Abstract

Enterobacterial strains of Raoultella spp. display a penicillinase-related β-lactam resistance pattern suggesting the presence of a chromosomal bla gene. From whole-cell DNA of Raoultella planticola strain ATCC 33531T and Raoultella ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T, bla genes were cloned and expressed into Escherichia coli. Each gene encoded an Ambler class A β-lactamase, named PLA-1 and ORN-1 for R. planticola and R. ornithinolytica, respectively. These β-lactamases (291 amino acids), with the same pI value of 7.8, had a shared amino acid identity of 94%, 37 to 47% identity with the majority of the chromosome-encoded class A β-lactamases previously described for Enterobacteriaceae, and 66 to 69% identity with the two β-lactamases LEN-1 and SHV-1 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. However, the highest identity percentage (69 to 71%) was found with the plasmid-mediated β-lactamase TEM-1. PLA-1, which displayed very strong hydrolytic activity against penicillins, also displayed significant hydrolytic activity against cefepime and, to a lesser extent, against cefotaxime and aztreonam, but there was no hydrolytic activity against ceftazidime. Such a substrate profile suggests that the Raoultella β-lactamases PLA-1 and ORN-1 should be classified into the group 2be of the β-lactamase classification of K. Bush, G. A. Jacoby, and A. A. Medeiros (Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1211-1233, 1995). The highly homologous regions upstream of the blaPLA-1A and blaORN-1A genes comprised a nucleotide sequence identical to the −35 region and another one very close to the −10 region of the blaLEN-1 gene. From now on, as the bla gene sequences of the most frequent Raoultella and Klebsiella species are available, the bla gene amplification method can be used to differentiate these species from each other, which the biochemical tests currently carried out in the clinical laboratory are unable to do.

Klebsiella planticola and Klebsiella terrigena were identified in 1981, and Klebsiella ornithinolytica was identified in 1989 (2, 12, 32). The first two species were primarily associated with botanical and aquatic environments, whereas the third one, which was formerly known as ornithine-positive Klebsiella oxytoca, was first identified from clinical samples (2, 12, 32). The differentiation of these three species from the other Klebsiella species was based on biochemical reactions, growth temperatures, pigment production, G+C content, and DNA-DNA hybridization (2, 12, 32). However, these three species have recently been reclassified in a new genus, the Raoultella genus, on the basis of the 16S rDNA and rpoB gene sequence analysis of enteric bacteria (8, 19). In spite of this phylogenetic advance, the routine biochemical tests used in the clinical laboratory are not capable of distinguishing between Klebsiella spp., particularly K. oxytoca, and Raoutella spp. To demonstrate the involvement of Raoultella spp. in infectious diseases, the use of particular methods was required. Thus, by using particular biochemical tests and differential growth temperatures and, very recently, the ERIC-1R PCR method, it has been proved that Raoultella planticola and Raoultella ornithinolytica colonize or infect human beings and are also responsible for histamine fish poisoning (10, 14, 17, 23-26, 36). Clinical isolates of Klebsiella and Raoultella are easily confused, especially since the species of these genera display identical β-lactam resistance patterns. Indeed, the species are resistant to amino- and carboxy-penicillins but susceptible to these molecules when they are combined with clavulanate (34). Such a β-lactam resistance phenotype suggests that isolates of Raoultella species produce the same class A β-lactamases as isolates of Klebsiella species. However, we have previously observed that the supposed β-lactamases of the three species of Raoultella were unable to be amplified by the primers used to amplify the genes encoding the K. oxytoca β-lactamases (10). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to clone and characterize the β-lactamase content of R. planticola and R. ornithinolytica, which seem to be more frequently involved in human and animal infections than Raoultella terrigena (10, 14).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

R. planticola strains ATCC 33531T and BM85.01.092 (bioMérieux collection, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and R. ornithinolytica strains ATCC 31898T and BM85.01.101 (bioMérieux) were studied. The rifampin-resistant Escherichia coli strain J53-2 was used as recipient in mating experiments, whereas E. coli strain XL10-Gold (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and the streptomycin-resistant E. coli strain NM554 were used as recipients in cloning experiments. The high copy number phagemid pBK-CMV vector (Knr) (Stratagene) was used to clone the digested chromosomal fragments, whereas plasmid pPCR Script (Cmr) (Stratagene) and the low copy number plasmid pACYC184 vector (Tcr and Cmr) (BioLabs, Hichtin, United Kingdom) were used to clone PCR-amplified DNA fragments.

The blaTEM-1B gene controlled by the promoter P3 which has previously been cloned in the plasmid pACYC184 and expressed in E. coli NM554 (15) was used as a TEM-1-producing E. coli control strain in MIC experiments.

Mating assays and plasmid content analysis.

The direct transfer of amoxicillin resistance from Raoultella sp. strains to E. coli K-12 was attempted by liquid and solid mating assays, as previously described (11). Transconjugants were selected on Trypticase soy (TS) agar plates containing amoxicillin (50 μg/ml) and rifampin (150 μg/ml). Raoultella sp. strains were analyzed for their plasmid content according to the procedures of Birnboim and Doly (4) and of Kado and Liu (13).

Cloning experiments and analysis of recombinant plasmids.

Whole-cell DNA fragments of R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T and R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T were extracted as previously described (3). DNA was partially digested with the Sau3AI restriction enzyme (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France) and ligated into the BamHI-restricted and dephosphorylated vector pBK-CMV. The ligations were performed at 16°C for 18 h with a 1:2 insert/vector ratio and 1 U of T4 DNA ligase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The ligation products were electroporated (GenePulser; Bio-Rad, Ivry-sur-Seine, France) into electrocompetent E. coli NM554. E. coli NM554 cells harboring recombinant plasmids were selected on TS agar plates containing kanamycin (30 μg/ml) and amoxicillin (50 μg/ml). The recombinant plasmids were extracted with a Qiafilter Plasmid Midi kit (QIAGEN, Courtaboeuf, France) from 100-ml aliquots of overnight cultures grown at 37°C in Luria broth in the presence of amoxicillin (50 μg/ml) and kanamycin (30 μg/ml). A double-restriction digestion analysis allowed for precise mapping of recombinant plasmids by comparison with the molecular weight marker 1-kb ladder (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The recombinant pBK-CMV phagemid with the shortest insert was retained.

DNA sequencing and deduced protein sequence analysis.

The inserts of recombinant pBK-CMV phagemids were sequenced on both strands with the pBK-CMV T3 and T7 primers by using an ABI Prism Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit and an ABI Cycle Sequencer 3100 (Applied Biosystems, Villacoublay, France). Internal sequencing primers were constructed from the available DNA sequences to complete the sequence walk. The nucleotide sequences and the deduced protein sequences were analyzed by using the software available over the Internet at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.nbci.nlm.nih.gov) and the Infobiogen website (http://www.infobiogen.fr). Multiple-protein sequence alignments were carried out with the ClustalW program. Among the Ambler class A β-lactamases previously described, 14 chromosomal β-lactamases (names, bacterial species, and GenBank accession numbers as follows: SHV-1 and LEN-1 from Klebsiella pneumoniae, X98101 and X04515, respectively; KOXY [group OXY-1] from K. oxytoca, Z30177; RAHN-1 from Rahnella aquatilis, AF338038; Sed-1 from Citrobacter sedlakii, AF321608; CdiA from Citrobacter koseri [formerly diversus], X62610; CUM-A from Proteus vulgaris, X80128; HUG-A from Proteus penneri, AF324468; FONA-1 from Serratia fonticola, AJ251239; KLUC-1 from Kluyvera cryocrescens, AY026417; KLUA-1 from Kluyvera ascorbata, AJ272538; YENT from Yersinia enterocolitica, X57074; ERP-1 from Erwinia persicina, AY077733; and MAL-1 from Citrobacter koseri, AJ277209) and one plasmid-mediated β-lactamase (TEM-1; accession number AB070224) were compared with the β-lactamases identified in R. planticola ATCC 33531T and R. ornithinolytica ATCC 31898T, and the identity percentages were calculated with the Alignp program (http://www.infobiogen.fr).

PCR and amplified fragment cloning experiments.

Two pairs of primers specific for amplification and sequencing of the bla genes of R. planticola (VP1, 5′-ACT CTT TCA TAT ACT GAG-3′, and VP2, 5′-TTT TTA CGT CCG GGA GG-3′, located 186 bp upstream of the ATG codon and 55 bp downstream of the stop codon of the bla gene, respectively) and R. ornithinolytica (VO1, 5′-CAT ACC AGC CTG AAT GAA-3′, and VO2, 5′-GTT TTG TCC GGG GAT GTT-3′, located 208 bp upstream of the ATG codon and 44 bp downstream of the stop codon of the bla gene, respectively) were defined. In order to clone the fragments amplified from R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T and R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T into the pPCR Script vector and then into the pACYC184 vector, the 5′ end of an aliquot of these primers was extended with eight nucleotides, six of which correspond to the restriction site of the BamHI enzyme. The fragments generated with these extended primers were ligated into the pPCR Script plasmid as recommended by the manufacturer. The recombinant plasmids were transferred into E. coli XL10-Gold by using the heat shock procedure, and transformants were selected onto TS agar plates containing amoxicillin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml). Each recombinant plasmid was then purified, and 5 μg of the purified plasmid was restricted by enzyme BamHI (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in order to release the inserted fragment. This fragment was extracted from agarose gel by using a QIAEX II Gel Extraction kit (QIAGEN) and cloned by using the T4 DNA ligase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) into the dephosphorylated plasmid pACYC184 previously digested with BamHI. The ligation products were electroporated into electrocompetent E. coli NM554 cells, and transformants were selected on TS agar plates containing amoxicillin (50 μg/l) and chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml). The insertion of the ligated fragment in the opposite orientation of the promoter of the pACYC184 tetracycline resistance-encoding gene (meaning the bla gene under the control of its own promoter) was assessed by restriction analyses with enzymes BamHI and ClaI. The recombinant pACYC184 plasmids obtained from R. planticola and R. ornithinolytica were called pACpla1 and pACorn1, respectively.

β-Lactam susceptibility.

The β-lactam susceptibility of R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T, R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T, E. coli NM554, and the E. coli NM554 transformants was determined by the agar dilution method on Mueller-Hinton agar with a Steers multiple inoculator and 104 CFU per spot. The following antibiotics were tested: amoxicillin (GlaxoSmithKline, Marly-le-Roi, France), ticarcillin (GlaxoSmithKline), cefotaxime (Aventis, Paris, France), ceftazidime (GlaxoSmithKline), cefepime (Bristol-Myer Squibb, La Défense, France) and aztreonam (Sanofi Winthrop, Gentilly, France). Each of these molecules was tested alone and in the presence of 2 μg of clavulanate (GlaxoSmithKline) per ml, piperacillin (Wyeth Lederle, Oullins, France) alone, and in the presence of 4 μg each of tazobactam (Wyeth Lederle), cephalothin (Eli Lilly, Saint Cloud, France), cefuroxime (GlaxoSmithKline), cefoxitin (Panpharma, Fougeres, France), and imipenem (Merck Sharp & Dohme-Chibret, Paris, France) per ml. The results were interpreted according to the French Antibiogram Committee recommendations (1).

Preparation of crude extracts and isoelectrofocusing.

The pI values of the β-lactamases of R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T and R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T were determined from crude enzyme extracts as previously described (18) and compared with the pI value of known β-lactamases: TEM-1 (5.4), TEM-2 (5.6), SHV-3 (7.0), SHV-1 (7.6), and SHV-5 (8.2).

β-Lactamase purification and biochemical parameters.

Culture of E. coli NM554 (pBKpla1) was grown overnight at 37°C in 4 liters of TS broth containing amoxicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (30 μg/ml). The β-lactamase extract was obtained after sonication, as described previously (27). The extract was dialyzed overnight against 20 mM diethanolamine (pH 9) and then loaded onto a Q-Sepharose column preequilibrated with the same buffer. The β-lactamase was recovered in the flowthrough and then dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.5). This extract was then loaded onto the Q-Sepharose column preequilibrated with the same buffer, and the β-lactamase extract was eluted with a linear NaCl gradient (0 to 1 M). The fractions containing the highest β-lactamase activity were pooled and dialyzed overnight against 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7). Final concentration was obtained with a Centrisart 10-kDa exclusion device (Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany). The protein content was measured by a Bio-Rad DC protein assay. Specific activities of the crude extract and the purified enzyme were determined and compared as previously reported with 100 μM cephaloridine as substrate (28), and the purity of the enzyme was estimated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (33).

The purified β-lactamase PLA-1 was used for kinetic measurements performed at 30°C in 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0). The rates of hydrolysis were determined with an ULTROSPEC 2000 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) spectrophotometer. The wavelengths and absorption coefficients of β-lactams have been previously described (28). Km and kcat values were determined by analyzing the β-lactam hydrolysis under initial rate conditions by using the Eadie-Hoffstee linearization of the Michaelis-Menten equation.

Various concentrations of clavulanic acid, tazobactam, and sulbactam were preincubated with the enzyme for 3 min at 30°C before testing the rate of cephaloridine (100 μM) hydrolysis. The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of the drugs were determined as the concentrations at which 50% of the hydrolytic activity was inhibited.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The blaPLA-1A, blaPLA-2A, blaORN-1A, and blaORN-1B gene sequences have been registered in the GenBank database under the following accession numbers: AY302757, AY307385, AY307386, and AY307387, respectively.

RESULTS

Transfer of amoxicillin resistance and cloning of the bla genes of R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T and R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T into E. coli.

Plasmid DNA extraction failed to identify plasmids in Raoultella strains. The direct transfer of amoxicillin resistance from these strains to E. coli K-12 also failed, suggesting that the β-lactamase gene was located on the chromosome. Two amoxicillin-resistant E. coli NM554 recombinant clones were obtained from the Sau3AI-restricted chromosomal DNA of R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T, and two were also obtained from the Sau3AI-restricted chromosomal DNA of R. ornithinolytica ATCC 31898T. In each case, only the recombinant pBK-CMV phagemid that had the shortest insert was retained: pBKpla1 with an insert of 1.5 kb from R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T and pBKorn1 with an insert of 1.5 kb from R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T.

Sequence analysis of the bla genes and surrounding sequences from R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T and R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T.

Open reading frames (ORFs) of 876 bp were identified in pBKpla1 and pBKorn1 obtained from R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T and R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T, respectively. The two ORFs displayed a high degree of homology (94.5%) and a G+C content of 60.7% for R. planticola and 61.5% for R. ornithinolytica. Upstream and downstream of these ORFs, there were 260 and 347 bp, respectively, from the R. planticola strain and 278 and 348 bp, respectively, from the R. ornithinolytica strain. The two upstream sequences displayed a high degree of homology to each other (96.1%) and lower G+C values than those observed for the coding regions: 39.6 and 37.7% for the R. planticola and R. ornithinolytica strains, respectively. The two downstream sequences had 90.9% homology to each other and a G+C content of 51.9 and 53.1% for the R. planticola and R. ornithinolytica strains, respectively.

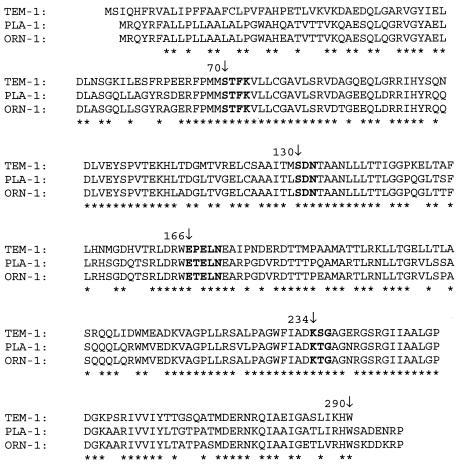

Within the deduced protein of these two ORFs (291 amino acids), three structural elements known to be involved in the catalytic mechanism and in substrate binding of class A β-lactamases, namely 70SXXK73, 130SDN132, and 234KTG236, according to Ambler's numbering system, as well as the motif 166EXXLN170, which is part of the so-called omega loop of class A β-lactamases, were found (Fig. 1). The class A β-lactamases of R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T and R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T were named PLA-1 and ORN-1, respectively, and their corresponding genes were named bla PLA-1A and bla ORN-1A, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of TEM-1, PLA-1, and ORN-1 amino acid sequences according to Ambler's numbering scheme. Asterisks indicate the identical residues in the three β-lactamases. Boldface residues are the highly conserved residues involved in the catalytic site of the class A β-lactamases.

Comparison of PLA-1 and ORN-1 sequences with the sequences of different class A β-lactamases.

PLA-1 and ORN-1 enzymes which displayed a high percentage of shared identity (94.2%) displayed a low percentage of identity, from 37 to 47%, with the chromosome-encoded class A β-lactamases previously described for Enterobacteriaceae, with the exception of the two β-lactamases described for K. pneumoniae, LEN-1 and SHV-1 (66 to 69% of identity) (Table 1). The highest percentages of identity were for both PLA-1 and ORN-1 with the plasmid-mediated β-lactamase TEM-1 at 71 and 69%, respectively. Compared with the sequence of TEM-1 (Fig. 1), the sequences of PLA-1 and ORN-1 showed two notable features: greater length (291 amino acids instead of 284) and an asparagine residue instead of a glutamic acid residue at position 240, according to Ambler's numbering system.

TABLE 1.

Percentage of amino acid identity of PLA-1 and ORN-1 β-lactamases and the most closely related class A β-lactamasesa

| Class A β-lactamase | % Amino acid identity

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA-1 | ORN-1 | TEM-1 | SHV-1 | LEN-1 | OXY-1 | RAHN-1 | Sed-1 | CdiA | CUM-A | HUG-A | FONA-1 | KLUC-1 | KLUA-1 | YENT | ERP-1 | MAL-1 | |

| PLA-1 | |||||||||||||||||

| ORN-1 | 94 | ||||||||||||||||

| TEM-1 | 71 | 69 | |||||||||||||||

| SHV-1 | 69 | 68 | 65 | ||||||||||||||

| LEN-1 | 67 | 66 | 62 | 88 | |||||||||||||

| OXY-1 | 39 | 39 | 37 | 37 | 37 | ||||||||||||

| RAHN-1 | 38 | 37 | 35 | 38 | 36 | 68 | |||||||||||

| Sed-1 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 36 | 73 | 68 | ||||||||||

| CdiA | 40 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 36 | 71 | 66 | 84 | |||||||||

| CUM-A | 37 | 37 | 34 | 33 | 35 | 64 | 60 | 63 | 63 | ||||||||

| HUG-A | 37 | 37 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 65 | 61 | 63 | 64 | 94 | |||||||

| FONA-1 | 40 | 39 | 36 | 36 | 37 | 73 | 75 | 71 | 70 | 66 | 66 | ||||||

| KLUC-1 | 40 | 39 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 73 | 71 | 72 | 71 | 61 | 62 | 72 | |||||

| KLUA-1 | 38 | 38 | 36 | 38 | 37 | 74 | 73 | 73 | 70 | 63 | 63 | 75 | 78 | ||||

| YENT | 39 | 40 | 38 | 38 | 39 | 55 | 55 | 54 | 53 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 58 | |||

| ERP-1 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 51 | 58 | 50 | ||

| MAL-1 | 47 | 47 | 45 | 44 | 42 | 39 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 38 | 40 | 39 | 40 | 35 | 36 | |

SHV-1 and LEN-1 from K. pneumoniae, KOXY (group OXY-1) from K. oxytoca, RAHN-1 from R. aquatilis, Sed-1 from C. sedlakii, CdiA from C. koseri (formerly diversus), CUM-A from P. vulgaris, HUG-A from P. penneri, FONA-1 from S. fonticola, KLUC-1 from K. cryocrescens; KLUA-1 from K. ascorbata, YENT from Y. enterocolitica, ERP-1 from E. persicina, and MAL-1 from C. koseri.

Putative promoter regions of the blaPLA-1A and blaORN-1A genes.

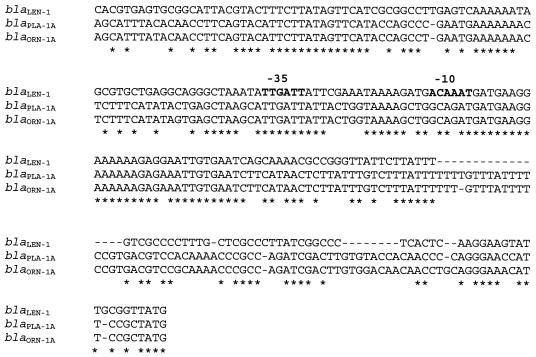

The nucleotide sequence upstream of the ORFs coding for PLA-1 and ORN-1 which displayed a high degree of homology to each other also showed a certain homology with the corresponding region of the blaLEN-1 gene and particularly with its promoter region (Fig. 2) (31). In fact, 161 bp upstream of the ATG codon of the blaPLA-1A and blaORN-1A genes, there was a sequence identical to that of the −35 region of the blaLEN-1 gene (TTGATT), which was separated by 17 bp from a nucleotide sequence (GCAGAT) which shared four nucleotides with the six nucleotides of the −10 region (ACAAAT) of the blaLEN-1 gene.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of DNA sequences upstream of the β-lactamase genes coding for LEN-1, PLA-1, and ORN-1. Dashes indicate gaps inserted in the alignment, and asterisks indicate identical nucleotides in the three genes. The −10 and −35 regions of the blaLEN-1 gene are indicated in boldface.

Sequences of the bla genes and the β-lactamases of R. planticola strain BM85.01.092 and R. ornithinolytica strain BM85.01.101.

The bla genes of R. planticola strain BM85.01.092 and R. ornithinolytica strain BM85.01.101 were amplified and sequenced by using the primer pairs VP1-VP2 and VO1-VO2, respectively. The bla gene of R. planticola strain BM85.01.092 was found to have 99.3% homology to the blaPLA-1A gene in relation to six different nucleotides (G745A, C790T, G884A, T952G, A1055G, and G1059C, according to Sutcliffe's numbering system). This nucleotide difference resulted in a β-lactamase with 99.3% identity with the β-lactamase PLA-1 in relation to two different amino acids (Ile287Val and Arg288Thr, according to Ambler's numbering system). Subsequently, the bla gene and the β-lactamase of R. planticola strain BM85.01.092 were named blaPLA-2A and PLA-2, respectively. Concerning the bla gene of R. ornithinolytica strain BM85.01.101, three silent nucleotide substitutions were observed in comparison with the gene of R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T (T871A, G883A, and T883C, according to Sutcliffe's numbering system). Accordingly, the bla gene and the β-lactamase of R. ornithinolytica strain BM85.01.101 were named blaORN-1B and ORN-1, respectively.

β-Lactam susceptibility.

β-Lactam susceptibility was tested on the two strains of R. planticola (ATCC 33531T and BM85.01.092) and the two strains of R. ornithinolytica (ATCC 31898T and BM85.01.101) as well as on E. coli NM554 and E. coli NM554 transformants harboring pBKpla1, pBKorn1, pACpla1, pACorn1, and pACtem1 (Table 2). The four Raoultella strains were resistant to amoxicillin and ticarcillin but susceptible to these molecules when they were tested in the presence of 2 μg of clavulanate/ml. They were also susceptible to piperacillin (alone as well as combined with 4 μg of tazobactam/ml), cephalothin, cefuroxime, cefoxitin, extended-spectrum cephalosporins, aztreonam, and imipenem. The E. coli NM554 transformants which harbored the low copy number recombinant plasmids pACpla-1 and pACorn-1 and from which the expression of the blaPLA-1A and the blaORN-1A genes was controlled by their natural promoter, displayed a β-lactam susceptibility profile similar to that of Raoultella sp. strains. Conversely, for the E. coli NM554 transformants harboring the high copy number recombinant plasmids pBKpla-1 and pBKorn-1, significantly higher MICs of all the β-lactam molecules tested except for cefoxitin, cefotaxime, and imipenem were observed. However, when the β-lactam susceptibility of these E. coli transformants was measured in the presence of class A β-lactamase inhibitors, β-lactam MICs were similar to those observed for the E. coli NM554 transformants harboring pACpla-1 and pACorn-1, except for the MICs of amoxicillin and ticarcillin for the two types of transformants and the MIC of piperacillin for the transformant harboring the recombinant plasmid pBKpla1.

TABLE 2.

β-Lactam susceptibility of Raoultella planticola and Raoultella ornithinolytica strains and Escherichia coli NM554 recipient and transformants

| β-Lactam | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

R. planticola strain

|

R. ornithinolytica strain

|

E. coli NM554 transformant

|

E. coli NM554 | |||||||

| ATCC 33531T | BM85.01.092 | ATCC 31898T | BM85.01.101 | pBKpla1c | pBKom1c | pACpla1d | pACom1d | pACtem1d | ||

| Amoxicillin | 256 | 128 | 128 | 128 | >1,024 | >1,024 | 512 | 512 | >1,024 | 8 |

| Amoxicillin + CLAa | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 256 | 32 | 4 | 4 | 32 | 4 |

| Ticarcillin | 256 | 512 | 256 | 256 | >1,024 | >1,024 | 1,024 | 1,024 | >1,024 | 2 |

| Ticarcillin + CLA | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 254 | 32 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 1 |

| Piperacillin | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | >1,024 | 256 | 8 | 8 | 128 | 1 |

| Piperacillin + TZEb | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1,024 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cephalothin | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 128 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 1 |

| Cefuroxime | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ND | 4 |

| Cefuroxime + CLA | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ND | 2 |

| Cefoxitin | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Cefotaxime | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

| Cefotaxime + CLA | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 8 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| Ceftazidime + CLA | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| Aztreonam | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 | ≤0.06 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Aztreonam + CLA | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | 1 | 0.25 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

| Cefepime + CLA | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

| Imipenem | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

CLA, clavulanate at a fixed concentration of 2 μg/ml.

TZB, tazobactam at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml.

Genes blaPLA-1A and blaORN-1A harbored by the high copy number vector pBKCMV.

Genes blaPLA-1A, blaORN-1A, and blaTEM-1B harbored by the low copy number vector pACYC184. ND, not determined.

Biochemical analysis of the β-lactamase PLA-1.

The PLA-1 and ORN-1 β-lactamases had an identical pI value of 7.8. Taking into consideration the fact that the β-lactamases PLA-1 and ORN-1 displayed 94.2% identity and conferred very similar β-lactam resistance patterns when they were produced in an isogenic system (same strains and plasmids), only the biochemical properties of PLA-1 were studied. The specific activity of the purified β-lactamase PLA-1, measured with 100 μM cephaloridine as substrate, was 930 U · mg−1 of protein, with a 25-fold purification factor. Its purity was estimated to be >95% by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis (data not shown). PLA-1 had a level of activity that was very strong against benzylpenicillin and strong against ticarcillin and piperacillin (Table 3). Significant hydrolytic activity against cephalothin and cephaloridine was also observed, while the activity levels observed against cefuroxime and cefepime were significantly lower but, nevertheless, higher than those observed against cefotaxime, cefpirome, and aztreonam (Table 3). No activity against ceftazidime was detectable.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters of purified β-lactamase PLA-1

| Substrate | kcat (S−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (μM−1 · s−1)b | Relative kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzylpenicillin | 2,600 | 30 | 87 (64) | 100 |

| Ticarcillin | 350 | 25 | 14 | 16 |

| Piperacillin | 2,260 | 145 | 15.6 | 18 |

| Cephalothin | 110 | 55 | 2 (0.6) | 2.5 |

| Cephaloridine | 700 | 145 | 4.8 (2.2) | 5.5 |

| Cefuroxime | 5 | 80 | 0.06 (0.06) | 0.1 |

| Cefoxitin | <0.01 | ND | ND | |

| Cefotaxime | 20 | 800 | 0.03 (0.001) | 0.05 |

| Ceftazidime | NDa | >3,000 | ND | |

| Cefpirome | 195 | 920 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Cefepime | 345 | 3,500 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Aztreonam | 70 | 1,870 | 0.03 (0.0007) | 0.03 |

| Moxalactam | <0.01 | ND | ND | |

| Imipenem | <0.01 | ND | ND |

ND, not determinable due to too low an initial rate of hydrolysis.

Values in parentheses are for TEM-1 (21).

Inhibition studies showed that the IC50s of clavulanic acid, tazobactam, and sulbactam were 0.04 μM, 0.09 μM, and 0.55 μM, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The two strains of R. planticola, ATCC 33531T and BM85.01.092, and the two strains of R. ornithinolytica, ATCC 31898T and BM85.01.10, were resistant to amoxicillin and ticarcillin but susceptible to the other β-lactam molecules tested and also to amoxicillin and ticarcillin when these two molecules were combined with 2 μg of clavulanate/ml. We demonstrated that this β-lactam resistance phenotype was related to a chromosomal class A β-lactamase that we called PLA for the strains of R. planticola and ORN for the strains of R. ornithinolytica. These two types of β-lactamases displayed a very high percentage of identity, that is, more than 94%. Such a high identity percentage between chromosomal β-lactamases of bacterial species belonging to the same genus seems to be rare (Table 1). To our knowledge, this case is the only one in the Proteus genus between the chromosomal β-lactamases CUM-A and HUG-A (94% identity) of P. vulgaris and P. penneri, respectively (16). In addition to the high percentage of identity between PLA-1 and ORN-1 of R. planticola strain ATCC 33531T and R. ornithinolytica strain ATCC 31898T, respectively, we also observed a high degree of homology between the nucleotide sequences upstream of the ATG codon of the encoding genes. Moreover, some of these nucleotides were identical or very similar to those accountable for the −35 and −10 regions of the blaLEN-1 gene coding for the K. pneumoniae β-lactamase LEN-1 with which PLA-1 and ORN-1 had 67 and 66% identity, respectively (31). This result strongly suggests that the promoter region of the genes encoding PLA-1 and ORN-1 is located 161 bp upstream of the ATG codon. We also observed that the blaPLA-1A and blaORN-1A genes displayed percent G+C content values slightly higher than the G+C ratio defined for R. planticola (2) and for R. ornithinolytica (32), whereas the nucleotide sequences downstream of the blaPLA-1A and blaORN-1A genes displayed a G+C ratio corresponding to the ratios defined for strains of R. planticola and R. ornithinolytica, respectively. These findings might suggest that the chromosomal bla genes of R. planticola and R. ornithinolytica result from an ancestral horizontal gene transfer. On the other hand, the highest identity percentage between the β-lactamases PLA-1 and ORN-1 was found with the plasmid-mediated β-lactamase TEM-1 (71 and 69%, respectively). To our knowledge, 71% is the highest identity percentage found between TEM-1 and a class A chromosomal β-lactamase. In spite of this relatively high degree of identity between the primary protein structure of TEM-1 and PLA-1, these enzymes differed from each other with regard to their substrate profile. In fact, PLA-1 had stronger hydrolytic activity than TEM-1 not only against penicillins but also against cephalosporins, including the extended-spectrum cephalosporins, and aztreonam (21). The catalytic efficiency of PLA-1 against cefotaxime was similar to the efficiencies observed for the chromosomal β-lactamases of Proteus penneri (16), Rahnella aquatilis (3), and E. persicina (35), whereas the efficiency against cefepime, which was rarely tested in the previous studies, was significantly higher than that observed for R. aquatilis (3) and resembled that displayed by plasmid-mediated CTX-M type β-lactamases such as CTX-M-18 (30). As the extended substrate profile of class A β-lactamases has previously been shown to be related to specific amino acid residues at defined positions, we analyzed the protein sequences of the β-lactamases of Raoutella spp. from this point of view. Concerning positions 104, 164, 179, 205, 237, 238, and 240 previously described as involved in the extended substrate specificity of TEM derivatives (5) and (positions 104, 237, 238), in addition to other positions (220, 228, 232, 236, 244, and 276), in the extended spectrum of chromosomal class A β-lactamases such as RAHN-1 (3), ERP-1 (35), Sed-1 (22), and KLUC-1 (7), we noted only one relevant amino acid substitution, namely, the substitution Glu240Asn. Consulting the literature, we found that this substitution was also found in the amino acid sequences of the extended-spectrum β-lactamases IBC-1 (9), GES-1, and GES-2 (29) although we did not find comments from the authors on the potential role of this substitution in the extended hydrolytic activity of these enzymes. Another amino acid substitution, Glu240Lys, was previously described at this position in TEM and SHV derivatives which are able to hydrolyze ceftazidime and aztreonam (5). All these results combined with the fact that the IC50s of clavulanate and tazobactam required to inhibit the hydrolytic activity of PLA-1 were similar to the value required for the class A β-lactamases, notably TEM-1 (6), suggested that the PLA and ORN enzymes be classified into the group 2be of the β-lactamase classification of Bush, Jacoby, and Medeiros (6).

In conclusion, the present study identified two novel, chromosomally encoded class A β-lactamases, PLA and ORN, from R. planticola and R. ornithinolytica strains, respectively. We found that they were more closely related to the chromosomal β-lactamase of K. pneumoniae than to the β-lactamase groups of K. oxytoca. Nevertheless, K. oxytoca is the Klebsiella species that is the most difficult to distinguish from Raoultella species with the routine methods used in a clinical laboratory. Besides fastidious biochemical methods (20), two molecular methods, the 16S rDNA or rpoB gene sequencing method (8, 19) and the ERIC-1R PCR method (10), have allowed for distinguishing among K. oxytoca, R. planticola, and R. ornithinolytica. Henceforth, as primers specific for the bla genes of these three bacterial species are available, the bla gene amplification method can also be carried out to distinguish them from each other.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. 2003. Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie report 2003. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 21:364-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagley, S. T., R. J. Seidler, and D. J. Brenner. 1981. Klebsiella planticola sp. nov.: a new species of Enterobacteriaceae found primarily in nonclinical environments. Curr. Microbiol. 6:105-109. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellais, S., L. Poirel, N. Fortineau, J. W. Decousser, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Biochemical-genetic characterization of the chromosomally encoded extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase from Rahnella aquatilis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2965-2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnboim, H. C., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford, P. A. 2001. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:933-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush, K., G. A. Jacoby, and A. A. Medeiros. 1995. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1211-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decousser, J. W., L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Characterization of a chromosomally encoded extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase from Kluyvera cryocrescens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3595-3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drancourt, M., C. Bollet, A. Carta, and P. Rousselier. 2001. Phylogenetic analyses of Klebsiella species delineate Klebsiella and Raoultella gen. nov., with description of Raoultella ornithinolytica comb. nov., Raoultella terrigena comb. nov. and Raoultella planticola comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:925-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giakkoupi, P., L. S. Tzouvelekis, A. Tsakris, V. Loukova, D. Sofianou, and E. Tzelepi. 2000. IBC-1, a novel integron-associated class A β-lactamase with extended-spectrum properties produced by an Enterobacter cloacae clinical strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2247-2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granier, S. A., V. Leflon-Guibout, F. W. Goldstein, and M. H. Nicolas-Chanoine. 2003. Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus 1R PCR assay for detection of Raoultella sp. isolates among strains identified as Klebsiella oxytoca in the clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1740-1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granier, S. A., L. Plaisance, V. Leflon-Guibout, E. Lagier, S. Morand, F. Goldstein, and M. H. Nicolas-Chanoine. 2003. Recognition of two genetic groups in Klebsiella oxytoca taxon on the basis of the chromosomal β-lactamase and housekeeping gene sequences as well as ERIC-1R PCR typing. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:661-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izard, D., C. Ferragut, I. F. Gavin, K. Kersters, J. De Ley, and H. Leclerc. 1981. Klebsiella terrigena, a new species from soil and water. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 31:116-127. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kado, C. I., and S.-T. Liu. 1981. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 145:1365-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanki, M., T. Yoda, T. Tsukamoto, and T. Shibata. 2002. Klebsiella pneumoniae produces no histamine: Raoultella planticola and Raoultella ornithinolytica strains are histamine producers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3462-3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lartigue, M. F., V. Leflon-Guibout, L. Poirel, P. Nordmann, and M. H. Nicolas-Chanoine. 2002. Promoters P3, Pa/Pb, P4, and P5 upstream from blaTEM genes and their relationship to β-lactam resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:4035-4037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liassine, N., S. Madec, B. Ninet, C. Metral, M. Fouchereau-Peron, R. Labia, and R. Auckenthaler. 2002. Postneurosurgical meningitis due to Proteus penneri with selection of a ceftriaxone-resistant isolate: analysis of chromosomal class A β-lactamase HugA and its LysR-type regulatory protein HugR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:216-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, Y., B. J. Mee, and L. Mulgrave. 1997. Identification of clinical isolates of indole-positive Klebsiella spp., including Klebsiella planticola, and a genetic and molecular analysis of their β-lactamases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2365-2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mariotte, S., P. Nordmann, and M. H. Nicolas. 1994. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase in Proteus mirabilis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33:925-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mollet, C., M. Drancourt, and D. Raoult. 1997. rpoB sequence analysis as a novel basis for bacterial identification. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1005-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monnet, D., and J. Freney. 1994. Method for differentiating Klebsiella planticola and Klebsiella terrigena from other Klebsiella species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1121-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perilli, M., A. Felici, N. Franceschini, A. De Santis, L. Pagani, F. Luzzaro, A. Oratore, G. M. Rossolini, J. R. Knox, and G. Amicasante. 1997. Characterization of a new TEM-derived β-lactamase produced in a Serratia marcescens strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2374-2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrella, S., D. Clermont, I. Casin, V. Jarlier, and W. Sougakoff. 2001. Novel class A β-lactamase Sed-1 from Citrobacter sedlakii: genetic diversity of β-lactamases within the Citrobacter genus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2287-2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Podschun, R. 1991. Isolation of Klebsiella terrigena from human feces: biochemical reactions, capsule types, and antibiotic sensitivity. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 275:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podschun, R., H. Acktun, J. Okpara, O. Linderkamp, U. Ullmann, and M. Borneff-Lipp. 1998. Isolation of Klebsiella planticola from newborns in a neonatal ward. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2331-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Podschun, R., and U. Ullmann. 1994. Incidence of Klebsiella planticola among clinical Klebsiella isolates. Med. Microbiol. Lett. 3:90-95. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podschun, R., and U. Ullmann. 1992. Isolation of Klebsiella terrigena from clinical specimens. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 11:349-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirel, L., M. Guibert, S. Bellais, T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 1999. Integron- and carbenicillinase-mediated reduced susceptibility to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in isolates of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 from French patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1098-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poirel, L., M. Guibert, D. Girlich, T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 1999. Cloning, sequence analyses, expression, and distribution of ampC-ampR from Morganella morganii clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:769-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poirel, L., I. Le Thomas, T. Naas, A. Karim, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Biochemical sequence analyses of GES-1, a novel class A extended-spectrum β-lactamase, and the class 1 integron In 52 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:622-632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poirel, L., T. Naas, I. Le Thomas, A. Karim, E. Bingen, and P. Nordmann. 2001. CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase that hydrolyzes ceftazidime through a single amino acid substitution in the omega loop. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3355-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice, L. B., L. L. Carias, A. M. Hujer, M. Bonafede, R. Hutton, C. Hoyen, and R. A. Bonomo. 2000. High-level expression of chromosomally encoded SHV-1 β-lactamase and an outer membrane protein change confer resistance to ceftazidime and piperacillin-tazobactam in a clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:362-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakazaki, R., K. Tamura, Y. Kosako, and E. Yoshizaki. 1989. Klebsiella ornithinolytica sp. nov., formerly known as ornithine-positive Klebsiella oxytoca. Curr. Microbiol. 18:201-206. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 34.Stock, I., and B. Wiedemann. 2001. Natural antibiotic susceptibility of Klebsiella pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, K. planticola, K. ornithinolytica and K. terrigena strains. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:396-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vimont, S., L. Poirel, T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 2002. Identification of a chromosome-borne expanded-spectrum class A β-lactamase from Erwinia persicina. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3401-3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westbrook, G. L., C. Mohr O'Hara, S. B. Roman, and J. M. Miller. 2000. Incidence and identification of Klebsiella planticola in clinical isolates with emphasis on newborns. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1495-1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]