weight; n.s., not significant.

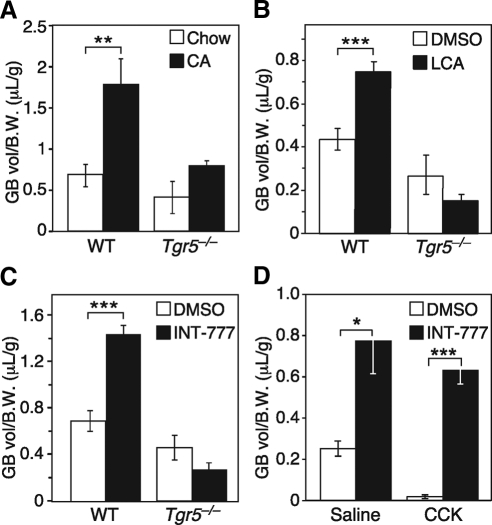

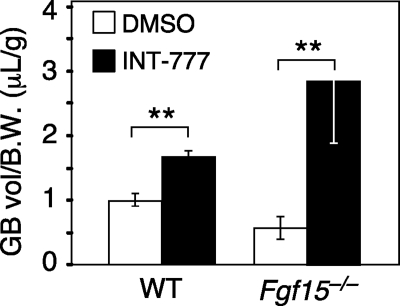

While measuring the bile acid pool size, we noted a trend toward reduced gallbladder volume in Tgr5−/− mice. This difference was markedly enhanced by administration of CA in the diet for 2 wk (Fig. 2A). Under these conditions, gallbladder volume increased approximately 3-fold in wild-type mice but did not change significantly in Tgr5−/− mice. To assess whether acute TGR5 activation increases gallbladder volume, mice were injected with either the naturally occurring TGR5 agonist, LCA, or the synthetic TGR5 agonist, INT-777 (13), and gallbladder volume was measured 30 min later. Both agonists significantly increased gallbladder volume in wild-type but not Tgr5−/− mice (Fig. 2, B and C). Importantly, the effects of INT-777 on gallbladder filling occurred without changing the concentration of CCK (Supplemental Fig. 2). In fact, INT-777 treatment completely reversed CCK-induced contraction of the gallbladder and stimulated gallbladder filling to levels similar to that observed in the absence of CCK (Fig. 2D). Thus, TGR5 activation stimulates gallbladder filling through a rapid and CCK-independent mechanism.

Fig. 2.

TGR5 agonism increases gallbladder (GB) volume. A–C, Gallbladder volume was measured in male wild-type (WT) and Tgr5−/− mice treated for: 2 wk with 0.2% CA in the diet (n = 4–5/group) (A), 30 min with LCA (60 mg/kg) or DMSO control by ip injection (n = 5/group) (B), and 30 min INT-777 (60 mg/kg) or DMSO control by ip injection (n = 5–6/group) (C). D, Male mice were treated with CCK (200 ng/kg) or saline control and INT-777 (60 mg/kg) or DMSO control by ip injection (n = 5/group). Gallbladder volumes were normalized to body weight (B.W.). All data are the mean ± sem. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

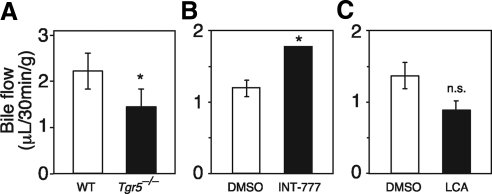

We next examined whether the TGR5-mediated increase in gallbladder volume was due to increased bile flow from the liver. Tgr5−/− mice had significantly reduced bile flow (Fig. 3A). Conversely, INT-777 treatment increased bile flow (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that TGR5 directly regulates bile flow, a finding consistent with its expression in cholangiocytes (14, 15). Interestingly, LCA, which is well known to cause cholestasis, decreased bile flow (Fig. 3C) under conditions in which it increased gallbladder volume in a TGR5-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). We conclude that TGR5 activation stimulates bile flow, but that this increase is not required for TGR5-mediated gallbladder filling.

Fig. 3.

TGR5 regulates bile flow. A, Bile flow rate was measured in male wild-type (WT) and Tgr5−/− mice (n = 6–8/group). B and C, Bile flow rates were measured in male mice 15 min after ip injection of LCA (60 mg/kg) or DMSO control (n = 4/group) (B) or INT-777 (60 mg/kg) or DMSO control (n = 5–6/group) (C). Bile flow rates were normalized to body weight. All data are the mean ± sem. *, P < 0.01. n.s., Not significant.

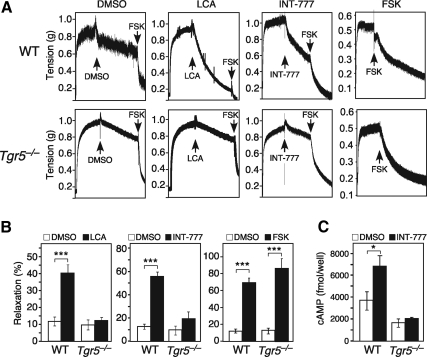

To test whether TGR5 has direct effects on gallbladder smooth muscle, we performed ex vivo tensiometry experiments with gallbladders isolated from wild-type and Tgr5−/− mice. Both LCA and INT-777 markedly relaxed gallbladders from wild-type but not Tgr5−/− mice (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, forskolin, which induces cAMP levels through a TGR5-independent mechanism, relaxed both wild-type and Tgr5−/− gallbladders (Fig. 4, A and B). INT-777 treatment significantly increased cAMP concentrations in gallbladder tissue from wild-type but not Tgr5−/− mice (Fig. 4C). Similarly, LCA treatment also increased cAMP concentrations in gallbladder tissue (Supplemental Fig. 3). We conclude that TGR5 acts directly on gallbladder to cause smooth muscle relaxation via induction of cAMP levels. Lastly, we tested for cross talk between the TGR5 and FGF15/19 pathways in gallbladder filling. INT-777 administration increased gallbladder volume in Fgf15−/− mice (Fig. 5A), suggesting that TGR5 may act downstream of FGF15 in a common signaling pathway.

Fig. 4.

TGR5 agonism relaxes gallbladder smooth muscle ex vivo. A, Ex vivo tensiometry was performed using gallbladder tissue from female wild-type (WT) (top panels) or Tgr5−/− mice (lower panels). Gallbladders were precontracted with 1 nm CCK for 20 min, washed, and subsequently treated with either vehicle (DMSO), LCA (10 μm), INT-777 (10 μm), or forskolin (FSK) (2 nm) for 20 min. DMSO, LCA, and INT-777 treatments were followed by a second wash and treatment with forskolin (2 nm) for 20 min to ensure integrity of the tissue. Representative tension tracings are shown with treatment times indicated by arrows. B, Quantification of gallbladder relaxation using tissue derived from WT or Tgr5−/− mice treated with vehicle (DMSO), LCA, INT-777, or forskolin as in A. Data are the mean ± sem of experiments performed in quadruplicate and are expressed as percent relaxation of CCK-induced contraction. ***, P < 0.001. C, Intracellular cAMP concentrations were measured in gallbladder tissue from WT or Tgr5−/− mice treated ex vivo with vehicle (DMSO) (open bars) or INT-777 (25 μm) (closed bars) for 15 min. Experiments repeated in male mice produced similar results. Data are the mean ± sem of assays performed six to seven times. *, P < 0.01.

Fig. 5.

Cross talk between TGR5 and FGF15 pathways. A, Gallbladder (GB) volume was measured 30 min after ip injection of INT-777 (60 mg/kg) or vehicle (DMSO) into male wild-type (WT) or and Fgf15−/− mice (n = 4–6/group). Gallbladder volumes were normalized to body weight (B.W.). All data are the mean ± sem. *, P < 0.01.

In summary, we describe an important role for TGR5 in stimulating gallbladder smooth muscle relaxation and filling. It was previously shown that Tgr5−/− mice were resistant to lithogenic diet-induced cholesterol gallstone formation, which was attributed to an increase in Cyp7a1 expression and a corresponding reduction in the cholesterol saturation index of the bile (10). Although it remains unclear whether TGR5's effect on gallbladder volume contributes to cholesterol gallstone formation, decreased gallbladder motility such as that seen in the Tgr5−/− mice is generally associated with an increase in gallstones (16). Notably, TGR5 is an attractive drug target for treating obesity and type 2 diabetes, because TGR5 agonism stimulates energy expenditure and lowers serum glucose (8, 9). Because TGR5 is also highly expressed in human gallbladder (11), it will be important to assess the impact of its activation on human gallbladder function because TGR5 agonists are developed as drugs.

We also provide evidence that TGR5 may act in concert with FGF15/19 in signaling the gallbladder to fill. Consistent with this hypothesis, both TGR5 agonists and FGF15/19 increase cAMP concentrations in gallbladder (Fig. 4C and Ref. 1). Based on our findings, we suggest a two-pronged “distal/proximal” signaling mechanism for controlling gallbladder filling. FGF15/19, which is induced by bile acids in the ileum, represents a distal hormonal signal that effectively “primes” the gallbladder for refilling after a meal. The presence of TGR5 in gallbladder provides a reinforcing proximal mechanism for detecting local bile acid concentrations and adjusting gallbladder volume accordingly. In this regard, it is intriguing that TGR5 induces chloride secretion from the gallbladder epithelium via the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (17), which may contribute to gallbladder filling. Future studies will be directed at further defining the relationship between TGR5 and FGF15/19 and understanding their respective roles in regulating gallbladder motility.

We note that while this manuscript was in preparation, Lavoie et al. (18) reported that TGR5 is expressed in the gallbladder smooth muscle, where its activation causes relaxation via a cAMP-protein kinase A-KATP channel pathway. Their ex vivo findings are consistent with and complementary to our in vivo and ex vivo studies.

Materials and Methods

Animal procedures

All experiments were performed with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, which assures that all animal use adheres to federal regulations as published in the Animal Welfare Act, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the Public Health Service Policy, and the U.S. Government Principles Regarding the Care and Use of Animals. Tgr5−/− and Fgf15−/− mice were described previously (10, 19). Experiments were performed in both male and female aged-matched mice as noted in figure legends. Mice were fed global irradiated rodent chow (TD.2916, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) supplemented with or without 0.2% CA ad libitum. For measurement of bile acid pool size and composition, mice were fasted 4 h before euthanasia. For in vivo gallbladder volume assays, mice were fasted starting at midnight and 14–18 h later treated with CCK, TGR5 agonists, or vehicle control by ip injection. Gallbladders were removed and volume measured 30 min after treatment.

Bile acid analysis

For measurement of bile acid pool size, bile acids were extracted and quantified as previously described (20). Briefly, the liver, gallbladder, and entire small intestine were collected, spiked with CDCA-D4, homogenized, and extracted with ethanol under reflux. Samples were filtered through no. 2 Whatman paper before an aliquot of the extract was dried under a nitrogen stream and redissolved in methanol for liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis. Bile acids were qualified by ionization in negative ion mode. Selective ion monitoring was used to detect the conjugated and unconjugated bile acids. Quantification was performed based on peak areas using external calibration curves of standards prepared in methanol. CDCA-D4 was used to calculate the recovery of bile acids after extraction relative to a blank control.

Bile flow measurements

Mice were fasted for 12 h and then injected with vehicle, LCA, or INT-777 as described in Results and Discussion. After 15 min, mice were anesthetized by ip injection of avertin. The abdomen was opened, the cystic bile duct ligated, and a polyethylene-10 catheter inserted at the distal end of the common bile duct before the branching point to the gallbladder and liver. The surgery was performed at 37 C. Hepatic bile was collected for 30 min. The volume of the bile was measured and normalized to time and body weight of the mice.

RT-quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from liver and intestine using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, TX). After deoxyribonuclease I (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) treatment, RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the SuperScript II First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Primers for each gene were designed and validated as previously described (21). Primer sequences include: Cyp7a1 forward 5′agcaactaaacaacctgccagtacta3′ and reverse 5′gtccggatattcaaggatgca3′, Cyp8b1 forward 5′gccttcaagtatgatcggttcct3′ and reverse 5′gatcttcttgcccgacttgtaga3′, and Cyp27a1 forward 5′gcctcacctatgggatcttca3′ and reverse 5′tcaaagcctgacgcagatg3′. RT-qPCR contained 25 ng of cDNA, 150 nm of each primer, and 5 μl of SYBR GreenER PCR Master Mix (Invitrogen) and were carried out in triplicate using an Applied Biosystems Prism 7900 HT instrument (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Relative mRNA levels were calculated by the comparative threshold cycle method using cyclophilin as the internal control.

Ex vivo tensiometry measurements

Gallbladders were removed from mice anesthetized by halothane. Cross-sections of the gallbladder were cut in the shape of a ring and the right and left lateral aspects of the gallbladder tethered with 0.2-mm pins. Gallbladder sections were mounted in organ baths containing 8 ml of physiological saline solution (120 mm NaCl, 4.8 mm KCl, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 1.2 mm NaH2PO4, 20.4 mm NaHCO3, 1.6 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm dextrose) at 37 C continuously bubbled with O2:CO2 (95:5%). Tension was measured with Grass FT03 force displacement transducers and a Powerlab 8SP digital recorder (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Resting strip tension was adjusted to between 0.15 and 0.2 g. Experiments were started after a 1-h stabilization period. Tension was measured in response to CCK-8 (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Burlingame, CA), LCA, INT-777, forskolin, or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) control.

Gallbladder cAMP concentration measurements

Gallbladders from wild-type or Tgr5−/− mice were removed, drained, and cut into three to four pieces in ice-cold PBS. Gallbladder sections were subsequently placed in six-well plates and incubated at 37 C in William's E medium as described (17) in the presence of INT-777 or vehicle control. 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine was included in all media. cAMP was extracted using 0.1 n HCl, and intracellular cAMP levels were determined using a cAMP EIA kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean (±sem). For comparison between two groups, the unpaired two-tailed Student's t test was performed. One-way ANOVA followed by the Newman-Keuls procedure was used to compare more than two groups. All tests were performed using the software program GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Galya Vassileva, Eric Gustafson, and their colleagues at Schering-Plough for providing us with the Tgr5−/− mice; Mark Pruzanski and Roberto Pellicciari for providing us with INT-777; Kelly Suino-Powell and Eric Xu for FGF19; Kris Kamm for help with tensiometry measurements; and Richard Hogg and Robert Gerard for help with tail-vein injections.

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.J.M.), the National Institutes of Health Grant DK067158 (to S.A.K. and D.J.M.), and the Robert A. Welch Foundation Grants I-1275 (to D.J.M.) and I-1558 (to S.A.K.).

Disclosure Summary: S.A.K. is a scientific advisory board member of Intercept Pharmaceuticals; S.A.K. and D.J.M. have consulted for Daiichi-Sankyo; T.L., S.R.H., S.K., M.U., and D.R.S. have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- CA

- Cholic acid

- CCK

- cholecystokinin

- CDCA

- chenodeoxycholic acid

- DMSO

- dimethylsulfoxide

- FGF

- fibroblast growth factor

- LCA

- lithocholic acid

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- tβMCA

- tauro-β-muricholic acid.

References

- 1. Choi M, Moschetta A, Bookout AL, Peng L, Umetani M, Holmstrom SR, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE, Richardson JA, Gerard RD, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. 2006. Identification of a hormonal basis for gallbladder filling. Nat Med 12:1253–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lundåsen T, Gälman C, Angelin B, Rudling M. 2006. Circulating intestinal fibroblast growth factor 19 has a pronounced diurnal variation and modulates hepatic bile acid synthesis in man. J Intern Med 260:530–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ito S, Fujimori T, Furuya A, Satoh J, Nabeshima Y. 2005. Impaired negative feedback suppression of bile acid synthesis in mice lacking βKlotho. J Clin Invest 115:2202–2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yu C, Wang F, Kan M, Jin C, Jones RB, Weinstein M, Deng CX, McKeehan WL. 2000. Elevated cholesterol metabolism and bile acid synthesis in mice lacking membrane tyrosine kinase receptor FGFR4. J Biol Chem 275:15482–15489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Portincasa P, Di Ciaula A, Wang HH, Palasciano G, van Erpecum KJ, Moschetta A, Wang DQ. 2008. Coordinate regulation of gallbladder motor function in the gut-liver axis. Hepatology 47:2112–2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawamata Y, Fujii R, Hosoya M, Harada M, Yoshida H, Miwa M, Fukusumi S, Habata Y, Itoh T, Shintani Y, Hinuma S, Fujisawa Y, Fujino M. 2003. A G protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J Biol Chem 278:9435–9440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maruyama T, Miyamoto Y, Nakamura T, Tamai Y, Okada H, Sugiyama E, Itadani H, Tanaka K. 2002. Identification of membrane-type receptor for bile acids (M-BAR). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 298:714–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas C, Gioiello A, Noriega L, Strehle A, Oury J, Rizzo G, Macchiarulo A, Yamamoto H, Mataki C, Pruzanski M, Pellicciari R, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K. 2009. TGR5-mediated bile acid sensing controls glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab 10:167–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watanabe M, Houten SM, Mataki C, Christoffolete MA, Kim BW, Sato H, Messaddeq N, Harney JW, Ezaki O, Kodama T, Schoonjans K, Bianco AC, Auwerx J. 2006. Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature 439:484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vassileva G, Golovko A, Markowitz L, Abbondanzo SJ, Zeng M, Yang S, Hoos L, Tetzloff G, Levitan D, Murgolo NJ, Keane K, Davis HR, Jr, Hedrick J, Gustafson EL. 2006. Targeted deletion of Gpbar1 protects mice from cholesterol gallstone formation. Biochem J 398:423–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keitel V, Cupisti K, Ullmer C, Knoefel WT, Kubitz R, Häussinger D. 2009. The membrane-bound bile acid receptor TGR5 is localized in the epithelium of human gallbladders. Hepatology 50:861–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maruyama T, Tanaka K, Suzuki J, Miyoshi H, Harada N, Nakamura T, Miyamoto Y, Kanatani A, Tamai Y. 2006. Targeted disruption of G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (Gpbar1/M-Bar) in mice. J Endocrinol 191:197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pellicciari R, Gioiello A, Macchiarulo A, Thomas C, Rosatelli E, Natalini B, Sardella R, Pruzanski M, Roda A, Pastorini E, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J. 2009. Discovery of 6α-ethyl-23(S)-methylcholic acid (S-EMCA, INT-777) as a potent and selective agonist for the TGR5 receptor, a novel target for diabesity. J Med Chem 52:7958–7961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Keitel V, Donner M, Winandy S, Kubitz R, Häussinger D. 2008. Expression and function of the bile acid receptor TGR5 in Kupffer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 372:78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Keitel V, Ullmer C, Häussinger D. 2010. The membrane-bound bile acid receptor TGR5 (Gpbar-1) is localized in the primary cilium of cholangiocytes. Biol Chem 391:785–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang DQ, Cohen DE, Carey MC. 2009. Biliary lipids and cholesterol gallstone disease. J Lipid Res 50(Suppl):S406–S411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keitel V, Reinehr R, Gatsios P, Rupprecht C, Görg B, Selbach O, Häussinger D, Kubitz R. 2007. The G-protein coupled bile salt receptor TGR5 is expressed in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Hepatology 45:695–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lavoie B, Balemba OB, Godfrey C, Watson CA, Vassileva G, Corvera CU, Nelson MT, Mawe GM. 2010. Hydrophobic bile salts inhibit gallbladder smooth muscle function via stimulation of GPBAR1 receptors and activation of KATP channels. J Physiol 588:3295–3305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Inagaki T, Choi M, Moschetta A, Peng L, Cummins CL, McDonald JG, Luo G, Jones SA, Goodwin B, Richardson JA, Gerard RD, Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. 2005. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab 2:217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee YK, Schmidt DR, Cummins CL, Choi M, Peng L, Zhang Y, Goodwin B, Hammer RE, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. 2008. Liver receptor homolog-1 regulates bile acid homeostasis but is not essential for feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis. Mol Endocrinol 22:1345–1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bookout AL, Cummins CL, Mangelsdorf DJ, Pesola JM, Kramer MF. 2006. High-throughput real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR. Curr Protoc Mol Biol Chapter 15:Unit 15.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.