Summary

Emerging evidence suggests that protein acetylation is a broad-ranging regulatory mechanism. Here we utilize acetyl-peptide arrays and metabolomic analyses to identify substrates of mitochondrial deacetylase Sirt3. We identified ornithine transcarbamoylase (OTC) from the urea cycle, and enzymes involved in β-oxidation. Metabolomic analyses of fasted mice lacking Sirt3 (sirt3−/−) revealed alterations in β-oxidation and the urea cycle. Biochemical analysis demonstrated that Sirt3 directly deacetylates OTC and stimulates its activity. Mice under caloric restriction (CR) increased Sirt3 protein levels, leading to deacetylation and stimulation of OTC activity. In contrast, sirt3−/− mice failed to deacetylate OTC in response to CR. Inability to stimulate OTC under CR led to a failure to reduce orotic acid levels, a known outcome of OTC deficiency. Thus, Sirt3 directly regulates OTC activity and promotes the urea cycle during CR, and the results suggest that under low energy input, Sirt3 modulates mitochondria by promoting amino-acid catabolism and β-oxidation.

Introduction

Mitochondria are central to cellular metabolism, and dysregulation has been implicated in numerous diseases and cellular aging (Tanaka et al. 2007). Understanding the regulation of mitochondrial enzymes and their associated pathways is essential to grasp how mitochondria function and adapt numerous metabolic processes and maintain cellular viability under the demands of diverse dietary input. Analysis of novel regulatory mechanisms, especially protein acetylation, promises to provide new knowledge on mitochondrial regulation and provide essential molecular insight into mitochondrial-based disease.

Extensive lysine acetylation of mitochondrial proteins has been reported in a number of proteomic studies (Choudhary et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2010), in which mass spectrometry was utilized to identify isolated peptides containing an acetyl-lysine moiety. The growing list of acetylated proteins includes those involved in TCA cycle, fatty acid oxidation, NADH oxidation, and oxidative phosphorylation (Choudhary et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2010). These recent observations suggest that protein acetylation might be a major regulatory mechanism to regulate cellular function and might rival other well-studied modifications, such as phosphorylation. However, little is known about the functional role of these modifications, and only a handful of examples have explored their molecular mechanisms (Hallows et al., 2006; Schwer et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2010). In several instances, proteins are acetylated at numerous sites (Hirschey et al. 2010; Yu et al.,2009), making functional studies inherently difficult. Determination of functionally relevant lysine acetylation and the molecular mechanisms that explain how acetylation controls protein activity are paramount to uncovering the role of reversible acetylation in fundamental cellular processes.

Although the full complement of enzymes responsible for protein acetylation and deacetylation have not been comprehensively identified, the NAD+ dependent deacetylases (sirtuins) have emerged as a major class of enzymes that deacetylate a growing list of non-histone proteins (Smith et al. 2010). Sirtuins have been implicated in many cellular processes, including genomic maintenance, transcription and metabolism (Donmez and Guarente, 2010; Haigis and Sinclair, 2010). Genetic evidence has linked sirtuins with lifespan in several model organisms (Lin et al., 2000; Tissenbaum and Guarente, 2001) The seven sirtuins in mammals (Sirt1-7) display distinct sub-cellular distribution, with Sirt3, Sirt4, and Sirt5 localized to the mitochondria (Huang et al., 2010).

Given the weak deacetylase activity of Sirt4 and Sirt5, Sirt3 has been suggested to function as the major protein deacetylase within the mitochondrial matrix (Lombard et al., 2007). In a few cases, there is compelling evidence that Sirt3 directly regulates the acetylation state and activity of target proteins. These include AceCS2, MRPL10, Complex I, LCAD and IDH2 (Ahn et al., 2008; Hallows et al., 2006; Hirschey et al., 2010; Schwer et al., 2009; Someya et al., 2010; Yang et al.,2010). During fasting and caloric restriction, Sirt3 mRNA and protein levels are increased, leading to significant changes in the acetylation profile in mitochondria (Barger et al., 2008; Schwer et al., 2009; Someya et al., 2010). Taken together, Sirt3 represents an intriguing candidate as a central regulator of mitochondrial metabolism (Bao et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2009), yet the full extent of Sirt3-dependent metabolic control remains to be established.

Here we utilize complementary high-throughput approaches that feature acetyl-peptide arrays and metabolomic analyses to identify substrates of the mitochondrial NAD+-dependent deacetylase Sirt3. The combined analysis revealed that the urea cycle enzyme ornithine transcarbamoylase (OTC), and several enzymes involved in fatty-acid oxidation were potential cellular targets of Sirt3. Additional biochemical studies demonstrated that OTC is a bona fide substrate of Sirt3, and investigations in cultured cells and in mice lacking the Sirt3 gene (sirt3−/−) establish that Sirt3 modulates the urea cycle through deacetylation and stimulation of OTC in response to caloric restriction. Taken together, we propose a model in which Sirt3 modulates the ability of mitochondria to adapt to low energy input (during fasting and caloric restriction), including promotion of amino-acid catabolism, β-oxidation, and acetate recycling.

Results

High throughput analysis of Sirt3-regulated pathways

To identify novel Sirt3 substrates in an unbiased manner, we carried out complementary, high throughput approaches that featured acetyl-peptide arrays and metabolomic analyses. We reasoned that use of the peptide arrays would allow us to narrow down potential deacetylation targets of Sirt3, and the metabolomic analysis of mice deficient in Sirt3 (sirt3−/−) would provide functional evidence for a connection between the two approaches. We recently developed a novel SPOT peptide library screening strategy to accelerate the identification of sirtuin substrates, of which the detailed development and validation is described elsewhere (Smith et al., 2010). Here, we utilized this methodology to identify potential Sirt3 substrate targets. Briefly, a SPOT array of ~240 peptides containing known acetyl-lysine sites from mammalian mitochondria was synthesized (Kim et al., 2006). The SPOT technique involves synthesis of peptides covalently attached to amine-modified cellulose membranes via their C-termini. The binding preferences of human recombinant Sirt3 were assessed by screening SPOT membranes, where each 9-mer peptide harbored a tight-binding acetyl-lysine analog (thiotrifluoroacetyl-lysine) with 4 variable amino acids on either side. Sirt3 was applied to the SPOT cellulose membrane, and analogous to a western blot, the membrane was probed with anti-Sirt3 antibody, followed by secondary-HRP-conjugated antibody. The blot was then imaged and quantified for emitted light, revealing differential intensities among the peptide spots (intensities ranged from 0 to 47000 integrated optical density, IOD, Figure 1A).

Figure 1. High throughput analysis to identify Sirt3 substrates.

A.) Screening the mitochondrial acetylproteome by SPOT peptide array. The SPOT peptide library (Smith et al, 2010) was probed with 2 μM Sirt3. The amount of Sirt3 bound was quantified with an α-Sirt3 polyclonal antibody and goat α-rabbit HRP conjugated secondary and developed with ECL reagent. A ranked list of the mitochondrial sequences is provided in Supplemental Table 1. B) 2-D NMR analysis of extracted liver metabolites. White bars represent metabolite levels of wild type (normalized to 1 with associated measurement errors) and black bars represent the relative level in sirt3−/− mice. Error bars represent standard error measurement (SEM) (n=5). C.) Mass spectrometry analysis of extracted liver metabolites. White bars represent metabolite levels of wild type (normalized to 1 with associated measurement errors) and black bars represent the relative level in sirt3−/− mice. Error bars represent standard error measurement (SEM) (n=5). D.) Metabolite measurement of acylcarnitines from 48 hr fasted mouse blood by mass spectrometry analysis. White bars represent metabolite levels of wild type (normalized to 1 with associated measurement errors) and black bars represent the relative level in sirt3−/− mice. Error bars represent standard error measurement (SEM) (n=5). E.) Metabolite measurement of amino acids from 48 hr fasted mouse blood by mass spectrometry analysis. White bars represent metabolite levels of wild type (normalized to 1 with associated measurement errors) and black bars represent the relative level in sirt3−/− mice. Error bars represent standard error measurement (SEM) (n = 5), * signifies a p < 0.05.

Quantification of the SPOT peptide library revealed that Sirt3 bound most tightly to acetylated peptides corresponding to a number of central metabolic enzymes (Supplemental Table 1). Several enzymes involved in β-oxidation ranked near the top of the peptide array; these peptides correspond to: short chain L-3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (SCHAD) in the top 2%, short/branched chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (ACADSB) in the top 4%, very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) in the top 21% and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (βKT) in the top 5% (spot H3, H7, G7 and F13, respectively; Figure 1A).

Among the tightest binding peptides (top 4%) was a peptide corresponding to K88 of ornithine transcarbamolyase (OTC) (spot 5F; Figure 1A). OTC catalyzes the second step in the urea cycle, an important metabolic pathway that detoxifies ammonia generated during amino acid catabolism. This site on OTC is of particular importance, as Yu et al demonstrated that the acetylation state of K88 was dynamically controlled by different nutrient conditions in cultured cells (Yu et al., 2009). Mutational analysis of K88 suggested that acetylation would decrease the enzymatic activity of OTC by decreasing kcat and decreasing the affinity for carbamoyl phosphate, but not for ornithine (Yu et al., 2009).

Metabolite analysis of sirt3−/− animals

To investigate the biochemical phenotypes of mice lacking Sirt3 (sirt3−/−), with particular emphasis on β-oxidation and the urea cycle, the concentrations of key metabolites in both overnight fasted wild type and sirt3−/− B6 mice (Figure S2) were determined by 2D-NMR analysis of liver metabolites and mass spectral analysis of liver tissue and whole blood. These approaches allowed for the determination of relative concentrations of numerous metabolites, and provided an unbiased metabolomic profile of liver and whole blood. Through statistical comparisons of metabolite levels between wild type and sirt3−/− mice, a number of significant changes were identified.

As assessed by 2D NMR analysis, the relative ratios of liver metabolites revealed that sirt3−/− mice exhibited a clear perturbation in several urea cycle intermediates (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the levels of aspartate (an amino acid necessary for urea cycle flux) and ornithine (a urea cycle intermediate and substrate of OTC) were increased in livers of animals from the sirt3−/− population compared to wild type animals (Figure 1B). Both metabolites are central to the urea cycle, and are consistent with a deficiency in the OTC-catalyzed step. The increase in aspartate is indicative of decreased flux through the urea cycle (Gordon, 2003). Also, sirt3−/− animals displayed a significant decrease in uracil and an increase in uridine compared to wild type mice. Uracil and uridine are central pyrimidine metabolites and changes in these molecules can reflect flux perturbations in the urea cycle and the formation of alternative nitrogen carrying metabolites (Wendler et al., 1983). These changes may reflect metabolic dysfunction in the urea cycle, but it is formally possible that other targets of Sirt3 affect these metabolites directly.

Analysis of liver metabolites by mass spectrometry (MS) allowed detection of lower abundance metabolites, a caveat of NMR metabolite analysis. In these MS analyses, many amino acids and acylcarnitines in the liver were detected and compared between wild type animals and the sirt3−/− population. Although the levels of many amino acids were unchanged, the sirt3−/− mice displayed a significant decrease in the levels of glutamine, tryptophan and argininosuccinate (Figure 1C). It is important to note that argininosuccinate is the product of argininosuccinate synthase, which is part of the urea cycle. Interestingly, there was also a large increase in palmitoylcarnitine, a central fatty acid of β-oxidation.

Next, using LC-MS and isotopic standards, we analyzed a panel of blood acylcarnitines and amino acids from 48 hour fasted wild type and sirt3−/− mice. Blood analysis allowed for the determination of whole body metabolite changes. Acylcarnitines are indicators of fatty acid catabolism and abnormal levels are indicators of β-oxidation dysfunction. Statistical comparisons revealed that a substantial number of acylcarnitines are elevated in the sirt3−/− mice (Figure 1D), specifically malonylcarnitine (C3DC), 3-hydroxybutyrylcarnitine (C4OH), tetradecanoylcarnitine (C14), tetradecenoylcarnitine (C14:1), palmitoylcarnitine (C16), and palmitoleylcarnitine (C16:1). These acylcarnitines are increased over wild type with a p-value ≤ 0.05. The observation that numerous acylcarnitines are increased in fasted sirt3−/− mice indicates a potentially widespread dysfunction in β-oxidation. We propose that Sirt3 modulates fatty acid oxidation at multiple points, which is supported by our SPOT peptide array which ranks short chain L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCHAD), very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase as highly probable substrates for Sirt3 deacetylation (spot H3, G7 and F13, respectively Figure 1A). Consistent with these observations, Hirschey et al. recently reported LCAD (long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase) as a target of Sirt3 (Hirschey et al., 2010).

In addition to detecting perturbations in whole blood acylcarntinine levels, there was a significant reduction of citrulline in the sirt3−/− mice (Figure 1E). Citrulline is the direct product of OTC and a reduction is consistent with OTC inhibition in sirt3−/− mice. Together, the urea cycle metabolite differences between wild type and sirt3−/− were indicative of an ineffective response of the urea cycle at the OTC step (Figure 1B, C & E).

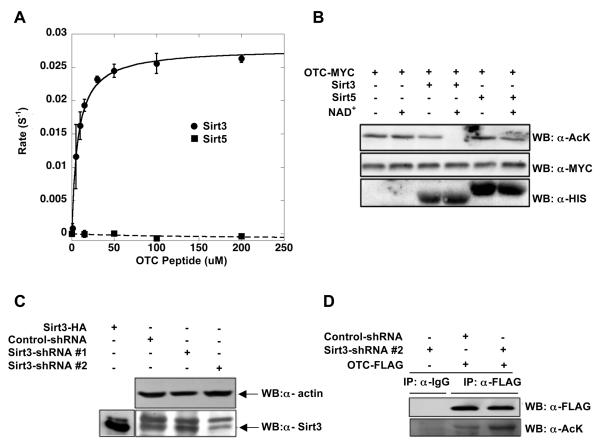

In vitro deacetylation of OTC by Sirt3

Our high throughput peptide arrays and metabolome analysis suggested a number of central metabolic enzymes as possible in vivo targets of Sirt3. Given the prior work that K88 of OTC is likely a functionally relevant acetylation site (Yu et al., 2009), and our evidence that urea cycle metabolites display altered levels in the sirt3−/− mice, we decided to investigate further the link between Sirt3 and OTC, providing both direct biochemical evidence and physiological consequences of OTC dysregulation. To demonstrate that the acetylated OTC-K88 peptide was an efficient Sirt3 substrate, steady-state rates were measured with varying acetylated OTC-K88 peptide concentrations and fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Figure 2A). Consistent with the SPOT peptide library analysis, Sirt3 exhibited a low Km value of 7.2 μM for the acetylated OTC-K88 peptide. This value compares favorably to an AceCS2 peptide (Km = 15.4 μM) (Smith et al., 2010), a known Sirt3 substrate (Hallows et al., 2006; Schwer et al., 2006). For comparison, Sirt5 failed to yield measurable deacetylation rates with acetylated OTC-K88 peptide at concentrations as high as 200 μM (Figure 2A). Together, the SPOT peptide library screens, steady-state kinetic analysis, and metabolite determination suggested OTC was a bona fide Sirt3 substrate in human mitochondria. These results coupled to the prior observation that K88 acetylation is dynamically regulated in response to nutrients prompted us to further explore the possibility that Sirt3 regulates OTC by direct deacetylation of K88.

Figure 2. In vitro and in vivo deacetylation of OTC by Sirt3.

A.) Steady-state kinetic analysis of Sirt3-dependent deacetylation of acetylated OTC-K88 peptide. Sirt3 (filled circles) demonstrates substrate saturation kinetics. No significant activity was observed with Sirt5 (filled boxes) (n=3). B.) Sirt3, but not Sirt5, deacetylates OTC in vitro. Acetylated OTC was prepared as outlined in Experimental Procedure, and was incubated with purified recombinant Sirt3 37 °C or Sirt5 with or without NAD+ at 37 °C for 1 hour. Acetylation status was assessed by western blotting with anti-acetyl-lysine antibody. An anti-MYC western shows equivalent OTC protein levels were used and anti-HIS shows purified Sirt3 and Sirt5. C.) shRNA knockdown of Sirt3 and increase in OTC acetylation levels. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with control or shRNA 1# or 2# for knockdown Sirt3, cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting with anti-actin or anti-Sirt3 antibodies. D.) OTC was Overexpressed in HEK293 cells of Sirt3 shRNA 2# and cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting with FLAG antibody or anti-acetyl-lysine antibody.

Next, we determined whether native acetylated OTC protein was an efficient Sirt3 substrate. Deacetylation was assayed using OTC obtained from nicotinamide-treated HEK293 cells (Figure 2B). Only when immuno-purified OTC was incubated with both Sirt3 and NAD+ was complete loss of OTC acetylation detected by anti acetyl-lysine western blot. Similar to the results from the peptide deacetylation assay (Figure 2A), Sirt5 with or without NAD+ displayed no significant deacetylation activity on acetylated OTC (Figure 2B). Furthermore, knockdown of endogenous Sirt3 protein with Sirt3 specific shRNA led to an increase in the acetylation state, revealed from immunoprecipitated OTC (Figure 2C-D). These findings indicate that OTC is efficiently deacetylated by Sirt3, but not Sirt5. Sirt4 was not examined in this assay because this mitochondrial sirtuin displays no deacetylase activity (North et al., 2005), and is reported to be a protein ADP-ribosyltransferase (Haigis et al., 2006).

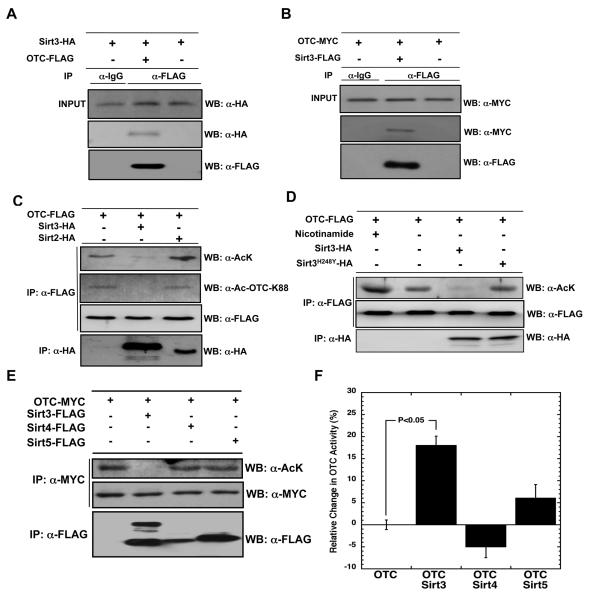

Although it is generally observed that most enzyme:substrate reactions are necessarily transient interactions to promote rapid turnover, sometimes co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments can be useful to trap these complexes, providing evidence for interaction within cellular context. Co-IP experiments were performed in human kidney cells (HEK293) co-transfected with Sirt3 and OTC. Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated OTC-FLAG reveals the presence of Sirt3-HA (Figure 3A). In the reciprocal experiment, immunoprecipitated Sirt3-FLAG reveals the presence of OTC-MYC (Figure 3B). Attempts to Co-IP endogenous proteins were unsuccessful, likely due to technical limitations of low protein levels. Nevertheless, the expression studies demonstrate that OTC and Sirt3 are capable of forming a relatively stable complex in extracts from culture cells.

Figure 3. Sirt3 specifically interacts with and deacetylates OTC in culture cells.

A.) Immunoprecipitation of OTC detects Sirt3 when both OTC and Sirt3 are coexpressed in HEK293 cells. B) Immunoprecipitation of Sirt3 detects OTC when both OTC and Sirt3 are coexpressed in HEK293 cells. C.) Sirt3 deacetylates K88 of OTC when coexpressed in HEK293 cells. D.) Sirt3 catalytic activity is necessary for deacetylation of OTC. OTC was cotransfected with Sirt3 or H248Y mutant of Sirt3 in HEK293, isolated by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody followed by western blotting with anti-acetyl-lysine antibody. E-F.) OTC activity is stimulated by Sirt3-dependent deacetylation. Proteins from lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG and anti-MYC antibodies and were analyzed by western blotting with anti-FLAG, anti-MYC or anti-acetyl-lysine antibodies (E). A significant stimulation of OTC activity was observed with Sirt3, but not with Sirt4 and Sirt5 (F). Error bars represent standard error measurement (SEM) (n = 3), * signifies a p < 0.05.

The observations that OTC and Sirt3 interact (Figure 1A & Figure 3A-B), that native acetylated OTC and an OTC-K88 peptide are efficiently deacetylated in vitro (Figure 2A-B), and that urea cycle metabolites are altered in sirt3−/− mice (Figure 1B-C and E) provided compelling evidence that Sirt3 might directly deacetylate and regulate OTC in vivo. To determine if Sirt3 is critical for OTC deacetylation in mitochondria, OTC and Sirt3 were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells, and the corresponding cellular extracts were probed for the presence of acetyl-lysine and acetylated-K88 of OTC (Figure 3C). As a control, a similar experiment was performed with Sirt2 to show that a highly active sirtuin that is broadly expressed throughout the cytoplasm would not affect the acetylation state of OTC, a strictly mitochondrial protein. Western blot analysis revealed that the total acetylation state of OTC, and K88 in particular, are decreased when Sirt3 was coexpressed, but not when OTC was expressed with Sirt2. Taken together, these findings indicate that Sirt3 is capable of regulating the overall acetylation state (and K88 specifically) of mitochondrial OTC.

Sirt3 catalytic activity is necessary for OTC deacetylation

To verify that OTC deacetylation requires the catalytic activity of Sirt3, we assayed the ability of an enzymatically impaired version of Sirt3, Sirt3 H248Y (Schwer et al., 2006), to affect the acetylation state of OTC. Wild type or H248Y Sirt3 was transiently transfected into HEK293 cells, and the acetylation state of OTC was probed via immunoprecipitation assays in combination with western blot analysis (Figure 3D). In cells expressing OTC alone, a robust band of acetylated OTC was detected (Figure 3D; lane 2). As shown in lane 1, treatment of OTC-expressing cells with nicotinamide (a general sirtuin inhibitor) increased acetylation over OTC transfection alone. Immunoprecipitation of OTC in cells where Sirt3 was coexpressed revealed diminished acetylation below that of OTC transfection alone (lanes 2 and 3), further supporting the finding that Sirt3 deacetylates OTC. When catalytically impaired Sirt3 H248Y was coexpressed with OTC (Figure 3D; lane 4), acetylation levels were similar to those of OTC expressed alone, suggesting the catalytic activity of Sirt3 was necessary for OTC deacetylation. Thus, the interaction of Sirt3 and OTC, the specificity of Sirt3 for OTC deacetylation, and the requirement of Sirt3 catalytic activity provide strong evidence that OTC is a Sirt3 substrate in vivo.

Next, we investigated how OTC activity is altered by Sirt3-catalyzed deacetylation. OTC and either Sirt3, Sirt4, or Sirt5 were transiently cotransfected into HEK293 cells, and activity and acetylation state was assessed from OTC immunoprecipitated from mitochondrial extracts (Figure 3E and F). Only when OTC was coexpressed with Sirt3, and not the other mitochondrial sirtuins Sirt4 and Sirt5, was OTC acetylation decreased (Figure 3E). Furthermore, only when OTC was coexpressed with Sirt3 was a significant increase in OTC activity observed, whereas Sirt4 and Sirt5 failed to significantly alter OTC activity (Figure 3F).

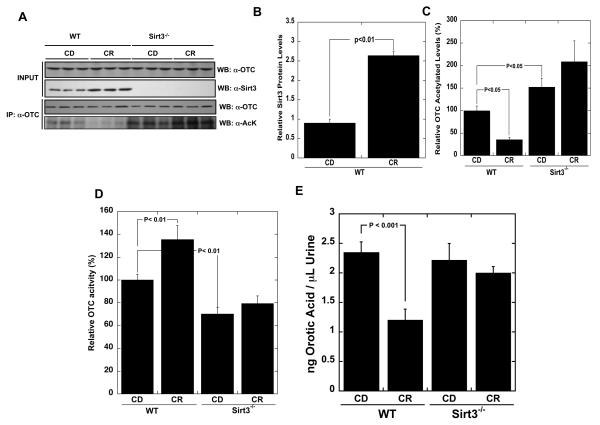

Sirt3 activates OTC in murine liver mitochondria

To this point, we have provided substantial evidence that Sirt3-mediated deacetylation stimulates OTC activity in cultured cells. Next, we investigated if Sirt3 regulates OTC as liver mitochondria adapt to caloric restriction (CR). Mice under CR up-regulate their levels of Sirt3, allowing us to assess directly the impact of Sirt3 activity on the function of OTC (Figure 4A). We postulated that CR, which would require enhanced amino-acid catabolism (Hagopian et al., 2003), would stimulate the urea cycle at least in part via deacetylation of OTC. Murine liver mitochondria were isolated from wild type and sirt3−/− mice and cohorts from each strain were subjected to CR or a control diet (CD). Mitochondrial extracts were prepared from the four populations of mice and probed for OTC acetylation (Figure 4A). In wild type mice, CR induced an ~3-fold increase in Sirt3 protein levels (Figure 4 A-B) and caused a near complete loss of acetylation of OTC compared to the control diet (Figure 4A, C). In sirt3−/− mice, OTC was hyperacetylated and CR failed to stimulate a decrease in OTC acetylation (Figure 4A, C). Yet, in both wild type and sirt3−/− mice under both diets, OTC protein levels remained unchanged (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. In response to caloric restriction, Sirt3 deacetylates OTC and stimulates the urea cycle.

(A) Top panels: Western blot analysis of Sirt3 and OTC levels in livers from 5-month old wild type or sirt3−/− mice fed either control (CD) or calorie restricted (CR) diet. Each lane presents an individual animal. Lower panels: Endogenous acetylated OTC was isolated by immunoprecipitation with anti-OTC antibody followed by western blotting with anti-acetyl-lysine antibody (n = 3). (B-C) Quantification of total Sirt3 protein (B) and OTC acetylation (C) from (A). Error bars represent standard error measurement (SEM) (n=3) Western blot was normalized with Sirt3 levels or OTC levels quantified and analyzed by Image software (n = 3). D.) OTC activity was measured in wild type and sirt3−/− mice fed control or CR diet. Error bars represent standard error measurement (SEM) (n = 5). E.) Orotic acid was measured in wild type and sirt3−/− mice fed control or CR diet. Error bars represent standard error measurement (SEM) (n = 5). * signifies a p < 0.05.

Next we measured OTC activity in the four sets of mitochondrial samples. Consistent with the inhibitory effect of OTC acetylation and a positive regulatory role for Sirt3, acetylation inversely correlated with OTC activity. Most significantly, wild type animals displayed an increase (35%) in OTC activity under CR; but the sirt3−/− animals failed to stimulate OTC activity in response to CR (Figure 4D). Compared to wild type mice, OTC activity from sirt3−/− animals generally displayed higher overall acetylation and lower overall activity, though only the control diet measurements reached statistical significance (i.e., p <0.05) (Figure 4A, C & D). Western blot analysis revealed that OTC protein levels were unchanged in sirt3−/− mice compared to control mice, and unchanged between diets, indicating that OTC activity is regulated post-translationally (Figure 4A). These data suggest that sirt3−/− mice lack the active mitochondrial deacetylase to stimulate OTC activity in response to CR, leading to decreased activity from hyperacetylation and a functional deficiency in OTC.

To evaluate the physiological outcome of an inability of sirt3−/− mice to stimulate the urea cycle under CR, orotic acid levels in urine were determined using an HPLC method. Elevated orotic acid (orotic aciduria) is a reliable clinical marker of OTC deficiency (Finkelstein et al., 1990). When flux through OTC is decreased during urea cycle dysfunction, a subsequent buildup of carbamyol phosphate is then shunted into the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway to form orotic acid (Brosnan and Brosnan, 2007; Seiler et al., 1994a). Consistent with the Sirt3-dependent increase in liver OTC activity (Figure 4D), urinary orotic acid was significantly decreased in response to CR (Figure 4E). In sirt3−/− mice where OTC is not stimulated by Sirt3, orotic acid levels did not decrease in response to CR. These data suggest that during CR, OTC activity is increased by Sirt3-dependent deacetylation, increasing flux through the urea cycle and decreasing the flow of carbamoyl phosphate into orotic acid.

Discussion

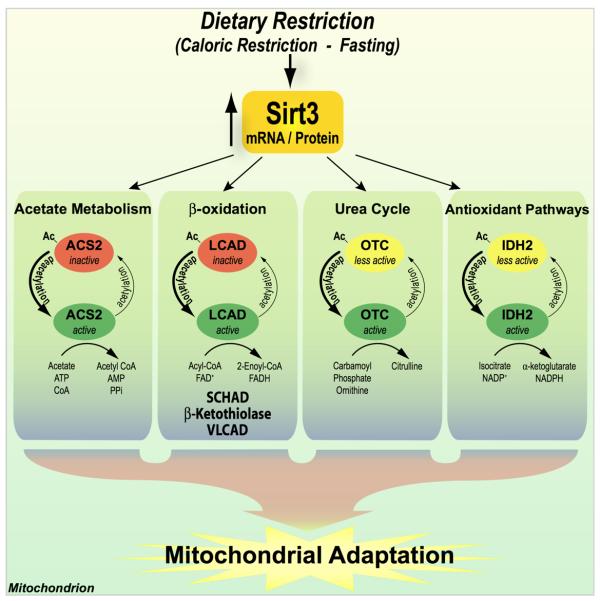

With the recent cataloging of hundreds of acetylated proteins, understanding the biological roles and regulators of acetylation is critical to provide insight into how this previously overlooked modification controls various cellular functions. To begin matching site-specific acetylation with the enzymes responsible, an unbiased screen (SPOT peptide library) of known acetyl-lysine sites from mitochondria was performed, and several high affinity targets of Sirt3 were identified. Combining these results with unbiased, high throughput metabolomic analyses, OTC from the urea cycle and several enzymes of β-oxidation we identified as pathways modulated by Sirt3. Mice lacking Sirt3 (sirt3−/−) displayed a perturbation in numerous acylcarnitines and in urea cycle metabolites. We report a detailed mechanistic investigation that demonstrates the important function of Sirt3 in stimulating the urea cycle in response to dietary stress (fasting and CR). Together, these observations suggest Sirt3 plays an important modulatory role in reprogramming mitochondria towards alternative fuel consumption during dietary stress (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Proposed Regulation of mitochondria function by Sirt3 under dietary restriction.

Fasting and CR results in the up-regulation of Sirt3 levels. Sirt3 functions include the stimulation of enzymatic activities of AceCS1, β-oxidation enzymes, OTC, and IDH2. The coordinated response facilitates mitochondrial adaptation to dietary challenge.

Using cultured cells, Yu et al demonstrated that acetylation of K88 on OTC was dynamic, showing changes in response to dietary treatments (Yu et al., 2009). Lysine 88, which is near the binding site of the carbamoyl phosphate substrate, participates in a network of active-site hydrogen bonding. Acetylation of K88 impairs proper hydrogen bond formation and decreases enzymatic activity (Yu et al., 2009). Here, we demonstrate that Sirt3 is responsible for OTC deacetylation at K88, and its subsequent enzymatic activation. Initially, Sirt3 was identified as a potential regulator of OTC from an unbiased screen based on 240 known mitochondrial acetyl-lysine peptides. Steady-state kinetic analysis demonstrated that Sirt3 but not Sirt5 efficiently deacetylated an acetylated peptide corresponding to K88 of OTC. A similar in vitro result was observed with native acetylated OTC. OTC protein interacts with Sirt3 in mitochondrial extracts, and expression of Sirt3, but not Sirt4, Sirt5 or an impaired catalytic mutant of Sirt3 (H248Y), leads to a reduction in K88 acetylation. Knockdown of Sirt3 protein levels (using siRNA) indicated a marked increase in OTC acetylation. These data provide compelling evidence that Sirt3 is the specific NAD+-dependent deacetylase responsible for deacetylating and modulating the activity of OTC.

Detailed analysis of sirt3−/− and wild type mice under fasting and CR reveals that Sirt3 promotes the urea cycle (amino acid catabolism) during dietary stress. Under CR, Sirt3 protein levels are substantially elevated, leading to the deacetylation and stimulation of OTC. Strikingly, the sirt3−/− mice displayed an inability to deacetylate and stimulate mitochondrial OTC activity in response to CR. Metabolite analysis of wild type and sirt3−/− mice indicated that ornithine, citrulline, aspartate, and argininosuccinate displayed alterations that were entirely consistent with deficiency in OTC activity (Figure S2). These trends are predicted from a reduction of flux through OTC. Stimulated increases in OTC activity were reflected as a dramatic decrease in orotic acid levels in wild type mice under CR. The sirt3−/− animals failed to display a decrease in orotic acid during CR. OTC dysfunction leads to the flow of carbamoyl phosphate into the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway, and the subsequence buildup of orotic acid in the urine. The combined changes in urea cycle metabolites and orotic acid suggest that the urea cycle was restricted in the sirt3−/− animals, and that decreased flux is a direct result of the inability to deacetylate OTC. Therefore, the Sirt3-dependent deacetylation and activation of OTC is essential for the proper functioning of the urea cycle in response to dietary restriction.

Interestingly, Sirt5 had been implicated in urea cycle regulation. Sirt5 was reported to deacetylate and activate carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) in liver mitochondria (Nakagawa et al., 2009). Like Sirt3, fasting conditions lead to Sirt5 mRNA increases (Ogura et al., 2010), yet whereas Sirt3 protein levels increase during fasting and CR, Sirt5 protein levels do not change in response to a 48 hour fast or CR (Nakagawa et al., 2009). Further biochemical analysis is needed to understand the mechanism by which CPS1 is inhibited by acetylation. The specific site(s) of Sirt5-dependent deacetylation on CPS1 have not been identified. It will be important to understand the differences in regulatory mechanisms that affect Sirt3 and Sirt5 activities. Increased Sirt3 protein levels in response to CR appear to explain the increased deacetylation of OTC by Sirt3 (this study and (Schwer et al., 2006) and (Someya et al., 2010)). Because no changes in protein levels were apparent for CPS1, NAD+ fluctuations were proposed to affect the Sirt5-dependent deacetylation of CPS1 (Nakagawa et al., 2009).

The hypothesis that Sirt3 is a central metabolic modulator and functions to reprogram mitochondrial pathways during dietary stress is supported by additional data (Figure 5). Our SPOT peptide analyses in combination with the blood acylcarnitine analysis reveal a number of mitochondrial enzymes that may be regulated by Sirt3. These include essential β-oxidation enzymes, SCHAD, ACADSB, βKT, and VLCAD (Figure 1A). Consistent with these observations, another enzyme involved in β-oxidation, LCAD, has been recently identified as a Sirt3 substrate (Hirschey et al., 2010). The possibility that SCHAD, ACADSB, βKT, VLCAD are targets of Sirt3 is supported by the elevated levels of particular acylcarnitines in sirt3−/− animals. The SPOT peptide arrays identified SCHAD and βKT as potential substrates of Sirt3, and blood metabolite analysis showed an increase in malonylcarnitine (C3DC) and 3-hydroxybutyrylcarnitine (C4OH) in sirt3−/− mice. Elevated C3DC and C4OH are indicative of a dysfunction of one or both of these enzymes (Catanzano et al., 2010; Clayton et al., 2001). Also, an increase in tetradecanoylcarnitine (C14), tetradecenoylcarnitine (C14:1), palmitoylcarnitine (C16), and palmitoleylcarnitine (C16:1) are all indicative of a dysfunction in VLCAD (Primassin et al., 2008). Together, the increases in acylcarnitines from the fasted sirt3−/− mice suggest that Sirt3 acts as a positive modulator of β-oxidation at multiple points throughout the cycle.

The observation that Sirt3 is upregulated during fasting and CR (Barger et al.,2008; Hirschey et al., 2010; Schwer et al., 2009; Someya et al., 2010)combined with a corresponding stimulation of the urea cycle and fatty-acid oxidation, provides compelling evidence that Sirt3 modulates the reprogramming of mitochondrial pathways during dietary stress (Figure 5). In support for the importance of Sirt3 during caloric restriction, we recently demonstrated that Sirt3 plays a critical role in preventing age-related hearing loss during caloric restriction (Someya et al., 2010). We show that stimulation of mitochondrial IDH2 by Sirt3-dependent deacetylation is critical for mitochondria to mitigate oxidative damage. Under lean conditions, the body must adapt to poor glucose availability, and stimulate alternative pathways for energy production, such as fatty-acid oxidation and amino-acid catabolism. Increased flux through the urea cycle is essential to keep pace with the ammonia generated from amino-acid breakdown. Sirt3 may function as a mitochondria-wide mediator in the metabolic shift to lean fuel inputs. The observation that polymorphisms in human Sirt3 have been linked to survivorship among the elderly (Bellizzi et al., 2005; Rose et al., 2003) suggests a positive effect of Sirt3 activity on parameters that influence aging. We propose a model in which Sirt3 modulates the ability of mitochondria to adapt to low energy input (during fasting and CR), including promotion of amino-acid catabolism, β-oxidation and acetate recycling (Figure 5). Acetate recycling is an important energy source during fasting. Fasted AceCS2−/− mice are hypothermic, have reduced ATP levels and show reduced exercise tolerance (Sakakibara et al., 2009). AceCS2 is a substrate for Sirt3 (Hallows et al., 2006; Schwer et al., 2006). Under low energy conditions, Sirt3 would be predicted to activate AceCS2, increasing acetate metabolism (Hallows et al., 2006; Schwer et al., 2006). Consistent with the idea of global mitochondrial regulation, decreased ATP levels and mitochondrial electron potential have been reported in the sirt3−/− mouse (Ahn et al., 2008). Moreover, Sirt3 was shown to regulate the transition from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation in a transformed cell line (Shulga et al., 2010). The ability of Sirt3 to upregulate the anti-oxidant pathway via IDH2 is in accord with the greater need to deal with reactive oxygen species generated from enhanced oxidative phosphorylation (Figure 5) (Someya et al., 2010). Here we demonstrate Sirt3 regulates the shift to amino-acid and fatty-acid catabolism in response to fasting and CR (Figure 5). As CR is the only known environmental intervention that strongly increases maximum life span and retards aging in mammals (Weindruch and Walford, 1988), it is logical to propose a vital function of Sirt3 in the health benefits of CR.

Lastly, though there is strong evidence for a critical role of sirtuin-dependent protein deacetylation in mitochondria, the acetyltransferase(s) responsible for adding the acetyl group to these targets remains unknown. To complete our understanding of reversible acetylation in mitochondria, the mechanism of acetylation will be an important component to grasp regulation, not only for the urea cycle, but the other major mitochondrial processes.

Experimental Procedures

SPOT peptide library synthesis and screening for Sirt3 binding

Synthesis of the SPOT peptide libraries and Sirt3 screening methods were performed as described (Smith et. al.,2010).

Immunoprecipitation assays

OTC and Sirt3 were cotransfected into HEK293 cells and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with IgG antibody or FLAG beads (Sigma) overnight at 4°C, then boiled with SDS loading buffer and subjected to western blotting. OTC-FLAG, Sirt3-HA, Sirt3-FLAG, OTC-MYC were detected as indicated. Mitochondrial lysates from wild type and sirt3−/− mice were performed with anti-Sirt3 antibody (gift of Dr. Eric Verdin, UCSF) or anti-OTC antibody (Aviva Systems Biology; 1:500) overnight at 4°C, then added with Protein A/G beads for 4h followed by western blotting using anti-acetyl-lysine antibody (generated following the procedure of Zhao et al., 2010, GeneTel Laboratories LLC, Madison, WI).

Sirtuin activity assays

Sirtuin activity was determined as described (Smith et al., 2009). OTC-MYC was transfected into HEK293 cells, which were then treated with 5 mM nicotinamide for 16 hours. Nicotinamide is a widely used sirtuin inhibitor. OTC from cell lysates was immunoprecipitated with anti-MYC beads at 4 °C for 2 hours, then OTC-MYC on beads was utilized in 200 μl deacetylation buffer (Tris, pH 7.5, with or without 1 mM NAD+, and 1 mM DTT) and incubated with purified 50 nM purified Sirt3 or Sirt5 (Hallows et al., 2006; Schwer et al., 2006) at 37°C for 1 hour. Aliquots were removed for OTC activity assay and western blotting with anti-MYC antibody or anti-acetyl-lysine antibody.

Liver sample preparation for MS analysis

The samples were desiccated, and 20 mg of dry weight liver tissue was extracted with 1mL of 80:20 acetonitrile:H2O with 1% formic acid (EM, Gibbstown, NJ). Acetonitrile and water were obtained from Burdick & Jackson, Morristown, NJ. The solution was bead beaten (Mini-BeadBeater, Glen Mills, Inc., Clifton, NJ) for 10 minutes and pelleted at 13,000 × g. Aliquots of the supernatant (50 μL), which corresponded to extract from 1 mg of tissue, were dried by rotary vacuum evaporation and stored at −80 °C. Samples were re-dissolved in 90:10 acetonitrile:150 mM ammonium formate (Sigma-Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) buffer (pH 3.0) prior to LC-MS analysis.

LC–MS Analysis

The HPLC system consisted of an LC Packings Famos autosampler and a UltiMate solvent pump (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). A 150 × 0.320 mm, poly (hydroxyethyl) aspartamide capillary column (The Nest Group, Inc. Southborough, MA) with 5-μm particle size and 100-Å pore size was used for separation of the analytes. The 52-min binary gradient elution profile was as follows: t = 0, 100% B; t = 5, 100% B; t = 25, 35% B; t = 26, 0% B; t = 36, 0% B; t = 37, 100% B; and t = 52, 100% B. Mobile phase A was 15 mM ammonium formate buffer (pH 3.0) and mobile phase B was 90% acetonitrile:10% 150 mM ammonium formate. The flow rate was 4 μL/min, and sample injection volumes were 10 μL. The LC effluent was directed to the capillary electrospray ionization source of a Micro-TOF time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA). Positive ion mode electrospray was performed with a potential of 4500 V using 1.0 bar N2 as a nebulizer gas and 4.6 L/min. N2 drying gas at 200 °C.

Blood metabolites and LC-MS analysis

Blood was spotted and analyzed by standard screening protocol. Briefly, 75 μL of blood from a mouse was spotted onto blood analysis sheets. Blood metabolite analysis was carried out at the University of Wisconsin-Madison newborn screening facility by Tandem Mass Spectrometry according to published protocols (Hoffman and Laessig, 2003).

Urinary orotic acid analysis

Urine from mice was analyzed by HPLC. Briefly, ~75-200 μL of urine was collected from mice and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. HPLC analysis of orotic acid was carried out as described by Seiler et al (1994b) and quantitation was performed with orotic acid standards (Hoffman and Laessig, 2003; la Marca et al., 2003; Seiler et al., 1994b).

Full details of all other experimental procedures are given in the Supplemental Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Denu Lab for thoughtful conversations, Brynne Stanton for assistance with manuscript preparation, and Gary Hoffman for assistance with blood metabolites. NMR data were collected at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison (NMRFAM) funded by NIH grants (P41 RR02301 and P41 GM GM66326). This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant number (GM065386) and a Wisconsin Partnership grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes one table, two figures, Supplemental Experimental Procedures, and Supplemental References and can be found with this article online at

References

- Ahn BH, Kim HS, Song S, Lee IH, Liu J, Vassilopoulos A, Deng CX, Finkel T. A role for the mitochondrial deacetylase Sirt3 in regulating energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14447–14452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803790105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J, Lu Z, Joseph JJ, Carabenciov D, Dimond CC, Pang L, Samsel L, McCoy JP, Jr., Leclerc J, Nguyen P, et al. Characterization of the murine SIRT3 mitochondrial localization sequence and comparison of mitochondrial enrichment and deacetylase activity of long and short SIRT3 isoforms. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110:238–247. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger JL, Kayo T, Vann JM, Arias EB, Wang J, Hacker TA, Wang Y, Raederstorff D, Morrow JD, Leeuwenburgh C, et al. A low dose of dietary resveratrol partially mimics caloric restriction and retards aging parameters in mice. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellizzi D, Rose G, Cavalcante P, Covello G, Dato S, De Rango F, Greco V, Maggiolini M, Feraco E, Mari V, et al. A novel VNTR enhancer within the SIRT3 gene, a human homologue of SIR2, is associated with survival at oldest ages. Genomics. 2005;85:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan ME, Brosnan JT. Orotic acid excretion and arginine metabolism. J Nutr. 2007;137:1656S–1661S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.6.1656S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzano F, Ombrone D, Di Stefano C, Rossi A, Nosari N, Scolamiero E, Tandurella I, Frisso G, Parenti G, Ruoppolo M, et al. The first case of mitochondrial acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase deficiency identified by expanded newborn metabolic screening in Italy: the importance of an integrated diagnostic approach. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-9028-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, Olsen JV, Mann M. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton PT, Eaton S, Aynsley-Green A, Edginton M, Hussain K, Krywawych S, Datta V, Malingre HE, Berger R, van den Berg IE. Hyperinsulinism in short-chain L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency reveals the importance of beta-oxidation in insulin secretion. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:457–465. doi: 10.1172/JCI11294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donmez G, Guarente L. Aging and disease: connections to sirtuins. Aging Cell. 2010;9:285–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein JE, Hauser ER, Leonard CO, Brusilow SW. Late-onset ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency in male patients. J Pediatr. 1990;117:897–902. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon N. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency: a urea cycle defect. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2003;7:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s1090-3798(03)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian K, Ramsey JJ, Weindruch R. Caloric restriction increases gluconeogenic and transaminase enzyme activities in mouse liver. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:267–278. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigis MC, Mostoslavsky R, Haigis KM, Fahie K, Christodoulou DC, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Karow M, Blander G, et al. SIRT4 inhibits glutamate dehydrogenase and opposes the effects of calorie restriction in pancreatic beta cells. Cell. 2006;126:941–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigis MC, Sinclair DA. Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:253–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallows WC, Lee S, Denu JM. Sirtuins deacetylate and activate mammalian acetyl-CoA synthetases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10230–10235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604392103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Goetzman E, Jing E, Schwer B, Lombard DB, Grueter CA, Harris C, Biddinger S, Ilkayeva OR, et al. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation by reversible enzyme deacetylation. Nature. 2010;464:121–125. doi: 10.1038/nature08778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman GL, Laessig RH. Screening newborns for congenital disorders. Wmj. 2003;102:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JY, Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Ho L, Verdin E. Mitochondrial sirtuins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:1645–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Galonek H, Israelian K, Choy W, Morrison M, Xia Y, Wang X, Xu Y, Yang Y, Smith JJ, et al. Biochemical characterization, localization, and tissue distribution of the longer form of mouse SIRT3. Protein Sci. 2009;18:514–525. doi: 10.1002/pro.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SC, Sprung R, Chen Y, Xu Y, Ball H, Pei J, Cheng T, Kho Y, Xiao H, Xiao L, et al. Substrate and functional diversity of lysine acetylation revealed by a proteomics survey. Mol Cell. 2006;23:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- la Marca G, Casetta B, Zammarchi E. Rapid determination of orotic acid in urine by a fast liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometric method. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:788–793. doi: 10.1002/rcm.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SJ, Defossez PA, Guarente L. Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for lifespan extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2000;289:2126–2128. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard DB, Alt FW, Cheng HL, Bunkenborg J, Streeper RS, Mostoslavsky R, Kim J, Yancopoulos G, Valenzuela D, Murphy A, et al. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT3 regulates global mitochondrial lysine acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8807–8814. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01636-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Lomb DJ, Haigis MC, Guarente L. SIRT5 Deacetylates carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 and regulates the urea cycle. Cell. 2009;137:560–570. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North BJ, Schwer B, Ahuja N, Marshall B, Verdin E. Preparation of enzymatically active recombinant class III protein deacetylases. Methods. 2005;36:338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura M, Nakamura Y, Tanaka D, Zhuang X, Fujita Y, Obara A, Hamasaki A, Hosokawa M, Inagaki N. Overexpression of SIRT5 confirms its involvement in deacetylation and activation of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primassin S, Ter Veld F, Mayatepek E, Spiekerkoetter U. Carnitine supplementation induces acylcarnitine production in tissues of very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase-deficient mice, without replenishing low free carnitine. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:632–637. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31816ff6f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G, Dato S, Altomare K, Bellizzi D, Garasto S, Greco V, Passarino G, Feraco E, Mari V, Barbi C, et al. Variability of the SIRT3 gene, human silent information regulator Sir2 homologue, and survivorship in the elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:1065–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara I, Fujino T, Ishii M, Tanaka T, Shimosawa T, Miura S, Zhang W, Tokutake Y, Yamamoto J, Awano M, et al. Fasting-induced hypothermia and reduced energy production in mice lacking acetyl-CoA synthetase 2. Cell Metab. 2009;9:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Bunkenborg J, Verdin RO, Andersen JS, Verdin E. Reversible lysine acetylation controls the activity of the mitochondrial enzyme acetylCoA synthetase 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10224–10229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603968103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Eckersdorff M, Li Y, Silva JC, Fermin D, Kurtev MV, Giallourakis C, Comb MJ, Alt FW, Lombard DB. Calorie restriction alters mitochondrial protein acetylation. Aging Cell. 2009;8:604–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, North BJ, Frye RA, Ott M, Verdin E. The human silent information regulator (Sir)2 homologue hSIRT3 is a mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylase. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:647–657. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler N, Grauffel C, Daune-Anglard G, Sarhan S, Knodgen B. Decreased hyperammonaemia and orotic aciduria due to inactivation of ornithine aminotransferase in mice with a hereditary abnormal ornithine carbamoyltransferase. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1994a;17:691–703. doi: 10.1007/BF00712011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler N, Grauffel C, Therrien G, Sarhan S, Knoedgen B. Determination of orotic acid in urine. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1994b;653:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)e0409-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulga N, Wilson-Smith R, Pastorino JG. Sirtuin-3 deacetylation of cyclophilin D induces dissociation of hexokinase II from the mitochondria. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:894–902. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Smith BC, Hallows WC, Denu JM. Mechanisms and molecular probes of sirtuins. Chem Biol. 2008;15:1002–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BC, Hallows WC, Denu JM. A continuous microplate assay for sirtuins and nicotinamide-producing enzymes. Anal Biochem. 2009;394:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BC, Settles B, Hallows WC, Craven MW, Denu JM. Sirt3 substrate specificity determined by peptide arrays and machine learning. ACS Chem Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1021/cb100218d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Someya S, Yu W, Hallows WC, Xu J, Vann JM, Leeuwenburgh C, Tanokura M, Denu JM, Prolla Tomas A. Sirt3 Mediates Reduction of Oxidative Damage and Prevention of Age-related Hearing Loss Under Caloric Restriction. Cell. 2010;143:802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Nishigaki Y, Fuku N, Ibi T, Sahashi K, Koga Y. Therapeutic potential of pyruvate therapy for mitochondrial diseases. Mitochondrion. 2007;7:399–401. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;410:227–230. doi: 10.1038/35065638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weindruch R, Walford RW. In: The Retardation of aging and disease by Dietary Restriction. Thomas CC, editor. Springfield; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wendler PA, Blanding JH, Tremblay GC. Interaction between the urea cycle and the orotate pathway: studies with isolated hepatocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;224:36–48. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Cimen H, Han MJ, Shi T, Deng JH, Koc H, Palacios OM, Montier L, Bai Y, Tong Q, et al. NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial protein synthesis by deacetylation of the ribosomal protein MRPL10. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7417–7429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Lin Y, Yao J, Huang W, Lei Q, Xiong Y, Zhao S, Guan KL. Lysine 88 acetylation negatively regulates ornithine carbamoyltransferase activity in response to nutrient signals. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13669–13675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901921200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Xu W, Jiang W, Yu W, Lin Y, Zhang T, Yao J, Zhou L, Zeng Y, Li H, et al. Regulation of cellular metabolism by protein lysine acetylation. Science. 2010;327:1000–1004. doi: 10.1126/science.1179689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.