This study provides the first evidence that P2X7 receptors are expressed in native and cultured human RPE cells and that activation of P2X receptors, especially P2X7 receptors, induces both Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis in cultured human RPE cells. The findings suggest abnormal Ca2+ homeostasis through the activation of P2X receptors could cause the RPE dysfunction and apoptosis that underlie age-related macular degeneration.

Abstract

Purpose.

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is considered a primary site of pathology in age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which is the most prevalent form of irreversible blindness worldwide in the elderly population. Extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) acts as a key signaling molecule in numerous cellular processes, including cell death. The purpose of this study was to determine whether extracellular ATP induces apoptosis in cultured human RPE.

Methods.

RPE apoptosis was evaluated by caspase-3 activation, Hoechst staining, and DNA fragmentation. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were determined by both a cell-based fluorometric Ca2+ assay and a ratiometric Ca2+ imaging technique. P2X7 mRNA and protein expression were detected by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and confocal microscopy, respectively.

Results.

The authors found that both the endogenous P2X7 agonist ATP and the synthetic, selective P2X7 agonist 2′,3′-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl)-ATP (BzATP) induced RPE apoptosis, which was significantly inhibited by P2X7 antagonist oxidized ATP (oATP) but not by the P2 receptor antagonist suramin; both ATP and BzATP increase intracellular Ca2+ via extracellular Ca2+ influx; both ATP- and BzATP-induced Ca2+ responses were significantly inhibited by oATP but not by suramin; ATP-induced apoptosis was significantly inhibited or blocked by BAPTA-AM or by low or no extracellular Ca2+; and P2X7 receptor mRNA and protein were expressed in RPE cells.

Conclusions.

These findings suggest that P2X receptors, especially P2X7 receptors, contribute to ATP- and BzATP-induced Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis in the RPE. Abnormal Ca2+ homeostasis through the activation of P2X receptors could cause the dysfunction and apoptosis of RPE that underlie AMD.

Extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) acts as a key signaling molecule in numerous cellular processes and is viewed as an endogenous danger signal released in large quantities by cells after inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell injury.1,2 It activates a class of cell-surface nucleotide receptors termed P2 receptors that are further categorized into P2Y receptors and P2X receptors.3 P2 receptors are widely expressed in excitable and nonexcitable cells, where they play important functions.4–8 P2Y receptor expression and function have been reported in human, rat, bovine, and rabbit retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).9–18

Little is known of P2X receptors in the RPE. Ryan et al.13 suggested that in addition to P2Y receptors, cultured rat RPE cells exhibited functional P2X receptors. Dutot et al.19 showed that ATP and a selective P2X7 agonist 2′,3′-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl)-ATP (BzATP) stimulated YO-PRO-1 dye uptake and confocal immunofluorescence microscopy detected P2X7 receptor protein in a human RPE cell line, ARPE-19 cells. Among seven P2X receptors, the P2X7 receptor is unique because it plays a critical role in oxidative stress, cell death, and inflammation as well as in several diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and kidney diseases.20,21 However, the role of this receptor in the RPE is unknown. Because oxidative stress, cell death, and inflammation are implicated in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and apoptotic RPE death underlies AMD,22,23 we hypothesized that ATP may induce RPE apoptosis by activation of the P2X7 receptor. By combining molecular, functional, and pharmacologic approaches, we show that the P2X7 receptor is expressed in native and cultured human RPE and that activation of the P2X7 receptor induces both Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis in RPE cells.

Methods

Materials

Ninety-six–well black clear-bottom plates were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Costar; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and 35-mm glass bottom culture dishes were purchased from MatTek Corporation (Ashland, MA). Hoechst 33342, ATP, BzATP, brilliant blue G (BBG), KN-62, suramin, 1,2-Bis (2-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetrakis (acetoxymethyl ester) (BAPTA-AM), and oxidized ATP (oATP) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Hanks' balanced salt solutions (HBSS), N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N'-(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES), a RNA isolation reagent (Trizol), Taq DNA polymerase, AlexaFluor 555 goat anti-rabbit IgG, and Indo-1-AM (acetoxymethyl ester) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-P2X7 antibody was purchased from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Mounting medium with DAPI was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Caspase-3 assay kit was purchased from Biotium, Inc. (NucView 488; Biotium, Inc., Hayward, CA). DNase I (DNAfree) and first-strand synthesis kit (RETROscript) were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA).

Human RPE Cell Culture

Human RPE cells were isolated from donor eyes by enzymatic digestion as previously described.24,25 The protocol adhered to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki for the use of human tissue in research. In all experiments, parallel assays were performed on RPE cells between passages 3 and 6. RPE cells were seeded at the same time and density from the same parent cultures, then grown in phenol red-free complete DMEM/F12 for at least 4 days until 85% to 100% confluence. RPE cells were placed in serum-free media overnight before treatments.

Detection of Caspase-3 Activation

Caspase-3 activation was measured by caspase-3 substrate (NucView 488; Biotium), as described previously.26 Fluorescence intensity of activated caspase-3 was measured by ImageJ software (developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html).

Hoechst Fluorescence Staining

Nuclear staining was performed as a second marker of RPE apoptosis.26 The numbers of stained RPE cells that exhibited apoptotic nuclear condensation and fragmentation were scored as apoptotic. RPE cells from at least 10 high-power microscopic fields from each group of cultures from each of three donors were counted and averaged. Data were normalized to the mean of control RPE cultures.

Double Staining with Caspase-3 Substrate and Hoechst

At the end of control and experimental incubations, RPE cells were successively stained with caspase-3 substrate (NucView 488) for 30 minutes and Hoechst 33342 for 10 minutes at room temperature.26 The caspase-3 substrate is cleaved by activated caspase-3 to release a dye that stains the cell nuclei green, whereas Hoechst 33342 stains the cell nuclei of healthy cells faintly blue and those of the apoptotic cells bluish-white.

Cell Death Detection ELISA

RPE apoptosis was also evaluated by DNA fragmentation, as measured by an ELISA kit (Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to procedures outlined by the manufacturer.

Cell-Based Fluorometric Ca2+ Assay

Intracellular Ca2+ levels were quantitatively determined by cell-based fluorometric Ca2+ assay using Indo-1-AM. RPE cells grown on 96-well culture plates were incubated with Indo-1-AM (5 μM) for 1 hour at 37°C in the dark, after which RPE cells were washed thoroughly, and control medium (HBSS/HEPES), ATP, or BzATP was added to the RPE cells. Indo-1 was excited at 355 nm, and the fluorescence emission from Indo-1 was measured at 405 nm and 485 nm with a fluorometer (FlexStation Scanning Fluorometer; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Fluorescence data were collected at 5-second intervals throughout the course of each experiment. Data are expressed as Indo-1 fluorescence ratios (F405/F485), which are used as a direct index of intracellular Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca 2+]i).

Ratiometric Calcium Imaging

Intracellular Ca2+ levels were also determined using fluorescence microscopy. RPE cells grown on 35-mm glass-bottom culture dishes were labeled as described and then mounted on the stage of an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon). Cells were excited at 355 nm, and fluorescence images were collected simultaneously at the dual-emission wavelengths (405 nm and 485 nm) using an imaging apparatus (Dual-View; Optical Insights, Suwanee, GA) and imaging software (MetaFluor Ratio Imaging Software; Universal Imaging Corporation, West Chester, PA). Analysis was carried out using the MetaFluor Analyst software (Universal Imaging Corporation, PA). The fluorescence intensity ratio (F405/F485) was used as a direct index of [Ca2+]i.

Total RNA Isolation

Total RNA was isolated from cultured human RPE cells using a RNA isolation reagent (Trizol; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration of total RNA was measured by ultraviolet spectrophotometry.

RT-PCR Analysis

RT-PCR was used to detect P2X7 mRNA, as described previously.27 PCR was performed with P2X7-specific primers with the forward primer sequence 5′-GAACCAGCAGCTACTAGGGAGAAG-3′ and the reverse primer sequence 5′-TGGGCAGGTTGGCAAAGTCAGC-3′.28 The housekeeping gene, hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 (HPRT1), served as a control. The forward primer for HPRT1 was 5′-ACCGTGTGTTAGAAAAGTAAGAAG-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-AGGGAACTGCTGACAAAGATTC-3′.29 The PCR products were generated by adding Taq DNA polymerase and cycled 40 times for P2X7 or HPRT1 (1 minute at 94°C, 0.5 minute at 64°C, 0.5 minute at 72°C), followed by a 7-minute extension at 72°C. The RT-PCR products were separated by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Confocal Microscopy

Human RPE cells were plated onto 8-well chamber slides and grown for at least 4 days, rinsed twice in PBS, and fixed for 15 minutes in 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were then rinsed and permeabilized for 5 minutes at room temperature in 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS. Cells were blocked in 6% BSA/10% normal goat serum in PBS for 1 hour and incubated with 8 μg/mL rabbit polyclonal anti-P2X7 antibody diluted in 1% BSA in PBS overnight at 4°C. The specificity of the anti-P2X7 antibody was confirmed by omitting the primary antibody. The cells were then incubated with 10 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-rabbit IgG diluted in 1% BSA in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature. Finally, the cells were washed, mounted in a mounting medium with DAPI (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories), and viewed with confocal microscope (TCS SP5; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Digital images were collected.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD and evaluated by Student's unpaired t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a Student-Newman-Keul's post hoc test. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

ATP and BzATP Induce RPE Apoptosis

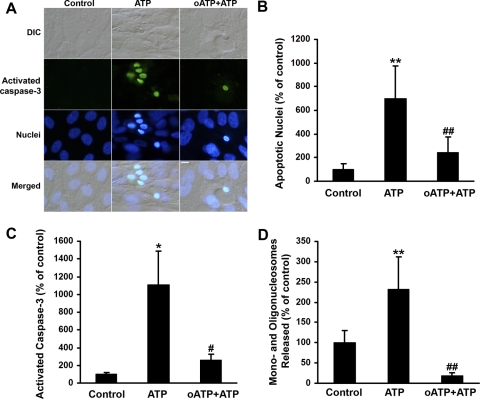

We assessed whether ATP increases RPE apoptosis. We used three apoptotic markers—activated caspase-3, nuclear condensation, and DNA fragmentation—to evaluate the effects of extracellular ATP on the multiple biochemical processes accompanying RPE apoptosis. Figure 1A shows images of RPE cells treated with ATP in the presence or absence of oATP, a P2X7 antagonist, for 6 hours. ATP induced caspase-3 activation and nuclear condensation, both of which were blocked by oATP. The percentages of RPE cells with apoptotic nuclei, as judged by Hoechst 33342 staining (Fig. 1B; P < 0.001), and of RPE cells with activated caspase-3 (Fig. 1C; P < 0.05) in ATP-treated RPE cells were statistically greater than those of control RPE cell cultures. The P2X7 antagonist, oATP, significantly reduced the percentages of RPE cells with apoptotic nuclei (Fig. 1B; P < 0.001) and activated caspase-3 (Fig. 1C; P < 0.05). At 24 hours, ATP significantly increased DNA fragmentation, as measured by cell death detection ELISA; this increase was completely blocked by oATP (Fig. 1D; P < 0.001). Each set of experiments was repeated on RPE cells isolated from three donors.

Figure 1.

ATP induces apoptosis in human RPE cells. (A) RPE cells were preincubated with or without oxidized ATP (oATP; 300 μM) and then exposed to 100 μM ATP with or without oATP for 6 hours. The number of cells with activated caspase-3 and the number of apoptotic RPE cells were determined by double labeling with caspase-3 substrate and Hoechst 33342. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) RPE cells were treated and stained by Hoechst 33342 as described in (A), and apoptotic RPE nuclei were determined. (C) RPE cells were treated and stained by caspase-3 substrate as described in (A), and activated caspase 3-positive RPE cells were determined. (D) RPE cells were treated as described in (A) for 24 hours. DNA fragmentation or released mononucleosomes and oligonucleosomes were measured by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 compared with control. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01, compared with ATP alone.

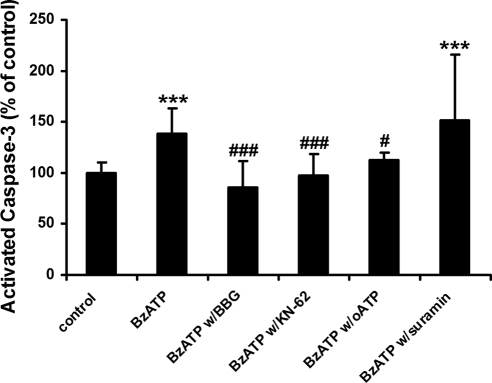

We next tested the effects of BzATP on RPE apoptosis. BzATP is a synthetic, selective P2X7 receptor agonist and is widely used in other systems.30–32 As shown in Figure 2, BzATP significantly increased RPE apoptosis, which was completely blocked or significantly inhibited by the P2X7 antagonists BBG (P < 0.001), KN-62 (P < 0.001), and oATP (P < 0.05), whereas suramin had no effect on BzATP-induced RPE apoptosis (P > 0.05), suggesting the involvement of P2X7 receptors in ATP- and BzATP-induced RPE apoptosis.

Figure 2.

BzATP induces apoptosis in human RPE cells. RPE cells were treated with 1 mM benzoylbenzoyl adenosine triphosphate (BzATP) in the presence or in the absence of P2 receptor antagonists, brilliant blue G (BBG), KN-62, oxidized ATP (oATP), or suramin for 24 hours and then were stained by caspase-3 substrate. Activated caspase-3 fluorescence intensity was measured. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 compared with control. #P < 0.05 and ###P < 0.001 compared with BzATP alone.

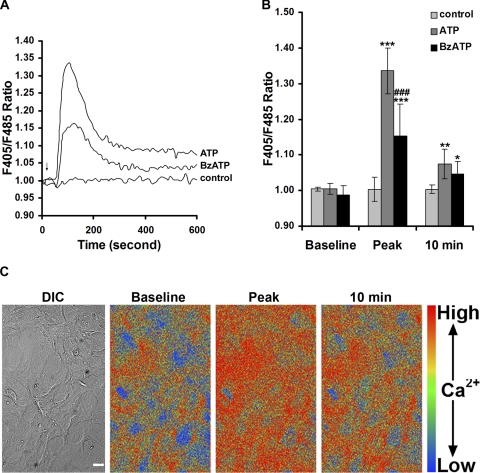

ATP and BzATP Increase RPE Intracellular Ca2+ Level

To assess the level of P2X7 receptor activity, we monitored [Ca2+]i using two different methods: a cell-based fluorometric Ca2+ assay and a Ca2+ imaging technique. As shown in Figure 3A, 100 μM ATP induced an increase in [Ca2+]i. The transient rise declined to a level that remained higher than the baseline or control [Ca 2+]i. Stimulation with 100 μM BzATP also produced an increase in [Ca 2+]i, but the BzATP-induced signal was lower than that caused by equimolar ATP (Figs. 3A, 3B). The ATP-induced Ca2+ peak or sustained Ca2+ level at 10 minutes was significantly higher than the control level and the baseline Ca2+ reading (Fig. 3B; P < 0.001 or P < 0.01). The BzATP-induced Ca2+ peak (Fig. 3B; P < 0.001) and sustained Ca2+ level (Fig. 3B; P < 0.05) were significantly higher than baseline and control Ca2+ levels. Using ratiometric calcium imaging, we confirmed that ATP-induced Ca2+ peak or Ca2+ level at 10 minutes is significantly greater than baseline [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3C). This Ca2+ imaging result is representative of five independent experiments.

Figure 3.

ATP and BzATP induce intracellular Ca2+ increase in human RPE cells. (A) Temporal plot of F405/F485 ratio changes recorded from Indo-1-AM–labeled RPE cells before and after 100 μM ATP or 100 μM BzATP application. Shown are the mean traces of six to nine traces for each condition from RPE cells derived from three different donors. Arrow: time when ATP, BzATP, or control medium (HBSS/HEPES) was added to the RPE cell cultures. (B) Summary of baseline Ca2+ (before ATP application), Ca2+ peak, and Ca2+ at 10 minutes in RPE cells derived from three different donors. Ca2+ concentrations were indicated by F405/F485 ratios. Data represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, compared with its own baseline or control. ###P < 0.001 compared with ATP alone. (C) Differential interference contrast (DIC) image and pseudocolor ratio (F405/F485) images of a representative field of Indo-1-AM–labeled RPE cells taken before and after ATP application. Scale bar, 20 μm.

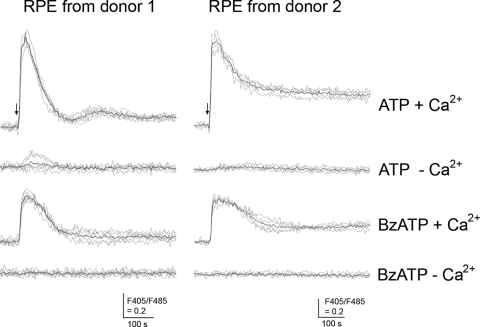

Both ATP and BzATP Trigger Extracellular Ca2+ Influx

We then asked whether the ATP- and BzATP-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ were caused by the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, influx from the extracellular environment, or both. To test this, additional experiments were performed in the presence or absence of extracellular Ca2+. In the presence of extracellular Ca2+, ATP or BzATP triggered a fast and sustained [Ca2+]i increase (Fig. 4). In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, ATP induced a much smaller [Ca2+]i increase in some traces (Fig. 4; RPE cells from donor 1) or no increase at all in other traces (Fig. 4; RPE cells from donors 1 and 2), suggesting that the observed ATP-induced [Ca2+]i was caused mainly by extracellular Ca2+ influx. In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, the BzATP-induced increase in [Ca2+]i was completely blocked in all traces, indicating BzATP-induced [Ca2+]i is only from extracellular Ca2+. In addition to the experiments shown in Figure 4, similar results were obtained from five additional independent experiments.

Figure 4.

ATP and BzATP trigger extracellular Ca2+ influx in human RPE cells. Human RPE cells (1 × 104) were plated onto a 96-well plate, cultured, and labeled with Indo-1-AM. After washes, the RPE cells were stimulated with 100 μM ATP or 100 μM BzATP in the presence (+Ca2+) or absence (−Ca2+) of extracellular Ca2+. The responses were measured using a fluorometer. Gray line: individual traces. Black line: mean trace of individual traces in each condition. Arrow: time when ATP or BzATP was added to the RPE cell cultures. Similar results were obtained from five additional independent experiments.

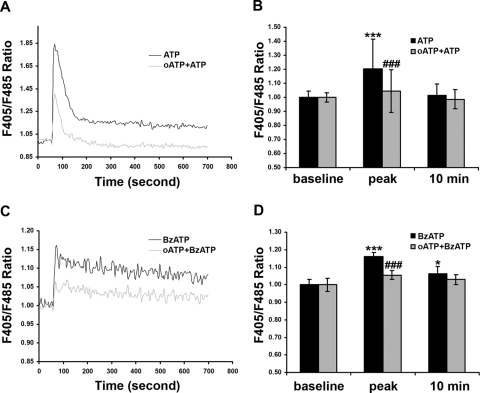

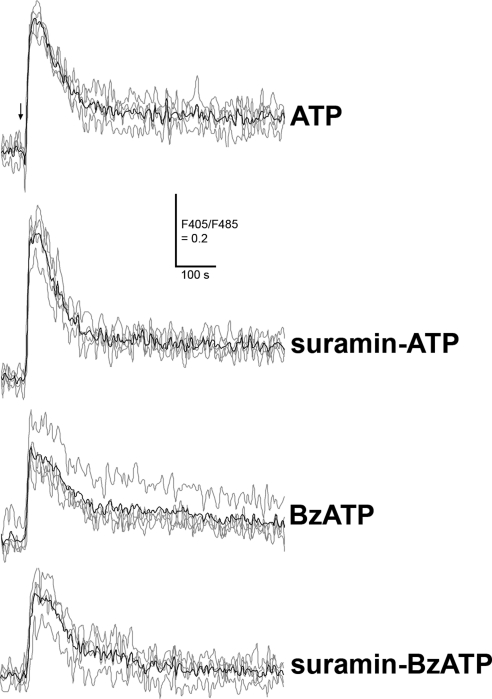

P2 Receptor Antagonists Affect ATP- or BzATP-Induced Ca2+ Level

We next asked whether P2 receptor antagonists block the induced Ca2+ rise. To this end, we preincubated RPE cells with oATP (300 μM), an irreversible inhibitor of the P2X7 receptors,33,34 or with suramin (50 μM), which was reported to inhibit the P2X1, P2X2, P2X3, P2X5, P2Y1, and P2Y2 receptors at similar concentrations,9,31,35 followed by application of ATP or BzATP. As shown in Figure 5, pretreatment of human RPE cells with oATP dramatically reduced the ATP- and BzATP-induced Ca2+ peak (P < 0.001), abolished ATP-induced sustained Ca2+ levels, and inhibited BzATP-induced sustained Ca2+ levels. In contrast, suramin did not inhibit the Ca2+ rise evoked by ATP or BzATP (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Effects of oxidized ATP on ATP- or BzATP-induced Ca2+ in human RPE cells. RPE cells were treated with or without P2X7 receptor antagonist or oxidized ATP (oATP; 300 μM) and then were exposed to 100 μM ATP (A, B) or BzATP (C, D). Histograms show the effects of oATP on the ATP- or BzATP-induced Ca2+ peak and the Ca2+ at 10 minutes. Data represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001, compared with baseline. ###P < 0.001 compared with ATP or BzATP alone.

Figure 6.

Effects of suramin on ATP- or BzATP-induced Ca2+ in human RPE cells. The RPE cells were pretreated with or without P2 receptor antagonist, suramin (50 μM), and then exposed to 100 μM ATP or BzATP in the presence (suramin-ATP or suramin-BzATP) or in the absence (ATP or BzATP) of suramin. The responses were measured using a fluorometer. Gray line: individual traces. Black line: mean trace of individual traces in each condition. Arrow: time when ATP or BzATP was added to the RPE cell cultures. Similar results were obtained from RPE cells derived from another donor.

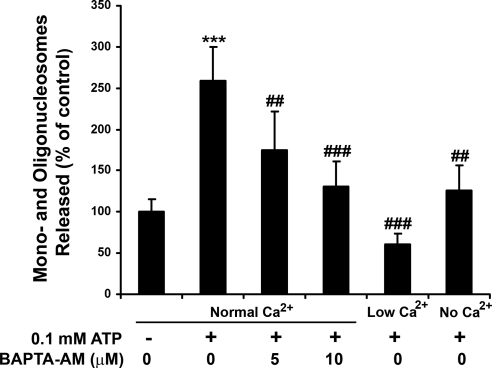

Buffering Intracellular Ca2+ or Decreasing Extracellular Ca2+ Inhibits ATP-Induced Apoptosis

BAPTA-AM is a cell-permeable free calcium chelator that is widely used to reduce intracellular Ca2+ levels in many systems, including RPE cells.9 If ATP-induced RPE apoptosis is dependent on an increase in [Ca2+]i, then pretreatment of RPE cells with BAPTA-AM would inhibit ATP-induced RPE apoptosis. As expected, BAPTA-AM pretreatment dose dependently inhibited ATP-induced RPE apoptosis, as measured by DNA fragmentation (Fig. 7; P < 0.01 and P < 0.001 for 5 μM and 10 μM BAPTA-AM, respectively). If the extracellular Ca2+ influx contributes to the ATP-induced rise in [Ca2+]i, then removing extracellular Ca2+ or reducing extracellular Ca2+ would be expected to block ATP-induced RPE apoptosis. As shown in Figure 7, removing extracellular Ca2+ (P < 0.01) or reducing extracellular Ca2+ (P < 0.001) from normal (1.8 mM) to low (0.3 mM) concentrations significantly inhibited or blocked ATP-induced apoptosis. These results were obtained from RPE cells derived from three different donors.

Figure 7.

Effects of BAPTA-AM and decreasing extracellular Ca2+ on ATP-induced apoptosis in human RPE cells. The RPE cells were pretreated with or without a cell-permeable intracellular Ca2+ chelator, BAPTA-AM (5 μM, 10 μM) for 30 minutes and then were exposed to 100 μM ATP for 24 hours in the absence and presence of BAPTA-AM in normal extracellular Ca2+ (1.8 mM). RPE cells were also exposed to 100 μM ATP for 24 hours in low extracellular Ca2+ (0.3 mM) or in the nominal absence of extracellular Ca2+. DNA fragmentation or released mononucleosomes and oligonucleosomes were measured by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 compared with control (unstimulated cells in normal extracellular Ca2+). ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 compared with ATP-stimulated cells in normal extracellular Ca2+.

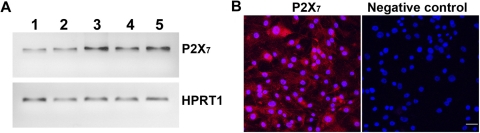

RPE Expresses P2X7 receptor

Our data suggest that functionally active P2X7 receptors are expressed by human RPE cells. To obtain molecular evidence for this, we performed RT-PCR experiments and confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. Figure 8A shows the results of RT-PCR of RNA extracted from native human RPE cells, cultured human RPE cells derived from three donors, and ARPE-19 cells. RT-PCR of all RPE cells generated single bands with the expected size of 476 bp, demonstrating the presence of P2X7 receptor mRNA in human RPE cells. To demonstrate that this message yielded P2X7 receptor protein, confocal immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. As shown in Figure 8B, P2X7 receptor protein expression was confirmed.

Figure 8.

P2X7 receptor expression in human RPE cells. (A) RT-PCR analysis. Total RNAs isolated from native human RPE (lane 1), cultured human RPE cells derived from three donors (lanes 2–4), and ARPE-19 cells (lane 5) were treated with DNase I and reverse transcribed. PCR was performed using a primer set specific for P2X7 receptor or HPRT1, which served as an endogenous control. (B) Immunofluorescence labeling of P2X7 in human RPE cells. Immunofluorescence labeling omitting primary antibody serves as a negative control. Scale bar, 40 μm.

Discussion

This study provides the first evidence that P2X7 receptors are expressed in native and cultured human RPE cells and that activation of P2X receptors induces both Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis. Extracellular ATP can induce apoptosis through the ligation of P2X and P2Y receptors.36 The P2X receptors, particularly P2X7 receptor, have been shown to play a more important role in the induction of apoptosis than the P2Y receptors.37,38

P2Y Receptors in the RPE

P2Y receptors have been implicated in RPE function, and P2Y mRNA and protein have been identified in cultured human RPE cells, rabbit, rat, and monkey RPE cells.12,16–18, 39–41 Activation of P2Y2 receptors increases [Ca2+]i, RPE fluid transport, and retinal reattachment in rat and rabbit models of retinal detachment.9,11,12,14,15,42 In addition to P2Y2 receptors, P2Y1 and P2Y6 receptors were reported to regulate Ca2+ levels in cultured human RPE cells,17 and stimulation of ARPE-19 cells with extracellular nucleotides induced IL-8 gene expression and protein secretion, possibly through P2Y2 and P2Y6 receptors.18 Among the three functional receptors (P2Y1, P2Y2, and P2Y6) identified in human RPE, P2Y2 receptor can be activated by ATP. Suramin is known to block P2Y2 receptors in different cell types, including RPE cells.9,31,35 However, we found that pretreatment of RPE cells with suramin did not significantly inhibit the ATP-induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels (Fig. 6). P2X receptors are ATP-gated ion channels that are permeable to Ca2+, and the influx of extracellular Ca2+ contributes to the initial Ca2+ peak when P2X receptors are activated.20,43 P2Y receptors are G-protein–coupled receptors, and Ca2+ released from intracellular stores contributes to the initial Ca2+ increase when P2Y receptors are activated.17 Therefore, removal of extracellular Ca2+ can help determine whether ATP acts on P2X receptors, P2Y receptors, or both. We show here that, in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, ATP-induced Ca2+ responses were almost completely blocked (Fig. 4), suggesting that P2X receptors rather than P2Y receptors contribute to the ATP-induced Ca2+ responses in human RPE cells under our experimental conditions.

Harada et al.37 reported that stimulation of P2Y2 or P2Y4 receptors, or both, induced cell proliferation, whereas stimulation of P2X7 receptors induced cell apoptosis in glomerular mesangial cells. Based on this, we suggest that the relative expression of P2X and P2Y receptors by RPE cells could determine cell fate: proliferation or apoptosis in response to extracellular ATP. Furthermore, local concentrations of extracellular ATP are important in determining cell death. We observed that 100 μM ATP increased human RPE apoptosis as judged by three different approaches (Fig. 1). Consistent with our results, Sugiyama et al.32 showed that ATP at 100 μm, but not 30 μM, significantly increased rat retinal neuron death. Thus, ATP may activate P2Y receptors and P2X1–6 receptors at lower concentrations (<100 μM) and P2X7 receptors at higher concentrations (≥100 μM) in RPE cells.

P2X Receptors in the RPE

P2X receptors have two transmembrane domains and can form trimeric channels by polymerization of their subunits homomerically or heteromerically. Functional P2X receptors include six homomeric channels and seven heteromeric channels.35,44 The ability of P2X receptors to act as direct conduits for Ca2+ influx or indirect activators of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels underlies their important roles in Ca2+-based signaling responses.44

ATP was found to be released by RPE cells10,16,45–47 and by neural retina48,49 and to be capable of acting on P2X receptors in the RPE cells in an autocrine or a paracrine manner. The study by Sullivan et al.12 supports the presence of functional P2X receptors in the RPE cells. Sullivan et al.12 applied 100 μM ATP to cultured human RPE cells and found that ATP induced an initial Ca2+ peak and sustained rise in [Ca 2+]i. In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, the ATP-induced Ca2+ peak was reduced, and the sustained [Ca 2+]i increase was abolished.12 Ryan et al.13 presented evidence that cultured rat RPE cells exhibited functional P2Y and P2X receptors and showed that ATP-induced increases in [Ca2+]i did not depend on extracellular Ca2+ influx. The discrepancies between studies could be explained by cell strains or cell lines, cell sensitivity, cell proliferation state, ATP concentration, and exposure time to ATP. Dutot et al.19 showed that YO-PRO-1 dye uptake was increased in ATP- and BzATP-stimulated ARPE-19 cells and P2X7 receptor protein was detected in ARPE-19 cells. In this study, we detected not only P2X7 receptor protein but also P2X7 receptor mRNA in human RPE cells. Our functional data indicate that P2X receptors contribute to both ATP- and BzATP-induced Ca2+ increases and apoptosis in human RPE cells because the BzATP- and ATP-triggered Ca2+ responses were abolished or largely blocked after the removal of extracellular Ca2+. Our findings that the reduction or removal of extracellular Ca2+ or the buffering of intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA-AM significantly inhibited or blocked ATP-induced apoptosis suggest that RPE apoptosis is triggered by the ATP-induced rise in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 4). However, ATP-induced apoptosis seems to be lower at low extracellular Ca2+ than in the nominal absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 7), indicating that some extracellular Ca2+ may be required for RPE cell survival. Our pharmacologic data further support the notion that the P2X7 receptors contribute to the responses of RPE cells to ATP because ATP-induced Ca2+ influx and apoptosis were blocked by oATP, and the selective P2X7 agonist BzATP induced a Ca2+ influx that was significantly inhibited by oATP. Furthermore, BzATP-induced RPE apoptosis was blocked or significantly inhibited by P2X7 receptor antagonists BBG, KN-62, and oATP. However, Ca2+ influx evoked by ATP was higher than that by equimolar BzATP, indicating that in addition to P2X7, other P2X receptors might be present because BzATP is known as a much better P2X7 agonist than ATP.43 Both ATP and BzATP-triggered Ca2+ influx were insensitive to suramin, suggesting that P2X4 and P2X7 receptors may contribute to the induced Ca2+ influx given that P2X1, P2X2, P2X3, and P2X5 receptors, but not P2X4 and P2X7 receptors, were found to be sensitive to suramin,35,50 and the P2X6 receptor cannot form a homomeric channel by itself.35,44 Further studies are needed to test whether P2X4 homomeric channels, P2X4/P2X7 heteromeric channels, or both are expressed in the RPE. This is important because P2X4 and P2X7 receptors are coexpressed in immune cells and epithelial cells, and heteromerization can change both the functional and pharmacological properties of P2X receptors.51,52 Future studies to determine whether knockdown of P2X7 reduces ATP-induced RPE Ca2+ responses and apoptosis may further support our findings. Taken together, our results support the idea that P2X, especially P2X7, receptors mediate ATP-induced Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis in human RPE.

Pathophysiological Implications

P2X7 receptor requires a relatively high ATP concentration to be activated, with a 50% effective concentration (EC50) of approximately 0.1 to 1 mM compared with other P2X receptors with EC50 of approximately 1 to 10 μM.35,53 Given that extracellular ATP is normally in the low micromolar range, the activation of P2X7 may be not favored under physiological conditions.

We show here that activation of the P2X receptors, especially the P2X7 receptor, increases both fast and sustained Ca2+ levels within RPE cells and induces RPE apoptosis. We have demonstrated previously that proinflammatory cytokines induce reactive oxygen species in human RPE cells25 and that oxidative stress increases mononuclear phagocyte-induced mouse RPE apoptosis, especially when mononuclear phagocytes were activated by IFN-γ and superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) expression was reduced by partial knockout of the SOD2 gene.26 Proinflammatory cytokines and ATP can be released at sites of inflammation and can upregulate P2X7 receptor expression in human monocytes, astrocytes, and epithelial cells.34,54–57 Thus, it is possible that proinflammatory cytokines and ATP released during pathologic conditions may increase P2X7 expression in the RPE and thus increase the vulnerability of RPE cells to extracellular ATP-induced apoptosis.

P2X7 receptor is also involved in inflammation and oxidative stress in many cell types.20,58–60 Cell death, inflammation, and oxidative stress are implicated in AMD.22,23,61,62 Therefore, defining the role of P2X7 receptor in the RPE under physiological and pathophysiological conditions could have important implications for the pathogenesis of AMD. Selectively interfering with P2X receptor expression and activation could generate new preventions and therapies for AMD.

In summary, the present study provides the first evidence of functional P2X7 receptor expressed in human RPE and demonstrates that activation of P2X receptors, especially P2X7 receptor, induces Ca2+ signaling and RPE apoptosis. It is tempting to speculate that the P2X7 receptor identified here could impact RPE function physiologically and pathologically.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Donald G. Puro for his constructive and helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY09441 (VME), EY08850 (BAH), CA74120 (HRP), and P30EY07003 (Core). VME is a recipient of a Lew R. Wasserman Merit Award from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Disclosure: D. Yang, None; S.G. Elner, None; A.J. Clark, None; B.A. Hughes, None; H.R. Petty, None; V.M. Elner, None

References

- 1. Schwiebert EM, Zsembery A. Extracellular ATP as a signaling molecule for epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1615:7–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang X, Arcuino G, Takano T, et al. P2X7 receptor inhibition improves recovery after spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2004;10:821–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G. Purinoceptors: are there families of P2X and P2Y purinoceptors? Pharmacol Ther. 1994;64:445–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Surprenant A, Rassendren F, Kawashima E, North RA, Buell G. The cytolytic P2Z receptor for extracellular ATP identified as a P2X receptor (P2X7). Science. 1996;272:735–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. North RA, Barnard EA. Nucleotide receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:346–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rassendren F, Buell GN, Virginio C, Collo G, North RA, Surprenant A. The permeabilizing ATP receptor, P2X7: cloning and expression of a human cDNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5482–5486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. MacKenzie AB, Surprenant A, North RA. Functional and molecular diversity of purinergic ion channel receptors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:716–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garcia-Marcos M, Pochet S, Marino A, Dehaye JP. P2X7 and phospholipid signalling: the search of the “missing link” in epithelial cells. Cell Signal. 2006;18:2098–2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peterson WM, Meggyesy C, Yu K, Miller SS. Extracellular ATP activates calcium signaling, ion, and fluid transport in retinal pigment epithelium. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2324–2337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pearson RA, Dale N, Llaudet E, Mobbs P. ATP released via gap junction hemichannels from the pigment epithelium regulates neural retinal progenitor proliferation. Neuron. 2005;46:731–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stalmans P, Himpens B. Confocal imaging of Ca2+ signaling in cultured rat retinal pigment epithelial cells during mechanical and pharmacologic stimulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:176–187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sullivan DM, Erb L, Anglade E, Weisman GA, Turner JT, Csaky KG. Identification and characterization of P2Y2 nucleotide receptors in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Neurosci Res. 1997;49:43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ryan JS, Baldridge WH, Kelly MEM. Purinergic regulation of cation conductances and intracellular Ca2+ in cultured rat retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Physiol. 1999;520:745–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maminishkis A, Jalickee S, Blaug SA, et al. The P2Y2 receptor agonist INS37217 stimulates RPE fluid transport in vitro and retinal reattachment in rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3555–3566 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takahashi J, Hikichi T, Mori F, Kawahara A, Yoshida A, Peterson WM. Effect of nucleotide P2Y2 receptor agonists on outward active transport of fluorescein across normal blood-retina barrier in rabbit. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:103–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reigada D, Lu W, Zhang X, et al. Degradation of extracellular ATP by the retinal pigment epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C617–C624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tovell VE, Sanderson J. Distinct P2Y receptor subtypes regulate calcium signaling in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:350–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Relvas LJ, Bouffioux C, Marcet B, et al. Extracellular nucleotides and interleukin-8 production by ARPE cells: potential role of danger signals in blood-retinal barrier activation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1241–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dutot M, Liang H, Pauloin T, et al. Effects of toxic cellular stresses and divalent cations on the human P2X7 cell death receptor. Mol Vis. 2008;14:889–897 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khakh BS, North RA. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature. 2006;442:527–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Turner CM, Elliott JI, Tam FW. P2 receptors in renal pathophysiology. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5:513–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zarbin MA. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:598–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gehrs KM, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Hageman GS. Age-related macular degeneration—emerging pathogenetic and therapeutic concepts. Ann Med. 2006;38:450–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Elner SG, Strieter RM, Elner VM, Rollins BJ, Del Monte MA, Kunkel SL. Monocyte chemotactic protein gene expression by cytokine-treated human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Lab Invest. 1991;64:819–825 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang D, Elner SG, Bian ZM, Till GO, Petty HR, Elner VM. Pro-inflammatory cytokines increase reactive oxygen species through mitochondria and NADPH oxidase in cultured RPE cells. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:462–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang D, Elner SG, Lin LR, Reddy VN, Petty HR, Elner VM. Association of superoxide anions with retinal pigment epithelial cell apoptosis induced by mononuclear phagocytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4998–5005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang D, Swaminathan A, Zhang X, Hughes BA. Expression of Kir7.1 and a novel Kir7.1 splice variant in native human retinal pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86:81–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cheewatrakoolpong B, Gilchrest H, Anthes JC, Greenfeder S. Identification and characterization of splice variants of the human P2X7 ATP channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, et al. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7227–7232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sugiyama T, Kawamura H, Yamanishi S, Kobayashi M, Katsumura K, Puro DG. Regulation of P2X7-induced pore formation and cell death in pericyte-containing retinal microvessels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C568–C576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang X, Zhang M, Laties AM, Mitchell CH. Stimulation of P2X7 receptors elevates Ca2+ and kills retinal ganglion cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2183–2191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sugiyama T, Oku H, Shibata M, Fukuhara M, Yoshida H, Ikeda T. Involvement of P2X7 receptors in the hypoxia-induced death of rat retinal neurons. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3236–3243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murgia M, Hanau S, Pizzo P, Rippa M, Di Virgilio F. Oxidized ATP: an irreversible inhibitor of the macrophage purinergic P2Z receptor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8199–8203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Humphreys BD, Dubyak GR. Induction of the P2z/P2X7 nucleotide receptor and associated phospholipase D activity by lipopolysaccharide and IFN-gamma in the human THP-1 monocytic cell line. J Immunol. 1996;157:5627–5637 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. North RA, Surprenant A. Pharmacology of cloned P2X receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:563–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Coutinho-Silva R, Stahl L, Cheung KK, et al. P2X and P2Y purinergic receptors on human intestinal epithelial carcinoma cells: effects of extracellular nucleotides on apoptosis and cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1024–G1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harada H, Chan CM, Loesch A, Unwin R, Burnstock G. Induction of proliferation and apoptotic cell death via P2Y and P2X receptors, respectively, in rat glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2000;57:949–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sylte MJ, Kuckleburg CJ, Inzana TJ, Bertics PJ, Czuprynski CJ. Stimulation of P2X receptors enhances lipooligosaccharide-mediated apoptosis of endothelial cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:958–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cowlen MS, Zhang VZ, Warnock L, Moyer CF, Peterson WM, Yerxa BR. Localization of ocular P2Y2 receptor gene expression by in situ hybridization. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pintor J, Sánchez-Nogueiro J, Irazu M, Mediero A, Peláez T, Peral A. Immunolocalisation of P2Y receptors in the rat eye. Purinergic Signal. 2004;1:83–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fries JE, Wheeler-Schilling TH, Guenther E, Kohler K. Expression of P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptor subtypes in the rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3410–3417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Meyer CH, Hotta K, Peterson WM, Toth CA, Jaffe GJ. Effect of INS37217, a P2Y2 receptor agonist, on experimental retinal detachment and electroretinogram in adult rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3567–3574 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dubyak GR. Go it alone no more—P2X7 joins the society of heteromeric ATP-gated receptor channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1402–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mitchell CH. Release of ATP by a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line: potential for autocrine stimulation through subretinal space. J Physiol. 2001;534:193–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eldred JA, Sanderson J, Wormstone M, Reddan JR, Duncan G. Stress-induced ATP release from and growth modulation of human lens and retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:1213–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reigada D, Mitchell CH. Release of ATP from RPE cells involves both CFTR and vesicular transport. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C132–C140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Neal M, Cunningham J. Modulation by endogenous ATP of the light-evoked release of ACh from retinal cholinergic neurones. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:1085–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Newman EA. Glial cell inhibition of neurons by release of ATP. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1659–1666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jones CA, Chessell IP, Simon J, et al. Functional characterization of the P2X4 receptor orthologues. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:388–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ma W, Korngreen A, Weil S, et al. Pore properties and pharmacological features of the P2X receptor channel in airway ciliated cells. J Physiol. 2006;571:503–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Guo C, Masin M, Qureshi OS, Murrell-Lagnado RD. Evidence for functional P2X4/P2X7 heteromeric receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1447–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nihei OK, Savino W, Alves LA. Procedures to characterize and study P2Z/P2X7 purinoceptor: flow cytometry as a promising practical, reliable tool. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95:415–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Narcisse L, Scemes E, Zhao Y, Lee SC, Brosnan CF. The cytokine IL-1beta transiently enhances P2X7 receptor expression and function in human astrocytes. Glia. 2005;49:245–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Turner CM, Tam FW, Lai PC, et al. Increased expression of the pro-apoptotic ATP-sensitive P2X7 receptor in experimental and human glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:386–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Welter-Stahl L, da Silva CM, Schachter J, et al. Expression of purinergic receptors and modulation of P2X7 function by the inflammatory cytokine IFNgamma in human epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:1176–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Al-Shukaili A, Al-Kaabi J, Hassan B. A comparative study of interleukin-1beta production and P2X7 expression after ATP stimulation by peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from rheumatoid arthritis patients and normal healthy controls. Inflammation. 2008;31:84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Parvathenani LK, Tertyshnikova S, Greco CR, Roberts SB, Robertson B, Posmantur R. P2X7 mediates superoxide production in primary microglia and is up-regulated in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13309–13317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hewinson J, Mackenzie AB. P2X7 receptor-mediated reactive oxygen and nitrogen species formation: from receptor to generators. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1168–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hewinson J, Moore SF, Glover C, Watts AG, MacKenzie AB. A key role for redox signaling in rapid P2X7 receptor-induced IL-1 beta processing in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:8410–8420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gehrs KM, Jackson JR, Brown EN, Allikmets R, Hageman GS. Complement, age-related macular degeneration and a vision of the future. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:349–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Detrick B, Hooks JJ. Immune regulation in the retina. Immunol Res. 2010;47:153–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]