Abstract

Passive intervertebral motion (PIVM) assessment is a characterizing skill of manual physical therapists (MPTs) and is important for judgments about impairments in spinal joint function. It is unknown as to why and how MPTs use this mobility testing of spinal motion segments within their clinical reasoning and decision-making. This qualitative study aimed to explore and understand the role and position of PIVM assessment within the manual diagnostic process. Eight semistructured individual interviews with expert MPTs and three subsequent group interviews using manual physical therapy consultation platforms were conducted. Line-by-line coding was performed on the transcribed data, and final main themes were identified from subcategories. Three researchers were involved in the analysis process. Four themes emerged from the data: contextuality, consistency, impairment orientedness, and subjectivity. These themes were interrelated and linked to concepts of professionalism and clinical reasoning. MPTs used PIVM assessment within a multidimensional, biopsychosocial framework incorporating clinical data relating to mechanical dysfunction as well as to personal factors while applying various clinical reasoning strategies. Interpretation of PIVM assessment and subsequent decisions on manipulative treatment were strongly rooted within practitioners’ practical knowledge. This study has identified the specific role and position of PIVM assessment as related to other clinical findings within clinical reasoning and decision-making in manual physical therapy in The Netherlands. We recommend future research in manual diagnostics to account for the multivariable character of physical examination of the spine.

Keywords: Clinical reasoning, Diagnostic process, Manual physical therapy, Spinal disorders

Introduction

From early traditional international concepts in manual physical therapy, an emphasis has been placed on the diagnostics, treatment, and evaluation of joint function, especially of joints of the spine and pelvis.1–4 A characterizing feature of functional diagnostics is the use of passive joint movements of spinal motion segments for making judgments about the quality and quantity of segmental intervertebral joint function.1 This passive intervertebral motion (PIVM) assessment is believed to play an important role within diagnostic clinical reasoning leading to classification of patients and treatment decisions.5

Systematic reviews have consistently shown low inter-examiner reliability for PIVM assessment.6–11 In addition, the methodological quality of studies reviewed was found to be poor and the studies did not satisfy criteria for external validity, disallowing generalization of the results to clinical practice.11 Most studies included non-representative participants, i.e. individuals who were not indicated to undergo PIVM assessment. Moreover, PIVM assessment has only been investigated as an independent factor within functional diagnostics, which may not be reflective of daily practice. However, it is unknown exactly what constitutes daily manual physical therapy practice with respect to the role of PIVM assessment within clinical decision-making in patients with spine-related disorders.

Recent surveys revealed that manual physical therapists (MPTs) believe that findings from PIVM assessment, together with the patient’s history and other findings from the physical examination, are important for deciding on manual physical therapy as a treatment option and that they are confident in their diagnostic conclusions drawn from PIVM assessment.12,13 However, to date, an in-depth investigation into why and how MPTs use PIVM assessment within their daily clinical reasoning has not been conducted.

This qualitative interview study was undertaken to explore why and how MPTs use PIVM assessment within their clinical reasoning and decision-making. We hypothesized that its results could help guide the design and conduct of future studies into manual diagnostics leading to improved external validity of research results.

Methods

Study design

Data collection was based on individual and group interviews, which have the advantage over paper-based cases of increasing the likelihood of revealing participants’ reasoning as used in practice as opposed to their espoused theory.14

Objective/procedure

This qualitative study aimed to explore and understand the role and position of PIVM assessment within the manual diagnostic process. We appealed to the experiential knowledge of MPTs, expert teachers in manual physical therapy as well as clinicians, as a primary source of data collection. A purposive sample of 11 MPTs was invited via email and a subsequent telephone call to participate in an individual interview. These therapists were all regarded as leading authorities within manual physical therapy covering the range of education programs as acknowledged by the Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF). Subsequently, nine groups of MPTs constituting consultation platforms were invited to participate in group interviews. These platforms are part of the quality assurance program of the KNGF and generally consist of up to 15 therapists discussing quality improvement and assurance.15 The majority of the platforms were established in 2002 and participation by therapists is geographically organized.

Participants

Three expert therapists (one with a Maitland background, one orthopedic manual therapist, and one from the Master’s program in Manual Therapy at the Free University of Brussels, Belgium) declined to participate in the individual interviews because of time constraints. Characteristics of the remaining eight participating experts are summarized in Table 1. The majority of the participants were highly experienced in practicing as well as in teaching manual physical therapy.

Table 1. Demographic and professional characteristics of expert manual physical therapists participating in individual interviews (n = 8).

| Participant | Gender | Age (years) | Experience in MPT practice (years) | Experience in MPT teaching (years) | MPT background |

| 1 | m | 42 | 14 | 0 | SOMT |

| 2 | m | 58 | 30 | 30 | SOMT |

| 3 | m | 51 | 22 | 21 | SOMT |

| 4 | m | 47 | 16 | 16 | SOMT |

| 5 | m | 52 | 18 | 18 | VUB |

| 6 | m | 33 | 8 | 8 | VUB |

| 7 | f | 49 | 22 | 15 | Maitland |

| 8 | m | 56 | 29 | 27 | OMT |

Note: f = female; m = male; MPT = manual physical therapy; OMT = orthopedic manual therapy; SOMT = Stichting Opleiding Musculoskeletale Therapie (Educational Center for Musculoskeletal Therapies); VUB = Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Free University of Brussels), Master Manual Therapy, Belgium.

Four platforms agreed to participate in group interviews of which three were initially used for data collection. Of the remaining five platforms, three could not participate due to lack of time and two did not respond to our invitation. Characteristics of the three participating groups are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Demographic and professional characteristics of manual physical therapy consultation platforms participating in group interviews (n = 3).

| Group | Number of participants | Gender (males) | Age* (years) | Experience in MPT practice* (years) | MPT background |

| 1 | 8 | 7 | 37.5 (31–49) | 5.5 (3–13) | SOMT (n = 8) |

| 2 | 11 | 6 | 48 (37–63) | 12 (5–23) | SOMT (n = 5), OMT (n = 5), MT Utrecht (n = 1) |

| 3 | 8 | 7 | 45 (40–55) | 13 (8–16) | SOMT (n = 8) |

Note: MPT = manual physical therapy; OMT = orthopedic manual therapy; SOMT = Stichting Opleiding Musculoskeletale Therapie (Educational Center for Musculoskeletal Therapies).

*Presented as median (minimum–maximum).

Data collection

Individual interviews with eight experts took place between November 2007 and April 2008. Interviews were conducted by the principal researcher (EvT), who is an experienced manual physical therapist and trained as a qualitative researcher. Interviews were semistructured and an interview guide was used that contained the following topics exploring key aspects of clinical reasoning within manual diagnostics: (1) the use of PIVM assessment as related to findings from patient’s history and other clinical tests; (2) the interpretation of clinical findings from PIVM assessment; (3) the role of PIVM assessment in selecting manual physical therapy as a treatment option; (4) required knowledge and skills for using and interpreting PIVM assessment; (5) the role of PIVM assessment within a biopsychosocial approach; and (6) the importance of PIVM assessment for the identity of manual physical therapy. Interviews were audio-recorded and the interviewer made additional notes of specific quotes and observations. Interview time ranged from 50 to 75 minutes. The purpose of these interviews was to cover a wide range of perspectives on the role and position of PIVM assessment within clinical reasoning and decision-making across various manual physical therapy approaches. It was decided in advance that a fixed number of interviews would suffice. Between interviews, the interviewer repetitively reflected on his role as an interviewing manual physical therapist in order to reduce researcher bias. In addition, he was peer-reviewed by a second researcher (FvH), who specifically addressed such issues as leading questions and interviewer’s prejudice. Member checking was performed to enhance the validity of the raw transcribed material first and, subsequently, of analysed data as well.

Group interviews took place between June 2008 and September 2008. EvT conducted the interviews using a topic list similar to the one used in the individual interviews. Elicitation exercises are helpful in focusing the groups’ attention on the study topic and allow comparative analysis.16 A ranking exercise was used to facilitate participants’ thinking about using PIVM assessment within their reasoning in a case of non-specific mechanical neck pain in which few demographic (age and gender) and clinical data (duration of complaints and localization of pain) were given. In this exercise, participants were requested to reach consensus about the order in which they would apply clinical examination tests with specific attention to the role of PIVM assessment. The therapists were encouraged to share how they would think and act in this case in daily practice instead of how they should think and act. Interviews were audio-recorded and the interviewer made additional notes of specific quotes, observations, and interaction between participants. Each interview lasted 90 minutes. The purpose of these interviews was to test whether themes and categories from analysed individual interviews could be identified in groups of therapists representing daily practice in manual physical therapy. Saturation of data was used to determine the number of interviews required. FvH peer reviewed the interview process.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their anonymity was ensured by allocating numbers instead of using their names during analysis. In addition, confidentiality of data was ensured.

Data analysis

All taped interview data were transcribed verbatim. Analysis took place after every interview. Line-by-line open coding was performed by the principal investigator and identified codes were classified into categories. Two researchers (EvT and FvH) discussed the labeling of categories until agreement was reached. During the process of labeling and analysis, both researchers independently explored the data in search of deviant cases and disconfirming data. Through discussion and consensus, emerging final main themes were agreed upon by three researchers (EvT, TP, and FvH). Subsequently, themes were further integrated by incorporating a sociological theory of professionalism17 as well as a biopsychosocial, collaborative hypothesis-oriented model of clinical reasoning as described by Jones et al.18 Quotes were selected illustrating each category and translated with the help of a native speaker. Throughout the research process, EvT kept a logbook and made memos to describe changes in methods and decisions regarding data collection and analysis.

Results

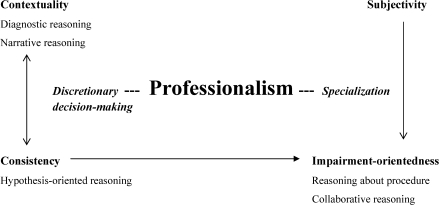

From the analysis of the individual interview data, four themes emerged: contextuality, consistency, impairment orientedness, and subjectivity. These themes were, to a large extent. corroborated by findings from the group interviews. Figure 1 illustrates how the four themes are interrelated and are linked to various types of clinical reasoning strategies. Professionalism acts as a covering main theme. Below, a more detailed description of the results is given for the individual and group interviews separately and themes are illustrated by quotes.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the relationship between the four themes (contextuality, consistency, subjectivity, and impairment orientedness) emerging from our interview data analysis with each other, containing elements of certain strategies for clinical reasoning as described by Jones et al.,18 as well as two key elements of professionalism, discretionary decision-making and specialization.17

Individual interviews

Throughout the interviews, expert MPTs demonstrated a high level of concern by enthusiastically expressing their firm visions on manual physical therapy profession and education. Afterwards, member checking rounds did not generate additional comments.

Contextuality

Respondents argued that the indication for using PIVM assessment is dictated by findings from the patient’s history as well as from other clinical tests. They believed that the patient’s personal perspectives and characteristics are important for deciding on PIVM assessment besides information about movement-related impairments and activity limitations. Within this multidimensional context, the patient’s history was a decisive source of information that guided further collection of clinical data and, more specifically, the use of PIVM assessment, which is illustrated by a statement from Respondent 2 (R2):

So, in general, to identify signs from patient’s history which would indicate the use of passive segmental motion examination, that patient HAS to have told me ‘I have restricted activities, like looking over my shoulder or bending forward,’ such that make me consider the existence of impairments in mobility. (R2)

In addition, other motion examination findings are considered before using PIVM assessment; however, PIVM assessment seems to be used routinely.

To me, when it is a non-specific problem, and it is a mechanical one, I will definitely use it [PIVM assessment] […] ALWAYS. (R4)

From the previous, it may appear that deciding on PIVM assessment, although dependent on findings from the patient’s history and other clinical tests, is predominantly led by mechanical arguments. However, all eight experts did reason about an indication for using PIVM assessment from other perspectives as well. In particular, they explicitly included personal factors related to the patient’s behavior and beliefs in their decision-making, thereby adopting a biopsychosocial approach to manual diagnostics. Among other factors mentioned were duration of complaints, pain intensity, muscular defense, physical fitness and fatigue, posture and working positions, and accompanying neurogenic complaints.

When I’m suspicious, after taking the patient’s history, of other aspects contributing to movement dysfunction, like in the case of chronic benign pain, then there is NO reason to perform passive segmental motion examination. (R3)

Consistency

Interviewees stated that they used PIVM assessment during manual examination in order to check and confirm earlier clinical findings. Implicitly, they generated hypotheses about correlations between what they were told by patients and what they found during physical examination. PIVM assessment, then, plays a role in confirming the presence or absence of impairments in spinal joint motion that can be related to the patient’s pain, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. Respondent 1, however, was reticent in giving credence to the significance of the findings from PIVM assessment because he took into account the lack of scientific evidence for PIVM assessment. This issue of the importance of available evidence for PIVM assessment was subsequently added as a topic during the remaining interviews. Experts had differing opinions in this respect. Some (R3 and R4) applied a very pragmatic approach. For example,

I am aware of the lack of evidence. It just isn’t there but that doesn’t influence my daily practice […] I am convinced that whatever we do we should continue like we are […] waiting for evidence just takes too long. It’s a shame that inevitably sometimes you do things that are not helpful […] so be it. (R4)

By tailoring diagnostics to individual patients, therapists employ a high level of autonomy in their reasoning and decision-making. This discretionary decision-making is believed to be a crucial element of a manual profession.17 Data supporting the two themes of contextuality and consistency imply a certain order in conducting tests during manual examination. Indeed, all respondents admitted to a more or less fixed order in which PIVM assessment comes in later or even last. It was decided to explore this issue further as a main focus in the group interviews.

Subjectivity

Subjectivity refers to the lack of objective measures for interpreting and classifying clinical findings from PIVM assessment. Variation in interpretation of quality and quantity of intervertebral motion is an inevitable consequence of the therapists’ own clinical experience from which their individual frame of reference is built.

Manual therapy is a craft really that you have to learn and that is built up through experience, I think. I can read about it but learning to interpret test findings I think you have to learn on the job. (R6)

One respondent (R8), however, stated that he used PIVM assessment as an objective measure by comparing its findings with ‘real’ subjective ones, namely, those reported by patients themselves, and he believed that this is actually a strong feature of manual physical therapy.

The experts recognized that lack of uniformity in criteria for judging impairments of spinal motion segments hinders the profession’s transparency towards patients and referrers, and they explicitly recommended, most of them being teachers, thorough training of students by experienced practitioners in order to reach more consensus on how to judge and express impairments of the functions of spinal motion segments.

Impairment orientedness

The presence of impairments in spinal joint function among consistent clinical findings guided the decision to select manual physical therapy, either mobilizations or manipulations, as a treatment option. The experts fully agreed that the skills for diagnosing and treating spinal joint motion impairments are a distinct feature of manual physical therapy and as such separate the manual physical therapy competency domain from that of physical therapy. Manual physical therapy has a strong focus on knowledge of joint arthrokinematics and osteokinematics and on impairments of joint function and, as treatment is aimed at individual spinal segmental levels, PIVM assessment is necessary for decisions about which motion segment to treat and how to treat it. Respondents 1 and 5, however, took a critical view, reflecting on the limitations of this narrow focus for the profession:

R5: I believe manual therapy suffers from an inflated ego.

Interviewer: What do you mean?

R5: The simplifying of the patient’s complaints into segmental dysfunctions and the assumption that removing these dysfunctions will automatically lead to the patient’s recovery.

It was striking how even expert teachers in manual physical therapy were not able to put into words how and which clinical findings from PIVM assessment would lead to a choice for either mobilization or manipulation of a joint. Type of end-feel, amount of restricted motion, number of motion segments involved, level of patient’s pain intensity, but also characteristics of the patient and his or her former experience with manual physical therapy, were factors considered in deciding on a manipulative intervention. In conclusion, the choice for the type of intervention seems to be multidimensionally determined and influenced by therapists’ own subjective preferences and experience as part of their individual practical knowledge.

Group interviews

In the given case of non-specific mechanical neck pain, all three groups of therapists reached consensus on the sequence of testing procedures for manual examination. Moreover, there was complete agreement on this ordering between groups. After history-taking and inspection, active motion assessment, passive regional motion assessment, and passive segmental motion assessment are applied respectively, which, depending on findings and not always during the same first session, could be followed by muscle function examination and neurodynamic evaluation. The groups also indicated that the decision for applying PIVM assessment depends on earlier clinical findings, either related to the mechanical problem or to the patient’s external or personal factors. Although participants admitted to using PIVM assessment for checking and confirming the patient’s complaints, they had difficulty explaining how this relates to the position of this assessment following other tests. The following fragment, containing a discussion between four participants (P) in Group 3, illustrates how strongly education prescribes acting by professionals in practice:

Interviewer: Why is passive intervertebral motion assessment positioned last in line?

P3: That’s what we are used to doing.

P6: In a pyramid in which you start broadly with history-taking, you enter some sort of funnel model and you go on getting more specific, and segmental motion assessment is as specific as you can get.

P1: It is an automatic activity of steps you pass through as a rule.

P7: Yeah, I believe that’s what we’ve been taught.

Interviewer: How come?

P3: That originates from the structure that is handed to you during training.

Participants in all groups could not agree on whether PIVM assessment should be judged primarily on function (i.e. mobility or stability) or on pain provocation and, even more challenging, when judged on both, which judgment should come first during testing. It was notable that participants in Group 1, being younger and more recently trained, perceived their reasoning skills as more important than their physical examination skills when asked about the additional value of manual physical therapy as compared to physical therapy. On the other hand, the more experienced therapists in Groups 2 and 3 expressed a more patient-centered approach by consciously using findings from PIVM assessment for educating patients and involving these findings in choosing and evaluating patient management. Given the similarities of opinions and disagreements across the three groups of practitioners, we decided that the remaining fourth available consultation platform would not be used for further exploration.

Discussion

This qualitative study has been the first to shed light on the mental processes of clinical reasoning and decision-making by MPTs as related to PIVM assessment and has provided level 5 evidence for the role and position of this test procedure within the manual diagnostic process.19 Identifying the role and position of a test within a diagnostic strategy helps design studies to evaluate the diagnostic value of tests.20 In diagnostic research, a stepwise evaluation of tests is increasingly proposed to consider not only the test’s technical accuracy, but also its place in the clinical pathway and, eventually, its impact on patient outcomes.21 We found that PIVM assessment is positioned, albeit sometimes more or less routinely, as an ‘add-on’ test after history-taking, visual inspection, and active and passive motion examination. Add-on tests are generally used to increase the sensitivity or specificity of a diagnostic strategy in order to improve treatment selection.20,22 Increased sensitivity through adding PIVM assessment could identify patients with segmental joint hypomobility newly indicated for, say, manipulative treatment in the absence of active motion restrictions or activity limitations. Increased specificity limits the number of false-positive diagnostic conclusions and would confirm an indication for treatment in those patients already testing positive on preceding motion examination and activity limitations. Research results are in favor of the latter, demonstrating higher levels of specificity for spinal motion segment testing as compared to its sensitivity.23–27 However, to date, research on PIVM assessment can be regarded as test research following a single-test or univariable approach, thus neglecting the multivariable character of diagnostics as opposed to diagnostic research.28 Our data support a multivariable, biopsychosocial approach to research into manual diagnostics in general and PIVM assessment in particular. de Hertogh et al.29 showed improved accuracy of manual examination of cervical motion segments when clustered with results on pain intensity and medical history, and claimed that this multidimensional approach better resembles practice. The reliability and, if possible, accuracy of either add-on diagnostic strategy as a whole, should be the focus of future research including representative patients who are indicated to undergo PIVM assessment and potentially yielding study results more reflective of diagnostic pathways used in daily practice. A proposed research objective could be to determine inter-examiner reliability of intervertebral mobility testing of impaired motion segments, identified through reliable pain provocation tests,9 in patients with either spine-related complaints or extremity disorders indicated to undergo spinal examination after testing negative on ‘yellow flags’ but showing active range of motion restrictions and activity limitations during history-taking and physical examination. At some point, studies inevitably need to incorporate patient outcomes while evaluating test-plus-treatment strategies.22

Previous research investigating clinical reasoning in the domain of musculoskeletal physical therapy focused on exploring characteristics of expert practitioners and indicated the use of various diagnostic reasoning processes, like pattern recognition, hypothetico-deductive reasoning, and patient-centered, collaborative reasoning.30–38 MPTs indeed apply a hypothetico-deductive approach in their encounters with patients.38 These results seem in contrast with findings from research in doctors showing a pattern recognition mode of reasoning as clinical expertise grows.39 However, it is now recognized that clinicians, often unconsciously, use multiple combined strategies of reasoning to solve clinical problems.40 Already in undergraduate students, conceptualizations of clinical reasoning in musculoskeletal physical therapy ranged from relatively simple to increasingly complex but mixed forms of reasoning.41

Our respondents, expert teachers as well as practicing clinicians, could not agree on which clinical finding is indicative for dysfunctions of spinal motion segments or directive for decisions on manual treatment. Maher et al.42 showed that MPTs conceptualize spinal stiffness in an individual, multidimensional manner, and joint and tissue characteristics are described in qualitative terms. The highly subjective interpretation of PIVM assessment is embedded within and contributes to the practical craft knowledge characterizing the profession.43 However, it may also account for its low reliability.42 de Hertogh et al.29 chose a more pragmatic approach by marking manual examination as positive when at least any two out of three criteria (mobility, end-feel, and pain provocation) were met. They showed improved reliability and high specificity of manual examination in neck pain patients confirming earlier findings by Jull et al.5,29,44 Combined interpretation of findings from PIVM assessment, clustered with other signs and symptoms, looks to be a promising approach to future research on the reliability and diagnostic accuracy of manual diagnostics leading to transferable results.

Dutch MPTs believe that PIVM assessment is important for deciding on a treatment strategy.13 Authors have questioned the clinical usefulness and necessity of identifying impairments of joint mobility at specified spinal levels in order to make treatment decisions.45–48 Seffinger et al.9 concluded that assessing regional range of spinal motion was more reliable than segmental examination. However, Chiradejnant et al.49 showed a greater reduction in pain intensity when mobilization was applied to the symptomatic lumbar motion segment rather than to a randomly assigned level. Despite the limited evidence for a spinal motion segment approach, Dutch MPTs derive their status as specialists in the care of spine-related health problems, as opposed to non-specialized physical therapists, in great part from their skill to address manual diagnostics and treatment to individual spinal motion segments.

Finally, the large amount of agreement between and among our respondents was remarkable. Despite the fact that therapists trained in the largest manual physical therapy educational institute in The Netherlands (SOMT: Stichting Opleiding Musculoskeletale Therapie) were overrepresented in both samples, our expert teachers still had different educational backgrounds representing different manual physical therapy approaches. It may be concluded that the various concepts of manual physical therapy still share many common sources of knowledge dating back to the early origins of the profession.50 From their Delphi study among US manual therapy educators, Sizer et al.51 identified consensual skill sets associated with competent application of orthopedic manual therapy despite the disparate backgrounds of respondents. Manual joint assessment was contained in the majority of stand-alone descriptor statements.51 In addition, Maher et al.42 found similar results between US and Australian manipulative physical therapists for the conceptualization of spinal stiffness.

Limitations

Although interviews are the most common method for producing qualitative data, a shortcoming is that they provide access to what people say they think and do, not what they actually think and do.52 Furthermore, the principal expert investigator was the conductor of all interviews. Collected data could have been shaped by the influence of his prior assumptions and experience, and these could have introduced personal and intellectual biases into the results. However, we believe that using an explicit topic list during the interviews and taking a reflexive position towards data collection and analysis, including peer review, have sufficiently protected against biased interpretation of results by the conductor. With respect to the external validity of our results, we point to the specific system for manual physical therapy education in The Netherlands, where manual physical therapy is considered a post-graduate (non-university) specialization following entry-level bachelor physical therapy education and education programs that meet the Educational Standards of the International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Therapists.53 We fully acknowledge that the Dutch educational framework may strongly differ from that in other countries, like the USA, Canada, and Australia, in which specific knowledge and manual skills for diagnosing and treating spinal segmental joint impairments is entry-level. Therefore, our results, based on the verbal expressions of our respondents, may not always apply beyond the Dutch population of MPTs. Finally, we included a purposive sample of expert MPTs to cover the range of different perspectives on the study subject from the various manual physical therapy educational programs acknowledged for registration in The Netherlands. However, we did not aim for data saturation in this part of the study and, therefore, we could not search for deviant cases and contradicting opinions further within every single approach.

Conclusions

This study has provided insight into why and how PIVM assessment is used by Dutch MPTs within their clinical reasoning and decision-making. In addition, the specific role and position of mobility testing of spinal motion segments, as related to patient’s history and other clinical tests, has been explored. We recommend future research into manual diagnostics to account for the multivariable, biopsychosocial, and hypothesis-oriented character of physical examination of the spine and of PIVM assessment in particular.

References

- 1.Farrell JP, Jensen GM. Manual therapy: a critical assessment of role in the profession of physical therapy. Phys Ther. 1992;72:843–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maher C, Latimer J. Pain or resistance: the manual therapists’ dilemma. Aust J Physiother. 1992;38:257–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NVMT (Dutch Association for Manual Therapy) Professional competence profile for the manual therapist (document on the Internet). Amersfoort: NVMT; 2005 (cited 2009 Jan 31). Available from: http://www.nvmt.nl/upload/BCP.ENG.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Ravensberg CD, Oostendorp RA, van Berkel LM, Scholten-Peeters GG, Pool JJ, Swinkels RA, et al. Physical therapy and manual physical therapy: differences in patient characteristics. J Man Manip Ther. 2005;13:113–24 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jull G, Treleaven J, Versace G. Manual examination: is pain provocation a major cue for spinal dysfunction? Aust J Physiother. 1994;40:159–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haneline MT, Cooperstein R, Young M, Birkeland K. Spinal motion palpation: a comparison of studies that assessed intersegmental end feel vs. excursion. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31:616–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hestbœk L, Leboeuf-Yde C. Are chiropractic tests for the lumbo-pelvic spine reliable and valid? A systematic critical literature review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23:258–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.May S, Littlewood C, Bishop A. Reliability of procedures used in the physical examination of non-specific low back pain. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seffinger MA, Najm WI, Mishra SI, Adams A, Dickerson VM, Murphy LS, et al. Reliability of spinal palpation for diagnosis of back and neck pain: a systematic review of the literature. Spine. 2004;29:E413–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stochkendahl MJ, Christensen HW, Hartvigsen J, Vach W, Haas M, Hestbæk L. Manual examination of the spine: a systematic critical literature review of reproducibility. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29:475–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Trijffel E, Anderegg Q, Bossuyt PM, Lucas C. Inter-examiner reliability of passive assessment of intervertebral motion in the cervical and lumbar spine: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2005;10:256–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbott JH, Flynn TW, Fritz JM, Hing WA, Reid D, Whitman JM. Manual physical assessment of spinal segmental motion: Intent and validity. Man Ther. 2009;14:36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Trijffel E, Oostendorp RA, Lindeboom R, Bossuyt PM, Lucas C. Perceptions and use of passive intervertebral motion assessment of the spine: a survey of Dutch physiotherapists specializing in manual therapy. Man Ther. 2009;14:243–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Argyis C, Schön D. Theory in practice: increasing professional effectiveness. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1974 [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Wees PJ, Hendriks EJ, Veldhuizen RJ. Quality assurance in the Netherlands: from development to implementation and evaluation. Dutch J Phys Ther. 2003;113:3–6 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colluci E. Focus groups can be fun: the use of activity-oriented questions in focus group discussions. Qual Health Res. 2007;17:1422–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freidson E. Professionalism: the third logic. Oxford: Blackwell; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones MA, Jensen G, Edwards I. Clinical reasoning in physiotherapy. Higgs J, Jones MA, Loftus S, Christensen N, editors.Heinemann Clinical reasoning in the health professions. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier/Butterworth; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.CEBM (Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine). Levels of evidence. Oxford: CEBM; 2005. (cited 2009 May 17). Available from: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o 1025 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bossuyt PM, Irwig L, Craig J, Glasziou P. Comparative accuracy: assessing new tests against existing diagnostic pathways. BMJ. 2006;332:1089–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Bruel A, Cleemput I, Aertgeerts B, Ramaekers D, Buntinx F. The evaluation of diagnostic tests: evidence on technical and diagnostic accuracy, impact on patient outcome and cost-effectiveness is needed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:1116–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lord SJ, Irwig L, Bossuyt PM. Using the principles of randomized controlled trial design to guide test evaluation. Med Decis Making. 2009;29:E1-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbott JH, McCane B, Herbison P, Moginie G, Chapple C, Hogarty T. Lumbar segmental instability: a criterion-related validity study of manual therapy assessment. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2005;6:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fritz JM, Whitman JM, Childs JD. Lumbar spine segmental mobility assessment: an examination of validity for determining intervention strategies in patients with low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2005;8:1745–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall TM, Robinson KW, Fujinawa O, Akasaka K, Pyne EA. Intertester reliability and diagnostic validity of the cervical flexion-rotation test. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31:293–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphreys BK, Delahaye M, Peterson CK. An investigation into the validity of cervical spine motion palpation using subjects with congenital block vertebrae as a ‘gold standard’. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2004;5:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogince M, Hall T, Robinson K, Blackmore AM. The diagnostic validity of the cervical flexion-rotation test in C1/2-related cervicogenic headache. Man Ther. 2007;12:256–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moons KG, Biesheuvel CJ, Grobbee DE. Test research versus diagnostic research. Clin Chem. 2004;50:473–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Hertogh WJ, Vaes PH, Vijverman V, de Cordt A, Duquet W. The clinical examination of neck pain patients: the validity of a group of tests. Man Ther. 2007;12:50–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doody C, McAteer M. Clinical reasoning of expert and novice physiotherapists in an outpatient orthopaedic setting. Physiotherapy. 2002;88:258–68 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edwards I, Jones M, Carr J, Braunack-Mayer A, Jensen GM. Clinical reasoning strategies in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2004;84:312–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen GM, Shepard KF, Hack LM, Gwyer J. Attribute dimensions that distinguish master and novice physical therapy clinicians in orthopaedic settings. Phys Ther. 1992;72:711–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen GM, Gwyer J, Shepard KF, Hack LM. Expert practice in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2000;80:28–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King CA, Bithell C. Expertise in diagnostic reasoning: a comparative study. Int J Ther Rehabil. 1998;5:78–87 [Google Scholar]

- 35.May S, Greasley A, Reeve S, Withers S. Expert therapists use specific clinical reasoning processes in the assessment and management of patients with shoulder pain: a qualitative study. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:261–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Payton OD. Clinical reasoning process in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 1985;65:924–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Resnik L, Jensen GM. Using clinical outcomes to explore the theory of expert practice physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2003;83:1090–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rivett DA, Higgs J. Hypothesis generation in the clinical reasoning behavior of manual therapists. J Phys Ther Educ. 1997;11:40–45 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kempainen RR, Migeon MB, Wolf FM. Understanding our mistakes: a primer on errors in clinical reasoning. Acad Med. 2003;25:177–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowen JL. Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2217–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendrick P, Bond C, Duncan E, Hale L. Clinical reasoning in musculoskeletal practice: students’ conceptualizations. Phys Ther. 2009;89:430–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maher CG, Simmonds M, Adams R. Therapists’ conceptualization and characterization of the clinical concept of spinal stiffness. Phys Ther. 1998;78:289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Titchen A, Ersser SJ. The nature of professional craft knowledge. Higgs J, Titchen A, editors. Practice knowledge and expertise in the health professions. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jull G, Zito G, Trott P, Potter H, Shirley D, Richardson C. Inter-examiner reliability to detect painful upper cervical joint dysfunction. Aust J Physiother. 1997;43:125–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fritz JM, Piva SR, Childs JD. Accuracy of the clinical examination to predict radiographic instability of the lumbar spine. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:743–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haas M, Groupp E, Panzer D, Partna L, Lumsden S, Aickin M. Efficacy of cervical endplay assessment as an indicator for spinal manipulation. Spine. 2003;28:1091–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huijbregts PA. Spinal motion palpation: a review of reliability studies. J Man Manip Ther. 2002;10:24–39 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Troyanovich SJ, Harrison DD. Motion palpation: it’s time to accept the evidence. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;21:568–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chiradejnant A, Latimer J, Maher CG, Stepkovitch N. Does the choice of spinal level treated during posteroanterior (PA) mobilisation affect treatment outcome? Physiother Theory Pract. 2002;18:165–74 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pettman E. A history of manipulative therapy. J Man Manip Ther. 2007;15:165–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sizer PS, Felstehausen V, Sawyer S, Dornier L, Matthews P, Cook C. Eight critical skill sets required for manual therapy competency: a Delphi study and factor analysis of physical therapy educators of manual therapy. J Allied Health. 2007;36:30–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London: Sage; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 53.IFOMT (International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Therapists). Educational Standards in Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapy. Part A: Educational standards. Auckland: IFOMT; 2008 (cited 2009 Jan 31). Available from: http://www.ifomt.org/pdf/IFOMT_Education_Standards_and_International_Monitoring_20080611.pdf. [Google Scholar]