Abstract

In the absence of effective antiretroviral therapy, infection with clade B human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) infection commonly progresses to AIDS dementia. However, in India, where clade C infection is most prevalent, severe cognitive impairment due to HIV-1 is reported to be less prevalent. The Tat protein of HIV-1, which is released from HIV-1-infected macrophages, is thought to play a major role in the disruption of neuronal function as well as in the infiltration of macrophages associated with advanced neuropathogenesis. Clade B Tat is excitotoxic to hippocampal neurons by potentiating N-methyl-d-aspartate-induced currents of the zinc-sensitive NR1/NR2A N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor in a zinc-binding-dependent mechanism. This study characterizes the zinc-binding properties of clade C Tat protein. Using ultraviolet spectroscopy and the Ellman reaction, we show that clade C Tat protein binds just one zinc ion per monomer. We then investigated the ability of clade C Tat to block the inhibition of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors from zinc antagonism through ion chelation. Although clade C Tat enhanced N-methyl-d-aspartate-mediated rat hippocampus neuronal toxicity in the presence of zinc, the increase was significantly less than that observed with clade B Tat. These findings suggest that the observed differences in neuropathogenesis found with HIV-1 clade C infection compared to clade B may, in part, be due to a decrease in Tat-mediated neurotoxicity.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) traverses the blood-brain barrier early during infection and productively infects microglial cells and macrophages within the central nervous system (CNS).1 The neurological impairments that follow CNS infection include the loss of executive cortical functions and compromised cognitive and motor functions that may result in AIDS dementia complex (ADC). In the United States, where clade B HIV-1 is prevalent, 60% of HIV-1-infected individuals succumb to cognitive deficits associated with HIV-1, with 10–20% of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)-naive individuals suffering from ADC.2 In India, where clade C accounts for over 95% of all infections,3,4 the prevalence of ADC in HAART-naive individuals is just over 1%5–8 with the prevalence of milder cognitive deficits similar to that observed in the United States. Despite this difference, clade C HIV-1 has been identified in brain autopsies, suggesting a clade-specific difference in HIV-1 neuropathogenesis.1

Histopathologically, ADC is manifested by significant neuronal death in the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, and the basal ganglia combined with the extensive infiltration of monocytes and macrophages into the CNS, astrogliosis, pallor of myelin sheaths, and abnormalities of dendritic processes.9,10 Moreover, the extent of macrophage infiltration into the white matter correlates with the severity of CNS lesions.11 The inflammatory and excitotoxic responses of glial cells to HIV-1 include increased oxidative stress and glutamate levels and the overexpression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. This, combined with the secretion of viral products such as Tat and gp120 from HIV-1-infected cells, creates a milieu that is neurotoxic.12,13

Tat, an 86–101 residue regulatory protein (9-11 kDa) produced early during infection whose primary role is in regulating productive and processive transcription from the HIV-1 long terminal repeat, is secreted by HIV-1-infected cells and is found in the sera of infected individuals.14,15 In studies of clade B Tat, it is unknown whether it is released by infected cells in situ or is transported across the blood-brain barrier,16 but it is detectable within the brains of infected individuals17–20 where it has neurotoxic consequences.13,21–26 Indeed, a single intraventricular injection of clade B Tat leads to pathologies observed in HAD, namely, macrophage infiltration, progressive glial activation, and neuronal cell death.27

The effect of clade B Tat on neuronal apoptosis is thought to be dependent on Tat binding the lipoprotein-related protein receptor and activating the Ca2+-permeable N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (NMDAR).13 Although the precise mechanism by which Tat activates the NMDAR remains unclear, a number of mechanisms have been proposed including indirect activation of the NMDAR. One study showed that clade B Tat exerts a neurotoxic effect on rat hippocampal neurons by binding zinc and thus reversing zinc antagonism of NMDAR, thereby potentiating NMDA-mediated excitotoxic cell death.23 In another study, both clade B and clade C Tat were shown to be similarly secreted from infected cells and that both clades of Tat bind NMDAR with the same efficiency, but induce different levels of excitotoxicity.28 Interestingly, the intact C30C31 motif found in clade B Tat was shown to be critical for exciting the NMDAR, whereas the C31S mutation, found in over 90% of clade C Tat proteins, significantly attenuated this neurotoxic response.24,28 Moreover, clade C Tat has a reduced effect on monocyte chemotaxis and tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-10, chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) production from monocytes29,30 and astrocytes,24,26 possibly as a result of the C31S mutation. In this study, we compared the ability of clade C Tat and the full length form of Tat most commonly used to chelate zinc and whether these interactions affected the neurotoxic potential of the Tat proteins.

Materials and Methods

Tat synthesis

TatHXB2 (B Tat) and Tat93IN905 (C Tat) were synthesized in solid phase using Fast 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry according to the method of Barany and Merrifield31 using 4-hydroxymethylphenoxymethyl-copolystyrene-1% divinylbenzene preloaded resin (0.5 mmol; Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France) on an automated synthesizer (ABI 433A, Applied Biosystems) as previously described.29,32–34 Purification and analysis using high-performance liquid chromatography were carried out as previously described.32 Amino acid analysis was performed on a model 6300 Beckman (Roissy, France) analyzer and mass spectrometry was carried out using an Ettan matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight apparatus (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). Tat was used immediately following dissolution in degassed 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6. Under these conditions, Tat spontaneously oxidizes with the formation of intramolecular disulfide bridges.35 The concentration of Tat was determined on a Beckman DU640 UV-visible spectrometer using an extinction coefficient of 8480 M−1 cm−1.36

Ultraviolet absorption and circular dichroism spectra

The formation of the Tat-zinc complex in the reaction solution was monitored using UV-visible absorption spectra in a Beckman DU640 UV-visible spectrometer. CD spectra were measured with a 100 μm path length from 260 to 178 nm on a JASCO Corp. J-810 spectropolarimeter (Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed as previously described.32

Determination of Tat sulfhydryl concentration

Oxidation of Tat was monitored using the Ellman method.37 Titration of sulfhydryl groups was performed using 5,5′-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) in the presence of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). The concentration of the free −SH groups in solution was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 412 nm with a Beckman DU640 UV-visible spectrometer using ɛ412nm = 14,150 M−1 cm−1 with the molar extinction coefficient defined as A/bc where A is absorbance, b is path length in centimeters, and c is concentration in moles per liter. The ratios of the number of free –SH groups per Tat were calculated using the known concentration of Tat.

Neuronal cell culture and induction of neuronal injury

Rat brain hippocampus neurons from E19 rats were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). Cells (2 × 104) were seeded directly into poly-d-lysine and laminin-treated 96-well cell culture plates and maintained in primary neuron basal medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 37 ng/ml amphotericin, and 2% (w/v) N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein-1 (all Lonza) for 10 days in a humidified incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2. Excitotoxic neuronal cell injury was induced in 10-day-old cultures, a time period during which neurons express NMDA, kainate, and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid, and receptors and are vulnerable to excitotoxic and metabolic insults, was performed essentially as described previously.23 Briefly, hippocampal cultures were initially washed in 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-buffered saline (HBS; 144 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, and 10 mM d-glucose; pH 7.4) then neuronal injury induced by exposing the cells to Mg2+-free HBS supplemented with 300 μM NMDA, 0.5 μM tetrodotoxin, and 1 μM glycine (all Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 10 min alone or in the presence of one or more of ZnCl2, TatHXB2, Tat93IN905, or Tricine (Sigma) at the indicated concentrations. Tetrodotoxin was added to inhibit superoxide production and toxicity resulting from spontaneous neuronal activity under Mg2+-free conditions. Control cultures were exposed to the same solution without the NMDA. After 10 min, cells were washed three times in HBS and cultured in the original culture medium for 24 h. Apoptosis of neuronal cells was assessed using an ELISA-based assay for ssDNA (Apoptosis ELISA Kit, Millipore, Temecula, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A standard curve for apoptotic cell numbers was obtained by exposing 2.5 × 103, 5 × 103, 1 × 104, and 1.5 × 104 neurons to 2 μM staurosporine (Sigma) for 4 h. The relative apoptosis index was calculated using the standard curve to obtain apoptotic cell number and divided by the total cell number obtained prior to fixing the cells.

Immunoblotting

Cells were washed twice in DPBS and then lysed in CelLytic M (Sigma) in the presence of protease inhibitors (Thermo Scientific) and subjected to centrifugation (15,000 × g, 15 min) to remove debris. Samples were then heated to 100°C for 10 min in sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer supplemented with 50 mM dithiothreitol (both Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD) and separated using a 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol buffered 10% polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Thermo Scientific). Membranes were blocked overnight with DPBS supplemented with 0.1% (v/v) polysorbate 20 (Sigma) and 5% (w/v) dried nonfat milk (Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA) and probed with a rabbit monoclonal anticleaved caspase 3 (5A1E) or a mouse monoclonal anti-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (D214) (both Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) followed by detection using the WesternBreeze chemiluminescence kit (Invitrogen). Membranes were subsequently stripped and reprobed with mouse anti-β-actin (Sigma) to confirm equal loading. The relative density of the target bands was compared to the β-actin band and analyzed using ImageJ (NIH).

Statistics

Results are means ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Paired, two-tailed, Student's t tests, α = 0.05, were used to assess whether the means of two normally distributed groups differed significantly.

Results

Clade C Tat93IN905 and clade B TatHXB2 differ in their ability to chelate zinc

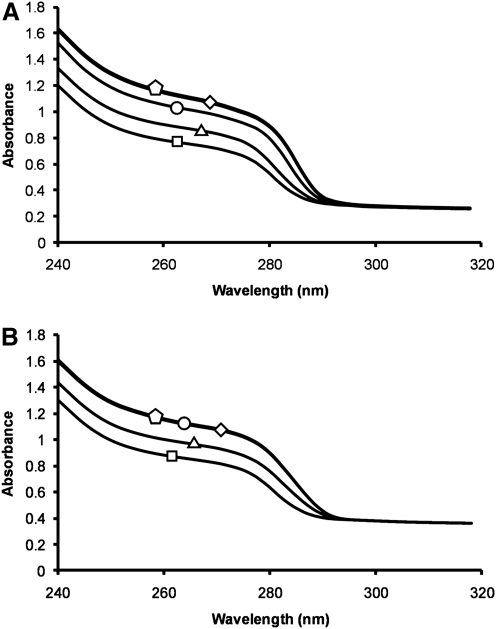

Previous studies have shown that a truncated 86-residue B Tat and a peptide spanning residues 24–51 of clade B Tat bind two zinc ions through five of their seven cysteine residues.38–40 Therefore, to examine whether the full-length B Tat also binds zinc, we performed UV absorption spectra of TatHXB2 with 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 molar equivalents of ZnCl2. The spectra obtained with reduced Tat and 0 to 3.0 molar equivalents of zinc show that the absorbance increases as zinc is added (Fig. 1A). Addition of more than two equivalents of ZnCl2 to clade B Tat had no further change on the spectrum, indicating that two zinc ions bind per B Tat protein in agreement with previous findings38–40 (Fig. 1A). Conversely, the UV absorption spectra of C Tat showed no change on the addition of more than 1.0 molar equivalents of ZnCl2, indicating only one zinc ion binds per C Tat molecule (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Ultraviolet absorption spectra. The ultraviolet absorption spectra of B Tat (A) and C Tat (B) in the absence of zinc (squares) or in the presence of 0.5 (triangles), one (circles), two (diamonds), or three (pentagon) molar equivalencies of zinc.

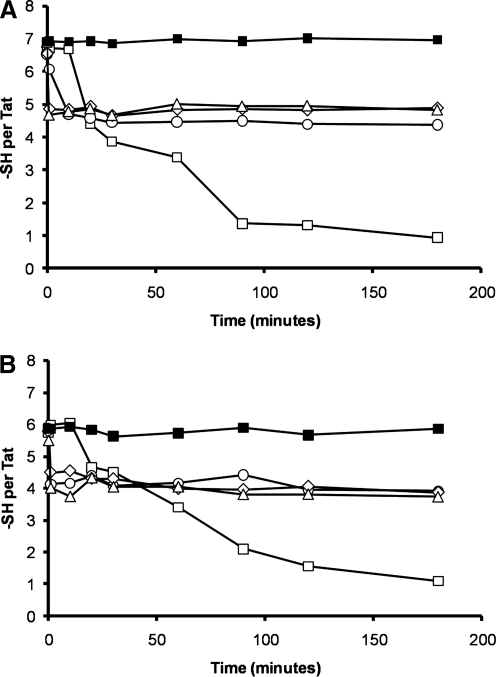

To confirm this finding, we next assessed the effect of zinc binding on the oxidation state of Tat. To do this, we monitored the number of free sulfhydryls per Tat over time. We observed that freshly prepared TatHXB2 contained seven titratable sulfhydryls, while Tat93IN905 possessed six (Fig. 2). This was confirmed by incubation of Tat proteins in degassed 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6, supplemented with 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride, which is selective for the reduction of disulfides. In the absence of zinc and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride, oxidation of the Tat proteins occurred rapidly, and was complete within 3 h, in agreement with previous studies39,40 (Fig. 2). On addition of one equivalent of zinc to TatHXB2, four of the seven sulfhydryls were protected from oxidation, suggesting that only four cysteine residues were involved with the zinc chelation at a 1:1 ratio. Two equivalents of zinc also preserved TatHXB2 from oxidation, but this time five of the seven sulfhydryl groups remained in their reduced form, even after more than 24 h, ruling out the potential metal catalyzed oxidation of TatHXB2 and suggesting that five of the seven cysteine residues of holo-TatHXB2 were involved in binding two zinc cations as previously described39,40 (Fig. 2A; data not shown). There was no difference with three equivalents of zinc, suggesting that TatHXB2 is saturated with two equivalents. Conversely, both one and two equivalents of zinc preserved only four of the six sulfhydryl groups of Tat93IN905, indicating that only four cysteines of Tat93IN905 were involved in binding zinc, suggesting that Tat93IN905 bound only one zinc cation (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Titration of free sulfhydryl groups using the Ellman reaction. The number of free sulfhydryl groups per B Tat (A) and C Tat (B) in 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (black squares), in the absence of zinc (white squares), or in the presence of one (circle), two (diamond), or three (triangle) molar equivalencies of zinc was measured using the Ellman method.37 The decreasing number of free sulfhydryl groups during the incubation period indicates the formation of disulfide bonds during exposure to air.

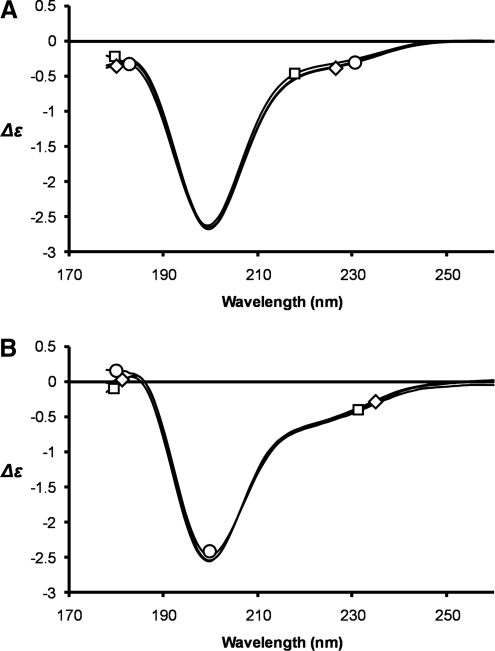

To probe whether zinc ion binding induces a structural change in Tat we used circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy with measurements between 178 and 260 nm, corresponding to the π–π* and n–π* transitions of the amide chromophore located in polypeptide chains. Both Tat proteins show a CD spectrum characterized by negative bands at 200 nm, which could be due to nonorganized structures and/or β-turns (Fig. 3). However, the low intensity of the negative bands at 200 nm suggests that both Tat proteins are not random coil but rather structured with β-turns as the main secondary structures in agreement with the Tat Mal and Tat Eli structures determined by two-dimensional NMR41,42 and a previous study using a carboxymethylated cysteine B Tat that showed that cysteines play a structural role in Tat.43 On the addition of either one or two molar equivalents of ZnCl2 the CD spectra of Tat and the Tat-zinc complexes were essentially indistinguishable for both Tat proteins tested, suggesting that metal binding has no dramatic effect on the folding of Tat (Fig. 3). No changes in the CD spectra of either Tat protein was observed upon the addition of ZnCl2, even though the absorption spectra confirmed that the Tat-metal complexes were properly formed in accordance with previously published data.38,42

FIG. 3.

Circular dichroism. The CD spectra of C31C Tat (A) and C31S Tat (B) were measured from 260 to 178 nm with a 100 μm path length in the absence of zinc (squares) or in the presence of one molar equivalency (circle) or two molar equivalencies (diamond) of zinc. Structural heterogeneities exist between the two Tat proteins but no differences were observed on zinc binding.

Clade C Tat93IN905 is unable to inhibit the neuroprotective effect of zinc in NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity

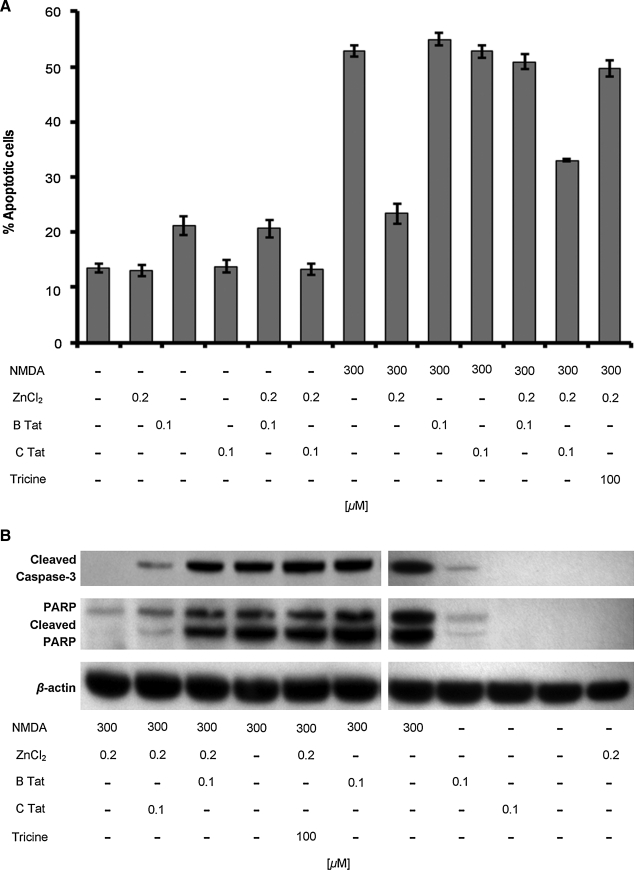

Cultured rat hippocampal neurons are sensitive to NMDA-induced neurotoxicity, the extent of which is significantly reduced by the addition of low concentrations of zinc.22 Although high concentrations of zinc trigger excessive zinc influx, glutathione depletion, and ATP loss leading to necrotic neuronal death, at low concentrations it is neuroprotective during glutamate- and NMDA-induced toxicity through the antagonism of NMDAR activation.23,44,45 Previous studies have shown that B Tat abolishes this neuroprotective effect of zinc during NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity through the chelation of zinc, thereby potentiating the NMDA-mediated apoptosis of cultured rat hippocampal neurons and that chemical modifications of the cysteines found in Tat abrogate this effect.23 Therefore, we investigated the contribution of zinc in C Tat potentiation of NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity. Initially, we confirmed the role of zinc in aiding the survival of primary rat hippocampal cultures after excitotoxic NMDA treatment with apoptosis levels assessed using an antibody specific to ssDNA as the generation of ssDNA is a specific indicator of apoptosis.46 Exposure to 300 μM NMDA for 10 min induced significant levels of neuronal apoptosis after 24 h (mean 13.4 ± 2.3% versus 52.9 ± 3.1%; n = 9; p < 0.0001; Fig. 4). The effect of zinc on NMDA-mediated toxicity was then assessed using 200 nM ZnCl2, the approximate concentration present in human cerebrospinal fluid.47 When 200 nM zinc was added to hippocampal cultures simultaneously with NMDA for 10 min, NMDA-induced neuronal apoptosis was reduced 56% (mean 52.9 ± 3.1% versus 23.4 ± 5.3%; n = 9; p < 0.0001; Fig. 4A), demonstrating that low concentrations of zinc can protect hippocampal neurons from NMDA-mediated glutamate neurotoxicity. We then assessed the ability of B Tat to inhibit the zinc antagonism of NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity by incubating hippocampal neurons in the presence of 200 nM ZnCl2, 300 μM NMDA, and 100 nM B Tat (2:1 ratio Zn2+:B Tat) for 10 min followed by incubation in fresh media for 24 h. We observed a significant decrease in the zinc antagonism of NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity (mean 23.4 ± 5.3% versus 50.9 ± 4.0%; n = 9; p < 0.0001; Fig. 4A). We then repeated the experiments using C Tat in lieu of B Tat and observed that although C Tat inhibited the zinc antagonism of NMDA-mediated apoptosis, the effect was much less than that of B Tat (mean 33.0 ± 0.7% versus 23.4 ± 5.3%; n = 9; p < 0.0001; Fig. 4). To confirm that the neurotoxic effect of Tat was indeed through its ability to chelate zinc, we used the same protocol as before using 100 μM of tricine, a zinc chelator, in lieu of Tat. This resulted in the complete abrogation of the zinc antagonism of NMDA-mediated apoptosis (mean 52.9 ± 3.1% versus 49.7 ± 4.4%; n = 9; p = 0.09; Fig. 4A). Interestingly, in the absence of zinc and NMDA, B Tat was still mildly neurotoxic (mean 13.4 ± 2.3% versus 21.1 ± 4.9%; n = 9; p = 0.0009), whereas C Tat had no effect (p = 0.6).

FIG. 4.

Tat-induced apoptosis of hippocampal neurons. (A) Quantification of neuronal apoptosis measured using the ssDNA ELISA after exposure to NMDA, ZnCl2, Tat, and/or tricine. Results are means ± SEM of three donors performed in triplicate. (B) Immunoblots of neuronal cells exposed to NMDA, ZnCl2, Tat, and/or tricine and probed with antibodies to cleaved caspase 3, PARP, and β-actin.

Caspases contribute to the overall apoptotic morphology by cleavage of various cellular substrates. Therefore, to confirm the morphological and ssDNA ELISA observations, we prepared whole cell lysates of cells treated with NMDA with or without zinc, B Tat, C Tat, or tricine for 10 min and examined caspase-3 activation and proteolytic cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 (PARP), a nuclear enzyme involved in DNA repair, DNA stability, and transcriptional regulation by Western blotting after a further 8 h incubation. Figure 4B shows that NMDA treatment induces activation of caspase 3 and the degradation of PARP, which is significantly decreased in the presence of 200 nM ZnCl2. Both B Tat and C Tat significantly decreased the zinc antagonism of NMDA-mediated caspase 3 activation and PARP cleavage (Fig. 4B), although C Tat to a much lesser extent. Tricine completely abrogated the zinc inhibition of NMDA-mediated caspase 3 activation and PARP degradation (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

Epidemiological studies suggest that the reduced prevalence of ADC in countries such as India, where clade C is most prevalent,5–8 implies clade-specific differences in neuropathogenesis. Indeed, a recent in vivo study using the severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) mouse HIV encephalitis model showed that mice exposed to clade B HIV-1 exhibited greater memory errors, astrogliosis, and increased loss of neuronal network integrity than mice exposed to clade C HIV-1.25 Moreover, as one of the hallmarks of ADC is the infiltration of monocytes and macrophages into the CNS, that is both Tat and CCL2 dependent,25 it is interesting to note that clade C HIV-1 Tat is a poor monocyte chemoattractant25,29,48 and elicits reduced CCL2 and TNF from uninfected monocytes.29 Previous studies have shown that clade B Tat is excitotoxic to hippocampal neurons by potentiating NMDA-induced currents of the zinc-sensitive NR1/NR2A NMDAR in a zinc-binding-dependent mechanism.23 Therefore, we compared the ability of both clades to bind zinc and to cause neurotoxicity. We found that clade B Tat bound two zinc ions through five of its seven cysteines, in agreement with previous studies,39,40 that most likely did not involve a change in global structure. We also found that clade C Tat bound just one zinc ion through four of its six cysteines that similarly did not involve a change in global structure.

The role of zinc in the structure and function of Tat is still unclear. However, given the reducing nature of the cytoplasmic environment, combined with the inherent high concentrations of zinc and copper therein, it is possible that Tat binds zinc in vivo. Indeed, Tat-zinc binding was shown to be indispensible for the interaction of clade B Tat with T1 cyclin, essential for the Tat-mediated trans-activation of HIV-1 proviral DNA transcription.49 Using a model where Tat is added as an exogenous protein that must traverse the cell membrane before it can bind the trans-activation responsive element and trans-activate HIV-1 long terminal repeat gene expression, no difference in the trans-activational ability between clade B and clade C Tat proteins is observed, regardless of the presence or absence of the C31S mutation.29,50 However, a study using endogenously produced Tat showed that clade C Tat displayed higher affinities for both the trans-activation responsive element and for the positive transcription elongation factor b complex than clade B Tat51 and exerts a greater trans-activation potential.51 Moreover, a recent study showed that the serine residues in Tat are phosphorylated by a cyclin-dependent kinase-2 mechanism and that this phosphorylation is important for HIV-1 transcription and the activation of integrated HIV-1 provirus.52 Therefore, it is possible that the C31S mutation found in clade C Tat gives it a potential new phosphorylation site, compensating for the loss of a cysteine and augmenting its trans-activational activity. It is also entirely plausible that the C31S mutation may have other functions that have not yet been identified.

In this study we observed that clade C Tat is considerably less neurotoxic than clade B Tat. It is possible that this difference is due, in part, to the finding that B Tat has two zinc-binding sites that bind zinc releasing the NMDAR from zinc-mediated inhibition of NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity whereas the ability of clade C Tat to perform this role is severely limited by the fact that it chelates only one zinc ion per molecule of Tat. However, a previous study demonstrated that clade B Tat induces the persistent activation of NMDAR in the presence of tricine even after the destruction of the zinc-binding site in the NR1 subunit of the NMDAR.23 Therefore, the neurotoxic effects of clade B Tat may also be mediated by the direct interaction of Tat with the NMDAR in the absence of zinc. One hypothesis is that the Cys-31 of B Tat forms a disulfide bond with Cys-744 of the NMDAR resulting in a free sulfhydryl group at the NMDAR Cys-798 causing the persistent and abnormal neurotoxic activation of the receptor.28 Interestingly, both clade B and clade C Tat proteins have been shown to bind NMDAR through their arginine-rich region with the same efficiency,28 indicating that unlike binding to CCR2,29 the Cys-31 may not be required for mediating Tat binding to the NMDAR.28 In this study we also observed that in the absence of NMDA and zinc, B Tat, but not C Tat, still induced the apoptosis of hippocampal neurons, albeit at much lower levels than that induced by NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity. This is consistent with other studies that found that clade C Tat has severely attenuated neurotoxicity.24,25,28

Despite extensive in vitro research and in vivo animal studies demonstrating a potential role of Tat in HIV-related CNS impairment, no study to date has directly quantified the in vivo levels of secreted Tat in the CNS, and as such the biologically relevant levels of Tat in the brain that may be associated with ADC are unknown. However, Tat has been detected in postmortem HIV-encephalitic CNS tissue in various infected cells11,17–20 as well as in uninfected oligodendrocytes20 supporting in vitro findings that secreted Tat from infected cells can be localized in neighboring uninfected cells.21 Moreover, in a mouse model of brain toxicity after a single intraventricular injection of Tat, pathological changes were observed over several days while within 6 h Tat was undetectable,27 highlighting the problem of detecting extracellular Tat in vivo. Thus, the biologically relevant levels of Tat in the brain that might be associated with ADC are unknown. It is also difficult to extrapolate our in vitro observations to what may happen within the HIV-infected human CNS where soluble factors such as interferon-γ, gp120, and HAART modulate the activity of monocytes and microglia. Also, although clade C Tat is unable to induce significant levels of TNF,29 individuals infected with clade C HIV may still have elevated levels as many host or viral factors likely contribute to TNF production.

As Tat promotes HIV-1 replication and is involved in a number of pathophysiological effects, therapeutic approaches targeting Tat could be effective in reducing the serious consequences of HIV-1 infection. Additionally, these studies further support important differences among HIV-1 clades, and suggest that subtle changes in the virus can lead to important differences in HIV-1 pathogenesis and clinical disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant U01 AI068632 to the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Mahadevan A. Shankar SK. Satishchandra P, et al. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected cells in infiltrates associated with CNS opportunistic infections in patients with HIV clade C infection. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:799–808. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181461d3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant I. Sacktor N. McArthur J. HIV neurocognitive disorders. In: Gendelman HE, editor; Grant I, editor; Everall I, editor; Lipton SA, editor; Swindells S, editor. The Neurology of AIDS. 2nd. Oxford University Press; London, UK: 2005. pp. 357–373. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddappa NB. Dash PK. Mahadevan A, et al. Identification of subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by subtype-specific PCR and its use in the characterization of viruses circulating in the southern parts of India. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2742–2751. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2742-2751.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemelaar J. Gouws E. Ghys PD. Osmanov S. Global and regional distribution of HIV-1 genetic subtypes and recombinants in 2004. AIDS. 2006;20:W13–23. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247564.73009.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satishchandra P. Nalini A. Gourie-Devi M, et al. Profile of neurologic disorders associated with HIV/AIDS from Bangalore, south India (1989–96) Indian J Med Res. 2000;111:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankar SK. Mahadevan A. Satishchandra P, et al. Neuropathology of HIV/AIDS with an overview of the Indian scene. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121:468–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riedel D. Ghate M. Nene M, et al. Screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) dementia in an HIV clade C-infected population in India. J Neurovirol. 2006;12:34–38. doi: 10.1080/13550280500516500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta JD. Satishchandra P. Gopukumar K, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clade C-seropositive adults from South India. J Neurovirol. 2007;13:195–202. doi: 10.1080/13550280701258407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adle-Biassette H. Chretien F. Wingertsmann L, et al. Neuronal apoptosis does not correlate with dementia in HIV infection but is related to microglial activation and axonal damage. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1999;25:123–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1999.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray F. Adle-Biassette H. Chretien F. Lorin de la Grandmaison G. Force G. Keohane C. Neuropathology and neurodegeneration in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pathogenesis of HIV-induced lesions of the brain, correlations with HIV-associated disorders and modifications according to treatments. Clin Neuropathol. 2001;20:146–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zink MC. Suryanarayana K. Mankowski JL, et al. High viral load in the cerebrospinal fluid and brain correlates with severity of simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J Virol. 1999;73:10480–10488. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10480-10488.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Scarano F. Martin-Garcia J. The neuropathogenesis of AIDS. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:69–81. doi: 10.1038/nri1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King JE. Eugenin EA. Buckner CM. Berman JW. HIV tat and neurotoxicity. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1347–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westendorp MO. Frank R. Ochsenbauer C, et al. Sensitization of T cells to CD95-mediated apoptosis by HIV-1 Tat and gp120. Nature. 1995;375:497–500. doi: 10.1038/375497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao H. Neuveut C. Tiffany HL, et al. Selective CXCR4 antagonism by Tat: Implications for in vivo expansion of coreceptor use by HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11466–11471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks WA. Robinson SM. Nath A. Permeability of the blood-brain barrier to HIV-1 Tat. Exp Neurol. 2005;193:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofman FM. Dohadwala MM. Wright AD. Hinton DR. Walker SM. Exogenous tat protein activates central nervous system-derived endothelial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;54:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nath A. Geiger JD. Mattson MP. Magnuson DSK. Jones M. Berger JR. Role of viral proteins in HIV-1 neuropathogenesis with emphasis on Tat. NeuroAIDS. 1998;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudson L. Liu J. Nath A, et al. Detection of the human immunodeficiency virus regulatory protein tat in CNS tissues. J Neurovirol. 2000;6:145–155. doi: 10.3109/13550280009013158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Del Valle L. Croul S. Morgello S. Amini S. Rappaport J. Khalili K. Detection of HIV-1 Tat and JCV capsid protein, VP1, in AIDS brain with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurovirol. 2000;6:221–228. doi: 10.3109/13550280009015824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tardieu M. Hery C. Peudenier S. Boespflug O. Montagnier L. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected monocytic cells can destroy human neural cells after cell-to-cell adhesion. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:11–17. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song L. Nath A. Geiger JD. Moore A. Hochman S. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein directly activates neuronal N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors at an allosteric zinc-sensitive site. J Neurovirol. 2003;9:399–403. doi: 10.1080/13550280390201704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandra T. Maier W. Konig HG, et al. Molecular interactions of the type 1 human immunodeficiency virus transregulatory protein Tat with N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunits. Neuroscience. 2005;134:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra M. Vetrivel S. Siddappa NB. Ranga U. Seth P. Clade-specific differences in neurotoxicity of human immunodeficiency virus-1 B and C Tat of human neurons: Significance of dicysteine C30C31 motif. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:366–376. doi: 10.1002/ana.21292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao VR. Sas AR. Eugenin EA, et al. HIV-1 clade-specific differences in the induction of neuropathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10010–10016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2955-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samikkannu T. Saiyed ZM. Rao KV, et al. Differential regulation of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) by HIV type 1 clade B and C Tat protein. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:329–335. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones M. Olafson K. Del Bigio MR. Peeling J. Nath A. Intraventricular injection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) tat protein causes inflammation, gliosis, apoptosis, and ventricular enlargement. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:563–570. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199806000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li W. Huang Y. Reid R, et al. NMDA receptor activation by HIV-Tat protein is clade dependent. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12190–12198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3019-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell GR. Watkins JD. Singh KK. Loret EP. Spector SA. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C Tat fails to induce intracellular calcium flux and induces reduced tumor necrosis factor production from monocytes. J Virol. 2007;81:5919–5928. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01938-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong JK. Campbell GR. Spector SA. Differential induction of interleukin-10 in monocytes by HIV-1 Clade B and Clade C Tat proteins. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18319–18325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.120840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barany G. Merrifield RB. Solid phase peptide synthesis. In: Gross E, editor; Meinhofer J, editor. The Peptide: Analysis, Synthesis, Biology. Vol. 2. Academic Press; New York: 1980. pp. 1–284. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell GR. Pasquier E. Watkins J, et al. The glutamine-rich region of the HIV-1 Tat protein is involved in T-cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48197–48204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell GR. Watkins JD. Esquieu D. Pasquier E. Loret EP. Spector SA. The C terminus of HIV-1 Tat modulates the extent of CD178-mediated apoptosis of T cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38376–38382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell GR. Senkaali D. Watkins J, et al. Tat mutations in an African cohort that do not prevent transactivation but change its immunogenic properties. Vaccine. 2007;25:8441–8447. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koken SE. Greijer AE. Verhoef K. van Wamel J. Bukrinskaya AG. Berkhout B. Intracellular analysis of in vitro modified HIV Tat protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8366–8375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gasteiger E. Hoogland C. Gattiker A, et al. Protein identification, analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In: Walker JM, editor. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frankel AD. Bredt DS. Pabo CO. Tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus forms a metal-linked dimer. Science. 1988;240:70–73. doi: 10.1126/science.2832944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang HW. Wang KT. Structural characterization of the metal binding site in the cysteine-rich region of HIV-1 Tat protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:615–621. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egelé C. Barbier P. Didier P, et al. Modulation of microtubule assembly by the HIV-1 Tat protein is strongly dependent on zinc binding to Tat. Retrovirology. 2008;5:62. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grégoire C. Péloponèse JM., Jr. Esquieu D, et al. Homonuclear (1)H-NMR assignment and structural characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat Mal protein. Biopolymers. 2001;62:324–335. doi: 10.1002/bip.10000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watkins JD. Campbell GR. Halimi H. Loret EP. Homonuclear 1H NMR and circular dichroism study of the HIV-1 Tat Eli variant. Retrovirology. 2008;5:83. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Péloponèse JM., Jr. Collette Y. Grégoire C, et al. Full peptide synthesis, purification, and characterization of six Tat variants. Differences observed between HIV-1 isolates from Africa and other continents. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11473–11478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paoletti P. Ascher P. Neyton J. High-affinity zinc inhibition of NMDA NR1-NR2A receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5711–5725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05711.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen CJ. Liao SL. Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of zinc on neonatal cortical neurons. Neurochem Int. 2003;42:471–479. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frankfurt OS. Krishan A. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the specific detection of apoptotic cells and its application to rapid drug screening. J Immunol Methods. 2001;253:133–144. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palm R. Sjostrom R. Hallmans G. Optimized atomic absorption spectrophotometry of zinc in cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Chem. 1983;29:486–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ranga U. Shankarappa R. Siddappa NB, et al. Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C strains is a defective chemokine. J Virol. 2004;78:2586–2590. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2586-2590.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garber ME. Wei P. KewalRamani VN, et al. The interaction between HIV-1 Tat and human cyclin T1 requires zinc and a critical cysteine residue that is not conserved in the murine CycT1 protein. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3512–3527. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Opi S. Péloponèse JM., Jr Esquieu D, et al. Full-length HIV-1 Tat protein necessary for a vaccine. Vaccine. 2004;22:3105–3111. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Desfosses Y. Solis M. Sun Q, et al. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gene expression by clade-specific Tat proteins. J Virol. 2005;79:9180–9191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9180-9191.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ammosova T. Berro R. Jerebtsova M, et al. Phosphorylation of HIV-1 Tat by CDK2 in HIV-1 transcription. Retrovirology. 2006;3:78. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]