Abstract

The goal of this study was to examine the mechanisms underlying associations between neighborhood socioeconomic advantage and children’s achievement trajectories between 54 months and 15 years old. Results of hierarchical linear growth models based on a diverse sample of 1,364 children indicate that neighborhood socioeconomic advantage was non-linearly associated with youths’ initial vocabulary and reading scores, such that the presence of educated, affluent professionals in the neighborhood had a favorable association with children’s achievement among those in less advantaged neighborhoods until it leveled off at moderate levels of advantage. A similar tendency was observed for math achievement. The quality of the home and child care environments as well as school advantage partially explained these associations. The findings suggest that multiple environments need to be considered simultaneously for understanding neighborhood-achievement links.

Keywords: neighborhood, achievement, home environment, child care, school, cognitive stimulation

Living in an advantaged neighborhood where a sizeable proportion of residents are affluent, educated professionals is associated with children’s and adolescents’ achievement, over and above other markers of family advantage (for a review, see Leventhal, Dupéré, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). This association has been substantiated in studies looking at a range of periods and outcomes. From early childhood to adolescence, it has been observed in studies looking at tests scores and, in later adolescence, at years of schooling, high school graduation and college attendance (e.g., Ainsworth, 2002; Boyle, Georgiades, Racine, & Mustard, 2007; Leventhal, Xue, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006). Generally, these studies find that neighborhood advantage is associated with children and youth’s schooling outcomes more strongly and consistently than neighborhood poverty or disadvantage.

Although neighborhood advantage-achievement links are well documented, much less is known about how neighborhood conditions may enhance children’s achievement, in effect limiting the translation of this knowledge into practical recommendations. The goal of this study is to examine how these neighborhood effects are channeled through a series of related contexts that are embedded in, and often bounded by, the neighborhood environment. Specifically, we used longitudinal data on a diverse sample of youth followed from birth through adolescence to explore the mediating role of three key contexts in children’s achievement growth: the home, child care, and school environments. Before reviewing the relevant theoretical frameworks, the next section discusses the nature and shape of the neighborhood-achievement link.

Neighborhood and Achievement: The Nature and Shape of the Link

Observational studies linking neighborhood advantage and children’s achievement need to be viewed with caution. A number of family characteristics beyond family income may drive both neighborhood choice and children’s achievement, such as parental motivation and attitudes. In effect, neighborhood-achievement links may not exist aside from these underlying (or omitted) associations. More stringent designs have been used in neighborhood research in an attempt to address this selection bias, such as sibling fixed-effect models which hold family characteristics constant (Aaronson, 1998; Plotnick & Hoffman, 1999; Vartanian & Buck, 2005); instrumental variable analysis which minimize unmeasured correlations between neighborhood characteristics and child outcomes (Foster & McLanahan, 1996); behavior genetic models which differentiate between genetic and environmental influences (Caspi, Taylor, Moffitt, & Plomin, 2000; Cleveland, 2003), and propensity scoring methods, which match children who do and do not live in certain types of neighborhoods (Harding, 2003; Sampson, Sharkey, & Raudenbush, 2008). Generally, these studies using more rigorous analytic approaches find significant associations between neighborhood characteristics and children’s and adolescents’ outcomes.

Despite the strengths of these designs, experimental studies remain the method of choice for tackling selection issues. Neighborhood studies with experimental or quasi-experimental designs have yielded mixed findings. In most of these studies, low-income, predominately minority families living in public housing in high-poverty neighborhoods were offered vouchers to move to more advantaged neighborhoods. In one Chicago quasi-experimental study, the Gautreaux program, where neighborhood assignment was based on housing availability, youth who moved to middle-class, predominately European American suburbs were more likely to graduate from high school and attend college at a 10-year follow-up than their peers who remained in the city in mostly poor neighborhoods (Rubinowitz & Rosenbaum, 2000). However, conflicting results emerged from the 5-site Moving to Opportunity program (MTO), a true experimental study with randomized neighborhood assignment. A 5-year evaluation of MTO found beneficial outcomes of moving to low-poverty neighborhoods (vs. staying in high-poverty) only on adolescent girls’ education as assessed by a combination of high school completion/enrollment and achievement test scores (Kling, Liebman, & Katz, 2007); however, several other MTO evaluations reported no such favorable effects on achievement-related outcomes (Leventhal, Fauth, & Brooks-Gunn, 2005; Orr, Feins, Jacob et al., 2003; Sanbonmatsu, Kling, Duncan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006). These mixed results could be related to the observation that early neighborhood characteristics may have enduring associations with children’s achievement, despite later neighborhood change (Sampson, Sharkey, & Raudenbush, 2008).

In addition to asking whether there is a link between neighborhood advantage and educational outcomes, researchers have also speculated about the shape of this link. A small body of research suggests that the association may be curvilinear, with maximum beneficial effects seen as soon as a significant proportion of residents are affluent professionals and a diminishing rate of return beyond that point. Just as increases in family income are more beneficial for poor than non-poor children (Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2001), increases in neighborhood advantage may support achievement only up to a certain level. Thus, the benefits of leaving a disadvantaged neighborhood for a middle-class one, as documented in the experimental literature, might not generalize to those leaving middle-class neighborhoods for more affluent ones. Along these lines, one study found that differences in youth’s educational outcomes were particularly marked at the lower end of the neighborhood affluence continuum, between those living in neighborhoods with very few residents holding professional or managerial jobs and youth living in middle-class neighborhoods (Crane, 1991, see also Carpiano, Lloyd & Hertzman, 2009). Middle-class neighborhoods may be especially supportive since they offer advantages from both the presence of more affluent residents and from programs serving lower-income residents (see Carpiano, Lloyd, & Hertzman, 2009). At the right end of the continuum, the culture of very affluent communities might pose challenges for youths (Luthar, 2003).

Although the question of selection remains unresolved, this past research suggests that neighborhood characteristics may influence achievement in a non-linear fashion, with the strongest associations at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum. In this study, we investigate such neighborhood effects and take this work a step further by exploring underlying mechanisms of the effects we observe.

Neighborhood and Achievement: Potential Pathways

In his ecological model of human development, Bronfenbrenner (1979) proposed that development is shaped by a complex web of embedded social contexts. He argued that larger social structures influence development through more proximal contexts directly involving children. For instance, larger socioeconomic structures and cultures may influence parenting norms and parental access to educational resources and, in turn, influence children’s outcomes. Following a similar logic, theories of neighborhood effects on development propose that neighborhood influences likely operate indirectly through various proximal social contexts, such as families, peers, child care, and schools (e.g., Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). Specifically, it is thought that neighborhood advantage enhances achievement by increasing the quality of learning experiences within the family and within neighborhood institutions serving children, most notably child care and school settings. In the next sections, we expand on these conceptual models by elaborating on the ways in which neighborhood affluence might affect familial and institutional practices relevant to achievement.

Neighborhood Advantage, Home Stimulation, and Children’s Achievement

A first theoretical model linking neighborhood advantage and achievement focuses on parenting and the quality of the home environment (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). According to this perspective, collective norms and socialization, as well as the relative level of stress and support in the neighborhood, are primary ways in which neighborhood characteristics may influence parenting and, in turn, achievement. Parenting practices vary from community to community (Furstenberg, Cook, Eccles, Elder, & Sameroff, 1999; Lareau, 2002, 2003). For instance, in high-resources communities, parents tend to actively cultivate learning by creating a myriad of learning opportunities for their children, both inside and outside of the home. Lower middle or working class parents living in less advantaged communities, on the other hand, tend to adopt a less managerial style toward child rearing, capitalizing instead on natural processes of growth (for a description of contrasting norms in affluent and disadvantaged communities, see Luthar, 2003; Wilson, 1987). A concentration of families utilizing certain types of practices may create strong collective norms and consolidate pre-existing socioeconomic differences in parenting. Evidence suggests that shared norms regarding acceptable behaviors are especially cohesive in advantaged neighborhoods (Harding, 2007; Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). On the other hand, social norms are more heterogeneous and cohesion is typically lower in less advantaged neighborhoods, potentially weakening social pressures encouraging more mainstream practices (Simons, Simons, Burt, Brody, & Cutrona, 2005). Weak norms and lack of cohesion could diminish social sanctions against the use of unresponsive or harsh parenting practices (e.g., see Molnar, Buka, Brennan, Holton, & Earls, 2003; Simons, Simons, Burt et al., 2005). Relatedly, in neighborhoods marked by danger and low levels of cohesion, parents may resort to restrictive strategies as a response to perceived threats (Furstenberg, Cook, Eccles et al., 1999).

The level of environmental strains and supports also tends to vary by neighborhood socioeconomic status. Less advantaged neighborhoods often expose residents to stressors in the form of noise, pollution, crime and disorder that appear to damage adults’ mental and physical health (e.g., Hill, Ross, & Angel, 2005). In contrast, living in a resource-rich, well-kept, stable and safe neighborhood may enhance parental well being, and, in turn, parents’ ability to provide and direct learning activities in the home (see Kohen, Leventhal, Dahinten, & McIntosh, 2008). Supporting this view, results from the MTO experiment showed that moving to a more advantaged neighborhood benefited parents’ mental health (Orr, Feins, Jacob et al., 2003). Also, resource-rich neighborhoods support parents in their effort to foster positive development by providing infrastructures and activities. For instance, parents in higher-SES neighborhoods have access to children’s literature in greater quantity and quality in local stores and libraries, as compared with those in less advantaged neighborhoods (Neuman & Celano, 2001).

Studies directly investigating quality of the home environment as a transmission mechanism between neighborhood affluence and achievement are few and far between. A first empirical test conducted in two independent samples of three- to six year-olds found that the positive association between neighborhood advantage and children’s cognitive test scores was partly attributable to the quality of the home environment (Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, Chase-Lansdale, & Gordon, 1997; Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, McCarton, & McCormick, 1998). Other studies looking at preschoolers and first graders obtained similar results (Greenberg, Lengua, Coie et al., 1999; Kohen, Leventhal, Dahinten et al., 2008). Among adolescents, non-experimental (Ainsworth, 2002) and experimental (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2004) evidence reveals that time spent on homework, a routine activity conditioned by the structure of the home environment, partially explained the association between higher-SES neighborhoods and youths’ tests scores. In contrast, other studies find no indication that home stimulation explains the neighborhood advantage-achievement link (Caughy & O’Campo, 2006; Eamon, 2005; McCulloch, 2006). These inconsistencies, along with findings showing only partial mediation, suggest that home stimulation is not the only mechanism at play.

Neighborhood Advantage, Child Care and School Quality, and Children’s Achievement

A second general theoretical model proposes that community socioeconomic characteristics shape the composition and quality of local institutions whose mission revolves around children’s cognitive growth, such as child care and school, and that this, in turn, influences achievement (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). Elaborating on this perspective, we propose that neighborhood financial, human and social capital all influence the strength and vitality of neighborhood learning institutions.

At the most basic level, institutional composition generally reflects the larger community make-up. As such, child care and school settings in more advantaged communities should be comprised of students from more affluent families than institutions in more disadvantaged neighborhoods. A sizeable body of research indicates that school compositional advantage is favorably associated with student achievement (for recent examples, see Konstantopoulos, 2006; Levine & Painter, 2008). These benefits likely arise because greater concentrations of high achieving students may facilitate instruction and learning and create a context with norms supportive of achievement (e.g., Aikens & Barbarin, 2008). Although less often investigated, similar compositional effects may emerge in child care settings as well, a factor that may help explain why lower-SES children tend to receive lower quality care (e.g., NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1997).

In addition to shaping local institutions’ composition, community characteristics likely influence their access to financial and human resources. Neighborhood public services are in large part funded by local tax revenues based on property values and business activities, both of which increase with neighborhood SES. Private services, notably child care, are also likely to reflect parents’ collective willingness and capacity to pay for high-quality services. Financial capital generates better infrastructure, but perhaps more importantly, it often translate into human capital, probably because it allows for better salaries and working conditions. In fact, schools in wealthy suburbs are better at hiring and retaining highly qualified, effective teachers compared with urban schools with large enrollments of poor minority students (Guarino, Santibañez, & Daley, 2006). In the same manner, high-quality care is more accessible in advantaged than disadvantaged neighborhoods (Burchinal, Nelson, Carlson, & Brooks-Gunn, 2008; Fuller, Kagan, Caspary, & Gauthier, 2002). This situation may limit access to high-quality care among children in less affluent communities. Lack of high quality care in the proximal environment may be especially problematic for children of low-income mothers, since practical constraints, primarily regarding location, are likely to take precedence over quality concerns when these mothers select child care arrangements (Peytona, Jacobsa, O’Brien, & Roy, 2001).

Social dynamics in higher-SES neighborhoods, including parental advocacy and social capital, might also strengthen institutions serving children. Compared with lower income parents, advantaged parents tend to expect higher quality services for their children, notably when it comes to instruction (Lareau, 2000, 2002). They also tend to scrutinize service providers more closely and to exert pressures if dissatisfied. Child care and school administrators may respond to these demands more keenly in middle or upper income communities (vs. lower income neighborhoods), where parents typically have more leverage. For instance, in advantaged communities, parents can tap into wide social capital resources, because of high levels of participation in preschool- and school-related activities (Ream & Palardy, 2008; Waanders, Mendez, & Downer, 2007). Such networking also has the advantage of facilitating the flow of information regarding educational opportunities, for instance about where to find stimulating child care providers or outstanding teachers (see Sampson, Morenoff, & Earls, 1999). In addition to helping parents secure high quality services for their children, such informal exchange of information and its impact on parental choice is likely to generate reinforcement contingencies favoring the growth and preservation of well-functioning services in affluent communities. These social resources will likely benefit not only children of actively involved parents but the community as a whole.

A handful of studies focusing on achievement have examined neighborhood conditions in conjunction with child care or school characteristics; they provide suggestive evidence of mediated neighborhood effects. Studies conducted among both children and adolescents find that child care or school experiences (e.g., teacher-reported classroom activities) are correlated with neighborhood characteristics and independently associated with children’s achievement (Aikens & Barbarin, 2008; Cook, Herman, Phillips, & Settersen, 2002; Eamon, 2005), two necessary but insufficient conditions for identifying mediated effects. One study formally testing mediation revealed that school climate, as reported by school administrators, did not mediate the association between neighborhood advantage and tenth graders’ math and reading achievement (Ainsworth, 2002). Studies not directly looking at neighborhoods nonetheless provide some support for the institutional perspective. One study evaluating the effectiveness of a high-quality school operating in a disadvantaged New York neighborhood and exploiting the fact that available slots were allocated at random found that when children received services on par with those usually available in more advantaged neighborhoods, important gains in achievement ensued (Dobbie & Fryer, 2009). A second study based on a natural experiment in which a sudden influx of Ethiopian immigrants were assigned quasi-randomly to Israeli communities with schools of varying quality found that school quality was associated with youths’ lower dropout rates and higher passing rates on matriculation exams (Gould, Lavy, & Paserman, 2004). As a whole, these studies support the institutional resources model, but studies explicitly focusing on neighborhoods and directly testing mediation using direct observations of children’s experiences in both child care and schools are needed.

The Current Study

Research directly investigating pathways of influence is needed to supplement the nascent literature focused on explaining the link between neighborhood advantage and achievement. Such research should attempt to reduce potential selection bias at least by including controls beyond family income and structure, and should consider potential non-linear effects. But especially needed is research looking simultaneously at both the home environment and institutional resources. These two pathways can be construed as either competing or complementary, but the existing literature generally does not adjudicate between them. Considering the two pathways in conjunction is important for understanding how the neighborhood context may shape a series of related environments that play a key role in children’s achievement.

This study provides a comparatively comprehensive assessment of the mechanisms underlying neighborhood advantage effects on children’s vocabulary, reading and math achievement trajectories from early childhood (4.5 years old) to adolescence (15 years old). We expect that children living in higher-SES neighborhoods will have higher achievement than their peers in less advantaged neighborhoods, but that this relationship might stabilize at high levels of neighborhood advantage. We expect that this link will be detectable even after controlling for a number of potential confounders, including basic demographic controls such as child gender, child race/ethnicity, family structure, family income and maternal education, as well as controls tapping into non-material resources, such as mothers’ vocabulary, personality and attitudes towards child-rearing. Finally, we expect that the home (quality and maternal mental health), child care (quality), and school (composition and quality) environments will each play a role in explaining the association between neighborhood advantage and children’s achievement trajectories.

Method

Sample

This study is based on data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (NICHD SECCYD, see NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005 and http://secc.rti.org for details). This longitudinal study followed children and families from ten sites across the US—Little Rock, AR; Irvine, CA; Lawrence, KS; Boston, MA; Philadelphia, PA; Pittsburgh, PA; Charlottesville, VA; Morganton, NC; Seattle, WA; Madison, WI. Participants were recruited via hospital visits when children were born in 1991. Families were not eligible if the mother was under 18, did not speak English or had a substance abuse or serious health problem; if the family planned to move, lived too far from the study site or in a location deemed too dangerous for home visiting; or if the child was hospitalized for more than 7 days postpartum, had obvious disabilities, or had a twin. About half of the eligible families were invited to participate, using a conditional random sampling plan. Of those invited, 58% agreed to participate, leaving a final total sample of 1,364 families. The sample reflected the economic, educational and racial-ethnic diversity of the catchment area at each site, and included 24% racial/ethnic-minority children, 10% low-education mothers (less than a high school), and 14% single parents. Following an initial assessment at 1 month, children and their families were studied in a range of settings when children were 6, 15, 24, 36, and 54 months of age and in grades 1, 3 and 5 and again at 15 years-old.

As in any longitudinal study, some participants dropped out, missed occasional data collection points and/or had partial missing data on specific measures. For instance, while there were virtually no missing data on early family demographics, the response rate on the main outcome measures varied between 78% at 54 months and 65% at 15 years old (see Table 1 for details). In order to avoid potential bias resulting from deletion of incomplete cases, we used multiple imputation to handle missing data (Allison, 2001). Five multiply imputed data sets (created through the SAS MI procedure) were used for all descriptive and multivariate analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics (N = 1,364)

| Child’s age | Valid N |

% | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Characteristics | |||||

| Male | 1 m | 1364 | 51.7 | ||

| Race/Ethnicitya | |||||

| Black | 1 m | 1364 | 12.9 | ||

| Other | 1 m | 1364 | 6.7 | ||

| Maternal and Family Characteristics | |||||

| Educationb | 1 m | 1363 | 0.23 | 2.51 | |

| Childrearing beliefs | 1 m | 1358 | 75.61 | 16.85 | |

| Personality | 6 m | 1272 | 58.66 | 14.28 | |

| Vocabularyc | 36 m | 1167 | −1.83 | 18.98 | |

| Income-to-needsd | 1–54 m | 1355 | 0.39 | 2.70 | |

| Partnered | 1–54 m | 1364 | 83.7 | ||

| Neighborhood advantage | 1–54 m | 1289 | −0.01 | 1.02 | |

| Mediators | |||||

| Maternal depressive symptoms | 1–54 m | 1363 | 9.88 | 6.77 | |

| Quality of home learning env. | 6–54 m | 1305 | −0.02 | 1.03 | |

| Child care quality | 6–54 m | 1134 | 2.91 | 0.50 | |

| Classroom instructional quality | G1 | 965 | 15.63 | 5.16 | |

| School advantagee | K | 559 | 0.77 | 0.34 | |

| Children’s Achievement | |||||

| Vocabulary (WJ-R Vocabulary) | |||||

| 1 | 54 m | 1060 | 458.75 | 15.84 | |

| 2 | G1 | 1020 | 483.17 | 13.35 | |

| 3 | G3 | 1014 | 496.29 | 12.03 | |

| 4 | G5 | 992 | 505.36 | 13.71 | |

| 5 | 15 yo | 889 | 517.76 | 16.06 | |

| Reading (WJ-R Letter-word) | |||||

| 1 | 54 m | 1056 | 368.37 | 23.22 | |

| 2 | G1 | 1025 | 451.82 | 28.21 | |

| 3 | G3 | 1014 | 493.12 | 20.45 | |

| 4 | G5 | 993 | 509.48 | 20.72 | |

| Math (WJ-R Applied problems) | |||||

| 1 | 54 m | 1053 | 423.15 | 24.15 | |

| 2 | G1 | 1023 | 469.29 | 18.86 | |

| 3 | G3 | 1013 | 496.86 | 14.02 | |

| 4 | G5 | 993 | 509.28 | 15.09 | |

| 5 | 15 yo | 887 | 523.39 | 18.77 |

Reference category: White.

In years, centered at 14 years.

PPVT standardized scores, centered at 100.

Centered at 3.

The rate of missing data is higher on this variable because NCES data were not collected in all of the States every year; thus, participants in some sites did not have measures of school advantage before grade 3 (the same was true for those attending private schools, with principal data being available only in grade 3); to insure an acceptable level of data quality despite this systematic pattern of missing data, we included highly correlated measures of school advantage with wider coverage (i.e., in grade 3, 995 participants had a valid value) in the imputation process, thus increasing the precision of imputed data for this variable.

Note: Percentages, means and standard deviations based on multiply imputed data sets. M = months; env = environment; yo = years old; K = kindergarten; G1 = grade 1; G3 = grade 3; G5 = grade 5.

Measures

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all study variables.

Outcome measures

Vocabulary and reading and math achievement were measured with three different subtests of the Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery–Revised (WJ-R, Woodcock & Johnson, 1989). The vocabulary and applied-problems (math) subtests were administered on five occasions (54 months, grades 1, 3 and 5 and 15 years old). For reading achievement, however, no subtests were administered at all times; we thus selected the single subtest with maximum measurement occasions, the Letter-Word Identification (LW) subtest, which was administered four times (54 months, grades 1, 3 and 5)1. To monitor change over time more easily, raw scores for each subtests were converted to W scores, special transformations of the Rasch ability scale that centered the raw score on a value of 500. As expected, the average vocabulary, reading and math test scores gradually increased with age (see Table 1).

Neighborhood socioeconomic advantage

Family’s addresses were linked to 1990 (1–54 months) and 2000 (grade 1–15 years old) US Census data at the block group level to characterize the neighborhood environment. Census block groups are subdivisions of a census tract that comprise a combination of street blocks and contain from 600 to 3,000 residents (US Bureau of the Census, 1994). Census variables representing the percentage of adults with at least a B.A. degree (e.g., at 1 month, M1m = 27.40; SD1m = 18.39), the percentage of households with incomes greater than $100,000 (M1m = 5.41; SD1m = 8.89), and the percentage of adults in managerial/professional jobs (M1m = 34.14; SD1m = 14.78) were standardized and averaged to create a measure of neighborhood advantage at each major assessment (α = .86 to .93). These variables were selected based on previous factor analysis of US census measures that identified the presence of high-income, educated, professional/managerial workers as representing a distinct neighborhood dimension (e.g., Duncan & Aber, 1997), and on previous studies based on the NICHD SECCYD sample and using a similar measure (Crosnoe, Leventhal, Wirth, Pierce, & NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, forthcoming). In line with these results, a series of factor analyses with varimax rotation confirmed that these variables strongly loaded on a single factor distinct from neighborhood disadvantage (results available from authors upon request).

For analytic purposes, a standardized variable representing early neighborhood advantage was created by averaging the measures obtained at 1, 15, 36 and 54 months (α = .96). To assess the presence of non-linear associations with the outcome, this variable was then squared. In addition, to assess if neighborhood change after 54 months was associated with the outcomes, we created a time-varying variable centered at the 1–54 months measure of neighborhood advantage. This “within-child” time-varying covariate represents deviations from each child’s initial (1–54 months) value of neighborhood advantage and permits examination of whether subsequent increases or decreases in one’s relative position on neighborhood advantage are systematically associated with variations in achievement (Singer & Willett, 2003, pp. 173–191).

An important advantage associated with the use of such a within-child centered variable is that it essentially controls for potential unobserved time-invariant family and child confounds; however, this strategy still offers no guarantee against simultaneity bias and bias from time-varying confounds (see Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2006; Duncan, Magnuson, & Ludwig, 2004; Singer & Willett, 2003, pp. 173–191). Although there were some changes in neighborhood advantage over time, it is important to note that neighborhood characteristics tended to be stable, with correlations between the early (1–54 months) and later (grade 1 to 15 years old) neighborhood advantage measure ranging from .69 to .782. Children’s residential moves to more advantaged neighborhoods over time were uncommon, a tendency observed in other, nationally representative samples (Hango, 2003; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2001; South, Crowder, & Trent, 1998). For instance, between 54 months and grade 1, among those with valid data (n = 1035), only 85 children moved to a neighborhood at least one-half of a standard deviation above their initial neighborhood advantage level, and less than half of them (n = 36) remained in that neighborhood until at least grade 5. Neighborhood stability also was reflected in the mean neighborhood change (in absolute value) from one assessment to the next, which averaged below one-quarter of a standard deviation between 54 months and 15 years old (average M = 0.22; SD = 0.36).

Maternal depression was measured with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D, Radloff, 1977). Measures obtained at 1, 6, 15, 24, 36, and 54 months were averaged into a single composite (α = .84), and later measures (grade 1 through 15 years old) were used to construct a within-child time-varying covariate centered around the initial 1–54 months value, following a similar approach as that described earlier for neighborhood advantage.

Quality of home learning environment was measured with subscales from the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) inventory (Bradley & Caldwell, 1979). The HOME combines information from observations and maternal interview to evaluate the quality and structure of the home environment. Developmentally appropriate adaptations of the HOME were administered at different assessments. To facilitate longitudinal analysis of the HOME scales, composite scores representing comparable constructs were computed from the items available at each assessment. For the present analysis, we added the scores of three composites representing parental responsiveness, the presence of learning material and the level of stimulation in the home. Because the exact content and number of items in each composite varied at each assessment, the total scores were standardized to ensure comparability. A standardized variable representing early quality of the home learning environment was created by averaging the standardized measures from 6, 15, 36 and 54 months (α = .82). The same “within-child” centering approach described for neighborhood advantage was employed; later assessments of quality of the home learning environment were coded as time-varying covariates representing deviations from the early home quality measure3. Although quality of the home learning environment tended to be fairly stable over time, variation was seen, with correlations between the early home quality measure (6–54 months) and the later measures (grade 3 to 15 years old) ranging from .61 to .64.

Child care quality was measured with the Observational Rating of the Care Environment (ORCE), a standardized procedure created specifically for the NICHD SECCYD. Details about the procedure, training, coding and reliability of the ORCE are available elsewhere (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2002a), and only a general overview is provided here. Observations of child behaviors, caregiver-child interaction, and the child care environment were conducted with the ORCE at 6, 15, 24, 36, and 54 months in nonmaternal care arrangements that were used for at least 10 hours per week. A series of 44-minute observation cycles were made during half-day visits, and, at the end of each of these cycles, observers made judgments about the quality of the caregiving along several dimensions on a series of 4-point scales that ranged from not at all characteristic to highly characteristic. At 6, 15, and 24 months, these dimensions included the caregiver’s sensitivity to child’s nondistress signals, stimulation of child’s development, positive regard toward child, detachment (reflected), and flatness of affect (reflected). At 36 months, two additional subscales (fosters child’s exploration and intrusiveness [reflected]) were included in the positive caregiving composite. At 4½ years, the composite included four subscales, sensitivity and responsivity, stimulation of cognitive development, intrusiveness (reflected), and detachment (reflected). Cronbach’s alphas for the composite ranged from .72 to .89. A total quality score was computed by averaging mean scores obtained within each assessment from 6 to 54 months. A large majority of children (83%) had the quality of their child care environment rated at least once over the course of the study.

Classroom instructional quality was assessed in grade 1 with another instrument designed for this study, the Classroom Observation System (COS, see NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2002b for details about procedure, training, codification and reliability). As with the ORCE, the COS was based on 44-minute observation cycles made during half-day visits, and focused on the child’s activities, behavior, and interaction with the teacher as well as general features and activities of the whole classroom. At the end of each cycle, observers rated the quality of literacy instruction (e.g., rich literacy instruction and activities), evaluative feedback (e.g., teacher provides corrective feedback, encourages effort, persistence and creativity), instructional conversation (e.g., teacher provides explanations, synthesis and encourages reasoning), and child responsibility (e.g., opportunities for leadership roles) on a 7-point scale ranging from uncharacteristic to extremely characteristic. These three ratings were summed to assess the quality of classroom instruction in grade 14.

School advantage is captured by a variable representing the proportion of students not eligible to receive free lunch. National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) data describing basic school demographics were linked with children’s school history for each grade starting in kindergarten. The kindergarten measure was used as the initial school advantage score, and later scores were converted to time-varying within-child deviations, as described earlier for neighborhood advantage. It is important to note that the level of missing data was high for the kindergarten measure, as NCES data were not available for children attending private schools, and were not systematically available at all sites before grade 3. Fortunately, in grade 3, it was possible to obtain the proportion of students not eligible for free and reduced-price lunch for all participating children, including those in private schools, from a study questionnaire sent to school principals4. To insure an acceptable level of data quality in kindergarten despite the systematic pattern of missing data, we included highly correlated measures of school advantage in grades 1 to 9 in the imputation process. This procedure is likely to provide adequate estimate of school advantage in kindergarten, because school characteristics tended to be fairly stable over time. To illustrate, among those with valid data, the correlations among the kindergarten, grade 1, grade 2 and grade 3 measures were high (r = .75 to .91), probably because a majority of children remained in the same or similar schools (as was the case for neighborhoods).

Child and family background characteristics

To address concerns about selection bias, a number of factors likely to influence both neighborhood characteristics and children’s achievement were included as covariates. Child gender and race/ethnicity (White, Black, or other) and maternal education (in years, centered at 14 years)5 were controlled for in all analyses, as well as study site (with a set of dummy variables). Controls for maternal vocabulary (assessed at 36 months with standard scores from the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Revised [PPVT – R; Dunn & Dunn, 1981], centered at 100), maternal personality (assessed at 6 months with a composite of the neuroticism, extroversion, and agreeableness scales from the NEO Five-Factor Inventory, a short form of the NEO Personality Inventory [Costa & McCrae, 1985]) and parental beliefs about childrearing were also included. This last control was measured at 1 month with a 30-item questionnaire discriminating between “modern” and “traditional” beliefs, with higher scores indicating more nonauthoritarian childrearing beliefs (Schaefer & Edgerton, 1985). Also included as covariates were the proportion of data collection points when a husband/partner was present in the home from 1 to 54 months and the average income-to-needs ratio (total family income divided by the poverty level for the respective household size, centered at 3). A within-child time-varying variable centered at the initial value was also created for income-to-needs.

Results

Before moving to multivariate growth curves models (or hierarchical linear models HLMs), intercorrelations among the variables of primary interest were reviewed (see Table 2). Given that significant neighborhood effects emerged for the intercept only (see next section) and the relatively high correlations among achievement measures over time, we focused on achievement in grade 1. Neighborhood advantage was correlated in the expected direction with children’s vocabulary, reading and math achievement, as well as with the home, child care and school mediators, with comparatively stronger associations with home quality and school advantage. The five mediators were also positively associated with the three outcomes, and the strength of the association was especially strong for the home environment and, to a lesser degree, for school advantage. Children who lived in supportive homes were also more likely to be exposed to higher quality child care and school environments; no association emerged, however, between child care quality and classroom instructional quality.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Among Neighborhood Advantage, Home, Child Care, School, and Achievement Measures (N = 1,364)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Neighborhood advantagea | -- | ||||||||

| 2. | Maternal depressive symptomsa | −.21*** | -- | |||||||

| 3. | Quality home environmenta | .36*** | −.37*** | -- | ||||||

| 4. | Child care qualitya | .20*** | −.10** | .31*** | -- | |||||

| 5. | Classroom instructional quality | .15*** | −.07† | .14*** | .04 | -- | ||||

| 6. | School advantage | .39*** | −.19*** | .46*** | .21*** | .19*** | -- | |||

| 7. | Vocabularyb | .31*** | −.20*** | .46*** | .22*** | .08† | .32*** | -- | ||

| 8. | Readingb | .21*** | −.21*** | .33*** | .18*** | .11** | .25*** | .41*** | -- | |

| 9. | Mathb | .29*** | −.23*** | .41*** | .19*** | .08** | .32*** | .51*** | .60*** | -- |

Measures obtained between 1 and 54 months.

Based on grade 1 measures.

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10

Hierarchical Linear Models

A growth curve modeling strategy was selected to test our hypotheses. Analyses were conducted with the HLM 6.04 software (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2004). In level 1 equations capturing individual growth patterns, time was coded in terms of years (age in months/12) and centered at grade 1, while the slope described annual linear change in children’s achievement between 4.5 and grade 5 (for reading) or 15 years old (for vocabulary and math). We selected grade 1 as the intercept to ensure an adequate temporal order, because one of the mediators, classroom instructional quality, was measured only in grade 1. To account for this situation, this variable was coded into a time-varying variable with values set at 0 at 54 months. Thus, classroom quality was allowed to influence scores only starting in grade 16.

At level 1, quadratic models were selected to represent individual growth over time, based on visual examination of individual growth patterns, on results from previous studies using the same sample (e.g., NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2007) and on unconditional growth models indicating a significant quadratic slope for each of the three outcomes. At level 2, the intercept and slope were allowed to vary randomly, while the quadratic slope was fixed. Results of unconditional models with site as a covariate revealed significant variation in both the intercept and linear slope for each of the three outcomes; however, the intercept was estimated much more reliably (reliabilities between .88 and .91) than the slope (reliabilities between .35 and .45; complete results available from the authors upon request).

To estimate the role of neighborhood advantage, three models were tested in sequence for each outcome. First, neighborhood advantage was entered along with the full battery of controls to estimate linear associations between neighborhood advantage and the outcome. Then, a squared term was added in a second model, to assess the presence of non-linear effects. Finally, to investigate if changes in neighborhood advantage were associated with changes in the outcome, a third model incorporated time-varying deviation scores. The equations for this last model are provided in an Appendix as an illustration. When significant neighborhood effects emerged in one of these models, a second series of mediation models was estimated. In this second step, hypothesized mediators—maternal depression, quality of the home environment, child care quality, classroom instructional quality, and school advantage—were added one by one, before running full models including all significant mediators. The significance of mediation was formally assessed for models considering mediators separately and jointly, following a method tailored for hierarchical linear models (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001). In the next sections, results for children’s vocabulary and reading and math achievement are presented in sequence.

Before moving to the presentation of the HLM results, we should note that a series of preliminary analysis were conducted to determine which control variables had significant within-child effects and/or had non-linear associations with the achievement outcomes. All preliminary analyses included the full set of controls. Then, for each outcome (and when applicable), the time-varying and squared variables corresponding to each covariate were included one at a time. For the sake of parsimony, time-varying or squared control variables that had no significant associations with any of the three outcomes were then excluded from both the imputation procedure and final analysis. On the basis of these analyses, we included squared terms for maternal education, maternal vocabulary, maternal personality and family income-to-needs, while time-varying deviations were incorporated only for family income-to-needs.

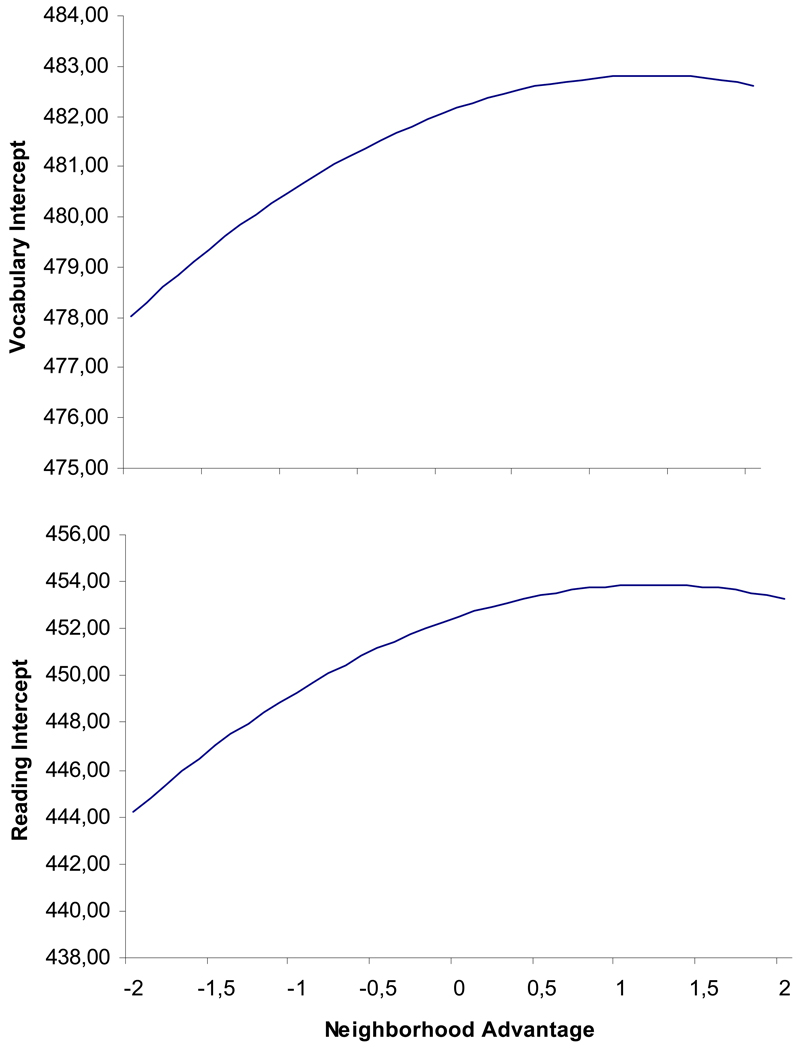

Vocabulary

Table 3 presents the results of the three models estimating the association between neighborhood advantage and children’s vocabulary. Model 1 shows that neighborhood advantage was marginally associated with the vocabulary intercept in a linear fashion, but not with the slope; however, Model 2 denotes the presence of a non-linear association between neighborhood advantage and the vocabulary intercept. With a positive linear trend and a negative quadratic term, we should expect a predominantly positive association that gradually levels off. The top panel of Figure 1 confirms this shape7. The figure illustrates that increases in neighborhood advantage were most strongly associated with children’s higher vocabulary scores in grade 1 for those living in relatively less advantaged neighborhoods. To further probe the quadratic association, simple slope analyses were conducted (Aiken & West, 1991). The results revealed that the association between neighborhood advantage and children’s vocabulary scores in grade 1 was significant until neighborhood advantage reached .58, at which point the simple slope was estimated at 0.65, with a SE = 0.33 and t = 1.96. In other words, neighborhood advantage was significantly associated with children’s better vocabulary scores until over one-half of a standard deviation above the mean of the neighborhood advantage measure, which corresponds to about the 77th percentile of its distribution.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Linear Models (HLMs) Predicting Vocabulary Between 54 Months and 15 Years Old (N = 1,364)

|

B (SE) Model 1 |

B (SE) Model 2 |

B (SE) Model 3 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter- cept |

Linear slope |

TV deviationa |

Inter- cept |

Linear slope |

TV deviationa |

Inter- cept |

Linear slope |

TV deviationa |

|

| Male | 1.81** | 0.06 | 1.77** | 0.06 | 1.77** | 0.06 | |||

| (0.49) | (0.07) | (0.49) | (0.07) | (0.49) | (0.07) | ||||

| Race | |||||||||

| Black | −5.75*** | −0.23 | −5.57*** | −0.24 | −5.57*** | −0.24 | |||

| (1.12) | (0.16) | (1.12) | (0.17) | (1.12) | (0.17) | ||||

| Other | 1.00 | 0.30* | 1.02 | 0.30* | 1.01 | 0.30* | |||

| (1.13) | (0.15) | (1.13) | (0.15) | (1.13) | (0.15) | ||||

| Maternal education | 0.59** | 0.02 | 0.56** | 0.03 | 0.56** | 0.03 | |||

| (0.16) | (0.02) | (0.16) | (0.02) | (0.16) | (0.02) | ||||

| Squared | −0.04 | −0.01† | −0.04 | −0.01† | −0.04 | −0.01* | |||

| (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.03) | (0.01) | ||||

| Maternal vocabulary | 0.23*** | 0.00 | 0.23*** | 0.00 | 0.23*** | 0.00 | |||

| (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | ||||

| Squared | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||

| Maternal personality | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | |||

| (0.12) | (0.02) | (0.12) | (0.02) | (0.12) | (0.02) | ||||

| Squared | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||

| Childrearing beliefs | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.00 | |||

| (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | ||||

| Income-to-needs | 0.70** | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.69** | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.68** | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| (0.20) | (0.03) | (0.06) | (0.20) | (0.03) | (0.06) | (0.20) | (0.02) | (0.06) | |

| Squared | −0.04* | 0.00 | −0.04* | 0.00 | −0.04* | 0.00 | |||

| (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | ||||

| Mother partnered | −0.55 | −0.09 | −0.45 | −0.09 | −0.45 | −0.09 | |||

| (1.01) | (0.14) | (1.00) | (0.14) | (1.00) | (0.14) | ||||

| Neig. advantage 1–54m | 0.58† | −0.08 | 1.15** | −0.11† | 1.19** | −0.10 | 0.20 | ||

| (0.33) | (0.05) | (0.41) | (0.06) | (0.43) | (0.06) | (0.33) | |||

| Squared | −0.43* | 0.02 | −0.42* | 0.02 | |||||

| (0.19) | (0.03) | (0.19) | (0.03) | ||||||

Time-varying deviations are obtained by centering around each child’s initial value of the variable (Time-1 centering, see Singer & Willett 2003, p.176).

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05;

p < .10.

Note. All models include site as a covariate on the intercept and linear slope. Standard errors in brackets. Neig. = Neighborhood, M = months, TV = Time-varying.

Figure 1.

Non-linear associations between neighborhood advantage and children’s vocabulary (based on Model 2, Table 3) and reading achievement (based on Model 2, Table 4); control variables are fixed at their average value.

To evaluate practical significance of these findings, effect sizes (d) associated with increases of one standard deviation (SD) in neighborhood advantage were computed in different regions of the curve. First, we calculated the difference between the expected score at −2 SD and −1 SD from the mean, and divided this difference by the SD of the outcome measure, here the SD for vocabulary in grade 1, since the models were centered there. This calculation indicated a moderate effect size in that region of the curve (d = [480.48 – 478.03] / 13.35 = 0.18). As expected, the effect size diminished when the calculation involved the difference in expected scores between −1 SD below the mean and the mean value (d = [482.05 – 480.48] / 13.35 = 0.12), and was reduced even further when the difference between the expected score at the mean and 1 SD above it was considered (d = [482.77 – 482.05] / 13.35 = 0.05). In an effort to assess the relative magnitude of these effects, we calculated the average effect sizes associated with 1 SD increases for other family background variables generally considered important for children’s achievement, including maternal education (d = 0.56 × 2.51 / 13.35 = 0.11), maternal vocabulary (d = 0.23 × 18.98 / 13.35 = 0.33) and family income (d = 0.69 × 2.70 / 13.35 = 0.14). Here, the average ds were obtained by calculating the product of the estimated linear coefficient associated with the variable of interest and its SD, again divided by the SD of the outcome measure. These results suggest that among children living in relatively less advantaged neighborhoods, the magnitude of the effect associated with increasing neighborhood advantage is comparable to that of maternal education and family income, and about half that of maternal vocabulary.

In Model 3, variations in neighborhood advantage occurring after 54 months were not systematically associated with changes in children’s vocabulary scores.

Reading achievement

Table 4 presents similar models for reading achievement. In general, the pattern of results was similar to vocabulary, with Model 1 showing only a marginally significant linear association between neighborhood advantage and the reading intercept, and Model 3 indicating no significant effect of neighborhood change. Here again, Model 2 indicates the presence of a non-linear, concave downward relationship between neighborhood advantage and the reading intercept. The lower panel of Figure 1 confirms that the shape of the relationship is similar, with increases in neighborhood advantage more strongly associated with children’s higher initial reading scores for those living in relatively less advantaged neighborhoods. Simple slope analyses revealed that the association with the outcome was significant until neighborhood advantage reached .60, at which point the simple slope was estimated at 1.14, with a SE = 0.58 and t = 1.96. Thus, neighborhood advantage was positively associated with children’s reading scores until past one standard deviation above its mean, which corresponds to about the 78th percentile of the neighborhood advantage distribution.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Linear Models (HLMs) Predicting Reading Between 54 Months and 15 Years Old (N = 1,364)

|

B (SE) Model 1 |

B (SE) Model 2 |

B (SE) Model 3 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter- cept |

Linear slope |

TV deviationa |

Inter- cept |

Linear slope |

TV deviationa |

Inter- cept |

Linear slope |

TV deviationa |

|

| Male | −3.23** | 0.68** | −3.32** | 0.69** | −3.32** | 0.69** | |||

| (1.02) | (0.19) | (1.03) | (0.19) | (1.03) | (0.19) | ||||

| Race | |||||||||

| Black | −5.57** | −0.31 | −5.19** | −0.36 | −5.18** | −0.36 | |||

| (1.72) | (0.42) | (1.70) | (0.42) | (1.70) | (0.41) | ||||

| Other | 1.73 | −0.41 | 1.77 | −0.41 | 1.77 | −0.42 | |||

| (1.94) | (0.39) | (1.93) | (0.39) | (1.93) | (0.39) | ||||

| Maternal education | 1.36*** | −0.10 | 1.28*** | −0.09 | 1.28* | −0.09 | |||

| (0.32) | (0.06) | (0.32) | (0.06) | (0.32) | (0.06) | ||||

| Squared | −0.14* | 0.01 | −0.14* | 0.01 | −0.14* | 0.01 | |||

| (0.06) | (0.01) | (0.06) | (0.01) | (0.06) | (0.01) | ||||

| Maternal vocabulary | 0.21*** | 0.01 | 0.21* | 0.01 | 0.21*** | 0.01 | |||

| (0.04) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.01) | ||||

| Squared | 0.00† | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||

| Maternal personality | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.02 | |||

| (0.24) | (0.06) | (0.23) | (0.06) | (0.23) | (0.06) | ||||

| Squared | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||

| Childrearing beliefs | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | |||

| (0.04) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.01) | ||||

| Income-to-needs | 1.54** | −0.13 | 0.09 | 1.51** | −0.13 | 0.09 | 1.51** | −0.13 | 0.09 |

| (0.43) | (0.08) | (0.22) | (0.44) | (0.08) | (0.22) | (0.44) | (0.08) | (0.22) | |

| Squared | −0.11** | 0.01 | −0.10* | 0.00 | −0.10* | 0.00 | |||

| (0.04) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.01) | ||||

| Mother partnered | −0.20 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.19 | |||

| (1.98) | (0.36) | (1.98) | (0.36) | (1.97) | (0.36) | ||||

| Neig. advantage 1–54m | 1.03† | −0.15 | 2.26** | −0.32† | 2.25** | −0.32 | −0.05 | ||

| (0.58) | (0.14) | (0.72) | (0.17) | (0.74) | (0.19) | (0.71) | |||

| Squared | −0.95** | 0.13† | −0.95** | 0.13† | |||||

| (0.33) | (0.07) | (0.33) | (0.07) | ||||||

Time-varying deviations are obtained by centering around each child’s initial value of the variable (Time-1 centering, see Singer & Willett 2003, p.176).

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05;

p < .10.

Note. All models include site as a covariate on the intercept and linear slope. Standard errors in brackets. Neig. = Neighborhood, M = months, TV = Time-varying

Effect sizes associated with increases of 1 SD in terms of neighborhood advantage were computed in the same regions of the curve as for vocabulary. The calculation of the effect sizes associated with the difference between the expected score at −2 SD and −1 SD from the mean indicated a moderate effect size in that region of the curve (d = [449.32 – 444.22] / 28.21 = 0.18). Again, the effect sizes diminished as neighborhood advantage increased (d between −1 SD and the mean = [452.53 – 449.32] / 28.21 = 0.11; d between the mean and 1 SD above it = [453.84 – 452.53] / 28.21 = 0.05). As benchmarks, average effect sizes were also calculated for maternal education (d = 1.28 × 2.51 / 28.21 = 0.11), maternal vocabulary (d = 0.21 × 18.98 / 28.21 = 0.14) and family income (d = 1.51 × 2.70 / 28.21 = 0.14). Again, these results suggest that at least in the lower half of the neighborhood advantage distribution, the effect sizes associated with neighborhood advantage are roughly comparable to that of maternal education, maternal vocabulary and family income.

Math achievement

The same models were also conducted for math achievement. Results from the first model again revealed a marginally significant linear association between neighborhood advantage and children’s math intercept (B = 0.73, SE = 0.43, p = .09). In the second model incorporating the quadratic term, the linear association became significant (B = 1.19, SE = 0.56, p = .04), but the associated quadratic term did not reach statistical significance (B = −0.35, SE = 0.30, p = .25). These results indicate that the association between neighborhood advantage and math achievement followed a similar shape as those found for reading and vocabulary, although the quadratic coefficients did not reach significance (but see results of alternative specifications in footnote 7). Because the quadratic term was not significant and the linear effect alone was only marginally significant, mediation was not investigated for math achievement. Finally, in the third model, the time-varying variable representing changes in neighborhood advantage had no significant association with children’s math scores (B = −0.20, SE = 0.46, p = .67), consistent with the other outcomes.

Tests of Mediation

Formally testing for mediational effects in hierarchical linear models involves the consideration of two aspects: 1) the association between the initial variable (here neighborhood advantage) and mediators net of covariates; and 2) the association between mediators and outcomes, independent of the effect of the initial variable and covariates (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001). Once the two coefficients representing the independent association between the initial variable and a mediator and between the mediator and the outcome are known, the mediated effect can be estimated by computing the product of these coefficients, and statistical tests such as the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982) can be used to estimate its significance.

For the first aspect, associations between neighborhood advantage and the mediators, all level-2 variables, were evaluated in OLS regression models adjusting for the full battery of level-2 controls following Krull and MacKinnon’s (2001) recommendations. Results of these models confirmed significant positive associations between neighborhood advantage and quality of the home (B = 0.08, SE = 0.03, p = .017), child care (B = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p < .001) and classroom (B = 0.59, SE = 0.19, p = .004) environments, as well as with school advantage (B = 0.06, SE = 0.01, p < .001), net of covariates. However, maternal depression was not significantly associated with neighborhood advantage (B = 0.00, SE = 0.25, p = .99). The associations were especially strong for the child care and school environments. In preparation for the full models including more than one mediator at a time, additional regression analysis were conducted to estimate the association between neighborhood advantage and each of the mediators while inserting other relevant mediators in the equation as covariates8. When competing mediators were added as covariates in the equation, the association between neighborhood advantage and quality of the home environment became non-significant.

For the second aspect, a series of models introducing the mediators one by one were tested for vocabulary and reading achievement, the two outcomes with significant associations with neighborhood advantage9. Then, for each outcome, a final model including all of the mediators that were individually significant was estimated. For all of these models, Sobel tests of mediation were performed to investigate statistical significance of the mediated effect (calculated as the product of the coefficients). Because the power to detect significant mediation effects with the Sobel test is comparatively low (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002), Sobel tests were one-tailed. The results of all of these models and of associated mediated effects are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hierarchical Linear Models (HLMs) Predicting Vocabulary and Reading Achievement Intercepts: Testing Mediation of Neighborhood Effects (N = 1,364).

| Vocabulary |

Reading |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Regression models | ||||||||||||

| Neigh. advantage | 1.15** | 0.92** | 0.95* | 1.16** | 1.02* | 0.80* | 2.26** | 1.92* | 2.01** | 2.24** | 1.79* | 1.42† |

| (0.41) | (0.40) | (0.41) | (0.42) | (0.42) | (0.40) | (0.73) | (0.74) | (0.73) | (0.73) | (0.79) | (0.79) | |

| Neigh. advantage sq | −0.43* | −0.37* | −0.38* | −0.43* | −0.41* | −0.34† | −0.94** | −0.85* | −0.88** | −0.94** | −0.86* | −0.75* |

| (0.19) | (0.18) | (0.18) | (0.19) | (0.19) | (0.18) | (0.33) | (0.33) | (0.32) | (0.33) | (0.33) | (0.33) | |

| Maternal depression | −0.04 | −0.23* | ||||||||||

| (0.05) | (0.10) | |||||||||||

| Quality home envir. | 2.99*** | 2.80*** | 4.38*** | 4.08*** | ||||||||

| (0.44) | (0.43) | (0.70) | (0.69) | |||||||||

| Child care quality | 2.64*** | 1.84** | 3.42** | 2.06† | ||||||||

| (0.64) | (0.61) | (1.11) | (1.15) | |||||||||

| Class. quality | −0.03 | 0.05 | ||||||||||

| (0.06) | (0.12) | |||||||||||

| School advantage | 2.15 | 7.82† | 6.19† | |||||||||

| (1.63) | (3.81) | (3.50) | ||||||||||

| Mediated effects | ||||||||||||

| Maternal depression | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| (0.01) | (0.06) | |||||||||||

| Quality home envir. | 0.23* | 0.16* | 0.34* | 0.17† | ||||||||

| (0.10) | (0.09) | (0.15) | (0.13) | |||||||||

| Child care quality | 0.19** | 0.12* | 0.25** | 0.11† | ||||||||

| (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.10) | (0.07) | |||||||||

| Class. quality | −0.02 | 0.03 | ||||||||||

| (0.03) | (0.07) | |||||||||||

| School advantage | 0.13† | 0.48* | 0.36* | |||||||||

| (0.10) | (0.24) | (0.21) | ||||||||||

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10.

Note: All models include the full set of controls on both the intercept and slope. The significance of the mediated effects is based on one-tailed Sobel tests.

Vocabulary

The left panel of Table 5 presents the results for vocabulary. Models 1 to 5 indicate that only quality of the home and child care environments were significant mediators, while school advantage was marginally one. Model 6, incorporating both the home and child care environment as mediators, suggests that the magnitude of mediation was similar for both the home and child care environments, but the level of significance was slightly higher for the child care environment (p = .01), as compared with the home (p = .04). In other words, despite the fact that the home environment had a stronger direct association with children’s vocabulary, the quality of the child care environment appeared more important for explaining the association between neighborhood advantage and children’s vocabulary scores (recall here that the association between neighborhood advantage and the quality of the home environment became non-significant when the quality of the child care environment was included as a covariate in the regression equation). It is important to note that only part of this association was accounted for by the two mediators. Indeed, the positive linear association between neighborhood advantage and children’s vocabulary scores remained significant in Model 6, and the mediators explained only about one-third of this effect ([1.15 – 0.80]) / 1.15 = 0.30).

Reading

The right panel of Table 5 presents the results for reading. Results of Models 1 to 5 reveal significant mediated effects for three variables, including the home and child care environments, and school advantage. Model 6 incorporated the three significant mediators. In this model, only the school environments showed a significant mediated effect, while the home and child care environment were marginally significant, despite the fact that the home environment had the strongest direct association with the outcome. Again, the strength of the mediated effects were somewhat stronger for child care (p = .066) than for the home (p = .096) environment. Thus, for reading, school advantage played a unique role in explaining the association between neighborhood advantage and children’s reading achievement, along with the quality of the child care and home environments, although to a lesser degree. Together, the mediators incorporated in Model 6 also explained about a one-third of the positive linear association between neighborhood advantage and reading scores ([2.26 – 1.42]) / 2.26 = 0.37).

Discussion

This study examined the mechanisms underlying the association between neighborhood socioeconomic advantage and children’s achievement trajectories through adolescence. It also examined the shape of this association. Building on Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological system theory and on related theories of neighborhood effects (see Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002), we proposed that neighborhood socioeconomic circumstances would influence the family, child care, and school environments, such that children living in advantaged neighborhoods would be exposed to enriched experiences across these contexts, as compared with their peers living in less advantaged neighborhoods. In turn, exposure to advantaged settings was expected to increase children’s achievement. In addition, just like income gains are especially important for children growing up in poor families (Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2001), we hypothesized that exposure to affluent, educated neighbors would be especially important at the lower end of the neighborhood advantage continuum. Results from growth curve models generally supported these hypotheses for children’s vocabulary and reading achievement, while a consistent but weaker pattern was observed for their math achievement. We discuss these results in two steps. First, we consider the shape and strength of the neighborhood-achievement link. Second, we look at the mechanisms underlying this link.

Neighborhood Advantage and Achievement: Shape and Strength of the Link

Results showed that neighborhood advantage was associated with children’s vocabulary and reading scores in a non-linear fashion, after taking into account a number of potential confounds, including child gender and race/ethnicity, and family structure and income as well as a range of maternal characteristics (education, vocabulary, personality, childrearing beliefs, depression). For both outcomes, neighborhood advantage seemed to matter most for children’s achievement in relatively less advantaged neighborhoods. That is, the presence of educated, affluent professionals in the neighborhood had a favorable association with children’s achievement until it leveled off at moderate levels of advantage. Correspondingly, the magnitude of the neighborhood-achievement link was not constant across the whole range of neighborhoods. In the lower range of the continuum — that is, in relatively less advantaged neighborhoods—neighborhood effects were found to be larger than at the higher end of the distribution, with effect sizes comparable to those of other factors generally recognized as important for achievement, such as maternal education or family income. For the sample as a whole, however, neighborhood effects were small, consistent with findings from much of the literature (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Thus, the results indicate that the magnitude of the association between neighborhood advantage and children’s achievement varies by the extent of neighborhood advantage.

This non-linear association is consistent with social isolation, institutional resources, and collective socialization perspectives. On the one hand, the social isolation perspective suggests that negative impacts on youth emerge when middle-class residents with mainstream values and lifestyles are largely absent from a community (Wilson, 1987). Previous findings suggest that it is indeed under such conditions that youth educational and economic outcomes are especially poor (Carpiano, Lloyd, & Hertzman, 2009; Crane, 1991; Vartanian & Buck, 2005). On the other hand, both the institutional resources and collective socialization perspectives imply that youth achievement should increase gradually as the proportion of affluent and educated professionals increases, with their presence consolidating the quality of local services and strengthening community social organization, including the presence of adult role models and supervision (see Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Results from other studies looking at non-linear associations between neighborhood advantage and youth outcomes are consistent with this incremental view (Duncan, Connell, & Klebanov, 1997; Kauppinen, 2007; Vartanian & Buck, 2005). These apparently conflicting points of view are not necessarily incompatible: even if the worst outcomes are observed in neighborhoods with very few middle-class residents, additional improvements may occur as the proportion of such residents increase, although perhaps along a less abrupt gradient. Results of the present study suggest that both models may apply, with more pronounced differences in children’s achievement found between less advantaged neighborhoods and moderately advantaged ones, along with moderate benefits still observable for most of the neighborhood advantage distribution.

At a certain point though, at about the 75th percentile, the positive association between neighborhood advantage and children’s achievement reached a plateau beyond which increases in the proportion of advantaged residents were no longer associated with higher achievement. This pattern may arise because mainstream norms and associated collective socialization mechanisms become firmly established as soon as a significant proportion of residents are educated, affluent professionals (i.e., a tipping point). It could also be related to the observation that in very affluent communities, the demanding careers of many parents leave less time for them to invest in neighborhood institutions and to generate the benefits associated with participation and social capital, which may offset additional gains in achievement (Luthar, 2003). In addition, children in mixed-income communities may fare best, with benefits both from the advantages associated with the presence of affluent, educated residents and from the presence of services aimed at lower-income families (Carpiano, Lloyd, & Hertzman, 2009). Because much extant neighborhood research focuses on concentrated disadvantage rather than concentrated advantage, these hypotheses require further investigation.

While neighborhood advantage was associated with children’s vocabulary and reading scores in grade 1, it was not associated with learning rates in these domains. In the same manner, changes in neighborhood advantage following residential moves or neighborhood improvement or decay were not linked with changes in children’s achievement scores over time either. Because intercept effects are more prone to selection bias as compared with slope and within-child effects, this pattern of results raises the possibility that the neighborhood-achievement link may be due to unobserved variables (see Limitation section). Alternatively, the results may indicate that neighborhood advantage sets children on a higher achievement course early and that this early advantage is unchanged as children progress in the school system. This “carry-forward” pattern is consistent with other findings indicating that early neighborhood conditions may have a long-term impact on achievement (Leventhal, Xue, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006; Lloyd, Li, & Hertzman, 2010; Sampson, Sharkey, & Raudenbush, 2008). Finally, measurement issues represent a third explanation for the lack of slope and change effects. First, learning rates were estimated much less reliably than initial statuses. To track neighborhood effects on learning rates more effectively, studies with more frequent assessments of achievement based on measures highly sensitive to change are needed (e.g., Fuchs, Fuchs, & Compton, 2004). Second, those who moved usually relocated to fairly similar neighborhoods, restricting the magnitude of changes in neighborhood characteristics. The lack of variation in neighborhood change observed in this study (comparable to other samples including nationally representative ones, Hango, 2003; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2001; South, Crowder, & Trent, 1998), combined with the relatively small sample size, certainly limited our ability to detect neighborhood change effects.

Explaining Links between Neighborhood Advantage and Achievement

Beyond simply observing an association between neighborhood advantage and children’s achievement, this study’s major contribution is the examination and comparison of the potential mediating role of three major proximal contexts of development—the family, child care and school environments. Substantial theoretically oriented work has put forward these contexts as central for understanding neighborhood effects on achievement (see Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). Detailed and integrated theoretical formulations of the impact of neighborhood advantage on the level of stimulation provided in the family and neighborhood institutions and in turn children’s achievement, however, are lacking, as is empirical work comprehensively testing these propositions. Indeed, the few available empirical evaluations suffer from important limitations. Previous studies have focused on only one mechanism at a time, limiting their ability to provide a more complete understanding of the processes at play. In addition, neighborhood studies looking at institutional resources have relied on “empirical measures … limited to the mere presence of neighborhood institutions based on survey reports … and archival records” (Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002, p. 458).

In contrast, the present study used strong, on-site observational measurement to examine the respective role of two institutions central to children’s achievement — child care and classroom environments. An indicator of school advantage was used too, to assess the role of school compositional effects, which in part reflect neighborhood socioedemographic makeup. The home environment also was assessed using a semi-structured measure with an observational component, which is less subject to problems of shared method variance inherent in much of the neighborhood literature. Maternal depression was considered as well, but had no mediating role. Our study demonstrated that, together, the home, child care and school environments accounted for about one-third of the positive association between neighborhood socioeconomic advantage and children’s vocabulary and reading scores. When both sources of advantage, in the home and in institutions, were considered simultaneously, institutional factors — that is, the child care and school contexts — appeared to take precedence over the home environment in explaining neighborhood effects (although the quality of the home environment had stronger direct effects). The school environment played a mediating role only for reading, perhaps because reading instruction is a primary mission in the early school years.

The quality of the home environment appears to play a lesser role in terms of mediation mainly because its association with neighborhood advantage was weak (and nonexistent for maternal depression) once various important family background characteristics were taken into account. In other words, neighborhood advantage was found to have a relatively small association with quality of the home environment after controlling for selection of advantaged families into advantaged neighborhoods. In contrast, strong associations with neighborhood advantage were observed for quality of the child care environment and for school advantage, even after controlling for the same family background characteristics. Thus, children raised in advantaged neighborhoods appear to receive higher quality child care and to attend more advantaged schools, even when family characteristics such as the quality of the home environment are held constant. In turn, access to advantaged institutions may explain why children in comparatively advantaged neighborhoods tended to have higher vocabulary and reading scores than their peers in less advantaged neighborhoods. In addition, community characteristics may be especially relevant for collective resources such as child care centers and schools, more so than for individual home routines and practices. Individual parents certainly have the primary influence over what goes on inside their homes. On the other hand, while parents can and do have an impact on institutions serving children, the power of any individual parent over these institutions nevertheless remains limited, leaving more room for collective factors to operate.