Chronic BH4 supplementation improves diastolic function, attenuates cardiac remodeling, and reduces oxidative stress in female mRen2.Lewis rats following the loss of ovarian hormones.

Abstract

After oophorectomy, mRen2.Lewis rats exhibit diastolic dysfunction associated with elevated superoxide, increased cardiac neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) expression, and diminished myocardial tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) content, effects that are attenuated with selective nNOS inhibition. BH4 is an essential cofactor of nNOS catalytic activity leading to nitric oxide production. Therefore, we assessed the effect of 4 wk BH4 supplementation on diastolic function and left ventricular (LV) remodeling in oophorectomized mRen2.Lewis rats compared with sham-operated controls. Female mRen2.Lewis rats underwent either bilateral ovariectomy (OVX) (n = 19) or sham operation (n = 13) at 4 wk of age. Beginning at 11 wk of age, OVX rats were randomized to receive either BH4 (10 mg/kg · d) or saline, whereas the sham rats received saline via sc mini-pumps. Loss of ovarian hormones reduced cardiac BH4 when compared with control hearts; this was associated with impaired myocardial relaxation, augmented filling pressures, increased collagen deposition, and thickened LV walls. Additionally, superoxide production increased and nitric oxide decreased in hearts from OVX compared with sham rats. Chronic BH4 supplementation after OVX improved diastolic function and attenuated LV remodeling while restoring myocardial nitric oxide release and preventing reactive oxygen species generation. These data indicate that BH4 supplementation protects against the adverse effects of ovarian hormonal loss on diastolic function and cardiac structure in mRen2.Lewis rats by restoring myocardial NO release and mitigating myocardial O2− generation. Whether BH4 supplementation is a therapeutic option for the management of diastolic dysfunction in postmenopausal women will require direct testing in humans.

Cardiovascular disease in women has gained attention in recent years in light of the recognized sex differences between males and females (1–4). Before menopause, the incidence of heart disease is significantly lower in women compared with men (5). However, both the risk and the prevalence of heart failure dramatically increases in women after the onset of menopause (6). Unlike their male counterparts, women predominantly exhibit diastolic impairment and eventual diastolic heart failure rather than systolic dysfunction (7, 8). The interplay between age and declining estrogens were deemed the common denominators in women's heart disease and led to robust examination of hormone replacement therapy in the cardioprotection of postmenopausal women. However, conflicting results failed to show cardioprotective benefit with replacement of various estrogen therapies (9), underscoring the need to gain further insight into the mechanisms that influence the development of heart disease in women.

Using the female mRen2.Lewis rat, an angiotensin-II-dependent model of hypertension, we show diastolic functional abnormalities and remodeling of the cardiac interstitium after early bilateral oophorectomy, a cardiac phenotype that bears a resemblance to the cardiac and vascular changes resulting from surgically induced or natural menopause (10). In this same rodent model, the loss of ovarian hormones exacerbates the increases in systolic blood pressure, which can be corrected with 17β-estradiol replacement (11). In a recent study, we further show that the pathogenesis of diastolic dysfunction in the female mRen2.Lewis rat involves a critical interaction between neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and ovarian hormones, particularly estrogens (12). That is, selective nNOS inhibition with N5-(1-Imino-3-butenyl)-1-ornithine (L-VNIO) attenuates diastolic dysfunction and cardiac remodeling in ovariectomized (OVX) mRen2.Lewis females, presumably due to the ability of L-VNIO to mitigate myocardial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. Taken together, these findings suggest that a dynamic shift occurs in the nNOS pathway within the female heart such that the loss of estrogens leads to uncoupling of nNOS and the subsequent generation of superoxide (O2−) rather than nitric oxide (NO) (12).

The effects of nNOS on diastolic function based upon the bioavailability of NO are also documented (13). Additional data show that estrogens can modulate the production of nNOS (14–17) as well as regulate guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH) (18–20). GTPCH is the rate-limiting enzyme for the synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), the necessary cofactor responsible for maintaining nNOS in a coupled state, which allows the enzyme's catalytic activity to generate NO (21). In our previous study, diminished BH4 levels within the heart tissue of oophorectomized rats was associated with compromised ventricular relaxation and cardiac structural alterations including increased collagen deposition and increased relative wall thickness (12). Theorizing that the loss of estrogens and consequent depletion of BH4 may lead to nNOS uncoupling and the release of reactive free radicals instead of NO, we hypothesized that BH4 supplementation would exert beneficial effects on diastolic function in terms of improving myocardial relaxation, attenuating left ventricular (LV) remodeling, and decreasing the generation of ROS in the heart of the OVX mRen2.Lewis rat.

Materials and Methods

Experimental model

Congenic female mRen2.Lewis rats obtained from the transgenic rat colony of the Hypertension and Vascular Research Center of Wake Forest University School of Medicine were weaned at 3 wk of age and allowed to acclimate in a temperature-controlled, Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal-approved facility (12-h light, 12-h dark cycle) with ad libitum food and water. The experimental procedures were approved by Wake Forest University School of Medicine's Animal Care and Use Committee. Rats were randomly divided into two groups at 4 wk of age: bilateral oophorectomized (OVX; n = 17) or sham-operated (n = 13), performed under 2% isoflurane anesthesia, as previously described (10, 12). Once the rats reached 11 wk of age, the OVX group was randomly divided to receive (6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-l-biopterin dihydrochloride (BH4; OVX+BH4; n = 8; Schricks Laboratories, Jona, Switzerland) administered via an osmotic minipump (Alzet model 2ML4, 2.5 μl/h, 4 wk; Durect Corp., Cupertino, CA) at a targeted dose of 10 mg/kg · d or saline (2.5 μl/h) as a vehicle control (OVX; n = 9). This dose of BH4 has been shown to be therapeutically effective in previous reports by other laboratories (22–24). Weekly tail-cuff plethysmography (NIBP-LE5001; Panlab, Barcelona, Spain) was used to measure blood pressure from 5–15 wk of age. Oophorectomy and depletion of circulating estradiol was confirmed using a serum estradiol assay (5 pg/ml detection limit; Polymedco, Cortlandt Manor, NY).

Echocardiographic evaluation

Cardiac function and structure were assessed before the protocol termination in anesthetized (ketamine/xylazine, 80/12 mg/kg) animals using a Philips 5500 echocardiograph (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA) and a 12-MHz phased array probe as previously described (10). Relative wall thickness (RWT) was calculated as: 2 × posterior wall thickness/LV end diastolic dimension (LVEDD).

Measurement of total biopterin and BH4 levels

Cardiac tissue BH4 levels were measured by HPLC with fluorescence detection as previously documented (25). Total biopterins [BH4, dihydrobiopterin (BH2), and oxidized biopterin (B)] were measured after acid oxidation of the deproteinated cardiac supernatant. BH2 plus B was determined by alkali oxidation, followed by iodine reduction and acidification. The resulting samples were centrifuged and small aliquots injected into a 250-mm long, 4.6-mm inner diameter Spherisorb ODS-1 column (5-μm particle size; Alltech Associates, Inc., Deerfield, IL). Fluorescence (350 nm excitation, 450 nm emission) was detected by a fluorescence detector (RF10AXL; Shimadzu Co., Columbia, MD). BH4 concentration was calculated by subtracting BH2 and B from total biopterins.

Nitrite measurements

Nitrite levels of were determined using a chemiluminescence-based nitric oxide analyzer (Sievers, Inc., GE Analytical Instruments, Boulder, CO) as previously described (26). Standard curves were obtained and used for quantitative measurements.

Morphometry and histopathology

Collagen deposition within the heart was evaluated using picrosirius red-stained, 4-μm, 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections as documented previously (12). Additional sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin were used to measure myocyte cross-sectional area in approximately 100 cardiomyocytes from two sections per rat (×400 magnification) as previously described (12). Histological analysis was completed using a Leica DM4000B microscope (Bannockburn, IL) with a tandem Leica DFC digital camera and Simple PCI version 6.0 software as well as an Olympus polarizing microscope system (Center Valley, PA) equipped with a Digital SPOT RT, 3-pass capture, thermoelectrically cooled charge-coupled camera (Sterling Heights, MI) and SPOT Advanced software. Adobe Photoshop Creative Suite 3 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA) was used to calculate the ratios of collagen-positive stained pixels to unstained pixels in each photomicrograph (four randomized quadrant field images per rat, magnified ×200).

In situ ROS production

ROS was determined using dihydroethidium (DHE) as previously described (12). The resulting images were analyzed at ×400 using a fluorescence microscope (Leica DM4000B; excitation = 510–550 nm, emission = 590 nm for DHE; excitation = 330–380 nm, emission = 420 nm for 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) connected to a Leica DFC digital camera. The fluorescent signal intensities were analyzed within the heart using Simple PCI version 6.0 software. All data are presented as average gray-scale intensities ± sem.

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± sem. For all endpoints, one-way ANOVA evaluated significant effects among the groups. Significant interactions between the groups were further characterized using Bonferroni post hoc tests. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

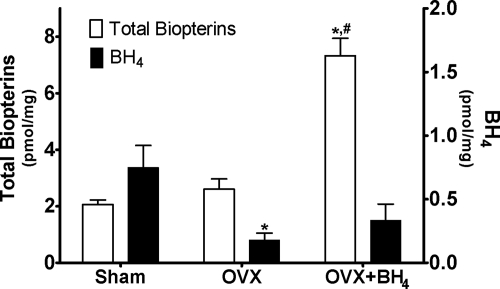

Cardiac biopterin and BH4 levels

Figure 1 depicts total cardiac biopterin and BH4 levels from sham, OVX, and OVX BH4-treated rats. Supplementation with BH4 (OVX+BH4) was associated with more than a 3-fold increase in myocardial biopterin concentrations compared with untreated sham and OVX littermates (P < 0.001). This confirmed that the administered BH4 reached the heart. As expected, estrogen depletion by surgical oophorectomy was associated with a 3.2-fold reduction in cardiac BH4 when compared with levels in sham-operated littermates (P < 0.05). Exogenous BH4 supplementation attenuated this OVX-associated fall in cardiac BH4 concentration but did not restore levels to those measured in sham rats.

Fig. 1.

Cardiac concentrations of total biopterins are shown as white bars, and BH4 values are shown as black bars from sham (n = 8), OVX (n = 8), and OVX+BH4 (n = 7) rats. Data are mean ± sem. *, P < 0.001 compared with sham; #, P < 0.001 compared with OVX.

Physical characteristics and hemodynamics

The effects of OVX and BH4 supplementation on body and heart weight are shown in Table 1. Before BH4 or vehicle treatment, there were no differences in body weight or systolic blood pressure (SBP) among the three cohorts. Serum estradiol levels were significantly less in OVX rats compared with the sham group (sham 34.8 ± 3.4 pg/ml vs. OVX 5.5 ± 0.5 pg/ml; P < 0.001). At the end of the study, the OVX and OVX+BH4 rats were 13 and 16% heavier, respectively, than sham-operated controls (P < 0.001 for each), corroborating previous reports from this and other laboratories that deprivation of estrogens leads to increased body mass (10, 12, 27, 28). Likewise, the heart weights from the OVX rats were substantially higher compared with the sham group (sham 830 ± 17 mg vs. OVX 939 ± 35 mg; P < 0.01). BH4 had no effect on the OVX-induced heart weight increase. Normalized heart weights (heart weight/body weight) were similar among the three groups.

Table 1.

Body and heart weight values

| Variables | Sham (n = 13) | OVX (n = 9) | OVX + BH4 (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 239 ± 2 | 269 ± 7a | 277 ± 5a |

| Heart weight (mg) | 830 ± 17 | 939 ± 35b | 905 ± 20 |

| Heart weight/body weight (mg/g) | 3.47 ± 0.07 | 3.50 ± 0.13 | 3.27 ± 0.05 |

Data are expressed as mean ± sem. P values are compared with sham.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.01.

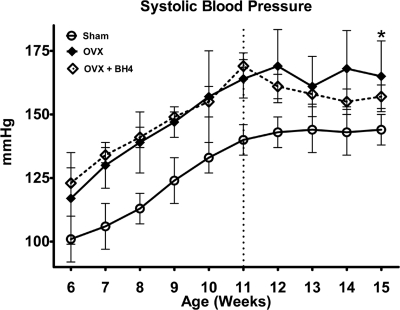

Progressive increases in SBP occurred in sham and OVX rats from 5–11 wk (Fig. 2). Similar to earlier findings (11, 12), substantial rises in blood pressure were observed by wk 6 in OVX rats compared with intact littermates (P < 0.0001), and this larger increase in SBP continued throughout the duration of the 15-wk study. Although there was a tendency for BH4 administration to limit the exacerbated hypertension, there were no significant differences between the OVX groups during the 4-wk supplementation period.

Fig. 2.

Tail-cuff systolic blood pressures in sham (n = 13), OVX (n = 9), and OVX+BH4 (n = 10) conscious mRen2.Lewis rats. Values are means ± sem. *, P < 0.01 compared with sham.

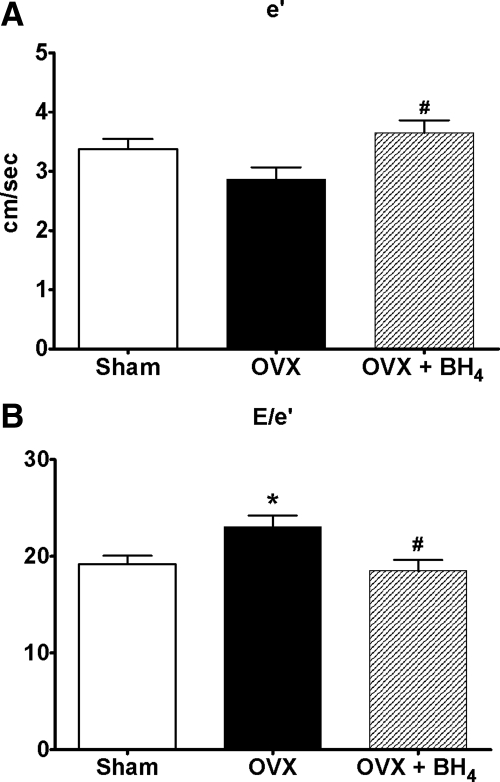

Heart rate and diastolic function

Table 2 shows the effects of ovarian hormonal loss and BH4 supplementation on heart rate and the conventional Doppler indices of diastolic function. Although heart rate and the more load-dependent, conventional measures of diastolic function were similar among groups (Table 2), the loss of ovarian hormones led to modest reductions in ventricular relaxation, (or e′) and elevations in LV filling pressure (or E/e′) (P < 0.001) when compared with Doppler indices from intact-littermates (Fig. 3). Importantly, 4 wk of BH4 treatment restored ventricular lusitropy and reduced filling pressures to that of sham-operated littermates. Specifically, BH4 increased mitral annular velocity (e′) by 27% and reduced Doppler-derived filling pressures (E/e′) by 20% when compared with untreated OVX rats.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic indices of diastolic function

| Variables | Sham (n = 13) | OVX (n = 9) | OVX + BH4 (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emax (cm/sec) | 63 ± 2 | 64 ± 4 | 64 ± 3 |

| Amax (cm/sec) | 42 ± 2 | 40 ± 3 | 40 ± 2 |

| E/A | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| Edec time (sec) | 0.057 ± 0.002 | 0.062 ± 0.003 | 0.060 ± 0.003 |

Data are expressed as mean ± sem. P values are compared with sham. Emax, Maximum early transmitral filling velocity; Amax, maximum late transmitral filling velocity; E/A, early-to-late transmitral filling ratio; Edec time, early-filling deceleration time.

Fig. 3.

A, Myocardial relaxation indicated by early mitral annular velocity (e′) in sham (n = 13), OVX (n = 9), and OVX+BH4 (n = 10) mRen2.Lewis rats. Data are mean ± sem. #, P < 0.05 compared with OVX. B, Ratio of early transmitral filling velocity to mitral annular velocity (E/e′) in sham (n = 13), OVX (n = 9), and OVX+BH4 (n = 10) rats. Data are expressed as mean ± sem. *, P < 0.05 compared with sham; #, P < 0.05 compared with OVX.

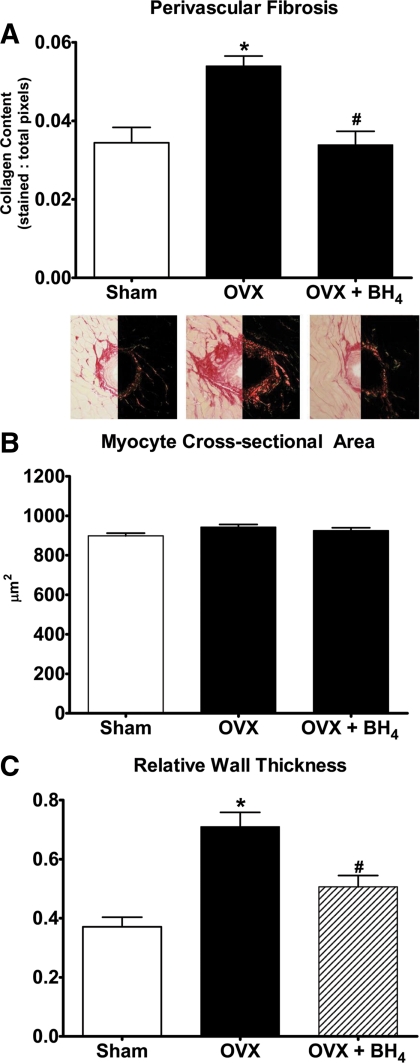

LV structural characteristics and systolic function

Figure 4A demonstrates a 1.6-fold increase in perivascular fibrosis in OVX mRen2.Lewis rats compared with their estrogens-intact littermates (P < 0.005). OVX had no effect on myocyte cross-sectional area (Fig. 4B). Chronic BH4 supplementation in OVX mRen2.Lewis rats reversed or prevented the excess collagen deposition (37%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A), without altering myocyte size (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

A, Quantification and representative picrosirius red staining revealing perivascular collagen in the hearts of sham (n = 9), OVX (n = 9), and OVX+BH4 (n = 10) rats. Values are mean ± sem. *, P < 0.05 compared with sham; #, P < 0.05 compared with OVX. Magnification, ×200. B, Myocyte cross-sectional areas of cardiac myocytes from sham (n = 9), OVX (n = 9), and OVX+BH4 (n = 10) mRen2.Lewis hearts. Data are mean ± sem. C, RWT of sham (n = 13), OVX (n = 9), and OVX+BH4 (n = 10) mRen2.Lewis rats. Data are mean ± sem. *, P < 0.05 compared with sham; #, P < 0.05 compared with OVX.

M-mode measurements of LV dimensions and wall thicknesses are summarized in Table 3. The loss of ovarian hormones led to a 25% increase in posterior wall thickness (P < 0.01) (Table 3), which, combined with no alterations in the LVEDD, yielded a robust 2-fold increase in RWT compared with sham-operated rats (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4C). Treatment with BH4 reversed this effect because the RWT of the OVX+BH4 compared with OVX was 0.51 ± 0.04 vs. 0.71 ± 0.05 cm, respectively (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3C). Systolic function indicated as the percent fractional shortening was similar among the three groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

M-mode-derived measures of LV dimension, wall thickness, and systolic function

| Variables | Sham (n = 13) | OVX (n = 9) | OVX + BH4 (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 251 ± 8 | 245 ± 12 | 237 ± 6 |

| LVEDD (cm) | 0.68 ± 0.02 | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 0.67 ± 0.02 |

| LVESD (cm) | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 0.02 |

| RWTed (cm) | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.71 ± 0.05a | 0.51 ± 0.04a,b |

| PWTed (cm) | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01a | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| AWTed (cm) | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.02 |

| % FS | 47 ± 1 | 46 ± 1 | 43 ± 2 |

Data are expressed as mean ± sem. LVESD, LV end-systolic dimension; RWTed, RWT at end diastole; PWTed, posterior wall thickness at end diastole; AWTed, anterior wall thickness at end diastole; FS, fractional shortening.

P < 0.0001 compared with sham.

P < 0.05 compared with OVX.

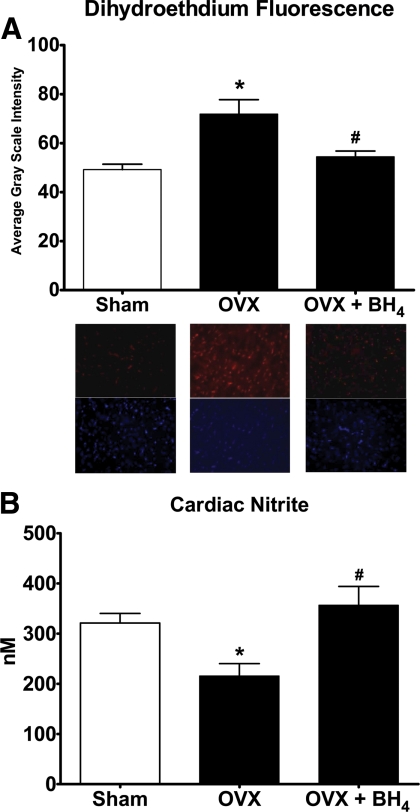

ROS and nitrite profile

Similar to our earlier findings, (12), DHE staining of the cardiac tissue illustrated abundant O2− production within the myocytes of OVX rats compared with the estrogens-intact mRen2.Lewis rats (Fig. 5A). This increase in ROS generation was associated with a 33% reduction in cardiac tissue nitrite availability, or NO release, in the OVX group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5B). In hearts from OVX+BH4 rats, the intensity of the fluorescent product, 2-hydroxyethidium, was diminished to a level found in hearts from SHAM rats (Fig. 5A). The decreased O2− production in the OVX+BH4 group corresponded to a 1.7-fold increase in available nitrite content (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 5.

A, Quantification and representative images illustrating the effect of OVX and BH4 supplementation on cardiac levels of fluorescent 2-hydroxyethidium from DHE staining in sham (n = 8), OVX (n = 8), and OVX+BH4 (n = 8) rats. Fluorescent images are shown at ×400 magnification where red indicates DHE staining and blue indicates nuclei. Data are mean ± sem. *, P < 0.05 compared with sham; #, P < 0.05 compared with OVX. B, Cardiac concentrations of nitrite as an indicator of nitric oxide availability from sham (n = 8), OVX (n = 8), and OVX+BH4 (n = 8) rat hearts. Data are mean ± sem. *, P < 0.05 compared with sham; #, P < 0.05 compared with OVX.

Discussion

The major findings of this study are 1) loss of estrogens by surgical OVX results in myocardial BH4 deficiency in mRen2.Lewis rats; 2) this deficiency is associated with diastolic dysfunction, adverse LV remodeling, increases in cardiac O2− production, and reduced cardiac NO release; and 3) BH4 supplementation reverses all these changes except the elevated heart weight induced by OVX. The observation that the loss of estrogens is accompanied by increased body weight explains the presence of a compensatory increase in cardiac mass likely due to excessive lengthening of cardiac myocytes and ventricular dilation, (29) and/or from the loss of estrogen-stimulated cGMP activity (30). Collectively, this study supports our original hypothesis that diminished BH4 availability after the loss of ovarian hormones, and specifically estrogens, leads to nNOS uncoupling within the heart of the OVX mRen2.Lewis rat. Under this situation, O2− rather than NO becomes the product of nNOS activity, ultimately contributing to the diastolic dysfunction phenotype (12). It is therefore plausible that BH4 supplementation may represent a rational approach to the management of diastolic dysfunction in women due to either surgically induced or natural menopause. The benefits of BH4 supplementation may be due to suppression of ROS generation alone or in combination with enhanced NO release (12) and/or a direct antioxidant action (31).

Extensive strides have been made to establish the cardioprotective role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in the regulation of cardiac function (18, 32–35). However, efforts targeting equivocal appreciation of cardiac (36, 37) and vascular nNOS (38) have been far more limited. It is important to note that nNOS compared with the other NOS isoforms is more likely to produce superoxide when the enzyme is uncoupled (39). In an earlier report by Yamaleyeva et al. (40), renal eNOS decreased after OVX in mRen2.Lewis rats, whereas nNOS protein expression increased. In their study, selective inhibition of nNOS attenuated the exacerbated increase in SBP characteristic of this model. Likewise, we observed overexpression of cardiac nNOS in OVX mRen2.Lewis rats compared with estrogens-intact littermates but no difference in cardiac eNOS between groups (12). Intrigued by the possibility that the excess nNOS had a functional role in the model, we administered the specific nNOS inhibitor L-VNIO. The L-VNIO treatment led to cardioprotection in the OVX mRen2.Lewis model, effects we proposed were due to blockade of the uncoupled nNOS activity, because ROS generation was decreased, whereas NO increased in the heart (12). Taken together with the finding that cardiac BH4 levels were suppressed in OVX rats compared with littermates with intact estrogens (12) and that deficiency of estrogens has been reported to cause decreased synthesis of BH4 by the de novo pathway (41) provides the rational basis for the use of BH4 supplementation in our model. BH4 is not only an essential NOS cofactor, it has an important role in maintaining the structure of all NOS isoforms by stabilizing the active or coupled form of the enzyme, which leads to the production of NO rather than superoxide, the end-product of nNOS uncoupling. These current data complement and extend these previous observations by showing that BH4 supplementation halts the functional and structural changes in the OVX mRen2.Lewis hearts, even in the presence of exacerbated increases in blood pressure induced by OVX. Although the lack of an overt change in blood pressure by BH4 might raise questions, others report similar findings. In a clinically relevant canine model of cardiopulmonary bypass with hypothermic cardiac arrest, a 30-min infusion of BH4 before reperfusion resulted in better systolic and diastolic functional recovery compared with saline vehicle-treated dogs, and these effects occurred without overt changes in systemic blood pressure (42). Moreover, in a small, randomized, double-blind placebo control trial in hypercholesterolemia patients, 4 wk of oral BH4 treatment restored the forearm blood flow response to acetylcholine and decreased plasma markers of oxidative stress compared with placebo, and these effects were independent of blood pressure (43). Whether BH4 affected endothelial function in our model is not known. Nonetheless, the observed cardioprotective effects indicate that BH4 availability is important for maintaining cardiac NO synthesis and low superoxide production.

Although the heart data are limited, the link between estrogens and BH4 is highlighted in a report by Lam et al. (44) that showed decreased bioavailability of BH4 in the rat vasculature after OVX. Another study has shown that estrogens can directly increase BH4 through up-regulation of GTPCH mRNA and activity in cultured endothelial cells (18). Moreover, 17β-estradiol therapy normalized aortic BH4 levels and suppressed O2− generation (41). Although it is not known whether the decreased concentration of cardiac BH4 in hearts from the OVX mRen2.Lewis rats was due to the withdrawal of the regulation of estrogens on GTPCH, resetting the nNOS system through BH4 supplementation was a sufficient means by which to normalize diastolic function, attenuate remodeling, and restore myocardial antioxidant capacity to that of littermates with intact estrogens.

Independent of the status of estrogens, equivalent doses of BH4 as used in the present study have repeatedly been shown to preserve cardiac function and prevent remodeling after myocardial infarction (45, 46). In isolated hearts from Dahl salt-sensitive rats, administration of a BH4 donor increased LV developed pressure and recovery as measures of ischemia resistance (47). Additionally, in a pressure-overload mouse model, BH4 reversed cardiac hypertrophy and improved heart function as documented in improved sarcomere activity and calcium handling (48). The benefit of BH4 extends beyond in vivo and in vitro experiments. In a pilot study designed to establish a dose-response curve and determine the duration of oral BH4 therapy in uncontrolled human hypertensive patients, BH4 significantly reduced systolic blood pressure and improved flow-mediated vasodilation (49).

The first limitation of the present study is that these studies were conducted in a rodent oophorectomized model, which is not an identical mimetic of naturally occurring menopause. However, the phenotypic characteristics of the mRen2.Lewis after depletion of ovarian hormones, including LV hypertrophy and exacerbated hypertension, are similar to the pathophysiological changes occurring in postmenopausal women (50, 51).

Second, the actual accumulated levels of BH4 detected within the myocardial tissue of the BH4-treated OVX rats were not significantly increased compared with OVX. These observations are likely due to the dual regulation of BH4 metabolism that can lead to rapid oxidation of BH4 to BH2 and simultaneous recycling of BH4 from BH2 by the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (52, 53). Channon and colleagues (54) eloquently described this phenomenon within the vasculature where they suggest that the overall availability of BH4 within the vascular tissue is the summation of BH4 synthesis, BH4 oxidation, and finally, its recycling from BH2. In our studies, the HPLC biopterin assay cannot determine the rate of oxidation.

Finally, this study focused on proposed nNOS uncoupling as the source of ROS generation leading to diastolic dysfunction and LV remodeling. Oxidative stress can also occur via alternative processes, including xanthine oxidase, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases, or cytochrome P450. However, our rationale to explore the nNOS uncoupling phenomenon in this model was based on the paradoxical increase in cardiac nNOS expression after oophorectomy (12). This is an important consideration given the fact that until recently, it had been assumed that nNOS was a positive contributor to cardiovascular function through the production of NO as opposed to the maladaptive characteristics (increased ROS and decreased NO) now demonstrated in this study. Targeting individual components of the pathway allows for the progressive understanding of this complex system and the extrapolation of potential clinical applications.

In summary, we show that BH4 supplementation led to significant improvements in diastolic function, attenuation of cardiac remodeling, and reductions in oxidative stress in the mRen2.Lewis female after ovarian hormonal loss. We propose that the restorative effects are due to BH4 therapy recoupling the NOS activity, which shifts the maladaptive pathway of ROS generation back to coupled, adaptive catalytic activity. In light of the controversy surrounding estrogen replacement therapy, it is plausible that BH4 may be a viable therapeutic option for diastolic patients because it is currently used clinically for other syndromes such as phenylketonuria. Phenylketonuria patients who have either phenylalanine hydroxylase mutations or are BH4 deficient, therapeutically receive BH4, the necessary cofactor for phenylalanine hydroxylase activity, just as it is for NOS activity. In those patients that are responsive to BH4, the level of circulating phenylalanine is significantly diminished, sparing the individuals from developmental disorders, cognitive impairment, and seizures (55–57). Importantly, these patients exhibit minimal side effects (58), providing hope that BH4 supplementation could provide beneficial effects in patients with diastolic dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

We extend sincere appreciation to Marina Lin, M.S., for her technical contributions; Timothy T. Houle, Ph.D., for his statistical expertise; and Addie Larimore for her editorial assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health R01-AG033727-01 (to L.G.), KO8-AG026764-05 Paul Beeson award (to L.G.), HL-058091 (to D.B.K.-S.), R01 GM077352 (to A.F.C.), 2PO1 HL-051952 (to C. M. Ferrario), and American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 0855601GH (to A.F.C.). Support was limited to funding.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- B

- Oxidized biopterin

- BH2

- dihydrobiopterin

- BH4

- tetrahydrobiopterin

- DHE

- dihydroethidium

- eNOS

- endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- GTPCH

- guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I

- LV

- left ventricular

- LVEDD

- LV end diastolic dimension

- L-VNIO

- N5-(1-Imino-3-butenyl)-1-ornithine

- nNOS

- neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- OVX

- ovariectomized

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- RWT

- relative wall thickness

- SBP

- systolic blood pressure.

References

- 1. Deschepper CF, Llamas B. 2007. Hypertensive cardiac remodeling in males and females: from the bench to the bedside. Hypertension 49:401–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. 2006. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 355:251–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Hellermann-Homan JP, Killian J, Yawn BP, Jacobsen SJ. 2004. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA 292:344–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wenger NK, Speroff L, Packard B. 1993. Cardiovascular health and disease in women. N Engl J Med 329:247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Du XJ, Fang L, Kiriazis H. 2006. Sex dimorphism in cardiac pathophysiology: experimental findings, hormonal mechanisms, and molecular mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther 111:434–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Brokat S, Tschope C. 2007. Role of gender in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 49:241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Smith G, Fish RH, Steiner JF, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM. 2003. Gender, age, and heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function. J Am Coll Cardiol 41:217–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Kinugawa S, Goto D, Takeshita A. 2006. Clinical characteristics and outcome of hospitalized patients with heart failure in Japan. Circ J 70:1617–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. 2002. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Groban L, Yamaleyeva LM, Westwood BM, Houle TT, Lin M, Kitzman DW, Chappell MC. 2008. Progressive diastolic dysfunction in the female mRen(2).Lewis rat: influence of salt and ovarian hormones. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 63:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chappell MC, Westwood BM, Yamaleyeva LM. 2008. Differential effects of sex steroids in young and aged female mRen2.Lewis rats: a model of estrogen and salt-sensitive hypertension. Gend Med 5 Suppl A:S65–S75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jessup JA, Zhang L, Chen AF, Presley TD, Kim-Shapiro DB, Wang H, Groban L. 3 February 2011. nNOS inhibition improves diastolic function and reduces oxidative stress in ovariectomized mRen2.Lewis rats. Menopause 10.1097/gme.0b013e31820390a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Massion PB, Feron O, Dessy C, Balligand JL. 2003. Nitric oxide and cardiac function: ten years after, and continuing. Circ Res 93:388–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Molero L, García-Durán M, Diaz-Recasens J, Rico L, Casado S, López-Farré A. 2002. Expression of estrogen receptor subtypes and neuronal nitric oxide synthase in neutrophils from women and men: regulation by estrogen. Cardiovasc Res 56:43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. García-Durán M, de Frutos T, Díaz-Recasens J, García-Gálvez G, Jiménez A, Montón M, Farré J, Sánchez de Miguel L, González-Fernández F, Arriero MD, Rico L, García R, Casado S, López-Farré A. 1999. Estrogen stimulates neuronal nitric oxide synthase protein expression in human neutrophils. Circ Res 85:1020–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qian X, Jin L, Lloyd RV. 1999. Estrogen downregulates neuronal nitric oxide synthase in rat anterior pituitary cells and GH3 tumors. Endocrine 11:123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salhab WA, Shaul PW, Cox BE, Rosenfeld CR. 2000. Regulation of types I and III NOS in ovine uterine arteries by daily and acute estrogen exposure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278:H2134–H2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miyazaki-Akita A, Hayashi T, Ding QF, Shiraishi H, Nomura T, Hattori Y, Iguchi A. 2007. 17β-Estradiol antagonizes the down-regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase and GTP cyclohydrolase I by high glucose: relevance to postmenopausal diabetic cardiovascular disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320:591–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Serova LI, Maharjan S, Sabban EL. 2005. Estrogen modifies stress response of catecholamine biosynthetic enzyme genes and cardiovascular system in ovariectomized female rats. Neuroscience 132:249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Serova LI, Filipenko M, Schilt N, Veerasirikul M, Sabban EL. 2006. Estrogen-triggered activation of GTP cyclohydrolase 1 gene expression: role of estrogen receptor subtypes and interaction with cyclic AMP. Neuroscience 140:1253–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Giovanelli J, Campos KL, Kaufman S. 1991. Tetrahydrobiopterin, a cofactor for rat cerebellar nitric oxide synthase, does not function as a reactant in the oxygenation of arginine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:7091–7095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Podjarny E, Benchetrit S, Rathaus M, Pomeranz A, Rashid G, Shapira J, Bernheim J. 2003. Effect of tetrahydrobiopterin on blood pressure in rats after subtotal nephrectomy. Nephron Physiol 94:6–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang X, Hattori Y, Satoh H, Iwata C, Banba N, Monden T, Uchida K, Kamikawa Y, Kasai K. 2007. Tetrahydrobiopterin prevents endothelial dysfunction and restores adiponectin levels in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 555:48–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamamizu K, Shinozaki K, Ayajiki K, Gemba M, Okamura T. 2007. Oral administration of both tetrahydrobiopterin and l-arginine prevents endothelial dysfunction in rats with chronic renal failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 49:131–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zheng JS, Yang XQ, Lookingland KJ, Fink GD, Hesslinger C, Kapatos G, Kovesdi I, Chen AF. 2003. Gene transfer of human guanosine 5′-triphosphate cyclohydrolase I restores vascular tetrahydrobiopterin level and endothelial function in low renin hypertension. Circulation 108:1238–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Presley TD, Morgan AR, Bechtold E, Clodfelter W, Dove RW, Jennings JM, Kraft RA, King SB, Laurienti PJ, Rejeski WJ, Burdette JH, Kim-Shapiro DB, Miller GD. 2011. Acute effect of a high nitrate diet on brain perfusion in older adults. Nitric Oxide 24:34–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lemieux C, Picard F, Labrie F, Richard D, Deshaies Y. 2003. The estrogen antagonist EM-652 and dehydroepiandrosterone prevent diet- and ovariectomy-induced obesity. Obes Res 11:477–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lobo MJ, Remesar X, Alemany M. 1993. Effect of chronic intravenous injection of steroid hormones on body weight and composition of female rats. Biochem Mol Biol Int 29:349–358 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Onodera T, Tamura T, Said S, McCune SA, Gerdes AM. 1998. Maladaptive remodeling of cardiac myocyte shape begins long before failure in hypertension. Hypertension 32:753–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Babiker FA, De Windt LJ, van Eickels M, Thijssen V, Bronsaer RJ, Grohé C, van Bilsen M, Doevendans PA. 2004. 17β-Estradiol antagonizes cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by autocrine/paracrine stimulation of a guanylyl cyclase A receptor-cyclic guanosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase pathway. Circulation 109:269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shen RS, Zhang YX. 1991. Antioxidation activity of tetrahydrobiopterin in pheochromocytoma PC 12 cells. Chem Biol Interact 78:307–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Di Napoli P, Chierchia S, Taccardi AA, Grilli A, Felaco M, De Caterina R, Barsotti A. 2007. Trimetazidine improves post-ischemic recovery by preserving endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in isolated working rat hearts. Nitric Oxide 16:228–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones SP, Greer JJ, Kakkar AK, Ware PD, Turnage RH, Hicks M, van Haperen R, de Crom R, Kawashima S, Yokoyama M, Lefer DJ. 2004. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase overexpression attenuates myocardial reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286:H276–H282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Manickavasagam S, Ye Y, Lin Y, Perez-Polo RJ, Huang MH, Lui CY, Hughes MG, McAdoo DJ, Uretsky BF, Birnbaum Y. 2007. The cardioprotective effect of a statin and cilostazol combination: relationship to Akt and endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 21:321–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Murphy E, Steenbergen C. 2007. Cardioprotection in females: a role for nitric oxide and altered gene expression. Heart Fail Rev 12:293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burkard N, Williams T, Czolbe M, Blömer N, Panther F, Link M, Fraccarollo D, Widder JD, Hu K, Han H, Hofmann U, Frantz S, Nordbeck P, Bulla J, Schuh K, Ritter O. 2010. Conditional overexpression of neuronal nitric oxide synthase is cardioprotective in ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation 122:1588–1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jones SP, Girod WG, Huang PL, Lefer DJ. 2000. Myocardial reperfusion injury in neuronal nitric oxide synthase deficient mice. Coron Artery Dis 11:593–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Han G, Ma H, Chintala R, Miyake K, Fulton DJ, Barman SA, White RE. 2007. Nongenomic, endothelium-independent effects of estrogen on human coronary smooth muscle are mediated by type I (neuronal) NOS and PI3-kinase-Akt signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293:H314–H321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. 2001. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J 357:593–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yamaleyeva LM, Gallagher PE, Vinsant S, Chappell MC. 2007. Discoordinate regulation of renal nitric oxide synthase isoforms in ovariectomized mRen2.Lewis rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292:R819–R826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lam KK, Lee YM, Hsiao G, Chen SY, Yen MH. 2006. Estrogen therapy replenishes vascular tetrahydrobiopterin and reduces oxidative stress in ovariectomized rats. Menopause 13:294–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Szabo G, Seres L, Soos P, Gorenflo M, Merkely B, Horkay F, Karck M, Radovits T. 15 February 2011. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves cardiac and pulmonary function after cardiopulmonary bypass. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cosentino F, Hürlimann D, Delli Gatti C, Chenevard R, Blau N, Alp NJ, Channon KM, Eto M, Lerch P, Enseleit F, Ruschitzka F, Volpe M, Lüscher TF, Noll G. 2008. Chronic treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin reverses endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress in hypercholesterolaemia. Heart 94:487–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lam KK, Ho ST, Yen MH. 2002. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves vascular endothelial function in ovariectomized rats. J Biomed Sci 9:119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Masano T, Kawashima S, Toh R, Satomi-Kobayashi S, Shinohara M, Takaya T, Sasaki N, Takeda M, Tawa H, Yamashita T, Yokoyama M, Hirata K. 2008. Beneficial effects of exogenous tetrahydrobiopterin on left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in rats: the possible role of oxidative stress caused by uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circ J 72:1512–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wajima T, Shimizu S, Hiroi T, Ishii M, Kiuchi Y. 2006. Reduction of myocardial infarct size by tetrahydrobiopterin: possible involvement of mitochondrial KATP channels activation through nitric oxide production. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 47:243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. An J, Du J, Wei N, Xu H, Pritchard KA, Jr, Shi Y. 2009. Role of tetrahydrobiopterin in resistance to myocardial ischemia in Brown Norway and Dahl S rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297:H1783–H1791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moens AL, Takimoto E, Tocchetti CG, Chakir K, Bedja D, Cormaci G, Ketner EA, Majmudar M, Gabrielson K, Halushka MK, Mitchell JB, Biswal S, Channon KM, Wolin MS, Alp NJ, Paolocci N, Champion HC, Kass DA. 2008. Reversal of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis from pressure overload by tetrahydrobiopterin: efficacy of recoupling nitric oxide synthase as a therapeutic strategy. Circulation 117:2626–2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Porkert M, Sher S, Reddy U, Cheema F, Niessner C, Kolm P, Jones DP, Hooper C, Taylor WR, Harrison D, Quyyumi AA. 2008. Tetrahydrobiopterin: a novel antihypertensive therapy. J Hum Hypertens 22:401–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Agabiti-Rosei E, Muiesan ML. 2002. Left ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure in women. J Hypertens Suppl 20:S34–S38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Oberman A, Prineas RJ, Larson JC, LaCroix A, Lasser NL. 2006. Prevalence and determinants of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy among a multiethnic population of postmenopausal women (The Women's Health Initiative). Am J Cardiol 97:512–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McGuire JJ. 2003. Anticancer antifolates: current status and future directions. Curr Pharm Des 9:2593–2613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nzila A, Ward SA, Marsh K, Sims PF, Hyde JE. 2005. Comparative folate metabolism in humans and malaria parasites (part II): activities as yet untargeted or specific to Plasmodium. Trends Parasitol 21:334–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Crabtree MJ, Tatham AL, Hale AB, Alp NJ, Channon KM. 2009. Critical role for tetrahydrobiopterin recycling by dihydrofolate reductase in regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase coupling: relative importance of the de novo biopterin synthesis versus salvage pathways. J Biol Chem 284:28128–28136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Burlina A, Blau N. 2009. Effect of BH4 supplementation on phenylalanine tolerance. J Inherit Metab Dis 32:40–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cerone R, Schiaffino MC, Fantasia AR, Perfumo M, Birk Moller L, Blau N. 2004. Long-term follow-up of a patient with mild tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab 81:137–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lambruschini N, Perez-Duenas B, Vilaseca MA, Mas A, Artuch R, Gassio R, Gomez L, Gutierrez A, Campistol J. 2005. Clinical and nutritional evaluation of phenylketonuric patients on tetrahydrobiopterin monotherapy. Mol Genet Metab 86(Suppl 1):S54–S60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Trefz FK, Belanger-Quintana A. 2010. Sapropterin dihydrochloride: a new drug and a new concept in the management of phenylketonuria. Drugs Today (Barc) 46:589–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]