Abstract

This study explores the effects of cefditoren (CDN) versus amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (AMC) on the evolution (within a single strain) of total and recombined populations derived from intrastrain ftsI gene diffusion in β-lactamase-positive (BL+) and β-lactamase-negative (BL−) Haemophilus influenzae. DNA from β-lactamase-negative, ampicillin-resistant (BLNAR) isolates (DNABLNAR) and from β-lactamase-positive, amoxicillin-clavulanate-resistant (BLPACR) (DNABLPACR) isolates was extracted and added to a 107-CFU/ml suspension of one BL+ strain (CDN MIC, 0.007 μg/ml; AMC MIC, 1 μg/ml) or one BL− strain (CDN MIC, 0.015 μg/ml; AMC MIC, 0.5 μg/ml) in Haemophilus Test Medium (HTM). The mixture was incubated for 3 h and was then inoculated into a two-compartment computerized device simulating free concentrations of CDN (400 mg twice a day [b.i.d.]) or AMC (875 and 125 mg three times a day [t.i.d.]) in serum over 24 h. Controls were antibiotic-free simulations. Colony counts were performed; the total population and the recombined population were differentiated; and postsimulation MICs were determined. At time zero, the recombined population was 0.00095% of the total population. In controls, the BL− and BL+ total populations and the BL− recombined population increased (from ≈3 log10 to 4.5 to 5 log10), while the BL+ recombined population was maintained in simulations with DNABLPACR and was decreased by ≈2 log10 with DNABLNAR. CDN was bactericidal (percentage of the dosing interval for which experimental antibiotic concentrations exceeded the MIC [ft>MIC], >88%), and no recombined populations were detected from 4 h on. AMC was bactericidal against BL− strains (ft>MIC, 74.0%) in DNABLNAR and DNABLPACR simulations, with a small final recombined population (MIC, 4 μg/ml; ft>MIC, 30.7%) in DNABLPACR simulations. When AMC was used against the BL+ strain (in DNABLNAR or DNABLPACR simulations), the bacterial load was reduced ≈2 log10 (ft>MIC, 44.3%), but 6.3% and 32% of the total population corresponded to a recombined population (MIC, 16 μg/ml; ft>MIC, 0%) in DNABLNAR and DNABLPACR simulations, respectively. AMC, but not CDN, unmasked BL+ recombined populations obtained by transformation. ft>MIC values higher than those classically considered for bacteriological response are needed to counter intrastrain ftsI gene diffusion by covering recombined populations.

INTRODUCTION

Mucosal surfaces are colonized by multiple species simultaneously, with an intricate balance between different strains in the oropharynx. Haemophilus influenzae colonizes the nasopharynges of humans as its exclusive host and can be exogenously transmitted to colonize the nasopharynges of new hosts. When migrating endogenously, it is a common etiological agent of community-acquired respiratory tract infections. As many as 80% of healthy persons carry H. influenzae (14), with multiple strains in 50% of samples (22) and a high turnover of strains (17). This colocalization of different strains from the same species allows the emergence and dissemination of resistance. According to a previous study (1), the emergence of resistance to ampicillin (as a marker of resistance) suggests cell-to-cell contact and chromosomal gene transfer. In addition, H. influenzae is naturally able to take up DNA from the environment, and a recent in vitro study has found that the mechanism of in vitro transfer of the ftsI gene involves classical transformation (23). Once resistance is present, dissemination may be favored by antibiotic pressure.

Epidemiological studies have found that the prevalence of H. influenzae isolates with DNA encoding mutations in the ftsI gene (β-lactamase-negative, ampicillin-resistant [BLNAR] and β-lactamase-positive, amoxicillin-clavulanate-resistant [BLPACR] strains) is increasing in countries such as Japan, Korea, Spain, and even Norway (7, 10, 18, 21). In Spain, the increase in the prevalence of BLNAR strains has been linked to the consumption of aminopenicillins (6, 7), such as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, which is among the highest in Europe (9). Furthermore, the higher proportion of BLPACR strains (among strains with ftsI mutations) reported for children than for adults in a recent multicenter surveillance in Spain (20) might also be associated with the higher frequencies of nasopharynx cocolonization with multiple H. influenzae strains (22) and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid consumption in children than in adults.

Since the dynamics of the different populations (H. influenzae strains) in antibiotic-free environments are the baseline that antibiotic treatments can alter (8), the aim of this study was to explore the effect of physiological free concentrations of cefditoren versus amoxicillin-clavulanic acid on the evolution, within a single β-lactamase-positive or -negative H. influenzae strain, of total and recombined (by transformation) populations derived from intrastrain ftsI gene diffusion.

(The results of this study were presented in part at the 50th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Boston, MA, 12 to 15 September 2010.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Characteristics of strains used in the study.

The isolates used in this study were chosen from the strain collection of a previously published study (20), based on the most frequent pattern of ftsI gene substitutions among BLPACR strains, and on similarity to this pattern among BLNAR strains, always considering the cefuroxime MIC (see below).

Table 1 shows the four H. influenzae strains used in this study, the modal values of MICs and minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) determined five times according to CLSI (formerly NCCLS) recommendations (4, 15), and substitutions in the ftsI gene and the presence of the TEM-1 gene as determined by PCR and direct sequencing (5, 19). Strains (one β-lactamase negative [BL−] and one β-lactamase positive [BL+]) with no mutations in the ftsI gene were used as recipient strains, and strains (one BL− and one BL+) that show the ftsI gene substitutions listed in Table 1 were used as DNA donors. The higher cefuroxime MICs for strains harboring ftsI gene mutations were used to distinguish the growth of the recombined population from that of the total population over the simulation process by the addition of 2 μg/ml of cefuroxime to the agar medium in plates (GC agar [BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD] supplemented with 5% sheep blood [Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom], added at 50°C, and VX growth factors [BD Diagnostics] [GCSA]).

Table 1.

Susceptibility phenotypes and genotypes of the four strains used in this study

| Straina | MIC/MBC (μg/ml)b |

ftsI gene substitutions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | CXM | AMC | CDN | ||

| Recipient strains | |||||

| BL− | 1/1 | 0.5/0.5 | 0.5/1 | 0.015/0.015 | |

| BL+ (TEM-1) | 32/128 | 0.5/1 | 1/2 | 0.007/0.03 | |

| DNA donor strains | |||||

| BLNAR | 8/8 | 8/8 | 8/16 | 0.015/0.03 | D350N, M377I, G490E, A502V, N526K, V545I |

| BLPACR (TEM-1) | >128/>128 | 8/16 | 4/32 | 0.03/0.06 | D350N, M377I, A502V, N526K, V545I |

BL−, β-lactamase negative (ampicillin susceptible); BL+, β-lactamase positive; BLNAR, β-lactamase negative, ampicillin resistant; BLPACR, β-lactamase positive, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid resistant.

AMP, ampicillin; CXM, cefuroxime; AMC, amoxicillin-clavulanate; CDN, cefditoren.

After the in vitro simulation process, at least two colonies per plate containing 2 μg/ml of cefuroxime were selected from each simulation, and the MICs of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and cefditoren, as well as the ftsI sequences, were determined using the methods referenced above. The TEM-1 sequence was also investigated in simulations of the BL− strain with DNA from the BLPACR strain in order to explore possible transmission of the TEM-1 gene. MICs were determined five times, and modal values were considered.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as described previously on recipient and donor strains and on the recombined population grown in plates with 2 μg/ml of cefuroxime (13).

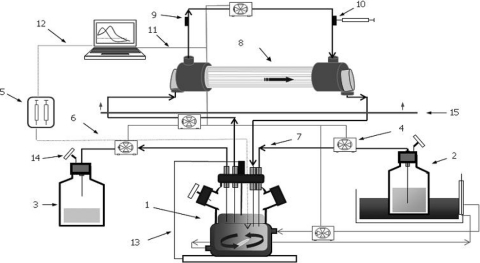

In vitro kinetic model.

A dynamic two-compartment system described previously (2) was used (Fig. 1). The central compartment consists of a spinner flask, the lumina of the capillaries within the dialyzer (FX50 class; Fresenius Medical Care S.A., Barcelona, Spain), and the tubing in between. The infection site was represented by the extracapillary space of the dialyzer unit plus the tubing inside the dialyzer. The high surface area-to-volume ratio of the dialysis unit (>200 cm2/ml) yields a rapid equilibration of the concentration of the antimicrobial agent between the two compartments.

Fig. 1.

In vitro pharmacodynamic device. Components are as follows: 1, central compartment (spinner flask, tubing, and lumen of capillary); 2, fresh-broth reservoir; 3, elimination; 4, peristaltic pumps; 5, syringe pump; 6, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tubing; 7, silicone tubing; 8, infection compartment (extracapillary space); 9, inoculation port; 10, sample port; 11, RS-232 connection; 12, Gilson serial input/output channel (GSIOC) connection; 13, temperature probe; 14, air filter; 15, incubator.

Before each experiment, the central compartment was filled with Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 15 μg/ml NAD (factor V), 15 μg/ml hemin (factor X), and 5 μg/ml of yeast extract (Haemophilus Test Medium [HTM]) (BD Diagnostics). A computer-controlled syringe pump (402 Dilutor-Dispenser; Gilson S.A., Villiers-le-Bel, France) was used to inject study drugs into the central compartment to reach the target maximum concentration (Cmax) at the target Tmax (time to obtain Cmax). The monoexponential decay of cefditoren or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid concentrations in the central compartment was achieved by a continuous dilution-elimination process using computerized peristaltic pumps (Masterflex; Cole-Parmer Instrument Co., Chicago, IL) at rates of 2.61 and 3.52 ml/min, respectively, to simulate their respective half-lives (t1/2) in human serum (1.55 h for cefditoren and 1.15 h for amoxicillin-clavulanic acid) (8, 11, 12). Flow rates set in the peristaltic pumps were controlled using WinLIN software, version 2 (Masterflex; Cole-Parmer Instrument Co.).

Control antibiotic-free simulations were performed using a fixed rate of 3.52 ml/min in peristaltic pumps. Both compartments were maintained at 37°C during the simulation process.

Kinetic simulations.

Free concentrations in serum after an oral twice-daily regimen of 400 mg cefditoren-pivoxil (11, 12) or an oral three-times-daily regimen of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid at 875 and 125 mg (8), calculated considering protein binding levels of 88% (25) and 18 and 25% (8), respectively, were simulated over 24 h. Target free concentrations and pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 2. The target Tmax was 1.5 h for amoxicillin and clavulanic acid and 2.45 h for cefditoren. The half-life of the combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid in the system was adjusted to the clavulanic acid half-life (1.15 h).

Table 2.

Target and experimental mean free antibiotic concentrations, pharmacokinetic parameters, and ft>MIC for recipient strains after the first antibiotic dose, determined in simulations carried out with the BL− or the BL+ straina

| Parameter | Value for: |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cefditoren |

Amoxicillin |

Clavulanic acid |

|||||||

| Target | BL− strain | BL+ strain | Target | BL− strain | BL+ strain | Target | BL− strain | BL+ strain | |

| Cmax (μg/ml)b | 0.50 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 9.51 | 9.86 ± 0.54 | 9.54 ± 0.84 | 1.65 | 1.68 ± 0.33 | 1.64 ± 0.19 |

| Mean free antibiotic concn (μg/ml) at: | |||||||||

| 2 h | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.41 ± 0.08 | 7.04 | 7.05 ± 0.41 | 6.89 ± 0.47 | 1.22 | 1.30 ± 0.25 | 1.12 ± 0.12 | |

| 4 h | 0.29 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 2.11 | 2.39 ± 0.08 | 0.71 ± 0.29* | 0.37 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.09 |

| 6 h | 0.12 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.63 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 0.03 ± 0.01* | 0.11 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| 8 h | 0.05 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.19 | UDL | UDL | 0.03 | UDL | UDL |

| 10 h | 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | ||||||

| 12 h | 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | UDL | ||||||

| AUC (mg · h/liter)c | 1.79 | 1.77 ± 0.09 | 1.76 ± 0.15 | 22.59 | 22.61 ± 1.06 | 17.03 ± 0.48* | 3.91 | 3.93 ± 0.57 | 3.57 ± 0.27 |

| t1/2 (h) | 1.55 | 1.53 ± 0.01 | 1.46 ± 0.18 | 1.15 | 1.07 ± 0.05 | 0.53 ± 0.07* | 1.15 | 1.27 ± 0.12 | 1.32 ± 0.23 |

| ft>MIC (%) | 88.23 | 83.05 | 74.04d | 44.31d | |||||

BL−, β-lactamase negative, ampicillin susceptible; BL+, β-lactamase positive. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.001) between values for the BL+ strain and the target and between values for the BL+ and BL− strains. UDL, under the detection limit.

The Tmax was 2.75 h for cefditoren and 1.5 h for amoxicillin and clavulanic acid.

AUC0–12 for cefditoren and AUC0–8 for amoxicillin and clavulanic acid.

The ft>MIC for amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was calculated on the basis of amoxicillin.

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis.

For the measurement of simulated antimicrobial concentrations, aliquots (0.5 ml) were taken from the peripheral compartment at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h and at the time corresponding to the target Tmax of each antimicrobial in all antibiotic simulations. All samples were stored at −50°C until use. Concentrations were determined by bioassays (8) using Morganella morganii ATCC 8076H as the indicator organism for cefditoren (linear concentrations from 0.007 to 1 μg/ml; limit of detection, 0.0035 μg/ml), Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341 for amoxicillin (linear concentrations from 0.03 to 1 μg/ml; limit of detection, 0.03 μg/ml), and Klebsiella pneumoniae NCTC 11228 for clavulanic acid (linear concentrations from 0.06 to 4 μg/ml; limit of detection, 0.06 μg/ml) concentrations. Standards and dilutions, if required, were prepared in the same broth employed in the pharmacokinetic simulation and were added to wells in the plates with an even lawn of the indicator organism. Plates were incubated for 18 to 24 h at 37°C. Intraday and interday coefficients of variation were 4.03% and 8.58% for cefditoren (0.75 μg/ml) and 3.51% and 3.73% for amoxicillin (0.4 μg/ml), respectively; both were 3.10% for clavulanic acid (0.8 μg/ml).

Antimicrobial concentrations were analyzed by a noncompartmental approach using the WinNonlin Professional program, version 5.2 (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA). Cmax and Tmax were obtained directly from observed data. The area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) from 0 to 8 h (AUC0–8) was calculated for amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and the AUC0–12 was calculated for cefditoren, by the linear-log trapezoidal rule.

For recipient strains, donor strains, and recombined populations (if recovered at the end of simulations), the percentage of the dosing interval for which the experimental antibiotic concentrations exceeded the MIC (ft>MIC) was calculated with the mean concentrations determined in the first dosing interval in all antibiotic simulations by a noncompartmental approach for pharmacodynamic data using the WinNonlin Professional program (Pharsight Co.).

DNA extraction from the BLNAR and BLPACR donor strains.

DNA was extracted using a QIAmp kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) from a 108-CFU/ml bacterial suspension in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Preparation of inocula.

A bacterial suspension of approximately 1 × 108 CFU/ml in PBS from an overnight culture in GCSA agar (BD Diagnostics) as measured by a UV spectrophotometer (Cintra 10; GBC Scientific Equipment, Madrid, Spain) was prepared. A 0.7-ml aliquot of the suspension was further diluted in 7 ml of HTM broth and was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Afterwards, the extracted DNA from the BLNAR strain (DNABLNAR) or from the BLPACR strain (DNABLPACR) was added to a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. This amount of DNA corresponded approximately to the total amount of DNA contained in ≈1 × 107 CFU/ml viable cells of donor strains, ensuring a 1:1 ratio of extracted DNA to DNA in viable recipient cells at the beginning of the simulations. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The same procedure without the addition of DNA was used for the preparation of inocula for control experiments. The recombination frequencies were assessed by determination of viable counts in GCSA plates supplemented with 2 μg/ml cefuroxime (yielding the growth of recombined cells) versus total viable counts in unsupplemented GCSA plates.

Simulations performed.

Different antibiotic-free, cefditoren, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid simulations were performed with the following inocula: (i) the BL− strain (as a control experiment), (ii) the BL+ strain (as a control experiment), (iii) the BL− strain preincubated with DNABLNAR, (iv) the BL− strain preincubated with DNABLPACR, (v) the BL+ strain preincubated with DNABLNAR, and (vi) the BL+ strain preincubated with DNABLPACR.

The bacterial suspension incubated for 3 h with or without the DNA extract (at a 1:1 ratio of extracted DNA to DNA in viable recipient cells) was introduced into the peripheral compartment of the in vitro model 30 min before the simulation was started.

Samples (0.5 ml) from the peripheral compartment were collected at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h, serially diluted in 0.9% sodium chloride, and plated onto unsupplemented GCSA plates and onto GCSA plates containing 2 μg/ml of cefuroxime (to differentiate the recombined subpopulation). Each experiment was performed in triplicate. The limit of detection was 50 CFU/ml.

Statistical analysis.

Intra- and intergroup comparisons of antibiotic concentrations and pharmacokinetic parameters were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), a paired t test, and one t test as appropriate. Due to the multiple comparisons, a P value of <0.001 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the modal values of the MICs and MBCs of the study drugs, as well as the ftsI gene substitutions for the four H. influenzae strains used in this study. Strains (one β-lactamase negative, one β-lactamase positive) with no mutations in the ftsI gene were used as recipient strains, and strains (one β-lactamase negative, one β-lactamase positive) that showed ftsI gene substitutions were used as DNA donors.

Preincubation of strains with DNA produced mean recombination frequencies for the BL− strain of 8.8 × 10−5 in the presence of DNA extracted from the BLNAR strain (DNABLNAR) and 6.2 × 10−4 in the presence of DNA extracted from the BLPACR strain (DNABLPACR); for the BL+ strain, preincubation with either DNABLNAR or DNABLPACR produced a mean recombination frequency of 9.6 × 10−6.

Table 2 shows experimentally measured antibiotic concentrations and pharmacokinetic parameters. No differences between target and experimental concentrations or between target and experimental pharmacokinetic parameters were found in the simulations performed, except for amoxicillin concentrations in simulations with the BL+ strain as the recipient, where the concentrations from 4 h on, the AUC, and the t1/2 showed significantly (P < 0.0001) lower experimental than targeted values. Due to this difference, significant differences were found between the amoxicillin data obtained in BL− simulations and those obtained in BL+ simulations, as shown in Table 2. While the concentrations determined at 2 h and at 10 h (2 h after the second dose) were similar (mean values, ≈7.05 ± 0.41 versus ≈7.96 ± 0.56 μg/ml) in simulations with the BL− strain, regardless of the presence or absence of DNA in the simulations, differences were observed in simulations with the BL+ strain between the amoxicillin concentration at 2 h and that at 10 h: mean values of 6.89 ± 0.47 versus 5.44 ± 2.75 μg/ml in simulations without DNA, 7.02 ± 0.50 versus 5.78 ± 2.21 μg/ml in simulations with DNABLNAR, and 7.32 ± 0.67 versus 2.37 ± 0.36 μg/ml in simulations with DNABLPACR.

ft>MIC values (calculated with concentrations determined in the first dosing interval) for cefditoren were >83% for both recipient strains, and ft>MIC values for amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (on the basis of amoxicillin) were 74.04% and 44.31% for the BL− and BL+ strains, respectively, with no differences between calculations using concentrations determined in simulations with or without DNA.

Tables 3 to 5 show colony counts over 24 h for the total and recombined populations determined in antibiotic-free, cefditoren, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid simulations, respectively.

Table 3.

Mean colony counts of the total population and the recombinant subpopulation over 24 h in antibiotic-free simulations carried out with the BL− or the BL+ strain, with or without DNA from the BLNAR or BLPACR donor straina

| Time (h) | Mean colony count (log10 CFU/ml)b |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL− strain] |

BL+ strain |

|||||||||

| Without DNA | With DNABLNAR |

With DNABLPACR |

Without DNA | With DNABLNAR |

With DNABLPACR |

|||||

| Tp | Rp | Tp | Rp | Tp | Rp | Tp | Rp | |||

| 0 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 7.3 ± 0.3 | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 0.0 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

| 2 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 7.9 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 7.7 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

| 4 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 7.6 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| 6 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 7.7 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 1.4 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 7.8 ± 0.3 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | UDL | 8.1 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2 |

| 8 | 7.6 ± 0.6 | 7.8 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 0.2 | UDL | 8.0 ± 0.2 | UDL |

| 10 | 8.1 ± 0.1 | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 7.8 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 7.9 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| 12 | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 7.9 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 7.7 ± 0.6 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 7.8 ± 0.1 | UDL | 8.2 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.6 |

| 24 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 9.0 ± 0.3 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 8.5 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

BL−, β-lactamase negative, ampicillin susceptible; BL+, β-lactamase positive; Tp, total population; Rp, recombinant subpopulation.

UDL, under the detection limit. The MICs of cefditoren for recombinant strains recovered after the simulation process were 0.015 μg/ml for the BL− strain and 0.007 μg/ml for the BL+ strain; those of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid were 4 μg/ml for the BL− strain and 16 μg/ml for the BL+ strain.

Table 5.

Mean colony counts of the total population and the recombinant subpopulation over 24 h in simulations with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid carried out with the BL− or the BL+ strain, with or without DNA from the BLNAR or BLPACR donor straina

| Time (h) | Mean colony count (log10 CFU/ml)b |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL− strain |

BL+ strain |

|||||||||

| Without DNA | With DNABLNAR |

With DNABLPACR |

Without DNA | With DNABLNAR |

With DNABLPACR |

|||||

| Tp | Rp | Tp | Rp | Tp | Rp | Tp | Rp | |||

| 0 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 7.8 ± 0.1 | 7.6 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

| 2 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 4.7 ± 0.7 | UDL | 4.9 ± 0.3 | UDL | 6.3 ± 0.5 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 6.5 ± 0.4 | UDL |

| 4 | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | UDL | 3.4 ± 0.2 | UDL | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | UDL | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| 6 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | UDL | 2.2 ± 0.5 | UDL | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.4 |

| 8 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | UDL | 2.3 ± 0.5 | UDL | 6.2 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.4 |

| 10 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | UDL | 1.9 ± 0.4 | UDL | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | UDL | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| 12 | UDL | 2.2 ± 0.7 | UDL | UDL | UDL | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | UDL | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.4 |

| 24 | UDL | UDL | UDL | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.6 |

BL−, β-lactamase negative, ampicillin susceptible; BL+, β-lactamase positive; Tp, total population; Rp, recombinant subpopulation.

UDL, under the detection limit.

In antibiotic-free simulations, the total bacterial population increased from 0 to 24 h (Table 3). Mean recombined-population/total-population ratios at 24 h were 1.6 × 10−5 and 1 × 10−4 for the BL− strain with DNABLNAR and DNABLPACR, respectively, and 3.2 × 10−7 and 1.3 × 10−6 for the BL+ strain with DNABLNAR and DNABLPACR, respectively. Table 3, footnote b, gives the MICs of cefditoren and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid for the recombined populations recovered after antibiotic-free simulations. While the MICs of cefditoren were equal to those for the recipient strains, the MICs of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid for the recombined populations (Table 3) were markedly higher than those for the recipient strains (Table 1).

With respect to simulations carried out with the study drugs, cefditoren (Table 4) showed bactericidal activity at 24 h (with reductions of >4 log10 CFU/ml from the initial inocula) against the total population in all simulations, regardless of the recipient strain or the DNA used, and recombined populations were not detectable from 4 h on in all the simulations performed. In contrast, there were marked differences in the activity of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Table 5) between the BL− and BL+ simulations. Bactericidal activity against the total population of the BL− strain was achieved in simulations with DNABLNAR or DNABLPACR, with a small recombined population remaining at the end of the simulation with DNABLPACR. In simulations with the BL+ strain as the recipient (regardless of the presence of DNABLNAR or DNABLPACR), the initial inocula of the total population were approximately 2 log10 reduced, but significant counts of the recombined population remained at 24 h (recombined-population/total-population ratios were 6.3 × 10−2 and 3.2 × 10−1 when DNABLNAR and DNABLPACR, respectively, were present in the simulation). The MICs of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid for the recombined populations recovered at 24 h in amoxicillin-clavulanic acid simulations were equal to those for the recombined populations recovered in antibiotic-free simulations at 24 h. The amoxicillin-clavulanic acid ft>MIC calculated with MIC values for the recombined population recovered at 24 h was 30.7% in BL− simulations with DNABLPACR and 0% in BL+ simulations with DNABLNAR or DNABLPACR.

Table 4.

Mean colony counts of the total population and the recombinant subpopulation over 24 h in simulations with cefditoren carried out with the BL− or the BL+ strain, with or without DNA from the BLNAR or BLPACR donor straina

| Time (h) | Mean colony count (log10 CFU/ml)b |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL− strain |

BL+ strain |

|||||||||

| Without DNA | With DNABLNAR |

With DNABLPACR |

Without DNA | With DNABLNAR |

With DNABLPACR |

|||||

| Tp | Rp | Tp | Rp | Tp | Rp | Tp | Rp | |||

| 0 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 7.3 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

| 2 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 0.5 | UDL | 6.4 ± 0.2 | UDL |

| 4 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | UDL | 4.5 ± 1.0 | UDL | 4.9 ± 1.1 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | UDL | 5.9 ± 0.1 | UDL |

| 6 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | UDL | 3.7 ± 1.0 | UDL | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 0.9 | UDL | 4.7 ± 0.2 | UDL |

| 8 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | UDL | 2.8 ± 0.8 | UDL | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | UDL | 3.3 ± 0.4 | UDL |

| 10 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | UDL | 2.6 ± 0.3 | UDL | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | UDL | 2.7 ± 0.2 | UDL |

| 12 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | UDL | 2.4 ± 0.6 | UDL | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | UDL | 2.5 ± 0.4 | UDL |

| 24 | 1.7 ± 0.0 | 1.7 ± 0.0 | UDL | UDL | UDL | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | UDL | 3.0 ± 0.2 | UDL |

BL−, β-lactamase negative, ampicillin susceptible; BL+, β-lactamase positive; Tp, total population; Rp, recombinant subpopulation.

UDL, under the detection limit.

At the end of antibiotic-free or antibiotic simulations, three tests confirmed DNA and cell lineages. (i) PFGE results for the recombined populations were identical to those for recipient strains, showing the same lineage. (ii) The TEM-1 gene was not found in recombined populations recovered in simulations of the BL− strain with DNABLPACR, showing the lack of transference of the TEM-1 gene. (iii) The sequences of the ftsI gene of the recombined populations were always identical to those determined for the BLNAR and BLPACR strains used as DNA donors, showing that transformation had occurred.

DISCUSSION

Heterogenicity in nontypeable H. influenzae is widely recognized (5, 24). H. influenzae is intrinsically competent to take up DNA from the environment (23), as in the nasopharynx, where different H. influenzae strains coexist and intraspecies horizontal transfer occurs (23). Once resistance is acquired by transformation, populations with different resistance genotypes (and different degrees of fitness) may coexist in the same niche. The fitness of a single strain is directly proportional to its ability to compete with other strains and inversely proportional to its clearance (8). There is some evidence that bacterial fitness decreases, at least in the short term, due to resistance, as was shown in a previous study using a pharmacodynamic device similar to that used in the current study, where strains that did not carry resistance traits prevailed after 24-h antibiotic-free simulations (simulating the natural evolution of a mixed inoculum of H. influenzae strains) (8). Different antibiotics unmasked minor populations (such as BLNAR or BLPACR strains) at different rates (8), thus increasing the pool of DNA exhibiting substitutions in the ftsI gene. A previous study explored the effects of different concentrations of several β-lactams in preventing genetic transfer in H. influenzae (24); however, the effects of the different β-lactams on recombined subpopulations compared with those on the total population over dosing intervals remained to be explored.

The present study showed that the recombined populations of the BL− strain (with DNABLNAR and DNABLPACR) in antibiotic-free simulations had good fitness, since these subpopulations did not disappear (in the absence of antibiotic pressure) but increased approximately 1.5 log10 over 24 h. The recombined populations of the BL+ strain (with an additional resistance trait, the production of β-lactamase) showed less fitness: either they did not increase over time (in simulations with DNABLPACR) or they decreased by approximately 1 log10 (in simulations with DNABLNAR). This difference in fitness seems to accord with the higher prevalence of BLNAR than of BLPACR phenotypes in epidemiological studies (6, 16). In a previous in vitro study, the 24-h evolution of antibiotic-free multistrain ecological niches (a β-lactamase negative, a β-lactamase positive, a BLNAR, and a BLPACR strain at 1:1:1:1 as initial inocula), also showed that at 24 h, the strain carrying both resistance traits (TEM β-lactamase and ftsI gene mutations) had the lowest frequency (2%), again demonstrating the relationship between fitness and resistance in H. influenzae (8). From all these data it can be deduced that the accumulation of enzymatic and nonenzymatic resistance traits has an influence on fitness both in subpopulations within a single strain and in strains in multistrain niches.

In the current study, in the presence of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ftsI gene substitutions as the exclusive resistance trait did not offer a competitive advantage, since the recombined subpopulations of the BL− strain were not detectable in simulations with DNABLNAR, and only a small total population (80% of which corresponded to the recombined population) was detected at 24 h in simulations with DNABLPACR. The exclusive presence of β-lactamase offered a relative competitive advantage, since amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was not bactericidal (with <3 log10 reductions from the initial inocula) in BL+ simulations. Was it the accumulation of both resistance traits that offered a competitive advantage? The recombined population increased 1 log10 in simulations with DNABLNAR and 2 log10 in simulations with DNABLPACR; at 24 h, the recombined population represented as much as 6.3% (versus 0.00096% at 0 h) and 32% (versus 0.00095% at 0 h) of the total population recovered in simulations with DNABLNAR and DNABLPACR, respectively. It seems that while the accumulation of these two resistance traits in a strain subpopulation constitutes a competitive disadvantage in antibiotic-free simulations, it confers a competitive advantage in the presence of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, but each resistance trait by itself does not.

In contrast, in the presence of cefditoren, no recombined populations were detectable after a 24-h simulation.

Classically, ft>MIC values of ≥40% have been considered predictive of bacterial eradication, subsequent clinical response, and the prevention of resistance (3). From this pharmacodynamic perspective, in the present study the amoxicillin-clavulanic acid ft>MIC of ≈40% (for the first antibiotic dose) for the BL+ strain can be related to decreases of approximately 2 log10 from the initial inoculum for the total population at 24 h, but 6.33% of the remaining population was a recombined population in simulations with DNABLNAR, and this proportion reached 31.65% in simulations with DNABLPACR. This can be related to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid ft>MIC values of 0% for the recombined population and of 7.07% and 23.97% for the BLNAR and BLPACR strains used as donors (but in both cases, the percentage of the time for which the free concentrations exceeded the MBC was 0%). For the BL− strain, the ft>MIC of approximately 75% was related to the eradication of both total and recombined populations in DNABLNAR simulations, but not in DNABLPACR simulations, where a small (≈2 log10) total population (80% of which consisted of the recombined population) remained at 24 h (ft>MIC for the recombined subpopulation, 30.7%). This suggests that ft>MIC values for recipient strains higher than those classically considered for the prediction of bacteriological response are needed to counter intrastrain ftsI gene diffusion by adequately covering possible recombined subpopulations (ft>MIC values adequate against possible recombined subpopulations will prevent intrastrain ftsI gene diffusion), or, in other words, to counter the fitness of recombined subpopulations. With cefditoren, recombined subpopulations were always eradicated due to the high ft>MIC values obtained regardless of the strain used (recipient strains or donor strains).

Ecology and resistance in human microbiota are related phenomena. The evolution of recombinant subpopulations, responsible for the diffusion of nonenzymatic resistance to β-lactams in H. influenzae, needs to be countered. In the present study, antibiotics such as cefditoren, with high intrinsic activity against H. influenzae regardless of the resistance genotype, exhibited potential for countering recombinant subpopulations, offering epidemiological advantages by limiting the intrastrain diffusion and spread of nonenzymatic resistance mechanisms in H. influenzae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by an unrestricted grant from Tedec-Meiji Farma S.A., Madrid, Spain.

We thank E. Bouza and E. Cercenado (Microbiology Department, Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañon, Madrid, Spain) for permission to use the four strains of this study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Albritton W. L., Setlow J. K., Slaney L. 1982. Transfer of Haemophilus influenzae chromosomal genes by cell-to-cell contact. J. Bacteriol. 152:1066–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alou L., et al. 2005. Is there a pharmacodynamic need for the use of continuous versus intermittent infusion with ceftazidime against Pseudomonas aeruginosa? An in vitro pharmacodynamic model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:209–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ball P., et al. 2002. Antibiotic therapy of community respiratory tract infections: strategies for optimal outcomes and minimized resistance emergence. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 7th ed Approved standard M7–A7. CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dabernat H., et al. 2002. Diversity of beta-lactam resistance-conferring amino acid substitutions in penicillin-binding protein 3 of Haemophilus influenzae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2208–2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. García-Cobos S., et al. 2008. Antibiotic resistance in Haemophilus influenzae decreased, except for beta-lactamase-negative amoxicillin-resistant isolates, in parallel with community antibiotic consumption in Spain from 1997 to 2007. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2760–2766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. García-Cobos S., et al. 2007. Ampicillin-resistant non-beta-lactamase-producing Haemophilus influenzae in Spain: recent emergence of clonal isolates with increased resistance to cefotaxime and cefixime. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2564–2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. González N., et al. 2009. Influence of different resistance traits on the competitive growth of Haemophilus influenzae in antibiotic-free medium and selection of resistant populations by different β-lactams: an in vitro pharmacodynamic approach. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:1215–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goossens H., Ferech M., Vander Stichele R., Elseviers M. for the ESAC Project Group 2005. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 365:579–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim I. S., et al. 2007. Diversity of ampicillin resistance genes and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in Haemophilus influenzae strains isolated in Korea. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:453–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mulford D., Mayer M., Witt G. 2000. Effect of age and gender on the pharmacokinetics of cefditoren, abstr. 310. Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., Toronto, Ontario, Canada American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mulford D., Mayer M., Witt G. 2000. Effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of cefditoren, abstr. 311. Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., Toronto, Ontario, Canada American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murchan S., et al. 2003. Harmonization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for epidemiological typing of strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a single approach developed by consensus in 10 European laboratories and its application for tracing the spread of related strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1574–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murthy T. F. 2005. Haemophilus influenzae, p. 2661–2669 In Mandell G. L., Douglas R. G., Bennett J. E., Dolin R. (ed.), Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases, 6th ed Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards 1999. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents: approved guideline M26-A. NCCLS, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pérez-Trallero E., et al. 2005. Geographical and ecological analysis of resistance, coresistance, and coupled resistance to antimicrobials in respiratory pathogenic bacteria in Spain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1965–1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sá-Leão R., et al. 2008. High rates of transmission of and colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae within a day care center revealed in a longitudinal study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:225–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sanbongi Y., et al. 2006. Molecular evolution of beta-lactam-resistant Haemophilus influenzae: 9-year surveillance of penicillin-binding protein 3 mutations in isolates from Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2487–2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scriver S. R., et al. 1994. Determination of susceptibilities of Canadian isolates of Haemophilus influenzae and characterization of their β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1678–1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sevillano D., et al. 2009. Genotypic versus phenotypic characterization, with respect to beta-lactam susceptibility, of Haemophilus influenzae isolates exhibiting decreased susceptibility to beta-lactam resistance markers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:267–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Skaare D., et al. 2010. Mutant ftsI genes in the emergence of penicillin-binding protein-mediated beta-lactam resistance in Haemophilus influenzae in Norway. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1117–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith-Vaughan H. C., et al. 1996. Carriage of multiple ribotypes of non-encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae in aboriginal infants with otitis media. Epidemiol. Infect. 116:177–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takahata S., et al. 2007. Horizontal gene transfer of ftsI, encoding penicillin-binding protein 3, in Haemophilus influenzae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1589–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Takahata S., Kato Y., Sanbongi Y., Maebashi K., Ida T. 2008. Comparison of the efficacies of oral beta-lactams in selection of Haemophilus influenzae transformants with mutated ftsI genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1880–1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wellington K., Curran M. P. 2004. Cefditoren pivoxil: a review of its use in the treatment of bacterial infections. Drugs 64:2597–2618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]