Primary microcephaly (MCPH), a rare autosomal recessive neurodevelopmental disorder, is characterized by reduced brain size and mental retardation.1 The reduced brain size is believed to result from asymmetric division of neuronal progenitor cells, causing reduced number of neurons.2 One of the six identified MCPH genes is MCPH3 which encodes cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5),3,4 regulatory subunit-associated protein 2 (CDK5RAP2).5 The CDK5RAP2 gene is composed of 38 exons (Fig. 1A) that encode a 1,893 amino acid residue protein, consisting of a microtubule (MT) binding domain (residues 59–133), two structural maintenance of chromosome (SMC) domains [one each in the N-(residues 137–470) and C-(residues 1,399–1,646) terminals], and a p35 interacting domain (residues 1,682–1,827; Fig. 1C). Previously, two distinct mutations, 243T→A and IVS26-15A→G, in the CDK5RAP2 gene have been reported in two northern Pakistani microcephaly pedigrees, providing clues for understanding the molecular mechanism by which CDK5RAP2 controls brain size.1 Pedigree 1 mutation (Y82X, mistakenly designated as S81X1) results in a truncated 81 amino acid peptide that is missing part of the MT binding domain, the two SMC domains and the p35 binding domain. In contrast, pedigree 2 mutation (R1334SfsX5, mistakenly designated as E385fsX41) generates a truncated 1,338 amino acid protein that is missing the C-terminal SMC domain and the p35-binding domain. Thus, it appears that deletion of both the C-terminal SMC domain and the p35-binding domain in CDK5RAP2 is sufficient to cause the development of MCPH3-associated primary microcephaly. Since CDK5RAP2 localizes in the centrosome, specifically, in the region of the pericentriolar material (PCM),5,6 it is not surprising that the previously generated mutant CDK5RAP2 mice exhibit defects in centriole engagement and cohesion.7 Interestingly, CDK5RAP2 has also been shown to stimulate microtubule nucleation by the gamma-tubulin ring complex,8 and functionally interacts with pericentrin,9 suggesting that CDK5RAP2 together with pericentrin influence centrosome cohesion through an indirect mechanism related to cytoskeletal dynamics.

Figure 1.

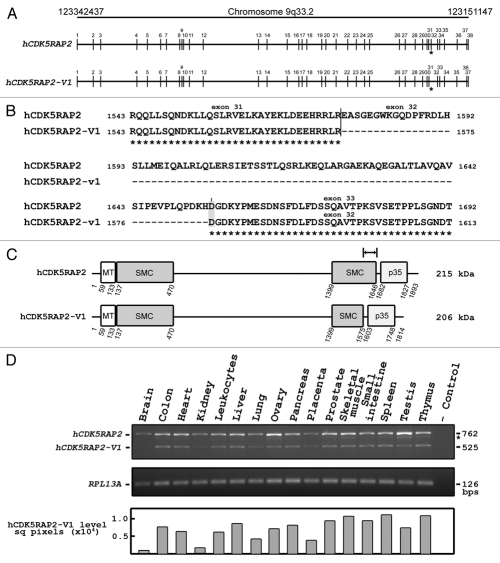

The human full length CDK5RAP2 (hCDK5RAP2) and its spliced variant form (hCDK5RAP2-V1). (A) Schematic diagram of human chromosome 9q33.2 minus strand from nucleotide 123151147 to nucleotide 123342437 [adapted from UCSC Genome Browser on Human Feb 2009 (GRCh37/hg19) Assembly]. Vertical bars with numbers indicate exons for hCDK5RAP2 and hCDK5RAP2-V1. Note that CDK5RAP2 exon 32 is missing in hCDK5RAP2-V1 (asterisk) due to alternative splicing. (B) Sequence alignment of hCDK5RAP2 with hCDK5RAP2-V1. Sequences were aligned by CLUSTAL 2.0.12 multiple sequence alignment software; amino acid numbers are indicated on either side. The identical sequences of hCDK5RAP2 and hCDK5RAP2-V1 are shown. The broken line corresponds to the missing amino acid sequence in hCDK5RAP2-V1. The codon (GAT) encoding aspartic acid (D, shaded in grey) for hCDK5RAP2 and hCDK5RAP2-V1 is generated from the combination of nucleotides (G-AT) between exon 32 and exon 33, and between exon 31 and exon 32, respectively. (C) Primary structure of hCDK5RAP2 and hCDK5RAP2-V1. hCDK5RAP2 encodes 1,893 amino acids (215 kDa) while hCDK5RAP2-V1 encodes 1,814 amino acids (206 kDa) lacking 79 amino acids from amino acid1,576 to amino acid1,654. hCDK5RAP2 (genbank accession no. NP_060719) and hCDK5RAP2-V1 (genbank accession no. NP_001011649) are shown. (D) Tissue distribution of hCDK5RAP2 and hCDK5RAP2-V1 transcripts by PCR using human cDNAs as template and the following primers: forward primer (TGG AAC GGC AAG GAT CTG AA) and reverse primer (TCA CTG CCT GGG AGG AAT CA). hCDK5RAP2 and hCDK5RAP2-V1 transcripts produce 762 bp and 525 bp PCR fragments. RPL13A was used as an internal control: forward primer (CCTG GAG GAG AAG AGG AAA GAG A) and reverse primer (TTG AGG ACC TCT GTG TAT TTG TCA A). No template was used for the negative control. Levels of hCDK5RAP2-V1 transcript were determined by densitometric analysis using the Image J software. Asterisk indicates a non-specific PCR product that was confirmed by sequence analysis.

In this report, we demonstrate the presence of a novel alternatively spliced variant form of hCDK5RAP2, hCDK5RAP2 variant 1 (hCDK5RAP2-V1) which lacks the 237 nucleotide residues of hCDK5RAP2 exon 32 (Fig. 1A and asterisk). The hCDK5RAP2-V1 was detected while examining the expression of hCDK5RAP2 in various human tissues by RT-PCR (Fig. 1D). Sequencing analysis of the smaller PCR product (525 bps) confirmed the existence of the hCDK5RAP2-V1. The hCDK5RAP2-V1 encodes 1,814 amino acids lacking 79 amino acids from amino acid1,576 to amino acid1,654. As indicated in Figure 1B, hCDK5RAP2-V1 is identical to hCDK5RAP2 except for the absence of exon 32 that spans part of the C-terminal SMC plus eight amino acid residues after the C-terminal SMC (Fig. 1C; indicated by I↔I). This finding indicates that CDK5RAP2 exists in at least two forms: full-length hCDK5RAP2 (1,893 amino acids; 215 kDa) and an alternatively spliced hCDK5RAP2-V1 (1,814 amino acids; 206 kDa). The existence of an alternatively spliced variant form of hCDK5RAP2 may suggest distinct physiological functions of these hCDK5RAP2 forms. Therefore, we further examined various human tissues for potential differences in expression of hCDK5RAP2 and hCDK5RAP2-V1 (Fig. 1D). We found that the hCDK5RAP2 mRNA transcript is predominantly and ubiquitously expressed in all tissues examined. However, we also found clear and considerable expression of hCDK5RAP2-V1 in most tissues, including the colon, heart, leukocytes, liver, ovary, pancreas, prostate, skeletal muscle, small intestine, spleen, testis and thymus but noted decreased expression in kidney, lung and placenta. Interestingly, expression of hCDK5RAP2-V1 in brain was barely detectable. Indeed, differential tissue distribution of hCDK5RAP2 and hCDK5RAP2-V1 suggests distinct roles in vivo. As interaction between hCDK5RAP2 and pericentrin is mediated through the C-terminal portion of hCDK5RAP2,9 it is possible that the lack of exon 32 results in a conformational change that prevents hCDK5RAP2-V1 interaction with pericentrin, supporting the notion that hCDK5RAP2-V1 may play a role distinct from hCDK5RAP2.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to K.Y.L., an Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Senior Scholar. J.L.R. is supported by a grant from NSERC.

References

- 1.Bond J, et al. Nat Genet. 2005;37:353–355. doi: 10.1038/ng1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox J, et al. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee KY, et al. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:951–958. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosales JL, et al. Bioessays. 2006;28:1023–1034. doi: 10.1002/bies.20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosales JL, et al. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:618–620. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.3.10597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graser S, et al. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4321–4331. doi: 10.1242/jcs.020248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrera JA, et al. Dev Cell. 2010;18:913–926. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi YK, et al. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1089–1095. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchman JJ, et al. Neuron. 2010;66:386–402. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]