Abstract

Aven is a regulator of the DNA damage response and G2/M cell cycle progression. Overexpression of Aven is associated with poor prognosis in patients with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia, and altered intracellular Aven distribution is associated with infiltrating ductal carcinoma and papillary carcinoma breast cancer subtypes. Although Aven orthologs have been identified in most vertebrate species, no Aven gene has been reported in invertebrates. Here, we describe a Drosophila melanogaster open reading frame (ORF) that shares sequence and functional similarities with vertebrate Aven genes. The protein encoded by this ORF, which we named dAven, contains several domains that are highly conserved among Aven proteins of fish, amphibian, bird and mammalian origins. In flies, knockdown of dAven by RNA interference (RNAi) resulted in lethality when its expression was reduced either ubiquitously or in fat cells using Gal4 drivers. Animals undergoing moderate dAven knockdown in the fat body had smaller fat cells displaying condensed chromosomes and increased levels of the mitotic marker phosphorylated histone H3 (PHH3), suggesting that dAven was required for normal cell cycle progression in this tissue. Remarkably, expression of dAven in Xenopus egg extracts resulted in G2/M arrest that was comparable to that caused by human Aven. Taken together, these results suggest that, like its vertebrate counterparts, dAven plays a role in cell cycle regulation. Drosophila could be an excellent model for studying the function of Aven and identifying cellular factors that influence its activity, revealing information that may be relevant to human disease.

Key words: Drosophila melanogaster, Aven, Ataxia telangiectasia mutated, ATM and Rad 3-related, cell cycle, checkpoint

Introduction

In eukaryotic organisms, progression through the cell cycle is regulated by proteins that recognize cellular damage and activate checkpoint pathways. Various types of stress as well as developmental cues can activate these checkpoints, thereby delaying cell cycle progression at different stages. For instance, genotoxic stress typically leads to cell cycle arrest at either the G1-to-S transition, within S phase or at the G2-to-M transition;1,2 this allows the DNA repair machinery to fix the damage before cell division.3,4 If efficient repair is not possible, cells undergo apoptotic death.5

Two members of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase related kinase (PIKK) family, ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM and Rad 3-related (ATR), are important mediators of DNA damage checkpoints. In mammals, ATM is activated primarily by double-strand breaks (DSBs),6 whereas ATR typically responds to single stranded (ss)DNA.7–10 Interestingly, ATM and ATR appear to regulate each other, with ssDNA byproducts of ATM-dependent repair of DSBs resulting in ATR activation,11 and ATR being required to maintain the checkpoint initiated by ATM.12 Upon DNA damage, ATM and ATR phosphorylate and activate several downstream mediators of cell cycle arrest, including the checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Chk2.13 Activation of ATM by DSBs, for instance, leads to ATM-mediated phosphorylation of Chk2 on Thr68, resulting in Chk2 activation.14,15 Once activated, Chk2 phosphorylates Cdc25C on Ser216, inhibiting its enzymatic activity and causing G2 arrest.16 Activated Chk2 can also phosphorylate the tumor suppressor p53 on Ser20, resulting in p53 stabilization and G1 arrest.17 If DNA damage cannot be repaired, p53 is able to trigger programmed cell death via transcriptional activation of several pro-apoptotic factors such as FAS, Bax and PUMA.18

Several core proteins of cell cycle checkpoints and apoptotic pathways in vertebrate organisms are evolutionarily conserved in Drosophila melanogaster. For example, Drosophila orthologs of ATM (named Tefu/dATM)19,20 and ATR (MEI-41/dATR)21 have been identified. MEI-41/dATR functions as the main activator of DSBs-induced checkpoints during all phases of the cell cycle,21–25 whereas Tefu/dATM is principally involved in telomere stabilization and regulation of the Drosophila p53 ortholog (Dmp53) during induction of apoptosis.19,20,26–29 The checkpoints activated by Tefu/dATM and MEI-41/dATR appear to be mediated entirely by fly orthologs of Chk1 and Chk2, named grp/Dmchk1 and lok/Dmchk2, respectively.24,30–32 In response to DNA damage, for instance, Dmp53 is phosphorylated in a Dmchk2-dependent manner31 and is required for apoptosis induction via transcription of pro-apoptotic genes like reaper.33 In contrast to p53 found in vertebrates, Dmp53 does not appear to have a role in DNA damage-induced arrest, since Dmp53null flies display normal cell cycle arrest following DNA damage.34,35

Aven, a recently reported activator and substrate of ATM, regulates cell cycle progression at the G2/M transition.36 Experiments performed in cycling Xenopus egg extracts showed that depletion of endogenous Aven eliminates checkpoint activation induced by DNA damage, whereas exogenous expression of either human or Xenopus Aven causes DNA damage-independent ATM activation and cell cycle arrest.36,37 In human cells, ATM activation in response to DSBs is significantly reduced by RNAi-mediated knockdown of Aven.36 Thus, the presence of Aven appears to be required for an efficient activation of the ATM-mediated checkpoint response to genotoxic stress in vertebrate species.

Although Aven orthologs have been identified in most vertebrates, no Aven gene has been reported in invertebrate organisms. Here, we describe a Drosophila melanogaster ORF that shares sequence similarities with Aven genes and report that its protein product can affect cell cycle parameters in Drosophila cells and Xenopus egg extracts.

Results

Identification of a Drosophila Aven ortholog.

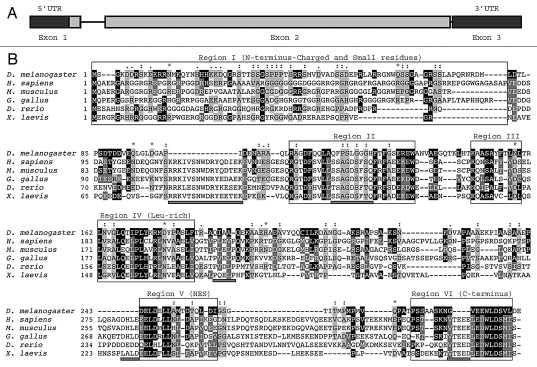

A TBLASTN search of the Drosophila sequence database (FlyBase; www.flybase.org) was performed using human Aven (hAven; amino acids 1-362) as a query. This resulted in the identification of a putative Aven-like ortholog (gene CG15727), which we named dAven. According to Flybase, dAven is predicted to map to region 11B5 on chromosome X and contain three exons spanning 1,229 bp, including a 95-bp 5'-UTR, an 885-bp coding region and a 185-bp 3'-UTR (Fig. 1A). The dAven gene encodes a 294 amino acid protein that is 20.4% identical and 45.6% similar to human Aven. Sequence alignment revealed conservation of the predicted dAven protein with Aven proteins from fish, amphibians, birds and mammals in various protein regions (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Genomic structure of the dAven gene. The three predicted exons of dAven are represented by rectangles connected by lines representing introns. The first exon includes a 95-bp 5′-UTR (untranslated region; dark grey) and a 885-bp coding region (light grey), whereas the rest of the coding sequence is located within the second exon (grey box). The third exon is composed of a 185-bp 3′-UTR (dark grey). (B) Alignment of the predicted dAven protein sequence and Aven proteins from various vertebrate species. The predicted amino acid sequence of dAven (AY071046) was manually aligned with those of Aven proteins of human (NP_065104.1), mouse (NP_083120), bird (NP_001005791), frog (NP_001090621) and fish (NP_001038757) origins. Identical residues (white letters in black boxes) and highly conserved residues (white letters in dark grey boxes) in dAven that are conserved in at least two other species are highlighted. Other conserved residues are shown in black letters and a light grey box. (:) indicates small residues (G, A, S, P, T, D, N); (.) indicates charged residues (K, R, D, E, H); and (*) indicates polar residues (K, R, D, E, N, Q).

Little is known about functional protein domains in Aven; therefore, we selected regions that are either highly conserved or share similar characteristics among Aven molecules from various species, and arbitrarily assigned them a number to facilitate their analysis (i.e., Fig. 1B, Region I, II, etc.). Although the N-terminal domain of Aven proteins (Region I in Fig. 1B); approximately the first fourth of the molecules) does not contain a recognizable motif, the region is typically rich in charged residues (ranging from 29.5%–46.9%), mainly basic amino acids (ranging from 23.9%–35.9%), and contains a high number of very small residues such as glycine, alanine, proline and serine (ranging from 37.5–64.8%). The N terminus of dAven falls within those ranges, being 37.5 % charged (24.4% basic) and having 35% of very small residues. Most of the protein regions following the N terminus that are highly conserved among Aven proteins from vertebrate species are also present in dAven. These include a domain that contains several aromatic residues (Fig. 1B, Region II), a short sequence containing hydrophobic/aromatic residues (Fig. 1B, Region III), a leucine-rich domain (Fig. 1B, Region IV), part of a recently reported nuclear export sequence (NES)37 (Fig. 1B, Region V) and the C-terminal domain (Fig. 1B, Region VI). However, a few sequence motifs that are highly conserved in vertebrates appear to be absent in dAven (Fig 1B, sequences underlined by grey bars). These include a tryptophan-containing domain preceding Region II, a phenylalanine-containing peptide within Region II, a short proline-rich sequence after Region IV, and acidic peptides preceding Region V and within Region VI (Fig. 1B). Outside of these regions, there are no identifiable or conserved consensus protein motifs present in the group of species analyzed.

dAven expression in Drosophila cells and embryos.

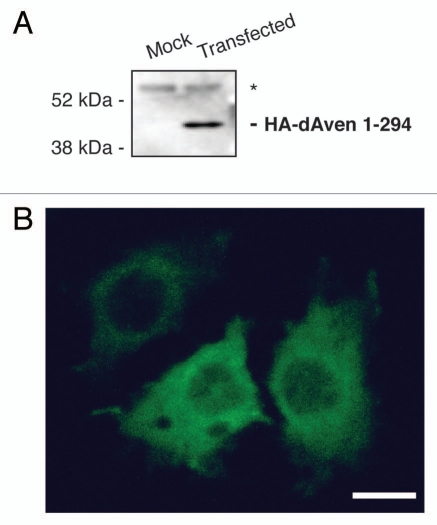

A full-length cDNA of dAven (RE13534) was obtained from the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (DGRC), and the entire ORF was subcloned into an insect expression vector (pMT/V5-His) as a fusion with an N-terminal human influenza hemagglutinin (HA)-tag sequence. Immunoblot analysis of transiently transfected S2R+ cells expressing HA-dAven detected a polypeptide of ∼45 kDa (Fig. 2A). Immunofluorescence experiments showed that dAven is mainly cytosolic in these cells, with a small fraction of the protein localizing to the nucleus (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Expression of dAven in Drosophila S2R+ cells. (A) Immunoblot of HA-tagged dAven expressed in S2R+ cells. Expression of dAven in S2R+ cells was achieved by transfection with a pMT/V5-His plasmid coding for HA-dAven followed by CuSO4 addition to the media to induce protein production. Extracts from these cells (transfected) and mock transfected controls (mock) were analyzed by PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibodies. (*) indicates a non-specific band present in both samples. (B) Immunolocalization of HA-tagged dAven transiently expressed in S2R+ cells. S2R+ cells were grown in coverslips and later transfected and induced as in (A). Subsequently, cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with acetone and probed with anti-HA antibodies followed by anti-Rabbit-FITC conjugates. A representative immunofluorescence image is shown. Controls with anti-HA stain on cells transfected with an empty vector were completely devoid of signal at the exposure times analyzed (data not shown). Magnification 60X. Scale bar, 5 µm.

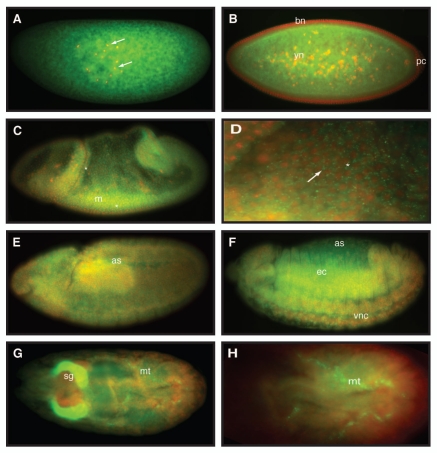

To determine the expression of dAven during Drosophila development, we synthesized an RNA-digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probe corresponding to an anti-sense sequence to the dAven mRNA and performed in situ hybridization in fixed embryos from all stages. As seen in Figure 3, we detected dAven mRNA throughout embryonic development. The transcript appears to be maternally loaded and distributed ubiquitously in the early embryo (Fig. 3A). At stage 5 of development, during cellularization, dAven is found in the area of the yolk and the yolk nuclei, and it is absent from the pole cells and the blastoderm nuclei (Fig. 3B). By stage 7, during gastrulation, the transcript can be found in small cytoplasmic foci (Fig. 3D, white arrow). We also detect new zygotic transcription in cells of the mesoderm and blastoderm in gastrulating embryos (Fig. 3C and Fig. 3D, asterisks). By stage 9 and up to stage 13 of development, dAven mRNA is everywhere in the embryo (Fig. 3E and Fig. 3F). At late stages, dAven is expressed ubiquitously at low levels and enriched at the salivary glands, the malpighian tubules (Fig. 3G) and the developing tracheal system (not shown). Based on the modENCODE RNA-seq expression database (www.flybase.org), dAven is also expressed moderately through larval, pupal and adult stages; in adults, dAven is moderately expressed in the eye, thorax, abdominal ganglion and ovary. Overall expression is higher in adult females relative to males. We also detected the expression of dAven in Drosophila S2 cells by RT-PCR (not shown).

Figure 3.

Embryonic expression of dAven. High resolution in situ hybridization of Drosophila embryos at various stages using an RNA-DIG labeled probe encoding an anti-sense sequence of dAven mRNA. (A) Early Drosophila embryo showing dividing nuclei (stained with DAPI and pseudo-colored in red, and indicated by arrows) and maternal dAven mRNA throughout the embryo (green). (B) Stage 5 embryo showing dAven mRNA enriched at the yolk and the yolk nuclei area (yn) and absent from the pole cells (pc) and the blastoderm nuclei (bn). (C) Embryo during gastrulation with ubiquitous distribution of dAven mRNA, including a mild enrichment at the mesoderm (m) and some zygotic transcription (asterisks). (D) Higher magnification image from the same embryo as (C) showing dAven mRNA localizing to cytoplasmic foci (white arrow) outside the nuclei (red) of cells. Zygotic transcription is seen as green dots inside the nuclei (asterisks). (E) Stage 9 embryo with dAven expression throughout the embryo, including the amnioserosa (as). (F) Stage 13 embryo showing ubiquitous dAven expression, including the ventral nerve cord (vnc), the ectoderm (ec) and the amnioserosa (as). (G) and (H) Stage 16 embryo showing dAven expression at the salivary glands (sg) and the malpighian tubules (mt); (H) is a higher magnification image of (G). In all the panels, anterior is to the right and ventral is down.

Knockdown of dAven in fat cells results in pupal lethality, abnormal chromosome morphology and increased levels of a mitosis marker.

To examine the role of dAven in vivo, we analyzed the loss-of-function phenotype of dAven. Since no CG15727/dAven mutant alleles or nearby transposable element insertions are available, we employed the UAS/Gal4 system in combination with the RNAi technique to knockdown dAven. A UAS-dAvenRNAi transgenic line (VDRC transformant #19577), which can express a hairpin sequence of 341 nucleotides that target the dAven transcript, was obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC; www.vdrc.at). The transcription of this hairpin is inducible by the yeast transcription factor Gal4, and can thus be regulated in a tissue- and time-specific manner using appropriate driver lines. Ubiquitous expression of UAS-dAvenRNAi driven by either daughterless-Gal4 or Act5c-Gal4 resulted in larval lethality at 29°C and pupal lethality at 25°C, in agreement with the known effect of temperature on the strength of UAS/Gal4-induced expression.38

To further investigate the role of dAven during development, we crossed UAS-dAvenRNAi to a panel of Gal4 drivers with known expression patterns. Induction of dAvenRNAi in a tissue-specific fashion in the eye by GMR-Gal4, wing by patched-Gal4, and neurons by elav-Gal4, resulted in viable flies with no apparent phenotype. Interestingly, we found that dAvenRNAi induced by the fat body-specific Gal4 drivers, CG-Gal4 or FB-Gal4, resulted in pupal lethality at 29°C, recapitulating to some extent the lethal phenotype observed with ubiquitous dAvenRNAi expression. These results suggest that dAven plays an important role in fat body development.

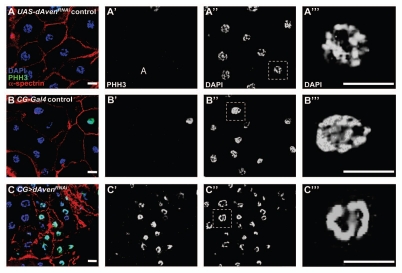

Female CG>dAvenRNAi animals, which were viable at 25°C, were chosen for further studies. Although the overall body size of these animals was not obviously different from controls, they appeared to have smaller ovaries and increased fat body tissue mass (data not shown). Analysis of abdominal fat tissue from CG>dAvenRNAi flies revealed smaller fat cells than those of normal control flies (Fig. 4). In addition, CG>dAvenRNAi fat cells displayed highly condensed DNA morphology compared to controls, and this phenotype was fully penetrant (Fig. 4). Because highly condensed DNA is normally associated with phosphorylated histone H3 (PHH3) in mitotic cells, we labeled control and CG>dAvenRNAi fat cells with antibodies against PHH3. Although precise quantification was precluded by difficulties with antibody penetration, we observed a markedly elevated number of PHH3-positive fat cells in CG>dAvenRNAi animals compared to controls (Fig. 4A′–C′), suggesting that these cells are arrested in a mitosislike state.

Figure 4.

dAven knockdown by RNAi in Drosophila fat cells leads to smaller cells with PHH3-positive, highly condensed DNA. (A–C) UAS-AvenRNAi control (A), CG-Gal4 control (B), and CG>UAS-AvenRNAi (C) fat cells were labeled with DAPI (blue), PHH3 (green), and α-spectrin (red). PHH3 and DAPI are shown in (A′–C′) and (A″–C″), respectively. Magnified DAPI-stained fat cell nuclei from (A″–C″, dashed box) shown in (A‴–C‴). Scale bars, 10 µm.

Expression of dAven in Xenopus egg extracts results in G2/M arrest.

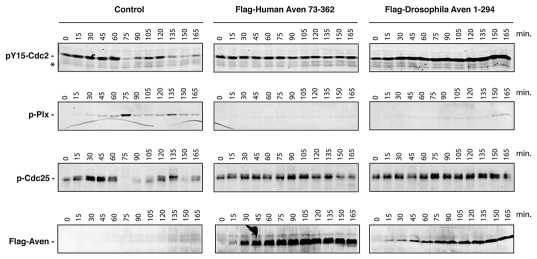

Cycling Xenopus egg extracts, which oscillate between S and M phases of the cell cycle,39 provide an excellent model system to study cell cycle progression and the DNA-damage response.40–42 We have recently shown that addition to these extracts of excess mRNA encoding either full-length or a truncated form of the human Aven protein lacking the first 72 amino acids (huAven and huAven ΔN72, respectively) results in G2/M arrest.36 To test the ability of dAven to modulate cell cycle progression in this system, we added mRNA coding for dAven to cycling Xenopus egg extracts and assessed markers of mitosis. Entry of extracts into mitosis is marked by (1) phosphorylation and activation of the polo-like kinase Plx1, (2) dephosphorylation of Cdc25 at S287 leading to its activation, and (3) dephosphorylation of Cdc2 at Y15,43,44 resulting in Cyclin B/Cdc2 complex activation.45–47 As shown in Figure 5, extracts expressing huAven ΔN72 displayed a significant delay in mitotic entry when compared to controls, in accordance with previously reported data (Fig. 5, center panels).36,37 This was evidenced by the absence of Plx1 phosphorylation or Cdc25 and Cdc2 dephosphorylation in Aven-supplemented extracts, all of which occurred on schedule in control extracts (i.e. at approximately 75 minutes after progesterone addition and then again at approximately 135–150 minutes; Fig. 5, left panel). Remarkably, extracts expressing dAven showed delayed mitotic entry to levels comparable to those seen in human Aven-expressing extracts (Fig. 5, right panels). Expression of human and Drosophila Aven proteins in the extracts was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 5, lower panels).

Figure 5.

The dAven protein effectively blocks mitotic entry in Xenopus egg extracts. Control buffer (control) or mRNA-encoding either Flag-tagged human Aven (Flag-Human Aven 73-362) or Flag-tagged dAven (Flag-Drosophila Aven 1-294) were added to cycling Xenopus egg extracts to drive protein expression. Aliquots of extracts were then taken at the indicated times and immunoblotted with anti-phospho Tyr15-Cdc2 (pY15-Cdc2, upper panels), anti-phospho polo-like kinase-1 (pPlx, middle panels), anti-phospho Cdc25 (pCdc25, lower panels) and anti-Flag epitope (bottom panels) antibodies. (*) indicates a non-specific band detected by the anti-phospho Tyr15-Cdc2 that serves as loading control. Data shown are representative results of at least three replicates.

Discussion

In this study we identify dAven, a Drosophila melanogaster ORF with sequence and functional similarities to the cell cycle regulator Aven. The predicted dAven protein displays a high degree of conservation relative to Aven proteins from several vertebrate species, in particular at specific domains that are highly conserved across various organisms. The dAven gene encodes a 294-amino-acid protein. Immunoblots of transiently transfected S2R+ cells expressing HA-tagged dAven detected a polypeptide of ∼45 kDa, even though the predicted molecular weight of dAven is 31.83 kDa (33.05 kDa including the HA-tag in our construct). This discrepancy between predicted and observed molecular weight is reminiscent of human Aven, which has a predicted molecular weight of 38.6 kDa but migrates in SDS-PAGE with an apparent molecular weight of 55 kDa.48 Immunofluorescence experiments showed that dAven is mainly cytosolic, with a small fraction of the protein localizing to the nucleus; this is also similar to the reported localization of human Aven.37,48

The Aven protein was identified by Chau et al. in a yeast two-hybrid screen for Bcl-xL interacting molecules, and shown to associate with Apaf-1.48 Aven was initially described as an anti-apoptotic factor that can regulate apoptosome formation48 and only recently it was reported to have a cell cycle regulatory function.36 Based on the initial report, we tested whether dAven associated with the Drosophila Apaf-1 ortholog Dapaf-1/Dark/HAC-149–51 and the fly Bcl-2 family members Buffy52 and Drob1/Dborg1/Debcl,53–55 but could not detect any association by co-immunoprecipitation assays (data not shown). Knockdown of dAven in fat tissue apparently did not result in enhanced cell death, judging by the increase in fat body mass observed in CG>dAvenRNAi animals (although these cells were smaller in size; see below). Therefore, these initial experiments did not provide any direct evidence for an anti-apoptotic function of dAven in Drosophila. However, it remains possible that the protein plays a role in cell death under certain physiological paradigms. The activity of Drob1/Dborg1/Debcl in the developing eye, for example, is very subtle during normal develoment but is dramatically enhanced during DNA damage, when it becomes readily visible.55

Aven modulates cell cycle progression at the G2/M transition via its association with and regulation of ATM. Checkpoint pathways activated by PIKKs have been shown to play important roles in development, likely mediating protection against DNA damage arising during normal cell proliferation and differentiation. In humans, loss of ATM function causes an inherited disease called ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T), whose symptoms include progressive neurodegeneration, chromosomal instability and pre-disposition to certain types of cancers.56,57 Mutations in ATR are associated with Seckel syndrome, a disorder characterized by growth retardation and severe microcephaly.58,59 While ATM knock out mice display a syndrome similar to that of A-T patients,60–64 ATR knock out mice show pre-gastrulation lethality.65,66 Therefore, ATM and ATR play distinct roles during normal development in mammals. Knock out of the Aven gene in C57BL/6 mice results in embryonic lethality (Martin Zörnig, Chemotherapeutisches Forschungsinstitut Georg-Speyer-Haus, Frankfurt, Germany, personal communication), indicating that Aven performs an essential function in mammalian development. Whether the role of Aven during development is related to its association with ATM and/or whether Aven plays any role in ATR-mediated signaling pathways is not known.

In Drosophila, Tefu/dATM is essential for normal adult development, with dATM mutant flies displaying pupal lethality. dATM mutant embryos and tissues show chromosomal instability, spontaneous telomere fusions, inappropriate p53-dependent apoptosis and mitotic defects.19,20,26 In contrast, mei-41/dATR mutant flies are fully viable in the absence of DNA damage.21,67 Since no dAven mutant alleles or nearby transposable element insertions are available, we analyzed dAven loss of function through RNAi-mediated gene knockdown. Ubiquitous expression of dAvenRNAi induced by daughterless-Gal4 and actin-Gal4 drivers resulted in pupal lethality at 25°C, indicating that, similarly to dATM, dAven is an essential gene in flies. Remarkably, knockdown of dAven by RNAi specifically in the fat body, a metabolically active organ analogous to mammalian adipose tissue and liver,68 also resulted in pupal lethality at 29°C. Although CG>dAvenRNAi animals were viable at 25°C, they displayed fat cells that were smaller than controls and scored positive for PHH3, a marker of mitotic chromosomes. Fat cells are polyploid and do not divide mitotically in adult flies;69 therefore, the increase of PHH3-positive cells in CG>dAvenRNAi flies is consistent with a developmental fat body defect resulting in an arrest of endoreplicating fat cells in a mitosis-like state. To some extent, this is reminiscent of the mitosis-like arrest of polyploid nurse cells in morula/APC2 mutants, in which cyclin B accumulates abnormally in nurse cells during oogenesis.70,71

Given the larger fat body mass observed and the smaller size of fat cells, it is reasonable to infer that the fat body of CG>dAvenRNAi animals contains an increased number of fat cells. This is also consistent with the fact that we observe more CG>dAvenRNAi fat cells per field relative to controls (approximately a two- to three-fold difference). This increase in cell numbers suggests that knockdown of dAven in adult fat cell precursors leads to a higher number of mitotic divisions during development, prior to their mitosis-like arrest. A role for dAven in regulating mitosis is indicated by experiments performed in Xenopus egg extracts, where ectopically expressed dAven was able to block G2/M transition to levels comparable to human Aven protein. Alternatively, the increase in cell numbers and fat body mass observed in CG>dAvenRNAi adults could be a consequence of larval fat cells that failed to die by programmed cell death in the dAven knockdown. Future experiments will be aimed at dissecting out the role of dAven in different types of cell cycles and at different developmental stages.

Despite the differences in their role during normal development in mammals, ATM and ATR appear to function in an interdependent fashion in response to DNA damage.13 For instance, upon ionizing radiation (IR) ATM is crucial to initiate G2 arrest72 whereas ATR is critical to maintain it.12 Aven plays an important role in cell cycle arrest during DNA damage. In human cells, ATM activation in response to DSBs is significantly reduced by RNAi-mediated knockdown of Aven,36 whereas in Xenopus egg extracts immunodepletion of endogenous xAven allows delayed entry into mitosis even in the face of checkpoint activation induced by genotoxic stress.36 In D. melanogaster, dATM and dATR have temporally distinct roles in G2 arrest after IR. While dATM is involved in an early premitotic checkpoint response to IR, mei-41 plays a major role in a late G2/M checkpoint response.19–21,23,24,67 Although UAS-dAvenRNAi crosses with a panel of tissue-specific Gal4 drivers resulted in viable flies with no apparent phenotype, indicating that dAven was dispensable for normal development of these organs, it is not known whether development under genotoxic stress could be affected in the absence of dAven. We recently reported that Aven is phosphorylated at residues S135 and S308 upon ATM activation.36 Interestingly, dAven has a putative ATM phosphorylation site at residue T254; whether this site is phosphorylated by a PIKK in the presence of DNA damage should be investigated.

In summary, we report the identification of dAven, a Drosophila ortholog of Aven. Experiments utilizing RNAi knockdown in Drosophila fat cells and protein overexpression in Xenopus egg extracts indicate that dAven significantly affects cell cycle progression, suggesting that the cell cycle regulatory function of Aven is conserved in flies. Thus, it will now be important to determine whether dAven uses a similar mechanism to modulate the cell cycle as its vertebrate counterparts. Future experiments should test whether dAven plays a developmental role under stress, in particular genotoxic stress. To answer these questions, it will be critical to generate and characterize mutant alleles of dAven. In humans, overexpression of Aven is associated with poor prognosis in patients with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia,73,74 and altered intracellular Aven distribution has been associated with infiltrating ductal carcinoma and papillary carcinoma breast cancer subtypes.75 Drosophila could be an excellent model for studying the function of Aven and identifying cellular factors that influence its activity, revealing information that may be relevant to human disease.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction.

A full-length cDNA for CG15727 (RE13534) was obtained from the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (DGRC) (https://dgrc.cgb.indiana.edu/). To generate an N-terminally HA-tagged dAven gene, we used this construct as a template in nested PCR amplification reactions using Turbo Pfu polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Digested PCR products, coding for HA-dAven, were then ligated into EcoRI- and XbaI-digested pMT/V5-His B vectors (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), downstream of the metallothionein (MT) promoter. For experiments in Xenopus extracts, the RE13534 construct was PCR amplified with primers that generated an N-terminally Flag-tagged dAven gene flanked by BamHI sites. The resulting PCR product was then subcloned into pSP64T plasmid,36 generating pSP64T-Flag-dAven. The orientation of all constructs and the accuracy of their sequences were confirmed by restriction mapping as well as nucleotide sequencing.

Cell culture and transfections.

S2R+ cells were a generous gift from Dr. Duojia Pan (Johns Hopkins University). Cells were maintained at 25°C in Schneider's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), glutamax, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 10U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For transient expression of dAven protein, cells were cultured in 6-well plates and 0.4 µg of purified plasmids coding for the indicated pMT/V5-His-derived constructs were transfected into 105 cells (one well per sample) using Effectene reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Twenty-four hours after transfection cells were added 0.7 mM of CuSO4 to induce gene expression from the metallothionein promoter. A day later, cells were processed for fractionation or immunofluorescence experiments.

Western blot analysis.

S2R+ cells were lyzed in isotonic lysis buffer [142.5 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), and 1 mM EGTA (pH 8.0)] with 0.3% NP-40, as described.48 For immunobloting, 20 µg of total cellular protein were electrophoresed per lane in NuPage Tris-acetate gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membranes were then probed with primary antibodies specific for HA (Y-11, Santa Cruz). For Xenopus experiments extracts were probed with anti-Flag-M2 (Sigma), pPlx1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), pY15-cdc2 (Cell Signaling Technology), and pCdc25 287 (Cell Signaling Technology). Primary antibodies were detected with either goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin coupled to horseradish peroxidase (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and signals were detected using chemiluminescent substrates (Pierce). Western blot signals were quantified by densitometry using ImageQuant software version 5.2.

Fluorescence microscopy.

To visualize the intracellular distribution of dAven, S2R+ cells were grown on glass coverslips and transiently transfected as described above. Twenty-four hours after transfection, 0.7 mM of CuSO4 were added to cells to induce gene expression from the pMT/V5-His constructs. A day later, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 15 minutes at room temperature with 4% freshly prepared paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were then washed with PBS and permeabilized for 1 minute with ice-cold acetone followed by additional PBS washes. Immunofluorescence assays were performed by incubating the samples with anti-HA Y-11 antibody (Santa Cruz) at a 1:500 dilution in PBS, followed by anti-rabbit conjugated to fluorescein secondary antibody (BD Biosciences) diluted at 1:100 in PBS. Coverslips were then mounted in DAPI-containing Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) on microscope slides. Samples were analyzed with a Zeiss Axio Imager. Z1 microscope, equipped with 60x/NA 1.40 optics and Apotome apparatus, coupled to a computer driven Zeiss AxioCAM digital camera (MRm), using Zeiss Axio Vision (4.4) software.

For experiments using fly tissue, adult abdomens with attached fat cells were fixed and stained with 4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and antibodies as described for ovarian tissue.76 Antibodies used were: mouse α-spectrin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 1:50), rabbit anti-phosphohistone H3 (PHH3) (Upstate Biotechnology; 1:250), Alexa 488- and 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse or -rabbit secondaries (Molecular Probes; 1:400). After immunostaining, fat cells were manually scraped from abdominal exoskeleton, mounted in Vectashield (Vector Labs), and analyzed using an LSM 700 confocal microscope.

RNA in situ hybridization.

Localization of dAven mRNA in Drosophila embryos was performed as previously described,77 and the results obtained constitute part of a large scale effort to generate the Fly-FISH database (www.utoronto.ca/krause). Briefly, embryos were fixed in 4% PFA and treated with proteinase K. A digoxigenin (DIG)-11-UTP-labeled antisense RNA probe for dAven was synthesized through in vitro transcription of a dAven cDNA template via the T3 promoter (Roche, Cat. No. 11209256910). The probe was then incubated with the fixed embryos for 12 hours at 56°C, followed by extensive washes. Next, a Biotin-conjugated anti-DIG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., Cat. No. 200-062-156) was added to bind the hybridized probe, followed by washes and addition of Streptavidin-HRP conjugates (Molecular Probes, Cat. No. S911). The embryos were then stained with Cy3 Tyramide conjugates (Molecular Probes; Cat. No. T-20932) to detect specific RNA localization signals via HRP-mediated Tyramide signal amplification (shown pseudo-colored in green) (Molecular Probes, Cat. No. S911). Nuclei were visualized by DAPI counter-stain (shown pseudo-colored in red).

Preparation of cycling Xenopus egg extracts and RNA synthesis.

Xenopus cycling extracts were prepared as described previously.78 For experiments involving mRNA addition to extracts, pSP64T-Flag-ΔN72-huAven36 and Flag-dAven constructs were linearized with BamHI, and mRNAs produced using the Stratagene's mCAP RNA-capping kit following manufacturer's instructions.

Fly Strains and Genetics.

Fly stocks were maintained at 22–25°C on standard cornmeal medium. yw is a wild-type control. UAS-AvenRNAi was obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (stockcenter.vdrc.at/control/main) (Transformant #19577). This line (subsequently referred to as dAvenRNAi) expresses in a Gal4-inducible fashion a hairpin sequence of 341 nucleotides to target the dAven transcript (sequence region: ACCGCAACGG AACAGGGACA TGCTGGACAC CCTGCCCAGC GACACCGACG ATGTGGAGCA ATTGGGCCTG GATGGTGCAC CCATCGATGA GAATGCCCGT GCCCAGTTAC GAGCTGGCGA TTTCCAGCAG CTGGCCCAGT TTCCCAGCCT CGGTGGCGGC CACTTCACCT TTGGGTCAGA GCGCGAATGG GCCAACGTGG CCGAGGGCCA GACCAAGCTA CACACCAAGG CTGCCAGTGC TTACTTCACC CTGAACCTCA CCCGCCTAAA TGTGGGTCTG CAAACGATTC CGTTATACAA GCGTATGGAT TATCCGGCGT CTTTGTTCAC CCGCGCTCAG A). CG-Gal4 have been previously discussed79,80. Elav-Gal4, GMR-Gal4, patched-Gal4 and actin-Gal4 stocks are described in Flybase (www.flybase.org) and were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN). Gal4 and UAS flies were crossed and allowed to lay eggs at 25°C. Subsequently eggs were developed either at 25°C or 29°C.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Fundacion INFANT (PI), R01 GM069875 (DDB), and Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH (SZ). LL designed and performed experiments in Figure 4 under the guidance of DDB. The authors would like to thank Sheryl Southard and Mark Van Doren from Johns Hopkins University for their help with some experiments performed during the course of this project.

Abbreviations

- ORF

open reading frame

- ATM

ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- ATR

ATM and Rad 3-related

- PIKKs

phosphoinositide 3-kinase related kinases

- DSBs

double-strand breaks

- PHH3

phosphorylated histone H3

- RNAi

RNA interference

References

- 1.Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: Safeguarding genome integrity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:155–168. doi: 10.1038/nrc1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kacmaz K, Linn S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elledge SJ. Cell cycle checkpoints: Preventing an identity crisis. Science. 1996;274:1664–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinert T. DNA damage and checkpoint pathways: Molecular anatomy and interactions with repair. Cell. 1998;94:555–558. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke PR, Allan LA. Cell-cycle control in the face of damage—a matter of life or death. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canman CE, Lim DS. The role of ATM in DNA damage responses and cancer. Oncogene. 1998;17:3301–3308. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cliby WA, Roberts CJ, Cimprich KA, Stringer CM, Lamb JR, Schreiber SL, et al. Overexpression of a kinase-inactive ATR protein causes sensitivity to DNAdamaging agents and defects in cell cycle checkpoints. EMBO J. 1998;17:159–169. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright JA, Keegan KS, Herendeen DR, Bentley NJ, Carr AM, Hoekstra MF, et al. Protein kinase mutants of human ATR increase sensitivity to UV and ionizing radiation and abrogate cell cycle checkpoint control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7445–7450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unsal-Kacmaz K, Makhov AM, Griffith JD, Sancar A. Preferential binding of ATR protein to UV-damaged DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6673–6678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102167799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das KC, Dashnamoorthy R. Hyperoxia activates the ATR-Chk1 pathway and phosphorylates p53 at multiple sites. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L87–L97. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00203.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, Khadpe J, Hu B, Iliakis G, Wang Y. An overactivated ATR/CHK1 pathway is responsible for the prolonged G2 accumulation in irradiated AT cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30869–30874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301876200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown EJ, Baltimore D. Essential and dispensable roles of ATR in cell cycle arrest and genome maintenance. Genes Dev. 2003;17:615–628. doi: 10.1101/gad.1067403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith J, Tho LM, Xu N, Gillespie DA. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;108:73–112. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380888-2.00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuoka S, Rotman G, Ogawa A, Shiloh Y, Tamai K, Elledge SJ. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated phosphorylates Chk2 in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10389–10394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190030497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melchionna R, Chen XB, Blasina A, McGowan CH. Threonine 68 is required for radiation-induced phosphorylation and activation of Cds1. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:762–765. doi: 10.1038/35036406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuoka S, Huang M, Elledge SJ. Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science. 1998;282:1893–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chehab NH, Malikzay A, Appel M, Halazonetis TD. Chk2/hCds1 functions as a DNA damage checkpoint in G(1) by stabilizing p53. Genes Dev. 2000;14:278–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roos WP, Kaina B. DNA damage-induced cell death by apoptosis. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:440–450. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song YH, Mirey G, Betson M, Haber DA, Settleman J. The Drosophila ATM ortholog, dATM, mediates the response to ionizing radiation and to spontaneous DNA damage during development. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1354–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva E, Tiong S, Pedersen M, Homola E, Royou A, Fasulo B, et al. ATM is required for telomere maintenance and chromosome stability during Drosophila development. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1341–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hari KL, Santerre A, Sekelsky JJ, McKim KS, Boyd JB, Hawley RS. The mei-41 gene of D. melanogaster is a structural and functional homolog of the human ataxia telangiectasia gene. Cell. 1995;82:815–821. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sibon OC, Laurencon A, Hawley R, Theurkauf WE. The Drosophila ATM homologue Mei-41 has an essential checkpoint function at the midblastula transition. Curr Biol. 1999;9:302–312. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brodsky MH, Sekelsky JJ, Tsang G, Hawley RS, Rubin GM. mus304 encodes a novel DNA damage checkpoint protein required during Drosophila development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:666–678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaklevic BR, Su TT. Relative contribution of DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoints, and cell death to survival after DNA damage in Drosophila larvae. Curr Biol. 2004;14:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bi X, Gong M, Srikanta D, Rong YS. Drosophila ATM and Mre11 are essential for the G2/M checkpoint induced by low-dose irradiation. Genetics. 2005;171:845–847. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.047720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bi X, Wei SC, Rong YS. Telomere protection without a telomerase; the role of ATM and Mre11 in Drosophila telomere maintenance. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1348–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bi X, Srikanta D, Fanti L, Pimpinelli S, Badugu R, Kellum R, et al. Drosophila ATM and ATR checkpoint kinases control partially redundant pathways for telomere maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15167–15172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504981102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutkowski R, Hofmann K, Gartner A. Phylogeny and function of the invertebrate p53 superfamily. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001131. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oikemus SR, McGinnis N, Queiroz-Machado J, Tukachinsky H, Takada S, Sunkel CE, et al. Drosophila atm/telomere fusion is required for telomeric localization of HP1 and telomere position effect. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1850–1861. doi: 10.1101/gad.1202504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu J, Xin S, Du W. Drosophila Chk2 is required for DNA damage-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:394–398. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brodsky MH, Weinert BT, Tsang G, Rong YS, McGinnis NM, Golic KG, et al. Drosophila melanogaster MNK/Chk2 and p53 regulate multiple DNA repair and apoptotic pathways following DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1219–1231. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1219-1231.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Vries HI, Uyetake L, Lemstra W, Brunsting JF, Su TT, Kampinga HH, et al. Grp/DChk1 is required for G2-M checkpoint activation in Drosophila S2 cells, whereas Dmnk/DChk2 is dispensable. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1833–1842. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson C, Carney GE, Taylor BJ, White K. reaper is required for neuroblast apoptosis during Drosophila development. Development. 2002;129:1467–1476. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JH, Lee E, Park J, Kim E, Kim J, Chung J. In vivo p53 function is indispensable for DNA damage-induced apoptotic signaling in Drosophila. FEBS Lett. 2003;550:5–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00771-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sogame N, Kim M, Abrams JM. Drosophila p53 preserves genomic stability by regulating cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4696–4701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0736384100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo JY, Yamada A, Kajino T, Wu JQ, Tang W, Freel CD, et al. Aven-dependent activation of ATM following DNA damage. Curr Biol. 2008;18:933–942. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esmaili AM, Johnson EL, Thaivalappil SS, Kuhn HM, Kornbluth S, Irusta PM. Regulation of the ATM-activator protein Aven by CRM1-dependent nuclear export. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3913–3920. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.19.13138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duffy JB. GAL4 system in Drosophila: A fly geneticist's Swiss army knife. Genesis. 2002;34:1–15. doi: 10.1002/gene.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray AW, Kirschner MW. Cyclin synthesis drives the early embryonic cell cycle. Nature. 1989;339:275–280. doi: 10.1038/339275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hutchison CJ, Cox R, Drepaul RS, Gomperts M, Ford CC. Periodic DNA synthesis in cell-free extracts of Xenopus eggs. EMBO J. 1987;6:2003–2010. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hutchison CJ, Cox R, Ford CC. The control of DNA replication in a cell-free extract that recapitulates a basic cell cycle in vitro. Development. 1988;103:553–566. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smythe C, Newport JW. Systems for the study of nuclear assembly, DNA replication, and nuclear breakdown in Xenopus laevis egg extracts. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;35:449–468. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60583-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perdiguero E, Nebreda AR. Regulation of Cdc25C activity during the meiotic G2/M transition. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:733–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Margolis SS, Kornbluth S. When the checkpoints have gone: Insights into Cdc25 functional activation. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:425–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo Z, Dunphy WG. Response of Xenopus Cds1 in cell-free extracts to DNA templates with double-stranded ends. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1535–1546. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoo HY, Shevchenko A, Dunphy WG. Mcm2 is a direct substrate of ATM and ATR during DNA damage and DNA replication checkpoint responses. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53353–53364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumagai A, Dunphy WG. Claspin, a novel protein required for the activation of Chk1 during a DNA replication checkpoint response in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol Cell. 2000;6:839–849. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chau BN, Cheng EH, Kerr DA, Hardwick JM. Aven, a novel inhibitor of caspase activation, binds Bcl-xL and Apaf-1. Mol Cell. 2000;6:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez A, Oliver H, Zou H, Chen P, Wang X, Abrams JM. Dark is a Drosophila homologue of Apaf-1/CED-4 and functions in an evolutionarily conserved death pathway. Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:272–279. doi: 10.1038/12984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou L, Song Z, Tittel J, Steller H. HAC-1, a Drosophila homolog of APAF-1 and CED-4 functions in developmental and radiation-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell. 1999;4:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kanuka H, Sawamoto K, Inohara N, Matsuno K, Okano H, Miura M. Control of the cell death pathway by Dapaf-1, a Drosophila Apaf-1/CED-4-related caspase activator. Mol Cell. 1999;4:757–769. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80386-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quinn L, Coombe M, Mills K, Daish T, Colussi P, Kumar S, et al. Buffy, a Drosophila Bcl-2 protein, has anti-apoptotic and cell cycle inhibitory functions. EMBO J. 2003;22:3568–3579. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Igaki T, Kanuka H, Inohara N, Sawamoto K, Nunez G, Okano H, et al. Drob-1, a Drosophila member of the Bcl-2/CED-9 family that promotes cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:662–667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Colussi PA, Quinn LM, Huang DC, Coombe M, Read SH, Richardson H, et al. Debcl, a proapoptotic Bcl-2 homologue, is a component of the Drosophila melanogaster cell death machinery. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:703–714. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brachmann CB, Jassim OW, Wachsmuth BD, Cagan RL. The Drosophila bcl-2 family member dBorg-1 functions in the apoptotic response to UV-irradiation. Curr Biol. 2000;10:547–550. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gatti RA, Becker-Catania S, Chun HH, Sun X, Mitui M, Lai CH, et al. The pathogenesis of ataxia-telangiectasia. Learning from a Rosetta Stone. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2001;20:87–108. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:20:1:87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyn MS. Ataxia-telangiectasia, cancer and the pathobiology of the ATM gene. Clin Genet. 1999;55:289–304. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.550501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lavin MF. Ataxia-telangiectasia: from a rare disorder to a paradigm for cell signalling and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:759–769. doi: 10.1038/nrm2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kerzendorfer C, O'Driscoll M. Human DNA damage response and repair deficiency syndromes: linking genomic instability and cell cycle checkpoint proficiency. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:1139–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barlow C, Hirotsune S, Paylor R, Liyanage M, Eckhaus M, Collins F, et al. Atm-deficient mice: a paradigm of ataxia telangiectasia. Cell. 1996;86:159–171. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barlow C, Liyanage M, Moens PB, Tarsounas M, Nagashima K, Brown K, et al. Atm deficiency results in severe meiotic disruption as early as leptonema of prophase I. Development. 1998;125:4007–4017. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.4007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herzog KH, Chong MJ, Kapsetaki M, Morgan JI, McKinnon PJ. Requirement for Atm in ionizing radiation-induced cell death in the developing central nervous system. Science. 1998;280:1089–1091. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu Y, Ashley T, Brainerd EE, Bronson RT, Meyn MS, Baltimore D. Targeted disruption of ATM leads to growth retardation, chromosomal fragmentation during meiosis, immune defects, and thymic lymphoma. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2411–2422. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Westphal CH, Rowan S, Schmaltz C, Elson A, Fisher DE, Leder P. atm and p53 cooperate in apoptosis and suppression of tumorigenesis, but not in resistance to acute radiation toxicity. Nat Genet. 1997;16:397–401. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Klein A, Muijtjens M, van Os R, Verhoeven Y, Smit B, Carr AM, et al. Targeted disruption of the cell-cycle checkpoint gene ATR leads to early embryonic lethality in mice. Curr Biol. 2000;10:479–482. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brown EJ, Baltimore D. ATR disruption leads to chromosomal fragmentation and early embryonic lethality. Genes Dev. 2000;14:397–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laurencon A, Purdy A, Sekelsky J, Hawley RS, Su TT. Phenotypic analysis of separation-of-function alleles of MEI-41, Drosophila ATM/ATR. Genetics. 2003;164:589–601. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gutierrez E, Wiggins D, Fielding B, Gould AP. Specialized hepatocyte-like cells regulate Drosophila lipid metabolism. Nature. 2007;445:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nature05382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Y, Liu H, Liu S, Wang S, Jiang RJ, Li S. Hormonal and nutritional regulation of insect fat body development and function. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2009;71:16–30. doi: 10.1002/arch.20290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reed BH, Orr-Weaver TL. The Drosophila gene morula inhibits mitotic functions in the endo cell cycle and the mitotic cell cycle. Development. 1997;124:3543–3553. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kashevsky H, Wallace JA, Reed BH, Lai C, Hayashi-Hagihara A, Orr-Weaver TL. The anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome is required during development for modified cell cycles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11217–11222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172391099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu B, Kim ST, Lim DS, Kastan MB. Two molecularly distinct G(2)/M checkpoints are induced by ionizing irradiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1049–1059. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1049-1059.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paydas S, Tanriverdi K, Yavuz S, Disel U, Sahin B, Burgut R. Survivin and aven: two distinct antiapoptotic signals in acute leukemias. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1045–1050. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Choi J, Hwang YK, Sung KW, Kim DH, Yoo KH, Jung HL, et al. Aven overexpression: association with poor prognosis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2006;30:1019–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kutuk O, Temel SG, Tolunay S, Basaga H. Aven blocks DNA damage-induced apoptosis by stabilising Bcl-xL. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2494–2505. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hsu HJ, LaFever L, Drummond-Barbosa D. Diet controls normal and tumorous germline stem cells via insulin-dependent and -independent mechanisms in Drosophila. Developmental Biol. 2008;313:700–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lecuyer E, Yoshida H, Parthasarathy N, Alm C, Babak T, Cerovina T, et al. Global analysis of mRNA localization reveals a prominent role in organizing cellular architecture and function. Cell. 2007;131:174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Murray AW. Cell cycle extracts. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:581–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takata K, Yoshida H, Yamaguchi M, Sakaguchi K. Drosophila damaged DNA-binding protein 1 is an essential factor for development. Genetics. 2004;168:855–865. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.025965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gronke S, Beller M, Fellert S, Ramakrishnan H, Jackle H, Kuhnlein RP. Control of fat storage by a Drosophila PAT doamin protein. Curr Biol. 2003;13:603–606. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]