Abstract

The continuing miniaturization of digital circuits and the development of low power radio systems coupled with continuing studies into the neurophysiology and dynamics of insect flight are enabling a new class of implantable interfaces capable of controlling insects in free flight for extended periods. We provide context for these developments, review the state-of-the-art and discuss future directions in this field.

Keywords: H, insect flight, micro air vehicle (MAV), telemetry, cyborg insect, brain machine interface (BMI)

Introduction

Insects exhibit some amazing modes of locomotion. They float, swim, crawl, jump, run (even bipedally), and fly. They do this with such efficiency, sophistication, and elegance of function across a vast size range (the smallest insect is 1/5 of a millimeter across, the largest insects can weigh 100 g and be over 20 cm long) that they have mastered locomotion on almost every terrain on Earth.

The adaptations which enable insects to do these things have inspired human art, science, and engineering for centuries (e.g., Tipton, 1976). On the ground, the science of insect locomotion has informed several generations of legged robots (e.g., Full and Koditschek, 1999; Delcomyn, 2004; Lehmann, 2004; Riztman et al., 2004), from the crawling machines of the 1980s (like MIT's Ghengis; Brooks, 1991) to the more modern Rhex capable of successfully traversing complex terrain (Altendorfer et al., 2001). In the air, a great deal of research spanning decades is beginning to tease out the complex interplay between aerodynamics, mechanical construction, and neurophysiology that enables something as small as a fruitfly to fly so incredibly well. Enabled by advances in microfabrication techniques (Tanaka and Wood, 2010) and considerable progress in our understanding of insect flight (Pringle, 1957; Machin and Pringle, 1959, 1960; Machin et al., 1962; Ikeda and Boettiger, 1965; Leston et al., 1965; Ellington, 1984; Tu and Dickinson, 1994, 1996; Ellington et al., 1996; Dickinson and Tu, 1997; Dickinson et al., 1999, 2000; Josephson et al., 2000a,b) engineers are starting to build tiny, sub-gram scale, flying robots.

Building very small flyers which can fly well in real environments is a difficult task, however, hampered not just by knowledge of insect flight, but current technological limitations. A housefly is about 8 mm long and weighs 1 g; its wings beat approximately 200 times a second; during each stroke, tiny muscles make subtle adjustments to the trajectory of the wings to generate the forces required to move it where it wants to go (Tu and Dickinson, 1994, 1996; Dickinson and Tu, 1997; Dickinson et al., 1999, 2000). As it does this, it integrates data from a variety of sensors on its body which provide airflow information, gyroscopic information, and visual flow information; it computes and then compensates for the horizon, for incoming obstacles, and for constantly changing wind gusts and does this so efficiently, that it can fly for hours a day and could fly a mile or two in single stretch if really had to. By comparison, the Delfly Micro (de Croon et al., 2009), arguably one of the smallest untethered, instrumented air vehicles, weighs 3 g and has a 10 cm wingspan, can fly for 3 min on a battery which constitutes 1/3 of its weight and requires a human operator to perform all flight functions. To the authors’ knowledge, the smallest, non-autonomous flying machine is the microrobotic fly built at the Harvard Microrobotics Laboratory, weighing in at 60 mg (Wood, 2008). While these systems are rapidly evolving, they are currently hampered by the energy and power density of existing fuel sources and the difficulty in replicating the flight dynamics and mechanical efficiencies of very small flyers. Insects have flight performance (as measured by distance and speed vs. payload and maneuverability) as-yet unmatched by man-made craft of similar size. Very recently, several groups have attempted to circumvent such problems by merging synthetic control and communication systems into living insects with the aim to control free flight.

Technology

Wireless telemetry and control

The development of wireless telemetry systems for small, free-flying, and walking insects began in the early 1990s with applications ranging from neuromuscular recording (Kutsch et al., 1993, 2003; Kuwana et al., 1995, 1999; Fischer et al., 1996; Holzer and Shimoyama, 1997; Fischer and Ebert, 1999; Fischer and Kutsch, 1999; Ando et al., 2002; Kutsch, 2002; Ando and Kanzaki, 2004; Colot et al., 2004; Cooke et al., 2004; Takeuchi and Shimoyama, 2004; Mohseni et al., 2005; Lemmerhirt et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2008) to using radio transmitters to study the long-range movements of insects (Hedin and Ranius, 2002; Sword et al., 2005; Holland, 2006; Wikelski et al., 2006, 2010; Pasquet et al., 2008). Table 1 shows the wireless systems used for neuromuscular recording and stimulation of free-flying insects. All of the early devices employed custom-made radios hand-assembled from surface mount electronics components and lacked digital processing, on-board memory or programmability. Detection of emitted signals was usually carried out using complimentary radio receivers or spectrum analyzers (and the relevant biological information was de-convolved from the analog radio signals). Kutsch et al. (1993) developed a 0.42 g telemetry backpack (including battery) for a locust (Schistocerca gregaria, 3.0–3.5 g, payload capacity 0.5 g). The backpack had a single channel transmitter to wirelessly acquire electromyograms (EMG) of a single flight muscle of interest. Their modified backpack had a dual channel transmitter and it allowed the researchers to tease out the function of the locust's proprioceptors (Fischer and Ebert, 1999), a feat difficult or impossible to do with tethered insects. Ando et al. developed a 0.23 g dual channel telemetry backpack to measure and compare EMG's from a pair of flight muscles of a male hawkmoth, Agrius convolvuli, during pheromone-triggered zigzag flight (Kuwana et al., 1999; Ando et al., 2002; Ando and Kanzaki, 2004; Wang et al., 2008).

Table 1.

Representative systems used for neuromuscular recording and/or stimulation of free-flying insects.

| Year | Purpose | Insect, order | Species | Insect mass (g) | System mass (g) | Lifetime | Radio | Radio range (m) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | EMG | Locust, Orthoptera | Schistocerca gregaria | 3.5 | 0.42 | – | 1 ch T | 25 | Kutsch et al. (1993) |

| 1996 | EMG | Locust, Orthoptera | Schistocerca gregaria | 3.5 | 0.55 | – | 2 ch T | 20 | Fischer et al. (1996) |

| 1999 | EMG | Moth, Lepidoptera | Agrius convolvuli | 0.4 | 30 min | 2 ch T | 1 | Kuwana et al. (1999) | |

| 1999 | EMG | Locust, Orthoptera | Schistocerca gregaria | 3.5 | 0.3 | – | 1 ch T | – | Fischer and Ebert (1999) |

| 1999 | EMG | Locust, Orthoptera | Schistocerca gregaria | 3.5 | 0.3 | – | 1 ch T | – | Fischer and Kutsch (1999) |

| 2001 | EMG | Moth, Lepidoptera | Manduca sexta | 0.74 | 3 h | 2 ch T | 2 | Mohseni et al. (2001) | |

| 2002 | EMG | Moth, Lepidoptera | Agrius convolvuli | 0.25 | 30 min | 2 ch T | 5 | Ando et al. (2002) | |

| 2003 | EMG | Locust, Orthoptera | Schistocerca gregaria | 3.5 | 0.2 | – | 1 ch T | – | Kutsch et al. (2003) |

| 2004 | EMG | Moth, Lepidoptera | Agrius convolvuli | 0.25 | – | 2 ch T | – | Ando and Kanzaki (2004) | |

| 2008 | EMG | Moth, Lepidoptera | Agrius convolvuli | 0.23 | – | 2 ch T | 3 | Wang et al. (2008) | |

| 2009, 2010 | Flight control | Beetle, Coleoptera | Mecynorhina torquata | 10 | 1.33 | 30 min active/24 h sleep mode | 8 ch T–R | 20 | Sato et al. (2009a,b), Maharbiz and Sato (2010) |

| 2009† | Flight control | Moth, Lepidoptera | Manduca sexta | 2.5 | 0.65 | – | 3 ch R | – | Bozkurt et al. (2009b) |

| 2009, 2010 | Flight control | Moth, Lepidoptera | Manduca sexta | 2.5 | 1 | – | 4 ch R | Daly et al. (2009, 2010) |

EMG, electromyogram; T, transmitter; R, receiver.

†The system used helium balloons to provide additional lift for the insect.

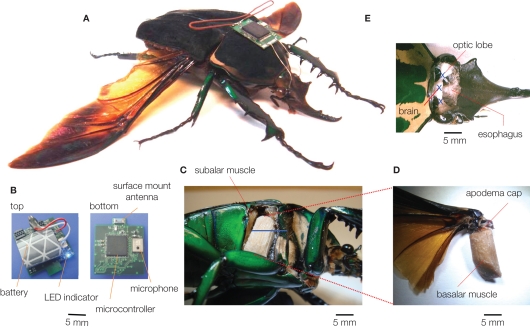

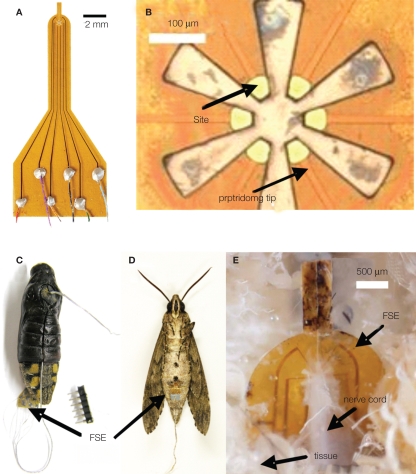

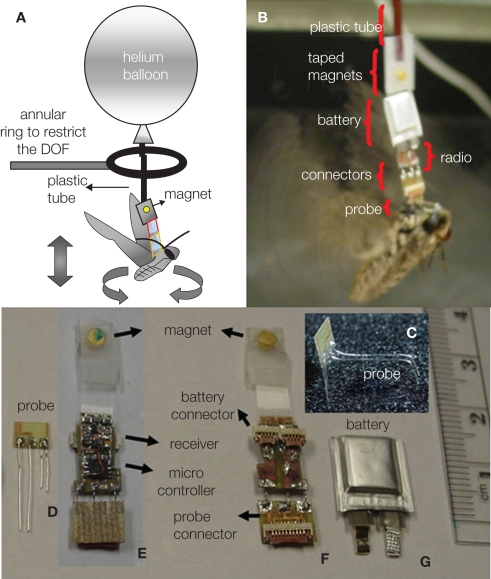

To our best knowledge, three different groups have recently developed wireless systems that can both transmit and receive data from free-flying insects flight control (Figures 1–3). Flight control requiring multiple-channel stimulation, during complex, long-duration controlled flight requires on-board digital processing, memory, and programmability in addition to efficient radio systems. Each group developed systems with different trade-off choices in terms of functionality, weight, and complexity. Sato et al. describe an 8-channel system built around the Texas Instruments CC2431 microcontroller with built-in transceiver; careful programming of the microcontroller allows for half hour of flight time and approximately 24 h of battery life in sleep mode (Figure 1, Sato et al., 2009a,b; Maharbiz and Sato, 2010). The use of surface mount ceramic antennas results in a very small package in terms of size, mass, and inertial effect on the flying insect (Figure 1B). Bozkurt et al. (2009b) developed a custom-built, 2 channel AM receiver which used pulse-position modulation via a super-regenerative architecture which was fed into a PIC12F615 microcontroller (Figure 2). Daly et al. (2009, 2010) developed a custom silicon system-on-chip receiver operating at 3–5 GHz on the 802.15.4a wireless standard which interfaced with an on-board Texas Instruments MP430 microcontroller; the receiver was remarkable for its extremely low-power operation (2.5 mW, 1.4 nJ/bit) for a data rate of 16 Mb/s (Figure 3). Driven primarily by technological developments in ultra-low power distributed sensor networks, low power microcontrollers equipped with internal radios are now very accessible.

Figure 1.

A beetle hybrid system (Sato et al., 2009b; Maharbiz and Sato, 2010). (A) Overview of the stimulator-mounted beetle (Mcynorhina torquata, 6 cm, 10 g, 3 g payload capacity). (B) The latest version of beetle stimulator. It has a surface mount ceramic antenna, and its total mass is 1.22 g (a lithium ion rechargeable battery included). (C–E)anatomical pictures of (C,D) muscular stimulation site (right basilar muscle), (E) optic lobe and brain stimulation sites (the fat bodies, tracheae were removed to provide the clear images). The blue bar and letters of X indicate the electrode inserted length and positions, respectively.

Figure 3.

A moth hybrid system. (A) Image of the flexible split-ring electrode (FSE) with color-coded wire connections; (B) close-up image of the FSE at the split-ring region; (C) image of a pupa with inserted FSE; (D) enclosed adult moth with FSE inserted at the pupal stage; (E) image of dissected adult moth showing the growth of connective tissue around the FSE. Reproduced from Tsang et al. (2010a).

Figure 2.

A moth hybrid system. (A) Description of the balloon-assisted flight setup with the ring inserted for recording purposes. (B) Details of the assembled system. (C) 3-D bending of the wire electrodes to target the thorax and antennal lobe. (D)Probe. (E) Front side of the assembled radio board holding the microcontroller and the receiver. (F) Backside of the board with a flat flex cable (FFC) connectors for (G) battery and (D) probe. (E,F) Magnets taped to the circuit to connect with the balloon. Reproduced from Bozkurt et al. (2009b).

Stimulation Protocols

Flight control of insects ideally requires the triggering of flight initiation and cessation as well as the free-flight adjustment of orientation with 3 degrees of freedom (Dudley, 2000; Taylor, 2001). It is important to note that all published attempts at free flight control rely on the insect to “fly itself” while periodically introducing extraneous input to bias the free flight trajectory. A sufficiently sophisticated system is, in effect, wrapping a synthetic control loop around the existing biological one; the idea of interfering with a biological control loop using an extraneous, synthetic loop has a long history. In insects, the motif has been used repeatedly in studies of motor control and biomechanics (Nishikawa et al., 2007).

To date, wireless flight control of insects has relied on either neuromuscular or neuronal stimulation. In either case, the chosen interface and complimentary stimulation protocol (i.e., electrode geometry, electrode implantation method, stimulus conditions) must generate reproducible, quantifiable alterations to insect flight in a way that is robust to the harsh conditions before, during and after free flight. Free-flying insects routinely impact objects (shocks and hard impact are observed not just in flight or during accidents, but very often while landing); the vibrations of the center of mass can be substantial and at frequencies (50–200 Hz) which can resonantly couple to extraneous mechanical components (i.e., 3 cm dipole antennas); and the legs or wings themselves can interfere with operation during normal flight. All of these conditions invariably lead to mechanical drift of the implanted electrodes over the lifetime of the insects. Successful, robust stimulation schemes in free flight have thus focused on combinations of the following three motifs: (a) the direct stimulation of a large, easily accessible muscle in the insect (Bozkurt et al., 2008a, 2009a,b; Sato et al., 2008a,b, 2009a,b; Maharbiz and Sato, 2010), (b) the direct stimulation of a relatively large ensemble of neurons in a ganglion (Sato et al., 2008a,b, 2009a,b; Bozkurt et al., 2009b), (c) the targeted stimulation of nerves in a nerve cord (Tsang et al., 2008, 2010a,b; Daly et al., 2009, 2010).

Flight initiation and cessation

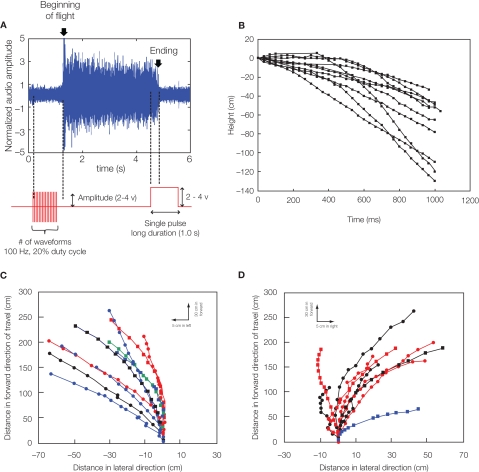

In adult Mecynorhina ugandensis beetles, the abrupt darkening of the environment during untethered free flight led to the almost immediate cessation of flight. This led us to hypothesize that light levels and corresponding changes in neural activity at the optic lobes might strongly modulate flight initiation and cessation. In fact, potential pulses applied between two electrodes implanted near the base of the left and right optic lobes could elicit flight initiation and cessation with very high success rates. Implantation into the optic lobe yielded a much higher success rate and did not affect the beetle's ability to steer in free flight (Movie S1 in Supplementary Material, Figure 4A, Sato et al., 2008b, 2009a,b; Maharbiz and Sato, 2010). Ten insects initiated flight in response to stimulation, with the median number of stimulation waveforms required to initiate flight being 19 (range 1–59). One stimulation waveform was a pair of biphasic square pulses (1 ms per each pulse, 4 ms pitch). The median response time from the first stimulation to flight initiation being 0.5 s (range 0.2–1.4 s). Median flight duration in response to stimulation was 46 s (range 33–2292 s). Stimulation voltage between 2 and 4 V did not affect the number of stimuli required to initiate flight, response time from stimulation to flight, or flight duration in Mecynorhina torquata (Mann–Whitney U-tests, P = 0.13, 0.46, 0.35, respectively). Data on stimulated flight bouts in individual beetles are summarized in Sato et al. (2009b). Once flight was initiated by our stimulation, the flight tended to persist without additional stimulation whether the beetle was either in the tethered or in free flight condition. During normal flight, the beetle nervous system produces a pulse train with approximately 50 ms period to the basalar muscles (Josephson et al., 2000a,b). Artificially induced flight lasted far longer than 50 ms: median flight durations were 2.5 s (range 0.2–1793.1 s) for Cotinis texana, and 45.5 s (range 0.7–2292.1 s) for Mecynorhina torquata. Between given insects, flight bout duration was correlated with neither beetle mass nor stimulus amplitude. Furthermore, the beetle adopted a normal flight posture and continued flying in the air after the stimulus was turned off, indicating that the tonic neural signals required for flight maintenance continued after stimulus.

Figure 4.

Remote radio control of beetle flight by electrical stimulation. (A) Initiation and cessation control. Alternating positive and negative potential pulses at 100 Hz applied between left and right optic lobes initiated wing oscillations while a single pulse ceased wing oscillations; (top) audio recording of tethered beetle, (bottom) applied potential to the one side optic lobe regarding the other side optic lobe. The sharp rise of audio amplitude at the beginning of oscillation is attributed to friction between elytra and wings when the wings came out from the underneath of elytra. The whole audio amplitudes were normalized by mean absolute value calculated for the middle period of the flight time (2.5–3.7 s). (B) Elevation control of a free-flying beetle: temporal height change of a flying beetle (10 flight paths). Alternating positive and negative potential pulse trains at 100 Hz and 2.0 V amplitude to the brain caused the beetle to fly downward. The median height change was 60 cm (the range was 33–129 cm). (C,D) Turn control of free-flying Mecynorhina torquatabeetle. Pulse trains at 100 Hz and 1.3 V positive potential to the left or right basalar muscle triggered turns. Ten flight paths elicited by (A) right or (B) left basalar muscle stimulus for 0.5 s. Each flight path is obtained after the three-dimensional digitized flight path is projected on the XY plane (see Sato et al. 2009b). Different colored and shaped plots show individual beetle flight paths. See Movies S1–S4 in Supplementary Material for the initiation and cessation in free flight (Movie S1), elevation (Movie S2: tethered, Movie S3: free flight) and turn controls (Movie S4). Reproduced from Sato et al. (2009b).

A relatively long duration pulse applied between optic lobes, which effectively clamps the voltage between the lobes, stopped flight for Mecynorhina torquata. Ten insects were tested in tethered condition and each test was repeated for 10 times, i.e., 100 tests in total. Data on cessation of flight in individual insects are summarized in Sato et al. (2009b). All 10 insects tested were forced to stop flying by amplitude of 6.0 V or less. The majority (77%) stopped with a 2–3 V amplitude. The median amplitude was 3.0 V (range 2–6 V). The majority (87%) showed quite short response time <100 ms. In Manduca sexta, Bozkurt et al. (2009b) showed that stimulation of the antennal lobes with 20 Hz, 3.5 Vpeak-to-peak pulses elicited flight while stimulation of the same site with 50 Hz, 3.5 Vpeak-to-peak pulses ceased flight.

Throttling the oscillator

During flight, the frequency and stroke amplitude of wing oscillation could be manipulated with the neural stimulator in beetles (Sato et al., 2008a, 2009b; Maharbiz and Sato, 2010). For C. texana, it was observed that progressively shortening the time between positive and negative potential pulses delivered to the area of the brain between the optic lobes led to the “throttling” of flight where the beetle's normal 76 Hz wing oscillation was strongly modulated by the 0.1–10 Hz applied stimulus (Sato et al., 2008a, 2009b). A repeating program of 3 s, 10 Hz, 3.0 V pulse trains followed by a 3 s pause (no stimulus) resulted in alternating periods of higher and lower pitch flight (Sato et al., 2008a, 2009a). In a similar fashion, Mecynorhina torquata, brain stimulus at 100 Hz led to depression of flight (Figure 4B, tethered flight: Movie S2 in Supplementary Material, free flight: Movie S3 in Supplementary Material). Set on a custom pitching gimbal, Mecynorhina torquata could be repeatedly made to lower angle to horizon when stimulated. The change in the length of envelope of the blurry region around the wing suggests that the wing stroke amplitude was clearly reduced (see the tethered flight: Movie S2 in Supplementary Material). Ten of 11 tested beetles showed the tendency (Sato et al., 2008b, 2009a,b; Maharbiz and Sato, 2010).

Controlled turning

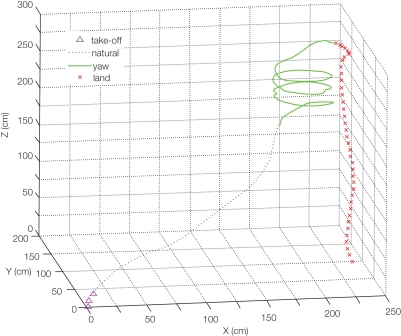

One of the classical methods for studying flight control in tethered animals is through the use of changing visual cues within the insect's field of view. Employing arrays of light emitting diodes (LED's) or digital projection on a screen, visual features such as scrolling stripes, moving shapes, and changing horizons elicit very strong maneuvering responses from many insects (e.g., Bothoz et al., 1992, Tu and Dickinson, 1996, Sato et al., 2008a). Given that most insect compound eyes cannot move to track targets, visual cues which induce locomotion responses often also elicit strong motions of the head. In fact, the contraction of flight muscles is usually preceded by the rotation of the head toward the aimed direction (Berthoz et al., 1992). Exploiting this, Bozkurt et al. (2009b) stimulated neck muscles to induce turning in flying moths. An electrical stimulus delivered to the neck muscles via thin wire electrodes implanted in the Manduca sexta elicited yawing in balloon-assisted flight (Figure 5). In contrast to attempts at direct stimulation of the wing muscles, neck-muscle stimulation avoids damage to the complex linkages and muscles of the wing. For insects whose small size or wing muscle complexity makes direct wing muscle stimulation prohibitive (i.e., bees, flies), this method has decided advantages.

Figure 5.

Digitized flight track of the balloon assisting moth hybrid system as in Figure 2 as a result of applied stimulation pulses. Reproduced from Bozkurt et al. (2009b).

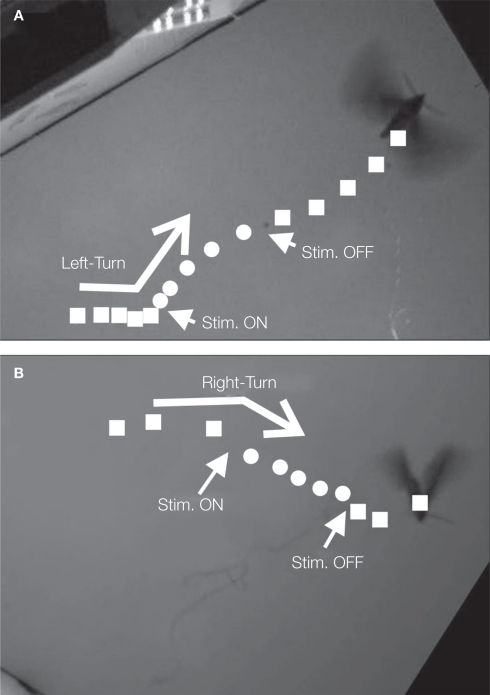

Tsang et al. (2008, 2010a,b) developed a microfabricated polyimide multi-site flexible split-ring electrode (FSE) which could be implanted around the insect's ventral nerve cord just below the fourth abdominal segment during stage-16 of pupation (2 days prior to emergence). This approach was informed by the fact that changes in an insect's center of gravity can be used to adjust flight orientation and trajectory (Ellington, 1984). In moths, stimulation of the ventral cord with tungsten wires elicited abdominal motions, “presumably by activating motoneurons or interganglionic interneurons” (Tsang et al., 2008, 2010a,b). Each FSE contained six independently addressable electrodes; potential pulse trains were applied between pairs of electrodes on the FSE (for a total of 15 possible stimulation pairs). The application of 1–500 ms, 1–5 V potential pulses with frequencies varying between 50 and 333 Hz, elicited directional contraction of the abdomen depending on the electrode pair chosen. Interestingly, the direction of contraction for a given electrode pair not only varied from animal to animal but between the pupal and adult stages of the same animal, implying not only “movement of the FSE but probably also … developmental differences in the location and identity of axons in the nerve cord and changes in the mechanical articulation of the abdomen.” By adjusting voltage levels and frequency, the abdominal response could be graded, an important consideration for future studies of free flight control. Abdominal contractions in loosely tethered moths elicited by the FSE were shown to correspond to changes in flight path (Figure 6, Tsang et al., 2010a).

Figure 6.

Images showing the loosely tethered moth as in Figure 3. (A) left and (B) right turns. Reproduced from Tsang et al. (2010a).

Asymmetric stimulation of the muscles that actuate insect's wings can be used to generate turns. In beetles, for instance, turns could be elicited by stimulus of the left and right basalar muscles with positive potential pulse trains. In C. texana, the basalar muscles normally contract and extend at 76 Hz when they are stimulated by approximately 8 Hz neural impulses from the beetle nervous system (Josephson et al., 2000a,b). It has been reported that the flight muscles in Cotinis produce maximum power when they are stimulated directly by electrical pulses at 100 Hz (Josephson et al., 2000b). During flight of tethered C. texana, a turn could be elicited by applying 2.0 V, 100 Hz positive potential pulse trains to the basalar muscle opposite to the intended turn direction (Sato et al., 2008a,b, 2009a,b; Maharbiz and Sato, 2010). A right turn, for example, was triggered by stimulating the left basalar muscle. In free-flying Mecynorhina torquata, turning was elicited when either of the left or right basalar muscles was stimulated in the same manner as C. texana but 1.3 V (Movie S4 in Supplementary Material, Figures 4C,D, Sato et al., 2009a,b; Maharbiz and Sato, 2010). The success rates for left and right turn were 78% (N = 42) and 66% (N = 68), respectively. One second of left- and right-stimulation of free-flying beetles resulted in a 1.7 and −9.0 median roll to the ground and a 20.0 and 32.4 median rotations parallel to the ground, respectively (see, Sato et al., 2009b for data on stimulus turns in free-flying Mecynorhina torquata).

Ongoing Work and Applications

From an engineering perspective, the latest push toward remotely controlled free-flying insects is providing impetus for several new research directions. Undoubtedly, one of the outstanding issues is determining to what extent sophisticated, synthetic control can bias complex flight in natural environments; this is an old topic in the insect neurophysiology community but one which may deserve re-evaluation given rapid advances in interface technology and the extreme miniaturization of computation. How much control effort (and, thus, energy) must be expended to direct an insect along a given trajectory in environments which present extraneous stimuli? Are there inherent limits? To what extent can these neural and neuromuscular responses and their resultant trajectory changes be reliably graded? Put differently, can a reliable servo description for these interfaces be encoded as a pre-requisite for attempting control via local (on-board) algorithms?

Beyond the issue of control, insects which undergo complete metamorphosis may present a unique system with which to study synthetic-organic interfaces; an idea recently posited in Paul et al. (2006). Several groups have begun to explore the advantages, in mechanical, electrical or surgical contexts, of interfaces implanted in insects during pupation, i.e., prior to emergence as adults (Paul et al., 2006; Bozkurt et al., 2007, 2008a,b, 2009a,b; Tsang et al., 2008, 2010a,b; Sato et al., 2008b; Chung and Erickson, 2009). Given the extensive re-working of the insect physiology during pupation, it is tempting to hypothesize that interfaces inserted during this period could somehow co-opt the developmental processes for an engineering advantage; this has not yet been conclusively shown. The process does provide engineering advantages, however. For example, both the authors and others have found that insertion of foreign objects trans-cutaneously in the pupal stages often results in mechanically robust implants as the shell hardens around the structure post-emergence (Paul et al., 2006; Sato et al., 2008b). Complex surgeries, as for that required in Tsang et al. (2008, 2010a,b), are easier in pupa than adults. Moreover, for insects with large interstitial areas (such as horned beetles), a significant mass of material can be introduced into the pupa which becomes incorporated in the insect (provided neither nerves, gut, nor muscle was severed in the insertion, Bozkurt et al., 2008b).

The ability to control the flight of insects and receive information from on-board sensors would have many applications. In biology, the ability to control insect flight would be useful for studies of insect communication, pollination and mating behavior and flight energetics, and for studying the foraging behavior of insect predators such as birds, as has been done with terrestrial robots (Michelsen et al., 1989). The technology may also enable new types of experiments relevant to neuroscience as it relates to insect flight. Remote stimulation and recording systems, coupled with flight arenas equipped with real-time motion-capture systems, can trigger motor responses decoupled from the insect's sensory inputs while tracking the resultant changes in flight behavior and recovery. This can be done while simultaneously recording neural or neuromuscular signals from the insect. This is an area of interest in our lab, specifically as it informs or improves the ability to elicit controlled reactions from flying insects. Moreover, the ability to take real-time motion data allows for the timing of control signals referenced to a specific state of the insect in flight (e.g., stimulation is applied only at specific orientations, velocities, rotations, etc.) which may help tease out the control circuits at work in the insect. In engineering, electronically controllable insects could be useful models for insect-mimicking M/NAV's (Micro/Nano Air Vehicles) (Wu et al., 2003; Schenato et al., 2004; Deng et al., 2006a,b; Wood, 2008). Furthermore, tetherless, electrically controllable insects themselves could be used as M/NAV's and serve as couriers to locations not easily accessible to humans or terrestrial robots.

In engineering, electronically controllable insects could be useful models for insect-mimicking M/NAV's (Wu et al., 2003; Schenato et al., 2004; Wood, 2008). Furthermore, tetherless, electrically controllable insects themselves could be used as M/NAV's and serve as couriers to locations not easily accessible to humans or terrestrial robots. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, these systems provide a readily accessible platform with which to study the integration between man-made interfaces and multicellular organisms engaged in complex tasks. This endeavor will certainly not replace the pursuit of building synthetic flying robots (since humans often build better machines than nature does), but computation and communication technology scales faster rate than power supply energy density or mechanical actuation. As smaller and lower power microcontrollers and radios continue to appear on the market, researchers will be able to add an increasing amount of synthetic control into organic systems enabling new classes of programmable machines.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

This movie shows a series of initiation and cessation rounds of an unconstrained Mecynorhina torquata beetle equipped with an RF receiver for wireless communication. The initiation stimulus made the beetle take off into the air. The beetle then stopped flying when a single pulse was sent to the region between the optic lobes. A red LED indicator mounted on the RF receiver showed when stimulation was commanded by remote operator. Reproduced from Sato et al. (2009b).

This movie shows elevation control of flying Mecynorrhina torquata on a pitching gimbal. The beetle decreased its climbing rate whenever stimulus pulse trains were applied to the brain (the pulse trains appeared on oscilloscope monitor). It returned to normal flight when un-stimulated (the pulse trains disappeared from the oscilloscope monitor). Reproduced from Sato et al. (2009b).

This movie shows remote elevation control of a free-flying Mecynorhina torquata. An RF receiver for wireless communication was mounted on the beetle. Wireless commands instructed the microcontroller to apply stimuli to the brain (Sato et al., 2009a,b), which caused the beetle to lose altitude. Once the command was removed, the beetle returns to normal flight and regains altitude. A blue LED blinked whenever the microcontroller received a command sent by remote operator. Reproduced from Sato et al. (2009b).

This movie shows remote turn control of free-flying Mecynorhina torquata. An RF receiver for wireless communication was mounted on the beetle. After the RF receiver accepted a command to apply stimulus pulse trains to either left or right basalar muscle, the beetle turned. Red, green and yellow LED indicators were placed on the ground to show when the remote operator commanded the optic lobe (flight initiation), right basalar (left turn) and left basalar (right turn) muscle stimulations, respectively. Reproduced from Sato et al. (2009b).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Jiro Okada (Nagasaki University), Professor Donn T. Johnson (University of Arkansas), Professor Robert J. Full (UC Berkeley), Professor Kazuo Ikeda (City of Hope National Medical Center), Professor Amit Lal (Cornell University), Professor Thomas L. Daniel (University of Washington), Professor Joel Voldman (MIT), John G. Hildebrand (University of Arizona), Alper Bozkurt (North Carolina State University) and Professor Jon Harrison (Arizona State University) for their helpful advices on biology and entomology. The work was financially supported by DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Project Agency) and Electro Mechanic Technology Advancing Foundation, Japan.

Key Concept

- Telemetry

The science and technology of measuring, transmitting, and storing signals of interest remotely. An instrument to measure and transduce the phenomenon of interest into electrical signals is attached on a target and the electrical signals are modulated and transmitted to the users’ receiver, which demodulates the electrical signals.

- Optic lobe

The part of the protocerebrum (one of the three major regions of insect brain) that extends to the retina of the visual receptors including compound eye and ocelli). Neural signals induced at the visual receptors descend to the optic lobe. The optic lobe consists of three large neuropils: lamina, medulla, and lobuli.

- Basalar muscle

One of the flight muscles in insects. In beetles (Coleoptera), the basalar muscle is directly connected to the wing base via the apodema cap. The basalar muscle is a well-developed fibrillar muscle composed of approximately 90 fibers in C. texana (Josephson et al., 2000b). The contraction of the basalar muscle produces the downstroke of wing oscillation. See Figure 1 for the location and structure of the basalar muscle of Coleoptera.

- Gimbal

A structure consisting of a frame which can rotate about a pivot point, constraining the rotation of the frame and anything attached to it to a single axis. Nesting more than one pivoted frame allows for rotation about multiple axes. For the custom gimbal discussed here, the frame was a plastic ring attached to a support ring using elastomeric material (which formed a pivot point). The inner ring had a magnetic attachment point where a flying insect was localized; when the insect was stimulated the amount of rotation about a single axis could be measured (e.g., pitch angle).

- Complete metamorphosis

One of the two major types of metamorphosis (the other is incomplete metamorphosis). Metamorphosis is the biological process that insects undergo in the development from larva (or nymph) to adult (or imago). In metamorphosis, the insect's body structure, habitat, and behavior often distinctly change. Insects which undergo complete metamorphosis pass through three different structural and habitudinal stages including larva, pupa, and adult. Insects which undergo incomplete metamorphosis progressively enlarge via ecdysis (molting or the shedding of the exoskeleton) but keep similar structure and habit from larva to adult.

- Micro/nano air vehicles

A class of small-sized remote-controlled unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV). In a restricted definition, micro air vehicles (MAV) and nano air vehicles (NAV) are less than 150 and 75 mm in maximum length, respectively. In many cases, the design, mechanics and aerodynamics of M/NAV's has been inspired by bird and insect flight (Wu et al., 2003; Deng et al., 2006a,b; Wood, 2008; de Croon et al., 2009).

Biographies

Hirotaka Sato received his B.Sc. and Ph.D. in Chemistry from Waseda

University, Japan for his work on electrochemistry based nano-fabrication processes

under Professor Takayuki Homma (Chem), Professor Shuichi Shoji (EECS) and Professor

Tetsuya Osaka (Chem). He started his postdoc work in 2007 at University of Michigan

and in 2008 at University of California at Berkeley where he has been leading a

research project demonstrating the remote radio control of insect flight (often

referred to as “Cyborg Insects”). In 2009, his research was ranked

in TR10 (MIT Tech Review) and selected as one of the top 50 innovations by TIME

magazine. His research interests are in biochemistry, neuromuscular physiology,

electrochemistry and MEMS (Micro Electro Mechanical Systems).

Hirotaka Sato received his B.Sc. and Ph.D. in Chemistry from Waseda

University, Japan for his work on electrochemistry based nano-fabrication processes

under Professor Takayuki Homma (Chem), Professor Shuichi Shoji (EECS) and Professor

Tetsuya Osaka (Chem). He started his postdoc work in 2007 at University of Michigan

and in 2008 at University of California at Berkeley where he has been leading a

research project demonstrating the remote radio control of insect flight (often

referred to as “Cyborg Insects”). In 2009, his research was ranked

in TR10 (MIT Tech Review) and selected as one of the top 50 innovations by TIME

magazine. His research interests are in biochemistry, neuromuscular physiology,

electrochemistry and MEMS (Micro Electro Mechanical Systems).

Michel M. Maharbiz is an Associate Professor with the Department of

Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the University of California,

Berkeley. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley for

his work on microbioreactor systems under Professor Roger T. Howe (EECS) and

Professor Jay D. Keasling (ChemE). Professor Maharbiz's current research

interests include building micro/nano interfaces to cells and organisms and

exploring bio-derived fabrication methods. Michel's long term goal is

understanding developmental mechanisms as a way to engineer and fabricate

machines.

Michel M. Maharbiz is an Associate Professor with the Department of

Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the University of California,

Berkeley. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley for

his work on microbioreactor systems under Professor Roger T. Howe (EECS) and

Professor Jay D. Keasling (ChemE). Professor Maharbiz's current research

interests include building micro/nano interfaces to cells and organisms and

exploring bio-derived fabrication methods. Michel's long term goal is

understanding developmental mechanisms as a way to engineer and fabricate

machines.

References

- Altendorfer R., Moore N., Komsuolu H., Buehler M., Brown H. B., McMordie D., Saranli U., Full R., Koditschek D. E. (2001). RHex: a biologically inspired hexapod runner. Auton. Robots 11, 207–213 10.1023/A:1012426720699 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ando N., Kanzaki R. (2004). Changing motor patterns of the 3rd axillary muscle activities associated with longitudinal control in freely flying hawkmoths. Zool. Sci. 21, 123–130 10.2108/zsj.21.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando N., Shimoyama I., Kanzaki R. (2002). A dual-channel FM transmitter for acquisition of flight muscle activities from the freely flying hawkmoth, Agrius convolvuli. J. Neurosci. Methods 115, 181–187 10.1016/S0165-0270(02)00013-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz A., Vidal P. P., Graf W. (1992). The Head Neck Sensory Motor System. New York: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt A., Gilmour R., Stern D., Lal A. (2008a). “MEMS based bioelectronic neuromuscular interfaces for insect cyborg flight control,” in Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS 2008), Tucson, AZ, 160–163 [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt A., Lal A., Gilmour R. (2008b). “Electrical endogenous heating of insect muscles for flight control,” in 30th International Conference IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC’08), Vancouver, 5786–5789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt A., Gilmour R., Sinha A., Stern D., Lal A. (2009a). Insect-machine interface based neurocybernetics. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 56, 1727–1733 10.1109/TBME.2009.2015460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt A., Gilmour R., Lal A. (2009b). Balloon-assisted flight of radio-controlled insect biobots. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 56, 2304–2307 10.1109/TBME.2009.2022551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt A., Paul A., Pulla S., Ramkumar R., Blossey B., Ewer J., Gilmour R., Lal A. (2007). “Microprobe microsystem platform inserted during early metamorphosis to actuate insect flight muscle,” in Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS 2007), Kobe, 405–408 10.1109/MEMSYS.2007.4432976 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks R. A. (1991). New approaches to robotics. Science 253, 1227–1232 10.1126/science.253.5025.1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung A. J., Erickson D. (2009). Engineering insect flight metabolics using immature stage implanted microfluidics. Lab. Chip 9, 669. 10.1039/b814911a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colot A., Caprari G., Siegwart R. (2004). “InsBot: design of an autonomous mini mobile robot able to interact with cockroaches,” in IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Vol. 3, New Orleans, LA, 2418–2423 [Google Scholar]

- Cooke S. J., Hinch S. G., Wikelski M., Andrews R. D., Kuchel L. J., Wolcott T. G., Butler P. J. (2004). Biotelemetry: a mechanistic approach to ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 334–343 10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly D. C., Mercier P. P., Bhardwaj M., Stone A. L., Voldman J., Levine R. B., Hildebrand J., Levine R. B., Hildebrand J. G., Chandrakasan A. P. (2009). “A pulsed UWB receiver SoC for insect motion control,” in Solid-State Circuits Conference – Digest of Technical Papers, 2009. ISSCC 2009, San Francisco, CA, 200–201 [Google Scholar]

- Daly D. C., Mercier P. P., Bhardwaj M., Stone A. L., Voldman J., Levine R. B., Hildebrand J., Levine R. B., Hildebrand J. G., Chandrakasan A. P. (2010). A pulsed UWB receiver SoC for insect motion control. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 45, 153–166 10.1109/JSSC.2009.2034433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Croon G. C. H. E., de Clerq K. M. E., Ruijsink R., Remes B., de Wagter C. (2009). Design, aerodynamics, and vision-based control of the delfly. Int. J. Micro Air Vehicle 1, 71–97 10.1260/175682909789498288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delcomyn F. (2004). Insect walking and robotics. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 49, 51–70 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X., Schenato L., Sastry S. (2006a). Flapping flight for biomimetic robotic insects: part II-flight control design. IEEE Trans. Rob. 22, 789–803 10.1109/TRO.2006.875483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X., Schenato L., Wu W. C., Sastry S. (2006b). Flapping flight for biomimetic robotic insects: part I-system modeling. IEEE Trans. Rob. 22, 776–788 10.1109/TRO.2006.875480 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson M. H., Farley C. T., Full R. J., Koehl M. A. R., Kram R., Lehman S. (2000). How animals move: an integrative view. Science 288, 100–106 10.1126/science.288.5463.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson M. H., Lehmann F., Sane S. P. (1999). Wing rotation and the aerodynamic basis of insect flight. Science 284, 1954–1960 10.1126/science.284.5422.1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson M. H., Tu M. (1997). The function of dipteran flight muscle. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 116, 223–238 [Google Scholar]

- Dudley R. (2000). The Biomechanics of Insect Flight: Form, Function, Evolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- Ellington C. P. (1984). The aerodynamics of hovering insect flight. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B. Biol. Sci. 305, 79–113 10.1098/rstb.1984.0052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington C. P., Van Den Berg C., Willmott A. P., Thomas A. L. R. (1996). Leading-edge vortices in insect flight. Nature 384, 626–630 10.1038/384626a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H., Ebert E. (1999). Tegula function during free locust flight in relation to motor pattern, flight speed and aerodynamic output. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 711–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H., Kautz H., Kutsch W. (1996). A radiotelemetric 2-channel unit for transmission of muscle potentials during free flight of the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria. J. Neurosci. Methods 64, 39–45 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00083-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H., Kutsch W. (1999). Timing of elevator muscle activity during climbing in free locust flight. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 3575–3586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Full R., Koditschek D. (1999). Templates and anchors: neuromechanical hypotheses of legged locomotion on land. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 3325–3332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedin J., Ranius T. (2002). Using radio telemetry to study dispersal of the beetle Osmoderma eremita, an inhabitant of tree hollows. Comput. Electron. Agric. 35, 171–180 10.1016/S0168-1699(02)00017-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland R. A. (2006). How and why do insects migrate? Science 313, 794–796 10.1126/science.1127272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer R., Shimoyama I. (1997). “Locomotion control of a bio-robotic system via electric stimulation,” in Proceedings of the 1997 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robot and Systems Innovative Robotics for Real-World Applications IROS ’97, Vol. 3, Grenoble, 1514–1519 [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K., Boettiger E. G. (1965). Studies on the flight mechanism of insects Studies on the flight mechanism of insects -III. The innervation and electrical activity of the basalar fibrillar flight muscle of the beetle, Oryctes rhinoceros. J. Insect Physiol. 11, 791–802 10.1016/0022-1910(65)90158-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson R. K., Malamud J. G., Stokes D. R. (2000a). Asynchronous muscle: a primer. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 2713–2722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson R. K., Malamud J. G., Stokes D. R. (2000b). Power output by an asynchronous flight muscle from a beetle. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 2667–2689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsch W. (2002). Transmission of muscle potentials during free flight of locusts. Comput. Electron Agric. 35, 181–199 10.1016/S0168-1699(02)00018-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsch W., Schwarz G., Fischer H., Kautz H. (1993). Wireless transmission of muscle potentials during free flight of a locust. J. Exp. Biol. 185, 367–373 [Google Scholar]

- Kutsch W., Berger S., Kautz H. (2003). Turning manoeuvres in free-flying locusts: two-channel radio-telemetric transmission of muscle activity. J. Exp. Zool. Part A Comp. Exp. Biol. 299, 139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana Y., Ando N., Kanzaki R., Shimoyama I. (1999). “A radiotelemetry system for muscle potential recordings from freely flying insects,” in Proceedings of the First Joint Engineering in Medicine and Biology, 1999. 21st Annual Conference and the 1999 Annual Fall Meeting of the Biomedical Engineering Society Conference, Vol. 2, Atlanta, GA, 846 [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana Y., Shimoyama I., Miura H. (1995). “Steering control of a mobile robot using insect antennae,” in Proceedings of IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 530–535 [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann F. (2004). Aerial locomotion in flies and robots: kinematic control and aerodynamics of oscillating wings. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 33, 331–345 10.1016/j.asd.2004.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmerhirt D., Staudacher E., Wise K. (2006). A multitransducer microsystem for insect monitoring and control. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 53, 2084–2091 10.1109/TBME.2006.877115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leston D., Pringle J., White D. (1965). Muscular activity during preparation for flight in a beetle. J. Exp. Biol. 42, 409–414 [Google Scholar]

- Machin K., Pringle J. (1959). The physiology of insect fibrillar muscle II: mechanical properties of a beetle flight muscle. Proc. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., Ser. B 151, 204–225 10.1098/rspb.1959.0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin K., Pringle J. (1960). The physiology of insect fibrillar muscle III: the effect of sinusoidal changes of length on a beetle flight muscle. Proc. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., Ser. B 152, 311–330 10.1098/rspb.1960.0041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin K., Pringle J., Tamasige M. (1962). Physiology of insect fibrillar muscle IV: effect of temperature on a beetle flight muscle. Proc. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., Ser. B 155, 493–499 10.1098/rspb.1962.0014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maharbiz M. M., Sato H. (2010). Cyborg beetles: tiny flying robots that are part machine and part insect may one day save lives in wars and disasters. Sci. Am. 303, 94–99 10.1038/scientificamerican1210-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen A., Andersen B. B., Kirchner W. H., Lindauer M. (1989). Honey bees can be recruited by a mechanical model of a dancing bee. Naturwissenschaften 76, 277–280 10.1007/BF00368642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni P., Nagarajan K., Ziaie B., Najafi K., Crary S. (2001). An ultralight biotelemetry backpack for recording EMG signals in moths. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 48, 734–737 10.1109/10.923792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni P., Najafi K., Eliades S., Wang X. (2005). Wireless multichannel biopotential recording using an integrated FM telemetry circuit. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 13, 263–271 10.1109/TNSRE.2005.853625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K., Biewener A. A., Aerts P., Ahn A. N., Chiel H. J., Daley M. A., Daniel T. L., Full R. J., Hale M. E., Hedrick T. L., Lappin A. K., Nichols T. R., Quinn R. D., Satterlie R. A., Szymik B. (2007). Neuromechanics: an integrative approach for understanding motor control. Integr. Comp. Biol. 47, 16–54 10.1093/icb/icm024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquet R. S., Peltier A., Hufford M. B., Oudin E., Saulnier J., Paul L., Knudsen J. T., Herren H. R., Gepts P. (2008). Long-distance pollen flow assessment through evaluation of pollinator foraging range suggests transgene escape distances. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13456–13461 10.1073/pnas.0806040105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A., Bozkurt A., Ewer J., Blossey B., Lal A. (2006). “Surgically implanted micro-platforms in manduca-sexta,” in Solid State Sensor Actuator Workshop, Hilton Head Island, 209–211 [Google Scholar]

- Pringle J. W. S. (1957). Insect Flight. New York: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Ritzmann R. E., Quinn R. D., Fischer M. S. (2004). Convergent evolution and locomotion through complex terrain by insects, vertebrates and robots. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 33, 361–379 10.1016/j.asd.2004.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H., Berry C.W., Casey B. E., Lavella G., Yao Y., VandenBrooks J. M., Maharbiz M. M. (2008a). “A cyborg beetle: insect flight control through an implantable, tetherless microsystem,” in Proceedings on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS 2008), Tucson, AZ, 164–167 [Google Scholar]

- Sato H., Berry C. W., Maharbiz M. M. (2008b). “Flight control of 10 gram insects by implanted neural stimulators,” in Solid State Sensor Actuator Workshop, Hilton Head Island, 90–91 [Google Scholar]

- Sato H., Peeri Y., Baghoomian E., Berry C. W., Maharbiz M. M. (2009a). “Radio-controlled cyborg beetles: a radio-frequency system for insect neural flight control,” in Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical System (MEMS 2009), Sorrento, 216–219 10.1109/MEMSYS.2009.4805357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H., Berry C. W., Peeri Y., Baghoomian E., Casey B. E., Lavella G., VandenBrooks J. M., Harrison J. F., Maharbiz M. M. (2009b). Remote radio control of insect flight. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 3 24. 10.3389/neuro.07.024.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenato L., Wu W. C., Sastry S. (2004). Attitude control for a micromechanical flying insect via sensor output feedback. IEEE Trans. Rob. Autom. 20, 93–106 10.1109/TRA.2003.820863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sword G. A., Lorch P. D., Gwynne D. T. (2005). Insect behavior: migratory bands give crickets protection. Nature 433, 703–703 10.1038/433703a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi S., Shimoyama I. (2004). A radio-telemetry system with a shape memory alloy microelectrode for neural recording of freely moving insects. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 51, 133–137 10.1109/TBME.2003.820310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H., Wood R. J. (2010). Fabrication of corrugated artificial insect wings using laser micromachined molds. J. Micromech. Microeng. 20, 075008. 10.1088/0960-1317/20/7/075008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G. K. (2001). Mechanics and aerodynamics of insect flight control. Biol. Rev. 76, 449–471 10.1017/S1464793101005759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipton V. J. (1976). Insects: a success story. Am. Biol. Teach. 38, 205–207 [Google Scholar]

- Tsang W. M., Aldworth Z., Stone A., Permar A., Levine R., Hildebrand J. G., Daniel T., Akinwande A. I., Voldman J. (2008). Insect flight control by neural stimulation of pupae-implanted flexible multisite electrodes. Proc. Micro Total Anal. Syst. 1922–1924 [Google Scholar]

- Tsang W M., Stone A. L., Aldworth Z. N., Hildebrand J. G., Daniel T. L., Akinwande A. I., Voldman J. (2010a). Flexible split-ring electrode for insect flight biasing using multisite neural stimulation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57, 1757–1764 10.1109/TBME.2010.2041778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang W. M., Stone A. L., Aldworth Z. N., Otten D., Akinwande A. I., Daniel T. L., Hildebrand J. G., Levine R., Voldman J. (2010b). “Remote control of a cyborg moth using carbon nanotube-enhanced flexible neuroprosthetic probe,” in Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical System (MEMS 2010), Hong Kong, 39–42 10.1109/MEMSYS.2010.5442570 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tu M., Dickinson M. (1994). Modulation of negative work output from a steering muscle of the blowfly Calliphora vicina. J. Exp. Biol. 192, 207–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu M., Dickinson M. (1996). The control of wing kinematics by two steering muscles of the blowfly (Calliphora vicina). J. Comp. Physiol. A 178, 813–830 10.1007/BF00225830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Ando N., Kanzaki R. (2008). Active control of free flight manoeuvres in a hawkmoth, Agrius convolvuli. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 423–432 10.1242/jeb.011791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikelski M., Moskowitz D., Adelman J. S., Cochran J., Wilcove D. S., May M. L. (2006). Simple rules guide dragonfly migration. Biol. Lett. 2, 325–329 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikelski M., Moxley J., Eaton-Mordas A., López-Uribe M. M., Holland R., Moskowitz D., Roubik D. W., Kays R. (2010). Large-range movements of neotropical orchid bees observed via radio telemetry. PLoS ONE 5, e10738. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood R. J. (2008). The first takeoff of a biologically inspired at-scale robotic insect. IEEE Trans. Rob. 24, 341–347 10.1109/TRO.2008.916997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W. C., Schenato L., Wood R. J., Fearing R. S. (2003). Biomimetic sensor suite for flight control of a micromechanical flying insect: design and experimental results. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Rob. Autom. 1, 1146–1151 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This movie shows a series of initiation and cessation rounds of an unconstrained Mecynorhina torquata beetle equipped with an RF receiver for wireless communication. The initiation stimulus made the beetle take off into the air. The beetle then stopped flying when a single pulse was sent to the region between the optic lobes. A red LED indicator mounted on the RF receiver showed when stimulation was commanded by remote operator. Reproduced from Sato et al. (2009b).

This movie shows elevation control of flying Mecynorrhina torquata on a pitching gimbal. The beetle decreased its climbing rate whenever stimulus pulse trains were applied to the brain (the pulse trains appeared on oscilloscope monitor). It returned to normal flight when un-stimulated (the pulse trains disappeared from the oscilloscope monitor). Reproduced from Sato et al. (2009b).

This movie shows remote elevation control of a free-flying Mecynorhina torquata. An RF receiver for wireless communication was mounted on the beetle. Wireless commands instructed the microcontroller to apply stimuli to the brain (Sato et al., 2009a,b), which caused the beetle to lose altitude. Once the command was removed, the beetle returns to normal flight and regains altitude. A blue LED blinked whenever the microcontroller received a command sent by remote operator. Reproduced from Sato et al. (2009b).

This movie shows remote turn control of free-flying Mecynorhina torquata. An RF receiver for wireless communication was mounted on the beetle. After the RF receiver accepted a command to apply stimulus pulse trains to either left or right basalar muscle, the beetle turned. Red, green and yellow LED indicators were placed on the ground to show when the remote operator commanded the optic lobe (flight initiation), right basalar (left turn) and left basalar (right turn) muscle stimulations, respectively. Reproduced from Sato et al. (2009b).