Abstract

The present investigation examined the explanatory (i.e. mediating) role of distress tolerance (DT) in the relation between posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives. The sample consisted of 142 adults (46.5% women; Mage = 22.18, SD = 7.22, range = 18–55), who endorsed exposure to at least one Criterion A traumatic life event (DSM-IV-TR, 2000) and reported marijuana use within the past 30 days. As predicted, results demonstrated that DT partially mediated the relation between PTS symptom severity and coping-oriented marijuana use. These preliminary results suggest that DT may be an important cognitive-affective mechanism underlying the PTS-marijuana use coping motives association. Theoretically, trauma-exposed marijuana users with greater PTS symptom severity may use marijuana to cope with negative mood states, at least partially because of a lower perceived capacity to withstand emotional distress.

Keywords: trauma, posttraumatic stress, distress tolerance, marijuana, coping

Significant associations between posttraumatic stress (PTS; diagnostic sub-threshold symptoms) as well as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and marijuana use are well-documented (Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Lipschitz et al., 2003; Rohrbach, Grana, Vernberg, Sussman, & Sun, 2009; Vlahov et al., 2002). Here, trauma exposure and PTS symptom severity have been associated with increased levels of marijuana use, both cross-sectionally and prospectively (Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, & Drescher, in press; Bremner, Southwick, Darnell, & Charney, 1996; Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Lipschitz et al., 2003; Rohrbach et al., 2009; Vlahov et al., 2002).

The examination of motivations for marijuana use is one promising method for better understanding the mechanisms underlying the association between PTS symptom severity and marijuana use. Although associations between trauma exposure and coping-oriented alcohol use (Dixon, Leen-Feldner, Ham, Feldner, & Lewis, 2009; Stewart, Conrod, Samoluk, Pihl, & Dongier, 2000; Stewart, Mitchell, Wright, & Loba, 2004; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2006) and nicotine use (Beckham et al., 1995, 1997; Feldner, Babson, & Zvolensky 2007; Feldner et al., 2007) have been well documented, only three studies have examined the association between PTS or PTSD and marijuana use motives (Bremner et al., 1996; Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, Feldner, Bernstein, & Zvolensky, 2007; Bonn-Miller, Babson, Vujanovic, & Feldner, 2010). First, Bremner and colleagues (1996) conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional investigation among Vietnam veterans with PTSD, documenting that these veterans reported: (a) associations between marijuana use and alleviation of PTSD symptoms, and (b) marijuana use to cope specifically with PTSD-related symptoms of hyperarousal. More recently, among a non-clinical community sample of trauma-exposed marijuana users examined cross-sectionally, higher levels of PTS symptom severity were significantly related to increased coping-oriented marijuana use motives (e.g., “to forget my worries,” “to cheer me up when I am in a bad mood;” Bonn-Miller et al., 2007). Finally, in a sample of marijuana users with PTSD (n = 20), although no main effect between PTSD symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives was observed, PTSD symptom severity significantly interacted with sleep problems to predict coping-oriented marijuana use (Bonn-Miller et al., 2010). Results from these three studies suggest that trauma-exposed individuals seem especially likely to use marijuana for coping reasons, specifically, as compared to other motives for use. Yet, the mediating –or explanatory –factors underlying why individuals with greater PTS symptom severity are more likely to report elevated marijuana use coping motives remain unclear.

Distress tolerance (DT), often conceptualized as the perceived or actual ability to withstand aversive physical or emotional stimuli (Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, Strong, & Zvolensky, 2005; Simons & Gaher, 2005), offers one promising explanatory factor for the association between PTS symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives. DT is a theoretically malleable factor (e.g., Linehan, 1993) that has been related to both PTS symptom severity (Marshall, Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, Bernstein, & Zvolensky, in press; Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, Potter, Marshall, & Zvolensky, in press; Vujanovic, Bernstein, & Litz, 2010) and marijuana use motives (Simons & Gaher, 2005; Zvolensky et al., 2009). Although there is a dearth of literature examining the relation between DT and PTS (Vujanovic et al., 2010), emerging cross-sectional empirical work among trauma-exposed community samples suggests significant (inverse) associations between DT and PTS symptom severity, such that higher levels of DT co-occur with lower levels of PTS symptom severity (Marshall et al., in press; Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, et al., in press). More specifically, the perceived ability to withstand emotional distress, as measured by the Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS; Simons & Gaher, 2005), may be especially relevant to PTS symptom severity, more so than behavioral indices of the construct (Marshall et al., in press).

DT has also emerged as a cognitive-affective mechanism for better understanding substance use development and relapse (Richards, Daughters, Bornovalova, Brown, & Lejuez, 2010), generally, and problematic marijuana use, more specifically (Buckner, Keough, & Schmidt, 2007; Simons & Gaher, 2005; Zvolensky et al., 2009). For example, DT has demonstrated negative associations with substance use and positive associations with abstinence duration (Richards et al., 2010), examined among individuals using alcohol (e.g., Daughters et al., 2009), nicotine (e.g., Brandon et al., 2003; Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, & Strong, 2002), and other illicit substances (e.g., Daughters, Lejuez, Kahler, Strong, & Brown, 2005; O’Cleirigh, Ironson, & Smits, 2007). Furthermore, DT has demonstrated negative associations with motivation to use these substances (Simons & Gaher, 2005; Vujanovic, Marshall-Berenz, & Zvolensky, in press).

Consistent with these observations among other substances, the observed association between DT and problematic marijuana use suggests that individuals with lower levels of tolerance for withstanding distress may be especially likely to use marijuana to regulate their emotions (Buckner et al., 2007). Indeed, the only consistent finding in previous studies on DT and marijuana use motives has been that DT is significantly related to coping-oriented marijuana use motives (Simons & Gaher, 2005; Zvolensky et al., 2009). Theoretically, individuals with lower levels of DT may be especially likely to use marijuana to cope with emotional distress due to their tendencies to perceive their abilities to tolerate emotional distress as compromised.

To date, no studies have examined: (1) the unique associations between DT and marijuana use motives among trauma-exposed marijuana users; or (2) the theoretical role of DT in the established association between PTS symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives. There is great potential clinical utility in examining these associations in order to determine whether it would be fruitful to target DT via intervention to reduce coping-oriented marijuana use among trauma-exposed populations. Taken together, the extant literature suggests: (a) PTS symptom severity is positively associated with higher levels of marijuana use coping motives (Bonn-Miller et al., 2007); (b) DT is inversely associated with PTS symptom severity (Marshall et al., in press; Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, et al., in press); and (c) DT is inversely associated with levels of marijuana use coping motives, specifically (Simons & Gaher, 2005; Zvolensky et al., 2009). Thus, DT may help explain (i.e., mediate) the association between higher levels of PTS symptom severity and greater levels of coping-oriented marijuana use among trauma-exposed marijuana users. That is, a lower perceived capacity to withstand emotional distress, including PTS symptoms, may help explain the tendency for individuals with higher levels of PTS symptoms to use marijuana to cope with emotional distress.

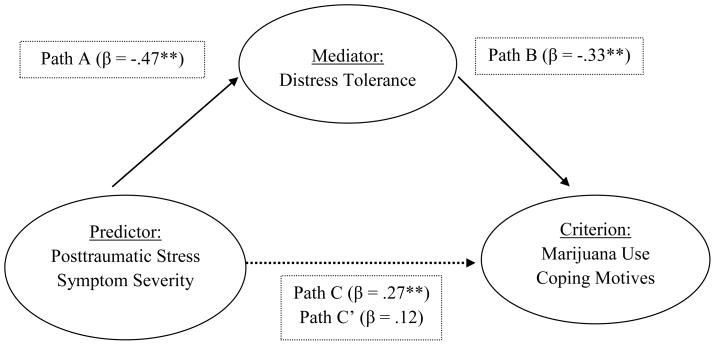

In the present investigation, we sought to address these gaps in the literature by examining the potential mediating role of DT in the relation between PTS symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives among a community-recruited sample of trauma-exposed individuals reporting marijuana use within the past 30 days. Consistent with a formal test of mediation, three hypotheses were conceptualized. First, it was hypothesized that higher levels of PTS symptom severity would be significantly associated with greater levels of marijuana use coping motives, beyond the variance contributed by marijuana use frequency and non-criterion marijuana use motives (i.e., Enhancement, Conformity, Expansion, and Social motives). Second, higher levels of PTS symptom severity would be significantly associated with lower levels of DT, beyond the variance contributed by marijuana use frequency. Finally, lower levels of DT would mediate the relation between higher levels of PTS symptom severity and greater levels of marijuana use coping motives, beyond the variance contributed by marijuana use frequency and non-criterion marijuana use motives, such that the association between PTS symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives would be eliminated with the inclusion of DT in the model (please see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distress tolerance as mediator of the association between posttraumatic stress symptoms and marijuana use coping motives.

Note. **p < .001. Path A: association between predictor and mediator; Path B: association between mediator and criterion; Path C: association between predictor and criterion; Path C’: association between predictor and criterion, after accounting for the mediator.

Method

Participants

The sample was comprised of 142 adults (46.5% women; Mage = 22.18, SD = 7.22, range = 18–55) recruited from the greater Burlington, Vermont, community. The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was generally consistent with that of the State of Vermont (State of Vermont, Department of Health, 2009): approximately 95.8% of participants identified as white/Caucasian, 0.7% identified as Asian, 0.7% identified as Hispanic/Latino, and 1.4% identified as “other.”

The current study data were yielded from a larger database focused on emotional vulnerability. Approximately 47.2% (n = 67) of participants who comprise the present sample were recruited for studies that excluded for current (past month) axis I disorders; and approximately 52.8% (n = 75) of participants who comprise the present sample were recruited for studies that did not exclude for current (past month) axis I disorders. Exclusionary criteria across studies included: (a) limited mental competency and/or the inability to provide informed, written consent, (b) psychotic-spectrum psychopathology, (c) current suicidal ideation, (d) current or past chronic cardiopulmonary illness (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), (e) current respiratory illness (e.g., bronchitis), seizure disorder, cardiac dysfunction, or other serious medical illness, and (f) pregnancy. Inclusionary criteria were comprised of: (a) being an adult over the age of 18; (b) endorsing exposure to a PTSD Criterion A life traumatic event1; and (c) reporting marijuana use within the past 30 days.

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV–Non-Patient Version (SCID-I/N-P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995)

The SCID-I/N-P was used to index current (past month) Axis I diagnoses and assess exclusionary criteria (please see above). The non-patient version was used since participants were a community sample, and not a treatment-seeking clinical sample. The DSM-IV version of the SCID-I/N-P has been shown to have good reliability (Zanarini et al., 2000) and good to excellent validity (Basco et al., 2000). In the present study, all SCID-I/N-P administrations were conducted by trained clinical assessors and reviewed by the PIs to ensure inter-rater agreement. A random sampling of 20% of the SCID-I/NP administrations was reviewed by the PIs to ensure inter-rater agreement. No cases of disagreement were noted.

Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (Foa, 1995)

The PDS is a 49-item self-report instrument designed to assess the presence of posttraumatic stress symptoms, based on DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994, 2000). Respondents report if they have experienced any of 12 traumatic events, including an “other” category, and then indicate which event was most disturbing. Respondents also rate the frequency (0 = “not at all” or “only one time” to 3 = “five or more times a week/almost always”) of 17 PTSD symptoms experienced in the past month in relation to the most-disturbing event endorsed (total score range of 0 to 51); these 17 symptom items are summed to assess posttraumatic stress symptom severity. The PDS is a measure of trauma-related symptoms with generally excellent psychometric properties (Foa, Cashman, Jaycox, & Perry, 1997; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993). In this study, the PDS was utilized to: (1) index DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A traumatic event exposure, (2) assess posttraumatic stress symptom severity, and (3) assess diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Prior work has demonstrated that the PDS has high internal consistency (alpha = .92) and test-retest reliability (kappa = .74). In the present sample, the PDS (total symptom severity score) demonstrated high internal consistency (alpha = .95).

Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS; Simons & Gaher, 2005)

The DTS is a self-report measure on which respondents indicate, on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = “strongly agree” to 5 = “strongly disagree”), the extent to which they believe they can experience and withstand distressing emotional states (Simons & Gaher, 2005). The DTS encompasses four types of emotional distress items including: perceived ability to tolerate emotional distress (e.g., “I can’t handle feeling distressed or upset”), subjective appraisal of distress (e.g., “My feelings of distress or being upset are not acceptable”), attention absorption by negative emotions (e.g., “When I feel distressed or upset, I cannot help but concentrate on how bad the distress actually feels”), and regulation efforts to alleviate distress (e.g., “I’ll do anything to avoid feeling distressed or upset;” Simons & Gaher, 2005). The original 14-item version of the DTS (cf., the more recent 15-item version) was administered as a function of the time period during which these data were collected. Notably, the item not included in the 14-item version (i.e., “When I feel distressed or upset, I must do something about it immediately”) is intended only for computation of subscale scores, not the DTS total score (Simons & Gaher, 2005). High levels of DT are indicated by higher total scores on the DTS (Simons & Gaher, 2005). As in past work, the DTS total score was employed as a global index of perceived distress tolerance (Leyro, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2010). To date, the DTS has been demonstrated to be the most promising index of DT with regard to PTS symptom severity (Marshall et al., in press; Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, et al., in press) and marijuana use motives (Zvolensky et al., 2009). The DTS has excellent psychometric properties (Simons & Gaher, 2005). In the present sample, the DTS demonstrated high internal consistency (alpha = .92).

Marijuana Motives Measure (MMM; Simons, Correia, Carey, & Borsari, 1998)

The MMM is a 25-item measure on which respondents indicate, on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = “almost never / never” to 5 = “almost always / always”), the degree to which they smoke marijuana for a variety of possible reasons (e.g. “to be sociable”). The MMM consists of five first-order factors: (1) Enhancement (e.g., “to get high”); (2) Conformity (e.g., “to fit into the group I like”); (3) Expansion (e.g., “to expand my awareness”); (4) Coping (e.g., “to forget my worries”); and (5) Social (e.g., “makes social gatherings more fun”). The MMM has excellent psychometric properties, including high internal consistency (intra-class alpha = .70–.92; Chabrol, Ducongé, Casas, Roura, & Carey, 2005; Simons et al. 1998; Zvolensky et al., 2007; Zvolensky et al. 2009). In the present sample, internal consistency for the MMM factors ranged from: alpha = .76 (Conformity) to alpha = .91 (Expansion).

Marijuana Smoking History Questionnaire (MSHQ; Bonn-Miller & Zvolensky, 2009)

The MSHQ is a self-report instrument that assesses marijuana smoking rate (lifetime and past 30 days), age of onset at use initiation, years of being a regular marijuana smoker, and other related descriptive information (e.g., number of attempts to discontinue using marijuana). The MSHQ has been employed successfully in the past as a descriptive measure of marijuana use history and pattern (e.g., Bonn-Miller et al., 2007; Bonn-Miller & Zvolensky, 2009). The current study utilized the item rating marijuana use in the past 30 days to index marijuana use frequency.

Procedure

Individuals who responded to advertisements about a study on emotion were scheduled for a session in the laboratory to determine eligibility and collect study data. Upon arrival to the laboratory, interested participants first provided verbal and written informed consent. The SCID-I/N-P was then administered to determine eligibility based on the criteria identified above. Eligible participants completed a battery of self-report measures and received $25 compensation for their involvement with the study. Data collection for the current study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Vermont.

Data Analytic Plan

First, descriptive characteristics of participants were evaluated with regard to trauma exposure and symptoms and marijuana use. Second, a series of zero-order correlations was conducted to examine associations among variables. Third, the mediating role of DT (i.e., DTS–total score) in the relation between PTS symptoms (i.e., PDS–total score) and marijuana use coping motives (i.e., MMM–Coping motives) was examined, using Baron and Kenny’s (1986) recommended test of mediation. Specifically, the test requires the following series of multiple regressions: (1) the predictor variable (i.e., PDS–total score) must be significantly associated with the criterion variable (i.e., MMM–Coping motives), as depicted by Figure 1–Path C; (2) the predictor variable (i.e., PDS–total score) must be significantly associated with the proposed mediator (i.e., DTS - total score), as depicted by Figure 1–Path A; and (3) when the predictor (i.e., PDS–total score) and mediator (i.e., DTS total score) are entered simultaneously into a third multiple regression, the mediator (i.e., DTS–total score) must be significantly associated with the criterion (i.e., MMM–Coping motives), as depicted by Figure 1–Path B; and the relation between the predictor and criterion is either diminished (partial mediation) or eliminated (full mediation) as a function of the inclusion of the mediator, as depicted by Figure 1- Path C’. Marijuana use frequency (MSHQ–marijuana use in past 30 days) and non-criterion marijuana use motives (i.e., Enhancement, Conformity, Expansion, and Social motives) were entered as covariates in the regression equations when marijuana use coping motives was the criterion variable; and only marijuana use frequency was entered as a covariate when DT was a criterion variable.2 An alpha level of .01 was applied to all analyses to control for family-wise error attributable to the number of proposed analyses conducted (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

Results

Participant Characteristics

All participants endorsed lifetime exposure to a PTSD Criterion A traumatic event1, as assessed by the PDS (Foa 1995), and reported marijuana use within the past 30 days, as assessed by the MSHQ (Bonn-Miller & Zvolensky, 2009). On average, participants reported experiencing a mean of 2.3 different types of traumatic events. According to the PDS, approximately 5.6% of participants met criteria for PTSD. Participants’ “worst” traumatic events, as per responses on the PDS, included: serious accident, fire, or explosion (23.2%), non-sexual assault by a family member or someone known (10.6%), sexual assault by a family member or someone known (8.5%), life-threatening illness (8.5%), natural disaster (7.0%), non-sexual assault by a stranger (7.0%), sexual assault by a stranger (5.6%), sexual contact when younger than 18 years with someone five or more years older (2.8%), imprisonment (2.1%), military combat or a war zone (.7%), torture (.7%), and “other” trauma type (e.g., sudden, unexpected death of a friend or family member, witnessing the assault or death of a stranger or family member; 19.7%). With regard to marijuana use, 36.6% of the sample reported using marijuana less than once per week; 9.9% used once per week; 31.7% used more than once per week, but not multiple times daily; and 21.8% used multiple times per day.

The SCID-I/N-P (First et al., 1995) was administered to index current Axis I psychopathology (i.e., past month for all disorders; substance use disorders not assessed) and assess exclusionary criteria (please see Procedure section). Approximately 36.5% of participants met diagnostic criteria for a current Axis I disorder. Of the total sample, approximately 9.9% met criteria for generalized anxiety disorder; 6.3% for major depressive disorder; 4.2% for social phobia; 4.2% for specific phobia; 2.1% for dysthymia; and 2.1% for obsessive compulsive disorder.

Zero-Order Correlations

Please see Table 1 for descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations. PTS symptom severity was significantly positively related to marijuana use coping motives (r = .37, p < .01), and significantly negatively related to DT (r = −.47, p < .01). Furthermore, DT was significantly negatively related to marijuana use coping motives (r = −.37, p < .01). PTS symptom severity was also significantly related to marijuana use expansion motives (r = .24, p < .01), while DT levels were not significantly related to marijuana use expansion motives (r = .11, p > .01). Overall, only the marijuana use coping motives variable was significantly related to both PTS and DT levels.

Table 1.

Zero-Order Correlations and Descriptive Data among Theoretically-Relevant Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PDS | - | −.47* | .08 | .03 | .06 | .24* | .18 | .37* | 7.49 (9.72) |

| 2. DTS | - | - | .02 | .17 | −.09 | −.11 | −.00 | −.37* | 3.48 (.83) |

| 3. Marijuana Use Frequency | - | - | - | .35* | −.01 | .40* | .30* | .36* | 4.64 (2.56) |

| 4. MMM-Enhancement | - | - | - | - | −.03 | .38* | .43* | .37* | 3.56 (.95) |

| 5. MMM-Conformity | - | - | - | - | - | .14 | .31* | .16 | 1.35 (.52) |

| 6. MMM-Expansion | - | - | - | - | - | - | .42* | .46* | 2.15 (1.11) |

| 7. MMM-Social | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .39* | 2.36 (.92) |

| 8. MMM-Coping | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.12 (1.05) |

Note. Marijuana Use Frequency – levels of marijuana use in past 30 days (MSHQ; Bonn-Miller & Zvolensky, 2009); MMM-Enhancement – Marijuana Motives Measure – (Enhancement motives subscale); MMM-Conformity – Marijuana Motives Measure (Conformity motives subscale); MMM-Expansion – Marijuana Motives Measure (Conformity motives subscale); MMM-Social – Marijuana Motives Measure (Social motives subscale); MMM-Coping – Marijuana Motives Measure (Coping motives subscale; Simons et al., 1998); PDS – Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale total score (Foa, 1995); DTS – Distress Tolerance Scale total score (Simons and Gaher, 2005); DTS -- Distress Tolerance Scale total score (Simons & Gaher, 2005).

p < .01

Mediation Analyses

Please refer to Table 2 for a summary of mediation analyses and Figure 1 for a depiction of the proposed conceptual model of mediation.

Table 2.

Test of Distress Tolerance as a Mediator in the Association between Posttraumatic Stress Symptom Severity and Marijuana Use Coping Motives

| ΔR2 | t | β | sr2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion Variable: Marijuana Use Coping Motives: Test of Path C | |||||

| Step 1 | .132 | <.001 | |||

| Marijuana Use | 4.61 | .36 | .13 | <.001 | |

| Step 2 | .175 | <.001 | |||

| MMM-Enhancement | 1.93 | .16 | .02 | ns | |

| MMM-Conformity | 1.18 | .09 | .01 | ns | |

| MMM-Expansion | 3.14 | .26 | .06 | .002 | |

| MMM-Social | 1.44 | .12 | .01 | ns | |

| Step 3 | .071 | <.001 | |||

| PDS | 3.92 | .27 | .10 | <.001 | |

| Criterion Variable: Distress Tolerance: Test of Path A | |||||

| Step 1 | .001 | ns | |||

| Marijuana Use | .28 | .02 | .00 | ns | |

| Step 2 | .227 | < .001 | |||

| PDS | −6.39 | −.47 | .22 | <.001 | |

| Criterion Variable: Marijuana Use Coping Motives: Tests of Paths B & C’ | |||||

| Step 1 | .132 | <.001 | |||

| Marijuana Use | 4.61 | .36 | .13 | <.001 | |

| Step 2 | .175 | <.001 | |||

| MMM-Enhancement | 1.93 | .16 | .02 | ns | |

| MMM-Conformity | 1.18 | .09 | .01 | ns | |

| MMM-Expansion | 3.14 | .26 | .06 | .002 | |

| MMM-Social | 1.44 | .12 | .01 | ns | |

| Step 3 | .153 | <.001 | |||

| PDS | 1.63 | .12 | .01 | ns | |

| DTS | −4.51 | −.33 | .13 | <.001 | |

Note. Marijuana Use–marijuana use in past 30 days (MSHQ; Bonn-Miller & Zvolensky, 2009); MMM-Enhancement–Marijuana Motives Measure (Enhancement motives subscale); MMM-Conformity–Marijuana Motives Measure (Conformity motives subscale); MMM-Expansion Marijuana Motives Measure (Conformity motives subscale); MMM-Social Marijuana Motives Measure (Social motives subscale); MMM-Coping Marijuana Motives Measure (Coping motives subscale; Simons et al., 1998); PDS–Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale total score (Foa, 1995); DTS Distress Tolerance Scale total score (Simons and Gaher, 2005); DTS -- Distress Tolerance Scale total score (Simons & Gaher, 2005).

Path C

As expected, PTS symptom severity demonstrated a significant incremental association with marijuana use coping motives, beyond the variance contributed by marijuana use frequency and non-criterion marijuana use motives (t = 3.92, β = .27, sr2 = .10, p < .001).

Path A

As expected, PTS symptom severity demonstrated a significant incremental association with DT, beyond the variance contributed by marijuana use frequency (t = −6.39, β = −.47, sr2 = .22, p < .001).

Path B/C’

As expected, DT demonstrated a significant association with marijuana use coping motives (t = −4.51, β = −.33, sr2 = .13, p < .001), beyond the variance contributed by marijuana use frequency and non-criterion marijuana use motives. Furthermore, as predicted, the association between PTS symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives levels diminished significantly with the inclusion of DT in the model (β decreased from .27 to .12; sr2 decreased from .10 to .01), rendering it statistically non-significant (p > .01). These findings suggest that DT partially mediated the association between PTS symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives (Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998).

One method of strengthening the interpretation of mediational analyses associated with cross-sectional data is to conduct an additional analysis reversing the proposed mediator and criterion variables (Preacher & Hayes, 2004; Sheets & Braver, 1999; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Here, we evaluated whether marijuana use coping motives mediated the association between PTS symptom severity and DT. Results were not consistent with mediation in this direction, as PTS symptom severity remained a significant predictor of DT, even after controlling for marijuana use and marijuana use coping motives (t = −4.90, β = −.37, sr2 = .14, p < .001).

Discussion

Results were consistent with hypotheses. First, as expected, higher levels of PTS symptom severity were significantly associated with greater levels of marijuana use coping motives, beyond the variance contributed by marijuana use frequency and non-criterion marijuana use motives. This finding replicates prior work establishing an association between PTS symptom severity and coping-oriented marijuana use, specifically (Bremner et al., 1996; Bonn-Miller et al., 2007), and coping-oriented substance use, more broadly (Beckham et al., 1995, 1997; Dixon et al., 2009; Feldner, Babson, & Zvolensky 2007; Feldner et al., 2007; Stewart et al., 2000; Stewart et al., 2004; Ullman et al., 2006). Thus, it may be clinically useful to integrate coping skills into treatments for marijuana users with PTS symptoms or PTSD to help reduce their reliance on marijuana as a coping mechanism (e.g., Najavits, 2002). To further inform this line of study, experimental and prospective designs examining the directionality of the PTS-marijuana use coping motives association are needed.

Second, as expected, PTS symptom severity demonstrated a significant, concurrent (positive) association with DT, even after accounting for the significant variance in DT explained by marijuana use frequency. This finding is consistent with prior work documenting the association between PTS and perceived tolerance of emotional distress (Marshall et al., in press; Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, et al., in press). Notably, the reliance on cross-sectional methodology in the extant empirical literature related to DT and PTS underscores the importance of evaluating the temporal and causal directionality underlying the observed effects, using experimental and prospective designs. Theoretically, there are several possibilities regarding the directionality of the observed DT-PTS association (Vujanovic et al., 2010). First, it is plausible that DT levels may change (increase or decrease) as a function of exposure to traumatic stressors. Second, PTS symptom severity may promote less tolerance of distress over time. Third, lower or higher levels of DT prior to trauma exposure may predispose an individual to a course toward risk or resilience, respectively. Fourth, DT and PTS symptom levels may relate bi-directionally or transactionally, as noted in prospect work related to similar emotional vulnerability processes (e.g., Marshall, Miles, & Stewart, 2010).

Finally, as expected, the association between PTS symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives diminished significantly with the inclusion of DT in the model (β decreased from .27 to .12; sr2 decreased from .10 to .01), suggesting that lower levels of DT partially accounted for the PTS-marijuana use coping motives association. Although the inclusion of DT in the model rendered the PTS-marijuana use coping motives association statistically non-significant, the current results support partial rather than full mediation, as the beta weight did not decrease to zero (Kenny et al., 1998). This finding suggests that perceived tolerance of emotional distress may be an important cognitive-affective mechanism underlying the PTS-marijuana use coping motives association. Theoretically, it is possible that a lower perceived capacity to withstand emotional distress may explain the tendency for trauma-exposed individuals with higher levels of PTS symptoms to use marijuana for coping reasons. As this is the first study to examine DT and marijuana use motives among trauma-exposed individuals, these results should be interpreted as preliminary support for the proposed mediational model of the relations between PTS symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives (see Figure 1). However, the temporal order of associations among PTS, DT, and marijuana use coping motives cannot be inferred from the present cross-sectional design.

The present findings have at least four noteworthy clinical implications that might be examined in future work. First, as DT is a cognitive-affective mechanism related to both PTS symptom severity and coping oriented marijuana use, it could be promising to target DT in the context of treatment for co-occurring PTS and marijuana use problems (e.g., distress tolerance module of dialectical behavior therapy, Linehan, 1993). Increased DT skills might potentially improve such individuals’ ability to cope with posttraumatic stress and related negative mood states without the use of marijuana. Second, it might be fruitful to examine the role of DT in the relations between other aspects of trauma-relevant sequelae (e.g., panic attacks) and coping motives for marijuana use. Third, it may be useful to explore the relation between DT and other processes associated with problematic marijuana use, such as emotion regulation or mindfulness and acceptance (Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, & Zvolensky, 2008; Shafil, Lavely, & Jaffe, 1974; Twohig, Shoenberger, & Hayes, 2007). Fourth, DT may similarly be associated with other emotionally-salient aspects of problematic marijuana use (e.g., withdrawal symptoms, duration of ability to maintain abstinence, probability of relapse), beyond those observed in the present study.

Though promising, the current investigation has several noteworthy limitations to be considered in interpreting the present findings and advancing this line of empirical inquiry. First, as previously noted, the present study employed a cross-sectional design, not permitting an examination of the temporal relations of the variables studied. Thus, it is important for future work to replicate and extend the concurrent associations documented in the present investigation using prospective designs. Second, the racial/ethnic homogeneity of the current sample limits the generalizability of the findings, underscoring the importance of replication with more diverse samples. Third, observed associations between self-report measures of PTS, DT, and coping motives may be inflated due to shared method variance. Future studies would be strengthened by multi-method assessment strategies (e.g., laboratory tasks with physiological monitoring, structured interviews of psychological and substance use symptoms). Fourth, the current trauma-exposed sample exhibited relatively low levels of PTS symptom severity, with only 5.6% of the sample meeting criteria for PTSD, limiting the extent to which these findings are generalizable to clinical samples with PTSD. Additionally, PTS symptom severity was found to be related to only coping and expansion motives for marijuana use, at the zero-order level, and neither DT nor PTS symptom severity were found to be related to marijuana use frequency. Though these findings are consistent with prior study of sub-clinical populations (Bonn-Miller et al., 2007; Buckner et al., 2007; Simons & Gaher, 2005; Zvolensky et al., 2009), alternate relations have been observed among clinical populations (e.g., the relation between PTSD symptoms and marijuana use frequency; Bonn-Miller et al., in press; Bremner et al., 1996). It is important for future work to replicate and extend the present study among clinical populations with PTSD and/or greater variability in PTS symptom severity. Finally, substance use disorders, including marijuana use disorders, were not assessed. Though the measure employed to determine current marijuana use status and frequency has been used often in prior literature (e.g., Bonn-Miller et al., 2007; Bonn-Miller & Zvolensky, 2009), future research may benefit from the assessment of drug potency and marijuana abuse and dependence.

Overall, the current study presents novel results regarding the associations between PTS, DT, and marijuana use coping motives among a sample of trauma-exposed individuals. Results suggest that DT may partially mediate the replicated association between PTS symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives. This preliminary investigation is intended to stimulate future work examining the cognitive-affective mechanisms underlying the clinically important relations between PTS and coping-oriented marijuana use.

Research Highlights.

The present investigation examined the explanatory (i.e. mediating) role of distress tolerance in the relation between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives, among a community-recruited sample.

Results demonstrated that distress tolerance partially mediated the relation between posttraumatic stress symptom severity and coping-oriented marijuana use.

These preliminary results suggest that distress tolerance may be an important cognitive-affective mechanism underlying the posttraumatic stress-marijuana use coping motives association.

Theoretically, trauma-exposed marijuana users with greater posttraumatic stress symptom severity may use marijuana to cope with negative mood states, at least partially because of a lower perceived capacity to withstand emotional distress.

Acknowledgments

Data collection for this project was supported by a National Institute on Drug Abuse National Research Service Award (1F31 DA21006-02) granted to Dr. Vujanovic, a National Institute on Mental Health National Research Service Award (1 F31 MH080453-01A1) granted to Erin C. Marshall, and a National Institute on Mental Health National Research Service Award (F31 MH073205-01) granted to Dr. Amit Bernstein. The authors express appreciation to Dr. Michael J. Zvolensky of The University of Vermont for contributing a portion of the data presented for purposes of the current study (1 R03 DA016566-01A2). Dr. Bonn-Miller acknowledges that this work was supported, in part, by a Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development (CSR&D) Career Development Award–2. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

A traumatic event was defined according to DSM-IV-TR PTSD Criterion A. According to Criterion A, a traumatic event is defined as one in which an individual “experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event…that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others” and the individual’s response “involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror,” as defined by the DSM-IV-TR Posttraumatic Stress Disorder diagnosis criteria (APA, 2000, p. 467).

The use of co-occurring substances (i.e., tobacco use or alcohol consumption) were not entered as covariates in the regression analyses as they were not related, at the zero-order level, with either PTS symptom severity or MMM–Coping motives (p > .10).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Carrie M. Potter, Email: carrie.potter@va.gov.

Anka A. Vujanovic, Email: anka.vujanovic@va.gov.

Erin C. Marshall-Berenz, Email: erin.berenz@gmail.com.

Amit Bernstein, Email: abernstein@psy.haifa.ac.il.

Marcel O. Bonn-Miller, Email: marcel.bonn-miller@va.gov.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basco MR, Bostic JQ, Davies D, Rush AJ, Witte B, Hendrickse W, Barnett V. Methods to improve diagnostic accuracy in a community mental health setting. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1599–1605. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Kirby AC, Feldman ME, Hertzberg MA, Moore SD, Crawford AL, Fairbank JA. Prevalence and correlates of heavy smoking in Vietnam veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:637–647. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(96)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Roodman AA, Shipley RH, Hertzberg MA, Cunha GH, Kudler HS, Fairbank JA. Smoking in Vietnam combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:461–472. doi: 10.1007/BF02102970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Babson KA, Vujanovic AA, Feldner MT. Sleep problems and PTSD symptom interact to predict marijuana use coping motives. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2010;6:111–122. doi: 10.1080/15504261003751887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Drescher KD. Cannabis use among military veterans following residential treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0021945. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Feldner MT, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ. Posttraumatic stress symptom severity predicts marijuana use coping motives among traumatic event-exposed marijuana users. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:577–586. doi: 10.1002/jts.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ. Emotional dysregulation: Association with coping-oriented marijuana use motives among current marijuana users. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43:1653–1665. doi: 10.1080/10826080802241292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ. An evaluation of the nature of marijuana use and its motives among young adult active users. The American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18:409–416. doi: 10.1080/10550490903077705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon T, Herzog T, Juliano L, Irvin J, Lazev A, Simmons V. Pretreatment task persistence predicts smoking cessation outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:448–456. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Darnell A, Charney DS. Chronic PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans: Course of illness and substance abuse. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:369–375. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:180–185. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.111.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:713–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Keough ME, Schmidt NB. Problematic alcohol and cannabis use among young adults: The roles of depression and discomfort and distress tolerance. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrol H, Ducongé E, Casas C, Roura C, Carey K. Relations between cannabis use and dependence, motives for cannabis use and anxious, depressive and borderline symptomatology. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:829–840. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Psychological distress tolerance and duration of most recent abstinence attempt among residential treatment-seeking substance abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:208–211. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Reynolds EK, McPherson L, Kahler CW, Danielson CK, Zvolensky M, Lejuez CW. Distress tolerance and early adolescent externalizing and internalizing symptoms: The moderating role of gender and ethnicity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LJ, Leen-Feldner EW, Ham LS, Feldner MT, Lewis SF. Alcohol use motives among traumatic event-exposed, treatment-seeking adolescents: Associations with posttraumatic stress. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:1065–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Babson KA, Zvolensky MJ. Smoking, traumatic event exposure, and post-traumatic stress: A critical review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:14–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Babson KA, Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Lewis SF, Gibson LE, Bernstein A. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and smoking to reduce negative affect: An investigation of trauma-exposed daily smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:214–227. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (nonpatient edition) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB. Posttraumatic stress diagnostic scale manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:445–451. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.9.4.445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490060405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Bolger N. Data analysis in social psychology. In: Gilbert D, Fiske S, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4. Vol. 1. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:576–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lipschitz DS, Rasmusson AM, Anyan W, Gueorguieva R, Billingslea EM, Cromwell PF, Southwick SM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use in inner-city adolescent girls. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191:714–721. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000095123.68088.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall EC, Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ. Multi-method study of distress tolerance and PTSD symptom severity in a trauma-exposed community sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. doi: 10.1002/jts.20568. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GN, Miles JNV, Stewart SH. Anxiety sensitivity and PTSD symptom severity are reciprocally related: Evidence from a longitudinal study of physical trauma survivors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:143–150. doi: 10.1037/a0018009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM. Seeking safety: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C, Ironson G, Smits JAJ. Does distress tolerance moderate the impact of major life events on psychosocial variables and behaviors important in the management of HIV? Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Daughters SB, Bornovalova MA, Brown RA, Lejuez CW. Distress tolerance and substance use disorders. In: Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA, editors. Distress tolerance. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach LA, Grana R, Vernberg E, Sussman S, Sun P. Impact of Hurricane Rita on adolescent substance use. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2009;72:222–237. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2009.72.3.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafil M, Lavely R, Jaffe R. Meditation and marijuana. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1974;131:60–63. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets VL, Braver SL. Organizational status and perceived sexual harassment: Detecting the mediators of a null effect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:1159–1171. doi: 10.1177/01461672992512009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. doi: 10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J, Correia CJ, Carey KB, Borsari BE. Validating a five-factor marijuana motives measure: Relations with use, problems, and alcohol motives. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1998;45:265–273. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The distress tolerance scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29:83–102. doi: 10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- State of Vermont, Department of Health. Retrieved June 30, 2009, from http://www.healthyvermonters.info/

- Stewart SH, Conrod PJ, Samoluk SB, Pihl RO, Dongier M. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and situation-specific drinking in women substance abusers. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2000;18:31–47. doi: 10.1300/J020v18n03_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Mitchell TL, Wright KD, Loba P. The relations of PTSD symptoms to alcohol use and coping drinking in volunteers who responded to the Swissair flight 111 airline disaster. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18:51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Twohig MP, Shoenberger D, Hayes SC. A preliminary investigation of acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for marijuana dependence in adults. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:619–632. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.619?632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Correlates of comorbid PTSD and drinking problems among sexual assault survivors. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Boscarino JA, Bucuvalas M, Kilpatrick D. Increased use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among Manhattan, New York, residents after the September 11th terrorist attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155:988–996. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.11.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Bernstein A, Litz BT. Traumatic stress. In: Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA, editors. Distress tolerance. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Potter C, Marshall EC, Zvolensky MJ. An evaluation of the relation between distress tolerance and posttraumatic stress within a trauma-exposed sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. doi: 10.1007/s10862-010-9209-2. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Marshall-Berenz EC, Zvolensky MJ. Posttraumatic stress and alcohol use motives: A test of the incremental and mediating role of distress tolerance. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.25.2.130. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, Gunderson JG. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, Johnson K, Hogan J, Bernstein A, Bonn-Miller MO. Relations between anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and fear reactivity to bodily sensations to coping and conformity marijuana use motives among young adult marijuana users. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:31–42. doi: 10.1037/a0014961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Bernstein A, Bonn-Miller MO, Marshall EC, Leyro TM. Marijuana use motives: A confirmatory test and evaluation among young adult marijuana users. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:3122–3130. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]