Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

The organic cation transporters 1 (OCT1) and 2 (OCT2) mediate drug uptake into hepatocytes and renal proximal tubular cells, respectively. Multidrug and toxin extrusion protein 1 (MATE1) is a major component of subsequent export into bile and urine. However, the functional interaction of OCTs and MATE1 for uptake and transcellular transport of the oral antidiabetic drug metformin or of the cation 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) has not fully been characterized.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Single-transfected Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells as well as double-transfected MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 and -OCT2-MATE1 cells were used to study metformin and MPP+ uptake into and transcellular transport across cell monolayers, along with their concentration and pH dependence.

KEY RESULTS

Cellular accumulation of MPP+ and metformin was significantly reduced by 31% and 46% in MDCK-MATE1 single-transfected cells compared with MDCK control cells (10 µM; P < 0.01). Over a wide concentration range (10–2500 µM) metformin transcellular transport from the basal into the apical compartment was significantly higher in the double-transfected cells compared with the MDCK control and MDCK-MATE1 monolayers. This process was not saturated up to metformin concentrations of 2500 µM. In MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells basal to apical MPP+ and metformin transcellular translocation decreased with increasing pH from 6.0 to 7.5.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Our data demonstrate functional interplay between OCT1/OCT2-mediated uptake and efflux by MATE1. Moreover, MATE1 function in human kidney might be modified by changes in luminal pH values.

Keywords: drug transport, organic cation transporters, OCT1, OCT2, MATE1, double-transfected cells, MDCK, metformin

Introduction

Transporters are important determinants of absorption, distribution and elimination of endogenous compounds and drugs, as they are expressed in small intestine, liver and kidney (Fromm, 2003; Ho and Kim, 2005; Kitamura et al., 2008). In liver, transporters located in the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes, such as organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs) or organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1), mediate drug uptake from the portal venous blood into the hepatocyte. Efflux transporters such as multidrug-resistance protein 2 (MRP2) or multidrug and toxin extrusion protein 1 (MATE1), located in the canalicular membrane of hepatocytes mediate the subsequent translocation of the parent compound or its metabolite(s) into the bile (Nies et al., 2008b; Kindla et al., 2009). In kidney, uptake transporters expressed in basal membrane of proximal tubular cells determine, in combination with apically expressed efflux transporters, the renal secretion of organic anions or cations (Terada and Inui, 2008). Modifications of uptake or efflux transporter function by co-medication or by genetic variations can affect drug disposition and drug effects.

Disposition of cationic drugs is determined by uptake via OCT1 (gene name SLC22A1) and OCT2 (gene name SLC22A2), which are expressed in the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes and renal proximal tubular cells, respectively (Koepsell et al., 2007; Nies et al., 2009; Zolk, 2009; Zolk et al., 2009; Meyer zu Schwabedissen et al., 2010). Substrates for OCT1 and OCT2 are several organic cations, for example, tetraethylammonium (TEA) and 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), as well as cationic drugs like the oral antidiabetic drug metformin. More recently, the multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE) proteins have been identified and characterized, which function as H+/organic cation antiporters mediating the excretion of their substrates into bile and urine (Otsuka et al., 2005; Masuda et al., 2006; Omote et al., 2006; Tanihara et al., 2007; Terada and Inui, 2008). Whereas MATE2-K (gene name SLC47A2) is predominantly expressed in kidney, MATE1 (gene name SLC47A1) is expressed both in liver and kidney and is located in the canalicular membrane of hepatocytes and the apical membrane of proximal tubular cells, respectively. The relevance of MATE1/Mate1 for drug disposition was recently highlighted using Mate1 knock-out mice, which exhibited about 15-fold accumulation of the oral antidiabetic drug metformin in the liver and a renal secretory clearance of only 14% compared with wild-type animals (Tsuda et al., 2009a). Thus, coordinated transcellular translocation by uptake via OCT1/OCT2 in combination with efflux via MATE1 is believed to be an essential system for biliary and renal elimination of cationic drugs (Terada and Inui, 2008).

In the view of a considerably growing interest in in vitro models to characterize the role of drug transporters for drug disposition (Huang et al., 2010), several double- (Cui et al., 2001; Letschert et al., 2005; Matsushima et al., 2005; Nies et al., 2008a), triple- (Hirouchi et al., 2009) and quadruple-transfected cell lines (Kopplow et al., 2005) have been generated, which express one or several uptake (e.g. OATPs) and efflux transporters (e.g. MRP2). These cell lines are very useful for the understanding of the coordinate action of uptake and efflux transporters. Sato et al. (2008) recently generated double-transfected OCT1/MATE1 and OCT2/MATE1 cells and characterized in particular the role of these transporters for uptake and transcellular translocation of the organic cation TEA (tetraethylammonium). Other organic cations showed also a considerably higher transcellular translocation from the basal to the apical compartment of the cell monolayers compared with the translocation in the opposite direction.

Here, we have extended this early work, focusing on determinants of uptake and transcellular translocation of one of the model substrates of organic cation transporters, MPP+, and the frequently used oral antidiabetic drug metformin, which has also been shown to be transported by both OCTs and MATEs. By using MDCK-control, MDCK-OCT1, MDCK-OCT2 and MDCK-MATE1 single-transfected cells as well as MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 and MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 double-transfected cells, we studied (i) the uptake and transcellular translocation of MPP+ and metformin in these six single- or double-transfected cell lines, (ii) the concentration-dependence of organic cation transport across cell monolayers as well as (iii) the dependence of transcellular translocation on pH on the apical side of the monolayers.

Methods

Cloning of the SLC47A1 cDNA encoding human MATE1

The cDNA encoding human MATE1 (SLC47A1) was cloned using an RT-PCR-based approach. A primer pair covering the entire coding cDNA sequence was designed (oMATE1-5′.for = 5′-GAGTCACATGGAAGCTCCTG-3′ and oMATE1-RT.rev = 5′-ACGTCACTGAATTCTGACAT-3′) and used for amplifying the SLC47A1 cDNA with human liver mRNA as template for the RT-PCR. The amplified cDNA fragment was cloned into the vector pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) and sequenced. Base pair substitutions leading to amino acid exchanges after translation have been corrected using the multisite-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After mutagenesis, the cDNA encoded for a MATE1 protein 100% identical to the protein encoded by the reference sequence (NM_018242.2). This cDNA was subcloned into the vector pcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen), resulting in the vector pMATE1.31 and used for transfection.

Generation of stably transfected cells and quantitative RT-PCR

Generation and validation of MDCK-OCT1 and MDCK-OCT2 single-transfected cells have been described before (Bachmakov et al., 2008; 2009;). Both MDCK cell lines were used for the generation of the double-transfected MDCK cells expressing, in addition, the export protein MATE1. Therefore, the single-transfected MDCK cells were further transfected with the vector pMATE1.31 using lipofectamin (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After selection with 500 µM geniticin for 4 weeks, the transfectants and the respective single-transfected MDCK cells were screened for SLC22A1 mRNA (encoding OCT1), SLC22A2 mRNA (encoding OCT2) and SLC47A1 mRNA (encoding MATE1) expression using RT-PCR and LightCycler-based quantitative RT-PCR. First strand cDNA synthesis was carried out as described above using total RNA from selected cell clones (for selection of cell clones with the highest SLC47A1 mRNA expression) or from all cell lines used in the study (for comparative expression analysis: MDCK-Co/MDCK-OCT1/MDCK-OCT2/MDCK-MATE1/MDCK-OCT1-MATE1/MDCK-OCT2-MATE1). For the quantitative PCR analysis, the following primer pairs were used: OCT1: oOCT1-RT.for (5′-GGT GAA TGC TGA GC-3′) and oOCT1-RT.rev (5′-ACA TCT CTC TCA GGT GCC CG-3′); OCT2: oOCT2-RT.for (5′-CAA TGG CCT ATG AGA TAG TCT-3′) and oOCT2-RT.rev (5′-GCA GCA ACG GTC TCT CTT CTT-3′); MATE1: oMATE1-RT.for (5′-AAG CCT GTC AGC AGG CTC AG-3′) and oMATE1-RT.rev (5′-ACG TCA CTG AAT TCT GAC AT-3′). In addition, commercially available sscDNAs (multiple cDNA panel from Clontech Laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany) were used in the quantitative RT-PCR. Expression of all mRNAs was calculated in relation to the expression of β-actin mRNA, amplified with the primer pair actin.for (5′-TGA CGG GGT CAC CCA CAC TGT GCC CAT CTA-3′) and actin.rev (5′-CTA GAA GCA TTT GCG GTG GAC GAT GGA GGG-3′). The cell clones with the highest SLC47A1 mRNA expression and with a SLC22A1/SLC22A2 mRNA expression comparable to the expression in the single-transfected MDCK cells (designated as MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 and MDCK-OCT2-MATE1) were used for uptake and vectorial transport experiments.

Immunofluorescence

A rabbit polyclonal antibody against hMATE1 was kindly provided by Prof Yoshinori Moriyama [Department of Membrane Biochemistry, Graduate School for Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Okayama University, Okayama, Japan; (Otsuka et al., 2005)]. Cellular localization of MATE1 was analysed by immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy with a Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal system using a Zeiss Axiovert microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Cells grown on microscope slides coated with poly-D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) were fixed in 4% formalin in PBS, blocked in 5% goat serum and incubated with the MATE1 antibody (1:500 in 5% bovine serum albumin in PBS) over night. Slides were then incubated with an Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary antibody for 30 min (1:2000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and nuclei were counterstained with Cytox Orange nucleic acid stain (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Transport studies with single- and double-transfected cells

The cellular accumulation and transcellular transport of radiolabelled MPP+ or metformin by MDCK cells were measured in monolayer cultures grown in cell culture inserts on porous membranes (ThinCert, 0.4 µm pore size, Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany). For all experiments, 0.5 × 106 cells per well were used. Cells were grown to confluence for 3 days, induced with 10 mM Na-butyrate for 24 h and subsequently used for transport experiments. The incubation medium for the transport experiments contained 142 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM K2HPO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM glucose, and 12.5 mM HEPES (pH 6.0–7.5). In general, after the culture medium was removed from both sides of the monolayers, cells were equilibrated in incubation medium for 10 min at 37°C. After preincubation, experiments were started by replacing the medium in either the apical or basolateral compartment with medium containing radiolabelled compounds. The pH of the medium on the basolateral side was 7.4. The pH on the apical side was also 7.4 unless indicated otherwise. Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2, and 50 µl aliquots were taken at the time points indicated. To measure the cellular accumulation of the labelled test compounds, the medium was immediately removed at the end of the incubation period and the cell monolayers were rapidly rinsed three times with ice-cold incubation medium (pH 7.4). The incubation period lasted 60 min. In order to test, in addition, the effect of varying pH values after a longer exposure, the incubation time was extended for this set of experiments to 3 h. Filters were detached from the chambers, and cells were lysed with 5 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.2% SDS. The radioactivity of the collected medium and the solubilised cell monolayers was determined by liquid scintillation counting (PerkinElmer, Rodgau-Jügesheim, Germany), and protein concentrations of the cell lysates were measured with a bicinchonic acid assay (BCA Protein Assay Kit; Peribo Science, Bonn, Germany). Tightness of the cell monolayer was routinely assessed using [3H]inulin, which was added to the donor compartment. Basal-to-apical translocation of inulin was not different between pH 6.0 and 7.5 in both vector control cells and the MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells for a time interval of up to 3 h.

Data analysis

Each concentration and time point was investigated in three to nine separate wells. All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Multiple comparisons were analysed by ANOVA with subsequent Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test by using Prism 3.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). A value of P < 0.05 was required for statistical significance.

Materials

Unlabelled 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) was obtained from BIOTREND (Germany). Metformin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). [14C]Metformin (0.03 Ci·mmol−1) and [3H]MPP+ (80 Ci·mmol−1) were purchased from American Radiolabelled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO) and [3H]inulin (2.25 Ci·mmol−1) was from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA). G418 (geniticin) disulfate and hygromycin were from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany). The drug and molecular target nomenclature used here follows (Alexander et al., 2009).

Results

Expression analysis of OCTs and MATE1 in single- and double-transfected cell lines

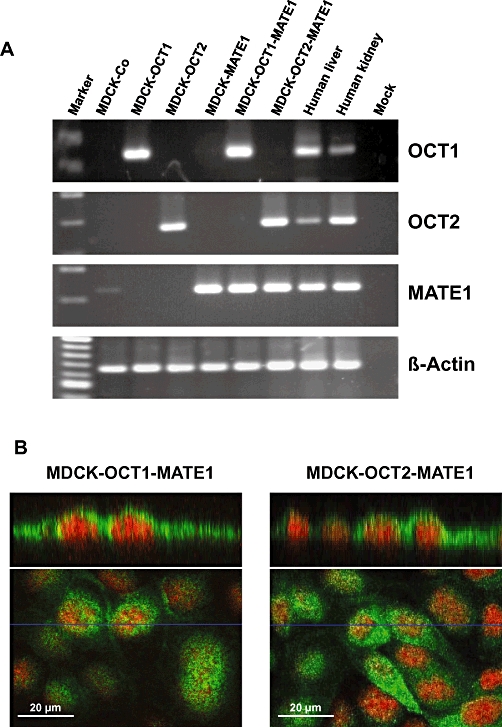

The SLC47A1 mRNA (encoding MATE1) expression in stably double-transfected MDCK cells was analysed using RT-PCR and LightCycler-based quantitative RT-PCR. In addition, using the same approach, the expression of SLC22A1 mRNA (encoding OCT1) and SLC22A2 mRNA (encoding OCT2) was analysed and compared with the expression in the single-transfected MDCK cells and with the expression in human liver and human kidney [sscDNAs for this analysis were derived from the multiple tissue cDNA panel (Clontech Laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany)]. Primer pairs for these PCR analyses were tested to be specific for the respective human cDNA not amplifying canine Slc22a1, Slc22a2 or Slc47a1 cDNA. These expression analyses demonstrated (Figure 1A) that the specific mRNA is expressed only in the respective single- or double-transfected cell line and that no amplification product was detected in control cells (MDCK-Co).

Figure 1.

A. RT-PCR analysis of SLC22A1 (encoding OCT1), SLC22A2 (encoding OCT2) and SLC47A1 (encoding MATE1) mRNA expression in control cells (MDCK-Co), single- (MDCK-OCT1, MDCK-OCT2, MDCK-MATE1) and double-transfected (MDCK-OCT1-MATE1, MDCK-OCT2-MATE1) cell lines, used in this study, and in human liver and kidney. B. Immunofluorescence of hMATE1 in MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 and MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells. hMATE1 is localized to the apical membrane of both double-transfected cell lines. No positive staining was observed in MDCK control cells (MDCK-Co; data not shown).

Furthermore, the amount of SLC22A1, SLC22A2 and SLC47A1 mRNA in the double-transfected cell lines, which was calculated in relation to the expression of the housekeeping gene β-actin, was in a range similar to that in the respective single-transfected cell line (SLC22A1 MDCK-OCT1 vs. MDCK-OCT1-MATE1: 125 vs. 113% β-actin; SLC22A2 MDCK-OCT2 vs. MDCK-OCT2-MATE1: 181 vs. 197%; SLC47A1 MDCK-MATE1 vs. MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 vs. MDCK-OCT2-MATE1: 87 vs. 149 vs. 213%). Moreover, hMATE1 was localized by immunofluorescence to the apical membrane of the transfected cell lines, but was not detectable in the MDCK control cells (Figure 1B). These results demonstrate that all cell lines expressed the respective transporter and that they could be used for uptake and vectorial transport experiments.

Uptake and transcellular transport of MPP+ and metformin

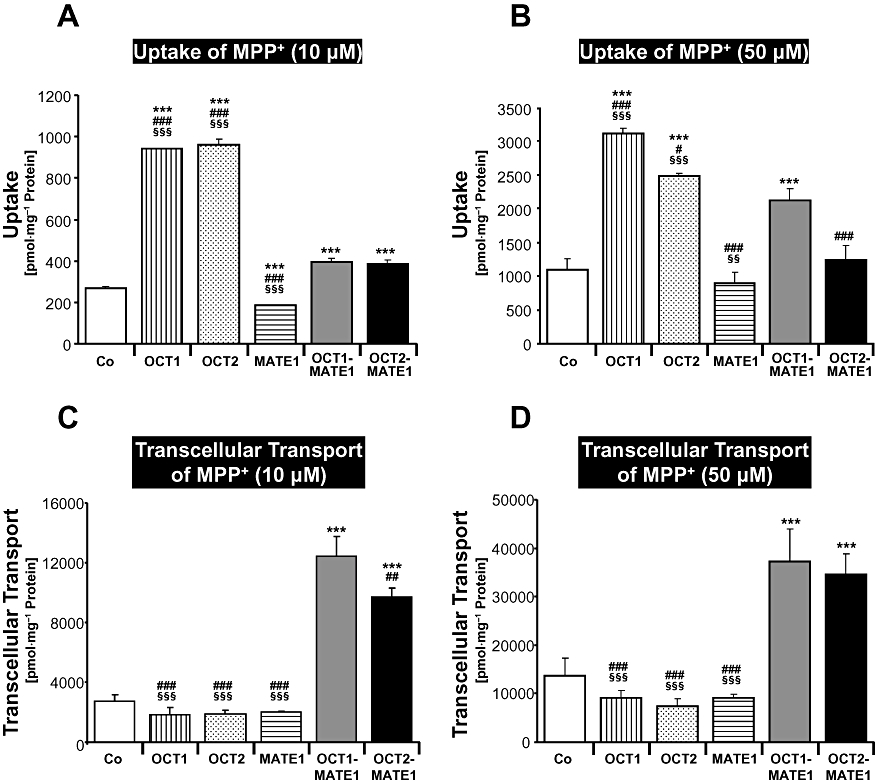

MPP+ uptake into MDCK-OCT1 and MDCK-OCT2 cells was significantly higher compared with the uptake into MDCK control cells (P < 0.001; Figure 2A and B). In contrast, MDCK-MATE1 cells showed a reduction in MPP+ cellular accumulation by 31% (MPP+ substrate concentration 10 µM; P < 0.001) and 19% (50 µM; n.s.) compared with MDCK control cells (Figure 2A and B). Compared with double-transfected MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 or MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells, cellular accumulation was higher in MDCK-OCT1 and MDCK-OCT2 cells, but lower in MDCK-MATE1 cells (P < 0.05; Figure 2A and B). Transcellular transport of MPP+ from the basal into the apical compartment was considerably higher in double-transfected MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 or MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells compared with MDCK control cells and the single-transfected cells (P < 0.01; Figure 2C and D).

Figure 2.

MPP+ (10 and 50 µM) was administered to the basal side of monolayers of MDCK-control (Co), MDCK-OCT1 (OCT1), MDCK-OCT2 (OCT2), MDCK-MATE1 (MATE1), MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 (OCT1-MATE1) and MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 (OCT2-MATE2) cells. Uptake of MPP+ into the cells (A, B) and transcellular transport of MPP+ from the basal to the apical compartment after 60 min (C, D) are shown. Data are shown as mean value ± standard deviation. ***P < 0.001 versus MDCK-control; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 versus MDCK-OCT1-MATE1; §§P < 0.01, §§§P < 0.001 versus MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells.

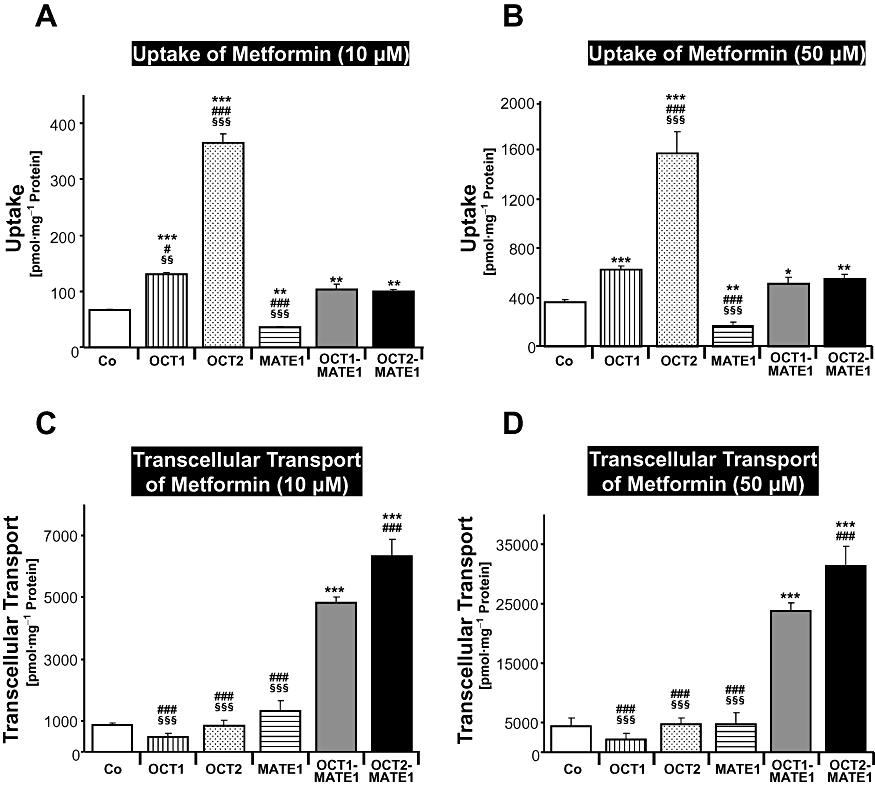

Figure 3 demonstrates that qualitatively similar results were obtained for uptake and transcellular transport of metformin. Cellular accumulation of metformin was significantly reduced by 46% (10 µM) and 53% (50 µM) in MDCK-MATE1 cells compared with MDCK control cells (P < 0.01; Figure 3A and B). Most importantly, metformin transcellular transport from the basal into the apical compartment was considerably higher in double-transfected MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 or MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells compared with MDCK control cells and the single-transfected cells (P < 0.001; Figure 3C and D). Transcellular translocation of metformin was higher in MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells compared with MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 cells (P < 0.001; Figure 3C and D), which was compatible with the considerably higher metformin uptake into MDCK-OCT2 compared with the MDCK-OCT1 cells (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Metformin (10 and 50 µM) was administered to the basal side of monolayers of MDCK-control (Co), MDCK-OCT1 (OCT1), MDCK-OCT2 (OCT2), MDCK-MATE1 (MATE1), MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 (OCT1-MATE1) and MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 (OCT2-MATE1) cells. Uptake of metformin into the cells (A, B) and translocation of metformin from the basal to the apical compartment after 60 min (C, D) are shown. Data are shown as mean value ± standard deviation. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus MDCK-control; ###P < 0.001 versus MDCK-OCT1-MATE1; §§P < 0.01, §§§P < 0.001 versus MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells.

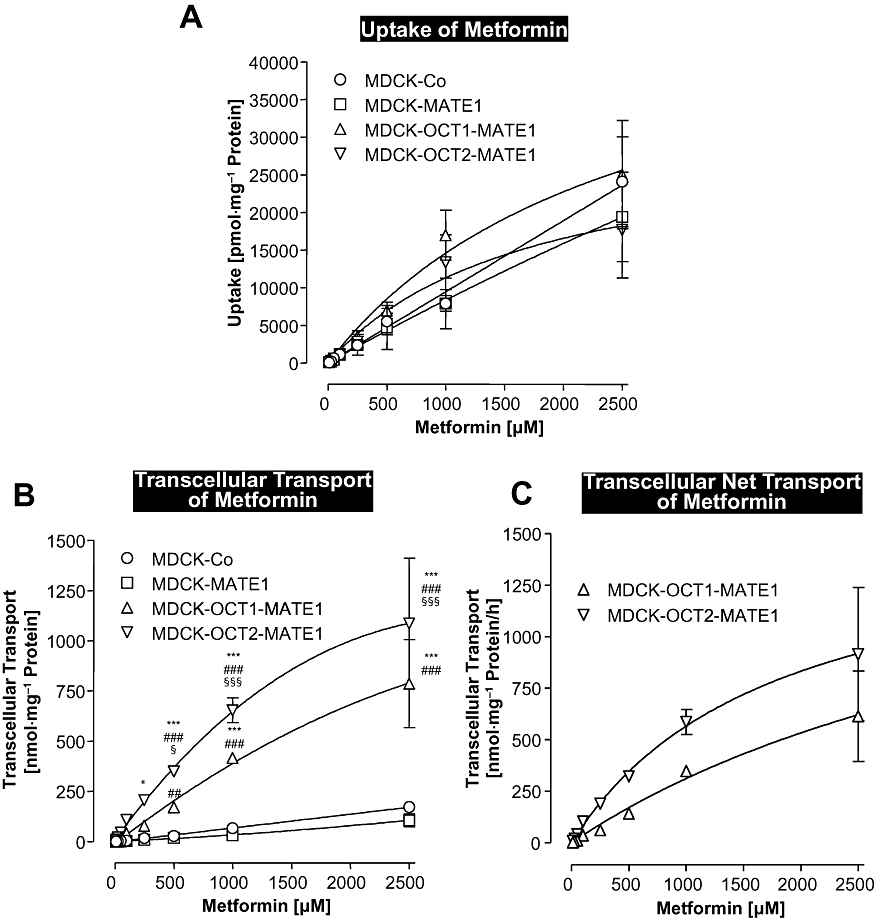

Concentration dependent uptake and transcellular transport of metformin

Next, we investigated, over a wide concentration range (10–2500 µM), the concentration dependence of metformin uptake and transcellular transport in MDCK-control, MDCK-MATE1, MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 and MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells. Cellular accumulation of metformin was similar in all four cell lines over the whole concentration range (Figure 4A). No saturation of metformin uptake was observed up to a substrate concentration of 2500 µM (Figure 4A). Total metformin transcellular transport and metformin net transcellular transport from the basal into the apical compartment were significantly higher in the double-transfected cells compared with the MDCK-control and MDCK-MATE1 monolayers (Figure 4B). This process was also not saturated up to metformin concentrations of 2500 µM (Figure 4B and C).

Figure 4.

Concentration-dependent uptake (A) and transcellular transport (B) of metformin in monolayers of MDCK-control (MDCK-Co), MDCK-MATE1, MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 and MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells. (C) Net metformin transcellular transport calculated from the differences in basal to apical transport in the double-transfected cells minus the corresponding transport in the vector control cells. Metformin (10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000, 2500 µM) was administered to the basal side of the monolayers and uptake and transcellular transport into the apical compartment were determined after 60 min. Data are shown as mean value ± standard deviation. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 versus MDCK-control; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus MDCK-MATE1; §P < 0.05, §§§P < 0.001 versus MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 cells.

pH dependence of MPP+ and metformin transcellular transport

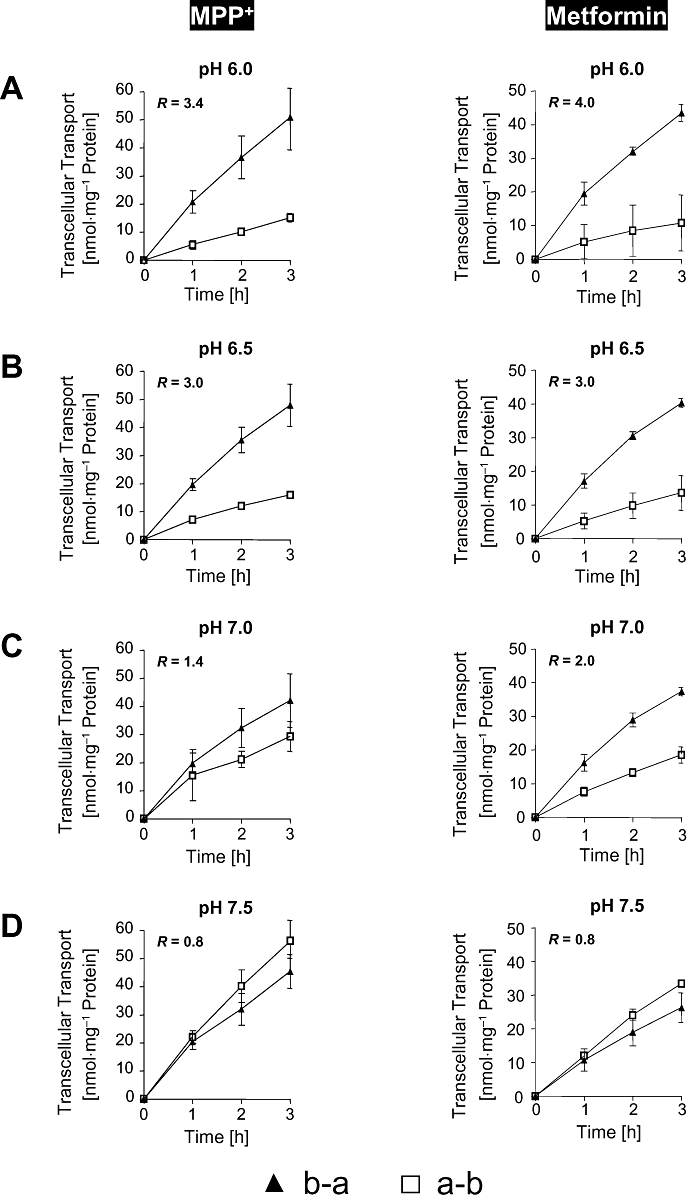

pH dependence (pH 6.0, 6.5, 7.0 and 7.5 in the apical compartment) of MPP+ and metformin transcellular transport from the basal to the apical (b-a) and from the apical to the basal (a-b) compartment was investigated in our model system, after administration of the substrates to either the basal or the apical compartment of the cell monolayers. In these experiments, we used monolayers of MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells. For both compounds, basal to apical translocation decreased and apical to basal translocation increased, with a stepwise increase of the pH values in the apical compartment (Figure 5). In contrast, there was no pH-dependent change both in basal to apical as well as apical to basal transcellular translocation of MPP+ and metformin in monolayers of MDCK control cells (data not shown). In MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cell monolayers, the transport ratios (R), which were calculated as the quotient of apically directed transport and basally directed transport measured at 3 h, was 3.4 for MPP+ and 4.0 for metformin at pH 6.0 in the apical compartment. At pH 7.5 in the apical compartment, these ratios decreased to 0.8 for both compounds (Figure 5). Finally, using metformin, we determined the ratio of basal to apical (b-a) and apical to basal (a-b) transcellular transport (b-a/a-b) in monolayers of MDCK-control, MDCK-OCT1, MDCK-OCT2, MDCK-MATE1, MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 and MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells after 30 or 60 min with a pH of 6.5 in the apical compartment. The highest values were observed for the MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 and the MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells compared to the other four cell lines (Table 1).

Figure 5.

pH dependence of MPP+ (50 µM) and metformin (50 µM) basal to apical (b-a) and apical to basal (a-b) transcellular transport in monolayers of MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells after administration of MPP+ or metformin to either the basal or the apical side of the cell monolayers. pH in the apical compartment was 6.0 (A), 6.5 (B), 7.0 (C) and 7.5 (D). pH in the basal compartment was 7.4 in all experiments. There was no pH dependent change both in basal to apical (b-a) as well as apical to basal (a-b) transcellular translocation of MPP+ and metformin in monolayers of MDCK control cells (data not shown). The transport ratio (R) was calculated as the quotient of the mean of the apically directed transport and the mean of the basally directed transport at 3 h. Data are shown as mean value ± standard deviation.

Table 1.

Ratio of basal to apical and apical to basal metformin transcellular transport (50 µM) in monolayers of MDCK-control, MDCK-OCT1, MDCK-OCT2, MDCK-MATE1, MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 and MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cells after 30 or 60 min

| 30 min | 60 min | |

|---|---|---|

| MDCK-control | 1.00 | 0.61 |

| MDCK-OCT1 | 2.20 | 0.74 |

| MDCK-OCT2 | 0.60 | 0.78 |

| MDCK-MATE1 | 1.74 | 2.06 |

| MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 | 12.40 | 10.41 |

| MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 | 6.20 | 6.75 |

The pH in the apical compartment was 6.5 in these experiments.

Discussion and conclusions

Using newly established double-transfected MDCK cells recombinantly expressing the uptake transporters OCT1 or OCT2 together with the export protein MATE1, we have investigated in this study some determinants of the vectorial transport of organic cations. The new, major findings of this work on uptake and transcellular transport in polarized cell monolayers are (i) the functional interaction between the OCT uptake transporters and the MATE efflux transporters as shown with five MDCK cell lines expressing one or two uptake and/or efflux transporters of organic cations, (ii) the lack of saturation of transcellular organic cation transport (metformin) over a broad concentration range and (iii) a clear dependence of transcellular MPP+ and metformin transport on apical pH values.

Cellular accumulation of the organic cations MPP+ and metformin was lowest in cells expressing only the efflux transporter MATE1, significantly higher in MDCK control cells without stable expression of transporters for organic cations and in MDCK-OCT1-MATE1 or MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 double-transfected cells and highest in single-transfectants expressing only the uptake transporters OCT1 or OCT2. This is in line with studies using Oct1 and Mate1 knock-out mice, which showed a 30-fold reduction and a 15-fold increase, respectively, in liver concentrations after intravenous administration of metformin (Wang et al., 2002; Tsuda et al., 2009a) and with a recent clinical study showing an interaction between polymorphisms in the OCT1 and MATE1 transporters and the glucose lowering effect of metformin (Becker et al., 2010). Thus, in vitro and in vivo evidence clearly indicate the dependency of intracellular drug concentrations and effects of organic cations, such as metformin, on both uptake and efflux processes. An individual's drug response (e.g. to metformin) is very likely to depend on the relative abundance of both OCT1/OCT2 and MATE1 as well as the combination of polymorphisms/haplotypes determining OCT1/OCT2 and MATE1 function. Data from other groups (Yokoo et al., 2007; Sato et al., 2008; Matsushima et al., 2009; Tsuda et al., 2009a,b; Meyer zu Schwabedissen et al., 2010) as well as our data with the OCT2-MATE1 double-transfectants indicate that the same principles are very likely to be relevant also for renal secretion of organic cations and nephrotoxicity.

Concentrations of organic cationic drugs, such as metformin, in the systemic circulation and, in particular in portal venous blood, vary considerably. For metformin, which has a negligible protein binding in blood, plasma concentrations in the systemic circulation can be as high as 24 µM. The estimated metformin concentrations in portal venous blood are 15-fold higher [357 µM (Bachmakov et al., 2008)]. We therefore studied the concentration dependency of metformin transcellular transport, using our newly established model systems for hepatic (MDCK-OCT1-MATE1) and renal (MDCK-OCT2-MATE1) transport of organic cations. A wide concentration range (10–2500 µM) was used on the basal side of the MDCK cell monolayers. Interestingly, no saturation of metformin uptake and transcellular translocation from the basal to the apical compartment was observed in spite of the concentration range studied (Figure 4B). Our findings are in line with relatively high Km values for OCT1- and OCT2-mediated metformin uptake of 1500 to 2000 and 1000 to 1400 µM, respectively. The affinity constant (Km value) of metformin to MATE1, which was determined in the uptake mode after intracellular acidification with ammonium chloride, has been reported to be 780 µM (Tanihara et al., 2007). Our findings should be of particular relevance for the uptake of metformin and possibly other cationic drugs from the portal venous blood via the basolateral membrane into hepatocytes, as pronounced differences in drug concentrations can be expected. We believe that these data indicate the OCT1/MATE1 transporter couple, expressed in human liver, represents a high capacity system for translocation of organic cations.

In vitro studies clearly demonstrated that an oppositely directed proton gradient functions as a driving force of the H+/organic cation antiporter MATE1 (Tsuda et al., 2007). It has been discussed whether and to what extent there is a proton gradient in the proximal and distal convoluted tubules of the kidney, where MATE1 is expressed. The driving force is even more unclear for the liver, where the Na+/H+ exchanger is not functional (Sato et al., 2008). However, data from the Mate1 knock-out mice clearly indicate that both hepatic and renal Mate1 are functionally active and are essential for metformin elimination into the bile and urine, respectively (Tsuda et al., 2009a). In our experiments, we modified the pH in the apical compartment of the MDCK-OCT2-MATE1 cell monolayers and found, in line with previous reports using TEA as substrate (Sato et al., 2008), a strongly polarized metformin transcellular translocation from the basal into the apical compartment, in comparison to the opposite direction, at lower pH values (pH 6.0 to 7.0) compared with pH 7.5. In our opinion, it will be crucial to determine next the clinical relevance of pH changes in the lumen of the tubules for renal secretion of organic cations.

Taken together, we believe that the use of stably transfected cell lines expressing combinations of uptake and efflux transporters are valuable tools for an improved understanding of determinants of tissue concentrations and modes of elimination of endogenous compounds and drugs. In particular, our data indicate that the OCT1/MATE1 system of organic cation transport in the liver and the OCT2/MATE1 system of the kidneys are high capacity systems with little evidence for saturation (see metformin). Further in vivo studies need to address the clinical relevance of the pH changes on the luminal side of renal epithelial cells for excretion of cationic drugs, including a better understanding of its modification by disease, toxins and drugs.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Hoier for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Fr 1298/5-1) and the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (P28/09 // A46/09).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Km

Michaelis-Menten constant

- MATE

multidrug and toxin extrusion protein

- MDCK cells

Madin-Darby canine kidney cells

- MPP+

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium

- MRP2

multidrug resistance protein 2

- OATP

organic anion transporting polypeptide

- OCT

organic cation transporter

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- TEA

tetraethylammonium

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

Teaching Materials; Figs 1–5 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmakov I, Glaeser H, Fromm MF, König J. Interaction of oral antidiabetic drugs with hepatic uptake transporters: focus on organic anion transporting polypeptides and organic cation transporter 1. Diabetes. 2008;57:1463–1469. doi: 10.2337/db07-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmakov I, Glaeser H, Endress B, Mörl F, König J, Fromm MF. Interaction of beta-blockers with the renal uptake transporter OCT2. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11:1080–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker ML, Visser LE, van Schaik RH, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Stricker BH. Interaction between polymorphisms in the OCT1 and MATE1 transporter and metformin response. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20:38–44. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328333bb11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, König J, Keppler D. Vectorial transport by double-transfected cells expressing the human uptake transporter SLC21A8 and the apical export pump ABCC2. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:934–943. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromm MF. Importance of P-glycoprotein for drug disposition in humans. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33(Suppl 2):6–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.33.s2.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirouchi M, Kusuhara H, Onuki R, Ogilvie BW, Parkinson A, Sugiyama Y. Construction of triple-transfected cells [organic anion-transporting polypeptide (OATP) 1B1/multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) 2/MRP3 and OATP1B1/MRP2/MRP4] for analysis of the sinusoidal function of MRP3 and MRP4. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:2103–2111. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho RH, Kim RB. Transporters and drug therapy: implications for drug disposition and disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:260–277. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S-M, Zhang L, Giacomini KM. The International Transporter Consortium: a collaborative group of scientists from academia, industry, and the FDA. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:32–36. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindla J, Fromm MF, König J. In vitro evidence for the role of OATP and OCT uptake transporters in drug-drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:489–500. doi: 10.1517/17425250902911463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S, Maeda K, Sugiyama Y. Recent progresses in the experimental methods and evaluation strategies of transporter functions for the prediction of the pharmacokinetics in humans. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008;377:617–628. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell H, Lips K, Volk C. Polyspecific organic cation transporters: structure, function, physiological roles, and biopharmaceutical implications. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1227–1251. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9254-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopplow K, Letschert K, König J, Walter B, Keppler D. Human hepatobiliary transport of organic anions analyzed by quadruple-transfected cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1031–1038. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.014605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letschert K, Komatsu M, Hummel-Eisenbeiss J, Keppler D. Vectorial transport of the peptide CCK-8 by double-transfected MDCKII cells stably expressing the organic anion transporter OATP1B3 (OATP8) and the export pump ABCC2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:549–556. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.081224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda S, Terada T, Yonezawa A, Tanihara Y, Kishimoto K, Katsura T, et al. Identification and functional characterization of a new human kidney-specific H+/organic cation antiporter, kidney-specific multidrug and toxin extrusion 2. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2127–2135. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima S, Maeda K, Kondo C, Hirano M, Sasaki M, Suzuki H, et al. Identification of the hepatic efflux transporters of organic anions using double-transfected Madin-Darby canine kidney II cells expressing human organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1)/multidrug resistance-associated protein 2, OATP1B1/multidrug resistance 1, and OATP1B1/breast cancer resistance protein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1059–1067. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima S, Maeda K, Inoue K, Ohta KY, Yuasa H, Kondo T, et al. The inhibition of human multidrug and toxin extrusion 1 is involved in the drug-drug interaction caused by cimetidine. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:555–559. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE, Verstuyft C, Kroemer HK, Becquemont L, Kim RB. Human multidrug and toxin extrusion 1 (MATE1/SLC47A1) transporter: functional characterization, interaction with OCT2, and single nucleotide polymorphisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F997–F1005. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00431.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nies AT, Herrmann E, Brom M, Keppler D. Vectorial transport of the plant alkaloid berberine by double-transfected cells expressing the human organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1, SLC22A1) and the efflux pump MDR1 P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008a;376:449–461. doi: 10.1007/s00210-007-0219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nies AT, Schwab M, Keppler D. Interplay of conjugating enzymes with OATP uptake transporters and ABCC/MRP efflux pumps in the elimination of drugs. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008b;4:545–568. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.5.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nies AT, Koepsell H, Winter S, Burk O, Klein K, Kerb R, et al. Expression of organic cation transporters OCT1 (SLC22A1) and OCT3 (SLC22A3) is affected by genetic factors and cholestasis in human liver. Hepatology. 2009;50:1227–1240. doi: 10.1002/hep.23103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omote H, Hiasa M, Matsumoto T, Otsuka M, Moriyama Y. The MATE proteins as fundamental transporters of metabolic and xenobiotic organic cations. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka M, Matsumoto T, Morimoto R, Arioka S, Omote H, Moriyama Y. A human transporter protein that mediates the final excretion step for toxic organic cations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17923–17928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506483102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Masuda S, Yonezawa A, Tanihara Y, Katsura T, Inui K. Transcellular transport of organic cations in double-transfected MDCK cells expressing human organic cation transporters hOCT1/hMATE1 and hOCT2/hMATE1. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76:894–903. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanihara Y, Masuda S, Sato T, Katsura T, Ogawa O, Inui K. Substrate specificity of MATE1 and MATE2-K, human multidrug and toxin extrusions/H(+)-organic cation antiporters. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada T, Inui K. Physiological and pharmacokinetic roles of H+/organic cation antiporters (MATE/SLC47A) Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:1689–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Terada T, Asaka J, Ueba M, Katsura T, Inui K. Oppositely directed H+ gradient functions as a driving force of rat H+/organic cation antiporter MATE1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F593–F598. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00312.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Terada T, Mizuno T, Katsura T, Shimakura J, Inui K. Targeted disruption of the multidrug and toxin extrusion 1 (Mate1) gene in mice reduces renal secretion of metformin. Mol Pharmacol. 2009a;75:1280–1286. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.056242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Terada T, Ueba M, Sato T, Masuda S, Katsura T, et al. Involvement of human multidrug and toxin extrusion 1 in the drug interaction between cimetidine and metformin in renal epithelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009b;329:185–191. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DS, Jonker JW, Kato Y, Kusuhara H, Schinkel AH, Sugiyama Y. Involvement of organic cation transporter 1 in hepatic and intestinal distribution of metformin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:510–515. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.034140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoo S, Yonezawa A, Masuda S, Fukatsu A, Katsura T, Inui K. Differential contribution of organic cation transporters, OCT2 and MATE1, in platinum agent-induced nephrotoxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolk O. Current understanding of the pharmacogenomics of metformin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86:595–598. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolk O, Solbach TF, König J, Fromm MF. Functional characterization of the human organic cation transporter 2 variant p.270Ala>Ser. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1312–1318. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.