Abstract

Objective To compare the efficacy of surgery with disc prosthesis versus non-surgical treatment for patients with chronic low back pain.

Design A prospective randomised multicentre study.

Setting Five university hospitals in Norway.

Participants 173 patients with a history of low back pain for at least one year, Oswestry disability index of at least 30 points, and degenerative changes in one or two lower lumbar spine levels (86 patients randomised to surgery). Patients were treated from April 2004 to September 2007.

Interventions Surgery with disc prosthesis or outpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation for 12-15 days.

Main outcome measures The primary outcome measure was the score on the Oswestry disability index after two years. Secondary outcome measures were low back pain, satisfaction with life (SF-36 and EuroQol EQ-5D), Hopkins symptom check list (HSCL-25), fear avoidance beliefs (FABQ), self efficacy beliefs for pain, work status, and patients’ satisfaction and drug use. A blinded independent observer evaluated scores on the back performance scale and Prolo scale at two year follow-up.

Results The study was powered to detect a difference of 10 points on the Oswestry disability index between the groups at two years. At two years there was a mean difference of −8.4 points (95% confidence interval −13.2 to −3.6) in favour of surgery. In the analysis of prespecified secondary outcomes, there were significant differences in favour of surgery for low back pain (mean difference −12.2, −21.3 to −3.1), patients’ satisfaction (63% (n=46) v 39% (n=26)), SF-36 physical component score (mean difference 5.8, 2.5 to 9.1), self efficacy for pain (mean difference 1.0, 0.2 to 1.9), and the Prolo scale (mean difference 0.9, 0.1 to 1.6). There were no significant differences in return to work, SF-36 mental component score, EQ-5D, fear avoidance beliefs, Hopkins symptom check list, drug use, and the back performance scale. One serious complication of leg amputation occurred during surgical revision of a polyethylene dislodgement. The drop-out rate was 20% (34) and the crossover rate was 6% (5).

Conclusions Surgical intervention with disc prosthesis for chronic low back pain resulted in a significantly greater improvement in the Oswestry score compared with rehabilitation, but this improvement did not clearly exceed the prespecified minimally important clinical difference between groups of 10 points, and the data are consistent with a wide range of differences between the groups, including values well below 10 points. The potential risks of surgery and the substantial amount of improvement experienced by a sizeable proportion of the rehabilitation group also have to be incorporated into overall decision making.

Trial registration NCT 00394732.

Introduction

Low back pain is common with a lifetime prevalence of about 59-84%.1 Although relatively few patients develop chronic low back pain with disability, it represents extensive individual, societal, and financial problems. In patients who have had longstanding or serious disabling low back pain in the previous 12 months, a third will improve and have less serious problems during the following year.2 Most patients who develop chronic low back pain, however, stay in this condition for years.

Fusion of assumed symptomatic segments in patients with chronic low back pain has been used widely, but randomised studies comparing fusion with non-surgical treatment indicate that a rehabilitation programme can be as effective as surgery. Four randomised studies have compared lumbar fusion with non-operative treatment.3 4 5 6 7 Fritzell et al found that fusion significantly reduced pain and disability compared with usual care.3 Brox et al and Fairbank et al compared fusion with a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme focusing on cognitive intervention and supervised exercise.4 5 6 7 They found similar improvement in pain and disability in the two intervention groups.

During the past 25 years, insertion of a disc prosthesis has become an option. In the four published randomised studies comparing disc prosthesis with fusion, the clinical outcome of disc prosthesis was at least equivalent to that of fusion.8 9 10 11 As surgical procedures should be evaluated against non-surgical methods,12 13 we compared the efficacy of disc prosthesis and a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme.

Methods

Study design

A multicentre study conducted at five university hospitals in Norway included patients with low back pain and degenerative discs. Patients were included in the period between April 2004 and May 2007 and were treated within three months after randomisation. They were randomised in blocks with a website hosted by the medical faculty. Allocation was concealed for all people involved in the trial. A coordinating secretary not involved in the treatment could access randomisation details on the internet. The patient and the treating unit were informed about the allocation shortly after randomisation. Randomisation was stratified by centre (the five university hospitals) and whether the patient had had previous surgery (microsurgical decompression) or not. Independent observers collected and entered data. Storage of data was allowed by the Norwegian data inspectorate.

Participants

Patients were referred from all health regions in Norway. They were recruited from local hospitals or primary care to their nearest university hospital as usual without any supplemental recruitment attempt. An orthopaedic surgeon and a specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation examined the patients before enrolment. All patients were informed about the procedures and told that neither of the treatment methods was documented as superior to the other. Eligible patients were aged 25-55 and had low back pain as the main symptom for at least a year, structured physiotherapy or chiropractic treatment for at least six months without sufficient effect, a score of at least 30 on the Oswestry disability index, and degenerative intervertebral disc changes in L4/L5 or L5/S1, or both. Degeneration had to be restricted to the two lower levels. We evaluated the following degenerative changes: at least 40% reduction of disc height,14 Modic changes type I or II, or both,15 high intensity zone in the disc,16 and morphological changes classified as changes in signal intensity in the disc of grade 3 or 4.17 The disc was classified as degenerative if the first criterion alone or at least two changes were found on magnetic resonance imaging. The discs were independently classified by two observers (orthopaedic surgeon/radiologist). When there was disagreement, a third observer classified the images and the outcome was decided by simple majority.

Degeneration of the facet joints was not an exclusion criterion, but symptoms of nerve root involvement were. Details of further inclusion and exclusion criteria, compliance with randomisation, and drop-outs are listed in the appendix 1 on bmj.com.

Study interventions

Rehabilitation—The rehabilitation was based on the treatment model described by Brox et al4 and consisted of a cognitive approach and supervised physical exercise. A team of physiotherapists and specialists in physical medicine and rehabilitation directed the multidisciplinary treatment. Other specialists, such as psychologists, nurses, social workers, etc, could complete the team. The intervention was standardised through three seminars and videos and lecture sessions for the treatment providers before the study. The intervention was organised as an outpatient treatment in groups at the involved university hospitals and lasted for about 60 hours over three to five weeks. The treatment consisted of lectures and individual discussions focusing on relevant topics (such as anatomy and the physiological aspects of the back, diagnostics, imaging, pain medicine, normal reactions, coping strategies, family and social life, and working conditions), daily workouts for increased physical capacity (endurance, strength, coordination, and specific training of the abdominal muscles and the lumbar multifidus muscles), and challenging patients’ thoughts about, and participation in, physical activities previously labelled as not recommended (such as lifting, jumping, vacuum cleaning, dancing, and ball games). Follow-up consultations were conducted at six weeks, three months, six months, and one year after the intervention. See appendix 2 on bmj.com for detailed description of the rehabilitation intervention.

Surgery—The surgical intervention consisted of replacement of the degenerative intervertebral lumbar disc with an artificial lumbar disc (ProDisc II, Synthes Spine). The ProDisc consists of three pieces: two metal endplates of cobalt chromium molybdenum alloy and a core (made from ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene) fixed to the inferior endplate after insertion. Surgeons used a Pfannenstiel or a para-median incision with a retroperitoneal approach. A nearly complete discectomy was performed with removal of the cartilaginous endplates and a sufficient release of the posterior longitudinal ligament to ensure disc space mobilisation. A fluoroscope was used to ensure that the prosthesis was placed in the midline and sufficiently towards the posterior edge of the vertebrae. All hospitals participating in the study used the same artificial lumbar disc device. One surgeon at each centre had main responsibility for the operation (five centres and five surgeons). Surgeons were required to have inserted at least six disc prostheses before performing surgery in the study. There were no major postoperative restrictions. Patients were not referred for postoperative physiotherapy, but at six weeks’ follow-up they could be referred for physiotherapy if required, emphasising general mobilisation and non-specific exercises.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was pain and disability measured with version 2.0 of the Oswestry disability index,18 translated into Norwegian and tested for psychometric properties by Grotle et al.19 (Scores range from 0 to 100, with lower score indicating less severe pain and disability.) Secondary outcomes included low back pain (measured with a visual analogue scale, ranging from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst pain imaginable)) and general health status assessed with SF-36 (scores range from 0 to 100, higher scores correspond to better health status)20 21 and EQ-5D (scores range from −0.59 to 1 (1 equals perfect health)).22 For psychological variables we included emotional distress (Hopkins symptom check list (HSCL-25), scores range from 1 to 4, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms) and the fear avoidance belief questionnaire (FABQ) for work and physical activity (scores range from 0 to 42 (work) and from 0 to 24 (physical), with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms).23 24 Self efficacy beliefs for pain were registered by a subscale of the arthritis self efficacy scale (scores range from 1 to 10 and are summarised and divided by 5; lower scores indicate uncertainty in managing the pain).25 Work status was evaluated as suggested by Fritzell et al.3 (See table A in appendix 3 on bmj.com.) We calculated a net back to work rate, subtracting patients who went back to work from patients who stopped working, satisfaction with the result of the treatment on a seven point Likert scale, and satisfaction with care on a five point Likert scale.26 Further daily consumption of drugs was registered. Patients attended for follow-up visits at six weeks, three and six months, and one and two years (the main end point of follow-up was at two years). At two years we sent a questionnaire including the most important outcome measures to 29 of the 34 patients who were lost to follow-up (see table B in appendix 3 on bmj.com).

At the two year follow-up, two independent observers blinded to treatment evaluated patients using the back performance scale (consists of five tests with a score ranging from 0 to 15, worst possible)27 and the Prolo scale (consists of functional and economic parts, which are summed to a worst score of 2 and a best score of 10).28 Patients were informed before this session not to reveal the treatment received, and had tape placed on their abdominal wall to hide the scarring from the operation. We also carried out a full health economic analysis, which will be reported elsewhere.

Statistical considerations

The trial was designed to have 80% power to detect a significant difference of at least 10 points in change in the mean Oswestry disability index score between the intervention groups at two year follow-up.5 Baseline standard deviation was estimated at 18.18 Considering these assumptions and adding 25% for a multicentre study design and 30% for possible drop-outs, we estimated we required 180 patients.

Planned analyses

The main statistical analysis was in the intention to treat population at one and two year follow-up. According to our protocol the analysis was performed with the assumption that patients who dropped out had no improvement after drop-out (last value carried forward). We also determined if different centres had different outcomes. We used χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test to analyse categorical variables and independent two sided t test or analysis of variance to analyse continuous variables. A significance level of 5% was used throughout. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 16.0. We did not adjust for significantly different baseline scores.

Unplanned analyses (analyses not recorded in the original protocol)

We conducted a per protocol analysis for the primary outcome variable (score on Oswestry disability index). Consistent with criteria from the Food and Drug Administration,8 we considered an individual change in score of at least 15 points from baseline to two year follow-up as a minimal important change. A deterioration of 6 points in the score was considered a “change for the worse.”29 We calculated the number needed to treat with confidence intervals.30 A mixed model analysis was used to evaluate the effect of each efficacy variable over time and between groups. In the mixed model patients were not excluded from the analysis of an efficacy variable if the variable was missing at some, but not all, time points after baseline. In the additional analysis (categorical or ordinal data at two year follow-up), missing data were not replaced. Significantly different baseline scores were not adjusted for in the longitudinal model. Each outcome variable was adjusted for the baseline values of the variable.

Results

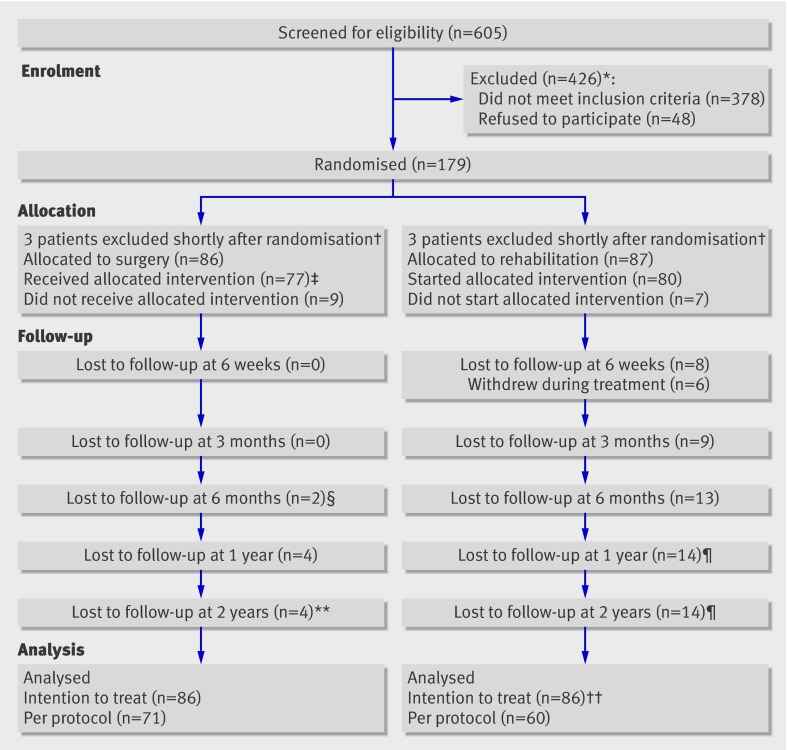

Of the 605 patients screened for eligibility, 173 were included in the study and treated between April 2004 and September 2007 (86 with surgery and 87 with rehabilitation) (fig 1). The drop-out rate from inclusion to two year follow-up was 20% (n=34) (15% (n=13) in the surgical arm and 24% (n=21) in the rehabilitation arm). Five patients (6%) crossed over from rehabilitation to surgery, but none crossed from surgery to rehabilitation. Of the 34 patients lost to follow-up, 26 answered a questionnaire two and a half to five years after treatment (see table B in appendix 3 on bmj.com).

Fig 1 Enrolment, randomisation, and follow-up of study patients, showing cumulative values at two years. *Not enough degenerative change to satisfy inclusion criteria (n=29), degenerative changes in more than two lower lumbar discs (n=80), Oswestry disability index score too low (n=88), did not want to undergo surgery (n=28), did not want to participate in rehabilitation (n=20), too much general pain (n=20), had previously been through similar training programme (n=26), and other reasons (n=135; deformity, psoriasis arthritis, language problems, coccygodynia, age, fracture, previous operation, tumour, spondylodiscitis, hip arthrosis). †Coronary heart disease and heart attack some days after randomisation (n=1); obvious exclusion criterion discovered some days after randomisation (n=50; earlier large abdominal operation (n=1), not enough degenerative change to satisfy inclusion criteria (n=2), degenerative changes in more than two lower lumbar discs (n=2). ‡One patient received one of two disc prostheses because of bleeding. §One patient with serious vascular complication underwent secondary leg amputation and was lost to follow-up. ¶One patient crossed over between 6 months and 1 year and five patients between 1 year and 2 years. Five patients underwent surgery with disc prosthesis and one patient with fusion. **Two patients underwent surgery with instrumented fusion before two year follow-up. ††One patient excluded because of missing baseline values and follow-up values

Patients’ characteristics

Most baseline characteristics were similar in the two treatment groups (table 1). Low back pain score and SF-36 mental health subscores, however, were significantly worse in the rehabilitation group than in the surgery group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in patients with low back pain and degenerative disc randomised to disc prosthesis surgery or rehabilitation. Figures are numbers (percentage) unless stated otherwise

| Surgery (n=86) | Rehabilitation (n=86) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 41.1 (7.1) | 40.8 (7.1) |

| Women | 40 (47) | 51 (59) |

| Mean (SD) duration of back pain (months) | 76 (72 | 85 (74) |

| Education: | ||

| Primary school (9 years) | 19 (22) | 17 (20) |

| High school (12 years) | 44 (51) | 58 (67) |

| College | 14 (16) | 8 (9) |

| University | 9 (11) | 3 (4) |

| Mean (SD) body mass index (BMI) | 25.6 (3.1) | 25.5 (3.5) |

| Current smokers | 42 (49) | 37 (43) |

| Work status (working v not working): | ||

| Working (includes part time sick leave) | 24 (28) | 22 (26) |

| On sick leave | 25 (29) | 34 (41) |

| Rehabilitation | 29 (34) | 25 (29) |

| Disability pension | 3 (4) | 0 |

| Homemaker | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Unemployed | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Student | 3 (4) | 0 |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 3 (4) |

| Comorbidity | 20 (23) | 21 (24) |

| Daily consumption of narcotics | 23 (27) | 17 (20) |

| Previous surgery | 23 (27) | 25 (29) |

| Mean (SD) ODI score | 41.8 (9.1) | 42.8 (9.3) |

| Low back pain score* | 64.9 (15.3) | 73.6 (13.9) |

| Mean (SD) SF-36 score: | ||

| Physical function | 52.7 (17.6) | 50.6 (17.7) |

| Role physical | 25.3 (24.2 | 23.9 (18.7) |

| Bodily pain | 24.9 (16.5) | 24.4 (12.1) |

| General health | 57.9 (19.7) | 55.9 (19.9) |

| Vitality | 37.8 (20.2) | 33.1 (19.9) |

| Social function | 53.0 (30.6) | 57.6 (26.7) |

| Role emotion | 72.5 (33.3) | 67.6 (32.7) |

| Mental health | 71.7 (18.0) | 65.8 (18.9) |

| Physical component summary score | 30.5 (7.1) | 30.8 (6.5) |

| Mental component summary score | 47.7 (13.0) | 45.2 (13.2) |

| Mean (SD) HSCL-25 | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.5) |

| Mean (SD) FABQ work | 25.9 (11.3) | 27.4 (9.9) |

| Mean (SD) FABQ physical | 14.1 (5.8) | 12 (5.5) |

ODI=Oswestry disability index (0 to 100, lower scores indicate less severe symptoms); SF-36=short form-36 (0 to 100, higher scores indicate better health status); HSCL-25=Hopkins symptom check list (for emotional distress, scores range from 1 to 4, lower scores indicate less severe symptoms); FABQ=fear avoidance belief questionnaire (scale ranges from 0 to 24 (physical) and from 0 to 42 (work), lower scores indicate less severe symptoms).

*Calculated with horizontal scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst pain imaginable), with word anchors at the beginning and end.

Surgical treatment and complications

Of the patients randomised to surgery, 25 (33%) underwent two level surgery. Median surgical time was 165 minutes (range 72-570 minutes) and median blood loss was 310 ml (range 50-6000 ml) (table 2). Four patients had bleeding of more than 1500 ml.

Table 2.

Treatment and complications in 77 patients with low back pain and degenerative disc randomised to disc prosthesis surgery

| Variable | Surgery group |

|---|---|

| No (%) by level of operation: | |

| L4/L5 | 17 (22) |

| L5/S1 | 35 (46) |

| L4/L5 and L5/S1 | 25 (33) |

| Median (range) operative time (min) | 165 (72-570) |

| Median (range) blood loss (ml) | 310 (50-6000) |

| Mean (SD) length of hospital stay (days) | 7.2 (3.6) |

| No with complications: | |

| Intimal lesion in left common iliac artery* | 1 |

| Arterial thrombosis of dorsalis pedis artery† | 1 |

| Dural tear | 0 |

| Blood loss >1500 ml | 4 |

| Retrograde ejaculation (at one year) | 1‡ |

| Abdominal hernia | 1 |

| Superficial haematoma | 1 |

| Ileus | 1 |

| Temporary warm left foot | 2 |

| Temporary nausea at one year follow-up | 1 |

| Neurological deterioration: | |

| Motor deficit at two year follow-up | 0 |

| Temporary motor deficit | 0 |

| Sensory loss at two year follow-up | 2 |

| Temporary sensory loss | 4 |

| Radicular pain at two year follow-up | 2 |

| Temporary radicular pain | 4 |

| Infection: | |

| Superficial wound infection | 0 |

| Deep wound infection | 0 |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 |

| Total No (%) complications during two year follow-up | 26 (34) |

| Additional spinal surgery within 2 years: | |

| Fusion | 2§ |

| Other | 2¶ |

*Repeat surgery with insertion of new polyethylene inlay.

†Associated with temporary slightly colder foot at follow-up.

‡One patient reported retrograde ejaculation at baseline but not at one year follow-up, one at baseline and at follow-up, and one at follow-up but without baseline information.

§Fusion at level with disc prosthesis and level above.

¶Resection of spinous process because of possible painful contact between adjacent levels.

Six patients (8%) had complications resulting in impairment at two year follow-up, and the reoperation rate was 6.5% (n=5) (table 2). One patient had a serious complication: at the three month follow-up, the polyethylene inlay was found to be dislodged. During revision surgery, injury to the left common iliac artery led to compartment syndrome resulting in a lower leg amputation. One patient reported retrograde ejaculation at one year follow-up. At two year follow-up, two patients reported sensory loss in the thigh and two patients reported new radicular pain. In addition, one patient had an arterial thrombosis of the dorsalis pedis artery, which temporarily resulted in a slightly colder foot. Table 2 presents further complications. Two patients had an additional fusion and two patients had partial resection of the spinous processes because of persistent back pain.

Primary outcome

Planned analyses according to protocol

The mean change Oswestry disability index score from baseline to two year follow-up was 20.8 (95% confidence interval 16.4 to 25.2) in the surgery group and 12.4 (8.5 to 16.3) in the rehabilitation group (table 3). The mean treatment effect (difference between groups) at two year follow-up was −8.4 (−13.2 to −3.6) in the intention to treat analysis (last value carried forward). Subgroup analysis showed no differences in the main outcome variable between centres and level(s) operated on.

Table 3.

Planned analysis of primary outcome in patients with low back pain and degenerative disc randomised to disc prosthesis surgery or rehabilitation. Mean (SD) outcome values on Oswestry disability index (ODI) at 12 and 24 months and treatment effect

| Mean outcome | Treatment effect* (95% CI) | P value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Rehabilitation | |||

| Baseline | 41.8 (9.1) | 42.8 (9.3) | — | — |

| 1 year | 22.3 (17.0) | 33.0 (16.6) | −10.0 (−15.0 to −5.0) | <0.001 |

| 2 years | 21.2 (17.1) | 30.0 (16.0) | −8.4 (−13.2 to −3.6) | 0.001 |

ODI=see footnote for table 1 for scale details.

*Difference between groups in mean change from baseline.

†Two sided t test.

Unplanned analyses

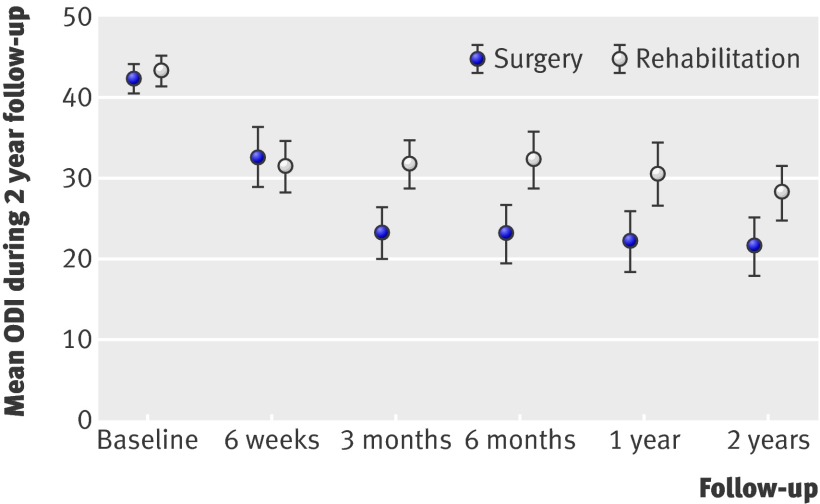

In the mixed model analysis, the Oswestry score improved significantly more in the surgical group than in the rehabilitation group at all time points, in both the intention to treat (fig 2) and per protocol analyses (table 4). The mean change from baseline to two year follow-up was 22.5 (intention to treat) (95% confidence interval 18.5 to 26.4) in the surgery group and 15.6 (intention to treat) (11.7 to 19.5) in the rehabilitation group. The mean treatment effect (difference between groups) at two year follow-up was 6.9 (2.1 to 11.7) in the intention to treat analysis. In an analysis in which the patient with lower leg amputation was given worst score in the group, the difference between the groups remained significant (P<0.001). Some 70% (n=51) of the patients in the surgery group and 47% (n=31) of the patients in the rehabilitation group had an improvement in Oswestry score of at least 15 points (P<0.006) (intention to treat). The number needed to treat was 4.4 (2.6 to 14.5). Worsening of low back pain was experienced by 11% (n=8) of the surgical group and 9% (n=6) of the rehabilitation group. Subgroup analysis showed no differences in the main outcome variable between centres and level(s) operated on.

Fig 2 Primary outcome variable within intention to treat mixed model analysis. Mean difference in Oswestry disability index (ODI) was 6.9 points at two year follow-up, P<0.001 (adjusted for baseline index)

Table 4.

Unplanned analysis of primary outcome in patients with low back pain and degenerative disc randomised to disc prosthesis surgery or rehabilitation. Mean (SD) outcome values on Oswestry disability index (ODI) at follow-up and treatment effect (difference (95% confidence interval)), minus values indicating larger improvement in outcome with surgery

| Intention to treat analysis | Per protocol analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Rehabilitation | Treatment effect | Surgery | Rehabilitation | Treatment effect* | ||

| Baseline | 41.8 (9.1) | 42.8 (9.3) | — | 42.2 (9.2) | 42.1 (8.3) | — | |

| 6 weeks | 31.5 (17.2) | 30.2 (13.6) | 1.3 (−3.5 to 6.1) | 31.1 (17.3) | 29.6 (13.5) | 1.7 (−3.1 to 6.6) | |

| 3 months | 21.5 (14.1) | 30.6 (13.1) | −9.1 (−13.9 to −4.3) | 20.7 (13.5) | 30.3 (12.7) | −9.5 (−14.4 to −4.6) | |

| 6 months | 21.4 (16.3) | 31.1 (14.9) | −9.7 (−14.6 to −4.8) | 20.7 (15.9) | 29.9 (14.6) | −9.2 (−14.2 to −4.2) | |

| 1 year | 20.3 (17.2) | 29.2 (16.1) | −8.9 (−13.8 to −4.0) | 19.7 (16.4) | 27.0 (15.0) | −7.3 (−12.3 to −2.3) | |

| 2 years | 19.8 (16.7) | 26.7 (14.5) | −6.9 (−11.7 to −2.1) | 18.8 (15.8) | 26.9 (13.9) | −8.1 (−12.9 to −3.2) | |

ODI=see footnote for table 1 for scale details.

*All P<0.001 for trend in treatment effect over time. Two sided t test.

Secondary outcomes

Planned analyses according to protocol

Low back pain, SF-36 physical summary, and patients’ satisfaction improved significantly more in the surgical group than the rehabilitation group at two year follow-up (table 5). The mean difference between the groups in change from baseline to two year follow-up was −12.2 (95% confidence interval −21.3 to −3.1) for low back pain and 5.8 (2.5 to 9.1) for SF-36 physical summary. On the seven point global rating scale at two years, 63% (46) of patients in the surgery group and 39% (26) in the rehabilitation group (P=0.005 for difference between treatment groups) considered themselves completely recovered or much improved. Self efficacy for pain favoured the surgical group. SF-36 mental summary, EQ-5D, FABQ work and physical, HSCL-25, return to work, and drug consumption did not differ at two year follow-up. At the start of the study, 28% (46) of patients were at work full or part time; at two year follow-up, this had increased to 56% (n=74). There was a “net back to work” rate of 31% (n=21) in the surgical group and 23% (n=15) in the rehabilitation group (P=0.31) (table 5). Scores on the back performance scale did not differ significantly between the groups (−0.8, −1.8 to 0.2; P=0.10). The Prolo sum score favoured the surgical group, with a mean difference of 0.9 (0.1 to 1.6; P=0.019).

Table 5.

Planned analysis of secondary outcomes in patients with low back pain and degenerative disc randomised to disc prosthesis surgery or rehabilitation. Mean (SD) values at 12 and 24 months (unless stated otherwise) and treatment effect

| Variable | Mean outcome | Treatment effect (95% CI)* | P value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Rehabilitation | |||

| Back pain score‡: | ||||

| Baseline | 64.9 (15.3) | 73.6 (13.9) | ||

| 1 year | 35.6 (28.6) | 53.2 (28.4) | −14.0 (−23.0 to −5.0) | 0.003 |

| 2 years | 35.4 (29.1) | 49.7 (28.4) | −12.2 (−21.3 to −3.1) | 0.009 |

| SF-36 physical component summary: | ||||

| Baseline | 30.5 (7.1) | 30.8 (6.5) | ||

| 1 year | 42.8 (12.2) | 37.3 (11.0) | 5.5 (1.9 to 9.1) | 0.003 |

| 2 years | 43.3 (11.7) | 37.7 (10.1) | 5.8 (2.5 to 9.1) | 0.001 |

| SF-36 mental component summary‡: | ||||

| Baseline | 47.7 (13.0) | 45.2 (13.2) | ||

| 1 year | 50.2 (12.0) | 49.2 (13.2) | 0.2 (−3.5 to 3.8) | 0.90 |

| 2 years | 50.7 (11.6) | 48.6 (12.8) | 1.0 (−2.4 to 4.4) | 0.50 |

| EQ-5D: | ||||

| Baseline | 0.30 (0.27) | 0.27 (0.31) | ||

| 1 year | 0.68 (0.34) | 0.55 (0.32) | 0.13 (0.01 to 0.25) | 0.04 |

| 2 years | 0.69 (0.33) | 0.63 (0.28) | 0.06 (−0.05 to 0.18) | 0.26 |

| HSCL-25 | ||||

| Baseline | 1.81 (0.50) | 1.88 (0.51) | ||

| 1 year | 1.51 (0.49) | 1.67 (0.52) | −0.12 (−0.26 to 0.02) | 0.10 |

| 2 years | 1.50 (0.44) | 1.63 (0.52) | −0.10 (−0.23 to 0.04) | 0.20 |

| FABQ work: | ||||

| Baseline | 25.8 (11.2) | 27.4 (27.4) | ||

| 1 year | 19.2 (14.2) | 23.1 (13.0) | −2.7 (−6.5 to 1.1) | 0.20 |

| 2 years | 18.1 (13.9) | 21.2 (12.8) | −2.1 (−6.0 to 1.7) | 0.30 |

| FABQ physical: | ||||

| Baseline | 14.0 (5.8) | 12.5 (5.6) | ||

| 1 year | 8.8 (6.7) | 9.7 (5.8) | −1.3 (−3.2 to 0.6) | 0.20 |

| 2 years | 9.0 (6.8) | 9.9 (6.0) | −1.5 (−3.4 to 0.5) | 0.10 |

| Self efficacy: | ||||

| Baseline | 3.4 (1.5) | 3.6 (1.6) | ||

| 1 year | 6.3 (3.3) | 5.2 (2.4) | 1.2 (0.3 to 2.1) | 0.01 |

| 2 years | 6.1 (2.9) | 5.3 (2.5) | 1.0 (0.2 to 1.9) | 0.02 |

| No (%) returned to work at 2 years§: | 21 (31) | 15 (23) | — | 0.31 |

| No (%) satisfied with outcome at 2 years¶ | 46 (63) | 26 (39) | — | 0.005 |

| No (%) satisfied with care at 1 year** | 66 (90) | 48 (73) | — | 0.011 |

| No (%) with drug consumption at 2 years†† | 16 (22) | 14 (18) | — | 0.30 |

| Back performance scale at 2 years‡‡ | 3.2 (3.0) | 4.0 (3.0) | −0.8 (−1.8 to 0.2) | 0.10 |

| Prolo scale at 2 years§§ | 7.0 (2.3) | 6.1 (1.9) | 0.9 (0.1 to 1.6) | 0.019 |

ED-5Q score ranges from −0.59 to 1 (1 equals perfect health); self efficacy beliefs for pain scores ranges from 1 to 10 and are summarised and divided by 5. Lower scores indicate that he/she is very uncertain if he/she is able to manage pain. For other scores see footnote to table 1.

*Treatment effect is difference between groups in mean change from baseline. Positive value in SF-36, EQ-5D, self efficacy for pain, and Prolo scale and negative values in remaining variables indicate larger improvement in outcome with surgery.

†Two sided t test for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables.

‡Values not adjusted for significantly different baseline scores.

§Net back to work rate calculated by subtracting patients who went back to work from patients who stopped working.

¶7 point Likert scale (1=completely recovered, 2=much recovered to 7=vastly worsened); slightly improved not included as satisfied with outcome.

**4 point global rating scale, not including slightly satisfied as satisfied with care.

††Use of drugs daily or not.

‡‡Scale comprises five tests with score ranging from 0 to 15 (worst possible).

§§Scale comprises functional and economic parts, summed to give worst score of 2 and best score of 10.

Unplanned analyses

In the mixed model analysis, low back pain (table 6), SF-36 physical summary (table 8), and EQ-5D, HSCL-25, and self efficacy for pain (table 9) improved significantly more in the surgical group than the rehabilitation group at all time points. The mean difference between the groups in change from baseline to two year follow-up for low back pain was −12.7 (95% confidence interval −21.1 to −4.2, table 6) and SF-36 physical summary 4.3 (0.8 to 7.9, table 8). Further analyses are shown in tables 7, 8, and 9.

Table 6.

Unplanned analysis in secondary outcome in patients with low back pain and degenerative disc randomised to disc prosthesis surgery or rehabilitation. Mean (SD) outcome values for back pain* at follow-up and treatment effect (difference (95% confidence interval))

| Intention to treat analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Rehabilitation | Treatment effect† | |

| Baseline | 64.9 (15.3) | 73.6 (13.9) | — |

| 6 weeks | 34.7 (27.5) | 51.1 (24.6) | −16.5 (−24.8 to −8.2) |

| 3 months | 29.3 (25.0) | 55.4 (23.4) | −26.2 (−34.5 to −17.8) |

| 6 months | 36.1 (28.5) | 50.0 (24.5) | −13.8 (−22.3 to −5.3) |

| 1 year | 33.0 (29.4) | 48.7 (28.9) | −15.7 (−24.3 to −7.0) |

| 2 years | 32.7 (28.8) | 45.3 (28.6) | −12.7 (−21.1 to −4.2) |

*See table 1 for score details.

†Negative values indicate larger improvement in outcome with surgery. All P<0.001 for trend in treatment effect over time. Two sided t test.

Table 8.

Unplanned analysis in secondary outcome in patients with low back pain and degenerative disc randomised to disc prosthesis surgery or rehabilitation. Mean (SD) outcome values for physical and mental component summary scores on SF-36* at follow-up and treatment effect (difference (95% confidence interval))

| Surgery | Rehabilitation | Treatment effect† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 physical component summary | |||

| Baseline | 30.5 (7.1) | 30.8 (6.5) | — |

| 3 months | 40.3 (10.9) | 37.3 (8.9) | 3.0 (−0.6 to 6.6) |

| 6 months | 41.4 (12.3) | 37.2 (9.2) | 4.2 (0.6 to 7.8) |

| 1 year | 43.5 (12.7) | 39.4 (11.5) | 4.2 (0.6 to 7.7) |

| 2 years | 43.9 (11.9) | 39.6 (10.4) | 4.3 (0.8 to 7.9) |

| SF-36 mental component summary | |||

| Baseline | 47.7 (13.0) | 45.2 (13.2) | — |

| 3 months | 50.9 (10.4) | 47.0 (12.9) | 3.9 (−0.2 to 8.0) |

| 6 months | 52.0 (9.7) | 49.5 (10.5) | 2.5 (−1.6 to 6.6) |

| 1 year | 51.7 (11.6) | 49.7 (12.0) | 2.0 (−2.0 to 6.1) |

| 2 years | 51.0 (11.0) | 50.5 (11.0) | 0.5 (−3.4 to 4.5) |

*See table 1 for score details.

†Positive treatment effect indicates larger improvement in outcome for surgery. P=0.002 for physical and 0.166 for mental for trend in treatment effect over time.

Table 9.

Secondary outcomes in patients with low back pain and degenerative disc randomised to disc prosthesis surgery or rehabilitation. Mean (SD) outcome values on EQ-5D, HSCL-25, FABQ, and self efficacy at follow-up and treatment effect (difference (95% confidence interval))

| Variable* | Surgery | Rehabilitation | Treatment effect† |

|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D‡ | |||

| Baseline | 0.30 (0.30) | 0.27 (0.31) | — |

| 6 weeks | 0.59 (0.30) | 0.55 (0.29) | 0.04 (−0.06 to 0.15) |

| 3 months | 0.70 (0.23) | 0.48 (0.31) | 0.22 (0.12 to 0.33) |

| 6 months | 0.68 (0.28) | 0.51 (0.33) | 0.17 (0.06 to 0.27) |

| 1 year | 0.67 (0.35) | 0.54 (0.32) | 0.13 (0.02 to 0.23) |

| 2 years | 0.68 (0.34) | 0.60 (0.30) | 0.08 (−0.03 to 0.18) |

| HSCL-25§ | |||

| Baseline | 1.81 (0.50) | 1.88 (0.51) | — |

| 3 months | 1.38 (0.34) | 1.66 (0.51) | −0.27 (−0.44 to −0.11) |

| 6 months | 1.44 (0.45) | 1.66 (0.49) | −0.22 (−0.38 to −0.05) |

| 1 year | 1.45 (0.50) | 1.59 (0.49) | −0.14 (−0.30 to 0.03) |

| 2 years | 1.47 (0.49) | 1.55 (0.50) | −0.09 (−0.25 to 0.08) |

| FABQ work§ | |||

| Baseline | 25.8 (11.2) | 27.4 (9.9) | — |

| 3 months | 20.0 (12.9) | 24.3 (11.9) | −4.3 (−8.6 to 0.1) |

| 6 months | 18.7 (12.9) | 23.0 (12.7) | −4.3 (−8.7 to 0.1) |

| 1 year | 18.2 (13.9) | 21.3 (13.2) | −3.1 (−7.4 to 1.2) |

| 2 years | 16.7 (13.5) | 18.5 (12.5) | −1.8 (−6.1 to 2.5) |

| FABQ physical§ | |||

| Baseline | 14.0 (5.8) | 12.5 (5.6) | — |

| 3 months | 8.8 (5.3) | 9.1 (6.3) | −0.3 (−2.4 to 1.7) |

| 6 months | 8.6 (6.3) | 9.3 (6.7) | −0.7 (−2.8 to 1.3) |

| 1 year | 8.0 (6.3) | 8.9 (5.8) | −0.8 (−2.9 to 1.2) |

| 2 years | 8.0 (6.0) | 8.3 (5.7) | −0.3 (−2.3 to 1.7) |

| Self efficacy‡ | |||

| Baseline | 3.4 (1.5) | 3.6 (1.6) | — |

| 3 months | 6.1 (2.3) | 5.0 (2.2) | 1.0 (0.2 to 1.9) |

| 6 months | 6.0 (2.6) | 5.6 (2.4) | 0.5 (−0.3 to 1.3) |

| 1 year | 6.4 (3.3) | 5.5 (2.5) | 0.9 (0.0 to 1.7) |

| 2 years | 6.2 (2.7) | 5.6 (2.7) | 0.5 (−1.4 to 2.8) |

*See tables 1 and 5 for score details.

†EQ-5D P<0.001, HSCL P<0.001, FABQ work P=0.057, FABQ physical P=0.548, self efficacy P=0.019 for trend in treatment effect over time.

‡Positive scores indicate larger improvement in outcome with surgery.

§Negative scores indicate larger improvement in outcome with surgery.

Table 7.

Unplanned analysis in secondary outcomes in patients with low back pain and degenerative disc randomised to disc prosthesis surgery or rehabilitation. Mean (SD) outcome values for SF-36*

| Variable | Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 1 year | 2 years | P value† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Rehabilitation | Surgery | Rehabilitation | Surgery | Rehabilitation | Surgery | Rehabilitation | Surgery | Rehabilitation | ||

| Physical function | 52.7 (17.6) | 50.6 (17.8) | 76.2 (18.3) | 64.0 (22.4) | 76.0 (21.4) | 63.7 (21.0) | 79.5 (20.6) | 66.7 (22.9) | 78.9 (20.2) | 69.6 (22.2) | <0.001 |

| Role physical | 25.3 (24.2) | 23.9 (18.7) | 50.0 (31.5) | 45.6 (31.9) | 57.2 (35.1) | 47.8 (31.2) | 58.9 (37.3) | 55.9 (33.9) | 66.4 (33.5) | 55.1 (35.0) | 0.135 |

| Bodily pain | 24.9 (16.5) | 24.4 (12.1) | 48.2 (22.4) | 34.9 (16.1) | 50.8 (29.1) | 39.1 (20.8) | 52.5 (30.8) | 43.5 (24.6) | 55.5 (29.1) | 44.4 (23.0) | <0.001 |

| General health | 57.9 (19.7) | 55.9 (19.9) | 67.6 (22.8) | 60.7 (24.7) | 65.5 (24.3) | 60.1 (24.4) | 68.1 (26.8) | 61.7 (22.1) | 65.7 (26.0) | 61.1 (24.8) | 0.125 |

| Vitality | 37.8 (20.2) | 33.1 (20.0) | 50.3 (21.6) | 44.4 (22.1) | 55.6 (23.7) | 45.7 (22.9) | 57.5 (27.5) | 48.2 (24.9) | 55.0 (27.1) | 46.8 (23.5) | 0.003 |

| Social function | 53.0 (30.6) | 57.6 (26.7) | 72.8 (25.0) | 68.8 (25.6) | 75.0 (28.6) | 71.1 (26.7) | 76.7 (25.7) | 74.3 (26.8) | 78.3 (26.8) | 77.9 (27.4) | 0.725 |

| Role emotion | 72.5 (33.3) | 67.6 (32.7) | 85.1 (23.3) | 69.0 (34.7) | 83.3 (26.3) | 74.5 (29.8) | 80.4 (31.0) | 79.2 (26.3) | 83.9 (25.6 ) | 79.2 (29.0) | 0.010 |

| Mental health‡ | 71.7 (18.0) | 65.8 (18.7) | 78.6 (15.6) | 72.4 (17.9) | 79.5 (16.8) | 74.1 (16.4) | 80.4 (17.5) | 73.8 (20.9) | 78.3 (18.2) | 75.8 (17.5) | 0.007 |

*See table 1 for score details.

†For trend in treatment effect over time.

‡Values are not adjusted for significantly different baseline scores.

Discussion

This randomised trial comparing disc prosthesis with multidisciplinary rehabilitation showed a significant difference in the primary outcome variable (Oswestry disability index after two years) in favour of surgery. The difference between groups of 8.4 points on the index (with intention to treat analysis) at two year follow-up, however, was smaller than the difference of 10 points that the study was designed to detect. As evident in the confidence intervals, the data are consistent with a wide range of differences between the groups, including values well below 10 points. There is, as far as we know, no agreement on the size of the clinically important difference between two treatment groups. As an alternative we can assess the proportion of patients achieving a clinically meaningful improvement.31 By using a clinically meaningful improvement for an individual patient of 15 points on the Oswestry disability index,8 70% (n=51) of patients in the surgical group and 47% (n=31) of those in the rehabilitation group achieved at least this improvement (intention to treat). We will publish data on the estimated minimal clinically important change elsewhere, but the changes are in agreement with recommendations from FDA studies. As there is no consensus based agreement of how large a difference between groups must be to be of clinical importance it is impossible to conclude whether the effect found in our study is of clinical importance. As such a decision must be made before a new treatment can be recommended in clinical practice; our study underlines the need for such a consensus agreement.

The change in the Oswestry disability index score in our study is comparable with those seen in previous studies. In our study, the mean score was reduced by 29% (12.4 points) in the rehabilitation group (intention to treat analysis). Brox et al4 found a similar reduction of 29% (12.0 points) at one year follow-up, while Fairbank et al6 and Fritzell et al3 observed a smaller reduction at two year follow-up (8.7 and 5.5 points, respectively). In our study, there was a mean reduction in score of 50% (20.8 points) in the surgical arm (intention to treat analysis). Similar reductions have been reported in other studies,8 9 11 though Zigler et al used the “chiropractor version” of the Oswestry index.32 This questionnaire has not been sufficiently validated and consequently it is difficult to compare the outcome.18

It could be argued that patients who withdrew after randomisation or dropped out during or after treatment had a superior or inferior outcome. We therefore sent a questionnaire to such patients. The nine patients who withdrew after surgery experienced a reduction in Oswestry score of 30.2 (SD 4.5) points. The six who withdrew after rehabilitation had a reduction of 11.8 (SD 3.0), and the 11 patients who withdrew without treatment had no change (1.0 (SD 4.5) points) (see table B in appendix 3 on bmj.com). This might support the assumption of no improvement in outcome after drop-out, justifying use of the last value carried forward analysis.

Most changes in secondary variables measuring disability and pain favoured surgical treatment, though there were no significant differences between groups in FABQ work, FABQ physical, SF-36 mental health, EQ-5D, HSCL-25, drug consumption, return to work, and the back performance scale in the main analysis. In the surgical group we found a similar “net back to work” rate as reported by Fritzell et al.3 Nevertheless, it has been argued that sick leave, to a large extent, is influenced by factors outside the domain of medical and therapeutic interventions.33 The somewhat smaller difference between groups in the back performance scale than in the Oswestry disability index might be explained by differences in psychometric properties between the outcome measurements or by patients overstating the effect in a subjective questionnaire.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. It was randomised and had few patients who crossed over to the other treatment regimen. In addition, an independent research assistant collected the data, the observers at the two year evaluation were blinded, the interventions were standardised, and the financing of the study was public. Choosing magnetic resonance imaging criteria for inclusion could be a strength or limitation. To our knowledge, there are no specific criteria to determine which degenerative changes should be operated on. When designing the study we wanted the inclusion of patients across centres to be as unanimous as possible, treating the same population, although this possibly would lead to less external validity of the study. It could also possibly lead to inclusion of more severe degenerated discs in our study compared with other studies.8 9

One limitation of our study is the lack of a placebo or sham group. The regression to the mean and the natural resolution of chronic low back pain must also be considered in both groups. When balancing a non-operative regimen with an operative treatment, there is probably a difference in placebo effect that is difficult to untangle from the treatment effect.34 35 36 37 The placebo effect might be higher in the surgical group, although the possible placebo effect of rehabilitation over several weeks with personal contact with a therapist should not be underestimated. Furthermore, it could be argued that the patients included in the study wanted surgery, but the number of patients not wanting the rehabilitation programme was similar to the number of patients not wanting surgery (see figure and appendix 1 on bmj.com). Brox et al found no difference in treatment effect between patients who did and did not “believe” in surgery,4 5 and a recent study found no significant relation between baseline expectations and follow-up scores.38 On the other hand, “expectation being fulfilled” might be a predictor of global outcome.38 During the inclusion process, we emphasised the advantages and disadvantages of the two treatment options and that none of the treatments are documented as superior to another. It is still possible, however, that patients in the rehabilitation group found themselves faced with “more of the same.” The lack of routine rehabilitation in the surgical arm could be another limitation in the study. We wanted to avoid the postoperative treatment containing elements from the rehabilitation programme. Hence, patients received only general advice when they were discharged from the hospital and received no rehabilitation in the first weeks after surgery. At six weeks, however, patients could be referred if required to a physiotherapist at their home for functional mobilisation and general muscle training. Furthermore, some surgical patients underwent a second operation but repeat rehabilitation was not considered. Patients did not request a second chance for rehabilitation, though they were advised during follow-up consultations. Another weakness in our study is the difference in compliance between groups and the high drop-out rate. This difference in adherence to the protocol probably leads to an underestimate of the true effect of surgery, especially in the intention to treat analysis. In similar studies comparing surgery with rehabilitation, the drop-out rates were similar to ours.6 39 40 41 The patients we included in our study were highly selected, with one or two level degenerative changes and good general health. Thus, our results are valid only in similar patients. Furthermore, we examined several secondary outcome variables that could lead to the detection of differences by chance. Although we conducted several unplanned analyses (not recorded in the original protocol), in common with similar studies, we consider it as an important asset to our data. Lately, similar studies have applied repeated measurements by using mixed models.40 Using unplanned analysis could be considered a weakness, but our findings in these analyses support our main analyses and strengthen our conclusion. Nevertheless, caution should be used in interpreting the results of non-prespecified analyses.

Potential harms of disc prosthesis surgery

Surgery carries a risk of serious complications, as seen in one of our patients. In a review by Inamasu et al, the perioperative vascular injury rate for anterior lumbar interbody fusion was 0-18% (mean 3%).42 This is an important drawback of surgery. No major differences in complication rates between insertion of a disc prosthesis and fusion have been found in a randomised setting.8 9 11 The short term reoperation rate in our study was 6.5% (n=5) and the vascular injury rate was 6.5% (n=5) (table 2). Although vascular complications are reported, serious consequences like amputation and mortality are rare.43 Recently Kurtz et al looked at the rates of short term revision and mortality total disc replacement.43 They found similar reoperation rates as with anterior fusion surgery and hip arthroplasty. Four retrospective studies have reported long term reoperation rates of up to 13%.44 45 46 47 Data on the anterior revision rate of the prosthesis is difficult to extract from these studies but seems considerably lower. The potential long term revision rate with a higher complication rate on revisions needs to be considered.48

Earlier addressed but unresolved questions are the incidence of adjacent level degeneration after total disc replacement and distinct characteristics of patients associated with good outcome. Some studies have examined these issues but more information is needed.49 50 51 In a univariate analysis we found indications that patients with Modic I or II changes have a superior result in the surgical arm and that patients with high Oswestry scores seem to be more suitable for rehabilitation. A full multivariate analysis of good outcomes will be published soon to answer these questions. Another important issue is the incidence of degeneration in the facet joints of the operated level. An analysis of adjacent level degeneration and degeneration of the operated level in addition to a full health economic analysis will be published later.

The total blood loss and operation time were higher in our study than in similar studies. The learning curve might be quite flat, and perhaps the participating surgeons should have carried out disc prosthesis surgery in more patients before the start of the study. Using a surgeon to expose the disc (access surgeon), might also have reduced the blood loss and operation time. Blumenthal et al and Zigler et al performed one level surgery, while a third of our patients underwent two level surgery.8 9 This could explain some of the increased blood loss and operation time in our study. Because of the complexity of the surgery and the risk of serious complications, we think this kind of surgery should be confined to a few specialist centres with experienced spine surgeons and available vascular surgeons. A high quality rehabilitation programme should be available.

Our study was not designed to evaluate specific mechanisms of reduction of pain and disability. Possible explanations for the pain reduction are removal of the disc in the surgical group and better coping in the rehabilitation group, but the patients were heterogeneous and probably had a mixed aetiology difficult to separate. Even though we did not have a control group, the mixed causes of chronic low back pain, the association of surgery with potentially serious complications, and the considerable improvement in the rehabilitation group suggest that it is reasonable to consider a rehabilitation programme before surgery.

What is already known on this topic

In patients with chronic low back pain, compared with fusion, the clinical outcome with disc prosthesis has been at least equivalent

Compared with multidisciplinary rehabilitation, improvement in disability and pain are similar

What this study adds

Surgery with disc prosthesis resulted in a significantly greater improvement in scores on the Oswestry disability index and variables measuring disability and pain, although the difference in Oswestry score between groups was lower than the study was designed to detect

There were no differences in return to work and several outcomes measuring mental health

We thank the patients participating in the study; Coast Hospital for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Stavern, for videos and material for lectures for the rehabilitation intervention; Hege Andresen at St Olavs Hospital, Trondheim, for data coordination; Per Farup at St Olavs Hospital, Trondheim, for organising the web randomisation system; Astrid Woodhouse and Kirsti Vanvik from St Olavs Hospital for performing the two year control; and Lucy Hyatt for paid editorial assistance.

The Norwegian Spine Study Group

University Hospital North Norway, Tromso (eight patients): Odd-Inge Solem (department of orthopaedic surgery), Jens Munch-Ellingsen (department of neurosurgery), and Franz Hintringer, Anita Dimmen Johansen, Guro Kjos (department of physical medicine and rehabilitation).

Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim (21 patients): Hege Andresen, Helge Rønningen, Kjell Arne Kvistad (national centre for spinal disorders, department of neurosurgery), Bjørn Skogstad, Janne Birgitte Børke, Erik Nordtvedt, Gunnar Leivseth (multidiscipline spinal unit, department of physical medicine and rehabilitation).

Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen (64 patients): Sjur Braaten, Turid Rognsvåg, Gunn Odil Hirth Moberg (Kysthospitalet in Hagevik, department of orthopaedic surgery), Jan Sture Skouen, Lars Geir Larsen, Vibeche Iversen, Ellen H Haldorsen, Elin Karin Johnsen, Kristin Hannestad (Outpatient Spine Clinic, department of physical medicine and rehabilitation).

Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger (27 patients): Endre Refsdal (department of orthopaedic surgery).

Oslo University Hospital, Oslo (53 patients): Vegard Slettemoen, Kenneth Nilsen, Kjersti Sunde, Helenè E Skaara (department of orthopaedics), Anne Keller, Berit Johannessen, Anna Maria Eriksdotter (department of physical medicine and rehabilitation).

Contributors: All authors had full access to the data, were responsible for study concept and design, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Acquisition of data: CH, LGJ, KS, OPN, MR, OG acquired the data, which were analysed and interpreted by HC , LGJ, KS, OPN, JIB, LS, IR, and OG. CH drafted the manuscript. CH and LS did the statistical analysis. CH, LJ, KS, OPN, JIB, MR, and OG provided administrative, technical, or material support. CH, KS, OPN, JIB, IR, LS, and OG supervised the study. CH is guarantor.

Funding: The study was funded by the South Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority and EXTRA funds from the Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation, through the Norwegian Back Pain Association.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was evaluated and approved by the regional committees for medical research ethics in east Norway and all participants gave written informed consent. We did not obtain participants’ informed consent for data but the presented data are anonymised and risk of identification is low.

Data sharing: Dataset available from the corresponding author at christian.hellum@medisin.uio.no.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d2786

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria, compliance with randomisation, and drop-outs

Appendix 2: Rehabilitation intervention

Appendix 3: Supplementary tables

References

- 1.Waddell G. The back pain revolution. 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

- 2.Thomas E, Silman AJ, Croft PR, Papageorgiou AC, Jayson MI, Macfarlane GJ. Predicting who develops chronic low back pain in primary care: a prospective study. BMJ 1999;318:1662-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A, for the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Clinical Studies: lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine 2001;26:2521-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brox JI, Sorensen R, Friis A, Nygaard O, Indahl A, Keller A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of lumbar instrumented fusion and cognitive intervention and exercises in patients with chronic low back pain and disc degeneration. Spine 2003;28:1913-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brox JI, Reikeras O, Nygaard O, Sorensen R, Indahl A, Holm I, et al. Lumbar instrumented fusion compared with cognitive intervention and exercises in patients with chronic back pain after previous surgery for disc herniation: a prospective randomized controlled study. Pain 2006;122:145-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fairbank J, Frost H, Wilson-MacDonald J, Yu LM, Barker K, Collins R. Randomised controlled trial to compare surgical stabilisation of the lumbar spine with an intensive rehabilitation programme for patients with chronic low back pain: the MRC spine stabilisation trial. BMJ 2005;330:1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brox JI, Nygaard O, Holm I, Keller A, Ingebrigtsen T, Reikeras O. Four-year follow-up of surgical versus non-surgical therapy for chronic low back pain. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;69:1643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenthal S, McAfee PC, Guyer RD, Hochschuler SH, Geisler FH, Holt RT, et al. A prospective, randomized, multicenter Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemptions study of lumbar total disc replacement with the CHARITE artificial disc versus lumbar fusion: part I: evaluation of clinical outcomes Spine 2005;30:1565-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zigler J, Delamarter R, Spivak JM, Linovitz RJ, Danielson GO III, Haider TT, et al. Results of the prospective, randomized, multicenter Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption study of the ProDisc-L total disc replacement versus circumferential fusion for the treatment of 1-level degenerative disc disease. Spine 2007;32:1155-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyer RD, McAfee PC, Banco RJ, Bitan FD, Cappuccino A, Geisler FH, et al. Prospective, randomized, multicenter Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption study of lumbar total disc replacement with the CHARITE artificial disc versus lumbar fusion: five-year follow-up. Spine J 2009;9:374-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg S, Tullberg T, Branth B, Olerud C, Tropp H. Total disc replacement compared to lumbar fusion: a randomised controlled trial with 2-year follow-up. Eur Spine J 2009;18:1512-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson JN, Waddell G. Surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;4:CD001352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van den Eerenbeemt KD, Ostelo RW, van Royen BJ, Peul WC, van Tulder MW. Total disc replacement surgery for symptomatic degenerative lumbar disc disease: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Spine J 2010;19:1262-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masharawi Y, Kjaer P, Bendix T, Manniche C, Wedderkopp N, Sorensen JS, et al. The reproducibility of quantitative measurements in lumbar magnetic resonance imaging of children from the general population. Spine 2008;33:2094-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modic MT, Steinberg PM, Ross JS, Masaryk TJ, Carter JR. Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology 1988;166:193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aprill C, Bogduk N. High-intensity zone: a diagnostic sign of painful lumbar disc on magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Radiol 1992;65:361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luoma K, Riihimaki H, Luukkonen R, Raininko R, Viikari-Juntura E, Lamminen A. Low back pain in relation to lumbar disc degeneration. Spine 2000;25:487-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairbank JCTM, Pynsent PBP. The Oswestry disability index. Spine 2000;25:2940-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grotle M, Brox JI, Vollestad NK. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Norwegian versions of the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire and the Oswestry disability index. J Rehabil Med 2003;35:241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473-83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JE Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine 2000;25:3130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Euroquol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci 1974;19:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 1993;52:157-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, Shoor S, Holman HR. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1989;32:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostelo RW. Clinically important outcomes in low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2005;19:593-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strand LI, Moe-Nilssen R, Ljunggren AE. Back performance scale for the assessment of mobility-related activities in people with back pain. Phys Ther 2002;82:1213-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prolo DJ, Oklund SA, Butcher M. Toward uniformity in evaluating results of lumbar spine operations. A paradigm applied to posterior lumbar interbody fusions. Spine 1986;11:601-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A. The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 2003;12:12-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ 1998;317:1309-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guyatt GH, Juniper EF, Walter SD, Griffith LE, Goldstein RS. Interpreting treatment effects in randomised trials. BMJ 1998;316:690-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairbank JC. Use and abuse of Oswestry disability index. Spine 2007;32:2787-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nachemson A. Chronic pain—the end of the welfare state? Qual Life Res 1994;3(suppl 1):S11-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pauza KJ, Howell S, Dreyfuss P, Peloza JH, Dawson K, Bogduk N. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of intradiscal electrothermal therapy for the treatment of discogenic low back pain. Spine J 2004;4:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freeman BJ, Fraser RD, Cain CM, Hall DJ, Chapple DC. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial: intradiscal electrothermal therapy versus placebo for the treatment of chronic discogenic low back pain. Spine 30:2369-77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, Wark JD, Mitchell P, Wriedt C, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med 2009;361:557-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rousing R, Hansen KL, Andersen MO, Jespersen SM, Thomsen K, Lauritsen JM. Twelve-months follow-up in forty-nine patients with acute/semiacute osteoporotic vertebral fractures treated conservatively or with percutaneous vertebroplasty: a clinical randomized study. Spine 2010;35:478-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mannion AF, Junge A, Elfering A, Dvorak J, Porchet F, Grob D. Great expectations: really the novel predictor of outcome after spinal surgery? Spine 2009;34:1590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Skinner JS, Hanscom B, Tosteson AN, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort. JAMA 2006;296:2451-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Hanscom B, Tosteson AN, Blood EA, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2257-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peul WC, van Houwelingen HC, van den Hout WB, Brand R, Eekhof JA, Tans JT, et al. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2245-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inamasu J, Guiot BH. Vascular injury and complication in neurosurgical spine surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148:375-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ianuzzi A, Schmier J, Todd L, Isaza J, et al. National revision burden for lumbar total disc replacement in the United States: epidemiologic and economic perspectives. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010; published online 26 Feb. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Putzier M, Funk JF, Schneider SV, Gross C, Tohtz SW, Khodadadyan-Klostermann C, et al. Charite total disc replacement—clinical and radiographical results after an average follow-up of 17 years. Eur Spine J 2006;15:183-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lemaire JP, Carrier H, Sariali E, Skalli W, Lavaste F. Clinical and radiological outcomes with the Charite artificial disc: a 10-year minimum follow-up. J Spinal Disord Tech 2005;18:353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tropiano P, Huang RC, Girardi FP, Cammisa FP Jr, Marnay T. Lumbar total disc replacement. Seven to eleven-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:490-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.David T. Long-term results of one-level lumbar arthroplasty: minimum 10-year follow-up of the CHARITE artificial disc in 106 patients. Spine 2007;32:661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McAfee PC, Geisler FH, Saiedy SS, Moore SV, Regan JJ, Guyer RD, et al. Revisability of the CHARITE artificial disc replacement: analysis of 688 patients enrolled in the US IDE study of the CHARITE artificial disc. Spine 2006;31:1217-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siepe CJ, Zelenkov P, Sauri-Barraza JC, Szeimies U, Grubinger T, Tepass A, et al. The fate of facet joint and adjacent level disc degeneration following total lumbar disc replacement: a prospective clinical, x-ray, and magnetic resonance imaging investigation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:1991-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siepe CJ, Mayer HM, Wiechert K, Korge A. Clinical results of total lumbar disc replacement with ProDisc II: three-year results for different indications. Spine 2006;31:1923-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guyer RD, Siddiqui S, Zigler JE, Ohnmeiss DD, Blumenthal SL, Sachs BL, et al. Lumbar spinal arthroplasty: analysis of one center’s twenty best and twenty worst clinical outcomes. Spine 2008;33:2566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria, compliance with randomisation, and drop-outs

Appendix 2: Rehabilitation intervention

Appendix 3: Supplementary tables